Abstract

Degeneration of the intervertebral discs is a progressive cascade of cellular, compositional and structural changes that is frequently associated with low back pain. As the first signs of disc degeneration typically arise in the disc's central nucleus pulposus (NP), augmentation of the NP via hydrogel injection represents a promising strategy to treat early to mid-stage degeneration. The purpose of this study was to establish the translational feasibility of a triple interpenetrating network hydrogel composed of dextran, chitosan, and teleostean (DCT) for augmentation of the degenerative NP in a preclinical goat model. Ex vivo injection of the DCT hydrogel into degenerated goat lumbar motion segments restored range of motion and neutral zone modulus towards physiologic values. To facilitate non-invasive assessment of hydrogel delivery and distribution, zirconia nanoparticles were added to the hydrogel to make the hydrogel radiopaque. Importantly, the addition of zirconia did not negatively impact viability or matrix producing capacity of goat mesenchymal stem cells or NP cells seeded within the hydrogel in vitro. In vivo studies demonstrated that the radiopaque DCT hydrogel was successfully delivered to degenerated goat lumbar intervertebral discs, where it distributed throughout both the NP and annulus fibrosus, and that the hydrogel remained contained within the disc space for two weeks without evidence of extrusion. These results demonstrate the translational potential of this hydrogel for functional regeneration of degenerate intervertebral discs.

Keywords: Nucleus pulposus, intervertebral disc degeneration, hydrogel, preclinical animal model, goat, imaging

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The intervertebral discs are composite structures composed of a central nucleus pulposus (NP), an outer annulus fibrosus (AF), and two hyaline cartilage end plates that interface with the vertebral bodies. The NP is composed primarily of type II collagen and proteoglycans and in its healthy state is highly hydrated [1,2]. The AF is composed primarily of type I and II collagen fibers oriented at alternating oblique angles to the long axis of the spine, arranged in concentric lamellae [3]. The function of the disc is primarily mechanical – when the spine is subjected to compressive loading, hydrostatic pressure develops within the NP and places the AF in tension, allowing the discs to bear load, while permitting complex spinal motion [4,5].

Degeneration of the intervertebral discs is a progressive cascade of cellular, compositional and structural changes that is closely linked with aging [2,6]. The earliest degenerative changes typically occur in the NP, and are characterized by a loss of proteoglycans, which compromises the ability of the NP to swell and the disc to bear load [7,8]. This results in a loss of disc height, and progressive structural and mechanical failure of the intervertebral joint [9]. Disc degeneration is frequently associated with low back pain, [10] which is the second most common cause of adult disability in the United States, with a prevalence greater than heart conditions, stroke and cancer combined [10,11].

For patients with low back pain secondary to disc degeneration, initial clinical treatment is generally conservative [8]. If conservative treatment fails, patients can be treated surgically to immobilize the degenerated motion segment via a fusion procedure or to replace the degenerated disc with a mechanical arthroplasty device [12,13]. These current surgical treatment options are limited in that they do not address the underlying cause of degeneration, do not restore native disc structure or function and are typically indicated for end-stage degeneration only. In the United States, there are nearly 4 million patients per year with moderate disc degeneration that are unresponsive to conservative treatment, but are not suitable candidates for fusion surgery [14]. For these reasons, there is a pressing need to develop treatment strategies for disc degeneration, particularly those targeting patients with early to mid-stage degeneration and who are unresponsive to conservative therapies.

As progressive degeneration first manifests in the NP, there has been considerable interest in developing hydrogel-base strategies that can synergize with stem cells and bioactive molecules to augment and potentially restore native NP tissue [15]. A candidate hydrogel for NP regeneration would ideally be injectable (to allow for minimally invasive delivery), would rapidly solidify (to prevent extrusion from the disc space with loading), and be able to augment the mechanical function of the degenerative motion segment. The ideal hydrogel would also be cytocompatible with native disc cells, and support delivery of stem cells to potentiate long-term native tissue regeneration.

Towards this goal, several biomaterials have been evaluated in vitro for NP regeneration, including thermoreversible hyaluronan grafted poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) hydrogels [16,17], hyaluronic acid and collagen II-based hydrogels [18–23], photocrosslinkable carboxymethylcellulose hydrogels [24,25], and in situ gelling native extracellular matrices [26], among others. Our group recently developed and characterized a triple-interpenetrating network hydrogel for NP regeneration comprised of N-carboxyethyl chitosan, oxidized dextran and teleostean (DCT), which gels in situ via Schiff base formation between the –CHO on the oxidized dextran and the –NH2 on the teleostean and chitosan [27,28]. This triple component hydrogel has improved mechanical properties and degradation profiles as compared to various dual component hydrogel combinations of chitosan, dextran and teleostean [28]. Our previous work showed that the mechanical properties of this DCT hydrogel were similar to that of native NP tissue, and that it supported the survival and differentiation of bovine mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) towards an NP cell-like phenotype in vitro [29]. We also previously demonstrated that an injectable oxidized hyaluronan and teleostean hydrogel with similar properties was capable of restoring range of motion (ROM) following ex vivo nucleotomy in an ovine disc, and is not expelled from the disc space following cyclic loading of up to 2X body weight [29,30]. As a platform for the in vivo evaluation of combined stem cell and hydrogel therapeutics for disc regeneration, our group has previously developed a large animal model of intervertebral disc degeneration where a spectrum of degeneration from mild to severe can be reproducibly achieved in goat lumbar discs 12 weeks following intradiscal injection of chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) [31]. The goat lumbar spine is a promising pre-clinical model due to the large size of the lumbar discs (∼5mm disc height), and similarities in mechanical properties and biochemical composition to human discs [32].

In this study we describe the modification of the DCT hydrogel to impart radiopacity using zirconium dioxide nanoparticles (as has been utilized in FDA approved bone cements) [33], thereby facilitating non-invasive assessment of delivery and distribution in vivo. With this modification, we show the feasibility of this material for NP regeneration in our preclinical goat model of disc degeneration by (1) illustrating the ability of the DCT gel to restore mechanical function to a degenerative disc ex vivo, (2) demonstrating the radiopaque DCT gel is capable of supporting the survival and matrix producing capacity of both NP cells and MSCs in vitro, and (3) showing delivery, retention and safety of the DCT gel in vivo in degenerative goat lumbar discs.

