Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify predictors of sexual behavior and condom use in African American adolescents, as well as to evaluate the effectiveness of comprehensive sexuality and abstinence-only education to reduce adolescent sexual behavior and increase condom use. Participants included 450 adolescents aged 12 to 14 years in the southern United States. Regression analyses showed favorable attitudes toward sexual behavior and social norms significantly predicted recent sexual behavior, and favorable attitudes toward condoms significantly predicted condom usage. Self-efficacy was not found to be predictive of adolescents’ sexual behavior or condom use. There were no significant differences in recent sexual behavior based on type of sexuality education. Adolescents who received abstinence-only education had reduced favorable attitudes toward condom use, and were more likely to have unprotected sex than the comparison group. Findings suggest that adolescents who receive abstinence-only education are at greater risk of engaging in unprotected sex.

Despite sexuality education initiatives, rates of sexual activity have remained steady among teenagers in the past decade (Centers for Disease Control, CDC 2014). Among American high school students, nearly half reported lifetime sexual intercourse, and less than two-thirds of sexually-active adolescents reported condom use during their last intercourse (CDC, 2014). Less is known about the prevalence of sexual behaviors among middle school students; however, 5.6% of high school students reported intercourse before age 13 (CDC, 2014). A study of middle school students revealed 5–20% of sixth graders and 14–42% of eighth graders reported lifetime intercourse (Moore, Barr, & Johnson, 2013). Compared to other racial/ethnic groups, African American (AA) middle school students reported higher levels of lifetime intercourse, sexual activity before age 11, and having more than three sexual partners (Moore et al., 2013).

Theoretical framework

The theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1985) can be used as a model to explain adolescent sexual behavior. According to this theory, an individual’s attitude toward a behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control together shape behavioral intentions and behavior (Ajzen, 1985). Attitudes refer to personal evaluation of how favorable or unfavorable a behavior is. Subjective norms include perceptions of how significant others judge behaviors as well as perceptions of whether significant others believe that behaviors should or should not be performed (Ajzen, 1985). Significant others may refer to many individuals in an adolescent’s life; however, this study will focus on adolescents’ peers. Perceived behavioral control is the perception of ease or difficulty performing behaviors (Ajzen, 1985), which is closely related to the concept of self-efficacy, or the perception of one’s ability to complete tasks and reach goals (Bandura, 1977). This study examined adolescent sexual behavior utilizing components of the theory of planned behavior, specifically attitudes towards sex and condoms, subjective norms (peer norms) and perceived behavioral control (self-efficacy).

Review of Literature

Attitudes

Adolescents often view sexual abstinence as a normative stage of sexual development in which one is initially abstinent until transitioning into sexual activity (Masters, Beadnell, Morrison, Hoppe & Gilmore, 2008; Ott, Pfeiffer, & Fortenberry, 2006). Most adolescents correctly identify abstinence as the most effective way to prevent STIs and unintended pregnancy (Akers, Gold, Coyne-Beasley & Corbie-Smith, 2012); however, actual practice of abstinence often declines with age (Santelli, Lindberg, Finer & Singh, 2007). Sexual initiation is also considered developmentally appropriate and prolonged abstinence as unrealistic (Akers et al., 2012). Consequently, many adolescents hold all-or-nothing attitudes in that once virginity is lost, they cannot revert back to abstinence (Ott et al., 2006). In a sample of eighth grade students, 18% thought abstinence was unacceptable within relationships and 39% were unsure of its acceptability (Royer, Keller & Heidrich, 2009). Some drawbacks of abstinence according to adolescents included ridicule or teasing from peers, dating partner pressure, and sexual tension (Abbott & Dalla, 2008).

Studies have shown that sexually abstinent youth tend to have more positive attitudes about abstinence than sexually active youth (Akers et al., 2011; Anderson et al., 2011; Childs, Moneyham & Felton, 2008; Hopkins, Tanner & Raymond, 2004). Adolescents with positive abstinence attitudes were less likely to initiate or anticipate having sex within the next year compared to peers with less favorable attitudes toward abstinence, whereas having positive sex attitudes increased the likelihood of sexual activity within the next six months (Anderson et al., 2011; Masters et al., 2008). While attitudes are strong predictors of sexual behavior, they are subject to change as adolescents age with attitudes toward sex tend to become more permissive with time (Akers et al., 2011).

Condoms are almost universally identified by adolescents as effective in preventing STIs and unwanted pregnancy (Akers et al., 2012). Adolescents’ condom attitudes are associated with condom use intention, and those who viewed condoms favorably were more likely to report future condom use intentions (Alvarez, Villarruel, Zhou & Gallegoss, 2010; Hogben et al., 2006; Lee, Lewis & Kirk, 2011; Potard, Courtois & Rusch, 2008; Small, Weinman, Buzi, & Smith, 2009). Positive attitudes and condom use intention are associated with greater likelihood of consistent use (Boone & Lefkowitz, 2004; Hogben et al., 2006; Manlove, Ikramullah, & Terry-Humen, 2008; Small et al., 2009). Attitudes toward condoms are also related to peer groups. Adolescents had more favorable condom attitudes when they were able to talk to friends about sex, which was associated with intention and actual condom use behavior (Halpern-Felsher, Kropp, Boyer, Tschann & Ellen, 2004). Adolescents reported encouraging friends to carry and use condoms, and becoming angry with friends who did not use condoms (Harper, Gannon, Watson, Catania & Dolcini, 2004).

