ABSTRACT

Seasonal human influenza virus continues to cause morbidity and mortality annually, and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses along with other emerging influenza viruses continue to pose pandemic threats. Vaccination is considered the most effective measure for controlling influenza; however, current strategies rely on a precise vaccine match with currently circulating virus strains for efficacy, requiring constant surveillance and regular development of matched vaccines. Current vaccines focus on eliciting specific antibody responses against the hemagglutinin (HA) surface glycoprotein; however, the diversity of HAs across species and antigenic drift of circulating strains enable the evasion of virus-inhibiting antibody responses, resulting in vaccine failure. The neuraminidase (NA) surface glycoprotein, while diverse, has a conserved enzymatic site and presents an appealing target for priming broadly effective antibody responses. Here we show that vaccination with parainfluenza virus 5 (PIV5), a promising live viral vector expressing NA from avian (H5N1) or pandemic (H1N1) influenza virus, elicited NA-specific antibody and T cell responses, which conferred protection against homologous and heterologous influenza virus challenges. Vaccination with PIV5-N1 NA provided cross-protection against challenge with a heterosubtypic (H3N2) virus. Experiments using antibody transfer indicate that antibodies to NA have an important role in protection. These findings indicate that PIV5 expressing NA may be effective as a broadly protective vaccine against seasonal influenza and emerging pandemic threats.

IMPORTANCE Seasonal influenza viruses cause considerable morbidity and mortality annually, while emerging viruses pose potential pandemic threats. Currently licensed influenza virus vaccines rely on the antigenic match of hemagglutinin (HA) for vaccine strain selection, and most vaccines rely on HA inhibition titers to determine efficacy, despite the growing awareness of the contribution of neuraminidase (NA) to influenza virus vaccine efficacy. Although NA is immunologically subdominant to HA, and clinical studies have shown variable NA responses to vaccination, in this study, we show that vaccination with a parainfluenza virus 5 recombinant vaccine candidate expressing NA (PIV5-NA) from a pandemic influenza (pdmH1N1) virus or highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) virus elicits robust, cross-reactive protection from influenza virus infection in two animal models. New vaccination strategies incorporating NA, including PIV5-NA, could improve seasonal influenza virus vaccine efficacy and provide protection against emerging influenza viruses.

KEYWORDS: influenza, vaccine, neuraminidase, parainfluenza virus 5, highly pathogenic avian influenza virus

INTRODUCTION

Seasonal influenza virus causes annual epidemics, infecting 5 to 20% of the population annually and causing significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in high-risk groups such as infants and the elderly (1, 2). Emerging influenza viruses such as H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses infrequently infect humans, posing pandemic threats (3). Vaccination is considered the most effective approach to prevent influenza virus infection, disease, and transmission (2, 4).

Licensed influenza vaccines in the United States are of two varieties: (i) split, inactivated influenza virus (IIV) or recombinant protein vaccines containing the hemagglutinin (HA) antigen and (ii) live-attenuated influenza virus (LAIV) vaccines. IIV vaccines are injected intramuscularly (i.m.) or intradermally, eliciting antibody responses to the antigens in the vaccine. Only the HA antigen level is quantitated, and efficacy is based upon specific increases in the levels of serum antibodies as measured by a hemagglutination inhibition assay. In contrast, LAIV vaccines are delivered intranasally (i.n.), eliciting serum and mucosal antibody responses as well as cellular immune responses; however, the correlates of protection are poorly defined, with cellular, mucosal antibody, and serum antibody responses all potentially contributing (2, 4, 5). For both LAIV and IIV vaccines, an antigenic match of HA to the target strains (i.e., strains predicted to be circulating in the coming season or emerging, potentially pandemic viruses) as measured by sequence analysis and serology is the primary determinant for vaccine strain selection.

Neuraminidase (NA) constitutes 17% of the membrane proteins (6). Nevertheless, NA is present in all vaccines but the recently licensed Flublok influenza vaccine (Protein Sciences), which contains purified HA produced in insect cells (7). While NA-specific antibodies are elicited with vaccination, the NA content is not quantitated during vaccine licensure, and the immune response to NA is not considered in vaccine antigen selection (8).

Antibodies against NA have been shown to limit virus replication in vitro and provide a level of protection from infection (9–11), and human clinical trials have demonstrated that antibodies against NA correlate with reduced virus shedding and clinical disease (12). In contrast to HA-specific antibodies, which neutralize the virus (10, 13, 14), NA-specific antibodies trap progeny virus causing virus aggregation and reduce viral spread (8, 15, 16). Anti-NA antibodies may also interfere with initial virus entry (17). Importantly, while NA has diversity across subtypes, the globular head contains the enzymatic site that is highly conserved, increasing the potential for broadly cross-protective antibody responses against NA (8, 16).

While NA is immunogenic, it is subdominant to HA, and immune responses to NA are variable (8). However, NA-targeted vaccines have been shown to provide protection against homologous seasonal (H3N2), pandemic H1N1 (pH1N1), and H5N1 challenges in mice (18–21) and against homologous H5N1 challenge in nonhuman primates (22). Moreover, NA vaccines have also elicited intrasubtypic protection (i.e., N1 or N2 variants) in the mouse model (18–21). Approaches to deliver native NA antigens independent of HA, such as virus-vectored vaccines, have the potential to elicit protective, NA-specific immunity.

Parainfluenza virus 5 (PIV5), a nonsegmented, negative-stranded RNA virus (NNSV) in the Rubulavirus genus of the family Paramyxoviridae, is an appealing vaccine vector for multiple reasons. Recombinant PIV5 (rPIV5) is nonpathogenic, does not have a DNA phase in the life cycle (reducing the potential for integration), has a stable genome, and replicates to high titers without cytopathic effects in a variety of mammalian cell substrates (reviewed in reference 23). We previously demonstrated that rPIV5 vaccines expressing the HA gene from influenza A virus strain A/Udorn/72 (H3N2) (rPIV5-H3) or A/Vietnam/1203/04 (H5N1) (A/VN/1203-04) (rPIV5-H5) are safe and efficacious, providing protection against homologous influenza virus challenge in murine models (24–27). Moreover, the expression of the internal nucleocapsid (NP) protein, a dominant T cell antigen in mice, by PIV5 (rPIV5-NP) elicited heterosubtypic immunity in mice and provided protection against H1N1 and H5N1 challenges (28). Here we demonstrate that vaccination with separate rPIV5 constructs expressing NA from either HPAI A/Vietnam/1203/04 (H5N1) [rPIV5-N1(VN)] or A/California/04/09 (H1N1) (A/CA/04/09) [rPIV5-N1(CA)] elicits NA-specific antibody and T cell responses, conferring protection against homologous influenza virus challenge and considerable cross-protection against a heterologous influenza virus of the same subtype. There is also evidence of limited cross-protection against a virus of a different subtype (H3N2).

RESULTS

Recombinant PIV5-N1.

Plasmids containing PIV5 cDNA with an NA insertion flanked by a T7 RNA polymerase (RNAP) promoter, a hepatitis delta virus ribozyme, and a T7 terminator were generated by using methods similar to those reported previously (24–28). pZL108 encoding PIV5 with the N1 gene of A/California/04/09 (H1N1) inserted between the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN) and L genes or pZL116 encoding PIV5 with the N1 gene of A/VN/1203/04 (H5N1) was cotransfected into BSR-T7 cells with pPIV5-NP, pPIV5-P, and pPIV5-L encoding the NP, P, and L proteins of PIV5, respectively. The genomes of the rescued viruses rPIV5-N1(VN) and rPIV5-N1(CA) were sequenced to confirm that there were no mutations.

