Abstract

Purpose of review

The current systematic review sought to compare available evidence-based clinical treatment guidelines for all specific eating disorders.

Recent findings

Nine evidence-based clinical treatment guidelines for eating disorders were located through a systematic search. The international comparison demonstrated notable commonalities and differences among these current clinical guidelines.

Summary

Evidence-based clinical guidelines represent an important step toward the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based treatments into clinical practice. Despite advances in clinical research on eating disorders, a growing body of literature demonstrates that individuals with eating disorders often do not receive an evidence-based treatment for their disorder. Regarding the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based treatments, current guidelines do endorse the main empirically validated treatment approaches with considerable agreement, but additional recommendations are largely inconsistent. An increased evidence base is critical in offering clinically useful and reliable guidance for the treatment of eating disorders. Because developing and updating clinical guidelines is time-consuming and complex, an international coordination of guideline development, for example, across the European Union, would be desirable.

Keywords: eating disorders, evidence-based, guideline, therapy, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge-eating disorder (BED) represent the specific eating disorders defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5 [1]). They are characterized – at varying degrees – by persistent disturbances in eating or weight-control behavior and shape and weight overconcern. The central characteristic of AN is a significantly low body weight, induced by restriction of energy intake. The main features of BN and BED are recurrent binge-eating episodes. Although individuals with BN usually attempt to prevent weight gain through inappropriate compensatory behaviors (e.g., self-induced vomiting), those with BED do not make recurrent use of them. All eating disorders result in significant impairments in health, psychosocial functioning, and quality of life [2,3]. Increased healthcare utilization and costs have been documented [4▪,5]. With a first onset that often occurs in adolescence or young adulthood [6], AN and BN show a long-term natural course with remission in more than 50% of cases, whereas evidence on the natural course of BED is scarce [7]. While AN occurs in up to 4% of young women [7,8▪], BN and BED have a lifetime prevalence of 1.0 and 1.9%, respectively [9].

Given the clinical significance of eating disorder symptomatology, over the past decades sustained effort has been placed on designing and evaluating psychological and medical treatments for eating disorders in rigorous, randomized-controlled efficacy studies [10▪▪,11–14]. Despite these advances, a growing body of literature demonstrates that individuals with eating disorders often do not receive an evidence-based treatment for their disorder [15▪▪,16]. For example, Kessler et al.[9] documented in 24 124 adults from 14 countries that only 47.4% of lifetime cases with BN and 38.3% of lifetime cases with BED ever received a specific treatment for their eating disorder. In a study among 5 658 women 40–50 years old from the United Kingdom, only 27.4% of all women with a DSM-5 life-time diagnosis of an eating disorder had sought help or received treatment for an eating disorder at any point in their life [17▪]. Multiple system factors (e.g., lack of screening for eating disorders) and personal patient factors (e.g., lack of information) may account for this ‘treatment gap’ [15▪▪,18▪,19▪]. In addition, a ‘research-practice gap,’ indicating a discrepancy between evidence-based treatments and actual treatment delivery, was identified: As an example, the majority of eating disorder therapists do not adhere to evidence-based treatment protocols but rather pursue eclectic combinations of interventions [20,21,22▪]; findings such as this highlight the significant challenge of disseminating and implementing of evidence-based eating disorder treatments into clinical practice [15▪▪,23,24].

As a first step toward the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based treatments into clinical practice, evidence-based clinical guidelines for eating disorders were issued in several countries across the world. Their general aim is to inform clinical decision-making of healthcare professionals and patients on efficacious interventions and treatment strategies. Based on a systematic search, selection, and evaluation of the treatment literature, evidence-based treatment guidelines offer specific recommendations to optimize patient care [25–27]. In one narrative review, Herpertz-Dahlmann et al.[28] compared several evidence-based clinical guidelines from four European countries (Germany, Spain, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) regarding the treatment of AN. They found correspondence in major recommendations, but no consensus on treatment intensity/setting, as well as no consensus and lack of evidence on nutritional rehabilitation and weight restoration. The authors identified a need for European research initiatives on AN to enhance the evidence base and clinical guidance. Since this report, several new guidelines were issued (e.g., The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Australia); however, current comparative information is lacking, especially for BN and BED. This systematic review sought to compare the available evidence-based clinical treatment guidelines for all specific eating disorders to investigate the necessity of future work on guidelines for translation into practice.

Box 1.

no caption available

METHOD

Guideline identification

In May 2017, we systematically searched the electronic databases PubMed and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [‘guideline AND (eating disorder OR anorexia nervosa OR bulimia nervosa OR binge-eating disorder)’]; the National Guideline Clearinghouse and the International Guideline Library (‘eating disorder OR anorexia nervosa OR bulimia nervosa OR binge-eating disorder’); the website of the Academy of Eating Disorders through which partners and affiliate organizations were obtained and contacted; and contacted other experts in the field. Relevant clinical guidelines were required to be evidence-based; the latest version; address the treatment of AN, BN, and/or BED; have a focus on adults; to be published in Dutch, English, or German; and have a national or international scope.

Assessments and analysis

To compare the content of the guidelines, key recommendations were summarized regarding predefined categories. For AN, BN, and BED, these categories included: first-line treatment setting, criteria for hospitalization, recommended treatment modalities including nutritional counseling, specific psychological interventions, and medications. For the treatment of AN, guidelines were additionally compared with respect to the following categories: compulsory treatment, criteria for partial hospitalization, criteria for discharge, recommended energy intake and weight gain, feeding supplements, and artificial feeding.

Included guidelines were independently examined by two authors. Relevant content was extracted into a predefined coding table using the guidelines’ original text by one author with corrections from the second author. For comparative purposes, it was noted whether a recommendation was given (✓) or not reported, and if possible, the guidelines’ recommendations were recoded into three ratings: explicit recommendation in favor (+), recommendation requiring caution [(+)], and recommendation against (−). In addition, and if recoding was not possible, the guidelines’ recommendations were reported in text format.

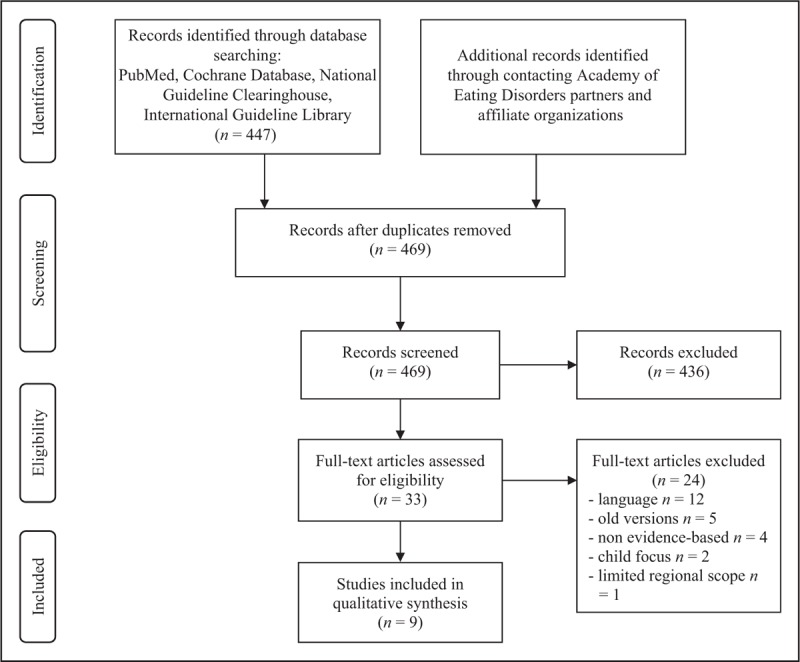

RESULTS

A total of 33 guidelines were identified, as depicted in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1). Most guidelines had to be excluded for not meeting the language criterion (n = 12). In addition, five guidelines were earlier versions of included guidelines, four guidelines were non-evidence-based, two guidelines solely focused on childhood eating disorders, and one guideline had a regional scope. Accordingly, nine guidelines from eight countries, published between 2009 and 2017, were included in this report.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram: international comparison of evidence-based clinical guidelines for eating disorders (15 June 2017).

