Abstract

Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, most commonly types 6 (HPV-6) and 11 (HPV-11). Due to failed host immune responses, HPV is unable to be cleared from the host, resulting in recurrent growth of HPV-related lesions that can obstruct the lumen of the airway within the upper aerodigestive tract. In our murine model, the HPV-6b and HPV-11 E7 antigens are not innately immunogenic. In order to enhance the host immune responses against the HPV E7 antigen, we linked calreticulin (CRT) to HPV-6b E7 and found that vaccinating C57BL/6 mice with the HPV-6b CRT/E7 DNA vaccine is able to induce a CD8+ T cell response that recognizes an H-2Db-restricted E7aa21-29 epitope. Additionally, vaccination of HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice with HPV-6b CRT/E7 DNA generated a CD8+ T cell response against the E7aa82-90 epitope that was not observed in the wild-type C57BL/6 mice, indicating this T cell response is restricted to HLA-A*0201. In vivo cytotoxic T cell killing assays demonstrated that the vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells are able to efficiently kill target cells. Interestingly, the H-2Db-restricted E7aa21-29 sequence and the HLA-A*0201-restricted E7aa82-90 sequence are conserved between HPV-6b and HPV-11 and may represent shared immunogenic epitopes. The identification of the HPV-6b/HPV-11 CD8+ T cell epitopes facilitates the evaluation of various immunomodulatory strategies in preclinical models. More importantly, the identified HLA-A*0201-restricted T cell epitope may serve as a peptide vaccination strategy, as well as facilitate the monitoring of vaccine-induced HPV-specific immunologic responses in future human clinical trials.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-016-1793-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, Vaccine, T cell epitope, MHC class I, Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis, Immunotherapy

Introduction

HPV types 6 and 11 cause recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) and genital condylomata [1]. The virus induces the proliferation of benign squamous epithelium, most commonly in the larynx, trachea, and other mucosal subsites within the upper aerodigestive tract. Although the overall incidence of RRP is low in the general population, the disease burden can be high for affected individuals, resulting in profound functional deficiencies for airway patency and speech [2]. Clinically, all patients diagnosed with RRP have recurrent growths of papilloma within their upper aerodigestive tract, and the primary treatment modality is surgical debulking of the lesions, as no effective cures have been developed to date. Over 50 % of RRP patients will require multiple surgical interventions over their lifetime to manage the symptoms associated with their disease burden [3]. Given the importance of the immune system in eradicating HPV infections and associated lesions, we are interested in developing targeted immunotherapies against HPV types 6 and 11 with a goal of finding a definitive cure for RRP. One promising treatment option for individuals suffering from RRP is the development of therapeutic HPV vaccines that elicit cytotoxic CD8+ T cells that recognize HPV-specific antigens, such as E6 and E7. Since E6 and E7 are the viral oncoproteins responsible for cellular dysregulation of cell cycle and apoptotic pathways in HPV-associated cancers, these proteins are constitutively expressed by all virally-related cancer cells and, thus, represent promising targets for the development of antigen-specific therapeutic vaccines [4]. The expression of other HPV viral proteins, such as E1 and E2 that contribute to viral DNA replication and E5, which activates receptor tyrosine kinases in a ligand-independent fashion, can be lost upon HPV DNA integration into the host genome. This potential loss of protein expression makes E1, E2, and E5 less robust targets of immunotherapy, as no protein would be available to be processed and presented to the immune system for T cell recognition and eradication of virally-associated cancer cells [4, 5]. Furthermore, long-term immunologic memory can be achieved with these vaccines with the induction of CD4+ T cells. Thus, newly infected cells can be quickly eliminated to prevent disease recurrence [6]. The majority of efforts in developing therapeutic HPV vaccines has focused on the oncogenic HPV types, types 16 and 18, and has resulted in various human clinical trials. Only recently have efforts begun to expand to include the low-risk HPV types 6 and 11 [7].

We previously reported on the development and efficacy of a DNA vaccine (pcDNA3-HPV-11 E6E7) that targets the HPV-11 E6 and E7 antigens. We reported that the vaccine was capable of generating a robust HPV-11 E6-specific CD8+ T cell immune response in C57BL/6 mice [8]; however, we failed to detect any E7-specific CD8+ T cell immune responses. The lack of E7-specific CD8+ T cell responses suggests that E7 is either weakly or non-immunogenic in our preclinical murine model. Linkage of calreticulin (CRT) with HPV-16 E7 was able to induce a dramatic increase in E7-specific CD8+ T cell responses with a resulting antitumor effect against E7-expressing tumors [9]. In the current study, we hypothesize that linking the immunostimulatory CRT to HPV-6b E7 (pcDNA3-CRT/HPV-6b E7) can enhance E7-specific CD8+ T cell responses in the host after vaccination. Thus, we administer the novel DNA vaccine and identify the immunogenic epitopes recognized by the vaccine-induced E7-specific CD8+ T cells in both the C57BL/6 and Dd/HLA-A2 transgenic mice in order to facilitate the monitoring of various immunomodulatory strategies which target this HPV type in both the preclinical and clinical setting.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 female mice (5- to 8-week olds) were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). HLA-A*0201/Dd (AAD) transgenic mice with a C57BL/6 background were kindly provided by Victor Engelhard at the University of Virginia Health Sciences Center. These transgenic mice express a chimeric HLA class I molecule comprising the α-1 and α-2 domains of HLA-A*0201 and the α-3 transmembrane and cytoplasmic domain of H-2Dd. The mouse α-3 domain expression enhances the immune response in this system. Compared to the unmodified HLA-A2.1, the chimeric HLA-A2.1/H2-Dd MHC class I molecule mediates efficient positive selection of murine T cells to provide a more complete T cell repertoire capable of recognizing peptides presented by HLA-A2.1 class I molecules. All animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions, and all applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Peptides, antibodies, and other reagents

Seven HPV6b E7 overlapping peptides (18–30 amino acids in length and overlapping by 10 amino acids) that span the full length of E7 protein, and HPV6b E7aa21-29, E7aa28-37, E7aa31-40, and E7aa82-90 peptides were synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). The identities of the peptides were validated by mass spectrometric analysis, and the purity of the peptides was confirmed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2), PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD8a (clone 53.6.7), and PE-conjugated anti-active caspase-3 antibodies were purchased from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Histidine-rich amphipathic peptide LAH4 (sequence: KKALLALALHHLAHLALHLALALKKA) was synthesized by GenScript. CpG-ODN 1826 (CpG) was synthesized by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). CFSE was purchased from BD PharMingen.

