Abstract

Background

Among natural populations, there are different colours of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). The colour of barley grains is directly related to the accumulation of different pigments in the aleurone layer, pericarp and lemma. Blue grain colour is due to the accumulation of anthocyanins in the aleurone layer, which is dependent on the presence of five Blx genes that are not sequenced yet (Blx1, Blx3 and Blx4 genes clustering on chromosome 4HL and Blx2 and Blx5 on 7HL). Due to the health benefits of anthocyanins, blue-grained barley can be considered as a source of dietary food. The goal of the current study was to identify and characterize components of the anthocyanin synthesis regulatory network for the aleurone layer in barley.

Results

The candidate genes for components of the regulatory complex MBW (consisting of transcription factors MYB, bHLH/MYC and WD40) for anthocyanin synthesis in barley aleurone were identified. These genes were designated HvMyc2 (4HL), HvMpc2 (4HL), and HvWD40 (6HL). HvMyc2 was expressed in aleurone cells only. A loss-of-function (frame shift) mutation in HvMyc2 of non-coloured compared to blue-grained barley was revealed. Unlike aleurone-specific HvMyc2, the HvMpc2 gene was expressed in different tissues; however, its activity was not detected in non-coloured aleurone in contrast to a coloured aleurone, and allele-specific mutations in its promoter region were found. The single-copy gene HvWD40, which encodes the required component of the regulatory MBW complex, was expressed constantly in coloured and non-coloured tissues and had no allelic differences. HvMyc2 and HvMpc2 were genetically mapped using allele-specific developed CAPS markers developed. HvMyc2 was mapped in position between SSR loci XGBS0875-4H (3.4 cM distal) and XGBM1048-4H (3.4 cM proximal) matching the region chromosome 4HL where the Blx-cluster was found. In this position, one of the anthocyanin biosynthesis structural genes (HvF3’5’H) was also mapped using an allele-specific CAPS-marker developed in the current study.

Conclusions

The genes involved in anthocyanin synthesis in the barley aleurone layer were identified and characterized, including components of the regulatory complex MBW, from which the MYC-encoding gene (HvMyc2) appeared to be the main factor underlying variation of barley by aleurone colour.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12870-017-1122-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: bHLH, Cytochrome P450, Flavonoid biosynthesis, Gene duplication, Hordeum, MBW, MYB, MYC, Transcription factor, WD40

Background

Flavonoids are natural biologically active compounds produced by plants. Flavonoid pigment anthocyanins are known for their plant protective functions [1, 2] and human health benefits [3, 4].

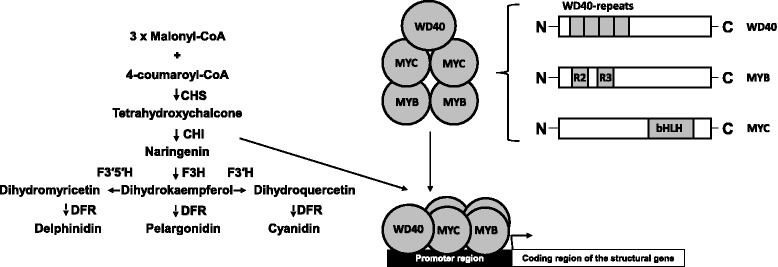

Diverse coloration patterns in plants are achieved through a wide variety of regulatory factors involved in the biosynthesis of flavonoid pigments. The activation of flavonoid biosynthesis occurs with the help of the MBW complex, which is composed of three types of transcription factors, MYB, bHLH/MYC and WD40 [5–7] (Fig. 1). These regulatory elements activate the structural genes encoding enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of flavonoids, providing tissue-specific accumulation of the pigment.

Fig. 1.

Scheme of anthocyanin biosynthesis (modified from [42]). MYB, MYC, WD40 – transcription factors. WD40-repeats, R2R3, bHLH – their functional domains. CHI – chalcone-flavanone isomerase; CHS – chalcone synthase; DFR – dihydroflavonol 4-reductase; F3H – flavanone 3-hydroxylase; F3’H – flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase; F3’5’H – flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) is an important agricultural crop. In natural populations, barley plants with different types of grain coloration are described. Purple, yellow and blue types of pigmentation are associated with the accumulation of flavonoid pigments in diverse layers of the grains. The purple colour of grain pericarp depends on the HvAnt2 gene. It is located on the long arm of chromosome 2H (2HL) and encodes the bHLH/MYC protein [8–10], which together with the MYB factor (putatively encoded by the HvMpc1/HvAnt1 gene (7HS) [11, 12]) activates the structural genes. The appearance of proanthocyanidin pigmentation in the barley seed coat is associated with expression of the HvAnt28 gene (3HL), encoding the MYB-type factor [13, 14]. The blue colour of the aleurone layer depends on the presence of five complementary genes that have not been sequenced yet: Blx1, Blx2, Blx3, Blx4 and Blx5. Three of these genes (Blx1, Blx3, Blx4) are closely linked to each other and were mapped to chromosome 4HL. Blx2 and Blx5 are located at chromosome 7HL [15]. A change of aleurone colour from blue to pink (red) occurs when complementary dominant alleles are present at the Blx1, Blx2, Blx3, and Blx5 loci but not at Blx4 [15].

