Abstract

Clinical observation shows that men and women are different in prevalence, symptoms, and responses to treatment of several psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia. While the etiology of gender differences in schizophrenia is only partially understood, recent genetic studies suggest significant sex-specific pathways in the schizophrenia between men and women. More research is needed to understand the causal roles of sex differences in schizophrenia in order to ultimately develop sex-specific treatment of this serious mental illness. In the present review, we will outline the current evidence on the sex-related factors interaction with disease onset, symptoms and treatment of schizophrenia, and discuss the potential molecular mechanisms that may mediate their cooperative actions in schizophrenia pathogenesis

Keywords: schizophrenia, gender-related factor, sex-specific treatment

Schizophrenia is one of the most serious mental illnesses with about one in a hundred people developing the disorder over a lifetime. It is evidenced that men and women have different outcome of the disease in age of onset, symptoms, disease severity, and number of treatment[1]. Men show an earlier age at onset, higher propensity to negative symptoms, lower social functioning, and co-morbid substance abuse than that is women, whereas women display relatively late onset of the disease with more affective symptoms. While the reasoning of sex differences in schizophrenia remains uncovered, in this mini review, we gathered recent discoveries in schizophrenia research and discussed gender-related factors in the process of the disease as well as response to treatment with a hope to provide some useful insight for sex-specific treatment for schizophrenia in the future.

Sex differences in age at onset

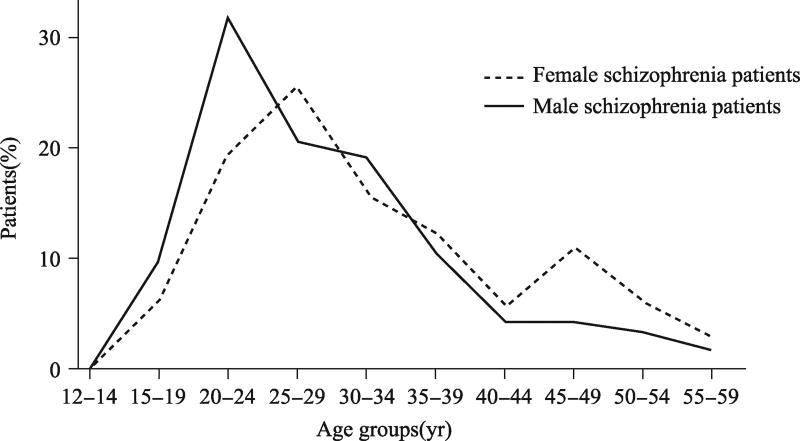

While men and women have similar prevalence of Schizophrenia, most of studies demonstrated that female onset is typically 3–5 years later than males. It is now accepted that men has a single peak age for onset which is between 21 and 25 years old and women have two peaks age of onset, one between 25 and 30 years old and another one is after 45 years old as shown in Fig. 1[2–5]. It is also observed that women with schizophrenia are more associated with seasonality of first admissions as compared to schizophrenic men[6]. The delayed two peaks of onset ages in women have been consistent with other studies which reported that women make up 66%–87% of patients with onset after the age of 40–50 years[7].

Fig. 1.

Sex differences in onset age of schizophrenia

Note: Men (solid line) have a notable peak of incidence in late adolescence and a subsequent sharp decline into middle age. The peak age of incidence rates in women (dot line) appears in adolescence as well as after 45 years old[2].

While the underlying molecular mechanisms of sex differences in schizophrenia onset remains unclear, early development of neuronal system has been an interesting hypothesis. Recent studies of schizophrenia patients showed substantial gender differences in DNA methylation and one study with limited number of patient samples identified the top autosomal SNP was rs12619000 with 50% potential methylation in males and 95% in females (P = 0. 000 008)[8]. Genetic polymorphisms within the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) studies demonstrated a significant difference in age of psychosis onset in female schizophrenia patients with respect to the TG-FB1 +869T/C polymorphism, suggesting TGF-β signaling might be a valid link contributing to observed differences in age of onset between male and female schizophrenia patients[9].

