ABSTRACT

DivIVA is a membrane binding protein that clusters at curved membrane regions, such as the cell poles and the membrane invaginations occurring during cell division. DivIVA proteins recruit many other proteins to these subcellular sites through direct protein-protein interactions. DivIVA-dependent functions are typically associated with cell growth and division, even though species-specific differences in the spectrum of DivIVA functions and their causative interaction partners exist. DivIVA from the Gram-positive human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes has at least three different functions. In this bacterium, DivIVA is required for precise positioning of the septum at midcell, it contributes to the secretion of autolysins required for the breakdown of peptidoglycan at the septum after the completion of cell division, and it is essential for flagellar motility. While the DivIVA interaction partners for control of division site selection are well established, the proteins connecting DivIVA with autolysin secretion or swarming motility are completely unknown. We set out to identify divIVA alleles in which these three DivIVA functions could be separated, since the question of the degree to which the three functions of L. monocytogenes DivIVA are interlinked could not be answered before. Here, we identify such alleles, and our results show that division site selection, autolysin secretion, and swarming represent three discrete pathways that are independently influenced by DivIVA. These findings provide the required basis for the identification of DivIVA interaction partners controlling autolysin secretion and swarming in the future.

IMPORTANCE DivIVA of the pathogenic bacterium Listeria monocytogenes is a central scaffold protein that influences at least three different cellular processes, namely, cell division, protein secretion, and bacterial motility. How DivIVA coordinates these rather unrelated processes is not known. We here identify variants of L. monocytogenes DivIVA, in which these functions are separated from each other. These results have important implications for the models explaining how DivIVA interacts with other proteins.

KEYWORDS: rough colony phenotype, Min system, autolysin secretion, cell division, division site selection

INTRODUCTION

DivIVA is a strongly conserved cell division protein found in most Gram-positive bacteria (1). It interacts with the membrane and clusters at curved membrane areas (2, 3). The cell poles and the invaginating septum during cell division are regions where the membrane is naturally bent, and consequently, DivIVA typically clusters at these sites (4–7). DivIVA serves as a central scaffold protein for the recruitment of other factors, and the list of recognized proteins, the localization of which depends on DivIVA, is constantly increasing (1). Among the DivIVA-dependent proteins are integral transmembrane proteins, as well as cytosolic proteins that are primarily involved in cell division (8–11), cell wall biosynthesis (7, 12, 13), or chromosome segregation (2, 14, 15).

DivIVA proteins generally consist of two domains, a strictly conserved N-terminal domain required for lipid binding and a lesser-conserved C-terminal domain (16), both forming parallel coiled-coil dimers. The N-terminal extensions of the two helices forming the coiled coil in the N-terminal domain cross each other and fold back onto the coiled-coil structure (16). Hydrophobic amino acids are exposed to the solvent at the apical end of this structure, and DivIVA interacts with membranes through the insertion of these side chains into the phospholipid bilayer (16, 17).

In addition to membrane binding, the lipid binding domain also mediates the interaction of DivIVA with binding partners, such as MinJ (18). In Bacillus subtilis, MinJ serves as a molecular bridge between DivIVA and MinD to ensure septal and polar recruitment of the division site selection proteins MinCD (10, 11). MinJ is a polytopic transmembrane protein and interacts with that domain of DivIVA, which already is in closest proximity to the membrane, the lipid binding domain (18). The C-terminal domain of DivIVA, which is oriented toward the cytoplasm, also associates with binding partners, such as the centromere-binding protein RacA (18), contributing to chromosome segregation in B. subtilis cells (19, 20). Considering that RacA is a soluble cytoplasmic protein, it therefore seems that DivIVA interacts with transmembrane proteins via its lipid binding domain and with cytoplasmic proteins through its C-terminal domain (18).

Further support for this compartment-specific mode of protein interactions with the two domains of DivIVA proteins was reported with GpsB, a paralogue of DivIVA in selected Gram-positive bacteria (21, 22). GpsB and DivIVA share their N-terminal lipid binding domains but differ in their C-terminal domains (21, 22). GpsB interacts with the bifunctional penicillin binding protein (PBP) A1, an integral transmembrane protein, and mutations preventing this interaction were mapped to the N-terminal domain of GpsB (22).

We are interested in DivIVA of Listeria monocytogenes, a firmicute bacterium that causes invasive disease in humans upon the ingestion of contaminated food. This bacterium has the remarkable ability to actively invade nonphagocytic human cell types, to multiply within their cytoplasm, and to spread from cell to cell (23, 24). The deletion of divIVA strongly impaired each of these three steps of the L. monocytogenes infection cycle (25). Secretion of the two autolysins p60 (CwhA) and NamA (MurA) through the SecA2-dependent secretion pathway is considerably reduced in an L. monocytogenes ΔdivIVA mutant (25). Both autolysins are necessary for daughter cell segregation after the completion of cell division; thus, a ΔdivIVA mutant grows as a long chain of unsegregated daughter cells (25). How DivIVA affects the activity of this secretion route remains unclear, but the recruitment of p60 and NamA preproteins to the divisional septum apparently requires DivIVA (25). Most likely, the failure of the ΔdivIVA mutant to invade human cells, to multiply within them, and to spread from one cell to the other is due to steric hindrances associated with cell chain formation. Moreover, DivIVA is important for the swarming motility of L. monocytogenes, as the absence of divIVA leads to a complete loss of flagellar motility. This defect could not be cured through cocultivation with a nonmotile but autolysin-producing L. monocytogenes mutant. In such an experiment, autolysins provided in trans suppress the chain-forming phenotype but do not cure the swarming defect of the ΔdivIVA mutant, suggesting that its swarming defect is not merely explained by cell chain formation (25). In addition to these functions, L. monocytogenes DivIVA is also required for precise positioning of the divisional septum in the middle of a dividing cell. This activity is dependent on the septal recruitment of the division-inhibitory MinCD proteins through DivIVA (26). In contrast to B. subtilis, where this interaction is mediated through MinJ (10, 11), DivIVA of L. monocytogenes seemingly interacts with MinD in a direct fashion, as suggested by bacterial two-hybrid experiments (26). Thus, not only do ΔdivIVA mutant cells form cell chains, but also the individual cells in these chains are considerably elongated (26).

To better understand how L. monocytogenes DivIVA orchestrates its multifarious functions, we aimed to identify divIVA alleles in which these functions are separated from each other. A domain-swapping approach between L. monocytogenes and B. subtilis DivIVA demonstrated the importance of the N-terminal domain for general DivIVA functionality but also identified divIVA alleles in which its functions in autolysin transport and division site placement could be uncoupled. Furthermore, we identified amino acid exchanges in the N-terminal domain of DivIVA that unlink swarming from autolysin secretion and division site selection. With this and further control experiments, we conclude that the three functions of DivIVA in SecA2-dependent transport, division site selection, and swarming are independent of each other.

RESULTS

B. subtilis DivIVA is not functional in L. monocytogenes.

Previous work has shown that DivIVA from L. monocytogenes (DivIVALm) is not functional in B. subtilis, even though the two proteins share 65% sequence identity (18) and are almost of the same length (175 versus 164 amino acids, respectively) (Fig. 1A). Apparently, subtle sequence variations between DivIVALm and DivIVA from B. subtilis (DivIVABs) are sufficient to prevent the relevant B. subtilis interaction partners from binding to DivIVALm.

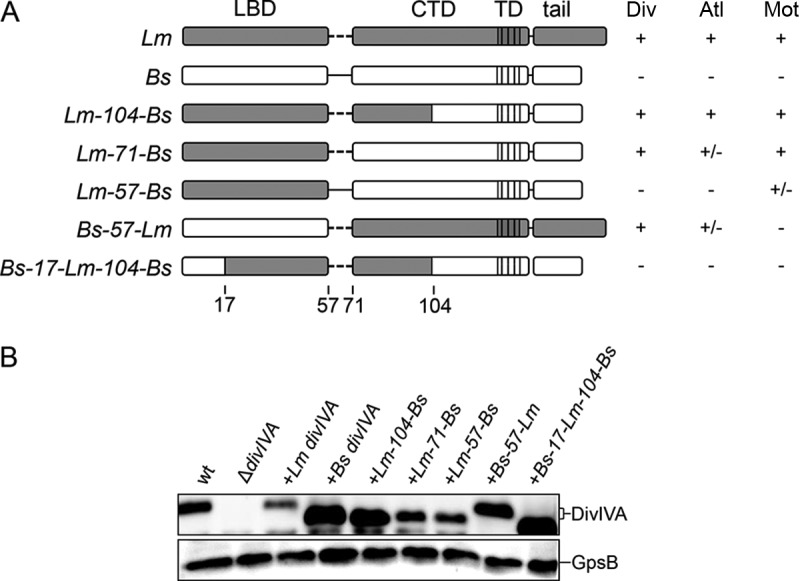

FIG 1.

