Summary

Once interferon-tau (IFNT) had been identified as a Type I IFN in sheep and cattle and its functions characterized, numerous studies were conducted to elucidate transcriptional regulation of this gene family. Transfection studies performed largely with human choriocarcinoma cell lines identified regulatory regions of the IFNT gene that appeared responsible for trophoblast-specific expression. The key finding was the recognition that the transcription factor ETS2 bound to a proximal region within the 5/UTR of a bovine IFNT and acted as a strong transactivator. Soon after other transcription factors were identified as cooperative partners. The ETS2-binding site and the nearby AP1 site enable response to intracellular signaling from maternal uterine factors. The AP1 site also serves as a GATA binding site in one of the bovine IFNT genes. The homeobox-containing transcription factor, DLX3, augments IFNT expression combinatorially with ETS2. CDX2 has also been identified as transactivator that binds to a separate site upstream of the main ETS2 enhancer site. CDX2 participates in IFNT epigenetic regulation by modifying histone acetylation status of the gene. The IFNT down-regulation at the time of the conceptus attachment to the uterine endometrium appears correlated with the increased EOMES expression and the loss of other transcription coactivators. Altogether, the studies of transcriptional control of IFNT have provided mechanistic evidence of the regulatory framework of trophoblast-specific expression and critical expression pattern for maternal recognition of pregnancy.

Introduction

The function of the proteins that we now recognize as IFNT was established before their primary structures were known. The cloning and sequencing of the cDNAs reported thirty years ago caused considerable surprise, because Type I IFN, which include the related IFNA and IFNB families, had always been assumed to be antiviral agents, expressed for a brief time in response to a viral infection and then secreted in order to stimulate viral resistance in target cells elsewhere in the body. What makes the IFNT unique, however, is not their ability to extend estrous cycle length in ruminants, since IFNA can accomplish this quite effectively (Green, et al. 2005). Nor do the IFNT demonstrate reduced antiviral activity compared to their relatives; quite the opposite, they are quite potent in this respect and bind to the same receptors as all other Type I IFNT. Instead, the uniqueness of the IFNT lies in their transcriptional control, which provides trophoblast-specific, time-specific, constitutive expression in absence of a viral challenge. Additionally, production of IFNT is exceptionally high over the few days. As pointed out in the accompanying chapter of Ealy and Woolridge (Ealy and Woolridge 2017), the relatively recent evolution of the IFNT genes required the acquisition of distinctive regulatory sequences upstream of their transcription start sites. Although the topic of transcriptional control of IFNT expression has been reviewed previously (Ealy and Yang 2009, Roberts 2007, Roberts, et al. 2008), the review presented here is more comprehensive than the earlier ones. Our goal herein is to update the reader with the most recent literature on the topic and to attempt to resolve some conflicting results.

1. Different transcriptional control of IFNT from other Type I Interferon family genes

IFNT is a member of the Type I Interferon family that is expressed exclusively in trophectoderm in the early stage of trophoblast development (Farin, et al. 1990) in the suborder Ruminantia (Leaman and Roberts 1992, Liu, et al. 1996, Roberts, et al. 1992). As pointed out in the previous section, expression of IFNT is not inducible by viral infection but is sustained constitutively at high levels over several days during the preimplantation period (Cross and Roberts 1991) (Roberts 2007). Additionally, the signaling pathways and transcriptional activators that promote the upregulation of other Type I gene families, such as IFNA and IFNB, are not involved in the regulatory control of the IFNT (Leaman, et al. 1994). The realization that the transcriptional regulation of IFNT genes is distinct from that of other type I IFN genes (Flint, et al. 1994, Roberts, et al. 1992) represented an obvious challenge to those in the field.

Initial studies utilized up to −1675 bp (originally referred BTP-1.8 (Cross and Roberts 1991) of the 5/-regulatory region of bovine IFNT1A gene, which was placed into a reporter plasmid (Cross and Roberts 1991, Leaman, et al. 1994). JAr cells became the cell line of choice to study transcriptional control because fast-growing ovine trophoblast lines were not available. It was also reasoned that trophoblast cells, like JAr, despite their human origin might express much of the basic transcriptional machinery that would permit IFNT regulatory region to be active. Truncation of the longer BTP-1.8 construct quickly revealed that regions within 450 bp from the transcriptional start site allowed constitutive expression. The finding is consistent with the observation that the more proximal regions of the bovine and ovine IFNT genes are highly conserved (Leaman and Roberts 1992). So-called “mobility-shift electrophoresis” or “gel-shift” experiments performed with crude nuclear extracts prepared from ovine conceptuses during the period of IFNT expression revealed a strong interaction of nuclear protein interaction with two regions, a proximal (−91 to −69 bp from the transcriptional start site) and a more distal site (−358 to −322 bp) (Leaman, et al. 1994). These were assumed to represent major sites of transcriptional control. Such interactions were not observed with extracts form older conceptuses that were not expressing IFNT at the time they were recovered. These gel-shift experiments provided a useful beginning to subsequent transcriptional control studies as they mirrored IFNT expression over time and implicated particular control regions likely to interact with transcription factors.

2. Transcription factors regulating IFNT expression

2-1. Regulatory mechanisms that up-regulate IFNT gene expression

ETS2 enhancer region

To identify the factor(s) responsible for IFNT gene transcription, the proximal protein binding region was employed as the bait sequence for a yeast one-hybrid screening with a day 13 ovine conceptus cDNA library, from which the transcription factor ETS2 was identified (Ezashi, et al. 1998). ETS2 is a member of the ETS family of transcription factors that share a conserved ETS DNA-binding domain that recognizes a specific binding motif centered on a GGAA core. Active IFNT genes contain an ETS binding site in the proximal site, whereas several ovine IFNT gene that are poorly expressed and could be “pseudogenes” contain a mutated core motif (TGAA) in the proximal binding site (Ezashi, et al. 1998, Matsuda-Minehata, et al. 2005). Overexpression of ETS2 strongly transactivated an IFNT reporter, while specific mutation of the ETS2 binding sequence substantially reduced both the basal and induced activity in the JAr cells (Das, et al. 2008, Ezashi, et al. 2008, Ezashi, et al. 2001, Ezashi and Roberts 2004). When a 6 bp CAGGAA ETS2 core binding sequence (Fig. 1C) was inserted into the equivalent region of the pseudogenes, the reporter still failed to confer higher ovine IFNT expression or induction with ETS2 overexpression. However, if the replacement nucleotide cassette was extended to 22 bp on both ends from the ETS2 site and included an adjacent putative AP1 site from active ovine IFNT (ovIFNT-o10), full promoter activity of the ovine IFNT gene in response to ETS2 was restored (Matsuda-Minehata, et al. 2005). This experiment indicated the importance of the neighboring sequences to the core ETS2 binding site. Finally, ETS2 was significantly more efficient than related ETS family transcription factors, such as ELF1, ETS1, FLI1, ETV4, SPI1, and was concurrently expressed with IFNT in trophectoderm of d 15 ovine conceptuses (Ezashi, et al. 1998).

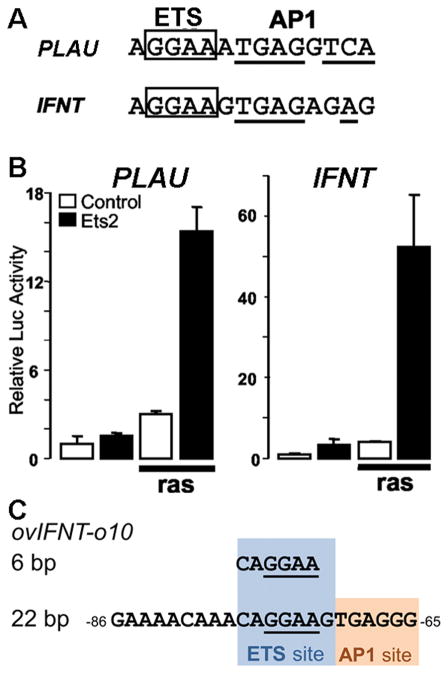

Fig. 1.

