Abstract

Objectives

The aim is to identify exposures associated with lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities by race and gender using an exposome database coupled to a graph theoretical toolchain.

Methods

Graph theoretical algorithms were employed to extract paracliques from correlation graphs using associations between 2162 environmental exposures and lung cancer mortality rates in 2067 counties, with clique doubling applied to compute an absolute threshold of significance. Factor analysis and multiple linear regressions then were used to analyze differences in exposures associated with lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities by race and gender.

Results

While cigarette consumption was highly correlated with rates of lung cancer mortality for both white men and women, previously unidentified novel exposures were more closely associated with lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities for blacks, particularly black women.

Conclusions

Exposures beyond smoking moderate lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities by race and gender.

Policy Implications

An exposome approach and database coupled with scalable combinatorial analytics provides a powerful new approach for analyzing relationships between multiple environmental exposures, pathways and health outcomes. An assessment of multiple exposures is needed to appropriately translate research findings into environmental public health practice and policy.

Keywords: Disparities, exposome, lung cancer, mortality, social determinants

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer mortality in both males and females in the United States.[1] Based on 2009–2013 SEER data, the National Cancer Institute projected that lung and bronchus cancer is associated with an estimated 158,080 deaths in the US., 415,787 individuals would be living with the disease, and 224,390 new cases would be diagnosed in 2016.[2] These figures translate to an overall, age adjusted incidence rate of 57.3/100,000, and a mortality rate of 46.0.[2] Despite a more than 50% decrease in smoking rates from 1970 to 2014 (37.4%–16.8%),[3] the number of deaths caused by lung cancer has more than doubled from 61,700 in 1970[4] to an estimated 159,260 in 2014.[5]

Mortality

While smoking has been identified as contributing to 87% of lung cancer deaths overall,[6] numerous other etiological factors have been identified. Radon has been attributed to approximately 10% of lung cancer mortality, accounting for an estimated 21,000 lung cancer deaths each year.[7] Exposure to secondhand smoke has been estimated to account for 4% of lung cancer deaths.[7] A 2002 American Cancer Society study found that long term exposure to combustion related particulate matter (PM2.5) led to an 8% increase in lung cancer mortality.[8] A recent systematic review of the effects of air pollution found the meta relative risk for lung cancer associated with PM2.5 was 1.09 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.04, 1.14) and the meta relative risk of lung cancer associated with PM10 was 1.08 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.17). In addition, meta relative risk estimates for adenocarcinoma associated with PM2.5 and PM10 were 1.40 (95% CI: 1.07, 1.83) and 1.29 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.63), respectively.[9] Similarly, occupational exposures (smelters, blast furnaces and foundries, rubber manufacturing, paving, roofing, painting, and chimney sweeping) and associated chemical exposures, including certain metals (chromium, cadmium and arsenic), volatile organic compounds, radiation and diesel exhaust together, have been associated with an additional 9% to 15% of lung cancer deaths. Individual etiological risk factors linked to lung cancer mortality when combined, exceed 100%.[10]

Disparities

Smoking rates do not adequately account for race×gender, lung cancer mortality disparities. Age adjusted, adult smoking rates (2015)[11] and age adjusted, lung cancer mortality rates (2009–2013)[12] were 17.2% and 57.7 for white males (WM); 16.0% and 38.39 for white females (WF); 20.9% and 70.6 for black males (BM); and 13.3% and 35.3 for black females (BF). Similarly, males and females who smoke were 23 and 13 times more likely to develop lung cancer, respectively, compared to those who never smoked.[13] Poor and medically underserved populations are more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancers than compared to those treated more effectively or cured if diagnosed earlier.[14]

Social determinants of lung cancer mortality disparities also have been associated with increased risk for lung cancer mortality, including a broad range of indicators such as behavioral factors (e.g., smoking, higher rates of alcohol use, and obesity), socioeconomic status, education, occupation, living conditions, lack of health care coverage, mistrust of the health care system, and fatalistic attitudes about cancer. Financial barriers, cultural beliefs, and lack of access to culturally competent health care by low income and/or racial/ethnic minority groups also have been associated with lung cancer mortality disparities. Aizer et al.[15] found that differences in lung cancer mortality rates between Blacks and Whites persist even after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, year and stage of diagnosis, and receipt of definitive treatment. It is unclear, however, whether the mechanisms and pathways through which social determinants affect lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities are etiological, mediating, or simply co occurring.

Multiple exposures

While cigarette consumption clearly accounts for the greatest attributable risk, it remains unclear the extent to which other environmental exposures contribute independently, interactively, or synergistically. Persons who are exposed to radon, PM2.5, workplace chemicals, pesticides, or chemicals in the home and who smoke are at greater risk for dying from lung cancer than those who smoke but who do not experience similar exposures. Living with a smoker likewise increases a nonsmoker’s chances of developing lung cancer by 20%–30%,[13] accounting for approximately 3,000 excess lung cancer deaths each year.[16] Similarly, lung cancer risk associated with PM2.5 is greatest for former smokers (1.44 [95% CI: 1.04, 2.01]) as compared to never smokers (1.18 [95% CI: 1.00, 1.39]). Deaths attributed to radon exposure also are more likely to occur among smokers than nonsmokers.[7] While persons exposed to asbestos are five times more likely to develop lung cancer than those not exposed to asbestos, the risk for lung cancer mortality increases 50 fold for those who are exposed to asbestos and who smoke.[17] Till date, a few studies have attempted to examine the effects of multiple chemical and nonchemical stressors on lung cancer mortality or mortality disparities, by race and gender. The evidence clearly supports the need for applying a risk model that is capable of examining how multiple exposures across various domains act as etiologic, mediating, or co occurring factors to affect lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities.[18]

Exposome

The exposome has been previously defined by Wild[19] as cumulative exposures across the lifespan, from conception to death. Juarez et al.[19] demonstrated the general utility of the exposome approach using a graph theoretical toolchain to assess the effects of over 600 measures of environmental exposures on preterm births. That study examined relationships between annual, county level variables across three domains, and preterm births using graph theoretical algorithms and scalable combinatorial analyses. By contrast, this study more than triples the number of environmental stressors included in the analysis, particularly measures previously linked to lung cancer mortality. The goal of this research was to use an exposome database comprised 2162 chemical and nonchemical environmental stressors coupled with a graph theoretical toolchain and a data driven approach to identify putative relationships between exposures from natural, built, and social environment domains and lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities across four race and gender groups: WM, WF, BM, and BF.