Expression of chimeric DivIVA proteins in L. monocytogenes. (A) Schematic illustration showing the DivIVA chimeras analyzed in this study. Gray and white shaded areas indicate regions corresponding to L. monocytogenes and B. subtilis DivIVA, respectively. LBD, lipid binding domain; CTD, C-terminal domain; TD, tetramerization domain. The table to the right summarizes the division (Div), autolysin secretion (Atl), and swarming (Mot) phenotypes of strains expressing the divIVA chimeras (+, wild type-like phenotype; −, ΔdivIVA mutant-like phenotype; +/−, intermediate phenotype). (B) Western blot showing expression of chimeric DivIVA proteins in L. monocytogenes. Cellular proteins were isolated from strains EGD-e (wt), LMS2 (ΔdivIVA), LMS30 (+Lm divIVA), LMKK8 (+Bs divIVA), LMKK13 (+Lm-104-Bs divIVA), LMS157 (+Lm-71-Bs divIVA), LMKK12 (+Lm-57-Bs divIVA), LMKK14 (+Bs-57-Lm divIVA), and LMS149 (+Bs-17-Lm-104-Bs divIVA) grown in BHI broth containing 1 mM IPTG. Equal amounts of total cellular proteins were loaded, and DivIVA proteins were visualized by immunostaining using a polyclonal antiserum against B. subtilis DivIVA (top). A parallel Western blot detecting GpsB was performed to demonstrate equal loading (bottom).

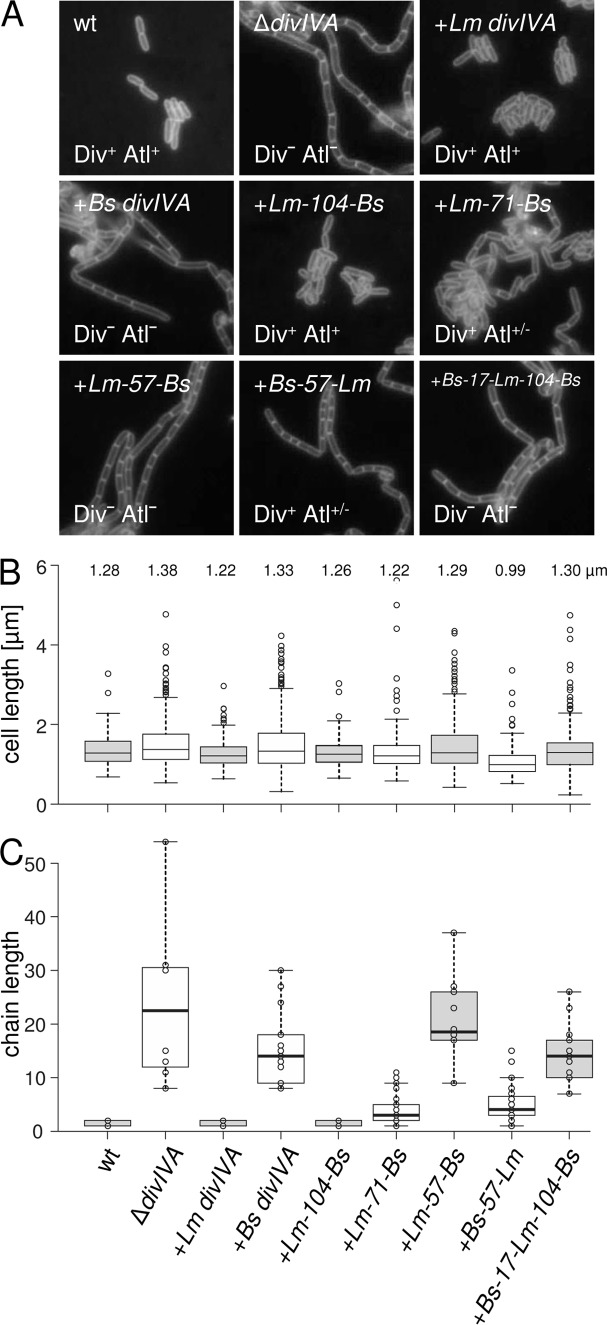

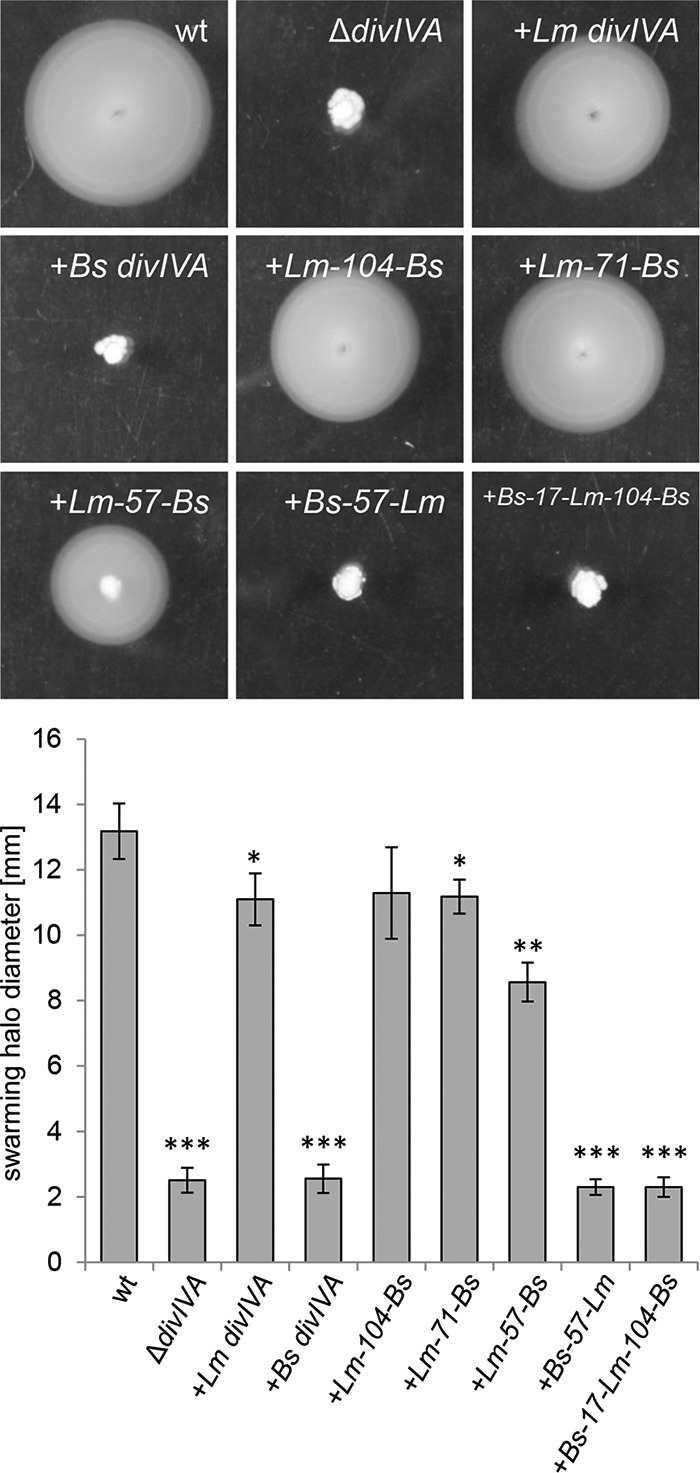

In L. monocytogenes, DivIVA affects (i) SecA2-dependent autolysin secretion, required for daughter cell separation (25); (ii) MinCD-dependent control of division site positioning (26), necessary for cell length maintenance; and (iii) swarming (25). Thus, a L. monocytogenes ΔdivIVA mutant forms long chains of unsegregated daughter cells with irregular length that do not swarm on semisolid agar plates. Presently, it is not known which of these three functions depend on which DivIVA domain, and it is even not clear whether they can be separated at all. To address this question, we first determined the complementation activity of DivIVABs in an L. monocytogenes ΔdivIVA mutant. For this purpose, an L. monocytogenes strain was constructed that lacks its endogenous divIVA gene but carries the divIVA gene of B. subtilis 168 under the control of an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter at an ectopic site (strain LMKK8). The expression of divIVABs in this strain was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 1B). Strain LMKK8 formed long cell chains, similar to the L. monocytogenes ΔdivIVA mutant (Fig. 2A and C), suggesting that SecA2-dependent autolysin secretion is not supported by DivIVABs. Likewise, strain LMKK8 was not able to swarm on semisolid agar plates (Fig. 3), indicating that divIVABs is nonfunctional in terms of swarming. Finally, LMKK8 cells (median cell length, 1.33 μm) are as elongated as ΔdivIVA mutant cells (median cell length, 1.38 μm), whereas wild-type cells are shorter (median cell length, 1.28 μm) (Fig. 2B). This shows that DivIVABs also cannot take over MinCD control in L. monocytogenes cells. Taken together, these results indicate that DivIVABs does not complement any of the three ΔdivIVA phenotypes in L. monocytogenes.

