ABSTRACT

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder characterized by dysfunction of the CFTR gene. It is a multisystem disease that most often affects White individuals. In recent decades, various advances in the diagnosis and treatment of CF have drastically changed the scenario, resulting in a significant increase in survival and quality of life. In Brazil, the current neonatal screening program for CF has broad coverage, and most of the Brazilian states have referral centers for the follow-up of individuals with the disease. Previously, CF was limited to the pediatric age group. However, an increase in the number of adult CF patients has been observed, because of the greater number of individuals being diagnosed with atypical forms (with milder phenotypic expression) and because of the increase in life expectancy provided by the new treatments. However, there is still great heterogeneity among the different regions of Brazil in terms of the access of CF patients to diagnostic and therapeutic methods. The objective of these guidelines was to aggregate the main scientific evidence to guide the management of these patients. A group of 18 CF specialists devised 82 relevant clinical questions, divided into five categories: characteristics of a referral center; diagnosis; treatment of respiratory disease; gastrointestinal and nutritional treatment; and other aspects. Various professionals working in the area of CF in Brazil were invited to answer the questions devised by the coordinators. We used the PubMed database to search the available literature based on keywords, in order to find the best answers to these questions.

Keywords: Cystic fibrosis/diagnosis, Cystic fibrosis/therapy, Cystic fibrosis/complications, Practice guideline

RESUMO

A fibrose cística (FC) é uma doença genética autossômica recessiva caracterizada pela disfunção do gene CFTR. Trata-se de uma doença multissistêmica que ocorre mais frequentemente em populações descendentes de caucasianos. Nas últimas décadas, diversos avanços no diagnóstico e tratamento da FC mudaram drasticamente o cenário dessa doença, com aumento expressivo da sobrevida e qualidade de vida. Atualmente, o Brasil dispõe de um programa de ampla cobertura para a triagem neonatal de FC e centros de referência distribuídos na maior parte desses estados para seguimento dos indivíduos. Antigamente confinada à faixa etária pediátrica, tem-se observado um aumento de pacientes adultos com FC tanto pelo maior número de diagnósticos de formas atípicas, de expressão fenotípica mais leve, assim como pelo aumento da expectativa de vida com os novos tratamentos. Entretanto, ainda se observa uma grande heterogeneidade no acesso aos métodos diagnósticos e terapêuticos para FC entre as diferentes regiões brasileiras. O objetivo dessas diretrizes foi reunir as principais evidências científicas que norteiam o manejo desses pacientes. Um grupo de 18 especialistas em FC elaborou 82 perguntas clínicas relevantes que foram divididas em cinco categorias: características de um centro de referência; diagnóstico; tratamento da doença respiratória; tratamento gastrointestinal e nutricional; e outros aspectos. Diversos profissionais brasileiros atuantes na área da FC foram convidados a responder as perguntas formuladas pelos coordenadores. A literatura disponível foi pesquisada na base de dados PubMed com palavras-chave, buscando-se as melhores respostas às perguntas dos autores.

Descritores: Fibrose cística/diagnóstico, Fibrose cística/terapia, Fibrose cística/complicações, Guia de prática clínica

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder characterized by dysfunction of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, which encodes a protein that regulates chloride transmembrane conductance. It is a multisystem disease that most often affects White individuals. In Brazil, the incidence of cystic fibrosis is estimated to be 1 in 7,576 live births; however, there are regional differences, with higher values being found in the southern states. 1

In recent decades, various advances in the diagnosis and treatment of cystic fibrosis have drastically changed the scenario of this disease, resulting in a significant increase in survival and a gain in quality of life. In Brazil, the current neonatal screening program for cystic fibrosis has broad coverage, and most of the Brazilian states have referral centers for the follow-up of individuals with the disease. Previously, cystic fibrosis was limited to the pediatric age group. However, an increase in the number of adult patients with cystic fibrosis has been observed, because of the greater number of individuals being diagnosed with atypical forms (with milder phenotypic expression) and because of the increase in life expectancy provided by the new treatments. 2 - 4 However, there is still great heterogeneity among the different regions of Brazil in terms of the access of patients with cystic fibrosis to diagnostic and therapeutic methods. The objective of this publication was to aggregate the main scientific evidence to guide the management of patients with cystic fibrosis, this body of evidence being compiled by the main health professionals involved in caring for this disease in Brazil.

METHODS

A group of 18 cystic fibrosis specialists (coordinators) devised 82 relevant clinical questions, divided into five categories: characteristics of a referral center; diagnosis; treatment of respiratory disease; gastrointestinal and nutritional treatment; and other aspects. Various professionals working in the area of cystic fibrosis in Brazil were invited to answer the questions devised by the coordinators of the guidelines.

We used the PubMed database to search the available literature based on keywords, in order to find the best answers to these questions. In addition, manual searches of references in articles or books were performed. The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine guidelines were used to classify the level of evidence for the questions regarding the treatment chapters. The guidelines include a classification system for levels of evidence of studies, with levels of evidence ranging from “1” (highest level) to “5” (lowest level). The classification system was simplified in 2011 in order to facilitate its clinical application. Chart 1A (JBP online appendix-http://jornaldepneumologia.com.br/detalhe_anexo.asp?id=51) provides further details on the current Oxford classification system.

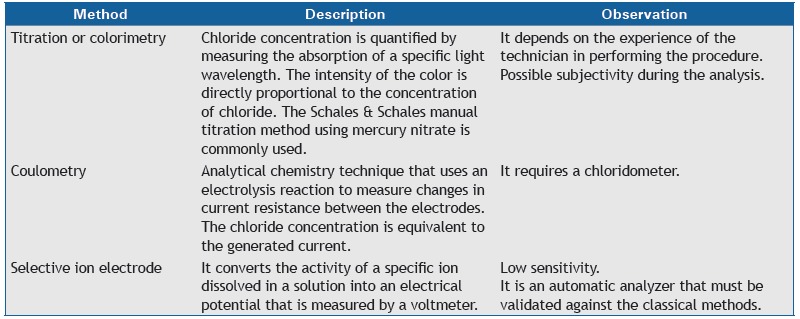

Chart 1. Methods of quantitative of sweat chloride determination.

A total of 2,352 publications were identified using the keyword search strategy, manual searches, and reference suggestions made by the authors. A total of 243 articles were selected for the present paper.

The first version of the text was written between March and August of 2016. The coordinators of each area were responsible for the validation of the level of evidence classification. In controversial cases, the questions were brought to a consensus meeting of coordinators on September 24, 2016. The final version was reviewed by the national coordinators (the first two authors) and sent to the editor of the JBP in February of 2017.

CHARACTERISTICS OF A REFERRAL CENTER

How important is a referral center in the care of patients with cystic fibrosis?

The complexity of cystic fibrosis and the peculiarities of its treatment result in the need for specialized treatment centers. 5 There is evidence that treatment at specialized referral centers, which have a multidisciplinary team, results in better clinical results, with an impact on prognosis. 6 , 7

What is a referral facility and what is a referral center?

A referral center is defined as one that treats at least 50 patients regularly. It should have a structure that meets the needs related to diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment.

A referral facility is one that treats fewer than 50 patients, and it can have a less complex structure. It should be affiliated with a referral center for the purposes of continuing education and of supplementing any needs. 5

How important is a multidisciplinary team? What would be the composition of such a team?

Given that cystic fibrosis is characterized by chronic multisystem involvement, it requires a multidisciplinary care model. 5 The care provided by a multidisciplinary team enables more comprehensive and effective treatments, resulting in an increased patient life expectancy. 5 , 8 , 9 The minimum multidisciplinary team for treating patients with cystic fibrosis should consist of the following professionals: pediatricians (when treatment is provided to children and adolescents); pulmonologists; gastroenterologists; physical therapists; nutritionists; nurses; psychologists; pharmacists; and social workers.

Are there differences between pediatric and adult centers? Are there advantages to planning for transitioning from pediatric to adult care?

Pediatric cystic fibrosis centers are quite different from adult cystic fibrosis centers. Adults have control and autonomy over their care. Pediatric centers need to meet demands that are characteristic of childhood, both in terms of structure and health professionals. Adult centers need resources to treat cases of greater complexity (comorbidities and different and more frequent complications, as well as pregnancy). 10

Transitioning an adolescent patient into an adult center is challenging, and there is evidence that transition programs optimize the process of transfer to the adult center. 11 - 15

What should the referral center infrastructure be like? What are the basic ancillary tests?

Referral centers should have multidisciplinary teams and resources so that they can provide accurate diagnoses and comprehensive care to patients with cystic fibrosis. They should be able to treat all cystic fibrosis complications, or provide referral to treatment, and should work in conjunction with facilities that are closer to the place of residence of the patients. 5 , 16 Patients should have 24-h/day access to the center or to emergency facilities affiliated with the center. 16

Each referral center should have or should ensure access to:

A laboratory for conducting tests to confirm the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis: sweat testing and/or CFTR gene mutation analysis

A pulmonary function laboratory

A microbiology laboratory with experience in and resources for identifying typical cystic fibrosis pathogens

A radiology department with CT

A clinical pathology laboratory with the capacity to perform routine tests, including hematologic tests, liver and kidney function tests, serology, and determination of proteins, vitamins, and immunoglobulins.

How important is microbiological segregation? How should it be done?

There is ample evidence that pathogen transmission can occur among individuals with cystic fibrosis, especially via droplets and contact. It can involve virulent strains, worsening disease progression. Infection control and prevention measures have been effective in decreasing pathogen transmission. Patient segregation should be instituted inside and outside the hospital setting to prevent cross infection. Cystic fibrosis centers should provide adequate structure and have a clear Infection control and prevention policy, including separate days of treatment for patients or use of different treatment spaces on the basis of patient colonization. 5 , 17 - 19

How important is commitment to care, research, and teaching?

