Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of home visiting programmes that offer health promotion and preventive care to older people.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies of home visiting.

Participants

Older people living at home, including frail older people at risk of adverse outcomes.

Outcome measures

Mortality, admission to hospital, admission to institutional care, functional status, health status.

Results

Home visiting was associated with a significant reduction in mortality. The pooled odds ratio for eight studies that assessed mortality in members of the general elderly population was 0.76 (95% confidence interval 0.64 to 0.89). Five studies of home visiting to frail older people who were at risk of adverse outcomes also showed a significant reduction in mortality (0.72; 0.54 to 0.97). Home visiting was associated with a significant reduction in admissions to long term care in members of the general elderly population (0.65; 0.46 to 0.91). For three studies of home visiting to frail, “at risk” older people, the pooled odds ratio was 0.55 (0.35 to 0.88). Meta-analysis of six studies of home visiting to members of the general elderly population showed no significant reduction in admissions to hospital (odds ratio 0.95; 0.80 to 1.09). Three studies showed no significant effect on health (standardised effect size 0.06; –0.07 to 0.18). Four studies showed no effect on activities of daily living (0.05; –0.07 to 0.17).

Conclusion

Home visits to older people can reduce mortality and admission to long term institutional care.

What is already known on this topic

The benefits of regular, preventive home visits to older people are the subject of controversy

A recent systematic review found no clear evidence that preventive home visits were effective

What this study adds

This meta-analysis of 15 trials shows that home visiting can reduce mortality and admission to institutional care among older people

Introduction

The objective of enabling older people to remain in their own homes has been a cornerstone of government policy for several decades. A recent royal commission on long term care has endorsed this objective, recommending that more emphasis be given to health promotion and other preventive measures as a means of delaying the onset of illness and dependency that eventually lead older people to need long term care.1

One way of promoting health and delivering preventive care to older people is through regular home visiting. Several studies of home visits by teams based in general practices have shown promising results, with home visitors identifying a large number of previously unmet medical and social needs.2–7 Health visitors are well placed to promote the health of older people and to provide surveillance and support. Although British health visitors have historically provided services to mothers and young children rather than older people, the potential of the health visitor in meeting the needs of older people in the community has been widely recognised.8,9 Despite this, today's generic health visitor devotes little time to older people.10–12

Two previous systematic reviews examined the effectiveness of home visits to older people. In 1993, Stuck et al performed a meta-analysis of 28 controlled trials that evaluated the outcomes of comprehensive geriatric assessment.13 The 28 studies were each allocated to one of five types of assessment, two of which involved home visits to older people. They reviewed nine trials of such visits.7,14–21 They found significant positive effects of home visiting on mortality, hospital admission and readmission, and nursing home placements.13 A second systematic review of 15 trials of preventive home visits to older people was undertaken more recently by van Haastregt et al.22 This review, unlike that of Stuck et al, did not involve meta-analysis of the 15 trials.7,14–18,23–30 Van Haastregt et al found no consistent evidence that preventive home visits had a significant effect on any outcome.22

Both these previous reviews have limitations. Stuck et al13 did not include five controlled trials of home visiting to older people, all of which were published at the time they undertook their meta-analysis but which we assume did not meet their inclusion criterion of involving comprehensive geriatric assessment.24,26,31–33 In the review by van Haastregt et al, the failure to pool the results of the trials was a considerable limitation. The fact that meta-analysis was not performed means that it is possible that significant effects were not detected, and this may in part explain their less positive results.

In view of the shortcomings of previous reviews, and the lack of consistency between their findings, we thought it important to undertake a meta-analysis of all relevant studies available to date to clarify the benefits of preventive home visiting. We report the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Method

As part of a larger systematic review to assess the effects of home visiting to all client groups, including parents and children, we reviewed studies on the effects of home visits to older people (aged 65 years and above). We have presented only those results relating to older people.

Search strategy

We searched Medline for 1966-97, CINAHL for 1982-97, and Embase for 1980-97. We also searched the Cochrane Library and the internet. We hand searched the journal Health Visitor for 1982-97 and scanned reference lists of review articles for relevant literature. We contacted key individuals and organisations to trace unpublished work and placed advertisements in relevant journals to identify unpublished work.

Inclusion criteria

Papers were included in the review if they reported an empirical study, with a comparison group, evaluating a home visiting programme. Randomised and non-randomised controlled trials were included. The home visitor had to undertake tasks within the scope of British health visitors—namely, surveillance, support, health promotion, and the prevention of ill health. The intervention had to involve the pursuit of a wide range of preventive outcomes rather than a single goal such as the prevention of falls or increased uptake of immunisation. We excluded studies in which the home visitor was a specialist in a branch of nursing other than health visiting (for example, community psychiatric nursing or district nursing) and those in which the intervention was delivered solely by volunteers. We also excluded studies that involved only screening and referral, with no other input from the home visitor. We obtained the full text of all studies identified by the search. Disagreements about whether a study met the inclusion criteria were settled through joint discussion of the research team.