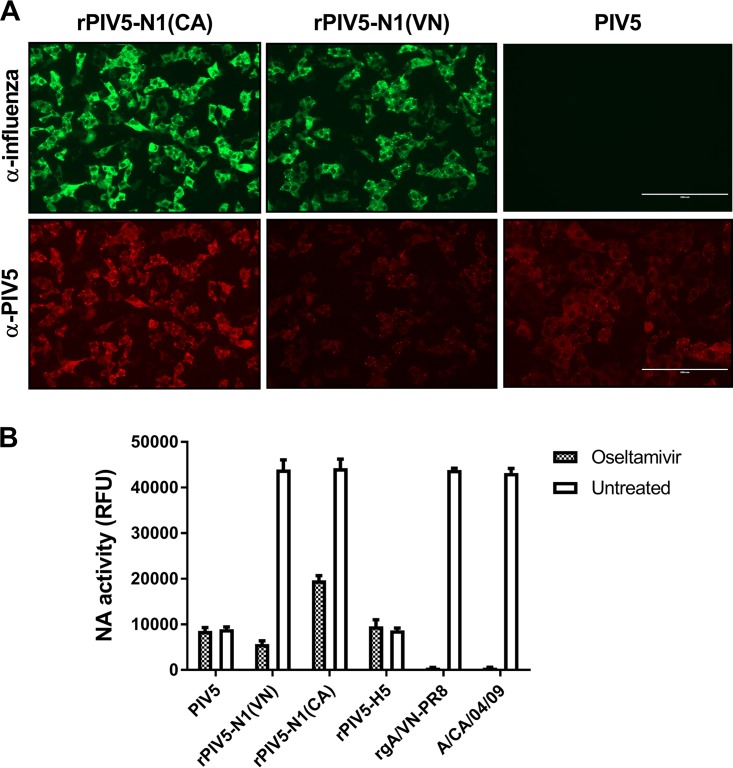

To confirm the expression of the recombinant NA (rNA) protein, Vero cells were infected with wild-type PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), or rPIV5-N1(CA) and assayed for NA expression by immunofluorescence staining using antisera generated against the parent influenza virus or PIV5. Both rPIV5-N1 viruses expressed the native NA antigen, while PIV5 alone was negative for influenza virus NA staining (Fig. 1A). Multistep growth curves of rPIV5-N1(VN) and rPIV5-N1(CA) demonstrated no effect on viral replication in vitro compared to wild-type PIV5 (data not shown).

FIG 1.

NA is expressed by PIV5-N1. (A) Immunofluorescence of Vero cells infected with PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), or rPIV5-N1(CA) at an MOI of 5. At 24 h postinfection, cells were fixed and stained with influenza virus-specific polyclonal antiserum-fluorescein isothiocyanate (green) (top) or anti-PIV5 (V/P)-PE monoclonal antibody (red) (bottom). Micrographs were taken at a ×20 magnification. (B) Equivalent titers of PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), rPIV5-N1(CA), and rPIV5-H5 and equivalent titers of rgA/VN-PR8 and A/CA/04/09 (normalized to the maximum RFU output of the rPIV5-N1 groups) were incubated with or without oseltamivir. The MUNANA substrate was then added, and NA activity was measured.

Expression and activity of NA on rPIV5-N1 virions.

To determine if active NA was incorporated into rPIV5-N1 virions, a neuraminidase activity assay was performed using equivalent titers of PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), rPIV5-N1(CA), and rPIV5-H5. Influenza VNH5N1-PR8/CDC-RG (rgA/VN-PR8) and A/CA/04/09 viruses were included as controls. PIV5 and rPIV5-H5 exhibited a low level of neuraminidase activity resulting from HN of PIV5, whereas rPIV5-N1(VN) and rPIV5-N1(CA) neuraminidase activities were significantly elevated (P < 0.05 compared to PIV5), to levels similar to those of the rgA/VN-PR8 and A/CA/04/09 influenza viruses (Fig. 1B). When treated with the influenza virus-specific NA inhibitor oseltamivir, the neuraminidase activities of rPIV5-N1(VN) and rPIV5-N1(CA) were decreased to PIV5 background levels (baseline HN activity), whereas rgA/VN-PR8 and A/CA/04/09 were completely inhibited. These findings suggest that not only is NA expressed on the surface of the rPIV5-N1 viruses, it also is expressed in an active form. Previous studies support that influenza virus antigens contained within PIV5 virions are immunogenic; however, antigens expressed during PIV5 infection are more effective at eliciting protective immune responses (26).

Immunogenicity of rPIV5-N1 vaccines.

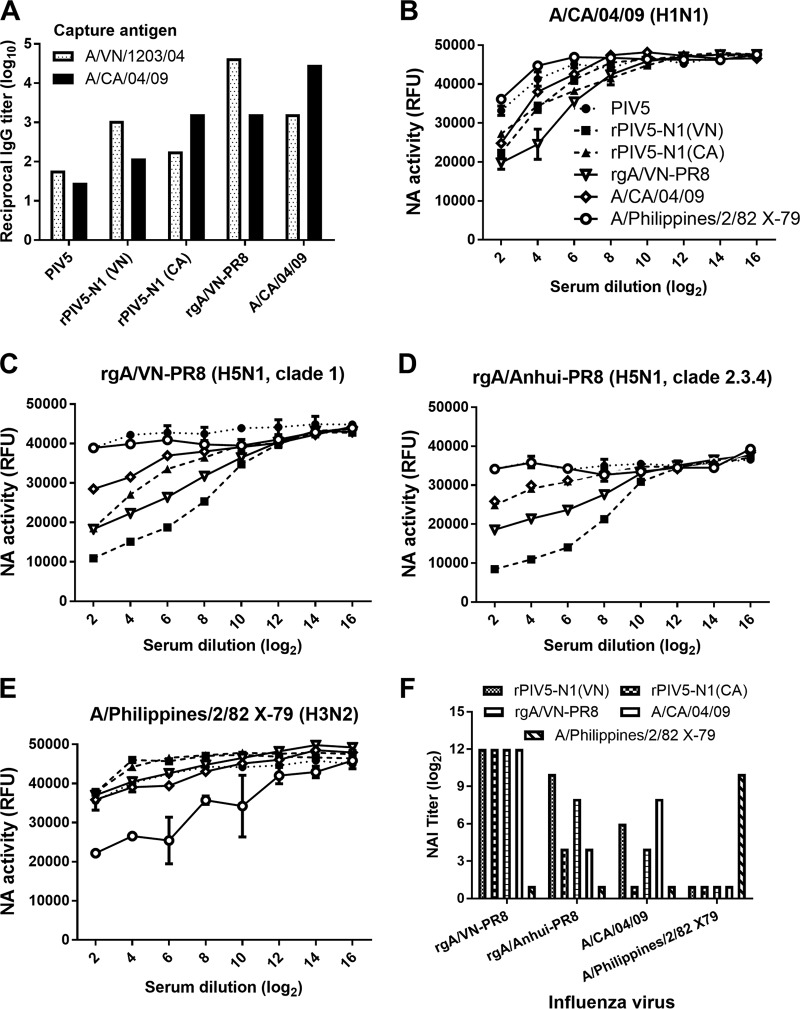

To determine if vaccination with rPIV5-N1 induces an NA-specific antibody response, BALB/c mice were vaccinated and boosted by i.n. inoculation with PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), or rPIV5-N1(CA). Positive-control mice were i.m. immunized with the rgA/VN-PR8 or A/CA/04/09 influenza virus. Mice were bled on day 21 postprime and on day 7 postboost (day 35 postpriming). Pooled serum from each vaccination group was assessed for levels of A/VN/1203/04- and A/CA/04/09-specific IgG by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Little to no A/VN/1203/04- or A/CA/04/09-specific IgG was detected in mice vaccinated with PIV5 (reciprocal titers of <20), whereas substantial levels of influenza virus-specific IgG were detected in mice immunized with rPIV5-N1(VN) or rPIV5-N1(CA) (Fig. 2A). While titers in influenza virus-immunized mice were higher than those in rPIV5-N1-immunized mice, reactivity in these animals reflected both HA- and NA-specific antibodies, compared to only NA-specific responses in rPIV5-N1-immunized mice (Fig. 2A). Although antibody levels specific for homologous viruses were higher, heterologous antibodies were also detected.

FIG 2.

Vaccination with rPIV5-N1 elicits influenza virus neuraminidase-inhibiting antibodies. Mice were primed and boosted with 106 PFU PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), or rPIV5-N1(CA) i.n. or 2 × 103 PFU rgA/VN-PR8, A/CA/04/09, or A/Philippines/2/82 X79 i.m. (A) On day 7 postboost, mice were bled, and their serum antibodies were assessed for A/VN/1203/04- or A/CA/04/09-specific IgG antibodies by an ELISA. (B to E) Serum was tested for NAI activity against NA of A/CA/04/09 (H1N1) (B), rgA/VN-PR8 (H5N1) (C), rgA/Anhui-PR8 (H5N1) (D), and A/Philippines/2/82 X79 (H3N2) (E). Data represent the mean RFU ± standard errors of the means. (F) Serum dilutions having significantly greater NAI than those of PIV5-specific serum (P < 0.05 by an ANOVA) were plotted for each antigen. Nonsignificant samples were arbitrarily given a titer of 1.

