Abstract

Wilson's disease (WD) is a neurodegenerative disorder due to copper metabolism. Schizophrenia-like psychosis and delusional disorder are rare forms of psychiatric manifestations of WD. The lack of recognition of these signs and symptoms as being attributable to WD often leads to delays in diagnosis and management. Knowledge about relationship of the psychiatric manifestations to WD can help with the administration of adequate management aimed at both the psychiatric issues and underlying WD. The objectives of this article are to review case reports whose subject is the incorrect diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like syndrome in patients with WD and to detail one case of this mismanagement of the disease. A 35-year-old unmarried Iranian woman presented to the consulting psychiatrist in the emergency room after a suicide attempt due to commanding auditory hallucination. She had previous eleven admissions in psychiatric hospital with major depressive episode with psychotic features, schizoaffective disorders, and then schizophrenia diagnosis. Nineteen years after her first symptoms, it was discovered that the patient was suffering from WD. We searched Google Scholar, Ovid, PsycINFO, CINHAL, and PubMed databases from 1985 to 2015. Finally, 14 researches were entered into the study. Psychiatric manifestations may precede the diagnosis of WD and other symptoms related to neurological or hepatic impairment. Early detection of WD is important to prevent catastrophic outcome. Young patients presenting with psychiatric presentations along with abnormal movement disorder, seizure, or conversion-like symptoms should be evaluate for WD even if signs and symptoms are typically suggestive of schizophrenia or manic episode. An interdisciplinary approach with good collaboration of psychiatrists and neurologists is crucial for WD because early diagnosis and management without delay is an important for good prognosis.

Key words: Neuropsychiatric, psychosis, psychosomatic, schizophrenia, Wilson disease

INTRODUCTION

Wilson's disease (WD) is a neurodegenerative disorder due to copper metabolism.[1] Dr. Wilson first described WD in 12 patients in 1912.[2] The disease is described by excessive accumulation of copper in different tissues and primarily affects the liver and the brain.[3] The lifetime prevalence is at around 1/30,000; however, a recent research of frequency with which the abnormal gene related to WD appears points to a possible higher prevalence of 1/7026.[3] Clinically, WD generally appears between the ages of 10 and 20 years. The first presentations of the WD are hepatic (45% of the cases), neurological (35%), or psychiatric (10%).[4] WD is often accompanied by psychiatric manifestations, which may precede signs and symptoms indicating neurological deficit. More than 50% of patients with WD exhibit psychiatric disorders and a large proportion of patients undergo psychiatric management.[1,5]

The most common psychiatric presentations of WD are mood disorders, disinhibition, behavioral disorders, personality disorders, and cognitive impairment.[6] The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with WD varies wildly (major depressive disorder, 4%–47%; psychosis, 1.4%–11.5%). Certain ATP7B gene mutations may correlate with specific personality traits that reflect these disorders.[7] Schizophrenia-like psychosis and delusional disorder are rare forms of psychiatric manifestations of WD, and only a few cases have been reported in the literature.[6] Furthermore, many persons with WD will have psychiatric manifestations develop after diagnosis and initiation of management or after relapses.[8]

When psychiatric manifestations preceded hepatic or neurological involvement, the average time between the psychiatric presentations and the diagnosis of WD was 864.3 days.[7] Knowledge of the psychiatric aspects of WD is essential for psychiatrists and other medical clinicians and allied health professionals practicing in the general medical hospital. The objectives of this article are to review case reports whose subject is the incorrect diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like syndrome in patients with WD and to detail one case of this mismanagement of the disease.