We found 1215 references through the searches. Of these, 102 studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria, of which 15 studies reported outcomes relating to older people.15–17,19,23–35 Nine studies did not meet our inclusion criteria (table 1).7,14,18,20,29,30,36–38

Table 1.

Excluded studies

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Stuck et al 200038 | Published after end of period of review |

| Tinetti et al 199429 | Single objective of reducing falls |

| Wagner 199430 | Narrow objective of reducing falls and disability |

| Vetter et al 199218 | Single objective of reducing falls |

| Melin et al 199220 | Home visitors performed full nursing care rather than fulfilling health visitor role |

| Carpenter and Demopoulos 199014 | Home visits were undertaken solely by volunteers with no professional qualifications |

| Townsend et al 198836 | Home visitors performed full nursing care rather than fulfilling health visitor role |

| Sorensen and Sivertsen 19887 | Home visits undertaken by social workers performing only screening and referral role |

| Zimmer et al 198537 | Home visitors performed full nursing care rather than fulfilling health visitor role |

Quality rating

We assessed the quality of the studies included in the review by using the Reisch scale,39 which covers the purpose of the study (including prespecification of outcomes and expected effect sizes), experimental design, determination of sample size, description and suitability of treatment/management, masking, subject attrition, and evaluation of participants and treatment/management. The quality of the studies ranged from 0 to 1, with higher scores representing better quality studies. As there is no consensus about the cut off between good and bad studies, the score should be interpreted as indicating relative quality. Three members of the research team scored the papers for quality (DK, MH, MB); they were blind to the name of the publication, authors, results, and conclusions. All three reviewers applied the Reisch scale to 19 of the 102 articles to assess inter-rater reliability. The overall intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.74 (95% confidence interval 0.52 to 0.88).

Combining results

When outcomes were measured on a continuous scale we combined effect sizes using Hedges' method and computed an overall value of g (the standardised effect size).40 For categorical variables we combined odds ratios with the fixed effects Peto method.41

Outcomes included in meta-analyses

The 15 studies measured a wide range of outcomes. We performed a meta-analysis only when three or more studies reporting on the same outcome provided sufficient information for this to be undertaken. This meant that we could not use meta-analysis for psychological health, morale, quality of life, wellbeing, and referral to general practitioners and outside agencies. Several studies that examined the same outcomes that we assessed by meta-analysis did not provide enough information to be included (see table 4). Our review also included two studies that were not randomised.32,35 Findings from these studies were not entered into a meta-analysis (see table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes of home visits to elderly people: mortality, admission to hospital, health, functional ability, and long term institutional care

| Study | Mortality | Hospital admission and hospital stay | Health status | Functional status | Admission to long term institutional care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luker 198225 (UK) | NR | NR | Improvement in problems: 42% intervention 1, 48% intervention 2 Problem improvement score (intervention 1 v control 1) z=4.4, P<0.001 | NR | NR |

| Hendriksen 198415 (Denmark) | Intervention: 56/285; control: 75/287; P<0.05 | No of admissions: intervention 219, control 271, P<0.05 No of bed days: intervention 4884; control 6442, P=0.01 | NR | NR | Intervention 20/285, control 29/287, NS |

| Pathy 199216 (England) | Intervention: 67/369; control: 86/356; P<0.05 | No of admissions: intervention 262; control 284, NS Mean No days in hospital: intervention 12.5, control 14.6, NS | Health status: NS (no data given) Self rated health (mean score): intervention 6.9, control 6.4, P<0.05 | Functional ability: NS (no data given) | Intervention 20/369, control 28/356, NS |

| Vetter 198417 (Wales) | Intervention A: 45/281; control A: 45/273; NS Intervention B: 35/296; control B: 60/298; P<0.01 | NR | NR | Disability (test for trend): intervention and control A, NS, intervention and control B, NS | NR |

| Hansen 199219 (Denmark) | Intervention: 32/163; control: 43/181; NS | No with one or more readmissions: intervention 56/163, control 56/181, NS | NR | Intervention 16/163, control 29/181, P<0.05 | |

| Fabacher 199423 (USA) | Intervention: 4/118; control: 4/123; NS | No admitted: intervention 22/100, control 21/95, NS | NR | Mean score ADL: intervention 5.8, control 5.8, NS Mean score (1) IADL: intervention 7.1, control 6.7, P<0.05 | Intervention 0/100, control 0/195 |

| Hall 199224 (Canada) | Intervention: 14/81; control: 18/86; NS. No of “survivors” (neither died nor admitted to institutional care): intervention: 60/81; control: 51/86; P=0.054 | NR | NR | NR | Intervention 6/81, control 17/86, P<0.05 |