METHODS

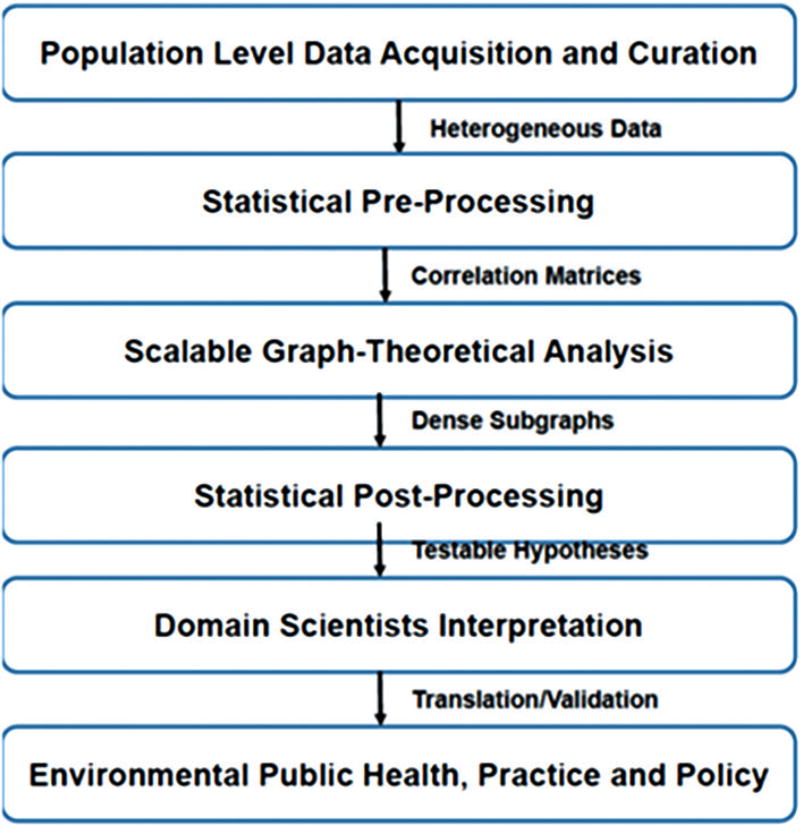

We integrated a portfolio of advanced computational tools and more conventional biostatistics, to elucidate latent relationships between annual county level measures of environmental stressors across the natural, built, and social environment domains with lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities rates, by race and gender. The overall approach we employed is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Graph theoretical toolchain. These steps were undertaken to assess exposure impact of multiple chemical and non-chemical environmental exposures on lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities using a public health exposome approach. Date from diverse sources were collected, curated and prepared for further interrogation. Modern combinatorial tools were used to distill highly correlated subgraphs for more traditional statistical analysis. These results can be used by domain scientists within community settings to generate and test hypotheses and to translate findings into public and environmental health policy and practice. The first four operations performed in this paper were used to demonstrate the proof of concept of the public health exposome approach while the latter two were designed to motive action

All exposure and health data were obtained from publically available sources and standardized as annual, county level, age adjusted rates per 100,000/population. Data were geo coded using ArcGIS 10.5 and analyzed by county. Due to small numbers of annual lung cancer deaths by race and gender, particularly in rural, homogeneous, and sparsely populated counties, data were pooled across multiple years (1999–2013) to derive an average, age adjusted, annualized, county rate per 100,000, by race, gender, and age (combined 45–84 years of age). Only counties with a minimum, combined total of ten mortality cases of the lung and bronchus (ICD 10 Codes: C33 (Malignant neoplasm of trachea), C34.0 (Main bronchus Malignant neoplasms), C34.1 (Upper lobe, bronchus or lung Malignant neoplasms), C34.2 (Middle lobe, bronchus or lung Malignant neoplasms), C34.3 (Lower lobe, bronchus or lung Malignant neoplasms), C34.8 (Overlapping lesion of bronchus and lung Malignant neoplasms), and C34.9 (Bronchus or lung, unspecified Malignant neoplasms) for each of the four, race×gender groups were included in the study. Racial differences were limited to blacks and whites based on the small number of counties that had a minimum of ten lung cancer deaths for other racial groups and exceeded the CDC Wonder suppression policy.

A total of 2,101 measures of diverse stressors from the three described environment domains for 2,067 (of 3,144) counties and county equivalents were used in this study. Examples of measures of the natural environment included meteorological conditions, chemical emissions, and land cover/use; measures of the built environment included health care access, neighborhood resources, and occupational codes; social environmental stressors included population level measures of social, demographic, economic, and political variables. See Table 1 in supplemental material for a complete list, source, and year of exposure variables. Mortality rates due to cancer of the lung and bronchus by county for WM, WF, BM, and BF were obtained from the CDC Wonder website https://wonder.cdc.gov/. Pooling, selection of counties, and smoothing were used in response to the CDC policy of suppressing data for counties in which there were fewer than ten reported cases. For counties in which persons of all four race×gender groups were counted, but no lung cancer deaths were reported, rates were smoothed with techniques designed for this purpose.[20] Suppressed mortality values were otherwise set to missing. All exposure and health data were obtained from publically available sources and standardized as annual, county level, age adjusted rates per 100,000/population. As there is a known lag of 20–30 years between environmental exposures and lung cancer mortality, we limited exposure data to the years 1980–2010. No Institutional Review Board approval was required as mortality rates and environmental stressors measurements were publically available secondary data.

