Abstract

Purpose

To assess the feasibility of a Home-based, Individually-tailored Physical activity Print (HIPP) intervention for African American women in the Deep South.

Methods

A pilot randomized trial of the HIPP intervention (N=43) vs. wellness contact control (N=41) was conducted. Recruitment, retention, and adherence were examined, along with physical activity (7-Day PARs, accelerometers) and related psychosocial variables at baseline and 6 months.

Results

The sample included 84 overweight/obese African American women aged 50–69 in Birmingham, AL. Retention was high at 6 months (90%). Most participants reported being satisfied with the HIPP program and finding it helpful (91.67%). There were no significant between group differences in physical activity (p=0.22); however, HIPP participants reported larger increases (M=+73.9 minutes/week, SD=90.9) in moderate intensity or greater physical activity from baseline to 6 months than the control group (+41.5, SD=64.4). The HIPP group also reported significantly greater improvements in physical activity goal-setting (p=.02) and enjoyment (p=.04) from baseline to 6 months than the control group. There were no other significant between group differences [6MWT, weight, physical activity planning, behavioral processes, stage of change]; however, trends in the data for cognitive processes, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and family support for physical activity indicated small improvements for HIPP participants (P> .05) and declines for control participants. Significant decreases in decisional balance (p=0.01) and friend support (p=0.03) from baseline to six months were observed in the control arm and not the intervention arm.

Conclusion

The HIPP intervention has great potential as a low cost, high reach method for reducing physical activity-related health disparities. The lack of improvement in some domains may indicate that additional resources are needed to help this target population reach national guidelines.

Keywords: Physical Activity, Health Disparities, Behavior Change, Women’s Health, Cancer Prevention

Introduction

An increasing body of evidence indicates that physical activity is a key modifiable risk factor for the development of multiple cancers, with the strongest support for breast and colon cancers. Meta-analyses (11,38) have consistently shown an inverse relationship between physical activity and risk for breast and colon cancers, as well as a dose–response relationship, with higher physical activity levels associated with significantly lower risk of developing breast and colon cancers. Breast and colon cancers are a concern for all women; however, African American women are disproportionally burdened by these malignancies (1).

Recent data from the American Cancer Society (1) show that, although incidence rates among African American and White women are similar for breast cancer (i.e., 124.3 per 100,00 vs. 128.1 per 100,000, respectively), African American women have a 29.9% higher death rate following a diagnosis than White women. The statistics for colon cancer are even more discouraging, with African American women having a 17.9% higher incidence rate than White women (i.e., 44.1 per 100,000 vs. 36.2 per 100,000, respectively) and a 29.4% higher death rate. Given physical inactivity is an established risk factor for these cancers (14), there is an urgent need to identify effective strategies to promote physical activity in this high-risk population.

The American Cancer Society (14) recommends that adults engage in a minimum of 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity physical activity or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity physical activity (or combination of these) to reduce cancer risk. Most Americans do not meet these guidelines and physical activity levels are particularly low among African American women. Recent self-report data from the 2000–2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) show that only 36% of African American women achieve these physical activity recommendations (7). In comparison, 49% of White women meet these recommendations. Such physical inactivity likely contributes to the previously mentioned cancer disparities and calls for intervention.

Past efforts to promote physical activity among African Americans have typically involved face-to-face programs (27). While results of these studies are generally favorable, such approaches have limited reach and may be difficult for African American women to attend given past research indicating that child care and monetary costs are frequently cited as barriers to physical activity (33). Moreover, face-to-face interventions are costly due to the staff and personnel resources needed to deliver such programs. Home-based interventions, on the other hand, minimize many of these barriers and represent a more cost-effective approach to reach a large number of people (36). These benefits led our research team to develop a Home-based, Individually-tailored Physical activity Print (HIPP) intervention for African American women in the Deep South (see Pekmezi et al. for details on intervention development, 26).

The HIPP intervention is grounded in the Social Cognitive Theory (2) and Transtheoretical Model (31). The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) posits that individuals move through a series of stages of motivational readiness as they adopt physical activity and use varying behavioral and cognitive strategies to advance through these stages of change. TTM-based interventions are often matched to the participants’ motivational readiness for physical activity behavior change for enhanced relevance and appeal. The Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) is an interpersonal approach which emphasizes the multiple, reciprocal influences on physical activity behavior including thoughts, feelings, and the social and physical environment. Key constructs from SCT such as self regulation (e.g., planning, goal setting), self efficacy (confidence in one’s ability to be active despite barriers), outcome expectations (beliefs about the likelihood of various physical activity outcomes; e.g., enjoyment) and social support from family and friends are established determinants of physical activity behavior (25, 23) and thus represent important intervention targets.

The HIPP intervention builds on our research team’s past studies (18, 19) developing and testing theory-based computer expert system-tailored self help print materials in mostly White samples, as well as extensive formative research on physical activity barriers and intervention preferences with our target population (11 focus groups, a small demonstration trial, see 28 for more detail). In the current study, a pilot randomized trial of the HIPP intervention vs. a wellness contact control condition was conducted among 84 underactive African American women in Birmingham, AL. Hypotheses were that recruitment, retention, adherence and program satisfaction data would support the feasibility and acceptability of the HIPP intervention. Moreover, we anticipated that women assigned to the HIPP intervention would report greater increases in physical activity and related psychosocial variables at 6-months in comparison to the control arm.

