Abstract

Extracts from Glycyrrhiza are traditionally used for the treatment of insomnia and anxiety. Glabridin is one of the main flavonoid compounds from Glycyrrhiza glabra and displays a broad range of biological properties. In the present work, we investigated the effect of glabridin on GABAA receptors. For this purpose, we employed the two-electrode voltage-clamp technique on Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing recombinant GABAA receptors. Through this approach, we observed that glabridin presents a strong potentiating effect on GABAA α1β(1−3)γ2 receptors. The potentiation was slightly dependent on the β subunit and was most pronounced at the α1β2γ2 subunit combination, which forms the most abundant GABAA receptor in the CNS. Glabridin potentiated with an EC50 of 6.3±1.7 µM and decreased the EC50 of the receptor for GABA by approximately 12-fold. The potentiating effect of glabridin is flumazenil-insensitive and does not require the benzodiazepine binding site. Glabridin acts on the β subunit of GABAA receptors by a mechanism involving the M286 residue, which is a key amino acid at the binding site for general anesthetics, such as propofol and etomidate. Our results demonstrate that GABAA receptors are strongly potentiated by one of the main flavonoid compounds from Glycyrrhiza glabra and suggest that glabridin could contribute to the reported hypnotic effect of Glycyrrhiza extracts.

Keywords: GABAA Receptor, Glabridin, Insomnia, Anxiety, Xenopus Oocytes, Glycyrrhiza glabra

Highlights

-

•

We examined the action of constituents of Glycyrrhiza glabra on recombinant GABA(A) receptors.

-

•

The main flavonoid glabridin is a potent and effective potentiator of the GABA evoked current.

-

•

Glabridin acts by the same mechanism as general anesthetics such as propofol.

1. Introduction

GABAA receptors are chloride-selective, heteropentameric ionotropic receptors that mediate fast inhibitory synaptic transmission in the central nervous system. They constitute a target for the majority of clinically relevant anesthetics, e.g., propofol and etomidate [1]. They are also targets for many neuroleptic, anxiolytic and anticonvulsant drugs [2], [3]. GABAA receptors are composed of different combinations of the following subunits: α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ε, π and ϑ [2]. The most prominent native receptors in the CNS are the post-synaptically localized heteromultimers of α, β, and γ subunits. The GABA-binding pocket is formed by the α/β-subunit interface, whereas the benzodiazepine-binding pocket is located at the α/γ interface.

More than ten distinct modulatory binding sites in GABAA receptors are currently known, and these constitute the target of many sedative, anticonvulsive, anxiolytic, antiepileptic, and hypnotic compounds of different chemical classes [4]. Benzodiazepine-site agonists act mainly on γ2-containing GABAA receptors. In contrast, several other modulators, such as the general anesthetics propofol or etomidate, target the β subunit [5]. Flavonoid modulation of GABAA receptors has been the focus of intense research for many years. The mechanism of potentiation is complex, only partially understood, and includes flumazenil-sensitive modulation at the benzodiazepine binding site, flumazenil-insensitive modulation at other sites and second-order modulation of benzodiazepine potentiation [6].

Glabridin is a polyphenolic flavonoid compound from liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra, Fabaceae) and is one of the main components of the flavonoid fraction. It has a wide range of biological properties, ranging from neuroprotective to skin-whitening (reviewed by [7]), and is used in dietary supplements, foods and cosmetic products. Liquorice extracts show hypnotic-sedative actions in animal models and are traditionally used for the treatment of insomnia and anxiety [8], [9], [7]. Prior research showed that low µM concentrations of glabridin strongly potentiate GABA-induced currents in rat dorsal raphe neurons [10]. However, until recently, no data regarding the effect of glabridin on recombinant GABAA receptors has been published, and the mechanism of potentiation has not yet been studied. In the present work, we addressed these questions and studied the effect of glabridin on different subtypes of heterologously expressed GABAA receptors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Expression system

Cloned cDNA for rat α1, β1 and β2, human β3 and murine γ2 in psGEM [11] was linearized with PacI and used as templates for in vitro transcription. cRNAs were prepared using the AmpliCap T7 high-yield message marker kit (Epicenter, Madison, WI), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Oocytes were obtained as previously described [12] and injected with a total amount of 7–20 ng of receptor coding cRNA using an injection-setup from WPI (Nanoliter 2000, Micro4). Injected oocytes were stored in ND 96 (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 200 U/ml Penicillin, 200 μg/ml Streptomycin) at 14 °C. Measurements were performed two to three days after cRNA-injection.