MYB and MYC factors regulate anthocyanin synthesis in aleurone and their relation to the Blx genes are not yet known. The WD40 component of the barley MBW regulatory complex for anthocyanin synthesis has also not been identified and studied yet.

In the current study, we checked a database for barley sequences that have not been annotated to find and analyse genes encoding transcription factors MYC, MYB and WD40, which are related to anthocyanin synthesis in the aleurone layer, as well as F3′5′H – a putative candidate gene for Blx4.

Results

Identification, sequencing and study of the structural organization of the genes regulating anthocyanin synthesis in barley aleurone

bHLH/MYC

We found one copy of the MYC-encoding HvAnt2 gene (GenBank: KX035100) located on the long arm of chromosome 4H (Table 1). The predicted coding sequence (1683 bp in length) of the gene designated HvMyc2 shares 70.8% identity with HvAnt2.

Table 1.

The anthocyanin synthesis regulatory genes annotated for the first time in the current study

| Gene name | Protein type | CDS length, bp | Chromosome | Cultivar | Contig from IPK Barley BLAST Server | Exons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HvMyc2 | MYC/bHLH | 1683 | 4HL | Bowman | 106,753 | e1-e5 |

| 10,625 | e6-e8 | |||||

| Morex | 1,563,805 | e1-e5 | ||||

| 442,143 | e6-e8 | |||||

| Barke | 430,151 | e1-e2 | ||||

| 55,550 | e3-e5 | |||||

| 2,789,433 | e6-e8 | |||||

| HvMpc2 | MYB | 711 | 4HL | Bowman | 110,138 | e1-e2 |

| Morex | 317,820 | e1-e2 | ||||

| Barke | 401,169 | e1-partially e2 | ||||

| 395,048 | partially e2 | |||||

| HvWD40 | WD40 | 1071 | 6HL | Bowman | 849,119 | e1 |

| Morex | 39,083 | e1 | ||||

| HvF3’5’H | Cytochrome P450 | 1440 | 4HL | Bowman | 855,926 | e1-e3 |

| Morex | 1,575,914 | e1-e3 |

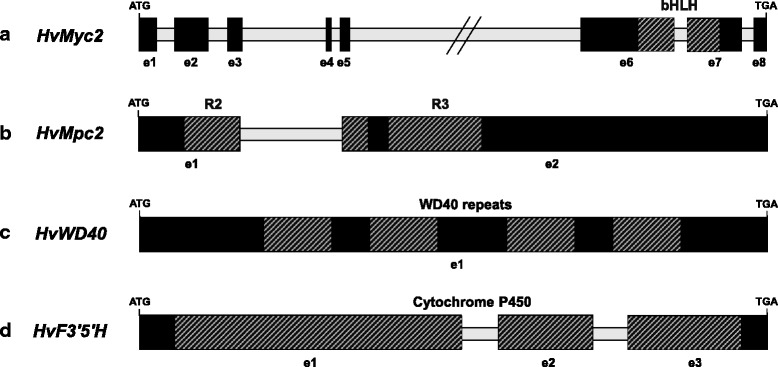

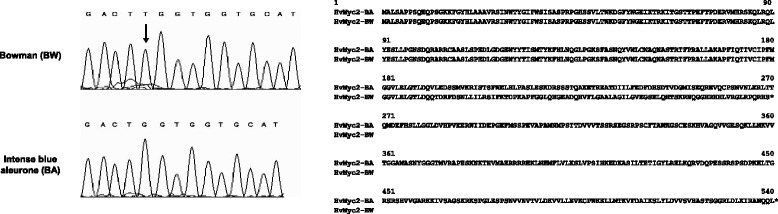

The complete coding sequence of HvMyc2 was obtained. It consists of eight exons. The 6th and 7th exons contain the conservative MYC-type bHLH domain required for gene activation through binding with DNA and protein (Fig. 2). Comparison of HvMyc2 sequences of BW and BA near-isogenic lines differing by the Ba gene allelic state, showed several synonymous single nucleotide substitutions and one single nucleotide deletion (58 bp upstream bHLH-encoding motif), resulting in a frame-shift in uncoloured BW (Fig. 3). Sequencing of the partial HvMyc2 gene in the parents of the mapping population (DOM and REC) revealed the same loss-of-function mutation in the uncoloured REC parent. We developed a CAPS marker specific for the functional HvMyc2-BA allele and used it for amplification of DNA from different barley varieties having a blue or uncoloured aleurone colour. The HvMyc2-BA was present in all blue-grained barleys and in two genotypes with uncoloured aleurone (OWB_03 and OWB_28) (Additional file 1). The presence of the HvMyc2-BA allele in some samples lacking anthocyanin synthesis in aleurone can be explained either by other mutations in HvMyc2 or by putative loss-of-function mutations in other anthocyanin biosynthesis genes.

Fig. 2.

Structural organization of the genes: a HvMyc2; b HvMpc2; c HvWD40; d HvF3’5’H. striped boxes indicate functional domains: Myc-type basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain (InterPro: IPR011598); Myb-like DNA-binding domain (InterPro: PF00249); WD40 repeats (InterPro: SM00320) and WD domain, G-beta repeat (InterPro: PF00400); Cytochrome P450, E-class, group I (InterPro: IPR002401)

Fig. 3.