Scalable computational analysis

We applied graph theoretical algorithms to the data. Pearson correlation coefficients were first calculated between each pair of variables (environmental exposure and lung cancer mortality rate). The clique doubling technique[21] was employed to compute an (absolute) threshold of significance, which was |r|>0.14. By applying this threshold and by anchoring on each of the four race×gender lung cancer mortality responses, we created four graphs (WM, WF, BM, and BF) for further analysis as described by Langston et al.[22] Vertex and edge counts were as follows. WM: 530, 80249; WF: 477, 65149; BM: 483, 66915; and BF: 486, 61167. Paracliques[23] were extracted from these graphs using a glom term[24] set to 1 and an anchor variable that was guaranteed to reside in the first and largest paraclique. Other paracliques also were considered, because those represented latent, putative relationships with the potential to be equally revealing. To reduce redundancy and extract underlying traits that bear the highest amount of data variability, we conducted a factor analysis procedure with varimax rotation using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) on the pool of variables from the first paraclique. Factor scores were calculated using the original variables so that we could make direct comparisons of factors within and between regression models; this resulted in 172 factors. A subset of 120 factors was selected by stepwise regression (due to computational limitations) and used in all possible regression analyses for each of the four, race×gender, lung cancer mortality variables, and differences between variables. A P = 0.0001 was the threshold used to determine statistical significance. Using parsimony, R square, and Akaike information criterion (AIC), we identified the highest contributing factors for each of the four race×gender groups.

The 20 most commonly occurring factors for each regression model were then analyzed in final multiple regression models, allowing factors to be compared for differential effects on race×gender, lung cancer mortality, and lung cancer mortality disparity rates. These effects then were computed by differences among the single rates. Standardized regression coefficients (β) were used to compare the relative importance of factors explaining variability of the eight, dependent variables of the models of lung cancer mortality rates and disparities.[25] Final regression models incorporated spatial autocorrelation based on location of county centers (Moran’s I = 0.0838, P < 0.001). We set absolute values of coefficient values above 0.5 to characterize strong factor contributions, between 0.3 and 0.5 for moderate contributions and below 0.3 for weak ones. Geographical information systems (GIS) were used to generate maps to visualize spatial distributions of each of the factors and assist with data interpretation (see Appendix 1: Maps, supplemental materials).

RESULTS

Lung cancer mortality

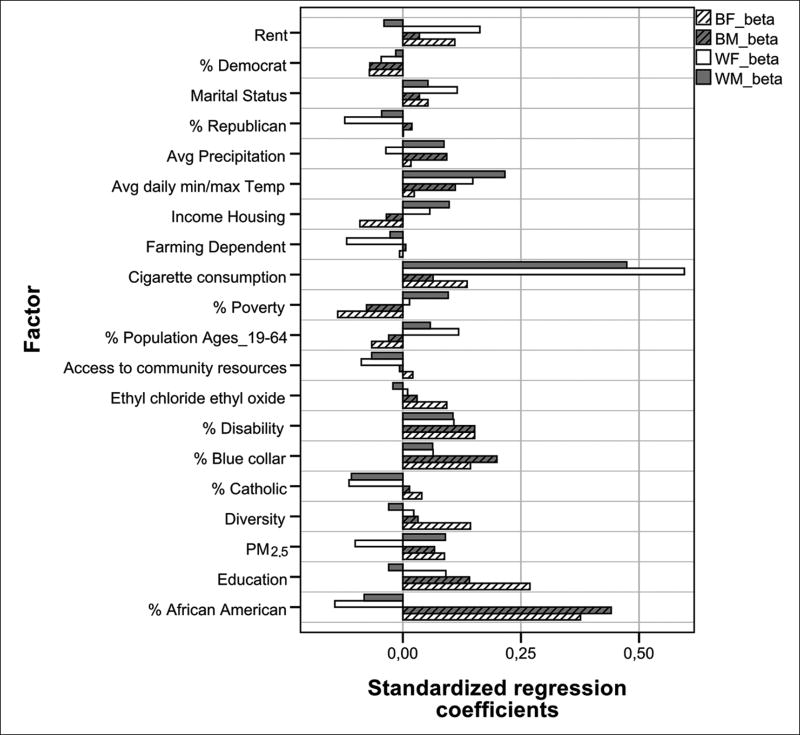

Mean rates and standard deviations of age adjusted, lung cancer mortality rates per 100,000 in the 2067 counties were 193.59 ± 61.11 for WM, 110.15 ± 33.41 for WF, 120.7 ± 122.27 for BM, and 42.18 ± 49.92 for BF. Standardized regression models were used to render the cumulative effect of combined factors for the highest zero order correlations and to confirm the main role of the most important variables in each model (nonstandardized regression models are presented in Tables 2 and 3 of the supplemental materials). Cigarette consumption contributed the greatest explanation of lung cancer mortality rates for both WM and WF (β = 0.47 and β = 0.60, respectively) while % vulnerable African Americans (comprised variables: % African American, low birth weight, very low birthweight, unmarried, chlamydia, and gonorrhea) contributed the greatest explanation of lung cancer mortality for BM and BF (β = 0.44 and β = 0.38, respectively). % disabled and rent were found to have significant, yet weak, positive coefficients across all four, race×gender models [Table 1].

Table 1.

List of Variables by Domain, Clique, Factor and Year

| Exposome domain | Factor names | Variable number | Variable name | Clique factor | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Ethyl dichloride and ethylene oxid | V110 | Cancer risk in a million due to ethyl dichloride | Clique 1 Factor 55 | 2005 |

| V112 | Cancer risk in a million due to ethylene oxide | 2005 | |||

| Avg daily min/maxTemp | V131 | Max Temp July | Clique 1 Factor 1 | 2000 | |

| V132 | Max Temp July | 2005 | |||

| V137 | Min Temp July | 2000 | |||

| V13 | Percentage housing units heated by electricity | 2000 | |||

| V188 | Low literacy_percentage | ||||

| V20 | LT_hi_school_percentage | 2005 | |||

| V2115 | Cancer risk in a million due to acetaldehyde | 2005 | |||

| V2131 | Cancer risk in a million due to formaldehyde | ||||

| V2151 | AvgDaily_Min_Air_Temp | ||||

| V220 | M_LT65_NO_HLTH_INS_percentage | 2006 | |||

| V468 | MILK_PRICE | ||||

| V499 | AvgDailyMax Heat Index_F | ||||

| V591 | F_divorce | 2009 | |||

| V604 | DM_Temp_99 TO | ||||

| V607 | DAYS_HI_90 | ||||

| V608 | DAYS_HI_100 | ||||

| V609 | DAYS_MX_T_90 | ||||

| V620 | Premature | ||||

| V621 | Under_18 | ||||

| V662 | Land_surf_temp_day | ||||

| V663 | Land_surf_night | ||||

| V664 | Temp_min | ||||

| V665 | Sunlight | ||||

| V700 | AvgDailySunlight | 1979 | |||

| V701 | AvgDayLandSurfaceTemp_F | ||||

| V702 | AvgNightLandSurfaceTemp_F | ||||

| V833 | Avgdaily_max_heat_index | ||||

| Precipitation | V665 | Precip | Clique 1 Factor 31 | ||

| V951 | Ave Daily Precip | 1980 | |||

| V952 | Ave Daily Precip | 1985 | |||

| V953 | Ave Daily Precip | 1990 | |||

| PM2.5 | V111 | Cancer risk in a million due to Ethylene dibromide | Clique 1 Factor 8 | ||

