Abstract

African Americans are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) relative to other racial groups. Although substance use has been linked to risky sexual behavior, our understanding of how these associations develop over the life course remains limited, particularly the role of social bonds. This study uses structural equation modeling to examine pathways from adolescent substance use to young adult sexual risk, substance problems, and social bonds and then to midlife risky sexual behavior among African American men and women, controlling for childhood confounders. Data come from four assessments, one per developmental period, of a community-based urban African American cohort (N=1242) followed prospectively from ages 6–42 years. We find that greater adolescent substance use predicts greater young adult substance problems and increased risky sexual behavior, both of which in turn predict greater midlife sexual risk. Although greater adolescent substance use predicts fewer young adult social bonds for both genders, less young adult social bonding is unexpectedly associated with decreased midlife risky sexual behavior among women, and not related for men. Substance use interventions among urban African American adolescents may have both immediate and long-term effects on decreasing sexual risk behaviors. Given the association between young adult social bonding and midlife risky sex among females, number of social bonds should not be used as a criterion for determining who to screen for sexual risk among African American women. Future studies should explore other aspects of social bonding in linking substance use and risky sexual behavior over time.

Keywords: Blacks, drug use, high risk sex, social integration, longitudinal research

African Americans are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs),1 with those in urban centers particularly at risk due to greater exposure to STIs.2 Alcohol and drugs may play a role in poor sexual outcomes, as substance involvement has been linked with risky sexual behaviors such as multiple sexual partnerships, unprotected sexual intercourse, exchanging sex for drugs or money, and selling sex.3,4 In adolescence, both alcohol and marijuana use are associated with sexual risk-taking.5,6 In adulthood, similar links have been found for alcohol and other substances including marijuana, cocaine, and heroin.7–10 Both substance use and abuse/dependence have been investigated in relation to sexual risk behaviors,5,11,12 suggesting that various levels of substance involvement may be important in this context.

Despite this evidence, few studies have examined the longitudinal relationships between substance use and risky sex. Much of the existing work has focused on direct associations between adolescent substance use and young adult risky sexual behaviors, such as inconsistent condom use and multiple sexual partnerships.13–16 However, certain types of substance involvement and risky sexual behaviors among African Americans may persist or become more pronounced throughout adulthood,17–20 underscoring the need to extend the investigations of direct and indirect effects later in the life course, and examine long-term associations.

In addition to direct associations, substance use may also be linked to risky sexual behavior indirectly through social bonding. The age-graded theory of informal social control21,22 suggests that adult conventional social bonds to others and community, such as those through marriage/partnership, parenthood, employment, religious participation, and organizational membership may exert informal social control over individuals’ behavior. These prosocial bonds also serve to integrate individuals into larger society, which may discourage deviance and promote normative behaviors.23,24 Thus, weak or absent social bonds may facilitate involvement in problem or risk behaviors. Through the process of cumulative disadvantage, which involves the perpetuation of inequalities over the life course,25,26 adolescent substance use may negatively affect adult social bonding.27,28 Specifically, disadvantage resulting from weak social bonds may promote substance involvement29,30 and risky sex,31,32 leading to a long-term trajectory of disadvantage. Moreover, the impact of early risk behaviors among African American youth, such as sexual risk or substance use, may be compounded over time if they prevent prosocial bonding.

The relationships between substance involvement and risky sexual behavior may differ by gender.12,16 Such differences could be partially attributed to disparate consequences of substance involvement on behavioral outcomes for men and women.33,34 They may also be related to traditional stereotypical gender roles,35,36 and gender-based differences in power and control dynamics in sexual relationships,37–39 which may become magnified with substance involvement.40,41 While Sampson and Laub’s social control theory22 does not specifically address gender differences, adolescent problem behavior may affect adult conventional bonds differently for men and women.42,43 Longitudinal investigations can shed more light on the direction and patterns of these differences in pathways between substance involvement and risky sexual behavior over the life course.

Accordingly, the goal of this study is to examine the pathways between adolescent substance use and midlife risky sexual behavior among urban African Americans. Specifically, we hypothesize that greater adolescent substance use is associated with greater young adult risky sexual behavior, greater young adult substance problems, and less young adult social bonding, all of which in turn predict increased midlife risky sexual behavior. We also seek to uncover any gender-specific associations and pathways.

Methods

Description of the Woodlawn Study

This is a secondary analysis of data from the Woodlawn Study, a prospective cohort study of urban African Americans. The study began in 1966 with an assessment of virtually all first-grade children (N=1242) from Woodlawn neighborhood in Chicago. During the initial assessment, mothers/mother surrogates provided information on the children and family environment. First-grade teachers rated the children on classroom adaptation and behavior. The cohort was subsequently reassessed in adolescence (1976/77, n=705, age 16–17 years), young adulthood (1992/93, n=952, age 32–33 years), and midlife (2002/03, n=833, age 42–43 years). The adolescent and adult surveys included questions on substance use and/or problems, health, and social relationships.

Attrition analyses on the Woodlawn Study data44,45 revealed no statistically significant differences between participants with and without either adult interview on gender, mother’s education, childhood behavior/adaptation, or adolescent alcohol and marijuana use. However, those with either adult interview were less likely to live in poverty in childhood or adolescence, and more likely to graduate from high school. Participants with and without an adolescent assessment did not differ significantly on gender, childhood poverty level, family income, or childhood behavior/adaptation. Further attrition analysis conducted for the current study revealed that participants with and without a midlife interview did not differ significantly on young adult risky sexual behavior. However, those missing a midlife interview were more likely to have an alcohol or drug disorder, and less likely to have at least one social bond in young adulthood. More detailed study description is presented elsewhere.46–48

Measures

The measures used in the current study include a mix of latent and observed variables.