Peer norms

While adolescents receive messages about sex from many sources, including parents, school, sexuality education and media, peers are often their preferred source of information (Potard et al., 2008; Teitelman, Bohinksi & Boente, 2009). Focus groups with female adolescents suggest that initial sources of learning about puberty, reproduction, and intercourse are parents and formal sexuality education programs; however, girls often turn to peers for more specific information, including non-intercourse sex, appropriateness of sexual behaviors, and timing of behaviors within romantic relationships (Aronowitz, Rennells & Todd, 2006; Teitelman et al., 2009). Adolescents reported often talking with peers about dating and sex, and peers play significant roles in new partner acquisition (Harper et al., 2004).

Adolescents’ sexual activity is influenced by perceived peer attitudes and behaviors. Perceived norms can influence timing of adolescents’ first sexual encounter (Kirby, 2001; L’Engle & Jackson, 2008; Santelli et al., 2004; Sieving, Eisenberg, Pettingell & Skay, 2006). Adolescents with peer norms favorable to sex are more likely to engage in intercourse at earlier ages. Longitudinal studies found that peer norms were one of the best predictors of initiating sexual intercourse for young adolescents (Santelli et al., 2004). Adolescents with personal beliefs and perceived peer norms favoring abstinence were less likely to initiate sex before the end of eighth grade compared to adolescents with lower pro-abstinence norms (Santelli et al., 2004). Similarly, adolescents who perceived permissive peer attitudes toward premarital sex were more likely to engage in sex, have sex more frequently, and have more sexual partners (Kirby, 2001).

Peer norms also influence adolescents’ decisions to use condoms once they become sexually active. Consistent condom use is associated with regular discussion with friends about contraception and STI risk (Kapadia et al., 2012). Additionally, adolescents who reported communication with peers about sex had more positive condom attitudes, which in turn related to intention and actual condom use (Halpern-Felsher et al., 2004).

Adolescents who perceived favorable condom peer norms were more likely to use condoms. In a study of Latino adolescents, individuals who reported their peers favored condom use were six times more likely to report consistent use (Kapadia et al., 2012). Kirby (2001) also found that adolescents who believe their peers favor condom use and actually use condoms are more likely to use condoms themselves. Longitudinal studies have also shown consistent condom use decreases when perceived peer sex attitudes become more permissive and when adolescents believe their friends are having sex without a condom (Henry, Schoeny, Deptula & Slavick, 2007). Other studies have shown that peer norms favoring condoms increase adolescents’ condom use intention but not necessarily consistent condom use. Specifically, adolescents were more likely to endorse beliefs that they would refuse to have sex without condoms and they would demand condoms for sexual encounters with new partners if they believed peers supported condom use; however, this did not translate into actual behavior (Potard et al., 2008).

Self-efficacy

Abstinent adolescents often cite an ability to refuse sex and terminate relationships with those who try to pressure them into sex (Morrison-Beedy, Carey, Côté-Arsenault, Seibold-Simpson & Robinson, 2008). This perceived behavioral control, or self-efficacy to remain abstinent, may allow adolescents to be resilient to pressure to have intercourse (Morrison-Beedy et al., 2008). Youth with a greater sense of self-efficacy in general and in sexual contexts were more likely to abstain than youth with lower self-efficacy (Pearson, 2006). Abstinent female adolescents have higher self-efficacy to refuse unwanted sex, communicate with partners about condoms, and purchase and use condoms than sexually active females (Childs et al., 2008). Self-efficacy to refuse sex and to use condoms has been associated with abstinence in adolescents in seventh grade, but increased likelihood of sexual initiation the following year (Santelli et al., 2004).

Overall, adolescent males have lower sexual self-efficacy than their female counterparts, especially for refusing sex (Rostosky, Dekhtyar, Cupp & Anderman, 2008; Smith, Steen, Schwendiger, Spaulding-Givens & Brooks, 2005). Although males typically have lower self-efficacy to remain abstinent, they often have greater condom use self-efficacy (Morrison et al., 2007). In AA male adolescents, sexual self-efficacy was associated with condom use intention and perceived certainty of future condom use, and actual condom use was associated with adolescents’ self-efficacy to refuse unwanted sex (Colon, Wiatrek & Evans, 2000).

Sexual self-efficacy is an important factor in adolescents’ condom use intentions and actual use (Alvarez et al., 2010; VanCampen & Romero, 2012). Adolescent female narratives of sexual encounters showed positive condom attitude was not sufficient in guaranteeing use (Suvivuo, Tossavainen & Kontula, 2009). Adolescents who used condoms had high and stable self-efficacy, and situational factors like alcohol use, arousal, and partner unwillingness did not change condom use decisions, whereas adolescents who did not use condoms had lower and unstable self-efficacy (Suvivuo et al., 2009).

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to determine what factors may predict sexual behavior and condom use in a sample of AA adolescents, and if the type of sexuality education received impacts these factors. Based on the theory of planned behavior, we expect attitudes, peer norms, and self-efficacy to predict sexual behavior and condom use.

Hypotheses

Descriptive hypotheses were:

-

1)

Sex attitudes, peer norms regarding sex, and sexual self-efficacy will predict adolescents’ sexual behavior.

-

2)

Condom attitudes, peer norms regarding condom use, and condom use self-efficacy will predict condom use.

Intervention-related hypotheses were:

-

3)

Adolescents receiving abstinence-only sexuality education (AOE) will report less recent sexual activity, less favorable sex attitudes, fewer peer norms supporting sex, and greater sexual self-efficacy than adolescents who receive comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) or the comparison group.

-

4)

Adolescents receiving CSE will report more condom use, more positive condom attitudes, greater peer norms supporting condom use, and greater condom use self-efficacy than adolescents who receive AOE or the comparison group.