2. Methods

2.1 Hydrogel Fabrication and Modification to Impart Radiopacity

To fabricate the DCT hydrogel, oxidized dextran and N-carboxyethyl chitosan (Endomedix Inc, Montclaire, NJ) were synthesized as described previously [27]. Aqueous solutions of 20% teleostean (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 3% N-carboxyethyl chitosan, and 7.5% oxidized dextran were mixed at a ratio of 1:1:2. To render the hydrogel radiopaque and facilitate non-invasive assessment using x-ray fluoroscopy and microcomputed tomography (μCT), we adapted a technique previously developed for electrospun polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds where zirconia nanoparticles were mixed with aqueous PCL prior to electrospinning [34]. Zirconia nanoparticles (30 wt%, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were added to the aqueous teleostean prior to mixing of the three gel components.

2.2 Effects of Hydrogel Injection on the Mechanical Function of Degenerate Discs

Our previous work demonstrated that in vivo intradiscal injection of 1U chondroitinase-ABC (ChABC) results in reproducible and moderate degenerative changes (as characterized by MRI, disc height measurements, and histology) in the goat lumbar intervertebral disc after 12 weeks [31]. Goat lumbar spine motion segments from this previous animal cohort were utilized in this study to determine whether the DCT hydrogel could restore the mechanical function of these degenerative discs. Five vertebral body-intervertebral disc-vertebral body motion segments with posterior elements removed, and previously degenerated in vivo via 1U ChABC for 12 weeks, were thawed and injected with radiopaque DCT hydrogel using a 22G needle. The maximum possible volume of gel that could be manually introduced was injected into each motion segment. Gel-injected motion segments, as well as five healthy, control goat lumbar motion segments, were then maintained in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4°C prior to mechanical testing.

The cranial and caudal vertebral bodies of each motion segment were potted in a low-melting-temperature indium casting alloy (McMaster-Carr, Princeton, NJ), and mechanical properties were measured using an electromechanical testing system (Instron 5948, Instron, Norwood, MA), as shown in Figure 1A. Two ink marks were placed on the vertebral bodies adjacent to the disc and were tracked optically using a digital camera (A3800, Basler, Exton, PA) to determine disc axial displacement. Potted motion segments were immersed in a PBS bath at room temperature and subjected to 20 cycles of tension/compression at 0.5 Hz from -230N to +115N, followed by 1 hour of creep at -230 N (∼0.48 MPa, equivalent to 1X body weight) [32].

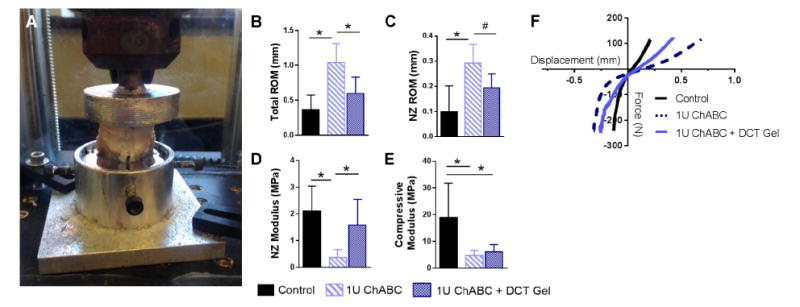

Figure 1. Ex vivo hydrogel injection restores degenerate disc mechanical properties.

(A) Goat lumbar motion segments (n=5 per group) were subjected to tension-compression testing to quantify (B) total range of motion (ROM), (C) neutral zone (NZ) ROM, (D) NZ modulus, and (E) compressive modulus. (*=p<0.05, #=p<0.1) (F) Average force-displacement curves (generated via LOWESS smoothing) for each experimental group.

The 20th cycle of tension/compression was fit to a sigmoid function using custom MATLAB software to quantify neutral zone (NZ) ROM, total ROM, NZ modulus, and compressive modulus by normalizing to disc area quantified via axial MRI images, as previously described (Supplemental Figure 1) [31,35]. The mechanical properties of the degenerate discs injected with DCT hydrogel were compared to the mechanical properties of the same degenerate discs prior to hydrogel injection, in addition to healthy, control goat lumbar intervertebral discs [31].

Following mechanical testing, motion segments were imaged en bloc at an isotropic 20.5 μm resolution to visualize the 3D distribution of the radiopaque hydrogel within the disc space (μCT 50, Scanco, Bruttisellen, Switzerland). A volume of interest constituting the entirety of the disc space was generated by manual segmentation, and the hydrogel was manually thresholded and analyzed using the Scanco μCT 50 software to obtain the hydrogel volume fraction.

To determine the effect of inclusion of the zirconia nanoparticles on the mechanical properties of the DCT hydrogel itself, hydrogel constructs (4 mm diameter, 2.25 mm thick) with and without zirconia nanoparticles (n=3 per group) were prepared as described in Section 2.1. Mechanical properties were assessed in uniaxial unconfined compression via the application of 20% strain at a strain rate of 0.05%/s, followed by a 10 minute stress-relaxation phase, as previously described [29].

2.3 Cell Survival and Extracellular Matrix Production

With approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of theUniversity of Pennsylvania, iliac crest bone marrow aspirates were collected from three largeframe male goats (Thomas D. Morris Inc, Reisterstown, MD), approximately 3 years of age.MSCs were isolated by plating the bone marrow aspirates at 37°C in basal media (high glucoseDulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone (PSF) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)). The adherent cell population was expanded to passage 4, and cells from three donors were pooled prior to hydrogel encapsulation.

NP cells were isolated post mortem from 6 thoracic discs of one adult goat. NP tissue was manually isolated from each intervertebral disc and incubated overnight at 37° C in isolation media (basal media with with 2% PSF), then digested for 1 hour in 2.5 mg/mL pronase (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), followed by 4 hours in 0.5 mg/mL collagenase (125 U/mg, Type IV, Sigma Aldrich). Following digestion, NP cells were filtered through a 70 μm strainer before being plated in basal media. NP cells were expanded to passage 4 prior to hydrogel encapsulation.