Adolescent Substance Use

This is a latent variable comprised of three self-reported indicators: frequency of lifetime use of beer or wine, hard liquor or whiskey, and marijuana (0=never to 5=40 or more times). Other drugs are not included because of very low prevalence, which is consistent with the existing evidence on substance choices among African American adolescents.49

Young Adult Substance Problems

This is a latent variable that includes alcohol, illegal drugs, and non-medically used prescription drugs. It is comprised of four subscales: 1) extensive and/or prolonged use (e.g., used substance longer or in larger amounts than intended) (0=absent/low to 4=high; α=0.85), 2) physical and mental health effects (e.g., substance use caused psychological problems) (0=absent/low to 6=high; α=0.76), 3) social and functional effects (e.g., substance use interfered with school, work, or parenting) (0=absent/low to 5=high; α=0.77), and 4) signs of addiction (e.g., tolerance, withdrawal symptoms) (0=absent/low to 6=high; α=0.81), in line with operationalization by Fothergill and Ensminger.50 Lifetime abuse and dependence symptoms were assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (UM-CIDI) modules,51,52 and categorized using DSM III-R diagnostic criteria.53 Alcohol and drug problems are modeled together, as they are frequently interrelated,54,55 with substantial overlap in disorder diagnoses.56,57 Furthermore, the association between substance problems, such as dependence symptoms, and risky sexual behavior may not be substance specific.11

Midlife Substance Problems

This is a latent variable that includes alcohol, illegal drugs, and non-medically used prescription drugs. Midlife substance problems were assessed for the interval since young adulthood and categorized based on the DSM-IV58 diagnostic criteria, using the same categories and similar subscales as in young adulthood: 1) extensive and/or prolonged use (0=absent/low to 3=high, α=0.87), 2) physical and mental health effects (0=absent/low to 2=high, α=0.71), 3) social and functional effects (0=absent/low to 5=high, α=0.90), and 4) signs of addiction (0=absent/low to 5=high, α=0.91).

Adolescent Sexual Behavior

This is a latent variable with two indicators: lifetime frequency of engaging in sexual intercourse (0=never, 1=one to two times, 2=more often), and current use of birth control (“Do you use birth control?”) (0=always, 1=sometimes, 2=never), with higher score representing greater risk. Adolescents who were never using birth control and those who were engaging in sexual intercourse at the highest frequency represent the greatest risk. Adolescents who were not sexually active and who reported not using birth control were coded as always on current use of birth control to represent the lowest risk.

Young Adult and Midlife Risky Sexual Behavior

Both are observed variables, created by counting the number of individual sexual risk behaviors for each participant, including 1) two or more sexual partners in the last 30 days, 2) inconsistent or no condom use by participant or sexual partner(s) in the last 30 days), 3) obtaining drugs for sex, 4) giving drugs for sex, and 5) having sex for money (0=no risky sexual behaviors to 5=all risky sexual behaviors). We adopt this approach because examining individual risk behaviors separately may not adequately capture the overall sexual risk.59,60 In young adulthood drug/money and sex exchanges assess lifetime behaviors, while midlife measures assess the interval between young adult and midlife interviews.

Young Adult Social Bonds

This is an observed variable created by counting the number of social bonds for each participant, including whether or not the participant was currently 1) married or living with a partner, 2) employed, 3) had children in the household, 4) regularly attended religious services (at least once per week), and 5) belonged to at least one social nonreligious organization (0=all social bonds to 5=no social bonds). This approach allows for capturing the most protection against engaging in maladaptive/problem behaviors through accumulation of multiple agents of social control.23,24,30

Early Context/Childhood

Because early disadvantage and behavior/adaptation problems may partially account for subsequent substance and risky sexual behavior involvement, we include several potential early confounders. Family socioeconomic status (SES) is a latent variable with two indicators: mother’s education level (0–22 years), reverse-coded with higher scores indicating lower education level, and household income (0=$10,000 or more to 9=under $2000). Family mobility capturing the number of times a family moved (0–9), and household type (0=two-parent and 1=other) are observed variables. Mother’s mental health is a latent variable with two indicators: frequency of days feeling sad and blue, and days feeling nervous, tense, on edge (both 0=hardly ever to 3=very often).61 Classroom behavior is a latent variable with four indicators based on first grade teacher’s ratings:48 aggression, immaturity, and restlessness (0=adapting to 3=severely maladapting), and conduct (0=excellent to 3=unsatisfactory).

Analytic plan

First, we provide descriptive statistics for all indicator variables, including gender differences based on t-tests and chi-square tests. Next, using structural equation modeling (SEM) in IBM Amos 21, we analyze the measurement model through confirmatory factor analysis, evaluating factor loadings for statistical significance. Finally, we test the structural model, which specifies the hypothesized relationships among all variables, using full-information maximum likelihood estimation to address missingness, provide parameter estimates, and generate standard errors.62 Multigroup analysis is employed to test for gender differences, starting with the measurement model.63 We use the term ‘correlations’ to describe associations within each life stage, and ‘paths’ to describe directional prospective relationships. Because a statistical test for the significance of indirect effects is not available in the software used due to missing data, we focus on direct paths when considering the hypothesized pathways.

Three fit indices are used to determine how well the proposed model fits the data, including relative chi-square (χ2/df), comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Relative chi-square value of 5 or less, CFI of 0.90 or more, and RMSEA of 0.50 or less generally indicate adequate model fit.64,65

Results

As shown in Table 1, men and women differ significantly on classroom behavior, substance use, and risky sexual behavior variables with men having higher values. Women have significantly more social bonds than men. The results of multigroup analysis indicate the lack of measurement invariance (χ2=31.40, df=14, p<0.01), suggesting significant gender differences in the measurement models. Thus, we do not conduct multigroup analysis of the structural models, but present the measurement and structural models separately for men and women. Table 2 presents standardized factor loadings by gender. All factor loadings are statistically significant (p≤0.001) for both men and women, with magnitudes greater than 0.400 in the male model and 0.500 or above in the female model.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and gender differences for all indicator variables

| Men | Women | Gender difference† | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| M, SD | M, SD | ||

|

| |||

| Early Context and Adaptation (age 6–7 years) | |||

| Total family income in 1966/67 (0–9)a | 5.47, 2.64 | 5.16, 2.72 | 1.98* |

| Mother’s education (in years) (0–22)b | 9.46, 2.38 | 9.35, 2.34 | 0.86 |

| Household type (two-parent/other) (0–1) | 0.60, 0.49 | 0.56, 0.50 | 1.97 |

| Family mobility (times moved since participant’s birth) (0–9) | 2.38, 1.77 | 2.21, 1.76 | 1.69 |