Method

Participants

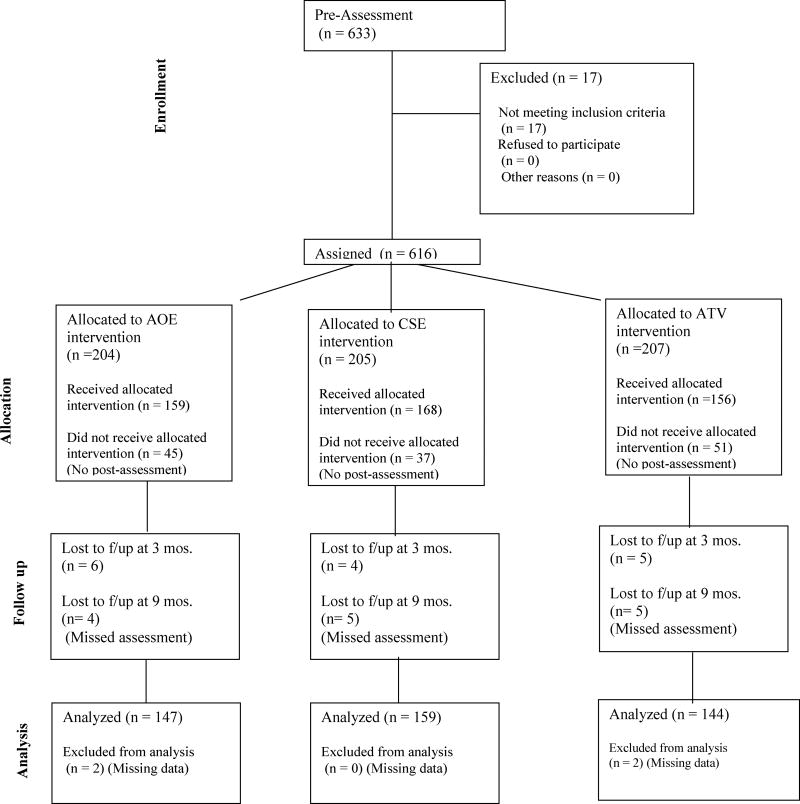

Participants were a volunteer, self-selected convenience sample of 633 students recruited from three middle schools in an urban setting in the southern United States. Eligibility criteria included enrollment in one of the targeted schools, capability to give informed assent, parental/guardian consent, and age 12–14 at enrollment. Seventeen participants identified as a race other than AA and were excluded from the analyses, as well as four participants who had missing pretest data. Average age of AA participants enrolled in the study was 12.87 (SD=.79), 50.5% were female and 40.5% male. Over half of the participants were in seventh grade at time of enrollment (18.5% in sixth grade, 56% in seventh grade, 25.5% in eighth grade). Median household income was $16,214. The average number of adults in the household 1.88 (median=2), and the average number of child was 2.93 (median=3). The majority of parents reported completing twelfth grade or higher (81.4%) and 64.7% reported full or part-time employment. Of the 612 eligible participants, 450 AA youth completed the study per protocol (73.05%) and were included in intervention-related analyses. Attrition rates did not vary by intervention. The primary reason for attrition was absenteeism due to competing activities. It should be noted that attrition was higher for groups conducted in the summer. See participant flow chart (Figure 1). Participants who complete the study were more likely to be female (53.3% female, 46.7% male) and had lower household income (median=$14,000); however, they did not differ in terms of age (M=12.82, SD=.78), grade level (18% sixth grade, 56.9% seventh grade, 25.1% eighth grade), household make up (Madults=1.92, Mchildren=2.91), parent education level (81.3% completing twelfth grade or higher), or parent employment (64.9% full or part-time employment).

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Chart

Procedure

Participants were recruited in 13 waves of 48 (16 per intervention; eight males and eight females per intervention), via flyers posted at schools, classroom solicitations, and announcements during general assemblies. It should be noted that four waves contained over 48 participants because nine students (1.24%) who completed the pretest assessment withdrew prior to the first intervention session and were replaced. Interested students were provided consent forms for parent/guardian review and signature. Parental permission to participate in the interventions and complete assessment batteries was verified by researchers via phone, and then parents/guardians were asked to complete a parent information questionnaire, which included demographic information such as employment status, annual household income, and number of members in the household. After verification, students’ rights as participants were explained and informed assent was obtained. Participants then completed the pretest assessment and were scheduled to start intervention sessions within a week.

Data were collected through Audio Computer Assisted Self Interview (ACASI). Participants were provided headphones to individually listen to pre-recorded audio as items appeared on a computer screen. Researchers entered identification numbers for participants and allowed them to complete practice questions. Participants then completed the assessment privately unless assistance was requested. Average completion time was 20 minutes. Assessments were primarily conducted at school during participants’ free period, but also conducted in participants’ home or researchers’ office during summer vacation. Data points for assessment were pre, immediately post-intervention, 3 months post-intervention, and 9 months post-intervention. Participants received a total of $55 for their participation.

Using a block design, participants were assigned (determined by school attended) to participate in one of three interventions: Becoming a Responsible Teen, an evidence-based comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) intervention (CDC, 2013); Choosing the Best Path, an abstinence-only sexuality education (AOE) intervention (Cook, 2001); or African Tradition and Vibes, an interactive intervention developed for the comparison group. Each intervention was delivered in eight 90-minute weekly group sessions lead by trained research assistants (each group consisted of 16 participants, eight males and eight females). It should be noted that the AOE intervention was modified by the developer from its original 50 minute segments to the 90 minute format utilized in this study. Intervention sessions were conducted during the same 8-week period at the researchers’ office. As a quality assurance measure, all intervention sessions were audio-taped, and those cassette tapes were reviewed by the project director to insure that fidelity of the intervention was maintained. Bus transportation was arranged through the school district to assure maximum attendance rate. See Appendix A for details of each intervention.