FIG 2.

Effect of chimeric DivIVA proteins on cell length and chaining of L. monocytogenes. (A) Fluorescence micrographs showing Nile red-stained cells. Strains EGD-e (wt), LMS2 (ΔdivIVA), LMS30 (+Lm divIVA), LMKK8 (+Bs divIVA), LMKK13 (+Lm-104-Bs divIVA), LMS157 (+Lm-71-Bs divIVA), LMKK12 (+Lm-57-Bs divIVA), LMKK14 (+Bs-57-Lm divIVA), and LMS149 (+Bs-17-Lm-104-Bs divIVA) were grown in BHI broth containing 1 mM IPTG at 37°C to mid-logarithmic growth phase and analyzed by microscopy. Div and Atl phenotypes are indicated. (B) Cell lengths of 300 cells per strain were measured, and the length distribution is illustrated in a box plot (http://shiny.chemgrid.org/boxplotr/). Center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, as determined by the R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles; and outliers are represented by dots. n = 300 sample points. Median cell lengths are given above the diagram. (C) Lengths of cell chains of ∼200 cells per strain were measured and illustrated in the same kind of box plot as in panel B.

FIG 3.

Swarming motility of L. monocytogenes strains expressing chimeric DivIVA proteins. Strains EGD-e (wt), LMS2 (ΔdivIVA), LMS30 (+Lm divIVA), LMKK8 (+Bs divIVA), LMKK13 (+Lm-104-Bs divIVA), LMS157 (+Lm-71-Bs divIVA), LMKK12 (+Lm-57-Bs divIVA), LMKK14 (+Bs-57-Lm divIVA), and LMS149 (+Bs-17-Lm-104-Bs divIVA) were stab inoculated into LB soft agar (containing 1 mM IPTG) and cultivated for 24 h at 30°C. The diameters of their swarming halos were determined in four independent experiments and plotted in the diagram shown below. Significance levels are indicated: ***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.01.

Separation of DivIVA functions using chimeric DivIVALm/Bs proteins.

To identify regions in DivIVA needed for support of its three functions, a domain-swapping approach similar to the one we have previously used for the identification of protein interaction domains in DivIVABs (18) was performed in L. monocytogenes. For this purpose, a set of chimeric divIVA genes, consisting of different parts of divIVABs and divIVALm (Fig. 1A), was expressed in the L. monocytogenes ΔdivIVA mutant background, and their expression was analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 1B). This showed that all the constructed chimeric DivIVA proteins were expressed, albeit to different degrees.

SecA2 activity and autolysin secretion (Atl phenotype) can be measured indirectly based on cell chain formation. Thus, the cellular morphology of strains expressing divIVA chimeras was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy of logarithmically growing cultures after membrane staining. Under these conditions, wild-type cells grow as individual rods or cell doublets, whereas the ΔdivIVA mutant forms chains of cells with up to ∼50 cells per chain (Fig. 2A and C). The formation of long cell chains similar to the ΔdivIVA mutant was also observed with strains expressing the divIVALm-57-Bs (LMKK12) and the divIVABs-17-Lm-104-Bs (LMS149) chimeras. In contrast, strain LMKK13, expressing divIVALm-104-Bs, formed wild-type-like rods, and strain LMS157 (divIVALm-71-Bs) and strain LMKK14 (divIVABs-57-Lm) showed an intermediate phenotype with partial daughter cell segregation (Fig. 2A and C). These data indicate that the first 104 N-terminal residues of DivIVALm are important for full SecA2-dependent autolysin secretion.

DivIVA controls the activity of the Min system; thus, the inactivation of DivIVA causes cell elongation in addition to cell chaining. As a result, the cell length distribution of a ΔdivIVA mutant is shifted toward longer cell lengths (22, 26). Measurement of cell lengths in strains expressing divIVA chimeras showed that the DivIVALm-104-Bs and the DivIVALm-71-Bs chimeras supported a wild-type-like cell length distribution. However, when the L. monocytogenes part of the chimeric proteins was further reduced down to those present in the DivIVALm-57-Bs or the DivIVABs-17-Lm-104-Bs chimera, the fraction of elongated cells increased (Fig. 2A and B). Remarkably, a cell length profile even shorter than in the wild type was observed with cells expressing the DivIVABs-57-Lm chimera. This indicates that DivIVA regions 1 to 71 or 57 to 175 are important during cell division.

Swarming analysis of the same set of strains revealed that only strains expressing the divIVALm-104-Bs, the divIVALm-71-Bs, or the divIVALm-57-Bs chimera were able to swarm (Fig. 3). These three chimeric proteins still contained the N-terminal domain of DivIVALm that comprises amino acid positions 1 to 57. In contrast, strains either expressing the divIVABs-17-Lm-104-Bs or the divIVABs-57-Lm chimera, in which the N-terminal domain of DivIVABs was fused to the C-terminal domain of DivIVALm, were unable to swarm (Fig. 3). Taken together, these results indicate that different regions in DivIVALm are required to sustain normal daughter cell segregation, cell division, and swarming.

The interaction of DivIVA and MinD is independent of MinJ.

The importance of an N-terminal region in DivIVA (amino acids 1 to 71) for normal cell division of L. monocytogenes is in good agreement with data obtained in B. subtilis showing that the N-terminal domain of DivIVABs interacts with MinJ (18). However, our observation that the divIVABs-57-Lm chimera also supports the normal cell division of L. monocytogenes seems to conflict with this model, as it suggests that either MinJ or MinD may also interact with the C-terminal DivIVA domain. An interaction of MinJ with the C-terminal DivIVA domain was not detected in previous B. subtilis experiments (18), but an interaction of MinD with the C-terminal DivIVA domain would be in accordance with results that claimed a direct interaction of MinD with DivIVA without the help of MinJ (26).

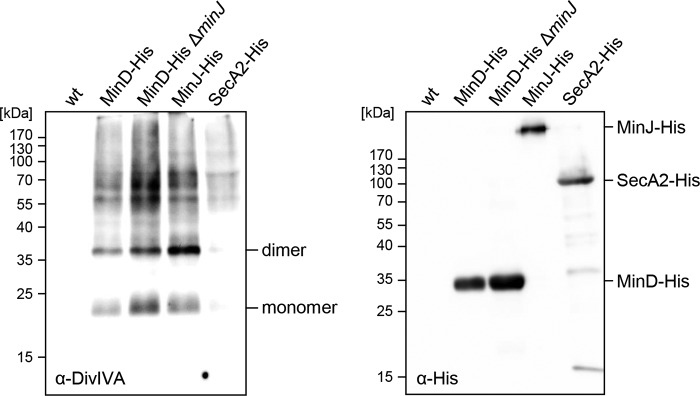

To confirm that MinD interacts with DivIVA in a MinJ-independent way, we performed pulldown experiments in L. monocytogenes cells expressing MinD-His10 as bait and either containing the minJ gene or not. Cells of strains LMJR86 (minD-his10) and LMJR85 (minD-his10 ΔminJ) were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth, and proteins were cross-linked with formaldehyde. MinD-His10 protein complexes were affinity purified and de-cross-linked by heat treatment. As previously shown (26), DivIVA can be detected by Western blotting in the pulldown eluates obtained with MinD-His10 as the bait protein in cells with a wild-type background (Fig. 4). Likewise, DivIVA was pulled down with MinD-His10 from lysates of LMJR85 cells that do not contain minJ. Control experiments confirmed that the MinD-His10 protein was pulled down whether MinJ was present or not (Fig. 4). Furthermore, DivIVA was pulled down with its known interaction partner MinJ-His and not detected in the absence of any bait protein. SecA2-His, as another negative control, only pulled down traces of DivIVA material (Fig. 4). This result shows that the interaction of MinD with DivIVA does not require MinJ in L. monocytogenes.

FIG 4.