(A) Sequences of the ETS/AP1 binding sites of the murine PLAU and bovine IFNT1A control regions. The ETS core binding sequences are boxed. Conserved AP1 binding site is underlined. (B) Transcriptional activities of the PLAU and IFNT reporters by cotransfected ETS2 and HRAS expression plasmids (alone or in combination) into 3T3 cells. A & B are modified from (Ezashi and Roberts 2004). (C) The 6 bp and 22 bp sequences of ETS binding site of ovine IFNT-o10 (ovIFNT-o10) used in a study of (Matsuda-Minehata, et al. 2005). The nonfunctional 6 bp contains only the core of ETS binding site. The functional 22 bp has both ETS (blue) and adjacent AP1 binding site (orange).

ETS2 is a master regulator of trophoblast differentiation across species. In the mouse, Ets2 is essential for trophoblast development (Georgiades and Rossant 2006, Yamamoto, et al. 1998) and trophoblast stem (TS) cell self-renewal (Odiatis and Georgiades 2010, Wen, et al. 2007). The ETS2 transcription factor controls many trophoblast signature genes including Cdx2 (Wen, et al. 2007) and Hand1 (Odiatis and Georgiades 2010) in mice, CGA (Ghosh, et al. 2005) and CGB5 (Ghosh, et al. 2003, Johnson and Jameson 2000) in humans, and pregnancy-associated glycoprotein 2 (PAG2) (Szafranska, et al. 2001) and trophoblast Kunitz domain protein-1 (TKDP1) (Chakrabarty and Roberts 2007) in ruminants. Secretion of PAG2 and TKDP1 begins concurrently with IFNT in ruminant trophectoderm (Green JA, et al. 1998, MacLean, et al. 2003).

The success obtained with yeast one-hybrid screening to identify ETS2 as a factor that associated with the proximal region of the IFNT 5/UTR was not so fruitful when applied to search the distal region (−358 to −322 bp) for binding factors. Various gene products with generally weak interactions were initially identified, but after several rounds of the one-hybrid screening with different background threshold level, no consistent and plausible candidates for binding factors were found (Ezashi et al., unpublished observation).

Although bovine and ovine IFNT genes have relatively conserved 5/UTR to around −400 bp, their nucleotide sequences diverge considerably beyond that point (Ealy, et al. 2001), suggesting that if control elements do exist they may be gene specific. In the ovine IFNT gene (ovIFNT-o10), a JUN/FOS (AP1) site was identified within the −654 to −555 bp region and appeared to have a regulatory function (Yamaguchi et al., 1999). It formed a DNA-protein complex with nuclear extracts of JEG3 choriocarcinoma cells and mediated responses to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) treatment by an ovine IFNT-SV40 hybrid reporter (Yamaguchi, et al. 2001). This site appears to be involved with a coactivator, cAMP-response element binding protein-binding protein (CREBBP) (Xu, et al. 2003). However, different responses to the AP1 site mutations at −602 to −592 in the two bovine IFNT genes, IFNT1 and IFNT-c1 that appears to be homologous to the AP1 site in the ovine IFNT gene, were observed. In the latter gene, the AP1 mutation did not change the transcriptional activity (Sakurai, et al. 2013b).

Closely juxtaposed ETS- and AP1-binding motifs in plasminogen activator urokinase (PLAU) and chorionic somatomammotropin hormone (CSH2) genes serve as a target of the RAS-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway (Stacey, et al. 1995, Sun and Duckworth 1999) (Fig 1A, 1B). Signaling through this pathway leads to phosphorylation of a highly conserved threonine residue in ETS2 at threonine 72 (T72) and stimulates ETS2-driven transcriptional responses (Yang, et al. 1996). The proximal regions of IFNT genes possess a similar consensus AP1 site at −71 adjacent to the ETS site (Fig. 1A, 1C, Fig. 2B and Fig. 3), which is also responsive to RAS-mediated signaling (Ezashi and Roberts 2004). In all respects, the ETS/AP1 binding motif in the IFNT behaved identically to the one in the murine PLAU gene (Fig. 1B). Mutating T72 to alanine (A72) of ETS2 and mutation of the AP1 site in the ETS/AP1 binding motif (μAP1, Fig. 2B) reversed the RAS effect on the IFNT promoter. This study also demonstrated the importance of the AP1 site adjacent to ETS2 at −71 relative to other potential AP1 binding sites in the −1675 bp region of 5/UTR control region, none of which were responsive to RAS-mediated signaling (Ezashi and Roberts 2004).

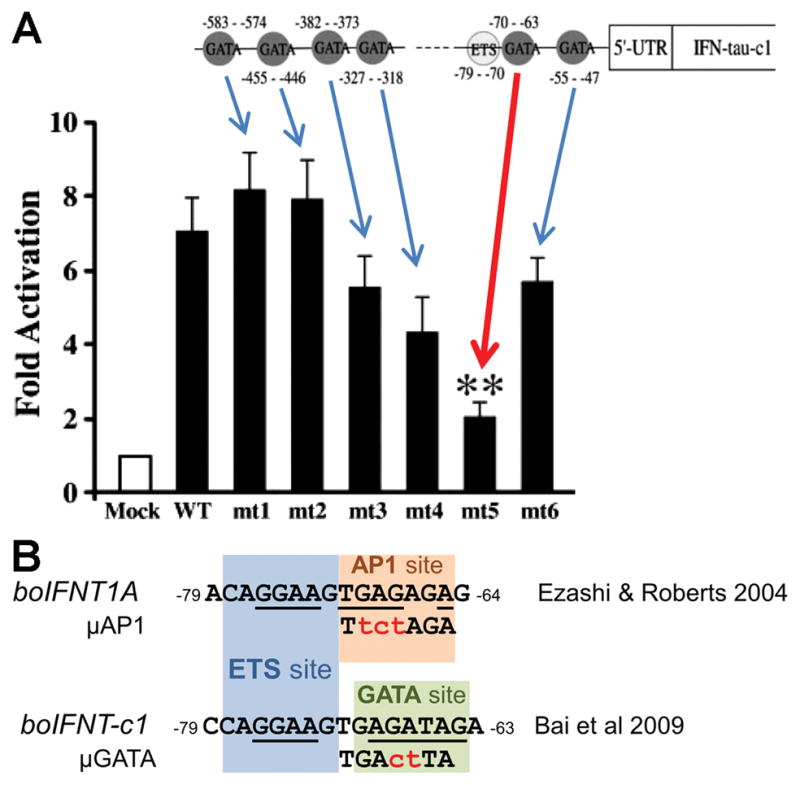

Fig. 2.

(A) ETS2 and potential six GATA binding sites in the regulatory region of the bovine IFNT gene. Below is the transcriptional activity of the GATA site mutated IFNT reporters (mt1 – mt6) with GATA2 expression plasmid. ‘Mock’ and ‘WT’ are readings of the wildtype −631 bp IFNT reporter construct without and with GATA2 expression plasmid, respectively. The reporter activities and the location of the six mutation sites are shown with arrows. Significant reduction (p < 0.01) of the transcriptional activity is noted with a red arrow and two asterisks on the mutation site, −70 to −63 (mt5). The image has been modified from (Bai, et al. 2009). (B) The bovine IFNT upstream region adjacent to the ETS binding site (−79 to −70, blue) is shown as AP1 site (−71 to −65, orange) in (Ezashi and Roberts 2004) or GATA site (−70 to −63, green, mt5 site in A) in (Bai, et al. 2009). Conserved core binding sequences are underlined. Introduced mutation sequences are shown in red.

