Abstract

Anti-VEGF drugs that are used in conjunction with laser ablation to treat patients with diabetic retinopathy suffer from short half-lives in the vitreous of the eye resulting in the need for frequent intravitreal injections. To improve the intravitreal half-life of anti-VEGF drugs, such as the VEGF decoy receptor sFlt-1, we developed multivalent bioconjugates of sFlt-1 grafted to linear hyaluronic acid (HyA) chains termed mvsFlt. Using size exclusion chromatography with multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS), SDS-PAGE, and dynamic light scattering (DLS), we characterized the mvsFlt with a focus on the molecular weight contribution of protein and HyA components to the overall bioconjugate size. We found that mvsFlt activity was independent of HyA conjugation using a sandwich ELISA and in vitro angiogenesis assays including cell survival, migration and tube formation. Using an in vitro model of the vitreous with crosslinked HyA gels, we demonstrated that larger mvsFlt bioconjugates showed slowed release and mobility in these hydrogels compared to low molecular weight mvsFlt and unconjugated sFlt-1. Finally, we used an enzyme specific to sFlt-1 to show that conjugation to HyA shields sFlt-1 from protein degradation. Taken together, our findings suggest that mvsFlt bioconjugates retain VEGF binding affinity, shield sFlt-1 from enzymatic degradation, and their movement in hydrogel networks (in vitro model of the vitreous) is controlled by both bioconjugate size and hydrogel network mesh size. These results suggest that a strategy of multivalent conjugation could substantially improve drug residence time in the eye and potentially improve therapeutics for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy.

Keywords: hyaluronic acid, anti-VEGF drug, angiogenesis, drug delivery

1. Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy is one of the most detrimental consequences of diabetes, which imposes enormous healthcare costs in the U.S. and worldwide, and affects over 25 million American adults. Within two decades of their initial diagnosis, all patients with diabetes type I and 60% of patients with diabetes type II will exhibit symptoms of DR [1]. The main mediator of retinal neovascularization in diabetic retinopathy is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which is upregulated by hypoxic neurons in the retina [2–4]. Elevated intravitreal levels of VEGF results in the aberrant growth of blood vessels with loose cell-cell junctions leading to areas of vision loss caused by pooled blood and edema in and around the macula [5]. The reference-standard treatment for DR is pan-retinal laser photocoagulation (PLP), which forestalls retinal neovascularization by destroying ischemic neurons and reducing the number of VEGF-producing cells in the retina [6]. While this therapy can reduce the risk of disease progression and severe vision loss, the best outcomes for improved visual acuity occur when PLP is used in combination with anti-angiogenic therapies [7], as intravitreal VEGF remains elevated even after treatment by PLP [8].

The most commonly used anti-VEGF therapies for DR are Lucentis (ranibizumab, Genentech, a 48 kDa humanized antibody fragment) [9], Avastin (bevacizumab, Genentech, a 150 kDa humanized antibody) [10], and Eylea (aflibercept, Regeneron, a 110 kDa VEGF-receptor fusion protein) [11]. Due to limited drug retention in the vitreous as a result of their small molecular size, a single administration of these drugs provides only a limited therapeutic benefit for a finite period of time. In order to maintain an effective drug dose in the vitreous to inhibit VEGF-mediated retinal neovascularization, patients require monthly injections. Consequently, low patient compliance to these treatment protocols continues to be the most significant factor limiting the ability of anti-VEGF treatments to maintain improvements in visual acuity [12,13]. Therefore, novel approaches are required to enhance the half-life of anti-VEGF therapies within the vitreous, which would in turn reduce the frequency of required intravitreal drug injections and improve patient quality of life.

In this work, we describe a novel multivalent drug bioconjugate composed of the anti-angiogenic VEGF decoy receptor sFlt-1, and hyaluronic acid (HyA), a naturally occurring biopolymer present in high concentrations throughout the body and in particular within the vitreous of the eye [14]. The overall goal of this study was to create high-molecular weight multivalent bioconjugates of sFIt (mvsFIt) that were capable of binding and inhibiting VEGF165 activity in vitro, improving protein stability, and increasing mvsFIt residence time over unconjugated sFIt. For the latter, we modeled the vitreous in vitro using a cross-linked hyaluronic acid hydrogel and observed that mvsFIt bioconjugates diffused slower and had reduced mobility in comparison to unconjugated sFIt. We anticipate that the future clinical use of multivalent conjugates of sFIt may significantly increase the intravitreal drug residence time and inhibit retinal angiogenesis over a longer period of time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Expression of Soluble Flt-1(3) Receptor

The sFlt-1 sequence for the first 3 lg-like extracellular domains of sFlt-1 (3) [15] was cloned into the pFastBac1 plasmid (Life Technologies) and then transformed into DH10Bac E.coli, which were plated on triple antibiotic plates containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL), gentamicin (7 μg/mL, Sigma Aldrich), tetracycline (10 μg/mL, Sigma Aldrich), IPTG (40 μg/mL, Sigma Aldrich) and Bluo-gal (100 μg/mL, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The sFlt-1 (3) gene-containing bacmid was isolated from DH10Bac E.coli (Life Technologies) and transfected into SF9 insect cells for virus production (provided by the Tissue Culture Facility, UC Berkeley). Virus was then used to infect High Five insect cells (provided by the Tissue Culture Facility, UC Berkeley) to induce sFlt-1 (3) protein expression. After 3 days, protein was purified from the supernatant using Ni-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen Laboratories). Recombinant sFlt-1(3) was eluted from the Ni-NTA beads using an imidazole gradient and then concentrated and buffer exchanged with 10% glycerol/PBS using Amicon Ultra-15mL Centrifugal devices (EMD Millipore). The protein solution was sterile filtered and the concentration was determined using a BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The molecular weight of sFlt-1(3) was determined from a 4-20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel. For convenience, we refer to this protein as sFlt in this manuscript.

