Abstract

Background:

There is controversy regarding the relationship between gender and acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Objective:

To study the impact of gender on presentation, management, and mortality among patients with ACS in the Middle East.

Methodology:

From January 2012 to January 2013, 4057 patients with ACS were enrolled from four Arabian Gulf countries (Kuwait, Oman, United Arab Emirates, and Qatar), representing more than 85% of the general hospitals in each of the participating countries.

Results:

Compared to men, women were older and had more comorbidities. They also had atypical presentation of ACS such as atypical chest pain and heart failure. The prevalence of non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (49 vs. 46%; P < 0.001) and unstable angina (34 vs. 24%; P < 0.001) was higher among women as compared to men. In addition, women were less likely to receive evidence-based medications such as aspirin, clopidogrel, beta-blocker, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on admission and on discharge. During hospital stay, women suffered more heart failure (15 vs. 12%; P = 0.008) and were more likely to receive blood transfusion (6 vs. 3%; P < 0.001). Women had higher 1-year mortality (14 vs. 11%; P < 0.001), the apparent difference that disappeared after adjusting for age and other comorbidities.

Conclusion:

Although there were differences between men and women in presentation, management, and in-hospital outcomes, gender was shown to be a nonsignificant contributor to mortality after adjusting for confounders.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome, Arabian Gulf, gender, Middle East, registries

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of mortality and morbidity globally in both men and women.[1] Studies indicate a gender difference in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) presentation, diagnosis, management, and outcomes. Some data suggest that women have higher mortality rates than men, while other studies have failed to show gender as a contributory factor in the presentation and mortality in ACS patients.[2,3,4]

There are few papers that describe the relationship between ACS and gender among Middle Eastern patients.[5,6] This paper aims to report on the influence of gender on ACS presentation, diagnosis, management, and outcomes in the Middle Eastern patients.

METHODOLOGY

Registry design

Data were collected from Gulf locals with ACS events (Gulf COAST) registry. The registry design and methodology has previously been published.[5] This was a prospective, multinational, longitudinal, observational, cohort-based registry of all consecutive local patients (citizens) who were admitted to 29 general hospitals in four Gulf countries including two hospitals in Bahrain, six hospitals in Kuwait, 12 hospitals in Oman, and nine hospitals in the United Arab Emirates. All hospitals had on-site thrombolytic therapy and nine had on-site cardiac catheterization facility available. Patients were recruited from January 2012 to January 2013. The ethics committees of each participating institution approved the study protocol.

Study population

Patients enrolled in the registry were citizens ≥18 years of age diagnosed with ACS according to the American College of Cardiology (ACC) data standards[7] including ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-STEMI (NSTEMI), left bundle branch block (LBBB) myocardial infarction, or unstable angina (UA). A written informed consent was obtained to participate in the study. Only citizens were included who provide better follow-up information and have homogenous characteristics in terms of lifestyle, standard of living, and access to free universal health care.

Data collection and validation

Data were collected on a standardized report form (CRF) with variables that were congruent with ACC key data elements and definitions.[7] Data collected included patient demographics, previous medical history, risk factors, prior medications, clinical presentation, management during hospital stay (including medications, reperfusion therapy, and procedures), and discharge medications. Patients were followed up at 1 month, 6 months, and 12 months interval. Follow-ups were carried out by phone call or clinic visit. Data gathered in this study were entered into an online system at www.gulfcoastregistry.org which had immediate display of automated data checks.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages were reported. Differences between groups were analyzed using the Pearson's Chi-square test. For continuous variables, mean and standard deviation were used to summarize the data while analysis was performed using Student's t-test. For continuous variables not normally distributed, they were summarized using the median and interquartile range and analyses were performed using Mann–Whitney test. The association between mortality and gender adjusting for various confounders (age, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension) was analyzed using multivariable logistic regression. An a priori two-tailed level of significance was set at P = 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 13.1 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

