Abstract

High-resolution magic angle spinning (HRMAS) magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) is a powerful method for gaining insight into the physiological and pathological processes of cellular metabolism. Given its ability to obtain high resolution spectra of non-liquid biological samples, while preserving tissue architecture for subsequent histopathological analysis, the technique has become invaluable for biochemical and biomedical studies. Using HRMAS MRS, alterations in measured metabolites, metabolic ratios, and metabolomic profiles present the possibility to improve identification and prognostication of various diseases and decipher the metabolomic impact of drug therapies. In this review, we evaluate HRMAS MRS results on human tissue specimens from malignancies and non-localized diseases reported in the literature since the inception of the technique in 1996. We present the diverse applications of the technique in understanding pathological processes of different anatomical origins, correlations with in vivo imaging, effectiveness of therapies, and progress in the HRMAS methodology.

Keywords: metabolomics, high-resolution magic angle spinning (HRMAS), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), human tissue

Graphical Abstract

High resolution magic angle spinning (HRMAS) magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) is a method which enhances resolution for non-liquid biological samples. Since its introduction in 1996, HRMAS has been used in a wide variety of biomedical and biochemical studies and is one of the major techniques used in metabolomic analysis. In this review, HRMAS results on human tissue malignancies and non-localized diseases are evaluated, with discussions of applications for understanding pathological processes, correlations with in vivo imaging, therapy effectiveness, and methodology progress.

Introduction

The utility of magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) as a medical diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic evaluation tool for a wide range of diseases has been well investigated. MRS, particularly high-resolution magic angle spinning (HRMAS) MRS, has demonstrated its ability for direct measurement of non-liquid biological tissue to obtain valuable insight into cellular metabolism of physiological and pathological processes of human diseases, as well as into experimental models of animals and cell-lines of these medical conditions.

In this article, we aim to comprehensively review HRMAS MRS for its applications in ex vivo studies of diseased human tissue specimens published prior to the end of 2016. Hereinafter, we narrowly define human studies as direct HRMAS MRS measurements of human tissue specimens, not including animal and cell-line studies of human disease models, as they were reviewed in a separate article1.

HRMAS MRS observable tissue spectra present mostly cellular metabolites and mobile lipids. Metabolites are the signatures of biochemical pathways, through which the processes of cellular carbohydrate, protein, lipid, amino acid and xenobiotic metabolism may be probed. The ability of MRS to explore the metabolic status can help elucidate the physiological and pathological transformations accompanying various medical conditions; it can provide a detailed account of metabolic mechanisms at cellular levels2–4. Review of the published HRMAS MRS studies on human disease emphasizes the utility of the technique especially in understanding human malignancies. Cancer presents identifiable lesions, which enables clear comparison of metabolites from affected and not affected tissue from the same patient. For non-malignant medical conditions, metabolite investigation is more complicated. Disease and control tissues must be obtained from different individuals, presenting bio-variation as a confounding factor. Therefore, the large body of HRMAS MRS research is skewed towards cancer, but we will balance our presentation with critical reviews of other non-localized diseases.

Applications of HRMAS MRS on studies of human malignant diseases

Publications of HRMAS MRS human studies on cancers revealed areas of research emphases that reflect either the prevalence of diseases seen in clinic or the technical advancement achieved with clinical MRS. This review analyzed over 100 studies using HRMAS MRS, including brain tumors (41 papers), breast cancer (21), prostate cancer (19), cervical cancer (9), gastrointestinal tumors (9), lung cancer (5) and renal cancer (4). Cancers are highly variable as far as patient prognostication is concerned. The major aims of these studies, in addition to providing metabolic markers for disease detection and diagnosis, were centered on identification of disease aggressiveness and their response to systemic therapies.

Breast and prostate cancers, as the most frequently diagnosed cancers respectively for women and men, respectively, with 252,710 and 161,360 estimated new cases and accounting for 40,610 and 26,730 estimated deaths in the U.S. in 2017 alone5, have attracted the most attention in research. On the other hand, although tumors of the brain and central nervous system might only present 23,800 new cases and account for 16,700 deaths5, two specific characteristics of the field encouraged researchers to focus on these malignancies: the unparalleled advancement of brain MR techniques (imaging, MRI; functional imaging, fMRI, and MRS) and the vast number of clinical studies reported in the area, due mostly to the relative tissue magnetic susceptibility homogeneity, and minimal respiratory and cardiac motion effects in the brain.

Brain tumors

To structure a large body of publications in this area6–52 into a differentiated review, we will divide this section into three focuses: the correlations between in vivo and ex vivo HRMAS MRS, classification of adult and pediatric CNS tumors, and the relationships between metabolites and histopathological tissue properties. As “brain tumors” refer to a large class of neoplasia including both malignant and non-malignant lesions, we aimed to put the different metabolic findings into the context of the pathologic grading (I–IV) according to the 2016 WHO brain tumor classification53, to reflect the tumor differentiation levels. As the most frequent human brain tumor, most of the research was targeted at gliomas and their subtypes, e.g. astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas, with the pediatric medulloblastoma also the focus of several studies.

In vivo and ex vivo correlations

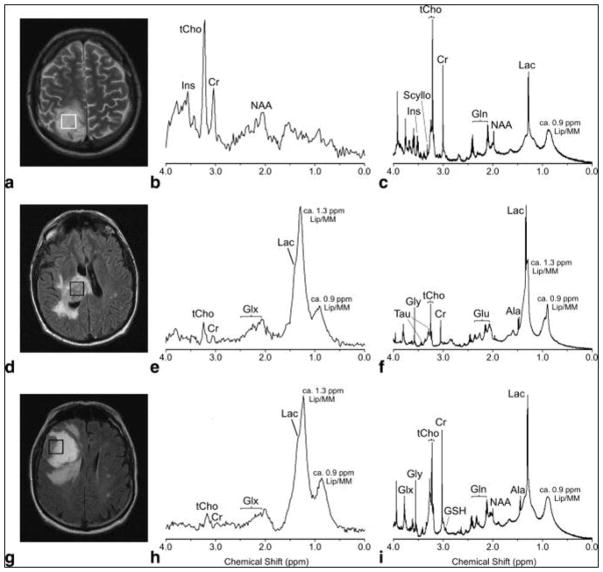

While clinical MR investigations on brain tumors have inspired studies of ex vivo HRMAS MRS of tissue specimens to reveal tumor type-specific metabolic structures and pathways, the most significant value of such ex vivo tissue analyses is in improving interpretation of different tumor types, grades, and progression potential for in vivo MRS. A study of 17 human astrocytomas (4 grade II, 1 grade III and 12 grade IV) has shown spectral similarities between in vivo and ex vivo results (Figure 1), and highly significant correlations were found for 8 out of the 13 measured metabolite concentrations, including Creatine (Cr), Glutmate (Glu), Glutamine (Gln), myo-inositol (myo-Ino), N-acetylaspartate (NAA), scyllo-inositol (scy-Ino), total choline (tCho), Glycerophosphocholine (GPC) and Phosphocholine (PCho)) and Lipid/Macromolecule (Lip/MM)26. Similarities between in vivo and ex vivo MRS have also been reported for heterogeneous primary and secondary glioblastomas (GBM)19, as well as for hemangiopericytoma and meningiomas, two less heterogeneous tumor types31.

Figure 1.

In vivo PRESS TE 30 msec spectra (b, e, h) and their equivalent ex vivo HRMAS presaturation spectra (c, f, i) from a histopathologically verified astrocytoma grade II (a–c) and glioblastoma (d–f) showing unimodal variation of the grayscale pixel values in the voxel placement areas (a,d), and a histologically verified glioblastoma with multimodal variation of the grayscale pixel values (g–i). Major peaks of the metabolites discussed have been labeled, but for clarity not all metabolites are labeled in each spectrum (Ala, alanine; Cr, creatine; Gln, glutamine; Glu, glutamate; Glx, [Gln + Glu]; Gly, glycine; Ins, myo-inositol; Lac, lactate; Lip/MM, lipids/macromolecules; Scyllo, scyllo-inositol; Tau, taurine; tCho, total cholines)26.

However, when connecting ex vivo HRMAS with in vivo MRS results, the major difference between the two spectra, due partially to the magnetic field strength difference and the application of HRMAS in the ex vivo measurements, needs to be considered, particularly when concerning the overlap among metabolite signals in the in vivo MRS. For instance, in the last mentioned hemangiopericytoma and meningiomas study, mannitol – a medication used to reduce brain pressure – presented one peak in the 3T in vivo spectrum at 3.8 ppm. However, when measured ex vivo at 9.4T, the HRMAS spectrum showed multiple peaks between 3.6 and 4.0 ppm. This phenomenon is common for overlapping signals of various metabolites, such as for GPC, PCho, and choline (Cho), and Glu and Gln, which leads the former to be assigned as total choline (tCho = GPC+PCho+Cho), and the latter as Glx (Glu+Gln) for in vivo MRS reports26.

Differentiations among individual metabolites can be very important for tumor identification as noted in a comparative study between grade II astrocytomas (n=10) and GBMs (n=48), where PCho is increased in grade II astrocytomas, while GBMs showed increased levels of GPC. In addition, different amounts of GPC were seen to significantly separate primary GBMs from secondary GBMs (p<0.001). Therefore, accurate differentiations between PCho and GPC, rather than considering tCho collectively, may make it possible to distinguish between grade II astrocytomas and GBM and within the GBM subtype40.

In addition to metabolite overlaps, the detection of certain metabolites can also be field strength- and sensitivity-dependent. For instance, alanine (Ala) was detectable in an HRMAS spectrum at 9.4T but not at 3T during in vivo MRS31. Despite these technical challenges, the trend of increasing magnetic field strength of clinical MRI scanners means the clinical translation of HRMAS MRS findings is increasingly possible. Currently, HRMAS MRS is highly suitable to tackle another task that presents challenges in the clinical setting: analysis of tissue metabolic structures to characterize and distinguish brain tumor types and grades.