2.2. Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological recordings were performed using the two-electrode voltage clamp technique as previously described [12]. All measurements were performed in normal frog ringer (NFR) (115 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2). Currents were recorded at a typical holding potential −40 mV using the software Cell Works 6.1.1. (NPI).

2.3. Data analysis

The currents evoked by test substances or modulated GABA currents were normalized to the induced currents of standard GABA concentrations. Concentration response data were fitted with the Hill equation using SigmaPlot 8.0. Deviations are represented by the standard error of the mean (SEM). Data sets were tested for statistically significant differences using Student's t-test from Excel 2010 (Microsoft).

3. Results

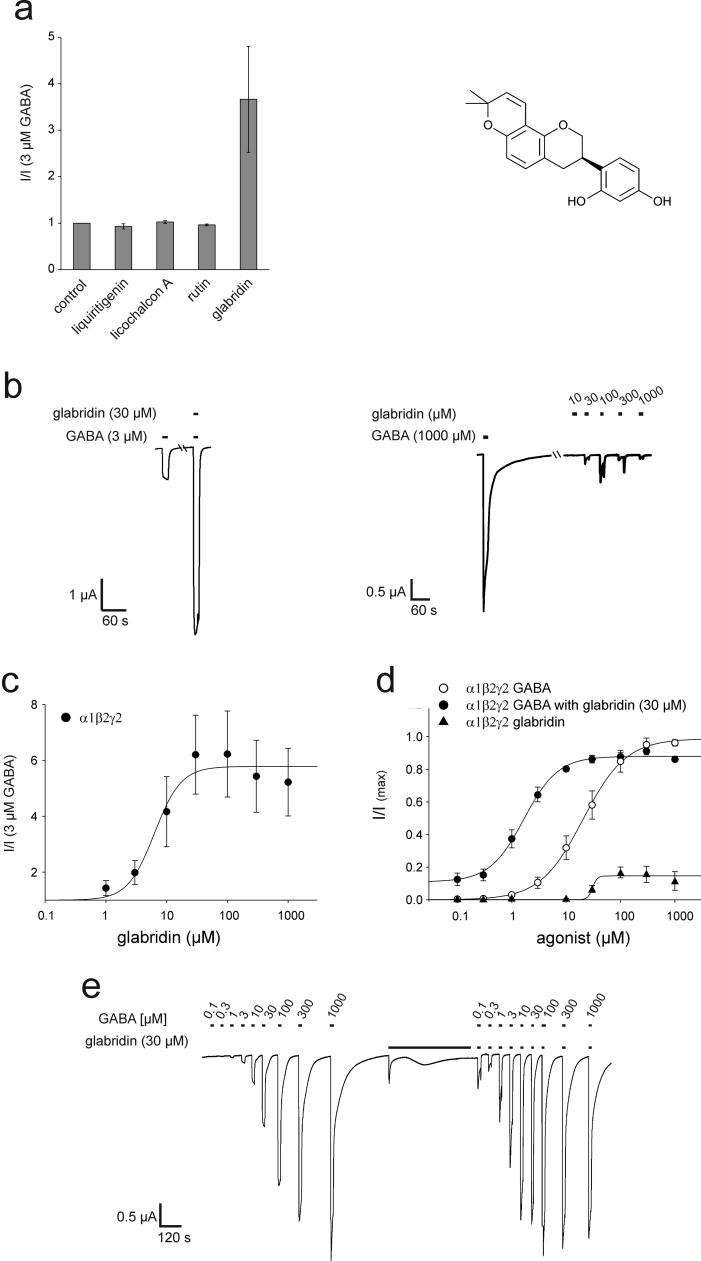

We screened different compounds present in liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra, Fabaceae) for their modulatory action on GABAA receptors using Xenopus laevis oocytes recombinantly expressing α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors and identified glabridin as one of the active constituents (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1). For the detailed pharmacological characterization of glabridin's action of GABAA receptors, we recombinantly expressed various GABAA receptor subunit combinations and measured them by the two-electrode voltage-clamp technique. By this approach, we found that glabridin (Fig. 1a) is a strong positive modulator (Fig. 1b) of recombinantly expressed α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors. As a next step, we investigated this potentiating effect on the current evoked by 3 µM GABA (app. EC10–20) as a result of increasing concentrations of glabridin. We observed that starting at concentrations of 1 µM, there is potentiation of GABA-induced currents, with maximal potentiation achieved at approximately 30 µM (Fig. 1c) and an EC50 of glabridin of 6.30±1.70 µM. We then evaluated the effect of glabridin at this saturating concentration on the dose-response relationship of GABA on α1β2γ2 receptors (Fig. 1d and e). Glabridin led to a strong increase in GABA's potency, as depicted by a leftward shift in the dose-response relationship of GABA on