DivIVA binding of MinD is MinJ independent. Western blots showing pulldown eluates obtained with MinD-His as the bait protein in wild-type (LMJR86) and ΔminJ mutant backgrounds (LMJR85). Strains expressing MinJ-His (LMJR84, positive control) and SecA2-His (LMKK3, negative control) were included. DivIVA was detected using a polyclonal antiserum raised against B. subtilis DivIVA (left blot), and His-tagged proteins were detected using an anti-His antibody (right blot). EGD-e (wt) was included as another negative control. Please note that MinJ-His (45.5 kDa) runs at an aberrant position after cross-linking and heat treatment (26).

Mutations in the N-terminal domain separate divIVA functions in swarming and division.

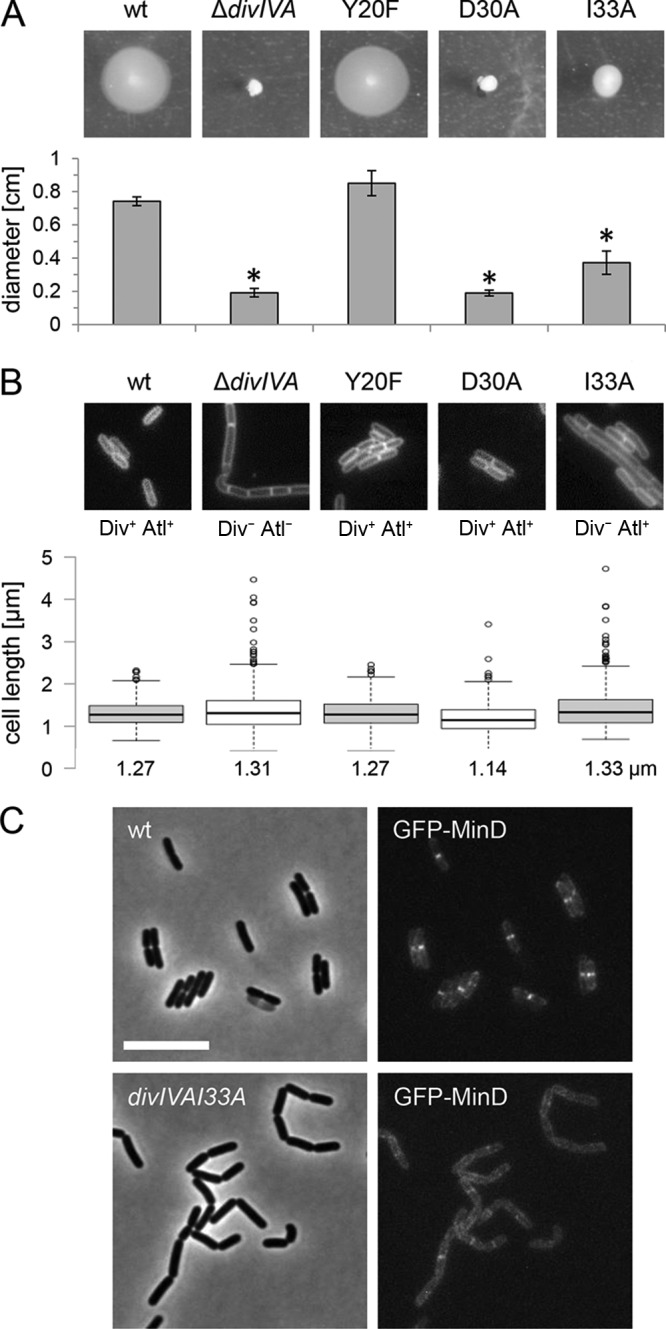

Previously published work on the DivIVA homolog GpsB has identified a strongly conserved groove on the surface of the N-terminal GpsB domain. This groove is formed by amino acids Y27, D33, D37, and I40 and contributes to the interaction of GpsB with the cytosolic N terminus of the major bifunctional penicillin binding protein (PBP) A1 (22). This protein motif is invariably present in most, if not all, GpsB homologs, but it is less conserved in DivIVA proteins (22). DivIVA of L. monocytogenes contains three of these four amino acids, but the D33 residue of L. monocytogenes GpsB is replaced by asparagine (residues Y20, N26, D30, and I33 in DivIVA). In order to analyze the importance of these residues for divIVA function, we constructed divIVA alleles in which the Y20, D30, or I33 residue was mutated. These alleles were then introduced into the chromosome of the ΔdivIVA mutant in a way that the divIVA open reading frame is restored at its original position in the chromosome but now expresses mutated divIVA variants (see inset in Fig. 7A). Replacement of Y20 with a phenylalanine residue (strain LMS196) did not affect DivIVA function, since this strain was fully motile (Fig. 5A), formed smooth colonies (data not shown), and grew as short rods with normal cell lengths (Fig. 5B). The exchange of D30 with alanine (strain LMS198) led to the loss of swarming motility (Fig. 5A), but autolysin secretion and cell division were unaffected, as deduced from the absence of cell chaining and normal cell length distribution (Fig. 5B), respectively. Thus, factors linking DivIVA with swarming motility likely no longer bind to DivIVAD30A, whereas the MinJ and MinD proteins still do. A partially inverse effect was observed with the I33A mutation (strain LMS197). Cells carrying this mutation were still able to swarm (∼50% of wild-type halo diameter) (Fig. 5A) but displayed a clear Div phenotype, typically characterized by cell elongation (Fig. 5B) (26). The Div phenotype depends on the recruitment of MinCD by DivIVA to the division septum (26). In good agreement with the above-mentioned observation, septal recruitment of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-MinD was distorted, and GFP-MinD was present at lateral membrane regions instead of the division septum in divIVAI33A mutant cells (Fig. 5C). None of the three divIVA mutants led to the formation of rough colonies (data not shown) or to cell chaining (Fig. 5B), suggesting that residues Y20, D30, and I33 are not important for control of the SecA2-dependent autolysin secretion. These results suggest that a stretch in DivIVA that is equivalent to the PBP A1 interaction groove of GpsB contributes to binding of MinD and factors affecting flagellar motility. Thus, a common region in the N terminus of DivIVA and GpsB proteins may be used for interaction with binding partners.

FIG 7.

Effect of selected divIVA mutants on intracellular growth in mouse macrophages. (A) Growth of L. monocytogenes strains EGD-e (wt), LMS2 (ΔdivIVA), LMS196 (divIVAY20F), LMS198 (divIVAD30A), and LMS197 (divIVAI33A) in BHI broth. Inset: Western blot showing DivIVA protein levels during growth under identical conditions in the same set of strains. (B) Intracellular growth of the same set of strains in J774 mouse macrophages. Significance levels are indicated: ***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.01. (C) Effect of the divIVALm-57-Bs allele (Div− Atl− Mot+/−, strain LMKK12) on intracellular growth in J774 mouse macrophages (cultivated in the presence of 1 mM IPTG for induction of divIVA alleles). L. monocytogenes strains EGD-e (wt), LMS2 (ΔdivIVA), and LMS30 (+Lm divIVA) were included for comparison. Intracellular growth was recorded based on CFU determination. Average values and standard deviations in panels A to C were calculated from experiments performed in triplicate. Significance levels are indicated: ***, P < 0.0001, **, P < 0.001.

FIG 5.

divIVA mutations separating division and swarming from autolysin secretion. (A) Swarming motility of L. monocytogenes strains EGD-e (wt), LMS2 (ΔdivIVA), LMS196 (divIVAY20F), LMS198 (divIVAD30A), and LMS197 (divIVAI33A) on semisolid LB agar plates. Swarming halo diameters were measured three times, and average values and standard deviations are shown in the diagram below. Significant differences are indicated by asterisks (P < 0.01). (B) Morphology of the same set of strains during exponential growth in BHI broth at 37°C. Micrographs show cells stained with Nile red. Div and Atl phenotypes are indicated. Please note that strain LMS197 (divIVAI33A) has the filamentous Div− phenotype but does not form chains. Cell lengths of 300 cells per strain were measured, and the results are presented in the diagram below, at the bottom of which median cell lengths are shown. (C) Effect of the divIVAI33A mutation on GFP-MinD localization. Strains LMKK30 and LMS227 were grown in BHI broth (containing 1 mM IPTG) at 30°C to mid-logarithmic growth phase and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (right). Phase-contract images are included for orientation (left). Scale bar is 5 μm.

Swarming motility is MinCDJ independent in L. monocytogenes.