Cell lines

HPV-16 E6- and E7-expressing TC-1 tumor cells were generated as previously described [10]. Establishment of TC-1 cells that express a chimeric HLA-A2/Dd gene has been described previously [11]. The cells were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10 % fetal bovine serum. The 293 cell line (ATCC Cat. No. CRL-1573) is a human embryonic kidney cell line, and 293 cells expressing the murine MHC class I molecule Kb have been described previously [12]. To generate 293 cells expressing the murine MHC class I molecule, Db, 293 cells were stably transfected with pcDNA3-Db. All cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10 % fetal bovine serum.

DNA vaccine

To generate the DNA vaccine constructs, the codon optimized HPV-6b E7 sequence was synthesized by GenScript and cloned into the pcDNA3 vector to generate the pcDNA3-HPV-6b E7 vaccine as well as cloned into the pcDNA3-CRT backbone vector to generate the pcDNA3-CRT/HPV-6b E7 vaccine [9]. All plasmid constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing, and the DNA was prepared using an endotoxin-free kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

DNA vaccination

DNA-coated gold particles were delivered to the shaved abdominal region of mice using a helium-driven gene gun (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to a protocol described previously [13]. Mice were immunized with 2 μg of the DNA vaccine and received two boosters at one-week intervals.

Vaccination with HPV6b E7 peptide formulated with LAH4 and CpG

To vaccinate mice with the HPV-6b E7 peptide formulated with LAH4 and CpG, 30 μg of HPV-6b E7 peptide was mixed with 30 μg of LAH4 and 3 μg of CpG1826 in a final volume of 50 μl and then incubated at room temperature for 30 min prior to subcutaneous injection. The mice were boosted twice at one-week intervals.

Intracellular cytokine staining

Splenocytes (5 × 106 cells) from each experimental group were incubated for 20 h with 1 µg/ml of the indicated peptide in the presence of 1 µl/ml of GolgiPlug (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). As a positive control for the assay, cells were stimulated with Cell Stimulation Cocktail which contains both phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) in the presence of GolgiPlug for 3 h. Alternatively, when a specific CD8+ T cell line was used, T cells were co-cultured with peptide-pulsed 293, 293-Db, or 293-Kb cells (E:T ratio of 2:1) in the presence of 1 µl/ml of GolgiPlug. The stimulated cells were washed with FACS buffer and stained with PE-conjugated anti-mouse CD8a. The cells were fixed using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Staining for intracellular IFN-γ was performed with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IFN-γ. Cells were acquired with the FACSCalibur flow cytometry machine and analyzed with CELLQuest Pro software.

Establishment of T cell lines

Splenocytes from pcDNA3-CRT/HPV-6b E7-immunized C57BL/6 mice were harvested one week after the last vaccination. These splenocytes were stimulated with HPV-6b E7aa21-29 peptide in the presence of murine IL-2 (20 U/ml). The cells were restimulated every week with E7aa21-29 peptide-pulsed and irradiated TC-1 cells. To establish the HLA-A2/Dd-restricted E7aa82-90 peptide-specific CD8+ T cell line, splenocytes from HPV6b E7aa69-90 peptide-vaccinated HLA-A2/Dd mice were stimulated with HPV-6b E7aa82-90 peptide in the presence of murine IL-2 (20 U/ml). The cells were restimulated every week with E7aa82-90 peptide-pulsed and irradiated TC-1/HLA-A2/Dd cells.

In vitro cytotoxic T cell assay

For the in vitro CTL assay, TC-1 and TC-1/HLA-A2/Dd cells were pulsed with HPV-6b E7aa82-90 peptide. After extensive washing, these cells were incubated for 4 h with an E7aa82-90 peptide-specific CD8+ T cell line at various E:T ratios at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. The cells were then harvested and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD8a. The cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with PE-conjugated anti-active caspase-3 antibody according to the manufacturer’s instructions and acquired by flow cytometry. The percentage of apoptotic tumor cells was determined by gating on the CD8− and active caspase-3+ cell populations.

In vivo cytotoxic T cell assay

To perform the in vivo cytotoxic T cell assay, HLA-A2/Dd mice were vaccinated subcutaneously with HPV-6b E7aa69-90 peptide formulated with LAH4 and CpG, or with LAH4 and CpG only, and boosted twice with the same regimen at one-week intervals. One week after the last vaccination, splenocytes from naïve C57BL/6 mice were divided into two populations. The first population was labeled with 5 μM CFSE (CFSEhi) and pulsed with 2 μg/ml of E7aa82-90 peptide. The other population was labeled with 0.05 μM CFSE (CFSElo). The two populations were then mixed at a ratio of 1:1. 3 × 107 cells were injected into either HPV-6b E7aa69-90 peptide-vaccinated or control mice intravenously. Eighteen hours later, peripheral blood cells were collected for analysis of specific cytotoxic activity by flow cytometry. Antigen-specific cytotoxic activity was calculated based on the formula: percentage of specific killing = (1 − CFSEhi/CFSElo) × 100.