CASE REPORT

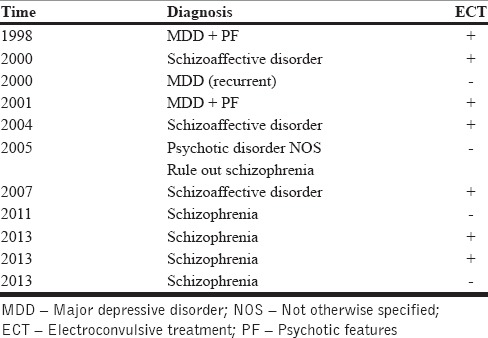

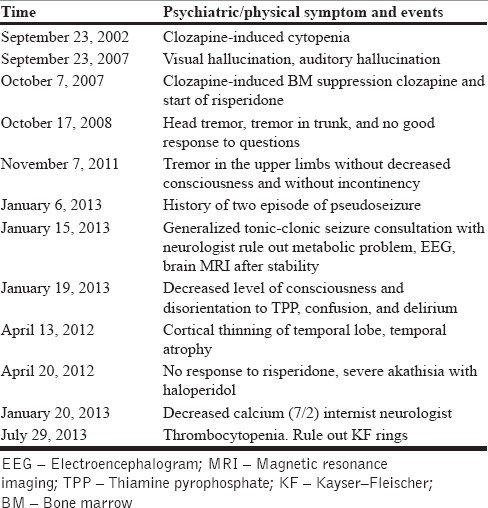

A 35-year-old Iranian woman from a rural background and lower socioeconomic class (education up to the 6th standard) presented to the consulting psychiatrist in an academic general hospital. She was eventually admitted to the Intensive Care Unit after a suicide attempt, in which she ingested alkali-based detergent. The woman was intubated and placed on a ventilator for aspiration pneumonia and bacterial pneumonitis that occurred after the initial chemical pneumonitis. Communication was possible by writing. All four of her limbs exhibited involuntary jerking movements, primarily on the left side. She also complained of infrequently hearing voices that were commanding and persecutory in nature. In this admission, the laboratory results for liver function testing were as follows: total bilirubin = 2.4 mg/dl, direct bilirubin = 1.0 mg/dl, aspartate aminotransferase = 11 IU/L, and alanine aminotransferase = 31 U/L. Thrombocytopenia was present (plt: 44,000, 39,000, 12,000/mm3). Serum ceruloplasmin was markedly reduced at 0.164 g/L (reference values: 0.204–0.407 g/L); copper concentrations were significantly decreased at 50 μg/dl (reference range, 70–153 μg/dl), as 24-h urinary copper was high at 240 μg/24 h (volume: 1690 cc) (reference value up to 80 μg/24 h; WD >100 μg/24 h). Ophthalmological examination demonstrated the initial development of Kayser–Fleischer (KF) rings in the clear anterior segment of the cornea. WD was diagnosed after laboratory tests; furthermore, the patient received a diagnosis of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition Axis I psychotic disorder due to WD, with delusions. Penicillamine was administered by her main physician, a gastrointestinal specialist. Unfortunately, the patient died after 11 days due to chemical burning and its complications caused by her ingestion of detergent. Review of her history showed during her adolescence, she experienced seizures (at the age of 12 years) and received treatment with sodium valproate; she did not have a developmental retardation in comparison with others her age until the age of 9 years old. At that time, she had some behavioral problems in school and was eventually expelled from school at the age of 12 years. At the age of 17 years, the first set of severe psychiatric signs and symptoms surfaces, including negativism, commanding auditory hallucinations, persecutory delusions, and impaired verbal communication. Antipsychotic medications she was prescribed included haloperidol 20 mg/day and nortriptyline 100 mg/day. No significant improvement in her condition occurred; because of this, other antipsychotic therapies (including clozapine) were used over a period of almost 19 years; she was admitted to eleven different psychiatric wards during this time, with different diagnoses emerging [Table 1]. In addition, she experienced multiple side effects with different antipsychotics at different times – severe akathisia with haloperidol, tremor with risperidone, and cytopenia due to myelosuppression with clozapine [Table 2].

Table 1.

Different psychiatric diagnosis for this case (1998–2013)

Table 2.

Significant psychiatric/physical symptom and significant events

In 2013, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed atrophic changes in the temporal lobe. Since no appropriate improvement was seen with medications, and the patient's suicidal ideations continued, a course of electroconvulsive treatments was planned and administered during her first, second, fourth, fifth, seventh, ninth, and also tenth admissions to the psychiatric ward. During the patient's last admission to the psychiatric ward, she experienced tremor in her extremities and hands, right-sided pitting edema in her right limb, falling, and swelling and ecchymosis in her right knee. Nurses said that she had hysterical movements such as pseudoseizure and voluntary falling in the ward (the falling, in retrospect, was probably involuntary rather than voluntary). Numbers from liver function testing were as follows: aspartate aminotransferase = 14 IU/L (reference range, 8–37 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase = 8U/L (reference range, 8–37 IU/L). Other laboratory values included the following: calcium, 8.1 mg/dl (reference range, 8.6–10.3 mg/dl); phosphor, 4.67 mg/dl (reference range, 2.6–4.5 mg/dl). Thrombocytopenia was also present (plt: 40,000/mm3). A hematologist was consulted due to the presence of thrombocytopenia and advised further consultations with a hepatologist. The patient was referred to the general hospital for monitoring of her medical problem. She arrived at the emergency department 9 months later, with the suicide attempt explained at the beginning of this case study.