| Cancer risk in a million due to | 2005 | ||||

| V2118 | acrylonitrile | 2005 | |||

| V588 | Ave Fine Part | ||||

| Built | Access to neighborhood facilities | V423 | House No Car GT 10 Miles to Store | 2006 | |

| V424 | Low income GT 10 | 2010 | |||

| Miles to store | 2010 | ||||

| V65 | Percentage population, | 2010 | |||

| low access to store 2010 | 2010 | ||||

| V66 | Percentage population, low-income access | 2010 | |||

| to store 2010 | |||||

| V67 | Percentage population, children low access | 2010 | |||

| to store 2010 | 2010 | ||||

| V68 | Percentage population, seniors, low access to store | ||||

|

| |||||

| Exposome domain | Variable category | Variable number | Variable name | Clique factor | Year |

|

| |||||

| Farming dependent | V234 | Farming-dependent typology code 2004 | Clique1 Factor 351 | 2004 | |

| Social | Percentage vulnerable African American | V184 | Black Isolation Index 2000 | Clique 1 Factor 9 | 2000 |

| V211 | Black Pop percentage | ||||

| V29 | AA Pop percentage | ||||

| V487 | Non-Hispanicblack percentage | 2008 | |||

| V618 | Low birth weight | ||||

| V619 | Very low birth weight | ||||

| V623 | Unmarried | ||||

| V638 | #/1000 black protestant | ||||

| V761 | Chlamydia | 2006 | |||

| V762 | Gonorrhea | 2006 | |||

| V936 | Probability that blacks will meet other blacks | 1990 | |||

| Blue collar workers | V174 | Percentage Black BlueCollar Workers 2000 | Clique 1 Factor 65 | 2000 | |

| V176 | Renting blacks percentage | 2000 | |||

| Diversity | V501 | Diversity | Clique 1 Factor 30 | 2000 | |

| V932 | Thiel Index (diversity) | 1990 | |||

| V939 | 1990 White’s RCL measure | 1990 | |||

| V940 | 1990 Spatial Proximity Index | 1990 | |||

| Disabled | V633 | Dis_Am per 1000 All | Clique 1 Factor 124 | 2003–2005 | |

| V634 | Dis_Am_White | 2003–2005 | |||

| Rent | V2157 | Rent estimates at the 50th percentile 0 | Clique 1 Factor 12 | 2010 | |

| V2158 | Rent estimates at the 50th percentile 1 | 2010 | |||

| V2159 | Rent estimates at the 50th percentile _2 | 2010 | |||

| V2160 | Rent estimates at the 50th percentile _3 | 2010 | |||

| V2161 | Rent estimates at the 50th percentile 4 | 2010 | |||

| SES/education/income | V227 | W Collar Wrkr percentage | Clique 1 Factor 302 | 2010 | |

| V22 | Bachlr Degree + percentage | 2010 | |||

| V23 | Grad or Prof Degree percentage | 2010 | |||

| V26 | Educ Index | ||||

| V46 | Manage Prof _occs percentage | ||||

| V538 | Median House Inc W | 2010 | |||

| V541 | Per Cap Inc W | 2010 | |||

| V587 | Ed hi school W percentage | 2010 | |||

| V615 | Ave life expectancy | 2000 | |||

| V942 | Household income total pop | 2000 | |||

| V943 | Household income (for population age 65 or older) | 2000 | |||

| Percentage democrats HH Income | V192 | Democrats percentage | Clique 1 Factor 351 | 2004 | |

| V193 | Democrats percentage | 2008 | |||

| V25 | Median Personal Earning | Clique 1 Factor 306 | 2010 | ||

| V27 | Income Index | ||||

| V36 | Labor Force Part GE16 percentage | ||||

| V492 | Med Household Income | 2008 | |||

| V584 | Med household Income W | 2000 | |||

| Percentage republican Poverty | V189 | Republican percentage | Clique 1 Factor 25 | 2004 | |