| Mother feeling sad and blue (0–3) | 0.86, 0.90 | 0.85, 0.88 | 0.22 |

| Mother feeling nervous, tense, on edge (0–3) | 1.44, 1.00 | 1.41, 0.99 | 0.39 |

| First grade aggressiveness (0–3) | 0.70, 1.01 | 0.39, 0.79 | 5.81*** |

| Frist grade restlessness (0–3) | 0.73, 1.06 | 0.44, 0.88 | 5.22*** |

| First grade immaturity (0–3) | 0.74, 1.02 | 0.57, 0.93 | 3.07** |

| First grade conduct (0–3) | 1.54, 0.78 | 1.11, 0.76 | 8.95*** |

|

| |||

| Adolescence (age 16–17 years) | |||

|

| |||

| Lifetime frequency of beer or wine use (0–5) | 2.56, 1.78 | 1.83, 1.62 | 5.66*** |

| Lifetime frequency of hard liquor or whiskey use (0–5) | 1.20, 1.63 | 0.79, 1.27 | 3.71*** |

| Lifetime frequency of marijuana or hashish use (0–5) | 2.35, 2.04 | 1.40, 1.75 | 6.62*** |

| Lifetime frequency of engaging in sexual intercourse (0–2) | 1.65, 0.60 | 0.87, 0.86 | 149.93*** |

| Current frequency of birth control use (0–2)c | 1.61, 0.68 | 0.77, 0.92 | 150.84*** |

|

| |||

| Young Adulthood (age 32–33 years) | |||

|

| |||

| Alcohol and Drug Problems | |||

| Extensive and prolonged use (0–4) | 0.51, 1.09 | 0.28, 0.86 | 3.48** |

| Physical and mental health effects (0–6) | 0.61, 1.21 | 0.30, 0.88 | 4.53*** |

| Social and functional effects (0–5) | 0.52, 1.08 | 0.29, 0.85 | 3.72*** |

| Signs of addiction (0–6) | 0.90, 1.46 | 0.42, 1.10 | 5.77*** |

| Number of risky sexual behaviors (0–5) | 0.99, 0.90 | 0.69, 0.68 | 5.79*** |

| Number of social bonds (0–5)d | 2.92, 1.45 | 2.59, 1.24 | 3.72*** |

|

| |||

| Midlife (age 42–43 years) | |||

|

| |||

| Alcohol and Drug Problems | |||

| Extensive and prolonged use (0–3) | 0.51, 0.98 | 0.26, 0.76 | 4.00*** |

| Physical and mental health effects (0–2) | 0.41, 0.71 | 0.16, 0.48 | 35.15*** |

| Social and functional effects (0–5) | 0.91, 1.59 | 0.40, 1.15 | 5.08*** |

| Signs of addiction (0–5) | 0.72, 1.46 | 0.36, 1.15 | 3.75*** |

| Number of risky sexual behaviors (0–5) | 0.90, 0.76 | 0.64, 0.61 | 5.23*** |

based on chi-square tests for variables with ≤ 3 categories and t-tests for all others;

higher values represent lower family income;

higher values represent lower education;

higher values represent less frequent birth control use;

higher values represent fewer bonds

p<0.05

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Table 2.

Standardized factor loadings for indicators on latent variables in male and female measurement models

| Standardized factor loading | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Men (n=606) | Women (n=636) | |

| Early Context and Adaptation (age 6–7 years) | ||

|

| ||

| Low Family SES | ||

| Family income (1966/67) | 0.493 | 0.500 |

| Mother’s education (in years) | 0.530 | 0.524 |

| Mother’s Mental Health | ||

| Feeling sad and blue | 0.822+ | 0.932+ |

| Feeling nervous, tense, on edge | 0.488 | 0.502 |

| Poor Classroom Behavior | ||

| Aggressiveness | 0.786 | 0.718 |

| Immaturity | 0.708 | 0.635 |

| Restlessness | 0.911 | 0.933 |

| Conduct | 0.550 | 0.541 |

|

| ||

| Adolescence (age 16–17 years) | ||

|

| ||

| Substance Use | ||

| Lifetime frequency use of beer or wine | 0.827 | 0.870 |

| Lifetime frequency use of hard liquor or whisky | 0.722 | 0.755 |

| Lifetime frequency use of marijuana | 0.742 | 0.705 |

|

| ||

| Sexual Behavior | ||

| Lifetime frequency of engaging in sexual intercourse | 0.973 | 1.070 |

| Current use of birth control | 0.544 | 0.516 |

|

| ||

| Young Adulthood (age 32–33 years) | ||

|

| ||

| Alcohol and Drug Problems | ||

| Extensive and prolonged use | 0.863 | 0.909 |

| Physical and mental health effects | 0.855 | 0.851 |

| Social and functional effects | 0.882 | 0.866 |

| Signs of addiction | 0.894 | 0.888 |

|

| ||

| Midlife (age 42–43 years) | ||

|

| ||

| Alcohol and Drug Problems | ||

| Extensive and prolonged use | 0.960 | 0.969 |

| Physical and mental health effects | 0.888 | 0.881 |

| Social and functional effects | 0.915 | 0.948 |

| Signs of addiction | 0.945 | 0.931 |

p=0.001; all others p<0.001

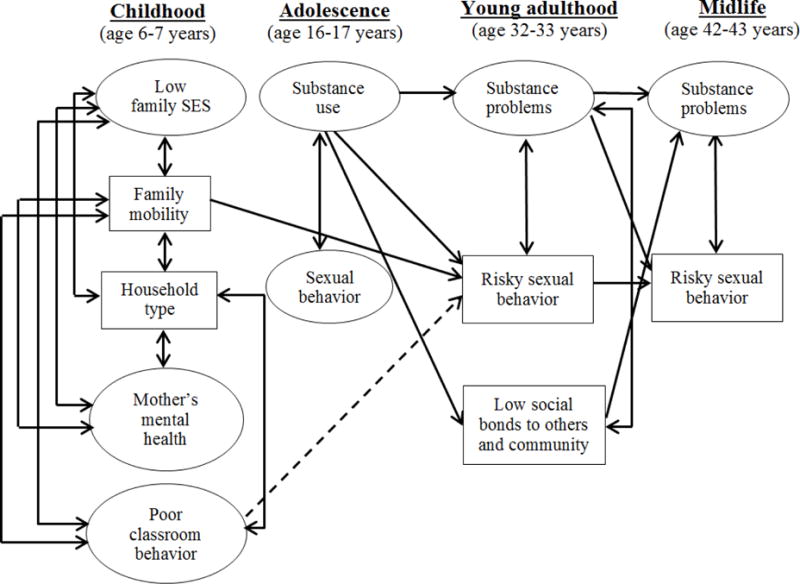

Male model

Statistically significant (p<0.05) paths and correlations in the male model are depicted in Figure 1. Table 3 presents unstandardized coefficients, standard errors, and standardized (β) coefficients for selected direct paths. Table 4 shows correlations within each life stage. The model demonstrates an adequate fit to the data (χ2/df=1.65, CFI=0.97, RMSEA=0.03).

