Abstract

The Eps15-homology domain–containing (EHD) protein family comprises 4 members that regulate endocytic recycling. Although the kidney expresses all 4 EHD proteins, their physiologic roles are largely unknown. This study focused on EHD4, which we found to be expressed differentially across nephron segments with the highest expression in the inner medullary collecting duct. Under baseline conditions, Ehd4−/− [EHD4-knockout (KO)] mice on a C57Bl/6 background excreted a higher volume of more dilute urine than control C57Bl/6 wild-type (WT) mice while maintaining a similar plasma osmolality. Urine excretion after an acute intraperitoneal water load was significantly increased in EHD4-KO mice compared to WT mice, and although EHD4-KO mice concentrated their urine during 24-h water restriction, urinary osmolality remained significantly lower than in WT mice, suggesting that EHD4 plays a role in renal water handling. Total aquaporin 2 (AQP2) and phospho-S256-AQP2 (pAQP2) protein expression in the inner medulla was similar in the two groups in baseline conditions. However, localization of both AQP2 and pAQP2 in the renal inner medullary principal cells appeared more dispersed, and the intensity of apical membrane staining for AQP2 was reduced significantly (by ∼20%) in EHD4-KO mice compared to WT mice in baseline conditions, suggesting an important role of EHD4 in trafficking of AQP2. Together, these data indicate that EHD4 play important roles in the regulation of water homeostasis.—Rahman, S. S., Moffitt, A. E. J., Trease, A. J., Foster, K. W., Storck, M. D., Band, H., Boesen, E. I. EHD4 is a novel regulator of urinary water homeostasis.

Keywords: endocytic recycling, arginine vasopressin, aquaporin-2, aquaporin-4

Epithelial cells of the kidney’s nephrons modify the composition of urine by selective removal or addition of solutes and water with the help of various channels and transporters located on their membranes. A key means of regulating urine composition is via the regulation of the presence and abundance of these channels and transporters on the apical membrane of the epithelial cells (1). In steady-state conditions, expression of many of the channels and transporters on the apical membrane represents the culmination of a very dynamic process, wherein constitutive recycling works in balance with postsynthetic membrane localization, endocytosis, and lysosomal degradation (2, 3). Neurohumoral and other factors modulate the recycling of channels and transporters in the kidney epithelium to adjust urine composition and thus water and salt homeostasis. A classic example of this process is the increased phosphorylation and forward trafficking of aquaporin 2 (AQP2) toward the apical membrane that occurs in the principal cells of the collecting duct when the hormone arginine vasopressin (AVP), released in response to high plasma osmolality or low blood volume (4), binds to its V2 receptor (V2R) on the basolateral side of these cells. The on-demand apical localization of several other channels and transporters in the kidney is regulated in a similar manner (5–12).

Endocytosis is a highly regulated process that allows mammalian cells to internalize components of the membrane, receptor–ligand complexes, and extracellular materials to be sent to various intracellular organelles (13). Whereas some of these internalized contents are destined for degradation via the lysosomal system, some of the endocytosed materials travel through the endosomal system and return to the membrane by a process called endocytic recycling. The constant uptake and return of membrane components via endocytic recycling is important in the maintenance of membrane composition and dynamics (14) and is therefore highly coordinated and regulated. The recently identified Eps15 homology domain–containing (EHD) protein family consists of 4 members (EHD1–4) that regulate promoting membrane tubulation and vesiculation processes, primarily in the endocytic recycling pathway (15). The endocytic regulatory functions of EHD proteins are mediated by their ATPase activity and protein–protein interactions, a major determinant of which is their C-terminal Eps15 homology domain that interacts with NPF motifs, with acidic C-terminal residues located C-terminal to phenylalanine, on their binding partners (16). Tissue distribution analysis of the EHD proteins has revealed abundant expression across tissues, including the heart (17), brain (18), and kidney (15) and in cell types of various origins (19); however, very little is known regarding the precise functions of EHD proteins in vivo.

Recently, we and others (20) have generated EHD-knockout (KO) mice and the study of which has begun to reveal key physiologic processes to be regulated by these proteins, such as EHD3-regulated maintenance of cardiac membrane excitability (21) and EHD1- and EHD4-dependent development of testes size and spermatogenesis in male mice (22). Moreover, we have reported (23) that mice lacking both EHD3 and -4 develop renal thrombotic microangiopathy-like glomerular lesions in association with reduced glomerular VEGFR2 expression, signifying the importance of these proteins in glomerular filtration barrier homeostasis. This study also showed that mice lacking only EHD3 do not develop any disease as a result of a compensatory increase in EHD4 within the glomerular endothelium. Glomerular EHD4 staining was very low in baseline conditions in wild-type (WT) mice and appeared restricted to endothelial cells. Although this previous study indicated an important role for EHD3 and -4 in the glomerulus, whether EHD4 may play a role in trafficking of proteins in the tubular and collecting duct system has remained unanswered. In addition, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Epithelial Systems Biology Laboratory’s proteomic databases (24) of inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) cells and mpkCCD cells (an immortalized mouse cortical collecting duct cell line), revealed EHD4 expression in the collecting duct, suggesting that EHD4 plays one or more additional roles in the kidney. However, to date, the role of EHD4 per se in normal renal physiology has not been directly addressed. The purpose of our study, therefore, was to determine the roles of EHD4 in the kidney, particularly in the regulation of water homeostasis, given the proteomics-based evidence of collecting duct EHD4 expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal studies were approved in advance by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Experiments were conducted on 12–18-wk-old male and female Ehd4−/− (EHD4-KO) mice (n = 6 for male; n = 5 for female), generated (23) on the C57Bl/6 background. Age-matched male and female C57Bl/6 WT mice (n = 9 for male; n = 4 for female) were used as control mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The animals were housed in cages maintained at room temperature, 60% humidity with a 12–12 h light–dark cycle. The mice were given free access to normal rodent chow (7012; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI, USA) and drinking water, except as described below.

Cell culture

Mouse cortical collecting duct principal cell line (mpkCCD cells) was generously shared by Dr. Mark Knepper (NIH). The cells were grown in modified DMEM/F-12 medium with composition as described in Hasler et al. (25) and were seeded on permeable filters (Transwell, 0.4-μm pore size, 1-cm2 growth area; Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) at a density of 50,000 cells/well for Western blot analysis and 100,000 cells/well for surface biotinylation. Cells were subjected to Lipofectamine 2000–mediated transfection (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) followed by retroviral transduction with either a nontargeting (control), or an EHD4-specific short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (sequence: 3′-GAAGGCTCGAGAAGGTATATTGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGATCGCCCATCAATGGCAAGATATAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTATATCTTGCCATTGATGGGCGACTGCCTACTGCCTCGGACTTCAAGGGGCTAGAATTCGAGCA-5′), and positively selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin (Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Transfected cells were grown on the filter for 3 d in complete medium before switching to serum/hormone-free medium. To simulate baseline conditions, 0.1 nM deamino-d-arginine vasopressin (d-DAVP; Millipore-Sigma) was applied on the basolateral side for 24 h, whereas 10 nM d-DAVP was used as a stimulatory dose of d-DAVP. At the end of the 24-h period, cells were extracted and lysed as described in Hasler et al. (25).

Baseline urinary analysis

Animals were placed in individual metabolic cages for 24 h for comparison of baseline physiologic parameters, specifically food intake, water intake, and urine output. The animals had free access to food and water during the experiment and were returned to their home cages at the end of the experiment. Spot urine samples were also collected after spontaneous voiding. Urine samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. Urine osmolality was analyzed by freezing-point depression with an osmometer (model 3250; Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA, USA) and plasma osmolality using a vapor pressure osmometer (Model 5520; Wescor, Logan, UT, USA). Electrolyte concentrations of the samples were measured using Ion Selective Electrode technology (EasyElectrolytes; Medica Corp., Bedford, MA, USA). AVP and creatinine concentrations were measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions with a Arg8-Vasopressin ELISA kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) and QuantiChrom Creatinine assay kit (Bioassay Systems, Hayward, CA, USA), respectively.

Acute water load experiment

Each mouse underwent intraperitoneal injection of 2 ml sterile water and was placed in a metabolic cage for 6 h, during which food and water were withheld. Urine samples were collected hourly for 6 h and stored at −80°C until analysis of osmolality, as previously described.

Water restriction experiment

Male WT and EHD4-KO mice (n = 6–7 in each group) were placed in individual metabolic cages with access to food and water. The mice were allowed to acclimate to the cage for the first 24 h, followed by a 24-h baseline collection period, then a 24-h water restriction (WR) period during which no drinking water was provided. During these periods, urine was collected under paraffin oil (to prevent evaporation) and stored at −80°C for later analysis of osmolality, as above. To test for compensatory changes in EHD protein expression in response to WR, female EHD4-KO mice underwent a similar protocol, except that one group continued to receive access to water throughout the second 24-h collection period [euhydrated (EH) mice, n = 4], and the other group was WR (EH mice, n = 6). At the end of the EH or WR period, animals were euthanized to collect renal tissues for immunoblot analysis.