Sex differences in symptoms

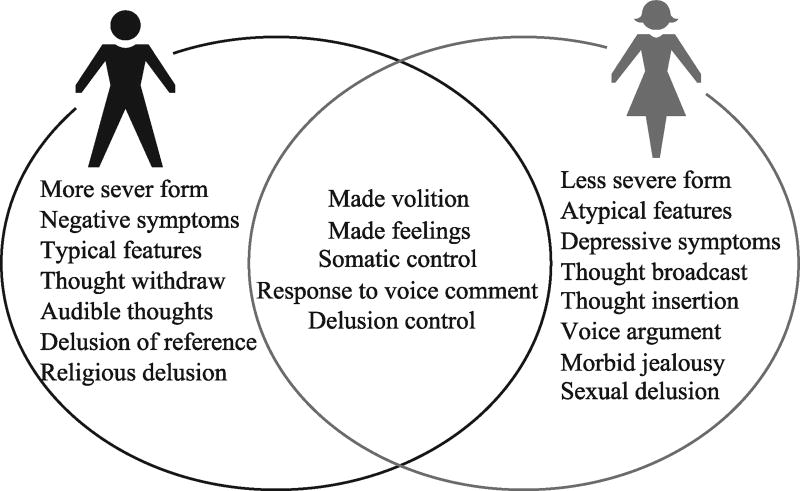

As shown in Fig. 2, there are sex differences in the symptoms of schizophrenia. For example, men with schizophrenia appear to have more negative symptoms and more severe clinical features than females, particularly in social withdrawal, substance abuse and blunted or incongruent affects than female patients. Women with schizophrenia often present with more mood disturbance and depressive symptoms as well as affective symptoms. Interestingly, such sex-specific symptoms in male schizophrenia patients were also observed in subjects with high risk for this disease[10]. The age of onset is also associated with type of symptoms. For example, studies showed that women with late onset of schizophrenia may have less severe negative symptoms and present with more positive symptoms, particularly sensory hallucinations and persecutory delusions[11].

Fig. 2.

Sex differences in distribution of various symptoms between male and females patients

Note: Data source: http://dysphrenia. hpage. co. in/research phenomenological study of thinking and perceptual disorders in schizophrenia fulltext 76041325.html and http://www.jpma.org.pk/PdfDownload/2907.pdf

Schizophrenic patients have cognitive impairments, particularly immediate memory, delayed memory and language. While the sex differences in cognitive impairment between male and female schizophrenia patients remain further investigation, studies showed that male schizophrenic patients had more serious cognitive deficits than female patients in immediate and delayed memory, but not in language, visuospatial and attention indices by recent studies[12]. Such a female favored immediate and delayed memory has been associated with sex differences in brain structure and activities[13, 14].

In addition, several recent studies suggest a gender-specific association of certain dopaminergic genes (catechol-O-methyltransferase, monoamine oxidase) with schizophrenia and type of symptoms. While the deficit and excess of dopamine have been related to positive and negative schizophrenia symptoms in general[15], recent studies of the association between polymorphism in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene and symptoms of schizophrenia in adults demonstrated evidence that the biological effect of the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene may be related to the negative dimension of schizophrenia in males[16]. Furthermore, sex differences in the GABAergic regulation of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) function may contribute to the differences observed in the symptoms of male and female patients with schizophrenia. For example, male schizophrenia patients expressed lower level of GABAergic genes in the ACC compared to the controls, particularly with significantly lower expression levels of GABA-Aα5, GABA-Aβ1, and GABA-Aε. However, the expression of GABAergic genes was higher in the female schizophrenia patients compared to sex-matched controls, especially with significantly higher expression of the GABA-Aβ1 and GAD67 genes[17]. Whether the sex differences in schizophrenia symptoms are disease specific? A recent study found that symptoms such as a greater propensity to substance abuse and lower social functioning are also more prevalent in men from the general population, suggesting that gender differences observed in schizophrenia symptoms, particularly the social function, are not necessarily schizophrenia-specific[10].

