Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Resting energy expenditure (REE) increases following intense exercise; however, little is known concerning mechanisms.

PURPOSE

Determine effects of a single bout of moderate-intensity continuous aerobic exercise (MIC), or high intensity interval exercise (HII) on REE under energy balance conditions.

METHODS

Thirty-three untrained premenopausal women were evaluated at baseline, after 8–16 weeks of training, 22 hours following either MIC (50% peak VO2) or HII (84% peak VO2). Participants were in a room calorimeter during and following the exercise challenge. Food intake was adjusted to obtain energy balance across 23 hours. REE was measured after 22 hours following all conditions. Twenty-three hour urine norepinephrine concentration and serum creatine kinase activity (CrKact) were obtained. Muscle biopsies were obtained in a subset of 15 participants to examine muscle mitochondrial state 2, 3, and 4 fat oxidation.

RESULTS

REE was increased 22 hours following MIC (64±119 kcal) and HII (103±137 kcal). Markers of muscle damage (CrKact) increased following HII (9.6±25.5 units/liter) and MIC (22.2±22.8 units/liter) while sympathetic tone (urine norepinephrine) increased following HII (1.1±10.6 ng/mg). Uncoupled phosphorylation (states 2 and 4) fat oxidation were related to REE (respectively r=0.65 and r=0.55); however, neither state 2 or 4 fat oxidation increased following MIC or HII. REE was not increased following 8 weeks of aerobic training when exercise was restrained for 60 hours.

CONCLUSIONS

Under energy balance conditions REE increased 22 hours following both moderate intensity and high intensity exercise. Exercise-induced muscle damage/repair and increased sympathetic tone may contribute to increased REE whereas uncoupled phosphorylation does not. These results suggest that moderate to high intensity exercise may be valuable for increasing energy expenditure for at least 22 hours following the exercise.

Keywords: Interval Exercise, Uncoupled phosphorylation, Creatine kinase activity, Norepinephrine

Introduction

Low total daily energy expenditure is predictive of weight gain (49). The largest component of total energy expenditure is resting energy expenditure (REE), so habitual increases in REE may increase ease of weight maintenance. Fat free mass (FFM) has a large influence on REE, explaining 25–30% of its variance while fat mass normally explains less than 10% of the variation in REE (9). Other factors that may influence REE include variability in protein turnover due to muscle damage (14; 16; 19; 23; 30; 42), sympathetic tone (3), and uncoupled phosphorylation in adipose tissue (6; 7; 15) and/or muscle (39).

We (22; 46), as well as others (29; 37; 47), have shown that REE is increased for 18–24 hours following a high intensity aerobic exercise bout of at least 70% maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max). The increase in REE may be attributed to increased sympathetic tone induced by increased energy flux. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins (UCP) may contribute to REE since their expression may drive thermogenesis by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation. Studies in rodents demonstrate that moderate intensity aerobic exercise increases UCP1 expression in brown (51) and subcutaneous inguinal white adipose tissue (38). The increase in adipose tissue UCP1 expression is associated with physiologically relevant increases in REE which have been shown to attenuate weight gain regardless of dietary composition (8). However, evaluation of the effects of exercise on UCP1 in humans have been less promising with the suggestion that exercise does not increase UCP1 expression (48). While it is important to fully investigate the role of adipose tissue uncoupling of phosphorylation with exercise, the effects of exercise, on skeletal muscle, if any, are unclear. Several studies have suggested either no change or a decrease in skeletal muscle UCP3 content or uncoupled phosphorylation following chronic exercise training (11; 18; 35) or a single bout of exercise (15). We know of no studies that have attempted to determine the relative contribution of muscle damage, increased sympathetic tone, or changes in uncoupled phosphorylation to the increased REE following high intensity aerobic exercise.

In addition to muscle damage, sympathetic tone, allosteric metabolic regulators, uncoupled phosphorylation, and energy imbalance could be contributing to increased REE following aerobic exercise. Aerobic exercise may induce a temporary energy deficit, following a bout of exercise. An energy imbalance could contribute to increased REE (50). Furthermore, VO2max is related to REE independent of FFM, fat mass (FM), and 24-hour urinary norepinephrine (a surrogate of sympathetic tone) (22) suggesting a bout of exercise may affect REE. It is possible that the relationship between VO2max and REE is mediated by an acute energy imbalance following exercise. Although energy flux and REE assessed 22 hours after exercise are both decreased (10), no one has attempted to clamp energy balance following high intensity exercise to control for its potential confounding effects on REE following exercise.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether moderate intensity exercise as well as high intensity exercise influences REE under energy balance conditions. We also wanted to identify factors that might potentially be responsible for any increases in REE following the exercise. We hypothesize that under energy balance conditions; 1) Exercise training will not be associated with increased REE; 2) A bout of high intensity interval aerobic exercise will be associated with increased REE 22 hours after exercise but continuous moderate intensity aerobic exercise will not; 3) Changes in muscle damage, fat oxidation, mitochondrial uncoupling and sympathetic tone will be associated with differences in REE 22 hours following an acute bout of exercise.