| McEwan 199026 (Britain) | Intervention: 16/151; control: 23/145; NS | NR | Physical health, percentage with problems: NS | ADL, percentage with problems NS | NR |

| Van Rossum 199327 (Netherlands) | Intervention: 42/292; control: 50/288; NS | No admitted to hospital: intervention 121/292, control 133/288, NS Mean No days per admission: intervention 20, control 20, NS | Mean change in self rated health score: intervention −0.4, control −0.6, NS | ADL mean change in score: intervention 0.4, control 0.3, NS | Intervention 7/292, control 5/288, NS |

| Stuck 199528 (USA) | Intervention: 24/215; control 26/199; P=0.80 | No admitted to hospital: intervention 99/215, control 93/199, NS | NR | Mean score ADL: intervention 96.8, control 95.4, P=0.10 Mean score IADL: intervention 72.3, control 69.3, P=0.02 | Intervention 9/215, control 20/199, P=0.02 |

| Balaban 198831 (USA) | Intervention: 31/103; control: 20/95; P=0.20 | Mean (SD) No of admissions: intervention 1.2 (1.2), control 0.6 (0.8), P<0.003 Mean (SD) No of days in hospital: intervention 6.2 (11.1), control 7.7 (21.7), NS | Health status (mean): intervention 5.7, control 6.0, P>0.50 | ADL (mean score): intervention 87, control 90, P>0.20 | NR |

| Oktay 199032 (USA) | Intervention: 27/98; control: 30/93; NS | Mean No of admissions: intervention 0.78, control 0.66, NS Mean No days in hospital: intervention 29.1, control 38.5, P<0.05 | NR | ADL: intervention −0.20, control −0.12, NS (1) ADL: intervention 0.10, control −0.05, NS | Intervention 10/98, control 11/93, NS |

| Williams 199233 (England) | Intervention: 30/231; control: 40/239; P>0.30 | NR | Mean physical status score at baseline (change over 12 months): intervention 5.7 (0.09), control 6.1 (0.09), NS | Mean disability score at baseline (change over 12 months): intervention 8.0 (2.1), control 7.8 (2.6), NS | NR |

| Dunn 199434 (England) | Intervention: 15/102; control: 25/102; P>0.10 | Mean length unplanned readmissions (days): intervention 12.1, control 14.0, P>0.05 | NR | NR | Intervention 8/102, control 7/102, NS |

| Archbold 199535 (USA) | NR | No admitted: intervention 6/11, control 5/11 Mean No days' stay: intervention 4.6, control 13.3 (no test results reported) | NR | NR | NR |

NR=not reported.

(I)ADL=(instrumental) activities of daily living.

NS=no significant difference between groups; actual P value not reported in original paper.

Meta-regression

In addition to meta-analysis we used meta-regression to see whether the effect sizes that we had extracted could be predicted by study characteristics. We regressed log odds ratios on the predictors, weighted by the inverse of sampling variance.42 We used three characteristics: population (the general population of older people v those at risk of adverse outcomes); duration of the intervention (up to two years v over two years); and age group (<75 v ⩾75 years).

Heterogeneity

Although the number of studies that reported any given outcome was small, we calculated formal tests of homogeneity41 (see figure legends). We did not see the use of random effects models as helpful here because the studies we examined were on different groups of participants and used interventions that were far from standardised, and so we believed the solution was to try to explain differences rather than to average what cannot be effectively averaged. We therefore carried out meta-regressions when there were sufficient studies.

Publication bias

We took no formal steps to look for publication bias, such as by plotting effect sizes or by calculating test statistics. In most cases there are few studies on any given effect, and any formal method would have had little power.

Results

Fifteen studies that met our inclusion criteria reported outcomes relating to older people; 13 were randomised controlled trials.15–17,19,23–34 The two others used a quasi-experimental design.32,35 The 15 studies were divided into two groups: one group of nine studies assessed members of the general elderly population,15–17,23,25–31 a second group of six studies assessed vulnerable older people who were at risk of adverse outcomes.19,24,32–35 The second group consisted of four studies of older people recently discharged from hospital who were at risk of further admissions19,32–34and two studies of frail older people who had been referred to home care agencies.24,35

The aims and content of the studies are shown in table 2. The characteristics of all 15 studies and their quality scores are shown in table 3. Details of the results of the studies are shown in table 4.

Table 2.