MSCs or NP cells were suspended in the 7.5% oxidized dextran such that a seeding density of 20 million cells/mL [23] of gel was achieved after mixing the three components. The gel, either with or without the addition of zirconia nanoparticles (as described in section 2.1) was extruded though a 22G needle, cast between two glass plates, and allowed to cure at 37° C for 10 minutes prior to punching 4 mm diameter, 2.25 mm thick constructs using a biopsy punch [29]. Constructs were cultured for 2 weeks in a standard 5% CO2 incubator in chemically defined media comprised of high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 1% penicillin, streptomycin, and amphotericin B (Antibiotic-Antimycotic; Gibco), 40 ng/mL dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 μg/mL ascorbate 2-phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich), 40 μg/mL L-proline (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 μg/mL sodium pyruvate (Corning Life Sciences, Corning, NY), 0.1% insulin, transferrin, and selenious acid (ITS Premix Universal Culture Supplement; Corning), 1.25 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich), 5.35 μg/mL linoleic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), and 10 ng/mL TGF-β3 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) [29].

Metabolic activity of the cell-seeded constructs after 2 weeks of culture was assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiaol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) colorimetric assay (n=3 per group). To do so, the constructs were incubated in 0.5 mg/mL MTT in DMEM for 4 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. Constructs were then weighed, minced, and the formazan product solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide. Absorbances at 540 and 595 nm were quantified using a microplate reader and normalized to construct wet weight. Additional constructs (n=3 per group) were assayed for glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content using the dimethylmethylene blue assay following overnight digestion in proteinase K at 60°C. GAG content was normalized to DNA content as quantified via the Quanti-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

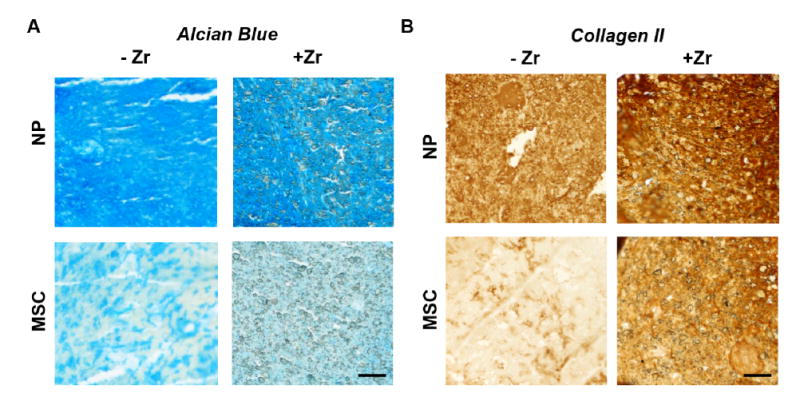

For histological analysis of matrix distribution, constructs (n=3 per group) were fixed in formalin and processed into paraffin. Sections (7μm) were stained with Alcian blue to visualize GAG distribution. Immunohistochemistry was performed for collagen II (DSHB, II-II6B3, Iowa City, Iowa). Following rehydration, the following incubations were performed: proteinase K (Dako Glostrup, Denmark) for 10 minutes at room temperature (RT), 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes at RT, blocking with horse serum for 30 minutes at RT (Vectastain ABC Universal Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and primary antibody (10 μg/mL) overnight at 4°C. Secondary detection was performed using the Vectastain Elite ABC Universal HRP Kit (PK-6200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

2.4 In Vivo Evaluation in a Large Animal Disc Degeneration Model

With IACUC approval, three adult (three years of age), male, large frame goats (Thomas D. Morris Inc, Reisterstown, MD) were utilized for in vivo evaluation of the DCT hydrogel. All animal studies were performed in compliance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Surgery was conducted to induce degeneration of the lumbar intervertebral discs via injection of 1U ChABC, as previously described [31]. Twelve weeks following ChABC injection to induce degeneration, a second surgery for intradiscal delivery of the DCT hydrogel was performed. Animals were anesthetized via intravenous injection of ketamine (11-33 mg/kg) and midazolam (0.5-1.5 mg/kg), intubated and maintained on an isoflurane-oxygen mixture for the duration of the surgical procedure. Using standard aseptic techniques, the lumbar intervertebral discs were exposed via an open, left lateral retroperitoneal, transpsoatic approach. The three hydrogel components were dissolved in sterile PBS, mixed in sterile syringes via a sterile 3-way stopcock, and immediately injected into the T12-L1 disc via a 22G needle. The hydrogel was rendered radiopaque via the inclusion of zirconia nanoparticles as described in section 2.1 to enable intraoperative visualization via fluoroscopy. The surgical incision was closed in layers and the animals hand-recovered by veterinary staff until ambulatory. Peri-operatively, animals were administered intravenous flunixin meglumine (Banamine, 1.1 mg/kg) and transdermal fentanyl (2.5 mcg/kg/hr) for analgesia. Florfenicol (40mg/kg) was administered for antimicrobial prophylaxis for 48 hours.

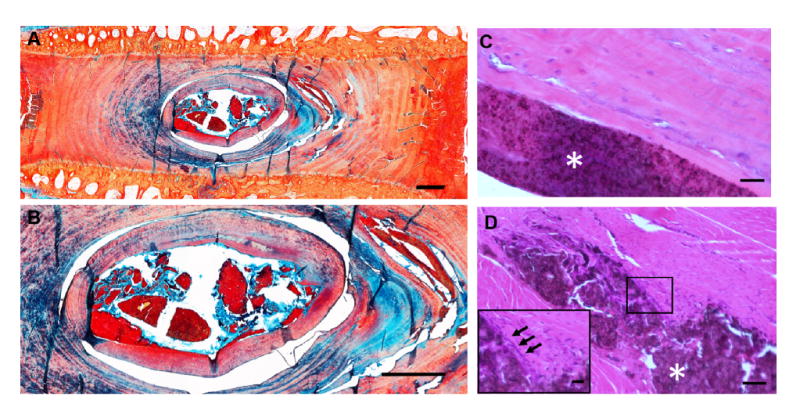

Lateral plain radiographs were obtained immediately post-operatively and at one and two weeks post-operatively to visualize hydrogel distribution within the degenerated discs and to assess disc height. To assess acute hydrogel retention and safety, two weeks following intradiscal delivery of the hydrogel, animals were euthanized by an overdose of pentobarbital solution in accordance with to American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines. The lumbar spines were harvested, and the T12-L1 motion segment was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Motion segments underwent μCT imaging as described in section 2.2 to visualize the distribution of the hydrogel in the intervertebral disc. Following μCT, samples were decalcified (Formical-2000, Decal Chemical Corporation, Tallman, USA), processed into paraffin, and sectioned at 10 μ m. Sections were stained with either Alcian blue and picrosirius red, or with hematoxylin and eosin. Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections were examined by a veterinary pathologist to identify any adverse reactions to the DCT gel within the disc space.