A cystic fibrosis center should be committed to active participation in clinical and translational research, enabling patient participation in clinical trials. Education, research, and contribution to cystic fibrosis registries should be preferably performed by all centers. The various members of the multidisciplinary team should play an active role in research and education. Their work contributes to increasing and disseminating specialized knowledge, which plays a significant role in improving the quality of care. 5

What are the advantages of cooperation with cystic fibrosis patient/parent associations and with the Brazilian Cystic Fibrosis Study Group?

Cystic fibrosis patient/parent associations aim at defending the interests of this group of individuals, which includes making the disease known and improving diagnosis and treatment, in order to increase survival, improve quality of life, and integrate patients into society. 5 In North America and Europe, some of these associations still play an important role in promoting and funding scientific research and in registering patients.

In Brazil, bringing cystic fibrosis patient/parent associations closer to health professionals working in cystic fibrosis (currently represented by the Brazilian Cystic Fibrosis Study Group) would offer great advantages that could improve the current situation, such as aid in the inclusion of all Brazilian patients in the national registry (Brazilian Cystic Fibrosis Registry) and monitoring of the availability of medications in the various Brazilian states, in addition to the joining of forces to submit to the Federal Government a new (more comprehensive) directive on the care of the cystic fibrosis patient.

DIAGNOSIS

How does one confirm the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis after positive newborn screening?

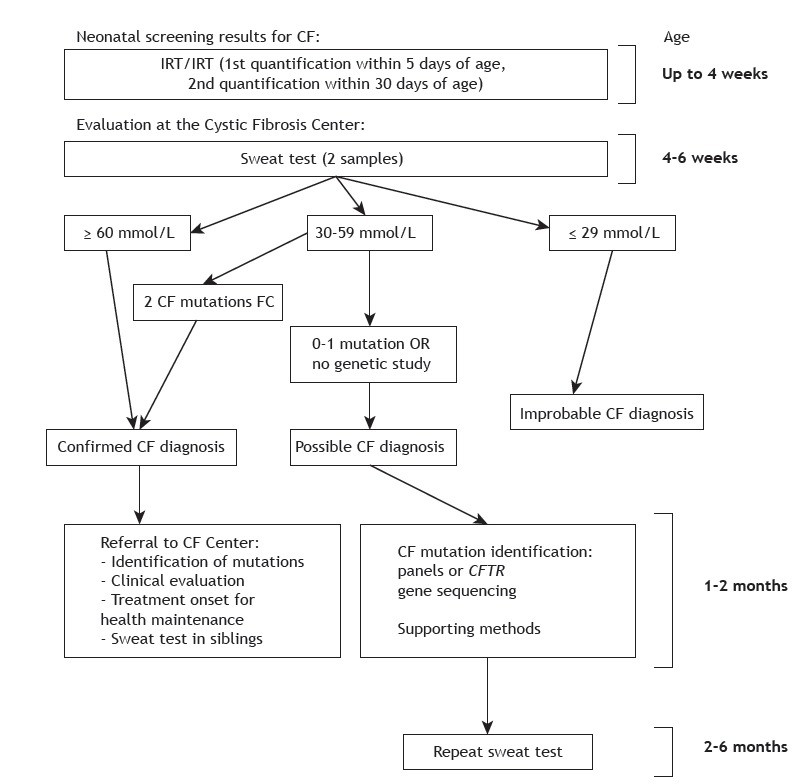

The cystic fibrosis newborn screening algorithm used in Brazil is based on two determinations of immunoreactive trypsinogen levels, the second of which is performed within 30 days of life. If screening is positive (i.e., two positive determinations), sweat testing is performed to confirm or rule out cystic fibrosis. Sweat chloride concentrations ≥ 60 mmol/L, as measured by quantitative methods, in two samples, confirm the diagnosis. Diagnostic alternatives are detection of two cystic fibrosis-related mutations and CFTR functional tests. Figure 1 shows a flowchart summarizing how infants with positive newborn screening results should be managed. 20 , 21

Figure 1. Management of cases with positive neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis. CF: cystic fibrosis; and IRT: immunoreactive trypsinogen. Adapted from Farrel et al. 21 .

Does a positive or negative newborn screening result confirm or rule out the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis?

No. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis identifies newborns at risk for the disease, but does not confirm the diagnosis. The rate of false-positive results with the algorithm based on measurement of immunoreactive trypsinogen levels is quite high. Conversely, a negative newborn screening result does not rule out the diagnosis. 22 , 23

After confirmation of the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in patients with positive newborn screening results, when should the patients be referred to a cystic fibrosis referral center?

Immediately after diagnosis, because cystic fibrosis requires early multidisciplinary management in order to maintain normal nutritional status and timely treat respiratory infections. 20 , 23

What are the steps involved in sweat testing? How does one ensure the quality of sweat testing?

Chart 2A (JBP online appendix) summarizes the steps that should be followed when performing sweat testing. Table 1 shows the reference values.

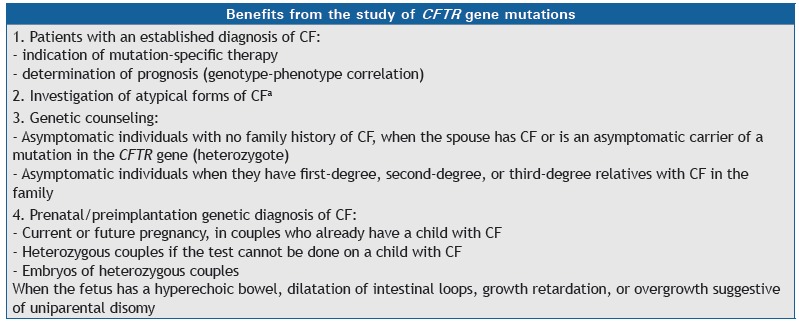

Chart 2. Benefits from the study of CFTR gene mutations.

CF: cystic fibrosis. aAtypical forms of CF: symptoms consistent with CF and intermediate results in the sweat chloride test.

Table 1. Reference values for sweat test.

| Result | Chloride, mmol/L | Electrical conductivity, mmol/L |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | < 30 | < 60 |

| Intermediate | 30-59 | 60-90 |

| Positivea | ≥ 60 | > 90 |

Quantitative chloride analysis in sweat should be carried out on a different day in order to confirm the result.

It is recommended that laboratories qualified to perform sweat testing should have internal and external quality control and should perform at least 100 tests per year (at least 10 tests per year per technician). The percentage of insufficient sweat samples should not exceed 5% of the total samples collected. 24 - 26

What are the main approved methods of quantitative sweat chloride determination?

Chart 1 describes the main methods of chloride determination, all of which must be validated in each laboratory before use. 24 , 25

What is the role of sweat conductivity testing?

Despite the high level of agreement between sweat conductivity results and sweat chloride concentrations, sweat conductivity testing is still considered a screening test. 26 It is recommended that a patient with a sweat conductivity result greater than or equal to 50 mmol/L should undergo quantitative testing. Sweat conductivity testing has the advantages of being easy to use and yielding immediate results. 24 , 27 , 28

What are the minimum criteria for a laboratory to perform CFTR mutation studies?

Certification by the Brazilian National Health Oversight Agency

Capability to perform DNA extraction with different methods and from different sample types

Ability to identify the F508del mutation and other more prevalent mutations

Availability to perform CFTR mutation panel analysis and/or complete CFTR sequencing, either in its facilities, or by referral to other laboratories

Capability to interpret and report pathogenic variants

Should all patients with cystic fibrosis undergo genetic testing? How important is it to undergo genetic testing?

Yes, the identification of mutations in the CFTR gene has implications for prognosis and family planning, allowing the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis (Chart 2). In addition, there are drugs that act on specific mutations (CFTR protein correctors and potentiators), some of which have been approved in various countries, whereas others are in development. 21 , 29 - 32

What mutation panel should be investigated?

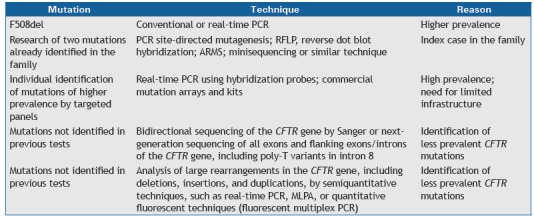

The investigation of mutations in the CFTR gene is described in Chart 3. 31 - 35

Chart 3. Stepwise molecular analysis for the identification of CFTR mutations.

PCR: polymerase chain reaction; RFLP: restriction fragment length polymorphism; ARMS: amplification refractory mutation system; and MLPA, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification.

When are CFTR functional tests indicated?

CFTR functional tests are indicated when sweat testing and genetic analysis are inconclusive. In essence, these tests assess CFTR protein function by measurement of chloride transport. Currently, nasal potential difference and intestinal current measurements are internationally standardized. Other promising tests, such as assessment of CFTR function by evaporimetry and by sweat gland potential difference measurement, are being studied. 36 , 37

TREATMENT OF RESPIRATORY DISEASE

What types of respiratory samples are most appropriate, how are they obtained, and how important are they?

Respiratory secretion samples are essential for follow-up of chronic bacterial infection of the airways in patients with cystic fibrosis, as well as for identification of opportunistic infections and as a follow-up method for therapeutic interventions. Expectorated sputum is the specimen of choice. For children who cannot expectorate, collect oropharyngeal cough swabs (tonsillar region and soft palate), nasopharyngeal aspirates, secretion following inhalation of 5% hypertonic saline solution, or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. These samples should be delivered to the laboratory immediately or kept under refrigeration for up to 3 h. 38 , 39

(Level of evidence: 4)

When should the samples be collected?

