Abstract

Results of an RCT examining the effects of a brief psychosocial intervention on inpatient satisfaction

Background and Objectives

Increasing attention is being paid to patients’ experience of hospitalization. The brief psychosocial intervention, BATHE, is an intervention found to improve patients’ outpatient experience but not yet studied in inpatient settings. This RCT examined whether daily administration of BATHE would improve patients’ satisfaction with their hospital experience.

Methods

BATHE is a brief psychosocial intervention designed to reduce distress and strengthen the physician-patient relationship. In February-March 2015 and February-March 2016, 25 patients admitted to the University of Virginia Family Medicine inpatient service were randomized to usual care or to the BATHE intervention. Participants completed a baseline measure of satisfaction at enrollment. Those in the intervention group received the BATHE intervention daily for five days or until discharge. At completion, participants completed a patient satisfaction measure.

Results

Daily administration of BATHE had strong effects on patients’ likelihood of endorsing their medical care as “excellent.” BATHE did not improve satisfaction by making patients feel more respected, informed or attended to. Rather, effects on satisfaction were mediated by patients’ perception that their physician showed “a genuine interest in me as a person.”

Conclusions

Our study suggests that patients are more satisfied with their hospitalization experience when physicians take a daily moment to check in with the patient “as a person” and not just as a medical patient. The brevity of the BATHE intervention indicates that this check-in need not be lengthy or overly burdensome for the already busy inpatient physician.

Keywords: hospitalization, patient satisfaction, physician patient relationship

Introduction

Hospitalization is typically a time of acute stress. Patients may be seriously ill and must leave the comfort of their homes to spend time in a disorienting environment. A recent systematic review found that patients’ experiences of hospitalization affect medical outcomes and patient safety.1 Patient experience scores are now publicly reported on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hospital Compare website and are factored into Medicare’s value-based payments.2 While multiple systems affect the inpatient experience, a recent meta-analysis highlighted that the physician-patient relationship affected healthcare outcomes.3

BATHE is a brief, patient-centered intervention designed to address patients’ psychological distress and strengthen the physician-patient relationship.4 The intervention invites the patient to talk about whatever is important to him or her and prompts the physician to express empathy and elicit positive coping. In outpatient settings, BATHE has been found to improve patient satisfaction5,6,7without significantly increasing time spent per office visit7,8 BATHE has also been suggested as a means to improve outcomes for difficult patients.9,10

Given these outpatient findings, BATHE seems a promising approach to improving the inpatient experience. However, BATHE has not been studied in an inpatient setting. This study examined the following hypotheses regarding the effect of BATHE on patients admitted to the University of Virginia Family Medicine inpatient service: 1. The intervention would increase overall patient satisfaction; and 2. Patient perception of physician’s interest in the patient “as a person” would mediate this effect.

Methods

BATHE consists of four questions that elicit descriptions of the patient’s current situation (medical or non-medical) (Table 1).The physician responds with a brief empathic statement, but is not tasked with solving issues raised. Estimates of time needed for the intervention range from 1–2 minutes11 to “less than 5 minutes.”12

Table 1.

BATHE Protocol4

| Component | Physician statements |

|---|---|

| Background | “What is going on in your life?” |

| Affect | “How is that affecting you?” or “How do you feel about that situation?” |

| Troubles | “What troubles you the most about the situation?” |

| Handling | “How have you been handling it so far?” |

| Empathic Statement | “That sounds very scary/frustrating/sad.” |

Participants completed a one-item baseline assessment upon enrollment to control for response bias: “How satisfied are you with the appearance and cleanliness of our facility so far?” At exit, they completed a 20-item survey adapted from RAND Health’s Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire-III, with items rating overall satisfaction, physician interest in them as a person, time spent with physician, interpersonal aspects of care and communication aspects of care.13 The survey was administered by a research assistant unaware of group assignment and uninvolved in patient care.

The University of Virginia Health System Institutional Review Board approved this study. Patients signed a consent form at enrollment.

Results

Study participants were patients admitted to the UVA Family Medicine inpatient service during February-March 2015 and February-March 2016. New adult admissions were offered enrollment unless non-English speaking or cognitively impaired as determined by the primary resident. 25 patients accepted enrollment; 3 patients declined. Although effort was made to offer enrollment to all eligible patients, a few patients were missed due to resident workload.

14 participants were female. Participants ranged from 29–77 years old. They were admitted for various medical diagnoses including pneumonia, pancreatitis, and diabetic complications. Using a computerized random number generator, 12 patients were randomized to usual care and 13 to the intervention group.