Figure 1.

Male structural model depicting significant (p<.05) paths and correlations

Solid lines represent positive paths and correlations. Dashed lines represent negative paths.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates for paths in male and female structural models including unstandardized coefficients (b) with standard errors and standardized coefficients (β)

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | |

| Early Context and Adaptation Variables (age 6–7 years) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Family mobility → Adolescent substance use | 0.049 (0.041) | 0.075 | −0.077 (0.034)* | −0.141 |

| Family mobility → Young adult risky sexual behavior | 0.072 (0.025)** | 0.141 | −0.005 (0.019) | −0.013 |

| Poor classroom behavior → Young adult risky sexual behavior | −0.283 (0.109)* | −0.136 | 0.233 (0.083)** | 0.141 |

|

| ||||

| Adolescent Variables (age 16–17 years) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Adolescent substance use → Young adult substance problems | 0.203 (0.056)*** | 0.245 | 0.125 (0.049)* | 0.162 |

| Adolescent substance use → Young adult risky sexual behavior | 0.164 (0.058)** | 0.209 | 0.106 (0.048)* | 0.149 |

| Adolescent substance use → Low young adult social bonds | 0.270 (0.081)*** | 0.214 | 0.200 (0.081)* | 0.156 |

| Adolescent sexual behavior → Young adult risky sexual behavior | 0.080 (0.161) | 0.034 | 0.040 (0.080) | 0.027 |

|

| ||||

| Young Adult Variables (age 32–33 years) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Young adult substance problems → Midlife substance problems | 0.558 (0.087)*** | 0.362 | 0.509 (0.075)*** | 0.343 |

| Young adult substance problems → Midlife risky sexual behavior | 0.159 (0.049)** | 0.201 | 0.118 (0.044)** | 0.144 |

| Young adult risky sexual behavior → Midlife risky sexual behavior | 0.144 (0.048)** | 0.172 | 0.187 (0.044)*** | 0.209 |

| Young adult social bonds → Midlife substance problems | 0.184 (0.055)*** | 0.181 | 0.121 (0.043)** | 0.136 |

| Young adult social bonds → Midlife risky sexual behavior | −0.023 (0.029) | −0.044 | −0.049 (0.024)* | −0.099 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Table 4.

Correlations for variables within each life stage in male and female structural models

| Male correlation | Female correlation | |

|---|---|---|

| Early Context and Adaptation (age 6–7 years) | ||

|

| ||

| Low family SES ↔ Family mobility | 0.277*** | 0.309*** |

| Low family SES ↔ Household type | 0.585*** | 0.553*** |

| Low family SES ↔ Mother’s mental health | 0.222** | 0.172** |

| Low family SES ↔ Poor classroom behavior | 0.106* | 0.152** |

| Family mobility ↔ Household type | 0.243*** | 0.199*** |

| Family mobility ↔ Mother’s mental health | 0.140* | 0.217*** |

| Family mobility ↔ Poor classroom behavior | 0.153*** | 0.123** |

| Household type ↔ Mother’s mental health | 0.170** | 0.098 |

| Household type ↔ Poor classroom behavior | 0.152*** | 0.107* |

| Mother’s mental health ↔ Poor classroom behavior | −0.019 | 0.106 |

|

| ||

| Adolescence (age 16–17 years) | ||

|

| ||

| Adolescent substance use ↔ Adolescent sexual behavior | 0.451*** | 0.379*** |

|

| ||

| Young Adulthood (age 32–33 years) | ||

|

| ||

| Young adult substance problems ↔ Young adult risky sexual behavior | 0.321*** | 0.311*** |

| Young adult substance problems ↔ Low young adult social bonds | 0.206*** | 0.184*** |

| Young risky sexual behavior ↔ Low young adult social bonds | −0.009 | 0.006 |

|

| ||

| Midlife (age 42–43 years) | ||

|

| ||

| Midlife substance problems ↔ Midlife risky sexual behavior | 0.264*** | 0.296*** |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Among men, greater adolescent substance use predicts increased young adult risky sexual behavior (β=0.209, p=0.005) (Figure 1, Table 3). Young adult risky sexual behavior is in turn a positive predictor of midlife risky sexual behavior (β=0.172, p=0.003). Greater adolescent substance use also predicts greater young adult substance problems (β=0.245, p<0.001), which are in turn associated with greater midlife risky sexual behavior (β=0.201, p=0.001). In the male model, greater adolescent substance use predicts fewer young adult social bonds (β=0.214, p<0.001). However, low young adult social bonding is not significantly associated with midlife risky sexual behavior. Among childhood variables, there is a positive association for family mobility and negative association for poor classroom behavior with young adult risky sexual behavior (β=0.141, p=0.004 and β=−0.136, p=0.01, respectively.). Additionally, greater young adult substance problems and lower young adult social bonding are both associated with greater midlife substance problems (β=0.362, p<0.001 and β=0.181, p<0.001, respectively).

Other findings include positive correlations between substance involvement and sexual/risky sexual behavior in adolescence (r=0.451, p<0.001), young adulthood (r=0.321, p<0.001), and midlife (r=0.264, p<0.001) (Figure 1, Table 4). All early context and adaptation variables with the exception of mother’s mental health and poor classroom behavior are also significantly (p’s<0.05) interrelated. In young adulthood, low social bonding is not significantly associated with risky sexual behavior.