The Institutional Review Board of Jackson State University approved the study.

Measures

Sexual behavior

Sexual behavior was assessed with a single item: “Have you had vaginal sex in the past two months? Vaginal sex means when a man puts his penis in a woman’s vagina.” (No=0, Yes=1).

Condom use

Condom use percentage was assessed for participants who reported recent vaginal sex. It was calculated by dividing participants’ answer the item: “Think of the times you had vaginal sex, how many of those times did you do it without a condom?” by their answer to the item “How many times did you have vaginal sex?”

Attitude toward sex

The variable for sex attitudes was based on 13 researcher-developed items regarding values toward intercourse (e.g., “It is against my values to have sexual intercourse as a teenager.”). Items were measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “agree a lot” to “disagree a lot,” and summed. Possible composite scores ranged from 13 to 52, with higher scores representing more favorable attitudes toward sexual intercourse. A reliability analysis for pretest data resulted in Cronbach’s α of .79.

Attitude toward condoms

Participants’ attitude toward condoms was measured using the Condom Attitude Scale modified for adolescents (St. Lawrence et al., 1994). The scale included 23 items pertaining to beliefs and attitudes toward condoms (e.g., “Using condoms shows my partner that I care about him/her.”) Participants responded to items using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Responses were summed to create a composite variable with possible scores ranging from 23 to 161, with higher scores representing more favorable condom attitudes. A reliability analysis for pretest data resulted in Cronbach’s α of .73.

Sexual social norms

Social norms toward sex was measured by three items modified from the Youth Health Risk Behavioral Inventory (YHRBI; Stanton et al., 1995): “How many of your close friends have sex?”, “How many of the boys you know have sex?”, and “How many of the girls you know have sex?” (None=0, Some=3, Most=5). Items were summed to create a composite variable with possible scores ranging from 0 to 15, with higher scores representing social norms more favorable toward sex. A reliability analysis for pretest data resulted in Cronbach’s α of .75.

Condom use social norms

Social norms toward condom use was measured by three items modified from the YHRBI (Stanton et al., 1995): “Of your close friends who have had sex, how many use condoms”, “Of the boys you know who have had sex, how many use condoms?”, “Of the girls you know who have had sex, how many use condoms?” (None=0, Some=3, Most=5). Participants’ available responses were averaged to create a composite variable with possible scores ranging from 0 to 5, with higher scores representing more favorable social norms toward condom use. A reliability analysis for pretest data resulted in Cronbach’s α of .63.

Sexual self-efficacy

Sexual self-efficacy was measured using two items modified from the YHRBI (Stanton et al., 1995) “I would be able to say no to someone I was going with if I didn’t want to have sex” and “I can go with a person for a long time and not have sex with them.” Participants responded to items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Items were summed to create a composite variable with possible scores ranging from 2 to 10, with higher scores representing greater self-efficacy to resist sex. A reliability analysis for pretest data resulted in Cronbach’s α of .65.

Condom self-efficacy

Condom self-efficacy was based on three items modified from the YHRBI (Stanton et al., 1995): “I could convince my [girlfriend/boyfriend] that we should use a condom even if [she/he] doesn’t want to,” “I could ask for condoms in a store,” and “I could refuse to have sex if my [girlfriend/boyfriend] will not use a condom.” Participants responded to items using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Responses were summed to create a composite variable with possible scores ranging from 3 to 15, with higher scores representing greater condom self-efficacy. A reliability analysis for pretest data resulted in Cronbach’s α of .48.

Data Analysis Plan

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and percentages were conducted to describe sample demographics and variables of interest. A logistic regression analysis was conducted for recent vaginal sex using all AA participants who completed the pretest assessment (n=612). A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted for percent of condom use among AA participants who reported recent sexual behavior at pretest (n=35).

Intervention-related hypotheses were analyzed using the subset of the sample that identified as AA and completed all assessment points per protocol. Participants who did not complete assessments at one or more time points were deleted case-wise, yielding in 450 AA youth (73.5%) included in the intervention-related analyses. Mixed-design repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to determine the main effects of time and group and the interaction effect of time by group for recent vaginal sex, attitudes toward sex and condoms, social norms toward sex and condoms, and sexual and condom self-efficacy. The Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used to adjustment for sphericity. Post hoc analyses were conducted to determine the nature of any significant main effects of time and group on the variables of interest. The use of ACASI resulted in near perfect response rate to items, with the exception of items pertaining to social norms toward condoms, which were skipped by participants if they indicated that their close friends and the girls and boys they know were not sexually active. To correct for the large number of missing values on individual items (20.3–43.9% missing), a composite variable using the mean of available scores was used. Despite this correction, data was unavailable for 4.6–11.4% of the sample at each time point, and these cases were excluded from the repeated measures ANOVA for social norms toward condoms. Intervention effects for percent of condom use were analyzed only for participants who reported recent vaginal sex. Because the sample of sexually active participants changed at each time point, separate ANOVAs were conducted to determine group differences at each time period. Data for the per protocol analyses were analyzed using SPSS 18 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Intention to treat analyses (ITTA) were conducted for all AA participants who were enrolled in the study. Around 20% of data were missing on each variable across all time points. To address this issue, multilevel multiple imputation was used. Multiple imputation is a state-of-the-art approach for addressing missing data that yields more accurate and powerful results than common alternatives such as case deletion or single imputation (Schafer & Graham 2002); multilevel multiple imputation is needed for longitudinal data where multiple data points are collected per participant (Enders, Mistler & Keller, 2016). This procedure was implemented using the chained equations approach via the “mice” package for R (Van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn 2011).