Methods

Design

The current feasibility study utilized a randomized controlled design in which 84 participants were assigned either to the six-month HIPP intervention or to a wellness contact control condition. Data were collected between 2014 and 2016. Recruitment, retention, and adherence were examined and a participant satisfaction survey was administered at 6 months. Minutes per week of moderate-vigorous physical activity were assessed using the 7-Day Physical Activity Recall (7-Day PAR) and accelerometers at baseline and six months, along with physical activity-related psychosocial variables.

Setting and sample

The study was conducted in the metropolitan area and surrounding communities of Birmingham, Alabama. All study assessments occurred at the Clinical Research Unit at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Center for Clinical and Translational Science. The Institutional Review Board at UAB provided human subjects approval and the trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02574689). The sample was primarily recruited via flyers on campus and in local municipal buildings (city hall, county health department), community centers, and libraries (See Pekmezi et al. for more detail on recruitment, 26).

To be eligible for the study, participants had to self-identify as African American and/or Black, female, between the ages of 50–69, post-menopausal (no menstrual periods for at least 12 months), and insufficiently active (e.g., self report engaging in moderate or vigorous physical activity < 60 min per week at screening). The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) was used to assess cardiovascular/musculoskeletal risk factors (6) and individuals with contraindications for unsupervised physical activity (e.g., a history of heart disease, myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, BMI over 45, orthopedic conditions which limit mobility) were excluded from participation. Finally, eligibility included not planning to move from the area within the next year or scoring below 19 on the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM, 8), as the intervention materials were written at a 4th grade reading level (16).

Protocol

After potential participants were screened by telephone for eligibility, they attended an orientation session to learn more about the study and complete the informed consent process. At this time point, participants were provided an ActiGraph GT3X accelerometer to wear for seven consecutive days and return at baseline assessment. Physical activity and psychosocial measures were collected at this baseline assessment and then participants were randomly assigned to one of the two interventions: the HIPP intervention or wellness contact control group. Treatment allocation was stratified by BMI (BMI < 30 and BMI ≥ 30). All participants received group-appropriate cancer prevention self-help print materials by mail for 6 months (see description of intervention arms below). Accelerometers were mailed to participants and worn again for 7 days prior to their 6-month assessment, at which time point physical activity and psychosocial variables were reassessed, along with participant satisfaction. A detailed description of study protocols can be found elsewhere (26).

Measurements

Physical activity

The 7-Day Physical Activity Recall (PAR) (3) is an interviewer-administered instrument that estimates minutes per week of physical activity. It has demonstrated reliability, internal consistency, and congruent validity with objective physical activity measures (37) and is sensitive to changes in moderate-intensity physical activity over time (9).

To corroborate self-report data, participants wore ActiGraph GT3X accelerometers on their left hip for 7 consecutive days at baseline and 6 months. Accelerometers measure both movement and intensity of activity and have been validated with heart rate telemetry (12) and total energy expenditure (24). ActiLife software version 6.1 was used to validate and analyze bouts of activity, with a cut point of 1952 counts/minute selected as the minimum threshold for moderate-intensity activity (10). Moreover, a minimum valid wear time was set at 5 days of at least 600 minutes of wear or 3000 minutes of wear over 4 days. Consistent with the physical activity data collected by the PAR (i.e., physical activity bouts of 10 minutes or more) and the focus of the national guidelines, only activity bouts ≥10 minutes were included in the estimation of total minutes/week of activity. These ten-minute activity bouts were defined as achieving the aforementioned cut-point for moderate-intensity activities or greater (i.e., >1951 counts/minutes) for at least ten consecutive minutes, with allowance of one to two minutes below these thresholds during the ten minute period.

Six-minute walk distance and participation in strength and flexibility exercises were also assessed at these time points. The 6-Minute Walk Test provides an estimate of fitness by measuring the distance that can be quickly walked on a flat, hard surface in 6 minutes (4, 5). The three items on strength and flexibility exercises (“Do you regularly do strength and flexibility exercises like sit-ups, push-ups, yoga, or stretching?”, “How many days per week do you do these exercises”, and “On the days that you do strength and flexibility exercises, how many minutes do you spend doing them?”) have been used in several similar past studies (17–19).

Psychosocial variables

A brief demographic questionnaire regarding age, education, occupation, race, ethnicity, history of residence, and marital status was administered to participants at orientation.