Acute furosemide experiment

As a test of Na-K-2Cl cotransporter 2 (NKCC2) activity in vivo, EHD4-KO and WT mice received injections of furosemide (40 mg/kg, i.p.; Hospira, Lake Forest, IL, USA) and an equivalent volume of vehicle (polyethylene glycol) on 2 separate occasions. Immediately after the injections, the mice were placed in metabolic cages, food and water were withheld, and urine was collected for a 4-h period. The difference in urine volume and sodium excretion between vehicle and furosemide treatments for each mouse was then calculated and compared between groups.

Tissue homogenate preparation

Mice were euthanized by thoracotomy under isoflurane anesthesia, accompanied by cardiac puncture and exsanguination to allow for blood and tissue collection. Plasma was obtained upon centrifugation, whereas the other tissues were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. One kidney of each mouse was dissected into the inner medulla (IM), outer medulla (OM), and cortex, and the other was cut longitudinally for histologic analyses and immersion fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin then embedded in paraffin. Additional WT mice were used for isolation of nephron segments for EHD4 immunoblot analysis. The Percoll gradient (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) centrifugation method was used to obtain separate preparations of proximal tubules and distal tubules from a collagenase-digested cortical tubular suspension, according to methods described previously with minor modifications (26, 27). Medullary thick ascending limbs (mTALs) were freshly prepared from the inner stripe of the OM by a minor modification of the method described previously (28). IMCDs were isolated from the renal IM according to a modified version of the protocol (29). Hypothalamic tissue was collected and processed as described by Nørregaard et al. (30) and was analyzed for EHD1 and -3 expression levels. Renal tissues were homogenized in kidney extraction buffer: 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol (pH 7.4); 200 µl for each IM sample or 10 times w/v for OM and cortex) and a cocktail of protease inhibitors [final concentrations: 1 mM PMSF, 2 µM leupeptin, 1 µM pepstatin A, a 1:1000 dilution of 0.1% aprotinin, 14.3 mM 2-ME, and 10 µl/ml phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (all from Millipore-Sigma)]. Supernatant from the homogenates was collected after centrifugation at 10,000 g for 5 min in 4°C, and protein concentration of each sample was measured by the Bradford method (protein assay kit; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Homogenates were stored at −80°C until further analyses were performed.

Surface biotinylation

Control and EHD4 shRNA-transfected mpkCCDc14 cells were seeded at a density of 100,000 cells/well on semipermeable filters of Transwell systems and cultured for 3 d to perform surface biotinylation (31). In brief, cells were treated with d-DAVP (0.1 nM for baseline stimulation) for 24 h at 37°C at the basolateral sides. At the end of the 24-h period, the cells were washed 3 times with ice-cold PBS-CM [10 mM PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2, and 0.1 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.5)], followed by incubating the cells for 45 min at 4°C in ice-cold biotinylation buffer [10 mM triethanolamine, 2 mM CaCl2, 125 mM NaCl (pH 8.9)] containing 1 mg/ml sulfosuccinimidyl 2-(biotinamido)-ethyl-1,3-dithiopropionate (Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin; Thermo Fisher Scientific) on the apical side. Cells were then washed once with quenching buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl in PBS-CM (pH 8)], and twice with PBS-CM, followed by lysing the cells as previously described. The lysates were sonicated at 2 × 6 pulses at 20% of amplitude and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. Next, the supernatant was transferred to columns (Pierce Spin Column Snap Cap, 69725; Thermo Fisher Scientific), which were previously loaded with 200 μl Neutravidin agarose resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated for 60 min at room temperature with end-over-end mixing. At the end of the 60-min incubation, the columns were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 1 min, and the flowthrough was discarded. After the column was washed with degassed PBS containing protease inhibitors 6–8 times, 50 μl of 1× sample buffer containing 50 mM DTT was added to the column and incubated for 60 min at room temperature. The final flowthrough was collected in a 1.5-ml tube and heated at 65°C for 10 min before proceeding to Western blot analysis. Total loaded protein was analyzed by Revert Total Protein Stain (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Quantitative immunoblot analysis

Expression levels of different proteins in the renal tissues were analyzed by resolving extracts on SDS-PAGE, followed by subsequent electric transfer to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad). The PVDF membranes were blocked with Odyssey Blocking Buffer (Li-Cor Biosciences) for 1 h and then incubated overnight in an optimized concentration of the respective primary antibody at 4°C. After multiple washes in 10 mM Tris-buffered saline and 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST), the membranes were incubated in appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies, and the membranes were scanned, viewed, and analyzed with an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. β-Actin (Millipore-Sigma) was used as a loading control. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-EHD1–4 (generated as previously described) (15); rabbit anti-EHD4 (ab-83859; AbCam, Cambridge, MA, USA); rabbit anti-AQP1, goat anti-AQP2, anti-AQP3 and anti-AQP4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA); rabbit anti-ps256AQP2 (ab-109926; AbCam); rabbit anti-NKCC2 (AB-3562P; Millipore-Sigma); rabbit anti-phospho-NKCC1-Thr212/Thr217 (ABS1004; Millipore-Sigma); and mouse HSP 70 (610607; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining

Paraffin-embedded kidney sections from WT and EHD4-KO mice (n = 3–4 per group; 3–5 images per IM section) were deparaffinized with xylene and then dehydrated with absolute ethanol. The sections were subjected to rehydration by serial immersion in 90, 80, and 70% ethanol followed by antigen retrieval by heating in citrate buffer for 20 min. After washing in 1× PBS and blocking in 5% FBS in 1× PBS for 1 h, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies against either AQP2–4 or phospho-S256-AQP2 (pAQP2) overnight at 4°C. Fluorescence-tagged secondary antibodies were added for 1 h, followed by washing and addition of mounting solution containing DAPI (VectaShield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The sections were imaged using a confocal microscope (TCS SP8; Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) at ×60 magnification. Membrane abundance of AQP2–4 and pAQP2 was quantified by measuring the pixel intensities of the channels within a consistent defined region of the apical (for AQP2 and pAQP2) or basolateral (for AQP3 and -4) membrane using the image analysis tool ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD, USA; https://imagej.nih.gov). The analysis was performed in a blinded manner in 3–5 images of IM in each mouse. In addition, hematoxylin and eosin, Masson’s trichrome, and periodic acid-Schiff–stained kidney sections were viewed by light microscopy and evaluated for general morphology in a blinded manner by a renal pathologist (K.W.F.).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with Prism 6 for Windows (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). All data are shown as the means ± sem. Results from experiments yielding a single data point per group were analyzed by Student’s t test or 1-way ANOVA, or 2-factor ANOVA to test for main effects of genotype and sex. Experiments yielding repeated measures were examined by 2-way ANOVA for repeated measures. Bonferroni correction was used for post hoc analysis, and P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant results.

RESULTS

Expression pattern of EHD4 varies across nephron segments

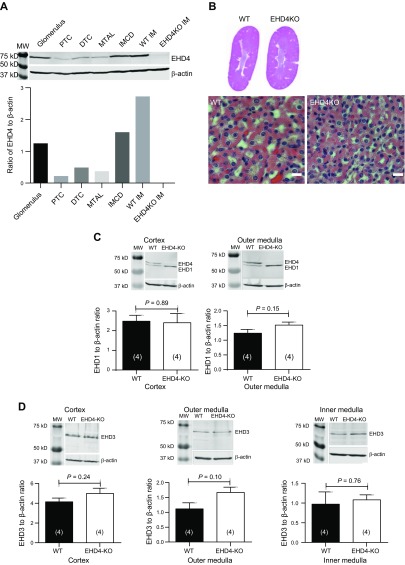

Western blot analysis confirmed expression of EHD4 in freshly isolated mouse glomeruli, proximal and distal tubular cells, IMCDs, and mTALs (Fig. 1A). The highest expression of EHD4 in nephron segments studied was observed in the IMCD-enriched nephron preparation. Cross-contamination of the other preparations with collecting ducts was checked by blotting for AQP2, with a positive signal present in the distal tubular preparation, IMCD, and IM but absent from proximal tubules, mTALs and glomeruli (data not shown). Kidneys of the EHD4-KO mice appeared to develop normally, and although light microscopy showed subtle differences in the amount of cytoplasm between WT and EHD4-KO tubular cells, no significant morphologic defect was observed in kidneys of EHD4-KO mice (Fig. 1B). Kidney-to-body weight ratio was comparable between WT and EHD4-KO mice (male: 6.1 ± 0.14 for WT vs. 6.2 ± 0.24 mg/g for EHD4-KO mice, P = 0.77; female: 5.4 ± 0.17 for WT vs. 5.0 ± 0.25 mg/g for EHD4-KO mice, P = 0.18). We did not observe any significant compensatory increase in the total abundance of any other EHD1 and -3 in kidneys of EHD4-KO mice (Fig. 1C, D). EHD2 expression was too low for accurate quantification (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Expression profile of EHD4 across nephron segments and morphology of the kidney of EHD4-KO and WT mice. A) Immunoblot of EHD4 in enriched nephron segments from C57Bl/6 mice. An equal amount of protein was loaded from homogenates of glomeruli, proximal tubular cells (PTCs), distal tubular cells (DTCs), mTAL, IMCD, and WT IM and EHD4-KO IM mice. B) Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of whole kidney sections and IM of female WT and EHD4-KO mice. C, D) Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of EHD1 (C) and EHD3 (D) in the cortex, OM, and IM of the kidney of WT and EHD4-KO mice. Graphed data are means ± sem of n mice (indicated in parentheses). Significance values were determined by unpaired Student’s t test. Original magnification, ×40.