The samples should be collected at visits (with a maximum interval of 3 months), during exacerbations, and following treatment to eradicate the infection. Annual screening for mycobacteria and fungi is recommended for patients who cannot expectorate or for those with an unfavorable clinical course. 40

(Level of evidence: 5)

What are the routine culture methods and media?

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid specimens must be quantitatively cultured. The recommended culture media for routine microbiological investigation in cystic fibrosis are as follows:

Blood agar: universal for routine microbiological investigations

Mannitol agar: selective for Staphylococcus aureus

MacConkey agar: for gram-negative bacilli (including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Achromobacter spp., and Stenotrophomonas spp.)

Burkholderia cepacia complex-selective agar

Chocolate agar for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae

Sabouraud agar - for fungi, including Aspergillus spp. - supplemented with chloramphenicol or gentamicin

Liquid culture media, depending on the automation available, and a solid medium, such as Lowenstein-Jensen agar. For non-tuberculosis mycobacteria, blood agar and Burkholderia cepacia selective agar can also be used provided that these media are incubated for 14 days. 39 , 41 - 45

(Level of evidence: 5)

What are the methods of bacterial identification?

Phenotypic methods: typical S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia colonies are easily recognized, and few tests are needed.

Commercial, non-automated phenotypic kits: when associated with typical characteristics, they can be used for the identification of S. aureus and some glucose-nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli, such as P. aeruginosa, S. maltophilia, and Achromobacter spp., but are not suitable for the identification of B. cepacia complex, Burkholderia gladioli, Pandoraea spp., or Ralstonia spp.

Automated methods: they are not recommended for the identification of most glucose-nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli.

Molecular tests: they are recommended for the characterization of Achromobacter spp., B. cepacia complex, and the genera Ralstonia, Cupriavidus and Pandoraea.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS): it represents a rapid alternative, but has limitations, especially in identifying glucose-nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli. 42 , 43 , 46

(Level of evidence: 5 for all methods, except MALDI-TOF MS for the identification of glucose-nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli-level of evidence: 2)

What is the role of pulmonary function testing in the management of patients with cystic fibrosis?

Spirometry should be performed starting at age 5 years at every clinical visit or at least twice a year. Testing with and without bronchodilators is recommended. Washout techniques, with determination of the lung clearance index, have increasing and promising use in identifying early lung disease.

Studies have shown that FEV1 is essential for assessing the course and progression of cystic fibrosis, as well as for early detection of acute pulmonary exacerbations, being correlated with quality of life. FEF25-75% should also be taken into consideration, since it may be altered earlier. Whole-body plethysmography and oscillometry can complement the functional assessment. 9 , 47 - 50

(Level of evidence: 5)

What imaging tests should be performed in patients with cystic fibrosis? How often?

Chest X-ray is the most widely used test in the evaluation of patients with cystic fibrosis and is correlated with pulmonary function testing in detecting disease progression. 51 , 52

Chest HRCT is more accurate in the diagnosis and follow-up of lung lesions in individuals of all ages, including children with normal pulmonary function. 53 - 55 This benefit is questionable in infants, and there are technical obstacles inherent to this age group. 56 Magnetic resonance imaging of the chest has advanced in recent years and may become a future option because it is a radiation-free method. 57

Although there is no consensus regarding the frequency of imaging tests, an annual chest X-ray is recommended. In addition, it is suggested that, in the presence of clinical, functional, or radiological deterioration, a chest HRCT should be performed. Periodic follow-up with chest HRCT every 2 to 4 years may be indicated on a case-by-case basis. In cases of pulmonary exacerbation in cystic fibrosis, chest X-ray and chest HRCT can be used, always considering the use of the lowest radiation dose possible. 58 , 59

(Level of evidence: 2 for chest HRCT in individuals of all ages, except infants) (Level of evidence: 5 for chest X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging)

How important are nebulizers in the treatment of lung disease in cystic fibrosis?

The daily treatment of lung disease in cystic fibrosis includes nebulization of various medications that are key to maintaining lung health, and an inhaler system is essential for all patients with cystic fibrosis. 60 - 62

(Level of evidence: 5)

What inhaler system should be used for each type of inhalation therapy in cystic fibrosis?

Matching a substance to be inhaled with the right type of inhaler system is essential for ensuring the efficacy of treatment. Given the great variability of devices, it is recommended that the inhaler systems tested in the clinical trials of the medications should be used. 63 , 64

The following types are often used for each therapy 64 , 65 :

Ultrasonic nebulizers: hypertonic saline

Air-jet nebulizers: tobramycin; colistimethate; dornase alfa; and hypertonic saline

Active vibrating mesh nebulizers: tobramycin; colistimethate; dornase alfa; and aztreonam

Passive vibrating mesh nebulizers that adjust to the patient’s breathing pattern: tobramycin and colistimethate

(Level of evidence: 2)

What care should be given to inhalation therapy and chest physiotherapy devices?

Devices for the treatment of lung disease in cystic fibrosis include nebulizers and equipment used in chest physiotherapy for secretion removal. Bacterial contamination of nebulizers of patients with cystic fibrosis has been described, and educational programs on cleaning and disinfection of these devices have an impact on this situation. Cleaning after each use and daily disinfection by boiling, 70-90% alcohol, isopropyl alcohol, or 3% hydrogen peroxide are recommended. 17 , 66 - 69

(Level of evidence: 3)

What chest physiotherapy techniques are indicated in the treatment of lung disease?

Chest physiotherapy techniques should be performed daily after diagnosis in all patients with cystic fibrosis. 70 Chest physiotherapy has proven clinical benefits when compared with no intervention; however, there is no evidence of the superiority of one technique over the other. Patient preference is an essential factor for adherence to treatment, but the use of devices such as positive expiratory pressure masks and oscillatory positive expiratory pressure devices such as the Flutter®, the Shaker®, and the Acapella® is of great value and gives the patient independence. 71 The use of high-frequency chest wall oscillation devices, despite also giving the patient independence, was found to be inferior to the use of positive expiratory pressure masks in a recent study. 72 Noninvasive ventilation may be used as an adjunct to airway clearance therapy and in patients with advanced disease and hypercapnic respiratory failure. 73 - 76

(Level of evidence: 2 for chest physiotherapy)

(Level of evidence: 2 for the superiority of positive expiratory pressure masks vs. high-frequency chest wall oscillation devices)

(Level of evidence: 2 for noninvasive ventilation vs. no noninvasive ventilation as an adjuvant in the treatment of patients with advanced disease and hypercapnia)

What is the role of exercise in cystic fibrosis?

Exercise (aerobic and anaerobic) can aid in functional and postural outcomes, as well as in the self-esteem of patients with cystic fibrosis. An exercise frequency of 3-5 times a week and an exercise duration of 20-30 min are recommended, with benefits being observed from 6 weeks onward. Exercise should be part of the recommendations for patients with cystic fibrosis, including during hospitalizations. Physical activity does not replace chest physiotherapy. 77 - 82

(Level of evidence: 2)

What are the indications for the use of dornase alfa and what is its dosing schedule?

Inhaled dornase alfa has proven efficacy in cystic fibrosis as demonstrated by improvement in pulmonary function and quality of life, as well as by reduction in the number of respiratory exacerbations. 83 - 89 It is recommended starting at age 6 years in patients with lung disease at any stage. 83 , 87 , 90 The recommended dose is 2.5 mg once daily, with an appropriate nebulizer. Alternate-day administration may be considered in stable patients, 91 , 92 and twice-daily administration may be considered in patients with severe disease. 102 Inhaled dornase alfa can be used at any time, at least 30 min before chest physiotherapy. 93 , 94

(Level of evidence: 1)

When should dornase alfa be used in children under 6 years of age?

The use of dornase alfa should be considered in younger patients with persistent respiratory symptoms or with evidence of early lung disease (bronchiectasis, for example). 40 , 95 - 97

(Level of evidence: 2)

What is the role of hypertonic saline and mannitol? What are their recommended concentrations?

Hypertonic saline solution and mannitol are mucokinetic substances. They function as moisturizers on the airway surface, as osmotic agents, changing the rheological properties of mucus.

Twice-daily administration of 7% hypertonic saline solution reduces the number of respiratory exacerbations and produces improvement in pulmonary function and quality of life. Long-term studies are needed to determine whether there is sustained improvement. 87 , 98 - 100

Mannitol is available as dry-powder for inhalation (400 mg twice daily). Its use is associated with reduced nebulizer treatment time, clinical improvement, and pulmonary function improvement. 101 - 103 The use of mannitol is safe and well tolerated but should be preceded by the use of inhaled bronchodilators, given that they can act as irritating substances. Both are complementary approaches to dornase alfa therapy.

(Level of evidence: 1 for hypertonic saline and for mannitol)

What should P. aeruginosa eradication therapy be like?

Eradication therapy in cases of first acquisition of P. aeruginosa or early infection with P. aeruginosa aims to eradicate the bacterium and delay chronic infection. There are various therapeutic strategies, none being superior to the other. The most widely recommended strategy is to use inhaled tobramycin (300 mg) twice daily for 28 days. 104 - 107 Sodium colistimethate (1,000,000 to 2,000,000 IU, twice daily) is an alternative with consistent results and should be associated with oral ciprofloxacin for 2-3 weeks.