To determine whether the NA-specific antibodies could block specific neuraminidase activity, serum was analyzed in a 20-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-d-N-acetylneuraminic acid (MUNANA)-based NA inhibition (NAI) assay. Pooled sera from primed and boosted mice were tested against homologous rgA/VN-PR8 and A/CA/04/09 viruses as well as against a second reverse-genetics influenza virus expressing HA and NA from A/Anhui/01/2005 (H5N1 clade 2.3.4) (rgA/Anhui-PR8). Sera were also tested against a heterosubtypic virus, A/Philippines/2/82 X79 (H3N2) (X79). Serum from PIV5-vaccinated mice did not cause a measurable inhibition of NA activity against any influenza virus strain tested, whereas serum from mice vaccinated with rPIV5-N1(VN) or rgA/VN-PR8 strongly inhibited NA activities of both H5N1 viruses (Fig. 2C and D) and inhibited H1N1 NA activity to a lesser extent (Fig. 2B). Similarly, serum from mice immunized with rPIV5-N1(CA) or A/CA/04/09 inhibited the NA activity of A/CA/04/09. Sera from rPIV5-N1(CA)-immunized mice inhibited the NA activity of the H5N1 influenza viruses albeit not to the extent of the homologous virus rPIV5-N1(VN) (Fig. 2C and D). The human A/CA/04/09 virus was overall more resistant to serum-mediated NA inhibition than were the avian H5N1 viruses, suggesting that there are differences in the antigens rather than a defect in eliciting NAI-specific antibody responses by rPIV5-N1(CA). There was no evidence of heterosubtypic NAI activity against H3N2 influenza virus (Fig. 2E). Serum dilutions with significantly greater NAI activity (reduction in relative fluorescence units [RFU]) than that of PIV5-specific antisera were determined (P < 0.05), and the highest dilution was used as the NAI titer against that antigen (Fig. 2F). Sera not significantly different from PIV5 antisera were given an NAI titer of 1. Serum from N1-immunized mice significantly inhibited the NA activity of rgA/VN-PR8 to high dilutions (212) and inhibited rgA/Anhui-PR8 and A/CA/04/09 to lesser extents (24 to 210 dilutions). Strikingly, sera from rPIV5-N1-vaccinated mice inhibited H5N1 neuraminidase activity as least as well as or better than did immunization with a homologous virus.

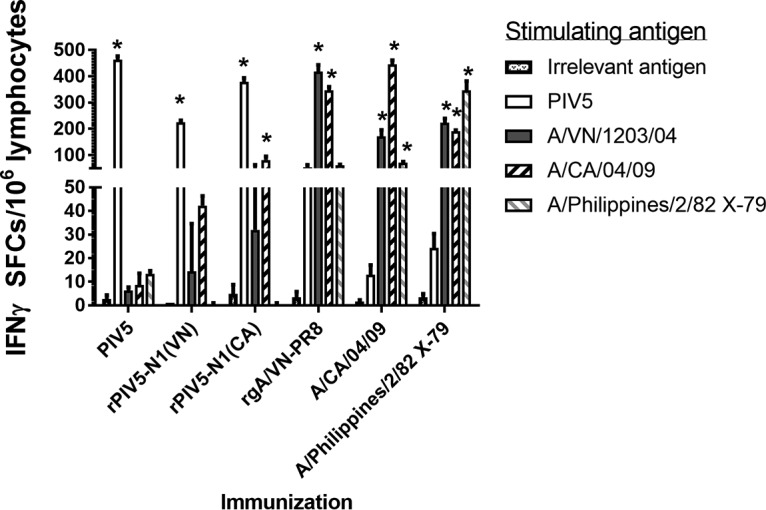

One advantage of live-virus-vectored vaccines is the potential to prime robust cell-mediated immune responses, which can contribute to protection, providing a more rapid clearance of infection (reviewed in reference 29). Thus, we assessed virus-specific T cell responses of rPIV5-N1-vaccinated mice and compared them to those of influenza virus-infected mice. Mice were immunized as described above, and on day 12 postimmunization, mice were euthanized, cells from mediastinal lymph nodes (MLN) were restimulated, and numbers of interferon gamma (IFN-γ)-producing lymphocytes were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay. Vaccination with rPIV5-N1(VN) or rPIV5-N1(CA) induced measurable influenza virus-specific T cell responses; however, the numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells were generally not different from those of control stimulated cells (Fig. 3). rPIV5-N1(CA)-immunized mice elicited substantially higher numbers of A/CA/04/09-specific T cells. Mice infected with influenza viruses had high numbers of IFN-producing cells, which were significantly higher than those of controls (Fig. 3) (P < 0.05); however, antigen responses in influenza virus-infected mice include immunodominant, NP-specific T cell responses in addition to other influenza virus antigens (30, 31), as opposed to targeting influenza virus NA alone.

FIG 3.

rPIV5-N1 primes cross-reactive T cell responses. BALB/c mice (n = 5 per group) were immunized with PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), or rPIV5-N1(CA) or with a sublethal dose of rgA/VN-PR8, A/CA/04/09, or A/Philippines/2/82 X79. On day 12 postvaccination, tissues were removed, lymphocytes from the mediastinal lymph nodes were stimulated as indicated, and numbers of IFN-γ-producing cells were measured via ELISpot analysis. Data are presented as means ± standard errors of the means (*, P < 0.05 compared to the irrelevant antigen, as determined by ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest analysis). SFCs, spot-forming cells.

Protection against homologous and heterologous influenza virus challenge.

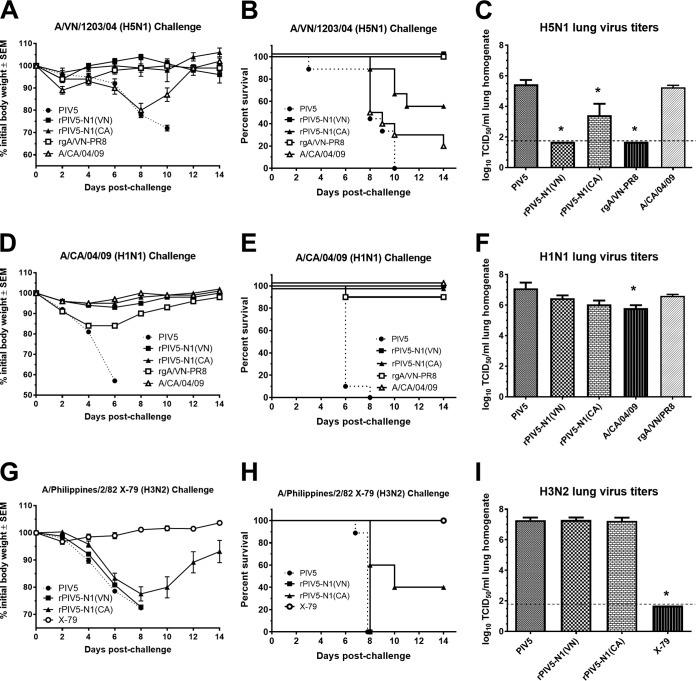

To determine if vaccination with rPIV5-N1 vaccines provides protection against homologous and heterologous influenza virus infections, immunized mice were challenged with HPAI H5N1 (A/Vietnam/1203/04), pandemic H1N1 (A/California/04/09), or heterosubtypic H3N2 (A/Philippines/2/82 X79) virus. BALB/c mice were immunized, challenged at 7 days postboost with 10 50% lethal doses (LD50) of influenza virus, and monitored for morbidity and mortality. All mice vaccinated with wild-type PIV5 showed decreases in body weight and were euthanized or succumbed to infection (Fig. 4). For the H5N1 challenge, homologous NA immunization [rPIV5-N1(VN)] provided complete protection from morbidity and mortality, with mice exhibiting no weight loss and no mortality, while mice vaccinated with heterologous NA from rPIV5-N1(CA) were protected from morbidity (Fig. 4A) and partially protected from mortality (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). Immunization with A/CA/04/09 elicited no protection against H5N1 challenge. For the H1N1 challenge, vaccination with A/CA/04/09, rPIV5-N1(CA), or rPIV5-N1(VN) provided complete protection from weight loss and mortality (Fig. 4D and E), while rgA/VN-PR8 provided incomplete but significant protection compared to that in control immunized mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4E). Finally, mice vaccinated with rPIV5-N1(CA) were partially protected from challenge with the heterosubtypic H3N2 virus, exhibiting weight loss (Fig. 4G) but having improved survival compared to that with control (PIV5) immunization (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4H). Only homologous (H3N2) (X79) immunization provided complete protection, with mice exhibiting no weight loss and no mortality after H3N2 challenge.

FIG 4.