The single nucleotide insertion in the gene HvMyc2 and alignment of predicted amino acid sequences of the HvMyc2-BA and HvMyc2-BW alleles

MYB

The full-length gene sequence (861 bp) with 69.0% identity to the R2R3 MYB-encoding gene HvAnt1 (GenBank:KP265977) was found on the 4HL chromosome (Table 1). The gene was designated HvMpc2. The HvMpc2 gene was re-sequenced in BW, BA, DOM and REC. The gene consisted of two exons (Fig. 2) and carried R2- and R3-motifs required for polyphenol biosynthesis. The coding sequences of coloured (BA, DOM) and uncoloured (BW, REC) genotypes contained only synonymous single nucleotide substitutions. Some indels were revealed in the promoter region (Additional file 2).

WD40

After BLAST analysis, using sequences of the WD40-encoding genes of maize (GenBank: AY115485 [16]) and sorghum (GenBank: JX122967 [17]), we found the orthologous gene (full-length sequence 1071 bp in length) on barley chromosome 6HL (with a level of identity 87.0% compared to maize ZmPAC1 and 87.8% with sorghum SbTan1) (Table 1). The gene was designated HvWD40. HvWD40 was re-sequenced in BW, BA, DOM and REC. The gene lacked introns and contained four WD40 repeats with Trp-Asp (WD) doublet residues at the C-terminus (Fig. 2). Four genotypes that were sequenced differed from each other by synonymous single nucleotide substitutions only.

F3’5’H

Our search in databases was based on sequences of F3’5’H genes of dicots: grape (GenBank: NM_001281235), lycium (GenBank: KC161969), soybean (GenBank: EF174665), blackcurrant (GenBank: KC493688), balloon flower (GenBank: JQ403611), cyclamen (GenBank: GQ891056) (several sequences for BLAST search were taken for cross-validation). The sequence (full-length 1689 bp in length) with the highest identity was found on chromosome 4HL, where Blx4 is located (Table 1). This gene was designated HvF3’5’H. The coding region of HvF3’5’H was separated into three exons (Fig. 2). It contained a cytochrome P450 motif (InterPro: IPR002401). BW, BA, DOM and REC differed from each other by synonymous single nucleotide substitutions only.

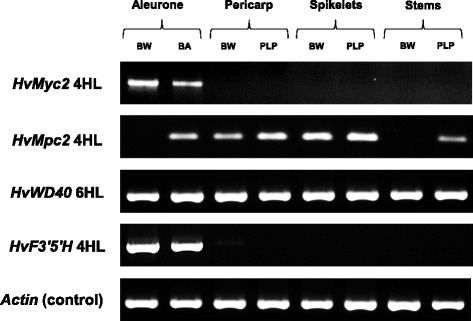

RT-PCR analysis of transcriptional activity of the studied genes

Tissue-specific expression of HvMyc2 and HvF3’5’H genes was observed in the aleurone layer, both in coloured and uncoloured near-isogenic lines (Fig. 4). They were not transcribed in the pericarp nor in the lemma (with developing spikelets) and stem (with leaf sheath). Unlike aleurone-specific HvMyc2 and HvF3’5’H, the HvMpc2 gene was expressed in all mentioned tissues; however, its activity was not detected in non-coloured aleurone in contrast to coloured aleurone. HvWD40 transcripts were observed in all analysed cDNA samples (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Expression of the HvMyc2, HvMpc2, HvWD40 and HvF3’5’H genes in the aleurone layer, pericarp, lemmas (with developing spikelets) and stems (with leaf sheaths) of NILs differing by coloration

Molecular mapping

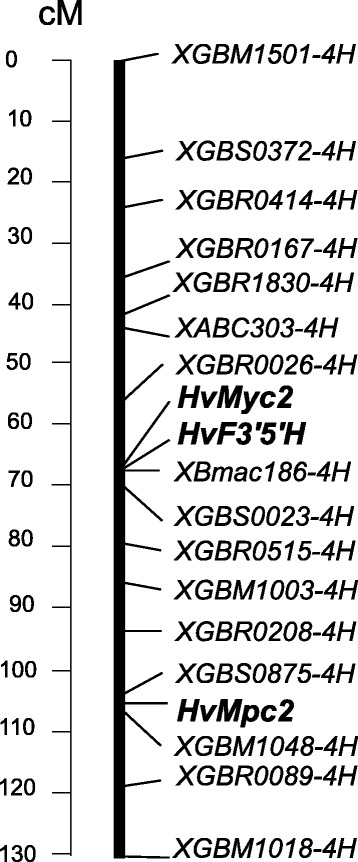

For molecular mapping, we selected the Oregon Wolfe Barley (OWB) population. This population of doubled-haploid lines was segregated for anthocyanin grain coloration and for the HvMyc2-BA specific CAPS marker (Table 2). Forty-four lines carried HvMyc2-BA, while 48 lines lacked it. The segregation ratio matched the expected 1:1 (χ2 = 0.17; P > 0.50). We used HvMyc2-BA genotyping data together with available SSR- and RFLP-loci data for linkage analysis. The gene HvMyc2 was closely linked to the SSR locus XBmac186-4H. Similarly, for mapping HvMpc2 and HvF3’5’H, CAPS-markers were developed (based on single nucleotide polymorphisms between DOM and REC) (Fig. 3). The segregation ratio for HvMpc2 (44:48) and HvF3’5’H (44:48) matched the expected 1:1 (χ2 = 0,17; P > 0.50 for HvMpc2; χ2 = 0,17; P > 0.50 for HvF3’5’H). The HvF3’5’H gene mapped closely to XBmac186-4H and HvMyc2, while HvMpc2 mapped between SSR loci XGBS0875-4H (3.4 cM distal) and XGBM1048-4H (3.4 cM proximal) (Fig. 5).