α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors; however, the maximally induced current evoked by 1 mM GABA was not significantly altered (p=0.055, n=4). The EC50 for GABA changed from 20.5±0.8 µM in the absence of glabridin to 1.7±0.2 µM in the presence of 30 µM glabridin (Table 1, Table 2). In the absence of GABA, lower concentrations of glabridin up to 10 µM failed to activate α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors; however, starting with a threshold concentration of 30 µM, elevated concentrations of 100 µM evoked up to 17±7% (n=4) of the maximally evoked current by saturating GABA concentrations (Fig. 1b, d, Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Modulating effect of glabridin on recombinant GABAA receptors. (a) Several components (10 µM) were screened for the potentiation of GABA-induced currents (left, n=3–4). The chemical structure of glabridin (right). (b) Representative voltage-clamp recording of a Xenopus oocyte expressing the α1β2γ2 GABAA subtype exposed to 3 µM GABA in the absence and presence of glabridin 30 µM (left). Higher concentrations of glabridin leads to an activation of the GABAA receptor. (c) Dose-response relationship for the effect of glabridin on GABA induced currents (n of 4–6 oocytes). (d) Co-application of glabridin (30 µM) leads to a leftward shift in the dose-response curve of GABA on α1β2γ2 receptors (n of 4 oocytes). Higher concentrations of glabridin lead to an activation of the GABAA receptor (n of 4 oocytes). (e) Representative voltage-clamp recording of a Xenopus oocyte exposed to increasing concentrations of GABA in the absence (left) and presence (right) of 30 µM glabridin.

Table 1.

Modulation of GABAA receptors subtypes by glabridin.

| Subunit combination | Modulatory EC50 (µM) | GABA ECX (3 µM)a | Fold potentiation by 30 µM glabridin | Direct activation by 30 µM glabridin | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1β2γ2 | 6.30±1.70 | 11.6 | 6.20±1.41 | 0.07±0.02 | P=0.007 |

| α1β2 | 9.63±0.70 | 32.9 | 4.23±0.56 | 0.11±0.05 | P=0.003 |

| α1β1γ2 | 17.23±2.64 | 47.3 | 5.07±1.45 | 0.14±0.08 | P=0.005 |

| α1β3γ2 | 6.83±3.07 | 35.4 | 2.63±0.42 | 0.08±0.04 | P=0.016 |

| α1β2(M286W)γ2 | no potentiation | 11.9 | 1.04±0.05 | 0 | ns |

| α1β2(N265M)γ2 | 32.65±1.52 | 2.8 | 1.4±0.34 | 0 | ns |

(10 µM for the α1β3γ2 combination, 1 µM for the α1β1γ2 combination).

Table 2.