Inhalation therapy may be extended for 2-3 months. Intravenous antibiotic therapy for 2 weeks may be an option in selected cases and should always be followed by inhaled antibiotic therapy. Successful eradication is defined as negative bacterial culture results over a 1-year period after treatment completion. Eradication therapy, in addition to having significant clinical benefits, may be cost-effective. 103 - 107

(Level of evidence: 1)

What should therapy for eradicating B. cepacia complex strains be like?

The B. cepacia complex consists of a group of more than 80 closely related species, 108 , 109 B. multivorans and B. cenocepacia being the predominant species infecting people with cystic fibrosis. 110

Clinical manifestations in cystic fibrosis range from no symptoms to severe conditions with rapid clinical deterioration and fulminant progression to necrotizing pneumonia, respiratory failure, and sepsis (cepacia syndrome). 110 Treatment of B. cepacia complex is difficult because of intrinsic resistance of these organisms to most antimicrobial agents available. It is therefore recommended that, whenever possible, antibiogram-guided combination therapy be used. There is no available evidence assessing the efficacy of its eradication, nor are there recommendations for inhalation therapy for chronic infection. 110 , 111

(Level of evidence: 4)

What should therapy for eradicating methicillin-resistant S. aureus be like?

Chronic infection with methicillin-resistant S. aureus is associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with cystic fibrosis. 112 There have been reports of methicillin-resistant S. aureus eradication therapies using combinations of oral, topical, and inhaled drugs, such as sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, rifampin, fusidic acid, and chlorhexidine, in addition to vancomycin. Linezolid may be considered, but on the basis of less evidence. 113 Shorter treatment protocols (< 3 weeks) appear to be as effective as longer ones, as well as being less likely to result in intolerance and adverse effects. Combination therapy appears to have a greater likelihood of success than does monotherapy. 114 , 115

There is still no clear evidence of the benefits of eradication of methicillin-resistant S. aureus in patients with cystic fibrosis. 113 , 114 , 116 There is also no evidence to recommend inhaled antibiotic therapy for chronic infection with this pathogen.

(Level of evidence: 4)

What are the recommendations for chronic use of inhaled antibiotics in cystic fibrosis?

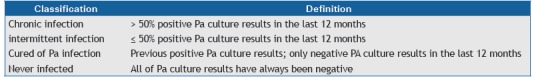

Table 2 shows the inhaled antibiotics that are used for suppression of chronic infection with P. aeruginosa. 23 , 117 , 118 The regular use of inhaled antibiotics delays deterioration of pulmonary function in patients chronically infected with P. aeruginosa. 23 , 87 , 117 - 119 Chart 4 presents the Leeds criteria, which classify respiratory infection with P. aeruginosa in patients with cystic fibrosis on the basis of respiratory secretion culture results obtained in the last 12 months. 120

Table 2. Treatment with inhaled antibiotics in accordance with a European consensus. 118 .

| Inhaled antibiotic | Dosea | Trade name |

|---|---|---|

| Aztreonam | 75 mg (3 times/day) | Cayston |

| Colistimethate sodium* | < 2 years of age: 0.5 million IU 2-10 years of age: 1 million IU > 10 years of age: 2 million IU | Colistin/Colomycin/Promixin |

| Colistimethate sodiumb (dry powder inhaler) | 1 capsule | Colobreathe |

| Tobramycin | > 6 years of age: 300 mg | Bramitob/Tobi |

| Tobramycin (dry powder inhaler) | > 6 years of age: 112 mg (4 capsules of 28 mg) | Zoteon |

Twice a day, except where otherwise indicated. bThat dose has been used in various European cystic fibrosis centers. When using I-neb® (Phillips Respironics) device, the dose should be reduced.

Chart 4. Leeds criteria for the classification of respiratory infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Pa: Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Adapted from Lee et al.(120)

Inhaled tobramycin is the most studied antibiotic, 119 , 121 , 122 and its use is recommended after age 6 years in patients with chronic infection with P. aeruginosa, regardless of disease severity, in alternating cycles of 28-days-on and 28-days-off therapy. Sodium colistimethate and aztreonam are other options. 23 , 87 , 123 , 124 Tobramycin inhalation powder has been used and shown to have equivalent efficacy to tobramycin inhalation solution, being associated with reduced treatment administration time and not requiring the use of nebulizers. 125

The recommendation of using suppression therapy in alternating months is aimed at preventing the development of bacterial resistance. In cases that are more severe, however, continued use of therapy or switching antimicrobial agents may be recommended. 124

It is advisable that the first inhalations be performed under supervision to allow for assessment of occurrence of drug-induced bronchoconstriction (wheezing, dyspnea, and chest tightness). Bronchodilator use is recommended, followed by bronchial hygiene via chest physiotherapy and, finally, antibiotic use in order to ensure greater medication deposition. 87 , 119 , 126 , 127

(Level of evidence: 1)

What are the indications for the use of azithromycin in patients with cystic fibrosis and how should azithromycin be used?

The use of oral azithromycin 3 times a week in cystic fibrosis patients over 5 years of age who are chronically colonized with P. aeruginosa results in improvement in pulmonary function and reduction in the number of exacerbations. 119 , 127 - 133

(Level of evidence: 1)

In patients who were not colonized with P. aeruginosa and had an FEV1 > 50% of the predicted value, azithromycin was found to reduce exacerbations by 50%, although with no improvement in pulmonary function. 134

(Level of evidence: 1)

The continued use of azithromycin is recommended, despite the lack of long-term assessment studies. Initial use for at least 6 months is suggested for assessment of response to therapy. 135 , 136 Side effects, such as epigastric pain, electrocardiographic changes, ototoxicity, and nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, should be monitored.

(Level of evidence: 1)

The use of azithromycin (250 mg for body weight < 40 kg and 500 mg for body weight > 40 kg; 3 times a week) is recommended in patients chronically colonized with P. aeruginosa who are over 5 years of age, as well as in those who are not colonized with P. aeruginosa and have frequent pulmonary exacerbations. Sputum sample collection for investigation of the presence of nontuberculous mycobacteria is recommended before initiation of azithromycin. 132 , 134

(Level of evidence: 2)

Given the possibility of a drug interaction between azithromycin and aminoglycosides, combined azithromycin and inhaled tobramycin use should be reassessed especially in patients with frequent exacerbations despite optimal treatment. 137

(Level of evidence: 3)

How does one recognize an acute pulmonary exacerbation?

Acute pulmonary exacerbations are characterized by clinical findings of increased cough, changes in secretion appearance, fever, abnormalities on pulmonary auscultation, decreased FEV1, decreased saturation, radiological abnormalities, and weight loss. 23

(Level of evidence: 5)

What therapy is indicated for acute pulmonary exacerbations?

For mild exacerbations (without hypoxemia or significant respiratory distress), use oral antimicrobial agents, on the basis of the last respiratory secretion culture result. For severe exacerbations or in cases of intolerance to oral medications, intravenous therapy (usually in hospital) is recommended, 139 but the choice of medications depends on previous respiratory secretion culture results and on patient history. 23

Antibiotic pharmacokinetics is different in individuals with cystic fibrosis, and dosage regimens should be adjusted 139 ) (Table 3). For P. aeruginosa, the combination of two or more antibiotics (usually a beta-lactam and an aminoglycoside) is recommended.

Table 3. Antimicrobial agents commonly used against acute pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis patients.a .

| Bacterium | Antimicrobial agent | Dose, mg/kg/day | Intervals and route |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Cephalexin Cefadroxil Cefuroxime Clarithromycin Clindamycin Amoxicillin + Clavulanic acid Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim Oxacillin Vancomycind Teicoplanind Linezolidd Tigecyclined |

50-100 (max, 4 g/day) 30 (max, 4 g/day) 20-30 (max, 1,5 g/day) 15 (max, 1 g/day) 30-40 (max, 2,4 g/day) 50b (max. 1,5 g/day) 40c (max, 1,6 g/day) 200 (max, 8 g/day) 40-60 (max, 8 g/day) 10 (max, 400 mg/day) 20 (max, 1,2 g/day) 2 (max, 100 mg/day) |

6/6 h p.o. 12/12 h p.o. 12/12 h p.o. 12/12 h p.o. 6/6 h or 8/8 h i.v. 8/8 h or 12/12 h p.o. 12/12 h p.o. 6/6 h i.v. 6/6 h i.v. 24/24 h i.v. or i.m. 12/12 h p.o. or i.v. 12/12 h i.v. |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Amoxicillin + Clavulanic acid Cefuroxime Cefaclor |

50b (max, 1,5 g/day) 20-30 (max, 1,5 g/day) 40 (max, 1 g/day) |

8/8 h or 12/12 h p.o. 12/12 h p.o. 8/8 h p.o. |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Ciprofloxacin Amikacin Tobramycin Ceftazidime Cefepimee Piperacillin + tazobactame Meropeneme Aztreonam |

30-50 (max, 1,5 g/day) 30 (max, 1,2 g/day) 20-30 (max, 1,5 g/day) 10 (max, 660 mg/day) 150 (max, 9 g/day) 150 (max, 6 g/day) 300 (max, 18 g/day) 120 (max, 6 g/day) 50 (max, 6 g/day) |

12/12 h p.o. 8/8 h i.v. 24/24 h i.v. 24/24 h i.v. 8/8 h i.v. 8/8 h i.v. 6/6 h or 8/8 h i.v. 8/8 h i.v. 8/8 h i.v. |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia f | Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim Chloramphenicol Levofloxacin |

40c (max, 1,6g/day) 60 a 80 (max, 4 g/day) 10 (max, 750 mg/day) |

12/12 h p.o. 6/6 h p.o. or i.v. < 5 years o f age: 12/12 h > 5 years of age: 24/24 h |

| Burkholderia cepacia complexf.g | Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim Meropenem Chloramphenicol Doxycycline |

40c (max, 1,6 g/day) 100c (max, 2,4 g/day) 120 (max, 6 g/day) 60 a 80 (max, 4 g/day) 1-2 (max, 200 mg/day) |

12/12 h p.o. 6/6 h i.v. (severe cases) 8/8 h i.v. 6/6 h p.o. or i.v. 12/12 h p.o. |

Max: maximum. aIt is recommended to control the serum level of drugs whose laboratory tests are available (e.g.: aminoglycosides and vancomycin).bAmoxicillin dose. cSulfamethoxazole dose. dThey should only be used against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. eAlso effective against methicillin-susceptible S. aureus. fLack of standardization regarding the level of efficacy of the antimicrobial agents. gUsually resistant to many antimicrobial agents.