DISCUSSION

The presented case of WD has several specific manifestations that distinguish it from most other patients with WD. Although treated with antispsychotics, she had periods of remission and relapse, and never was symptom-free. Similar cases have been described elsewhere, but to the best of our knowledge, this case represents the longest period over which a psychotic disorder was diagnosed and treated without uncovering the underlying cause of the symptoms (19 years). Such a delay is particularly tragic as favorable outcomes depend on early discovery;[9] the patient died after her suicidal attempt that was spurred by auditory hallucinations. She developed tremors after initiation of injectable haloperidol and severe akathisia with risperidone. She had abnormal involuntary choreoathetoid limb movements and jerky movements that were involuntary and misinterpreted as side effects of antipsychotics but that actually represented the clinical manifestation of WD.

Traditional or atypical antipsychotics have been used with the overall warning that these patients are very sensitive to antipsychotics and prone to develop multiple extrapyramidal side effects.[10] Unfortunately, the neurologist consulted during the first admission adjusted the dose of her anticonvulsant medication (against generally accepted recommendations) due to her previous seizures, as he was unaware of the underlying cause of her condition.

Although psychiatric features are not rare in WD, their association with seizures is rare.[11] Our patient with predominantly temporal atrophy had epileptic seizures and then psychosis. Another case study reported on three patients with psychiatric symptoms who had predominantly white matter lesions in the frontal lobe. The early manifestations were psychiatric symptoms and epileptic seizures with or without secondary generalization. The present observation found that early onset of psychiatric presentation and seizures is common in WD with white matter lesions in frontal lobes.[11] A study from India that evaluated 350 patients with WD reported psychosis (of the schizophreniform type) in three cases only.[12] Other literature have also reported a low prevalence of psychosis–1 out of 30 cases,[10] 8 out of 70 cases,[11] 3 cases of organic delusional disorder out of 45 patients,[13] 2 out of 195 cases,[14] and 2 out of 42 cases.[8] The prevalence of psychosis in persons with WD varies from 0% to 11.5%. Since the early presentations of WD, few case reports have documented the occurrence of psychosis in patients with WD.[15,16,17,18] However, over the last two decades, case reports/series have proliferated describing psychosis in patients with WD.[10,11,13,15,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]

In our case, WD was determined by the following positive findings: (I) Presence of KF ring (II) high urinary copper level, and (III) low serum ceruloplasmin level. The gold standard for WD diagnosis is by liver biopsy with quantitative copper evaluation (copper values >3.1 μmol/g of dry liver weight).[31] Liver biopsy was not performed for several reasons: the invasiveness of the procedure, the inability to estimate copper in dry liver tissue with the equipment available at our center, and the fact that approval for biopsy was not given by the patient's brother (her caretaker). The combination of neurological symptoms, KF rings, and a low ceruloplasmin level is considered sufficient and appropriate for the diagnosis of WD.[32]

Copper is considered essential for brain function[33,34] and its importance in various psychiatric illnesses has been explored. Initial researches showed increased levels of copper in the hair and plasma of patients with schizophrenia compared to control groups.[35,36] Abnormalities of smooth pursuit eye movements, long time considered a mark in schizophrenic patients, have been described in WD.[37] Some researches found that an increased copper level was related to the use of psychotropic drugs, such as long-acting antipsychotic use in schizophrenic patients[38] or anticonvulsant treatment in women was epileptic.[39] The copper hypothesis of schizophrenic patients was abandoned in 1980 without ever being totally refuted.[40] Wolf found that patients with schizophrenia had serum copper levels that were increased by 24% and serum ceruloplasmin levels elevated by 20% compared to control group.[41] It was postulated that an excess of copper may affect dopamine activity through multiple copper-dependent enzymes.[41,42] Another recent literature suggested that dopamine gene polymorphism may be playing a significant role in the neuropsychiatric manifestations in WD.[43]