2.2. mvsFlt Conjugate Synthesis

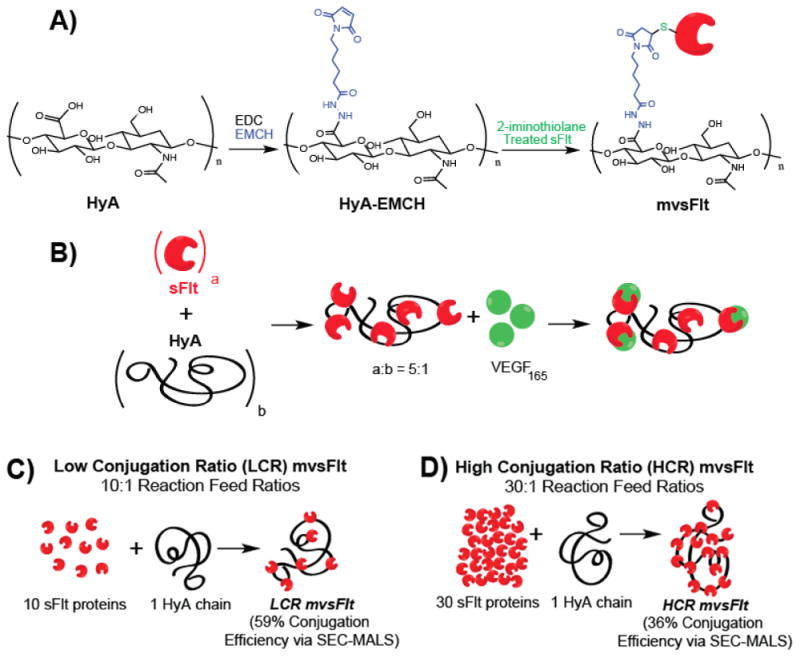

Hyaluronic acid with manufacturer reported molecular weights of 300 kDa, 650 kDa and 1 MDa were purchased from LifeCore Biomedical, where the molecular weights were determined by viscosity. Conjugation of sFlt to HyA was carried out according to the schematic in Figure 1A, as previously described [16–18]. To make thiol-reactive HyA intermediates, 3,3′-N-(ε-maleimidocaproic acid) hydrazide (EMCH, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1.2 mg/mL), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate (HOBt, Sigma Aldrich, 0.3 mg/mL) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10 mg/mL) were added to a 3 mg/mL solution of HyA (Lifecore Biotechnology) of various molecular weights in 0.1 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulphonic acid (MES) (Sigma Aldrich) buffer (pH 6.5) and allowed to react at 4 °C for 4 hours. The solution was then dialyzed into pH 7.0 PBS containing 10% glycerol. Recombinant sFlt was treated with 10 molar excess of 2-iminiothiolane to sFlt to create thiol groups for conjugation to the maleimide group on EMCH. The degree of thiolation was determined using Ellman's reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). sFlt was then added to activated HyA-EMCH at 10:1 and 30:1 molar ratios of sFlt to HyA to create the mvsFlt bioconjugates and allowed to react at 4 °C overnight. The mvsFlt reactions were dialyzed exhaustively using 100 kDa molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) Float-A-Lyzer G2 (Spectrum Labs) dialysis tubes in pH 7.0 PBS to remove unreacted sFlt. The BCA assay was used to measure the protein concentrations of the mvsFlt bioconjugates. We defined conjugates with 10:1 sFlt to HyA molar feed ratios as ‘low conjugation ratio’ (LCR) mvsFlt and 30:1 molar feed ratios ‘high conjugation ratio’ (HCR) mvsFlt.

Figure 1. Multivalent sFlt synthesis and schematics.

A) mvsFlt bioconjugates were synthesized using a 3-step reaction in which HyA was reacted with EDC and EMCH to create a cysteine reactive HyA-EMCH intermediate. sFlt was then treated with 2-iminothiolane and then reacted with the HyA-EMCH intermediate for the synthesis of the final product. B) Schematic of protein conjugation to HyA and subsequent binding to VEGF165. The ratio a:b represents the valency of sFlt molecules (a) covalently bound to a single chain of HyA (b). C) Schematic of low conjugation ratio (LCR) mvsFlt conjugates which are synthesized by reacting 10 molecules of sFlt with 1 HyA chain. This reaction has 59% conjugation efficiency as determined by SEC-MALS (see Table 1). D) Schematic of high conjugation ratio (HCR) mvsFlt conjugates which are synthesized by reacting 30 molecules of sFlt with 1 HyA chain (same molecular weight of HyA as in (C)). This reaction has 36% conjugation efficiency as determined by SEC-MALS (see Table 1).

2.3. SEC-MALS Characterization of mvsFIt

Protein conjugation was characterized using size exclusion chromatography with multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS) as described previously [19]. This technique allowed us to individually characterize the protein and HyA contribution to the mvsFIt conjugate. Briefly, the SEC-MALS setup consisted of an Agilent HPLC 1100 series (degasser, quaternary pump, autosampler, column holder/temperature controller, and UV-vis diode array detector) with a DAWN-HELEOS II multiangle laser light scattering detector and an Optilab T-rEX relative refractive interferometer (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA). Refractive index change was measured differentially with a 690nm laser and UV absorbance was measured with the diode array detector at 280 nm. Shodex OH pak SB-804 HQ columns were used for separation (Phenomenex Inc.). Agilent ChemStation software was used to control the HPLC system, while Wyatt Technology Astra VI software was used for data collection and analysis. A 100 uL injection of bovine serum albumin (Sigma Aldrich) at a concentration of 2 mg/mL in PBS was used for the normalization of the MALS detectors, band broadening correction, and peak alignment performed with the Astra VI algorithms. Prior to analysis, the mvsFIt conjugates were filtered through a 0.45 μm filter and 200 μL was injected at HyA concentration between 0.2-0.5 mg/mL in PBS. The flow rate was 0.3 ml/min with PBS as the mobile phase. The column temperature was maintained at 37°C . The dn/dc values were determined using batch analysis with the Rl detector to be 0.1447 and 0.185 mL g−1 for HyA-EMCH and sFIt, respectively. The UV extinction coefficient for sFIt was determined to be 0.894 L mol−1 em−1 using ExPASy (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics). The UV extinction coefficient for the HyA precursor was too low to be measured with the SEC-MALS, so the previously published value of 0.022 L mol−1 cm−1 determined for HyA in a previous publication using an offline spectrophotometer was used [19]. The radius of gyration (Rg) values reported in Table 2 for linear HyA were calculated by plotting the measured z-average radius of gyration (Rg,z) versus Mw values measured with SEC-MALS for 5 different molar masses of linear, unmodified HyA. A linear regression equation was fit to the plot in the form of R = kMb, where R was the radius of gyration and M was the molar mass. The resulting equation was used to calculate the predicted linear HyA Rg value at the Mw value for each of the conjugates. For each of the mvsFIt conjugates, a conformation plot of Rg versus molar mass was generated from the SEC-MALS data, and a linear regression fit was applied. The resulting linear regression equation for each conjugate was used to calculate the expected Rg value (shown in Table 2) at the Mw value for that specific conjugate molecule.

Table 2.

Rg, Rh, and ρ ratio for various mvsFlt.

| MVC | Linear HyA Rg (nm) | mvsFlt Rg (nm) | mvsFlt Rh (nm) | ρ =Rg/Rh |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 LCR | 89.2 | 53.9 | 72 | 0.77 |

| 300 HCR | 101.6 | 33.9 | 53 | 0.68 |

| 650 LCR | 107.4 | 61.7 | 127 | 0.62 |

| 650 HCR | 127.8 | 54.1 | 101 | 0.52 |

| 1000 LCR | 137.7 | 105.3 | 110 | 0.96 |

| 1000 HCR | 144.6 | 87.8 | 113 | 0.78 |

2.4. SDS-PAGE Analysis of mvsFIt

All mvsFIt conjugates were analyzed using SDS-PAGE in order to semi-quantitatively assess the amount of sFIt covalently bound to the HyA chain, in comparison to sFIt that was ionically associated with HyA, but unable to dialyze out of solution. Samples were prepared with 5× SDS dye loading buffer, 2-mercaptoethanol and boiled for 5 minutes at 95°C. Precast Mini-Protean TGX 4-20% gradient gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories) were run for 90 minutes at 110 volts. Gels were then stained with Bio-Safe Coomassie Stain (Bio-Rad Laboratories) for 2 hours and then imaged using a BioRad Molecular Imager ChemiDoc XRS+. The intensities of protein in the stacking and gradient gel were analyzed using ImageJ to determine the amount of protein that was conjugated versus free unconjugated protein that did not dialyze out of solution following the conjugation reaction.

2.5. Size Characterization of mvsFIt via DLS

A Brookhaven Goniometer & Laser Light Scattering system (BI-200SM, Brookhaven Instruments Corporation) was used to determine the hydrodynamic diameter of mvsFIt bioconjugates. Each sample was filtered at 0.45 μm and loaded into a 150 μL cuvette (BI-SVC, Brookhaven). Data acquisition was performed at 90 degrees with a 637nm laser for 2 minutes. Data analysis was carried out with BIC Dynamic light Scattering software (Brookhaven) using the BI-9000AT signal processor. The intensity average particle size was obtained using a non-negative least squares (NNLS) analysis method.

2.6. Binding Competition ELISA

The mvsFIt conjugates were analyzed using a VEGF165 Quantikine Sandwich ELISA (R&D Systems) to examine the effect of HyA conjugation on sFIt inhibition of VEGF165. The assay was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, VEGF165 was added to PBS with varying concentrations of sFIt or mvsFIt. Free VEGF165 that bound to the capture antibodies on the plate surface were detected using a horseradish peroxidase conjugated detection antibody and quantified using a spectrophotometer at 450 nm.