EHD4-KO mice produce higher volumes of dilute urine than WT mice under baseline conditions

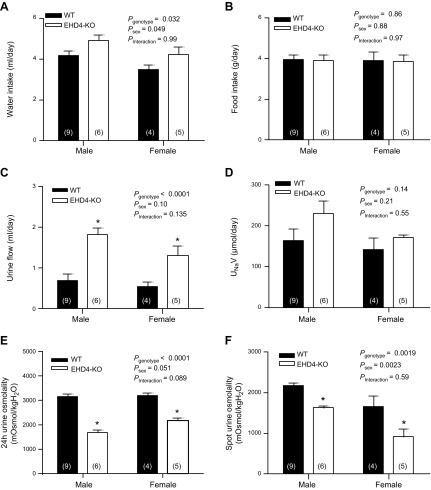

The presence of EHD4 in IMCD and mTAL suggested a potential role in both urine formation and concentration. Under 24-h baseline conditions, water intake was slightly (∼20%) but significantly higher in EHD4-KO mice vs. WT mice (Fig. 2A); food intake was not significantly different between WT and EHD4-KO mice (Fig. 2B). Notably, EHD4-KO mice produced significantly higher volumes of urine than WT mice (by ∼140–160%; Fig. 2C), with no significant difference in urinary sodium excretion (Fig. 2D). Urine osmolality of EHD4-KO mice was almost 50% lower than that of WT mice (Fig. 2E). Osmolality of spontaneously voided spot urine revealed a similar significant difference (Fig. 2F). Body weights of WT and EHD4-KO mice were comparable (females: 23.0 ± 0.6 g in WT vs. 23.4 ± 0.7 g in EHD4-KO, P = 0.65; males: 28.5 ± 2.1 g in WT vs. 28.3 ± 1.6 g in EHD4-KO, P = 0.88). Plasma creatinine levels were not significantly different between WT and EHD4-KO mice (males: 0.21 ± 0.04 for WT vs. 0.20 ± 0.04 mg/dl for EHD4-KO mice, P = 0.67; female: 0.26 ± 0.02 for WT vs. 0.25 ± 0.03 mg/dl for EHD4-KO mice, P = 0.95). Plasma osmolality was measured in these and in additional mice from which tissues were collected for analyses. Plasma osmolality was not significantly different between WT and EHD4-KO mice (Pgenotype = 0.6), or male and female mice (Psex = 0.2), nor were there sex differences in the impact of EHD4-KO (Pinteraction = 0.7; males: 326 ± 4 mOsmol/kg H2O for n = 13 WT vs. 331 ± 8 mOsmol/kg H2O for n = 10 EHD4-KO mice; female: 321 ± 5 mOsmol/kg H2O for WT vs. 321 ± 2 mOsmol/kg H2O for EHD4-KO mice, n = 8 in both groups). We did not observe any sex differences in the effects of EHD4 gene deletion on the above parameters (Pinteraction > 0.05 in all cases). Accordingly, the biochemical and histologic analyses described below were performed on either male or female mice to conserve tissue.

Figure 2.

Baseline physiologic parameters of EHD4-KO mice and WT mice. Data presented are 24-h water intake (A), food consumption (B), urine flow (C), urinary sodium excretion rate (UNaV) (D), and urine osmolality (E), as well as spot urine osmolality (F), of male and female WT and EHD4-KO mice. All values are means ± sem of n mice (indicated in parentheses). Data were analyzed by 2-factor ANOVA, testing for main effects of genotype (Pgenotype), sex (Psex), and the interaction between sex and genotype (Pinteraction). *P < 0.05 for EHD4-KO vs. WT mice of each sex (post hoc test).

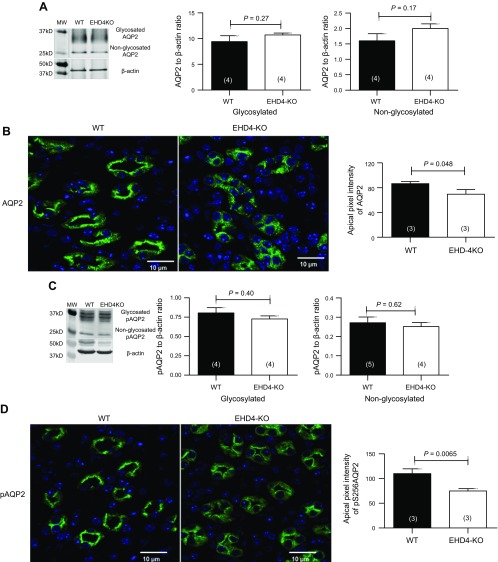

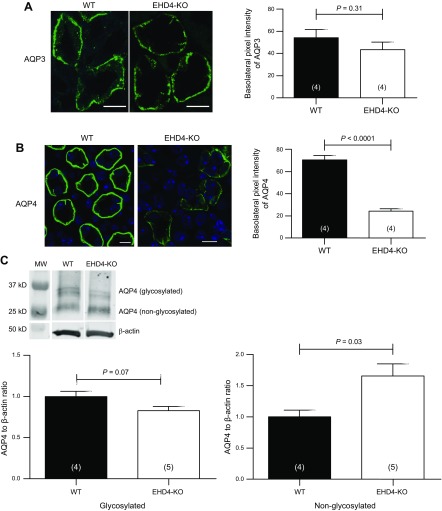

As baseline urine osmolality was reduced and urine flow increased in EHD4-KO mice compared to WT mice, we compared total cellular abundance of AQP1–4 and pAQP2 in the renal IM of these two genotypes. As shown in Fig. 3A, C, there was no difference in the total AQP2 and pAQP2 protein level in the IMs of the two groups. However, immunofluorescence staining of AQP2, as well as pAQP2, was more dispersed in EHD4-KO mice compared to that in WT mice, which showed a clear apical localization of AQP2 in principal cells of the collecting duct (Fig. 3B, D). Moreover, apical pixel intensities of both AQP2 and pAQP2 were significantly reduced (∼20% for AQP2 and ∼40% for pAQP2) in EHD4-KO, indicating less membrane accumulation of AQP2 and pAQP2 in EHD4-KO mice. In addition, we found a robust decline in the basolateral membrane intensity of AQP4 in EHD4-KO mice (∼70% reduction) when compared to the WT mice, although total staining of AQP4 also appeared to be significantly reduced in EHD4-KO mice (Fig. 4B). Using the same AQP4 antibody, Western blot analysis showed a slight reduction in glycosylated-AQP4 and a significant increase in nonglycosylated AQP4 (Fig. 4C). Basolateral abundance of AQP3 (Fig. 4A) was comparable in both the genotypes. Expression of AQP1 was similar in the IM of both the genotypes (data not shown).

Figure 3.

EHD4 regulates localization of AQP2 and p(Ser256)-AQP2 in the IM of the kidney. A) Representative immunoblot and densitometric quantification of AQP2 in the IM of female WT and EHD4-KO mice. B) Representative immunofluorescent image and blinded quantification of apical intensity of renal IM of male WT and EHD4-KO mice with AQP2 antibody. Original magnification, ×60. C) Representative immunoblot and densitometric quantification of p(Ser256)-AQP2 in the IM of male WT and EHD4-KO mice. D) Representative immunofluorescent image and blinded quantification of apical intensity of IM of male WT and EHD4-KO mice stained with p(Ser256)-AQP2 antibody. Graphed data are means ± sem of n mice (indicated in parentheses). Significance values were determined by unpaired Student’s t test.

Figure 4.