Social Cognitive Theory and Transtheoretical Model constructs were measured at baseline and 6-month assessments at the Clinical Research Unit and then update surveys were completed by mail at 6 weeks, 10 weeks, 4 months and 5 months in order to generate the tailored expert computer system feedback reports for intervention participants. Adherence in the current study was defined by participants completing at least 3 of these 4 required update surveys and mailing them back to the research center. To promote and maintain adherence, participants received $10 gift cards for completed update surveys and phone calls from staff if update surveys were past due or returned in the mail. The surveys included a 4-item Stages of Readiness Measure which classified participants’ stage of motivational readiness for physical activity and has shown reliability (Kappa = 0.78; intra-class correlation r = 0.84) and concurrent validity with measures of self-efficacy and physical activity (21). The 40-item physical activity processes of change measure has 10 subscales that address strategies and techniques that people use to advance through the stages of readiness for physical activity, with alphas ranging from 0.62 to 0.96 (21). Decisional balance for physical activity participation was examined by 16 items with acceptable internal consistencies (alphas: Cons = 0.79 and Pros = 0.95) and concurrent validity with stage of change measures (20). Self-efficacy for participating in physical activity despite barriers (e.g., inclement weather) was measured with 5 items (alpha = 0.82) (22). Social support for exercise from family and friends was assessed using a 13-item scale (alphas = 0.61–0.91) with previously established criterion validity (35). Outcome expectations of physical activity participation were examined by 9 items with internal consistency (alpha = 0.89) and validity based on confirmatory analysis and positive correlations with physical activity and self-efficacy (32). Physical activity enjoyment was assessed using an 18-item scale with high internal consistency (alpha = 0.96) and test-retest reliability (13). Self-regulation was measured by the Exercise Goal-Setting Scale (EGS) and the Exercise Planning and Scheduling Scale (EPS), which exhibited good internal consistency [α (EGS) = .89; α (EPS) = .87] and test–retest reliability (.87 and .89, respectively) (34).

At 6 months, participant satisfaction with the HIPP intervention and study protocol was assessed with an 18-item measure that the research team has used in several past studies (17–19). This questionnaire was adapted to assess the feasibility and acceptability of this approach to promoting physical activity among African American women in the Deep South.

HIPP intervention

Based on the Social Cognitive Theory (2) and Transtheoretical Model (31), the HIPP intervention emphasized behavioral strategies for gradually increasing physical activity levels until the national guidelines are reached and included regular mailings (i.e., three mailings in month 1, two mailings in months 2–3, and one mailing in months 4–6) of physical activity manuals that are matched to the participant’s current stage of motivational readiness and individually-tailored computer expert system feedback reports. Participant responses to the monthly update surveys on SCT and TTM variables (stage of change, self-efficacy, decisional balance, social support, outcome expectations, perceived enjoyment, and self regulation) were used by the computer expert system to generate appropriate messages for the feedback reports from a bank of 531 messages addressing different levels of the previously mentioned psychosocial and environmental factors affecting physical activity. For example, if a participant’s survey responses indicated low social support for physical activity from family and friends, the computer expert system selected messages reminding the participant that “getting help from other people and sharing your thoughts and struggles about becoming physically active can be very helpful” and offering ideas on how to enlist their support (e.g., “Try taking a class or finding a friend to meet for a walk”). Accusplit AE120XLv3-xBX pedometers and activity logs were provided to encourage self-monitoring of exercise behavior.

Efforts were made to address the intervention needs and preferences of the target population. Participants received tip sheets addressing physical activity barriers specific to African American women (e.g., time, negative outcome expectations, safety, costs, enjoyment, social support, fear of injury) that were informed by our prior focus group research (28). Moreover, based on participant feedback, we incorporated religiosity (included relevant scripture in intervention text), emphasized physical activity benefits other than weight loss (i.e., chronic disease prevention), highlighted preferred activities (walking, dancing, aerobics), and worked with a local African American female graphic designer to enhance the visual appeal of intervention materials. Further detail on formative research and the HIPP intervention is available in previously published reports by Pekmezi and colleagues (28).

Wellness contact control condition

Participants assigned to this condition received mailings with cancer prevention information on topics other than physical activity from the American Cancer Society website (www.cancer.org). The mailings were received at time points identical to those of the HIPP intervention participants’ physical activity materials, thereby controlling for the number of contacts.

Data analyses

Differences between the control and intervention groups at baseline were assessed by t-tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test for categorical variables. Group differences in physical activity and related psychosocial variables at 6 months were examined with a generalized linear model controlling for baseline values. The distributions of all variables were assessed for normality and transformations were considered as well as reporting of medians and IQR for non-normal data. As the overall conclusion was not altered by whether the non-normal physical activity variables were transformed or not, the untransformed (easier to interpret) version is presented.