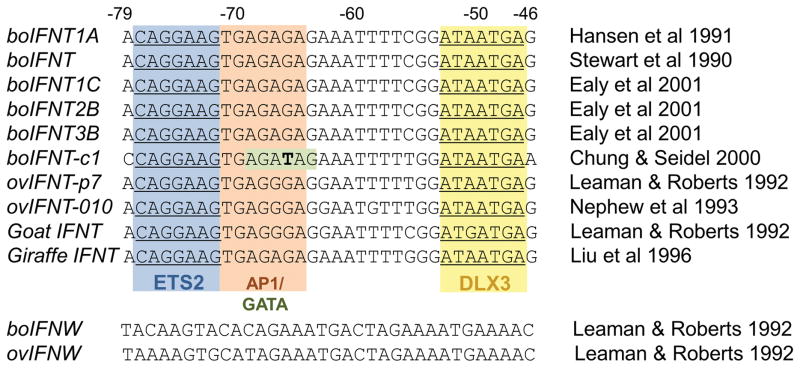

Fig. 3.

Sequence alignment of upstream regulatory regions (−79 to −46) of IFNT and IFNW genes from various species, including bovine (bo) and ovine (ov). The IFNT sequences contained a conserved ETS2 binding site (blue), putative AP1 binding site (orange) or GATA binding site (green) and DLX3 binding site (yellow). The corresponding regions of IFNW genes do not contain such sequence motifs. The references for the sequences are boIFNT1A (Hansen, et al. 1991); boIFNT (Stewart, et al. 1990); boIFNT1C, -2B and -3B (Ealy, et al. 2001); ovIFNT-p7, goat IFNT, boIFNW and ovIFNW (Leaman and Roberts 1992); ovIFNT-o10 (Nephew, et al. 1993); and giraffe IFNT (Liu, et al. 1996). The boIFNT-c1 sequence is direct submission to GenBank (AF238613) by Chung and Seidel in 2000. A thymine (T) at −66 (bold letter) is unique to the boIFNT-c1 gene that makes a putative GATA binding site but the base is not conserved in other IFNT genes.

DLX3

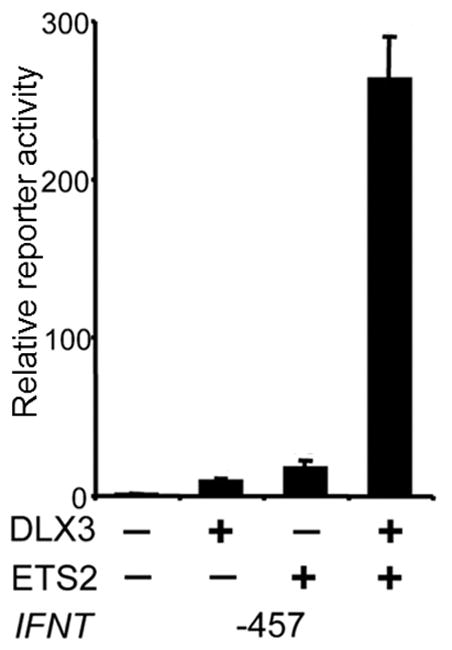

Having shown that ETS2 was a major player in controlling IFNT expression, it was natural to examine other important transcription factors that had been implicated in trophoblast differentiation in the human and mouse. DLX3 is a member of the distal-less family of non-Antennapedia homeobox genes. Its knock out in mouse embryos leads to embryonic death due to placental failure by about d 10 of pregnancy (Morasso, et al. 1999). DLX3 is also expressed in human, cow and mouse trophoblast cells (Ezashi, et al. 2008, Panganiban and Rubenstein 2002). It is upregulated during formation of human syncytiotrophoblast (Yabe, et al. 2016) and has a role in the control of human CGA (Roberson, et al. 2001), placental growth factor (PGF) (Li and Roberson 2017a) and murine 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase VI (Hsd3b6) expressions (Berghorn, et al. 2005, Peng and Payne 2002). The DLX3 binding site (−54 GATAATGAG −46) which lies between the ETS2 binding site and the transcription start site of IFNT 5/UTR is conserved in all IFNT genes examined (Fig. 3). Overexpression of DLX3 in JAr cells transactivated the bovine IFNT1A 10 to 20-fold, whereas mutations introduced into the DLX3 binding site at −54 to −46 abolished the activation effect (Ezashi, et al. 2008). In combination with ETS2 overexpression, DLX3 increased the IFNT reporter activity more than 250-fold (Fig. 4). However, if the ETS2 binding site (−79 to −70) was mutated (μETS2) or deleted, the effects of DLX3 on reporter gene transactivation were abolished, suggesting that a major portion of DLX3 transactivation activity was dependent on presence of ETS2 at a site just two helical turns (~20 bp) upstream of the DLX3 site (Fig. 3). Suppression of bovine DLX3 expression by siRNA led to reductions of both intracellular IFNT protein and antiviral activity released into the medium of bovine trophectoderm CT-1 cell culture. Moreover, the two transcription factors (ETS2 and DLX3) were co-immunoprecipitated together as a complex in the IFNT-expressing CT-1 cell line. Clearly, DLX3 partners ETS2 in a cooperative and dependent manner to regulate IFNT expression in trophectoderm (Ezashi, et al. 2008). DLX3 also interacts with another transcription factor, GCM1, to regulate PGF expression in human trophoblasts (Li and Roberson 2017a, b).

Fig. 4.

Cooperation of ETS2 and DLX3 in the transactivation of IFNT. The −457 boIFNT1A construct was transfected into choriocarcinoma JAr cells in either the absence (−) or presence (+) of the DLX3 or ETS2 expression plasmids. Values on Y-axis reprxesent fold activations with the basal activity of the −457 reporter set as 1. Obtained from (Ezashi, et al. 2008).

GATA2 and GATA3

In the mouse placenta, Dlx3 expression is controlled by GATA2 and −3 transcription factors (Home, et al. 2017). These transcription factors are also regulators of mouse trophoblast differentiation (Home, et al. 2009, Ralston, et al. 2010, Ray, et al. 2009). They are expressed in the bovine CT-1 cell line and in day 15–21 bovine and ovine conceptuses (Bai, et al. 2014, Bai, et al. 2009). GATA2 but not GATA3 overexpression also appeared capable of increasing expression from an IFNT reporter in non-trophoblast cells, namely bovine ear derived fibroblasts (Bai, et al. 2009). Similar experiments in JEG3 cells failed to reproduce the effect, possibly because JEG3 cells already express endogenous GATA2 or -3 in abundant quantities. This inference may be correct as siRNA silencing of GATA2 did decrease IFNT-c1-reporter expression (Bai, et al. 2009). A search of six possible GATA sites as possible control elements for IFNT transcription identified only one (−70 to −63; Fig. 2A, red arrow) that, when mutated, reduced IFNT expression to that of mock-transfected cells. Interestingly, the −70 to −63 site overlaps the previously reported AP1 site (−71 to −64) adjacent to the ETS2 binding site at −79 to −70 (Ezashi and Roberts 2004) (Fig. 2B). However, the generality of these data implicating GATA2 and GATA3 in control of IFNT expression should be treated with caution. First, the positive effects of GATA2 were only noted in a non-trophoblast cell line. Second, of all the ovine and bovine genes studied only bovine IFNT-c1 has the unique thymine (T) at −66 instead of the common guanine (G) present in other IFNT genes (Fig. 3). Finally, an introduced GATA site mutation also disturbs the AP1 binding site sequence (Fig. 2B). Clearly, further studies are needed to address whether GATA factors directly interact with the IFNT regulatory regions or even modulate IFNT promoter activity in trophoblast. Another possibility is that they act indirectly through other GATA2 and −3 regulated genes, such as DLX3 (Home, et al. 2017).