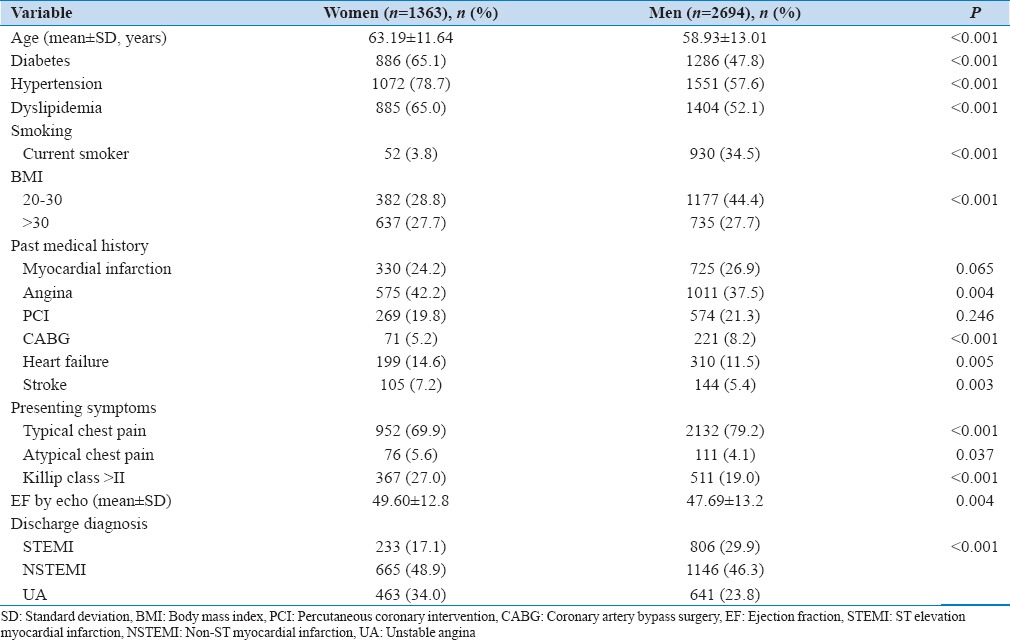

A total of 4057 patients were enrolled in this study, of whom 1363 (34%) were women. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1 stratified by gender. Compared to men, women were older (63 vs. 59 years; P < 0.001) and had significantly more comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus (65 vs. 48%: P <0.001), hypertension (79 vs. 58%: P <0.001), and dyslipidemia (65 vs. 52%: P <0.001). In addition, they were more likely to have a prior history of angina (42 vs. 37%; P = 0.004), heart failure (15 vs. 11%; P = 0.005), and stroke (7.2 vs. 5.4%; P = 0.003) but less likely to be associated with coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) (5.2 vs. 8.2%; P < 0.001). Women presented to hospitals were more commonly with atypical chest pain (5.6 vs. 4.1%; P = 0.037) and heart failure with Killip Class ≥ II (27% vs. 19%; P < 0.001). Furthermore, NSTEMI (49 vs. 46%) and UA (34 vs. 24%) were more prevalent among women (overall P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

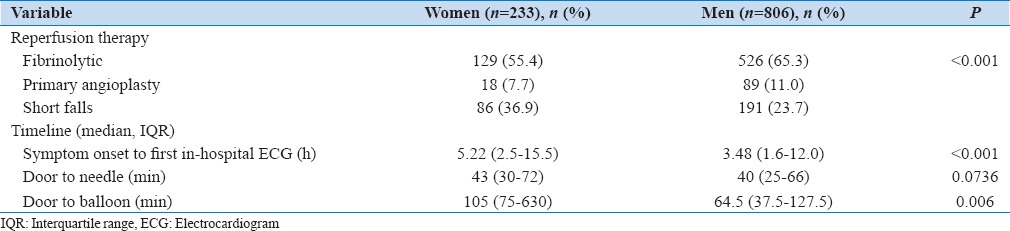

Table 2 shows reperfusion therapy of STEMI patients according to gender. Both genders with STEMI were more likely to receive fibrinolytic therapy, but compared to men, women were less likely to undergo primary angioplasty (7.7 vs. 11%; P < 0.001). Women had longer time from symptoms onset to first in-hospital ECG (5.2 vs. 3.48 h; P < 0.001) and door to balloon time (105 vs. 65 min; P = 0.006).

Table 2.

Reperfusion for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and left bundle branch block myocardial infarction patients