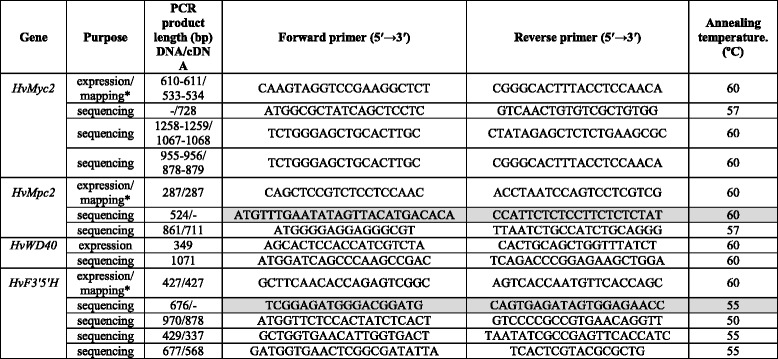

Table 2.

Gene-specific primers used for amplification of barley DNA. For primer design, the contigs sequences mentioned in Table 1 were used. Primer pairs used for promoter region sequencing are shaded by a grey colour

*For molecular mapping, amplified fragments of the mapping population individuals were digested with restriction endonucleases Bse1 I, Hga I and EcoR I respectively (CAPS –analysis)

Fig. 5.

Molecular-genetic mapping of the HvMyc2, HvF3’5’H and HvMpc2 genes on barley chromosome 4H

Discussion

Duplications are the main source of new genes in genomes – approximately 90% of genes found in eukaryotes are the result of duplications [18, 19]. The retention of transcription factors after gene duplication suggest that the expansion of transcription factor (TF) families may provide adaptive benefits [20]. The proteins of the MYB family belong to the most numerous class, and the bHLH proteins are the second largest class of transcription factor families among the plant classifications. The proteins bHLH and MYB interact with the protein WD40, forming a highly dynamic complex MYB/bHLH/WD40 (MBW). These complexes regulate various cellular processes such as responses to the biotic and abiotic stresses, formation of root hairs and trichomes, and synthesis of phenolic compounds including flavonoids [5–7]. In barley, not all of the MYB and MYC factors, which are involved in flavonoid biosynthesis, have been identified and described. The data on structural and functional organization and chromosome localization of barley WD40-encoding genes is missing. In the current study, we identified and characterized components of the MBW complex for anthocyanin synthesis in aleurone cells of barley grain.

The bHLH/MYC encoding gene identified in the current study (HvMyc2 on chromosome 4HL) appeared to be a paralogous copy of the HvAnt2 gene conferring purple pericarp colour and it was located on chromosome 2H. An earlier study aimed to identify copies of the gene TaMyc1, which regulates anthocyanin synthesis in wheat pericarp. The study discovered 11 copies of homoeologous group 2 and homoeologous group 4 chromosomes [21]. It was concluded that the first duplication of the Myc gene occurred in the common ancestor of the Triticeae tribe [21]. HvMyc2, which was identified in the current study, likely originated from the duplicated Myc gene on the ancestor’s chromosome 4 and is likely an orthologue of some of the TaMyc1 copies localized on chromosomes 4AL, 4BL and 4DL. Among wheat species, the Ba gene for blue aleurone was found in Triticum boeoticum only [22]. Bread wheat (T. aestivum) may have blue aleurone colour only due to substitution of one of the homoeologous group 4 chromosomes by chromosome 4Ag of Agropyron [22]. In barley, chromosome 4H is known to be responsible for blue aleurone control [15, 23] and carries an orthologue of the Ba genes of T. boeoticum and Agropyron. Our findings suggest that the MYC-encoding gene (HvMyc2) is the main component of the regulatory network underlying barley variation by aleurone colour. First, we observed specific expression of this gene in aleurone only, while other candidate genes did not show such specificity (Fig. 4). Second, we have found a loss-of-function (reading frame shift; Fig. 3) mutation in most barley samples having uncoloured aleurone (Additional file 1). Furthermore, comparison of the HvMyc2 precise position on chromosome 4HL with that of the Blx1/Blx3/Blx4 cluster [15, 23, 24] resulted in a conclusion about their colocalization. We suggest HvMyc2 is a candidate gene for Blx1 or Blx3, while HvF3’5’H was proved to be Blx4. It is known that loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding the F3’5’H enzyme result in lack of the ‘blue’ fraction of anthocyanins [25] and that mutation of Blx4 results in a change of aleurone colour from blue to pink (red) [15]. Furthermore, HvF3’5’H is colocalized with the Blx4 gene (Fig. 5, [24]).