Aims, outcome measures, and content of interventions of studies included in review of home based support for older people

| Study | Aims | Outcome measures | Content of intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hendriksen 198415 (Denmark) | To assess effects of preventive home visits | Admission to hospital; admission to nursing homes; contacts with GP; home nursing care; receipt of social services | Social support, coordinating community services, distributing aids and modifications |

| Pathy 199216 (England) | To monitor effects of surveillance and case finding | Mortality; admission to hospital; admission to nursing homes; health status; functional status; quality of life | Practical advice, health education, referal to appropriate services |

| Vetter 198417 (Wales) | To test effectiveness of health visitors' visiting and monitor caseload | Mortality; health; wellbeing; functional status; access to other health and social services | Usual health visiting practice: health education, prevention, referal to other services |

| Hansen 199219 (Denmark) | To evaluate effects of home visiting | Mortality; readmission to hospital; admission to institutional care | Assessment, problem identification, referrals to GP if required. Follow up for medical and social problems, referral if required |

| Fabacher 199423 (USA) | To evaluate effectiveness of in-home geriatric assessments as means of providing preventive health care and improving health and functional status | Physical and mental health status; functional status; admission to hospital; admission to institutional care; immunisation | Screening for medical, functional, and psychosocial problems. Follow up letter (after initial visit from physician's assistant or nurse) with recommendations |

| Hall 199224 (Canada) | To assist older people to live longer at home | Mortality; admission to institutional care; psychological status | Developing personal health skills, goal setting, coordination of and referral to community services |

| Luker 198225 (UK) | To assess effects of focused health visitor intervention | Changes in problems (problems discussed under 10 headings: weight, mobility, dentition, sensory function, elimination, loneliness, performance of tasks, rest, medication, and miscellaneous) | Discussion of actual and potential health problems. Psychological support |

| McEwan 199026 (Britain) | To promote health, identify functional problems, prevent exacerbation of problems, and improve morale and wellbeing | Health status, self rated health; functional status; mortality; morale | Identification of problems, health promotion, advice, information, education, and referral |

| Van Rossum 199327 (Netherlands) | To assess effect of preventive home visits on health and use of services | Mortality; self rated health status; functional state; psychological state; wellbeing | Information, advice, social support |

| Stuck 199528 (USA) | To prevent disability | Functional status; hospital admission; admission to institutional care; use of community services; visits to physicians | Comprehensive assessment, health education, making recommendations, and monitoring compliance |

| Balaban 198831 (USA) | To improve function and wellbeing of patient and family | Health; morale and wellbeing; hospital admissions; function status; client satisfaction | Assessment of medical and social needs, diagnostic and therapeutic care, follow up after admission to hospital, referrals, education, and counselling |

| Oktay 199032 (USA) | To evaluate a post-hospital support programme for frail elderly people and their caregivers | Caregiver stress; mortality; functional status; health service utilisation | Assessment, case management, service coordination, counselling, referrals, respite, education, medical back up |

| Williams 199233 (England) | To evaluate effects of home visiting after discharge from hospital | Health status; mortality; use of hospital services | Practical help, providing aids, dealing with problems, companionship |

| Dunn 199434 (England) | To reduce unplanned hospital re-admissions in patients recently discharged from geriatric wards | Mortality; admission to institutional care; unplanned hospital readmission | Stabilise patients, deal with any problems |

| Archbold 199535 (USA) | To increase competence of family members providing care at home to frail older people | Caregiver role strain; caregiver rewards; use and cost of hospital services by older people | Increasing preparedness of caregiver, with emphasis on relationship between caregiver and care receiver |

Table 3.

Quality scores and characteristics of studies

| Study | Quality score | Design | Intervenors | Participants | Sample size, duration, and intensity of visits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hendriksen 198415 (Denmark) | 0.43 | RCT | Nurses | People aged ⩾75 years, living at home | Intervention: home visits (n=285), visits every 3 months for 3 years; control: no home visits (n=287) |

| Pathy 199216 (England) | 0.5 | RCT | Health visitors | Patients of general practice, aged ⩾65 years, living at home | Intervention: home visits to 60% of 369, for 3 years, frequency dependent on health visitors' judgment; control: no home visit (n=356) |

| Vetter 198417 (Wales) | 0.39 | RCT | Health visitors | Patients of two general practices, aged ⩾70 years | Intervention: A (rural practice) n=281; B (urban practice) n=296; home visits for A (528) and B (864) for 2 years, at least one visit per year, follow up visits on basis of need; control A (rural) n=273, B (urban) n=298, no home visits |

| Hansen 199219 (Denmark) | 0.36 | RCT | Nurse, GP | People aged ⩾75 years, discharged from hospital to own home | Intrevention: home visit (n=163) for 1 year, one visit by nurse, one by general practitioner; control: no home visit (n=181) |

| Fabacher 199423 (USA) | 0.57 | RCT | Nurse and trained volunteers | Veterans living in community, ⩾70 years | Intervention: home visits (n=131) for 1 year, visits four monthly, first visit undertaken by physician's assistant or nurse; control: no home visits (n=123) |

| Hall 199224 (Canada) | 0.61 | RCT | Nurse | Frail elderly people, aged ⩾65 years, living at home, newly admitted to community care programme | Intervention: home visits plus home health services (n=81) for 3 years, frequency dependent on need; control: home health services (n=86) |