EHD4 regulates expression of AQP4, but not AQP3, in the basolateral membrane of the collecting duct. A, B) Representative immunofluorescent images and corresponding blinded quantification of AQP3 (A) and AQP4 (B) in the IM of male WT and EHD4-KO mice. C) Representative immunoblot and densitometric quantification of glycosylated and nonglycosylated AQP4 in the IM of male WT and EHD4-KO mice. Graphed data are means ± sem of n mice (indicated in parentheses). Significance values were determined by unpaired Student’s t test. Scale bars, 10 µm.

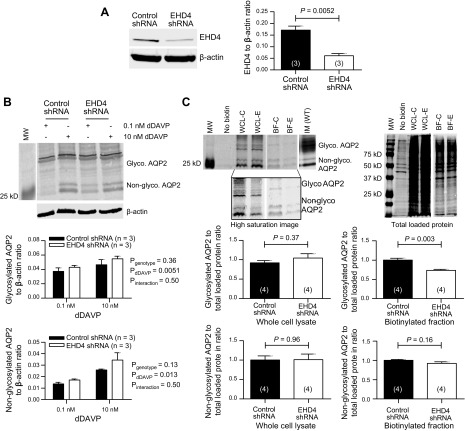

EHD4 deletion decreases the accumulation of glycosylated AQP2 in the apical membrane of cultured principal cells

Although the blinded quantification of the apical membrane pixel intensity of AQP2 immunofluorescence staining presented in Fig. 3 suggests that EHD4-KO mice have reduced apical membrane AQP2 abundance, it remains possible that some of the difference in intensity detected reflects a difference in the subapical space as well, rather than the apical membrane itself. To further confirm the role of EHD4 in the regulation of apical membrane AQP2 localization in principal cells in baseline conditions, we stably transfected mpkCCD cell line with either nontargeting (control) or EHD4-specific shRNA. Transfection with EHD4-shRNA resulted in an almost 65% reduction in the expression of EHD4 protein as compared to that in control cells (Fig. 5A). These mpkCCD cells are known to express AQP2 endogenously and the expression of AQP2 is upregulated in a dose-dependent manner in the presence of d-DAVP (25), which we also demonstrated in our cultured cells (Fig. 5B). Knockdown of EHD4 in mpkCCD cells did not significantly affect the total abundance of AQP2 at baseline (0.1 nM d-DAVP) or after a 10-nM stimulatory dose of d-DAVP, and d-DAVP increased the expression of glycosylated and nonglycosylated AQP2 in both control and EHD4-shRNA cells in a similar manner, indicating an EHD4-independent effect of d-DAVP on the total expression of AQP2. Surface biotinylation of apical AQP2 revealed that knockdown of EHD4 in mpkCCD cells significantly reduced the apical level of glycosylated but not nonglycosylated AQP2 compared with that observed in control cells (Fig. 5C), corroborating the reduction in pixel intensity observed in EHD4-KO mouse kidney sections in Fig. 3.

Figure 5.

Effect of EHD4 knockdown on the cell surface expression of AQP2 in mpkCCD cells. A) Representative immunoblot and quantification of EHD4 in mpkCCD cells transfected with either nontargeting (control) or EHD4-specific shRNA. B) Representative immunoblot and quantification of glycosylated and nonglycosylated AQP2 in control and EHD4-shRNA cells treated with 0.1 nM d-DAVP (baseline stimulation) for 24 h, followed by a 24-h stimulatory dose of 10 nM d-DAVP. C) Representative immunoblot and quantification of AQP2 after surface biotinylation of mpkCCD cells. Lysates of cells that did not undergo biotinylation, but were otherwise prepared identically to biotinylated cells, including purification via the Neutravidin agarose column, were used as a negative control. Total AQP2 (surface and cytosolic fractions that were not passed through column) in whole-cell lysate (WCL; C = control, E = EHD4-shRNA) and the biotinylated-AQP2 fraction (BF; C = control, E = EHD4-shRNA) were loaded and the appropriate bands for glycosylated and nonglycosylated AQP2 were confirmed by running a WT IM homogenate. A high-saturation image of the same blot is shown below to more clearly show the bands in the BF samples. Total loaded protein was used for normalizing the quantification of AQP2 intensity. Blotting the membranes with an antibody for heat shock protein 70 revealed no cytosolic contamination in the samples (data not shown). For representative images of Western blots, white gaps indicate where intervening lanes were spliced out, with vertical alignment maintained as per the original blot. Data are presented as means ± sem for n mice (indicated in parentheses), and were analyzed by 2-factor ANOVA or unpaired Student’s t test.

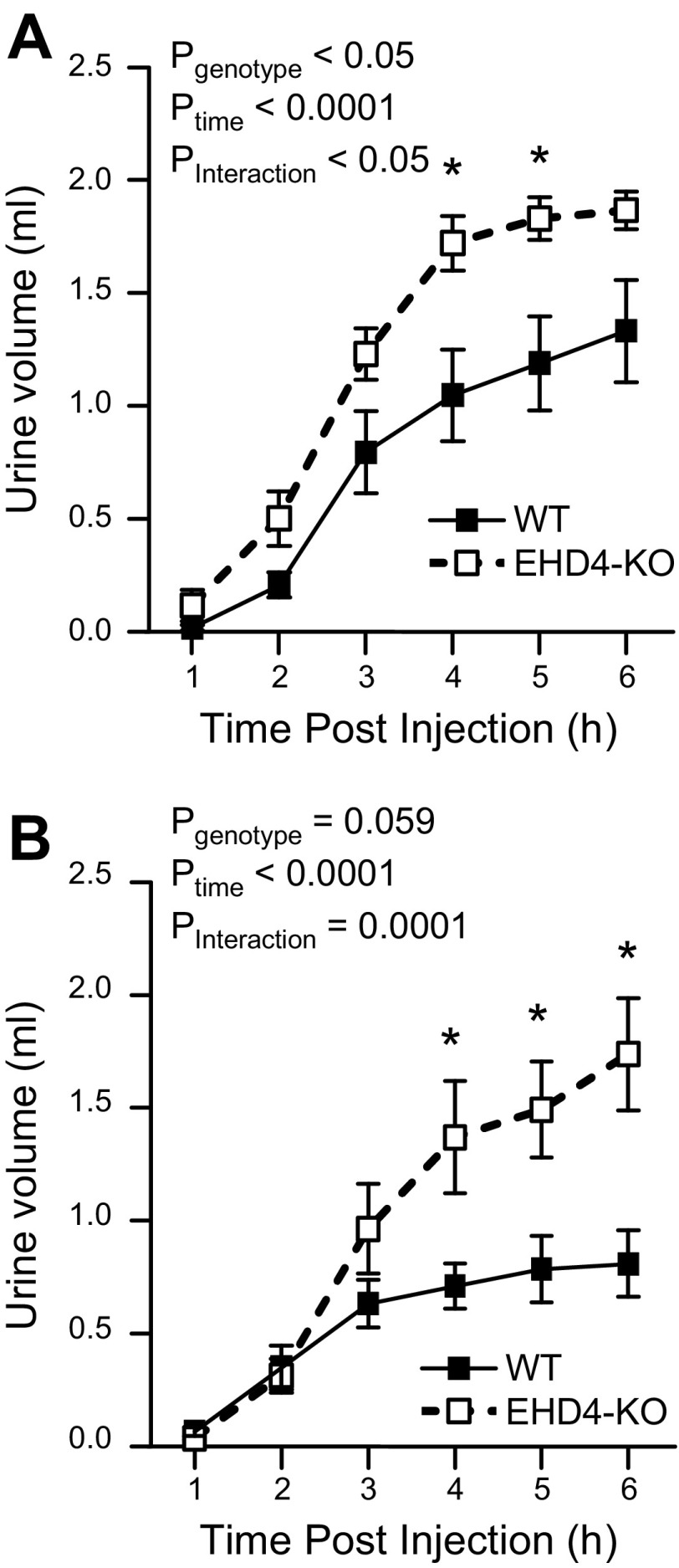

EHD4-KO mice show an exaggerated response to an acute water load

To further test the role of EHD4 in renal water handling independent of voluntary water intake, we subjected the mice to an acute water load by intraperitoneal injection. Cumulative urine excretion showed that the EHD4-KO mice displayed an exaggerated response to water loading compared to WT mice (Pinteraction < 0.05 for both sexes; Fig. 6), and both male and female EHD4-KO mice had excreted almost 75% of the water load by the end of 6 h, whereas WT mice excreted <50% (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Response of EHD4-KO mice to an acute water load as compared to WT mice. Cumulative urine volume of male (A) and female (B) WT and EHD4-KO mice over 6 h after injection of 2 ml sterile water intraperitoneally. Data were compared by 2-factor repeated-measures ANOVA, testing for main effects of genotype (Pgenotype), time (Ptime), and the interaction between time and genotype (Pinteraction). *P < 0.05 for EHD4-KO vs. WT at the corresponding time points.