Differentiations of tumor types and grades for adult and pediatric brain cancer

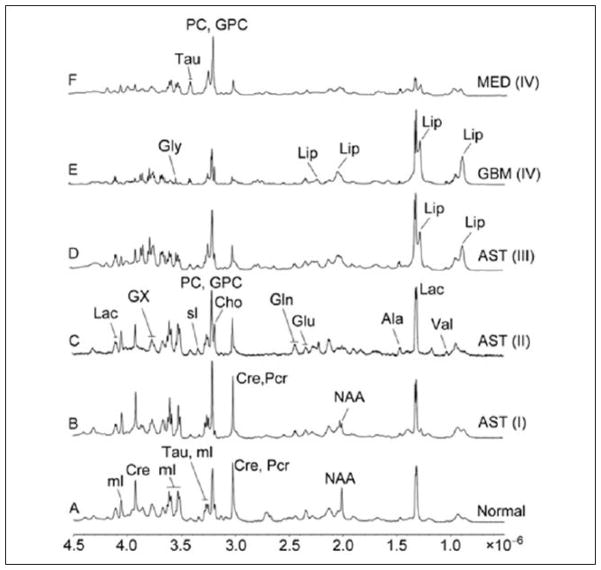

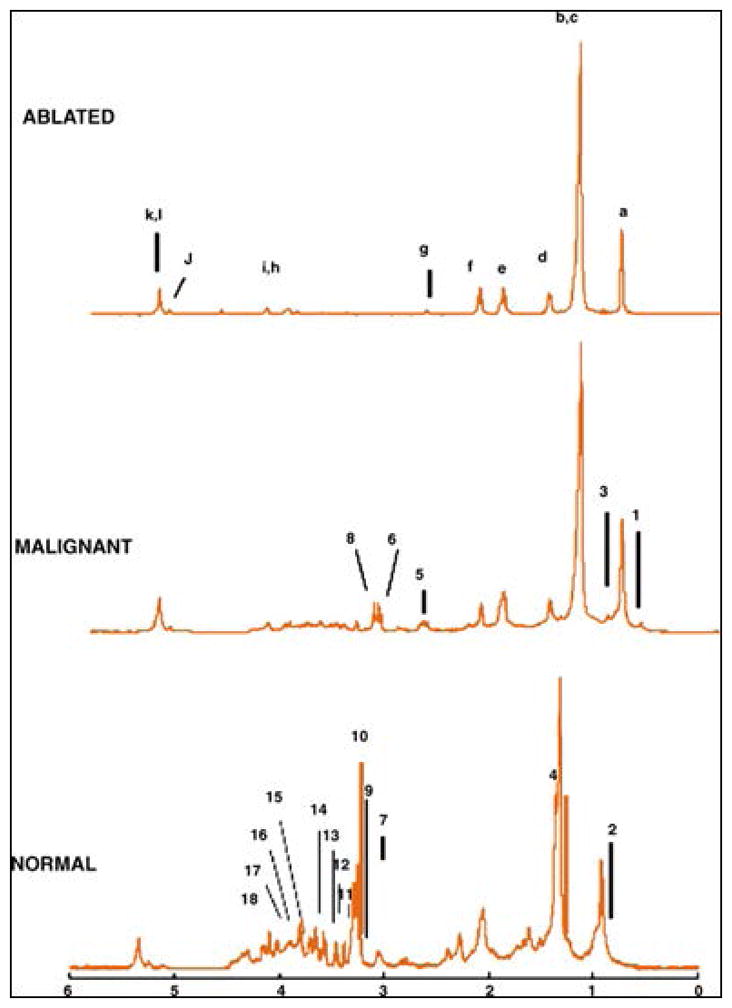

Due to significant clinical impact, gliomas have been a primary focus of research in the recent years. In 2010, an HRMAS MRS study of 30 neuroepithelial brain cancer specimens showed that certain metabolic changes are directly or inversely related to tumor grades (Figure 2). Specifically, in high grade tumors (grade III–IV), taurine (Tau), glycine (Gly) and aspartate (Asp) increases and Cr, myo-Ino, GPC, PCho decreases were observed. Furthermore, lipids and Ala were higher in grade II and III astrocytomas than in grade I. For grade III astrocytoma, NAA, Cr, myo-Ino (all p<0.01) were lower than in grades I and II astrocytomas, whereas Gly (p<0.05) was higher. GBM spectra were mostly characterized by lower Lac, Cr, and myo-Ino (all p<0.05) than in grades I–III astrocytomas. To distinguish grade III astrocytomas from GBM, GPC (n.s.), Cho (n.s.), lactate (Lac) (p<0.05) and Cr (p<0.001) are found in higher levels in the former. In contrast, myo-Ino (p<0.001) and PCho (n.s.) are lower in grade III. The changes in the following five metabolites were in agreement with other in vivo studies: Gly, NAA, Lac, Cr, and myo-Ino8. A summarizing table of reported brain tumor HRMAS MRS measurable metabolite changes from this and other reviewed references will be provided later in this section.

Figure 2.

HR-MAS 1H NMR spectra of six brain specimens acquired from CPMG pulse sequence at a spin rate of 2 kHz. (A) Normal Tissue, (B) Astrocytoma (grade I), (C) Astrocytoma (grade II), (D) Astrocytoma, (E) Glioblastoma (grade IV), (F) Medulloblastoma (grade IV)8.

In another study, metabolic differences between grade II astrocytomas (n=10) and GBMs (n=48) were investigated using multivariate and principal component analysis (PCA). GBMs showed increased lipids and decreased GPC levels than grade II astrocytomas, which accords with previous research, in addition to harboring higher PCho and Gly and lower myo-Ino. The prediction model showed a sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 88% in discriminating grade II from GBMs. As previously described, primary and secondary GBMs can be differentiated by PCho, with recurrent GBM (n=17 out of the 48) having lower amounts of this metabolite40.

Gliomas tend to not only recur but also transform to a higher grade, so biomarkers that can identify these types can be crucial in the clinic. Differentiation between grade II gliomas that underwent malignant transformation to a higher grade vs. those that remained grade II was evaluated for 53 recurrent grade II gliomas. Myo-Ino levels were 56% lower in gliomas that underwent progression than those that remained low grade, while 2-hydroxyglutarate (2HG) (2.24 – 2.30 ppm), hyp-Tau (2.62–2.69 ppm), and Cho (3.21–3.29 ppm) had up to 120%, 137%, and 83% higher levels in the progressive gliomas. Higher levels in this group were also detected for lipids, gluthathione (GSH) and Ala. Particularly, myo-Ino was proposed as a key metabolite of discriminative strength. Combined with other presented metabolic information, it assisted in reaching 96% accuracy in identifying tumor progression10.

Later in 2014, a larger study with 254 samples from 126 patients with either primary or secondary and new or recurrent gliomas was reported. Comparison between primary GBMs (n= 101) and secondary GBMs (ntotal=33, grade II → grade IV: 19, grade III → IV: 14) found that tCho, 2HG and Asp were significantly higher in the grade II → IV cases than in primary GBMs (all p<0.005). In addition, classification models could separate primary from secondary GBMs with very high accuracy, scoring 94% between grade II → IV and 96% between grade III → IV, with 2HG being the most important parameter. Separating these types is vital since GBMs with transformative potential need more aggressive treatment than de novo GBMs46–48,51. Primary grade II and grade III astrocytomas could be separated from primary GBMs with higher 2HG levels for the astrocytomas. Additionally, a higher myo-Ino/tCho ratio and a lower total glutathione (tGSH = reduced glutathione + disulfide form) level were present in grade II tumors vs. GBMs, and higher levels of tCho, 2HG, NAA, Cr/phosphocreatine (PCr) ratio existed for the grade III to enable separation from the GBMs. Astrocytomas themselves could be separated with a higher myo-Ino/tCho ratio, together with lower levels of Gly and phosphoethanolamine (PE), distinguishing primary grade II from primary grade III anaplastic astrocytomas with 73% accuracy15.

The tumor-promoting onco-metabolite 2HG52, as an important discrimination marker for gliomas, was found to be significantly correlated with a number of other metabolites in a 2009 study. Positive correlations were reported for fifteen metabolites [PCho, GPC, tCho, Cr, phosphocreatine (PCr), PE, GSH, Glu, Gln, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), Ala, Gly, betaine (Bet), hypo-taurine (hyp-Tau), and Lac], and 2HG was negatively correlated with the myo-Ino/tCho ratio (all p<0.05). Choline-containing compounds (ChoCC) are widely used as an in vivo MRS marker for tumor presence and increased levels of many other metabolites, so 2HG could be an added marker. It could also contribute additional prognostic information in the clinical setting. For example, glioma patients with an IDH1 or IDH2 gene mutation present more favorable prognoses (higher 5-year survival rate) and accumulate higher amounts of 2HG52. Considering the resonance overlaps between 2HG and other metabolites at clinical field strengths14, ex vivo MRS identification of this relationship is critical. Positively, other findings suggest that 2HG can be identified clinically by using 1D spectral-editing with a localized 2D correlation7.

HRMAS MRS results have also been supported by genomic analyses. In a study of 9 grade II, 6 grade III, 8 grade IV astrocytomas and 3 normal tissue specimens, as expected, results found that NAA and GABA, two important neuronal markers, were decreased in glioma tissues as compared to normal tissue. Using higher GPC/tCho ratio in low grade (II) tumors, the latter can be correctly separated from high grade (III and IV) tumors in 22 out of 23 cases (95% accuracy), suggesting GPC as the main component in low grade tumors and PCho as a signature Cho derivate in high grade glioma. Genomic results further supported the purported rise in PCho by demonstrating an increase in the gene expressions of choline kinase α and phospholipase C29.

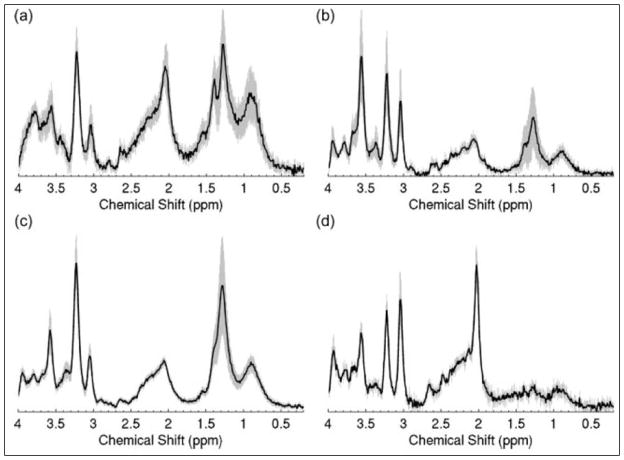

Whereas most HRMAS MRS research on malignant disease focuses on adults, research on brain malignancies extends to pediatric studies. One of the most common malignant CNS tumors in children is the medulloblastoma49,50, which is a high grade (WHO grade IV) tumor with an overall poor prognosis. A cohort of 35 cerebellar childhood tumors (18 medulloblastomas, 12 pilocytic astrocytomas and 5 ependymomas), were studied, with separation possible between all three tumor types. High levels of PCho and Glu as well as low Gln levels characterized medulloblastomas. These tumors also had high Tau, MM/Lipids and Ala levels. Alterations in NAA, Cr and myo-Ino can be used to distinguish ependymomas from pilocytic astrocytomas, with NAA detectable in astrocytomas, but not in ependymomas or medulloblastomas. Higher Cr levels are found in ependymomas (Figure 3)12.

Figure 3.

Mean spectra for (a) astrocytomas (n=12), (b) ependymomas (n=4), (c) medulloblastomas (n=18) and (d) controls (n=4) with 95% confidence intervals indicated by the shaded region12.

In a follow-up study, Gly was validated as an in vivo marker for high grade childhood brain tumors. Looking at 15 tissue samples (high grade: 8 medulloblastomas, 1 anaplastic ependymoma; low grade: 5 pilocytotic astrocytomas, 1 ependymoma), the study showed a significant relation between the normalized Gly concentration measured with short echo time for in vivo MRS and the Gly levels of the corresponding samples examined with HRMAS (p<0.05). High grade tumors showed higher Gly (p<0.05) when compared to the low grade group13.

Results from analyses of 29 childhood brain tumors with PCA and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) agreed that different tumor types possess clear metabolomic fingerprints of significant changes for glial tumors (10 pilocytic astrocytomas and 2 ependymomas) vs. primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) (9 medulloblastomas, 7 neuroblastomas and 1 supratentorial PNET) (p<0.05)41. Glial tumors displayed higher levels of Cr and Glu and lower levels of Tau, Cho, PCho and PE when compared to PNETs, with 90% classification accuracy. Within the group of PNETs, differentiation of just medulloblastomas and neuroblastomas was feasible with 94% accuracy, as medulloblastomas show higher Cr, Gly, Glu, PCho and scy-Ino (p<0.05)41.