Vaccination with rPIV5-N1 protects against homologous and heterologous influenza virus challenge. BALB/c mice were immunized i.n. with PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), or rPIV5-N1(CA) or i.m. with rgA/VN-PR8, A/CA/04/09, or A/Philippines/2/82 X79. On day 28 postpriming, mice were boosted. At 7 days postboosting, mice were challenged i.n. with 10 LD50 A/VN/1203/04 (A to C), A/CA/04/09 (D to F), or A/Philippines/2/82 X79 (G to I). (A, B, D, E, G, and H) Weights and humane endpoints of the mice (n = 10) were monitored and are presented as mean percentages of prechallenge body weights (A, D, and G) and percentages of mice surviving (B, E, and H) ± standard errors of the means. (C, F, and I) Challenge virus titers in the lungs on day 3 postchallenge (n = 5 per group) were measured by a TCID50 assay on MDCK cells. Data are presented as mean log-transformed TCID50 per milliliter of lung homogenate ± standard errors of the means. The limit of detection was 100 TCID50/ml (*, P < 0.05 as determined by a Kruskal-Wallis test).

A subset of mice from each challenge group was euthanized on day 3 postchallenge, and lung tissue was collected to assess lung virus titers by a 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay. Mice vaccinated with rPIV5-N1(VN) or A/VN/1203/04 had no detectable virus in their lungs, while rPIV5-N1(CA)-immunized mice had significantly reduced virus titers after H5N1 challenge compared to those of controls (P < 0.05). Immunization with A/CA/04/09 did not reduce virus titers (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, mice challenged with the A/CA/04/09 (H1N1) influenza virus showed little reduction in virus titers, with only A/CA/04/09-immunized mice showing any reduction (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4F). For H3N2-challenged mice, only X79-immunized mice exhibited any reduction in lung virus titers (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4I).

Taken together, these results indicate that immunization with recombinant PIV5 vaccines expressing influenza virus NA can provide protection against homologous and heterologous (cross-strain) influenza virus challenges at a level comparable to that with high-dose i.m. vaccination with homologous influenza virus strains [rPIV5-N1(CA)] (Fig. 4A to C). Moreover, rPIV5-N1(CA) immunization elicited heterosubtypic protection against H3N2 virus challenge (Fig. 4H).

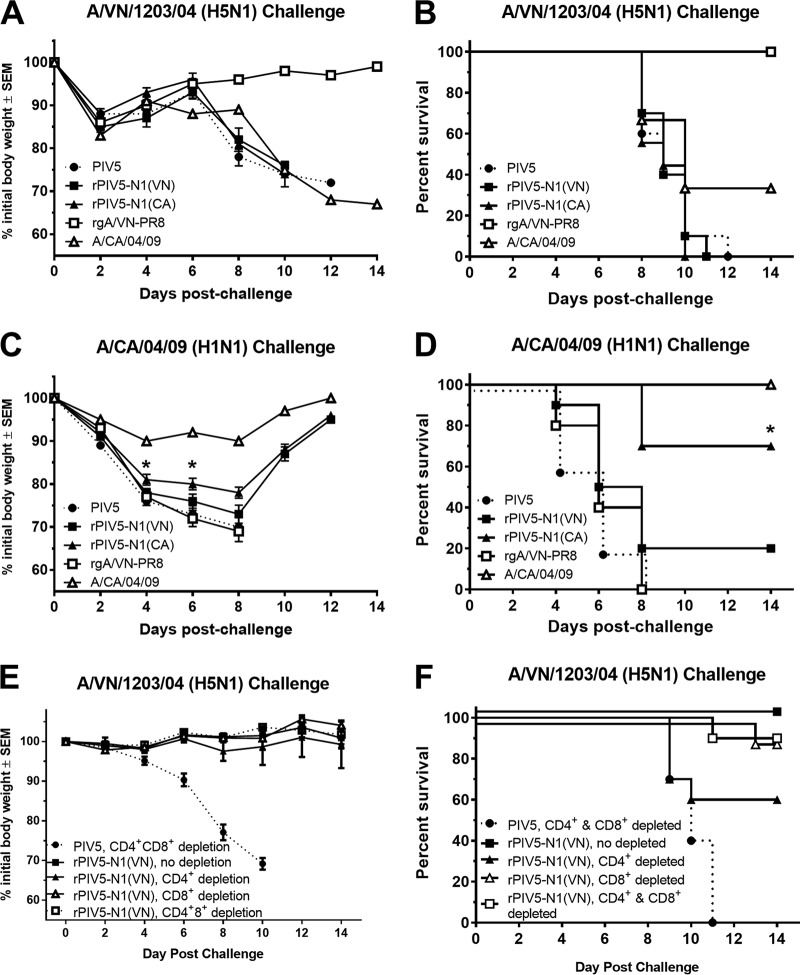

Recombinant PIV5-N1 vaccines elicited robust antibody and, to a lesser extent, T cell responses, both of which have been implicated in protection from influenza virus infection in rodents and humans (2, 29, 32). Thus, we assessed the contributions of humoral and cellular responses to rPIV5-N1 immunity. To determine the role of humoral immunity, antibodies were purified from hyperimmune serum collected from mice vaccinated with rPIV5-N1(VA), rPIV5-N1-(CA), PIV5, or the homologous challenge virus, and 200 μg IgG was passively transferred to naive mice. Mice were then i.n. challenged with A/VN/1203/04 (H5N1) or A/CA/04/09 (H1N1) and monitored for morbidity and mortality. Only passive antibodies from H5N1-immunized mice afforded protection against A/VN/1203/04 challenge (Fig. 5A and B). Mice given antibodies from homologous, rPIV5-N1(CA)-immunized mice were protected from lethal challenge with A/CA/04/09 H1N1, having considerably less weight loss on days 4 and 6 postchallenge (P < 0.05 as determined by analysis of variance [ANOVA]) (Fig. 5C) and a significant (P < 0.05) improvement in survival (70%) (Fig. 5D).

FIG 5.

Antibodies elicited by rPIV5-N1 can passively transfer protection, while T cells are not required for protection. A total of 200 μg of purified IgG from mice vaccinated with PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), rPIV5-N1(CA), rgA/VN-PR8, or A/CA/04/09 was transferred to a recipient mouse i.p. (A to D) The following day, mice were challenged with 10 LD50 A/VN/1203/04 (A and B) or A/CA/04/09 (C and D) and monitored for weight loss (A and C) and mortality (B and D). (E and F) Mice were vaccinated with PIV5 or rPIV5-N1(VN); depleted of CD4+, CD8+, or both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells or mock depleted; challenged with A/VN/1203/04; and monitored over 14 days for weight loss (E), humane endpoints, and survival (F).

As there was no survival benefit from the transfer of N1-specific antiserum against HPAI H5N1 challenge, the contribution of T cells was assessed. Twenty-one days after immunization with either PIV5 or rPIV5-N1(VN), mice were depleted of T cells by treatment with CD4+, CD8+, or both CD4+ and CD8+ monoclonal antibodies followed by a lethal challenge with HPAI H5N1 virus. Depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry (data not shown). Mice vaccinated with rPIV5-N1(VN) were protected from lethal challenge. Depletion of CD8+, CD4+, or CD4+ and CD8+ T cells had no effect on weight loss and reduced survival only slightly (Fig. 5E and F). However, survival rates of T cell-depleted mice were similar to those of nondepleted, rPIV5-N1(VN)-immunized mice (P > 0.05), suggesting that T cell-mediated immunity is not required for protection after rPIV5-N1(VN) immunization.

Recombinant PIV5-N1 protects against disease in ferrets.

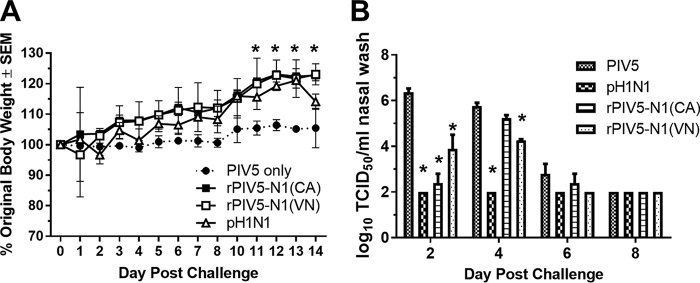

Ferrets were used to assess the efficacy of rPIV5-N1(CA) in protection against influenza virus replication. Ferrets were immunized i.n. with 107 PFU of PIV5, rPIV5-N1(CA), or rPIV5-N1(VN) or 105 PFU of A/CA/04/09. Twenty-one days after immunization, ferrets were challenged with 106 PFU of A/CA/04/09 and monitored for clinical signs, and nasal wash samples were collected on days 2, 4, 6, and 8 postchallenge. Influenza A/CA/04/09 virus causes limited clinical disease in ferrets (33); however, animals vaccinated with rPIV5-N1 or a homologous H1N1 virus had significantly (P < 0.05) higher weights late during infection (days 11 to 14) than did PIV5-vaccinated ferrets (Fig. 6A). Virus titers from nasal wash specimens were measured by a TCID50 assay. Ferrets immunized with the homologous A/CA/04/09 virus had no detectable virus. Ferrets immunized with rPIV5-N1(CA) or rPIV5-N1(VN) had significant (P < 0.05) reductions in virus titers on days 2 and 4 [rPIV5-N1(VN)] postchallenge (Fig. 6B). Thus, immunization with rPIV5-N1 reduced clinical symptoms and virus shedding caused by influenza virus infection in a second animal model.