2.7. HUVEC Endothelial Cell Survival Assay

Human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from ATCC and cultured in EBM-2 media (Lonza) in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. In order to examine the effect of HyA conjugation on the ability of sFIt to bind and inhibit VEGF165 activity in vitro, a survival assay was carried out with HUVECs grown in the presence of VEGF165 and mvsFIt conjugates. HUVECs were added to 96 well plates coated with 0.2% gelatin at 10,000 cell/well in M199 media. Cells were grown in 2% FBS and 20 ng/mL VEGF165 (R&D Systems) in the presence of sFIt or mvsFIt. 72 hours after plating, the media was aspirated and the cells were washed with PBS prior to freezing for analysis with CyQuant (Life Technologies). Total cell number per well was determined by reading fluorescence at 480 nm excitation and 520 nm emission using a fluorometer (Molecular Devices).

2.8. HUVEC Tube Formation Assay

HUVEC tube formation assays were carried out in 96-well plates coated with 80 μL of Matrigel (Corning, NY) and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour to a llow gelation to occur. HUVECs were trypsinized and resuspended in M199 with 2% FBS and 20 ng/mL VEGF165 and treated with mvsFIt LCR conjugates. Wells were imaged 18 hours after plating and tube formation was quantified using ImageJ software.

2.9. HUVEC Migration Assay

Wells of a 12-well plate were coated with 0.2% gelatin. HUVECs were added at 150,000 cells/well in EBM-2 and allowed to attach and spread overnight. Using a 1 mL pipette tip, crosses were scratched into the confluent layer of HUVECs. The wells were then washed with excess PBS to remove cell debris and media and replaced with media containing VEGF165 and mvsFlt. Scratches were imaged at 0 and 24 hours post scratch and the area without cells was quantified using ImageJ and T-scratch software (CSE Laboratory software, ETH Zurich). The percent open wound area was calculated by comparing the open scratch area at 24 hours to the open scratch area at 0 hours.

2.10. Retention of mvsFlt in Crosslinked HyA Gels

To model the chemical and network structure of the vitreous, acrylated HyA (AcHyA) hydrogels were synthesized as described previously [20,21]. Briefly, adipic acid dihydrazide (ADH, Sigma Aldrich) was added in 30 molar excess to HyA in deionized water (Dl). EDC (3 mmol) and HOBt (3 mmol) were dissolved in DMSO/water and added to the HyA solution. The solution was allowed to react for 24 hours and then dialyzed exhaustively against Dl water. HyA-ADH was precipitated in 100% ethanol and reacted with acryloxysuccinimide to generate acrylate groups on the HyA. The resulting AcHyA was exhaustively dialyzed and lyophilized for storage. The presence of grafted acrylate groups on HyA chains was confirmed using H1-NMR.

To make 1% AcHyA hydrogels, 8 mg of AcHyA was dissolved in 800 μL of triethanolamine-buffer (TEOA; 0.3 M, pH 8). To each gel, 5 μg of Alexafluor 488 5-SDP ester (Life Technologies) tagged sFIt, 650 KDa LCR mvsFlt or bovine serum albumin (BSA) were added in 50 μL volumes to the AcHyA solution prior to crosslinking. Thiolated 5 kDa-PEG crosslinker (Laysan Bio, Inc.) was dissolved in 100 μL of TEOA buffer and added to dissolved AcHyA. Cell culture inserts with 4 μm sized pores (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MN) were added to wells of a 24-well plate and 70 μL of gel containing sFIt, mvsFlt or BSA was added to each insert. The gels were allowed to crosslink at 37°C for 1 hour before adding 150 μL of PBS to the wells and submerging the hydrogels. To determine release kinetics, the well supernatant was collected and fully replaced at 0, 1, 2, 3, 7, 10 and 14 days. Samples were read with a fluorometer to detect the fluorescently tagged sFIt, mvsFIt and BSA in the supernatant.

2.11. Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) Diffusivity Measurement

FRAP measurements were performed on 1% AcHyA hydrogels containing FITC labeled sFIt and 650 kDa LCR mvsFIt. Total fluorescence intensity of the hydrogels was acquired using a Zeiss LSM710 laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with a 20× magnification objective and an argon laser set at 488 nm with 50% power. Photobleaching was done by exposing a 100×100-μm spot in the field of view to high intensity laser light. The area was monitored by 15 pre-bleach scanned images at low laser intensity (2%), then bleached to 75% of the starting fluorescence intensity at 100% laser power. A total of about 300 image scans of less than 1 second were collected for each sample. The mobile fraction of fluorescent sFIt and mvsFIt molecules within the hydrogel was determined by comparing the fluorescence in the bleached region after full recovery (F∞) with the fluorescence before bleaching (Finitial) and just after bleaching (F0). The mobile fraction R was defined according to equation (1):

| (1) |

2.12. Enzymatic Degradation with MMP-7

Matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7) has been previously shown to specifically degrade sFIt [22]. To determine whether HyA conjugation shielded mvsFIt from degradation, we treated sFIt and mvsFIt with varying amounts of MMP-7 (EMD Millipore). sFIt and mvsFIt were incubated with matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7) for 12 hours at 37C while shaking at high (1:1 molar ratio MMP-7:sFlt), medium (1:2), and low (1:4) molar ratios of MMP-7 to sFIt. The enzyme-treated sFIt and mvsFIt were then loaded into precast Mini-Protean TGX 4-20% gradient gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and run at 110 volts for 90 minutes. Gels were then stained using a silver staining kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The degree of enzymatic degradation was assessed by quantifying the total amount of protein remaining in the gel following treatment with MMP-7. Each well was normalized to their respective no-MMP-7 well and background intensity was subtracted according to the blank well between the groups on the gel.

2.13. Statistical Analysis

All quantitative experiments were performed in triplicate. Values are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD). One-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc analysis was used to compare treatment groups in the quantitative measurements where appropriate and p<0.05 was used to assess statistical significance.

3. Results and Discussion

The overall goal of this study was to synthesize protein-polymer bioconjugates to increase the residence time of anti-VEGF drugs in the vitreous for use in treating patients with DR. In contrast to drugs currently used for the treatment of DR that suffer from short half-lives, we have developed large multivalent protein bioconjugates with unperturbed affinity for VEGF165, and good enzymatic stability that show delayed diffusion and mobility in an in vitro model of the vitreous.

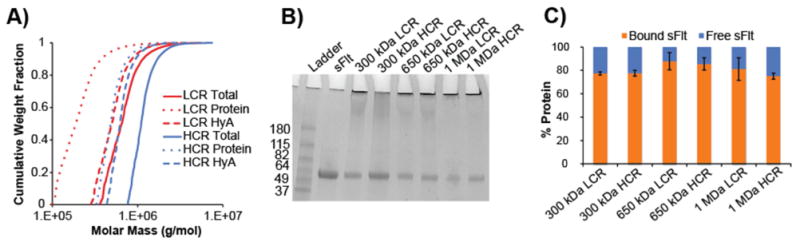

The synthesis of mvsFlt conjugates was carried out according to the schematics shown in Figure 1. We created mvsFlt at low conjugation ratios (LCR, Figure 1C) and high conjugation ratios (HCR, Figure 1D) in order to determine whether a certain valency would provide an enhanced effect on VEGF binding. This was done by initially treating sFlt with 2-iminothiolane, which on average resulted in 1.2± 0.07 thiols per protein of sFlt for conjugation to a maleimide group on the EMCH-HyA intermediate. We were able to successfully conjugate sFlt to HyA at several different molecular weights of HyA and valencies, which were significantly larger than the sFlt in its unconjugated form (Figure 2). The molecular weights of the protein and polymer components of the conjugates were characterized using SEC-MALS as shown in Table 1 and Figure 2A. Conjugates with 10:1 feed ratios (LCR) of sFlt to HyA averaged 58.5±10.9% conjugation efficiency whereas conjugates with 30:1 sFlt to HyA feed ratios (HCR) had conjugation efficiencies averaging 36.2±2.2%. SDS-PAGE of unbound sFlt exhibited a protein band at the predicted 50 kDa. Conversely, mvsFlt bioconjugates only migrated into the stacking portion of the gel, indicating inhibited mobility as a result of covalent attachment to the much larger multivalent conjugate (Figure 2B). Gel analysis using ImageJ indicated that on average 76.4±6.7% of sFlt in the mvsFlt bioconjugates was covalently bound whereas the rest of the detected sFlt was non-specifically interacting with the hyaluronic acid chain in solution and thus could not be removed by dialysis (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Characterizing mvsFlt conjugation efficiency and size.