Metabolites and histopathological tissue properties

In addition to distinguishing among different brain tumor types and grades, HRMAS MRS has also been used to measure correlations between tissue histopathological features and metabolic properties.

Micro-heterogeneity of brain tumors is common in neuropathology, especially in high grade tumors. It complicates tumor biopsy grading and hinders correlations between metabolic changes and pathological features. Tissue HRMAS MRS can help uncover these correlations. In 2000, very soon after the invention of intact tissue HRMAS MRS, this capability was demonstrated by a study of multiple tissue specimens obtained from a 44-year old GBM patient. The specimens were first measured by ex vivo HRMAS MRS and then underwent quantitative histopathological analysis. Highly significant positive correlations between the amount of necrosis in the specimen and Lac (p<0.032, R2= 0.939) as well as lipids (p<0.02, R2= 0.961) were found. Additionally, the amount of glioma was clearly related to an increasing PCho/Cho ratio (p<0.033, R2= 0.936)45. In addition to uncovering relationships between metabolites and brain tumor pathologies, this study, for the first time, demonstrated the critical advantage of HRMAS MRS in enabling both high resolution tissue metabolic quantifications and histopathology evaluations of the same tissue specimen. This unique capability of HRMAS MRS proved to be critical for many human studies, such as those of PCa to be reviewed later.

Apoptosis plays a major role in checking tumor growth and development. As new drugs aim to activate apoptotic pathways within the tumor cells to control their growth, a study included 41 brain tumor biopsies of grades II (n=8), III (n=3) and IV (n=30) astrocytomas revealed Tau as a potential marker of apoptosis in glioma. Tau positively and significantly correlated with apoptotic terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL)-stained nuclei in non-necrotic (p=0.003, R=0.727), as well as in necrotic (p=0.0005, R=0.626) biopsies. Additionally, Lip/MM in the regions of 1.3 ppm (p<0.005, R=0.703) and 2.8 ppm (p<0.005, R=0.705) were positively associated with the number of apoptotic cells in non-necrotic tissue samples. These markers may help to monitor treatment response in clinic25.

In addition to necrosis and apoptosis, identification of other common histopathological features is important for disease evaluation and treatment monitoring. Results from studies of 52 patients of different types of glial tumors showed metabolite differences between tissue with necrosis, high cellularity, or cancer infiltration. The best separations among the three groups were enabled by tCho/NAA and Lip/NAA ratios, with the latter being especially useful in the differentiation between necrotic and highly cellular tissue. The necrotic tissue was characterized by negligible NAA and tCho but very high quantities of lipids, whereas highly cellular tissue showed low NAA and lipids but great amounts of tCho, a marker of cell membrane turnover33. Furthermore, 2HG was found to be positively correlated with mitotic activity (measured by the MIB-1 index), cellular density and relative tumor content within the tissue sample14.

In 2012, an ex vivo 1H and 31P HRMAS MRS study of 33 brain tumor biopsies to identify metabolites, pH values, and their correlations with histopathological features was reported. Percentage of unaffected brain tissue revealed high associations with NAA, Glycerophosphorylethanolamine (GPE), GABA, Cr (all p<0.01) and Glu (p<0.05). In contrast, the percentage of necrosis was negatively correlated with Cr, GABA, Gln, Ade (all p<0.01) and positively with fatty acids (FA) (p<0.01). The metabolites Gln, PE + PCho, FA and the Glu/Gln and Cho/Cr ratios were significantly related to the percentage of tumor cells. GPE, Cr, NAA and Ade (all p<0.01) were all found to be negatively correlated with tissue pH. However, different correlations were found within only GBMs (n=19). The amount of cancerous tissue was positively linked to GSH, PC and myo-Ino levels (all p<0.05). In contrast, FA was negatively associated (p<0.05). Amount of necrosis in the GBM samples and amount of PC, Lac, Glu, GSH, and myo-Ino were inversely correlated (all p<0.05)17.

To assist readers in navigating through the large volume of HRMAS MRS studies on human brain tumors, we have summarized literature data in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected papers on brain tumors with metabolic findings highlighted, 1998–2015. Additional abbreviations: His, histidine; Lys, lysine; Thr, threonine; Val, valine.

| Year | Author | Samples investigated | Metabolites increased (in first named entity vs. second) | Metabolites decreased (in first named entity vs. second) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Cheng9 | Astrocytoma (low grade →high grade) | Cho/Cr | NAA |

| 2007 | Tzika38 | Malignant glioma % | PCho/tCr | |

| Necrosis % | Lip/tCr | |||

| 2008 | Andronesi6 | High grade tumors, metastases | Lip, FA | |

| Metastases (breast) | GPC | |||

| Metastases (general) | PCho, PCho/GPC | |||

| Davies12 | Pediatric pilocytic astrocytoma | FA, isoleucine, leucine, Val, NAA, GABA, Glu | Cr, myo-Ino, Tau, ChoCC, | |

| Pediatric ependymoma | myo-Ino, Cr | NAA, Tau | ||

| Erb16 | High grade oligodendroglioma vs. low grade oligodendroglioma | Ala, Val | Proline, Glu, Gln, GABA, NAA | |

| Monleon22 | High grade meningioma | PCho, PE, GSH | ||

| Meningioma (general) | No NAA, low FA | |||

| Opstad24 | Necrosis % in GBMs | Lip/MM | ||

| 2009 | Davies13 | High grade pediatric brain tumors | Gly | |

| Opstad25 | Apoptotic cell density of tumor | Tau (independent of necrosis), Lip/MM (in non-necrotic tissue) | ||

| Righi29 | High grade gliomas | PCho, PCho/tCr | ||

| Low grade gliomas | GPC, PCho/tCr | |||

| Gliomas vs. healthy | ChoCC | |||

| Wilson41 | Pediatric glioma vs. PNETs | Cr, Gln | Tau, PE, PCho, Cho | |

| Pediatric medulloblastoma vs. pediatric meuroblastoma | Cr, Gln, PCho, Gly, scy-Ino | |||

| 2010 | Cuellar-Bana11 | Medulloblastoma (general) | Tau, GPC, PCho, Cho | NAA, FA, Glu |

| Pilocytic astrocytoma (general) | FA | |||

| Ependymoma (general) | myo-Ino | |||

| Monleon23 | Atypical meningioma | Lac | ||

| Righi30 | Tumors vs. healthy | Gly | ||

| GBM vs. low grade tumors | Gly | |||

| GBM vs. metastases | Gly/myo-Ino | |||

| Meningioma vs. low grade tumors | Gly/myo-Ino | |||

| Wright43 | GBM | Cr, Gly, Gln, hyp-Tau | ||

| Astrocytoma II vs. GBM | myo-Ino | Ala | ||

| Astrocytoma II vs. Metastasis | Gln, myo-Ino | PE | ||

| Astro II vs. meningioma | Cr, GPC, His, myo-Ino, scy-Ino | Ala, Glu, GSH, PE | ||

| Astro III vs. metastasis | Hyp-Tau | |||

| Astro III vs. meningioma | GPC, myo-Ino | GSH, Lys | ||

| GBM vs. metastasis | Cr, Gln, Gly, hyp-Tau | |||

| GBM vs. meningioma | Asp, Cr, GPC, His, myo-Ino, NAA, scy-Ino | Ala, Glu, GSH, Isoleucine, Tau, Val | ||

| Metastasis vs. meningioma | Cr | Ala, Glu, Gln, Lac | ||

| 2011 | Chen8 | Increasing astrocytoma tumor grade | Lip, Lac, Ala, scy-Ino | NAA, myo-Ino, Cr |

| Astrocytoma II, III vs. I | Lip, Ala | NAA, myo-Ino, Cr, PCho, GPC | ||

| GBM (general) | Gly, Lip | NAA, PCho, GPC | ||

| GBM vs. Astrocytoma I – III | Lac, Cr, myo-Ino | |||

| GBM vs. astrocytoma I | Lip, Tau | Lac, Cr | ||

| Astrocytoma III vs. I, II | Gly, Lac/Cr, myo-Ino/Cr, Gly/Cr, scy-Ino/Cr, Ala/Cr | NAA, Cr, myo-Ino | ||

| Medulloblastoma (general) | Tau, PCho, GPC | Lac | ||

| Medulloblastoma vs. astrocytoma II – IV | myo-Ino, Tau, Gly, PC, GPC, Asp | Lac, Cr | ||

| Astrocytoma I – II vs. III | NAA, Cr, GPC, myo-Ino | Lac, PCho | ||

| Astrocytoma I – II vs. GBM | Lac, Cr, Cho, GPC | Gly, PCho | ||

| Astrocytoma III vs. GBM | Lac, Cr, Cho, GPC | myo-Ino, PCho | ||

| Croitor33 | Border tissue/cancer infiltration vs. high cellularity or necrosis | NAA | Lip/Cr | |

| High cellularity vs. border tissue/cancer infiltration or necrosis | ChoCC/Cr | Lip/Cr, NAA/Cr | ||

| Necrosis vs. border tissue/cancer infiltration or high cellularity | Lip/Cr | Cho/Cr | ||

| McKnight20 | Astrocytoma II vs. III | PCho | ||

| Ki-67 | GPC | |||

| Cell density | PCho, tCho | |||

| 2012 | Constantin10 | Glioma II → higher grade | 2HG, hyp-Tau, Cho, Lip, GSH, Ala | myo-Ino |

| Secondary Glioma III vs. secondary IV | changes in hyp-Tau, GSH, Ala | |||

| Secondary Glioma III vs. recurrent Glioma II | changes in hyp-Tau, GSH, Cho, myo-Ino, 2HG | |||

| Likelihood of malignant transformation in recurrent low grade gliomas | Increasing 2HG levels | |||

| Elkhaled14 | Metabolites (related to malignancy) positively correlating with 2HG | Asp, GABA, Thr, hyp-Tau, Cr, PCr, Bet, Gly, Lac, GSH, PE, Glu, Gln | ||

| Negatively correlating with 2HG | myo-Ino/tCho | |||

| Righi31 | Hemangiopericytoma vs. meningioma | myo-Ino/Glu, Glc/Glu, GSH/Glu | Cr/Glu, Gln/Glu, Ala/Glu, Gly/Glu, ChoCC/Glu, Ala | |

| 2013 | Sjobakk35 | Necrosis in tissue | Lip | |

| Brain metastases from melanoma vs. other brain metastases | GPC | |||

| Vettukattil40 | Astrocytoma II vs. GBM | GPC, myo-Ino | PCho, Gly, Lip | |

| Non-recurrent vs. recurrent GBM | PCho | |||

| % necrosis | Lip, Lac | |||

| Recurrent vs. non-recurrent GBM | GPC, myo-Ino, Cr | Gly | ||

| 2014 | Elkhaled15 | Transformation from Glioma grades II to III or IV | 2HG, tGSH | myo-Ino/tCho |

| Primary glioma grade III vs. secondary | Cho, Gly, PC/GPC | |||

| Transformation to IV | PC/GPC | |||

| High malignancy regions | tCho | myo-Ino/tCho, NAA, Cr/PCr | ||

| 2015 | Kohe18 | Retinoblastoma level of differentiation | Tau | |

| Level of necrosis | Lip | Tau, hyp-Tau, Cr, PCho, tCho | ||

| Retrolaminar optic nerve invasion | tCho, PCho |

Breast cancer

Studies of BrCa have shown HRMAS MRS as a promising tool in cancer diagnosis, treatment monitoring, and prediction of prognosis54–73. Here, we will focus our review on four interesting aspects: metabolic differences between malignant and non-malignant breast tissues, correlations between metabolites and pathologic features of BrCa, predictions of the response to the clinical treatment and the prognosis of BrCa with metabolic information, and the relationships of metabolite, gene, and protein information.