Statistical analysis

Data expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) are representative of a minimum of two separate experiments. Comparisons between individual data points were made by two-tailed student’s t test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

HPV-6b E7 is a poorly immunogenic antigen in the preclinical model

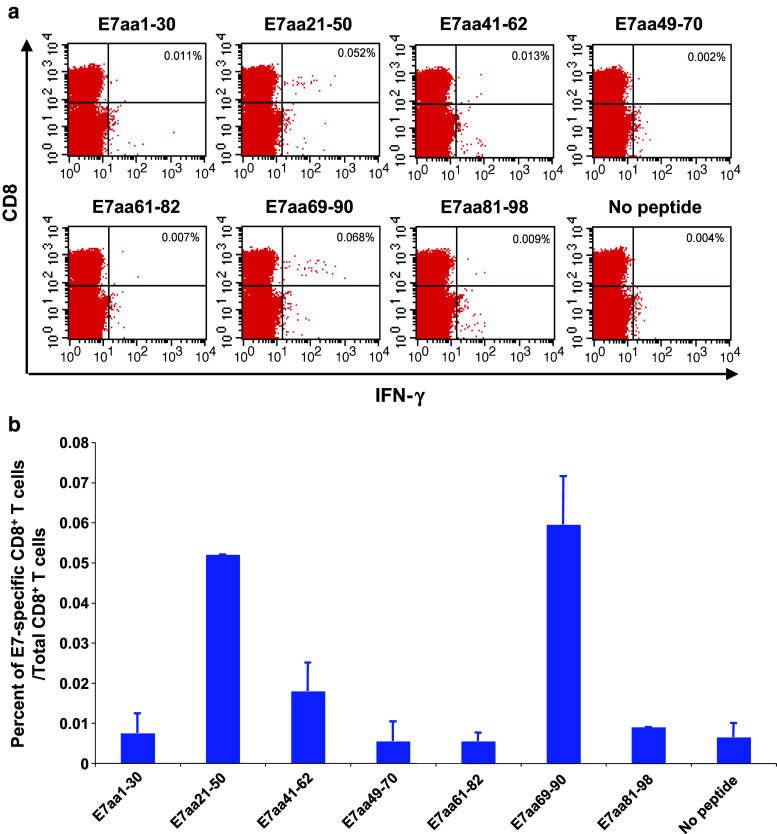

Given that no detectable E7-specific CD8+ T cell responses were observed with our previously developed HPV-11 E6/E7 DNA vaccine, we sought to understand the immunogenicity of HPV-6b E7 in our preclinical model [8]. Briefly, C57BL/6 mice were vaccinated with pcDNA3-HPV-6b E7 DNA. The mice were boosted twice with the same regimen at one-week intervals. One week after the last vaccination, splenocytes were harvested and incubated with HPV-6b E7 overlapping peptides that spanned the entire E7 protein. The frequency of E7-specific CD8+ T cells was evaluated by intracellular cytokine staining followed by flow cytometry analysis. As shown in Fig. 1a, mice vaccinated with pcDNA3-HPV-6b E7 DNA did not elicit E7-specific CD8+ T cells within the splenocytes. As a positive control, splenocytes were also stimulated with PMA/ionomycin. Thus, our data indicate that HPV-6b E7 is a poorly immunogenic antigen in our preclinical model.

Fig. 1.

Linkage of HPV6b E7 to calreticulin (CRT) induced CD8+ T cell responses specific for HPV6b E7aa21-50 peptide as compared to E7 alone. Five- to eight-week-old C57BL/6 mice (5 mice/group) were vaccinated with either 2 μg of pcDNA3-HPV6b E7 or 2μg of pcDNA3-HPV6b CRT/E7 DNA via intradermal delivery (gene gun) and were boosted twice with the same regimen at seven-day intervals. One week after the last vaccination, splenocytes were stimulated with the indicated HPV6b E7 overlapping peptide (1 μg/ml) in the presence of GolgiPlug overnight at 37 °C. Splenocytes stimulated with PMA and ionomycin in the presence of GolgiPlug for 3 h were used as a positive control. The splenocytes were then analyzed by flow cytometry for the presence of HPV6b E7 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells by staining for cell surface CD8 and intracellular IFN-γ. a Summary of the frequency of HPV6b E7 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells elicited after pcDNA3-HPV6b E7 DNA vaccination. b Summary of the frequency of HPV6b E7 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells elicited after pcDNA3-HPV6b CRT/E7 DNA vaccination

Linkage of HPV-6b E7 to calreticulin induced CD8+ T cell responses that recognize the HPV-6b E7aa21-50 peptide

Linkage of HPV16 E7 to CRT, a heat shock-related chaperone protein that enhances antigen processing and activation of antigen-presenting cells, has been shown to elicit a dramatic increase in E7-specific CD8+ T cell responses [9]. Thus, we evaluated this retargeting strategy with the HPV-6b E7 antigen by linking HPV-6b E7 to CRT [9]. We vaccinated C57BL/6 mice with the pcDNA3-CRT/HPV-6b E7 DNA. Mice were boosted twice with the same regimen at one-week intervals. One week after the last vaccination, splenocytes were isolated and stimulated with various HPV-6b E7 overlapping peptides. Splenocytes were then stained for cell surface CD8 and intracellular IFN-γ and analyzed by flow cytometry. Mice vaccinated with the pcDNA3-CRT/HPV-6b E7 DNA and stimulated with the E7aa21-50 peptide elicited the greatest number of IFN-γ secreting E7-specific CD8+ T cells compared to the other peptide-stimulated groups (Fig. 1b). These data suggest that linkage of HPV-6b E7 to CRT is able to increase the immunogenicity of the E7 antigen, and the immunogenic epitope is contained within the E7aa21-50 peptide sequence. Although the level of vaccine-induced E7-specific CD8+ T cells was modest, this may reflect the timing of the immunologic assay, which was one week after the third vaccination, rather than reflect vaccine potency.