2.5 Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in SYSTAT 13 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). Significant differences (p<0.05) between groups for quantitative outcome measures (mechanical properties, MTT and GAG) were assessed via a one-way ANOVA with Fisher's post-hoc test. All data are represented as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1 Effects of Ex Vivo DCT Hydrogel Injection on Degenerate Disc Mechanics

Ex vivo injection volumes ranged from 0.2-0.6 mL of hydrogel. The effect of DCT hydrogel delivery on the mechanical properties of goat lumbar motion segments previously degenerated in vivo via intradiscal ChABC injection was determined via tension-compression mechanical testing. Total ROM (Figure 1B) was significantly (p = 0.01) reduced in DCT hydrogel injected discs compared to degenerate discs prior to injection, and was not different (p = 0.15) to healthy control discs. There was also a trend (p = 0.08) towards decreased neutral zone ROM (Figure 1C) in the DCT gel injected group compared to degenerate discs prior to injection. Neutral zone modulus (Figure 1D) was significantly (p = 0.03) increased following DCT hydrogel injection compared to degenerative discs; NZ modulus of DCT hydrogel injected discs was not different (p = 0.32) compared to healthy control discs. Compressive modulus (Figure 1E) was not significantly altered by hydrogel injection, and was still significantly lower than control. Average force-displacement curves generated via LOWESS smoothing for each experimental group (Figure 1F) illustrate the reductions in ROM and increases in NZ modulus relative to controls following DCT gel delivery to degenerate discs.

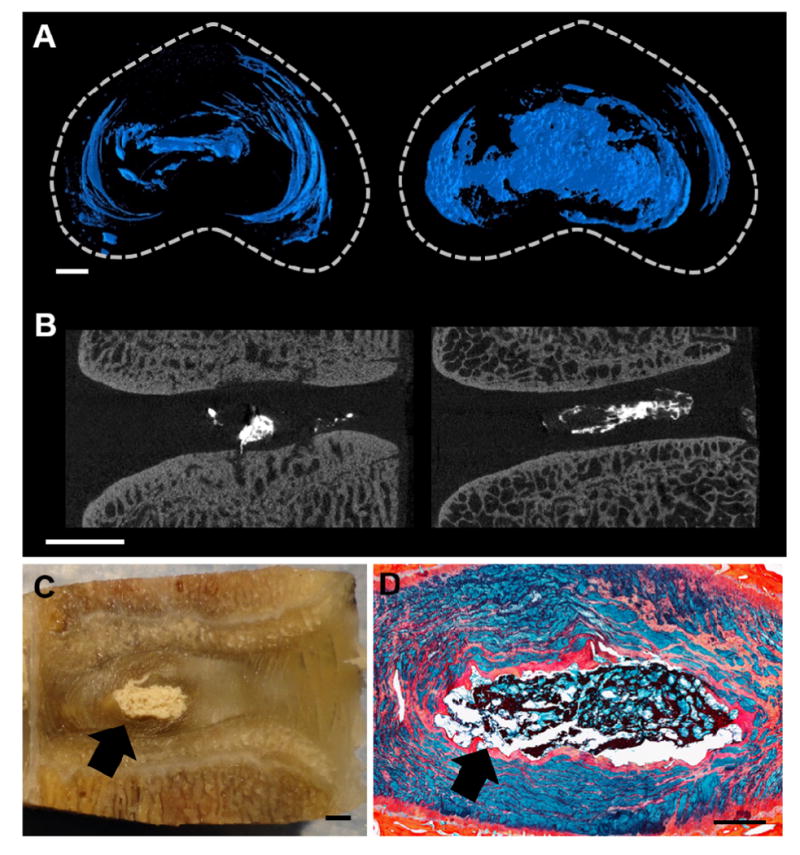

μCT scans of injected discs following mechanical testing provided a three dimensional (Figure 2A) rendering of hydrogel distribution throughout both the NP and the AF lamellar structure (Figure 2B). Macroscopic inspection (Figure 2C) of motion segments subjected to mechanical testing illustrated that the DCT hydrogel remained contained within the disc, with no evidence of extrusion. This was confirmed via Alcian blue and picrosirius red stained histological sections (Figure 2D), in which the injected DCT hydrogel stains intensely with picrosirius red.

Figure 2. Detection of radiopaque DCT hydrogel in the degenerate disc.

Representative (A) axial views of 3D μCT reconstructions, and (B) 2D sagittal μCT slices showing the radiopaque hydrogel within the disc (scale = 2mm). (C) Photograph of a DCT hydrogel injected motion segment following mechanical testing (scale = 2mm). The arrow indicates gel location. (D) Alcian blue and picrosirius red stained histology section illustrating the DCT hydrogel within the NP region (scale = 1 mm). The arrow indicates gel location.

Addition of the zirconia nanoparticles to the DCT hydrogel significantly (p = 0.02) increased the equilibrium modulus of the hydrogel. The equilibrium modulus of the DCT hydrogel alone was 17.6 ± 4.4 kPa, while the equilibrium modulus of the DCT hydrogel with zirconia nanoparticles was 67.9 ± 12.7 kPa.