Treatment time for an acute pulmonary exacerbation depends on clinical response, with the recommendation being 8 to 14 days. Patients with more severe disease may benefit from longer antimicrobial therapy. 138 , 140 - 142

In addition to antibiotic therapy, the treatment of exacerbations requires the participation of a multidisciplinary team, because there is often need for oxygen supplementation, use of long-term intravenous devices, intensified chest physiotherapy, and a different nutritional approach. 138 , 143 , 144

(Level of evidence: 5)

How does one assess response to treatment?

One should observe clinical parameters, such as respiratory symptoms, fever, and weight gain, as well as improvement in pulmonary function with a view to it returning to its baseline levels. Despite intensive treatment, approximately 25% of the patients who have an acute pulmonary exacerbation requiring intravenous therapy fail to recover completely to pre-exacerbation levels of pulmonary function, 23 , 138 - 142 emphasizing the need for maintenance therapies to prevent acute pulmonary exacerbations.

(Level of evidence: 5)

When and how should oxygen therapy be used in patients with cystic fibrosis?

In hypoxemic patients, continuous oxygen supplementation is associated with increased exercise tolerance and mild improvement in sleep and school/work attendance, but does not result in increased survival.

Oxygen therapy may be indicated on a case-by-case basis when SpO2 is below 90%, for relieving dyspnea, delaying the development of cor pulmonale, and improving the aforementioned outcomes. A PaO2 < 55 mmHg or an SpO2 < 88% is an indication for oxygen therapy, regardless of symptoms. The preferred route of administration is via a nasal cannula, at the lowest flow possible to maintain SpO2 above 90%. Intermittent use may be necessary during acute pulmonary exacerbations. 145 , 146

(Level of evidence: 5)

How does one diagnose and treat pneumothorax in patients with cystic fibrosis?

Pneumothorax manifests as dyspnea and/or sudden-onset chest pain. Extensive pneumothorax requires hospitalization and chest drainage, the only indication for pleurodesis being recurrence. Noninvasive ventilation and chest physiotherapy should be performed only in patients who received drainage.

Small pneumothorax should be drained only if there is clinical instability. 23 , 147

(Level of evidence: 5 for the non-recommendation of antibiotics)

(Level of evidence: 5 for the non-discontinuation of inhaled medications)

How does one classify and treat hemoptysis in patients with cystic fibrosis?

The management of hemoptysis depends on its volume. Bleeding ≥ 5 mL requires considering treatment with antibiotics for pulmonary exacerbation. 23 , 147 Bleeding ≥ 240 mL/day or > 100 mL/day for several days requires specialized treatment, and, when there is evidence of clinical instability, bronchoscopic treatment or bronchial artery embolization is indicated. 23 , 147 Surgical intervention can be performed in the acute phase only in refractory cases.

(Level of evidence: 2)

(Level of evidence: 5 for surgical intervention)

When are invasive and noninvasive ventilation indicated in cystic fibrosis?

The use of invasive ventilation in patients with severe disease is controversial and is associated with low survival rates, especially when the indication is respiratory infection. Invasive ventilation should be considered in cases of respiratory failure due to an acute, correctable precipitating factor (massive hemoptysis, pneumothorax, and during postoperative periods).

Noninvasive ventilation may be used as an adjuvant in the treatment of exacerbations and may be indicated in patients with daytime hypercapnia and sleep disorders. The use of noninvasive ventilation has been reported to be associated with increased exercise tolerance, improved quality of life and survival, and reduced decline in pulmonary function. Its use as a resource in chest physiotherapy provides benefits regarding dyspnea, muscle fatigue, and oxygenation. 73 - 75

(Level of evidence: 2 for noninvasive ventilation)

(Level of evidence: 5 for invasive ventilation)

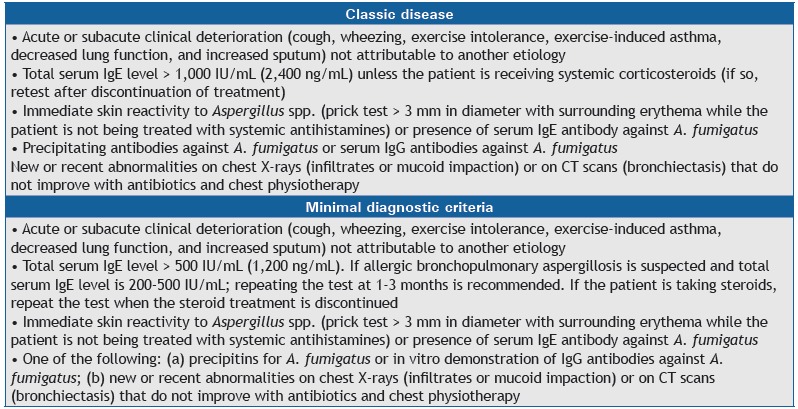

How does one diagnose and treat allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis?

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is a common complication in cystic fibrosis. Annual measurement of total IgE is recommended as a screening strategy. The diagnostic criteria for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis are presented in Chart 5. 124 , 148 Treatment is with oral prednisone with or without antifungal agents (Chart 6). 118 , 149 - 155

Chart 5. Diagnostic criteria for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

Chart 6. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis treatment.

(Level of evidence: 5 for diagnosis and treatment)

What is the approach to patients with positive sputum for Aspergillus spp.?

The presence of Aspergillus spp. in sputum usually does not mean disease. 156 If there is clinical worsening or a lack of response to antimicrobial therapy, one should investigate for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and consider fungal bronchitis. 157

(Level of evidence: 5)

What are the existing CFTR-modulating therapies, for which types of mutations have they been used, and what effects have been observed?

Potentiators increase the function of the CFTR protein that is expressed at the plasma membrane (class III, IV, and V mutations), and correctors correct defects of the protein that is not expressed at the cell membrane (class I and II mutations). 158 - 161

Ivacaftor is a potentiator that was initially studied in patients carrying the G551D mutation (a class III mutation). Its use had relevant effects resulting in a reduction in sweat chloride levels, improvement in FEV1, and weight gain, as well as in a reduction in the number of exacerbations and improvement in quality of life. Its use was subsequently approved for other class III mutations and R117H. 162 - 164

Among corrector drugs, a drug for class I mutations (ataluren) showed slight effects on pulmonary function and on the number of exacerbations in a phase 3 trial, only for patients who did not use inhaled tobramycin. 165

For the most prevalent class II mutation worldwide, F508del, the use of ivacaftor (a potentiator) in combination with lumacaftor (a corrector) was shown to produce a reduction in the number of exacerbations and a slight improvement in FEV1 and quality of life for homozygous patients, with no significant effects being observed for heterozygous patients. 166

(Level of evidence: 1 for ivacaftor in patients carrying a class III mutation [G551D])

(Level of evidence: 3 for ataluren in patients not exposed to tobramycin)

(Level of evidence: 2 for ivacaftor/lumacaftor in patients carrying a class II mutation [F508del])

Is there an indication for the use of ibuprofen in patients with cystic fibrosis?

The use of ibuprofen appears to delay the decline in pulmonary function and result in nutritional improvement, especially in children. Studies recommend doses between 20 and 30 mg/kg twice daily (maximum: 1,600 mg), in addition to monitoring of adverse events (discontinue use of ibuprofen when using aminoglycosides) and serum levels (50-100 mg/mL). Low doses are associated with a paradoxical increase in inflammation. Given the high rate of adverse events associated with ibuprofen and the difficulty in monitoring the serum level of the drug, its routine use is not recommended. The benefits of ibuprofen in patients with advanced disease are unknown. 167 - 174

(Level of evidence: 2)

What is the role of inhaled and systemic corticosteroids in cystic fibrosis?

There is no scientific evidence supporting the routine use of inhaled corticosteroids in cystic fibrosis; they can be used in patients with cystic fibrosis and asthma. It is recommended that, whenever possible, spirometry be performed to confirm the benefits of their use. 175 The chronic use of oral corticosteroids is also not recommended because of the risk of significant adverse effects, such as increased risk of diabetes and growth retardation. The effects of their short-term use and of their use during pulmonary exacerbations have yet to be elucidated. 176

(Level of evidence: 5 for not using oral corticosteroids chronically)

(Level of evidence: 5 for using inhaled corticosteroids)

What are the indications for the use of bronchodilators in cystic fibrosis?

Bronchodilators have been shown to provide benefits only in patients with confirmed bronchial hyperresponsiveness or evidence of asthma; in the latter case, bronchodilators should be used in combination with an inhaled corticosteroid. In this group of patients, an increase in pulmonary function was observed in the short and long term. Long-acting beta-agonists improved pulmonary function in the short term, with inconsistent long-lasting results, being therefore indicated only for individuals with confirmed asthma. 177 Regarding long-acting anticholinergics, tiotropium has recently been shown to be well tolerated, although the gain in pulmonary function was not statistically significantly different when compared with placebo. 178

(Level of evidence: 5 for beta-agonists in patients with cystic fibrosis and asthma)

(Level of evidence: 5 for tiotropium)

How does one diagnose and treat nontuberculous mycobacterial infections?

