ABSTRACT

Dysregulation of miR-203 by promoter methylation is associated with the development of various cancers. We aimed to explore the underlying link between promoter methylation and miR-203 expression in Kazakh esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). MassARRAY® System spectrometry was used to quantitatively analyze the DNA methylation of 32 CpG sites within miR-203 in 99 Kazakh ESCC and 46 normal esophageal tissues (NETs) with similar population characteristics. We conducted real-time PCR to detect miR-203 expression levels and evaluated their association with methylation. Eleven CpG units within miR-203 promoter were frequently hypermethylated in ESCC compared with NETs (P < 0.05). The hypermethylation of several CpG units positively correlated with age, lower esophagus, constrictive type of ESCC, and moderately differentiated ESCC. Given the involvement of human papillomavirus (HPV) in etiology of ESCC was confirmed from our previous reports, herein we found that CpG units within miR-203 in HPV16-positive ESCC are more heavily methylated. Furthermore, miR-203 expression showed a nearly 4.5-fold decrease in ESCC than NETs (0.206 ± 0.336 vs. 0.908 ± 1.424, P < 0.001) and was significantly associated with lymph node metastasis (P = 0.012). The expression of miR-203 with 11 completely hypermethylated CpG units was approximately 6.5-fold lower than that with at least 1 unmethylated CpG unit (P < 0.001) and especially the CpG_15.16 and CpG_31.32 with higher methylation levels in ESCC tissues exhibited lower expression levels of miR-203, which indicated a reverse association between miR-203 methylation and expression. Hypermethylated miR-203 is a potential biomarker and targeted delivery of miR-203 could therefore serve as a preventive or therapeutic strategy for Kazakh ESCC.

KEYWORDS: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, Kazakh, miR-203, methylation

Abbreviations

- ESCC

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- NETs

normal esophageal tissues

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- CpG

CG dinucleotides

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer worldwide and the sixth most common cause of death from cancer.1 Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is a common type of esophageal cancer in developing countries, such as China.2 Compared with other ethnic populations residing in Xinjiang, China, Kazakhs are more susceptible to ESCC. This population has a high incidence and mortality of ESCC familial aggregation, rendering ESCC a major cause of cancer-related deaths.3 Epidemiological and etiological studies showed that environmental and genetic factors greatly contribute to esophageal carcinogenesis.4 DNA methylation is a main pattern of epigenetic modification. Inordinately aberrant methylation of DNA can be observed in various tumor tissues. This event is usually characterized by low methylation at the whole-genome level and high methylation in a specific gene promoter region.5 Highly methylated CpG islands of a DNA promoter could restrain the relevant transcription of target genes, especially antioncogenes. Importantly, early diagnosis is critical for the effective treatment of ESCC. Abnormal methylation of DNA can be used to detect and diagnose ESCC.6 Exposing the molecular pathogenesis of Kazakh ESCC, especially discovering the abnormal CpG methylation, is important to develop new approaches to prevent, diagnose, and treat ESCC.

microRNAs (miRNAs), approximately 22 nt noncoding RNAs coded by endogenous genes, can posttranscriptionally regulate gene expression mainly by binding to the 3′-UTR of protein-coding transcripts.7 In recent years, an increasing number of miRNAs involved in essential tumor cell biologic processes, such as proliferation, invasion, and apoptosis, have been identified.8 Recent studies of the relationship between miRNA methylation and tumorigenesis reported that high miRNA methylation is one mechanism to silence miRNA expression.9 As a result, methylated CpG sites within CpG islands in the promoter lead to abnormal target gene expression. We previously observed that miR-34a hypermethylation downregulates miR-34a expression in Kazakh ESCC.10 miR-203, a miRNA located in chromosome 14q32.33, is reportedly a tumor suppressor gene.11 The expression of miR-203 varies in different tumor types; for instance, it is downregulated in haematopoietic tumors12 and ESCC13 but upregulated in breast cancer.14 Growing evidence supports that the downregulation of miR-203 by promoter hypermethylation is linked to the development of tumors, such as haematopoietic tumors,12 hepatocellular carcinoma,7 bladder cancer,15 endometrial cancer,16 cervical cancer,17 larynx and hypopharynx carcinoma,18 and esophageal cancer.19 However, Chen et al. showed that regulation of miR-203 might not include CpG island methylation in ESCC.20 Although hypermethylation of miR-203 upregulated the risk of ESCC in Chinese,19 the underlying link between miR-203 expression and promoter methylation in ESCC remains unclear, especially in Kazakhs. We suppose that the expression of miR-203 is correlated with promoter methylation in Kazakh ESCC.

Considering that the mechanism underlying abnormal DNA methylation may induce aberrant gene expression, we determined whether the expression of miR-203 is modulated by epigenetic modifications by indirectly silencing or activating miR-203 genes in Kazakh ESCC patients. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) was performed to cope with this problem, and the methylation of individual CpG units in 386 base pair regions containing 32 CpG sites within 21 CpG units at the miR-203 promoter regions with a total of 145 Kazakh tissues was quantitatively evaluated. Expression of miR-203 was also analyzed to explore the relationship between promoter methylation and gene expression. We found, for the first time, that promoter hypermethylation was correlated with downregulation of miR-203 in Kazakh ESCC. Our findings showed that hypermethylated miR-203 is a potential biomarker of ESCC carcinogenesis and could be an alternative approach for molecular-targeted prevention and therapy.

Results

miR-203 promoter is frequently hypermethylated in Kazakh patients with ESCC

The MassARRAY System allows quantitative high-throughput detection and analysis of a single CpG site methylation within a target fragment (CpG island). A single CpG site or a combination of CpG sites forms a CpG unit. We therefore could acquire accurate CpG site methylation data and calculate ratios or frequencies by MALDI-TOF-MS. EpiTYPER v1.0.5 software was used to analyze the methylation status of miR-203 in all samples collected from Kazakh patients with ESCC (n = 99) and NETs (n = 46). The amplicon detected in the promoter regions of miR-203 was 386 base pairs in length and contained 32 CpG sites that can be divided into 21 CpG units. Among these CpG units, one CpG unit (CpG_13) was not successfully detected. The final data set consisted of 20 CpG units (4495 sites in 145 analyzed samples).