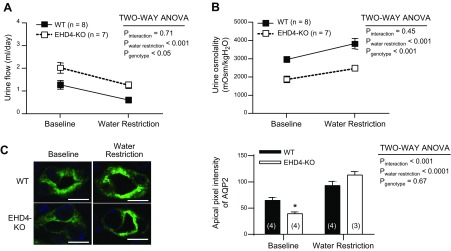

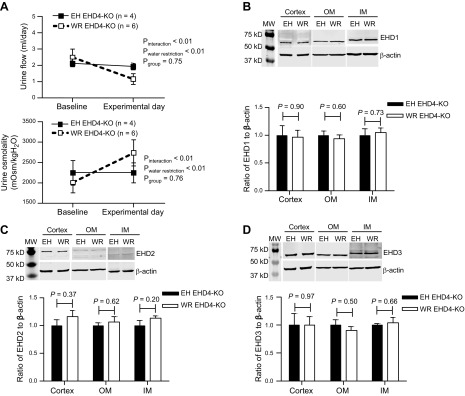

Responses to 24-h WR are similar between WT and EHD4-KO mice

To assess the contribution of EHD4 to the urine-concentrating mechanism, we subjected WT and EHD4-KO mice to 24-h WR. After 24-h WR, male WT and EHD4-KO mice showed a similar decline in urine flow and increases in urine osmolality (Fig. 7A, B). However, EHD4-KO mice maintained significantly higher urine flow and lower urine osmolality vs. WT mice, even after WR (Fig. 7). We observed similar responses in female mice, as well (n = 3 in each group; data not shown). Although the total abundance of AQP2 did not increase in WT or EHD4-KO after 24-h WR (Western blot; data not shown), the apical intensity of AQP2 increased significantly in both the groups (Fig. 7C). To determine whether there was a compensatory increase in other EHDs during WR in EHD4-KO mice, we subjected female EHD4-KO mice to either EH conditions or WR conditions for 24 h (Fig. 8A). Immunoblots of EHD1–3 in renal cortex, OM, and IM showed similar expression of these proteins in both EH and WR EHD4-KO mice (Fig. 8B–D).

Figure 7.

Response of EHD4-KO mice to 24-h WR as compared to WT mice. A, B) Urine flow (A) and osmolality (B) of male WT and EHD4-KO mice before and after 24 h WR. C) Representative immunofluorescent images and blinded quantification of the pixel intensity of AQP2 in the apical membrane of principal cells in the IM of male WT and EHD-KO mice before and after 24-h WR. Scale bars, 10 µm. Data between the genotypes were compared by 2-factor repeated-measures ANOVA to test for main effects of genotype (Pgenotype), WR (PWR), and the interaction between WR and genotype (Pinteraction). Graphed data are means ± sem of n mice (indicated in parentheses). *P < 0.05 for EHD4-KO vs. WT mice at the corresponding time point.

Figure 8.

Comparison of antidiuretic responses of EH and WR female EHD4-KO mice. A) Antidiuretic responses to 24-h WR were evaluated in terms of changes in urine flow and osmolality. All mice received access to water on the baseline day, whereas only EH (n = 4), not WR (n = 6), EHD4-KO mice received water on the experimental day. Data were compared by 2-factor repeated-measures ANOVA to test for main effects of experimental group (Pgroup), WR (PWR), and the interaction between WR and group (Pinteraction). B–D) Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of EHD1 (B), EHD2 (C), and EHD3 (D) in the renal cortex, OM, and IM of EH and WR EHD4-KO mice collected at the end of the experimental day. Please note that renal cortex, OM and IM tissues were blotted separately, and data for each region were normalized to the mean for the EH group. The mean densitometric data for each region is shown on a single graph for ease of presentation but comparisons of relative expression between different regions of the kidney cannot be made from these data. All data are means ± sem. Significance values were determined by unpaired Student’s t test.

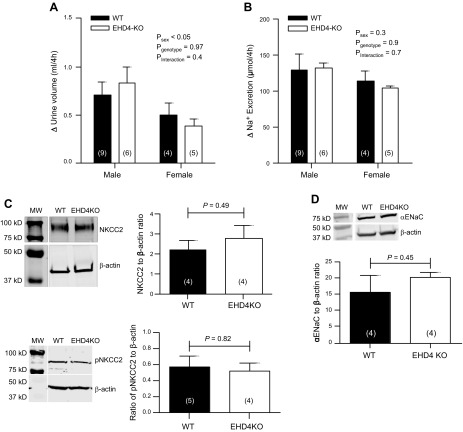

EHD4-KO and WT mice exhibit comparable responses to furosemide

The Na-K-2Cl cotransporter 2 (NKCC2), which is expressed by the mTAL, plays a key role in establishing and maintaining the urinary concentrating mechanism. To test whether the activity of this cotransporter is regulated by EHD4, we challenged WT and EHD4-KO mice with furosemide to block NKCC2. Responses are expressed as the differences in sodium excretion and urine production between acute vehicle and furosemide treatments. The natriuretic and diuretic responses after furosemide injection were comparable between the genotypes (Fig. 9A, B). Consistent with this finding, total and phosphorylated NKCC2 protein expression levels in renal OM were similar between the two genotypes (Fig. 9C). No significant difference in expression of the α subunit of the epithelial sodium channel (αENaC) was seen between groups (Fig. 9D).

Figure 9.

Effect of EHD4 deletion on NKCC2 activity and αENaC expression in vivo. A, B) Changes in (Δ) urine volume (A) and urinary sodium excretion (B), calculated as the difference between values recorded in response to furosemide and vehicle. C, D) Representative immunoblot and quantification of NKCC2 and pNKCC2 (C) in the OM and αENaC (D) in the cortex of female WT and EHD4-KO mice. Data are presented as means ± sem of n mice (indicated in parentheses), and were analyzed by 2-factor ANOVA or unpaired Student’s t test.

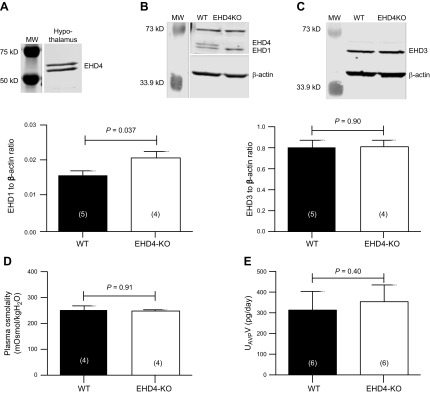

Hypothalamic expression of EHDs

To begin to address whether the polyuric phenotype observed in the EHD4-KO mice could also involve a central component, because the EHD4-KO mouse used is a global knockout, we blotted hypothalamic tissue for EHDs. EHD4 was found to be expressed in the hypothalamus (Fig. 10A), as was EHD1, whose expression was significantly upregulated in EHD4-KO mice (Fig. 10B). EHD3 was also expressed in the hypothalamus, but no difference in expression was observed between WT and EHD4-KO mice (Fig. 10C). Baseline plasma osmolality of EHD4-KO and WT mice was found to be comparable (Fig. 10D). Despite having increased urine volume, their 24-h urinary AVP excretion, an indirect index of circulating AVP, was comparable to that of WT mice (Fig. 10E).

Figure 10.

EHDs are expressed by the hypothalamus, but EHD4 deletion does not affect plasma osmolality or urinary AVP. A–C) Western blot analysis of hypothalamic expression of EHD4 (A) in a WT mouse and EHD1 (B) and EHD3 (C) in WT and EHD4-KO mice. D) Plasma osmolality of female WT and EHD4-KO mice. E) Urinary AVP excretion rate in male WT and EHD4-KO mice. Data were compared by unpaired Student’s t test, and are means ± sem of n mice (indicated in parentheses).

DISCUSSION

This study focused on elucidating the physiologic roles of EHD4 in the kidney. Our novel findings showed that, in the kidney, EHD4 is expressed differentially across the nephron, and that global deletion of EHD4 in mice results in a phenotype of mild, apparently nephrogenic, diabetes insipidus, with EHD4-KO mice showing increased excretion of osmotically dilute urine. Our data further suggest that the increased urine output in EHD4-KO is at least partially mediated by a decreased localization of AQP2 and pAQP2 at the apical membrane and possibly AQP4 at the basolateral membrane of the principal cells of the collecting duct.