Most guidelines (n = 7) included treatment recommendations for AN, BN, and BED: these were the guidelines from Australia and New Zealand [29], Germany [30], The Netherlands [31], Spain [32], the United Kingdom [33], the United States [34,35], and the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP; [36]). The guideline from Denmark [37,38] addressed the treatment of AN and BN, while the French guideline [39] focused on AN only. All guidelines are described in Table 1. The guideline by the WFSBP provided recommendations for medical treatment of eating disorders only, whereas all other guidelines addressed several treatment approaches. The majority of guidelines were developed by multiprofessional working groups (Australia and New Zealand, France, Germany, The Netherlands, Spain, the United Kingdom), while both the United States and WFSBP guidelines were developed by psychiatric groups. Regarding the modernity of the guidelines, three guidelines were published within the last 3 years (Australia and New Zealand, Denmark, the United Kingdom) or are currently being published (The Netherlands), while the remainder were published at least 5 years ago (France, Germany, Spain, the United States, WFSBP).

Table 1.

Evidence-based clinical guidelines for eating disorders published between 2009 and 2017

| Abbreviations | Full guideline name | Year | Country | Status | Scientific society | Targeta | Preparing committeeb | Eating disordersc |

| AUS | Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders [29] | 2014 | Australia and New Zealand | Active | Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists | Specialists | Multidisciplinary group of healthcare academics and professionals, consultation with key stakeholders and the community | AN, BN, BED |

| DEN | National clinical guideline for the treatment of anorexia nervosa – quick guide [37] National clinical guideline for the treatment of moderate and severe bulimia – quick guide [38] | 2016 | Denmark | Active | Danish Health Authority | Specialists | NR | AN, BN |

| FR | Clinical practice guidelines anorexia nervosa: management [39] | 2010 | France | Active | Association Française pour le Développement des Approches Spécialisées des Troubles du Comportement Alimentaire, Fédération Française de Psychiatrie, Haute Autorité de la Santé | Specialists | Multidisciplinary group | AN |

| GER | S3-guideline for the assessment and therapy of eating disorders [30] | 2010 | Germany | In revision | Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF) | Specialists | Multidisciplinary group of clinicians and researchers with expertise in the field of eating disorders | AN, BN, BED |

| NETH | Practice guideline for the treatment of eating disorders [31] | 2017 | The Netherlands | To be published | Dutch Foundation for Quality Development in Mental Healthcare | Population and specialists | Multidisciplinary group of healthcare professionals, health insurance representatives, patients and relatives | AN, BN, BED |

| SP | Clinical practice guideline for eating disorders [32] | 2009 | Spain | Active | Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Research, Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs | Population and specialists | Multidisciplinary group of professionals involved in the field of eating disorders and experts on Clinical Practice Guidelines’ methodology | AN, BN, BED |

| UK | Eating disorders: recognition and treatment, full guideline [33] | 2017 | United Kingdom | Active | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence | Specialists | Multidisciplinary group comprised of healthcare professionals, researchers and lay members | AN, BN, BED |

| US | Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders, third edition, Guideline watch (August 2012) [34,35] | 2010, 2012 | United States | Active, guideline watch | American Psychiatric Association | Specialists | Psychiatrists in active clinical practice and some who are primarily involved in research or other academic endeavors | AN, BN, BED |

| WFSBP | World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of eating disorders [36] | 2011 | - | Active | World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry | Specialists | Psychiatrists of WFSBP task force on eating disorders | AN, BN, BED |

aItalicized words indicate that the information was inferred from the text, where explicit information from the guideline was lacking.

bNot reported.

cAN, anorexia nervosa; BN, bulimia nervosa; BED, binge-eating disorder.

Comparison

The comparative results for AN, BN, and BED are summarized in Tables 2–4.

Table 2.

Comparison of evidence-based clinical guidelines for anorexia nervosa regarding key recommendations

| Clinical guideline | |||||||||

| Recommendation | AUS | DEN | FR | GER | NETH | SP | UK | US | WFSBP |

| Treatment setting | |||||||||

| First-line treatment: outpatient | + | N.R. | + | + | + | + | + | + | N.R. |

| Criteria for day hospital treatment | N.R. | N.R. | ✓ | ✓ | N.R. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N.R. |

| Criteria for hospitalization | ✓ | N.R. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N.R. |

| Criteria for discharge | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N.R. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N.R. |

| Information on compulsory treatment | N.R. | N.R. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N.R. |

| Treatment modalities | |||||||||

| Refeeding/nutritiona | |||||||||

| Recommended energy intake, per day | Start at 6000 kJ (1433 kcal), increases of 2000 kJ (478 kcal) every 2–3 days until adequate intake for weight restoration | N.R. | N.R. | Start at 30–40 kcal/kg for severely underweight patients, 800–1200 kcal supplementary intake/day necessary for 100 g weight gain/day | Start at 40–60 kcal/kg for severely underweight patients, 800–1100 kcal supplementary intake/day necessary | 25–30 kcal/kg or total kcal <1000 for severe malnutrition, day hospital: supplementary intake of 300–1000 kcal | Inpatient settingsb: sometimes lower starting intakes (e.g., 5–10 kcal/kg) for severely underweight patients, stepwise increase to 20 kcal/kg within 2 days, about 3500–7000 extra calories/week | Start at 30–40 kcal/kg (i.e., 1000–1600 kcal), weight gain phase: up to 70–100 kcal/kg, male patients with higher energy need | N.R. |

| Recommended weight gain per week, inpatient settings | 0.5–1.4 kg | N.R. | 0.5–1 kg | 0.5–1 kg | 0.5–1.5 kg | 0.5–1 kg | N.R. | 0.9–1.4 kg | N.R. |

| Recommended weight gain per week, outpatient settings | N.R. | N.R. | 0.25 kg | 0.2–0.5 kg | 0.25–0.5 kg | N.R. | N.R. | 0.2–0.5 kg | N.R. |