All variables included in the ITTA, including higher-order transformations and interaction effects, were included as auxiliary variables during multiple imputation. Imputations were made using the heteroscedastic linear two-level model by a Gibbs sampler (i.e. the “2l.norm” method) with random slopes. All imputations were post-processed (i.e., “squeezed”) to stay within a plausible range. Based on recommendations informed by simulation studies for the among of missing data (Graham, Olchowski & Gilreath, 2007), a total of 20 imputed datasets were created. Convergence was achieved for all variables within 20 iterations, as assessed by visual inspection of mean and SD plots.

Statistical analyses on each imputed dataset were conducted using linear mixed-effects modeling. This procedure was implemented using the “lme4” package for R (Bates, Machler, Bolker & Walker, 2015). In each model, a single dependent variable was predicted using a linear combination of predictor variables representing time of assessment (i.e., time, time squared, and time cubed), dummy codes representing group membership, and time-by-group interactions; random intercepts were included in the models but not random slopes. To facilitate comparison to per protocol results, ANOVA tables were computed for the results of these models, and the F values for each imputed dataset were pooled using the “miceadds” package in R. For the model predicting recent vaginal sex (a binary variable), generalized linear mixed-effects modeling was used; due to convergence issues, the time squared and time cubed variables were omitted from this model. For the model predicting the percentage of condom nonuse, only participants who reported being sexually active at one or more timepoints were include (n=97). Within this subsample, around 60% of observations were missing for condom use. A separate multilevel multiple imputation was conducted for this subsample and, due to its higher fraction of missing information, a total of 40 imputed datasets was created. Convergence was achieved for all variables within 10 iterations, as assessed by visual inspection of mean and SD plots.

Results

Descriptive Hypotheses 1 and 2

Predictors of Sexual Behavior

A logistic regression was conducted to predict vaginal sex in the past two months at pretest using sex attitudes, peer norms toward sex, and sexual self-efficacy at pretest as predictors. A test of the full model against a constant only model was significant (χ2=49.77 p<.001, df=3). Participants with favorable sex attitudes (OR=1.11, 95% CI[1.04, 1.17], p=.001) and peer norms favoring sex (OR=1.31, 95% CI[1.15, 1.49], p<.001) were more likely to report vaginal sex within the past two months. Sexual self-efficacy was not a significant predictor of recent vaginal sex.

Predictors of Condom Use

Of the 612 total AA participants, 34 adolescents reported having vaginal sex in the past two months at pretest. A multiple linear regression was calculated to predict sexually active participants’ percent of sex without condoms in the past two months based on condom attitudes, social norms regarding condom use, and condom self-efficacy. The results indicated that none of the variables significantly predicted the percent of times that condoms were not used for vaginal sex in the past two months (F[3,30]=1.06, p=.380).

Intervention-related Hypotheses 3 and 4

Sexual Behavior

A mixed-design repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to determine intervention effects on vaginal sex in the past two months. There was a significant main effect of time (pretest, posttest, 3 months posttest, 9 months posttest) on recent vaginal sex (F[2.91, 1324.88]=3.95, p=.008, η2=.009). Specifically, pairwise comparisons showed that less participants reported recent vaginal sex at pretest than at 9 months posttest (p=.010). There was no significant main effect of group (AOE, CSE, comparison) on vaginal sex in the past two months (F[2, 455]=.90, p=.408, , η2=.004) or interaction of group by time on recent vaginal sex (F[5.82, 1324.88]=.53, p=.780, , η2=.002). See Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of Participants Reporting Recent Vaginal Sex

| Group | Pretest n (%) |

Posttest n (%) |

3 months n (%) |

9 months n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOE | 10 (7.30) | 12 (8.89) | 9 (6.52) | 13 (9.70) |

| CSE | 12 (8.16) | 18 (11.32) | 14 (9.65) | 21 (15.21) |

| Comparison | 9 (6.67) | 11 (7.64) | 12 (8.33) | 19 (15.20) |

Note. Percentages were calculated for participants who completed the study per protocol.

Condom Use

No significant differences in the percent of condom nonuse were noted at pretest or at posttest; however, the groups differed significantly at 3 months posttest (F[2,32]=3.97, p=.029, η2=.199). Tukey’s HSD revealed the AOE group had a significantly higher percent of unprotected vaginal sex than the comparison group (p=.022). No significant differences were found between the CSE and AOE group (p=.167) or comparison group (p=.506). The groups’ condom use did not significantly differ at 9 months posttest. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Average Percent of Unprotected Vaginal Sex

| Group | Pretest M (SD) |

Posttest M (SD) |

3 months M (SD) |

9 months M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOE | 21.67 (0.33) | 43.38 (0.18) | 36.11 (0.42) | 14.84 (0.30) |

| CSE | 4.92 (0.14) | 22.87 (0.33) | 13.81 (0.28) | 6.55 (0.17) |

| Comparison | 16.64 (0.19) | 10.91 (0.30) | 1.39 (0.30) | 19.82 (0.29) |

Note. Percent of unprotected vaginal sex was calculated only for participants who reported recent vaginal sex at the respective timepoint.