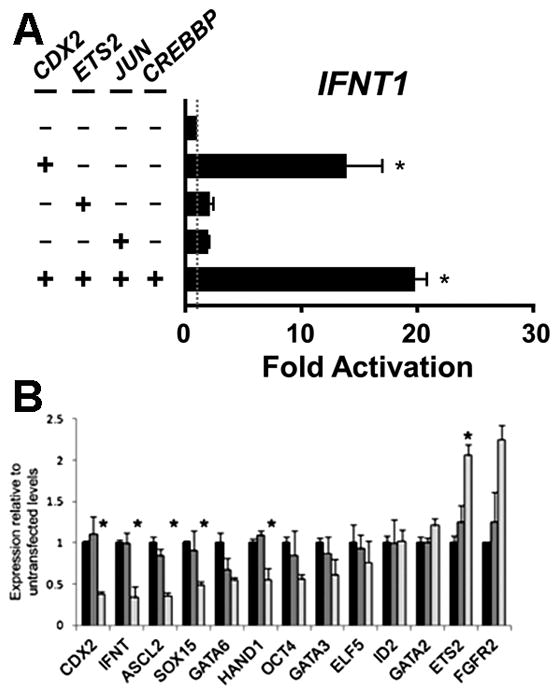

CDX2

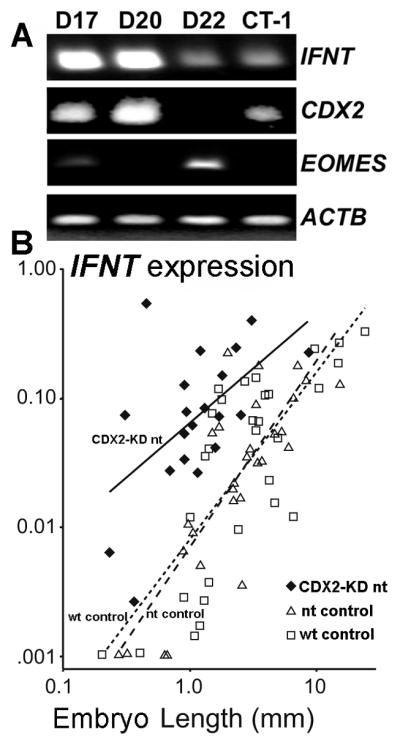

Caudal-type homeobox transcription factor CDX2, like ETS2, AP1, DLX3 and GATA2 & −3, plays an essential role in trophoblast lineage emergence and maintenance in the mouse and possibly other species (Ralston and Rossant 2008, Roberts and Fisher 2011, Strumpf, et al. 2005). When the relative expression of IFNT and CDX2 transcripts were compared in ovine (d 14–20) and bovine (d 17–22) conceptuses during the peri-implantation period, roughly similar expression patterns over time were observed (Sakurai, et al. 2013a, Sakurai, et al. 2010) (Fig 5A), suggesting a possible link between the two. Perhaps of note, ovine CDX2 expression became undetectable around day 20 at a time coincident with trophectoderm attachment to the uterine epithelium and ovine IFNT silencing (Ealy, et al. 2001, Helmer, et al. 1987). Some co-transfection experiments performed on human choriocarcinoma JEG3 cells have also suggested a possible role for CDX2 in the transactivation of IFNT genes (Imakawa, Kim et al. 2006). There is also an indication that CDX2 in combination with a number of other transcription factors, including ETS2 and AP1 might also be capable of up-regulating endogenous IFNT gene transcription in non-trophoblast bovine ear derived fibroblast cells, which do not normally express either IFNT or CDX2 (Fig. 6A) (Sakurai, et al. 2009)(Sakurai, et al. 2013b). Possibly CDX2 expression contributes to a partial trans-differentiation of the mesodermal fibroblast cells to trophoblast-like and a permissive environment for low levels of IFNT transcription.

Fig. 5.

(A) RT-PCR analysis of IFNT, CDX2 and EOMES expressions in bovine conceptus at days 17, 20 and 22 by (Sakurai, et al. 2013a). Amplicons from ACTB served as loading controls. (B) CDX2-knockdown (KD) bovine embryos were compared by IFNT expression (Y axis) and embryo size (X axis) to matched nuclear transfer (nt) and wild-type (wt) embryos by (Berg, et al. 2011). CDX2 expression was decreased by 72% in the KD embryos. Regression lines are solid for CDX2-KD nt, dashed for nt control and dotted for wt control embryos. Wt and nt generated control embryos expressed IFNT in proportion to their embryo size in length. Smaller sized CDX2-KD nt embryos expressed IFNT in amounts comparable to much larger WT embryos.

Fig. 6.

(A) Bovine IFNT1-reporter activity with CDX2, ETS2, JUN (AP1) and CREBBP expression plasmids. The plasmids were transfected in bovine ear-derived fibroblasts. Copied from (Sakurai, et al. 2013b). (B) 62% CDX2 reduction by siRNA in CT-1 cells reduces expressions of some genes including IFNT but increases ETS2. Copied from (Schiffmacher and Keefer 2013).

Some confusion exists as to the location of the site of CDX2 interaction with the 5/UTR of IFNT. One, apparently functional site, was reported between −581 to −575 bp in an ovine IFNT gene (Imakawa, et al. 2006). Later, potential CDX2 binding sites were noted in a more proximal site at −248 to −47 bp of boIFNT-c1 (Sakurai, et al. 2009) and between −414 to −235 bp in an ovine IFNT (Sakurai, et al. 2010). CDX2 knockdown in bovine trophectoderm BT-1 (Sakurai, et al. 2009) and CT-1 cells (Schiffmacher and Keefer 2013) (Fig 5B) has also implicated a role for CDX2 in controlling IFNT expression.

However, other investigators have presented contrasting interpretation on the effects of CDX2 knockdown. For example, no effect was noted in with d 7.5 bovine blastocysts (Goissis and Cibelli 2014). Essentially negative results were also reported with day 14 conceptuses (Berg, et al. 2011). For example, when CDX2-knockdown conceptuses were transferred to the uteri of synchronized recipient cows and recovered a week later, they were significantly shorter in the size than controls. However, these treated conceptuses expressed IFNT at levels equivalent to that of the control conceptuses (Fig. 5B). From these results, it would appear that CDX2 is required for trophoblast development but not for IFNT expression. Clearly further studies are required if this conundrum is to be solved.

Multiplicity of IFNT genes

Multiple IFNT genes exist in most ruminant species studied (Leaman and Roberts 1992). Those expressed in cattle have been categorized into three groups (Ealy, et al. 2001, Walker, et al. 2009) and it is clear that not all these genes are expressed equivalently in the same conceptus (Walker, et al. 2009) and that relative expression of each can change over development (Sakurai, et al. 2013b, Walker, et al. 2009). Yet most known IFNT genes have highly conserved sequences within the ETS2-AP1-DLX3 enhancer region (−79 to −46) (Fig. 3). The sequences in Fig. 3 do not include those of ovine IFNT that are poorly expressed and contain a mutation in the ETS binding site (Ezashi, et al. 1998, Leaman and Roberts 1992, Nephew, et al. 1993). All genes in the list contain the ETS2, the putative AP1, and the DLX3 binding sites. However, the presence of a GATA binding site is limited to the bovine IFNT-c1. Note also the lack of conservation in the corresponding region of IFNW. Little is known about the function of the latter, although more than 20 apparently functional IFNW are found in the bovine genome (Walker and Roberts 2009).