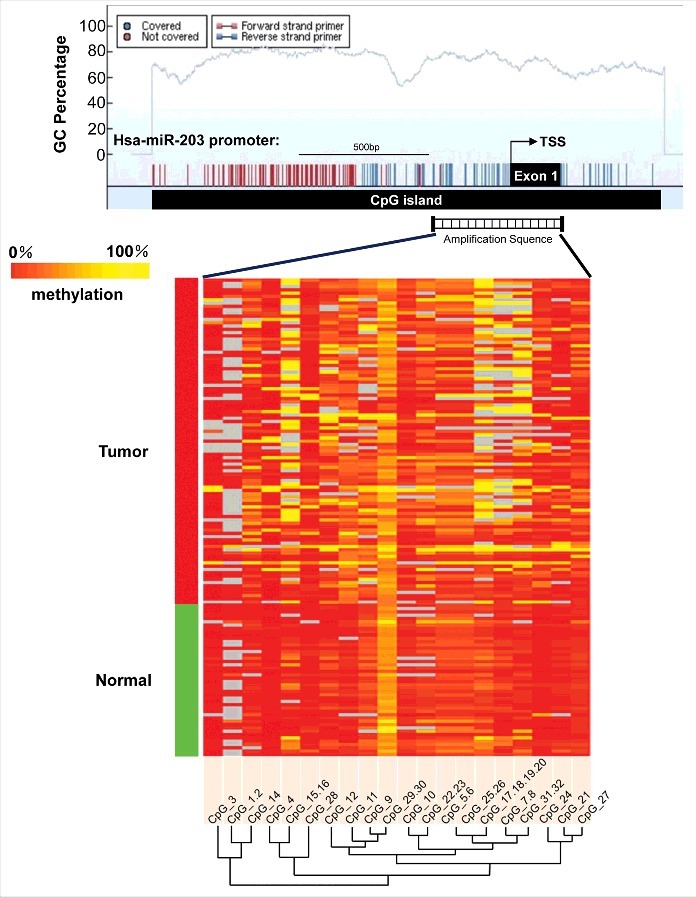

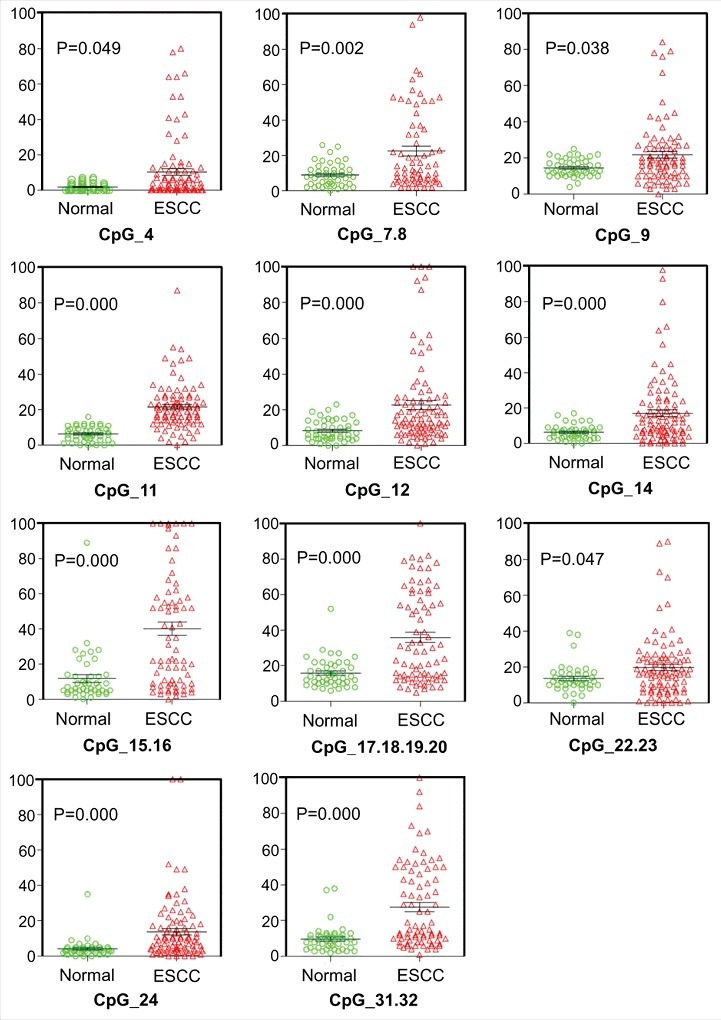

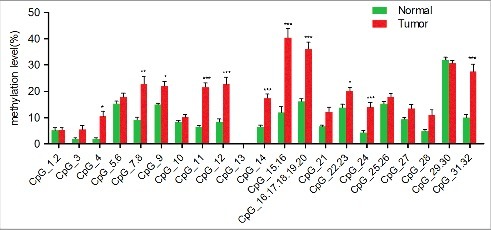

An unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis, which provides an equitable view of the relationships between ESCC and CpG units, was used (Fig. 1). CpG methylation levels of the samples could be identified based on color (which varied from red to yellow, indicating a methylation range of 0% to 100%) for each miR-203 CpG unit in each sample. The patterns observed in the cluster analysis indicated that the methylation status of ESCC tissues was notably different from that of NETs. The methylation level of every CpG unit within miR-203 promoter was also analyzed by GraphPad Prism 5 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S2). The results showed that normal samples are characterized by consistent low methylation levels and ESCC samples display more variable methylation patterns. We assessed the methylation level of each CpG unit within the miR-203 promoter and found that 19 CpG units (except for CpG_13 and CpG_29.30) were more highly methylated in ESCC than in NETs (Fig. 3). Nonparametric test showed that apart from CpG_1.2, CpG_3, CpG_5.6, CpG_10, CpG13, CpG_21, CpG_25.26, CpG_27, CpG_28, and CpG_29.30, the mean methylation levels at CpG_4, CpG_7.8, CpG_9, CpG_11, CpG_12, CpG_14, CpG_15.16, CpG_17.18.19.20, CpG_22.23, CpG_24 and CpG_31.32 were all significantly higher in ESCC (mean methylation = 10.44%, 22.78%, 21.99%, 21.52%, 22.63%, 17.25%, 40.35%, 35.92%, 19.94%, 13.92%, 27.53%, respectively) than in NETs (mean methylation = 1.89%, 9.15%, 14.83%, 6.47%, 8.36%, 6.47%, 11.83%, 16.09%, 13.72%, 4.26%, 9.94%, respectively; all P < 0.05) (Table S7).

Figure 1.