FIG 6.

Immunization with rPIV5-N1 reduces clinical disease and virus shedding in ferrets. (A) Ferrets (n = 3 per group) were immunized with PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), rPIV5-N1(CA), or A/CA/04/09; challenged 21 days later with A/CA/04/09; and monitored for weight loss and clinical symptoms of disease. (B) Nasal wash specimens were collected on days 2, 4, 6, and 8 and assayed for virus titers by a TCID50 assay (*, P < 0.05 as determined by ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study suggest that influenza virus NA can be used as a vaccine antigen to provide strong cross-protective immunity. Recombinant PIV5-N1 incorporates enzymatically active NA in the virion, and rPIV5-N1-infected cells express NA. The enzymatic activity of NA has been associated with immunogenicity (34). In a murine model of influenza virus infection, vaccination with rPIV5-N1 elicited cross-reactive NAI serum antibody responses as well as IFN-γ-producing T cell responses. Recombinant PIV5-N1-vaccinated mice were protected against homologous and heterologous infections, including a stringent HPAI virus challenge. Moreover, immunization with rPIV5-N1(CA) provided partial protection against a heterosubtypic H3N2 virus challenge. The passive transfer of purified IgG resulted in various levels of protection, with antibodies providing protection against H1N1 but not H5N1 challenge. T cell depletion did not reduce rPIV5-N1 vaccine efficacy, suggesting that NA-specific antibodies may be sufficient in some cases; however, similarly to LAIV, immunity is likely multifaceted, utilizing serum antibody, mucosal antibody, and T cell responses for complete protection (5). Importantly, rPIV5-N1 reduced clinical symptoms to levels similar to those seen with previous infection with a homologous virus in the ferret model and significantly (P < 0.05) reduced virus shedding. Taken together, these results show that rPIV5-N1 is a promising vaccine candidate for seasonal and pandemic vaccination strategies.

Neuraminidase-specific antibodies have been associated with protection from influenza in humans (12). Here the passive transfer of IgG from rPIV5-N1-immunized mice provided partial protection against H1N1 challenge but no protection against H5N1 challenge. Several studies have tested cross-reactivity and the protective potential of NA-specific antibodies generated through vaccination and/or the passive transfer of antibodies. Sandbulte et al. showed partial protection from H5N1 challenge by the passive transfer of antiserum from mice immunized with an influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) NA-expressing plasmid (19). Differences in antigens, the amounts of antibody transferred, and the antibody isotypes transferred could explain the different outcomes. Vaccinia virus-expressed N1 from pdmH1N1 elicited antibodies that cross-reacted with and provided protection against homologous and heterologous (H5N1) challenges, while immunization with N1 of the H5N1 virus elicited weaker cross-reactive (pdmH1N1-inhibiting) antibody responses (35). Protective efficacy was not assessed in those studies. However, Wohlbold et al. utilized recombinant NA antigens to assess cross-reactivity and efficacy in a mouse model of immunization and challenge. Vaccination with rNA from A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) provided partial protection against pdmH1N1 or H5N1 infection but showed little NA-inhibiting antibody activity (21). That report also demonstrated protection by the passive transfer of an N2-specific antibody in an H3N2 murine challenge model but no heterosubtypic protection, leading to the conclusion that NA-specific antibodies could provide protection but most likely only against viruses of the same neuraminidase subtype (21). While the passive transfer of N1-specific antiserum did not provide protection against HPAI H5N1 challenge here, this could be due to the contribution of mucosal antibodies, which are elicited with i.n. rPIV5 immunization, which was not investigated in those studies (21, 26).

Cellular immune responses can also contribute to protection from influenza virus infection (29). Recombinant PIV5 elicits strong influenza virus-specific T cell responses to transgenes, as measured by IFN-γ production (25, 26, 28); however, the elicited responses to NA antigens, while measurable, were overall not noteworthy. Responses were measured after primary immunization rather than after boosting (36), which could contribute to the limited response. However, analysis of CD4+ T cell responses to A/CA/04/09 infection in BALB/c mice showed that NA-specific T cell responses are limited compared to HA- and NP-specific responses (37), so there may be a limited frequency of responding T cells in the BALB/c mouse model. Alternatively, the detection of NA-specific T cells may have been suboptimal with whole-virus antigens instead of peptide pools. While ELISpot assays did not differentiate CD4+ and CD8+ IFN-γ-producing T cells, data from specific T cell depletion studies suggest that neither CD4+ nor CD8+ T cells are required to maintain immunity afforded by rPIV5-N1 immunization.

The exploration of NA as a vaccine antigen for influenza virus is limited compared to that of HA, despite early evidence that serum antibodies specific for NA are associated with protection from influenza virus infection (11, 12, 38–40). Neuraminidase is immunologically subdominant to HA (8, 41). While NA is incorporated into licensed IIV vaccines, its level is not quantified, and the amount of NA relative to that of HA is variable. Outside of licensure, the NA contents of vaccines have been measured and vary considerably across vaccines, even within the same vaccine year (21). Not surprisingly, the immunogenicity of NA is variable across strains and vaccine preparations (21, 34, 42). The poor stability of NA has been proposed to be one mechanism behind the reduced immunogenicity, and vaccine storage outside recommended conditions can reduce NA immunogenicity (34). Previous studies utilizing recombinant NA in combination with IIV vaccination have shown that this combination elicits or increases NA-specific antibody responses and protects mice from infection (21, 43). Similar efficacy was seen by using N1-containing virus-like particles (VLPs) (44); however, those studies did not address concerns regarding NA stability. A licensed LAIV vaccine could eliminate NA stability concerns, as it is a replicating virus, but in recent in clinical trials, LAIV elicited poor NAI antibodies compared to those elicited by IIV (42, 45, 46). In contrast, vaccination with rPIV5-N1 elicited robust NAI titers, providing protection from influenza virus infection in two animal models. We speculate that PIV5-N1 allows NA to be expressed and recognized by the host immune system in the absence of HA in vivo. In cells infected with live influenza virus or in immune cells with inactivated influenza virus, NA is associated with HA, the immunodominant antigen, resulting in the decreased presentation of NA. It is possible that HA-free antigen presentation by PIV5-N1 allows NA to be more efficiently recognized.

While not expected, the potential for heterosubtypic protection was assessed by H3N2 challenge. Influenza virus H3N2-specific serum NAI antibodies were undetectable after rPIV5-N1(CA) immunization, but there was partial protection against A/Philippines/2/82 X79 (H3N2) challenge. Immunization with VLPs containing NA of A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) has been shown to provide protection against A/Philippines/2/82 X79 (H3N2) challenge, but the mechanism of protection was not determined (44). Here immunization with rPIV5-N1(CA) elicited significant numbers of IFN-γ-secreting cells upon stimulation with H3N2 virus, suggesting the presence of cross-reactive T cell responses; however, the contribution to heterosubtypic immunity was not assessed by the depletion of T cells. Kingstad-Bakke et al. described protection against H5N1 and H1N1 influenza virus challenges after vaccination with a raccoonpox virus vector expressing NA of A/VN/1203/04 (H5N1) (47). In contrast, there was no protection against H3N2 challenge, and protection against H5N1 challenge was partially abrogated upon CD4 and/or CD8 T cell depletion (47), although differences in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) haplotypes of A/J versus BALB/c mice (H2a versus H2d) may contribute to these differences. Nonneutralizing mucosal antibodies can also contribute to heterosubtypic immunity. Tumpey et al. demonstrated protection against H5N1 and H1N1 challenges after inactivated H3N2 virus immunization (48). Heterosubtypic immunity after mucosal H3N2 immunization was absent in B cell-deficient mice but was intact in beta-2 microglobulin-deficient mice, supporting a role for antibodies but not CD8 T cells. Notably, CD8 depletion partially reduced heterosubtypic immunity, suggesting a role for CD8 T cells, but was not a requirement during nonneutralizing immunity (48). Here protection against H3N2 challenge was likely multifactorial, including mucosal nonneutralizing antibodies and cellular immunity.