Attitudes toward Sex

There was no significant main effect of time on attitudes toward sex (F[(2.77, 1260.91]=.80, p=.487, η2=.002), and no effect of the time by group interaction on attitudes toward sex (F[5.54]=1.91, p=.082, η2= .008). A significant main effect of group was noted (F[2,455]=3.67, p=.026, η2=.016). Post hoc analyses revealed that the AOE group had significantly less favorable attitudes toward sex than the comparison group (p=.030); however, there were no differences between the CSE and AOE group (p=.139) or comparison group (p=1.00). See Table 3.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables by Group over Time

| Variables by group | n | Pretest M (SD) |

Posttest M (SD) |

3 months M (SD) |

9 months M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex attitudes | |||||

| AOE | 147 | 22.83 (7.38) | 21.42 (6.66) | 22.05 (6.36) | 22.50 (6.42) |

| CSE | 159 | 23.55 (6.86) | 23.80 (6.89) | 23.40 (6.70) | 23.34 (6.39) |

| Comparison | 144 | 23.67 (6.90) | 23.76 (7.02) | 24.16 (7.08) | 24.20 (6.61) |

| Condom attitudes | |||||

| AOE | 147 | 125.07 (15.19) | 118.91 (16.87) | 122.23 (15.26) | 122.56 (14.96) |

| CSE | 159 | 123.23 (15.88) | 129.99 (17.25) | 129.91 (15.88) | 129.81 (17.39) |

| Comparison | 144 | 123.92 (16.00) | 124.36 (15.01) | 120.86 (15.00) | 123.56 (14.55) |

| Sex social norms | |||||

| AOE | 147 | 7.91 (4.57) | 9.28 (4.36) | 9.46 (4.03) | 10.55 (3.62) |

| CSE | 159 | 7.50 (4.37) | 9.72 (4.11) | 9.92 (4.10) | 10.78 (3.87) |

| Comparison | 144 | 7.59 (4.18) | 8.91 (3.92) | 9.24 (4.01) | 10.49 (3.72) |

| Condom social norms | |||||

| AOE | 122 | 3.94 (1.03) | 4.00 (0.91) | 4.19 (0.97) | 4.05 (0.97) |

| CSE | 135 | 3.78 (1.26) | 3.74 (1.04) | 3.98 (0.95) | 3.83 (1.08) |

| Comparison | 120 | 3.79 (1.15) | 3.90 (1.09) | 3.97 (1.04) | 4.00 (0.99) |

| Sexual self-efficacy | |||||

| AOE | 147 | 7.43 (2.48) | 7.87 (2.32) | 8.12 (2.09) | 8.11 (1.98) |

| CSE | 159 | 7.43 (2.38) | 778 (2.33) | 7.75 (2.19) | 7.87 (2.10) |

| Comparison | 144 | 7.44 (2.48) | 7.19 (2.67) | 8.11 (2.11) | 8.00 (2.09) |

| Condom self-efficacy | |||||

| AOE | 147 | 11.03 (2.44) | 11.27 (2.89) | 11.91 (2.20) | 12.08 (2.07) |

| CSE | 159 | 11.27 (2.67) | 12.19 (2.56) | 12.17 (1.91) | 12.49 (1.94) |

| Comparison | 144 | 11.32 (2.75) | 11.15 (3.11) | 11.74 (2.49) | 11.81 (2.26) |

Note. Means and standard deviations were calculated for participants who completed the study per protocol.

Attitudes toward Condoms

There was no main effect of time on attitudes towards condoms (F[2.80, 1273.51]=1.23, p=.299, η2=.003; however, there was a significant main effect of group (F[2,455]=9.91, p<.001, η2=.042). Post hoc analyses revealed that the AOE group had significantly less favorable attitudes toward condoms than the CSE group (p<.001) or the comparison group (p=.001). No difference were found between the CSE and comparison groups (p=1.000). See Table 3. Additionally, there was a significant group by time interaction effect on attitudes towards condoms (F[5.60, 1273.51]=102.51, p<.001, η2=.056). See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Condom Attitude Scale Scores Over Time by Group

Social norms toward sex

There was a significant main effect of time on social norms toward sex (F[2.91, 1322.68]=102.51, p<.001, η2=.184). Pairwise comparisons showed that participants were less likely to have social norms favoring sex at pretest than at posttest (p<.001), 3 months posttest (p<.001), and 9 months posttest (p<.001). They were also less likely to have social norms favoring sex at posttest compared to 9 months posttest (p<.001) and at 3 months posttest compared to 9 months posttest (p<.001). The main effect of group (F[2,455]=.59, p=.554, η2=.006) and the interaction of group by time (F[5.81, 1322.68, p=.223, η2=.003) were not significant. See Table 3.

Social norms toward condom use

A significant main effect of time on social norms toward condom use was found (F[2.82, 1077.32]=6.37, p<.001, η2=.016). Specifically, participants were less likely to have social norms favoring condom use at pretest than at 3 months posttest (p=.002) or at 9 months posttest (p=.039). They also were less likely to have social norms favoring condom use at posttest than at 3 months posttest (p=.008). There was no significant main effect for group (F[2,382]=2.55, p=.079, η2=.013) and no interaction of group by time (F[5.64, 1077.32)=.94, p=.219, η2=.007). See Table 3.

Sexual self-efficacy

There was a significant main effect of time on sexual self-efficacy (F[2.91, 1321.68]=10.41, p<.001, η2=.022). Participants had lower sexual self-efficacy at pretest compared to 3 months posttest (p<.001) and 9 months posttest (p<.001), as well as at posttest compared to 3 months posttest (p=.012) and 9 months posttest (p=.014). There was also a significant interaction of group by time (F[5.81,1321.68]=2.15, p=.048, η2=.009). No main effect of group was noted (F[2,455]=.71, p=.491, η2=.003). See Table 3.

Condom self-efficacy

There was a significant main effect of time on condom self-efficacy (F[2.82, 1283.49]=13.13, p<.001, η2=.028). Pairwise comparisons revealed that participants had lower condom self-efficacy at pretest than at 3 months posttest (p<.001) and 9 months posttest (p<.001), as well as lower condom self-efficacy at posttest than at 9 months posttest (p=.021). There was also a significant main effect of group on condom self-efficacy (F[2,455]=3.75, p=.024, η2=.016). Post hoc analyses that the CSE group tended to have higher condom self-efficacy than the AOE group (p=.056) and the comparison group (p=.056), but these differences were not statistically significant. There was no interaction effect of group by time on condom self-efficacy (F[5.57, 593.90]=1.01, p=.413, η2=.009). See Table 3.