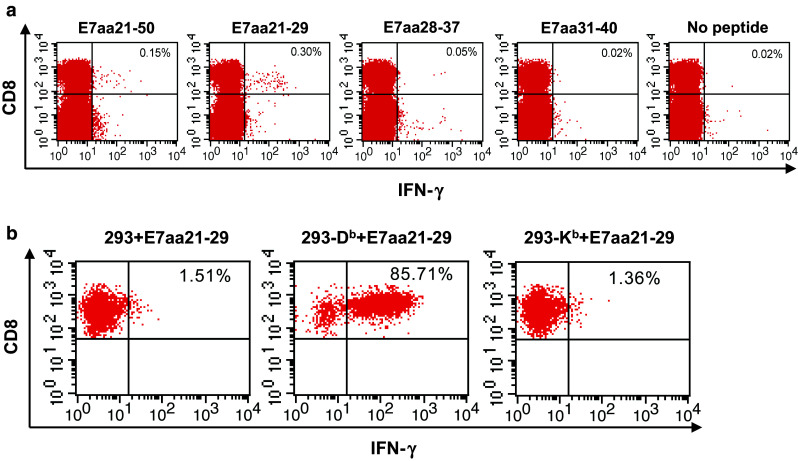

HPV-6b E7aa21-50 peptide contains the H-2Db-restricted CTL epitope E7aa21-29

In order to define the immunogenic epitope within HPV-6b E7, we utilized the BIMAS and SYFPEITHI programs to predict the binding affinity of various HPV-6b E7 peptide sequences to MHC class I molecules. BIMAS uses known binding motifs and established peptide binding to MHC molecules to provide computational predictions of peptides contained within MHC class I binding clefts. SYFPEITHI is a database of published and verified peptides that are known to bind MHC molecules. The predictive analyses identified several peptide sequences that have a high binding affinity to H-2Db or H-2 Kb as compared with other putative hits (Table 1). Three of the identified peptides, E7aa21-29, E7aa28-37, and E7aa31-40, contained within the E7aa21-50 peptide sequence were selected to stimulate the splenocytes isolated from pcDNA3-CRT/HPV-6b E7 DNA-vaccinated mice. As shown in Fig. 2a and consistent with results from Fig. 1b, the E7aa21-50 peptide was able to stimulate the CD8+ T cells in splenocytes to produce IFN-γ. Among the three peptides identified by computational predictions, the E7aa21-29 peptide generated the greatest number of IFN-γ secreting CD8+ T cells. These data suggest that this peptide represents the most immunogenic epitope within the E7aa21-50 peptide sequence, and E7aa21-29 is the immunodominant epitope recognized by T cells induced by pcDNA3-CRT/HPV-6b E7 DNA vaccination. Next, we wanted to determine the MHC restriction of the E7aa21-29 peptide by generating a T cell line using E7aa21-29-pulsed syngeneic murine splenocytes. This CTL line was then stimulated with either the parental 293 cells or 293 cells overexpressing either the H-2Db or H-2 Kb molecules, pulsed with E7aa21-29 peptide. E7aa21-29 peptide-pulsed 293-Db cells generated the highest number of CD8+ T cells in comparison with E7aa21-29 peptide-pulsed 293-Kb cells or the 293 parental cell line (Fig. 2b). Thus, our data demonstrate that the immunogenic E7aa21-29 epitope is restricted by H-2Db.

Table 1.

Candidate H-2b-restricted CTL epitopes in the HPV-6b E7 aa21-50 peptide sequence

| Restriction element | Peptide length | BIMAS | SYFPEITHI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide sequence | Position | Score | Peptide sequence | Position | Score | ||

| Db | 8 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| 9 | VGLHCYEQL | 21–29 | 18.6 | VGLHCYEQL | 21–29 | 17 | |

| 10 | QLVDSSEDEV | 28–37 | 0.2 | DSSEDEVDEV | 31–40 | 14 | |

| Kb | 8 | GLHCYEQL | 22–29 | 26.4 | GLHCYEQL | 22–29 | 22 |

| 9 | VGLHCYEQL | 21–29 | 24 | VGLHCYEQL | 21–29 | 0 | |

| 10 | HCYEQLVDSS | 24–33 | 0.6 | N/A | |||

Fig. 2.

Mapping of HPV6b E7 CD8+ T cell epitope. a Representative flow cytometry of IFN-γ secretion by CD8+ T cells after HPV6b E7 eptide incubation, as indicated. Splenocytes of pcDNA3-HPV6b CRT/E7 DNA-vaccinated C57BL/6 mice (5 mice/group) were stimulated with either HPV6b E7aa21-50 or HPV6b E7aa21-29, E7aa28-37, or E7aa31-40 peptide (1 μg/ml) in the presence of GolgiPlug overnight at 37 °C. The HPV6b E7 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells were then analyzed by staining for cell surface CD8 and intracellular IFN-γ. b Determination of MHC restriction of HPV6b E7 peptide recognized by CD8+ T cells after HPV6b CRT/E7 DNA vaccination. HPV6b E7aa21-29 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells were stimulated with E7aa21-29 peptide-pulsed 293 cells or 293 cells expressing either the H-2Db or H-2Kb molecules in the presence of GolgiPlug overnight at 37 °C. The activation of CD8+ T cells was then analyzed by staining for cell surface CD8 and intracellular IFN-γ, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The number in the upper right quadrant represents the percent of HPV6b E7 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells out of the total CD8+ T cells

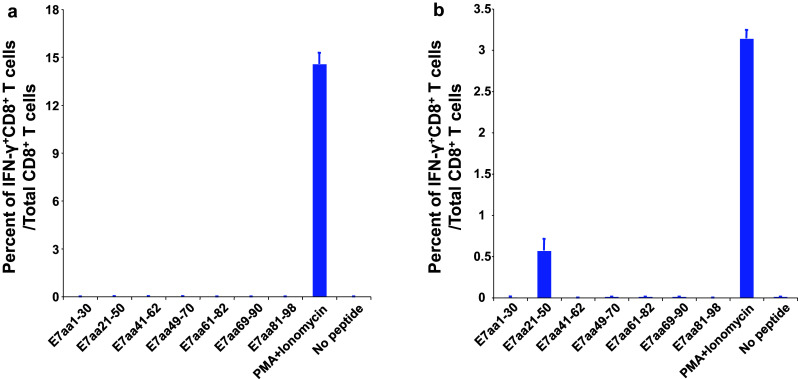

Vaccination with pcDNA3-CRT/HPV-6b E7 DNA vaccine in HLA-A2/Dd transgenic mice generates an A2-restricted HPV-6b E7 peptide-specific CD8+ T cell response