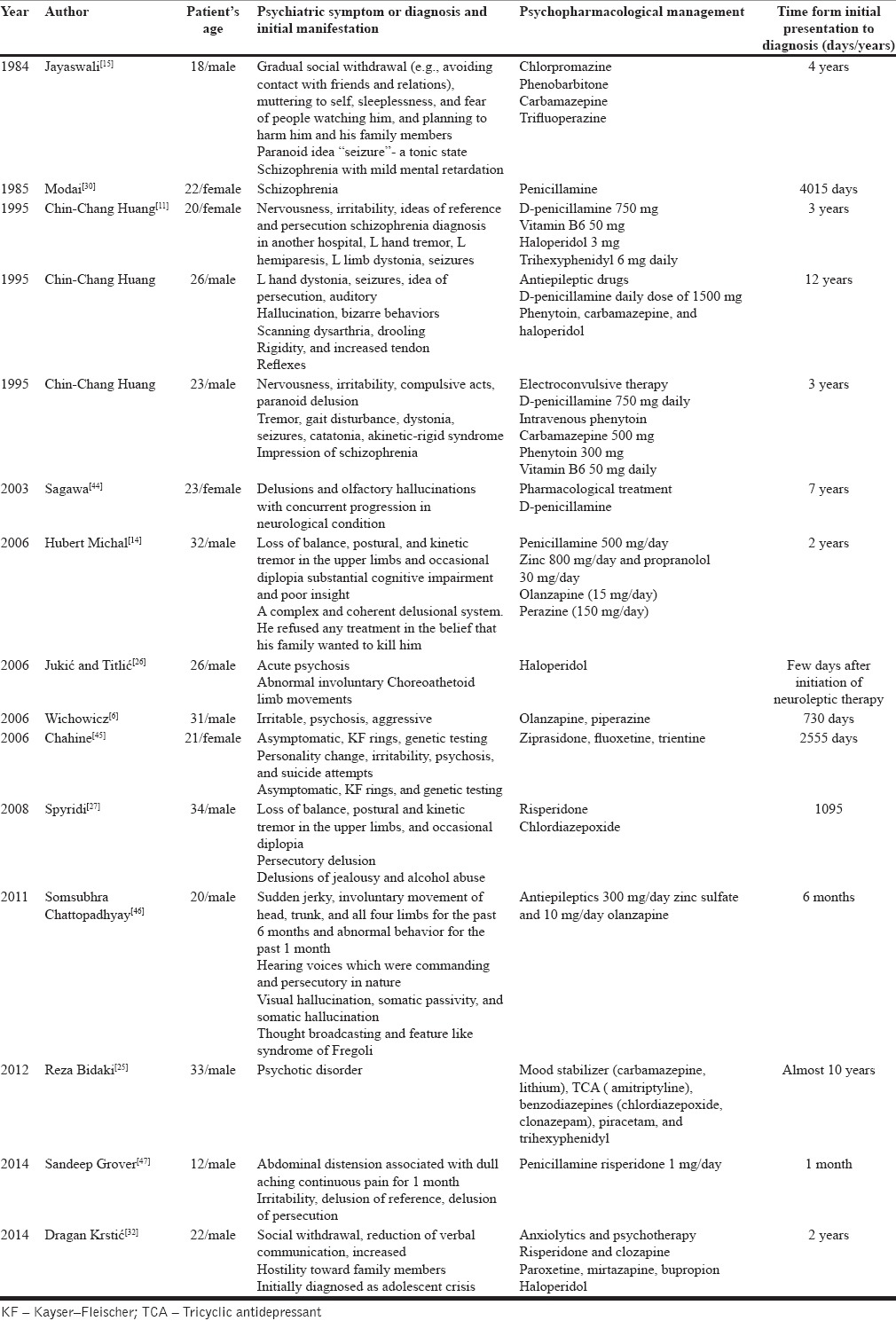

Co-occurrence of schizophrenic-like symptoms with WD is rare, and there are just a few case reports of WD with this type of psychiatric presentation.[11] Table 3 provides an overview of the case reports about this issue.[10,11,13,15,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]

Table 3.