Metabolic differences between malignant and non-malignant breast tissues

Many conventional diagnostic tools have been developed and applied in clinical practice for BrCa, including mammography, ultrasound, and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI to provide differential diagnosis for this complex disease. Several studies of BrCa using both in vivo and ex vivo MR spectroscopy have shown that malignant lesions from the breast have increased levels of ChoCC74,75. Studies on extracts of BrCa tissue have reported elevated levels of PC in cancerous tissue compared with non-involved tissue76–78 and benign breast lesions79.

In 2006, the relative intensities of GPC, PC and Cho were examined by HRMAS MRS measured from the microscopy-confirmed cancerous (n=76) and non-involved samples (n=9)55. Consistent with previous findings, intensity ratios of PC/Cho were higher in tumor samples than in non-involved tissue (p=0.005), and GPC/PC and GPC/Cho were lower (p<0.001 and p=0.013). Classification of tumor and non-involved samples based on the relative intensities of the different ChoCC showed high sensitivity and specificity, 82% and 100%, respectively.

A study of 31 breast tissue samples (13 cancers and 18 non-cancers) again showed that in cancer cells, ChoCC, particularly PC, increased, while introducing the novel finding of increased Tau (p<0.009) and decreased Asp (p<0.002)59. The low sensitivity and high specificity of the prediction of the cancer status were 69% and 94%, respectively.

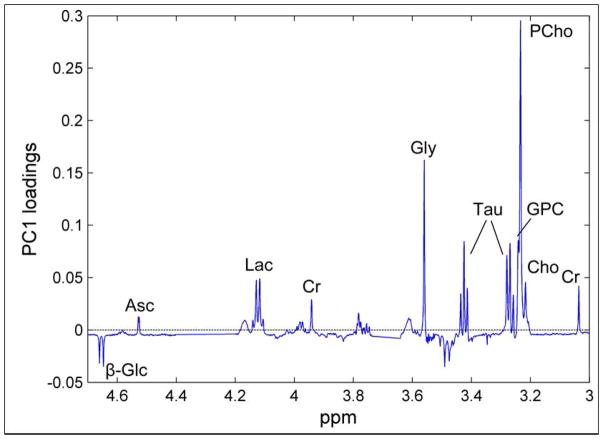

HRMAS MRS observable metabolites discriminated between BrCa and non-involved adjacent tissue in 328 tissue samples (263 BrCa samples and 65 non-involved samples) from 228 BrCa patients. BrCa samples were shown to contain higher levels of ChoCC and Tau, in addition to ascorbate, Lac, Cr, and Gly, and lower levels of glucose (Glc) compared to non-involved tissue (Figure 4). The results emphasized ChoCC as primary biomarkers for tumor presence, given that BrCa and noninvolved tissue could be accurately discriminated with high sensitivity (91%) and specificity (93%) (p<0.001). This finding may have the potential to guide resection margins during BrCa surgery to reduce risk of local recurrence and re-surgery66.

Figure 4.

The corresponding loading profile of first principal component (PC1), explaining 40.1% of the total variation of the data. β-Glc, β-glucose; Asc, ascorbate; Lac, lactate; Cr, Cr; Gly, glycine; Tau, Taurine; GPC, glycerophosphocholine; PCho, phosphocholine; Cho, free choline66.

Correlation between metabolites and pathologic features of breast cancer

Histopathological (tumor size, grade, and axillary lymph node status) and immuno-histochemical [steroid hormone receptor, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and cellular proliferation marker Ki-67] evaluation of BrCa specimens is the gold standard for patient treatment planning. Studies have focused on correlations between metabolic information measured from the ex vivo HRMAS MRS method and the clinical pathological results. A study of 103 samples (85 BrCa and 18 non-involved tissues) from 85 BrCa patients showed that tumors >2.0 cm were found to have significant higher levels of Gly (p=0.03) and Cho (p=0.04) than tumors ≤2.0 cm (Student’s t-test). While no significant metabolite differences were found in samples between lymph node-positive and -negative patients (Student’s t-test), a trend of increased myo-Ino in samples from node-positive patients (p=0.08) was seen55. Separately, analysis of 36 core needle biopsy samples showed BrCa of high histological grade presenting higher PC/Cr than low histological grade BrCa (p=0.04). Higher tCho concentrations have been detected in high-grade BrCa, indicating a correlation between Cho phospholipid metabolism and tumor malignancy and aggressiveness61.

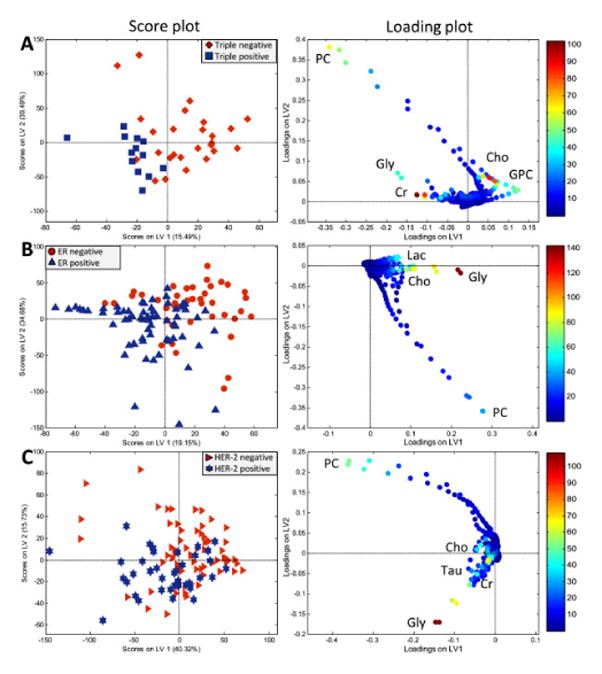

As is known in the BrCa clinic, estrogen receptor (ER) positive and progesterone receptor (PR) positive tumors present better prognosis, while HER2 overexpression tumors are associated with worse prognosis. To study the relationship between metabolites and these hormone and growth receptors, a study measured 36 ER-negative BrCa samples and found higher Cho than in ER-positive samples (p=0.03). PR-negative cancers also showed higher concentrations of Cho, as well as higher Cr and Tau, than those of PR-positive cancers (p=0.01, p=0.02, and p=0.02, respectively). Concentrations of Tau, scy-Ino, and myo-Ino of HER2-positive BrCa were significantly higher than those of the HER2-negative cancers (p=0.01, p=0.03, and p=0.01, respectively). Triple negative BrCas (TNBC) (ER-negative, PR-negative, and HER2-negative cancers) showed higher Cho concentrations and higher values of Cho/Cr and tCho/Cr than those of non-triple negative cancers. BrCa with high Ki-67 levels showed higher concentrations of tCho and PC, and higher values of PC/Cr than those of BrCa with low Ki-67 (p=0.01)61. These high concentrations of ChoCC in BrCa tissues may be a consequence of overexpression and changes in the levels of choline kinase activity in response to demands from the cell for increased phospholipid synthesis80,81. Down-regulation of choline kinase alpha (CHKA), the gene regulating the conversion of Cho to PC, has been shown to decrease cell proliferation, and to increase the effect of chemotherapy in ovarian cancer82 and in BrCa83, whereas CHKA overexpression increases drug resistance in BrCa cells84. Targeting the genes or enzymes responsible for the Cho phospholipid metabolism may provide new molecular targets for treatment of TNBC67.

In another investigation of hormone receptors and protein expression, a larger study of 106 biopsies from 73 patients showed clear separation between TNBC and triple positive BrCas (TPBC) (ER-positive, PR-positive and HER2-positive cancers) (77.7% accuracy, p=0.001) using varying levels of metabolites: TNBC is characterized with higher levels of Cho and GPC and a lower level of Cr compared to TPBC. Partial least square-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) models enabled clear separations between ER-negative and ER-positive (72.2% accuracy, p<0.001), and PR-negative and PR-positive (67.8% accuracy, p<0.001) tumors in the testing set (Figure 5). ER-negative tumors show higher levels of Gly, Cho, and Lac compared to ER-positive tumors, suggesting enhanced glycolytic activity. PLS-DA classification and relative quantification of PR-negative and PR-positive tumors show similar metabolite profiles to ER-negative and ER-positive tumors. Validation of a PLS-DA model to separate HER2-negative and HER2-positive tumors discriminated the two with 69.1% accuracy (p<0.001). By relative quantification, HER2-negative tumors have a lower level of Gly, Gln, succinate, and Cr and higher levels of Ala, compared to HER2-positive tumors. Regardless of ER and PR status, higher levels of Gly were associated with HER2 overexpression67.

Figure 5.

PLS-DA score and loading plots of (A) TNBC vs. TPBC, (B) ERneg vs. ER pos, and (C) HER-2 neg vs. HER-2 pos breast cancer tumors. In the score plots (left), each symbol represents one sample. The score plots show the first and second latent variables (LV), and are used for interpreting relations between samples, thus similar samples are located close to each other. In the loading plots (right), the symbols represent metabolites that are significantly important for the discrimination between the groups. Variable importance in the projection (VIP) scores is illustrated by the heat map. The majority of TNBC, ERneg and HER-2neg samples have positive score for LV167.

Prediction of the response to the clinical treatment and prognosis with metabolic information

As BrCa is a heterogeneous disease, major efforts aim to more precisely identify women at risk for recurrence and to predict patient responsiveness to systemic therapies. Thirty-seven tissue samples from 37 locally advanced BrCa (a subset of BrCa characterized by the most advanced breast tumors in the absence of distant metastasis, T3–4 N1–3M0) patients were obtained by core needle biopsy65. These patients were treated with anthracycline- and/or taxane-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), and subsequently underwent surgery. The 37 samples were analyzed for a number of metabolite concentrations and choline-related compound ratios. Applying multivariate analysis, orthogonal projections to latent structure-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) model showed clear discrimination of three pathologic responses to NAC (sensitivity between 84.6–100%): pathologic complete response, partial response, and stable disease. Low concentrations of Tau, Cho, and GPC in the complete response group distinguished it from the others (p<0.05).

Another study confirmed that the partial response and stable disease groups could not be differentiated63,64. Seventy pre-treatment and eighty post-treatment spectra from 85 patients, who were treated weekly with doxorubicin NAC for 16 weeks before surgery, were acquired. Although there was a significant change in tumor metabolism in response to NAC treatment for patients with partial response and stable disease, there was no difference in the metabolic response between them by PLS-DA63. On the other hand, when comparing the metabolic changes between survivors (≥5 years) and non-survivors (<5 years), significant differences in the metabolic response to NAC were seen, including increases in Lac (p=0.004), and decreases Glc (p=0.002), in response to treatment in non-survivors compared to survivors. Under normoxic conditions, cancer cells, according to the Warburg effect, can reprogram their energy metabolism to largely depend on anaerobic glycolysis as their primary energy pathway, resulting in increased Lac production85,86. Increased Lac levels may be a marker for tumor aggressiveness as high levels of Lac have been correlated with low survival rates, high incidence of distant metastasis and recurrence, and increased risk of radiation resistance in several types of cancer 87–89. It has been hypothesized that Lac may enhance the invasiveness of tumor cells and the resulting low pH may help tumor cells evade tumor-attacking immune cells90.