We demonstrated that linkage of CRT to HPV-6b E7 is able to significantly enhance the immunogenicity of HPV-6b E7. We also identified the immunodominant epitope, E7aa21-29, recognized by CD8+ T cells after vaccination in C57BL/6 mice. We were next interested in evaluating the E7 peptide sequence that could be recognized in humans if vaccinated with the HPV-6 CRT/E7 DNA vaccine. Therefore, we evaluated the E7-specific T cell responses in transgenic mice expressing the human major histocompatibility (MHC) class I molecule, HLA-A2, which is expressed in 50 % of the Caucasian population. HLA-A2 transgenic mice with a C57BL/6 background, containing an HLA-A2/Dd chimeric MHC class I gene, were vaccinated with 2 μg of pcDNA3-CRT/HPV-6b E7 DNA. The mice received booster vaccinations at one-week intervals. One week after the last vaccination, splenocytes were isolated and stimulated with overlapping HPV-6 E7 peptides. We found that vaccination of HLA-A2 transgenic mice with HPV-6 CRT/E7 generated a CD8+ T cell response against the E7aa69-90 peptide, in addition to the E7aa21-50 previously characterized in wild-type C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 3). The additional CD8+ T cell response against the E7aa69-90 peptide was only present in the HLA-A2 transgenic mice and not in the wild-type C57BL/6 mice (see Fig. 1b). The response observed only in the HLA-A2 transgenic but not in wild-type C57BL/6 mice suggests that the CD8+ T cell response may be restricted to E7aa69-90 peptide processing and presentation on the human HLA-A2 MHC class I molecule.

Fig. 3.

pcDNA3-HPV6b CRT/E7 DNA vaccination in HLA-A2 transgenic mice generates an A2-restricted E7-specific CD8+ T cell response. Five- to eight-week-old HLA-A2 transgenic mice with a C57BL/6 background (HLA-A2/Dd mice, 5 mice/group) were vaccinated with 2 μg of pcDNA3-HPV6b CRT/E7 DNA via intradermal delivery (gene gun) and were boosted twice with the same regimen at seven-day intervals. One week after the last vaccination, splenocytes were prepared and stimulated with the indicated HPV6b E7 overlapping peptide (1 μg/ml) in the presence of GolgiPlug overnight at 37 °C. The HPV6b E7 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells were then analyzed with flow cytometry by staining for cell surface CD8 and intracellular IFN-γ. a Representative flow cytometry data. b Summary of the flow cytometry data. The number in the upper right quadrant represents the percent of HPV6b E7 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells out of the total CD8+ T cells isolated from splenocytes

HPV-6b E7aa82-90 contains the HLA-A2-restricted CD8+ T cell epitope

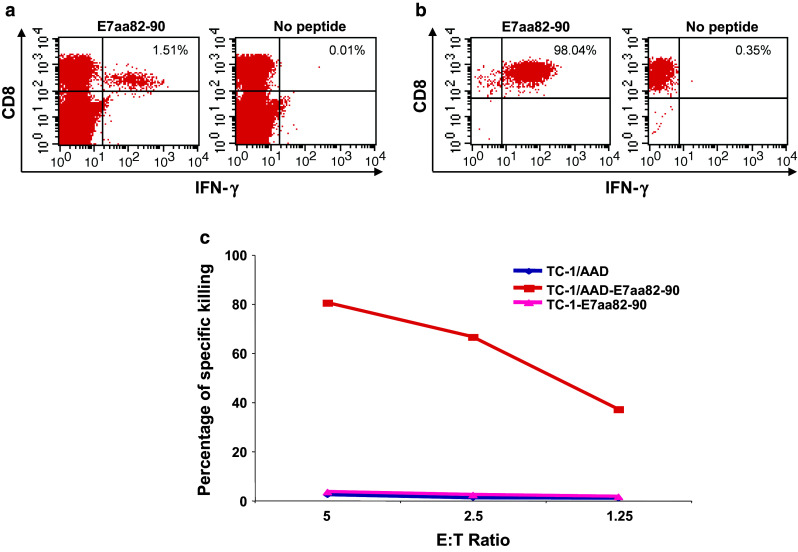

In order to confirm the HLA-A2-restricted CD8+ T cell immunogenic epitope is contained within the E7aa69-90 peptide, HLA-A2/Dd mice were vaccinated subcutaneously with HPV-6b E7aa69-90 peptide together with LAH4 and CpG since LAH4 and CpG have been previously shown to enhance peptide internalization and peptide-specific immune responses, respectively [14]. In addition, we utilized T cell epitope prediction algorithms to further narrow the potential candidate within this sequence range (Table 2). The predictive analyses identified only two peptide sequences that had a strong binding affinity to HLA-A2, and both contained the E7aa82-90 sequences. Thus, the core peptide sequence, E7aa82-90 was chosen to stimulate the splenocytes from the vaccinated mice, and peptide-specific CD8+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Vaccination generated a strong E7-specific CD8+ T cell immune response in splenocytes (Fig. 4a) that recognize the E7 peptide, E7aa82-90. To test whether CD8+ T cell recognition of the E7aa82-90 peptide is restricted by HLA-A*0201 and can result in functional killing by the T cell, we generated a HPV-6b E7aa82-90 CD8+ T cell line by stimulating splenocytes with the HPV-6b E7aa82-90 peptide pulsed onto irradiated TC-1/HLA-A2/Dd cells (Fig. 4b). Next, we co-cultured the E7aa82-90 CD8+ T cells with E7aa82-90 peptide pulsed with either TC-1 or TC-1/HLA-A2/Dd cells at the various effector-to-target (E:T) ratios. As a control, we co-cultured the E7aa82-90 CD8+ T cells with TC-1/HLA-A2/Dd cells without peptide. The cells were then stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD8a followed by intracellular active caspase-3 with PE-conjugated anti-caspase-3 antibody. As shown in Fig. 4c, HPV-6b E7aa82-90 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells are effective in killing E7aa82-90 peptide-pulsed TC-1/HLA-A2/Dd, but not E7aa82-90 peptide-pulsed TC-1 cells, indicating that HPV-6b E7aa82-90 peptide recognition by CD8+ T cell is HLA-A*0201-restricted and immunogenic.

Table 2.