Methods

Study Participants

Thirty-three women between 20–40 years of age participated in this study. Participants reported normal menstrual cycles and were not taking oral contraceptives or any medications known to influence glucose and/or lipid metabolism. Additional inclusion criteria were: i) normotensive; ii) non-smoker; iii) sedentary, as defined by participating in any exercise-related activities < 1× per week; and iv) normoglycemic as evaluated by postprandial glucose response to a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test. All participants provided written informed consent. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and conformed to the guidelines set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedures

After initial screening and fitness assessments, all participants were evaluated four times during the follicular phase of four different menstrual cycles. Participants stayed in a room calorimeter for the 23 hours prior to testing. The first evaluation was considered baseline. Post training evaluations took place after 8, 12, and 16 weeks of exercise training. The three post training evaluations were: 1) Following 60 hours of no exercise (NE, designed to evaluate the effects of chronic exercise training on REE); 2) ≈22 hours after one hour of continuous stationary cycle ergometry at 50% peak VO2 (MIC); and 3) ≈22 hours after one hour of interval stationary cycle ergometry at 84% peak VO2 (HII).

Work intervals for the HII condition were 144 seconds followed by 103 second stationary rest intervals (work and rest intervals were designed so the total work was matched with MIC). HII work and rest intervals were designed to produce identical cumulative work as the MIC condition, therefore the number of intervals performed were determined by this component of the experimental design. Post training assessments (NE, MIC and HII exercise each one month apart) were randomized to reduce the risk of bias by ordered effects. Forty-eight hours prior to testing, participants were required to abstain from any exercise or vigorous physical activity.

Food Intake

Food was provided the day prior to room calorimeter visits and during the days spent in the room calorimeter. Diets were prepared by the Clinical Research Unit kitchen staff and consisted of ≈60% energy as carbohydrates, ≈25% as fat, and ≈15% as protein. Macronutrient content of diet was held constant.

Energy Balance Clamp

One goal for having provided food was to try to achieve energy balance (energy intake matching energy expenditure) during the stay in the room calorimeter. Caloric intake during to room calorimetry visit was based on estimates generated from 330 doubly labeled water estimates of free living energy expenditure of sedentary premenopausal women collected in our lab. The equation was: Equation 1 = 750 kcal + [(31.47 FFM) − (.31 × fat mass) − (155 × race (race coded 1 for African American and 2 for European American)]. An equation for estimating the room calorimeter energy intake was developed from over 200 room calorimeter visits of premenopausal women Equation 2 = 465 kcal + [(27.8 FFM) − (2.4 × fat mass) − (188 × race (race coded 1 for African American and 2 for European American)]. Based on the anticipated energy expenditure of the exercise during the MIC and HII visits, the estimated energy cost of the exercise was added to the equation 2 result : Equation 3 = (equation 2 estimated energy expenditure + energy cost of MIC or HII exercise) [note the baseline and NE conditions did not have exercise so equation 3 was not used]). However, we recognized that the estimates may result in overfeeding or underfeeding individual subjects. Therefore, we developed a correction equation for the room calorimeter visit that was based on energy expenditure during the room calorimeter stay up to 5:30 pm. This equation was [Equation 4 = 9(390 kcal + average energy expenditure in kcal/min between 8:00 AM and 5:30 pm) × 925 kcal) − equation 3 estimate of energy expenditure]. We then adjusted the food intake of the evening meal to match the results of equation 4. The energy balance clamp was deemed affective since there were no significant differences in energy balance between the four conditions (mean values varying between −11 ±176 and −39±206) or significant difference from zero for any of the four conditions.

Exercise Training

After the baseline testing all participants aerobically exercise trained three times/week on a cycle ergometer for the duration of the 16-week study. Participants trained initially for 20 minutes at 65% of maximum heart rate and progressively increased their training until they were training continuously for 40 minutes at 80% of maximum heart rate by week four. Heart rate was monitored throughout each session by a Polar Vantage XL heart rate monitor (Polar Beat, Port Washington, NY). All sessions were under the supervision of an exercise physiologist in a training facility dedicated to research.

Peak Aerobic Capacity

Two to four days prior to each room calorimeter visit, peak aerobic capacity was measured. After an initial warm-up, participants completed a graded cycle ergometer test to measure peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) as determined by the highest level reached in the final stage of exercise. Power output began at 25 W and increased by 25 W every 2 minutes until participants reached volitional exhaustion. Sixty RPM cycle cadence was maintained throughout the test. Oxygen uptake, ventilation, and respiratory exchange ratio were determined by indirect calorimetry using a MAX-II metabolic cart (Physio-Dyne Instrument Company, Quogue, NY). Heart rate was continuously monitored by Polar® Vantage XL heart rate monitors (Polar Beat, Port Washington, NY). Although, we do not claim a true maximum oxygen uptake since tests were done on a cycle ergometer rather than treadmill, criteria for achieving a true maximum were heart rate within 10 beats of estimated maximum, RER of at least 1.1, and plateauing. All subjects reached at least one criteria and all but three subjects reached at least two criteria at each of the four test time points.

Room Calorimeter

Participants spent 23 h in a whole-room respiration calorimeter (3.38-m long, 2.11-m wide, and 2.58-m high) for measurement of total energy expenditure and REE. The design characteristics and calibration of the calorimeter were described previously (46). Oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production were continuously measured with the use of a magnetopneumatic differential oxygen analyzer (Magnos206; ABB, Frankfurt, Germany) and a nondispersive infrared industrial photometer differential carbon dioxide analyzer (Uras26, ABB, Frankfurt, Germany). The calorimeter was calibrated before each participant entered the chamber. Prior to each test, calibration was carried out on the oxygen and carbon dioxide analyzers using standard gases. The full scale was set for 0–1% for the carbon dioxide analyzer and 0–2% for the oxygen analyzer. Each participant entered the calorimeter at 0800 h. Metabolic data were collected throughout the 23h stay. Each participant was awakened at 0630 the next morning in the calorimeter. REE was then measured for 30 min before the subject left the calorimeter at 0700 h. Energy expenditure was calculated by the Weir equation (12). The REE data were extrapolated over 24 h and expressed as kcal/d for total energy expenditure and REE.