From a larger open-label multicenter study where patients were randomly allocated to receive NAC treatment with either anthracycline (epirubicin) or taxane (paclitaxel) monotherapy, samples were analyzed from a subcohort of breast cancer patients (n=89)64. In this study, Gly appears to be decreased in survivors (≥5 years), and the difference in Gly relative intensities before and after treatment was significant (p=0.047)64. The observed Gly decrease in survivors may reflect altered glycolysis and/or reduced Cho levels associated with reduced tumor aggressiveness64.

HRMAS MRS was applied to intact tissue samples from BrCa patients with clinically defined good (n=13) and poor (n=16) prognoses57. Good prognosis was defined as no detectable cancer spreading to axillary lymph nodes, tumor smaller than 2 cm, and positive for ER and PR hormone receptors, with poor prognosis as the opposite. Absolute quantitative measurements of nine metabolites were analyzed by peak area ratios and PCA. A trend toward lower concentrations of Gly in patients with a good prognosis (1.1 mmol/g) compared to patients with a poor prognosis (1.9mmol/g) (p=0.067) was found. Tissue concentration of Glc was found to negatively correlate to proliferation index (MIB-1) (r2=−0.46, p=0.013). Most importantly, high levels of Tau, GPC, and Cr combined with low levels of Gly and PCho in BrCa tissue characterized patients who remained healthy five years after surgery. Combined peak area ratios or PCA of metabolic profiles from several metabolites more strongly correlated with patients’ prognosis and long-term health status than single metabolite concentrations.

In another study, 209 tissue spectra from 156 patients were analyzed by PLS-DA, probabilistic neural networks, and Bayesian belief networks to compare the prediction capability of different multivariate analysis methods58. A blind set (n=50) was used to test the training set (n=~150) for verification of each multivariate model. ER and PR status were successfully predicted by each method, but they were best predicted by PLS-DA with a correct classification of 44 of 50 and 39 of 50 samples, respectively. Lymph node status was best predicted by Bayesian belief network with 34 of 50 samples correctly classified, indicating a relationship between metabolic profile and lymph node status. It showed that hormone receptor-negative patients appear to have more Gly, GPC, and Cho than receptor-positive patients (p<0.05).

Relationships of metabolite, gene and protein information

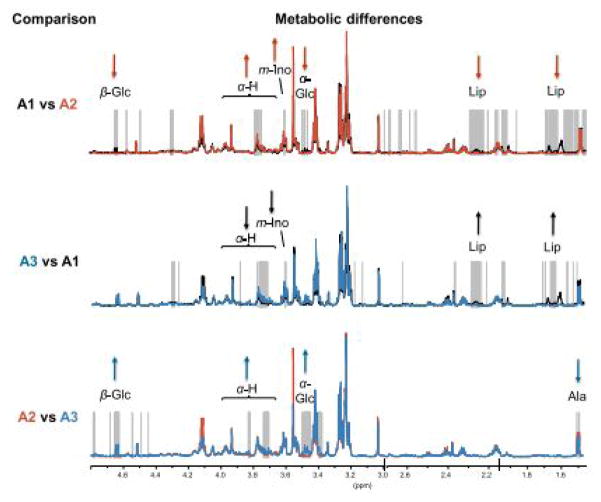

To investigate the potential of evaluating molecular mechanisms at different levels, a feasibility study measuring genetic and metabolic data from the same BrCa samples was conducted for BrCa tissue samples from 46 patients. Following HRMAS MRS, microarray analysis showed no significant change in total RNA integrity (p=0.86)56. Luminal A tumors, a subtype of BrCa that is HER2-, ER-, and PR-negative, were split into three subgroups based on hierarchical clustering of the HRMAS MR spectra. One of the subgroups, designated A2, showed significantly lower Glc and higher Ala levels than the other two groups (p<0.001), suggesting higher glycolytic activity in the A2 tumors (Figure 6). Potentially explained by increased glycolytic activity and indicative of a more aggressive tumor, Gene Ontology (GO) terms related to cell cycle and DNA repair also significantly differentiated this group from A1 tumors.

Figure 6.

Differences in metabolic and gene expression profiles of identified groups of luminal A samples. Mean spectra of the A1 (black), A2 (red) and A3 (blue) groups of luminal A tumors are plotted with the significantly different points (p<0.001) indicated with grey vertical lines. At ppm values with allocated metabolites and significant differences in one group vs. the other, the direction of the arrows indicate if the latter group has the highest (up) or lowest (down) mean value56.

Analysis of protein expression was also combined with metabolite and gene evaluations in a study of 228 BrCa patients70. HRMAS MRS was performed to gather tumor metabolic profiles, and hierarchical cluster analysis resulted in three significantly different metabolic clusters (Mc1, Mc2, and Mc3) that could provide treatment guidance in the clinic. Genomic and proteomic assays were also conducted to investigate correlations with the metabolomic-derived clusters: reverse phase protein array subtypes and genetic subtypes significantly differed among the three clusters, with assays finding that extracellular matrix- and collaged-associated genes were downregulated in Mc1, for example. Metabolomic evidence of an increased glycolytic rate in Mc1 also helps to classify it as the cluster likely with the worst prognosis. These approaches of combining information from several –omics levels show promise in sub-classifying BrCa or improving the understanding of breast cancer heterogeneity, potentially leading to more patient- and therapy-specific treatment70.

Selective tissue metabolic relationships observed with intact BrCa tissues are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selected papers on breast cancer with metabolic findings highlighted, 1998–2016. Additional abbreviations: Asc, ascorbate; Asn, asparagine; Eta, ethanolamine; Fum, α-Haa, hydrogen attached to α-carbon of amino acid, Phe, phenylalanine; pro, proline; Tyr, tyrosine.

| Year | Author | Samples investigated | Metabolites increased (in first named tumor vs. second) | Metabolites decreased (in first named tumor vs. second) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Cheng54 | IDC II vs. II–III | Lac/Cho, PC | |

| IDC II vs. III | Lac/Cho, PC | |||

| 2006 | Sitter55 | Tumor vs. non-involved | PC/Cho | GPC/PC, GPC/Cho |

| IDC III vs non-cancer (tumor without cancer cells) | Cho | |||

| Chemo-treated vs. non-cancer | Cr | |||

| Tumor >2.0 cm vs tumor ≤2.0 cm | Gly,Cho | |||

| Cancer cell vs. fat and fibrous connective tissue | Gly, PC | |||

| 2010 | Borgan56 | A1 vs. A2 | β-Glc, α-Glc, Lip | Ala, α-Haa, myo-Ino |

| A2 vs. A3 | Ala | β-Glc, α-Haa, α-Glc | ||

| A3 vs. A1 | α-Haa, myo-Ino | Lip | ||

| Sitter57 | Good prognosis vs. poor prognosis | Tau/Gly, GPC/Gly, tCho/Gly | ||

| Giskeødegård58 | ER-negative vs. ER-positive | Gly, GPC, Cho, Ala, Asc, Cr, Tau, PC, Lac | ||

| PR-negative vs. PR-positive | Asc, Lac, Gly, GPC, PC, Cho, Cr, Ala | |||

| 2011 | Li59 | Cancer vs. non-cancer | Tau, ChoCC (PC especially) | Asp |

| Klomp60 | 31P MRS 7T in vivo patient 1 vs. healthy | PE, PC, GPC | ||

| 1H MRS 7T in vivo patient 1 vs. healthy | tCho | |||

| 2012 | Choi61 | ER-negative vs. ER-positive | Cho | |

| PR-negative vs. PR-positive | Cho, Cr, Tau | |||

| HER2-negative vs. HER2-negative | Tau, scy-Ino, myo-Ino | |||

| Low histological grade vs. high histological grade | PC/Cr | |||

| TNBC vs. TPBC | Cho, Cho/Cr, tCho/Cr | |||

| Low Ki-67 vs. high Ki-67 | PC, tCho, PC/Cr | |||

| Good prognosis vs. poor prognosis | scy-Ino, Gly | |||

| Giskeødegård62 | ER-positive survivors vs. non-survivors | Lac | ||

| Cao63 | Pre-NAC survivors vs. post-NAC survivors | Gly, GPC, PC, Cho, tCho | β-glc, Lac, Gly | |

| Cao64 | Pre-NAC PR vs. post-NAC PR | GPC, tCho | ||

| Pre-NAC survivors vs. post-NAC survivors | GPC, Cho | |||

| Survival ≥5ys vs. Survival <5ys | tCho | Lac | ||

| 2013 | Choi65 | pCR vs. PR | PC/Cr | |

| Bathen66 | Tumor vs. non-tumor | Asc, Lac, Cr, Gly, Tau, ChoCC | Glc | |

| 2014 | Cao67 | TNBC vs. TPBC | Cho, GPC, Glu | Cr, Gln |

| ER-negative vs. ER-positive | Gly, Cho, Lac, Glu | Gln | ||

| HER2-negative vs. HER2-positive | Gly, Gln, succinate, Cr | |||

| 2016 | Chae68 | DCIS vs. DCIS with invasive cancer | GPC/PC, myo-Ino, succinate | |

| Yoon69 | High SER vs. low SER | Asn, Cho, Fum, Glu, His, PE, Phe, Tyr, uracil, tCho | ||

| High SUV vs. low SUV | Asn, Fum, Glu, Lac, PC, PE, uracil, tCho | |||

| ER-positive, high SER vs. low SER | Asn, ethanol, Eta, Fum, Gln, His, Lys, Phe, Tyr, uracil | |||

| ER-positive, high SUV vs. low SUV | Fum, Lac, uracil | |||

| PR-negative, high SER vs. low SER | Asn, His, Phe, Tyr, Uracil | |||

| PR-negative, high ADC vs. low ADC | Asp | |||

| PR-negative, high SUV vs. low SUV | Asn, PE, Uracil | |||

| PR-positive high SER vs. low SER | Fum, Lys | |||

| PR-positive high ADC vs. low ADC | His, Phe, Tyr | |||

| PR-positive high SUV vs. low SUV | Lac | |||

| HER2-negative, high SER vs. low SER | Asn, Cho, Eta, Fum, His, PE, Uracil | |||

| HER2-negative, high ADC vs. low ADC | Thr | |||

| HER2- negative, high SUV vs. low SUV | Asn, Cho, Fum, Glu, Lac, PE, Uracil | Ile | ||

| HER2-positive, high ADC vs. low ADC | Eta, Uracil | Lac | ||

| HER2-positive, high SUV vs. low SUV | Betaine, Cr | |||

| Ki67-negative, high SER vs. low SER | Fum, His, Lys, Pro, Uracil | Ala | ||

| Ki67-negative, high ADC vs. low ADC | Leu | Tau | ||

| Ki67-negative, high SUV vs. low SUV | Asn, Fum, Lac, Uracil | |||

| Ki67-positive, high SER vs. low SER | Phe | |||

| Haukaas70 | Mc1(58p) | GPC, PC | Lac, Tau, Ala, Glu, Ace | |

| Mc2(58p) | β-glc, myo-Ino | Lac, Cr, Gly, Tau, GPC, PC, Ala, Asc, L-Tyr | ||

| Mc3(112p) | Lac, Gly, Tau, Cr, Ala | β-Glc, GPC, PC | ||

| Mc1 vs. Mc2 | GPC, PC, L-Tyr, Asc, Cr, Ala | β-glc, myo-Ino, scy-Ino, Glu, Ace | ||

| Mc1 vs. Mc3 | GPC, PC | Lac, Tau, Ala, Glu, Ace, myo-Ino | ||

| Mc2 vs. Mc3 | β-glc, myo-Ino, Ace | Asc, Lac, L-Tyr, Gly, GPC, PC, Cr, GSH, succinate, Ala | ||

| Park71 | Center vs. periphery | Pro | ||

| Haukaas72 | 1.5h after vs. before | Glc, Gly, Cho | GPC |

Prostate Cancer

This chapter critically reviews publications on prostate cancer (PCa)91–116 and concentrates on metabolic changes that allow for discrimination between benign and malignant tissues as potential biomarkers, as well as their connection to clinical parameters, including the Gleason scores (GS), pathological stage, and disease prognosis. Given the limitations of biopsies, digital rectal exams, and prostate-specific (PSA) tests, novel tools are necessary to guide disease surveillance, avoid overtreatment, and improve patient’s quality of life.