There has been an increase in the incidence of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in cystic fibrosis patients, with this incidence rising with advancing age. It is associated with progressive clinical deterioration, and differentiating between colonization and infection is essential, this differentiation being based on clinical, microbiological, and radiological criteria. 179

In patients who can spontaneously expectorate, mycobacterial cultures should be performed at least annually. The most commonly identified species are M. avium-intracellulare complex, M. chelonae, and M. abscessus. 180

Treatment of the infection with at least three antibiotics, usually including a macrolide, is recommended. The antimicrobial regimen should be tailored to the nontuberculous mycobacterial species, following guideline recommendations. 179 , 180

(Level of evidence: 5)

GASTROINTESTINAL AND NUTRITIONAL TREATMENT

How to suspect, diagnose, and manage meconium ileus?

Meconium ileum is the first clinical manifestation in patients with cystic fibrosis, in 15-20% of cases. Ileal obstruction by a plug of meconium and thick mucus may arise in intrauterine life with polyhydramnios, meconial peritonitis, and ileal distension, evidenced in prenatal ultrasonography. It is manifested by the absence of stool elimination in the first 48 h of life, accompanied by abdominal distension and vomiting (acute obstructive abdomen).

Clinical treatment includes hyperosmolar enemas, use of a nasogastric tube, hydration, and control of electrolytes. Complex cases (atresia, microcolon, necrosis, or perforation) should be treated surgically using minimally invasive techniques with ileostomy and reanastomosis in a timely manner.

(Level of evidence: 5)

How should electrolyte disturbances be prevented?

Salt loss from sweat and the large body surface pose a risk for dehydration and electrolyte disturbances in infants with cystic fibrosis, even without apparent loss. Signs, such as apathy or irritability, tachypnea, and prostration, may indicate dehydration, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hypochloremia, which are potentially life-threatening. Newborns and infants receiving breast milk or infant formulas should be supplemented with sodium chloride at a dose of 2.5-3.0 mEq/kg/day. 23 , 182 , 183

(Level of evidence: 5)

When should exocrine pancreatic insufficiency be clinically suspected?

We should suspect it in the presence of steatorrhea, chronic diarrhea, low weight gain, and signs of hypovitaminosis. The infant may also present with edema, hypoalbuminemia, and anemia. Indirect signs are observed through the characteristics of the stool, such as oiliness, foul smell, and diarrhea. 184

(Level of evidence: 5)

How do we confirm the diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency?

In clinical practice, the best method for confirming exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is the quantification of fecal elastase. Values < 200 μg/g of feces confirm exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (sensitivity, 86-100%). 185 Quantitative determination of fecal fat by the Van de Kamer method is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of steatorrhea, but its use is limited by technical difficulties. 185

(Level of evidence: 4)

How should pancreatic sufficiency be followed?

The fecal elastase test is simple and reliable in patients older than two weeks of age in the absence of liquid feces. Patients with pancreatic insufficiency should be monitored annually during childhood and during periods of growth failure, weight loss, or chronic diarrhea. The semiquantitative assessment of fat in stool (steatocrit) has relative value during the follow-up of patients, and the qualitative evaluation of fecal fats (Sudan III) has only a screening value for fecal fat loss.

(Level of evidence: 5)

How should enzyme replacement therapy be performed?

The need for replacement of pancreatic enzymes varies greatly and should be evaluated individually, relating clinical symptoms to the diet of each patient. The initial doses (Table 4) and their eventual subsequent increase should be guided by the improvement/resolution of the symptoms of malabsorption.

Table 4. Recommended initial doses for pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.a .

| Dose | Infants, per 120 mL of formula or breast milk | < 4 years of age, U/kg per meal | > 4 years of age, U/kg per meal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 2.000 U | 1.000 U | 500 U |

| Maximum per meal | 4.000 U | 2.500 U | 2.500 U |

| Snacks | --- | ½ dose | ½ dose |

Maximum daily dose: 10.000 U/kg.

Enzyme capsules should be swallowed whole and taken at the beginning of or during meals. Infants can ingest the granules mixed with milk or mashed fruit. Doses above 10,000 IU lipase/kg/day should be avoided, but they may be necessary in childhood, especially during accelerated growth phases. 186

(Level of evidence: 1)

How should the response to enzyme replacement therapy be evaluated?

The determination of the adequacy of enzyme replacement therapy is clinical: nutritional status, signs and symptoms of malabsorption, and patient’s weight gain plot should be verified. Inappropriate doses of pancreatic enzymes may result in abdominal pain, constipation, or diarrhea. Stool pattern and stool characteristics (oily, foul-smelling, floating, diarrheal, grayish, or yellowish) may indicate inadequacy of enzyme replacement therapy. 23 , 24

(Level of evidence: 5)

When should distal bowel obstruction syndrome be suspected and treated?

If there is incomplete obstruction, intermittent abdominal pain, nausea, and palpable masses in the lower right quadrant are noted, whereas in cases of complete obstruction, bilious vomiting and abdominal distension (acute obstructive abdomen) appear. The use of oral hydration and laxatives (such as polyethylene glycol) are indicated in cases of incomplete obstruction. In more severe cases, venous hydration, use of tubes, and use of enemas with polyethylene glycol or meglumine diatrizoate + sodium diatrizoate solution (Gastrografin®; Bracco Diagnostics, Canada) are indicated. Surgical treatment should be considered in cases of severe obstruction or in the presence of perforation. 187 , 188

(Level of evidence: 4)

Are there other common clinical gastrointestinal conditions in cystic fibrosis?

Approximately 30% of the patients have gastroesophageal reflux disease, and 40% have intestinal constipation. Recurrent acute pancreatitis is more common in patients with pancreatic insufficiency (10%), and rectal prolapse occurs in about 20% of the patients, especially those between 1-2 years of age. Patients with rectal prolapse and recurrent acute pancreatitis should be investigated for cystic fibrosis. The approach and treatment of all of these pathologies do not differ from those in patients without cystic fibrosis. 23

(Level of evidence: 4)

How should hepatic and biliary disease be monitored and managed?

The frequency of hepatic and biliary tract manifestations is shown in Table 5. Multilobular cirrhosis associated with hepatic insufficiency is rare, 189 but bile sludge and lithiasis in the biliary tract are common and generally asymptomatic. 190 , 191 Patient monitoring includes clinical evaluation at all visits, biochemical tests (liver enzymes and prothrombin time), and annual abdominal ultrasonography. Gastrointestinal endoscopy may be requested to investigate cases of gastrointestinal bleeding or suspected esophageal and gastric varices. Liver biopsy is rarely indicated. Patients with hepatic impairment should undergo quantification of alpha fetoprotein annually, due to the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. 189

Table 5. Frequency of hepatic and biliary tract manifestations in patients with cystic fibrosis.

| Organ | Approximate proportion, % |

|---|---|

| Liver Increased liver enzymes Hepatic steatosis Focal biliary cirrhosis Multilobular biliary cirrhosis Neonatal cholestasis Bile duct stenosis Sclerosing cholangitis Cholangiocarcinoma |

10-35 20-60 11-70 5-15 < 2 < 2 < 1 rare |

| Gallbladder Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis Microvesicules |

10-30 24-50 |

Adapted from Debray et al.(189)

The treatment of liver disease in patients with cystic fibrosis aims to improve bile flow, viscosity, and composition. Ursodeoxycholic acid at the dose of 15-20 mg/kg/day (2-3 doses) is recommended, but its use is controversial in the medical literature. There is no indication of treatment in the case of hepatic steatosis. 190 , 192 In cases of advanced liver disease, liver transplantation may be indicated.

(Level of evidence: 5)

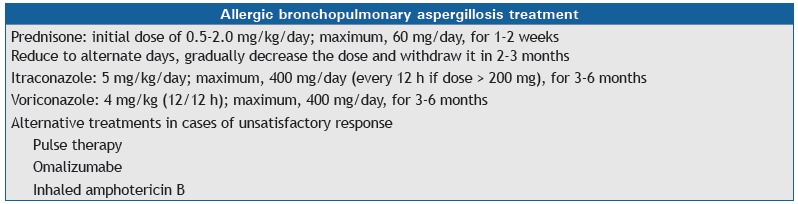

How should the nutritional status of patients with cystic fibrosis be monitored?

There is a strong association between pulmonary function and nutritional status. Periodic monitoring is necessary, especially regarding anthropometry, pulmonary function, gastrointestinal function, quality and quantity of food ingested, body composition, and biochemical evaluation.

Patients are more vulnerable to malnutrition during periods of rapid growth, and special attention should be paid to the first 12 months after the diagnosis, the first year of life, and the peripuberal period. 193 The parameters and periodicity for monitoring are shown in Chart 7. 194

Chart 7. Nutritional parameters and suggested monitoring frequency in patients with cystic fibrosis.

RNI: recommended nutrient intake. Adapted from Stallings et al.(194)

(Level of evidence: 5)

What reference data should be used?

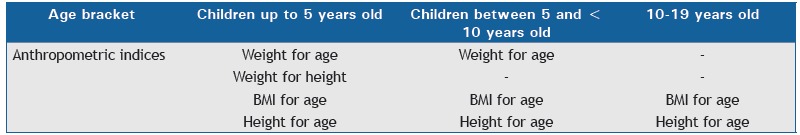

The growth curves used in Brazil are those by the World Health Organization (2006-2007), 195 , 196 and anthropometric data must be obtained and recorded in every medical visit (Chart 8).