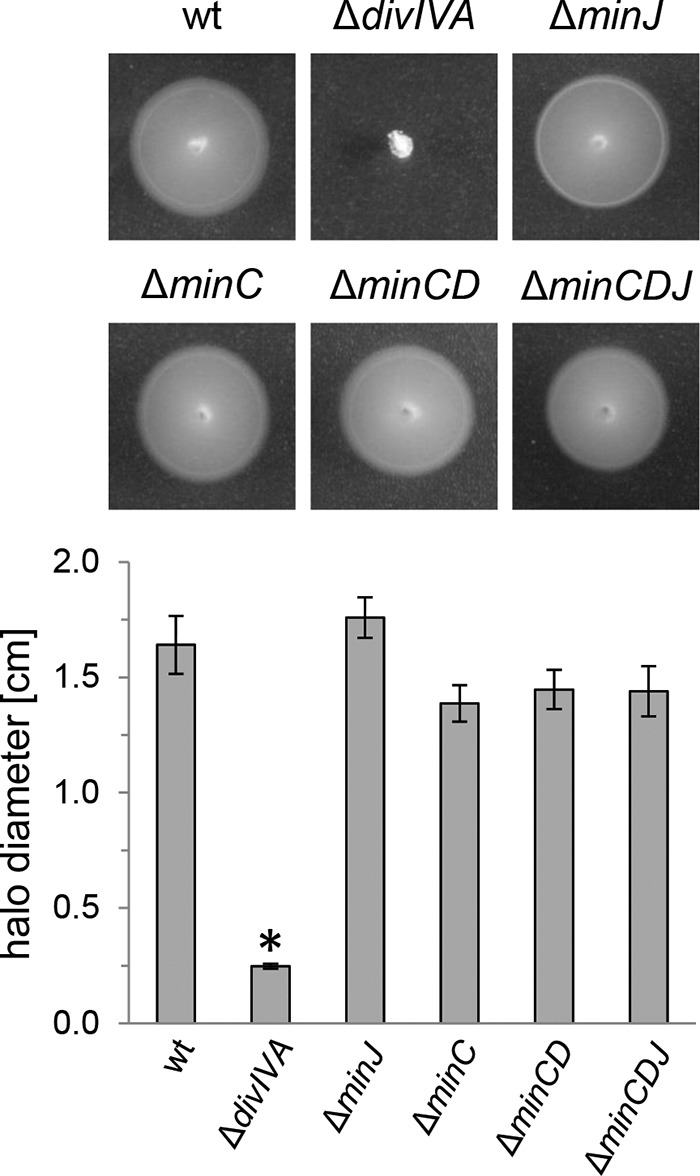

In the undomesticated B. subtilis strain 3610, MinJ is required for swarming motility without affecting flagellum formation (11). Likewise, an L. monocytogenes ΔdivIVA mutant is unable to swim, even though it produces flagella (25). These facts, together with the observation that the I33A exchange in DivIVA affected cell division and motility, suggested that DivIVA could affect the swarming motility of L. monocytogenes through the Min system. This hypothesis was tested in a simple swarming assay, comparing the swarming motility of the ΔdivIVA mutant with that of mutants lacking the min genes. As can be seen in Fig. 6, the lack of neither minC (strain LMS148), minJ (LMS120), minCD (LMKK35), nor minCDJ (LMKK54) impaired the swarming motility of L. monocytogenes, whereas the ΔdivIVA mutant was completely unable to swarm under this condition. This result demonstrates that the effect DivIVA exerts on swarming motility of L. monocytogenes does not involve the MinCDJ proteins.

FIG 6.

Swarming motility is MinCDJ independent in L. monocytogenes. Swarming of L. monocytogenes strains EGD-e (wt), LMS2 (ΔdivIVA), LMS120 (ΔminJ), LMS148 (ΔminC), LMKK35 (ΔminCD), and LMKK54 (ΔminCDJ) on LB soft agar plates. Swarming halo diameters were measured three times, and the average values and standard deviations are shown in the diagram shown below. Significance levels are indicated: *, P < 0.01.

Contribution of DivIVA functions to in vitro virulence.

The L. monocytogenes ΔdivIVA mutant is heavily impaired in its ability to invade nonphagocytic human cells, to multiply within them, and to spread from one cell to another in various in vitro virulence models (25). We assumed that this severe degree of virulence attenuation could be explained by the combination of cell chaining, immotility, and distorted cell division rather than by negative effects on specific virulence factors required for host cell invasion, intracellular multiplication, or cell-to-cell spread (25). The amino acid exchanges in the N-terminal domain of DivIVA described above provided the first opportunity to answer the question as to what degree these three different defects contribute to virulence attenuation of the ΔdivIVA mutant, as none of these affected growth in liquid culture (Fig. 7A). Intracellular multiplication was tested in J774.A1 mouse ascites macrophages. L. monocytogenes wild-type bacteria are rapidly phagocytosed by these macrophages, escape from their phagosomes, and then multiply within their cytoplasm. In contrast, the intracellular growth of the ΔdivIVA mutant stopped 2 h postinfection, and then the number of intracellular bacteria steadily decreased, indicating efficient killing of ΔdivIVA mutant cells by the macrophages (Fig. 7B). This suggests that the ΔdivIVA mutant is unable to survive under the harsh conditions of their phagosomes. Interestingly, strains carrying the Y20F (Div+ Atl+ Mot+) and I33A (Div− Atl+ Mot+/− [“+/−” indicates an intermediate phenotype]) exchanges in DivIVA grew like the wild type in this assay, whereas the D30A (Div+ Atl+ Mot−) mutant multiplied somewhat slower (Fig. 7). These data show that virulence attenuation of the L. monocytogenes ΔdivIVA mutant does not result from defects in cell division and is only to a minor extent explained by the motility defect associated with the ΔdivIVA mutation. Instead, the virulence defect of the ΔdivIVA mutant is likely attributed to its chain-forming mode of growth. This conclusion was further substantiated by an experiment measuring the intracellular growth of the Div− Atl− Mot+/− strain LMKK12, expressing the divIVALm-57-Bs allele, in J774 cells. This strain, forming chains but showing residual motility, was completely unable to proliferate inside macrophages (Fig. 7C).

DISCUSSION

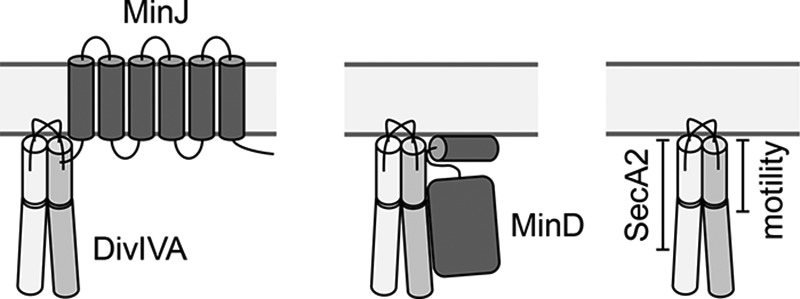

DivIVA is a pivotal protein for the recruitment of several functionally distinct proteins to the cell poles and the septum. Despite their diversity among the different bacteria, some DivIVA interaction partners can be found in several species, such as the ParB/Spo0J proteins, required for chromosome segregation. Binding of DivIVA to these proteins was reported for B. subtilis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Corynebacterium glutamicum, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Streptomyces coelicolor (6, 14, 27). Seven different interaction partners of DivIVA are known in B. subtilis (MinJ, RacA, Spo0J, SpoIIE, SecA, Maf, and ComN) (2, 10, 11, 27–31), and DivIVA of S. pneumoniae supposedly interacts with up to 14 distinct binding partners, among which are most divisome components and the two cell wall hydrolases LytB and PcsB (6). Given this multitude of structurally different interaction partners that even are active in different cellular compartments (i.e., the membrane and the cytoplasm), competition for a commonly used docking site in DivIVA seems unlikely. However, if separated binding sites for interaction with different protein partners exist in DivIVA, it must be possible to find mutations that affect the binding of one interaction partner without impairing the binding of others (18). In fact, the binding sites for MinJ and RacA are nonoverlapping in B. subtilis DivIVA, whose lipid binding domain interacts with the transmembrane protein MinJ (Fig. 8) and the C-terminal domain with cytosolic RacA (18).

FIG 8.

Protein interaction domains in L. monocytogenes DivIVA. Three cartoons summarizing the current view of how DivIVA interacts with its binding partners. Left, data from B. subtilis suggest that the N-terminal DivIVA domain binds MinJ (18). Middle, regions in the N-terminal and the C-terminal domains of L. monocytogenes DivIVA are crucial for MinD binding (this study). Right, residues 1 to 104 (N-terminal domain with a short section of the C-terminal domain) and 1 to 71 (N-terminal domain with the adjacent linker) of L. monocytogenes DivIVA are required for SecA2-dependent autolysin secretion and for flagellar motility (this study), respectively.