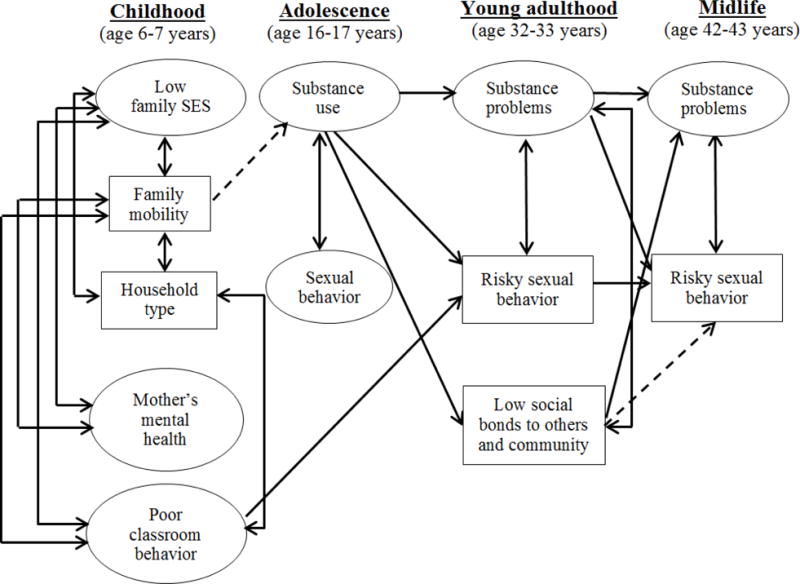

Female model

Significant paths and correlations in the female model are depicted in Figure 2 and presented in detail in Table 3 and Table 4. The female model provides an adequate fit to the data (χ2/df=1.76, CFI=0.97, RMSEA=0.04).

Figure 2.

Female structural model depicting significant (p<0.05) paths and correlations

Solid lines represent positive paths and correlations. Dashed lines represent negative paths.

As shown in Figure 2 and Table 3, among women, greater adolescent substance use is associated with more risky sexual behavior in young adulthood (β=0.149, p=0.028), which in turn predicts greater midlife risky sexual behavior (β=0.209, p<0.001). Greater adolescent substance use is also associated with greater young adult substance problems (β=0.162, p=0.012), which predict increased involvement in midlife risky sexual behavior (β=0.144, p=0.008). In the female model, greater adolescent substance use is associated with fewer young adult social bonds (β=0.156, p=0.013). Less social bonding is in turn associated with less midlife risky sexual behavior (β=−0.099, p=0.042). Additionally, while greater early family mobility predicts less adolescent substance use (β=−0.141, p=0.023), poorer classroom behavior is associated with greater young adult risky sexual behavior (β=0.141, p=0.005). Greater substance problems and fewer social bonds in young adulthood predict greater midlife substance problems (β=0.343, p<0.001 and β=0.136, p=0.004, respectively).

Further findings for women (Figure 2, Table 4) include positive correlations between substance involvement and sexual/risky sexual behavior in adolescence (r=0.379, p<0.001), young adulthood (r=0.311, p<0.001), and midlife (r=0.296, p<0.001). With the exception of household type and mother’s mental health, and mother’s mental health and poor classroom behavior, the early context and behavior variables are interrelated (p’s<0.05). Low social bonding and risky sexual behavior are not significantly associated in young adulthood.

Discussion

Examining the pathways between substance involvement and risky sexual behavior, we found that greater adolescent substance use was associated with greater young adult sexual risk and greater young adult substance problems, which in turn were associated with midlife risky sexual behavior for both men and women. Thus, substance using African American adolescents may be more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior and develop substance problems in young adulthood, both of which may in turn increase midlife risky sexual behavior. Consistent with the study hypotheses, results suggest that the relationships between substance use and risky sexual behavior operate over time, across the life course, and thus beyond any short-term effects of substances on sexual behavior. Our findings extend to midlife the previous work on substance involvement–risky sexual behavior associations from adolescence to young adulthood,13,15,16 and attest to the lasting nature of these relationships. These pathways are also consistent with the trends describing progression in substance involvement,66,67 and continuity in adult risky sexual behavior.68,69

Congruous with the process of cumulative disadvantage,25,26 in this urban African American cohort, adolescent boys and girls engaging in greater substance use had fewer young adult social bonds. These results suggest that adolescent substance involvement may interfere with successful transition into adulthood, and formation of age-appropriate social bonds. Young teens who use substances frequently may be negatively labeled early on,70,71 potentially resulting in stigma and marginalization, which may restrict future conventional opportunities.26,72 Previous research suggests that heavy drinking in particular among African Americans compared to whites is perceived by youth to be met with greater parental disapproval and to be associated with greater health problems.73 Long-term adverse consequences of substance use may be particularly salient among urban African American adolescents whose life chances are already constrained by higher-than-average concentration of economic disadvantage, fewer social resources and opportunities, and fragmented social networks.26,67 In this context, individual behaviors may interact with social and economic environment in a mutually reinforcing way to magnify the negative consequences of adolescent substance use on adult outcomes.67 Consequently, substance-using adolescents may find it difficult or even impossible to successfully transition into adult roles and establish social bonds to others and to community. On the other hand, risky sex may be seen as more normative (and met with less disapproval) in some communities. Therefore, it may not impact social bond formation in adulthood, nor be affected by social control to the same extent as substance use. This is an important topic for future research.

The path from young adult social bonding to midlife risky sexual behavior was statistically significant only among women, in the direction opposite to what was hypothesized: fewer bonds were associated with less risky sex. While this finding may be spurious, an alternative explanation lies in the inherently social nature of high-risk sex, which requires the involvement of other individuals. Thus, a greater number of young adult social bonds may afford more opportunities to meet sexual partners, increasing sexual involvement and facilitating high-risk sex over time. High levels of incarceration and mortality among African American men are thought to contribute to gender imbalance in African American communities creating a large female to male ratio.74,75 Perhaps given these unique community dynamics, social bonding may be more important in creating sexual opportunities for women, while for men such opportunities may be abundant regardless of social bonds.