Candidate HLA-A*0201-restricted CTL epitopes in the HPV-6b E7 aa69-90 peptide

| Restriction element | Peptide length | BIMAS | SYFPEITHI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide sequence | Position | Score | Peptide sequence | Position | Score | ||

| HLA-A*0201 | 8 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| 9 | LLLGTLNIV | 82–90 | 412.5 | LLLGTLNIV | 82–90 | 31 | |

| 10 | QLLLGTLNIV | 81–90 | 242.7 | QLLLGTLNIV | 81–90 | 27 | |

Fig. 4.

Characterization of HLA-A2-restricted HPV6b E7-specific CD8+ T cells generated after HPV 6b CRT/E7 DNA vaccination. a Five- to eight-week-old female HLA-A2/Dd mice (3 mice/group) were vaccinated subcutaneously with HPV6b E7aa69-90 peptide formulated with the histidine-rich amphipathic peptide LAH4 and CpG 1826 and boosted twice at one-week intervals. One week after the last vaccination, splenocytes were isolated and stimulated with HPV6b E7aa82-90 peptide (1 μg/ml) in the presence of GolgiPlug overnight at 37 °C. The HPV6b E7 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells were then analyzed by staining for cell surface CD8 and intracellular IFN-γ, followed by flow cytometry analysis. b Establishment of the HPV6b E7aa82-90 peptide-specific CD8+ T cell line. The above splenocytes were stimulated with HPV6b E7aa82-90 peptide-pulsed, irradiated TC-1/HLA-A2/Dd cells to establish the T cell line. The specificity of the T cell line was confirmed by intracellular IFN-γ staining. c HPV6b E7aa82-90 peptide recognition by CD8+ T cell is HLA-A*0201-restricted. HPV6b E7aa82-90 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells were co-incubated with either HPV6b E7aa82-90 peptide-pulsed TC-1 cells or TC-1/AAD cells at the indicated E:T ratio for 5 h. The killing of TC-1 cells or TC-1/AAD cells was then measured by active caspase-3 staining

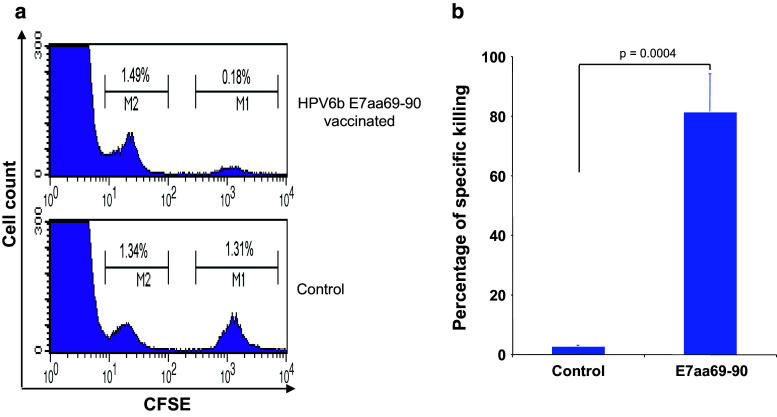

HPV-6b E7aa69-90 peptide vaccination induces E7aa82-90 peptide-specific CD8+ T cell responses with cytotoxic activity in vivo

In order to test whether vaccine-induced HPV-6b E7aa82-90-specific CD8+ T cells are functional in vivo, HLA-A2/Dd transgenic mice were vaccinated with either HPV-6b E7aa69-90 peptide with LAH4 and CpG, or with LAH4 and CpG only. The mice were vaccinated with the HPV-6b E7aa69-90 peptide rather than the pcDNA3-CRT/HPV-6b E7 DNA vaccine in order to minimize any potential competition with the immunogenic E7aa21-29 epitope, which is restricted by the endogenous H-2Db in the C57BL/6 mice. Seven days after the last vaccination, splenocytes from naïve C57BL/6 mice were divided into two groups and labeled with different concentrations of CFSE. One group was labeled with 5 μM CFSE (CFSEhi) and pulsed with 2 μg/ml of E7aa82-90 peptide, and the other group was labeled with 0.05 μM CFSE (CFSElo) only. The two groups were then mixed in a 1:1 ratio. Subsequently, the cells were injected intravenously into HPV-6b E7aa69-90 peptide-vaccinated mice and unvaccinated control mice. Peripheral blood cells were collected 18 h later for the analysis of specific cytotoxic activity by flow cytometry. Mice vaccinated with HPV-6b E7aa69-90 peptide formulated with LAH4 and CpG, but not LAH4- and CpG-vaccinated mice, were able to kill the peptide-pulsed splenocytes (CFSEhi) (Fig. 5). These results demonstrate that vaccine-induced HPV-6b E7aa82-90 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells are able to kill specific target cells in vivo.

Fig. 5.

HPV6b E7aa69-90 peptide vaccination induces E7aa82-90 peptide-specific CD8+ T cell responses with cytotoxic activity in vivo. a Five- to eight-week-old female HLA-A2/Dd mice (3 mice/group) were vaccinated subcutaneously with HPV6b E7aa69-90 peptide formulated with LAH4 and CpG, or with LAH4 and CpG only, boosted twice with the same regimen at one-week intervals. Splenocytes from naïve C57BL/6 mice were divided into two populations. The first group was labeled with 5 μM CFSE (CFSEhi) and pulsed with 2 μg/ml of E7aa82-90 peptide. The other population was labeled with 0.05 μM CFSE (CFSElo). The two populations were then mixed at the ratio of 1:1. 3 × 107 of these cells were injected into either HPV6b E7aa69-90 peptide-vaccinated or control mice intravenously. Eighteen hours later, peripheral blood cells were collected for the analysis of specific cytotoxic activity by flow cytometry. Specific cytotoxic activity was expressed as the ratio between CFSElo over CFSEhi populations. b Summary of specific in vivo cytotoxic activity