3.2 MSC and NP Cell Survival and Matrix Production

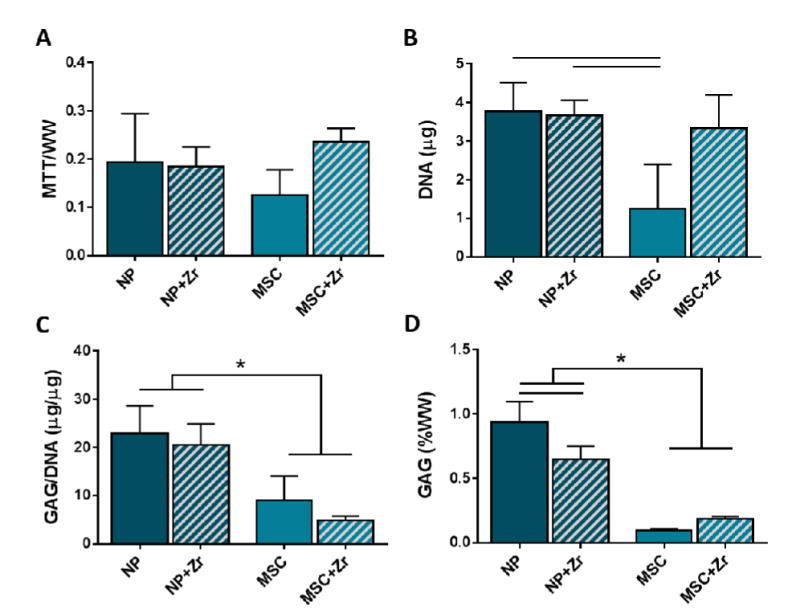

The incorporation of zirconia nanoparticles with the DCT hydrogel had no effect (p = 0.261) on goat MSC or NP cell metabolic activity (Figure 3A) following 2 weeks of culture in chondrogenic media. In MSC seeded hydrogels, there was a trend (p=0.06) towards an increase in DNA content (Figure 3B) in zirconia nanoparticle hydrogels compared to hydrogels without zirconia nanoparticles, while no differences in DNA content were found between NP cell seeded constructs with and without zirconia nanoparticles. GAG content per DNA was also not affected by the addition of zirconia nanoparticles to the hydrogel for either cell type, although it was noted that NP cells produced significantly higher (p < 0.001) amounts of GAG than MSCs in vitro, irrespective of the presence of zirconia nanoparticles (Figure 3C). Hydrogel GAG content normalized to wet weight (Figure 3D) showed similar trends as GAG content per DNA, however, GAG (%WW) was significantly reduced in NP seeded hydrogels with zirconia nanoparticles compared to hydrogels without zirconia nanoparticles.

Figure 3. Effect of zirconia nanoparticles on goat cell metabolic activity and matrix production.

(A) Metabolic activity as measured by the MTT assay, (B) DNA content, and GAG content normalized to (C) DNA and (D) construct wet weight after 2 weeks of culture for goat MSC and NP cells seeded in DCT gel constructs with and without zirconia nanoparticles (n=3 per group, * =p<0.05).

Alcian blue staining (Figure 4A) supported quantitative GAG measurements, with less intense staining in MSC-seeded constructs compared to NP cell-seeded constructs. Alcian blue staining intensity was not affected by the addition of the zirconia nanoparticles to the DCT gel for NP cells; in MSC seeded constructs Alcian blue staining intensity was more evenly distributed following the inclusion of zirconia nanoparticles. Collagen II staining intensity (Figure 4B) was lowest in the MSC-seeded DCT gels without zirconia, and increased with the addition of the zirconia nanoparticles to the MSC-seeded gels. Robust collagen II staining was evident in NP cell-seeded constructs with and without zirconia nanoparticles.

Figure 4. Effect of zirconia nanoparticles on goat cell matrix production in vitro.

(A) Representative Alcian blue-stained sections from goat NP or MSC-seeded DCT hydrogel constructs with and without zirconia nanoparticles after 2 weeks of culture (scale = 0.2 mm). (B) Representative immunohistochemistry for collagen II deposition in goat NP or MSC DCT hydrogel constructs with and without zirconia nanoparticles after 2 weeks of culture (scale = 0.2 mm).

3.3 In Vivo Evaluation of Hydrogel Retention and Distribution in a Large Animal Model

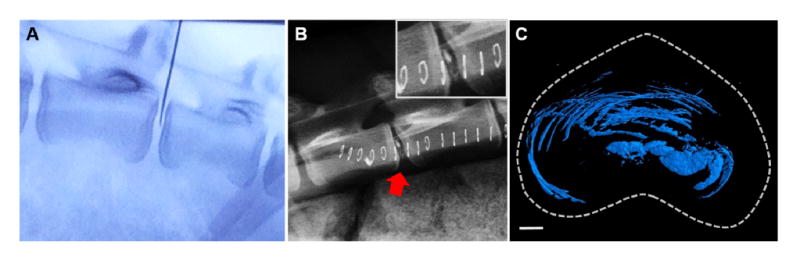

All animals recovered from the surgical procedure to deliver the DCT hydrogel without adverse events, and no complications arose during the 14 week total study duration. In vivo injection volumes ranged from 0.2-0.6 mL of hydrogel (Figure 5A). Visualization during injection of the zirconia-labelled hydrogel using fluoroscopy was possible, and the zirconia-labelled hydrogel was visible in the disc space on lateral plain radiographs of the lumbar spine at all post-operative time points (Figure 5B). 3D μCT reconstructions of the DCT hydrogel treated discs two weeks post-injection showed that the hydrogel was retained within the disc space, with no evidence of extrusion (Figure 5C). Similar to the specimens in which the DCT hydrogel was delivered ex vivo, the hydrogel was distributed throughout the AF lamellar structure and in the NP.

Figure 5. In vivo delivery of the DCT hydrogel in a large animal model of disc degeneration.

(A) Fluoroscopy illustrating in vivo placement of the 22G needle within the disc space prior to injection of the DCT hydrogel. (B) Immediate post-operative lateral radiograph illustrating the radiopaque DCT hydrogel within the disc space. (C) Representative axial view of a 3D μCT reconstruction and of the DCT hydrogel after two weeks in vivo (scale = 2mm).

Presence of the hydrogel within the disc space after two weeks in vivo was confirmed via Alcian blue and picrosirius red stained histological sections (Figure 6A,B), with the hydrogel staining intensely with picrosirius red. Hematoxylin and eosin staining illustrated minimal cellular infiltration into the hydrogel and no apparent adverse reactions of the native surrounding NP tissue (Figure 6C). In instances where the hydrogel was retained in the outer layers of the AF, increased cellularity surrounding the hydrogel was observed (Figure 6D), indicative of a mild fibrotic response.