A) SEC-MALS chromatogram depicting cumulative weight fraction versus molar mass of 650 kDa LCR and HCR bioconjugates. Dotted line, dashed line, and solid line represent total molar mass of all covalently attached sFlt proteins, HyA molar mass and total bioconjugate molar mass (all given as g/mol), respectively. B) 4-20% SDS-page gradient gel of sFlt and mvsFlt. Protein bands in the stacking gel indicate successful protein conjugation to HyA. Protein bands within gel represent the proportion of protein that was not covalently bound, but remained in solution after dialysis. C) Quantified protein band intensities of SDS-PAGE gel. Percent bound sFlt was determined by dividing the intensity of protein in the stacking gel by total protein intensity within the respective well. Free sFlt was determined by dividing the intensity of protein within the separating gel by the total protein intensity within the respective well.

Table 1.

Characterization of mvsFlt conjugates by SEC-MALS.

| 300 kDa LCR | 300 kDa HCR | 650 kDa LCR | 650 kDa HCR | 1 MDa LCR | 1 MDa HCR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HyA Mn | 3.1E5 | 2.1E5 | 5.4E5 | 6.5E5 | 9.7E5 | 1.0E6 |

| HyA Mw | 3.8E5 | 3.4E5 | 6.3E5 | 7.3E5 | 1.2E6 | 1.1E6 |

| HyA ĐM | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Total Protein per HyA Chain Mn | 2.6E5 | 5.2E5 | 2.4E5 | 5.4E5 | 2.3E5 | 5.3E5 |

| Total Protein per HyA Chain Mw | 3.4E5 | 5.6E5 | 3.6E5 | 6.0E5 | 3.1E5 | 5.4E5 |

| Total Protein ĐM | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| sFlt:HyA (Mn)a | 5.3 | 10.0 | 4.9 | 10.7 | 4.6 | 10.5 |

| sFlt:HyA (Mw)b | 6.8 | 11.2 | 7.3 | 11.9 | 6.2 | 10.8 |

LCR is low conjugation ratio conjugate (10:1 sFlt per HyA chain feed ratio)

HCR is high conjugation ratio conjugate (30:1 sFlt per HyA chain feed ratio)

Mn = Number average molecular weight given in g/mol.

Mw = Weight average molecular weight given in g/mol

ĐM = Dispersity of the polymer calculated by Mw/Mn

Final stoichiometric ratio of sFlt to HyA was calculated by dividing total attached protein Mn (a) or Mw (b) calculated using sFlt molecular weight (50 kDa) as determined from SDS PAGE.

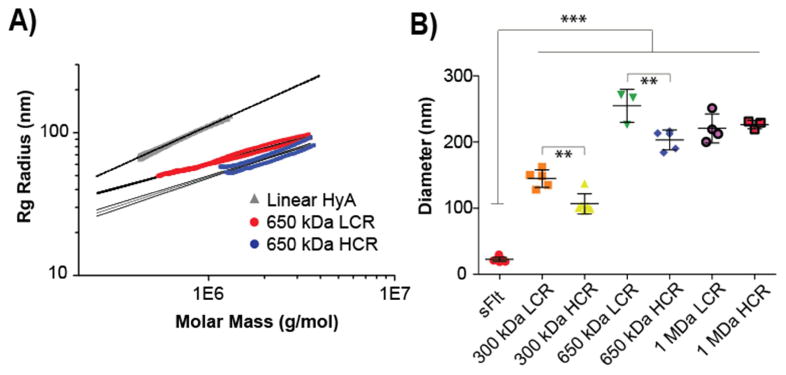

Since drug size is a critical factor that determines its mobility through biological hydrogels such as the vitreous, all mvsFlt conjugates were also characterized by SEC-MALS to determine conjugate z-average radius (Rg) in solution. Conformation plots for unreacted linear HyA, and 650kDa LCR and HCR are shown in Figure 3A to illustrate the dependence of Rg on molar mass. The slope of the conformation plot is indicative of the structure of a polymer in solution, where a swollen linear polymer chain in a good solvent should be ∼ 0.588 [23,24]. We report a slope of 0.59 for unreacted HyA over a wide molar mass range, in good agreement with numerous previously published reports [25–28], and indicative that the HyA chains were linear. The slopes for the LCR and HCR decreased compared to the linear HyA as a result of compaction of the molecules and were 0.35 and 0.42, respectively. This observation is well known for branching of a macromolecule in solution [24]. As such, we make the analogy between grafting sFlt to HyA and a hyperbranched macromolecule, and as the branching ratio increases Rg decreases. Values of Rg calculated at the measured Mw for the 300 kDa, 650 kDa, and 1 MDa samples (defined in Table 1) are given in Table 2. The reduction in Rg was evident between LCR and HCR mvsFlt conjugates for a specific molecular weight HyA, but increased in relative size as the HyA Mw increased. The Rh data from DLS measurements confirmed this trend (Table 2). The ρ ratio (ρ = Rg/Rh) calculated from the SECMALS and DLS data is indicative of molecular structure, with a ratio of ∼ 0.7 approaching a compact sphere. MVCs were in the range of 0.52 to 0.77 for the 300 kDa and 650kDa mvsFlt conjugates, suggesting a condensed sphere structure. The ρ ratio for 1 MDa mvsFlt approached unity, representing a less compact structure.

Figure 3. Size comparison of mvsFlt conjugates using SEC-MALS and DLS.

A) Conformation plot showing the linear regression lines and 95% confidence intervals for linear hyaluronic acid compared to two representative mvsFlt conjugates at 650 kDa. The slopes of the regression lines are decreased compared to the linear HyA, demonstrating the grafted (i.e., branched) nature of the mvsFlt conjugates. B) Dynamic light scattering analysis of conjugates. sFlt was significantly smaller than all mvsFlt bioconjugates (***p<0.001). In the case of 300 and 650 kDa mvsFlt bioconjugates, the LCR mvsFlt was significantly larger than its respective HCR conjugate (**p<0.01), consistent with increased grafting. Values are given as mean ±SD.

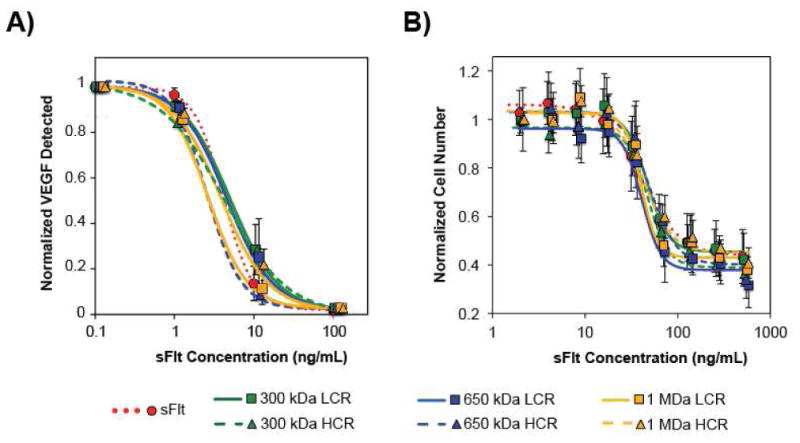

We employed a VEGF165 ELISA and HUVEC survival assay to determine whether conjugation of sFlt to HyA affected either sFlt's affinity for VEGF165 or altered VEGF165-dependent cell survival. These experiments were carried out due to their dependence on VEGF, allowing us to make a direct comparison of the various multivalent conjugates on inhibition of VEGF activity. Using a VEGF165 specific ELISA we found a dose-dependent response that indicated conjugation of sFlt to HyA did not alter the ability of mvsFlt to bind VEGF165 (Figure 4A). ELISA results indicated that the IC50 value of sFlt was 3.8±2.4 ng/mL and the IC50 value of the various mvsFlt conjugates averaged to 3.4±1.1 ng/mL (Table 3).