| Recommended supplements | (+) Phosphate, thiamine (risk of refeeding syndrome) | N.R. | (+) Phosphate, vitamin and trace elements (risk of refeeding syndrome) | (+) Zinc (skin lesions), potassium chloride (cardiac arrhythmia), iron (iron-deficiency anemia), thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, folic acid, phosphate | (+) Phosphate, thiamine (risk of refeeding syndrome) | (+) Oral multivitamin and/or mineral supplements | (+) Multivitamin and multimineral supplements, biphosphonates | (+) Phosphate, magnesium, potassium, calcium, vitamin D, zinc | N.R. |

| Recommendations for artificial feeding | ✓ | N.R. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Nutritional counseling | N.R. | N.R. | + | (+) Only in multidisciplinary therapy approach | + | + | (+) Only in multidisciplinary therapy approach | (+) Registered dieticians | N.R. |

| Psychological interventions | |||||||||

| In general | + (More intense when medically stabilized and cognitively improved from starvation) | + | Cannot treat severe AN alone, but in conjunction with refeeding | + | When medically stabilized and cognitively sufficiently recovered from malnutrition | N.R. | N.R. | Formal psychotherapy with starving patients may be ineffective | N.R. |

| CBT | +c | N.R. | + | N.R. | + (First) | + | + (First) | + (After weight restoration) | N.R. |

| FBT | +c | +c | +c | N.R. | +c | +c | +c | +c | N.R. |

| Psychodynamic therapy | N.R. | N.R. | + | N.R. | N.R | + | + | + (Acute AN and after weight restoration) | N.R. |

| IPT | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | + | N.R. | + (After weight restoration) | N.R. |

| Other | Specialist therapist-led manualized based approaches (first), adolescent focused therapy | N.R. | Support therapies, systemic and strategic therapies, motivational approaches, nonverbal approaches in conjunction | N.R. | MANTRA (first), SSCM (first) | Behavioral therapy | MANTRA (first), SSCM (first) | + Nonverbal therapeutic methods (chronic AN), group psychotherapy for adults (after weight restoration) | N.R. |

| Medication | |||||||||

| In general | N.R. | N.R. | (No specific medication to treat AN) | N.R. | N.R. | Not as only primary treatment | Not as sole treatment | N.R. | N.R. |

| Antidepressants | (+)c | N.R. | + Depressive disorders, anxious disorders, OCD | − Weight gain+ depressive symptoms | N.R. | N.R | N.R. | + Depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive symptoms, or bulimic symptoms | N.R. |

| SSRIs | –c | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | – | N.R. | N.R. | − Weight gain+ depressive, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, or bulimic symptoms (in combination with psychotherapy or after weight restoration) | N.R. |

| TCAs | N.R. | N.R. | (+) | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | – | N.R. |

| MAOIs | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | – | N.R. |

| Antipsychotics | (+) Obsessional thinking (olanzapine) | N.R. | (+) | − Weight gain(+)Obsessional thinking (only short-term) | (+) Obsessional thinking (olanzapine) | N.R. | N.R. | (+) Weight gain(+) Obsessional thinking (olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, chlorpromazine) | N.R. |

| Appetizers | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | – | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| Lithium | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | – | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| Estrogen | N.R. | N.R. | (+) | N.R. | N.R. | (+) | (+) | (+) | N.R. |

| Other medication | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | + Pro-motility agents− Buproprion(+) Antianxiety agents | N.R. |

| Other treatments | N.R. | + Meal support/eating training (as adjunct)+ Supervised physical activity (as adjunct during weight gain phase) | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | − Physical therapy (transcranial magnetic stimulation, acupuncture, weight training, yoga or warming therapy) | − Electroconvulsive therapy (or only for severe cooccuring disorders) | N.R. |

| Special issues | Separate recommendations for children and adolescents and for severe and long-standing AN, refeeding syndrome, medical management | Weighing, pregnancy, medical management | Detailed information on artificial feeding, different settings of care, weighing, specific recommendations for treatment of core symptoms | Separate recommendations for children and adolescents and for severe and long-standing AN, progress monitoring, relapse prevention | Treatment of comorbidities, pregnancy, medical management | Separate recommendations for children and adolescents, detailed information on psychotherapies, carer support, weighing, medical management, treatment of comorbidities, pregnancy | Recommendations for acute AN versus after weight restoration versus chronic AN, refeeding syndrome | ||

Note: ✓ recommendation given; + explicit recommendation in favor; (+) cautious recommendation in favor; − recommendation against; N.R., no recommendation reported; AUS, Australia and New Zealand; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; DEN, Denmark; FBT, family-based therapy; FR, France; GER, Germany; IPT, interpersonal therapy; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; MANTRA, Maudsley Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults; NETH, The Netherlands; SSCM, Specialist Supportive Clinical Management; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SP, Spain; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; WFSBP, World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry.

aRecommendations for weight gain and energy intake were derived from both the guideline's text and recommendations.

bInformation on energy intake for the UK guideline was obtained from the Management of Really Sick Patients with Anorexia Nervosa (MARSIPAN) guideline, because the UK guideline refers to it in this respect

cIndicates that the recommended intervention refers to children and adolescents only.

Table 4.

Comparison of evidence-based clinical guidelines for binge-eating disorder regarding key recommendations

| Clinical guideline | |||||||

| AUS | GER | NETH | SP | UK | US | WFSBP | |

| Treatment setting | |||||||

| First-line treatment: outpatient | N.R. | + | + | N.R. | + | N.R. | N.R. |

| Criteria for inpatient treatment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N.R. | ✓ | N.R. | N.R. |

| Treatment modalities | |||||||

| Nutritional counseling | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | (+) (With approval of psychiatrist) | N.R. | + (In the context of behavioral weight-control programs) | N.R. |

| Psychological interventions | |||||||

| In general | + (Individual) | + | + | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| CBT | + (First) | + (First) | + (First, individual or group) | + | + (Group or individual) | + (First, individual or group) | N.R. |

| FBT | N.R. | N.R. | +a | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| Self-help | + (Guided, CBT) | + (Guided, CBT) | + (Guided, CBT) | + (Guided or unguided) | + (First, guided, CBT) | + (Guided or unguided, CBT) | N.R. |

| Psychodynamic therapies | N.R. | + | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| IPT | N.R. | + | + | + | N.R. | + | N.R. |

| Medications | |||||||

| In general | + (If psychotherapy is not available or as adjunctive therapy) | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | Not as sole treatment | N.R. | N.R. |

| Antidepressants | + | N.R. | N.R. | + | N.R. | + | N.R. |

| SSRI | + | + (Off-label-use, short-term) | + Binge eating frequency | + Binge eating frequency | N.R. | + Binge eating frequency (short-term) | + (Citalopram/escitalopram, sertraline) |

| TCAs | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | + (Imipramine) |

| Anticonvulsants | + (Topiramate) | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | + (Topiramate, zonisamide) | + (Topiramate) |

| Antiobesity medications | + Weight loss (orlistat) | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | + Binge-eating frequency (sibutramine, short-term) + Weight loss (orlistat, sibutramine) | N.R. |

| Other treatments | + Combined psychological and pharmacological therapy | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | − Physical therapy (transcranial magnetic stimulation, acupuncture, weight training, yoga or warming therapy) | + Behavioral weight-control programs + Orlistat plus guided self-help CBT + Fluoxetine plus group behavioral treatment | N.R. |

| Special issues | Medical management | No long-term evidence for pharmacological treatment | Treatment of comorbidities, options for weight loss | Treatment of comorbidities, pregnancy | Detailed information on psychotherapies, medical management, treatment of comorbidities, pregnancy | No long-term evidence | |

Note: ✓ recommendation given; + explicit recommendation in favor; (+) cautious recommendation in favor; − recommendation against; AUS, Australia and New Zealand; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; FBT, family-based therapy; GER, Germany; IPT, interpersonal therapy; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; N.R., no recommendation reported; NETH, The Netherlands; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SP, Spain; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; WFSBP, World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry.

aIndicates that the recommended intervention refers to children and adolescents only.