| V190 | Republican percentage | 2008 | |||

| V186 | GINI | Clique 1 Factor 7 | 2000 | ||

| V241 | Low Educ 04 | 2004 | |||

| V242 | Low Employ 04 | 2004 | |||

| V243 | Persist Poverty 04 | 2004 | |||

| V35 | Gini Coefficient | ||||

| V37 | Poverty below fed percentage | ||||

| V389 | Medicaid eligible total | ||||

| V38 | Child poverty percentage | ||||

| V390 | Medicaid Eligible M | ||||

| V391 | Medicaid Eligible F | ||||

| V393 | Medi/Medi Dual eligible | ||||

| V403 | Food stamp recipients percentage | 2005 | |||

| V41 | Children less than 5 poverty percentage | ||||

| V422 | Low income GT 1 mile to store | 2006 | |||

| V441 | Adults 65+ poverty percentage | ||||

| V458 | Snap St | 2008 | |||

| V493 | Free lunch percentage | 2008 | |||

| V495 | Poverty rate 08 | 2008 | |||

| V496 | Child poverty percentage | 2000 | |||

| V536 | Income less than poverty W | 2010 | |||

| V585 | Poverty white percentage | 2000 | |||

| V945 | RS 00 | 2000 | |||

| V946 | Atkin | 2000 | |||

| V947 | RS90 | 1990 | |||

| Cigarette consumption | V222 | Unemployment rate | Clique 1 Factor 2 | ||

| V383 | Medicare enrollment Disab Tot | ||||

| V384 | MEDCR_ENROL_DISABL_HI_ percentage | 2000 | |||

| V385 | MEDCR_ENROL_DISABL_SMI percentage | 2000 | |||

| V392 | MEDCD_ELIG_BLIND | 2000 | |||

| V456 | LOW Income_SP percentage | 2007 | |||

| V475 | DIABETES_ADULTS percentage | 2000 | |||

| V476 | OBESE_ADULTS percentage | 2000 | |||

| V51 | Prod_trans_moving_occs percentage | ||||

| V520 | Educ_Less_HS_M_W | 2010 | |||

| V521 | Educ_HS_M_W | 2010 | |||

| V524 | Educ Less HS F W | 2010 | |||

| V525 | Educ HS F W | 2010 | |||

| V543 | SNAP W | 2010 | |||

| V557 | Blue Col W | 2000 | |||

| V558 | Blue Col WM | 2000 | |||

| V565 | adj_ictive percentage | 2009 | |||

| V586 | Ed low W percentage | 2000 | |||

| V58 | LT HS percentage | 2000 | |||

| V59 | HS degree percentage | 2000 | |||

| V602 | Single Family W | 2010 | |||

| V661 | Age Adj Obesity | 2009 | |||

| V703 | Ave M | 2000 | |||

| V704 | Ave M | 2005 | |||

| V705 | Ave F | 2000 | |||

| V706 | Ave F | 2005 | |||

| V778 | Cig M 96 | 1996 | |||

| V779 | Cig M 97 | 1997 | |||

| V780 | Cig M 98 | 1998 | |||

| V781 | Cig M 99 | 1999 | |||

| V782 | Cig M 00 | 2000 | |||

| V783 | Cig M 01 | 2001 | |||

| V784 | Cig M 02 | 2002 | |||

| V785 | Cig M 03 | 2003 | |||

| V786 | Cig M 04 | 2004 | |||

| V787 | Cig M 05 | 2005 | |||

| V788 | Cig M 06 | 2006 | |||

| V789 | Cig M 07 | 2007 | |||

| V790 | Cig M 08 | 2008 | |||

| V791 | Cig M 09 | 2009 | |||

| V792 | Cig M 10 | 2010 | |||

| V793 | Cig F 96 | 1996 | |||

| V794 | Cig F 97 | 1997 | |||

| V795 | Cig F 98 | 1998 | |||

| V796 | Cig F 99 | 1999 | |||

| V797 | Cig F 00 | 2000 | |||

| V798 | Cig F 01 | 2001 | |||

| V799 | Cig F 02 | 2002 | |||

| V800 | Cig F 03 | 2003 | |||

| V801 | Cig F 04 | 2004 | |||

| V802 | Cig F 05 | 2005 | |||

| V803 | Cig F 06 | 2006 | |||

| V804 | Cig F 07 | 2007 | |||

| V805 | Cig F 08 | 2008 | |||

| V806 | Cig F 09 | 2009 | |||

| V807 | Cig F 10 | 2010 | |||

| V808 | Cig B 96 | 1996 | |||

| V809 | Cig B 97 | 1997 | |||

| V810 | Cig B 98 | 1998 | |||

| V811 | Cig B 99 | 1999 | |||

| V812 | Cig B 00 | 2000 | |||

| V813 | Cig B 01 | 2001 | |||

| V814 | Cig B 02 | 2002 | |||

| V815 | Cig B 03 | 2003 | |||

| V816 | Cig B 04 | 2004 | |||

| V817 | Cig B 05 | 2005 | |||

| V818 | Cig B 06 | 2006 | |||

| V819 | Cig B 07 | 2007 | |||

| V820 | Cig B 08 | 2008 | |||

| V821 | Cig B 09 | 2009 | |||

| V822 | Cig B 10 | 2010 | |||

| Marital status | V505 | Mar Stat Mar W | Clique 1 Factor 14 | 2010 | |

| V506 | Mar Status Mar WM | 2010 | |||

| V507 | Mar Status Mar WF | 2010 | |||

| Percentage catholic | V640 | Percentage catholic | Clique 1 Factor 100 | ||

SES: Socioeconomic status, PM2.5: Particulate matter

For WM, other significant factors with weak positive coefficients included average daily min/max average temperature, % disabled, household income, poverty, PM2.5, precipitation, rent, and % of population age 19–64. % Catholic, % vulnerable African American, and access to neighborhood facilities had statistically significant but weak negative coefficients [Table 1]. For WF, factors with significant, but weak, positive correlations in explaining lung cancer mortality, in descending order were: rent, daily min/max average temperature, % of population age 19–64, marital status, and % disabled. Access to neighborhood facilities, PM2.5, % Catholic, farm dependent, and % vulnerable African American had weak negative coefficients. For BM, % vulnerable African American had the highest but moderate contribution (β = 0.44), followed by weak positive contributions for rent, % disabled, education, average min/max daily temperature, precipitation, and PM2.5, whereas cigarette consumption was nonsignificant at P < 0.0001 threshold, with a weak β = 0.06 (P < 0.05). In the case of BF, 20 factors accounted for a R2 = 0.48. Nine factors had significant positive P values, whereas two factors had negative, significant coefficients. Among these, % vulnerable African American was the highest contributing factor, with a moderate β = 0.38, followed by weak contributions of education, % disability, diversity, cigarette consumption, rent, and PM2.5, with β between 0.10 and 0.20. A factor comprised of ethyl dichloride and ethylene oxide, and PM2.5 had weak, negative β coefficients.

