Abstract

Objective:

To examine the association between Quran memorization and health among older men.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study included older Saudi men (age ≥ 55 years) from Buraidah, Al-Qassim. The neighborhoods were selected randomly (20 out of 96); eligible men from the mosques were recruited. Demographics, lifestyle, and depression were assessed with standardized questionnaires; height, weight, blood pressure, and random blood glucose (glucometer) were measured with standard protocol.

Results:

The mean and standard deviation for age, body mass index, and Quran memorization were 63 years (7.5), 28.9 kg/m2 (4.8), and 4.3 sections (6.9). Prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and depression were 71%, 29%, and 22%, respectively. Those who memorized at least 10 sections of Quran were 64%, 71%, and 81% less likely to have hypertension, diabetes, and depression compared to those who memorized less than 0.5 sections, after controlling for covariates.

Conclusion:

There was a strong linear association between Quran memorization and hypertension, diabetes, and depression indicating that those who had memorized a larger portion of the Quran were less likely to have one of these chronic diseases. Future studies should explore the potential health benefits of Quran memorization and the underlying mechanisms.

Keywords: Memorization, older men, chronic disease, Quran

Introduction

Most data pertaining to the relationship between religious activity and health outcomes come primarily from studying people of the Christian faith.1 More often than not, religious practices were associated with self-reported better general health and a higher quality of life (mental and physical health).2,3 Religious practices were also found to be beneficial for non-cardiovascular outcomes, for example, shorter duration in vegetative state among head injury patients,4 higher pregnancy among infertile women,5 lower mortality among sepsis patients,6 and better immunity among older adults.7,8 However, the effect of religious practices on cardiovascular outcomes was mixed. The literature addressed outcomes such as hypertension, myocardial infarction, and coronary heart disease, but irrespective of outcome, the findings included beneficial effects,9,10 no effect,11,12 and detrimental effects13 in a few cases.

A body of literature, albeit limited, exists about the health effects of religious practices among Muslims, and these include the listening, reciting, or repeating (zikr) the text of the Quran, the holy book for the Muslims.14–17Two experimental studies showed that listening to Quran recitation (15 and 18 min, respectively) increased the mental health score among nursing students and reduced anxiety in cardiac patients.14,15 In a cross-sectional study, geriatric-home residents who reported Quran recitation had significantly better mental health than those who did not recite.16 The single experimental study that evaluated the health effects of zikr in patients awaiting surgery reported a subjective reduction of anxiety and pain but no difference in objective measures such as blood pressure or heart rate.17

An important religious practice for Muslims is the memorization of Quran. The text of Quran—6,236 verses, arranged in 30 sections—forms the basis of daily prayer to and remembrance of God for Muslims. In addition, Muslims believe that Quran memorization, as an act of worship, will be rewarded in the hereafter. Therefore, they try to memorize as much of the text as possible—to the extent that many people, even when their mother tongue is not Arabic, memorize the entire book.

There is hardly any data on the health effects of Quran memorization despite the importance of it in the Islamic faith. In a Kuwaiti study, Quran memorization was part of a 15-item religious commitment scale, and the results showed a lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure among those with higher commitment.18 It was, however, not clear, as per the analysis adopted, whether the benefit reported was attributable to the memorization itself.

Saudi Arabia is an ideal place to study the health effects of Quran memorization since the Saudis speak Arabic, the original language of the Quran. Learning to read and memorize the Quran is included in the public educational curriculum at all levels; also, specialized schools are available to train students on memorization specifically. Furthermore, the prevalence of chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, among adults is notably high.19,20

In this cross-sectional study from Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia, participants were asked about the extent of their Quran memorization. They were also assessed for hypertension, diabetes, and depression. The hypothesis was that participants who had memorized a larger portion of the Quran would be less likely to have hypertension, diabetes, or depression compared to those participants who had memorized a smaller portion.