To better understand the functional roles of EHD4 in the kidney, we tested whether EHD4 protein was expressed in segments of the nephron that are important in urinary concentration and salt and water homeostasis. George et al. (15) had shown previously that EHD4 is expressed in whole-kidney lysates, with immunofluorescence staining indicating expression by glomerular endothelial cells and peritubular capillaries (23). Moreover, the proteome databases constructed by the NIH Epithelial Systems Biology Laboratory reported EHD1-4 expression in the IMCD and EHD1 in the proximal convoluted tubule at the protein level, as determined by mass spectrometry (32). Unfortunately, we have been unable to successfully immunostain our kidney sections using the currently available batches of rabbit polyclonal EHD4 antibodies, whether obtained from Abcam or custom-generated by a vendor (15). We observed via Western blot that EHD4 was expressed highly in the glomerulus and IMCD, with some expression in the distal tubular cells, mTAL, and proximal tubular cells. In addition, single tubule RNA sequencing data generated by Lee et al. (32) showed that EHD4 mRNA was highest in thin ascending limb; however, it was beyond our technical capability to isolate the thin ascending limbs to confirm protein expression by Western blot. The presence of EHD4 in IMCD and mTAL raised the question of whether this protein may play a role in the urinary concentrating mechanism. Consistent with this hypothesis, EHD4-KO mice were found to produce an increased volume of osmotically dilute urine compared to WT mice under baseline conditions. This phenotype is suggestive of a defect in water reabsorption and potentially a defect in urine-concentrating ability in the absence of EHD4. Although EHD4 is abundantly expressed in the glomerulus, we did not observe any significant difference in plasma creatinine level between WT and EHD4-KO mice, suggesting that EHD4 probably does not regulate urine formation and composition by modulating GFR.

Further supporting our hypothesis that EHD4-KO mice display altered renal water handling, EHD4-KO mice excreted higher volumes of urine than did WT mice when an acute intraperitoneal water load was administered. That the response was larger in EHD4-KO mice compared to WT mice confirms that water handling by the kidney is regulated in part by EHD4. Plasma osmolality of EHD4-KO mice was similar to that of WT mice, suggesting that even though they have increased excretion of dilute urine, EHD4-KO mice are able to maintain osmotic homeostasis under normal conditions. EHD4-KO mice consumed slightly but significantly elevated amounts of water compared to the WT mice. Although comparison of raw volumes of water intake and urine output collected using metabolic cages is complicated by an unavoidable degree of urine evaporation during the funneling and collection process, the percentage increase in water intake (∼20%) was much smaller than the increase in urine flow measured by metabolic cage collections (∼140–160%). We interpret this finding to argue against a likely cause of the phenotype observed in EHD4-KO mice being primary polydipsia, although extensive additional experiments would be needed to rule this out definitively. This disparity in the apparent increase in water intake compared to urine output also suggests that mechanisms in addition to thirst may help to offset excess renal loss of water, possibly including enhanced gastrointestinal water absorption or reduced insensible water loss.

In the absence of EHD4, the subcellular distribution of both AQP2 and pAQP2 was found to be altered in the principal cells of the kidney. In WT mouse kidneys, AQP2 and pAQP2 were more apically localized, whereas in EHD4-KO mice kidney, these proteins were dispersed throughout the cells. Moreover, the apical accumulation of both AQP2 and pAQP2 was significantly reduced in the absence of EHD4, as evident from the reduced immunofluorescence staining intensity quantified at apical membrane of EHD4-KO mice. The regions of interest for this blinded analysis of our confocal immunofluorescence images were drawn close to and included the apical membrane. It therefore remains possible that some of the AQP2 staining intensity included in the analyzed regions was attributable to a difference in subapical as well as apical AQP2. However, surface biotinylation of mpkCCD cells after silencing of EHD4 also demonstrated a significant reduction of glycosylated AQP2, suggesting that the reduced immunofluorescence intensity reflects a reduced apical localization of AQP2. Together, these findings indicate that less AQP2 is available in the apical membrane to facilitate water reabsorption in EHD4-KO mice, which may contribute to the polyuria in these mice. Under baseline conditions, AQP2 is constitutively trafficked between the apical membrane, subapical vesicles and basolateral membranes (33), and when AVP levels are low, AQP2 is mainly localized to the subapical endocytic vesicles (34). Binding of AVP to its V2R in the principal cells induces the phosphorylation of AQP2 at the Ser 256 residue (34) and allows its translocation to the apical membrane (35). At the level of molecular interactions, this seemingly simple trafficking process requires the coordinated activities of multiple molecules. AVP binding to its receptor triggers several downstream signaling pathways: cAMP-mediated PKA activation, elevated intracellular Ca2+ level, and activation of other protein kinases (36). Phosphorylation of AQP2 is followed by reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (37, 38) and allows traffic of AQP2 to the apical membrane. Accordingly, AQP2 trafficking within the cell involves the intricate interactions of many proteins (3). To our knowledge, no studies to date have determined whether AQP2 directly binds with EHD4; however, the complex nature of AQP2 trafficking allows the possibility of EHD4 being a part of AQP2 traffic regulation through an indirect interaction with components of the endocytic traffic machinery. For example, actin cytoskeleton dynamics has been suggested to be regulated by EHD proteins via their interaction with Syndapin (Pacsin) I and II (39, 40) and therefore provides potential for the involvement of EHD proteins in AQP2 trafficking. Moreover, absence of Rab11-Fip2, one of the interacting partners of EHD proteins (41), disrupts the recycling of AQP2 (42), providing another possible link to the involvement of EHD proteins in AQP2 trafficking. Whether EHD4 interacts directly with AQP2 or indirectly via other common partner proteins awaits further investigation. Studies using in vitro systems and further biochemical analyses to define the mechanism and molecular interactions by which EHD4 regulates AQP2 represent an exciting future direction.

AQP4 makes an important contribution to the water permeability of the IMCD (43). As visualized by confocal immunofluorescence staining, there was a robust attenuation of the basolateral accumulation of AQP4, but not AQP3, in EHD4-KO mice, indicating that exit of water from the principal cells may also be impaired in these mice. However, we observed a contradictory expression profile of AQP4 in EHD4-KO mice via immunoblotting. Although the total abundance of inner medullary AQP4 was similar between WT and EHD4-KO mice (bands quantified together), there was a significant increase in the nonglycosylated AQP4 (lower band) and a slight decrease in glycosylated AQP4 (upper band) in EHD4-KO mice. Glycosylation is an important post-translational process for proper targeting of membrane proteins (44), including AQP2 (45). However, very little is known about the exact role of glycosylation on AQP trafficking, which makes interpreting these data difficult. A possible technical explanation for the discordant Western blot and immunofluorescent staining data could be that the antibody used for AQP4 has a preferential selectivity for glycosylated-AQP4 epitope in immunostained kidney sections, reducing the apparent overall abundance. Current understanding of AQP4 trafficking to the basolateral membrane is limited, in part because of technical challenges associated with studying the basolateral membrane of the collecting duct, and the exact role of EHD4 in this mechanism awaits further investigation. Other studies have shown that sorting of AQP3 and AQP4 in the trans-Golgi network for the basolateral membrane occurs separately (46), which could explain why only AQP4 membrane accumulation, and not AQP3, was reduced in EHD4-KO mice. In addition, the lack of a change in localization of AQP3 in EHD4-KO mice demonstrates that there is specificity of which proteins EHD4 regulates. Current understanding on AQP4 trafficking to the basolateral membrane is limited and the exact role of EHD4 in this mechanism needs further investigation.

Although our results clearly support a nephrogenic origin of diabetes insipidus seen in EHD4-KO mice, other possible explanations for their diuretic phenotype could include primary polydipsia (as previously described), or defective AVP secretion from the hypothalamus, along with a faulty AVP-induced signaling cascade in the principal cells of the collecting duct. However, 24-h urinary AVP excretion, which allowed us to indirectly assess circulating AVP (47), was comparable between WT and EHD4-KO mice, thereby suggesting that the defect in water reabsorption is not due to low circulating AVP. Direct measurement of circulating AVP would be ideal; however, this is challenging to do in mice because of the potential confounding influences of stress, anesthesia, and hypovolemia-induced AVP secretion. Although urinary excretion of AVP represents an indirect index of circulating AVP, it has been shown by others that water-loading reduces urinary AVP excretion (48), supporting that this represents an indirect but physiologically viable measurement. We found that both EHD4 and -1 are expressed in the hypothalamus, with an increase in EHD1 expression in the hypothalamus of EHD4-KO mice, suggesting that upregulation of EHD1 may compensate for the absence of EHD4. This result suggests that in EHD4-KO animals, AVP synthesis or secretion may not be defective but that EHD4-KO mice develop a polyuric phenotype, despite similar circulating AVP, which, in turn, could suggest a faulty renal response to AVP in EHD4-KO mice. We tried unsuccessfully to immunostain kidney sections for the V2R, and so an effect on V2R localization cannot be ruled out. However, the total pAQP2 level was comparable in the two genotypes in baseline conditions, suggesting that events leading to the phosphorylation of AQP2—namely, trafficking of the V2R, kinases, or both may not be regulated by EHD4. EHD4-KO mice were also able to concentrate their urine in response to WR, further suggesting that the AVP-V2R-AQP2 axis remains intact in EHD4-KO mice. In addition, the apical membrane accumulation of AQP2 increased to a similar level in WT and EHD4-KO after 24-h WR. This result indicates that the forward trafficking of AQP2 during WR is functional in EHD4-KO mice and further suggests that a major defect at the level V2R is unlikely to underlie the phenotype observed in the EHD4-KO mice. Our current working hypothesis is, therefore, that EHD4 plays a role in regulating apical trafficking of AQP2 rather than influencing the upstream components of the AVP-AQP2 axis. Retention of the antidiuretic response to WR suggests that other regulators of AVP-dependent water transport are still operational in EHD4-KO mice; whether it may be in part caused by a functional role of the remaining EHD proteins (EHD1 and -3) expressed by the collecting duct is an intriguing prospect that could be addressed in future studies by collecting duct-specific knockout of combinations of EHD proteins.