Chart 8. Anthropometric indices recommended by the World Health Organization and adopted by the Brazilian Ministry of Health for the evaluation of the nutritional status of children and adolescents.

BMI: body mass index.

(Level of evidence: 5)

How to define nutritional deficiencies?

In children and adolescents, height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-height and body mass index (BMI)-for-age Z-scores with results < −2 reveal anthropometric deficiencies. It is suggested to associate the anthropometric evaluation with the growth rate and the target height. For adults, the recommended BMI is ≥ 22 kg/m2 for women and ≥ 23 kg/m2 for men. Additional body composition assessments should include skinfold thickness and arm circumference measurements, as well as bioimpedance, to help determine optimal nutritional status. 197

(Level of evidence: 5)

What are the main strategies for the prevention and treatment of nutritional disorders in cystic fibrosis patients?

The prevention of nutritional disorders presupposes the ingestion of a hypercaloric and high protein diet, vitamin supplementation, enzyme replacement therapy, and control of cystic fibrosis-related infections/exacerbations/other comorbidities. Treatment involves behavioral therapy, use of nutritional supplements, and the use of enteral diet via a nasoenteral tube in an acute phase and via gastrostomy for prolonged use. 198 - 201

(Level of evidence: 5)

What factors should be evaluated in the growth failure?

It is recommended to evaluate the intake of macronutrients and micronutrients, as well as to control malabsorption and infections/exacerbations. In addition, comorbidities, such as electrolyte disturbances, gastroesophageal reflux disease, bacterial overgrowth, diabetes, or behavioral appetite disorders should be evaluated. Less frequent causes of growth failure include lactose intolerance, celiac disease, food allergy, and inflammatory bowel disease. 193 , 202

(Level of evidence: 5)

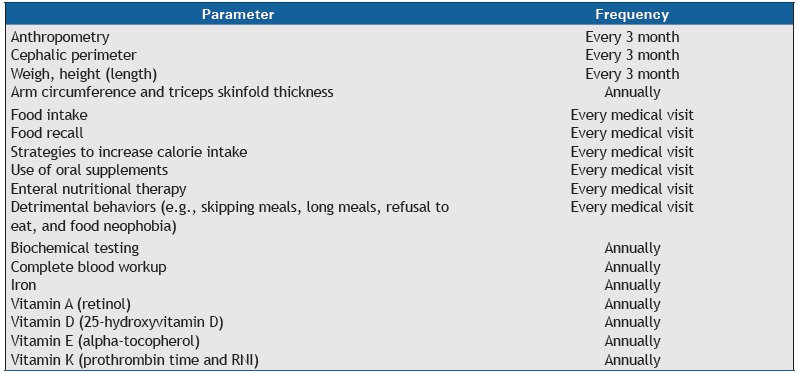

What are the options for nutritional therapy?

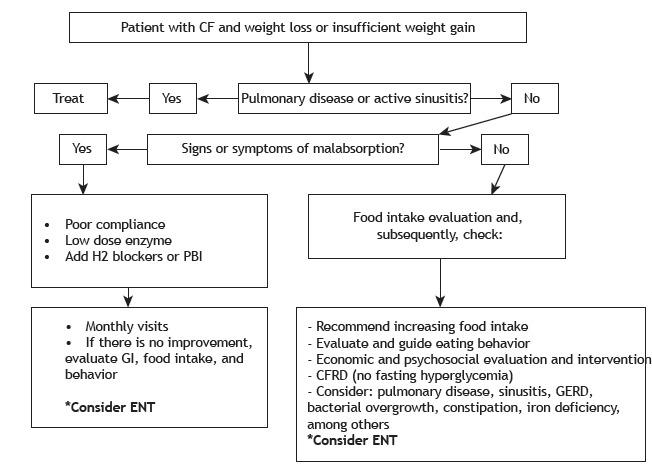

All of the patients should receive dietary advice. Behavioral therapy may be helpful for children between 3-12 years of age. Energy intake of 110-200% of recommended values for age and sex, with 35-40% of the energy supplied by lipids is recommended, as well as is vitamin supplementation, according to the needs of the patients. The use of dietary supplements and/or increased caloric density of the diet are indicated for patients showing weight loss or weight gain failure for 2-6 months, according to the age bracket. Enteral nutritional support by means of tubes is reserved for more severe cases and for short periods of time. Gastrostomy is indicated for long-term nutritional therapy. Parenteral nutrition is an exceptional measure, indicated for patients whose digestive tract cannot be used (during postoperative period or in the presence of critical illness) or in cases of short bowel syndrome. 193 , 202 Figure 2 shows the algorithm for the management of patients with low weight or inadequate weight gain.

Figure 2. Algorithm for patients with low weight or insufficient weight gain. CF: cystic fibrosis; PBI: proton pump inhibitor; GI: gastrointestinal; ENT: enteral nutrition therapy; CFRD: cystic fibrosis-related diabetes; and GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease. Adapted from Sinaasappel et al. 202 .

(Level of evidence: 5)

What are the requirements for vitamin supplementation in cystic fibrosis patients?

Patients with cystic fibrosis are at high risk of developing fat-soluble vitamin deficiency due to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. The recommended doses vary widely (Table 6 and Table 1A-online appendix). 193 , 202 Fat-soluble vitamins are better absorbed when given in combination with a meal and pancreatic enzymes.

Table 6. Doses for fat-soluble vitamin supplementation in patients with cystic fibrosis.

| Age | Individual daily vitamin supplementation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A, IU (µg) | Vitamin E, mg | Vitamin K, mg | Vitamin D, IU | |

| 0-12 months | 1,500 (510) | 40-50 | 0,3-0,5 | 400-500 |

| 1-3 years | 5,000 (1,700) | 80-150 | 0,3-0,5 | 800-1,000 |

| 4-8 years | 5,000-10,000 (1,700-3,400) | 100-200 | 0,3-0,5 | 800-1,000 |

| > 8 years | 10,000 (3,400) | 200-400 | 0,3-1,0 | 800-2,000 |

| Adults | 10,000 (3,400) | 200-400 | 2,5-5,0a | 800-2,000 |

| amg/week. | ||||

(Level of evidence: 2 for vitamin E)

(Level of evidence: 5 for vitamin A)

(Level of evidence: 3 for vitamin D)

(Level of evidence: 2 for vitamin K)

OTHER ASPECTS

When and how should diabetes be investigated in patients with cystic fibrosis?

Approximately 20% of the adolescents and 40% of the adults develop cystic fibrosis-related diabetes, resulting in worsening of nutrition, worsening of pulmonary function, and increase in morbidity and mortality rates, even in its asymptomatic phase. 208 Every cystic fibrosis patient older than 10 years of age should undergo the oral glucose tolerance test for the determination of blood glucose levels after fasting for 8 h and 2 h after the ingestion of 1.75 g/kg of glucose (maximum, 75 g). 209 - 213 The oral glucose tolerance test should be performed preferably when the patient is clinically stable.

The test is also recommended for patients with unexplained clinical worsening, prior to transplantation, in use of systemic corticosteroids, and before and during gestation, as well as in patients receiving enteral nutrition as nutritional support.

Blood glucose levels for the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes are similar to those for non-cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (Table 7).

Table 7. Screening and diagnostic criteria for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes and interpretation of blood serum glucose results by means of the oral glucose tolerance test.

| OGTT, mg/dl | Interpretation | Fasting BSG | BSG-2 h | BSG-1 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Healthy patients > 10 years of age • Prior to transplantation • Pregnancy scheduling • During pregnancy |

Glucose tolerance Glucose intolerance CFRD Indeterminate |

< 126 < 126 ≥ 126 < 126 |

< 140 140-199 ≥ 200 < 140 |

≥ 200 |

| Monitorização de glicemia de jejum e GPP de 2 h | ||||

| • During hospitalization • Outpatient setting 1. Pulmonary exacerbation, treated with i.v. antibiotic therapy or systemic glucocorticosteroids 2. Monthly, during and after nocturnal enteral feeding Glycated hemoglobin Random blood glucose testing |

DRFC DRFC DRFC |

GP de jejum ≥ 126 mg/dl GPP ≥ 200 mg/dl (persistente por 48 h) |

≥ 200 mg/dl durante ou após a dieta |

≥ 6,5% (< 6,5% não exclui) Glicemia ao acaso ≥ 200 mg/dl + poliúria e polidipsia |

OGTT: oral glucose tolerance test; BSG: blood serum glucose; BSG-2h: blood serum glucose 2 h after glucose intake during OGTT, GP-1h: blood serum glucose 2 h after glucose intake during OGTT; CFRD: cystic fibrosis-related diabetes; and PBG: postprandial blood glucose.

Adapted from Sermet-Gaudelus et al.(213)

(Level of evidence: 2)

What is the current recommended treatment for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes?

Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes should be treated with insulin. 208 - 210 Mean insulin doses range from 0.38 to 0.58 IU/kg/day, 214 distributed between slow-acting basal insulin and long-acting or ultralong-acting basal insulin at meals. Calories and carbohydrates should not be restricted, but complex carbohydrates and foods with low glycemic index should be favored and distributed in smaller portions and shorter intervals (2-3 h). Patients with changes in glucose levels during exacerbations might benefit from intermittent insulin administration. There is no definite consensus regarding the treatment of glucose intolerance.

(Level of evidence: 2 for insulin treatment)

(Level of evidence: 3 for recommendations regarding calories and carbohydrates)

When and how should osteopenia/osteoporosis be investigated in cystic fibrosis patients?