Intention to Treat Analyses (ITTA)

ITTA were conducted using linear mixed-effects modeling using all AA participants who were enrolled in the study. Overall results yielded similar patterns for main effects of time and group and interaction effects of time by group for variables of interest. Unlike the intervention the intervention-relate analyses, the ITTA revealed a significant interaction of group by time and group by time squared. ITTA did not reveal a significant main effect of time, time squared, or time cubed for social norms towards condoms unlike the intervention-related analyses. For sexual self-efficacy, ITTA showed a significant main effect of group; however, there was no significant effect of time, time squared, or time cube. Additionally, ITTA differed from the per protocol analyses for condom self-efficacy with no main effect of group, time, time squared, or time cubed. Finally, ITTA revealed no significant effects of group, time, time squared, time cubed, or interaction of group by any time. See table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of Results of Intention to Treat Analyses

| Variable | F(df) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Recent sexual behavior | ||

| time | 7.22 (1, 17857.61) | 0.007** |

| group | 0.01 (2, 15808.50) | 0.992 |

| group × time | 1.00 (2, 9737.92) | 0.366 |

| Condom use (n=97) | ||

| time | 1.10 (1, 138.55) | 0.296 |

| time squared | 0.57 (1, 314.71) | 0.453 |

| time cubed | 0.23 (1, 1512.70) | 0.628 |

| group | 0.72 (2, 307.17) | 0.488 |

| group × time | 0.44 (2, 257.93) | 0.643 |

| group × time squared | 0.44 (2, 586.76) | 0.643 |

| group × time cubed | 0.37 (2, 791.54) | 0.693 |

| Sex attitudes | ||

| time | 0.59 (1, 160.72) | 0.442 |

| time squared | 1.99 (1, 241.43) | 0.160 |

| time cubed | 0.44 (1, 422.64) | 0.509 |

| group | 4.09 (2, 630.82) | 0.017* |

| group × time | 0.47 (2, 79.10) | 0.627 |

| group × time squared | 2.24 (2, 487.09) | 0.107 |

| group × time cubed | 0.50 (2, 282.39) | 0.605) |

| Condom attitudes | ||

| time | 0.59 (1, 110.59) | 0.444 |

| time squared | 0.54 (1, 228.12) | 0.465 |

| time cubed | 0.32 (1, 386.17) | 0.570 |

| group | 9.65 (2,559.53) | <0.001*** |

| group × time | 6.50 (2, 153.34) | 0.002** |

| group × time squared | 4.42 (2, 74.03) | 0.015* |

| group × time cubed | 2.76 (2, 129.59) | 0.067 |

| Sex social norms | ||

| time | 228.83 (1, 214.26) | <0.001*** |

| time squared | 5.51 (1, 3012.23) | 0.019* |

| time cubed | 9.56 (1, 293.60) | 0.002** |

| group | 0.23 (2, 2013.17) | 0.794 |

| group × time | 1.04 (2, 224.70) | 0.356 |

| group × time squared | 2.35 (2, 1025.44) | 0.096 |

| group × time cubed | 0.22 (2, 628.00) | 0.803 |

| Condom social norms | ||

| time | 15.98 (1, 163.24) | <0.001*** |

| time squared | 0.64 (1, 592.54) | 0.424 |

| time cubed | 0.99 (1, 329.80) | 0.320 |

| group | 2.62 (2, 337.41) | 0.075 |

| group × time | 0.18 (2, 370.56) | 0.832 |

| group × time squared | 0.19 (2, 353.34) | 0.827 |

| group × time cubed | 1.37 (2, 274.03) | 0.256 |

| Sexual self-efficacy | ||

| time | 24.89 (1, 708.50) | <0.001*** |

| time squared | 1.27 (1, 278.64) | 0.261 |

| time cubed | 0.48 (1, 765.71) | 0.490 |

| group | 0.66 (2, 427.51) | 0.518 |

| group × time | 1.28 (2, 1192.12) | 0.278 |

| group × time squared | 0.72 (2, 615.57) | 0.488 |

| group × time cubed | 2.89 (2, 454.47) | 0.057 |

| Condom self-efficacy | ||

| time | 35.95 (1, 230.75) | <0.001*** |

| time squared | 1.42 (1, 451.59) | 0.234 |

| time cubed | 0.28 (1, 1030.33) | 0.597 |

| group | 2.95 (2, 605.92) | 0.053 |

| group × time | 1.57 (2, 1712.93( | 0.208 |

| group × time squared | 0.47 (2, 719.01) | 0.625 |

| group × time cubed | 0.45 (2, 598.21) | 0.635 |

Note. Linear mixed-effects modeling was used for the intention to treat analyses. n=612 unless otherwise denoted

p-value <= 0.05

p-value <= 0.01

p-value <=0.001

Discussion

This study examined the utility of attitudes, social norms, and self-efficacy as predictors of AA adolescents’ recent sexual activity and condom use. The study’s findings partially supported the descriptive hypotheses based on the theory of planned behavior. Specifically, attitudes and social norms toward sex explained a small but significant amount of variance in recent sexual activity. However, self-efficacy did not predict sexual activity as hypothesized, and condom use was not predicted by any of the variables.