Here, we present the first set of DivIVA variants separating its different functions in the dangerous human pathogen L. monocytogenes. First of all, we show that the N-terminal 104 amino acids of L. monocytogenes DivIVA contain the region essential for SecA2-dependent autolysin secretion (Fig. 8). As soon as this section in the respective chimeras is further shortened down to amino acids 1 to 71 or 1 to 57 or when the N-terminal domain of DivIVALm was replaced with that of DivIVABs, the formation of cell chains was observed, indicating less efficient autolysin transport. Thus, DivIVA residues inside and outside the lipid binding domain of DivIVA are crucial for autolysin secretion. The protein that links DivIVA with this process is presently still unknown, and, due to the participation of both DivIVA domains, we still cannot decide whether transmembrane or soluble proteins should rather be considered as candidates for this. Also, none of the three tested amino acid exchanges in the N-terminal DivIVA domain resulted in the formation of cell chains. Thus, it seems that DivIVA regions other than those supporting the interaction of GpsB with PBP A1 contribute to the interaction of DivIVA with this unknown factor.

A shorter N-terminal fragment, comprising only amino acids 1 to 71, needs to be present in the DivIVA chimera for full support of flagellar motility (Fig. 8), while partial swarming was still observed in cells expressing the DivIVALm-57-Bs chimera. Furthermore, point mutations in the N-terminal domain of DivIVA (D30A and I33A) were sufficient to interfere with swarming motility. Thus, we assume that the protein connecting DivIVA with the flagellum interacts with the lipid binding domain and that it is likely to be a transmembrane protein.

Remarkably, the N- and the C-terminal domains of L. monocytogenes DivIVA supported normal cell division (Fig. 8) in the chimera experiments independent of each other. This result is counterintuitive in the first instance but would be in agreement with previous work that showed that MinD and MinJ, the two proteins transmitting the spatial input of DivIVA to the cell division machinery, interact directly with DivIVA (26). In B. subtilis, the lipid binding domain of DivIVA interacts with the integral membrane protein MinJ (18), through which the contact to MinD is made. MinD is a soluble protein but also binds the membrane through an amphipathic helix (32). MinD is a ParA-like ATPase (33), and ParA of Mycobacterium smegmatis interacts with regions in the N- and C-terminal domains of DivIVA (34). It thus seems likely that L. monocytogenes MinD also might make contacts with the C-terminal domain of DivIVA (Fig. 8). More sophisticated experiments would be needed to test this hypothesis.

With the D30A exchange in L. monocytogenes DivIVA, we have identified a mutation that completely blocked swarming but affected neither autolysin secretion nor cell division. Likewise, the I33A mutation affected division but not autolysin transport. The D30A mutation now unequivocally shows that the swarming defect of the ΔdivIVA mutant is not simply explained by the long cell chains it forms, simply because divIVAD30A cells do not form chains but still they are nonmotile. This conclusion is further substantiated by the observation that cells expressing the divIVALm-57-Bs chimera could swarm, at least partially, even though they formed cell chains. All this is in good agreement with previous experiments, which already demonstrated that splitting of ΔdivIVA cell chains did not restore motility (25). Apparently, growth as a cell chain does not prevent swarming per se. This concept is still challenged by the observation that a ΔsecA2 mutant is also unable to swarm (data not shown), but this might be for different reasons.

Finally, our results clarify that the chain-forming growth of the ΔdivIVA mutant, which is due to deficient SecA2-dependent secretion of autolysins, must be the main reason for its virulence attenuation, at least in the infection model tested so far (25). Remarkably, the chosen macrophages even started to clear the infection with ΔdivIVA mutant bacteria. This can be taken as further support for the assumption that DivIVA might be a useful drug target to treat L. monocytogenes infections in the future.

Taking these results together, we show that the three activities of DivIVA in cell division, SecA2-dependent transport, and swarming motility can be separated from each other. The chimeras and mutants of divIVA that we identified in this study might be useful as starting points in suppressor mutagenesis screens to identify those proteins that connect DivIVA with the flagellum and the SecA2-dependent protein secretion pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Table 1 lists all bacterial strains used in this study. L. monocytogenes was routinely cultivated in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth or on BHI agar plates at 37°C. If required, antibiotics and supplements were added to the growth media at the following concentrations: erythromycin, 5 μg · ml−1; kanamycin, 50 μg · ml−1; 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal), 100 μg · ml−1; and IPTG, 1 mM. Escherichia coli TOP10 was used as the standard host for all cloning procedures (35).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pIMK3 | Phelp-lacO lacI neo | 36 |

| pMAD | bla erm bgaB | 38 |

| pJR55 | Phelp-minD-his10 neo | 26 |

| pSH2 | bla aprE5′ spc lacI Pspac-divIVABs aprE3′ | 16 |

| pSH19 | bla amyE3′ spc Pxyl-divIVABs amyE5′ | 18 |

| pSH186 | bla erm bgaB ΔdivIVA (lmo2020) | 25 |

| pSH260 | bla amyE3′ spc Pxyl- divIVALm-71-Bs amyE5′ | 18 |

| pSH221 | Phelp-lacO-divIVALm lacI neo | 25 |

| pKK16 | Phelp-lacO-divIVABs lacI neo | This work |

| pKK17 | Phelp-lacO-divIVALm-104-Bs lacI neo | This work |

| pKK18 | Phelp-lacO-divIVALm-57-Bs lacI neo | This work |

| pKK21 | Phelp-lacO-divIVABs-57-Lm lacI neo | This work |

| pKK90 | bla erm bgaB divIVALm | This work |

| pSH388 | Phelp-lacO-divIVABs-17-Lm-104-Bs lacI neo | This work |

| pSH394 | Phelp-lacO-divIVALm-71-Bs lacI neo | This work |

| pSH472 | bla erm bgaB divIVAD30A | This work |

| pSH473 | bla erm bgaB divIVAY20F | This work |

| pSH474 | bla erm bgaB divIVAI33A | This work |

| L. monocytogenes strains | ||

| EGD-e | Wild-type serovar 1/2a strain | Lab collection |

| LMJR84 | attB::Phelp-minJ-his10 neo | 26 |

| LMJR86 | attB::Phelp-minD-his10 neo | 26 |

| LMKK3 | attB::Phelp-secA2-his10 neo | 26 |

| LMKK30 | attB::Phelp-gfpA206K-minD neo | 26 |

| LMKK35 | ΔminCD | 26 |

| LMKK54 | ΔminCDJ | 26 |

| LMS2 | ΔdivIVA | 25 |

| LMS30 | ΔdivIVA attB::Phelp-lacO-divIVALm lacI neo | 25 |

| LMS120 | ΔminJ | 26 |

| LMS148 | ΔminC | 26 |

| LMJR85 | ΔminJ attB::Phelp-minD-his10 neo | This work |

| LMKK8 | ΔdivIVA attB::Phelp-lacO-divIVABs lacI neo | This work |

| LMKK12 | ΔdivIVA attB::Phelp-lacO-divIVALm-57-Bs lacI neo | This work |

| LMKK13 | ΔdivIVA attB::Phelp-lacO-divIVALm-104-Bs lacI neo | This work |

| LMKK14 | ΔdivIVA attB::Phelp-lacO-divIVABs-57-Lm lacI neo | This work |

| LMS149 | ΔdivIVA attB::Phelp-lacO-divIVABs-17-Lm-104-Bs lacI neo | This work |

| LMS157 | ΔdivIVA attB::Phelp-lacO-divIVALm-71-Bs lacI neo | This work |

| LMS196 | divIVAY20F | This work |

| LMS197 | divIVAI33A | This work |

| LMS198 | divIVAD30A | This work |

| LMS227 | divIVAI33A attB::Phelp-gfpA206K-minD neo | This work |

General methods, manipulation of DNA, and oligonucleotide primers.