Excretion of a small volume of concentrated urine is a classic antidiuretic response to WR, and EHD4-KO mice show a similar antidiuretic response in terms of urine volume and urine osmolality as the WT mice. Moreover, expression of no other EHD protein was increased when EHD4-KO mice were WR. Together, these data suggest that the renal response to WR occurs independently of EHD4. However, even after WR, EHD4-KO mice still displayed lower urinary osmolality and higher urine flow compared with WT mice, indicating that EHD4 is required to achieve maximal urine concentrating ability.

As EHD4 was found to be expressed in the mTAL, we tested its role in the regulation of trafficking of NKCC2, an important cotransporter involved in setting up the osmotic gradient for urine concentration in the mTAL. Our data, however, showed that EHD4 deletion did not affect the activity of NKCC2, as suggested by the comparable diuretic and natriuretic responses to furosemide in EHD4-KO and WT mice. Further, if EHD4 had a major role in NKCC2-trafficking, we might expect to see evidence of salt wasting in EHD4-KO mice. Although our metabolic cage data gives the appearance of a slight trend toward increased urinary sodium excretion in male EHD4-KO mice, 2 of the 9 WT mice had relatively lower sodium excretion than the rest of the group, which had similar levels of sodium excretion to the EHD4-KO mice. We did not observe any compensatory upregulation of ENaC α subunit expression in EHD4-KO mice, although changes in activity of ENaC or other distal sodium transporters masking the effects of the loss of EHD4 on NKCC2 cannot be ruled out. Which and how many proteins in the kidney interact directly or indirectly with EHD4 are currently unknown.

Although we have mainly investigated the AQPs in this study to understand the role of EHD4 in renal water handling, several other renal processes may be affected by the deletion of EHD4 and contribute to the observed phenotype. Urea uptake and recycling within the IM and the renal medullary osmotic gradient are additional important factors in underlying renal water reabsorption and urinary concentrating ability. Analysis of the role of EHD4 in renal urea handling and whether EHD4 regulates urea transporters is beyond the scope of the current study, but this and a detailed analysis of the renal medullary osmotic gradient merit further investigation in future studies.

Previously, we have shown that combined deletion of EHD3 and -4 in mice results in smaller, pale kidneys, thrombotic microangiopathy-like glomerular lesions, and severe proteinuria (23). Although subtle differences were noticed in the amount of cytoplasm between WT and EHD4-KO tubular cells, no significant morphologic defects were observed in kidneys of EHD4-KO mice by routine light microscopy. We also report a compensatory increase in the expression of EHD4 in Ehd3−/− mice, which lacked a glomerular phenotype; however, we did not observe compensatory upregulation of other EHD proteins in kidneys of EHD4-KO mice, at least at the level of tissue homogenates. The EHD4-KO mice did, however, display a phenotypic change in renal function, indicating that any functional compensation by other EHDs in the kidney is, at best, incomplete.

Integrating the novel observations of our study, we propose that EHD4 plays an important role in regulating water homeostasis, at least in part through regulation of the subcellular localization of AQP2 and potentially AQP4. This study showed that the functional molecular apparatus of endocytic recycling is important in the regulation of water homeostasis by the kidney and provides further insight into the cellular machineries involved. Many clinical conditions, such as nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and polyuria during acute renal failure, result in increased urine volume and disturbances of the water balance of the body. Unresolved polyuria can affect solute levels in the circulation and may result in lethal conditions such as hypernatremia (49). In addition, water retention during several clinical conditions such as heart failure is also life-threatening (33). It is notable that EHD protein levels increased in the heart during heart failure (50). Whether EHD4-dependent renal water handling plays a role in these or other pathologic conditions remains to be tested, but could provide a novel target for future efforts to effectively treat water imbalance in disease states.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the following people of the University of Nebraska Medical Center for technical assistance: Eileen Marks for collection of IMCD and cortical proximal and distal tubular cells; Bangchen Wang for collection of mTAL; Timothy Bielecki for transfection of mpkCCD cells with shRNA; and Kaushik Patel and Xuefei Liu for collection of hypothalamic tissue. This work was supported by Predoctoral Fellowship 15PRE25580003 from the American Heart Association (to S.S.R.); a U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institutional Development Award (IDeA); NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant P30 GM106397 (to E.B. and H.B.); NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI) Grant CA105489 (to H.B.); and an NCI Core Support Grant to the Fred and Pamela Buffett Cancer Center. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- AQP1–4