2-2. Mechanisms that up-regulate IFNT gene transcription following blastocyst formation

IFNT is not secreted by morula stage conceptuses and is only modestly produced at the d 8 blastocyst stage, but levels of its mRNA and total IFN production increases markedly as the conceptus begins to expand and then elongate (Ealy, et al. 2001, Farin, et al. 1990, Kubisch, et al. 1998). ETS2, the master regulator of IFNT transcription is expressed in trophoblasts of E5.0 stage mouse embryos and is a necessary factor for placental development (Georgiades and Rossant 2006, Yamamoto, et al. 1998), trophoblast stem cell (Kubaczka, et al. 2015, Wen, et al. 2007) and transcription of key placental hormones (Das, et al. 2008, Ghosh, et al. 2003, Ghosh, et al. 2005). The initial low IFNT expression per cell in blastocyst stage ovine and bovine conceptuses has been speculated to be due to suppression by persistence of the POU domain class 5 transcription factor 1 (POU5F1 often known as OCT4) (Ezashi, et al. 2001) that is expressed in early ruminant and primate trophectoderm (Niakan and Eggan 2013, Van Eijk, et al. 1999) (Fig. 7). Both CGA and CGB were efficiently silenced by overexpressing POU5F1 in choriocarcinoma cells (Liu, et al. 1997, Liu and Roberts 1996). We initially proposed that POU5F1 silenced IFNT by quenching, i.e., the silencer (= POU5F1 in this case) interferes with the ability of the DNA-bound transactivator (= ETS2) to interact with the basal transcriptional machinery (Ezashi, et al. 2001). However, a more recent study of CGA silencing (Gupta, et al. 2012) demonstrated a squelching mechanism, i.e., POU5F1 sequesters free ETS2 and prevents ETS2 from binding to the DNA. It can be speculated that this mechanism also operates for IFNT (Fig. 7). As trophoblast differentiation proceeds, POU5F1 becomes reduced in amount, and other trophoblastic gene regulators such as DLX3, CDX2, and GATA2/3 become up-regulated. However, there are some conflicting observations that counter this hypothesis. When, for example, POU5F1 was over-expressed in CT-1 cells, IFNT expression appeared not to be suppressed (Schiffmacher and Keefer 2013). In that experiment, overexpressed POU5F1 only changed ASCL2 expression among the cohort of genes examined. Because so few changes in trophoblast gene expression were observed when >60% of POU5F1 transcripts had been knocked down, it remains unclear whether the expressed POU5F1 levels play a role in the gene regulatory network of CT-1 cells.

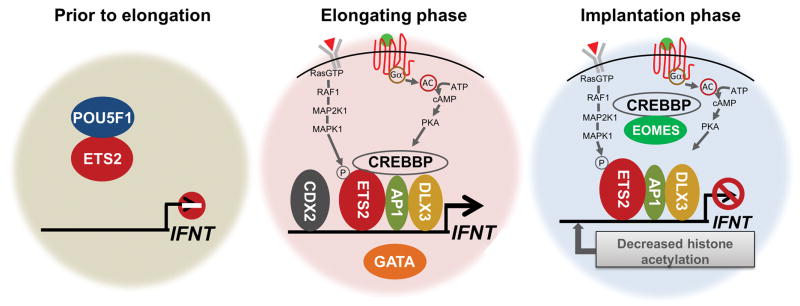

Fig. 7.

Summary of speculative models for IFNT transcriptional control at prior to conceptus elongation (left), elongation phase (middle) and implantation (right). Before conceptus elongation, presence of POU5F1 in the early stage trophectoderm suppresses IFNT expression through squelching ETS2. When the conceptus elongates, trophoblastic gene regulators DLX3, CDX2, and GATA2/3 become up-regulated. Growth factors released from maternal endometrium activate MEK/ERK and PKA signaling pathways and increase IFNT expression through the transcription factors. When the trophectoderm firmly attaches to the uterine epithelium in the implantation stage, the IFNT expression is down-regulated. The silencing is accompanied by EOMES association with CREBBP co-activator and reduction of histone acetylation of the IFNT gene upstream region.

2-3. Regulatory mechanisms that down-regulate IFNT gene transcription

Following the dramatic, short-term increase IFNT transcription during the elongation phase of development, the expression of these genes is rapidly down-regulated when the trophectoderm attaches to the uterine epithelium (Ealy, et al. 2001, Helmer, et al. 1987). Precisely what mediates these events is unclear. However, down-regulation of in vivo IFNT gene could be mimicked in CT-1 cells when the cells were cultured with bovine uterine epithelium cells (Sakurai, et al. 2013a). The transcription factor T-box protein eomesodermin (EOMES) has been implicated in this silencing phenomenon, in part because its expression increases in trophectoderm following the conceptus attachment (Fig. 5A) (Sakurai, et al. 2013a). One explanation is that EOMES associates with the co-activator CREBBP and reduces its binding to AP1 (Xu, et al. 2003), thereby disrupting transactivation of IFNT by ETS2/AP1 (Sakurai, et al. 2013a) (Fig. 7). There also suggestions that the relocation of TEAD2/4 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm leads to down-regulation of IFNT expression (Kusama, et al. 2016), but this observation needs to be confirmed in future studies.

3. Epigenetic regulation

There is some limited evidence that epigenetic as well as genetic mechanisms might regulate IFNT expression. For example, endogenous IFNT expression was increased in bovine skin fibroblasts when CDX2 was over-expressed and the cultures treated with a histone deacetylase inhibitor (Sakurai, et al. 2010). Further evidence came from chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays performed on elongating ovine conceptuses (days 14, 16, 16.5 and 20) to determine the acetylation status of histone H3 at the lysine-18 residue (H3K18) (Sakurai, et al. 2010). Elevated H3K18 acetylation of the ovine IFNT gene was observed on days 14 and 16 but declined when the conceptus had initiated attachment to the uterine wall (Fig. 7). The authors also inferred H3K18 association with the −414 to −235 bp of the 5/UTR and the CDX2 binding sites (−300 to −294 bp and −293 to −287 bp) within the ovine gene (Sakurai, et al. 2010). In addition, CDX2 overexpression in bovine ear-derived fibroblast cells increased histone acetylation and led to concurrent recruitment of CREBBP, a nuclear factor that has histone acetyltransferase activity. Acetylation of H3K18 was also detected in the proximity of the CDX2 binding region of a bovine IFNT gene in IFNT-secreting CT-1 cells. Conversely, when CDX2 expression was inhibited by a small interfering RNA, H3K18 acetylation was decreased (Sakurai, et al. 2010). These findings suggest that CDX2 regulates IFNT expression through CREBBP recruitment, which leads to greater H3K18 acetylation at CDX2 binding sites.

4. Maternal factors and intracellular signaling that control IFNT expression

Secretions from maternal endometrial glands including hormones and growth factors may play a promotive role for both induction of IFNT expression and conceptus growth (Gray, et al. 2002, Roberts, et al. 2008, Satterfield, et al. 2006). For example, IFNT production from cultured blastocyst can be increased by supplementation of the medium with uterine flushing (Kubisch, et al. 2001), which are known to contain colony stimulating factor 2 (CSF2 also known as GM-CSF) (Imakawa, et al. 1993), interleukin 3 (IL3) (Imakawa, et al. 1995) and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2) (Michael, et al. 2006, Ocon-Grove, et al. 2008, Rodina, et al. 2008). Each of these cytokines can individually increase transcription from IFNT, presumably through cell signaling pathways initiated by the cognitive receptor complexes. For example, CSF1, which is also present in uterine secretions, and its cognate receptor CSF1R (c-fms), expressed in the bovine trophoblast, can both exert MEK/ERK pathway transduction and increase IFNT expression (Ezashi and Roberts 2004) (Fig. 7). Additionally, over-expression of the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A (PKA) in combination with ETS2 overexpression induced a 500-fold up-regulation of IFNT (Das, et al. 2008). Presumably, growth factors released from maternal endometrium in combination with PKA, MEK/ERK, and PKC signaling pathways and a combination of necessary transcription factors can provide the massive up-regulation of IFNT observed in the elongating conceptus (Fig. 7).