| Luker 198225 (UK) | 0.46 | RCT (crossover) | Health visitor | Women aged ⩾70 years, living alone at home | Intervention 1: home visits (n=50) for 4 months, visits once monthy, mean length 34 mins; control 1: no home visits (n=50), (crossover: intervention 1=control 2, control 1=intervention 2) |

| McEwan 199026 (England) | 0.55 | RCT | Nurse | Patients of general practice, aged ⩾75 years | Intervention: home visits (n=151) for 20 months, one visit; control: no home visits (n=145) |

| Van Rossum 199327 (Netherlands) | 0.5 | RCT | Nurses | Patients of GP, aged 74-85 years, living at home | Intervention: home visits (n=292), for 3 years, four visits per year plus extra visits when necessary; 95 participants received 174 extra visits; control: no home visits (n=288) |

| Stuck 199528 (USA) | 0.65 | RCT | Gerontological nurse practitioners | People aged ⩾75, living in community | Intervention: home visits (n=215) for 3 years, visits three monthly; control: no home visits (n=199) |

| Balaban 198831 (USA) | 0.21 | RCT | Nurse, physician | Elderly or sick or disabled people living in community; 72% aged ⩾65 years; intervention: mean age 69 years, control 68 years | Intervention: home visits (n=103) for 2 years, mean No of visits 3.8 (year 1), 2.5 (year 2); control: routine care including occasional home visits (n=95), mean No of visits 0.2 (year 1), 0.9 (year 2) |

| Oktay 199032 (USA) | 0.5 | Quasi-experimental | Nurse and social worker | Patients aged ⩾65 years, discharged from hospital with post-hospital needs | Intervention: home visits (n=98); control: no home visits (n=93), for 1 year with minimum one nurse and one social worker visit per month, further visits dependent on need, mean of four nurse visits per month |

| Williams 199233 (England) | 0.46 | RCT | Health visitor's assistant | Patients >75, recently discharged from hospital | Intervention: home visits (n=231) for 1 year, eight visits; control: no home visits (n=239) |

| Dunn 199434 (England) | 0.54 | RCT | Health visitor | Patients discharged from hospital; mean age 83 years | Intervention: home visits (n=102), one visit, mean 72 hours after discharge; control: no home visits (n=102) |

| Archbold 199535 (USA) | 0.5 | Quasi-experimental | Nurses | Frail elderly preople, aged ⩾65 years, at home with carer, needing daily assistance | Intervention: home visits (n=11) for 3 to 6 months, average 11.5 visits per family; control: routine home health services (n=11) |

RCT=randomised controlled trial.

.

Findings

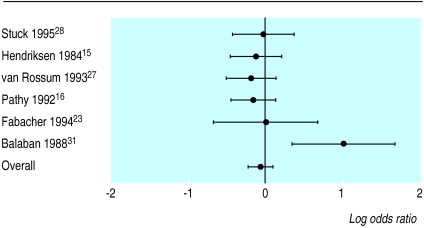

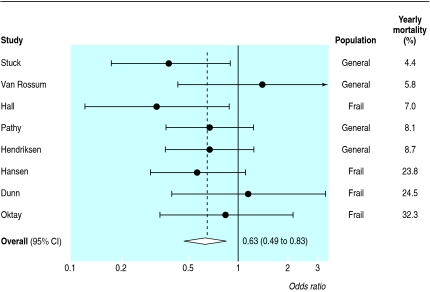

Of eight trials that measured mortality in elderly people in general,15–17,23,26–28,31 three reported significant reductions.15–17 Meta-analysis of these trials gave a pooled odds ratio of 0.76 (95% confidence interval 0.64 to 0.89), indicating that home visiting was associated with reduced mortality. Five studies assessed mortality among frail older people who were at risk of adverse outcomes. The pooled odds ratio of four randomised trials19,24,33,34 was 0.72 (0.54 to 0.97), again indicating that home visiting had a significant effect (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Log odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for mortality in general elderly population (test for homogeneity: Q=6.91, df=7, P=0.44) and frail elderly population (Q=0.87, df=3, P=0.83)

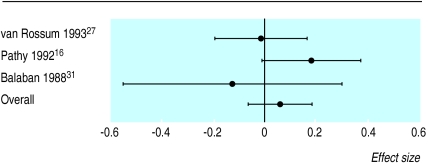

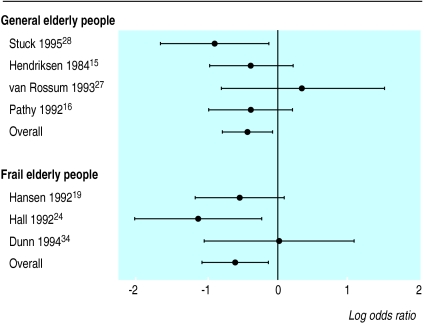

Of six studies that measured admissions to hospital in the general elderly population,15,16,23,27,28,31 only one reported a significant reduction.15 The pooled odds ratio for all six studies was 0.95 (0.80 to 1.09), suggesting that home visiting did not have a significant effect (fig 2). Three studies examined admission to hospital of frail elderly people who were considered “at risk.”19,32,35 Meta-analysis was not possible because insufficient information was provided. None found any significant effect. Five studies measured health status among the general elderly population,16,25–27,31 of which two reported improvements.16,25 Meta-analysis of the results of three studies16,27,31 showed no significant effects (standardised effect size 0.06, –0.07 to 0.18). Among the studies that assessed the at risk population, the only study that measured health status33 reported no significant effect (fig 3).