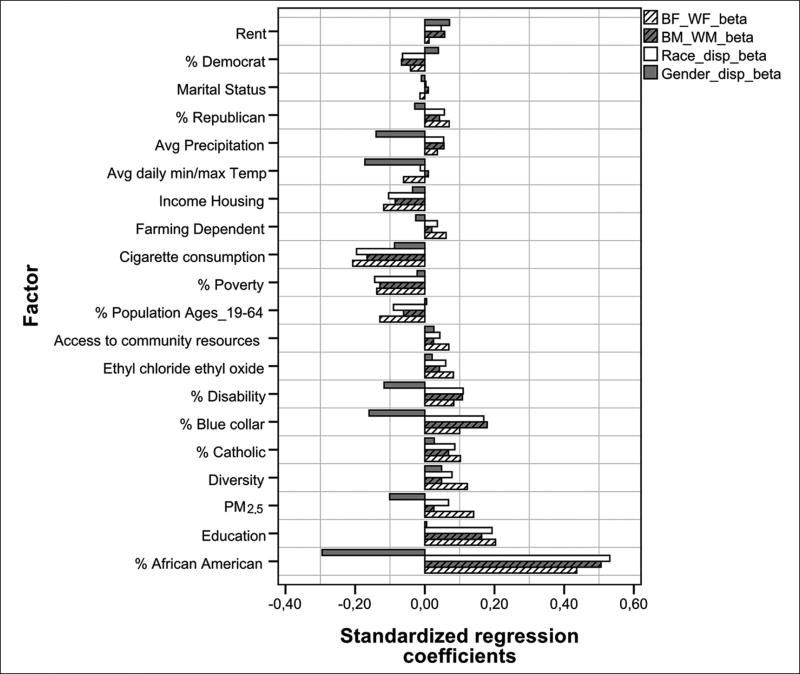

Lung cancer mortality disparities

Additional regression models were used to calculate the relative contribution of environmental exposures on lung mortality disparities rates between WM and BM; WF and BF; WM and WF, and BM and BF (race); and WM and BM, and WF and BF (gender) at the P < 0.0001 threshold. Seven factors contributed positively and three negatively to black: white, racial, lung cancer morality disparities [Figures 2 and 3]. Positive β included % vulnerable African American, education, rent, % disability, % catholic, and PM2.5. Factors with negative β were cigarette consumption, poverty, and % population age 19–64. % Vulnerable African American had a strong effect and the others contributed weakly. Six coefficients contributed negatively and none positively to M/F gender disparities including % vulnerable African American, min/max average temperature, rent, average precipitation, % disability, and PM2.5. Disparities between WM and BM were accounted for largely by % vulnerable African American (β = 0.51). Other positive, but weak coefficients included rent, % disability, and education. Negative β included cigarette consumption, poverty, and % population 19–64. Significant β that contributed weakly to disparities between WF and BF included education, diversity, rent, and % disability. Cigarette consumption contributed negatively and weakly to gender disparities.

Figure 2.

Comparison of standardized regression coefficients of factors included in four models to explain lung cancer mortality rates for WM, WF, BM, and BF population. Factors are a combination of multiple years of data

Figure 3.

Comparison of standardized regression coefficients of factors included in four models to explain lung cancer mortality disparities rates for BF-WF, BM-WM, B-W, M-F population. Factors are a combination of multiple years of data

DISCUSSION

Results of this study suggest that county level, race, and gender differences in cigarette consumption, % vulnerable African American, level of education, % blue collar workers, access to neighborhood resources, housing as a % of income, and diversity, as well as differences in direct exposures to ethyl dichloride and ethylene oxide, min/max average temperature, PM2.5 and precipitation are associated with lung cancer mortality and/or race×gender mortality disparities. Of particular interest is the impact of cigarette consumption on lung cancer mortality disparities. While cigarette consumption is clearly the leading cause of lung cancer overall, it contributes less to our understanding of lung cancer mortality between BM and BF as compared to WM and WF and contributes little to our understanding of race×gender mortality disparities. Interpretation of our findings based on the previous research suggests that cigarette consumption, ethyl dichloride and ethylene oxide, and PM2.5 are etiologic chemical agents associated with lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities. In parallel, % vulnerable African American, level of education, % blue collar workers, % disability, access to neighborhood resources, housing as a % of income, and diversity would appear to be moderating social determinants that impact lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities. Our mapping of exposures using GIS suggests that other variables, such as temperature, precipitation, % Catholic, % democrat, and % republican, may be co occurring or spurious and simply reflect regional differences found in Southern states [Supplemental Figures 1–24: Maps in Supplemental materials].

Public health implications

From primary prevention to survivorship, the pathway to lung cancer mortality and race×gender disparities is profoundly affected by environmental exposures. To date, limited research has examined the combined effects of multiple factors that affect lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities. By curating large amounts of disparate, heterogeneous data, an exposome approach provides public health researchers with an opportunity to harness existing secondary data, generate and test hypotheses, and consider the complex role of chemical and nonchemical environmental stressors.

The exposome database and graph theoretical toolchain can also be used to assess the effectiveness of specific risk reduction interventions that test the intervention itself without the traditional limitations inherent to the technical validity of the public health action to be tested. This is particularly relevant where social determinants often act as powerful confounders to underlying etiologic factors that cause poor health outcomes hampering conclusive findings. While lung cancer mortality was used as a “demonstration case,” this approach has applicability to other priority adverse health conditions.

Enabling evidence based science

A major contribution of the public health exposome is that it provides a novel approach for considering the effects of multiple environmental stressors on health outcomes and racial disparities. A second contribution is enabling a dual derivation of testable hypotheses. The graph theoretical toolchain is capable of transforming high volume, disparate heterogeneous data comprised chemical and nonchemical environmental stressors to support both hypothesis generating and hypothesis testing inquiries. This data driven approach is epidemiologically significant in that it provides new opportunities for identifying populations at risk, risk and protective factors, and spatial and temporal measures of exposure. Together, these approaches increase the likelihood that environmental health research will address the public health concerns of affected communities, provide opportunities for meaningful, bi directional, community engaged research, and lay the fertile foundation for community academic partnerships working to collaboratively translate research findings into effective public health policy and practice.

CONCLUSIONS

The exposome paradigm offers a new risk assessment approach to assess the effects of multiple chemical and nonchemical environmental stressors on health outcomes and disparities. It provides public health providers and officials the tools to use “big data” and computational tools in conjunction with traditional biostatistics to analyze complex exposome relationships and to develop and evaluate targeted community health promotion, risk reduction, and health disparities interventions. Graph theoretical algorithms and computational analyses are capable of transforming high volume, heterogeneous, secondary exposure data, spanning the natural, built, and social environments, beyond that which is typically used in traditional, narrowly focused, observational studies. A public health exposome approach provides epidemiologically significant opportunities to identify environmental exposures associated with complex health outcomes and disparities and supports further biostatistical analysis, including factor analysis and multiple regression, multi level, and spatial temporal analyses, GIS and data visualization, and predictive modeling. The use of these analytics is particularly relevant in health disparities research, where mediating and moderating factors influencing disparities often are powerful confounders.