Methods

Sample

This study used a cross-sectional design and enrolled 400 men from the city of Buraidah, Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia. The inclusion criteria were (a) aged at least 55 or older, (b) Saudi citizenship, and (c) resident of Buraidah. According to governmental statistics, the total male population of Al-Qassim region of Saudi Arabia in 2016 was 501,831, of which 9.5% or approximately 50,000 were aged 55 years and older.21 Previous data estimate the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension to be 35% and 33%, respectively, among adult males in Al-Qassim.21 The required sample size for this study was 381 men (95% confidence level and with a 5% margin of error).22 In order to ensure that we had adequate power during the statistical analysis, we increased our sample by 5%. This was to compensate for any missing data related to the collection of blood samples or refusal to give a blood sample. The research ethics committee in the College of Medicine at Sulaiman Al-Rajhi Colleges approved this study in 2015 and the data were collected between December 2015 and February 2016.

Sampling strategy

A multi-stage semi-random sampling technique was used to obtain the sample. A detailed area map of Buraidah city was used to list the neighborhoods (total 96 neighborhoods), and 20 were selected randomly from it. All mosques in the selected neighborhoods were mapped and listed. The recruitment goal was three eligible persons per mosque. Therefore, 133 mosques were needed to obtain the desired sample of 400. However, 20% extra mosques were selected (total 160) in order to ensure that the study had the desired sample.

Research assistants described the study objectives and procedures to the prayer attendees and invited the eligible participants to join. Those who showed interest were given the informed consent form, which they read and signed to be enrolled into the study.

Assessment

The assessment took place in a quiet corner of each mosque after prayer. Participants were interviewed with standardized questionnaires to obtain information on demography, lifestyle, and depression. After the interview, they were assessed for physical measurements (i.e. height, weight, and blood pressure) and blood glucose while maintaining standard protocols. Two blood pressure readings were taken with a digital sphygmomanometer and the lowest value was recorded. Random blood glucose was measured with a glucometer (Accu-Chek Active).23

Exposure

Participants were asked how much of the Quran they had memorized. They were categorized as follows: less than 0.5, 0.5–1, 2–4, 5–9, and 10–30 sections.

Outcome

Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of ≥140 or diastolic ≥90 mm Hg or use of anti-hypertensive medication. Diabetes was defined as blood glucose ≥200 mg/dL or use of anti-diabetic medication. Depression was defined as a summary score of 2 or greater in the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2).24

Covariates

Covariates included age (<60, 60–69, and ≥70 years), body mass index (BMI; <25, 25–29.9, and ≥30), employment (yes and no), daily walking (yes and no), eating at restaurants (mostly at home and both home and restaurant), cigarette smoking (never, former, and current), and economic status (poor to lower middle class and upper middle class to rich). The covariates were selected based on the evidence shown in the scientific literature that the covariate was related to chronic diseases (e.g. diabetes and hypertension) and was considered to be a risk factor.25–27

Analysis

Data analysis was carried out with SPSS (version 22); all tests were two-sided with an alpha level of 0.05. Analysis began with the generation of descriptive statistics of variables. Mean and standard deviation for continuous and frequency for categorical variables were reported. Covariates (i.e. age, BMI, employment status, restaurant eating, daily walking, exercise, and economic status) were compared across the categories of Quran memorization; linear contrast in the general linear model (analysis of variance (ANOVA)) and Cochran–Armitage trend test were used for the comparison of continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Logistic regression was employed to model outcomes (i.e. hypertension, diabetes, and depression). First, the models were run with only Quran memorization variable (unadjusted analysis); the odds ratios and the associated 95% confidence interval for each of the comparison categories were estimated. Afterwards, the models were run without specifying that Quran memorization was a categorical variable in order to obtain p value for trend for each outcome. These two-step processes were replicated after including the covariates in the models (adjusted analysis). Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to check for model adequacy.