Metabolic differentiations of malignant and benign prostate tissues

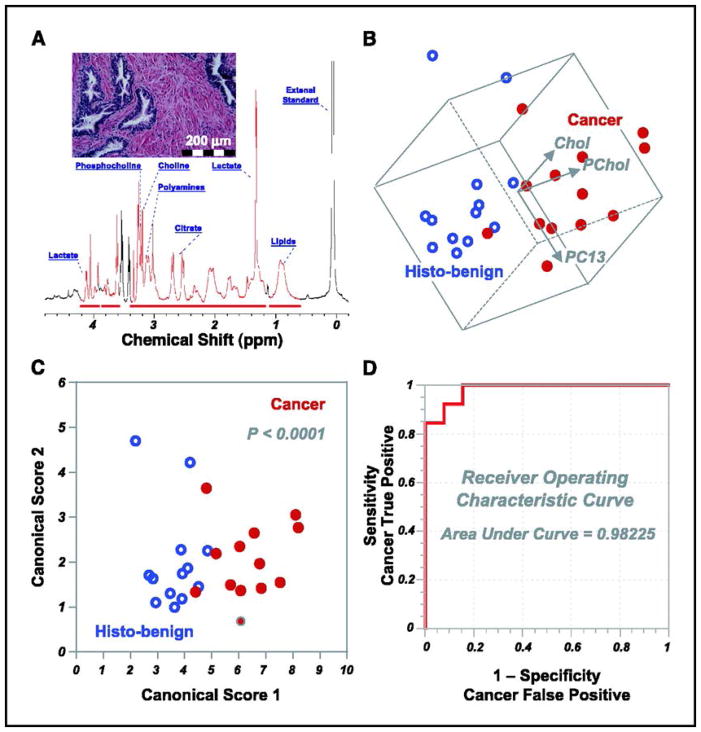

HRMAS MRS studies on PCa started with attempts to differentiate samples according to their malignant or benign status, with the first measuring 199 specimens (5 GS=5, 126 GS=6, 53 GS=7, 9 GS=8, and 6 GS=9) from 82 prostatectomies. Metabolites PCho and Cho were seen to strongly contribute to the PC that significantly differentiated tissue status (p<0.005) (Figure 7b)93.

Figure 7.

(A) High-resolution magic angle spinning 1H MR spectrum of intact tissue obtained from the removed prostate of a 61-year-old patient with GS 6 T2b tumors. (B) Three-dimensional plot of principal component 13 (PC13 correlates linearly with percent volume of cancer cells in tissue samples) vs. phosphocholine vs. choline. Cancerous and histologically benign (histo-benign) tissue samples from 13 patients can be visually separated in observation plane. The paired Student’s t test results (cancer vs. histo-benign from the same patients) for principal component 13, phosphocholine, and choline are 0.012, 0.004, and 0.001. Only results from these 13 patients could be evaluated with paired tests for other cancer positive samples were collected from patients from whom no histo-benign samples were analyzed. (C) The canonical plot resulting from discriminant analysis of the three variables in B presents the maximum separation between the two groups. (D) The resulting receiver operating characteristic curves indicates the accuracy of using the three variables in B to positively identify cancer samples93.

Since publication of this study in 2005, ChoCC have been evaluated as discriminant metabolites for PCa in several others92,94,101,110–115. PCa tissues have also been compared with other non-cancer prostate pathologies such as healthy glandular (n=20) and stromal tissues (n=20), with the former being the epithelia that are responsible for secretion and the latter, smooth muscle cells111. When predominantly stromal tissue is compared to cancer, enrichment of ChoCC in the latter significant differentiates the two (p=0.01)112. In addition, myo- and scy-Ino elevations may derive from membrane-associated phosphatidyl inositols or from inositol phosphates which serve as cellular signal transduction messengers103. Notably, using multivariate linear regression, the myo-Ino/scy-Ino ratio was reported to correlate inversely with tumor load from studies of 108 non-malignant and 41 malignant samples (p=0.001)110. Furthermore, this ratio also seemed to correlate with distance to tumor foci (p=0.03). Therefore, the ratio between these isomers may be important for PCa evaluation. In addition, this distance relationship could also be seen with the (ChoCC + PC)/Cr ratio (p<0.001).

Lac and Ala levels are also enhanced in PCa tissues101,113–115. Results from a study of 20 PCa samples revealed that higher concentrations of ChoCC and Lac were seen in PCa tissues than were measured in healthy glandular and stromal tissues (both p<0.01), and Cho and Ala were also significantly higher in PCa tissues when compared with stroma (both p<0.01)113. Although Lac and Ala enhancements may be caused by hypoxia which occurred during sample handling, their large ratio (Lac/Ala) seemed to be indicative of PCa, as Lac may be increased through anaerobic glycolysis115. These results indicated stimulation of glycolytic flux, cytosolic amino acid transformations, and protein synthesis104. The altered Lac levels may result from a number of biological processes, including the Warburg effect85,86,116, the activation of hyaluronan synthesis105, the upregulation of the growth factor VEGF97, or the hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1α106. When comparing benign samples predominantly containing glandular or stromal tissues, Lac and Ala levels did not differ significantly114. Together with Cho derivatives, ethanolamine (Eta)-containing compounds were reported as discriminant (15 cancer vs. 32 benign)111. High levels of PC, GPC, PE, and GPE and low Eta were found in cancer specimens. Moreover, evaluations of metabolic ratios presented higher values for PC/GPC (sensitivity=73%, specificity=81%), PC/PE (sensitivity=73%, specificity=81%), PE/Eta (sensitivity=50%, specificity=77%), and GPE/Eta (sensitivity=64%, specificity=81%) ratios in cancer cases 111. Since these molecules are precursors or degradation products of phospholipid membranes74, they indicate cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and enzymatic activity in cancer status117–122.

Another interesting class of biomolecules found in malignant specimens is the omega-6 polyunsaturated FA (n-6-PUFAs), including linoleic acid, γ-linolenic acid, dihomo-GLA, and arachidonic acid109. Results from this study suggested that n-6 PUFAs did not accumulate in the adjacent non-malignant tissue. These data were in accordance with reports of potent stimulant effects of n-6 PUFAs for PCa development and aggressiveness99, likely due to their involvement in diet, cell death, mitochondrial and cell membrane breakdown, and accelerated cell turnover in lipid-rich regions.

Concentrations of Cr do not significantly differ for different PCa pathological status113. For this reason, several studies have used Cr as a normalization factor and reported significant increases in (ChoCC+Cr)/Cit, ChoCC/Cr (both p<0.05)115, Tau/Cr (p=0.03), and polyamine-to-Cr (PA/Cr) ratios (p=0.013) in cancer samples. Many also report a decrease in the Cit/Cr ratio (p=0.05)112 or positive correlation of (ChoCC + PC)/Cr, Cho/Cr, and scy-Ino/Cr with tumor load (0%–100%) (p<0.05)110. In the latter study of 149 tissue samples, 108 samples with 0% tumor load were characterized by a broad variability in stroma-to-epithelium ratio, as well as by the presence of inflammatory cells and diverse glandular morphologies. Interestingly, inter-sample difference of (GPC + PC)/Cr ratios did not vary as much for these samples with variable pathology as compared with samples of >0% tumor loads. The (GPC + PC)/Cr ratio also correlated with number of proliferating cells, measured by proliferation marker Ki67 presence (p<0.001)110.

Potential biomarkers in PCa

Since serum PSA levels are known to be prostate specific, but not cancer specific nor capable of predicting PCa aggressiveness, additional biomarkers may contribute to a more personalized PCa clinic91.

Results from a number of studies indicated citrate (Cit) and polyamines as potential prostate biomarkers92,94,112,114,115. Bivariate linear least square analysis performed on 16 adenocarcinoma samples (9 GS=6, 6 GS=7, and 1 healthy control) showed increased levels of Cit (p=0.001) and spermine (Spm p=0.018), a polyamine, with increases in percentage volume (vol%) of normal prostatic epithelial cells in the analyzed samples94, indicating that Cit and Spm are largely presented in histologically-benign (histo-benign) prostate epithelial glands96. In addition, Cit and Spm were also linearly correlated (r2 = 0.75, p=0.0001). The reduction of Cit is likely due to the depletion of zinc in PCa cells, since zinc can function to prevent oxidation of Cit in the Krebs’ cycle98. Spm is also an important metabolite in the prostate for its inhibitory effect on the growth of PCa cells in vitro108. Interestingly, since Cit and Spm are secreted in histologically benign (histo-benign) lumen epithelia95,100, linear correlations were observed between concentrations of both metabolites and computer-aided image analysis-determined vol% of epithelium with lumen and without lumen. Correlations between vol% epithelium with lumen were reported for Cit (r2=0.432; p<0.02) and Spm (r2= 0.490; p<0.02), and correlations between vol% epithelium without lumen and the metabolites were r2= 0.581; p<0.01 and r2= 0.336; p<0.05, respectively. However, no correlation was found between metabolic concentrations and vol% lumen alone, suggesting the metabolites are secreted as a function of normal epithelia92.

Correlation of metabolomics with clinical features

Metabolites measured with HRMAS MRS also have been correlated with Gleason scores, PSA levels, or risk of biochemical recurrence (BCR).

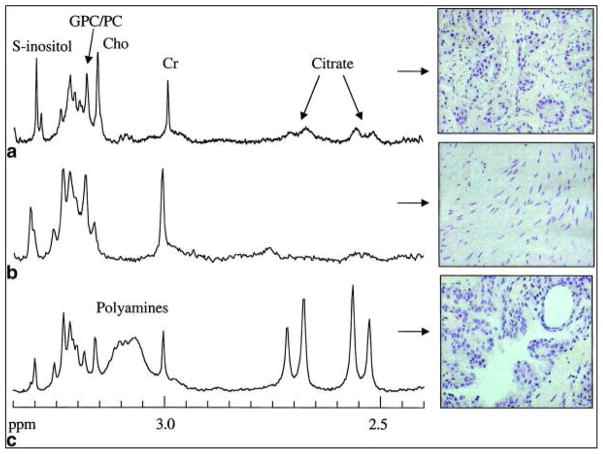

The Gleason Score (GS) is the most relevant parameter for PCa evaluation in clinic. HRMAS MRS results indicated increases in Cho, (Cho + Cr + Spm)/Cit ratio, and n-6 PUFAs, and decreases in Cit in association with high grade PCa107,109,112. Linear regression analyses have shown that Cho/Cr, tCho/Cr, and Cit/Cr ratios significantly relate to GS (all p<0.05), and, according to Spearman’s rank tests, significant correlation coefficients link GS with GPC+PC/Cr, Cho/Cr, tCho/Cr, Cit/Cr, tCho/Cit, and (tCho+Cr)/Cit (all p<0.05) (Figure 8)115. Because of Cit secretion in histo-benign glandular epithelia, higher Cit/Cr ratios were measured in histo-benign glandular than in stromal tissues (p=0.0011), or in samples with <20% (p=0.017) or >20% (p=0.05) presence of PCa glands112. Thus, Cit/Cr alone may not separate predominantly stromal specimens from those containing cancer or between GS 6 and GS 7 cancers. As expected, similar results were observed using Spm/Cr ratio112.