Table 3.

Comparison of evidence-based clinical guidelines for bulimia nervosa regarding key recommendations

| Clinical guideline | ||||||||

| AUS | DEN | GER | NETH | SP | UK | US | WFSBP | |

| Treatment setting | ||||||||

| First-line treatment: outpatient | + | N.R. | + | N.R. | + | + | + | N.R. |

| Criteria for day hospital treatment | ✓ | N.R. | ✓ | N.R. | N.R. | ✓ | ✓ | N.R. |

| Criteria for inpatient treatment | ✓ | N.R. | ✓ | N.R. | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N.R. |

| Treatment modalities | ||||||||

| Nutritional counseling | N.R. | + (Individualized or standardized) | N.R. | N.R. | (+) Only with psychiatrist's approval | N.R. | + (As part of the treatment) | N.R. |

| Psychological interventions | ||||||||

| In general | + (Individual) | N.R. | + | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| CBT | + (First) | + (First, individual or group) | + (First) | + (First, individual or group) | + | + (Individual) | + (First) | N.R. |

| FBT | N.R. | +a | N.R. | +a | N.R. | +a | + | N.R. |

| Self-help | + (Guided, CBT) | N.R. | + (Guided, CBT) | + (Guided, CBT) | + | + (First, guided, CBT) | + | N.R. |

| Psychodynamic therapies | N.R. | N.R. | + | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | + | N.R. |

| IPT | N.R. | N.R. | + | + | + | N.R. | + | N.R. |

| Other | + Internet-based CBT | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | + Group psychotherapy + Psychodynamic interventions and CBT and other psychotherapies + Couples therapy + Support groups (as adjunct) | N.R. |

| Medications | ||||||||

| In general | + (If psychotherapy is not available or as adjunctive therapy) | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | Pharmacological treatments other than antidepressants are not recommended | Not as sole treatment | N.R. | N.R. |

| Antidepressants | + | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | + | N.R. | + | N.R. |

| SSRIs | + (Fluoxetine) | (+) | + (Fluoxetine, in combination with psychotherapy) | + (Fluoxetine) | + (Fluoxetine) | N.R. | + (Fluoxetine) | + (Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine) |

| TCAs | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | − | + (Imipramine, desipramine) |

| MAOIs | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | − | − (Phenelzine) |

| Anticonvulsants | + (Topiramate) | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | (+) (Topiramate) | N.R. |

| Lithium | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | − | N.R. |

| Other | + Weight loss (orlistat) | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. |

| Other treatments | + Combined psychological and pharmacological therapy | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | N.R. | − Physical therapy (transcranial magnetic stimulation, acupuncture, weight training, yoga or warming therapy) | + Combined treatment of CBT and antidepressants + Bright light therapy (as adjunct) | N.R. |

| Special issues | Medical management | Treatment of comorbidities | Treatment of comorbidities, options for weight loss | Treatment of comorbidities, pregnancy, medical management | Separate recommendations for children and adolescent with BN, detailed information on psychotherapies, carer support, medical management, treatment of comorbidities, pregnancy | Recommendations for initial versus maintenance phase | No long-term evidence | |

Note: ✓ recommendation given; + explicit recommendation in favor; (+) cautious recommendation in favor; − recommendation against; AUS, Australia and New Zealand; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; DEN, Denmark; FBT, family-based therapy; GER, Germany; IPT, interpersonal therapy; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; N.R., no recommendation reported; NETH, The Netherlands; SP, Spain; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; WFSBP, World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry.

aIndicates that the recommended intervention refers to children and adolescents only.

Anorexia nervosa

All guidelines which provided information on the treatment setting (n = 7) consistently recommended outpatient treatment as a first-line therapy setting for patients with AN. For determining more intense levels of care, most guidelines provided criteria for partial (n = 5) and full-time hospitalization (n = 7). The degree of detail and range of hospitalization criteria varied between guidelines. However, the guidelines consistently emphasized the necessity to decide about hospitalization on an individual basis taking multiple factors into account. Overall, hospitalization should be considered for patients who have failed at outpatient care, or who are at high risk for medical complications as determined using patient's weight status (e.g., extremely low body mass index), behavioral factors (e.g., decline in oral intake), vital signs (e.g., heart rate < 40 bpm), psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., suicide risk), or environmental aspects (e.g., family support). For very malnourished patients who do not consent to treatment, most guidelines provided some information on compulsory treatment (n = 7). Criteria for discharge from hospital were specified by the majority of guidelines (n = 7).

The majority of guidelines (n = 6) emphasized the importance to treat patients with AN and eating disorders in general, respectively, by specialized professionals and/or by professionals with substantial experience in the treatment of eating disorders. Regarding specific treatment modalities, most guidelines included recommendations for nutritional management ranging from artificial feeding (n = 8) to general nutritional counseling (n = 6). Although the extent to which information on artificial feeding was given differed among guidelines (e.g., concerning refeeding practice, duration, or indication), guidelines consistently favored oral enteral nutrition over parenteral nutrition which should only be used as a last option. Regarding general nutritional counseling, two (Germany, the United Kingdom) of six guidelines explicitly stated that it should be part of a multidisciplinary therapy approach and not used as a stand-alone treatment. Although there was substantial agreement across guidelines about the amount of recommended weight gain per week in inpatient and outpatient settings, mostly ranging between 0.5–1.5 and 0.2–0.5 kg, respectively, variation in the amount of recommended energy intake per week was apparent. Although some guidelines recommended daily energy intakes of 30–40 kcal/kg (Germany, the United States) or higher (The Netherlands), others recommended considerably lower intakes (Spain, the United Kingdom), particularly for severely malnourished patients at risk for refeeding syndrome. Among the seven guidelines which specified the use of nutritional supplements, there was a large variation of recommendations regarding the type and indication for nutritional supplements. Some guidelines specifically recommended phosphate (n = 6), thiamine (n = 3), zinc (n = 2), or potassium (n = 2), if indicated, while others made a general recommendation for mineral or vitamin supplements (n = 3).