Genomic structure and distribution of miR-203 CpG dinucleotides over transcription start site (TSS) and hierarchical cluster analysis of CpG units methylation profiles of miR-203 promoter region in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 99) and normal esophageal tumors (n = 46). Each vertex indicates an individual CpG site. The positions and orientation of the MassARRAY primers are indicated by horizontal black bars. Each row represents a sample. Each column displays the clustering of CpG units, which are a single CpG site or a combination of CpG sites. The color gradient between red and yellow indicates methylation of each miR-203 CpG unit in each sample ranging from 0% to 100%. Gray represents technically inadequate or missing data.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the significantly differentially methylated CpG units within miR-203 promoter. The average methylation levels of 11 CpG units in miR-203 promoter between esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and normal esophageal Tumors (NETs). Green stands for the CpG methylation rate distribution of NETs, red stands for the CpG methylation rate distribution of ESCC. The middle line stand for the average rate of methylation, the horizontal lines on both sides of the middle stand for the standard error of average methylation rate.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of CpG methylation within miR-203 promoter. The distribution of 20 (excepting one that was not covered) analyzed CpG units within miR-203; abscissa stands for methylation rate and ordinate stands for grouping samples. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

miR-203 methylation correlated with clinicopathological parameters of ESCC

We further evaluated the relationship between the quantitative methylation patterns of every CpG unit within the miR-203 promoter and the clinicopathological parameters of the 99 Kazakh patients with ESCC (Table 1). The hypermethylation rate of CpG_22.23 positively correlated with age (r = 0.210, P = 0.043) (Table S3B). The CpG_31.32 hypermethylation rate of miR-203 in the different tumor locations was ranked as follows: lower > middle > upper (0.4337 ± 0.2708, 0.2286 ± 0.2020, and 0.1900 ± 0.1493, respectively, P = 0.006; Kruskal–Wallis H test) (Table S3C). Moreover, the CpG_24 average methylation rate of miR-203 in the gross pathologic classification of ESCC was ranked as follows: constriction type > fungating type > ulcerating type > medullary type (0.3300 ± 0.0283, 0.2250 ± 0.1234, 0.1163 ± 0.0985, and 0.0942 ± 0.0585, respectively; P = 0.04, Kruskal–Wallis H test) (Table S3D). The CpG_17.18.19.20 average methylation rate of miR-203 in the various differentiation types was ranked as follows: middle > high > low (0.4344 ± 0.2614, 0.2615 ± 0.2268 and 0.2375 ± 0.1472, respectively; P = 0.013, Kruskal–Wallis H test) (Table S3E). However, the CpG unit methylation of the miR-203 promoter showed no association with gender, lymph node metastasis, and TNM stage of Kazakh ESCC (Table S3A, S3F, S3G).

Table 1.

Relationships between miR-203 promoter methylation and various clinicopathological parameters in ESCC patients.

| Clinical parameters |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CpG Unit | Gender (W/P)a | Age (r/P)a | Tumor location (χ2/P)b | Tumor gross type(χ2/P)b | Differerntiation (χ2/P)b | Lymphatic metastasis (W/P)a | TNM stage (W/P)a | |||||||

| CpG_4 | 1628.0 | 0.509 | 0.125 | 0.228 | 3.444 | 0.179 | 3.894 | 0.273 | 2.048 | 0.359 | 1749.5 | 0.413 | 1312.0 | 0.579 |

| CpG_7.8 | 876.5 | 0.399 | 0.186 | 0.126 | 0.901 | 0.637 | 0.543 | 0.909 | 2.239 | 0.326 | 973.5 | 0.930 | 703.5 | 0.391 |

| CpG_9 | 1074.5 | 0.078 | −0.055 | 0.622 | 2.240 | 0.326 | 1.333 | 0.721 | 0.837 | 0.658 | 1285.5 | 0.349 | 2442.5 | 0.090 |

| CpG_11 | 1691.0 | 0.882 | −0.122 | 0.241 | 5.881 | 0.053 | 6.145 | 0.105 | 0.002 | 0.999 | 2554.5 | 0.118 | 3029.5 | 0.201 |

| CpG_12 | 2430.5 | 0.419 | 0.073 | 0.493 | 1.074 | 0.585 | 5.720 | 0.126 | 0.04 | 0.977 | 2475.0 | 0.942 | 1206.0 | 0.275 |

| CpG_14 | 1513.0 | 0.061 | 0.075 | 0.468 | 1.552 | 0.46 | 2.842 | 0.417 | 0.633 | 0.729 | 2787.5 | 0.688 | 1299.5 | 0.563 |

| CpG_15.16 | 963.0 | 0.497 | 0.133 | 0.245 | 0.542 | 0.763 | 0.222 | 0.974 | 1.117 | 0.572 | 1766.5 | 0.911 | 877.5 | 0.238 |

| CpG_17.18.19.20 | 1923.0 | 0.773 | 0.066 | 0.571 | 0.400 | 0.819 | 1.313 | 0.726 | 8.657 | 0.013* | 1647.0 | 0.758 | 968.5 | 0.944 |

| CpG_22.23 | 1612.0 | 0.693 | 0.210 | 0.043* | 0.463 | 0.793 | 4.421 | 0.219 | 4.532 | 0.104 | 1764.5 | 0.300 | 1254.0 | 0.165 |

| CpG_24 | 2747.0 | 0.514 | −0.009 | 0.934 | 0.428 | 0.807 | 8.304 | 0.040* | 2.044 | 0.360 | 2640.5 | 0.467 | 3072.0 | 0.437 |

| CpG_31.32 | 1311.0 | 0.992 | 0.064 | 0.571 | 10.287 | 0.006** | 7.617 | 0.055 | 4.158 | 0.125 | 1950.5 | 0.866 | 965.0 | 0.539 |

aMann–Whitney U test (two-sided); bKruskal-Wallis H test (two-sided); * P < 0.05.

Hypermethylated miR-203 associated with HPV infection in ESCC

Since our previous reports exhibited a strong positive association between HPV16 infection and Kazakh patients with ESCC, we sought to investigate whether the infection of HPV16 in ESCC affects the methylation level of miR-203. We detected the association between HPV16 infection and the methylation of CpG units within miR-203 promoter in ESCC (32 cases in the positive infection group and 67 cases in the negative infection group). Our data suggest that the methylation levels of CpG_15.16 and CpG_17.18.19.20 were higher in ESCC with HPV16 infection than in that without HPV16 infection (0.6146 ± 0.3765 vs. 0.3070 ± 0.2737, P = 0.01; 0.4777 ± 0.2762 vs. 0.3113 ± 0.2281, P = 0.007) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationships between miR-203 methylation and HPV16 infection in ESCC.

| HPV16 + (32 cases) |

HPV16 – (67 cases) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CpG Unit | n | ± S | N | ± S | Wilcoxon W | P |

| CpG_4 | 31 | 0.1290 ± 0.0291 | 63 | 0.0917 ± 0.0178 | 2905.0 | 0.466 |

| CpG_7.8 | 21 | 0.2900 ± 0.2996 | 48 | 0.1985 ± 0.1868 | 1615.5 | 0.400 |

| CpG_9 | 26 | 0.2304 ± 0.0494 | 57 | 0.2139 ± 0.0146 | 999.5 | 0.363 |

| CpG_11 | 29 | 0.2093 ± 0.1535 | 65 | 0.2198 ± 0.1206 | 1287.0 | 0.458 |

| CpG_12 | 27 | 0.2185 ± 0.2324 | 64 | 0.2303 ± 0.2417 | 2935.0 | 0.938 |

| CpG_14 | 31 | 0.1881 ± 0.2290 | 66 | 0.1633 ± 0.1712 | 3221.0 | 0.920 |

| CpG_15.16 | 24 | 0.6146 ± 0.3765 | 54 | 0.3070 ± 0.2737 | 1826.0 | 0.001** |

| CpG_17.18.19.20 | 22 | 0.4777 ± 0.2762 | 55 | 0.3113 ± 0.2281 | 1905.5 | 0.007** |

| CpG_22.23 | 31 | 0.2010 ± 0.1874 | 63 | 0.1967 ± 0.1664 | 1469.0 | 0.978 |

| CpG_24 | 31 | 0.1545 ± 0.2079 | 64 | 0.1305 ± 0.1504 | 1474.5 | 0.915 |

| CpG_31.32 | 27 | 0.3274 ± 0.2246 | 54 | 0.2493 ± 0.2354 | 2025.5 | 0.059 |

Mann–Whitney U test (two-sided); N stand for the number of analyzed CpG units; * P < 0.05. ** P < 0.01.