Twenty-two Hour Fractionated Urinary Norepinephrine

Unless multiple blood samples are taken during a day, 24-hour urine values are considered to be much more reflective of sympathetic tone over one day than blood samples (32; 43). Twenty-four-hour urine norepinephrine has been reported to be reliable (24) and valid for tracking chronic sympathetic activity (13). Therefore, we measured urine norepinephrine as a surrogate of sympathetic tone. Twenty-two hour urine samples were treated with hydrochloric acid and glutathione upon collection, and norepinephrine was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography. Serum levels of norepinephrine are incredibly labile, fluctuating dramatically over a short period.

Exercise Sessions in Room Calorimeter

Workload on the Collins electronically braked cycle ergometer was based on the VO2peak test using the cycle ergometer metabolic equation, in accordance with the American College of Sports Medicine (1). During the MIC exercise, participants cycled continuously for 60 minutes at an intensity of 50% VO2peak. Work intervals for the HII exercise were 144 seconds at 84% VO2peak, whereas the rest intervals were 103 seconds. Total work was identical among the two exercise bouts. Work-load was controlled outside the room calorimeter via a cable interface with the Collins electronically braked cycle ergometer (Warren E. Collins, Braintree, MA).

Body Composition

Total and regional body composition (i.e., fat mass and lean mass) was determined by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA; iDXA, GE-Lunar, Madison, WI). Participants were evaluated after an overnight fast three to four days prior to the room calorimeter visit and had not exercised for at least 36 hours, wore light clothing and remained supine with arms at the side but not touching the body in compliance with manufacture recommended testing procedures. Scans were analyzed by the same investigator with ADULT software, LUNAR-DPX-L version 1.33 (GE Medical Systems Lunar)

Tissue Biopsy and Preparation of Permeabilized Muscle Fibers

Twenty-three hours following the exercise challenge (MIC and HII conditions) or 60 hours following no exercise (Baseline and NE conditions) a subset of 15 women had muscle biopsies sampled (70–140 mg) from the vastus lateralus. Muscle biopsy samples were obtained from the lateral side of the vastus lateralis under local subcutaneous anesthesia (1% lidocaine) by percutaneous needle biopsy using a 5-mm Bergstrom needle under suction, as previously described (2). Each of the 4 biopsies were performed on the contralateral leg based on the prior biopsy and subsequent biopsies on the same leg were performed a minimum of one-inch distance from the prior biopsy with a minimum of 8 weeks in between. A portion of the biopsy sample was immediately placed and transported in an ice-cold relaxing and preservation solution BIOPS, containing (in mM) 2.77 Ca-EGTA buffer, 0.0001 free calcium, 50 K-MES, 7.23 K2EGTA, 20 imidazole, 0.5 DTT, 20 taurine, 5.7 ATP, 14.3 PCr, and 6.56 MgCl2-6 H2O (pH 7.1, 290 mOsm) (27; 33) and was used to prepare permeabilized muscle fiber bundles (PmFB). Briefly, small pieces of skeletal muscle (~20–25 mg) were placed immediately in fresh ice-cold BIOPS, trimmed of fat and connective tissue on ice, and separated into four small muscle bundles (~2–6 mg. wet weight). The PmFBs were mechanically separated by gentle blunt dissection with a pair of needle-tipped, anti-magnetic forceps under magnification (Zeiss, Stemi S2000-C Stereo Microscope, Diagnostic Instruments). They were then treated with 30 µg/ml saponin, gently rocked (Rocker II, model 260350, Boekel Scientific) at 4°C for 30 min in BIOPS.]. PmFBs were then rinsed twice by gentle rocking to wash out saponin and ATP at 4°C for at least 15 min and < 30 min, in MiR05 containing (in mM) 105 K-MES, 30 KCl, 1 EGTA, 10 K2HPO4, and 5 MgCl2-6 H2O, with 0.5 mg/ml BSA (pH 7.1, 290 mOsm). The PmFBs were then transferred to a fresh MiR05/creatine solution (500 µl) and blebbistatin (BLEB, 25µM).

High Resolution Mitochondrial Respirometry in Permeabilized Fibers

Mitochondrial respiration assays were performed using High Resolution Respirometry by measuring oxygen consumption in 2 mL of MiR05/creatine/blebbistatin buffer, in a two-channel respirometer (Oroboros Oxygraph-2k with DatLab software; Oroboros Instruments Corp., Innsbruck, Austria) with constant stirring at 750 rpm (28) and following a modified substrate-uncoupler-inhibitor titration (SUIT) protocol to evaluate respiratory control in a sequence of coupling and inhibitory states induced by multiple titrations in each assay (34). Seventy percent ethanol was run in both chambers for a minimum of 30 minutes, rinsed 3 × with Milli-Q ultrapure ddH2O, and the chambers were calibrated after a stable air-saturated signal was obtained before every experiment. Reactions were conducted with PmFB (2–8 mg wet weight) at 37°C with hyper-oxygenation to maintain oxygen concentrations above air saturation (~500–200 µM) (21) and prevent oxygen diffusion restrictions which have been shown to limit oxygen supply to the core of the fiber bundle (17). All experiments were completed before the oxygraph chamber [O2] reached 150 µM. Respiration rates were measured using malate (2 mM; anapleurotic intermediate) and palmitoylcarnitine (40uM) to determine mitochondrial β-oxidation per se with all electron transport chain complexes, independent of the step catalyzed by carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1B), which may differ across individuals and races (31). Polarographic oxygen measurements are expressed as picomoles per second times milligrams wet weight. Determination of state 2, 3 and 4 respiration rates were made in the presence of substrate alone (state 2; LEAK state; low ATP), after the addition of ADP (2mM; State 3; OxPhos State), and after inhibition of ATP synthase (Complex V) with oligomycin (State 4o; LEAK State; high ATP). For quality control and to ensure outer mitochondrial membrane integrity, cytochrome c (10 µM) was added to the assay after activation by ADP and only preparations with <10% increase after addition were included. Respiratory control ratios (RCRs) were determined as the ratio of State 3/State 4 respiration rates.