The expression of NA from A/CA/07/09 (pH1N1) in vaccinia virus vectors was reported previously (36). Modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) expressing N1 was tested in a murine model of influenza virus infection. MVA-N1 immunization elicited robust NAI antibodies and NA-specific T cell responses and, similar to rPIV5-N1(CA), partially reduced lung virus titers. Protection against lethal challenge was not assessed. While MVA-N1 shows promise, MVA doses of 106 and 107 PFU with a boost at day 21 were tested and provided incomplete protection. Here we show that two immunizations with 106 PFU of rPIV5-N1 provide complete protection from lethal challenge against homologous and heterologous challenges and, in the case of H5N1 challenge, can reduce virus replication to undetectable levels. Moreover, previous studies with rPIV5-HA suggest that immunization with doses as low as 103 PFU can elicit complete protection (25). While we have not tested lower doses of rPIV5-N1 or single immunizations in the mouse model, data from the ferret model suggest that a single immunization will reduce influenza virus shedding and provide protection from clinical disease.

As a vaccine antigen, neuraminidase would not necessarily stand alone but could be combined with HA or other conserved viral antigens, such as NP or M2 (28, 49, 50). Vaccination with NA individually or in addition to traditional vaccines could elicit more-balanced HA and NA responses (51, 52). Thus, rPIV5-N1/rPIV5-HA cocktails could be used to prime potent HA- and NA-specific antibody responses, providing neutralizing and NAI antibody responses with increased potential for cross-protection. Vaccination strategies considering NA in strain selection and/or incorporating an NA antigen into a vaccine have the potential to improve vaccine efficacy, even in the case of a poor vaccine match with seasonal and emerging influenza viruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Influenza viruses.

Reverse-genetics H5N1 influenza vaccine strains VNH5N1-PR8/CDC-RG (H5N1, clade 1) (rgA/VN-PR8) and A/Anhui/01/2005 (H5N1)-PR8-IBCDC-RG6 (H5N1, clade 2.3.4) (rgA/Anhui-PR8) (both generously provided by Rubin Donis, CDC) and A/Philippines/2/82 X79 (H3N2) (X79), a 2:6 reassortant with A/PR8/34 (generously provided by Suzanne Epstein, FDA), were propagated in the allantoic cavity of embryonated hen eggs at 37°C for 48 to 72 h. A/CA/04/09 (generously provided by Alexander Klimov, CDC) and mouse-adapted A/CA/04/09 (MA) (generously provided by Daniel Perez, University of Georgia) were grown in cell culture in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. β-Propiolactone (BPL)-inactivated A/Vietnam/1203/04 was provided by Richard Webby, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A/VN/1203/2004 (H5N1) virus was propagated in the allantoic cavity of embryonated hen eggs at 37°C for 22 h. All viruses were clarified by centrifugation, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C. All experiments using live, highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses were reviewed and approved by the institutional biosafety program at the University of Georgia and were conducted with biosafety level 3 (BSL3) enhanced containment according to guidelines for the use of select agents approved by the CDC.

Animals.

Female 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice (Charles River Labs, Frederick, MD) were used for all murine studies. Mouse immunizations and infections with BSL2 viruses were performed in animal biosafety level 2 (ABSL2) facilities in HEPA-filtered isolators. Mouse HPAI virus infections were performed in enhanced BSL3 facilities according to guidelines approved by the institutional biosafety program at the University of Georgia and for the use of select agents approved by the CDC. For ferret studies, male Fitch ferrets (∼800 g; Triple F Farms, Sayre, PA) were housed in pairs, acclimated, and confirmed to be influenza virus seronegative prior to immunization. Ferrets were microchipped with a transponder for identification and temperature measurement. All animal studies were conducted according to guidelines approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Georgia.

Cell culture.

Monolayer cultures of BSR-T7 cells for the rescue of rPIV5 were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10% tryptose phosphate broth (TPB), and 400 μg/ml G418. BHK cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Madin-Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) and MDCK cells were cultured in DMEM with 5% FBS, 5% l-glutamine, and an antibiotic-antimycotic solution (10,000 IU/ml penicillin, 10,000 μg/ml streptomycin, and 25 μg/ml amphotericin B) (Cellgro Mediatech, Inc.). Vero-E6 cells were cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM) (Thermo/HyClone) with 10% FBS and antibiotic-antimycotic. All cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Construction and rescue of recombinant viruses.

Two recombinant PIV5 viruses containing the NA gene between the HN and L genes, ZL108 (rPIV5-H1N1-N1-HN/L) and ZL116 (rPIV5-H5N1-N1-HN/L), were generated as previously described (24–28). Plasmid pZL108 or pZL116 and three helper plasmids, pPIV5-NP, pPIV5-P, and pPIV5-L, encoding the NP, P, and L proteins, respectively, were cotransfected into BSR-T7 cells, and after 72 h of incubation at 37°C, the media were harvested and cell debris was pelleted by low-speed centrifugation (3,000 rpm for 10 min). Single clones of recombinant viruses were plaque purified and sequenced.

PIV5 and rPIV5 stocks were grown in MDBK cells. Medium was collected and clarified by centrifugation, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) was added to 1%. Virus stocks were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Virus titers were then determined by a plaque assay.

Virus quantification.

PIV5 titers were determined by a plaque assay on Vero cells as previously reported (24, 26). Briefly, cells were incubated with serial dilutions of the virus for 2 h, the virus was removed, and cells were overlaid with 1:1 low-melting-point agarose and DMEM with 2% FBS plus antibiotic-antimycotic and incubated at 37°C for 5 to 6 days. Cell monolayers were fixed with 10% buffered formalin and immunostained by using PIV5 V/P-specific antibody. Influenza virus titers were determined by either a TCID50 assay or a plaque assay on MDCK cells, as previously described (24–26, 28). Briefly, for plaque assays, MDCK cells in 24-well plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with serial dilutions of virus samples made in MEM with 1 μg/ml TPCK [l-(tosylamido-2-phenyl) ethyl chloromethyl ketone]-treated trypsin (Worthington Biochemical). Diluted virus samples were then removed, and monolayers were overlaid with 1.2% Avicel microcrystalline cellulose with 1 mg/ml TPCK-treated trypsin. Plates were incubated for 72 h; the overlay was gently washed off with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS); the plates were then fixed with cold methanol-acetone (40%–60%), air dried, and counterstained with crystal violet; and plaques were visualized. For TCID50 assays, 10-fold serial dilutions of virus-containing samples were added to 96-well plates containing MDCK cells in MEM with 1 μg/ml TPCK-treated trypsin. Plates were incubated for 48 to 72 h at 37°C, and the supernatants were then assayed for influenza virus by agglutination of turkey red blood cells. The 50% tissue culture infectious dose was determined by using the Spearman-Karber method (53).

Immunofluorescence assays.

Vero cells were grown in 24-well plates and infected with PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), or rPIV5-N1(CA) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 PFU/cell. At 24 h postinfection, cells were fixed with 5% buffered formalin for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized and then incubated for 1 h with a 1:1,000 dilution (1 μg/ml) of PIV5 V/P-specific monoclonal antibody. A 1:250 dilution of phycoerythrin (PE)–goat anti-mouse Ig (BD Pharmingen) was applied for 45 min to detect HA. To detect NA, hyperimmune serum was generated against each virus (rgA/VN-PR8 or A/CA/04/09). To visualize NA, an Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibody (Invitrogen), diluted 1:500, was added, and the plate was incubated for 30 min and then washed. A total of 0.5 ml PBS was added to each well, and fluorescence was examined by using an AMS Evos fl fluorescence microscope.

Immunization.

For vaccination with PIV5 and rPIV5-N1, 106 PFU PIV5, rPIV5-N1(VN), or rPIV5-N1(CA) in 50 μl PBS was administered intranasally to mice anesthetized with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol in tert-amyl alcohol (Avertin; Aldrich Chemical Co.). For i.m. vaccination with rgA/VN-PR8, A/CA/04/09, or A/Philippines/2/82 X79, 2,000 PFU of each virus in 50 μl PBS was injected into the caudal thigh muscle. Blood was collected on day 21 postimmunization. For boosting, immunization was repeated on day 28 postprime.

ELISA.