Expression silencing of miR-203 in Kazakh ESCC tissue

We quantitatively examined the mRNA expression of miR-203 by real-time PCR in ESCC and NETs to determine whether CpG methylation downregulates miR-203 gene expression (ESCC n = 97; NETs n = 50). Consistent with our expectation, the expression of miR-203 transcript showed an approximately 4.5-fold decrease in Kazakh ESCC patients compared with normal tissues (0.206 ± 0.336 vs. 0.908 ± 1.424, P < 0.001) (Table 3). The frequency distribution of miR-203 expression between ESCC and NETs showed that the miR-203 expression in ESCC was downregulated (Table S4). Moreover, Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis H test showed a significant association between decreased miR-203 expression and lymph node metastasis (P = 0.012), but miR-203 expression showed no correlation with gender, age, differentiation status, and TNM stage (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Expression of miR-203 in ESCC and NETs tissues.

| Group | n | miR-203 expression ± S | Wilcoxon W | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESCC | 97 | 0.206 ± 0.336 | 6072.0 | <0.001 |

| NETs | 50 | 0.908 ± 1.424 |

Mann–Whitney U test (two-sided); N stand for the number of sample cases; P < 0.05.

Table 4.

Relationship between miR-203 expression and clinical characteristics in Kazakh ESCC.

| Clinical characteristics | n | ± S | W / χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gendera | ||||

| Male | 50 | 0.260 ± 0.418 | 2187.5 | 0.404 |

| Female | 47 | 0.148 ± 0.207 | ||

| Age(years)b | ||||

| ≤45 | 7 | 0.320 ± 0.447 | 3.199 | 0.202 |

| 45–64 | 51 | 0.222 ± 0.396 | ||

| ≥64 | 39 | 0.165 ± 0.207 | ||

| Differentiation statusb | ||||

| High | 22 | 0.222 ± 0.323 | 0.122 | 0.941 |

| Middle | 57 | 0.207 ± 0.356 | ||

| Low | 18 | 0.184 ± 0.302 | ||

| Lymph node metastasisa | ||||

| Yes | 53 | 0.153 ± 0.336 | 2249.0 | 0.012* |

| No | 44 | 0.270 ± 0.329 | ||

| TNM stagea | ||||

| I and II | 64 | 0.212 ± 0.291 | 1535.5 | 0.525 |

| III and IV | 33 | 0.195 ± 0.414 |

aMann–Whitney U test (two-sided); bKruskal-Wallis H test (two-sided); n stand for the number of sample cases; * P < 0.05.

Correlation between promoter methylation and miRNA-203 expression

We used the bivariate correlation analysis to study the methylation levels at individual CpG units and the expression of miR-203. No correlation was found between the expression of miR-203 and the methylation levels of individual CpG units in Kazakh ESCC patients (CpG_4, CpG_7.8, CpG_9, CpG_11, CpG_12, CpG_14, CpG_15.16, CpG_17.18.19.20, CpG_22.23, CpG_24 and CpG_31.32) (P > 0.05) (Table S5). Given that the methylation level of a single CpG unit cannot represent the global methylation level in individual patients, we further analyzed the relationship between the comprehensive methylation level of 11 CpG units and the expression of miR-203. We found that the methylation level of a group of 11 completely methylated CpG units was approximately 6.5-fold lower than that of a group of at least 1 unmethylated CpG unit in Kazakh ESCC patients (0.087 ± 0.060 vs. 0.566 ± 0.303, P < 0.001) (Table 5). To determine further relationship between promoter methylation and miR-203 expression, we divided ESCC tissues into miR-203 high expression group (RQ > 1) and low expression group (RQ < 1). We used Mann–Whitney U test analysis and found that the hypermethylation of CpG_15.16 and CpG 31.32 units strongly correlated with the low mRNA expression level of miR-203 (P = 0.046 and 0.004) (Table 6). However, no correlation was found between methylation and gene expression of miR-203 in NETs (Table S6). These findings suggest that mRNA expression of miR-203 can be suppressed by hypermethylation of its promoter region in Kazakh ESCC tissues.

Table 5.

Association of miR-203 expression between different methylation groups in ESCC tissues.

| Groups | n | miR-203 expression ± S | Wilcoxon W | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 CpG units methylated completely | 20 | 0.087 ± 0.060 | 1596.0 | <0.001 |

| At least 1 CpG unit unmethylated | 56 | 0.566 ± 0.303 |

Mann–Whitney U test (two-sided); n stand for the number of sample cases; P < 0.05.

Table 6.

Comparison between each CpG unit methylation and miR-203 expression in Kazakh ESCC.

| High expression |

Low expression |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CpG Unit | n | Methylation rate () | RQ>1 | RQ<1 | Wilcoxon W | P |

| CpG_4 | 74 | >0.1040 | 6 | 18 | 1661.000 | 0.482 |

| <0.1040 | 24 | 26 | ||||

| CpG_7.8 | 58 | >0.2268 | 4 | 16 | 1116.000 | 0.191 |

| <0.2268 | 14 | 24 | ||||

| CpG_9 | 67 | >0.2190 | 4 | 14 | 1405.000 | 0.839 |

| <0.2190 | 22 | 26 | ||||

| CpG_11 | 64 | >0.2432 | 8 | 12 | 1372.000 | 0.899 |

| <0.2432 | 20 | 28 | ||||

| CpG_12 | 66 | >0.2242 | 4 | 16 | 1299.000 | 0.071 |

| <0.2242 | 20 | 26 | ||||

| CpG_14 | 70 | >0.1689 | 6 | 12 | 686.000 | 0.606 |

| <0.1689 | 14 | 38 | ||||

| CpG_15.16 | 62 | >0.4116 | 4 | 14 | 1024.000 | 0.046* |

| <0.4116 | 22 | 22 | ||||

| CpG_17.18.19.20 | 62 | >0.3452 | 4 | 14 | 1105.000 | 0.091 |

| <0.3452 | 24 | 20 | ||||

| CpG_22.23 | 72 | >0.2386 | 8 | 16 | 1614.000 | 0.296 |

| <0.2386 | 24 | 28 | ||||

| CpG_24 | 76 | >0.1686 | 4 | 16 | 1851.000 | 0.088 |

| <0.1686 | 24 | 32 | ||||

| CpG_31.32 | 66 | >0.2561 | 2 | 16 | 1172.000 | 0.004* |

| <0.2561 | 24 | 24 |

Mann–Whitney U test (two-sided), n stand for the number of analyzed CpG units; RQ stand for Relative Quantification. RQ>1 means the high expression of miR 203 in ESCC; RQ<1 means the low expression of miR-203 in ESCC. * P < 0.05.