Data were analyzed as intent-to-treat using complete case analysis as well as last observation carried forward and mixed models with the assumption that data were missing at random. Results were similar, so the p values for complete case analysis are presented. The numbers of participants with valid accelerometer data at both time points (N=41) were lower than for other measurements due to inadequate wear time data; however no differences in the baseline demographic characteristics were found among participants with and without valid accelerometer data. For all analyses a p of < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant and were performed with SAS version 9.4.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The sample was comprised of mostly obese, post-menopausal African American women living in the Birmingham, AL area (n=84). The average age was 57 years old. Most reported full-time employment (60.7%) and at least some college level education (92.9%), with 53.6% of participants reporting household income under $50,000 per year. See Table 1 for more detail on demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the HIPP study participants

| Characteristics* | Intervention (n=43) (M and SD or %) |

Control (n=41) (M and SD or %) |

Overall (N=84) (M and SD or %) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| African American women | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

|

| ||||

| Age (n=84) | 56.7 (4.8) | 57.3 (4.7) | 57.0 (4.7) | |

|

| ||||

| BMI at baseline* | 32.4 (5.2) | 31.8 (5.2) | 32.1 (5.2) | |

| ≥30 | 65.1% | 58.5% | 61.9% | |

| <30 | 34.9% | 41.5% | 38.1% | |

|

| ||||

| College Education | 51.2% | 60.9% | 56.0% | |

|

| ||||

| Full Time Employment | 65.1% | 56.1% | 60.7% | |

|

| ||||

| Annual household income < $50,000 | 48.8% | 58.6% | 53.6% | |

|

| ||||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/living with partner | 51.2% | 31.7% | 41.7% | |

| Single | 14.0% | 12.2% | 13.1% | |

| Divorced | 23.3% | 39% | 30% | |

| Separated | 2.3% | 4.9% | 3.6% | |

| Widowed | 9.3% | 9.8% | 9.5% | |

| Unknown/refused | 0% | 2.4% | 1.2% | |

There were no significant group differences in demographic characteristics or changes in BMI from baseline to 6 months

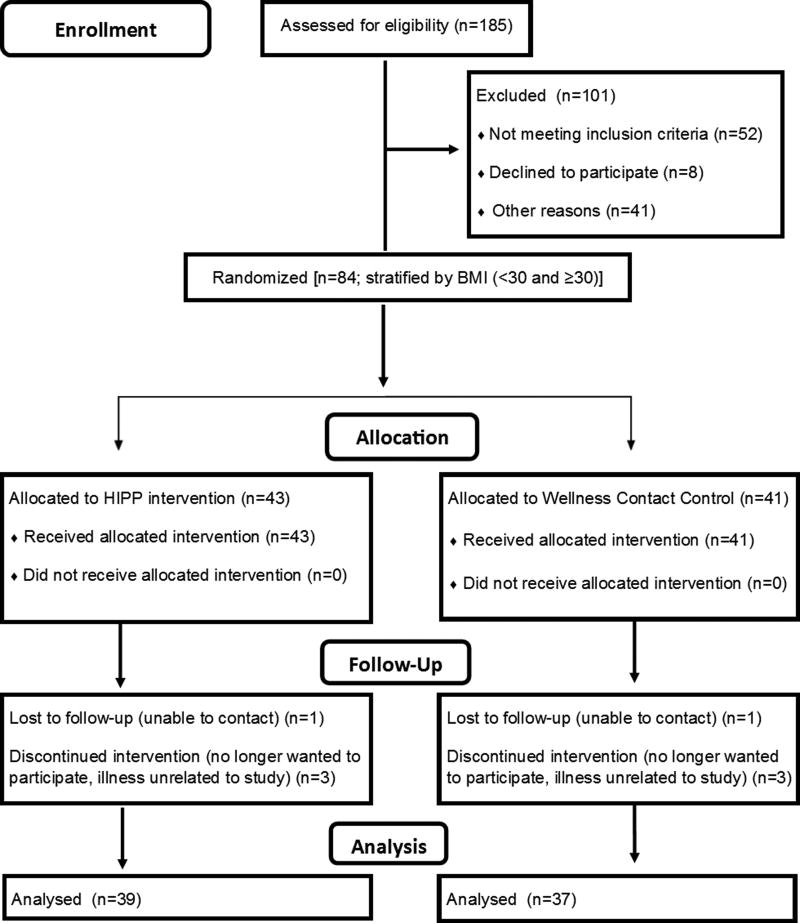

Recruitment, Retention, and Adherence

The sample was recruited within 12 months and the retention rate at six months was high (90%; see figure 1). As for adherence, 61% (51/84) of the sample returned at least 3 of the 4 required update surveys and 74% completed at least half of the required update surveys. Adherence decreased over time. While 63% and 60% of participants completed update surveys 1 and 2 (respectively), only 46% and 45% completed update surveys 3 and 4 (respectively.) No adverse events were reported related to this protocol.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Changes in physical activity from baseline to six months

HIPP intervention participants reported significant increases in minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA) from baseline to 6 months (M=+73.9 minutes/week, SD= 90.9, p <0.0001), as did the control group (+41.5 minutes/week, SD=64.4, p=0.0005). Between group analyses showed no statistical difference in MVPA between the two study groups (p=0.22) despite HIPP participants reporting an approximate 33-minute greater increase in MVPA than controls. Accelerometer data indicated similar physical activity trends, but showed more modest increases in levels of physical activity from baseline to six months than the self report data [M=+16.4 minutes per week (SD =57.5) for intervention arm, p=0.28; M= +1.8 (SD=42.3), p=0.85 for control arm]. Self-report- and accelerometer-measured physical activity data were significantly correlated at 6 months (Spearman’s rho = .36, p =0.006).