Discussion

The majority of therapeutic vaccine efforts have focused on targeting the high-risk HPV types, such as HPV-16 and HPV-18, due to the etiologic association with cervical cancer and a subset of head and neck cancers. Recently, therapeutic vaccines targeting low-risk HPV types, such as types 6 and 11, have garnered interests because there is increasing evidence that these viral types can not only cause chronic benign diseases, such as RRP and genital warts, but can also contribute to a small number of carcinomas of the lung, tonsil, and larynx [15]. By generating synthetic HPV-6b or HPV-11 peptides that contain a HLA-A2-binding motif, Tarpey et al. found that human cytotoxic T lymphocytes stimulated by endogenously processed HPV-11 E7 recognize a HLA-A2-restricted peptide, E7aa4-12 [16]. They also found two additional HPV-6b E7 peptides (E7aa21-30 and aa47-55) elicited HLA-A2-restricted CTLs. Interestingly, Xu et al. [17] identified the HPV-11 E7aa7-15 peptide as a potential HLA-A2-restricted CTL epitope with the assistance of a computer algorithm and confirmed the epitope by a functional T cell assay using HLA-A2-restricted HPV-11 E7 peptide-loaded dendritic cells. Furthermore, Zhao et al. [18] have reported that linkage of CRT to HPV-6b E7 generated more efficient E7-specific immune responses than E7 alone. However, the T cell epitopes recognized by the vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells were not identified.

More recently, Shin et al. [7] reported on DNA vaccines that targeted HPV-6 and HPV-11 by encoding the respective E6 and E7 genes. Vaccination in C57BL/6 mice with three doses of 20 μg of the DNA plasmid, followed by intramuscular injection and CELLECTRA® electroporation, at 14-day intervals elicited strong T cell responses. After characterization of the vaccine-induced T cell responses, the authors identified an E6aa40-54 immunodominant peptide, which supported our prior findings [8]. Although they did not detect HPV-6 E7-specific T cells, the authors were able to elicit HPV-11 E7aa24-38 peptide-specific T cell responses. The murine CD8+ T cell epitope for HPV-6b E7 identified in our study (E7aa21-29) overlaps with the immunogenic peptide sequence the group identified in HPV-11 E7. Interestingly, IFN-γ secreting CD4+ T cell responses in the HPV6 E6/E7-vaccinated groups was reported at a low frequency of 0.163 % and, in the HPV11 E6/E7-vaccinated groups, the IFN-γ secreting CD4+ T cell responses were even lower at 0.051 %. Compared to our current study, the DNA dose, route of vaccination administration, and schedule from Shin’s report are different (2 μg versus 20 μg of DNA, gene gun delivery versus intramuscular injection followed by electroporation, weekly vaccination as compared to vaccination every 14 days). The vaccine dose, route of DNA vaccine administration and schedule can impact the magnitude of T cell responses; however, none of these variables would impact the processing of the immunogenic E7 epitopes presented on the H-2Db and the HLA-A*0201 molecules. Since our DNA vaccine incorporates the entire E7 gene, we expect that our vaccine would also elicit CD4+ T cell responses, and it would be interesting in future studies to determine whether linkage of CRT to E7 would increase the number of vaccine-induced CD4+ T cells, through cross-presentation, which would be important in generating lasting memory T cell responses.

Matijevic et al. evaluated the potential of vaccine-induced E7-specific CD8+ T cells to cross-react across the HPV types. Using a predictive algorithm, Matijevic et al. found that the CD8+ T cells elicited after immunization with an amolimogene bepiplasmid DNA vaccine (formally ZYC101a, expressing antigenic regions of HPV16 and 18) in patients with HPV-associated high-grade cervical dysplasia could cross-react with a HLA-A2-restricted HPV-6/11 E7 CD8+ T cell epitope. Their identified epitope, E7aa82-90, is identical to the epitope recognized by the CD8+ T cells induced with our HPV-6b targeted DNA vaccine in the preclinical HLA-A2/Db transgenic model [19]. To evaluate the homology of the E7 protein and/or, specifically, the immunogenic region of E7aa82-90 across the four HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18, we performed amino acid sequence alignment analysis of the E7 protein using Clustal Omega analysis (Supplementary Figure 1). We found that the E7 protein had an average conservation of 55.7 %, ranging from 42.27 % between the high-risk types (HPV-16 and HPV-18), 56.25–57.29 % between high- and low-risk types (HPV-16/HPV-18 and HPV-6b/HPV-11), to 84.69 % between the low-risk types (HPV-6b and HPV-11). Additionally, a nearly 100 % conserved DIR motif was found in E7aa86-88. This DIR motif could represent the common amino acid sequence crucial for recognition by CD8+ T cells, independent of the HPV type. Thus, it would be interesting to evaluate whether the HLA-A2-restricted HPV-6b E7aa82-90 CD8+ T cells induced by our DNA vaccine are able to cross-react to the HLA-A2-restricted HPV-16/18 E7 CD8+ T cell epitopes to demonstrate vaccine-induced protection across the HPV types [20].

In our study, we found that E7 is a poorly immunogenic antigen in C57BL/6 mice despite vaccination with an E7-encoding DNA vaccine. We enhanced the immunogenicity of the E7 antigen by retargeting the antigen to the MHC class I processing and presentation pathway by linking E7 to CRT. Calreticulin (CRT) has multiple cellular functions. CRT has been shown to associate with peptides that are delivered to the transporters associated with antigen processing (TAP1 and TAP2) and MHC class I-β2 microglobulin, resulting in increased efficiency of epitope presentation [21]. Additionally, CRT has been shown to have anti-angiogenic properties by inhibiting the proliferation of endothelial cells that line newly formed blood vessels [22]. While our study only focused on the ability of CRT to increase antigen processing and presentation, CRT could have an additional benefit in vivo by hindering the formation of angiogenic vessels associated with RRP. We found that vaccination of C57BL/6 mice with HPV-6b CRT/E7 elicits a significant number of CD8+ T cells that recognize an H-2Db-restricted E7aa21-29 epitope. We also demonstrated that vaccination of HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice with HPV-6b CRT/E7 DNA vaccine generates CD8+ T cells that recognize a HLA-A*0201-restricted E7aa82-90 epitope. More importantly, these HLA-A*0201-restricted CD8+ T cells are able to kill specific target cells efficiently in vivo.