Discussion

miRNAs are posttranscriptional cell regulatory factors. miR-203 is a skin-specific miRNA identified in recent years; this miRNA participates not only in the regulation of epidermal differentiation during the embryonic period and in the formation of skin protective layer, but also in the proliferation, differentiation, invasion, metastasis, and apoptosis of cancer cells.12 Promoter methylation, which causes the dysregulation of miR-203 expression, can induce tumorigenesis by inducing the expression levels of target genes, such as ΔNp63,21 SPARC,22 ABL1,23 AKT2,24 BCL-w.25 Although hypermethylation and low expression of miR-203 in patients with ESCC in Chinese population was shown before,19 little is known about miR-203 methylation in ESCC, especially in Kazakhs. We examined miR-203 methylation within its promoter region by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and gene expression by qRT-PCR and analyzed the correlation between miR-203 methylation and expression in Kazakh ESCC. Results showed that hypermethylated CpG units within the miR-203 promoter downregulated miR-203 expression in Kazakh ESCC. Our observations indicate that miR-203 could be a novel biomarker for molecular targeting prevention and therapy.

DNA hypermethylation of CpG sites within CpG islands causes cancer-related gene silencing by inactivating many tumor suppressor genes.7 This phenomenon has been proven for several miRNAs, such as miR-203,26 miR-9–1,27 miR-127,28 and miR-34b/c.29 We previously indicated that miR-34a inactivation correlates with aberrant CpG methylation in Kazakh patients with ESCC.10 To identify whether miR-203 methylation occurs in ESCC of Xinjiang Kazakhs, we detected the methylation levels of all our samples and found that the methylation status of ESCC tissues was notably higher than that of NETs. The methylation level of 19 CpG units (i.e., excluding CpG_29.30) was higher within ESCC tissues than NETs, indicating that miR-203 hypermethylation occurred in ESCC. Consistent with our findings, hypermethylated miR-203 was also found in endometrial carcinomas.16 However, studies implied that DNA methylation is not involved in miR-203 regulation in ESCC.20 This difference may be attributed to differences in culture, ethnic composition, and other factors. At this point, additional research is needed to overcome this problem. We further found that 11 CpG units of various CpG islands in the promoter region of miR-203 significantly differed at the quantitative hypermethylation level of each CpG site when comparing ESCC with NETs. As a result, several key CpG units in genetic transcription suggest that miR-203 hypermethylation could serve as diagnostic biomarkers in Kazakh ESCC.

Detection of methylation changes is crucial to assess prognosis and therefore provide a basis for clinical monitoring and risk assessment. Through an in-depth analysis of the relationship between gene methylation and tumor formation, we found a close relationship between methylation changes and conventional prognostic indicators. We detected methylation of individual CpG units within the promoter of miR-203 in ESCC tissues and found that the methylation rate of CpG_22.23 positively correlated with age and that the average hypermethylation rates of CpG_31.32, CpG_24, and CpG_17.18.19.20 of miR-203 significantly correlated with lower esophagus, constrictive type of ESCC, and moderately differentiated ESCC. Some studies demonstrated that miRNA methylation is bound up with metastasis,30 but we failed to find an association between hypermethylated miR-203 and metastasis development. This result may be attributed to the differences among our sample groups. Previous studies have investigated the combined effects of genetic polymorphisms and HPV infection on the risk of ESCC.31 HLA-DRB1*1501 and HLA-DQB1*0301 reportedly influence HPV-encoded epitopes and affect the risk of ESCC among Kazakhs in XinJiang, China.32 Melar-New et al. showed that the HPV E7 protein may downregulate miR-203 expression through the MAPK/PKC pathway during the proliferation and differentiation of epithelial cells.33 Based on these observations, we analyzed the correlation between HPV infection and miR-203 methylation. Results showed that the hypermethylation levels of CpG_15.16 and CpG_17.18.19.20 were associated with HPV16 infection. However, only precise information of CpG unit methylation levels signals clinical application value. Further research is warranted to illustrate the definite mechanism.

A recent study has demonstrated that miR-203 is closely connected with the differentiation of stratified squamous epithelia.34 Expression of miR-203 is downregulated in haematopoietic tumors,12 hepatocellular tumors,7 endometrial carcinomas,16 and cervical carcinomas17 but upregulated in breast cancer,14 colorectal cancer,35 and ovarian cancer.36 Such reports indicated that the expression of miR-203 varies in different tumor types. In the present study, the miR-203 gene showed a nearly 4.5-fold decrease in expression in Kazakh patients with ESCC compared with NETs. Moreover, our previous result indicated that the miR-203 gene with a high methylation level in ESCC has a nearly 4-fold decrease in expression when compared with non-cancerous adjacent tissues (NCAT).37 Consistent with our research, Feber et al. found that miR-203 shows a 2–10-fold lower expression in ESCC compared with normal epithelium.13 In addition, Yuan et al. detected low expression of miR-203 in esophageal cancer cell lines TE-1 and Eca109. Transfection with miR-203 mimic significantly prolonged cell doubling time, significantly increased apoptosis rate, and significantly decreased invasive ability.21 A significant correlation was also found between decreased miR-203 expression and lymph node metastasis. These observations indicate that miR-203 acts as a tumor suppressor and early-stage biomarker gene in Xinjiang Kazak ESCC.