Modulation of GABAA receptors subtypes dose response relationship by glabridin.

| Subunit combination | GABA EC50 (µM) | GABA EC50 (µM) with 30 µM glabridin | Fold decrease | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1β2γ2 | 20.54±0.73 | 1.67±0.12 | 12.3 | P<0.0001 |

| α1β2 | 5.56±0.26 | 3.13±0.37 | 1.8 | ns |

| α1β1γ2 | 2.51±0.24 | 0.57±0.06 | 4.4 | P<0.0001 |

| α1β3γ2 | 4.68±0.72 | 0.69±0.12 | 6.8 | P<0.0001 |

| α1β2(M286W)γ2 | 13.38±2.52 | 17.78±5.57 | 0.75 | ns |

| α1β2(N265M)γ2 | 141.97±37.50 | 40.57±4.29 | 3.5 | P=0.0096 |

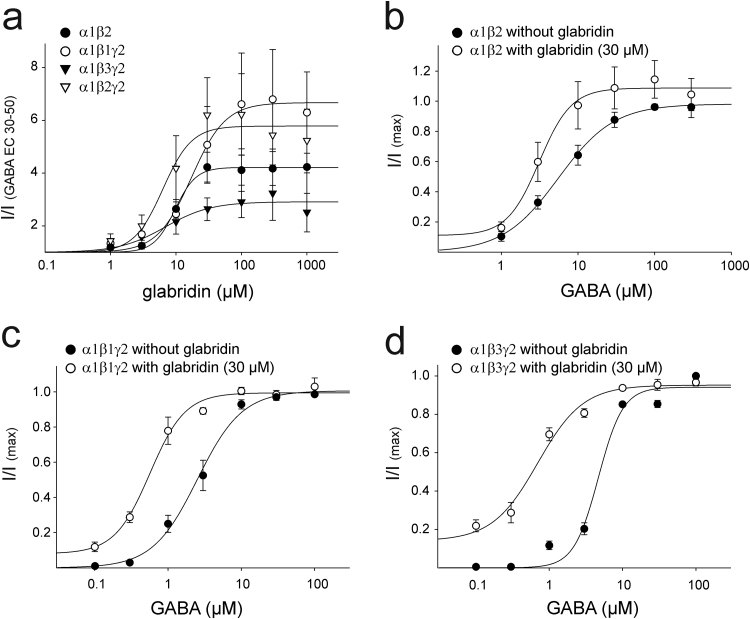

Glabridin is an isoflavonoid. Because other flavonoids have been reported to bind to the benzodiazepine binding site located at the α/γ interface of GABAA receptors, we examined whether glabridin would still present a similar potentiating effect on GABAA receptors lacking the γ subunit. For this, we used a combination of α and β subunits to build a functional α1β2 GABAA receptor. On this receptor type, we observed a significant potentiating effect by glabridin, which presented an EC50 value of 9.63±0.70 µM (Fig. 2a, Table 1). Elevated concentrations of glabridin (30 µM) led to a small direct activation of the receptor (Table 1). Glabridin at a concentration of 30 µM induced a shift in the EC50 for GABA from 5.56±0.26 µM to 3.13±0.37 µM, which is a smaller effect compared to that on the receptor containing the γ2 subunit (Fig. 2a, b and Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Modulation of different recombinant GABAA receptor isoforms by glabridin. (a) Dose-response relationship for the effect of glabridin on GABA induced currents of receptors composed of α1β2, α1β1γ2, α1β3γ2 subunits (n of 4 oocytes). Co-application of glabridin (30 µM) with various concentration of GABA leads to a leftward shift in the dose-response curve of GABA of (b) α1β2 (n of 6 oocytes), (c) α1β1γ2 (n of 4 oocytes) or (d) α1β3γ2 receptors (n of 4 oocytes).

To investigate whether the modulatory effect of glabridin is dependent on the β subunit, we evaluated the effect of this compound on different combinations of GABAA receptors containing different β subunits. Using Xenopus oocytes expressing heteromeric α1β1γ2-and α1β3γ2 GABAA receptors, we observed a strong potentiating effect on the GABA-induced currents (Fig. 2a, Table 1). In both cases, the effect was similar to the potentiation observed on the α1β2γ2 subtype. For these two subtypes, glabridin (30 µM) led to a leftward shift on the dose-response curve to GABA (Table 2). For α1β1γ2, the EC50 shifted from 2.51±0.24 to 0.57±0.06 µM (Fig. 2c), while the α1β3γ2 subtype presented a shift from 4.68±0.72 to 0.69±0.12 µM (Fig. 2d). In addition, for these two subunit combinations, elevated concentrations of glabridin (30 µM) led to a small direct activation of the receptor (Table 1).