Sex differences in response to antipsychotic treatments

Gender-specific treatment strategies for psychosis have been suggested in recent years. Gender differences can inform more effective and gender-specific pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment, such as drug dosage, side-effects, and compliance[18]. Female patients show better treatment response than men[19, 20] and approximately 50% less hospitalizations[21]. On the other hand, men with psychosis often require higher dosages of antipsychotic drugs related to their greater liver enzymatic clearance[22]. Male mental patients also have greater cigarette smoking and coffees drinking that promote liver enzymes for drug clearance. On the other hand, compared to young women, postmenopausal women typically required larger doses of antipsychotics associated with decline of endogenous estrogen levels[22]. As hormone might interact with antipsychotics, there are studies showed that estrogen therapy alone or as an adjunctive therapy to antipsychotics demonstrated faster improvement in men and women with schizophrenia[23]. Furthermore, as most of antipsychotics have side effects, studies showed that women developed more side effects such as hyperprolactinaemia[24], hypotension[25], weight gain[26], and enhancement of autoimmune proclivity[27]. However, women demonstrate better treatment compliance and better outcome in response to treatments than men[28]. One of the hypotheses is that women response better than men in treatment of schizophrenia is related to women’s better-preserved social skills[29]. Based on the differences in response to treatment of schizophrenia between men and women, the therapy might focus on eliminating substance abuse, developing socio-occupational skills, and reducing negative externalizing behaviors in men, while treatment for women might be more on reducing affective symptoms, and ameliorating comorbid depression and anxiety. Since many women have a later illness onset and more socio-occupational losses, studies suggested that the therapy for women should target on re-establishing roles and relationships while men have to attain these for the first time[30].

Sex dependent factors in schizophrenia

Multiple lines of evidence have also highlighted that sex-related factors play a potentially important role in shaping the clinical trajectory of schizophrenia.

Hormone hypotheses

Evidence for genetic and neurodevelopmental factors remains weak but support has garnered for the hypothesis that the sex differences in schizophrenia is involved gonadal hormones, such as estrogen which plays possible neuroprotective roles in against schizophrenia pathology in women. The estrogen hypothesis is supported by late on set age and second incidence peak around menopausal age in women. Indeed, estrogen deficiency is highly related to severity of psychiatric symptoms in women during menopause. For example, female schizophrenia patients often have more severe symptoms in the low estrogen phase of their menstrual cycle[31]. Interestingly, the negative correlation between plasma estrogen levels and schizophrenia symptoms was also reported in male patients[32]. The biochemical nature of the neuroprotective effects of estrogens has not been fully qualified yet, but a number of studies point to a direct implication of the dopaminergic system[33, 34], in addition to glutamate and GABA. Furthermore, the relations between estrogens and DA are supported by clinical and preclinical evidence[35]. What is about testosterone, the major male hormone in schizophrenia? Studies found that low levels of testosterone appear to be associated with more severe symptoms, although results are less consistent than for estrogens[36, 37]. For instance, studies found that schizophrenia patients with low levels of testosterone often have predominantly negative symptoms, and the serum testosterone levels are associated with a greater severity of negative symptoms[38]. Recently, oxytocin, an important hormone for reproductive function, becomes a potential therapeutic target for schizophrenia. Several studies suggest that schizophrenia patients with higher levels of plasma oxytocin developed fewer psychotic symptoms[39, 40], improved cognition[41], while oxytocin is thought to regulate central dopamine, and might therefore exhibit antipsychotic effects[42].

Sex chromosome hypotheses

While sex hormones have regulating mental functions, recent studies suggested that sex chromosomes, XX or XY, may roles in neurodevelopment and contribute sex-specific cognitive functions. For example, individuals with abnormal number of X or Y chromosomes often have higher incidence in motor impairment and psychiatric disorders than normal populations[43]. The numbers of sex chromosomes in schizophrenia study have been limited, but suggested and confirmed that higher prevalence of psychosis in individuals with excess of sex chromosome, particularly × chromosomes[44, 45], while whether an association also exists with XYY remains unknown. It was hypothesized that X chromosome instability predisposes to psychosis. In consistent with findings of higher risk of individuals with more numbers of sex chromosomes in schizophrenia, other groups also reported the linkage of schizophrenia to the proximal short arm of the X-chromosome[46, 47] or chromosomal lesions are prevalent in schizophrenics[48]. Although the hypothesis that X or Y chromosomes associated gene for susceptibility to psychosis has been challenged by numbers of studies, with during the past few years, chromosome X abnormalities and sex-specific patterns of transmission have been identified in schizophrenia patients.[49, 50]