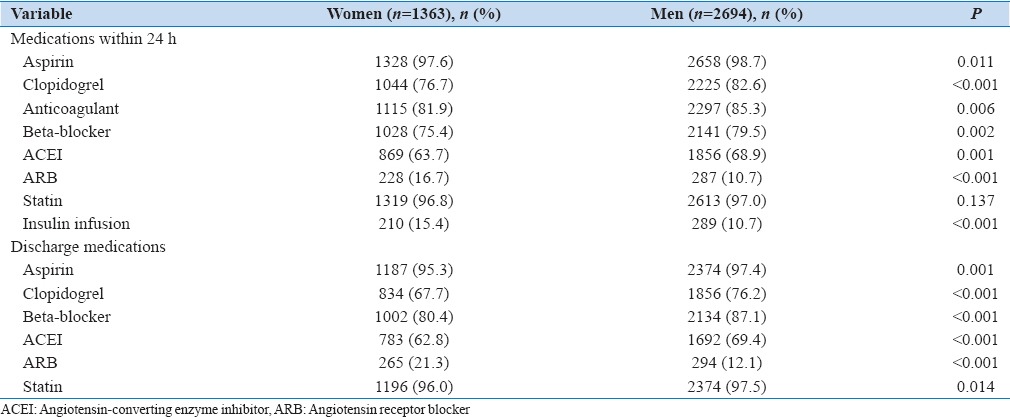

Women received less guideline-derived medications [Table 3] such as clopidogrel (77 vs. 83%; P < 0.001), beta-blocker (75% vs. 80%; P = 0.002), and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) (64 vs. 69%; P = 0.001), but they were more likely to receive angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (17 vs. 11%; P < 0.001) within the first 24 h of admission. During discharge, a similar pattern was observed where women were also less likely to receive aspirin (95 vs. 97%; P = 0.001), clopidogrel (68 vs. 76%; P < 0.001), beta-blockers (80 vs. 87%; P < 0.001), ACEI (63 vs. 69%; P < 0.001), and statins (96 vs. 98%; P = 0.014). However, they were more likely to receive ARBs at discharge (21 vs. 12%; P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Medications within 24 h and at discharge

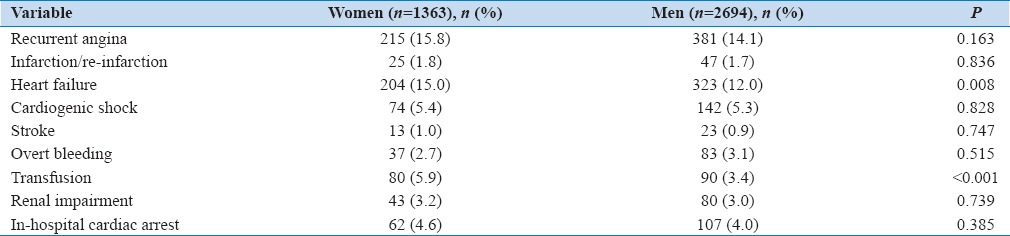

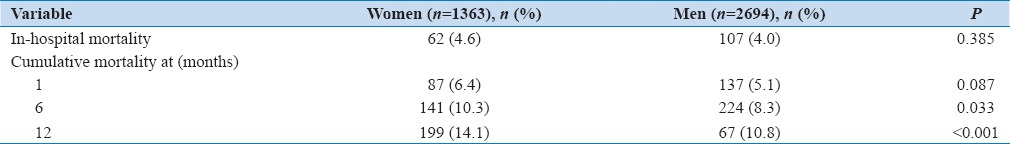

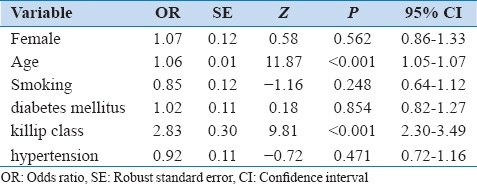

In-hospital outcomes according to gender are shown in Table 4. Compared to men, women suffered more heart failure (15 vs. 12%; P = 0.008) and were more likely to receive blood transfusion (5.9 vs. 3.4%; P < 0.001). Other complications did not show any significant differences based on gender. There was a significant difference in unadjusted cumulative overall mortality rate in women compared to men at 6 months (10.3% vs. 8.3%; P = 0.033) and at 12 months follow-up (14.1% vs. 10.8%; P < 0.001) [Table 5]. However, the overall difference in mortality became insignificant after adjusting for age and comorbidities such as smoking, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension (odds ratio, 1.07; 95% confidence interval: 0.86–1.33; P = 0.562) [Table 6].

Table 4.

In-hospital outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndrome according to gender

Table 5.

Mortality of patients with acute coronary syndrome according to gender

Table 6.

Adjusted mortality of patients with acute coronary syndrome at 1 year

DISCUSSION

This report on gender role in ACS in the Gulf region has shown consistent results with universal studies.[4,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] Women with ACS were older and had more comorbidities. They presented, more often than men, with atypical chest pain and took longer time to seek medical care. They also received less evidence-based medications and were less likely to undergo primary angioplasty. Despite the fact that women had higher apparent mortality, the gender difference was not shown to be a contributor to mortality at 1 year after adjusting for risk factors.

In recent scientific research, data have shown that men and women differ beyond gender.[16,17] Efforts from different organizations have been advocated to include more women in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to study the difference between genders. Over the years, there has been improvement in the percentage of women enrolled in RCTs, but still gender-specific analyses are not sufficiently performed. In our study, the female percentage was fairly the same as the global studies reaching almost 34% of the study population. There are many significant differences between men and women in terms of management, outcome, and mortality that need to be further studied to provide better diagnosis and treatment accordingly.[16,17]

In accordance with previous studies, women were older and had more comorbidities which might explain the poorer prognosis.[8,9,10,11] Furthermore, women had atypical presentation of ACS and took longer time to seek medical care, both of which might delay in receiving appropriate treatment.[3,10,12,13]

In-hospital management showed that women were less likely to undergo primary angioplasty. This is consistent with several previous studies[11,14] and can be explained by the fact that women are of older age and have more comorbidities, suggesting a higher risk for invasive intervention. In addition, women were less often prescribed evidence-based medications in the acute settings and on discharge such as aspirin, clopidogrel, beta-blockers, ACEIs, and statins.[4,15] The fact that women get less antiplatelet could be attributed to anemia and higher tendency to bleed. However, it remains uncertain why women get less beta-blockers, ACEI, and statins.