It is also possible that in some cases, the accumulation of social bonds may become a source of strain,76,77 particularly when these bonds are perceived as challenging.78 For example, employment opportunities for residents of economically disadvantaged urban areas typically offer low wages, limited stability, and little occupational advancement.79–81 They may also be a source of negative experiences such as racism and discrimination.82 Marriages and partnerships may be less stable and cohesive,83–85 and parenting more challenging and stressful80,86 with socioeconomic pressures and strain related to life in urban areas with high crime rates and relatively few resources and supports. Future research should investigate if among urban African American women who face numerous adversities and disadvantages, social bonding facilitates involvement in risky sex as a way of coping with excessive stress,87 instead of reducing such behaviors through informal social control.

Previous studies have identified some differences in substance involvement and sexual risk-taking for men and women;12,16 however, our study found few distinctions. While previous investigations considered individual high-risk sexual behaviors separately, the current study investigated an aggregate measure based on the number of sexual risk behaviors, in relation to latent constructs combining multiple substances and focusing on abuse and dependence symptoms in adulthood. Our findings suggest that when more comprehensive measures are used, the interrelationships between substance involvement and risky sexual behavior exist for both men and women.

Several gender differences were noted in the paths between childhood measures and later outcomes. Specifically, poor classroom behavior and young adult risky sex were positively associated among women but inversely associated for men, after controlling for other childhood variables, as well as adolescent substance use and sexual behavior. Further, childhood family mobility appeared to be protective against adolescent substance use for women, while it was not statistically significant for men. Instead, men with greater childhood family mobility had greater young adult sexual risk, while this direct effect was not observed for women. These findings highlight the importance of early context and its likely influence on behavior across the life course.

The current study has important strengths. Data come from a relatively large, neighborhood-based urban cohort of African Americans followed prospectively for approximately 35 years. The length of the study with multiple waves of data collection allowed for examining the pathways between substance involvement and risky sexual behavior across a substantial portion of the life course. Using multiple indicators of substance involvement and risky sexual behavior over time allowed for a more realistic modeling approach for both substance involvement54,88 and sex-related risk.59,60

Despite the aforementioned strengths, our study has several limitations which should be considered when interpreting the results. Although helpful in focusing on a population segment heavily affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, using a neighborhood-based cohort of urban African Americans may limit generalizability of the findings. Experiences and behaviors of any cohort of participants followed over an extended period of time are, to some extent, influenced by the social and historical circumstances experienced during maturation and aging. Although highly probable, we cannot know with certainty whether African Americans in urban areas other than Chicago have had similar experiences. Additionally, the Woodlawn Study began in 1967 with the most recent assessment having occurred in 2002. The time lag from when the data is collected and analyzed is a common pitfall for prospective studies of long duration, but also the only way to study the development of behaviors over the life course. This also means, however, that while some of the collected measures may have been optimally appropriate at the time of data collection, their generalizability to the current time period may be somewhat limited. Further, attrition is a concern in neighborhood cohort studies. Because participants without an adult interview were more likely to live in poverty in childhood and adolescence and less likely to graduate from high school, the results may be more generalizable to those who were growing up less poor and to high school graduates.

In terms of measures, substance involvement and sexual behavior variables were collected using self-reports, which may be subject to bias. Despite striving to achieve temporal ordering for all focal variables, young adult substance problems and drug/money sex exchanges were assessed as lifetime measures, resulting in some overlap. Both problems, however, were very rare in adolescence. Additionally, the two variables used to characterize adolescent sexual behavior were frequency of sexual intercourse and use of birth control. Sexual activity alone may not necessarily constitute risk, but instead a developmentally appropriate experimentation.89 This is especially salient given that the highest measured frequency of engaging in sexual intercourse was three or more times, and the context in which this behavior occurred is unknown (e.g., number of partners). However, this item is useful in capturing adolescents who were already sexually active at age 16. Extant literature suggest that historically a male condom has been one of the most common forms of contraception among African American adolescents.90–92 Thus, even though the frequency of birth control use measure did not capture condom use specifically, it can be assumed that a condom was used by the teens as a form of birth control at least some of the time. To mitigate the individual limitations of these two measures, we considered them together as a latent variable whose greater values are likely be a stronger indicator of risk than either variable considered separately. However, we note the lack of association of the sexual risk construct with behaviors in young adulthood is likely the result of the limitations of these measures. Another limitation worth mentioning is our use of ordinal-level variables and several two-item latent constructs in the structural equation models, which is not ideal, and may underestimate associations. Although we were able to examine the effect of accumulation of conventional young adult social bonds to others and community relative to midlife risky sexual behavior, the social bonding measure did not capture bond strength and quality, transitions in bonding over time, or other dimensions of community bonding that may be relevant for urban African Americans.

Regardless of these caveats, our study has potential implications for public health interventions and offers directions for future research. The findings suggest that efforts to reduce adolescent substance use may have both direct and indirect effects on decreasing risky sexual behavior as far as midlife, by reducing young adult substance problems and young adult risky sexual behavior among urban African American men and women. Thus, substance use intervention programs may want to monitor risky sexual behavior as a short and long-term outcome. Moreover, substance abuse treatment programs should either continue to offer or, if not yet available, prioritize screening for and reducing risky sexual behavior among younger adults as well as those entering midlife. Given the positive link between young adult social bonding and midlife risky sex among females and the lack of association for men, as well as the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS and other STIs in African American communities,93,94 assessment for sexual risk behaviors should not be based on the number of social bonds.