aquaporin 1–4

- AVP

arginine vasopressin

- d-DAVP

deamino-d-arginine vasopressin

- EH

euhydrated

- EHD

Eps15 homology domain–containing protein

- αENaC

epithelial sodium channel α subunit

- IM

inner medulla

- IMCD

inner medullary collecting duct

- KO

knockout

- mpkCCD

mouse cortical collecting duct principal cells

- mTAL

medullary thick ascending limb

- NIH

U.S. National Institutes of Health

- NKCC

sodium–potassium–chloride cotransporter

- OM

outer medulla

- pAQP2

phospho-serine 256-aquaporin 2

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- V2R

V2 receptor

- WR

water restriction

- WT

wild type

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S. S. Rahman, H. Band, and E. I. Boesen designed research; H. Band and E. I. Boesen contributed analytic tools; S. S. Rahman, A. E. J. Moffitt, A. J. Trease, K. W. Foster, M. D. Storck, and E. I. Boesen performed research; S. S. Rahman and E. I. Boesen analyzed the data; and S. S. Rahman, H. Band, and E. I. Boesen wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Welling P. A., Weisz O. A. (2010) Sorting it out in endosomes: an emerging concept in renal epithelial cell transport regulation. Physiology (Bethesda) 25, 280–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russo L. M., McKee M., Brown D. (2006) Methyl-β-cyclodextrin induces vasopressin-independent apical accumulation of aquaporin-2 in the isolated, perfused rat kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 291, F246–F253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown D. (2003) The ins and outs of aquaporin-2 trafficking. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 284, F893–F901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouley R., Hawthorn G., Russo L. M., Lin H. Y., Ausiello D. A., Brown D. (2006) Aquaporin 2 (AQP2) and vasopressin type 2 receptor (V2R) endocytosis in kidney epithelial cells: AQP2 is located in ‘endocytosis-resistant’ membrane domains after vasopressin treatment. Biol. Cell 98, 215–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bugaj V., Pochynyuk O., Stockand J. D. (2009) Activation of the epithelial Na+ channel in the collecting duct by vasopressin contributes to water reabsorption. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 297, F1411–F1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butterworth M. B., Edinger R. S., Frizzell R. A., Johnson J. P. (2009) Regulation of the epithelial sodium channel by membrane trafficking. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 296, F10–F24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giménez I., Forbush B. (2003) Short-term stimulation of the renal Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC2) by vasopressin involves phosphorylation and membrane translocation of the protein. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26946–26951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunaratne R., Braucht D. W., Rinschen M. M., Chou C.-L., Hoffert J. D., Pisitkun T., Knepper M. A. (2010) Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis reveals cAMP/vasopressin-dependent signaling pathways in native renal thick ascending limb cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 15653–15658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutig K., Saritas T., Uchida S., Kahl T., Borowski T., Paliege A., Böhlick A., Bleich M., Shan Q., Bachmann S. (2010) Short-term stimulation of the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl- cotransporter by vasopressin involves phosphorylation and membrane translocation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 298, F502–F509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen S., Terris J., Smith C. P., Hediger M. A., Ecelbarger C. A., Knepper M. A. (1996) Cellular and subcellular localization of the vasopressin-regulated urea transporter in rat kidney. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 5495–5500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rieg T., Tang T., Uchida S., Hammond H. K., Fenton R. A., Vallon V. (2013) Adenylyl cyclase 6 enhances NKCC2 expression and mediates vasopressin-induced phosphorylation of NKCC2 and NCC. Am. J. Pathol. 182, 96–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauter D., Fernandes S., Goncalves-Mendes N., Boulkroun S., Bankir L., Loffing J., Bouby N. (2006) Long-term effects of vasopressin on the subcellular localization of ENaC in the renal collecting system. Kidney Int. 69, 1024–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maxfield F. R., McGraw T. E. (2004) Endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant B. D., Donaldson J. G. (2009) Pathways and mechanisms of endocytic recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 597–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George M., Ying G., Rainey M. A., Solomon A., Parikh P. T., Gao Q., Band V., Band H. (2007) Shared as well as distinct roles of EHD proteins revealed by biochemical and functional comparisons in mammalian cells and C. elegans. BMC Cell Biol. 8, 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naslavsky N., Caplan S. (2011) EHD proteins: key conductors of endocytic transport. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 122–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gudmundsson H., Hund T. J., Wright P. J., Kline C. F., Snyder J. S., Qian L., Koval O. M., Cunha S. R., George M., Rainey M. A., Kashef F. E., Dun W., Boyden P. A., Anderson M. E., Band H., Mohler P. J. (2010) EH domain proteins regulate cardiac membrane protein targeting. Circ. Res. 107, 84–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chukkapalli S., Amessou M., Dekhil H., Dilly A. K., Liu Q., Bandyopadhyay S., Thomas R. D., Bejna A., Batist G., Kandouz M. (2014) Ehd3, a regulator of vesicular trafficking, is silenced in gliomas and functions as a tumor suppressor by controlling cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Carcinogenesis 35, 877–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simone L. C., Naslavsky N., Caplan S. (2014) Scratching the surface: actin’ and other roles for the C-terminal Eps15 homology domain protein, EHD2. Histol. Histopathol. 29, 285–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapaport D., Auerbach W., Naslavsky N., Pasmanik-Chor M., Galperin E., Fein A., Caplan S., Joyner A. L., Horowitz M. (2006) Recycling to the plasma membrane is delayed in EHD1 knockout mice. Traffic 7, 52–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curran J., Makara M. A., Little S. C., Musa H., Liu B., Wu X., Polina I., Alecusan J. S., Wright P., Li J., Billman G. E., Boyden P. A., Gyorke S., Band H., Hund T. J., Mohler P. J. (2014) EHD3-dependent endosome pathway regulates cardiac membrane excitability and physiology. Circ. Res. 115, 68–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George M., Rainey M. A., Naramura M., Ying G., Harms D. W., Vitaterna M. H., Doglio L., Crawford S. E., Hess R. A., Band V. (2010) Ehd4 is required to attain normal prepubertal testis size but dispensable for fertility in male mice. Genesis 48, 328–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.George M., Rainey M. A., Naramura M., Foster K. W., Holzapfel M. S., Willoughby L. L., Ying G., Goswami R. M., Gurumurthy C. B., Band V., Satchell S. C., Band H. (2011) Renal thrombotic microangiopathy in mice with combined deletion of endocytic recycling regulators EHD3 and EHD4. PLoS One 6, e17838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. U. S. National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Kidney Systems Biology Project. Accessed October 10, 2016 at: https://hpcwebapps.cit.nih.gov/ESBL/Database/index.html/

- 25.Hasler U., Mordasini D., Bens M., Bianchi M., Cluzeaud F., Rousselot M., Vandewalle A., Féraille E., Martin P.-Y. (2002) Long term regulation of aquaporin-2 expression in vasopressin-responsive renal collecting duct principal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10379–10386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vesey D. A., Qi W., Chen X., Pollock C. A., Johnson D. W. (2009) Isolation and primary culture of human proximal tubule cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 466, 19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinay P., Gougoux A., Lemieux G. (1981) Isolation of a pure suspension of rat proximal tubules. Am. J. Physiol. 241, F403–F411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang J., Lane P. H., Pollock J. S., Carmines P. K. (2009) PKC-dependent superoxide production by the renal medullary thick ascending limb from diabetic rats. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 297, F1220–F1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohan D. E., Padilla E., Hughes A. K. (1993) Endothelin B receptor mediates ET-1 effects on cAMP and PGE2 accumulation in rat IMCD. Am. J. Physiol. 265, F670–F676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nørregaard R., Madsen K., Hansen P. B., Bie P., Thavalingam S., Frøkiær J., Jensen B. L. (2011) COX-2 disruption leads to increased central vasopressin stores and impaired urine concentrating ability in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 301, F1303–F1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park E.-J., Lim J.-S., Jung H. J., Kim E., Han K.-H., Kwon T.-H. (2013) The role of 70-kDa heat shock protein in dDAVP-induced AQP2 trafficking in kidney collecting duct cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 304, F958–F971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J. W., Chou C. L., Knepper M. A. (2015) Deep sequencing in microdissected renal tubules identifies nephron segment–specific transcriptomes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 2669–2677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knepper M. A., Kwon T. H., Nielsen S. (2015) Molecular physiology of water balance. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 1349–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nejsum L. N., Zelenina M., Aperia A., Frøkiaer J., Nielsen S. (2005) Bidirectional regulation of AQP2 trafficking and recycling: involvement of AQP2-S256 phosphorylation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 288, F930–F938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nielsen S., Chou C.-L., Marples D., Christensen E. I., Kishore B. K., Knepper M. A. (1995) Vasopressin increases water permeability of kidney collecting duct by inducing translocation of aquaporin-CD water channels to plasma membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 1013–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noda Y., Sasaki S. (2006) Regulation of aquaporin-2 trafficking and its binding protein complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758, 1117–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tajika Y., Matsuzaki T., Suzuki T., Ablimit A., Aoki T., Hagiwara H., Kuwahara M., Sasaki S., Takata K. (2005) Differential regulation of AQP2 trafficking in endosomes by microtubules and actin filaments. Histochem. Cell Biol. 124, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamma G., Klussmann E., Oehlke J., Krause E., Rosenthal W., Svelto M., Valenti G. (2005) Actin remodeling requires ERM function to facilitate AQP2 apical targeting. J. Cell Sci. 118, 3623–3630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braun A., Pinyol R., Dahlhaus R., Koch D., Fonarev P., Grant B. D., Kessels M. M., Qualmann B. (2005) EHD proteins associate with syndapin I and II and such interactions play a crucial role in endosomal recycling. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3642–3658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grant B. D., Caplan S. (2008) Mechanisms of EHD/RME-1 protein function in endocytic transport. Traffic 9, 2043–2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naslavsky N., Rahajeng J., Sharma M., Jović M., Caplan S. (2006) Interactions between EHD proteins and Rab11-FIP2: a role for EHD3 in early endosomal transport. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 163–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nedvetsky P. I., Stefan E., Frische S., Santamaria K., Wiesner B., Valenti G., Hammer J. A. III, Nielsen S., Goldenring J. R., Rosenthal W., Klussmann E. (2007) A role of myosin Vb and Rab11-FIP2 in the aquaporin-2 shuttle. Traffic 8, 110–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chou C. L., Ma T., Yang B., Knepper M. A., Verkman A. S. (1998) Fourfold reduction of water permeability in inner medullary collecting duct of aquaporin-4 knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. 274, C549–C554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vagin O., Kraut J. A., Sachs G. (2009) Role of N-glycosylation in trafficking of apical membrane proteins in epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 296, F459–F469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hendriks G., Koudijs M., van Balkom B. W., Oorschot V., Klumperman J., Deen P. M., van der Sluijs P. (2004) Glycosylation is important for cell surface expression of the water channel aquaporin-2 but is not essential for tetramerization in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 2975–2983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arnspang E. C., Sundbye S., Nelson W. J., Nejsum L. N. (2013) Aquaporin-3 and aquaporin-4 are sorted differently and separately in the trans-Golgi network. PLoS One 8, e73977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ho H. T., Chung S. K., Law J. W., Ko B. C., Tam S. C., Brooks H. L., Knepper M. A., Chung S. S. (2000) Aldose reductase-deficient mice develop nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5840–5846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao Y., Stuart D., Pollock J. S., Takahishi T., Kohan D. E. (2016) Collecting duct-specific knockout of nitric oxide synthase 3 impairs water excretion in a sex-dependent manner. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 311, F1074–F1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adrogué H. J., Madias N. E. (2000) Hypernatremia. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 1493–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gudmundsson H., Curran J., Kashef F., Snyder J. S., Smith S. A., Vargas-Pinto P., Bonilla I. M., Weiss R. M., Anderson M. E., Binkley P., Felder R. B., Carnes C. A., Band H., Hund T. J., Mohler P. J. (2012) Differential regulation of EHD3 in human and mammalian heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 52, 1183–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]