Figure 4. All mvsFlt bioconjugates maintain their ability to inhibit VEGF165 dependent activities in VEGF165 ELISA and VEGF165-dependent HUVEC survival assays.

A) Dose-dependent inhibition of VEGF165 binding to a capture antibody by mvsFlt bioconjugates. Inhibition was independent of whether the sFlt was bound to HyA or free in solution. There were no significant differences between any of the groups (Table 3). B) Dose-dependent inhibition of HUVEC survival with mvsFlt at different molecular weights and protein valencies in the presence of VEGF165. Inhibition was independent of whether the sFlt was bound to HyA or free in solution (Table 3). Values are given as means ±SD.

Table 3.

IC50 values from ELISA and HUVEC survival assays examining mvsFlt inhibition of VEGF165

| ELISA (ng/mL) | HUVEC Survival (ng/mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| sFlt unconjugated | 3.8 ± 2.4 | 39.3 ± 4.4 |

| 300 kDa LCR | 4.5 ± 1.5 | 46.9 ± 9.9 |

| 300 kDa HCR | 4.7 ± 1.7 | 44.4 ± 2.6 |

| 650 kDa LCR | 3.9 ± 2.6 | 41.7 ± 6.7 |

| 650 kDa HCR | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 43.2 ± 13.6 |

| 1 MDa LCR | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 44.9 ± 10.7 |

| 1 MDa HCR | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 45.4 ± 2.2 |

HUVECs require VEGF for carrying out angiogenic processes including cell survival, tube formation, and migration. Therefore, all of the HUVEC assays were conducted in media with low serum (2% FBS) and 20 ng/mL VEGF. This low serum-media was optimized to single out the effect of VEGF, which we then challenged with the addition of sFlt and the mvsFIt conjugates. In survival assays with HUVECs, mvsFIt demonstrated a dose-dependent decrease in survival, and the effect was independent of conjugation to HyA similar to the ELISA results (Figure 4B, Table 3). These results indicate that covalent conjugation of sFIt to HyA does not reduce the ability of sFIt to bind VEGF. This is extremely promising due to the fact that other conjugation technologies such as PEGylation, reported that conjugation significantly reduces the bioactivity of the protein [29,30].

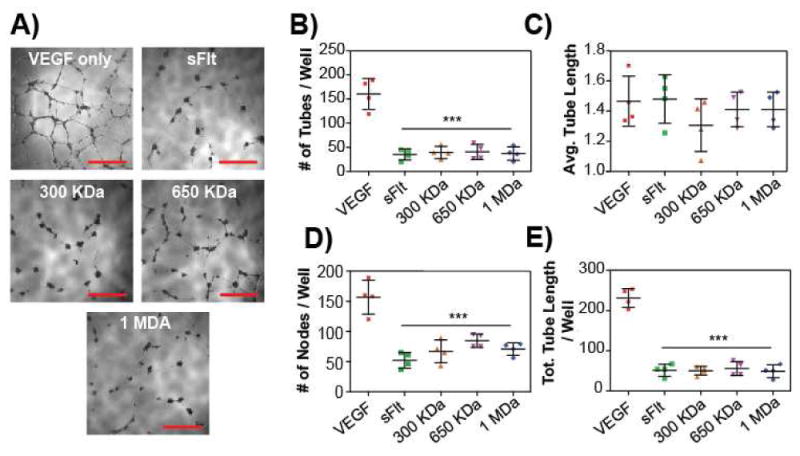

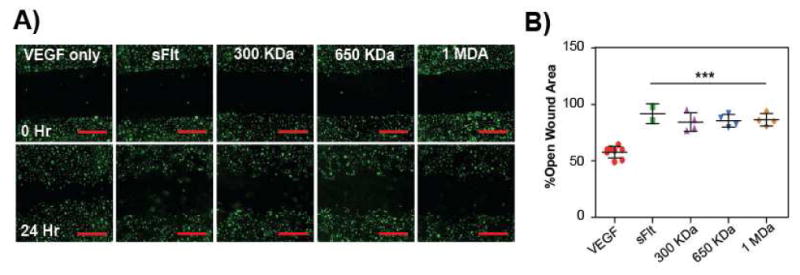

For subsequent studies, only LCR conjugates of different molecular weights were used, since all conjugates performed equally well to inhibit VEGF165 activity in the ELISA and survival assays. In vitro tube formation and migration assays enabled us to examine the effect of mvsFlt conjugates in vitro on two additional processes involved in angiogenesis in vivo, organization into tubes and cell migration. Similar to the survival data, sFlt and mvsFlt had similar inhibition profiles of VEGF165 in these two assays where addition of sFlt and mvsFlt equally inhibited organization into tubes (Figure 5) and closure of wounds (Figure 6). Taken together, the ELISA and in vitro angiogenesis assays indicated that conjugation of sFlt to HyA did not affect the ability of sFlt to bind VEGF165 and that all mvsFlt conjugates maintained their ability to inhibit endothelial cell functions mediated by VEGF165 signaling.

Figure 5. mvsFIt inhibits HUVEC tube formation.

A) Representative images of inhibited HUVEC tube formation on Matrigel (BD Biosciences) when treated with 1 μg/mL of all LCR mvsFIt bioconjugates. Cells were seeded at 20,000 cells per well of a 96-well plate on 100 μL of matrigel and imaged at 18 hours. Scale bar = 500 urn. B-E) Quantification of total number of tubes per well (B), average tube length (C), total number of nodes (branching points, D), and total tube length per well (E) (***p<0.001).

Figure 6. mvsFIt inhibits VEGF165-driven HUVEC migration.

Representative images of inhibition of HUVEC migration with LCR mvsFIt bioconjugates of varying molecular weights. HUVECs were allowed to grow to confluence in 12-well plates prior to making a scratch and were treated with 20 ng/mL VEGF165 in the presence of 200 ng/mL mvsFIt. Cells were stained with CellTracker Green (Life Technologies) prior to seeding. Scale bar = 20 μm. B) Quantified HUVEC migration following treatment with LCR mvsFlt showing percent open wound area calculated by comparing open wound area at 24 hours to open wound area at time 0 (***p<0.001).

We exploited crosslinked HyA gels [20,21] to examine how conjugation of sFlt to HyA affects diffusion. A synthetic hydrogel was chosen as a model system for studying the vitreous in vitro based primarily on compositional similarity to the vitreous with respect to high HyA content. This model has added advantages compared to ex vivo vitreous samples from porcine or bovine sources, as the synthetic hydrogels are well-characterized system with high batch-to-batch consistency in composition. We used several different models as described in the supplemental methods to characterize the mesh size of HyA hydrogels (Table 4). Preliminary experiments analyzing size dependent diffusion using 40 kDa and 2 MDa fluorescently tagged dextrans (Life Technologies) were used to confirm that this hydrogel system would be appropriate for examining molecular weight and size dependent diffusion (Figure S1B).

Table 4.