There were no significant differences in physical activity at 6 months among women with BMI <30 and ≥30 (for either condition). Specifically in the intervention arm, participants with BMI <30 (N=15) reported 108.47 minutes/week (SD=98.02) of at least moderate intensity physical activity at 6 months and participants with BMI ≥30 (N=28) reported 100.63 minutes/week (SD=80.58) of at least moderate intensity physical activity at 6 months, P=0.79. However, participants who were more adherent (completed at least 3 of the 4 required update surveys and thus received more relevant, tailored PA feedback) reported 113.6 minutes/week of moderate intensity or greater physical activity (SD= 92.61) at 6 months whereas those who were less adherent (completed less than 3 of the 4 required update surveys) reported 85.93 minutes/week (SD=74.26). Between group differences in physical activity among intervention participants who were more or less adherent were non-significant (p>.05), despite the more adherent intervention participants reporting approximately 28 more minutes/week of moderate intensity or greater physical activity than the less adherent intervention participants at six months.

Overall few participants (30.5%) reported engaging in strength and flexibility exercises at baseline with no differences between arms. Trends in the data indicate a general increase in strength and flexibility exercise over the 6 months. Overall 42.5% of participants reported engaging in strength and flexibility exercises at six months, including 47.2% of intervention arm and 37.8% of control arm. On average, time spent in strength and flexibility exercises significantly increased (+17.7 minutes/week, SD= 46.2, p=0.045) from baseline to six months for the intervention arm, but not for the control arm (+9.9 minutes/week, SD=48.2, p= 0.24). Moreover, 6-minute walk distance significantly declined from baseline to six months for the control arm (Mean change= −20.5 meters, SD= 51.9, p= 0.02), unlike the intervention arm. However, there were no significant between group differences in changes in strength and flexibility exercises, 6-minute walk distance, or weight from baseline to six months (p>.05). See Table 2 for changes from baseline to 6 months in physical activity measures.

Table 2.

Changes in physical activity and related variables from baseline to 6 months

| Intervention | Control | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Baseline Mean (SD) |

6 Month Mean (SD) |

Change Mean (SD) |

Baseline Mean (SD) |

6 Month Mean (SD) |

Change (SD) |

p |

| Self report MVPA (min/week, 10 minute bouts) | 35.1 (47.8) | 103.6 (86.5) | 73.9 (90.9)* | 48.2 (51.3) | 90.2 (71.6) | 41.5 (64.4)* | 0.22 |

| Accelerometer MVPA (min/week, 10 minute bouts) | 18.6 (40.1) | 31.5 (58.9) | 16.4 (57.5) | 19.1 (39.8) | 20.8 (38.2) | 1.8 (42.3) | 0.25 |

| Self report strength/flexibility exercise (min/week) | 6.1 (12.0) | 25.1 (46.46) | 17.7 (46.2) | 12.5 (26.0) | 20.7 (39.8) | 9.9 (48.2) | 0.93 |

| 6MWD (meters) | 377.7 (62.1) | 364.8 (54.7) | −15.1 (58.6) | 386.3 (54.5) | 367.4 (48.8) | −20.5 (51.9) | 0.92 |

| Weight (kg) | 85.1 (15.2) | 85.6 (13.9) | −0.01 (3.23) | 86.6 (13.80) | 87.4 (14.0) | 0.09 (3.47) | 0.76 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.4 (5.2) | 32.5 (4.7) | 0.02 (1.29) | 31.8 (5.2) | 31.9 (5.4) | 0.04 (1.26) | 0.93 |

p < 0.05 for within group change, paired t-test.

Changes in physical activity-related psychosocial variables from baseline to six months

The intervention group reported significantly greater improvements in physical activity goal-setting (M=+0.53, SD=0.87 vs. M=+0.08, SD=0.90; between group p=.02) and enjoyment (M=+8.38, SD= 29.09 vs. M=−7.32, SD=24.84; between group p=.04) from baseline to 6 months compared to the control group. There were no other significant between-group differences [physical activity planning, behavioral processes of change, stage of change]. However, trends in the data for cognitive processes of change, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and family support for physical activity indicated small improvements for the HIPP arm (P> .05) and declines for the control arm. Significant decreases in decisional balance (M=−0.49, SD=1.03, p=0.007) and friend support (M=−3.70, SD=8.62, p=0.03) for physical activity from baseline to six months were observed in the control arm and not the intervention arm. See table 3 for changes from baseline to 6 months in psychosocial measures.

Table 3.