Figure 8.

Ex vivo 1H HRMAS spectra showing the Cho-to-Cit region and corresponding H&E staining patterns of excised tissue samples containing (a) predominantly prostate cancer, (b) benign predominantly stromal tissue, and (c) benign predominantly glandular tissue112.

However, unlike relative concentrations, examining absolute concentrations of Cit and Spm showed significant differences in the presence of PCa, with Spm being almost absent in GS 7112. Furthermore, Spm and Cit also seemed capable of separating tumors confined in both lobes from tumors invading extraprostatic tissue and from cancer confined in a single lobe, as well as recognizing benign GS 6 from benign GS 7 samples93. The ChoCC/Cr ratios were reported to be significant only for samples with cancer load ≥ 20% (p≤0.05)112.

A decrease in Cit concentrations in benign epithelia was correlated to faster PCa growth rates (p<0.05, n=27 from 18 patients), as low Cit/epithelia levels were symptomatic of rapid increase in PSA values (r2=0.27, p<0.034), hence higher PSA velocities. Similar results were reported when correlating Cit/epithelia with PSA densities (r2=0.31, p<0.021) and blood percent-free PSA (r2=0.53, p<0.011)98.

HRMAS MRS has also been employed in estimation of the risk of BCR after prostatectomy. Sixteen patients with BCR were paired with 32 subjects with no BCR and matched according to age, GS, and observation period. Based on four PCs, metabolomic profiles can differentiate matched groups with and without BCR. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) provided insight that recurrence could be predicted in 71% and 78% of cases, according to the four identified PCs and all nine PCs, respectively102.

Another interesting application of HRMAS MRS was the characterization of androgen deprivation therapy effects on patients treated with Degarelix, a drug that rapidly suppresses PSA expression and castrates testosterone levels101. OPLS-DA of 7 untreated and 6 treated prostate samples proposed, without a validation set, that depletions in Lac and ChoCC concentrations were indicative of Degarelix treatment. As described in the previous sections, the former observation could be related to lower glycolysis, while the latter may implicate drug-induced effects on the phospholipid metabolism. These ex vivo findings support the possibility to monitor the pharmacological response of the patients by optimized in vivo 1H MRS techniques.

Cervical Cancer and Uterine Leiomyomas

Research on the uterine organ has focused on two clinical conditions with very different underlying biochemical mechanisms.

Cervical cancer (CeCa) accounts for 10% of all female cancers in western countries123. This low rate is probably the result of the implementation of screening programs over the last 50 years; in fact, in countries where such strategies are not systematically applied, CeCa is the predominant form of cancer among women124. The majority of the literature on the discrimination between CeCa and non-malignant specimens agrees on higher levels of Cho-containing compounds (GPC and PC) (p≤0.05) as cancer indicators125–129. While the Cho derivatives are common features in different type of cancers due to stimulated cell turnover, the correlation between oncogenic human papillomavirus and CeCa130 also presents viral proteins E6 and E7131 as partially responsible for alterations in ChoCC.

Lipids, especially triglycerides, comprise another class of discriminants that increase with the presence of CeCa malignancy (p<0.05)125,127,128,132. Current hypotheses suggest the presence of apoptotic cells133 and necrosis as reasons for increases; however, the role of necrosis is under debate because of their involvement in a variety of different cancers134–136. Results from a linear regression show that lipid peak areas fail to correlate with tumor load for samples with greater than 20% tumor, suggesting that a sizeable tumor presence may induce changes in the adjacent tissue through ‘field effects’ that cause its lipid profile to look more like cancer (p<0.05)132. However, no data were available to indicate the distance over which this metabolic change is detectable.

Increases of amino acid residues such as Cr (p=0.05), Tau, and Ala (p<0.001) have been observed as characteristic of tumor tissue125,128,129. Intriguingly, Ala and Cr levels appear depleted in benign tissue from cancer patients when compared with normal tissue from non-cancer patients, suggesting metabolite depletion in benign tissue adjacent to cancer129. Therefore, the presence of tumors alters the metabolic profile of the surrounding cells137. Moreover, the significant presence of Tau may be an endogenous defense mechanism against tumor proliferation125. In addition, a study of six squamous cell carcinomas, two adenocarcinomas, and eight nonmalignant hysterectomy tissues measured higher Lac and lower levels of Glc in malignant samples125, suggestive of the Warburg effect, the preference for anaerobic lactic acid fermentation over the usual energetic pathways85,86,138,139.

Results from analysis of 44 biopsies sampled before and during radiotherapy in 23 patients identified a relationship between samples with high tumor cell fraction and high tumor cell density, finding elevated levels of Lac, Cr, GPC, and PC and decreases in Glc, myo-Ino, Tau, and Cho (p<0.001) associated with each140. The increases in GPC and PC and the reduced levels of Cho suggest high membrane turnover, cell proliferation, and activation of choline kinase-initiated Cho-to-PC conversion and the phosphatidylcholine pathway74,141,142. Furthermore, the study also showed that apoptotic cell density correlated with lipid contents (r=0.95, p<0.001). Low apoptotic activity has been associated with aggressiveness and treatment resistance in many tumor types, including CeCa143,144. Here, the positive correlation between lipid contents and highly apoptotic tissues is probably due to modifications in the composition of cytoplasmic lipid droplets145. The lipid increase in cancer specimens could be enhanced when apoptosis is triggered by radiotherapy and could be an indicator of treatment success. Lac and lipids were also reported as discriminatory metabolites between adenocarcinomas and samples from patients with lymphatic invasion125.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is a pre-invasive stage of CeCa that can function as an investigative model to explore early events in the biology of epithelial malignancies129. Metabolomic comparisons of punch biopsy samples of 27 squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 12 CIN, and 39 normal tissues showed SCC as characterized by longer, more saturated lipid side-chains than CIN and healthy cases, only reaching statistical significance for distinguishing SCC and healthy126. Increased levels of Cho and Cr also characterized SCC tissue, but no significant separation was possible between CIN and normal tissues.

ChoCC (p=0.034) and lipids at 1.3 ppm (p<0.005) were helpful in separating CIN (n=14) from CeCa (n=23)146. ANOVA with Bonferroni correction and t-test analyses showed that higher levels of both metabolic classes characterized tumor cases. These observations may be explained by rapid cell membrane turnover, resulting in accumulation of choline metabolites not only in the cancer cells, but also in the peritumoural tissue. Unfortunately, analysis of the stromal portion delivered no significant information. In another study investigating CIN, ChoCC measured with 73 biopsies (5 histologically normal cervix, 5 mild CIN, 40 moderate/severe CIN, and 23 invasive cancer) showed higher (p≤0.002) concentrations could distinguish cancer from high-grade CIN tissues, and could separate CIN samples of cancer-affected from CIN of non-cancer patients (p=0.0001)129. Nevertheless, in light of the previously discussed effects on these metabolites from tissue pathological features, such as the proportion of epithelia, interpretations of the experimental results should also consider the presence of tissue pathology.

Another medical condition affecting 20 to 50% of women is uterine leiomyomas, commonly known as fibroids, which are solid, benign, and non-degenerating pelvic tumors. Intense pelvic pain, urinary disturbances, uterine bleeding, anemia, infertility, and abortion may be related outcomes147. To search for a comprehensive molecular description of the condition, intact healthy (myometrium) and leiomyoma uterine tissues from 10 subjects were studied148. The application of ANOVA and PC analyses revealed an enrichment of Glu and Gln and a depletion of Tau in leiomyomas (p≤0.05). In addition to these main differences between the two groups, increases in myo-Ino, Lac, leucine and isoleucine also played roles in separation of the two groups (p≤0.05).

Gastrointestinal Neoplasia

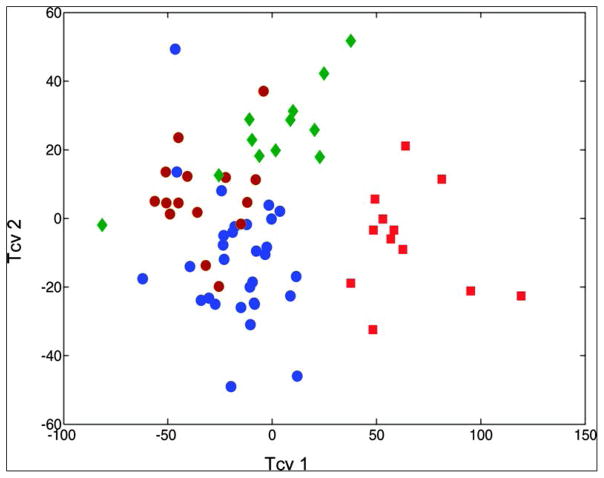

HRMAS MRS has been used as a diagnostic tool to differentiate between gastrointestinal mucosae types. In analyzing tissue biopsies from eight female and eight male healthy subjects, no measurable difference was found in the overall metabolite composition between genders. However, metabolite intensities did show dependency on the anatomical sites from where biopsies were obtained149. These investigated topographical regions including antrum, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon. By using a cross-validated OPLS-DA model, it was observed that the antrum, the duodenum and jejunum together, and the colon all had specific metabolic profiles, whereas the ileum overlapped with the duodenum/jejunum and the colon (Figure 9). This observation is anatomically reasonable for the ileum links the jejunum and colon. In addition, the study correlated metabolic alterations with physiological conditions in the gut. Since the stomach is exposed to low pH values and osmotic stress, the appearance of protective glycoproteins and osmolytes, such as Tau, is physiologically logical. Traces of pancreatic lipid digestion – such as lipids and Cho – are seen in duodenal spectra, and the glutathione observed may function to protect cells against radicals resulting from lipid digestion. Amino acids seen in ileal spectra might reflect energy metabolism in the gut which depends heavily on amino acids, such as Gln. The diverse microbiome of the colon results in a great deal of bacterial fermentation, which could explain the large amounts of acetate in the spectra of colonic mucosa.

Figure 9.

OPLS-DA cross-validated scores plot showing differentiation of the metabolic profiles of localized gastrointestinal compartments. Red squares, antrum; blue dots, combined duodenum and jejunum, brown dots, ileum; green rhombus, colon149.

Cancers of the gastrointestinal tract account for almost 17% of all cancer cases in developed countries and about 20% in developing countries150. To understand metabolic differences among cancer types and stages within a type, HRMAS MRS studies have investigated colorectal cancer (CRCa). The findings from different reports regarding metabolic changes in CRCa were similar and consistent. In agreement with the Warburg effect, higher levels of Lac and lower levels of Glc were found in CRCa tissue samples, as well as lower levels of lipids (all p<0.05)151–153. Increased levels of cell membrane components Cho and ChoCC, a marker of cell proliferation, were found in cancer cells (all p<0.05)151,153. Higher levels of the amino acid Gly were found in cancer as well; in one report it reached a very high level of significance with p<0.005152 and is again linked to cell proliferation as a precursor in the synthesis of glycolysis intermediates151,152.