Case reports of WD with psychosis in psychiatric presentation

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with psychiatric symptoms with clues such as history of jaundice, family history of neuropsychiatric disorders, and sensitivity to typical/atypical antipsychotics should be evaluated for WD to avoid delay in diagnosis and associated morbidity. Although such patients are more commonly seen in neurological and hepatological clinics, psychiatrists must keep in mind a high level of suspicion, and consider WD in instances where the first presentation of illness is psychiatric in nature.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dening TR, Berrios GE. Wilson's disease. Psychiatric symptoms in 195 cases. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1126–34. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810120068011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson SA. Progressive lenticular degeneration: A familial nervous disease associated with cirrhosis of liver. Brain. 1912;34:295–509. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffey AJ, Durkie M, Hague S, McLay K, Emmerson J, Lo C, et al. A genetic study of Wilson's disease in the United Kingdom. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 5):1476–87. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benhamla T, Tirouche YD, Abaoub-Germain A, Theodore F. The onset of psychiatric disorders and Wilson's disease. Encephale. 2007;33:924–32. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akil M, Schwartz JA, Dutchak D, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V, Brewer GJ. The psychiatric presentations of Wilson's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991;3:377–82. doi: 10.1176/jnp.3.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wichowicz HM, Cubala WJ, Slawek J. Wilson's disease associated with delusional disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:758–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimbrean PC, Schilsky ML. Psychiatric aspects of Wilson disease: A review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prashanth LK, Taly AB, Sinha S, Arunodaya GR, Swamy HS. Wilson's disease: Diagnostic errors and clinical implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:907–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.026310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akil M, Brewer GJ. Psychiatric and behavioral abnormalities in Wilson's disease. Adv Neurol. 1995;65:171–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar R, Datta S, Jayaseelan L, Gnanmuthu C, Kuruvilla K. The psychiatric aspects of Wilson's disease-a study from a neurology unit. Indian J Psychiatry. 1996;38:208–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang CC, Chu NS. Psychosis and epileptic seizures in Wilson's disease with predominantly white matter lesions in the frontal lobe. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 1995;1:53–8. doi: 10.1016/1353-8020(95)00013-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srinivas K, Sinha S, Taly AB, Prashanth LK, Arunodaya GR, Janardhana Reddy YC, et al. Dominant psychiatric manifestations in Wilson's disease: A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge! J Neurol Sci. 2008;266:104–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oder W, Grimm G, Kollegger H, Ferenci P, Schneider B, Deecke L. Neurological and neuropsychiatric spectrum of Wilson's disease: A prospective study of 45 cases. J Neurol. 1991;238:281–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00319740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brewer GJ. Zinc acetate for the treatment of Wilson's disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2001;2:1473–7. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2.9.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayaswal SK, Lal P, Nepal MK, Wig NN. Wilson's disease presenting with schizophrenia like psychosis: A case report. Indian J Psychiatry. 1984;26:245–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beard AW. The association of hepatolenticular degeneration with schizophrenia. A review of the literature and case report. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1959;34:411–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1959.tb07531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierson H. Two types of Wilson's disease; hepato-lenticular degeneration; case reports. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1952;11:19–33. doi: 10.1097/00005072-195201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gysin WM, Cooke ET. Unusual mental symptoms in a case of hepatolenticular degeneration. Dis Nerv Syst. 1950;11:305–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javed MA, Zia S, Ashraf S, Mehmood S. Neurological and neuropsychiatric spectrum of Wilson's disease in local population. Biomedica. 2008;24:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amin R, Hasan R, Saha A, Hossain AR, Kahhar MA. Wilson's disease in a young girl with abnormal behavior. J Bangladesh Coll Phys Surg. 2011;29:170–3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shanmugiah A, Sinha S, Taly AB, Prashanth LK, Tomar M, Arunodaya GR, et al. Psychiatric manifestations in Wilson's disease: A cross-sectional analysis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;20:81–5. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2008.20.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merle U, Schaefer M, Ferenci P, Stremmel W. Clinical presentation, diagnosis and long-term outcome of Wilson's disease: A cohort study. Gut. 2007;56:115–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.087262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stremmel W, Meyerrose KW, Niederau C, Hefter H, Kreuzpaintner G, Strohmeyer G. Wilson disease: Clinical presentation, treatment, and survival. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:720–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-9-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saint-Laurent M. Schizophrenia and Wilson's disease. Can J Psychiatry. 1992;37:358–60. doi: 10.1177/070674379203700511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bidaki R, Zarei M, Mirhosseini SM, Moghadami S, Hejrati M, Kohnavard M, et al. Mismanagement of Wilson's disease as psychotic disorder. Adv Biomed Res. 2012;1:61. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.100182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jukic I, Titlic M, Tonkic A, Dodig G, Rogosic V. Psychosis and Wilson's disease: A case report. Psychiatr Danub. 2006;18:105–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spyridi S, Diakogiannis I, Michaelides M, Sokolaki S, Iacovides A, Kaprinis G. Delusional disorder and alcohol abuse in a patient with Wilson's disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:585–6. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorbello O, Riccio D, Sini M, Carta M, Demelia L. Resolved psychosis after liver transplantation in a patient with Wilson's disease. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2011;7:182–4. doi: 10.2174/1745017901107010182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald LV, Lake CR. Psychosis in an adolescent patient with Wilson's disease: Effects of chelation therapy. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:202–4. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199503000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Modai I, Karp L, Liberman UA, Munitz H. Penicillamine therapy for schizophreniform psychosis in Wilson's disease. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173:698–701. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198511000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brewer GJ. Wilson's disease. In: Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Longo DL, Braunwald E, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 2313–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krstic D, Antonijevic J, Špiric Ž. Atypical case of Wilson's disease with psychotic onset, low 24 hour urine copper and the absence of Kayser-Fleischer rings. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2014;71:1155–8. doi: 10.2298/vsp130529049k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson WT. Copper and brain function. US: Taylor and Francis; 2005. pp. 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madsen E, Gitlin JD. Copper and iron disorders of the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:317–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yanik M, Kocyigit A, Tutkun H, Vural H, Herken H. Plasma manganese, selenium, zinc, copper, and iron concentrations in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2004;98:109–17. doi: 10.1385/BTER:98:2:109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahman A, Azad MA, Hossain I, Qusar MM, Bari W, Begum F, et al. Zinc, manganese, calcium, copper, and cadmium level in scalp hair samples of schizophrenic patients. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2009;127:102–8. doi: 10.1007/s12011-008-8230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lesniak M, Czlonkowska A, Seniów J. Abnormal antisaccades and smooth pursuit eye movements in patients with Wilson's disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:2067–73. doi: 10.1002/mds.22276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herrán A, García-Unzueta MT, Fernández-González MD, Vázquez-Barquero JL, Alvarez C, Amado JA. Higher levels of serum copper in schizophrenic patients treated with depot neuroleptics. Psychiatry Res. 2000;94:51–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki T, Koizumi J, Moroji T, Shiraishi H, Hori T, Baba A, et al. Effects of long-term anticonvulsant therapy on copper, zinc, and magnesium in hair and serum of epileptics. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;31:571–81. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90243-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowman MB, Lewis MS. The copper hypothesis of schizophrenia: A review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1982;6:321–8. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(82)90044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeon B, Kim JM, Jeong JM, Kim KM, Chang YS, Lee DS, et al. Dopamine transporter imaging with [123I]-beta-CIT demonstrates presynaptic nigrostriatal dopaminergic damage in Wilson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:60–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf TL, Kotun J, Meador-Woodruff JH. Plasma copper, iron, ceruloplasmin and ferroxidase activity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;86:167–71. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sathyanarayana Rao TS, Zecca L, Rao KJ. Tracemetals, neuromelanin and neurodegeneration: An interesting area for research. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:154–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sagawa M, Takao M, Nogawa S, Mizuno M, Murata M, Amano T, et al. Wilson's disease associated with olfactory paranoid syndrome and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. No To Shinkei. 2003;55:899–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chahine LM, Chemali ZN. The bane of a silent illness: When Wilson's disease takes its course. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:333–8. doi: 10.2190/1A0B-2M98-0VVE-485R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chattopadhyay S, Saha I, Bhattacharyya K, Mondal DK. Wilson's disease can present as paranoid schizophrenia and mania: Two case reports. ASEAN J Psychiatry. 2011;12:190–2. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grover S, Sarkar S, Jhanda S, Chawla Y. Psychosis in an adolescent with Wilson's disease: A case report and review of the literature. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56:395–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.146530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polymorphism of psychiatric manifestations in Wilson s disease- Romanian. Journal of Psychiatry Romanian Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;12:20–1. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Medici V, Mirante VG, Fassati LR, Pompili M, Forti D, Del Gaudio M, et al. Liver transplantation for Wilson's disease: The burden of neurological and psychiatric disorders. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1056–63. doi: 10.1002/lt.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Svetel M, Pekmezovic T, Tomic A, Kresojevic N, Potrebic A, Ješic R, et al. Quality of life in patients with treated and clinically stable Wilson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:1503–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.23608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]