Figure 6. In vivo retention of the DCT hydrogel.

(A) Alcian blue and picrosirius red stained sagittal section of a representative degenerative goat lumbar disc two weeks following injection of the DCT hydrogel (scale = 1mm). (B) Higher magnification Alcian blue and picrosirius red staining of the DCT hydrogel within the disc (scale =1 mm). (C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the hydrogel within the outer AF, illustrating a mild fibrous response (scale = 50 μ m, gel indicated by white asterisk). Inset of boxed region illustrates increased cellularity immediately adjacent to the hydrogel (inset scale = 20 μm). (D) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the gel within the NP (scale = 50 μm, hydrogel indicated by white asterisk).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the translational feasibility of a triple interpenetrating network DCT hydrogel for the treatment of mild to moderate disc degeneration. The DCT hydrogel is composed of naturally derived materials and gels in vivo without the addition of external crosslinking agents via the formation of Schiff bases, polymerizes rapidly upon mixing of constituents, and achieves peak mechanical properties after approximately 10 hours crosslinking time [27–29]. This hydrogel is non-cytotoxic and does not induce an inflammatory response following subcutaneous injection in mice [28]. Our previous work has illustrated that the DCT hydrogel mimics the mechanical properties of human NP tissue and is supportive of bovine MSC viability and differentiation toward an NP cell-like phenotype in vitro, both with and without exogenous growth factor stimulation [29].

In this study, we rendered the DCT hydrogel radiopaque via the addition of zirconia nanoparticles to facilitate in vivo detection via fluoroscopy and plain radiographs. This enabled confirmation of successful delivery, and allowed for longitudinal monitoring of hydrogel retention in the disc postoperatively. The ability to non-invasively monitor hydrogel retention and extrusion in long-term preclinical studies will be critical to establishing the safety of this therapeutic approach prior to advanced clinical translation. Given our intent to use this hydrogel as a carrier for stem cells to support long-term native tissue regeneration, it was important to confirm that the inclusion of zirconia nanoparticles did not negatively impact the viability or matrix producing capacity of those cells, as a first step towards evaluating the safety of the DCT hydrogel for clinical application. Zirconia nanoparticles have been used previously to render electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone) scaffolds radiopaque. The nanoparticles were found to be cyto-compatible with bovine MSCs and did not promote osteogenesis with in vitro culture or in the disc space in vivo [34]. In this study, the addition of the zirconia nanoparticles to the DCT gel did not significantly affect the viability (as measured by MTT and DNA content) of goat NP cells, although there was a trend towards a positive effect on MSC viability (Figure 3). Glycosaminoglycan content was also not significantly affected by the inclusion of zirconia nanoparticles for both cell types. In the case of goat MSC-seeded DCT gel constructs, addition of the zirconia nanoparticles appeared to increase the collagen II content, as characterized by immunohistochemical staining (Figure 4), but not GAG content. This may be due to the zirconia nanoparticles enhancing sequestration of the matrix produced by the MSCs in this 3D environment [36]. These data suggest that MSCs could be successfully delivered with the radiopaque DCT gel to regenerate the NP without compromising cell function and that there should be no negative impact on the endogenous NP cell population.

A critical benchmark for the success of any injectable implant to treat disc degeneration is the normalization of mechanical properties. Here, we demonstrate through ex vivo studies that DCT hydrogel injected into degenerate large animal discs can improve spine motion segment mechanical function. In prior work, we showed that goat lumbar discs degenerated in vivo via ChABC injection exhibited greater total and NZ ROM as well as lower NZ and compressive moduli [31].These mechanical alterations were consistent with a reduction in NP pressure via a loss of NP proteoglycans [37]. In the present study, DCT gel injection increased NZ modulus and reduced ROM of these same degenerative discs to within the range of non-degenerate control discs. While compressive modulus was not significantly altered by DCT gel injection, this is consistent with previous work showing that the NP, (where the majority of the injected hydrogel was distributed), contributes more substantially to NZ mechanics than to compressive mechanical properties [38]. These results complement previous ex vivo studies in cadaveric ovine and human discs that showed that injection of DCT hydrogel improves the ROM of lumbar spine segments following nucleotomy [29,30].

As a final step towards translation, we used our preclinical large animal model to show that the DCT gel can be successfully injected into degenerate discs in vivo, and that the gel remains completely contained within the disc space without extrusion for 2 weeks of load-bearing activity. This finding is of clinical importance, as prior studies have shown that, while hydrogels for NP augmentation can mimic native disc mechanics during ex vivo tests, they often fail via extrusion following implantation in vivo in large animal models [39–41]. The DCT gel has the additional benefit of being suitable for minimally invasive injectable delivery via a 22G needle, and its delivery creates minimal damage to the AF in our large animal model. Previous work has shown that extensive damage to the AF caused by performing a nucleotomy to deliver a hydrogel implant to the NP space results in scarring of the annulus and degeneration of the native disc tissue [42]. Our previous work demonstrated that a sham saline injection via a 22G needle into goat lumbar discs does not cause any discernable degenerative changes to the disc, thus, delivery of the DCT gel through a 22G needle is unlikely to exacerbate existing degeneration [31]. Our short term in vivo results also suggest there were no adverse or inflammatory reactions to the radiopaque DCT gel within the disc space, further supporting the use of this hydrogel in long-term in vivo studies in conjunction with delivery of MSCs or native disc cells to stimulate disc regeneration.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size and short experimental duration following hydrogel delivery for the in vivo portion of this study. While the inclusion of zirconia nanoparticles did not significantly impact cell viability or matrix production, it did increase the equilibrium modulus of the hydrogel itself – a consideration for future in vivo studies of the effect of the hydrogel on disc mechanics and cell differentiation. Also, the effect of the zirconia nanoparticles on hydrogel collagen content was not quantified in the current study, as the hydrogel is inherently composed of collagen in the teleostean component. In the future, techniques that permit the labelling of nascent matrix formation could be utilized to assess this [43]. As our results showed some hydrogel distributed through the lamellar structure of the AF, additional future studies should also investigate the effect of hydrogel delivery on whole disc mechanics in axial rotation and bending. Ongoing work is aimed at more thoroughly characterizing the acute response to hydrogel delivery to degenerate goat discs using multiple outcome measures, including quantifying changes in animal activity and gait that may occur as a consequence of degeneration and again following treatment. Such functional changes would be of particular clinical significance. Finally, long term studies using this preclinical model will be necessary to determine the regenerative potential of combined stem cell and hydrogel delivery.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrated that a radiopaque, injectable, triple interpenetrating network DCT hydrogel significantly improved the mechanical properties of degenerate discs ex vivo, supported the viability and preserved the matrix-producing capacity of MSCs and NP cells in vitro, and could be successfully delivered in vivo to degenerate discs in a clinically-relevant large animal model. Moreover, the gel remained contained within the disc space for 2 weeks of normal activity and resulted in no adverse reaction in the surrounding tissue. Ongoing and future studies will progress this therapeutic strategy along the pathway to clinical translation by evaluating the long-term regenerative potential of cell-seeded DCT hydrogels in our preclinical large animal model of disc degeneration.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Definition of mechanical testing outcomes. Total range of motion and neutral zone range of motion were defined as illustrated for specimen force-displacement curves, and moduli calculated as the slope of these regions.