M̄c and mesh size calculations based on swelling and rheoloqical data.

| Model | M̄c (g/mol)* | ξ (nm)* |

|---|---|---|

| Peppas/Merrill [31] - Affine (Q)a | 299,030 | 377 |

| Erman [32] – Phantom (Q)a | 388,940 | 430 |

| Mooney [33] – Affine (G′)b | 247,750 | 343 |

| Erman [32] – Phantom (G′)b | 123,880 | 242 |

M̄c - molecular weight between crosslinks

ξ - mesh size of 1% HyA gel calculated according to [34]

M̄c calculated from mass swelling data

M̄c calculated from rheology data

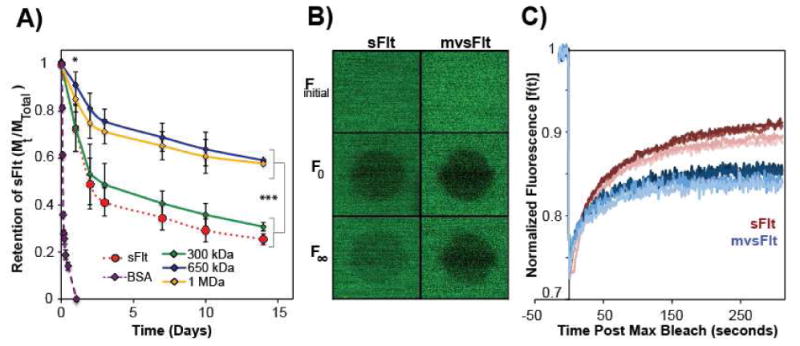

Using this system, we analyzed the release kinetics of sFIt and all LCR mvsFIt bioconjugates from the HyA gels. We expected that the main effect of mvsFIt bioconjugates would be size-dependent decreases in mobility, and thus we chose to analyze only conjugates of varying sizes while holding valency constant. After 14 days, only 30.8±1.9% of sFIt remained in the gel in comparison to 38.3%±2.2%, 63.8±0.5% and 62.8% ±0.4% of 300 kDa, 650 kDa, and 1 MDa LCR mvsFIt conjugates, respectively (Figure 7A). In comparison, 100% of BSA released after 24 hours, significantly shorter than sFIt. This difference with sFIt was attributed to different isoelectric points (5.4 for BSA [35] and 9.5 for sFIt [36]) and BSA's low affinity for HyA, but not protein size since BSA and sFIt have hydrodynamic diameters of 7 nm [37] and 22 nm, respectively.

Figure 7. sFIt conjugation to HyA decreases mvsFIt mobility and diffusion in HyA gels.

A) Alexafluor 488-tagged LCR mvsFIt bioconjugates 650 kDa and 1 MDa encapsulated in 1% HyA hydrogels diffused out significantly slower than unconjugated sFIt and 300 kDa mvsFIt after day 1 (*p<0.05) and persisted until the last time point, day 14 (***p<0.001). B) Representative confocal images corresponding to FRAP experiment of FITC tagged 650 kDa LCR mvsFIt. Finitial depicts mvsFIt in the gel prior to bleaching.; F0 is the fluorescence measurement immediately after 75% photobleaching; F∞ corresponds to the maximal recovery of fluorescence at the end of the experiment. C) Normalized fluorescence recovery [f(t)] of FITC labeled sFIt and 650 kDa LCR mvsFIt after photobleaching.

To assess whether diffusion through the gel was Fickian, we fit the curves in Figure 7A using equation (2) as described by Ritger et al. [38]:

| (2) |

The diffusional exponent, n, is indicative of whether diffusion is Fickian and if n is equal to 0.5, the transport is Fickian. The n value for BSA, sFIt and mvsFIt release was determined to be 0.3-0.4 (Fig. S2), indicating that the diffusion through the gel was not Fickian. BSA was depleted from the gel through rapid burst release due to the extremely small size of the protein and very low affinity to the HyA hydrogel due to charge repulsion, leading to non-Fickian diffusion. The sFIt and mvsFIt conjugates release slower in comparison due in part to ionic affinity with the HyA hydrogel and size. Although the sFIt and BSA are similar in size (50 kDa and 66 kDa, respectively), the sFIt has a much stronger ionic interaction with the matrix, which slows its diffusion from the gel, also resulting in non-Fickian diffusion due to this strong affinity. The 300 kDa mvsFIt conjugate is small enough in size (Dh < 150 nm, see Fig. 3B) relative to the estimated hydrogel ξ (Table 4) to release as rapidly as sFIt. The two largest conjugates were close to the mesh size in diameter (Dh > 200 nm) and were significantly impeded in their release due to size and affinity, resulting in gel release that followed the reptation mechanism of diffusion [39].

Based on data from the sFIt release studies, we chose to study only the 650 kDa LCR bioconjugate using FRAP, since this conjugate displayed the highest difference in gel retention in comparison to unconjugated sFlt. The mobile fraction of sFlt in the gel was 73.8±4.4% whereas the mobile fraction of the mvsFlt within the gel was 48.3±3.0%, indicating that a significant portion of the mvsFlt bioconjugate was large enough to become immobile within the gel due to the similarity in diameter between the mvsFlt and the mesh size of the HyA gel. Experimental data in Figure 7C was fit according to Soumpasis [40] to obtain characteristic diffusion times. Interestingly, the characteristic diffusion time for mvsFlt (94.8±19.5 s) was significantly faster than sFlt (176±18.1 s). We believe that this difference is due to ionic shielding of the positively charged sFlt by the negatively charged hyaluronic acid within the multivalent conjugate, which reduces the overall affinity of the conjugate for the gel allowing for faster diffusion. In contrast, the unconjugated sFlt remains highly positively charged resulting in stronger ionic affinity within the HyA gel that slow its characteristic diffusion time. However, the mvsFlt in the hydrogel also recovered fluorescence to a significantly lower degree, 85.3±0.8%, compared to sFlt, which recovered to 91.6%±2.4%. Although the mvsFlt conjugate displayed faster diffusion, a much smaller percentage of the mvsFlt bioconjugate is actually mobile and the size significantly limited the total fluorescence recovery, results that are also supported by the gel release data in Figure 7A. It becomes clear that even though mvsFlt can diffuse faster as shown by FRAP in Figures 7B,C a much smaller portion of this sample is able to move due to size and thus much less of it is released over time as evidenced by the gel release data in Figure 7A. Taken together, we anticipate that the effect of size will be the strongest determinant of mvsFlt residence time in vivo.

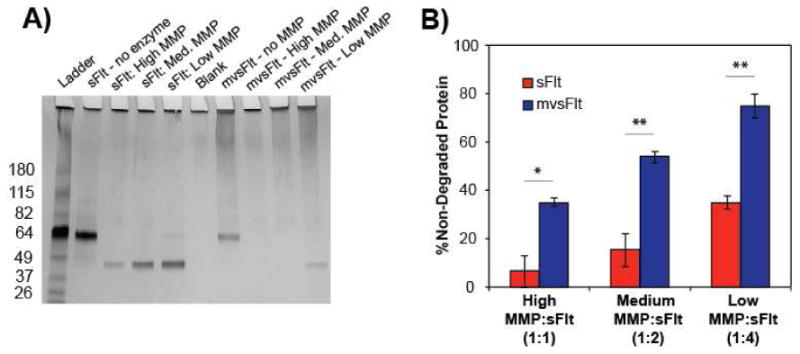

We examined how conjugation of sFlt to HyA affected protease degradation of the protein using MMP-7, a protease that has been shown to specifically degrade sFlt [22]. We found that conjugation of sFlt to HyA shielded the degradation of sFlt at all molar ratios of MMP-7 to sFlt (Figure 8A). At high concentrations of protease (1:1 molar ratio of MMP-7 to sFlt), only 6.8±6.6% of sFlt remained detectable in comparison to 34.8±1.8% of mvsFlt (Figure 8B). Decreasing the ratio of MMP-7 to sFlt from 1:1 to 1:4 still resulted in significant degradation of sFlt and degradation shielding of the conjugated form, where detectable sFlt increased to 34±2.7% in comparison to detectable mvsFlt at 74.8±4.9% (Figure 8B). We believe that the shielding effect of HyA will be crucial for maintaining mvsFlt stability and bioavailability in vivo, aiding in the prolonged anti-angiogenic effect of mvsFlt bioconjugates.

Figure 8. Conjugation to HyA reduces susceptibility to protease degradation by MMP-7.