Gene-specific hypermethylation leads to gene silencing by typically reflecting the hypermethylation of CpG-rich regions within gene promoter sequences. We hypothesized that the downregulation of miR-203 correlates with promoter hypermethylation in Kazakh ESCC. Our results indicate that expression of miR-203 with 11 completely methylated CpG units group was 6.5-fold lower than that with at least 1 unmethylated CpG unit group. In addition, comparing the methylation of CpG units and the expression levels of miR-203, we found that CpG_15.16 and CpG_31.32 with higher methylation levels in ESCC tissues exhibited lower miR-203 expression levels, indicating a reverse association between miR-203 CpG unit methylation and expression. Our findings indicate that expression of miR-203 in Xinjiang Kazak ESCC is suppressed via promoter methylation. Studies demonstrated that 5-AzadC demethylation treatment induced re-expression of mature miR-203 in vivo.12 These findings support the same viewpoint as ours. Recent studies have shown that miR-203 negatively regulates the expression of ΔNp63 at the posttranscriptional level in ESCC; by regulating ΔNp63-mediated signal pathways in human ESCC, miR-203 might function as a tumor suppressor.21 In addition, miR-203 serves as a tumor suppressor in Rhabdomyosarcoma by targeting p63 and inhibiting cell migration.11 In our previous study, p63 expression significantly differed between ESCC tissues and NCAT. However, no correlation was found between the expression of miR-203 and p6337. At the molecular level, miR-203 might regulate LASP1 expression directly and suppress the migration and invasion of cells in ESCC.38 In bladder cancer, miR-203 inhibits the expression of bcl-w to repress development and downregulates miR-203 target genes Akt2 and Src, which decrease cell proliferation and increase cell apoptosis.25,39 Moreover, miR-203 controls cell proliferation in haematopoietic malignancies by targeting ABL123 and induces apoptosis in colon and lung cancer cells by upregulating the expression of Puma.40 However, the functions of miR-203 in Xinjiang Kazak ESCC remain unambiguous and warrant further studies.

Conclusions

In summary, our data supports, for the first time, the hypothesis that CpG hypermethylation of the miR-203 gene could downregulate miR-203 expression in Kazakh patients with ESCC. In addition, CpG units within miR-203 in HPV16-positive ESCC were more heavily methylated. Moreover, decreased miR-203 expression significantly correlated with lymph node metastasis. Importantly, our results showed that hypermethylated miR-203 is a potential biomarker of ESCC carcinogenesis and that demethylation treatment of miR-203 could be an alternative approach for molecular-targeted prevention and therapy.

Materials and methods

Tumor samples

A total of 145 samples were used for miR-203 methylation detection, including 99 Kazakh ESCC tissue samples registered in the Departments of Pathology, Shihezi University School of Medicine and the People's Hospital of Xinjiang, China, during 1984 to 2011. Additionally, 46 samples of NETs were used for comparison. To determine the expression of miR-203, 97 ESCC tissue samples and 50 normal control tissues were collected. Details regarding the clinical features of ESCC patients are listed in Table S1 and Table 4. All specimens were obtained after surgery and were embedded in paraffin. Afterwards, they were sectioned into 5-μm slices. The paraffin sections of all esophageal cancer tissue were stained with hematoxylin–eosin and observed by professional pathologists under the microscope. All tumor samples we selected had rich and large cancer tissue. NanoDrop spectrophotometer was used to quantitatively detect the purity and concentration of the genomic DNA. We ensured the DNA purity (OD260/280) at 1.7–2.0 and concentration was greater than 50 ng/ul. DNA from tumors and normal tissues was extracted using standard methods. Differentiation grade, TNM stage, and lymph node status were determined in accordance with the UICC/AJCC TNM classification (Seventh Edition).

In this study, various clinic-pathological characteristics of Kazakh ESCC cases and controls were investigated. The age was 59.44 ± 9.02 (mean ± SD) years for the cancer samples and 56.57 ± 9.07 y for the normal sample (P = 0.95). There were 61 (61.6%) males and 38 (38.4%) females in the case group and 30 (65.2%) males and 16 (34.8%) females in the control group (P = 0.78). The cases included 29 (29.3%) well-differentiated patients (group G1), 55 (55.5%) moderately differentiated patients (G2), and 15 (15.2%) poorly differentiated patients (G3). Of the 99 ESCC cases, 69 (69.7%) were classified as stage I/II and 30 (30.3%) as stage III/IV. Forty of the patients presented with lymph node metastases. All participating patients have written informed consent before registration in the study. This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee at the First Affiliated Hospital of Shihezi University School of Medicine and was in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

DNA extraction and bisulfite modification

We isolated the DNA from 15–20 consecutive 10 μm thick tissue sections by proteinase K digestion and a tissue DNA extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The quality of genomic DNA was detected by β-globulin PCR amplification. As an internal control, purified genomic DNA samples were tested by PCR with human β-globulin primers 5′-CAGACACCATGGTGCACCTGAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCAATAGGCAGAGAGAGTCAGTG-3′ (reverse), showing suitable DNA quality and quantity. Samples with positive ß-globulin PCR amplification, DNA purity (OD260/OD280) between 1.7 and 2.0, and with DNA concentration greater than 50 ng/µl were used for miR-203_15 PCR amplification. Purified genomic bisulfite-converted DNA samples were also successfully tested by PCR with human has-mir-203_15 primers 5′-aggaagagagTTTTTTAAGGTTTTAGTGAGTGGAGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-cagtaatacgactcactatagggagaaggctAATCCCCAAAACCTAACTAACTCC-3′ (reverse) to show that the samples could be used for follow-up experiments (Supplementary file 1: Fig. S1). Genomic DNA was stored at -20°C until used as template for each PCR reaction. Bisulfite was used to treat the genomic DNA by using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit™ in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol (Zymo Research, Orange Country, CA; Catalog No. D5001). Bisulfite conversion and DNA clean-up were combined in this treatment. A NanoDrop spectrophotometer was used to measure the converted DNA (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE).

Analysis of HPV16 infection by semi-nested PCR

Semi-nested PCR was conducted in 2 steps to detect HPV16E infection, and all purified samples were first tested by PCR with HPV16E6 primers 5′-GACCCAGAAAGTTACCACAG-3′ (forward I) and 5′-CACAACGGTTTGTTGTATTG-3′ (reverse) as an internal control, followed by HPV16E primers 5′-CAAGCAACAGTTACTGCGACGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CACAACGGTTTGTTGTATTG-3′ (reverse). We observed infection of HPV16E by gel imaging after 25 min.

Quantitative analysis of DNA methylation

UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu) was used to identify the sequence of the CpG islands. We found hsa-mir-203 loci in 14q32.33 (103653495 - 103653604) with a length of 110 bp and 179 CpG sites in CpG island within a length of 1538bp in the miR-203 promoter sequence. Primer sets for the methylation analysis of the miR-203 promoter were designed using EpiDesigner (http://epidesigner.com; Table S2). For each reverse primer, an additional T7 promoter tag was added for in vivo transcription, and a 10-mer tag was added to the forward primer to adjust for the melting temperature. Methylation of miR-203 was quantitatively analyzed by the MassARRAY platform (SEQUENOM, San Diego, CA) as described previously.10 Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), a new type of high-throughput quantitative methylation detection method, was combined with the base specificity of the enzyme reaction to test the methylation level of DNA. Mass spectra were collected by MassARRAY Compact MALDI-TOF (SEQUENOM), and the methylation proportions of individual units were generated by EpiTyper 1.0.5 (SEQUENOM). All experiments were performed in triplicate. Non-applicable readings and their corresponding sites were eliminated from analysis. Methylation level was expressed as the percentage of methylated cytosines over the total number of methylated and unmethylated cytosines.