Figure S2. Immunohistochemistry controls. No primary antibody controls for cell seeded hydrogels with and without zirconia nanoparticles (scale = 100 μm).

Statement of Significance.

The results of this work illustrate that a radiopaque hydrogel is capable of normalizing the mechanical function of the degenerative disc, is supportive of disc cell and mesenchymal stem cell viability and matrix production, and can be maintained in the disc space without extrusion following intradiscal delivery in a preclinical large animal model. These results support evaluation of this hydrogel as a minimally invasive disc therapeutic in long-term preclinical studies as a precursor to future clinical application in patients with disc degeneration and low back pain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (RR&D I01RX00132). The authors would also like to acknowledge the Sharpe Foundation and the Departments of Neurosurgery and Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania for financial support. Core equipment used in this study was provided by the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (National Institutes of Health P30 AR 069619). The authors would also like to acknowledge the veterinary staff at the Penn Vet Center for Preclinical Translation, New Bolton Center, for their assistance with animal care and management throughout the study, as well as Dr. Julie Engiles for the veterinary pathology consultation.

Role of the Funding Source: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Veteran's Affairs. No funding source had a role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cassidy J, Hiltner A. Hierarchical structure of the intervertebral disc. Connect Tissue Res. 1989;23:75–88. doi: 10.3109/03008208909103905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker MH, Anderson DG. Molecular basis of intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine J. 2004;4:158S–166S. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inoue H. Three-dimensional architecture of lumbar intervertebral discs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1981;6:139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humzah MD, Soames RW. Human intervertebral disc: structure and function. Anat Rec. 1988;220:337–56. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092200402. doi:10.1002/ar. 1092200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hukins DW. A simple model for the function of proteoglycans and collagen in the response to compression of the intervertebral disc. Proceedings Biol Sci. 1992;249:281–285. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0115. doi:10.1098/rspb. 1992.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haefeli M, Kalberer F, Saegesser D, Nerlich AG, Boos N, Paesold G. The course of macroscopic degeneration in the human lumbar intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:1522–1531. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000222032.52336.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urban JPG, Roberts S. Degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:120–130. doi: 10.1186/ar629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raj PP. Intervertebral Disc : Pathophysiology-Treatment. 2008;8:18–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2007.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freemont aJ. The cellular pathobiology of the degenerate intervertebral disc and discogenic back pain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:5–10. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States. Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; Rosemont, IL: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.CDC. Prevalence and Most Common Causes of Disability Among Adults — United States, 2005. MMWR. 2009;58:421–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tosteson ANA, Birkmeyer N, Herkowitz H, Longley M, Lenke L, Emery S, Hu SS. Surgical Compared with Nonoperative Treatment for Lumbar Degenerative Spondylolisthesis. 2009:1295–1304. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blumenthal S, Mcafee PC, Guyer RD, Hochschuler SH, Geisler FH, Holt RT, Garcia R, Regan JJ, Ohnmeiss DD, Cunningham B, Eng M, Holsapple G, Adams K, Dmietriev A, Maxwell JH, Isaza J, Blumenthal S, Guyer RD, Dmietriev A, Maxwell JH, Regan JJ, Isaza J. A prospective, randomized, multicenter Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption study of lumbar total disc replacement with the CHARITE artificial disc versus lumbar fusion: part II: evaluation of radiographic outcomes and correlation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1576–1583. doi: 10.1016/S0276-1092(08)70536-4. E390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart LG, Deyo RA, Cherkin DC. Cherkin, Physician office visits for low back pain. Frequency, clinical evaluation, and treatment patterns from a U.S. national survey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:11–19. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Priyadarshani P, Li Y, Yao L. Advances in biological therapy for nucleus pulposus regeneration. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peroglio M, Grad S, Mortisen D, Sprecher CM, Illien-Jünger S, Alini M, Eglin D. Injectable thermoreversible hyaluronan-based hydrogels for nucleus pulposus cell encapsulation. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:839–849. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1976-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thorpe AA, Boyes VL, Sammon C, Le Maitre CL. Thermally triggered injectable hydrogel, which induces mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to nucleus pulposus cells: Potential for regeneration of the intervertebral disc. Acta Biomater. 2016;36:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collin EC, Grad S, Zeugolis DI, Vinatier CS, Clouet JR, Guicheux JJ, Weiss P, Alini M, Pandit AS. An injectable vehicle for nucleus pulposus cell-based therapy. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2862–2870. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Su W, Yang S, Gefen A, Lin F. In situ forming hydrogels composed of oxidized high molecular weight hyaluronic acid and gelatin for nucleus pulposus regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:5181–5193. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vadalà G, Russo F, Musumeci M, D'Este M, Cattani C, Catanzaro G, Tirindelli MC, Lazzari L, Alini M, Giordano R, Denaro V. A clinically relevant hydrogel based on hyaluronic acid and platelet rich plasma as a carrier for mesenchymal stem cells: Rheological and biological characterization. J Orthop Res. 2016:1–25. doi: 10.1002/jor.23509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park SH, Cho H, Gil ES, Mandal BB, Min BH, Kaplan DL. Silk-Fibrin/Hyaluronic Acid Composite Gels for Nucleus Pulposus Tissue Regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2999–3009. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsaryk R, Gloria A, Russo T, Anspach L, De Santis R, Ghanaati S, Unger RE, Ambrosio L, Kirkpatrick CJ. Collagen-low molecular weight hyaluronic acid semi-interpenetrating network loaded with gelatin microspheres for cell and growth factor delivery for nucleus pulposus regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2015;20:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim DH, Martin JT, Elliott DM, Smith LJ, Mauck RL. Phenotypic stability, matrix elaboration and functional maturation of nucleus pulposus cells encapsulated in photocrosslinkable hyaluronic acid hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2015;12:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reza AT, Nicoll SB. Characterization of novel photocrosslinked carboxymethylcellulose hydrogels for encapsulation of nucleus pulposus cells. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin HA, Gupta MS, Varma DM, Gilchrist ML, Nicoll SB. Lower crosslinking density enhances functional nucleus pulposus-like matrix elaboration by human mesenchymal stem cells in carboxymethylcellulose hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res - Part A. 2016;104:165–177. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wachs R, Hoogenboezem E, Huda H, Xin S, Porvasnik S, Schmidt C. Creation of an injectable in situ gelling native extracellular matrix for nucleus pulposus tissue engineering. Spine J. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weng L, Chen X, Chen W. Rheological Characterization of in situ Crosslinkable Hydrogels Formulated from Oxidized Dextran and N-Carboxyethyl Chitosan. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:1109–1115. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Qadeer A, Mynarcik D, Chen W. Delivery of rosiglitazone from an injectable triple interpenetrating network hydrogel composed of naturally derived materials. Biomaterials. 2011;32:890–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith LJ, Gorth DJ, Showalter BL, Chiaro Ja, Beattie EE, Elliott DM, Mauck RL, Chen W, Malhotra NR. In Vitro Characterization of a Stem-Cell-Seeded Triple-Interpenetrating-Network Hydrogel for Functional Regeneration of the Nucleus Pulposus. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:1841–1849. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2013.0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malhotra NR, Han WM, Beckstein J, Cloyd J, Chen W, Elliott DM. An injectable nucleus pulposus implant restores compressive range of motion in the ovine disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:E1099–105. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31825cdfb7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gullbrand SE, Malhotra NR, Schaer TP, Zawacki Z, Martin JT, Bendigo JR, Milby AH, Dodge GR, Vresilovic EJ, Elliott DM, Mauck RL, Smith LJ. A large animal model that recapitulates the spectrum of human intervertebral disc degeneration. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2017;25:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beckstein JC, Sen S, Schaer TP, Vresilovic EJ, Elliott DM. Comparison of animal discs used in disc research to human lumbar disc: axial compression mechanics and glycosaminoglycan content. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:E166–73. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318166e001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demian HW, McDermott K. Regulatory perspective on characterization and testing of orthopedic bone cements. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1607–1618. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(97)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin JT, Milby AH, Ikuta K, Poudel S, Pfeifer CG, Elliott DM, Smith HE, Mauck RL. A radiopaque electrospun scaffold for engineering fibrous musculoskeletal tissues: Scaffold characterization and in vivo applications. Acta Biomater. 2015;26:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin JT, Gorth DJ, Beattie EE, Harfe BD, Smith LJ, Elliott DM. Needle puncture injury causes acute and long-term mechanical deficiency in a mouse model of intervertebral disc degeneration. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:1276–1282. doi: 10.1002/jor.22355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pattnaik S, Nethala S, Tripathi A, Saravanan S, Moorthi A, Selvamurugan N. Chitosan scaffolds containing silicon dioxide and zirconia nano particles for bone tissue engineering. Int J Biol Macromol. 2011;49:1167–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boxberger JI, Sen S, Yerramalli CS, Elliott DM. Nucleus Pulposus Glycosaminoglycan Content is Correlated with Axial Mechanics in Rat Lumbar Motion Segments. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1906–1915. doi: 10.1002/jor.20221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cannella M, Arthur A, Allen S, Keane M, Joshi A, Vresilovic E, Marcolongo M. The role of the nucleus pulposus in neutral zone human lumbar intervertebral disc mechanics. J Biomech. 2008;41:2104–2111. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Detiger S, de Bakker J, Emanuel K, Schmitz M, Vergroesen P, van der Veen A, Mazel C, Smit T. Translational challenges for the development of a novel nucleus pulposus substitute: Experimental results from biomechanical and in vivo studies. J Biomater Appl. 2015;0:1–12. doi: 10.1177/0885328215611946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen MJ, Schoonmaker JE, Bauer TW, Williams PF, Higham Pa, Yuan Ha. Preclinical evaluation of a poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogel implant as a replacement for the nucleus pulposus. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:515–523. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000113871.67305.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reitmaier S, Kreja L, Gruchenberg K, Kanter B, Silva-Correia J, Oliveira JM, Reis RL, Perugini V, Santin M, Ignatius A, Wilke HJ. In vivo biofunctional evaluation of hydrogels for disc regeneration. Eur Spine J. 2014;23:19–26. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2998-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Omlor GW, Nerlich AG, Lorenz H, Bruckner T, Richter W, Pfeiffer M, Gühring T. Injection of a polymerized hyaluronic acid/collagen hydrogel matrix in an in vivo porcine disc degeneration model. Eur Spine J. 2012;21:1700–1708. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2291-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McLeod CM, Mauck RL. High fidelity visualization of cell-to-cell variation and temporal dynamics in nascent extracellular matrix formation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38852. doi: 10.1038/srep38852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Definition of mechanical testing outcomes. Total range of motion and neutral zone range of motion were defined as illustrated for specimen force-displacement curves, and moduli calculated as the slope of these regions.

Figure S2. Immunohistochemistry controls. No primary antibody controls for cell seeded hydrogels with and without zirconia nanoparticles (scale = 100 μm).