Although psychotherapy was deemed a central part of treatment by all guidelines, only seven guidelines recommended specific psychological interventions. All seven guidelines recommended family-based therapy (for greater detail, see Herpertz-Dahlmann in this issue [40,41]), particularly for younger patients. For individual psychotherapy, most guidelines recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy (n = 6) which intervenes at the symptom level and centers on the modification of dysfunctional behaviors and cognitions that maintain the disorder [42]. It was recommended as a first-line psychotherapy for AN by two guidelines (The Netherlands, the United Kingdom). Lesser agreement was achieved for psychodynamic therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy, which were explicitly recommended as an alternative by four and two guidelines, respectively. While psychodynamic therapy includes treatments that operate on an interpretative-supportive continuum [43], interpersonal psychotherapy is a focused, goal-oriented treatment which seeks to treat an eating disorder through resolving interpersonal problems in the context of what the disorder presents [44,45]. Further, the cognitive-interpersonal approach Maudsley Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults [46] and the Specialist Supportive Clinical Management [47,48] were recommended as first-line therapies by two guidelines (The Netherlands, the United Kingdom). Although the German guideline only made a general recommendation for psychological interventions, it recommended involving the patient's family in the treatment of children and adolescents. Some guidelines noted that psychological interventions would be more effective in medically stabilized and cognitively improved patients (n = 3) or through combining psychological and nutritional interventions (n = 1).

Regarding the pharmacological treatment of AN, five of nine guidelines provided specific recommendations with some notable variations. Two guidelines made the general recommendation that medication should not be used as the sole or primary treatment for patients with AN (Spain, the United Kingdom) or that there is no specific medication to treat AN (France). Antidepressants were generally recommended for those with depressive symptoms by four guidelines. At the same time, the German guideline cautioned against the use of antidepressants for weight gain. For selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), there was one guideline which recommended its use for treating depressive symptoms in conjunction with psychotherapy or after weight restoration (the United States), while two other guidelines made general recommendations against their use, particularly in children and adolescents (Australia and New Zealand, The Netherlands). The use of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) was not explicitly favored, given that there was one recommendation against (the United States) and one cautious recommendation in favor (France). The use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) or bupropion, an atypical antidepressant, was not recommended by the guideline from the United States, the only guideline reporting on these medications. Four guidelines consistently recommended the cautious use of antipsychotics for treating obsessional thinking in patients with AN, particularly olanzapine, because evidence from randomized-controlled trials and regarding long-term effects were lacking. Conflicting results were found for weight gain, given that one guideline recommended antipsychotics for weight gain (the United States), whereas another guideline stated that antipsychotics would not be appropriate for weight gain (Germany). Promotility agents and antianxiety agents were only recommended by the guideline from the United States for treating gastrointestinal problems and to reduce anticipatory anxiety concerning food intake, respectively. The use of appetizers and lithium was not recommended by the German guideline. In addition, four guidelines consistently stated that estrogen should not be routinely offered to patients with AN, as this would depend on the patient's menarche status or chronicity of AN, for example.

Adjunctive treatment recommendations were rarely made and included meal support, eating training, and supervised physical activity, as described by the Danish guideline. Physical therapies (e.g., electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation) were not recommended by two guidelines. Of note, four guidelines included information on the medical management of AN and three guidelines additionally reported on pregnancy and pregnancy attempts. Two guidelines specifically provided information about the treatment of physical and mental comorbidities, as well as artificial feeding including refeeding syndrome.

Bulimia nervosa

Among the guidelines reporting on the prioritized treatment setting of BN, all recommended outpatient therapy as a first-line treatment (n = 5). Four and five guidelines provided criteria for partial and full-time hospitalization, respectively. Regarding specific treatment modalities, nutritional counseling was generally recommended by the Danish guideline, in individualized or standardized format, while two other guidelines emphasized that nutritional interventions (e.g., to help develop a structured meal plan) should not be offered as stand-alone therapy (Spain, the United States).

Other than the WFSBP guideline, all available guidelines issued recommendations on specific psychological interventions. In agreement, five guidelines recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy as a first-line psychotherapy for patients with BN, particularly in an individual format. The remaining two guidelines also made recommendations in favor of cognitive-behavioral interventions, but prioritized cognitive-behavioral, guided self-help treatment as a first-line treatment (the United Kingdom), or did not provide an explicit treatment hierarchy (Spain). Overall, among the six guidelines which recommended self-help approaches, four highlighted the use of guided self-help based on cognitive-behavioral interventions (Australia and New Zealand, Germany, The Netherlands, the United Kingdom), that is, using structured self-help manuals supplemented with brief supportive sessions [49]. Interpersonal psychotherapy was recommended as an alternative to cognitive-behavioral therapy by most guidelines (n = 4), while psychodynamic therapy (n = 2) was rarely recommended. Family-based therapy was in particular recommended for younger patients with BN (n = 4), and only explicitly recommended for adults by the guideline from the United States. Although the German guideline recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents with BN, they emphasized the importance of including the patient's family into treatment. Alternative psychological interventions were, for example, the combination of psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral therapies (n = 1), couples therapy (n = 1), or support groups (n = 1).

Among the recommendations for pharmacological treatment, seven out of eight guidelines consistently recommended antidepressants, specifically the SSRI fluoxetine, although with some restrictions (e.g., to use antidepressants in combination with psychotherapy). Conflicting recommendations were obtained for the use of TCAs such as imipramine and desipramine, which were recommended by the WFSBP, while the guideline from the United States explicitly did not recommend TCAs for initial treatment in patients with BN. Consistently, two guidelines advised against the use of MAOIs (United States, WFSBP). The use of anticonvulsants, specifically topiramate, was consistently recommended by two guidelines, while the remaining guidelines did not report on anticonvulsants. The only guideline which made a recommendation about lithium cautioned against its use (the United States). For patients with comorbid obesity, one guideline recommended the antiobesity medication orlistat (Australia and New Zealand).

Of note, four guidelines included specific information about the treatment of comorbidities, and three guidelines made recommendations for the medical management of BN.

Binge-eating disorder

Only three out of seven available guidelines explicitly included the recommendation that outpatient treatment is the first-line treatment setting for BED (Germany, The Netherlands, the United Kingdom). Criteria for hospitalization were provided by four guidelines (Australia and New Zealand, Germany, The Netherlands, the United Kingdom). An explicit recommendation for nutritional counseling was made by the guideline from the United States, specifically within the context of behavioral weight loss programs. The Spanish guideline generally recommended nutritional counseling for patients with eating disorders, with a psychiatrist's approval.

All guidelines provided recommendations for specific psychological interventions, except the WFSBP guideline. Cognitive-behavioral therapy was consistently recommended by all six guidelines, followed by guided (n = 6) or unguided (n = 2) cognitive-behavioral self-help treatment and interpersonal psychotherapy (n = 4). An explicit recommendation for psychodynamic therapy was made by the German guideline only. With respect to first-line psychotherapy, four guidelines recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy, while one guideline favored guided cognitive-behavioral self-help treatment (the United Kingdom). Regarding the treatment format, guidelines varied highly, with one guideline specifically recommending individual psychotherapy (Australia and New Zealand), one prioritizing group format (the United Kingdom), and two guidelines not including any preference (The Netherlands, the United States). Family-based treatment was recommended for children and adolescents with BED by the Dutch guideline only.