Limitations

Limitations in this study include the validity and reliability of existing public available data sets; environmental stressor data reflect different years; data are population level measures; and not all individuals in a given county are equally affected by a specific stressor.

Directions for future work

An exposome approach, database, and graph theoretical toolchain provides public health professionals with a novel set of tools for analyzing large, multiple, heterogeneous, secondary data sets that can be used both for generating and testing hypotheses and for targeting and evaluating public health interventions. This novel study demonstrates how the public health exposome approach and database comprised chemical and nonchemical stressors from the natural, built, and social environments coupled with a graph theoretical toolchain affords us an opportunity to examine the effects of multiple exposures across various domains on lung cancer mortality and mortality disparities [Figures 2 and 3]. While lung cancer mortality was used here as a “demonstration case,” the benefits of a public health exposome approach coupled with scalable combinatorial analytics are universal and can be applied to many complex health issues.

The complex causes and correlates of poor health outcomes and health disparities support the need to move beyond individual risk assessment models to cumulative risk assessment models which not only incorporate multiple exposures across various domains but also can identify exposures across the life course and the life stage at which the exposures occurs. We currently are updating the public health exposome database to include smaller spatial and temporal units (from county to sub county areas and annual to daily measures—where available) while expanding the database to span the full 30 years of environmental stressors. This will allow us to model both the spatial and temporal dimensions of environmental exposures, more accurately distinguish between etiologic, mediating, and co occurring factors, and move toward a more robust cumulative assessment of environmental exposures across the lifespan. These measures should help us achieve the full potential of the exposome.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Regression models (non-standardized coefficients) for lung cancer mortality rates by race and gender for 20 environmental exposure factors

| Variable name | Black female (R2=0.60) | Black male (R2=0.57) | White female (R2=0.53) | White male (R2=0.62) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| St.B | P | St.B | P | St.B | P | St.B | P | |

| Percentage vulnerable African-American | 0.376 | <0.0001 | 0.441 | <0.0001 | −0.144 | 0.2441 | −0.082 | 0.5462 |

| SES/education/income | 0.269 | <0.0001 | 0.141 | <0.0001 | 0.091 | 0.293 | −0.030 | <0.0001 |

| Ambulatory care discharges | 0.152 | <0.0001 | 0.152 | <0.0001 | 0.108 | <0.0001 | 0.106 | <0.0001 |

| Blue collar workers | 0.143 | <0.0001 | 0.199 | <0.0001 | 0.064 | <0.0001 | 0.063 | <0.0001 |

| Diversity | 0.143 | <0.0001 | 0.032 | 0.0043 | 0.023 | 0.1249 | −0.030 | 0.2782 |

| Poverty | −0.138 | 0.0005 | −0.077 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.0259 | 0.096 | 0.03 |

| Cigarette consumption | 0.136 | 0.0009 | 0.064 | 0.0004 | 0.596 | <0.0001 | 0.474 | <0.0001 |

| Adulthood | −0.066 | 0.0012 | −0.030 | 0.0999 | 0.118 | <0.0001 | 0.058 | 0.0056 |

| Ethyl dichloride and ethylene oxide | 0.093 | 0.002 | 0.030 | 0.1447 | 0.010 | 0.1517 | −0.021 | 0.075 |

| PM2.5 | 0.088 | 0.0032 | 0.067 | 0.0417 | −0.101 | 0.0695 | 0.090 | 0.4733 |

| Rent | 0.110 | 0.004 | 0.035 | 0.3867 | 0.163 | <0.0001 | −0.040 | 0.22 |

| Marital status | 0.053 | 0.0085 | 0.035 | 0.1434 | 0.115 | <0.0001 | 0.053 | <0.0001 |

| Percentage catholic | 0.040 | 0.0091 | 0.014 | 0.1163 | −0.114 | 0.0023 | −0.109 | 0.0003 |

| Percentage income housing | −0.091 | 0.015 | −0.035 | 0.2696 | 0.057 | 0.7622 | 0.098 | 0.0026 |

| Access to neighborhood facilities | 0.021 | 0.0786 | −0.007 | 0.9579 | −0.088 | <0.0001 | −0.066 | <0.0001 |

| Ave daily minimum/maximum temperature | 0.024 | 0.0887 | 0.111 | 0.0001 | 0.148 | <0.0001 | 0.216 | <0.0001 |

| Precipitation | 0.017 | 0.2715 | 0.093 | 0.027 | −0.036 | 0.9498 | 0.087 | 0.1711 |

| Percentage democrats | −0.071 | 0.3504 | −0.070 | 0.5195 | −0.046 | 0.3428 | −0.015 | 0.5248 |

| Percentage republicans | 0.001 | 0.6917 | 0.019 | 0.5166 | −0.123 | 0.3188 | −0.045 | 0.7091 |

| Farming dependent | −0.007 | 0.9164 | 0.006 | 0.391 | −0.119 | <0.0001 | −0.027 | 0.003 |

SES: Socioeconomic status, PM2.5: Particulate matter

Table 3.