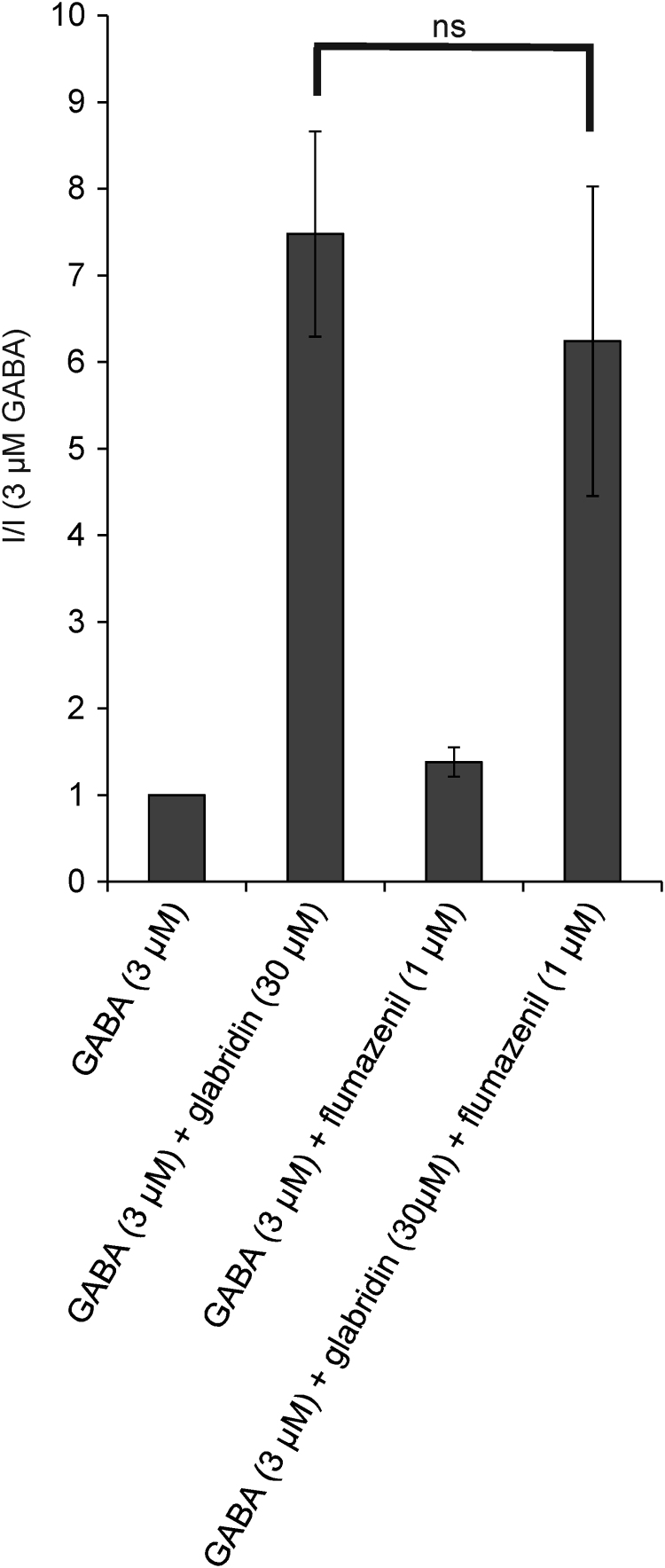

Our results indicate that the γ subunit is not required for the potentiating effect of glabridin, but enhances the potentiating effect on the GABAA receptor. This subunit is known to be involved in the interaction with well-known GABA-modulators, such as benzodiazepines and flavonoids [6]. We tested whether the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil could reduce glabridin potentiation, which would be an indication of the participation of the benzodiazepine binding site. The potentiating action of 30 µM glabridin on the current evoked by 3 µM GABA on α1β2γ2 receptors was not significantly altered by 1 µM flumazenil, an indication that glabridin did not act at the benzodiazepine binding site (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Action of flumazenil on glabridin potentiation. The glabridin potentiation of the current evoked by 3 µM GABA at the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors was not significantly altered by 1 µM of the benzodiazepine inhibitor flumazenil.