Myofiber Type Distribution

All visible connective and adipose tissues were removed from the biopsy samples with the aid of a dissecting microscope. Portions used for immunohistochemistry were mounted cross-sectionally on cork in optimum cutting temperature mounting medium mixed with tragacanth gum, frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane, and stored at −80°C. The relative distribution of myofiber types I, IIa, and IIx were determined by myosin heavy chain immunohistochemistry using our well-established protocol (26).

Serum Creatine Kinase Activity (CrKact)

Serum samples were stored at −80° C, only thawed once when the assay was performed, and only samples without any indication of hemolysis were used (45). The assay was performed in duplicate according the manufacturer’s instructions (Creatine Kinase Activity Assay Kit-MAK116, Sigma-Aldrich) and activity is reported in units/L. Two different samples were run in triplicate, used for quality control, and also for inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV). The inter-assay CVs were 4.1% and 7.0% and the intra-assay CVs were between 2.2% – 5.8%.

Statistics

Paired t-tests were used to evaluate baseline (pre-training) versus NE as well as ΔNE versus ΔMIC and ΔHII. Correlations were run between variables of interest and REE at baseline. SPSS Version 22 was used for all analysis and probability was set at < 0.05. Since no study has shown a decrease in state 3 fat oxidation (coupled phosphorylation) after exercise training and most studies show increased state 3 fat oxidation, a one tailed test of significance was used for the state 3 fat oxidation test between baseline and post training.

Results

Descriptive data are contained in Table 1. No significant differences were found between the NE condition and either MIC or HII for any of the descriptive variables. In addition, there was no significant time effect between 8 weeks, 12 weeks, and 16 week evaluations. Therefore, Table 1 contains only the contrasts between the baseline and NE. No significant changes between baseline and post training were observed except for a significant increase in FFM and VO2peak. Table 2 contains the results of the REE, muscle fiber type, muscle mitochondrial fat oxidation, and urinary norepinephrine for baseline and post training (chronic training effects). With the exception of state 2 and state 3 fat oxidation which increased significantly, no significant training induced changes were observed. CrKact is also shown for the post training value but CrKact was not measured at baseline.

Table 1.

Descriptive Variables. Comparison between Baseline and Post-Training

| Baseline | Post-Training | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32.6±5.5 | |||

| Height (cm) | 165.2±4.2 | |||

| Weight (kg) | N=38 | 74.1±14.6 | 74.2±14.7 | 0.73 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | N=38 | 27.2±5.1 | 27.2±5.2 | 0.91 |

| % Fat (kg) | N=37 | 37.9±6.8 | 37.5±6.7 | 0.18 |

| Fat Free Mass (kg) | N=37 | 44.1±5.7 | 44.7±5.8 | <0.02 |

| Fat Mass (kg) | N=37 | 28.1±9.1 | 27.8±8.9 | 0.50 |

| VO2peak (ml/kg/min) | N=38 | 25.3±6.1 | 27.0±6.0 | <0.01 |

Table 2.

Comparison between baseline and Post-Training, no acute exercise condition, for study outcome variables.

| Baseline | Post-Training | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy balance (kcal/d) | N=30 | −19.8±207 | −21.7±182 | 0.96 |

| Resting Energy Expenditure (kcal/d) | N=38 | 1503±221 | 1467±197 | 0.24 |

| Type I myofiber % | N=14 | 32.5±10.9 | 33.6±5.1 | 0.74 |

| Type IIA myofiber % | N=14 | 43.6±10.9 | 45.5±9.2 | 0.98 |

| Type IIX myofiber % | N=14 | 23.9±11.6 | 22.9±10.3 | 0.74 |

| State 2 Oxidation (pmole/g/mg ww) | N=14 | 2.95±2.11 | 4.01±1.80 | 0.05 |

| State 3 Oxidation (pmole/g/mg ww) | N=14 | 8.82±4.56 | 11.34±4.94 | 0.03 |

| State 4 Oxidation (pmole/g/mg ww) | N=14 | 3.90±2.7 | 4.52±2.37 | 0.24 |

| State 3/State 4 Oxidation Ratio | N=14 | 2.70±0.63 | 2.59±0.5 | 0.62 |

| Norepinephrine (ng/mg) | N=27 | 29.5±11.8 | 32.8±12.7 | 0.11 |

| CrKact (units/liter) | N=31 | 45.5±18.9 |

Energy balance = difference between energy consumed and energy burned for the day prior to measurement. State 2, 3, and 4 oxidation rates adjusted for muscle wet weight. CrKact was not measured at baseline.

Table 3 shows the differences that occurred 22 hours following the MIC and HII, MIC or HII different from NE (60 hours of no exercise). REE was significantly elevated compared to NE following both MIC and the HII, with a greater increase in HII compared to MIC. No significant changes in state 2, state 3, or state 4 mitochondrial fat oxidation occurred following either the MIC or HII. However, CrKact was significantly increased following both MIC and HII, with a greater elevation following HII. Twenty-four hour urinary norepinephrine concentrations were increased following only HII exercise,.