5. Conclusion

The IFNT genes diverged from those encoding its closest Type I IFN family, IFNW, about 36 million years ago when the ruminant species started to emerge within the artiodactyl order (Roberts, et al. 1997) and was probably initiated when a progenitor IFNW gene exchanged in some manner its viral response elements for ones that favored trophoblast expression. The acquired transcriptional control elements drive IFNT expression in trophoblast, which is then sustained over several days without viral infection (Roberts, et al. 2008). The studies on IFNT gene regulation first focused on what regions of the gene were responsible for trophoblast expression and what transcription factors were involved. Later studies emphasized the role of external factors and signaling pathways, and why the high-level expression became silenced after only a few days. More recently emphasis has switched to epigenetic regulation. In particular, it was noted that that many of the transcription factors that regulate trophoblast emergence and development elucidated in mouse studies play a role in trophoblast-specific IFNT gene expression. The studies confirm that there is a core group of transcription factors that probably operate across all mammals to initiate trophoblast emergence. However, these same factors may also guide unique aspects of the trophoblast phenotype, such as production of hormones and other signature events that are peculiar to a particular taxonomic group. Representative findings of IFNT gene control are summarized in three stages of conceptus development (Fig. 7). Modest IFNT expression in early trophectoderm prior to conceptus elongation can be explained by a presence of POU5F1 which suppresses ETS2 transactivation. Species specific onset patterns of trophoblastic gene expression, including IFNT, might be linked to a time length of persisted POU5F1 protein in trophoblasts that is very limited in rodents. Large increases of IFNT expression in the elongation phase appears to be combinatory by up-regulated trophoblastic gene regulators (DLX3, CDX2, GATA2/3) and growth factors released from maternal endometrium that activate MEK/ERK and PKA signaling pathways in trophoblasts. The down-regulation mechanism of IFNT expression at implantation phase has been anticipated by decreased histone acetylation of the regulatory region of IFNT gene and the association of EOMES and CREBBP that lead to disruption of a transactivation complex of IFNT gene.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Health HD21896, HD42201 to R.M. Roberts, HD77108 to T.E., Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (14206032, 18108004, 16H02584) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Bioscience (BRAIN, H20) and the Science and Technology Research Promotion Program (25030AB) for Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF), Japan to K.I.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- Bai H, Sakurai T, Bai R, Godkin JD, Imakawa K. Localization of GATA2 in the nuclear and cytoplasmic regions of ovine conceptuses. Anim Sci J. 2014;85:981–985. doi: 10.1111/asj.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai H, Sakurai T, Kim MS, Muroi Y, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Nakajima H, Takahashi M, Nagaoka K, Imakawa K. Involvement of GATA transcription factors in the regulation of endogenous bovine interferon-tau gene transcription. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:1143–1152. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg DK, Smith CS, Pearton DJ, Wells DN, Broadhurst R, Donnison M, Pfeffer PL. Trophectoderm lineage determination in cattle. Dev Cell. 2011;20:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghorn KA, Clark PA, Encarnacion B, DeRegis CJ, Folger JK, Morasso MI, Soares MJ, Wolfe MW, Roberson MS. Developmental expression of the homeobox protein Distal-less 3 and its relationship to progesterone production in mouse placenta. J Endocrinol. 2005;186:315–323. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty A, Roberts MR. Ets-2 and C/EBP-beta are important mediators of ovine trophoblast Kunitz domain protein-1 gene expression in trophoblast. BMC Mol Biol. 2007;8:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JC, Roberts RM. Constitutive and trophoblast-specific expression of a class of bovine interferon genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:3817–3821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Ezashi T, Gupta R, Roberts RM. Combinatorial roles of protein kinase A, Ets2, and 3′,5′-cyclic-adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein-binding protein/p300 in the transcriptional control of interferon-tau expression in a trophoblast cell line. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:331–343. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ealy AD, Larson SF, Liu L, Alexenko AP, Winkelman GL, Kubisch HM, Bixby JA, Roberts RM. Polymorphic forms of expressed bovine interferon-tau genes: relative transcript abundance during early placental development, promoter sequences of genes and biological activity of protein products. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2906–2915. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ealy AD, Yang QE. Control of interferon-tau expression during early pregnancy in ruminants. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2009;61:95–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ealy AD, Woolridge D. The evolution of IFNT. Reproduction. 2017;154 doi: 10.1530/REP-17-0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezashi T, Das P, Gupta R, Walker A, Roberts RM. The Role of Homeobox Protein Distal-Less 3 and Its Interaction with ETS2 in Regulating Bovine Interferon-Tau Gene Expression-Synergistic Transcriptional Activation with ETS2. Biol Reprod. 2008 doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezashi T, Ealy AD, Ostrowski MC, Roberts RM. Control of interferon-tau gene expression by Ets-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7882–7887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezashi T, Ghosh D, Roberts RM. Repression of Ets-2-induced transactivation of the tau interferon promoter by Oct-4. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7883–7891. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.7883-7891.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezashi T, Roberts RM. Regulation of interferon-tau (IFN-tau) gene promoters by growth factors that target the Ets-2 composite enhancer: a possible model for maternal control of IFN-tau production by the conceptus during early pregnancy. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4452–4460. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farin CE, Imakawa K, Hansen TR, McDonnell JJ, Murphy CN, Farin PW, Roberts RM. Expression of trophoblastic interferon genes in sheep and cattle. Biol Reprod. 1990;43:210–218. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint AP, Guesdon FM, Stewart HJ. Regulation of trophoblast interferon gene expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1994;100:93–95. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades P, Rossant J. Ets2 is necessary in trophoblast for normal embryonic anteroposterior axis development. Development. 2006;133:1059–1068. doi: 10.1242/dev.02277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D, Ezashi T, Ostrowski MC, Roberts RM. A Central Role for Ets-2 in the Transcriptional Regulation and Cyclic Adenosine 5′-Monophosphate Responsiveness of the Human Chorionic Gonadotropin-{beta} Subunit Gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:11–26. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D, Sachdev S, Hannink M, Roberts RM. Coordinate regulation of basal and cyclic 5′-adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-activated expression of human chorionic gonadotropin-alpha by Ets-2 and cAMP-responsive element binding protein. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1049–1066. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goissis MD, Cibelli JB. Functional characterization of CDX2 during bovine preimplantation development in vitro. Mol Reprod Dev. 2014;81:962–970. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray C, Burghardt R, Johnson G, Bazer F, Spencer T. Evidence that absence of endometrial gland secretions in uterine gland knockout ewes compromises conceptus survival and elongation. Reproduction. 2002;124:289–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JA, Xie S, RRM Pepsin-related molecules secreted by trophoblast. Review of Reproduction. 1998;3:62–69. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0030062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MP, Spate LD, Bixby JA, Ealy AD, Roberts RM. A comparison of the anti-luteolytic activities of recombinant ovine interferon-alpha and -tau in sheep. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:1087–1093. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Ezashi T, Roberts RM. Squelching of ETS2 Transactivation by POU5F1 Silences the Human Chorionic Gonadotropin CGA Subunit Gene in Human Choriocarcinoma and Embryonic Stem Cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2012 doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmer SD, Hansen PJ, Anthony RV, Thatcher WW, Bazer FW, Roberts RM. Identification of bovine trophoblast protein-1, a secretory protein immunologically related to ovine trophoblast protein-1. J Reprod Fertil. 1987;79:83–91. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0790083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Home P, Kumar RP, Ganguly A, Saha B, Milano-Foster J, Bhattacharya B, Ray S, Gunewardena S, Paul A, Camper SA, Fields PE, Paul S. Genetic redundancy of GATA factors in the extraembryonic trophoblast lineage ensures the progression of preimplantation and postimplantation mammalian development. Development. 2017;144:876–888. doi: 10.1242/dev.145318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Home P, Ray S, Dutta D, Bronshteyn I, Larson M, Paul S. GATA3 is selectively expressed in the trophectoderm of peri-implantation embryo and directly regulates Cdx2 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28729–28737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imakawa K, Helmer SD, Nephew KP, Meka CS, Christenson RK. A novel role for GM-CSF: enhancement of pregnancy specific interferon production, ovine trophoblast protein-1. Endocrinology. 1993;132:1869–1871. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.4.7681767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imakawa K, Kim MS, Matsuda-Minehata F, Ishida S, Iizuka M, Suzuki M, Chang KT, Echternkamp SE, Christenson RK. Regulation of the ovine interferon-tau gene by a blastocyst-specific transcription factor, Cdx2. Mol Reprod Dev. 2006;73:559–567. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imakawa K, Tamura K, McGuire WJ, Khan S, Harbison LA, Stanga JP, Helmer SD, Christenson RK. Effect of interleukin-3 on ovine trophoblast interferon during early conceptus development. Endocrine. 1995;3:511–517. doi: 10.1007/BF02738826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Jameson JL. Role of Ets2 in cyclic AMP regulation of the human chorionic gonadotropin beta promoter. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;165:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubaczka C, Senner CE, Cierlitza M, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Kuckenberg P, Peitz M, Hemberger M, Schorle H. Direct Induction of Trophoblast Stem Cells from Murine Fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:557–568. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubisch HM, Larson MA, Kiesling DO. Control of interferon-tau secretion by in vitro-derived bovine blastocysts during extended culture and outgrowth formation. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;58:390–397. doi: 10.1002/1098-2795(20010401)58:4<390::AID-MRD6>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubisch HM, Larson MA, Roberts RM. Relationship between age of blastocyst formation and interferon-tau secretion by in vitro-derived bovine embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 1998;49:254–260. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199803)49:3<254::AID-MRD5>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusama K, Bai R, Sakurai T, Bai H, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Imakawa K. A transcriptional cofactor YAP regulates IFNT expression via transcription factor TEAD in bovine conceptuses. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2016;57:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaman DW, Cross JC, Roberts RM. Multiple regulatory elements are required to direct trophoblast interferon gene expression in choriocarcinoma cells and trophectoderm. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:456–468. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.4.8052267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaman DW, Roberts RM. Genes for the trophoblast interferons in sheep, goat, and musk ox and distribution of related genes among mammals. J Interferon Res. 1992;12:1–11. doi: 10.1089/jir.1992.12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Roberson MS. Dlx3 and GCM-1 functionally coordinate the regulation of placental growth factor in human trophoblast-derived cells. J Cell Physiol. 2017a;232:2900–2914. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Roberson MS. DLX3 interacts with GCM1 and inhibits its transactivation-stimulating activity in a homeodomain-dependent manner in human trophoblast-derived cells. Sci Rep. 2017b;7:2009. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02120-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Leaman D, Villalta M, Roberts RM. Silencing of the gene for the alpha-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin by the embryonic transcription factor Oct-3/4. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:1651–1658. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.11.9971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Leaman DW, Roberts RM. The interferon-tau genes of the giraffe, a nonbovid species. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1996;16:949–951. doi: 10.1089/jir.1996.16.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Roberts RM. Silencing of the gene for the beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin by the embryonic transcription factor Oct-3/4. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16683–16689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean JA, II, Chakrabarty A, Xie S, Bixby JA, Roberts RM, Green JA. Family of Kunitz proteins from trophoblast: expression of the trophoblast Kunitz domain proteins (TKDP) in cattle and sheep. Mol Reprod Dev. 2003;65:30–40. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda-Minehata F, Katsumura M, Kijima S, Christenson RK, Imakawa K. Different levels of ovine interferon-tau gene expressions are regulated through the short promoter region including Ets-2 binding site. Mol Reprod Dev. 2005;72:7–15. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael DD, Alvarez IM, Ocon OM, Powell AM, Talbot NC, Johnson SE, Ealy AD. Fibroblast growth factor-2 is expressed by the bovine uterus and stimulates interferon-tau production in bovine trophectoderm. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3571–3579. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasso MI, Grinberg A, Robinson G, Sargent TD, Mahon KA. Placental failure in mice lacking the homeobox gene Dlx3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:162–167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nephew KP, Whaley AE, Christenson RK, Imakawa K. Differential expression of distinct mRNAs for ovine trophoblast protein- 1 and related sheep type I interferons. Biol Reprod. 1993;48:768–778. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod48.4.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niakan KK, Eggan K. Analysis of human embryos from zygote to blastocyst reveals distinct gene expression patterns relative to the mouse. Dev Biol. 2013;375:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocon-Grove OM, Cooke FN, Alvarez IM, Johnson SE, Ott TL, Ealy AD. Ovine endometrial expression of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 2 and conceptus expression of FGF receptors during early pregnancy. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2008;34:135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odiatis C, Georgiades P. New insights for Ets2 function in trophoblast using lentivirus-mediated gene knockdown in trophoblast stem cells. Placenta. 2010;31:630–640. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panganiban G, Rubenstein JLR. Developmental functions of the Distal-less/Dlx homeobox genes. Development. 2002;129:4371–4386. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Payne AH. AP-2gamma and the Homeodomain Protein Distal-less 3 Are Required for Placental-specific Expression of the Murine 3beta -Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase VI Gene, Hsd3b6. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7945–7954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston A, Cox BJ, Nishioka N, Sasaki H, Chea E, Rugg-Gunn P, Guo G, Robson P, Draper JS, Rossant J. Gata3 regulates trophoblast development downstream of Tead4 and in parallel to Cdx2. Development. 2010;137:395–403. doi: 10.1242/dev.038828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston A, Rossant J. Cdx2 acts downstream of cell polarization to cell-autonomously promote trophectoderm fate in the early mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2008;313:614–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Dutta D, Rumi MA, Kent LN, Soares MJ, Paul S. Context-dependent function of regulatory elements and a switch in chromatin occupancy between GATA3 and GATA2 regulate Gata2 transcription during trophoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4978–4988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807329200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson MS, Meermann S, Morasso MI, Mulvaney-Musa JM, Zhang T. A role for the homeobox protein Distal-less 3 in the activation of the glycoprotein hormone alpha subunit gene in choriocarcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10016–10024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007481200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RM. Interferon-tau, a Type 1 interferon involved in maternal recognition of pregnancy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007;18:403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RM, Chen Y, Ezashi T, Walker AM. Interferons and the maternal-conceptus dialog in mammals. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RM, Cross JC, Leaman DW. Interferons as hormones of pregnancy. Endocr Rev. 1992;13:432–452. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-3-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RM, Fisher SJ. Trophoblast Stem Cells. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:412–421. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RM, Liu L, Alexenko A. New and atypical families of type I interferons in mammals: comparative functions, structures, and evolutionary relationships. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1997;56:287–325. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodina TM, Cooke FN, Hansen PJ, Ealy AD. Oxygen tension and medium type actions on blastocyst development and interferon-tau secretion in cattle. Anim Reprod Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Bai H, Bai R, Sato D, Arai M, Okuda K, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Godkin JD, Imakawa K. Down-regulation of interferon tau gene transcription with a transcription factor, EOMES. Mol Reprod Dev. 2013a;80:371–383. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Bai H, Konno T, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Godkin JD, Imakawa K. Function of a Transcription Factor CDX2 Beyond Its Trophectoderm Lineage Specification. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5873–5881. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Nakagawa S, Kim MS, Bai H, Bai R, Li J, Min KS, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Imakawa K. Transcriptional regulation of two conceptus interferon tau genes expressed in Japanese black cattle during peri-implantation period. PLoS One. 2013b;8:e80427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Sakamoto A, Muroi Y, Bai H, Nagaoka K, Tamura K, Takahashi T, Hashizume K, Sakatani M, Takahashi M, Godkin JD, Imakawa K. Induction of endogenous interferon tau gene transcription by CDX2 and high acetylation in bovine nontrophoblast cells. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:1223–1231. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield MC, Bazer FW, Spencer TE. Progesterone regulation of preimplantation conceptus growth and galectin 15 (LGALS15) in the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:289–296. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.052944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffmacher AT, Keefer CL. CDX2 regulates multiple trophoblast genes in bovine trophectoderm CT-1 cells. Mol Reprod Dev. 2013;80:826–839. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey KJ, Fowles LF, Colman MS, Ostrowski MC, Hume DA. Regulation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator gene transcription by macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3430–3441. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strumpf D, Mao CA, Yamanaka Y, Ralston A, Chawengsaksophak K, Beck F, Rossant J. Cdx2 is required for correct cell fate specification and differentiation of trophectoderm in the mouse blastocyst. Development. 2005;132:2093–2102. doi: 10.1242/dev.01801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Duckworth ML. Identification of a placental-specific enhancer in the rat placental lactogen II gene that contains binding sites for members of the Ets and AP-1 (activator protein 1) families of transcription factors. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:385–399. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.3.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szafranska B, Miura R, Ghosh D, Ezashi T, Xie S, Roberts RM, Green JA. Gene for porcine pregnancy-associated glycoprotein 2 (poPAG2): its structural organization and analysis of its promoter. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;60:137–146. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eijk MJ, Van Rooijen MA, Modina S, Scesi L, Folkers G, van Tol HT, Bevers MM, Fisher SR, Lewin HA, Rakacolli D, Galli C, de Vaureix C, Trounson AO, Mummery CL, Gandolfi F. Molecular cloning, genetic mapping, and developmental expression of bovine POU5F1. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:1093–1103. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.5.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AM, Kimura K, Roberts RM. Expression of bovine interferon-tau variants according to sex and age of conceptuses. Theriogenology. 2009;72:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AM, Roberts RM. Characterization of the bovine type I IFN locus: rearrangements, expansions, and novel subfamilies. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen F, Tynan JA, Cecena G, Williams R, Munera J, Mavrothalassitis G, Oshima RG. Ets2 is required for trophoblast stem cell self-renewal. Dev Biol. 2007;312:284–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu N, Takahashi Y, Matsuda F, Sakai S, Christenson RK, Imakawa K. Coactivator CBP in the regulation of conceptus IFNtau gene transcription. Mol Reprod Dev. 2003;65:23–29. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabe S, Alexenko AP, Amita M, Yang Y, Schust DJ, Sadovsky Y, Ezashi T, Roberts RM. Comparison of syncytiotrophoblast generated from human embryonic stem cells and from term placentas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E2598–2607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601630113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Nagaoka K, Imakawa K, Sakai S, Christenson RK. Enhancer regions of ovine interferon-tau gene that confer PMA response or cell type specific transcription. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;173:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Flannery ML, Kupriyanov S, Pearce J, McKercher SR, Henkel GW, Maki RA, Werb Z, Oshima RG. Defective trophoblast function in mice with a targeted mutation of Ets2. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1315–1326. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang BS, Hauser CA, Henkel G, Colman MS, Van Beveren C, Stacey KJ, Hume DA, Maki RA, Ostrowski MC. Ras-mediated phosphorylation of a conserved threonine residue enhances the transactivation activities of c-Ets1 and c-Ets2. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:538–547. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.2.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References for figure legends