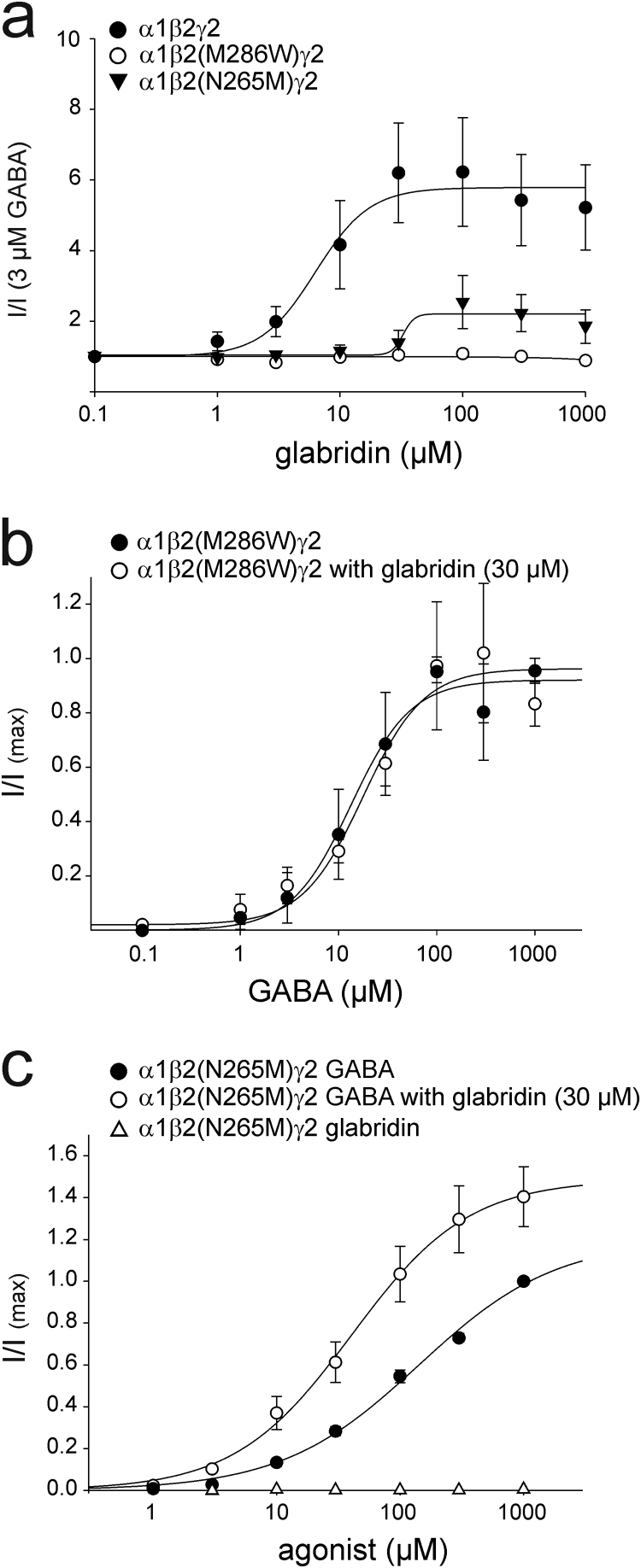

Next, we evaluated the relevance of β subunits for glabridin-induced potentiation. The anesthetics propofol and etomidate are among the strongest GABA potentiators known to interact with the β subunit [5]. We therefore asked whether the asparagine at position 265 or the methionine at position 286, which are known to be involved in the interaction with propofol and etomidate [13], [14], could also be involved in the potentiating mechanism of glabridin. We evaluated the effect of increasing concentrations of glabridin on β2(N265M) and β2(M286W) mutants. In comparison to the α1β2(WT)γ2 mutant, the α1β2(N265M)γ2 mutant presented a marked decrease in its sensitivity towards glabridin as well as in the maximal effect achieved by this compound. Neither a potentiating effect nor any shift in the dose-response curve for GABA could be observed in the β2(M286W) mutant (Fig. 4a, b). The current induced by 3 µM GABA on the β2(N265M) mutant was not significantly potentiated by 30 µM glabridin; however, glabridin induced a small GABA-EC50 shift from 141.97±37.50 µM to 40.57±4.29 µM (Fig. 4c and Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Modulation of mutant GABAA receptors by glabridin. (a) Dose-response relationship for the effect of glabridin on GABA-induced currents on α1β2(M286W)γ2 or α1β2(N265M)γ2 receptors compared to the α1β1γ2 subtype (n of 3–4 oocytes). (b) Co-application of glabridin (30 µM) with various concentrations of GABA did not lead to a shift of the dose response curve for GABA on the α1β2(M286W)γ2 subtype (n of 4 oocytes). (c) Co-application of glabridin (30 µM) leads to a shift in the dose-response curve of GABA on α1β2(N265M)γ2 receptors (n of 3 oocytes).