Extraction of RNA and detection of mature miRNA level with SYBR Green qRT-PCR

RNA was extracted from tissue samples using the miRNeasy FFPE Kit reagent (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Real-time PCR was conducted in 2 steps. cDNA was amplified with specific primer sets: MiR-203 (miScript Primer Assay Hs_miR-203_1, MS00003766) and RNU6 (miScript PCR Control Assay Hs_RNU6_2, MS00033740) in a Stratagene Mx-3000P real-time thermocycler (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted with a SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen) containing ROX as a reference dye. RUN6B snRNA was used as internal control, and data were normalized by the comparative threshold cycle method. Ct values were averaged, and the relative level of miR-203 expression in ESCC was calculated by 2−△Ct (ΔCt = CtmiR-203 in ESCC tissues − CtRNU6 gene in ESCC tissues). RQ stands for relative quantification and indicates the fold-change in miR-203 expression in cancerous tissues relative to that in normal tissues. The difference between the expression level of miR-203 in ESCC and NETs was expressed by RQ value (RQ = 2−△△Ct, ΔΔCt = ΔCtESCC − ΔCtNETs). If the value of RQ > 1, miR-203 expression in the ESCC is higher than that in NET tissues; if the value of RQ < 1, miR-203 expression in the ESCC is lower than that in NET tissues.

Statistical analysis

Each CpG unit methylation data of miR-203 from 145 samples including ESCC and NETs were used for stratified cluster analysis by Cluster 3.0 and Tree View software. We used SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) to analyze and describe the data. Values were represented as mean ± SD. All P values were 2-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis H test in 2 groups or more were performed to compare the miR-203 methylation levels of CpG sites between ESCC and NETs, and among ESCC and clinicopathological parameters. Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare the methylation status of miR-203 and HPV16 infection in ESCC and to compare the relationship between miRNA-203 gene expression in Kazakh ESCC and clinical characteristics. Mann–Whitney U test was also conducted to compare the miR-203 expression between ESCC and NETs and between 2 methylation groups. Bivariate correlation and Wilcoxon W test were analyzed to evaluate the correlations between CpG unit methylation status and miR-203 expression.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81560399, 81360358, 81460362), the Major science and technology projects of Shihezi University (No. gxjs2014‑zdgg06), the Applied Basic Research Projects of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (No. 2016AG020), the high‑level talent project of Shihezi University (No. RCZX201533), and the Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholars of Shihezi University (No. 2015ZRKXJQ02).