Results

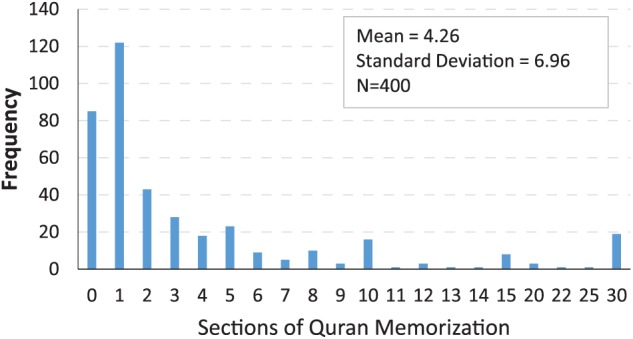

The participants’ mean age was 63 years (standard deviation = 7.5 years) and mean BMI was 28.9 kg/m2 (standard deviation = 4.8). Most of them were overweight or obese (78%). Almost all of them were married, and 35% were employed. A large majority of them (76%) reported to be non-smokers and were consuming mostly home-cooked food (65%). A little over half of them (54%) reported daily walking. Most of them reported that they belonged to the middle class, and a minority categorized themselves as poor (9%) or rich (6%; Table 1). Prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and depression were 71%, 29%, and 22%, respectively. The participants reported memorization of an average of 4.3 sections of Quran (standard deviation = 6.9). The distribution of memorization by sections was 21.0% (less than 0.5 sections), 30.5% (0.5–1 sections), 22.5% (2–4 sections), 12.5% (5–9 sections), and 13.5% (10–30 sections; Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of a sample of older adults (age ≥ 55 years; n = 400) in Al-Qassim Saudi Arabia.

| Variable | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| <60 | 160 | 40.0 |

| 60–69 | 158 | 39.5 |

| ≥70 | 82 | 20.5 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| <25 | 89 | 22.3 |

| 25–29.9 | 174 | 43.5 |

| ≥30 | 137 | 34.3 |

| Currently married | ||

| Yes | 392 | 98.0 |

| Employed | ||

| Yes | 140 | 35.0 |

| Walk daily | ||

| Yes | 218 | 54.5 |

| Eating habit | ||

| Mostly home-cooked food | 260 | 65.0 |

| Both home and restaurant | 140 | 35.0 |

| Cigarette smoking | ||

| Never smoker | 306 | 76.5 |

| Past smoker | 57 | 14.2 |

| Current smoker | 37 | 9.3 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Poor/lower middle class | 211 | 52.8 |

| Rich/upper middle class | 189 | 47.2 |

Figure 1.

Distribution of Quran minimization.

The mean age and BMI varied across the categories of Quran memorization; the variation, however, was non-directional (increase or decrease across the categories) and statistically non-significant. Similarly, no significant variation by employment and eating out at restaurants was observed although employment frequency was least among those who reported <0.5 section of memorization (Table 2). There was a monotonic decrease of smoking (current as well as former) frequency across Quran memorization, with the highest frequency observed among those with <0.5 section and the lowest among those with between 10 and 30 sections of memorization (p < 0.0001). The frequency of daily walking (p = 0.06) and higher economic status (self-reported upper middle class or rich, p = 0.01) increased across the memorization categories, except for highest (i.e. 10–30 sections; Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of characteristics across categories of Quran memorization in a sample of older men (age ≥ 55 years; n = 400) from Al-Qassim Saudi Arabia.

| Variable | Sections of Quran memorization |

Trend p value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.5 (n = 85) | 0.5–1 (n = 122) | 2–4 (n = 89) | 5–9 (n = 50) | 10–30 (n = 54) | ||

| Age (years) | 63.1 ± 7.7 | 62.0 ± 6.0 | 64.1 ± 8.8 | 62.8 ± 7.1 | 62.6 ± 7.2 | 0.90 |

| Body mass index | 29.1 ± 4.6 | 28.8 ± 5.1 | 28.1 ± 4.7 | 29.2 ± 4.8 | 28.8 ± 4.4 | 0.89 |

| Employed (%) | 25.9 | 37.7 | 39.3 | 30.0 | 40.7 | 0.20 |

| Eating at restaurant (%) | 36.5 | 35.2 | 29.2 | 40.0 | 37.0 | 0.88 |

| Smoking (%) | <0.0001 | |||||

| Current | 22.4 | 10.7 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 1.9 | |