Regression Summary (non-standardized coefficients): Lung Cancer Mortality Disparities by Race and Gender Differences for 20 Environmental Exposure Factors

| Effect | Difference black

|

Difference female – male (R2=0.40) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (R2=0.64)

|

White female (R2=0.55)

|

White male (R2=0.57)

|

|

|||||

| B | P | B | P | B | P | B | P | |

| Intercept | 39.7423 | 29.4418 | 22.6925 | −155.5 | ||||

| Percentage vulnerable African-American | 68.4521 | <0.0001 | 20.4956 | <0.0001 | 47.9361 | <0.0001 | −24.8206 | <0.0001 |

| Education | 42.9121 | <0.0001 | 11.2358 | <0.0001 | 30.3656 | <0.0001 | −1.3533 | 0.7505 |

| Am care discharges | 29.4984 | <0.0001 | 6.8707 | 0.0001 | 22.3544 | <0.0001 | −22.2268 | <0.0001 |

| Blue-collar workers | 22.4462 | <0.0001 | 4.7944 | <0.0001 | 18.3492 | <0.0001 | −19.3076 | <0.0001 |

| Diversity | 13.8324 | <0.0001 | 7.0338 | <0.0001 | 6.8754 | 0.0011 | 3.9208 | 0.0563 |

| Percentage catholic | 0.09709 | <0.0001 | 0.03935 | <0.0001 | 0.05927 | 0.0008 | 0.008617 | 0.6136 |

| Adulthood | −3.4361 | <0.0001 | −1.8126 | <0.0001 | −1.8253 | 0.0074 | 0.2071 | 0.7572 |

| Access to neighborhood facilities | 9.8296 | 0.001 | 5.1129 | <0.0001 | 4.5175 | 0.0562 | 3.243 | 0.1653 |

| Poverty | −16.591 | 0.0016 | −4.6128 | 0.0209 | −13.5109 | 0.0011 | 0.2 | 0.9599 |

| Cigarette consumption | −17.716 | 0.0022 | −11.29 | <0.0001 | −7.4122 | 0.1023 | −14.8588 | 0.0006 |

| Farming dependent | 20.6137 | 0.0087 | 10.25 | 0.0009 | 10.8743 | 0.0812 | −9.5416 | 0.12 |

| Household income | −12.3698 | 0.0111 | −4.965 | 0.0089 | −7.8362 | 0.0422 | −3.092 | 0.4134 |

| PM2.5 | 13.7856 | 0.0738 | 7.1825 | 0.0021 | 6.2524 | 0.2682 | −12.3042 | 0.009 |

| Precipitation | 7.1263 | 0.1489 | 2.3893 | 0.1556 | 4.9239 | 0.1889 | −10.6006 | 0.0017 |

| Rent | −5.4679 | 0.201 | −0.7001 | 0.6647 | −4.1881 | 0.2121 | 9.0612 | 0.0049 |

| Percentage republicans | 13.0722 | 0.2222 | 5.3362 | 0.2092 | 7.3887 | 0.3863 | −4.4555 | 0.5982 |

| Ethyl dichloride and ethylene oxide | 3.519 | 0.4712 | 2.5348 | 0.1444 | 2.4263 | 0.5198 | −2.4157 | 0.4868 |

| Percentage democrats | −6.2186 | 0.5643 | −1.8081 | 0.673 | −4.1303 | 0.6309 | 1.0789 | 0.8993 |

| Temperature | 1.5381 | 0.8149 | −1.8134 | 0.3901 | 4.2215 | 0.3885 | −19.6804 | <0.0001 |

| Marital status | −3.0914 | 0.9599 | −5.5085 | 0.8198 | −1.6401 | 0.9732 | −23.943 | 0.6188 |

PM2.5: Particulate matter

Acknowledgments

Financial support and sponsorship

This research has been supported in part by start up packages received from Meharry Medical College for the Health Disparities Research Center of Excellence (PDJ) and the Ohio State University (DBH) and by the National Institutes of Health under award R01AA018776 (MAL) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. [Last accessed on 2017 June 15];Data Liberation Initiative. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/dli/dli.

- 2.NIH-NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 16];SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Lung and Bronchus Cancer. Available from: http://www.seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 16];Trends in Current Smoking by High School Students and Adults – United States, 1965–2014. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/tables/trends/cig_smoking/index.htm.

- 4.Silverberg E, Grant RN. Cancer statistics, 1970. CA Cancer J Clin. 1970;20:11–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 16];Cancer Facts & Figures. 2014 Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/webcontent/acspc-042151.pdf.

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking – 50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Research Council (U.S.) Health Effects of Exposure to Radon: BEIR VI. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. Committee on Health Risks of Exposure to Radon. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pope CA, 3rd, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Ito K, et al. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA. 2002;287:1132–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamra GB, Guha N, Cohen A, Laden F, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Samet JM, et al. Outdoor particulate matter exposure and lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:906–11. doi: 10.1289/ehp/1408092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Field RW, Withers BL. Occupational and environmental causes of lung cancer. Clin Chest Med. 2012;33:681–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, Whitmill J, Babb SD, Graffunder CM. Current cigarette smoking among adults – United States, 2005–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1205–11. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2013 Incidence and Mortality Web-Based Report. Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2016. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 12]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/npcr/uscs/download_data.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virnig BA, Baxter NN, Habermann EB, Feldman RD, Bradley CJ. A matter of race: Early-versus late-stage cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:160–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aizer AA, Wilhite TJ, Chen MH, Graham PL, Choueiri TK, Hoffman KE, et al. Lack of reduction in racial disparities in cancer-specific mortality over a 20-year period. Cancer. 2014;120:1532–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Institute. Cancer Progress Report 2003. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alberg AJ, Samet JM. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Chest. 2003;123(1 Suppl):21S–49S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.21s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams PR, Dotson GS, Maier A. Cumulative Risk Assessment (CRA): Transforming the way we assess health risks. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:10868–74. doi: 10.1021/es3025353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kershenbaum AD, Langston MA, Levine RS, Saxton AM, Oyana TJ, Kilbourne BJ, et al. Exploration of preterm birth rates using the public health exposome database and computational analysis methods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:12346–66. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111212346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tiwari C, Beyer K, Rushton G. The impact of data suppression on local mortality rates: The case of CDC WONDER. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1386–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borate BR, Chesler EJ, Langston MA, Saxton AM, Voy BH. Comparison of threshold selection methods for microarray gene co-expression matrices. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:240. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langston MA, Levine RS, Kilbourne BJ, Rogers GL, Kershenbaum AD, Baktash SH, et al. Scalable combinatorial tools for health disparities research. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:10419–43. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chesler EJ, Langston MA. Combinatorial genetic regulatory network analysis tools for high throughput transcriptomic data. In: Eskin E, editor. Systems Biology and Regulatory Genomics. Vol. 4023. San Diego, CA, USA: Springer; 2006. pp. 150–65. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagan RD, Langston MA, Wang K. Lower bounds on paraclique density. Discrete Appl Math. 2016;204:208–12. doi: 10.1016/j.dam.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheskin DJ. Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedures. London, New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.