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Author contributions

Conception and design: F. Li; Development of methodology: X.B. Cui, W.W. Wang, A.M. Chang, and X. Chen; Acquisition of data (provided acquired and managed patients, provided facilities, etc.): Y.Z. Chen, C.X. Liu, L. Yang, Y.T. Wei, W.H. Liang and L.D. Wang; Analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis): X.B. Cui, W.W. Wang, A.M. Chang and X. Chen; Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: X.B. Cui and X. Chen; Administrative, technical, or material support (i.e., reporting or organizing data, constructing databases): X.B. Cui, W.W. Wang, A.M. Chang, and X. Chen; Check and revise: W. Liu, S.G. Li, W.J. Zhang, H. Peng, N. Wang and J.M. Hu; Study supervision: F. Li and Y.Z. Chen.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010; 127:2893–917; PMID:21351269; https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.25516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu C, Wang Z, Song X, Feng XS, Abnet CC, He J, Hu N, Zuo XB, Tan W, Zhan Q, et al. Joint analysis of three genome-wide association studies of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese populations. Nat Genet 2014; 46:1001–6; PMID:25129146; https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui XB, Pang XL, Li S, Jin J, Hu JM, Yang L, Liu CX, Li L, Wen SJ, Liang WH, et al. Elevated expression patterns and tight correlation of the PLCE1 and NF-kappaB signaling in Kazakh patients with esophageal carcinoma. Med Oncol 2014; 31:791; PMID:24307345; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-013-0791-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin Y, Totsuka Y, He Y, Kikuchi S, Qiao Y, Ueda J, Wei W, Inoue M, Tanaka H. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in Japan and China. J Epidemiol 2013; 23:233–42; PMID:23629646; https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20120162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulis M, Esteller M. DNA methylation and cancer. Adv Genet 2010; 70:27–56; PMID:20920744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee E, Lee BB, Ko E, Kim Y, Han J, Shim YM, Park J, Kim DH Cohypermethylation of p14 in combination with CADM1 or DCC as a recurrence-related prognostic indicator in stage I esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 2013; 119:1752–60; PMID:23310950; https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuta M, Kozaki KI, Tanaka S, Arii S, Imoto I, Inazawa J miR-124 and miR-203 are epigenetically silenced tumor-suppressive microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 2010; 31:766–76; PMID:19843643; https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgp250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhardwaj A, Arora S, Prajapati VK, Singh S, Singh AP. Cancer “stemness”- regulating microRNAs: role, mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Curr Drug Targets 2013; 14:1175–84; PMID:23834145; https://doi.org/10.2174/13894501113149990190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldmann T, Schneider R. Targeting histone modifications–epigenetics in cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2013; 25:184–9; PMID:23347561; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui X, Zhao Z, Liu D, Guo T, Li S, Hu J, Liu C, Yang L, Cao Y, Jiang J, et al. Inactivation of miR-34a by aberrant CpG methylation in Kazakh patients with esophageal carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2014; 33:20; PMID:24528540; https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-9966-33-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diao Y, Guo X, Jiang L, Wang G, Zhang C, Wan J, Jin Y, Wu Z. miR-203, a tumor suppressor frequently down-regulated by promoter hypermethylation in rhabdomyosarcoma. J Biol Chem 2014; 289:529–39; PMID:24247238; https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.494716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chim CS, Wong KY, Leung CY, Chung LP, Hui PK, Chan SY, Yu L Epigenetic inactivation of the hsa-miR-203 in haematological malignancies. J Cell Mol Med 2011; 15:2760–7; PMID:21323860; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01274.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feber A, Xi L, Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Landreneau RJ, Wu M, Swanson SJ, Godfrey TE, Litle VR MicroRNA expression profiles of esophageal cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008; 135:255–60; discussion 60; PMID:18242245; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.08.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Liu CG, Veronese A, Spizzo R, Sabbioni S, Magri E, Pedriali M, Fabbri M, Campiglio M, et al. MicroRNA gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer Res 2005; 65:7065–70; PMID:16103053; https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandhu R, Rivenbark AG, Mackler RM, Livasy CA, Coleman WB Dysregulation of microRNA expression drives aberrant DNA hypermethylation in basal-like breast cancer. Int J Oncol 2014; 44:563–72; PMID:24297604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Y-W, Kuo C-T, Chen J-H, Goodfellow PJ, Huang THM, Rader JS, Uyar DS. Hypermethylation of miR-203 in endometrial carcinomas. Gynecologic Oncol 2014; 133:340–45; PMID:24530564; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu X, Er K, Mao C, Yan Q, Xu H, Zhang Y, Zhu J, Cui F, Zhao W, Shi H. miR-203 suppresses tumor growth and angiogenesis by targeting VEGFA in cervical cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem 2013; 32:64–73; PMID:23867971; https://doi.org/10.1159/000350125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nair J, Jain P, Chandola U, Palve V, Vardhan NR, Reddy RB, Kekatpure VD, Suresh A, Kuriakose MA, Panda B Gene and miRNA expression changes in squamous cell carcinoma of larynx and hypopharynx. Genes Cancer 2015; 6:328–40; PMID:26413216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi Qf, Yang L, Zhu M, Zhang YP, Zhou LY, Wan MZ, Bao YQ, Liu YP. Hypermethylation and low expression of miR-203 in patients with esophageal cancer in Chinese population. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2016; 9(6):6245–6251 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, Hu H, Guan X, Xiong G, Wang Y, Wang K, Li J, Xu X, Yang K, Bai Y. CpG island methylation status of miRNAs in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2012; 130:1607–13; PMID:21547903; https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.26171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan Y, Zeng ZY, Liu XH, Gong DJ, Tao J, Cheng HZ, Huang SD. MicroRNA-203 inhibits cell proliferation by repressing DeltaNp63 expression in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2011; 11:57; PMID:21299870; https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-11-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benaich N, Woodhouse S, Goldie SJ, Mishra A, Quist SR, Watt FM. Rewiring of an epithelial differentiation factor, miR-203, to inhibit human squamous cell carcinoma metastasis. Cell Rep 2014; 9:104–17; PMID:25284788; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bueno MJ, Perez de Castro I, Gomez de Cedron M, Santos J, Calin GA, Cigudosa JC, Croce CM, Fernandez-Piqueras J, Malumbres M. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of microRNA-203 enhances ABL1 and BCR-ABL1 oncogene expression. Cancer Cell 2008; 13:496–506; PMID:18538733; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2008.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J, Chen Y, Zhao J, Kong F, Zhang Y. miR-203 reverses chemoresistance in p53-mutated colon cancer cells through downregulation of Akt2 expression. Cancer Lett 2011; 304:52–9; PMID:21354697; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bo J, Yang G, Huo K, Jiang H, Zhang L, Liu D, Huang Y. microRNA-203 suppresses bladder cancer development by repressing bcl-w expression. Febs J 2011; 278:786–92; PMID:21205209; https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07997.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z, Zhang B, Li W, Fu L, Fu L, Zhu Z, Dong JT. Epigenetic Silencing of miR-203 Upregulates SNAI2 and contributes to the invasiveness of malignant breast cancer cells. Genes Cancer 2011; 2:782–91; PMID:22393463; https://doi.org/10.1177/1947601911429743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X, Pan Q, Wan X, Mao Y, Lu W, Xie X, Cheng X. Methylation-associated Has-miR-9 deregulation in paclitaxel- resistant epithelial ovarian carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2015; 15:509; PMID:26152689; https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1509-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai KW, Wu CW, Hu LY, Li SC, Liao YL, Lai CH, Kao HW, Fang WL, Huang KH, Chan WC, et al. Epigenetic regulation of miR-34b and miR-129 expression in gastric cancer. Int J Cancer 2011; 129:2600–10; PMID:21960261; https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.25919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deneberg S, Kanduri M, Ali D, Bengtzen S, Karimi M, Qu Y, Kimby E, Mansouri L, Rosenquist R, Lennartsson A, et al. microRNA-34b/c on chromosome 11q23 is aberrantly methylated in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Epigenetics 2014; 9:910–7; PMID:24686393; https://doi.org/10.4161/epi.28603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taube JH, Malouf GG, Lu E, Sphyris N, Vijay V, Ramachandran PP, Ueno KR, Gaur S, Nicoloso MS, Rossi S, et al. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-203 is required for EMT and cancer stem cell properties. Sci Rep 2013; 3:2687; PMID:24045437; https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui X, Chen Y, Liu L, Li L, Hu J, Yang L, Liang W, Li F Heterozygote of PLCE1 rs2274223 increases susceptibility to human papillomavirus infection in patients with esophageal carcinoma among the Kazakh populations. J Med Virol 2014; 86:608–17; PMID:24127316; https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.23775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu J, Li L, Pang L, Chen Y, Yang L, Liu C, Zhao J, Chang B, Qi Y, Liang W, et al. HLA-DRB1*1501 and HLA-DQB1*0301 alleles are positively associated with HPV16 infection-related Kazakh esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Xinjiang China. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012; 61:2135–41; PMID:22588649; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-012-1281-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melar-New M, Laimins LA. Human papillomaviruses modulate expression of microRNA 203 upon epithelial differentiation to control levels of p63 proteins. J Virol 2010; 84(10):5212–5221; PMID:20219920; https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00078-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen B, Song G, Liu M, Qian L, Wang L, Gu H, Shen Y. Inhibition of miR-29c promotes proliferation, and inhibits apoptosis and differentiation in P19 embryonic carcinoma cells. Mol Med Rep 2016; 13:2527–35; PMID:26848028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yantiss RK, Goodarzi M, Zhou XK, Rennert H, Pirog EC, Banner BF, Chen YT. Clinical, pathologic, and molecular features of early-onset colorectal carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2009; 33:572–82; PMID:19047896; https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31818afd6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iorio MV, Visone R, Di Leva G, Donati V, Petrocca F, Casalini P, Taccioli C, Volinia S, Liu CG, Alder H, et al. MicroRNA signatures in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 2007; 67:8699–707; PMID:17875710; https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu JM, Chang AM, Chen YZ, Yuan XL, Li F. Regulatory Role of miR-203 in Occurrence and Progression of Kazakh Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 2016; 6:23780; PMID:27029934; https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeshita N, Mori M, Kano M, Hoshino I, Akutsu Y, Hanari N, Yoneyama Y, Ikeda N, Isozaki Y, Maruyama T, et al. miR-203 inhibits the migration and invasion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by regulating LASP1. Int J Oncol 2012; 41:1653–61; PMID:22940702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saini S, Arora S, Majid S, Shahryari V, Chen Y, Deng G, Yamamura S, Ueno K, Dahiya R. Curcumin modulates microRNA-203-mediated regulation of the Src-Akt axis in bladder cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011; 4:1698–709; PMID:21836020; https://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Funamizu N, Lacy CR, Kamada M, Yanaga K, Manome Y. MicroRNA-203 induces apoptosis by upregulating Puma expression in colon and lung cancer cells. Int J Oncol 2015; 47:1981–8; PMID:26397233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.