Figure 2.

Log odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for hospital admissions in general elderly population (test for homogeneity: Q=1.42, df=3, P=0.04)

Figure 3.

Effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals for health status (test for homogeneity: Q=2.89, df=2, P=0.24)

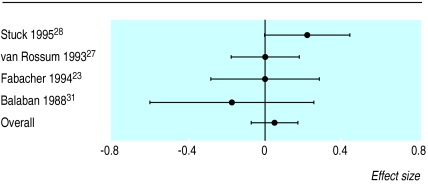

Seven studies measured functional ability in the general elderly population.16,17,23,26–28,31 None reported a significant improvement in activities of daily living or other similar measures of functional ability. However, the only two studies that measured instrumental activities of daily living23,28 both reported significant improvements. Meta-analysis of four studies that measured activities of daily living23,27,28,31 showed no significant effect (standardised effect size 0.05, –0.07 to 0.17). Of two studies that assessed functional ability among older people considered to be “at risk,”32,33 neither reported significant improvements (fig 4).

Figure 4.

Effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals for functional ability (test for homogeneity: Q=3.67, df=3, P=0.30)

Only one of five studies that reported admission to residential nursing homes of members of the general elderly population15,16,23,27,28 found a significant reduction.28 However, meta-analysis of the results of four of these studies15,16,27,28gave a pooled odds ratio of 0.65 (0.46 to 0.91), indicating that home visiting did have a significant effect in reducing admissions.

Of four studies reporting admission to institutional care of older people considered to be at risk,19,24,32,34 two reported significant reductions.19,24 The pooled odds ratio for the three randomised trials entered into a meta-analysis19,24,34was 0.55 (0.35 to 0.88), suggesting that home visiting was successful in reducing admissions for at risk older people (fig 5).

Figure 5.

Log odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for institutional care in general elderly population (test for homogeneity: Q=3.19, df=3, P=0.36) and frail elderly population (Q=2.64, df=2, P=0.27)

Meta-regressions

Our meta-regressions showed that none of our three predictors (population type, duration of intervention, and age group) had any effect on mortality or admissions to institutional care. The analysis of hospital admissions was complicated by the small number of studies, the lack of any studies on elderly people who were considered to be at risk, and the fact that one study31 was of poor methodological quality.

Discussion

Our review of the results of home visiting programmes shows that home visiting is effective in reducing mortality and admission to long term institutional care among members of the general elderly population and frail older people who are at risk of adverse outcomes. We did not find any significant reduction in admissions to hospital. The observed heterogeneity in relation to this outcome (see fig 2) seems to be accounted for largely by the study of Balaban et al,31 which was of poor methodological quality. Balaban et al conceded themselves that they had failed to control successfully for differences in health status between intervention and control participants at entry into the trial, resulting in a control group with better health than the intervention group. The lack of any significant effect in reducing admission to hospital may also have been the result of two opposing effects: on the one hand home visiting may have resulted in increased admissions of older people whose need for hospital care might otherwise have been neglected; on the other hand, some admissions might have been averted through home visits.

Impact on health and functional status

The absence of evidence of improved health and functional status requires explanation. Undoubtedly one reason for the failure to find any significant differences between intervention and control groups was that those in poorest health had died, so that this outcome could be measured only on a subset of the original sample—namely, those who had survived. Another possible explanation is that where self rated measures have been used, the presence of the home visitor may have encouraged older people to express their problems more easily, thereby obscuring differences between intervention and control group. The tools used may not have been sensitive enough to detect modest improvements in health or functional ability.27 Also, chronic and relatively intractable health and functional problems may require a greater, or different type of, input than that provided by the home visitors in the studies we reviewed.17

Characteristics of home visiting programmes

Why some of the programmes were more successful than others in reducing mortality is puzzling, given that this was not the primary goal of any study. The three studies of members of the general elderly population that reported significant reductions in mortality15–17 did not share any characteristics that differentiate them from the other studies in this group (see table 3). One feature is the breadth of response of the health visitor. In the inner city group in the study by Vetter et al17 and in the study by Hendriksen et al15 the health visitor referred to a wide range of outside agencies, whereas in the rural group in the study by Vetter et al and in other studies that showed no reduction in mortality there was a narrower focus on referral to a general practitioner.