Table 3.

Difference between two acute exercise bouts and no exercise.

| MIC minus NE |

Probability Different from Zero |

N | HII Minus NE |

Probability Different from Zero |

N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Balance (kcal/day) | −11 ±176 | 0.65 | 33 | −39±206 | 0.27 | 33 |

| ΔResting Energy Expenditure (kcal/d) | +64±119 | <0.05 | 27 | +103±137 | <0.01* | 27 |

| ΔState 2 Fat Oxidation (pmole/g/mg) | +1.50±3.9 | 0.10 | 15 | +0.31±2.2 | 0.61 | 17 |

| ΔState 3 Fat Oxidation (pmole/g/mg) | +0.37±8.7 | 0.99 | 15 | −2.6±6.9 | 0.13 | 17 |

| ΔState 4 Fat Oxidation (pmole/g/mg) | −0.17±4.0 | 0.77 | 15 | +0.21±5.4 | 0.84 | 17 |

| State 3/State 4 Oxidation Ratio | +0.54±1.8 | 0.29 | 15 | +0.09±0.9 | 0.67 | 17 |

| ΔCrKact (units/liter) | + 9.6±25.5 | <0.03 | 27 | +22.2±22.8 | <0.01* | 27 |

| ΔNorepinephrine (ng/mg) | +1.1±10.6 | 0.70 | 22 | +5.3±14.4 | <0.04 | 23 |

CrKact = creatine kinase activity.

Significantly different from MIC, P <0.05.

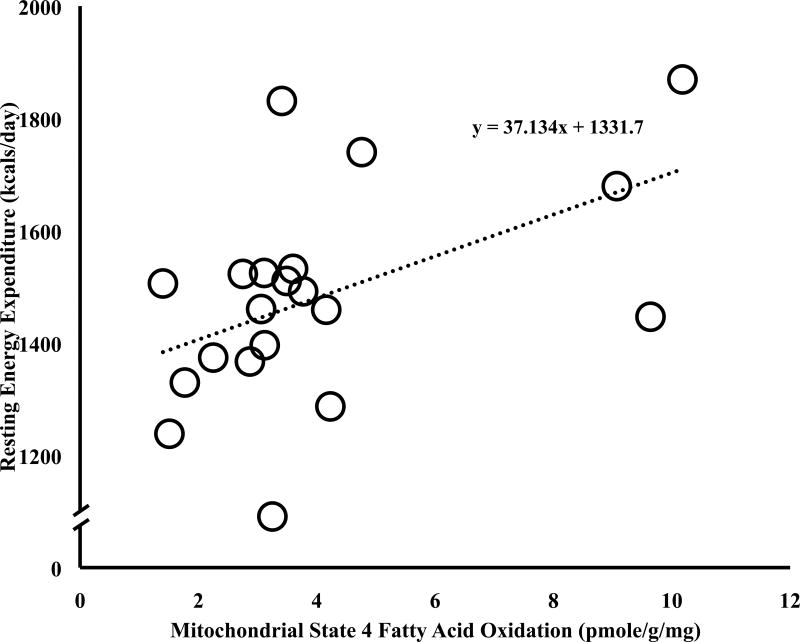

State 2 (r=0.65, P<0.01) and 4 (r=0.55, P=0.02) mitochondrial fat oxidation rates were significantly related to REE at baseline (State 4 mitochondrial fat oxidation rates and REE relationship depicted in Figure 1). Muscle fiber type was not related to resting energy expenditure or change in REE, except that type IIA muscle fiber type was significantly related to increase in REE following HII (r = 0.65, p < 0.04). No significant correlations were observed between percent fiber type with state 2, state 4, or the ratio of state 3 to state 4 at baseline. However, significant correlations between percent type I muscle fiber type and the ratio of state 3 to state 4 mitochondrial fat oxidation and percent type IIA fiber type and state 2 fat mitochondrial fat oxidation were observed after the HII. None of the changes in mitochondrial fat oxidation variables were significantly related to change in REE.

Figure 1.

Relationship between baseline REE and state 4 mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation at baseline (r = 0.55, P= 0.02).

Discussion

Our observation that REE increased over 100 kcal 22 hours after the high intensity exercise is consistent with a number of other studies (22; 29; 37; 46; 47). The primary observation of this study that is unique is that under energy balance conditions, REE increased following both the HII and MIC exercise although the increase following HII was larger. Since both 24-hour urine norepinephrine and serum CK activity increased following HII, we suggest increased sympathetic tone and protein repair following HII may be contributing to increased energy expenditure. Although mitochondrial State 2, State 3, and State 4 lipid oxidation rates were related to REE at baseline (Figure 1), no 22-hour post exercise changes were noted following a bout of HII or MIC. Nor were delta mitochondrial lipid oxidation rates following HII related to delta REE, suggesting that intrinsic mitochondrial β-oxidation per se may be involved in REE but not cause the increase noted following high intensity exercise, at least at 22 hours following exercise.