Like HvMyc2, the HvF3’5’H has aleurone specific expression (Fig. 4). Tissue-specific expression of a structural gene may indicate the presence of a potential duplicated copy. For example, two paralogous copies of the flavonoid biosynthesis F3 h gene occur in some Triticeae species, with one copy specifically expressed in roots and the second copy active in other parts of the plant [26]. We suggest that the barley genome should contain another F3′5′H copy due to delphinidin derivate accumulation, not only in the aleurone layer but also, for example, in pericarps and stems [8, 12]. The presence of two F3′5′H copies is not rare within plant species.

The MYB-encoding gene HvMpc2 identified in the current study on chromosome 4HL appeared to be located distal to the Blx1/Blx3/Blx4 cluster. This gene could be an orthologue of some of the wheat TaPL1 gene copies on 4BL and 4DL chromosomes [27]. HvMpc2 is expressed in several parts of barley plants and shows no specificity to aleurone. Nevertheless, the product of the HvMpc2 gene is assumed to be a part of a regulatory anthocyanin synthesis BMW complex in aleurone, since HvMpc2 encodes a MYB-like transcriptional factor that shows high similarity to HvMpc1 (which regulates biosynthesis of anthocyanins in the purple leaf sheath [12]) and because HvMpc2 expression correlates with aleurone colour (Fig. 4). Location of HvMpc1 (7HS) is distinct from that of Blx2 and Blx5 on 7HL (Blx2 and Blx5 products remain unknown; probably they encode enzymes necessary for anthocyanin molecule modifications). Thus, both MYB-encoding anthocyanin regulatory genes in barley (HvMpc1 and HvMpc2) do not colocalize with Blx genes and are not related to variation in blue aleurone colour of barley. Variation of anthocyanin pigmentation in different parts of plants is usually caused by mutations of MYB-encoding genes, while the MYC-encoding partner is more conservative. The leading role of the MYB-encoding gene variability in phenotypic variation was observed in wheat coleoptiles, stems, leaf sheaths, leaf blades and anthers [28, 29] and barley leaf sheaths [12]. In the case of pericarp coloration, both MYB- and MYC-encoding regulatory genes contribute to phenotypic variation [30, 31], while in the case of aleurone coloration, the Myc-gene contribution is essential (current study).

In addition, we identified the WD40-coding gene, which was designated HvWD40 (6HL). The single-copy gene HvWD40 that encodes the required component of the regulatory MBW complex was expressed constantly in coloured and non-coloured tissues, and had no allelic differences. Proteins of this class are involved in a variety of cellular processes, which is probably the reason why they are specified by high conservatism [32]. WD40 genes of other plant species (potato, for example) share a similar expression profile, which does not correlate with tissue-specificity or the intensity of tissue colour.

We assume that HvWD40 together with HvMpc2 and HvMyc2 forms the MBW regulatory complex, which is necessary for activation of the structural anthocyanin biosynthesis genes in aleurone, while with HvAnt1 and HvAnt2, it forms the MBW complex that is necessary for regulation of anthocyanin synthesis in pericarps.

Conclusions

Genes involved in anthocyanin synthesis in the barley aleurone layer were identified and characterized, including components of the MBW regulatory complex, from which the MYC-encoding gene (HvMyc2) appeared to be the main factor underlying variation of barley aleurone colour.

Methods

Plant material

Two parental lines (DOM and REC) and 92 plants from the barley mapping population Oregon Wolfe Barleys (OWB) [33], three Bowman’s near-isogenic lines (NILs) (Table 3), nine cultivars from the ICG collection “GenAgro” (Novosibirsk, Russia) and two accessions from IPK GenBank (Gaterslebendeclar, Germany) were screened for the presence of the HvMyc2-BA allele (Additional file 1). The three NILs were exploited for gene expression analysis. DOM, REC, BW and BA were also used for sequencing. The plants were grown in ICG Greenhouse Core Facilities (Novosibirsk, Russia) under a 12 h photoperiod at 20–25 °C.

Table 3.

Hordeum vulgare ‘Bowman’ near-isogenic lines (NILs) that were used and their phenotypic characteristics

| Line designation | NGB* ID | Phenotype of analysed tissue | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aleurone | Pericarp | Lemma | First leaf sheath | ||

| BW (Bowman) | NGB22812 | uncoloured | uncoloured | uncoloured | uncoloured |

| BA (Blue aleurone) | NGB20651 | blue | uncoloured | uncoloured | purple |

| PLP (Purple lemma and pericarp) | NGB22213 | uncoloured | purple | purple | purple |

*NGB – Nordic GenBank

Gene identification and in silico analysis

A database search for homologous sequences was carried out for not annotated barley sequences deposited at the IPK Barley BLAST Server (http://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/barley_ibsc/) using software provided at this Server [34]. Annotation of the detected sequences was performed using the FGENESH+ program [35] and confirmed by cDNAs sequencing. Alignment of nucleotide and amino acid sequences was made using the MULTALIN v5.4.1 program [36]. Barley genes HvAnt2 (GenBank: KX035100) and HvAnt1 (GenBank: KP265977) were used to identify Myc-like and Myb-like sequences, respectively. The search for the WD40-coding gene was made with the maize ZmPAC1 (GenBank: AY115485) and the sorghum SbTan1 (GenBank: JX122967) genes. For identification of the gene encoding F3′5′H a search was done using known F3′5′H gene sequences of dicot plants species: VvF3’5’H (GenBank: NM_001281235), LrF3’5’H (GenBank: KC161969), GmW1 (GenBank: EF174665), RnF35H (GenBank: KC493688), PgF3’5’H (GenBank: JQ403611), and CpF3’5’H (GenBank: GQ891056). Amino acid sequences were predicted using InterPro [37]. The exon-intronic structure of the genes was predicted with FGENESH+ software [35] using polypeptide sequences of homologous genes HvAnt2, HvAnt1, ZmPAC1 and VvF3’5’H.