Immulon 2 HB 96-well microtiter plates (ThermoLabSystems) were coated with 10 hemagglutinating units (HAU) of inactivated A/VN/1203/04 or A/CA/04/09 diluted in PBS and incubated at 4°C overnight. Plates were then washed and blocked with 200 μl wash solution (KPL) with 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.5% BSA (blocking buffer) for 1 h at room temperature. Serial dilutions of pooled serum samples in blocking buffer were transferred to the coated plate and incubated for 1 h. Alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (KPL, Inc.) in blocking buffer was added, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were developed by using the p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) phosphatase substrate (KPL, Inc.), and the optical density at 405 nm (OD405) was measured on a Bio-Tek PowerWave XS plate reader. The recorded IgG titer was the reciprocal of the lowest serum dilution with an OD higher than the mean OD plus 2 standard deviations for naive serum.

Neuraminidase assay and neuraminidase inhibition assay.

The NA and NAI assays were performed by using an NA-Fluor Influenza Neuraminidase assay kit. For neuraminidase activity, titers of virus stocks (rPIV5 constructs and influenza viruses) were determined according to the manufacturer's instructions for the NA-Fluor Influenza Neuraminidase assay kit (Applied Biosystems). The virus dilution used for the NAI assay was normalized for each virus as the highest dilution on the linear range of RFU. To determine NA expression by rPIV5-N1 viruses, equivalent titers of PIV5 and rPIV5-N1 were assayed, with some groups being treated with 10,000 nM oseltamivir, and RFU readouts were taken to assess knockdown. NAI assays were also performed to detect neuraminidase-inhibiting serum antibody levels. Twofold dilutions of pooled sera were performed with an initial dilution of 1:4. The assay was then performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Oseltamivir was included as a control.

ELISpot assay.

MLN were collected at 12 days postimmunization, pooled, and homogenized. Cells were cultured at the indicated numbers with inactivated A/VN/1203/04 or A/CA/04/09 (10 HAU per well), Ebola virus GP P2 EYLFEVDNL (irrelevant peptide) (1 μg/ml), or concanavalin A (2 μg/ml) in 0.2 ml on 96-well ELISpot plates coated with IFN-γ-specific antibody for 48 h. IFN-γ-producing cells were detected by using a specific antibody and visualized, and spots were counted by using an Aid ViruSpot reader (Cell Technology, Inc.).

Influenza virus challenges of mice.

Vaccinated mice were anesthetized by using 2,2,2-tribromoethanol in tert-amyl alcohol and challenged intranasally with 10 LD50 A/Vietnam/1203/04, A/California/04/09, or A/Philippines/2/82 diluted in 50 μl PBS. Mice were then monitored daily for morbidity and mortality, with body weights being measured every other day. On day 3 postchallenge, groups of mice were euthanized, and their lungs were collected into 1.0 ml PBS and homogenized. The homogenate was then cleared by centrifugation, and viral titers were determined by a TCID50 assay as described above. For passive-transfer studies, 200 μg purified IgG from PIV5-, rPIV5-N1(VN)-, rPIV5-N1(CA)-, rgA/VN-PR8-, and A/CA/04/09-vaccinated mice was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) to naive mice. Mice were challenged with A/Vietnam/1203/04 or A/CA/04/09 the day after transfer. For T cell depletion studies, mice were vaccinated as described above, and on days 3, 2, and 1 prior to challenge, mice received 100 μg of the rat IgG2b isotype control (clone LTF-2), anti-mouse CD4 (clone GK1.5), anti-mouse CD8 (clone 2.43), or anti-mouse CD4 and anti-mouse CD8. T cell depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry of peripheral blood and spleen tissue assayed on days 0 and 7 postchallenge. Data from all studies are representative of results from at least two experiments.

Influenza virus challenges of ferrets.

Ferrets were anesthetized with ketamine-glycopyrrolate-dexmedetomidine and inoculated i.n. with 107 PFU of PIV5, rPIV5-N1(CA), or rPIV5-N1(VN) or 105 PFU of A/CA/04/09 in 0.5 ml PBS. Ferrets were challenged i.n. 21 days later, under anesthesia, with 106 PFU A/CA/04/09 in 0.4 ml PBS. Ferrets were monitored daily for clinical signs and weighed daily for 14 days. On days 2, 4, 6, and 8 postchallenge, ferrets were lightly anesthetized with ketamine, and nasal wash samples were collected as previously described (54). Results are representative of data from two independent experiments.

Statistical analyses.

Comparisons were performed by using GraphPad Prism version 5.0, with significance being set at a P value of <0.05. Differences in NAI activity were compared by 2-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest, with comparison to PIV5-specific antisera. Differences in mouse and ferret weight losses and nasal wash titers were measured by 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures, followed by a Bonferroni multiple-comparisons test. Survival analysis was done by using a log rank test, followed by comparison using the Bonferroni correction for significance. Differences in lung virus titers were measured by a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple-comparison test.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