Rolfe and Brand proposed that mitochondrial protein leak uncoupled to ATP synthesis accounts for as much as 50% of resting skeletal energy expenditure (40), which is thought to be regulated by uncoupling proteins (UCPs), particularly UCP2 and UCP3 (5; 41). So, variations in mitochondrial uncoupling may be associated with variability in total resting energy expenditure. Indeed, this has been shown to be the case at least in rats (39). Consistent with this we show a relationship between state 2 and state 4 fat oxidation and resting energy expenditure in this study (see Figure 1). Several studies, have shown decreases in UCP3 protein or mRNA (6; 15; 35) and uncoupled respiration (15) following exercise training, while others have shown increases (36; 44). Consistent with the studies that showed increases we show a significant increase in state 2 fat oxidation and a trend for an increase in state 4 fat oxidation. However, similar to results reported by Jones et al (25) the increase in state 2 and state 4 fat oxidation matched the relative increase in state 3 fat oxidation indicating that the increase was a function of increased mitochondrial biogenesis.

We had hypothesized that uncoupled mitochondrial fat oxidation may contribute to increased REE following a bout of high intensity. Although, Fernstrom et al (15) found a decrease in uncoupled respiration 3 hours following a bout of moderate intensity exercise, no one had previously observed what effect high intensity interval exercise had on fat oxidation uncoupling 22 hours following the exercise. We found no significant differences in delta state 2 fat oxidation, delta state 4 fat oxidation, nor the ratio of state 3 to state 4 fat oxidation with delta REE for either the contrast between the HII or MIC with NE. In addition, there was no relationship between any of the post training delta fat oxidation measures and delta REE. These observations suggest that changes in uncoupled mitochondrial fat oxidation did not contribute to increased REE following either moderate intensity or high intensity exercise.

Hesselink and colleagues have previously reported that type II muscle fibers contain more UCP3 than type I muscle fibers (20), suggesting type II muscle fibers may be more prone to uncouple oxidative phosphorylation than type I muscle fibers. However, we saw no significant relationships between fiber type, change in mitochondrial uncoupling or change in REE. It does not appear the percent muscle fiber type contributes substantially to variations in REE.

A unique approach to our work was the implementation of an energy balance clamp. By managing energy balance, the differences observed between conditions appear to be independent of either an energy surplus or energy deficit, thus isolating the exercise-mediated effect. Increased REE following the moderate intensity exercise was an unexpected finding. To our knowledge previous studies have not found an increase in REE for aerobic exercise intensities less than 70% VO2peak. However, this is the first study to attempt to clamp energy balance following exercise and it is known that energy deficit can decrease REE (50). Little is known about the short term effects of energy imbalance, although, it is known that longer term energy imbalance (for example two weeks) will decrease REE (50). It is possible that in some of the previous studies (29; 37; 47); 20; 36) the bout of exercise may have induced a temporary energy imbalance and induced a reduction in REE, concealing a modest increase in REE following the moderate intensity exercise. Consistent with this being the case, we found a significant relationship between energy balance and REE at baseline supporting the notion that even small deviations in energy balance for as little as 22 hours may influence REE. It is important to note that the REE increase with MIC in the present study was less than following the HII condition (+64 versus +103 kcal/day). Increased sympathetic tone possibly contributed to the increase in REE with HII, since HII induced an increase in urinary norepinephrine. No increase in urinary norepinephrine occurred with MIC suggesting a threshold of exercise intensity exists when identical work is performed to elevate sympathetic tone. The increase in CrKact following the MIC was also surprising since the participants should have been well conditioned for the 50% VO2peak exercise, as they had been training 8–16 weeks at 70% VO2peak. Although the duration of exercise was longer (60 minutes for the MIC trial versus 40 minutes for normal training), it was at a lower intensity. It is also important to note that the cycling exercise modality is considered to have little eccentric work, contractions which are more likely to cause muscle damage and protein turnover (4). This suggests that the current participants likely experienced less overall muscle damage compared to what may be observed during an alternative exercise modality (i.e. running) that incorporates more eccentric contractions. The relatively modest CrKact increases support this (45). Subsequent studies may measure the current outcomes using treadmill running or comparing low- and high-volume/intensity resistance exercise protocols to examine the mechanisms behind REE differences. This could supplement the current findings and perhaps speak to future physical activity/exercise recommendations in individuals and populations looking to maximize to REE.

The findings of this study are specific to premenopausal women. Although, it is probable the findings may be consistent with older women and men. Further research is warranted to confirm this. We recognized that the estimates of food intake may result in overfeeding or underfeeding individual subjects. Therefore, we developed a correction equation for the room calorimeter visit that was based on energy expenditure during the room calorimeter stay up to 5:30 pm. We then adjusted the food intake of the evening meal to match the results of equation 4. There were no significant differences in energy balance between the four conditions (mean values varying between −11 ±176 and −39±206).

In conclusion, REE was increased 22 hours following a bout of cycling exercise by over 100 kcal/day following high intensity exercise and over 60 kcal/day following moderate intensity exercise in aerobically trained women in energy balance. This increase in REE was accompanied by increased markers of muscle damage and sympathetic tone following the HII exercise and muscle damage following the MIC exercise. Whereas, increased uncoupled mitochondrial fat oxidation did not increase following either HII or MIC suggesting no contribution to increased REE. No increase in REE was observed following 8 weeks of aerobic training when subjects restrained from exercise for 60 hours. These results suggest that if increased REE is the goal of aerobic exercise training, periodic bouts of exercise training must occur regularly throughout the week. This in turn may enable better weight maintenance and potentially offset weight gain which may improve metabolic health. Indeed, the combination of energy expenditure from the exercise plus the increase in REE following the exercise may enable individuals to do a better job of remaining in energy balance and avoid weight gain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grants R01 AG027084-01, R01 AG027084-S, R01 DK56336, P30 DK56336, P60 DK079626, UL 1RR025777. The results of this study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

The authors thank David Bryan, Bob Petri, and Paul Zuckerman for help in data acquisition.