DNA and RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis

Total genomic DNA was extracted from fresh leaves of plants following a procedure described earlier [38]. Pericarps and aleurones for RNA extraction were scalpeled from grains at early dough stage maturity (BBCH code 83) for BW and BA lines. RNAs from pericarp as well as from lemmas (with developing spikelets; collected at the end of flowering; BBCH code 69) and stems (with leaf sheaths; collected at the same stage) were extracted applying a ZR Plant RNA MiniPrep™ (Zymo Research, USA). RNAs from aleurone layer samples were extracted using a RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany). All isolated RNAs were treated with RNase-free DNase set (QIAGEN, Germany). Total RNA was converted to single-stranded cDNA in a 20-μL reaction from a template consisting of 0.2 μg of total RNA using a RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA).

PCR, restriction and sequence analysis

Amplification of gDNA and cDNA was made in 20 μL PCRs. Reaction mixtures contained 50–100 ng of genomic template DNA, 1 ng of each of primer, 0.25 mM of each dNTP, 1× reaction buffer (67 mM TrisHCl, pH 8.8; 2 mM MgCl2; 18 mM (NH4)2SO4; 0.01% Tween 20) and 1 U Taq polymerase. DNA templates were amplified with initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles were run at 94 °C for 1 min, 50-60 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 0.5-2 min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Primer design was carried out using the OLIGO7 program. PCR products were separated on agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light. The amplified fragments were purified from an agarose gel using a DNA Clean kit (Cytokine, St. Petersburg, Russia). To discriminate different alleles of the HvMyc2, HvMpc2 and HvF3’5’H loci, we developed CAPS markers. Corresponding PCR products (Table 2) were digested with restriction endonucleases Bse1 I, Hga I and EcoR I, respectively, followed by separation of DNA fragments in a 2-5% high resolution agarose gel (HydraGene Co., China) (Additional file 3). DNA sequencing was performed using the SB RAS Genomics core facilities (Novosibirsk, Russia). The full-length gene sequences were re-constructed from a series of the overlapping amplicons (Table 1). All obtained sequences were deposited in GenBank (NCBI).

Genetic mapping

Identified loci were mapped relative to RFLP and SSR loci of the Oregon Wolfe Barleys (OWBs) mapping population [33, 39]. The genes HvMyc2, HvF3’5’H and HvMpc2 were mapped using the gene-specific CAPS marker developed in the current study. Linkage maps were constructed with MAPMAKER 2.0 [40] using the Kosambi function [41].

Additional files

The presence of the HvMyc2-BA allele in barley Bowman NILs (1–2), parents of the mapping population used (3–4), recombinant DH lines of this population (5–96), accessions and cultivars from IPK Genbank (97–98) and ICG collection GenAgro (99–107). (PDF 149 kb)

Multiple alignment of the promoter regions of the barley HvMpc2 gene. (PDF 196 kb)

The results of genotyping of the mapping population (Oregon Wolfe Barleys, OWB) for molecular mapping of barley genes: A – HvMyc2 B – HvMpc2 C – HvF3’5’H. Amplified fragments of the mapping population individuals of were digested with restriction endonucleases Bse1 I, Hga I and EcoR I respectively (CAPS–analysis). DOM and REC are the parental lines. (PDF 327 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Galina Generalova and Mrs. Tatiana Kukoeva (ICG, Novosibirsk, Russia) for technical assistance.

Funding

This work was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (№ 16-14-00086). Growth of barley plants in the ICG Plant Growth Core Facility was supported by ICG project 0324-2016-0001.

Availability of data and materials

The sequences obtained in the current study are available at NCBI: MF679149-MF679162.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Plant Biology Volume 17 Supplement 1, 2017: Selected articles from PlantGen 2017. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcplantbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-17-supplement-1.

Authors’ contributions

KVS performed all molecular-genetic experiments, carried out in silico and statistical analysis, and participated in drafting the manuscript. AB provided plant material, contributed to the interpretation of data and to revising the manuscript critically. EKK contributed to the conception and design of the study, to interpretation of data and to revising the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12870-017-1122-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Ksenia V. Strygina, Email: pushpandzhali@bionet.nsc.ru

Andreas Börner, Email: boerner@ipk-gatersleben.de.