A) 4-20% SDS-page gradient gel of sFlt and mvsFlt (650 kDa LCR) following 12 hour treatment with MMP-7 at high, medium and low molar ratios of MMP-7 to sFlt, which correspond to 1:1, 1:2 and 1:4 molar ratios of MMP-7 to sFlt. Band intensity was normalized to the no MMP-7 treatment within each group and background was subtracted from each sample using the blank well. B) Quantification of 4-20% gradient gel of sFlt and mvsFlt treated with MMP-7 at high, medium, and low molar ratios of sFlt to MMP-7 for 12 hours (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

Intravitreally injected drugs are cleared from the eye via two main mechanisms: 1) the anterior elimination pathway powered by counter directional bulk aqueous flow; and, 2) the posterior elimination pathway via bulk flow due to osmotic pressure gradients of the posterior segment [41,42]. The posterior pathway is much faster than the anterior route and is reserved for small lipophilic drugs that are able to rapidly traverse the retinal pigment epithelium using transcellular routes. In contrast, larger drugs are only able to escape through the anterior pathway, a process that is highly dependent on drug size and molecular weight [43]. For these reasons, we predict that the mvsFlt bioconjugates would be cleared through the anterior route; however, we anticipate that the 650 kDa and 1 MDa bioconjugates would take significantly longer to clear in comparison to the 300 kDa and unconjugated sFlt based on gel release data (Fig. 7A). Due to the similarity in molecular weight and composition, we anticipate that the mvsFlt will follow similar routes of degradation and turnover to the native HyA in the vitreous via anterior clearance mechanisms. We also did not observe aggregation in our mvsFlt conjugates, thus we do not anticipate that the mvsFlt will impede flow through the trabecular meshwork in any way.

Better systems for improved drug delivery to the posterior segment of the eye have been in high demand with the increasing prevalence of retinal diseases including diabetic retinopathy [41,44–46]. Intravitreal injection (IVT) has become the current gold standard for delivering drugs to the retina in order to circumvent blood retinal barriers, which keep most drugs out of the eye when delivered topically, systemically and transsclerally [47]. However, repeated intravitreal injections are required to reach and maintain effective drug doses, which can damage the lens, cause retinal detachment, hemorrhage and result in poor patient compliance [48]. For these reasons, improvements to IVT technologies are needed for treating posterior segment diseases. The use of drug-containing liposomes has emerged as a popular drug delivery system; however, liposomes suffer from several drawbacks including low solubility, high production cost, and leakage/fusion of encapsulated drugs and molecules [46,49,50]. Ocular implants represent another branch of drug delivery systems used for treating ocular diseases for providing drug release for several months to years, but can affect the patients' line of sight and non-biodegradable implants often require surgical implantation and sometimes invasive device removal [44,45,51]. PEGylation of drugs also presents an interesting approach to increasing drug stability and residence time; however, clinical trials with PEGylated drugs like Pegaptanib (Macugen) have shown that this approach does not significantly increase drug half-life in the vitreous [29,52,53]. Furthermore PEGylated drugs typically have lower effectiveness/affinity as a result of the PEG grafting [29,30].

In contrast to these approaches, we used hyaluronic acid, a naturally occurring biopolymer found in very high concentrations within the vitreous [14,54]. Although hyaluronic acid has previously been shown to induce angiogenesis in certain systems [55], we do not anticipate that the HyA in our mvsFIt will induce the growth of new blood vessels due to the fact that HyA is naturally found in high concentrations ranging between 100 and 400 μg/g in the vitreous [56] and is naturally turned over without the induction of angiogenesis in the retina. Furthermore, previous research has shown that vitreal hyaluronic acid has anti-angiogenic properties [57], an effect that the HyA in our conjugates may supplement.

In this work we have introduced a new technology using multivalent forms of an anti-VEGF protein, sFIt, that improves its activity with respect to diffusion time and mobility through hydrogels as well as shields the protein from protease degradation, promising results that may indicate potential for improvement upon clinically used anti-VEGF drugs. Specifically, conjugation to HyA decreased the release kinetics of mvsFIt from crosslinked HyA hydrogels, a system meant to model drug release from the vitreous of the eye. Although attachment of several sFIt molecules per HyA chain did not improve affinity for VEGF165, we showed that conjugates maintained their ability to bind VEGF165 following chemical conjugation. These findings illustrate the effectiveness of mvsFIt at inhibiting VEGF165 activity, improving sFIt protein stability, and decreasing conjugate mobility in hydrogels, all characteristics that we anticipate will be essential in improving anti-VEGF drug treatments for patients with diabetic retinopathy. Furthermore, our approach provides tunability and modularity by allowing us to control bioconjugate size through altering HyA molecular weight and protein attachment independently, a technology that is not limited in its use for diabetic retinopathy but can be applied in the development of drugs for other diseases as well.