Footnotes

There is not conflict of interest for any of the authors.

References

- 1.American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Williams; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bamman MM, Clarke DL, Feeback DL, Talmadge RJ, Stevems BR, Lieberman SA, Greenisen MC. Impact of resistance exercise during bed rest on skeletal muscle sarcopenia and myosin isoform distibution. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:157–163. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell C, Seals DR, Monroe MB, Day DS, Shapiro LF, Johnson DG, Jones PP. Tonic sympathetic support of metabolic rate is attenuated with age, sedentary lifesyle, and female sex in healthy adults. J Clin Endocri Metab. 2001;86:4440–4444. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.7855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bijker KE, de Groot D, Hollander AP. Differences in leg muscle activity during running and cycling in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2002;87:556–561. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0663-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boss O, Hagen T, Lowell BB. Uncoupling roteins 2 and 3: potential regulators of mitochondrial energy metabolism. Diabetes. 2000;49:143–149. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boss O, Samec S, Desplanches D, Mayet MH, Sydoux JMP, Giacobino JP. Effect of endurance training on mRNA expression of uncoupling proteins 1, 2, and 3 in the rat. FASEB. 1998;12:335–339. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bostrom P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, Korde A, Ye L, Lo JC, Rasbach KA, Bostrom EA, Choi JH, Long JZ, Kajimura S, Zingaretti MC, Vind BF, Tu H, Cinti S, Hejlund K, Gygi P, Spiegelman BM. A PGC1a-dependent myokine that drives browning of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481:463–468. doi: 10.1038/nature10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bostrom P, Wu J, Jedrychowski MP, Korde A, Ye L, Lo JC, Rasbach KA, Bostrom EA, Choi JH, Long JZ, Kajimura S, Zingaretti MC, Vind BF, Tu HCS, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM. A PGC1-á-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481:463–468. doi: 10.1038/nature10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brock DW, Tompkins CL, Fisher G, Hunter GR. Influence of resting energy expenditure on blood pressur is independent of body mass and a marker of sympathetic tone. Metab: Clin Exper. 2012;61:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullough RC, Gillette CA, Harris MA, Melby CL. Interaction of acute changes in exercise energy expenditure and energy intake on resting metabolic rate. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:473–481. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conley KE, Amara CE, Baipeyi S, Costford SR, Murray K, Jubrias SA, Arakaki L, Marcinek DJ, Smith SR. Higher mitochondrial respiration and uncoupling with reduced electron transport chain content in vivo in mscle of sedentary versus activie subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:129–136. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Weir JB. New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J Physiol. 1949;109:1–9. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimsdale JE, Ziegler MG. What do plasma and urinary measures of catecholamines tell us about human response to stressors? Circulation. 1991;83:11–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolezal BA, Potteiger JA, Jacobsen DJ, Benedict SH. Muscle damage and resting metabolic rate after acute resistance exercise with an eccentric overload. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;7:1202–1207. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernstrom M, Tonkonogi M, Sahlin K. Effects of acute and chronic endurance exercise on mitochondrial uncoupling in human skeletal Muscle. J Physiol. 2003;554.3:765–763. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillette CA, Bullough RC, Melby CL. Postexercise energy expenditure in response to acute aerobic or resistive exercise. Intern J Sports Nutri. 1994;4:347–360. doi: 10.1123/ijsn.4.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gnaiger E. Capacity of oxidative phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle: new perspectives of mitochondrial physiology. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1837–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gnaiger E, Boushel R, Sundergaard H, Munch-Andersen T, Damsgaard RHC, Diez-Sanchez C, Ara I, Wright-Pardis C, Schrauwen P, Hesselink M, Calbet JAL, Christiansen M, Hedge JW, Saltin B. Mitochondrial coupling and capacity of oxidative phosphorylation in sskeletal muscle of Inuit and Caucasians in the artic winter. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25:126–134. doi: 10.1111/sms.12612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hackney KJ, Engels HJ, Gretebeck RJ. Resting energy expenditure and delayed-onset muscle soreness after full-body resistance training with an eccentric concentration. J Str Cond Res. 2008;22:1602–1609. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31818222c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hesselink MG, Keizer HA, Borhouts LB, Schaart G, Kornips CF, Slieker LJ, Sloop KW, Saris WH, Schrauwen P. Protein expression of UCP3 differs between human type 1, type 2a, and type 2b fibers. FASEB J. 2017;15:1071–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughey CC, Hittel DS, Johnsen VL, Shearer J. Respirometric oxidative phosphorylation assessment in saponin-permeabilized cardiac fibers. J Vis Exp. 2011;48:1–7. doi: 10.3791/2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter GR, Byrne NM, Gower BA, Sirikul B, Hills AP. Increased resting energy expenditure after 40 minutes of aerobic but not resistance exercise. Obesity. 2006;14:2018–2025. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jamurtas AZ, Koutedakis Y, Paschalis V, Tofas T, Yfanti C, Tsiokanos A, Koukoulis G, Kouretas D, Loupos D. The effects of a single boout of exercise on resting energy expenditure and respiratory exchange ratio. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;92:393–398. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenner DA, Harrison GA, Prior IAM, Leonetti DL, Fujimoto WY. 24-h catecholamine excretion: relationships with age and weight. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;164:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(87)90103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones TE, Baar K, Chen M, Holloszy JO. Exercise induces an increase in muscle UCP3 as a component of the increase in mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:E96–E101. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00316.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JS, Kosek DJ, Petrella JK, Cross JM, Bamman MM. Resting and load-induced levels of myogenic gene transcripts differ between older adults with demonstrable sarcopenia and youmg men and women. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:2149–2158. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00513.