Elena K. Khlestkina, Email: khlest@bionet.nsc.ru

References

- 1.Pourcel L, Routaboul J-M, Cheynier V, Lepiniec L, Debeaujon I. Flavonoid oxidation in plants: from biochemical properties to physiological functions. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landi M, Tattini M, Gould KS. Multiple functional roles of anthocyanins in plant-environment interactions. Environ Exp Bot. 2015;199:4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2015.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li D, Wang P, Luo Y, Zhao M, Chen F. Health benefits of anthocyanins and molecular mechanisms: update from recent decade. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:1729–1741. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1030064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yousuf B, Gul K, Wani AA, Singh P. Health benefits of anthocyanins and their encapsulation for potential use in food systems: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56(3):2223–2230. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.805316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feller A, Machemer K, Braun EL, Grotewold E. Evolutionary and comparative analysis of MYB and bHLH plant transcription factors. Plant J. 2011;66(1):94–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu W, Dubos C, Lepiniec L. Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis by MYB–bHLH–WDR complexes. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20(3):176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khlestkina EK, Shoeva OY, Gordeeva EI. Flavonoid biosynthesis genes in wheat. Russ J Genet Appl Res. 2015;5(3):268–278. doi: 10.1134/S2079059715030077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jende-Strid B. Genetic control of flavonoid biosynthesis in barley. Hereditas. 1993;3(5):187–204. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cockram J, White J, Zuluaga DL, Smith D, Comadran J, Macaulay M, Luo Z, Kearsey MJ, Werner P, Harrap D, Tapsell C, Liu H, Hedley PE, Stein N, Schulte D, Steuernagel B, Marshall DF, WTB T, Ramsay L, Mackay I, Balding DJ, AGOUEB Consortium. Waugh R, O’Sullivan DM. Genome-wide association mapping to candidate polymorphism resolution in the unsequenced barley genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(50):21611–21616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010179107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shoeva OY, Mock H-P, Kukoeva TV, Börner A, Khlestkina EK. Regulation of the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway genes in purple and black grains of Hordeum vulgare. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0163782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Himi E, Taketa S. Isolation of candidate genes for the barley Ant1 and wheat Rc genes controlling anthocyanin pigmentation in different vegetative tissues. Mol Gen Genomics. 2015;290(4):1287–1298. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-0991-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shoeva OY, Kukoeva TV, Börner A, Khlestkina EK. Barley Ant1 is a homolog of maize C1 and its product is part of the regulatory machinery governing anthocyanin synthesis in the leaf sheath. Plant Breed. 2015;134(4):400–405. doi: 10.1111/pbr.12277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Himi E, Yamashita Y, Haruyama N, Yanagisawa T, Maekawa M, Taketa S. Ant28 gene for proanthocyanidin synthesis encoding the R2R3 MYB domain protein (Hvmyb10) highly affects grain dormancy in barley. Euphytica. 2012;188(1):141–151. doi: 10.1007/s10681-011-0552-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garvin DF, Miller-Garvin JE, Viccars EA, Jacobsen JV, Brown AHD. Identification of molecular markers linked to ant28-484, a mutation that eliminates proanthocyanidin production in barley seeds. Crop Sci. 1998;38(5):1250–1255. doi: 10.2135/cropsci1998.0011183X003800050023x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finch RA, Simpson E. New colours and complementary colour genes in barley. Z Pflanzenzücht. 1978;81(1):40–53. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carey CC, Strahle JT, Selinger DA, Chandler VL. Mutations in the pale aleurone color1 regulatory gene of the Zea mays anthocyanin pathway have distinct phenotypes relative to the functionally similar TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 gene in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2004;16(2):450–464. doi: 10.1105/tpc.018796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Y, Li X, Xiang W, Zhu C, Lin Z, Wu Y, Li J, Pandravada S, Ridder DD, Bai G, Wang ML, Trick HN, Bean SR, Tuinstra MR, Tesso TT, Yu J. Presence of tannins in sorghum grains is conditioned by different natural alleles of Tannin1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(26):10281–10286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201700109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohno S. Evolution by gene duplication. New York: Springer Verlag; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brenner SE, Hubbard T, Murzin A, Chothia C. Gene duplications in H. influenzae. Nature. 1995;378(6553):140. doi: 10.1038/378140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang D, Weiche B, Timmerhaus G, Richardt S, Riaño-Pachón DM, Corrêa LGG, Reski R, Mueller-Roeber B, Rensing SA. Genome-wide phylogenetic comparative analysis of plant transcriptional regulation: a timeline of loss, gain, expansion, and correlation with complexity. Genome Biol Evol. 2010;2:488–503. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strygina KV, Khlestkina EK. Myc gene family in cereals: transformation in the course of the evolution of hexaploid bread wheat and its relatives. Mol Biol. 2017;51(5):572–579. doi: 10.1134/S0026893317050181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeven AC. Wheats with purple and blue grains: a review. Euphytica. 1991;56(3):243–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00042371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mullick DB, Faris DG, Brink VC, Acheson RM. Anthocyanins and anthocyanidins of the barley pericarp and aleurone tissues. Can J Plant Sci. 1958;38(4):445–456. doi: 10.4141/cjps58-071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Sullivan H. GrainGenes: a genomic database for Triticeae and Avena. In: Edwards D, editor. Plant bioinformatics: methods and protocols. Methods in molecular biology. 2007. pp. 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grotewold E. The genetics and biochemistry of floral pigments. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:761–780. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khlestkina EK, Dobrovolskaya OB, Leonova IN, Salina EA. Diversification of the duplicated F3h genes in Triticeae. J Mol Evol. 2013;76(4):261–266. doi: 10.1007/s00239-013-9554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin DH, Choi MG, Kang CS, Park CS, Choi SB, Park YI. A wheat R2R3-MYB protein PURPLE PLANT1 (TaPL1) functions as a positive regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;469(3):686–691. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khlestkina EK. Genes determining the coloration of different organs in wheat. Russ J Genet Appl Res. 2013;3(1):54–65. doi: 10.1134/S2079059713010085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adzhieva VF, Babak OG, Shoeva OY, Kilchevsky AV, Khlestkina EK. Molecular genetic mechanisms of the development of fruit and seed coloration in plants. Russ J Genet Appl Res. 2016;6(5):537–552. doi: 10.1134/S2079059716050026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khlestkina EK, Röder MS, Börner A. Mapping genes controlling anthocyanin pigmentation on the glume and pericarp in tetraploid wheat (Triticum durum L.) Euphytica. 2010;171(1):65–69. doi: 10.1007/s10681-009-9994-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shoeva OY, Gordeeva EI, Khlestkina EK. The regulation of anthocyanin synthesis in the wheat pericarp. Molecules. 2014;19(12):20266–20279. doi: 10.3390/molecules191220266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neer EJ, Schmidt CJ, Nambudripad R, Smith TF. The ancient regulatory-protein family of WD-repeat proteins. Nature. 1994;371(6495):297–300. doi: 10.1038/371297a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa JM, Corey A, Hayes PM, Jobet C, Kleinhofs A, Kopisch-Obusch A, Kramer SF, Kudrna D, Li M, Riera-Lizarazu O, Sato K, Szucs P, Toojinda T, Vales MI, Wolfe RI. Molecular mapping of the Oregon Wolfe barleys: a phenotypically polymorphic doubled-haploid population. Theor Appl Genet. 2001;103(2–3):415–424. doi: 10.1007/s001220100622. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng W, Nickle DC, Learn GH, Maust B, Mullins JI. ViroBLAST: a stand-alone BLAST web server for flexible queries of multiple databases and user's datasets. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(17):2334–2336. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solovyev V. Statistical approaches in eukaryotic gene prediction. In: D. J. Balding, M. Bishop, C. Cannings Eds Handbook of statistical genetics. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2008; doi:10.1002/9780470061619.ch4.