Changes in psychosocial variables from baseline to 6 months

| Intervention | Control | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Baseline Mean (SD) |

6 Month Mean (SD) |

Change (SD) | Within group p |

Baseline Mean (SD) |

6 Month Mean (SD) |

Change (SD) | Within group p |

Between group p |

| Pros (range =1–5) | 4.25 (0.74) | 4.06 (0.84) | −0.22 (0.56) | 0.03* | 4.21 (0.82) | 3.78 (0.88) | −0.46 (0.73) | 0.0006* | 0.11 |

| Cons (range =1–5) | 2.23 (1.01) | 2.09 (0.98) | −0.12 (0.32) | 0.43 | 2.14 (0.87) | 2.05 (0.71) | 0.03 (0.82) | 0.82 | 0.74 |

| Decisional balancea | 2.02 (1.16) | 1.95 (1.13) | −0.11 (0.89) | 0.48 | 2.09 (1.14) | 1.75 (0.90) | −0.49 (1.03) | 0.007* | 0.15 |

| Cognitive processes (range =1–5) | 3.40 (0.79) | 3.45 (0.89) | 0.03 (0.65) | 0.75 | 3.50 (0.86) | 3.24 (0.83) | −0.19 (0.56) | 0.05 | 0.11 |

| Behavioral processes (range =1–5) | 3.17 (0.67) | 3.34 (0.69) | 0.16 (0.64) | 0.15 | 3.05 (0.71) | 3.01 (0.73) | 0.03 (0.54) | 0.73 | 0.15 |

| Self-Efficacy (range =1–5) | 3.11 (0.94) | 3.18 (0.88) | 0.04 (1.03) | 0.82 | 2.84 (1.01) | 2.73 (0.81) | −0.01 (0.81) | 0.94 | 0.12 |

| Goal setting (range =1–5) | 2.38 (0.90) | 2.85 (0.83) | 0.53 (0.87) | 0.001* | 2.38 (0.86) | 2.50 (0.96) | 0.08 (0.90) | 0.60 | 0.02* |

| Planning (range =1–5) | 2.48 (0.64) | 2.82 (0.70) | 0.39 (0.69) | 0.002* | 2.45 (0.52) | 2.63 (0.60) | 0.17 (0.41) | 0.02* | 0.09 |

| Outcome expectations (range =1–5) | 4.18 (1.06) | 4.39 (0.81) | 0.26 (1.32) | 0.25 | 4.26 (0.90) | 4.16 (0.62) | −0.07 (0.94) | 0.67 | 0.15 |

| Enjoyment (range=18–126) | 92.26 (23.78) | 101.05 (24.76) | 8.38 (29.09) | 0.09 | 99.46 (21.51) | 91.23 (22.71) | −7.32 (24.84) | 0.10 | 0.04* |

| Family support (range=10–50) | 25.56 (11.47) | 25.94 (10.74) | 0.42 (6.94) | 0.72 | 26.41 (10.61) | 23.81 (9.63) | −1.72 (11.01) | 0.37 | 0.33 |

| Friend support (range=10–50) | 22.49 (11.63) | 22.67 (11.21) | 0.06 (8.10) | 0.97 | 24.19 (12.28) | 19.49 (7.92) | −3.70 (8.62) | 0.034* | 0.07 |

| Rewards and punishments (range=3–15) | 4.61 (2.56) | 3.92 (1.57) | −0.61 (2.26) | 0.11 | 3.92 (1.7) | 3.95 (1.68) | 0.14 (2.35) | 0.72 | 0.54 |

p < 0.05 for within group change;

p <0.05 for between group change

scores<0 indicate more pros than cons for physical activity

Participant satisfaction

Ninety-two percent of intervention participants completed the satisfaction survey; of these, 91.7% reported being “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the HIPP intervention. The women endorsed reading most or all of the intervention print materials (80.6%) and found them helpful (91.7%) and enjoyable (86.1%). Most (97%) indicated that they gained knowledge about exercise by reading the intervention print materials and would recommend them to a friend. The women also reported wearing the pedometers often (91.7%) and found them helpful (87.9%). Finally, 100% of participants confirmed that the HIPP intervention was appealing and relevant to African American women in the Deep South and addressed their barriers to physical activity.

Discussion

Findings from the current study indicate the HIPP intervention has great potential as a low cost, high reach method for reducing physical activity-related health disparities. Post-intervention participant satisfaction data and the high retention rate at six months indicate that this approach was well-received by our sample. Moreover, the intervention produced larger increases in moderate intensity physical activity (approximately 33 more minutes per week) from baseline to six months than the control condition, along with significantly greater improvements in physical activity planning and enjoyment (key early indicators of behavior change).

Past research in this area with different populations has shown comparable physical activity outcomes. For example, in a study with a mostly White sample, the Tailored Print intervention participants reported a median of 112.5 minutes of physical activity per week at 6 months (compared to M=103.6, SD=86.5 in the current study) (18). However, a similar program resulted in less physical activity (M=73.36 minutes/week of at least moderate intensity activity, SD=89.73) at the 6-month follow-up for Latinas (17). That study also found lower overall baseline physical activity and less physical activity improvement from baseline to six months in the control condition than the current study. While there could be many reasons for such discrepancies, the protocols for the two studies differed in that the Latina participants underwent a 10-minute treadmill walk to demonstrate moderate intensity physical activity prior to the 7-Day Physical Activity Recall interviews. Given that live experiential demonstrations of a 10-minute bout of moderate intensity physical activity may result in more accurate reporting (15), future researchers in this area should consider adopting such protocols.