The use of antidepressants was generally recommended by three guidelines (Australia and New Zealand, Spain, the United States). These three guidelines and three other guidelines (Germany, The Netherlands, WFSBP) consistently made a specific recommendation in favor of SSRIs for reducing binge-eating episodes, at least in the short-term. For TCAs, only the WFSBP recommended their use, particularly imipramine. For anticonvulsants, three guidelines (Australia and New Zealand, the United States, WFSBP) consistently recommended the use of topiramate, while the remaining guidelines did not report on it. Consistently, two out of two guidelines reporting on antiobesity medications explicitly recommended their use, specifically orlistat, for weight loss in patients with BED and comorbid obesity. In addition to weight loss, the antiobesity medication sibutramine was recommended for reducing binge eating (the United States). Two guidelines explicitly made a recommendation for pharmacological treatment in conjunction with psychological therapies (Australia and New Zealand, the United States).

Of note, three guidelines reported on the treatment of comorbidities, and two guidelines made recommendations for the medical management of BED.

DISCUSSION

The current systematic review of evidence-based clinical guidelines for eating disorders revealed many consistent recommendations, but also notable differences among the guidelines.

For the treatment of AN, the guidelines showed a substantial agreement on the amount of recommended weight gain, while recommended daily energy intakes varied considerably, which is consistent with Herpertz-Dahlmann et al.[28], who had narratively reviewed four European guidelines for the treatment of AN. Also in line with their findings, the recommendations for nutritional supplements varied widely, against a background of a lack of evidence. More consistently, most guidelines made recommendations for specific psychological interventions in the treatment of AN, especially for family-based therapy for younger patients, because of a large evidence base [40,50,51]. Most guidelines further supported cognitive-behavioral therapy [52]. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, the Maudsley Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults, and the Specialist Supportive Clinical Management were even recommended as first-line therapies by the two current guidelines from The Netherlands and the United Kingdom, based on recently published results [53▪▪,54▪▪]. Little agreement was found for psychodynamic therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy as alternative treatments, because of scant evidence for their use [55–57]. A need for further research on the psychological treatment of AN was noted for all ages [28,58].

Regarding pharmacotherapy of AN, recommendations varied widely – four guidelines, among them the medically oriented WFSBP guideline, made no specific recommendation for any medication, or advocated against their sole or primary use. The greatest level of consistency across four out of nine guidelines was found for the careful use of antipsychotics to reduce associated obsessional thinking in patients with AN, but it was inconsistent whether or not antipsychotics should be recommended for weight gain. In addition, three guidelines generally recommended antidepressants for the treatment of depressive symptoms, but a consistent recommendation for specific types of antidepressants (SSRIs, TCAs) could not be identified. Single guidelines’ recommendations emerged regarding other medications, for example, against the use of bupropion. Estrogen was with some consistency recommended to be offered only upon specific indication (see [59▪]). Overall, these inconsistent pharmacological recommendations for the treatment of AN may reflect the scarce evidence base for the pharmacological treatment of this disorder [13,28,60▪].

For the treatment of BN, all guidelines but the medically oriented WFSBP guideline issued recommendations on specific psychological interventions: The majority of them recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy as a first-line treatment for BN, reflecting the treatment literature [11,52]. In contrast, the United Kingdom guideline recommended offering cognitive-behavioral self-help treatment first, presumably because of an emphasis on cost-effectiveness [27], for which initial data are available [61]. Interpersonal psychotherapy was recommended as an alternative to cognitive-behavioral therapy by the majority of guidelines, given its slower short-term efficacy, but equivalent long-term efficacy [52]. Psychodynamic therapy was recommended by the German and guideline from the United States only, despite its limited evidence base [62,63], possibly because of particularities in healthcare systems. Family-based therapy was recommended mostly for younger patients by half of the guidelines, which is supported by recent clinical research [64]. Most guidelines recommended self-help treatment, and the majority of these, especially the more recent guidelines, emphasized guided cognitive-behavioral self-help treatment, documented to be efficacious in the treatment of BN [65]. A few recommendations with unclear rationale and/or sparse evidence base were issued for alternative treatments (e.g., a combination of psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral therapies) and nutritional counseling.

Regarding the pharmacological treatment of BN, most guidelines recommended antidepressants for the treatment of BN, specifically the SSRI fluoxetine, albeit with several restrictions (e.g., combined use with psychotherapy only). Fluoxetine has approval for the treatment of adults with BN in several countries (e.g., the United States, Germany). However, only a few and often inconsistent recommendations were made for the use of TCAs and anticonvulsants, specifically topiramate, and against the use of MAOIs and lithium. Again, these singular and contradictory recommendations may mirror the overall paucity of research on pharmacological treatments of BN [13].

For the treatment of BED, all guidelines provided recommendations for specific psychological interventions (except the medically oriented WFSBP guideline). Cognitive-behavioral therapy was consistently recommended by all respective guidelines and mostly as a first-line treatment, given its comprehensive evidence base [10▪▪]. Cognitive-behavioral therapy was followed by cognitive-behavioral self-help treatment, with the majority of guidelines recommending a guided format, a treatment with an increasing evidence base [65]. Of note, the guideline from the United Kingdom favored guided cognitive-behavioral self-help treatment as a first-line treatment, likely for economic reasons, as described for BN. Interpersonal psychotherapy was further recommended by the majority of the guidelines, based on a small number of studies [52]. An explicit non-evidence-based recommendation for psychodynamic therapy was made by the German guideline only [66] reflecting healthcare system specificities, while family-based treatment was recommended for children and adolescents with BED by the Dutch guideline only, based on emerging evidence for family-based treatment of adolescents with BN [64]. A recommendation for nutritional counseling was made by two guidelines, which may reflect findings of lower efficacy of this treatment regarding binge-eating outcome [67▪▪].

Regarding the pharmacological treatment of BED, the majority of guidelines made a recommendation for SSRIs, which is in line with current literature [10▪▪], while only the WFSBP guideline recommended TCAs, based on studies published before 1999. Three guidelines recommended the use of the anticonvulsant topiramate; however, the drug's side-effects, especially cognitive impairment, have been noted [68]. Regarding antiobesity medications, two guidelines recommended orlistat for weight loss in BED and BN [69,70] and sibutramine for binge eating in BED, the latter being withdrawn from many markets because of adverse cardiovascular events. Combined psychological and pharmacological treatment was recommended by two guidelines; however, this is not supported by current evidence [71▪▪].

Overall, consistency across guidelines seemed to be the greatest for psychological treatments and for single medications with a larger evidence base, while for psychological and medical treatments with a smaller evidence base, recommendations varied considerably, and expert consensus played a greater role. Regarding the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based treatments into clinical practice, the guidelines thus do endorse main empirically validated treatment approaches with considerable agreement, but beyond this, the variability is greater in what recommendations evidence-based clinical guidelines subsume. A larger evidence base is critical in offering clinically reliable and consistent guidance in eating disorders, and many important areas of future clinical research have been identified for all eating disorders at different ages, given the treatment gap and the research-practice gap described at the outset of this article [15▪▪,22▪].