- 36.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucl Acids Res. 1988;6(22):10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finn RD, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, Bateman A, Bork P, Bridge AJ, Chang H-Y, Dosztányi Z, El-Gebali S, Fraser M, Gough J, Haft D, Holliday GL, Huang H, Huang X, Letunic I, Lopez R, Lu S, Marchler-Bauer A, Mi H, Mistry J, Natale DA, Necci M, Nuka G, Orengo CA, Park Y, Pesseat S, Piovesan D, Potter SC, Rawlings ND, Redaschi N, Richardson L, Rivoire C, Sangrador-Vegas A, Sigrist C, Sillitoe I, Smithers B, Squizzato S, Sutton G, Thanki N, Thomas PD, Tosatto SCE, Wu CH, Xenarios I, Yeh LS, Young SY, Mitchell AL. InterPro in 2017—beyond protein family and domain annotations.Nucl Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D190-D199; doi:10.1093/nar/gkw1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Plaschke J, Ganal MW, Röder MS. Detection of genetic diversity in closely related bread wheat using microsatellite markers. Theor Appl Genet. 1995;91(6):1001–1007. doi: 10.1007/BF00223912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stein N, Prasad M, Scholz U, Thiel T, Zhang H, Wolf M, Kota R, Varshney RK, Perovic D, Grosse I, Graner A. A 1,000-loci transcript map of the barley genome: new anchoring points for integrative grass genomics. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;114(5):823–839. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0480-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lander ES, Green P, Abrahamson J, Barlow A, Daly MJ, Lincoln SE, Newburg I. MAPMAKER: an interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics. 1987;1(2):174–181. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(87)90010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kosambi DD. The estimation of map distances from recombination values. Ann Eugenics. 1944;12(1):172–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1943.tb02321.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuhn N, Guan L, Dai ZW, Wu BH, Lauvergeat V, Gomès E, Li SH, Godoy F, Arce-Johnson P, Delrot S. Berry ripening: recently heard through the grapevine. J Exp Bot. 2013;65(16):4543–4559. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The presence of the HvMyc2-BA allele in barley Bowman NILs (1–2), parents of the mapping population used (3–4), recombinant DH lines of this population (5–96), accessions and cultivars from IPK Genbank (97–98) and ICG collection GenAgro (99–107). (PDF 149 kb)

Multiple alignment of the promoter regions of the barley HvMpc2 gene. (PDF 196 kb)

The results of genotyping of the mapping population (Oregon Wolfe Barleys, OWB) for molecular mapping of barley genes: A – HvMyc2 B – HvMpc2 C – HvF3’5’H. Amplified fragments of the mapping population individuals of were digested with restriction endonucleases Bse1 I, Hga I and EcoR I respectively (CAPS–analysis). DOM and REC are the parental lines. (PDF 327 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The sequences obtained in the current study are available at NCBI: MF679149-MF679162.