Despite our best efforts, several important TTM and SCT theoretical constructs were not improved by the intervention in the current pilot trial, whereas similar past studies in other populations have shown more success in targeting these variables with motivationally-tailored physical activity interventions. For example, significant intervention effects on self-efficacy, processes of change, decisional balance, and social support were found at 6 months and physical activity enjoyment and outcome expectations at 12 months in similar past studies with mostly White participants (25). Furthermore, studies with Latinas have shown significantly greater improvements in processes of change (29) and social support from family and friends (23) for physical activity from baseline to six months among Tailored print intervention vs. wellness control participants. Thus, future research in this area should focus on how to more effectively target those unchanged theoretical constructs in this at risk target population. Additional formative research may be needed to gain a more nuanced understanding of how these constructs work with African American women in the Deep South and further refine related physical activity intervention strategies and messages.

Strengths of the current study include the use of a randomized controlled research design, reliable and valid measures, and an intervention guided by strong behavioral theory and formative research within the target population. Limitations include a small sample comprised of community volunteers, which may limit the generalizability of the findings and our ability to find statistically significant results (26). Moreover, adherence rates were modest in the current study and showed signs of declining over time. The participants were asked to complete regular update surveys by mail at 6 weeks, 10 weeks, 4 months and 5 months and received $10 gift cards as incentives. For the intervention participants, survey responses were used by a computer expert system to generate individually tailored physical activity feedback reports on the previously mentioned SCT constructs. Thus, the intervention participants who completed the update surveys regularly received more relevant, up-to-date physical activity counseling messages and reported larger increases in physical activity than those who failed to do so. While these physical activity differences were not significantly different and the study was not sufficiently powered for those analyses (26), such trends in the data might argue for more attention to the timely completion of these repeat assessments. Several women noted on the participant satisfaction survey that the update surveys were too long; thus, streamlining the tailoring measures might improve future response rates.

Completing the update surveys online or via smartphone application could also facilitate this process. The current study relied on pen and paper questionnaires and mail delivery and keeping up with such paperwork may now be passé. However such design considerations were made according to participant preferences and feedback. Out of 61 total respondents in the current study, most (62.3%, N=38) reported preferring to received physical activity information via print materials in the mail rather than by Internet (N=22) or telephone (N=1). These subtotals do not include 8 participants who voted for more than one channel; specifically, 5 women expressed preferences for Internet and mail, 2 for mail and phone, and 1 for Internet, mail, and phone.

While print may have been the originally expressed preference, national data and survey responses from this sample indicate that the digital divide is shrinking (30). Of the 69 participants who responded in the current study, most had access to computer (93%) and Internet (97%) and reported having a Facebook, twitter, or other social media account (59%). All of these channels could be used to encourage participants to complete the update surveys needed to generate the individually tailored physical activity reports. Moreover, according to open-ended participant satisfaction item responses, participants desired more outreach, accountability, and interaction, which could also be provided through Internet and social media. Several participants even specified that email newsletters and Facebook groups would be helpful in future iterations of the HIPP intervention. Moreover, intervention messages from the current study focused on aerobic physical activity but participation in strength and flexibility exercises significantly increased from baseline to 6 months among intervention participants (and not control participants). Thus future studies incorporating strength and flexibility exercises would be more aligned with the national physical activity guidelines, which focus on both aerobic and strength exercises, and might be well received by this target population.

Overall, this study indicated that the HIPP intervention is a feasible, acceptable intervention tool for promoting physical activity among African American women in the Deep South, a group with high rates of inactivity and related health conditions. The HIPP intervention also produced modest increases in physical activity and some related psychosocial variables in the current study and most (97.2%) planned to continue exercising once the study ended. However, only 25.6% of the intervention group reported meeting national guidelines for aerobic physical activity at 6 months (vs. 21.6% for control). The lack of improvement in some psychosocial domains indicates that additional resources and supports (and more attention to strength and flexibility exercises) may be required to help this target population reach national guidelines.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the American Cancer Society (MRSG-13-156-01-CPPB), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001417), and National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (T32HL105349). Drs. David Allison, Mona Fouad, and Molly Bray provided substantial earlier contributions to the development of this study. Michelle Constant-Jones, Claudia Hardy, Tara Bowman, Jolene Lewis, and the staff at the Clinical Research Unit of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, as well as Rachelle Edgar of the University of California, San Diego, provided valuable research assistance on this project. Most importantly, we thank our study participants for their time.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation. The authors have no conflicts of interest or professional relationships with companies or manufacturers who will benefit from the results of the present study. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2016. [cited 2016 September 9]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-047079.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blair SN, Haskell WL, Ho P, et al. Assessment of habitual physical activity by a sevenday recall in a community survey and controlled experiments. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122(5):794–804. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butland RJA, Pang J, Gross ER, Woodcock AA, Geddes DM. Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. BMJ. 1982;284(6329):1607–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6329.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cahalin L, Pappagianopoulos P, Prevost S, Wain J, Ginns L. The relationship of the 6-min walk test to maximal oxygen consumption in transplant candidates with end-stage lung disease. Chest. 1995;108(2):452–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. PAR-Q and You. Vol. 1 Gloucester, Ontario: Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [[cited 2015 August 1]];National Center for Health Statistics, Health Data Interactive. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hdi.htm.2015.