The available evidence is one reason for differences among guidelines. Among additional reasons, while several guidelines were issued within the past 3 years or are about to be published, the majority were 5 years and older. Especially for disorders such as BED with a large recent increase in clinical research, changes in recommendations over time are to be expected. Several recommendations were non-evidence-based and likely reflected particularities in healthcare systems, for example, the availability of outpatient, day patient, and inpatient settings or of therapists trained in a specific intervention. The guidelines differed as well in their scope, considering treatment in selected aspects (e.g., Denmark, France) or comprehensively (e.g., Germany, the United States). Some guidelines were created by one healthcare profession or one specialized professional organization only (e.g., the guidelines from the United States, WFSBP) and may thus reflect the view of this profession only. Most guidelines, however, pursued a multiprofessional approach in guideline development, and some of them noted the inclusion of other stakeholders as well. In fact, the current literature for guideline development advocates for broad stakeholder involvement of all relevant professions, healthcare providers, and patients (e.g., [25–27]) for optimal acceptance and implementation.

Another additional source for differences among guidelines may be how the evidence was examined, with guidelines based on meta-analyses (e.g., Germany, the United Kingdom), systematic reviews (e.g., Australia and New Zealand, the United States), or unsystematic reviews of the evidence (e.g., France). The transparency with which evidence was converted into specific recommendations further varied across guidelines; several guidelines explicitly evaluated the strength of evidence and provided clear rationale for a specific recommendation (e.g., Germany, the United Kingdom, WFSBP), while others did not (e.g., France), leaving the empirical foundation of a recommendation unclear. To develop a guideline, it has been recommended to use a systematic approach to evaluate the strength of evidence, for example the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation [72], or the system of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [26,73]. For some guidelines, only summary statements without the systematic review component were available in the review languages, making the empirical background of a recommendation difficult to understand (e.g., Denmark). Guidelines differed further in readability, with most guidelines providing clear or even standardized recommendations that were easily located (e.g., Germany, the United Kingdom), while others provided them in a more complex text format (e.g., the United States). Although these aspects are central to the quality of a guideline, it is notable that a systematic quality evaluation [74] of clinical eating disorder guidelines is currently lacking; this was considered to be beyond the scope of this treatment-oriented review but could help to systematically identify strengths and limitations of current eating disorder guidelines.

Strengths of this study were a systematic compilation of main treatment recommendations of current evidence-based eating disorders guidelines. Not within the scope of this review were: general setting-oriented recommendations (e.g., communication with the patient, therapeutic infrastructure, organization of transitions between different levels of care); methods for the identification, assessment, and diagnosis of eating disorders; and the practical applicability of the guidelines and their actual implementation in clinical settings. Several of these aspects warrant further investigation. One further limitation is that several guidelines had to be excluded from this review because of not meeting the language requirement. For further comparative research, it would be desirable to have guidelines published not only in the national language, but also in other languages for international reception.

CONCLUSION

The current systematic, international comparison demonstrated notable commonalities and differences among current evidence-based clinical guidelines for eating disorders. Currently, several evidence-based clinical guidelines for eating disorders are in progress (e.g., Germany, the United States). Because developing and updating clinical guidelines is time-consuming and complex, an international coordination of guideline development, for example, across the European Union, would be desirable. Collaborative efforts would need to carefully specify the goals and scope of a common ‘guideline trunc’ which should be based on an elaborated, quality-assuring developmental process, while accounting for different cultures and national requirements. European clinical studies on major research gaps could represent an important first step toward this end.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Jamie L. Manwaring, PhD and Lisa Opitz, BSc for her help in editing this article.

Financial support and sponsorship

A.H. and R.S. are funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant 01EO1501).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treasure J, Claudino AM, Zucker N. Eating disorders. Lancet 2010; 375:583–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013; 382:1575–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4▪.Agh T, Kovács G, Supina D, et al. A systematic review of the health-related quality of life and economic burdens of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. Eat Weight Disord 2016; 21:353–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A systematic summary of health-related quality of life and economic burden in the eating disorders.

- 5.Stuhldreher N, Konnopka A, Wild B, et al. Cost-of-illness studies and cost-effectiveness analyses in eating disorders: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord 2012; 45:476–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents: results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68:714–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatr 2013; 26:543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8▪.Keski-Rahkonen A, Mustelin L. Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Curr Opin Psychiatr 2016; 29:340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A narrative review of eating disorder prevalences from European countries.

- 9.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiatr 2013; 73:904–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10▪▪.Brownley KA, Berkman ND, Peat CM, et al. Binge-eating disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2016; 165:409–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A timely meta-analysis on the efficacy of psychological and medical approaches to the treatment of BED.

- 11.Hay P. A systematic review of evidence for psychological treatments in eating disorders: 2005–2012. Int J Eat Disord 2013; 46:462–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kass AE, Kolko RP, Wilfley DE. Psychological treatments for eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2013; 26:549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McElroy SL, Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, Keck PE., Jr Psychopharmacologic treatment of eating disorders: emerging findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2015; 17:35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell JE, Roerig J, Steffen K. Biological therapies for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2013; 46:470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15▪▪.Kazdin AE, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, Wilfley DE. Addressing critical gaps in the treatment of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2017; 50:170–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A succinct overview of important gaps in the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based treatment into clinical practice.

- 16.Cooper M, Kelland H. Medication and psychotherapy in eating disorders: is there a gap between research and practice? J Eat Disord 2015; 3:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17▪.Micali N, Martini MG, Thomas JJ, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of eating disorders amongst women in mid-life: a population-based study of diagnoses and risk factors. BMC Med 2017; 15:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A longitudinal study of mid-life prevalence rates of eating disorders in women in relation to psychosocial risk factors.

- 18▪.Peterson CB, Becker CB, Treasure J, et al. The three-legged stool of evidence-based practice in eating disorder treatment: research, clinical, and patient perspectives. BMC Med 2016; 14:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A narrative review of evidence-based practice in eating disorders.

- 19▪.Regan P, Cachelin FM, Minnick AM. Initial treatment seeking from professional healthcare providers for eating disorders: a review and synthesis of potential barriers to and facilitators of ‘first contact’. Int J Eat Disord 2017; 50:190–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A systematic review on treatment-seeking in the eating disorders.

- 20.Kosmerly S, Waller G, Robinson AL. Clinician adherence to guidelines in the delivery of family-based therapy for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2015; 48:223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Von Ranson KM, Wallace LM, Stevenson A. Psychotherapies provided for eating disorders by community clinicians: infrequent use of evidence-based treatment. Psychother Res 2013; 23:333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22▪.Waller G. Treatment protocols for eating disorders: clinicians’ attitudes, concerns, adherence and difficulties delivering evidence-based psychological interventions. Curr Psychiat Rep 2016; 18:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A narrative review on the use of evidence-based treatment manuals in clinical practice.