Conclusion

Consideration of gender differences in schizophrenia and other psychosis provides an important insight for understanding the sex-specific characterizes of the diseases onset, symptoms, and opportunity to deliver sex-specific treatments and care for schizophrenia patients. It is critical to present such knowledge or awareness to clinical services and researchers with the opportunity to develop interventions which might work in a gender-specific preventative or prophylactic manner.

References

- 1.Nawka A, Kalisova L, Raboch J, et al. TW. Gender differences in coerced patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:257. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones PB. Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;54(Suppl):S5–S10. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkbride JB, Errazuriz A, Croudace TJ, et al. Incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in England, 1950 – 2009: a systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e31660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nowrouzi B, Kamhi R, Hu J, et al. Age at onset mixture analysis and systematic comparison in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Is the onset heterogeneity dependent on heterogeneous diagnosis? Schizophr Res. 2015;164(1–3):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angermeyer MC, Kühn L. Gender differences in age at onset of schizophrenia. An overview. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1988;237(6):351–364. doi: 10.1007/BF00380979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takei N, O'Callaghan E, Sham P, et al. Seasonally of admissions in the psychoses: effect of diagnosis, sex, and age at onset. Br J Psyehiat. 1992;161:506–511. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard R, Jeste D. Late onset schizophrenia. In: Weinberger DR, Harrison PJ, editors. Schizophrenia. Chichester, West Sussex; WileyBlackwell: 2011. pp. 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali Bani Fatemi CZ, De Luca V. Early onset schizophrenia: gender analysis of genome-wide potential methylation. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;449:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frydecka D, Misiak B, Pawlak-Adamska E, et al. Sex differences in TGFB-β signaling with respect to age of onset and cognitive functioning in schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:575–584. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S74672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rietschel L, Lambert M, Karow A, et al. Clinical high risk for psychosis: gender differences in symptoms and social functioning. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2015 Mar 24; doi: 10.1111/eip.12240. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindamer LA, Lohr JB, Harris MJ, et al. Gender-related clinical differences in older patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(1):61–67. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han M, Huang XF, Chen Da C, et al. Gender differences in cognitive function of patients with chronic schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39(2):358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fine C. Neuroscience. His brain, her brain? Science. 2014;346(6212):915–916. doi: 10.1126/science.1262061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingalhalikar M, Smith A, Parker D, et al. Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(2):823–828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316909110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laruelle M. Schizophrenia: from dopaminergic to glutamatergic interventions. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2014;14(1):97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Castro-Catala M, Barrantes-Vidal N, Sheinbaum T, et al. COMT-by-sex interaction effect on psychosis proneness. Biomed Res Int. 2015:829237. doi: 10.1155/2015/829237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bristow GC, Bostrom JA, Haroutunian V, et al. Sex differences in GABAergic gene expression occur in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;167(1–3):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abel KM, Drake R, Goldstein JM. Sex differences in schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(5):417–428. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.515205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riecher-Rössler A, Häfner H. Gender aspects in schizophrenia: bridging the border between social and biological psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2000;(407):58–62. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grigoriadis S, Seeman MV. The role of estrogen in schizophrenia: implications for schizophrenia practice guidelines for women. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47(5):437–442. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai PR, Lawson KA, Barner JC, et al. Identifying patient characteristics associated with high schizophrenia-related direct medical costs in community-dwelling patients. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(6):468–477. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.6.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith S. Gender differences in antipsychotic prescribing. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(5):472–484. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.515965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulkarni J, de Castella A, Headey B, et al. Estrogens and men with schizophrenia: is there a case for adjunctive therapy? Schizophr Res. 2011;125(2–3):278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bushe C, Yeomans D, Floyd T, et al. Categorical prevalence and severity of hyperprolactinaemia in two UK cohorts of patients with severe mental illness during treatment with antipsychotics. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(2 Suppl):56–62. doi: 10.1177/0269881107088436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seeman MV. Gender differences in the prescribing of antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1324–1333. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russell JM, Mackell JA. Bodyweight gain associated with atypical antipsychotics: Epidemiology and therapeutic implications. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(7):537–551. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seeman MV. Secondary effects of antipsychotics: Women at greater risk than men. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(5):937–948. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morken G, Widen J, Grawe R. Non-adherence to antipsychotic medication, relapse and rehospitalisation in recent-on-set schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brabban A, Tai S, Turkington D. Predictors of outcome in brief cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(5):859–864. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riecher-Rossler A, Pfluger M, Borgwardt S. Schizophrenia in women. In: Kohen D, editor. Oxford textbook of women and mental health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 102–111. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grigoriadis S, Seeman MV. The role of estrogen in schizophrenia: implications for schizophrenia practice guidelines for women. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:437–442. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaneda Y, Ohmori T. Relation between estradiol and negative symptoms in men with schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17(2):239–242. doi: 10.1176/jnp.17.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sumner BE, Fink G. Effects of acute estradiol on 5-hydroxytryptamine and dopamine receptor subtype mRNA expression in female rat brain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1993;4(1):83–92. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1993.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fink G, Sumner BE, McQueen JK, et al. Sex steroid control of mood, mental state and memory. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1998;25(10):764–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sánchez MG, Bourque M, Morissette M, et al. Steroids-do-pamine interactions in the pathophysiology and treatment of CNS disorders. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(3):e43–e71. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ritsner MS, Gibel A, Ram E, et al. Alterations in DHEA-metabolism in schizophrenia: two-month case-control study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;16:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ko YH, Jung SW, Joe SH, et al. Association between serum testosterone levels and the severity of negative symptoms in male patients with chronic schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(4):385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sisek-Šprem M, Križaj A, Jukić V, et al. Testosterone levels and clinical features of schizophrenia with emphasis on negative symptoms and aggression. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(2):102–109. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2014.947320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sasayama D, Hattori K, Teraishi T, et al. Negative correlation between cerebrospinal fluid oxytocin levels and negative symptoms of male patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;139(1–3):201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cochran DM, Fallon D, Hill M, et al. The role of oxytocin in psychiatric disorders: a review of biological and therapeutic research findings. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;21(5):219–247. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0b013e3182a75b7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frost K, Keller W, Buchanan R, et al. Plasma oxytocin levels are associated with impaired social cognition and neurocognition in schizophrenia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2014;29(6):577–578. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feifel D. Is oxytocin a promising treatment for schizophrenia? Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(2):157–159. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong DS, Reiss AL. Cognitive and neurological aspects of sex chromosome aneuploidies. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(3):306–318. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeLisi LE, Friedrich U, Wahlstrom J, et al. Schizophrenia and sex chromosome anomalies. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20(3):495–505. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeLisi LE, Devoto M, Lofthouse R, et al. Search for linkage to schizophrenia on the X and Y chromosomes. Am J Med Genet. 1994;54(2):113–121. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320540206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crow TJ, DeLisi LE, Lofthouse R, et al. An examination of linkage of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder to the pseudoautosomal region (Xp22.3) Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(2):159–164. doi: 10.1192/bjp.164.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dann J, DeLisi LE, Devoto M, et al. A linkage study of schizophrenia to markers within Xp11 near the MAOB gene. Psychiatry Res. 1997;70(3):131–143. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)03138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Demirhan O, Ta temir D. Chromosome aberrations in a schizophrenia population. Schizophr Res. 2003;65(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crow TJ. The XY gene hypothesis of psychosis: origins and current status. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2013;162(8):800–824. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldstein JM, Cherkerzian S, Seidman LJ, et al. Sex-specific rates of transmission of psychosis in the New England high-risk family study. Schizophr Res. 2011;128(1–3):150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]