Considering our unexpected findings on young adult social bonding, future studies should explore the potential importance of individual social bonds, various bond combinations, bond strength and quality, and changes in bonding over time in pathways between substance use and risky sexual behavior. Further investigations should explore additional pathways, including incarceration and other types of criminal justice system involvement. Despite the temporally ordered, significant paths for substance involvement and risky sexual behavior, our ability to make definitive causal statements is hindered by possible issues of spuriousness. Therefore, future examinations of the link between substance involvement and sexual risk over time should employ designs and methods optimally suited to examining causality, such as propensity score matching.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by NIDA Grants R01DA026863 and R01DA033999, and by the University of Maryland Ann G. Wylie Dissertation Fellowship. We are grateful to the Woodlawn cohort participants and the Advisory Board for their collaboration over many years. We would like to thank Margaret Ensminger and Sheppard Kellam for their involvement in the Woodlawn Study. Special thanks to Elaine Doherty for her helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report. 2015;27 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published November 2016 Accessed May 9, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman LM, Berman SM. Epidemiology of STI disparities in African American communities. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:S4–S12. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818eb90e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celentano DD, Latimore AD, Mehta SH. Variations in sexual risks in drug users: emerging themes in a behavioral context. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5:212–218. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0030-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logan TK, Cole J, Leukefeld C. Women, sex, and HIV: social and contextual factors, meta-analysis of published interventions, and implications for practice and research. Psychol Bull. 2002;128:851–885. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan SC, Strycker LA, Duncan TE. Exploring associations in developmental trends of adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior in a high-risk population. J Behav Med. 1999;22:21–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1018795417956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitaker DJ, Miller KS, Clark LF. Reconceptualizing adolescent behavior: beyond did they or didn’t they? Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32:111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braithwaite R, Stephens T. Use of protective barriers and unprotected sex among adult male prison inmates prior to incarceration. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:224–226. doi: 10.1258/0956462053420112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez J, Comerford M, Chitwood DD, Fernandez MI, McCoy CB. High risk sexual behaviours among heroin sniffers who have no history of injection drug use: implications for HIV risk reduction. AIDS Care. 2002;14:391–398. doi: 10.1080/09540120220123793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seth P, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Robinson LS. Alcohol use as a marker for risky sexual behaviors and biologically confirmed sexually transmitted infections among young adult African-American women. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Word CO, Bowser B. Background to crack cocaine addiction and HIV high-risk behavior: The next epidemic. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1997;23:67–77. doi: 10.3109/00952999709001688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackesy-Amiti ME, Frendrich M, Johnson TP. Symptoms of substance dependence and risky sexual behavior in a probability sample of HIV-negative men who have sex with men in Chicago. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapert SF, Aarons GA, Sedlar GR, Brown SA. Adolescent substance use and sexual risk-taking behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger AT, Khan MR, Hemberg JL. Race differences in longitudinal associations between personal and peer marijuana use and adulthood sexually transmitted infection risk. J Addict Dis. 2012;31:130–142. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2012.665691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo J, Chung I, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Developmental relationships between adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:354–362. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan MR, Berger AT, Wells BE, Cleland CM. Longitudinal associations between adolescent alcohol use and adulthood sexual risk behavior and sexually transmitted infections in the United States: assessment of differences by race. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:867–876. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staton M, Leukefeld C, Logan TK, et al. Risky sex behavior and substance use among young adults. Health Soc Work. 1999;24:147–153. doi: 10.1093/hsw/24.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corneille MA, Zyzniewski LE, Belgrave FZ. Age and HIV risk and protective behaviors among African American women. J Black Psychol. 2008;34:217–233. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kandel D, Chen K, Warner LA, Kessler RC, Grant B. Prevalence and demographic correlates of symptoms of last year dependence on alcohol, nicotine, marijuana and cocaine in the U.S. population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:11–29. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma G, Shive S. A comparative analysis of perceived risks and substance abuse among ethnic groups. Addict Behav. 2000;25:361–371. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myers HF, Javanbakht M, Martinez M, Obediah S. Psychosocial predictors of risky sexual behaviors in African American men: implications for prevention. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(Suppl. A):66–79. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.5.66.23615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Crime and deviance over the life course: the salience of adult social bonds. Am Sociol Rev. 1990;55:609–627. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points through Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durkheim E. In: Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Spaulding JA, Simpson G, translators. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1951. Original work published 1898. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umberson D. Family status and health behaviors: social control as a dimension of social integration. J Health Soc Behav. 1987;28:306–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dannefer D. Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J Gerontol B Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58B:S327–S337. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.s327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. A life-course theory of cumulative disadvantage and the stability of delinquency. In: Thornberry T, editor. Developmental Theories of Crime and Delinquency. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1997. pp. 133–162. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fothergill KE, Ensminger ME, Green KM, Robertson JA, Juon HS. Pathways to adult marijuana and cocaine use: a prospective study of African Americans from age 6 to 42. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50:65–81. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newcomb MD. Psychosocial predictors and consequences and of drug use: A developmental perspective within a prospective study. J Addict Dis. 1997;16:51–89. doi: 10.1300/J069v16n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brook JS, Richter L, Whiteman M, Cohen P. Consequences of adolescent marijuana use: incompatibility with the assumption of adult roles. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr. 1999;125:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green KM, Doherty EE, Reisinger HS, Chilcoat HD, Ensminger ME. Social integration in young adulthood and the subsequent onset of substance use and disorders among a community population of urban African Americans. Addiction. 2010;105:484–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02787.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharp SF. Relationships with children and AIDS-risk behaviors among female IDUs. Deviant Behav. 1998;19:3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wayment HA, Wyatt GE, Tucker, et al. Predictors of risky and precautionary sexual behaviors among single and married white women. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2003;33:791–816. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason WA, Hitch JE, Kosterman R, McCarty CA, Herrenkohl TI, Hawkins JD. Growth in adolescent delinquency and alcohol use in relation to young adult crime, alcohol use disorders, and risky sex: a comparison of youth from low-versus middle-income backgrounds. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:1377–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aronson RE, Whitehead TL, Baber WL. Challenges to masculine transformation among urban low-income African American males. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:732–741. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prentice DA, Carranza E. What women and men should be, shouldn’t be, are allowed to be, and don’t have to be: the contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychol Women Q. 2002;26:269–281. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amaro H, Raj A. On the margin: power and women’s HIV risk reduction strategies. Sex Roles. 2000;42:723–749. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rickert VI, Sanghvi R, Wiemann CM. Is lack of sexual assertiveness among adolescent and young adult women a cause for concern? Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34:178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Senn TE, Coury-Doninger P, Urban MA. Alcohol consumption, drug use, and condom use among STD clinic patients. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:762–770. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharpe TT. Sex-for-crack-cocaine exchange, poor Black women, and pregnancy. Qual Health Res. 2001;11:612–630. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blair SL. The influence of risk-taking behaviors on the transition into marriage: an examination of the long-term consequences of adolescent behavior. Marriage Fam Rev. 2010;46:126–146. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brady KT, Randall CL. Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1999;22:241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doherty EE, Green KM, Ensminger ME. Investigating the long-term influence of adolescent delinquency on drug use initiation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ensminger ME, Juon HS, Lee R, Lo S. Social connections in the inner city: examination across the life course. Longit Life Course Stud. 2009;1:11–26. doi: 10.14301/llcs.v1i1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crum RM, Juon HS, Green KM, Robertson J, Fothergill K, Ensminger M. Educational achievement and early school behavior as predictors of alcohol-use disorders: 35-year follow-up of the Woodlawn Study. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:75–85. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ensminger ME, Juon HS, Fothergill KE. Childhood and adolescent antecedents of substance use in adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:833–844. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kellam SG, Branch JD, Agrawal KC, Ensminger ME. Mental Health and Going to School: The Woodlawn Program of Assessment, Early Intervention and Evaluation. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2012: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fothergill KE, Ensminger ME. Childhood and adolescent antecedents of drug and alcohol problems: a longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Intl J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Third. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dick DM, Agrawal A. The genetics of alcohol and other drug dependence. Alcohol Res Health. 2008;31(2):111–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lejuez CW, Zvolensky MJ, Daughters SB, et al. Anxiety sensitivity: a unique predictor of dropout among inner-city heroin and crack/cocaine users in residential substance use treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:811–818. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reiter PL. Measuring cervical cancer risk: development and validation of the CARE Risky Sexual Behavior Index. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1865–1871. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9380-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Susser E, Desvarieux M, Wittkowksi KM. Reporting sexual risk behavior for HIV: a practical risk index and a method for improving risk indices. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:671–674. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.4.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brown H, Adams RG, Kellam SG. A longitudinal study of teenage motherhood and symptoms of distress: the Woodlawn community epidemiological project. Res Commun Mental Health. 1981;2:183–213. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Graham JW. Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Byrne BM. Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS graphics: a road less traveled. Struct Equ Modeling. 2004;11:272–300. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Model. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garson GD. Structural Equation Modeling. Raleigh, NC: Statistical Associates Publishing, North Carolina State University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectory: early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16:193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gil AG, Wagner EF, Tubman JG. Associations between early-adolescent substance use and subsequent young-adult substance use disorders and psychiatric disorders among a multiethnic male sample in South Florida. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1603–1609. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Moilanen KL, Crockett LJ, Raffaelli M, Jones BL. Trajectories of sexual risk from middle adolescence to early adulthood. J Res Adolesc. 2010;20:114–139. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scott ME, Wildsmith E, Welti K, Ryan S, Schelar E, Steward-Streng NR. Risky adolescent sexual behaviors and reproductive health in young adulthood. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43:110–118. doi: 10.1363/4311011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Downs WR, Flanagan JC, Robertson JF. Labeling and rejection of adolescent heavy drinkers: Implications for treatment. J Appl Soc Sci. 1985;10:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Downs WR, Robertson JF, Harrison LR. Control theory, labeling theory, and the delivery of services for drug abuse to adolescents. Adolescence. 1997;32:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paternoster R, Iovanni L. The labeling perspective and delinquency: an elaboration of the theory and an assessment of the evidence. Justice Q. 1989;6:359–394. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ringwalt CL, Palmer JH. Differences between white and black youth who drink heavily. Addictive Behaviors. 1990:455–460. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90032-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Fullilove RE, Aral SO. Social context of sexual relationships among rural African Americans. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:69–76. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.El-Bassel N, Caldeira NA, Ruglass LM, Gilbert L. Addressing the unique needs of African American women in HIV prevention. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:996–1001. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Agnew R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminol. 1992;30:47–87. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nielsen AL. Testing Sampson and Laub’s life course theory: ge, race/ethnicity, and drunkenness. Deviant Behav. 1999;20:129–151. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jager J. A developmental shift in Black-White differences in depressive affect across adolescence and early adulthood: the influence of early adult social roles and socio-economic status. Int J Behav Dev. 2011;35:457–469. doi: 10.1177/0165025411417504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anderson SG, Halter AP, Gryzlak BM. Difficulties after leaving TANF: inner-city women talk about reasons for returning to welfare. Social Work. 2004;49:185–194. doi: 10.1093/sw/49.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: psychological distress, parenting, and socioeconomic development. Child Dev. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wilson WJ. Studying inner-city social dislocations: the challenges of public agenda research: 1990 Presidential address. Am Sociol Rev. 1991;56:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fernandes L, Alsaeed NHQ. African Americans and workplace discrimination. Eur J Engl Stud. 2014;2:56–76. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fein DJ. Married and Poor: Basic Characteristics of Economically Disadvantaged Married Couples in the US. New York, NY: MDRC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lichter DT, Qian Z, Mellott LM. Marriage or dissolution? Union transitions among poor cohabiting women. Demography. 2006;43:223–240. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McLoyd VC, Cauce AM, Takeuchi D, Wilson L. Marital processes and parental socialization in families of color: a decade review of research. J Marriage Fam. 2000;62:1070–1093. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pinderhughes EE, Nix R, Foster EM, Jones D. The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Parenting in context: impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks, and dangers on parental behaviors. J Marriage Fam. 2007;63:941–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Folkman S, Chesney MA, Pollack L, Phillips C. Stress, coping, and high-risk sexual behavior. Health Psychol. 1992;11:218–222. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.4.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Martinotti G, Carli V, Tedeschi D, et al. Mono- and polysubstance dependent subjects differ on social factors, childhood trauma, personality, suicidal behaviour, and comorbid Axis I diagnoses. Addict Behav. 2009;34:790–793. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Halpern CT. Reframing research on adolescent sexuality: Healthy sexual development as part of the life course. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;42(1):6–7. doi: 10.1363/4200610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brown JL, Hennessy M, Sales JM, DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Stanton B. Multiple method contraception use among African American adolescents in four US cities. Infect Dis Obstet and Gynecol. 2011;(2):1–7. doi: 10.1155/2011/765917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Clark SD, Zabin LS, Hardy JB. Sex, contraception, and parenthood: Experience and attitudes among urban black young men. Fam Plann Perspect. 1984;16:77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Finkel ML, Finkel DJ. Sexual and contraceptive knowledge, attitudes and behavior of male adolescents. Fam Plann Perspect. 1975;7:256–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. African Americans and sexually transmitted diseases. 2012 http://ethspesilkaitis.weebly.com/uploads/1/3/6/7/13672065/aas-and-std-fact-sheet.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2015.

- 94.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among African Americans. 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/HIV-AA-english-508.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2015.