Studies have shown that women tend to develop worse outcomes, but the gender role in mortality has been controversial in many studies.[3,10,11] Women tend to have higher mortality at 1 year, but after adjusting for age and other risk factors, the difference in mortality between both genders has not been shown to be significant. However, in Gulf RACE-I study which was conducted in 2007 including six Middle Eastern countries, the mortality among women with ACS remained higher than men even after adjustment.[18]

Strengths and limitations of the study

Data in this paper represent more than 85% of the general hospitals in each of the four Gulf countries participating in the study. Only citizens were included for better representation of the Gulf area characteristics and better follow-ups. In addition, data collected in this study are prospective, allowing better observation of the results over 1-year follow-up. On the other hand, the possible limitations of this study could be the exclusion of expatriates as the study only included citizens. It is known that expatriates constitute a considerable proportion in the Middle East.

CONCLUSION

There is gender disparity in the presentation, comorbidity profile, and evidence-based medication management in ACS patients in the Middle East. However, despite the apparent mortality difference between the cohorts, these gender differences disappeared after adjustment of confounders in Middle Eastern ACS patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

The author Zubaid receives speaking honoraria from Sanofi and Boehringer Ingelheim and Astra Zeneca. Other authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs) [Last accessed on 2016 Jul 13]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/

- 2.Mosca L, Barrett-Connor E, Wenger NK. Sex/gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevention: What a difference a decade makes. Circulation. 2011;124:2145–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.968792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dey S, Flather MD, Devlin G, Brieger D, Gurfinkel EP, Steg PG, et al. Sex-related differences in the presentation, treatment and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes: The global registry of acute coronary events. Heart. 2009;95:20–6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.138537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steg P, Goldberg R, Gore J. Baseline characteristics, management practices, and in-hospital outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes in the global registry of acute coronary events (GRACE) ACC Curr J Rev. 2002;11:16–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02489-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zubaid M, Thani KB, Rashed W, Alsheikh-Ali A, Alrawahi N, Ridha M, et al. Design and rationale of gulf locals with acute coronary syndrome events (Gulf Coast) registry. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2014;8:88–93. doi: 10.2174/1874192401408010088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zubaid M, Rashed WA, Al-Khaja N, Almahmeed W, Al-Lawati J, Sulaiman K, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of acute coronary syndromes in the gulf registry of acute coronary events (Gulf RACE) Saudi Med J. 2008;29:251–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard BG, Wenger NK. Review of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: What is new and why? Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2016;10:4. doi: 10.1007/s12170-016-0496-3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elsaesser A, Hamm CW. Acute coronary syndrome: The risk of being female. Circulation. 2004;109:565–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116022.77781.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maas AH, Appelman YE. Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Neth Heart J. 2010;18:598–602. doi: 10.1007/s12471-010-0841-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sulaiman K, Panduranga P, Al-Zakwani I. Gender-related differences in the presentation, management, and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndrome from Oman. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2011;23:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jsha.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shehab A, Al-Dabbagh B, AlHabib KF, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Almahmeed W, Sulaiman K, et al. Gender disparities in the presentation, management and outcomes of acute coronary syndrome patients: Data from the 2nd gulf registry of acute coronary events (Gulf RACE-2) PLoS One. 2013;8:e55508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canto JG, Goldberg RJ, Hand MM, Bonow RO, Sopko G, Pepine CJ, et al. Symptom presentation of women with acute coronary syndromes: Myth vs. reality. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2405–13. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruins Slot MH, Rutten FH, van der Heijden GJ, Doevendans PA, Mast EG, Bredero AC, et al. Gender differences in pre-hospital time delay and symptom presentation in patients suspected of acute coronary syndrome in primary care. Fam Pract. 2012;29:332–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between women and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:221–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107253250401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bugiardini R, Estrada JL, Nikus K, Hall AS, Manfrini O. Gender bias in acute coronary syndromes. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2010;8:276–84. doi: 10.2174/157016110790887018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiebinger L, Leopold SS, Miller VM. Editorial policies for sex and gender analysis. Lancet. 2016;388:2841–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32392-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avery E, Clark J. Sex-related reporting in randomised controlled trials in medical journals. Lancet. 2016;388:2839–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Menyar A, Zubaid M, Rashed W, Almahmeed W, Al-Lawati J, Sulaiman K, et al. Comparison of men and women with acute coronary syndrome in six Middle Eastern countries. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1018–22. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]