Intervention group patients were administered BATHE once daily (until discharge or up to five days) by the primary resident. The nine residents who participated had received training in BATHE, reviewed a refresher module prior to the study, and carried a copy of the BATHE questions. Other medical team members were unaware of patients’ enrollment and group statuses.

Analyses of variance revealed that groups did not differ significantly by age (F (1, 23) = 0.22, p = .65) or gender (χ2 (24) = 1.056 p = .30) (Table 2). Analysis of baseline disposition revealed no group differences at admission, nor was baseline disposition related to outcome satisfaction (Table 3).

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics

| N | Age Mean (s.d.) | Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 12 | 55.8 (14.3) | 4 male; 8 female |

| BATHE | 13 | 53.0 (16.1) | 7 male; 6 female |

| p | – | .65 | .30 |

Note: p value for test of significance of differences between groups is based on an F test (df’s = 1, 24) for age and a χ2 test

Table 3.

Comparison of Intervention and Control Groups at Baseline and Post-Assessment on Overall and Individual Components of Satisfaction.

| Control Mean (s.d.) n=12 | BATHE Mean (s.d.) n=13 | F (1,24) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Assessment | ||||

| Baseline Disposition (“How satisfied are you with the appearance and cleanliness of our facility so far?”) | 4.42 (1.16) | 4.77 (0.60) | 0.93 | 0.354 |

| Outcome Assessments | ||||

| Overall Satisfaction | 3.26 (1.12) | 4.12 (0.63) | 5.58 | 0.027 |

| Individual Satisfaction Items: |

||||

| Very Satisfied with Care | 4.08 (0.67) | 4.69 (0.48) | 6.92 | 0.015 |

| Medical care is excellent | 4.00 (1.13) | 4.77 (0.44) | 5.21 | 0.032 |

| Dissatisfied with some things | 3.33 (1.61) | 1.69 (0.95) | 9.80 | 0.005 |

| Care just about perfect | 3.75 (0.97) | 4.38 (0.77) | 3.34 | 0.081 |

| Some things could be better | 3.42 (1.56) | 2.54 (1.13) | 2.63 | 0.119 |

| Things need to be improved | 3.50 (1.78) | 3.92 (1.55) | 0.75 | 0.396 |

Responses to 5-point Likert-like scale ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree

At exit, participants’ overall satisfaction with hospitalization was significantly higher in the BATHE condition than in the control group (Effect size: d=.866; Table 3). Table 3 presents data on individual items comprising the satisfaction scale. Effects of BATHE on satisfaction were driven most strongly by items reflecting overall satisfaction, as opposed to items specifying that no aspects of the stay needed improvement.

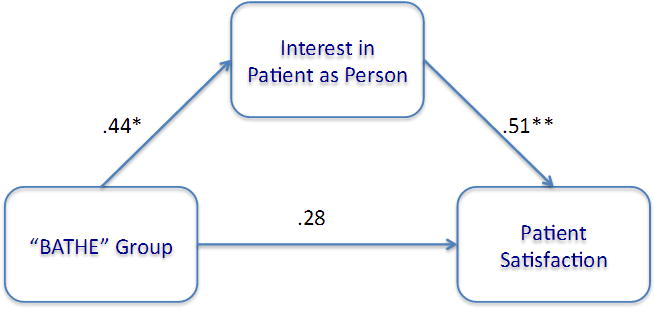

Mediation analyses were consistent with the hypothesis that participants’ perceptions of physician interest in them “as a person” would mediate effects of the intervention on overall patient satisfaction (Figure 1). Follow-up analyses suggested that effects of BATHE were unlikely to be a reflection of patient perception of increased time spent explaining procedures or communication about patient condition, as these did not differ significantly across groups (Table 4).

Figure 1. Perceived Interest in Patient as a Person Mediates Relationship between Intervention and Satisfaction.

Note: ** - p < .01; * - p < .05. Estimates reflect standardized β weights. Estimate for effect of BATHE group on patient satisfaction that did not include the mediated path was: β = .44, p =.027.

Table 4.

Comparison of Intervention and Control Groups on Other Aspects of Patient Experience.

| Outcome Assessment | Control Mean (s.d.) n=12 | BATHE Mean (s.d.) n=13 | F (1,24) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Aspects | 4.08 (0.55) | 4.45 (0.48) | 3.18 | 0.09 |

| Time Spent | 3.83 (0.86) | 4.19 (0.80) | 1.16 | 0.292 |

| Communication | 3.93 (0.77) | 4.29 (0.49) | 1.96 | 0.17 |

Responses to 5-point Likert-like scale ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree

The study was powered to detect a sizeable treatment vs. comparison group difference at exit, controlling for the baseline disposition measure. Assuming a Cohen’s d (effect size) after covariates of 1.0, the study had a power of .82 to detect an effect.