4. Discussion

GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS). GABAA receptors are a target for the majority of clinically relevant anesthetics and for many neuroleptic, anxiolytic and anticonvulsant drugs [4], [2]. There are many plant-derived flavonoids that act as modulators for GABAA receptors at the CNS level. These are able to induce sedative and anxiolytic effects [6]. We evaluated flavonoids contained in Glycyrrhiza spec. and found that the isoflavonoid glabridin was the only potentiator of the tested substances. However, glabrol, a suggested ligand for the benzodiazepine site of GABAA receptors [8], could not be tested due to its limited availability. Furthermore, previous studies on dorsal raphe neurons indicated that the glabridin potentiates GABA-induced currents [10]. However, until now, there have been no studies about the effect of glabridin on recombinant GABAA receptors. We demonstrated that glabridin has a strong potentiating effect on heterologously expressed GABAA receptors. In α1β2γ2 receptors, 30 µM glabridin reduced the EC50 for GABA 12-fold, with an EC50 of 6 µM for the potentiation effect. This is somewhat higher than the EC50 of 0.7 µM described for the highly effective modulation site in dorsal raphe neurons; however, here, the exact subunit composition of the native GABAA receptor is unknown.

By using mutated receptor subunits and pharmacological tools, we demonstrated that glabridin potentiation is flumazenil insensitive and uses a mechanism that is similar to that used by general anesthetics, such as etomidate, loreclezole, pentobarbital and propofol, involving the amino acids N265 and M286, which are located in the second and the third transmembrane domain on the ß-subunit of GABAA receptors [14], [5]. The β2(M286W) mutation completely abolishes both direct activation and potentiation of glabridin. In addition, the β2(N265M) mutant nearly abolished glabridin potentiation. Glabridin shows a weak preference for receptors containing the β2 or β3 subunit, and the EC50 of glabridin potentiation is higher in β3-containing receptors. This is similar to the anesthetics etomidate and loreclezole, which also potentiate α1β3γ2 and α1β2γ2 subunit combinations better than α1β1γ2 [15]. In terms of potency, glabridin can be compared with propofol, for which EC50 values in the range of 2 µM were reported for the potentiation of α1β2γ2 receptors [16].

Flavonoids have various pharmacological effects that are congruent with their roles as modulators of GABAA receptors. They often act on the benzodiazepine binding site, but other mechanisms have also been proposed [6]. Glabridin is a major flavonoid in G. glabra, and high contents in the dry weight of roots of up to 0.35% were reported [17]. However, the hypnotic effect of G. glabra extracts is flumazenil sensitive and is probably mediated by a mechanism involving the benzodiazepine binding site. It was suggested to be mainly caused by the flavonoid glabrol [8]. Nevertheless, glabridin could contribute to the hypnotic effect, as it is able to cross the blood-brain-barrier [18]. In contrast to potentiators acting on the benzodiazepine site, higher doses of glabridin directly activate GABAA receptors through a different, propofol-like mechanism that could therefore induce sleep like higher doses of barbiturates [19]. Interestingly, Glycyrrhiza extracts also act on the 5HT3A receptor [20], another member of the family of ligand-gated ion channels that is a target for anti-emetic drugs. Here, glabridin is a blocker of the channel, although with a lower potency compared to GABAA receptors.

Our results suggest that glabridin deserves further study as a possible sedative or hypnotic agent.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a grant (SFB 642) from the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) to HH. We would like to thank F. Salami and U. Müller for the assistance provided.