While many studies focus on individual metabolites, a pilot study on rectal cancer compared 14 malignant and 9 benign samples collected from 5 patients using PCA. Analysis revealed statistically significant differences in malignant-benign comparisons for a variety of spectral regions not identified with specific metabolites (all p<0.03), as well as highlighted correlations between histopathological features and spectral regions154.

In addition to reporting metabolic changes between benign and cancer samples, HRMAS MRS has also been used to assess CRCa tumor (T), lymph node infiltration (N) and metastasis (M) status – the TNM-staging essential for therapy decisions and prognosis. A study analyzed 44 samples from tumor centers and 44 samples from mucosa 5 cm from the tumor margin. The results suggested different tumor stages have distinct metabolic profiles. The development from T1/2 to T3 is marked by an increase in lipids and acetate and a decrease in GPC, whereas, T4 tissue seems to be metabolically depleted when compared to T3 tumor tissues. This seemingly-unexpected decrease in metabolite activities in T4 tumors likely indicates the T3 stage experiences the most powerful growth. The study was able to correctly classify 90%, 91%, and 75% of T1/2, T3 and T4 tumors, respectively152.

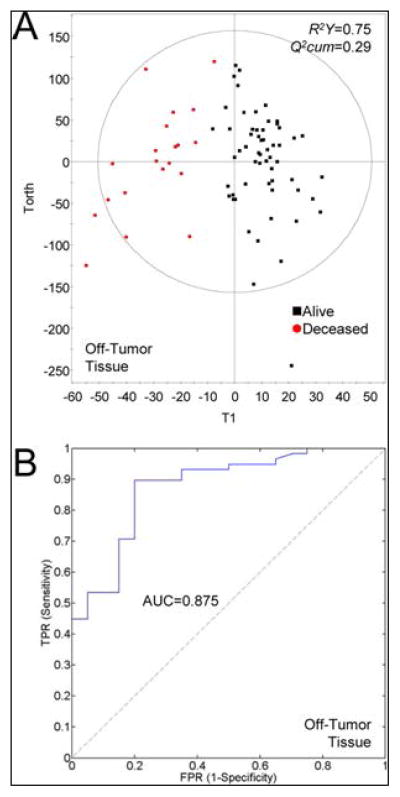

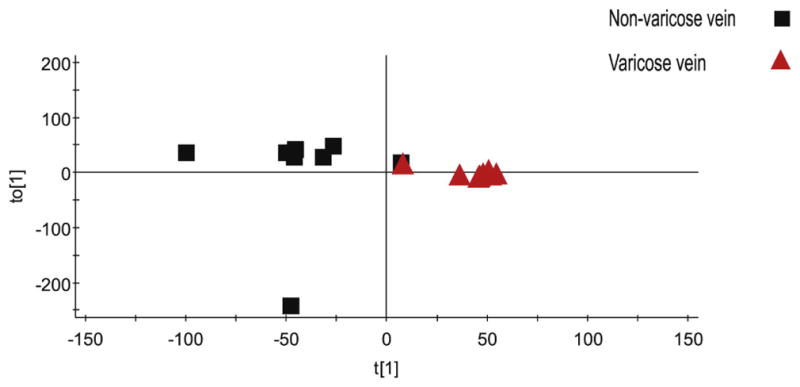

Tumor growth can metabolically change the tissue environment, as explored in a study using ‘off-tumor-tissue’ (OTT) to predict the N-stage from 83 tumor and 86 OTT samples from 26 patients. OTT samples localized next to T4-staged tumors showed lower levels of Glc and formate but increased levels of certain amino acids, such as Val (p<0.05), when compared to OTT samples next to T1 – T3 tumors, likely caused by higher protein degradation in the area surrounding higher-staged tumors. In addition, OTT presented metabolic profiles that varied by N-stage. Patients with lymph node infiltration had higher levels of Leu and phenylalanine (Phe) in their OTTs (p<0.05). Higher N-stages, in general, were associated with the trend of lower triglyceride levels likely due to a higher consumption of TGs during fast growth. Interestingly, for the prediction of the N-stages, the OTT metabolic profile presented a higher predictive power (AUC=0.92) than the metabolic profile measured from tumor tissues (AUC=0.88). Furthermore, a very promising predictive result was observed when correlating five-year patient survival rates with specific metabolic changes, which indicated that a relapse in CRCa was more probable for patients with higher concentrations of Cho, isobutyrate and acetate (Figure 10)153.

Figure 10.

Survival prediction power for CRC using HRMAS metabolite fingerprints of tumor and off-tumor samples. (A) Scatter plot of the OPLS models of tumor and off-tumor tissue samples for patients alive (■) and deceased at 5 years after surgery (red ●). (B) ROC curve for the previous model. Reprinted with permission from153. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

Being the products of bacterial fermentation, isobutyrate and acetate may indicate the possible role of the colonic microbiome in CRCa. Supporting this hypothesis, a product of bacterial cell wall degradation, isoglutamine, was found to be higher in CRCa cells than in OTT (p<0.05)153. Besides probable microbiota differences, metabolic differences between rectal and colonic cancer have been identified. Tissue samples obtained from colonic tumors were characterized by decreased levels of Lac (p<0.005) and increased levels of arginine and acetate (p<0.005) when compared to rectal cancer biopsies152.

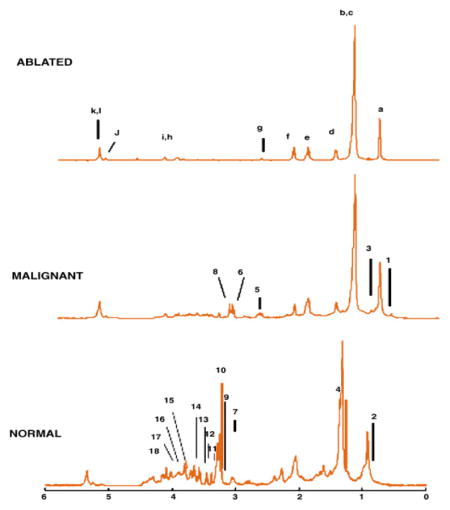

Gastric cancer

Both cancerous and non-cancerous gastric samples have been studied to identify metabolites characterizing gastric tissue. About 40 metabolites, with only slight and non-significant differences in relative abundance between the samples, were identified by a study examining healthy gastric mucosa155. Examination of five gastric cancer tissue samples (Helicobacter pylori-positive with different tumor grades and differentiations) and 11 healthy controls found higher levels of lipids and Gly and changes in metabolite ratios such as the Cho/ChoCC and the ChoCC/Cr ratio to be indicative of gastric cancer. While the Cho/ChoCC ratio showed an increase from 1:5 in healthy tissues to 4:1 in cancerous ones, the ChoCC/Cr ratio decreased from 16:1 to 2.5:1 in cancer samples. As stated previously, larger amounts of Gly may be linked to altered glycolysis156.

In addition to gastric cancer, autoimmune gastritis and Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis were examined in 27 subjects. Twelve healthy controls were compared to five samples in each of the three above-mentioned pathological conditions. Typical findings for gastric cancer were increased levels in free Cho, Gly, Ala, lipids, and triglycerides, with the latter only found in adenocarcinoma. Two ChoCC, phosphatidylcholine and glycerophosphocholine, decreased in cancerous samples. A similar ChoCC decrease was seen for autoimmune gastritis samples, highlighting their similarity to gastric neoplasia. Tissue with Heliobacter pylori-associated gastritis more resembled the healthy controls, with phosphorylcholine as the most abundant metabolite157.

Esophageal tissue

An HRMAS MRS study of 17 samples of Barrett’s metaplasia, a precursor of the esophageal adenocarcinoma, and 17 squamous epithelium tissue samples both obtained from 16 Barrett’s patients revealed metabolic alterations between the two tissue groups. In particular, a highly significant increase in the Cho/Cr ratio was seen in Barrett’s metaplasia (p<0.001)158. Results from analyzing tissue from 52 control subjects and 70 samples (32 tumor and 38 proximally histologically benign mucosa) from 35 esophageal cancer patients indicated metabolite changes in the various esophageal tissues. Applying PLS-DA on spectra of all samples, 5% of the profile showed a consistent change from healthy controls to benign mucosa to cancerous tissues from cancer patients. Metabolites that contributed to this relationship include phosphocholine and Glu and were suggested to be putative biomarkers. This study further created a model that could predict the three different types of tissue with high accuracy (p<0.01)159.

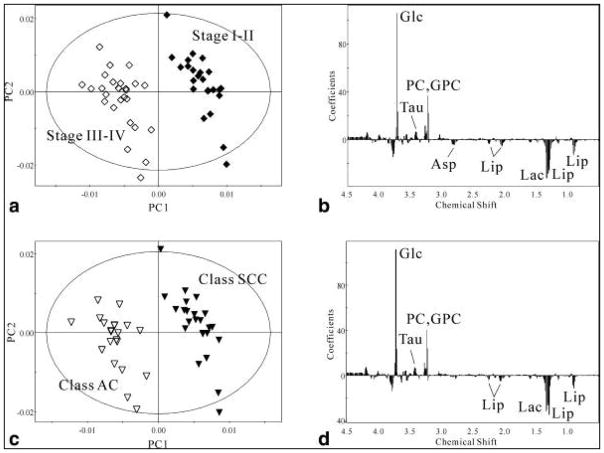

Lung cancer

Lung cancer (LuCa) is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States with 155,870 estimated deaths in 2017 alone5. Findings from HRMAS MRS studies on LuCa overlapped for many metabolites, with specific findings in Table 4. The main aim of these studies was to reveal metabolic differences between healthy and cancerous tissue and to use these results as a tool for disease discrimination. Results showed that Lac, ChoCC and Tau were consistently elevated in cancer, whereas Glc, acetate, myo-/scy-Ino and Gly were found to be decreased160–162. As previously discussed, the decrease in Glc and increase in Lac is likely linked to the Warburg effect, and the higher levels of ChoCC are markers for cell-proliferation. Differences in osmolytes such as myo-/scy-Ino might be linked to osmolytic shifts in tumor cells. Statistical analysis revealed significant changes in some metabolites when comparing tissue from centers of tumors with adjacent or parenchyma tissue from 17 patients [8 SCC, 7 adenocarcinoma (AC), 1 small cell lung carcinoma, and 1 malign mesothelioma]. Asp, Lac and PC/GPC showed increases from margin to tumor center (all p<0.05), whereas Glu and Val decreased progressively from margin to tumor center (all p<0.05). In addition, a positive correlation was seen between Lac and lipid levels (r=0.701, p<0.0001), but a negative correlation between Glc and Lac was observed (r=−0.439, p<0.005). Further, PCA and cross-validated OPLS-DA approaches were used to create a differentiation tool based on HRMAS MRS data. PCA could discriminate between the different sample origins – center, parenchyma, adjacent – and OPLS-DA differentiated stage I/II from III/IV and adenocarcinoma from squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 11)162.

Table 4.

Selected papers on lung cancer with metabolic findings highlighted. Samples in italics denote agreement between two or more studies.

| Study | Sample size | p - values | Metabolites elevated in lung cancer | Metabolites decreased in lung cancer |