| Past | 23.5 | 13.1 | 16.9 | 4.0 | 7.4 | |

| Daily walk (%) | 44.7 | 54.9 | 57.3 | 70.0 | 50.0 | 0.14 |

| Economic status (%) Upper middle class/rich |

35.3 | 41.8 | 57.3 | 58.0 | 51.9 | 0.004 |

In the unadjusted models, Quran memorization was significantly associated with all three outcomes; specifically, the likelihood of hypertension, diabetes, and depression decreased across the increased categories of memorization (p trend values < 0.0001). These dose–response relationships between memorization and outcomes attenuated to some extent but still were significant after the models were adjusted for the covariates (p trend: hypertension = 0.001, diabetes = 0.003, and depression < 0.0001). In the unadjusted models, the odds ratios for the top three memorization categories (2–4, 5–9, and ≥10 sections) were significant for diabetes and depression, and only the highest category (≥10) was significant for hypertension. After adjustment for covariates, the statistical significance of some of these estimates was lost, except for the highest category. For example, the likelihood of hypertension, diabetes, or depression were, respectively, 64%, 71%, and 81% less likely for those who memorized at least 10 sections of Quran compared to those with <0.5 section memorization (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted associations of Quran memorization with hypertension, diabetes, and depression in a sample of older men (age ≥ 55 years; n = 400) from Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia.

| Quran memorization | N | Outcomes |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension (prevalence = 71%) |

Diabetes (prevalence = 29%) |

Depression (prevalence = 21.8%) |

||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Unadjusted model | ||||

| <0.5 | 85 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 0.5–1 | 122 | 1.06 (0.54, 2.08) | 0.73 (0.41, 1.30) | 1.21 (0.67, 2.21) |

| 2–4 | 89 | 0.69 (0.35, 1.38) | 0.52 (0.27, 0.99) | 0.44 (0.21, 0.94) |

| 5–9 | 50 | 0.51 (0.24, 1.11) | 0.42 (0.19, 0.94) | 0.20 (0.07, 0.64) |

| 10–30 | 54 | 0.28 (0.14, 0.60) | 0.26 (0.11, 0.62) | 0.14 (0.04, 0.50) |

| p trend < 0.0001 | p trend < 0.0001 | p trend < 0.0001 | ||

| Adjusted modela | ||||

| <0.5 | 85 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 0.5–1 | 122 | 1.19 (0.58, 2.41) | 0.75 (0.40, 1.40) | 1.51 (0.77, 2.95) |

| 2–4 | 89 | 0.84 (0.40, 1.75) | 0.49 (0.24, 0.99) | 0.60 (0.27, 1.36) |

| 5–9 | 50 | 0.57 (0.25, 1.30) | 0.45 (0.19, 1.08) | 0.34 (0.10, 1.10) |

| 10–30 | 54 | 0.36 (0.16, 0.78) | 0.29 (0.11, 0.73) | 0.19 (0.05, 0.72) |

| p trend = 0.001 | p trend = 0.003 | p trend < 0.0001 | ||

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Models were adjusted for age, body mass index, employment status, eating habit, daily walking, smoking, and economic status.

Discussion

In this study, a linear trend was observed between the quantity of Quran memorization and disease outcomes, that is, the likelihood of participants having hypertension, diabetes, and depression decreased across the increased categories of memorization. In particular, the benefit was strong and significant for participants who memorized at least 10 sections of Quran. Importantly, these effects were independent as the models were adjusted for established risk factors of the selected disease outcomes such as age, BMI, smoking, exercise habit, and self-perceived health.25–27

The results of this study on Quran memorization are not easily comparable to other studies that addressed religious practices and health. First, the definition of the religious practices varies among the studies.2–5 More importantly, religious practices may have different meanings across faiths. Finally, the comparison is constrained by the limited availability of data; for example, no studies have been published with diabetes as an outcome, and only one study was available on depression.28 In that study, among patients with disparate diseases, those who reported moderate/high religious struggle exhibited higher levels of depression.28 There were multiple studies on hypertension or blood pressure as an outcome.7,13,18,29 While there were several studies that reported that religious practices were associated with lower blood pressure,7,18 there were others that found that religious practices were related to increased blood pressure.13

There is little explanation available, in the absence of data, as to why Quran memorization would be protective of diseases. Quran memorization might be viewed as a testimony of faith by the Muslims, and the higher the memorization, the greater the psychological boost it produces to their belief, which includes a sense of happiness, contentment, and positive attitude. Also, memorization of the Quran leads the believer to recite it in order to retain it, and the frequency of recitation is likely higher for those who memorize a large portion of it. This recitation may yield a similar type of health benefit that prayer or chanting does to the people of other faiths. Recitation of Quran also means a continuous reminder to Muslims of things that they should avoid. For example, they are to refrain from consuming substances that are injurious to their body and mind, which may explain a very low prevalence of smoking among those with a higher quantity of memorization.