It is difficult to know which components of the home visitors' interventions made a difference to any of the outcomes assessed. As all the programmes were multifaceted, the independent effect of a particular component of care was difficult to assess. Moreover, in the papers we reviewed, descriptions of what the home visitor did were brief, giving little feel for the processes involved. Future studies would benefit from a greater focus on the process of delivering care and on attempting to identify which components of the intervention work.

Our finding from the meta-regression that the effect of home visiting did not depend on whether the intervention was targeted at elderly people who are at risk or whether it was delivered more widely is interesting. It suggests that the exclusion of people who are not at increased risk from such interventions is not, on the present evidence, justified. Similarly, the finding that the effect of home visiting did not depend on the age of participants suggests that the exclusion of “younger” elderly people from such interventions is also unjustified. However, more work is required to test our findings here, as the evidence from individual studies we reviewed suggests that those in poorer health benefit more from the intervention27 and that interventions targeted more intensively on those identified as having problems are more effective.16 A recent study by Stuck et al, published after the end of our literature search, found that disability was reduced in older people at low risk at baseline but not in those at high risk.38 More work is clearly required to assess which populations benefit most from home visiting. Further work could also assess the optimal intensity of home visiting. As several studies did not report the intensity of visits, the importance of this factor was difficult to gauge.

Comparisons with other studies

Our findings are in marked contrast to those of van Haastregt et al,22 who, in the absence of a meta-analysis of the results of the trials they reviewed, failed to find evidence that home visiting resulted in any consistent positive outcomes. Though only four out of the 15 studies we reviewed found a significant effect on mortality, we have shown significant positive effects by combining data. Similarly, only three of the 14 studies showed a significant reduction in admissions to institutional care.19,24,28 Yet by pooling data from all the studies that assessed this outcome, we showed significant positive effects. It seems that the decision of van Haastregt et al not to perform a meta-analysis might have led them to underestimate the effectiveness of preventive home visits to older people.

Clearly, all meta-analyses contain heterogeneity. However, unlike van Haagstregt et al, we did not consider that differences between the interventions meant their results could not be combined. By grouping our trials into two more homogeneous types of intervention (those aimed at the general elderly population and those aimed at frail older people who were at risk of adverse outcomes), we considered that meta-analysis was justified. While the number of trials in each meta-analysis was small, the results are encouraging, confirming the earlier promising findings of Stuck et al.13 On the basis of our own results, we cannot endorse the conclusion of van Haastregt et al that the evidence of effectiveness is so modest and inconsistent that home visits to older people should be discontinued. On the contrary, we believe that further trials to assess the effectiveness of home based support to older people may confirm our positive findings, and we look forward to the results of ongoing trials.43

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS Executive.

Footnotes

Editorial by Clark

Funding: NHS research and development health technology assessment programme.

Competing interests: JR has been reimbursed by the Community Practitioners and Health Visitors Association, the Royal College of Nursing, and the Royal College of Practitioners for attending conferences.