Footnotes

Transparency document associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2016.04.007.

Appendix A. Transparency document

Transparency document

.

Transparency document

.

Transparency document

.

Transparency document

.

Transparency document

.

Transparency document

.

References

- 1.Belelli D., Pistis M., Peters J.A., Lambert J.J. The interaction of general anaesthetics and neurosteroids with GABA(A) and glycine receptors. Neurochem. Int. 1999;34(5):447–452. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen R.W., Sieghart W. GABA A receptors: subtypes provide diversity of function and pharmacology. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(1):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Möhler H. GABA(A) receptor diversity and pharmacology. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326(2):505–516. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudolph U., Möhler H. GABA-based therapeutic approaches: GABAA receptor subtype functions. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2006;6(1):18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen R.W. The molecular mechanism of action of general anesthetics: structural aspects of interactions with GABA(A) receptors. Toxicol. Lett. 1998;100–101:193–201. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(98)00185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanrahan J.R., Chebib M., Johnston, Graham A.R. Flavonoid modulation of GABA(A) receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011;163(2):234–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simmler C., Pauli G.F., Chen S. Phytochemistry and biological properties of glabridin. Fitoterapia. 2013;90:160–184. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho S., Park J., Pae A.N., Han D., Kim D. Hypnotic effects and GABAergic mechanism of licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) ethanol extract and its major flavonoid constituent glabrol. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2012;20(11):3493–3501. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho S., Shimizu M., Lee C.J., Han D., Jung C. Hypnotic effects and binding studies for GABA(A) and 5-HT(2C) receptors of traditional medicinal plants used in Asia for insomnia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;132(1):225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin Z., Kim S., Cho S., Kim I., Han D. Potentiating effect of glabridin on GABAA receptor-mediated responses in dorsal raphe neurons. Planta Med. 2013;79(15):1408–1412. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1350698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sergeeva O.A., Kletke O., Kragler A., Poppek A., Fleischer W. Fragrant dioxane derivatives identify beta1-subunit-containing GABAA receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(31):23985–23993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.103309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gisselmann G., Plonka J., Pusch H., Hatt H. Unusual functional properties of homo- and heteromultimeric histamine-gated chloride channels of Drosophila melanogaster: spontaneous currents and dual gating by GABA and histamine. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;372(1–2):151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krasowski M.D., Koltchine V.V., Rick C.E., Ye Q., Finn S.E. Propofol and other intravenous anesthetics have sites of action on the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor distinct from that for isoflurane. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53(3):530–538. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.3.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegwart R., Krähenbühl K., Lambert S., Rudolph U. Mutational analysis of molecular requirements for the actions of general anaesthetics at the gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor subtype, alpha1beta2gamma2. BMC. Pharmacology. 2003;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wingrove P.B., Wafford K.A., Bain C., Whiting P.J. The modulatory action of loreclezole at the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor is determined by a single amino acid in the beta 2 and beta 3 subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91(10):4569–4573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krasowski M.D., Jenkins A., Flood P., Kung A.Y., Hopfinger A.J. General anesthetic potencies of a series of propofol analogs correlate with potency for potentiation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) current at the GABA(A) receptor but not with lipid solubility. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;297(1):338–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashi H., Hattori S., Inoue K., Khodzhimatov O., Ashurmetov O. Field survey of Glycyrrhiza plants in Central Asia (3). Chemical characterization of G. glabra collected in Uzbekistan. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003;51(11):1338–1340. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu X., Lin S., Zhou Z., Chen X., Liang J. Role of P-glycoprotein in limiting the brain penetration of glabridin, an active isoflavan from the root of Glycyrrhiza glabra. Pharm. Res. 2007;24(9):1668–1690. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigel E., Buhr A. The benzodiazepine binding site of GABAA receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18(11):425–429. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbrechter R., Ziemba P.M., Hoffmann K.M., Hatt H., Werner M. Identification of Glycyrrhiza as the rikkunshito constituent with the highest antagonistic potential on heterologously expressed 5-HT3A receptors due to the action of flavonoids. Front. Pharmacol. 2015;6:130. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document

Transparency document

Transparency document

Transparency document

Transparency document

Transparency document