- Bai H, Sakurai T, Kim MS, Muroi Y, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Nakajima H, Takahashi M, Nagaoka K, Imakawa K. Involvement of GATA transcription factors in the regulation of endogenous bovine interferon-tau gene transcription. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:1143–1152. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg DK, Smith CS, Pearton DJ, Wells DN, Broadhurst R, Donnison M, Pfeffer PL. Trophectoderm lineage determination in cattle. Dev Cell. 2011;20:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ealy AD, Larson SF, Liu L, Alexenko AP, Winkelman GL, Kubisch HM, Bixby JA, Roberts RM. Polymorphic forms of expressed bovine interferon-tau genes: relative transcript abundance during early placental development, promoter sequences of genes and biological activity of protein products. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2906–2915. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezashi T, Das P, Gupta R, Walker A, Roberts RM. The Role of Homeobox Protein Distal-Less 3 and Its Interaction with ETS2 in Regulating Bovine Interferon-Tau Gene Expression-Synergistic Transcriptional Activation with ETS2. Biol Reprod. 2008 doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezashi T, Roberts RM. Regulation of interferon-tau (IFN-tau) gene promoters by growth factors that target the Ets-2 composite enhancer: a possible model for maternal control of IFN-tau production by the conceptus during early pregnancy. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4452–4460. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen TR, Leaman DW, Cross JC, Mathialagan N, Bixby JA, Roberts RM. The genes for the trophoblast interferons and the related interferon-alpha II possess distinct 5′-promoter and 3′-flanking sequences. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3060–3067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaman DW, Roberts RM. Genes for the trophoblast interferons in sheep, goat, and musk ox and distribution of related genes among mammals. J Interferon Res. 1992;12:1–11. doi: 10.1089/jir.1992.12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Leaman DW, Roberts RM. The interferon-tau genes of the giraffe, a nonbovid species. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1996;16:949–951. doi: 10.1089/jir.1996.16.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda-Minehata F, Katsumura M, Kijima S, Christenson RK, Imakawa K. Different levels of ovine interferon-tau gene expressions are regulated through the short promoter region including Ets-2 binding site. Mol Reprod Dev. 2005;72:7–15. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nephew KP, Whaley AE, Christenson RK, Imakawa K. Differential expression of distinct mRNAs for ovine trophoblast protein- 1 and related sheep type I interferons. Biol Reprod. 1993;48:768–778. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod48.4.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Bai H, Bai R, Sato D, Arai M, Okuda K, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Godkin JD, Imakawa K. Down-regulation of interferon tau gene transcription with a transcription factor, EOMES. Mol Reprod Dev. 2013a;80:371–383. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Nakagawa S, Kim MS, Bai H, Bai R, Li J, Min KS, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Imakawa K. Transcriptional regulation of two conceptus interferon tau genes expressed in Japanese black cattle during peri-implantation period. PLoS One. 2013b;8:e80427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffmacher AT, Keefer CL. CDX2 regulates multiple trophoblast genes in bovine trophectoderm CT-1 cells. Mol Reprod Dev. 2013;80:826–839. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart HJ, McCann SH, Flint AP. Structure of an interferon-alpha 2 gene expressed in the bovine conceptus early in gestation. J Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:275–282. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0040275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]