Discussion

Results of this RCT indicate that daily administration of the brief psychosocial intervention, BATHE, had strong effects on patient satisfaction with the inpatient experience and increased the likelihood of patients endorsing their medical care as “excellent.”

Patients in the intervention group were not more likely to perceive that their physician spent adequate time with them, showed them respect, or communicated well about their care. Rather, they were more likely to report that their physician was friendly and showed a “genuine interest in me as a person.” The added value of the intervention appears to have been to create a daily moment where the physician acknowledged the patient as a whole person rather than solely as a medical patient.

The study’s limitations include small sample size, limited outcome measures, and lack of a fidelity measure. Additionally, because the resident administering the study was also in charge of the team, it is possible that his or her awareness of patient group status influenced care and thus patient satisfaction.

These results suggest that patients who feel acknowledged as “persons” and not just as medical patients feel better about their hospitalization experience and medical care. One challenge is that inpatient physicians already feel rushed and overburdened. Future research might investigate whether BATHE adds significantly to time spent by inpatient physicians and whether effects extend to medical outcomes and physician and nurse satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of the UVA Department of Family Medicine and the help of the following colleagues who participated in the project: Theodore Siedlecki, Jr., Ph.D.; Penelope Carter, M.D.; Elizabeth Coleman, M.Ed.; Lucy Guarnera, M.A.; Jonathan Hodges, M.D.; Stephanie Hodges, M.D.; Jeanne Lumpkin, M.D.; Alison Nagel, M.Ed.; Aivi Nguyen-Cao, M.D.; Kim Stein, M.D.; Joseph Tan, M.A.; Jordan Wade, Ph.D.; Mary Whittemore, M.D.; Scott Williams, M.D.; and Catherine Wolcott, Ph.D.

This study and its write-up were partly supported by funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to Joseph P. Allen, Ph.D. (9R01 HD058305–11A1).

Footnotes

Presentations: Early data for the project were presented at the 2015 Forum for Behavioral Science and the 2016 Society of Teachers in Family Medicine Annual Conference.

Conflict Disclosure: no conflicts

Contributor Information

Emma J. Pace, University of Virginia Department of Family Medicine

Nicholas J. Somerville, University of Virginia Department of Family Medicine

Chineme Enyioha, University of Virginia Department of Family Medicine

Joseph P. Allen, University of Virginia Department of Psychology

Latrina C. Lemon, Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Family Medicine and Population Health

Claudia W. Allen, University of Virginia Department of Family Medicine

References

- 1.Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.HCAHPS Fact Sheet. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Baltimore, MD USA: Jun, 2015. http://www.hcahpsonline.org/Facts.aspx. Accessed 8/26/2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelley J, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.00942071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuart M, Lieberman J, Seymour J. The fifteen minute hour: Therapeutic Talk in Primary Care. fourth. London: Radcliffe Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leiblum R, Schnall E, Seehuus M, DeMaria A. To BATHE or not to BATHE: Patient satisfaction with visits to their family physician. Fam Med-Kansas City. 2008;40(6):407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeMaria S, DeMaria A, Weiner M, Silvay G. Use of the BATHE method to increase satisfaction amongst patients undergoing cardiac and major vascular operations. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77(Electronic Suppl 1):eS25–eS25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeMaria S, DeMaria A, Silvay G, Flynn B. Use of the BATHE method in the preanesthetic clinic visit. Anesth Analg. 2011;113(5):1020–1026. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318229497b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J, Park YN, Park EW, Cheong YS, Choi EY. Effects of BATHE interview protocol on patient satisfaction. Korean J Fam Med. 2012;33(6):366–371. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2012.33.6.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Essary AC, Symington SL. How to make the “difficult” patient encounter less difficult. J Am Acad Physician Assistants. 2005;18(5):49–54. doi: 10.1097/01720610-200505000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCulloch J, Ramesar S, Peterson H. Psychotherapy in primary care: The BATHE technique. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(9):2131–2134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieberman JA, 3rd, Stuart MR. The BATHE method: Incorporating counseling and psychotherapy into the everyday management of patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1(2):35–38. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v01n0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Searight R. Realistic approaches to counseling in the office setting. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(4):277–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire III. RAND Health. 1993 Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/www/external/health/surveys_tools/psq/psq3_survey.pdf. Accessed 12/1/2014.