B.H. is the inventor for a patent on parainfluenza virus 5-based vaccines, which is owned by the University of Georgia Research Foundation (UGARF). UGARF has licensed the patent to companies for vaccine development. B.H. owns substantial stake in CyanVac LLC and Wuhan Saitekang Biotech, Inc., which are developing vaccines.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (grant R01AI070847) to B.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Molinari NA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Messonnier ML, Thompson WW, Wortley PM, Weintraub E, Bridges CB. 2007. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine 25:5086–5096. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Recommend Rep 62:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. 2015. Influenza at the human-animal interface. Summary and assessment as of 1 May 2015. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grohskopf LA, Olsen SJ, Sokolow LZ, Bresee JS, Cox NJ, Broder KR, Karron RA, Walter EB, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States, 2014-15 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63:691–697. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MedImmune Vaccines, Inc. 2015. FluMist package insert. MedImmune Vaccines, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nayak DP, Balogun RA, Yamada H, Zhou ZH, Barman S. 2009. Influenza virus morphogenesis and budding. Virus Res 143:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Protein Sciences Corporation. 2014. Flublok (influenza vaccine) package insert. Protein Sciences Corporation, Meriden, CT. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wohlbold TJ, Krammer F. 2014. In the shadow of hemagglutinin: a growing interest in influenza viral neuraminidase and its role as a vaccine antigen. Viruses 6:2465–2494. doi: 10.3390/v6062465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webster RG, Laver WG. 1967. Preparation and properties of antibody directed specifically against the neuraminidase of influenza virus. J Immunol 99:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilbourne ED, Laver WG, Schulman JL, Webster RG. 1968. Antiviral activity of antiserum specific for an influenza virus neuraminidase. J Virol 2:281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulman JL, Khakpour M, Kilbourne ED. 1968. Protective effects of specific immunity to viral neuraminidase on influenza virus infection of mice. J Virol 2:778–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy BR, Kasel JA, Chanock RM. 1972. Association of serum anti-neuraminidase antibody with resistance to influenza in man. N Engl J Med 286:1329–1332. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197206222862502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson BE, Grajower B, Kilbourne ED. 1993. Infection-permissive immunization with influenza virus neuraminidase prevents weight loss in infected mice. Vaccine 11:1037–1039. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(93)90130-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powers DC, Kilbourne ED, Johansson BE. 1996. Neuraminidase-specific antibody responses to inactivated influenza virus vaccine in young and elderly adults. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 3:511–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seto JT, Chang FS. 1969. Functional significance of sialidase during influenza virus multiplication: an electron microscope study. J Virol 4:58–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcelin G, Sandbulte MR, Webby RJ. 2012. Contribution of antibody production against neuraminidase to the protection afforded by influenza vaccines. Rev Med Virol 22:267–279. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matrosovich MN, Matrosovich TY, Gray T, Roberts NA, Klenk H-D. 2004. Neuraminidase is important for the initiation of influenza virus infection in human airway epithelium. J Virol 78:12665–12667. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12665-12667.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Z, Kadowaki S, Hagiwara Y, Yoshikawa T, Matsuo K, Kurata T, Tamura S. 2000. Cross-protection against a lethal influenza virus infection by DNA vaccine to neuraminidase. Vaccine 18:3214–3222. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandbulte MR, Jimenez GS, Boon ACM, Smith LR, Treanor JJ, Webby RJ. 2007. Cross-reactive neuraminidase antibodies afford partial protection against H5N1 in mice and are present in unexposed humans. PLoS Med 4:e59. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu W-C, Lin C-Y, Tsou Y-T, Jan J-T, Wu S-C. 6 May 2015. Cross-reactive neuraminidase-inhibiting antibodies elicited by immunization with recombinant neuraminidase proteins of H5N1 and pH1N1 influenza A viruses. J Virol doi: 10.1128/JVI.00585-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wohlbold TJ, Nachbagauer R, Xu H, Tan GS, Hirsh A, Brokstad KA, Cox RJ, Palese P, Krammer F. 2015. Vaccination with adjuvanted recombinant neuraminidase induces broad heterologous, but not heterosubtypic, cross-protection against influenza virus infection in mice. mBio 6:e02556-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02556-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiNapoli JM, Nayak B, Yang L, Finneyfrock BW, Cook A, Andersen H, Torres-Velez F, Murphy BR, Samal SK, Collins PL, Bukreyev A. 2010. Newcastle disease virus-vectored vaccines expressing the hemagglutinin or neuraminidase protein of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus protect against virus challenge in monkeys. J Virol 84:1489–1503. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01946-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mooney AJ, Tompkins SM. 2013. Experimental vaccines against potentially pandemic and highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses. Future Virol 8:25–41. doi: 10.2217/fvl.12.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, Gabbard JD, Mooney A, Chen Z, Tompkins SM, He B. 2013. Efficacy of parainfluenza virus 5 mutants expressing hemagglutinin from H5N1 influenza A virus in mice. J Virol 87:9604–9609. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01289-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z, Mooney AJ, Gabbard JD, Gao X, Xu P, Place RJ, Hogan RJ, Tompkins SM, He B. 2013. Recombinant parainfluenza virus 5 expressing hemagglutinin of influenza A virus H5N1 protected mice against lethal highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 challenge. J Virol 87:354–362. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02321-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mooney AJ, Li Z, Gabbard JD, He B, Tompkins SM. 2013. Recombinant parainfluenza virus 5 vaccine encoding the influenza virus hemagglutinin protects against H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus infection following intranasal or intramuscular vaccination of BALB/c mice. J Virol 87:363–371. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02330-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tompkins SM, Lin Y, Leser GP, Kramer KA, Haas DL, Howerth EW, Xu J, Kennett MJ, Durbin JE, Tripp RA, Lamb RA, He B. 2007. Recombinant parainfluenza virus 5 (PIV5) expressing the influenza A virus hemagglutinin provides immunity in mice to influenza A virus challenge. Virology 362:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z, Gabbard JD, Mooney A, Gao X, Chen Z, Place RJ, Tompkins SM, He B. 2013. Single-dose vaccination of a recombinant parainfluenza virus 5 expressing NP from H5N1 virus provides broad immunity against influenza A viruses. J Virol 87:5985–5993. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00120-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant EJ, Chen L, Quinones-Parra S, Pang K, Kedzierska K, Chen W. 2014. T-cell immunity to influenza A viruses. Crit Rev Immunol 34:15–39. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.2013010019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen W, Antón LC, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. 2000. Dissecting the multifactorial causes of immunodominance in class I-restricted T cell responses to viruses. Immunity 12:83–93. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belz GT, Xie W, Doherty PC. 2001. Diversity of epitope and cytokine profiles for primary and secondary influenza A virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses. J Immunol 166:4627–4633. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potter CW, Oxford JS. 1979. Determinants of immunity to influenza infection in man. Br Med Bull 35:69–75. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith JH, Nagy T, Driskell E, Brooks P, Tompkins SM, Tripp RA. 2011. Comparative pathology in ferrets infected with H1N1 influenza A viruses isolated from different hosts. J Virol 85:7572–7581. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00512-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sultana I, Yang K, Getie-Kebtie M, Couzens L, Markoff L, Alterman M, Eichelberger MC. 2014. Stability of neuraminidase in inactivated influenza vaccines. Vaccine 32:2225–2230. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Changsom D, Lerdsamran H, Wiriyarat W, Chakritbudsabong W, Siridechadilok B, Prasertsopon J, Noisumdaeng P, Masamae W, Puthavathana P. 2016. Influenza neuraminidase subtype N1: immunobiological properties and functional assays for specific antibody response. PLoS One 11:e0153183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hessel A, Schwendinger M, Fritz D, Coulibaly S, Holzer GW, Sabarth N, Kistner O, Wodal W, Kerschbaum A, Savidis-Dacho H, Crowe BA, Kreil TR, Barrett PN, Falkner FG. 2010. A pandemic influenza H1N1 live vaccine based on modified vaccinia Ankara is highly immunogenic and protects mice in active and passive immunizations. PLoS One 5:e12217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alam S, Sant AJ. 2011. Infection with seasonal influenza virus elicits CD4 T cells specific for genetically conserved epitopes that can be rapidly mobilized for protective immunity to pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. J Virol 85:13310–13321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05728-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schulman JL. 1969. The role of antineuraminidase antibody in immunity to influenza virus infection. Bull World Health Organ 41:647–650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allan WH, Madeley CR, Kendal AP. 1971. Studies with avian influenza A viruses: cross protection experiments in chickens. J Gen Virol 12:79–84. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-12-2-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rott R, Becht H, Orlich M. 1974. The significance of influenza virus neuraminidase in immunity. J Gen Virol 22:35–41. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-22-1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johansson BE, Moran TM, Bona CA, Popple SW, Kilbourne ED. 1987. Immunologic response to influenza virus neuraminidase is influenced by prior experience with the associated viral hemagglutinin. II. Sequential infection of mice simulates human experience. J Immunol 139:2010–2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Couch RB, Atmar RL, Keitel WA, Quarles JM, Wells J, Arden N, Niño D. 2012. Randomized comparative study of the serum antihemagglutinin and antineuraminidase antibody responses to six licensed trivalent influenza vaccines. Vaccine 31:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johansson BE, Pokorny BA, Tiso VA. 2002. Supplementation of conventional trivalent influenza vaccine with purified viral N1 and N2 neuraminidases induces a balanced immune response without antigenic competition. Vaccine 20:1670–1674. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00490-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quan F-S, Kim M-C, Lee B-J, Song J-M, Compans RW, Kang S-M. 2012. Influenza M1 VLPs containing neuraminidase induce heterosubtypic cross-protection. Virology 430:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monto AS, Petrie JG, Cross RT, Johnson E, Liu M, Zhong W, Levine M, Katz JM, Ohmit SE. 8 April 2015. Antibody to influenza virus neuraminidase: an independent correlate of protection. J Infect Dis doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petrie JG, Ohmit SE, Johnson E, Truscon R, Monto AS. 26 May 2015. Persistence of antibodies to influenza hemagglutinin and neuraminidase following one or two years of influenza vaccination. J Infect Dis doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kingstad-Bakke B, Kamlangdee A, Osorio JE. 2015. Mucosal administration of raccoonpox virus expressing highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza neuraminidase is highly protective against H5N1 and seasonal influenza virus challenge. Vaccine 33:5155–5162. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tumpey TM, Renshaw M, Clements JD, Katz JM. 2001. Mucosal delivery of inactivated influenza vaccine induces B-cell-dependent heterosubtypic cross-protection against lethal influenza A H5N1 virus infection. J Virol 75:5141–5150. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5141-5150.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Epstein SL, Tumpey T, Misplon JA, Lo C-Y, Cooper LA, Subbarao K, Rensaw M, Sambhara S, Katz JM. 2002. DNA vaccine expressing conserved influenza virus proteins protective against H5N1 challenge infection in mice. Emerg Infect Dis 8:796–801. doi: 10.3201/eid0805.010476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tompkins SM, Zhao Z-S, Lo C-Y, Misplon JA, Liu T, Ye Z, Hogan RJ, Wu Z, Benton KA, Tumpey TM, Epstein SL. 2007. Matrix protein 2 vaccination and protection against influenza viruses, including subtype H5N1. Emerg Infect Dis 13:426–435. doi: 10.3201/eid1303.061125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johansson BE, Bucher DJ, Kilbourne ED. 1989. Purified influenza virus hemagglutinin and neuraminidase are equivalent in stimulation of antibody response but induce contrasting types of immunity to infection. J Virol 63:1239–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bosch BJ, Bodewes R, de Vries RP, Kreijtz JHCM, Bartelink W, van Amerongen G, Rimmelzwaan GF, de Haan CAM, Osterhaus ADME, Rottier PJM. 2010. Recombinant soluble, multimeric HA and NA exhibit distinctive types of protection against pandemic swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza virus infection in ferrets. J Virol 84:10366–10374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01035-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hierholzer JC, Killington RA. 1996. Virus isolation and quantitation, p 25–46. In Mahy BWJ, Kangro HO (ed), Virology methods manual. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Driskell EA, Pickens JA, Humberd-Smith J, Gordy JT, Bradley KC, Steinhauer DA, Berghaus RD, Stallknecht DE, Howerth EW, Tompkins SM. 2012. Low pathogenic avian influenza isolates from wild birds replicate and transmit via contact in ferrets without prior adaptation. PLoS One 7:e38067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]