The limitations of our study are that we were unable to assess the in vivo anti-tumor response to the DNA or peptide vaccine in preclinical models due to the absence of appropriate tumor cell lines expressing the corresponding HPV antigens and MHC molecules. Furthermore, the immunogenicity of the E7aa82-90 epitope needs to be confirmed in human subjects with RRP expressing the HLA-A2 allele and its biologic significance confirmed with human based T cell functional assays.

Sequence homology search of the E7 antigen showed that both the HPV-6b and HPV-11 viral types share identical sequences for the relevant regions for CD8+ T cell recognition, and thus, both viral types can be targeted with various E7 peptide vaccination strategies. Our current study identifies the peptide epitopes presented on both murine and human MHC class I molecules that can be recognized by CD8+ T cells. The identification of the HPV-6b and HPV-11 T cell epitopes should greatly facilitate the development of immunologic assays focused on assessing various immunomodulatory strategies that target HPV-6b and HPV-11 in both preclinical models and in human clinical trials.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research 1R01CA181538-01A1 (Sara I. Pai).

Abbreviations

- CRT

Calreticulin

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- HPV

Human papillomavirus

- RRP

Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Derkay CS, Darrow DH. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115:1–11. doi: 10.1177/000348940611500101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallagher TQ, Derkay CS. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: update 2008. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16:536–542. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328316930e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preuss SF, Klussmann JP, Jungehulsing M, Eckel HE, Guntinas-Lichius O, Damm M. Long-term results of surgical treatment for recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:1196–1201. doi: 10.1080/00016480701200350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker CC, Phelps WC, Lindgren V, Braun MJ, Gonda MA, Howley PM. Structural and transcriptional analysis of human papillomavirus type 16 sequences in cervical carcinoma cell lines. J Virol. 1987;61:962–971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.4.962-971.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiMaio D, Mattoon D. Mechanisms of cell transformation by papillomavirus E5 proteins. Oncogene. 2001;20:7866–7873. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnelly JJ, Ulmer JB, Shiver JW, Liu MA. DNA vaccines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:617–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin TH, Pankhong P, Yan J, Khan AS, Sardesai NY, Weiner DB. Induction of robust cellular immunity against HPV6 and HPV11 in mice by DNA vaccine encoding for E6/E7 antigen. Hum Vaccine Immunother. 2012;8:470–478. doi: 10.4161/hv.19180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng S, Best SR, Hung CF, et al. Characterization of human papillomavirus type 11-specific immune responses in a preclinical model. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:504–510. doi: 10.1002/lary.20745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng WF, Hung CF, Chai CY, Hsu KF, He L, Ling M, Wu TC. Tumor-specific immunity and antiangiogenesis generated by a DNA vaccine encoding calreticulin linked to a tumor antigen. J Clin Investig. 2001;108:669–678. doi: 10.1172/JCI200112346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin KY, Guarnieri FG, Staveley-O’Carroll KF, Levitsky HI, August JT, Pardoll DM, Wu TC. Treatment of established tumors with a novel vaccine that enhances major histocompatibility class II presentation of tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 1996;56:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng S, Trimble C, He L, Tsai YC, Lin CT, Boyd DA, Pardoll D, Hung CF, Wu TC. Characterization of HLA-A2-restricted HPV-16 E7-specific CD8(+) T-cell immune responses induced by DNA vaccines in HLA-A2 transgenic mice. Gene Ther. 2006;13:67–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang CH, Peng S, He L, Tsai YC, Boyd DA, Hansen TH, Wu TC, Hung CF. Cancer immunotherapy using a DNA vaccine encoding a single-chain trimer of MHC class I linked to an HPV-16 E6 immunodominant CTL epitope. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1180–1186. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CH, Wang TL, Hung CF, Yang Y, Young RA, Pardoll DM, Wu TC. Enhancement of DNA vaccine potency by linkage of antigen gene to an HSP70 gene. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1035–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang TT, Kang TH, Ma B, Xu Y, Hung CF, Wu TC. LAH4 enhances CD8+ T cell immunity of protein/peptide-based vaccines. Vaccine. 2012;30:784–793. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonagura VR, Hatam LJ, Rosenthal DW, de Voti JA, Lam F, Steinberg BM, Abramson AL. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: a complex defect in immune responsiveness to human papillomavirus-6 and -11. APMIS. 2010;118:455–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2010.02617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarpey I, Stacey S, Hickling J, Birley HD, Renton A, McIndoe A, Davies DH. Human cytotoxic T lymphocytes stimulated by endogenously processed human papillomavirus type 11 E7 recognize a peptide containing a HLA-A2 (A*0201) motif. Immunology. 1994;81:222–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Y, Zhu KJ, Chen XZ, Zhao KJ, Lu ZM, Cheng H. Mapping of cytotoxic T lymphocytes epitopes in E7 antigen of human papillomavirus type 11. Arch Dermatol Res. 2008;300:235–242. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0837-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao KJ, Cheng H, Zhu KJ, et al. Recombined DNA vaccines encoding calreticulin linked to HPV6bE7 enhance immune response and inhibit angiogenic activity in B16 melanoma mouse model expressing HPV 6bE7 antigen. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;298:64–72. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0659-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matijevic M, Hedley ML, Urban RG, Chicz RM, Lajoie C, Luby TM. Immunization with a poly (lactide co-glycolide) encapsulated plasmid DNA expressing antigenic regions of HPV 16 and 18 results in an increase in the precursor frequency of T cells that respond to epitopes from HPV 16, 18, 6 and 11. Cell Immunol. 2011;270:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ressing ME, Sette A, Brandt RM, et al. Human CTL epitopes encoded by human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 identified through in vivo and in vitro immunogenicity studies of HLA-A*0201-binding peptides. J Immunol. 1995;154:5934–5943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spee P, Neefjes J. TAP-translocated peptides specifically bind proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum, including gp96, protein disulfide isomerase and calreticulin. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2441–2449. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pike SE, Yao L, Setsuda J, et al. Calreticulin and calreticulin fragments are endothelial cell inhibitors that suppress tumor growth. Blood. 1999;94:2461–2468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.