References

- 1.Sutherland Sir S. With respect to old age: long term care—rights and responsibilities. A report by the Royal Commission on long term care. London: Stationery Office; 1999. . (Cm 4192-I.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williamson J. Screening, surveillance and case finding. In: Arie T, editor. Health care of the elderly. London: Croom Helm; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Currie G, MacNeill RM, Walker JG, Barnie E, Mudie EW. Medical and social screening of patients aged 70-72 by an urban general practice health team. BMJ. 1974;ii:108–111. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5910.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber JH, Wallis JA. Assessment of the elderly in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1976;26:106–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsdell JW, Swart JA, Jackson JE, Renvall M. The yield of a home visit in the assessment of geriatric patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tulloch AJ, Moore V. A randomized controlled trial of geriatric screening and surveillance in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1979;29:733–742. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorensen KH, Sivertsen J. Follow-up three years after intervention to relieve unmet medical and social needs of old people. Compr Gerontol [B] 1988;2:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health Visitors' Association and the British Geriatrics Society. Health visiting for the health of the aged. London: Health Visitors' Association; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brocklehurst JC. Health visiting and the elderly—a geriatrician's view. Health Visit. 1982;55:356–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips S. Health visitors and the priority of the elderly. Health Visit. 1988;61:341–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coupland R. Effective health visiting for elderly people. Health Visit. 1986;59:299–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruse J, Ebrahim S. Screening the elderly: a neglected aspect of health visiting. Health Visit. 1986;59:308–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, Adamis J, Rubenstein LZ. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet. 1993;342:1032–1036. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92884-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carpenter GI, Demopoulos GR. Screening the elderly in the community: controlled trial of dependency surveillance using a questionnaire administered by volunteers. BMJ. 1990;300:1253–1256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6734.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendriksen C, Lund E, Stromgord E. Consequences of assessment and intervention among elderly people: a three year randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1984;289:1522–1524. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6457.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pathy MSJ, Bayer A, Harding K, Dibble A. Randomised trial of case finding and surveillance of elderly people at home. Lancet. 1992;340:890–893. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93294-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vetter NJ, Jones DA, Victor CR. Effect of health visitors working with elderly patients in general practice: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1984;288:369–372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6414.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vetter NJ, Lewis PA, Ford D. Can health visitors prevent fractures in elderly people? BMJ. 1992;304:888–890. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6831.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen FR, Spedtsberg K, Schroll M. Geriatric follow-up by home visits after discharge from hospital: a randomized controlled trial. Age Ageing. 1992;21:445–450. doi: 10.1093/ageing/21.6.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melin AL, Bygren LO. Efficacy of the rehabilitation of elderly primary health care patients after short-stay hospital treatment. Med Care. 1992;30:1004–1015. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199211000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin CD, Sizemore MT, Loftis PA, Adams-Huet B, Anderson RJ. The effect of geriatric evaluation and management on Medicare reimbursement in a large public hospital: a randomised clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:989–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb04474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Haastregt JCM, Diederiks JPM, van Rossum E, de Witte LP, Crebolder HFJM. Effects of preventive home visits to elderly people living in the community: a systematic review. BMJ. 2000;320:754–758. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fabacher D, Josephson K, Pietruszka F, Linderborn K, Morley J E, Rubenstein, et al. An in-home preventive assessment programme for independent older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:630–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall N, De Beck P, Johnson D, Mackinnon K, Gutman G, Glick N. Randomized trial of a health promotion program for frail elders. Can J Aging. 1992;11:72–91. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luker K. Evaluating health visiting practice: an experimental study to evaluate the effects of focused health visitor intervention on elderly women living alone at home. London: Royal College of Nursing; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McEwan RT, Davidson N, Forster DP, Pearson P, Stirling E. Screening elderly people in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40:94–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Rossum E, Frederiks CMA, Philipsen H, Portengen K, Wiskerke J, Knipschild P. Effects of preventive home visits to elderly people. BMJ. 1993;307:27–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6895.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stuck AE, Aronow HU, Steiner A, Alessi CA, Bula CJ, Gold MN, et al. A trial of annual in-home comprehensive geriatric assessments for elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1184–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvoy G, Claus EB, Garrett P, Gottschalk M, et al. A multifactoral intervention to reduce risks of falls among elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:821–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner EH, LaCroix AZ, Grothaus L, Leveille SG, Hecht JA, Arta K, et al. Preventing disability and falls in older adults: a population-based randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1800–1806. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balaban DJ, Goldfarb NI, Perkel RL, Carlson BL. Follow-up study of an urban family medicine home visit program. J Fam Pract. 1988;26:307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oktay JS, Volland PJ. Post-hospital support program for the frail elderly and their caregivers: a quasi-experimental evaluation. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:39–46. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams IE, Greenwell J, Groom LM. The care of people over 75 years old after discharge from hospital: an evaluation of timetabled visiting by health visitor assistants. J Public Health Med. 1992;14:138–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunn RB, Lewis PA, Vetter NJ, Guy PM, Hardman CS, Jones RW. Health visitor intervention to reduce days of unplanned hospital re-admission in patients recently discharged from geriatric wards: the results of a randomised controlled study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1994;18:15–23. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Miller LL, Harvath TA, Greenlick MR, Van Buren L, et al. The PREP system on nursing interventions: a pilot test with families caring for older members. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18:3–16. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Townsend J, Piper M, Frank AO, Dyer S, North WR, Meade TW. Reduction in hospital readmission stay of elderly patients by a community based hospital discharge scheme: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1988;297:544–547. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6647.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmer JG, Groth-Juncker A, McKusker J. A randomized controlled study of a home health care team. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:134–137. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stuck AE, Minder CE, Peter-Wuest I, Gillmann G, Egli C, Kesselring A, et al. A randomized trial of in-home visits for disability prevention in community-dwelling older people at low and at high risk for nursing home admissions. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:977–986. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.7.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reisch JS, Tyson JE, Mize SG. Aid to the evaluation of therapeutic studies. Pediatrics. 1989;84:815–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedges LV. Estimation of effect size from a series of independent experiments. Psychol Bull. 1982;92:490–499. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petitti DB. Meta-analysis, decision analysis, and cost-effectiveness analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper H, Hedges LV. A handbook of research synthesis. New York: Russell-Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fletcher A. Effects of home visiting to elderly people living in the community: systematic review [rapid response to Jolanda CM van Haastregt et al. Effects of home visiting to elderly people living in the community: systematic review]. BMJ 2000. bmj.com/cgi/eletters/320/7237/754#EL4 (accessed 9 Oct 2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]