4. Conclusion

Developing drugs with suitable half-lives is a universal challenge and multivalent conjugates have immense promise for maintaining drug stability as well as prolonging residence time in a range of tissues. The multivalent conjugate technology presented here is facile and utilizes hyaluronic acid, a biopolymer ubiquitous in the human body including the vitreous and allows for tunability in the number of grafted proteins and overall conjugate size. The technology is also easily adaptable for other therapeutic applications in the eye and other tissues. Therefore, we anticipate that multivalent protein bioconjugates will be not only be useful for improving drug delivery to patients with diabetic retinopathy, but also for clinical outcomes and patient quality of life for a wide range of diseases,.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health R01HL096525 (K.E.H.), and the Jan Fandrianto Chair Fund (K.E.H.). We would like to thank Jonathan Winger and Xiao Zhu for guidance with the insect cell protein expression system and providing reagents. We would like to acknowledge Ann Fischer for help express the sFlt protein in the Tissue Culture Facility at UC Berkeley and Dawn Spelke and Anusuya Ramasubramanian for help optimizing protein purification from insect cells.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fong R, Aiello DS, Gardner L, King TW, Blankenship GL, Cavallerano G, Ferris JD, Klein FL. Retinopathy in Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:S84–87. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulton M, Foreman D, Williams G, McLeod D. VEGF localisation in diabetic retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:561–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.5.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller JW, Le Couter J, Strauss EC, Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor a in intraocular vascular disease. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witmer A. Vascular endothelial growth factors and angiogenesis in eye disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:1–29. doi: 10.1016/S1350-9462(02)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonetti DA, Klein R, Gardner TW. Diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1227–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1005073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowler JGF. Laser management of diabetic retinopathy. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:277–279. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.6.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solaiman KaM, Diab MM, Dabour Sa. Repeated intravitreal bevacizumab injection with and without macular grid photocoagulation for treatment of diffuse diabetic macular edema. Retina. 2013;33:1623–9. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318285c99d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lip PL, Belgore F, Blann AD, Hope-Ross MW, Gibson JM, Lip GYH. Plasma VEGF and soluble VEGF receptor FLT-1 in proliferative retinopathy: Relationship to endothelial dysfunction and laser treatment. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2115–2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen QD, Brown DM, Marcus DM, Boyer DS, Patel S, Feiner L, et al. Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: Results from 2 phase iii randomized trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Network DRCR. A Phase II Randomized Clinical Trial of Intravitreal Bevacizumab for Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1860–1867. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Do DV, Nguyen QD, Boyer D, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Brown DM, Vitti R, et al. One-year outcomes of the da VINCI study of VEGF trap-eye in eyes with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1658–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagliarini S, Beatty S, Lipkova B, Perez-Salvador Garcia E, Reynders S, Gekkieva M, et al. A 2-year, phase IV, multicentre, observational study of ranibizumab 0.5 mg in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration in routine clinical practice: The EPICOHORT study. J Ophthalmol. 2014;2014:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2014/857148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen SY, Mimoun G, Oubraham H, Zourdani A, Malbrel C, Queré S, et al. Changes in visual acuity in patients with wet age-related macular degeneration treated with intravitreal ranibizumab in daily clinical practice: the LUMIERE study. Retina. 2013;33:474–481. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31827b6324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott JE. The chemical morphology of the vitreous. Eye (Lond) 1992;6(Pt 6):553–5. doi: 10.1038/eye.1992.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barleon B, Totzke F, Herzog C, Blanke S, Kremmer E, Siemeister G, et al. Mapping of the sites for ligand binding and receptor dimerization at the extracellular domain of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor FLT-1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10382–10388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wall ST, Saha K, Ashton RS, Kam KR, Schaffer DV, Healy KE. Multivalency of Sonic hedgehog conjugated to linear polymer chains modulates protein potency. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:806–12. doi: 10.1021/bc700265k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conway A, Vazin T, Spelke DP, Rode NA, Healy KE, Kane RS, et al. Multivalent ligands control stem cell behaviour in vitro and in vivo. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:831–838. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han BW, Layman H, Rode NA, Conway A, Schaffer DV, Boudreau N, et al. Multivalent conjugates of sonic hedgehog accelerate diabetic wound healing. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21:2366–2378. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2014.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollock JF, Ashton RS, Rode Na, Schaffer DV, Healy KE. Molecular characterization of multivalent bioconjugates by size-exclusion chromatography with multiangle laser light scattering. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23:1794–801. doi: 10.1021/bc3000595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jha AK, Mathur A, Svedlund FL, Ye J, Yeghiazarians Y, Healy KE. Molecular Weight and Concentration of Heparin in Hyaluronic Acid-based Matrices Modulates Growth Factor Retention Kinetics and Stem Cell Fate. J Control Release. 2015;209:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jha A, Tharp K, Ye J, Santiago-Ortiz J, Jackson W, Stahl A, et al. Growth factor sequestering and presenting hydrogels promote survival and engraftment of transplanted stem cells. Biomaterials. 2015;47:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito TK, Ishii G, Saito S, Yano K, Hoshino A, Suzuki T, et al. Degradation of soluble VEGF receptor-1 by MMP-7 allows VEGF access to endothelial cells. Blood. 2009;113:2363–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-172742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubinstein M, Colby RH. Polymer Physics. Oxford Univ Press; New York: 2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Podzimek S, Hermannova M, Bilerova H, Bezakova Z, Velebny V. Solution properties of hyaluronic acid and comparison of SEC-MALS-VIS data with off-line capillary viscometry. J Appl Polym Sci. 2010;116:3013–3020. doi: 10.1002/app.31834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harmon PS, Maziarz EP, Liu XM. Detailed characterization of hyaluronan using aqueous size exclusion chromatography with triple detection and multiangle light scattering detection. J Biomed Mater Res - Part B Appl Biomater. 2012;100 B:1955–1960. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi R, Kubota K, Kawada M, Okamoto A. Effect of Molecular Weight Distribution on the Solution Properties of Sodium Hyaluronate in 0.2M NaCl Solution. Biopolymers. 1999;50:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fouissac E, Milas M, Rinaudo M, Borsali R. Influence of the ionic strength on the dimensions of sodium hyaluronate. Macromolecules. 1992;25:5613–5617. doi: 10.1021/ma00047a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendichi R, Šoltés L, Giacometti Schieroni A. Evaluation of radius of gyration and intrinsic viscosity molar mass dependence and stiffness of hyaluronan. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:1805–1810. doi: 10.1021/bm0342178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veronese FM. Peptide and protein PEGylation. Biomaterials. 2001;22:405–417. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fishburn SC. The pharmacology of PEGylation: Balancing PD with PK to generate novel therapeutics. J Pharm Sci. 2010;97:4167–4183. doi: 10.1002/jps. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peppas Na, Merrill EW. Crosslinked poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels as swollen elastic networks. J Appl Polym Sci. 1977;21:1763–1770. doi: 10.1002/app.1977.070210704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mark JE, Erman B. Rubberlike Elasticity: A Molecular Primer. 1st. John Wiley & Sons; Toronto: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee KY, Rowley Ja, Eiselt P, Moy EM, Bouhadir KH, Mooney DJ. Controlling mechanical and swelling properties of alginate hydrogels independently by cross-linker type and cross-linking density. Macromolecules. 2000;33:4291–4294. doi: 10.1021/ma9921347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baier Leach J, Bivens Ka, Patrick CW, Jr, Schmidt CE. Photocrosslinked hyaluronic acid hydrogels: Natural, biodegradable tissue engineering scaffolds. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;82:578–589. doi: 10.1002/bit.10605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu J, Su T, Thomas R. Structural Conformation of Bovine Serum Albumin Layers at the Air-Water Interface Studied by Neutron Reflection. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1999;213:426–437. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1999.6157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thadhani R, Kisner T, Hagmann H, Bossung V, Noack S, Schaarschmidt W, et al. Pilot Study of Extracorporeal Removal of Soluble Fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase 1 in Preeclampsia. Circulation. 2011;124:940–950. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.034793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yohannes G, Wiedmer SK, Elomaa M, Jussila M, Aseyev V, Riekkola ML. Thermal aggregation of bovine serum albumin studied by asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation. Anal Chim Acta. 2010;675:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ritger PL, Peppas Na. A simple equation for description of solute release I. Fickian and non-Fickian release from non-swellable devices in the form of slabs, spheres, cylinders or discs. J Control Release. 1987;5:23–36. doi: 10.1016/0168-3659(87)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Gennes PG. Conjectures on the transport of a melt through a gel. Macromolecules. 1986;19:1245–1249. doi: 10.1021/ma00158a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soumpasis DM. Theoretical analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery experiments. Biophys J. 1983;41:95–97. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84410-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gaudana R, Ananthula HK, Parenky A, Mitra AK. Ocular drug delivery. AAPS J. 2010;12:348–60. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9183-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee SS, Robinson MR. Novel drug delivery systems for retinal diseases. A review. Ophthalmic Res. 2009;41:124–35. doi: 10.1159/000209665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edelhauser HF, Rowe-Rendleman CL, Robinson MR, Dawson DG, Chader GJ, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Ophthalmic drug delivery systems for the treatment of retinal diseases: basic research to clinical applications. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:5403–5420. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Del Amo EM, Urtti A. Current and future ophthalmic drug delivery systems. A shift to the posterior segment. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:135–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thrimawithana TR, Young S, Bunt CR, Green C, Alany RG. Drug delivery to the posterior segment of the eye. Drug Discov Today. 2011;16:270–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sahoo SK, Dilnawaz F, Krishnakumar S. Nanotechnology in ocular drug delivery. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maurice D. Review: practical issues in intravitreal drug delivery. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2001;17:393–401. doi: 10.1089/108076801753162807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jager RD, Aiello LP, Patel SC, Cunningham ET. Risks of intravitreous injection: a comprehensive review. Retina. 2004;24:676–698. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oh EJ, Choi JS, Kim H, Joo CK, Hahn SK. Anti-Flt1 peptide - Hyaluronate conjugate for the treatment of retinal neovascularization and diabetic retinopathy. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3115–3123. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bochot A, Fattal E. Liposomes for intravitreal drug delivery: a state of the art. J Control Release. 2012;161:628–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yasukawa T, Ogura Y, Tabata Y, Kimura H, Wiedemann P, Honda Y. Drug delivery systems for vitreoretinal diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2004;23:253–81. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veronese FM, Pasut G. PEGylation, successful approach to drug delivery. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ng EWM, Shima DT, Calias P, Cunningham ET, Guyer DR, Adamis AP. Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:123–32. doi: 10.1038/nrd1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bishop P. The biochemical structure of mammalian vitreous. Eye. 1996;10:664–670. doi: 10.1038/eye.1996.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park D, Kim Y, Kim H, Kim K, Lee YS, Choe J, et al. Hyaluronic acid promotes angiogenesis by inducing RHAMM-TGFβ receptor interaction via CD44-PKCδ. Mol Cells. 2012;33:563–574. doi: 10.1007/s10059-012-2294-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laurent U, Törnquist P, Granath K, Lilja-Englind K, Ytterberg D. Molecular weight and concentration of hyaluronan in vitreous humour from diabetic patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 1990;68:109–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1990.tb01972.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lutty GA, Thompson DC, Gallup JY, Mello RJ, Patz A, Fenselau A. Vitreous: An Inhibitor of Retinal Extract-Induced Neovascularization. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1983;24:52–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.