E. coli transformation and isolation of plasmid DNA were performed according to standard protocols (35). Electroporation of L. monocytogenes was done as described previously (36). Enzymatic modification of plasmid DNA was carried out as described by the instructions given by the manufacturers. QuikChange mutagenesis was employed for restriction-free modification of plasmids (37). The DNA sequences of the oligonucleotide primers are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| KK20 | TTATAAACAATAGTCGTATGGAGGTGCTAGATATGCCATTAACGCCAAATGATATT |

| KK21 | GATCGTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGCGCTCGAGTTATTCCTTTTCCTCAAATACAGC |

| KK113 | CAATAGTCGTATGGAGGTGCTAGATATGCCATTATCGCCGCTGGATAT |

| KK114 | CTTACTTGTCTCTAATAATCGTTTTTAACGTTCTTCAGATTCAGCTG |

| SHW180 | CGAAGTAAATGACTTCCTCGATC |

| SHW208 | TAGAGTAATTCTGTAAAGGTCC |

| SHW266 | GCAGAAAAAAATGCTGACCGAATTATCAACGAATCGTTATCAAAATC |

| SHW353 | CTTTAAATAATAGTGAAGAACGTATCGGACACTTTGCCAATATTG |

| SHW354 | GTCGTATGGAGGTGCTAGATATGCCATTAACGCCAAATGATATTC |

| SHW355 | GTTTCTTCAATGTTTGTAAAATGACCGATTCTTTCATCAAGCTCATTG |

| SHW506 | CTTCGTCTTCGTCATAACCTCTAAAACTTTTTGTAAACGTCTTGTTGTG |

| SHW508 | ACGCCCGCCATAAAATGCCAGGAATTGGG |

| SHW530 | GCGTCGACTTCATACTCAAGG |

| SHW734 | TTAGAGGTTTTGACGAAGACGAAGTAAATGAC |

| SHW735 | TCTTCGTCAAAACCTCTAAAACCACGGGTAAAC |

| SHW736 | ACTTCCTCGCACAAATCATTAAAGATTATGAACAAG |

| SHW737 | ATGATTTGTGCGAGGAAGTCATTTACTTCGTC |

| SHW738 | ATCAAATCGCAAAAGATTATGAACAAGTTATCAAAG |

| SHW739 | TAATCTTTTGCGATTTGATCGAGGAAGTCATTTAC |

Construction of strains expressing chimeric and mutated DivIVA proteins.

Plasmid pKK16 was constructed to allow for the expression of B. subtilis divIVA (divIVABs) in L. monocytogenes cells. For this purpose, the divIVABs gene was amplified from plasmid pSH2 using the primers KK20/KK21. The resulting DNA fragment was then used as a megaprimer in a second PCR to replace the divIVALm open reading frame of plasmid pSH221 with the divIVABs gene. For the construction of plasmid pKK17, expressing the chimeric divIVALm-104-Bs gene, the C-terminal region of divIVABs was amplified from plasmid pSH19 using the primer pair SHW266/KK21 and used as a megaprimer in a second PCR with pSH221 as the template. Plasmid pKK18 was constructed by generating a DNA fragment comprising the C-terminal divIVABs domain plus additional downstream plasmid backbone sequences using the oligonucleotides SHW208/SHW353 and pKK16 as the template. This DNA fragment was then used as a primer in a second PCR on plasmid pSH221 as the template in order to create the divIVALm-57-Bs allele. For the construction of plasmid pKK21, expressing the divIVABs-57-Lm allele, a PCR product comprising the N-terminal domain of divIVABs was generated with the primer pair SHW354/SHW355 on plasmid pKK16. This fragment was then used as the primer in a second PCR with plasmid pSH221 as the template. Plasmid pSH388 was constructed by the generation of a PCR product with the primers SHW506/SHW508 and pKK16 as the template as the first step. This PCR product was then used as a primer in a second PCR with plasmid pKK17 as the template to create the divIVABs-17-Lm-104-Bs allele. Plasmid pSH394 was generated using a similar strategy. Here, a PCR fragment was generated using the primer pair SHW180/SHW530 with plasmid pSH260 as the template. This DNA fragment was then used as a primer in a second PCR with plasmid pKK17 as the template to obtain the desired divIVALm-71-Bs allele.

Plasmids carrying divIVA genes for ectopic expression were introduced into L. monocytogenes EGD-e by electroporation, and kanamycin-resistant clones were selected. Plasmid insertion at the attB site of the tRNAArg locus was verified by PCR. Subsequently, the chromosomal copies of divIVA were removed using plasmid pSH186. For this purpose, pSH186 was transformed into the respective L. monocytogenes recipient strains, and the divIVA gene was removed according to a protocol described previously (38). All gene deletions were verified by PCR.

Construction of chromosomal divIVA mutants.

For the construction of plasmid pKK90, the divIVA gene from L. monocytogenes EGD-e was amplified from chromosomal DNA using the oligonucleotides KK113/KK114, and the resulting PCR fragment was then used as the primer in a second PCR to introduce the divIVA gene into plasmid pSH186. Plasmids pSH472, pSH473, and pSH474 were then constructed by QuikChange mutagenesis using pKK90 as the template and the primer pairs SHW736/SHW737, SHW734/SHW735, and SHW738/SHW739, respectively. For the introduction of the mutated divIVA genes into the native site of the L. monocytogenes chromosome, plasmids pSH472, pSH473, and pSH474 were transformed into the L. monocytogenes ΔdivIVA mutant LMS2. Allelic exchange was performed according to the homologous recombination protocol described by others (38). All replacements were confirmed by PCR.

Isolation of proteins and Western blotting.

L. monocytogenes strains were grown in BHI broth and harvested by centrifugation at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0. Cells were washed with ZAP buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5] and 200 mM NaCl), resuspended in 1 ml of ZAP buffer also containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and disrupted by sonication. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (1 min, 13,000 rpm in a tabletop centrifuge). The resulting supernatant was considered the total cellular protein extract. Protein concentration was determined by an adaptation of the Bradford protein assay using Roti-Nanoquant solution (Carl Roth), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protein extracts were separated by standard SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto positively charged polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes using a semidry transfer unit. Proteins of interest were immunostained using polyclonal rabbit antisera raised against B. subtilis DivIVA (39) or L. monocytogenes GpsB (22) or a monoclonal mouse antibody recognizing the polyhistidine epitope (GE Healthcare) as the primary antibody and anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich) as the secondary antibodies. The peroxidase conjugates were detected on the PVDF membrane using the ECL chemiluminescence detection system (Thermo Scientific).

In vivo formaldehyde cross-linking and pulldown.

Cross-linking was performed according to a previously published B. subtilis protocol (26, 40). Briefly, L. monocytogenes strains expressing His-tagged bait proteins were grown in 500 ml of BHI broth at 37°C until an OD600 of 1.0 was reached and then treated with formaldehyde (final concentration, 1%) for 30 min. Cross-linking was quenched by addition of 50 mM glycine (final concentration) for 5 min. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 2 ml of UT buffer (0.1 M HEPES, 0.5 M NaCl, 50 mM imidazole, 8 M urea, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]), and disrupted by sonication. Cell debris was removed, and the cleared lysates were incubated with 200 μl of MagneHis solution (Promega, USA) overnight. The MagneHis particles were washed five times with 1.5 ml of UT buffer before protein complexes were eluted with the elution buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5 M imidazole, 1% SDS, 10 mM DTT). Eluates were concentrated 5-fold using centrifugal microconcentrators. Samples were mixed with SDS-PAGE loading dye, and cross-linking was reversed by heating at 95°C for 1 h. De-cross-linked samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting.

Microscopy.

Samples (0.4 μl) from logarithmically growing cultures were spotted onto microscope slides covered with a thin film of agarose (1.5% in distilled water), air dried, and covered with a coverslip. For staining of membranes, 1 μl of Nile red (100 μg · ml−1 in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) was added to 100 μl of culture, and the mixture was shaken for 10 min before the cells were used for microscopy. Images were taken with a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope coupled to a Nikon DS-MBWc charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera and processed using the NIS-Elements Advanced Research software package (Nikon).

Swarming assay.

LB soft agar plates containing 0.3% agar were stab inoculated with the respective L. monocytogenes strains. Differences in motility were observed as swarming halos of various diameters after 1 day of incubation at 30°C. Statistical significance of the differences in halo diameter was determined using the unpaired t test.

Intracellular growth assay.

Intracellular growth in macrophages was analyzed using J774.A1 mouse ascites macrophages (ATCC TIB-67), as described earlier (41). Briefly, 3 × 105 J774.A1 mouse ascites macrophages (ATCC) were seeded into the wells of a 24-well plate and cultivated in 1 ml of high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; 4.5 g/liter glucose, 110 mg/liter sodium pyruvate, 584 mg/liter l-glutamine) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere 1 day before the infection experiment. L. monocytogenes strains were grown overnight in BHI (containing 1 mM IPTG where necessary) broth at 37°C and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.2, followed by further dilution (1:100) in DMEM not containing FCS. Fifty-microliter aliquots of this resuspension (∼1 × 105 bacterial cells) were used to infect the J774 cells during an incubation step of 1 h at 37°C. The wells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and all extracellular bacteria were killed during another 1 h of incubation in DMEM (without FCS) containing 40 μg/ml gentamicin. After one more PBS washing step, the wells were covered with fresh DMEM (without FCS) containing 10 μg/ml gentamicin. Sampling was performed by lysing the cells in 1 ml of ice-cold PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 at selected time points. Serial dilutions were plated on BHI agar plates and incubated overnight at 37°C to count the recovered bacterial colonies. Statistical significance was determined using the unpaired t test.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by a Siemens/DAAD postgraduate fellowship to K.G.K., DFG grants HA 6830/1-1 and HA 6830/1-2, and a grant of the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (FCI) to S. Halbedel.