We had limited sampling options, and we chose the one that had the potential to draw a representative sample. We were not aware of the existence of any local database (e.g. city council or local governorate) from which we could draw a random sample. However, the social norms make it less acceptable to conduct home visits by unknown persons (e.g. research assistants), thereby eliminating the possibility of obtaining the sample through random selection of houses. That left the option of a convenient sample, for example, selecting participants from market places or malls. We felt that a mosque-based sample was a good compromise between these two sampling techniques. We employed randomness in the selection of neighborhoods and mosques. At the same time, it is customary among the Saudis to go to mosque for daily prayers, and the rate of attendance is very high among older adult males. Therefore, mosques provided a suitable gathering place for all who could be theoretically eligible for this study. It should, however, be noted that we missed those who were ill at the time of the study or who could not attend prayer because of their physical disability.

The quantity of Quran memorization should be interpreted as a strong correlate of hypertension, diabetes, and depression, but no causality can be inferred for any of the outcomes as the cross-sectional design of this study did not allow the ascertainment of temporality between the timing of Quran memorization and the development of these outcomes. That being said, in the large majority of cases, Muslims memorize Quran at an early age, either in childhood or in adolescence, and memorization in adulthood is a rarity. Therefore, it is likely that the memorization happened long before the development of these adult-onset diseases. Another related issue is the precision of information about Quran memorization that the participants provided. We do not know of any study that assessed how accurately Muslims self-report information in this regard, but Muslims who memorize either a portion of or the whole Quran are likely to know how the sections are structured. Additionally, the participants were not aware of the study’s hypothesis, and therefore, did not have any incentive to misreport this information.

The study outcomes were assessed either with an objective measure (e.g. hypertension or diabetes) or with a validated questionnaire (e.g. depression). However, the disease estimates were likely affected by the study’s assessment protocol. We may have slightly underestimated the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension. We used random blood glucose and self-reported use of medicine as the definition for diabetes, but we did not include any secondary tests (e.g. fasting blood glucose or HbA1c) nor did we consider symptoms of hyperglycemia. The blood pressure data were taken from the lower of the two readings as opposed to the average, which may have lowered our estimates of hypertension. As for depression, the PHQ is a screening and not a clinical tool for diagnosis.30 Moreover, we chose to apply the lower cut-off value (2 instead of 3, both are recommended) for depression diagnosis, as there were only a few participants with depression at the higher value, and therefore, it was not suitable for analysis. The lower cut-off value increased the sensitivity and decreased the specificity, diagnosing some participants as depressed when in reality they were not.

Conclusion

There was a strong linear association between Quran memorization and hypertension, diabetes, and depression (after adjusting models for established risk factors) indicating that those who had memorized a larger portion of the Quran were less likely to have one of these chronic diseases. This finding suggests that the potential health benefits of Quran memorization and the underlying mechanisms should be researched. Future studies should note the limitations of this study and improve on the design and the measurement, for example, using a more representative sample by including females and younger adults and obtaining data from a wider geographical area.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Erin Strotheide for her editorial contributions to this manuscript. N.S. had the original idea. The student author/research assistants at Sulaiman Al-Rajhi Colleges (A. Alhadlag, M.A., B.A., M.A., Z.A., O.A., and M. Aljaser) completed the field data collection and created the database for analysis. N.S. and J.S. completed the analysis. All authors contributed to manuscript preparation and approved its full version.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the research unit at Sulaiman Al-Rajhi Colleges through its annual allocation for the promotion of student research; the college was not involved in the study design or implementation.

Ethical approval: The research ethics committee in the College of Medicine at Sulaiman Al-Rajhi Colleges approved this study in 2015 and the data were collected between December 2015 and February 2016.

Informed consent: Research assistants described the study objectives and procedures to the prayer attendees and invited the eligible participants to join. Those who showed interest were given the informed consent form, which they read and signed to be enrolled in the study.