- 8.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn AL, Garcia ME, Marcus BH, Kampert JB, Kohl HW, III, Blair SN. Six-month physical activity and fitness changes in Project Active, a randomized trial. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1998;30(7):1076–83. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199807000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications Inc accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(5):777–81. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedenreich CM, Cust AE. Physical activity and breast cancer risk: impact of timing, type and dose of activity and population subgroup effects. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42(8):636–47. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.029132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janz KF. Validation of the CSA accelerometer for assessing children’s physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(3):369–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendzierski D, DeCarlo KJ. Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale: Two Validation Studies. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 1991;13(1):50–64. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, et al. American Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(5):254–81. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.5.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen BA, Carr LJ, Dunsiger SI, Marcus BH. Effect of a moderate-intensity demonstration walk on accuracy of physical activity self-report. Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness. 2017;15(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jesf.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcus BH, Banspach SW, Lefebvre RC, Rossi JS, Carleton RA, Abrams DB. Using the stages of change model to increase the adoption of physical activity among community participants. Am J Health Promot. 1992;6(6):424–9. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.6.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcus BH, Dunsiger SI, Pekmezi DW, et al. The Seamos Saludables study: A randomized controlled physical activity trial of Latinas. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(5):598–605. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcus BH, Lewis BA, Williams DM, et al. A comparison of Internet and print-based physical activity interventions. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(9):944–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcus BH, Napolitano MA, King AC, et al. Telephone versus print delivery of an individualized motivationally tailored physical activity intervention: Project STRIDE. Health Psychol. 2007;26(4):401–9. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcus BH, Rakowski W, Rossi JS. Assessing motivational readiness and decision making for exercise. Health Psychol. 1992;11(4):257–61. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.4.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcus BH, Rossi JS, Selby VC, Niaura RS, Abrams DB. The stages and processes of exercise adoption and maintenance in a worksite sample. Health Psychol. 1992;11(6):386–95. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.6.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus BH, Selby VC, Nlaura RS, Rossi JS. Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise behavior change. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1992;63(1):60–6. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1992.10607557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marquez B, Dunsiger SI, Pekmezi D, Larsen BA, Marcus BH. Social Support and Physical Activity Change in Latinas: Results From the Seamos Saludables Trial. Health Psychol. 2016;35(12):1392–1401. doi: 10.1037/hea0000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melanson EL, Jr, Freedson PS. Validity of the Computer Science and Applications Inc (CSA) activity monitor. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(6):934–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papandonatos GD, Williams DM, Jennings EG, et al. Mediators of physical activity behavior change: findings from a 12-month randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2012;31(4):512–20. doi: 10.1037/a0026667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pekmezi D, Ainsworth C, Joseph R, et al. Rationale, design, and baseline findings from HIPP: A randomized controlled trial testing a home-based, individually-tailored physical activity print intervention for African American women in the Deep South. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;47:340–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pekmezi D, Jennings EG. Interventions to promote physical activity among African Americans. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2009;3:173–84. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pekmezi D, Marcus B, Meneses K, et al. Developing an intervention to address physical activity barriers for African-American women in the deep south (USA) Womens Health (Lond) 2013;9(3):301–12. doi: 10.2217/whe.13.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pekmezi DW, Neighbors CJ, Lee CS, et al. A culturally adapted physical activity intervention for Latinas: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pew Internet and American Life Project. [[cited 2013 January 5]];Demographics of Internet Users. Available from http://pewinternet.org/Static-Pages/Trend-Data-(Adults)/Whos-Online.aspx2013.

- 31.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390–33. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Resnick B, Zimmerman SI, Orwig D, Furstenberg A-L, Magaziner J. Outcome Expectations for Exercise Scale: Utility and Psychometrics. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2000;55(6):S352–S6. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.s352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richter DL, Wilcox S, Greaney ML, Henderson KA, Ainsworth BE. Environmental, policy, and cultural factors related to physical activity in African American women. Women Health. 2002;36(2):91–109. doi: 10.1300/j013v36n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rovniak LS, Anderson ES, Winett RA, Stephens RS. Social cognitive determinants of physical activity in young adults: a prospective structural equation analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(2):149–56. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev Med. 1987;16(6):825–36. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sevick MA, Napolitano MA, Papandonatos GD, Gordon AJ, Reiser LM, Marcus BH. Cost-effectiveness of alternative approaches for motivating activity in sedentary adults: results of Project STRIDE. Prev Med. 2007;45(1):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sloane R, Snyder DC, Demark-Wahnefried W, Lobach D, Kraus WE. Comparing the 7-day physical activity recall with a triaxial accelerometer for measuring time in exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(6):1334–40. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181984fa8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolin KY, Yan Y, Colditz GA, Lee IM. Physical activity and colon cancer prevention: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(4):611–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]