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuznetsov A, Gnaiger E. High resolution respirometry with permeabilized muscle fibers. Mitochon Physiol Net. 2003;4.7:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuznetsov AV, Veksler V, Gellerich FN, Saks V, Margreiter R, Kunz WS. Analysis of mitochondrial function in situ in permeabilized muscle fibers, tissues and cells. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:965–976. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maehlum S, Gradmontagne M, Newsholme E, Sjostrom OM. Magnitude and duration of excess postexercise oxygen consumption in healthy young subjects. Metabolism. 1986;35:425–429. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melby C, Scholl C, Edwards G, Bullough R. Effect of acute resistance exercise on postexercise energy expenditure and resting metabolic rate. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:1847–1853. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.4.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miljkovic I, Yerges LM, Li H, Gordon CL, Goodpaster BH, Juller LH, Nestlerode CS, Bunker CH, Patric ALWVW, Zmuda JM. Association of the CPT1B gene with skeletal muscle fat infiltration in Afro-Caribbean men. Obesity. 2009;17:1396–1401. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peaston RT, Weincove C. Measurement of catecholemines and their metabolites. Ann Clin Biochem. 2004;41:17–36. doi: 10.1258/000456304322664663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perry CG, Kane DA, Kubm CT, Kozy R, Cathey BL, Lark DS, Kane CL, Brophy PM, Gavin PM, Anderson EJ, Neufer PD. Inhibiting myosin-ATPase reveals a dynamic range of mitochondrial respiratory control in skeletal muscle. Biochem J. 2011;437:215–222. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pesta D, Gnaiger E. High-resolution repiratory OXPHO5 protocols for human cell cultures and permeabilized fibres from small biopsies of human muscle. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;810:25–58. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-382-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peterson JM, Bryner RW, Frisbee JC, Alway SE. Effects of exercise and obesity on UCP3 content in rat hindlimb muscles. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:1616–1622. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817702a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pilegaard H, Ordway GA, Saltin B, Neufer PD. Transcriptional regulation of gene expression in human skeletal muacle during recovery from exercise. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:E806–E814. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.4.E806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poehlman ET, Danforth E. Endurance training increases metabolic rate and norepinephrine appearance rate in older individuals. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:E233–E239. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.2.E233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rocha-Rodriques S, Rodriquez A, Gouveia AM, Concalves IO, Becerril SRB, Beleza J, Frohbeck G, Ascensao A, Magelhaes J. Effects of physical exercise on myokines expression and brown adipose-like phenotype modulation in rats fed a high-fat diet. Life Sci. 2016;165:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rolfe DF, Brand MD. Contribution of mitochondrial protein leak to skeletal muscle respiration and to standard metabolic rate. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C1380–1389. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.4.C1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rolfe DF, Brand MD. Proton leak and control of oxidative phosphorylation in perfused, resting rat skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1276:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schrauwen P, Xia J, Bogardus C, Pratley RE, Ravussin E. Muscle uncoupling protein 3 expression is a determinant of energy expenditure in Pima Indians. Diabetes. 1999;48:146–149. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuenke MD, Mikat RP, McBride JM. Effect of an acute period of resistance exercise on excess post-exercise oxygen consumption: implications for body mass management. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2002;86:411–417. doi: 10.1007/s00421-001-0568-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thayer JF, Fischer JE. Heart rate variability, overnight urinary norepinephrine and C-reactive protein: evidence for the cholinrgic anti-inflamatory pathway in healthy adults. J Int Med. 2009;265:439–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tonkonogi M, Krook A, Walsh B, Sahlin K. Endurance training increases stimulation of uncoupling of skeletal muscle mitochondria in humans by non-esterified fatty acids: an uncoupling-protein-mediated effect? Biochem J. 2000;351:810. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Totsuka M, akaji S, Suzuki K, Sugawara K, Sato K. Break point of serum creatine kinase release after endurance exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1280–1286. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01270.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Treuth MS, Hunter GR, Williams M. Effects of exercise intensity on 24-h energy expenditure and substrate oxidation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28:1138–1143. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199609000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Pelt RE, Jones PP, Davy KP, Desouza CA, Tanaka H, Davy BM, Seals DR. Regular exercise and the age-related decline in resting metabolic rate in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3208–3212. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.10.4268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vosselman Mj, Hoeks J, Brans B, Pallubinsky H, Nascimento EB, van der Lans AA, Boeders EP, Mottaghy FM, Schrauwen P, van Marken LWD. Low brown adipose tissue activity in endurance-trained compared with lean sedentary men. Int J Obes. 2015;39:1696–1702. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinsier RL, Hunter GR, Desmond RA, Byrne NM, Zuckerman PA, Darnell BE. Free-living activity energy expenditure in women successful and unsuccesful at maintaining a normal body weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:499–504. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weinsier RL, Nagy TR, Hunter GR, Darnell BE, hensrud DD, Weiss HL. Do adaptive changes in metabolic rate favor weight regain in weight-reduced individuals? An examination of the set-point theory. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1088–1094. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu X, Ying Z, Cai M, Xu Z, Li Y, Jiang SY, Tsan K, Wang A, Parthasarathy S, He G, Rajagopalan S, Sun Q. Exercise ameliorates high-fat diet-induced metabolic and vascular dysfuction, and increases adipocyte progenitor cell population in brown adipose tissue. Am J Physiol. 2011;300:R1115–R1125. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00806.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]