References

- 1. Stewart WC, Adams MP, Stewart JA, et al. Review of clinical medicine and religious practice. J Relig Health 2013; 52(1): 91–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stewart WC, Sharpe ED, Kristoffersen CJ, et al. Association of strength of religious adherence with attitudes regarding glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Ophthalmic Res 2011; 45(1): 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keefe FJ, Affleck G, Lefebvre J, et al. Living with rheumatoid arthritis: the role of daily spirituality and daily religious and spiritual coping. J Pain 2001; 2(2): 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vannemreddy P, Bryan K, Nanda A. Influence of prayer and prayer habits on outcome in patients with severe head injury. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2009; 26(4): 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cha KY, Wirth DP, Lobo RA. Does prayer influence the success of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer? Report of a masked, randomized trial. J Reprod Med 2001; 46(9): 781–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leibovici L. Effects of remote, retroactive intercessory prayer on outcomes in patients with bloodstream infection: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2001; 323(7327): 1450–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koenig HG, George LK, Hays JC, et al. The relationship between religious activities and blood pressure in older adults. Int J Psychiatry Med 1998; 28(2): 189–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, George LK, et al. Attendance at religious services, interleukin-6, and other biological parameters of immune function in older adults. Int J Psychiatry Med 1997; 27(3): 233–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schnall E, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Swencionis C, et al. The relationship between religion and cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in the women’s health initiative observational study. Psychol Health 2010; 25(2): 249–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thompson E, Berry D, Nasir L. Weight management in African-Americans using church-based community interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc 2009; 20(1): 59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Ironson G, et al. Spirituality, religion, and clinical outcomes in patients recovering from an acute myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med 2007; 69(6): 501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feinstein M, Liu K, Ning H, et al. Burden of cardiovascular risk factors, subclinical atherosclerosis, and incident cardiovascular events across dimensions of religiosity: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation 2010; 121(5): 659–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buck AC, Williams DR, Musick MA, et al. An examination of the relationship between multiple dimensions of religiosity, blood pressure, and hypertension. Soc Sci Med 2009; 68(2): 314–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kazemi M, Ansari A, Tavakoli M, et al. The effect of the recitation of holy Quran on mental health in nursing students of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci Health Serv 2003; 3(1): 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Babaii A, Abbasinia M, Hejazi S, et al. The effect of listening to the voice of Quran on anxiety before cardiac catheterization: a randomized controlled trial. Health Spiritual Med Ethics 2015; 2(2): 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sharifi ZS, Tagharobi Z. Role of Quran recitation in mental health of the elderly. Q Quran Med 2011; 1(1): 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soliman H, Mohamed S. Effects of Zikr meditation and jaw relaxation on postoperative pain, anxiety and physiologic response of patients undergoing abdominal surgery. J Biol Agric Healthc 2013; 3(2): 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Al- Kandari YY. Religiosity and its relation to blood pressure among selected Kuwaitis. J Biosoc Sci 2003; 35(3): 463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. El Bcheraoui C, Memish ZA, Tuffaha M, et al. Hypertension and its associated risk factors in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013: a national survey. Int J Hypertens 2014; 2014: 564679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. El Bcheraoui C, Basulaiman M, Tuffaha M, et al. Status of the diabetes epidemic in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,2013. Int J Public Health 2014; 59(6): 1011–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. General Authority for Statistics. Demography survey. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2016, https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/en-demographic-research-2016_2.pdf

- 22. Creative Research Systems (US). Sample size calculator. Sebastopol, CA, https://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm (accessed 1 October 2017).

- 23. Freckmann G, Baumstark A, Jendrike N, et al. System accuracy evaluation of 27 blood glucose monitoring systems according to DIN EN ISO 15197. Diabetes Technol Ther 2010; 12(3): 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003; 41(11): 1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Al Hayek AA, Robert AA, Al Saeed A, et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among Saudi patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional survey. Diabetes Metab J 2014; 38(3): 220–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saquib N, Khanam MA, Saquib J, et al. High prevalence of type 2 diabetes among the urban middle class in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Babyak M, Blumenthal JA, Herman S, et al. Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosom Med 2000; 62(5): 633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fitchett G, Murphy PE, Kim J, et al. Religious struggle: prevalence, correlates and mental health risks in diabetic, congestive heart failure, and oncology patients. Int J Psychiatry Med 2004; 34(2): 179–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fitchett G, Powell LH. Daily spiritual experiences, systolic blood pressure, and hypertension among midlife women in SWAN. Ann Behav Med 2009; 37(3): 257–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16(9): 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]