We thank all members of the department for fruitful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaval KG, Halbedel S. 2012. Architecturally the same, but playing a different game: the diverse species-specific roles of DivIVA proteins. Virulence 3:406–407. doi: 10.4161/viru.20747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lenarcic R, Halbedel S, Visser L, Shaw M, Wu LJ, Errington J, Marenduzzo D, Hamoen LW. 2009. Localisation of DivIVA by targeting to negatively curved membranes. EMBO J 28:2272–2282. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramamurthi KS, Losick R. 2009. Negative membrane curvature as a cue for subcellular localization of a bacterial protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:13541–13545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906851106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards DH, Thomaides HB, Errington J. 2000. Promiscuous targeting of Bacillus subtilis cell division protein DivIVA to division sites in Escherichia coli and fission yeast. EMBO J 19:2719–2727. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinho MG, Errington J. 2004. A divIVA null mutant of Staphylococcus aureus undergoes normal cell division. FEMS Microbiol Lett 240:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadda D, Santona A, D'Ulisse V, Ghelardini P, Ennas MG, Whalen MB, Massidda O. 2007. Streptococcus pneumoniae DivIVA: localization and interactions in a MinCD-free context. J Bacteriol 189:1288–1298. doi: 10.1128/JB.01168-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flärdh K. 2003. Essential role of DivIVA in polar growth and morphogenesis in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol Microbiol 49:1523–1536. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cha JH, Stewart GC. 1997. The divIVA minicell locus of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 179:1671–1683. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1671-1683.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards DH, Errington J. 1997. The Bacillus subtilis DivIVA protein targets to the division septum and controls the site specificity of cell division. Mol Microbiol 24:905–915. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3811764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bramkamp M, Emmins R, Weston L, Donovan C, Daniel RA, Errington J. 2008. A novel component of the division-site selection system of Bacillus subtilis and a new mode of action for the division inhibitor MinCD. Mol Microbiol 70:1556–1569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patrick JE, Kearns DB. 2008. MinJ (YvjD) is a topological determinant of cell division in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 70:1166–1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sieger B, Schubert K, Donovan C, Bramkamp M. 2013. The lipid II flippase RodA determines morphology and growth in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol Microbiol 90:966–982. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu H, Chater KF, Deng Z, Tao M. 2008. A cellulose synthase-like protein involved in hyphal tip growth and morphological differentiation in Streptomyces. J Bacteriol 190:4971–4978. doi: 10.1128/JB.01849-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donovan C, Sieger B, Krämer R, Bramkamp M. 2012. A synthetic Escherichia coli system identifies a conserved origin tethering factor in Actinobacteria. Mol Microbiol 84:105–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kloosterman TG, Lenarcic R, Willis CR, Roberts DM, Hamoen LW, Errington J, Wu LJ. 2016. Complex polar machinery required for proper chromosome segregation in vegetative and sporulating cells of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 101:333–350. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliva MA, Halbedel S, Freund SM, Dutow P, Leonard TA, Veprintsev DB, Hamoen LW, Löwe J. 2010. Features critical for membrane binding revealed by DivIVA crystal structure. EMBO J 29:1988–2001. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sieger B, Bramkamp M. 2014. Interaction sites of DivIVA and RodA from Corynebacterium glutamicum. Front Microbiol 5:738. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Baarle S, Celik IN, Kaval KG, Bramkamp M, Hamoen LW, Halbedel S. 2013. Protein-protein interaction domains of Bacillus subtilis DivIVA. J Bacteriol 195:1012–1021. doi: 10.1128/JB.02171-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu LJ, Errington J. 2003. RacA and the Soj-Spo0J system combine to effect polar chromosome segregation in sporulating Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 49:1463–1475. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-Yehuda S, Rudner DZ, Losick R. 2003. RacA, a bacterial protein that anchors chromosomes to the cell poles. Science 299:532–536. doi: 10.1126/science.1079914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Claessen D, Emmins R, Hamoen LW, Daniel RA, Errington J, Edwards DH. 2008. Control of the cell elongation-division cycle by shuttling of PBP1 protein in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 68:1029–1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rismondo J, Cleverley RM, Lane HV, Grosshennig S, Steglich A, Möller L, Mannala GK, Hain T, Lewis RJ, Halbedel S. 2016. Structure of the bacterial cell division determinant GpsB and its interaction with penicillin-binding proteins. Mol Microbiol 99:978–998. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freitag NE, Port GC, Miner MD. 2009. Listeria monocytogenes–from saprophyte to intracellular pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:623–628. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camejo A, Carvalho F, Reis O, Leitao E, Sousa S, Cabanes D. 2011. The arsenal of virulence factors deployed by Listeria monocytogenes to promote its cell infection cycle. Virulence 2:379–394. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.5.17703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halbedel S, Hahn B, Daniel RA, Flieger A. 2012. DivIVA affects secretion of virulence-related autolysins in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol 83:821–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.07969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaval KG, Rismondo J, Halbedel S. 2014. A function of DivIVA in Listeria monocytogenes division site selection. Mol Microbiol 94:637–654. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry SE, Edwards DH. 2006. The Bacillus subtilis DivIVA protein has a sporulation-specific proximity to Spo0J. J Bacteriol 188:6039–6043. doi: 10.1128/JB.01750-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eswaramoorthy P, Winter PW, Wawrzusin P, York AG, Shroff H, Ramamurthi KS. 2014. Asymmetric division and differential gene expression during a bacterial developmental program requires DivIVA. PLoS Genet 10:e1004526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halbedel S, Kawai M, Breitling R, Hamoen LW. 2014. SecA is required for membrane targeting of the cell division protein DivIVA in vivo. Front Microbiol 5:58. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Briley K Jr, Prepiak P, Dias MJ, Hahn J, Dubnau D. 2011. Maf acts downstream of ComGA to arrest cell division in competent cells of B. subtilis. Mol Microbiol 81:23–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.dos Santos VT, Bisson-Filho AW, Gueiros-Filho FJ. 2012. DivIVA-mediated polar localization of ComN, a posttranscriptional regulator of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 194:3661–3669. doi: 10.1128/JB.05879-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szeto TH, Rowland SL, Rothfield LI, King GF. 2002. Membrane localization of MinD is mediated by a C-terminal motif that is conserved across eubacteria, archaea, and chloroplasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:15693–15698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232590599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motallebi-Veshareh M, Rouch DA, Thomas CM. 1990. A family of ATPases involved in active partitioning of diverse bacterial plasmids. Mol Microbiol 4:1455–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ginda K, Bezulska M, Ziolkiewicz M, Dziadek J, Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J, Jakimowicz D. 2013. ParA of Mycobacterium smegmatis co-ordinates chromosome segregation with the cell cycle and interacts with the polar growth determinant DivIVA. Mol Microbiol 87:998–1012. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monk IR, Gahan CG, Hill C. 2008. Tools for functional postgenomic analysis of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:3921–3934. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00314-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng L, Baumann U, Reymond JL. 2004. An efficient one-step site-directed and site-saturation mutagenesis protocol. Nucleic Acids Res 32:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnaud M, Chastanet A, Debarbouille M. 2004. New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, Gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:6887–6891. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6887-6891.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marston AL, Thomaides HB, Edwards DH, Sharpe ME, Errington J. 1998. Polar localization of the MinD protein of Bacillus subtilis and its role in selection of the mid-cell division site. Genes Dev 12:3419–3430. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishikawa S, Kawai Y, Hiramatsu K, Kuwano M, Ogasawara N. 2006. A new FtsZ-interacting protein, YlmF, complements the activity of FtsA during progression of cell division in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 60:1364–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halbedel S, Reiss S, Hahn B, Albrecht D, Mannala GK, Chakraborty T, Hain T, Engelmann S, Flieger A. 2014. A systematic proteomic analysis of Listeria monocytogenes house-keeping protein secretion systems. Mol Cell Proteomics 13:3063–3081. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.041327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]