- 23.Cooper Z, Bailey-Straebler S. Disseminating evidence-based psychological treatments for eating disorders. Curr Psychiat Rep 2015; 17:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. The dissemination and implementation of psychological treatments: problems and solutions. Int J Eat Disord 2013; 46:516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany – Standing Committee Guidelines [Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF – Ständige Kommission Leitlinien]. AWMF-regulations guidelines [AWMF-Regelwerk ‘Leitlinien’]. 2012; Available at: www.awmf.org/leitlinien/awmf-regelwerk.html. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute of Medicine (IOM). Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Developing NICE guidelines: the manual. 2014; Available at: nice.org.uk/process/pmg20. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herpertz-Dahlmann B, van Elburg A, Castro-Fornieles J, Schmidt U. ESCAP expert paper: new developments in the diagnosis and treatment of adolescent anorexia nervosa – a European perspective. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015; 24:1153–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hay P, Chinn D, Forbes D, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014; 48:1–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany [Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF]. S3-guideline for the assessment and therapy of eating disorders [S3 Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie von Essstörungen]. 2010; Available at: www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/051-026.html. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dutch Foundation for Quality Development in Mental Healthcare. Practice guideline for the treatment of eating disorders [Zorgstandaard Eetstoornissen]. Utrecht: Netwerk Kwaliteitsontwikkeling GGz; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Working Group of the Clinical Practice Guideline for Eating Disorders. Clinical practice guideline for eating disorders. Quality plan for the national health system of the ministry of health and consumer affairs 2009; Madrid: Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Research, Available at: www.guiasalud.es/egpc/traduccion/ingles/conducta_alimentaria/completa/apartado00/preguntas.html. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Eating disorders: recognition and treatment, full guideline. 2017; Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yager J, Devlin MJ, Halmi KA, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. 3rd ed.2006; Washington, DC: APA, Available at: psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/eatingdisorders.pdf. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yager J, Devlin MJ, Halmi KA, et al. Guideline watch (August 2012): practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. 3rd ed.2012; Washington, DC: APA, Available at: psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/eatingdisorders-watch.pdf. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aigner M, Treasure J, Kaye W, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of eating disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry 2011; 12:400–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danish Health Authority. National clinical guideline for the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Quick guide. 2016; Available at: www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2016/∼/media/36D31B378C164922BCD96573749AA206.ashx. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danish Health Authority. National clinical guideline for the treatment of moderate and severe bulimia. Quick guide. 2016; Available at: www.sst.dk/en/publications/2015/national-clinical-guideline-for-the-treatment-of-moderate-and-severe-bulimia. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haute Autorité de Santé. Clinical practice guidelines: anorexia nervosa: management. 2010; Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2013-05/anorexia_nervosa_guidelines_2013-05-15_16-34-42_589.pdf. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blessitt E, Voulgari S, Eisler I. Family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2015; 28:455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lock J, Le Grange D, Agras WS, Dare C. Treatment manual for anorexia nervosa. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leichsenring F, Luyten P, Hilsenroth MJ, et al. Psychodynamic therapy meets evidence-based medicine: a systematic review using updated criteria. Lancet Psychiatry 2015; 2:648–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES. Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. New York: Basic Books; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McIntosh VV, Bulik CM, McKenzie JM, et al. Interpersonal psychotherapy for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2000; 27:125–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt U, Wade TD, Treasure J. The Maudsley model of anorexia nervosa treatment for adults (MANTRA): development, key features, and preliminary evidence. J Cogn Psychother 2014; 28:48–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McIntosh VV, Jordan J, Luty SE, et al. Specialist supportive clinical management for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2006; 39:625–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McIntosh VV. Specialist supportive clinical management (SSCM) for anorexia nervosa: content analysis, change over course of therapy, and relation to outcome. J Eat Disord 2015; 3:O1. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson GT, Zandberg LJ. Cognitive-behavioral guided self-help for eating disorders: effectiveness and scalability. Clin Psychol Rev 2012; 32:343–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Forsberg S, Lock J. Family-based treatment of child and adolescent eating disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2015; 24:617–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lock J. An update on evidence-based psychosocial treatments for eating disorders in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2015; 44:707–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kass AE, Kolko RP, Wilfley DE. Psychological treatments for eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2013; 26:549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53▪▪.Byrne S, Wade T, Hay P, et al. A randomised controlled trial of three psychological treatments for anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 2017. 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A current multicenter randomized-controlled trial on the efficacy of three psychological treatments for adults with anorexia nervosa.

- 54▪▪.Schmidt U, Ryan EG, Bartholdy S, et al. Two-year follow-up of the MOSAIC trial: a multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing two psychological treatments in adult outpatients with broadly defined anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2016; 49:793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Two-year follow-up data on a multicenter randomized-controlled trial of two psychological treatments for adults with anorexia nervosa.

- 55.Carter FA, Jordan J, McIntosh VV, et al. The long-term efficacy of three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: a randomized, controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord 2011; 44:647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McIntosh VV, Jordan J, Carter FA, et al. Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zipfel S, Wild B, Groß G, et al. Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 383:127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hay PJ, Claudino AM, Touyz S, Abd Elbaky G. Individual psychological therapy in the outpatient treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015. CD003909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59▪.Robinson L, Aldridge V, Clark EM, et al. Pharmacological treatment options for low bone mineral density and secondary osteoporosis in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review of the literature. J Psychosom Res 2017; 98:87–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A systematic review on bone mineral density in women with anorexia nervosa.

- 60▪.Miniati M, Mauri M, Ciberti A, et al. Psychopharmacological options for adult patients with anorexia nervosa. CNS Spectr 2016; 21:134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A systematic review of pharmacological treatment of adult anorexia nervosa.

- 61.Lynch FL, Striegel-Moore RH, Dickerson JF, et al. Cost-effectiveness of guided self-help treatment for recurrent binge eating. J Consult Clin Psychol 2010; 78:322–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abbate-Daga G, Marzola E, Amianto F, Fassino S. A comprehensive review of psychodynamic treatments for eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord 2016; 21:553–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poulsen S, Lunn S, Daniel SI, et al. A randomized controlled trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 2014; 171:109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Le Grange D, Lock J, Agras WS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of family-based treatment and cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent bulimia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015; 54:886–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beintner I, Jacobi C, Schmidt UH. Participation and outcome in manualized self-help for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder – a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2014; 34:158–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vocks S, Tuschen-Caffier B, Pietrowsky R, et al. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2010; 43:205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67▪▪.Grilo CM. Psychological and behavioral treatments for binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2017; 78 (Suppl 1):20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A succinct narrative review of psychological treatments for BED.

- 68.McElroy SL, Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, et al. Overview of the treatment of binge eating disorder. CNS Spectr 2015; 20:546–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Golay A, Laurent-Jaccard A, Habicht F, et al. Effect of orlistat in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Obes Res 2005; 13:1701–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Salant SL. Cognitive behavioral therapy guided self-help and orlistat for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:1193–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71▪▪.Grilo CM, Reas DL, Mitchell JE. Combining pharmacological and psychological treatments for binge eating disorder: current status, limitations, and future directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016; 18:55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A comprehensive review of randomized-controlled trials on combination treatments for BED.

- 72.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A. Handbook for Grading the Quality of Evidence and the Strength of Recommendations Using the GRADE Approach. Updated October 2013. gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/handbook.html. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM). Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine – levels of evidence (March 2009). 2009; Available at: www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009. [Accessed 22 June 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brouwers M, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Can Med Assoc J 2010; 182:E839–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]