Low bone mineral density is common in cystic fibrosis patients, and it might occur since childhood. Bone densitometry is the gold standard test for diagnosing osteopenia/osteoporosis and should be performed in patients between 8-10 years of age. In patients younger than 20 years of age, the sites for that assessment are the total body and lumbar spine, whereas, in those aged 20 years or more, the sites are the hip and lumbar spine. The results should be adjusted for gender, age, and ethnicity, and they should be expressed as a Z-score for patients < 50 years of age and as a T-score for patients > 50 years of age and menopausal women. Bone densitometry should be repeated every 1-5 years, depending on the clinical classification of the findings. 23 , 215

(Level of evidence: 4 for body sites for bone densitometry)

(Level of evidence: 5 for confirming the need for bone densitometry)

What is the recommended treatment for osteoporosis/osteopenia in cystic fibrosis patients?

In order to prevent bone mass loss, it is recommended to maintain an adequate nutritional status, perform low-impact physical exercises, and avoid the use of inhaled or oral corticosteroids. 23 , 215

(Level of evidence: 5)

If the diagnosis of osteopenia is confirmed (Z-score between −1.0 and −2.5), vitamin D, vitamin K, and calcium supplementation should be initiated. 216

(Level of evidence: 2)

If the diagnosis of osteoporosis is confirmed (Z-score < −2.5), prescribe bisphosphonates: alendronate v.o. (70 mg/week or 10 mg/day); risedronate v.o. (35 mg/week or 5 mg/day); pamidronate i.v. (0.5-1.0 mg/kg/day for 3 days every 3 months); or zoledronic acid i.v. (0.025-0.05 mg/kg/day in a single dose every 6 months). 213 , 217

(Level of evidence: 1 for bisphosphonates)

When should the use of long-term venous access be considered and what are the options?

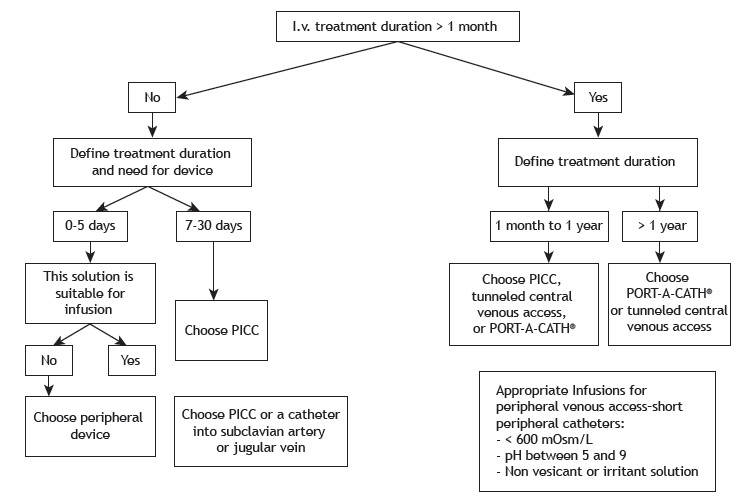

The evaluation of the need for using a long-stay intravenous device is based on the expected length of therapy, characteristics of the medications, such as pH (<5 or > 9), osmolarity (> 600 mOsmol/L), and the irritant capacity of such medications, as well as the durability of the intravenous device, the clinical condition of the patient, and the possibility of associated complications (Figure 3). 218

Figure 3. Selection of long-term endovenous device. PICC: peripherally inserted central catheter. Adapted from Santolim et al. 218 .

Options for long-term venous access devices include central peripherally inserted central catheters, central venous catheters (Intracath®, Becton Dickinson, Sandy, UT, USA), tunneled catheters (e.g., Hickman type), and totally implantable catheters (PORT-A-CATH®, Smiths Medical, Minneapolis, MN, USA). In a preserved venous network, the first option is the central peripherally inserted central catheter valve technology, which allows its intermittent use. 218

(Level of evidence: 4 for venous access)

When and how should sinus disease be approached in cystic fibrosis patients?

Sinonasal manifestations are common in patients with cystic fibrosis, especially nasal obstruction due to nasal polyposis and chronic rhinosinusitis. The extent of sinonasal disease may not correlate with the symptoms.

The patient should have routine otorhinolaryngological evaluation, since sinus disease may be related to pulmonary exacerbations. Imaging examinations are indicated only for surgical planning or investigation of complicated cases. 219

Treatment of sinonasal disease in cystic fibrosis patients consists of anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, topical medications, and surgery. 219 , 220

A study with the use of nasal dornase alfa in post-nasal endoscopic surgery patients showed benefits. However, the effectiveness depends on the surgical dilation of the paranasal sinus ostia to allow the medication to reach the sinus mucosa. 219 , 221 - 223

In relation to nasal topical corticosteroids, studies have shown positive effects on both the improvement of nasal symptoms and the reduction of polyps. 224 , 225

Surgical treatment should be considered in the persistence of nasal obstruction even after clinical treatment, in cases of anatomical obstruction, when there is a relationship with pulmonary exacerbations, in cases of lung transplantation, or in patients whose symptoms affect their quality of life. 219

No studies on the use of mucokinetic drugs are available, and the recommendations are extrapolated from patients without cystic fibrosis. It is advocated that 7% hypertonic saline solution would be more adequate due to its mucokinetic effect in cystic fibrosis patients, but the use of 3% saline solution is more widespread.

(Level of evidence: 2 for dornase alfa)

(Level of evidence: 3 for surgical treatment)

(Level of evidence: 5 for further recommendations)

When should lung transplantation be indicated and when should the patient be referred for it?

Lung transplantation should be considered in patients with cystic fibrosis whose predicted life expectancy < 50% in 2 years and who have functional class III or IV according to the New York Heart Association. Although there is no clear indicator of a 2-year survival, a decrease in FEV1 < 30% is related to a 2-year mortality of approximately 40% in males and 55% in females. Because the mean time on the waiting list for lung transplantation is approximately 2 years, adult patients with cystic fibrosis should be referred for lung transplantation under the following conditions: FEV1 < 30%; six-minute walk test distance < 400 m; clinical or functional worsening, especially in females; hypoxemia or hypercapnia (PaO2 < 60 mmHg and PaCO2 > 50 mmHg); and pulmonary artery systolic pressure > 35 mmHg. Patients with episodes of pneumothorax or hemoptysis should be referred early. Regarding pediatric patients, long-term results are less consistent, and, although the referral criteria are similar to those abovementioned, the indication should be individualized, taking into account the availability and expertise of the transplant team. 23 , 226 - 228

(Level of evidence: 5)

How should palliative care be in patients with cystic fibrosis and advanced lung disease?

Open and frank dialogue about the progression of the disease should be promoted early on, and palliative care should be provided by the staff responsible for the patient. The team must be trained and qualified regarding the basic principles of analgesia and sedation and be able to treat symptoms, such as pain, nausea, anxiety, and dyspnea.

Oftentimes, palliative care is instituted with the remainder of the active treatment. The desire of the patient and his/her family members, not only in general terms, but also in terms of investment in situations of emergency and end-of-life, should be known by the whole team.

(Level of evidence: 5)

What are the recommendations regarding the use of contraceptive methods in patients with cystic fibrosis?

Female patients with cystic fibrosis should be advised of the contraceptive methods available (hormonal methods, intrauterine devices, barrier methods, and sterilization). 230 The efficacy of these methods is similar to that for the general population, except for the lower activity of hormonal contraceptives with the use of the new drugs (ivacaftor and lumacaftor). 231 Male patients, despite the fact that almost all are infertile, should be advised of the risks of sexually transmitted diseases. Although there is evidence of greater severity in the use of oral contraceptives in females, supposedly related to hormonal issues, their use does not seem to influence the evolution of cystic fibrosis. 232 Genetic counseling should be offered to all patients and their families, facilitating the prevention of cystic fibrosis in the affected families.

(Level of evidence: 5 for indication of contraceptives)

(Level of evidence: 5 for genetic counseling)

How to approach pregnancy in cystic fibrosis patients?

The pregnant woman with cystic fibrosis must be closely followed by the multidisciplinary team and by an obstetrician specializing in high-risk pregnancy. Oral glucose tolerance test and ultrasonography should be performed quarterly, as well as nutritional and pulmonary function monitoring.

Respiratory exacerbations should be treated aggressively. Most drugs used to treat cystic fibrosis do not compromise the fetus. Whenever possible, vaginal delivery should be performed with epidural anesthesia. 233 - 236 )

(Level of evidence: 5 for vaginal delivery)

What is the best way to approach infertility in cystic fibrosis patients?

Infertility or subfertility in both sexes usually accompanies cystic fibrosis. Female infertility appears to be related to the thickening of cervical mucus, whereas male infertility is related to congenital and bilateral absence of the vas deferens. 237 Sperm counts should be offered to every patient who wants to know his fertility level. Referral centers should provide access to various specialists, including gynecologists, urologists, geneticists, and human reproduction specialists, to guide couples and patients on investigation strategies and infertility treatments.

(Level of evidence: 5)

What is the importance of treatment compliance in cystic fibrosis?

The therapies recommended for the treatment of cystic fibrosis, despite their proven efficacy in survival, cause burden on patients, interfere with their quality of life, and impair their compliance with the treatment due to the complexity of the therapeutic regimens.

Strategies to overcome barriers and appropriate psychosocial interventions to improve compliance should be implemented by professionals from specialized centers. Open communication and discussion might help identify the key barriers, addressing the problems inherent to each family unit. These actions are essential, since adequate compliance with the actions inherent to the disease is related to relevant clinical benefits. 239 - 242