The study was based on the theory of planned behavior, which proposes attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control predict behavioral intention, which in turn predicts behavior (Ajzen, 1985). Unlike the theory of planned behavior, this study examined the role of attitudes, social norms, and self-efficacy directly on behavior. It is possible that attitudes, social norms, and self-efficacy predict condom use intention, and barriers not assessed, such as access and availability of condoms, prevent condom use intention from translating into actual behavior. It is also possible that self-efficacy as measured by this study did not adequately represent perceived behavioral control. It should be noted that self-efficacy scales used, particularly condom self-efficacy, yielded low Cronbach’s α, and may have not accurately represented participants’ self-efficacy. Additionally, the condom social norms scale used was limited due to the amount of data missing not at random. Items on this scale were skipped by participants who denied that any of their close friends, or boys and girls they know, were sexually active. It is unknown how having less social norms favoring sex impacts social norms towards condoms. Further studies utilizing validated self-efficacy and social norms scales for AA adolescents are warranted to determine the role of self-efficacy and social norms in sexual behavior and condom use.

It was hypothesized that the type of sexuality education received would impact AA adolescents’ attitudes, social norms, self-efficacy, and behavior. Specifically, it was expected that AOE would result in less favorable sex attitudes, less social norms favoring sex, and greater sexual self-efficacy compared to the CSE or comparison group, and the changes in attitudes, social norms, and self-efficacy would result in less sexual activity. As hypothesized, the AOE group had less favorable sex attitudes immediately post-intervention than the comparison group; however, there was no overall intervention effect. Other studies have demonstrated feasibility in impacting adolescents’ abstinence attitudes through interventions (Borawski, Trapl, Lovegreen, Colabianchi & Block, 2005; Di Noia & Schinke, 2007; Haglund, 2008; Smith et al., 2005). Participants demonstrated more social norms favoring sex over time without regard to intervention type. Participants in both types of sexuality education demonstrated greater sexual self-efficacy post-intervention. Recent sexual activity increased over time without regard to intervention. Although sex attitudes predicted recent sexual behavior and the AOE group demonstrated less favorable sex attitudes than the comparison group post-intervention, the change in attitudes alone was not enough to impact behavior. Other studies evaluating AOE in AA middle school students demonstrated similar changes in attitudes; however, they found that more positive abstinence attitudes were related to reduced intention to have sex and reduced sexual initiation (Zhang, Jemmott & Jemmott, 2015). The differences in intervention effectiveness may be related to the differences in sexual history. Zhang and colleagues (2015) utilized sexually naïve AA youth, whereas about a quarter of the participants in the current study were sexually experienced at pretest. Zanis (2005) found that AOE interventions are not effective in changing sexual activity among sexually experienced adolescents.

Additionally, it was hypothesized that participants receiving CSE would have more favorable condom attitudes, greater condom use social norms, and greater condom use self-efficacy than the AOE or comparison groups, and therefore, be more likely to use condoms. As hypothesized, the CSE group had significantly more favorable condom attitudes then the AOE and comparison group. The interventions demonstrated a medium effect on condom attitudes, with the CSE having a positive and enduring effect on favorable condom attitudes. Participants had greater social norms favoring condom use and greater condom self-efficacy over time, but this did not appear to be influenced by intervention type. While favorable condom attitudes may be important in adolescents’ condom use decisions, attitudes were not a predictor of condom use in this study, and therefore, changing adolescents’ attitudes was not effective in increasing condom usage. Studies of CSE intervention in AA high school students have shown significant and positive intervention effects on condom attitudes and self-efficacy, but no impact on social norms regarding sex or condom use (Walsh, Jenner, Leger & Broussard, 2015). It may be possible that the CSE is not as effective in changing self-efficacy in younger adolescents. Walsh and colleagues (2015) found CSE significantly increased condom use intention, but they did not report on actual condom use behavior. It is possible that CSE positively influenced condom use intention in the current sample though changes in actual behavior may have been masked due to few participants reporting recent sexual behavior.

Previous studies show that adolescents who receive CSE are less likely to report teen pregnancy and history of vaginal intercourse compared to adolescents with no formal sexuality education, whereas adolescents receiving AOE show no additional benefit (Kohler, Manhart & Lafferty, 2008). In a review of AOE and CSE interventions, Kirby (2008) found that most AOEs are not effective in delaying sexual initiation, but about two-thirds of CSEs show positive evidence in delaying sexual initiation or increasing condom use. However, these studies do not explicitly address the effects of sexuality education on higher risk populations, such as AA adolescents. There are few studies comparing AOE and CSE interventions for AA adolescents; however, one study found AOE to be effective in reducing sexual activity and CSE to be effective in increasing consistent condom use among AA adolescents (Jemmott, Jemmott & Fong, 1998). Neither intervention in the current study was effective in reducing AA adolescents’ sexual behavior or increasing condom use compared to the comparison group, though it is important to note that AOE negatively impacted condom attitudes which may have contributed to the increased likelihood of unprotected sex.

Based on our findings, future interventions should promote favorable attitudes and social norms towards abstinence and condom use. Although norms did not significantly predict condom use in the current study, other studies have shown that adolescents with positive condom normative beliefs are more likely to use condoms themselves (Kapadia et al., 2012; Kirby, 2001). The current study limited social norms to peers, but perceived romantic partner and family norms may also contribute to condom use decisions. Adolescents often view condom cessation as a sign of trust and commitment in relationships (Akers et al., 2012), and condom use intention may be mitigated by partners’ perceived negative attitudes, especially for females (Hogben et al., 2006). Interventions promoting condom negotiation skills within the context of relationships may be beneficial in increasing condom use. Other research has shown child-parent relationships and communication regarding condoms impacts consistent condom use (Hadley et al., 2009; Harris, Sutherland & Hutchinson, 2013), and parent involvement in interventions may be valuable in reducing unprotected sex. Thus, interventions implemented across a broader spectrum (peer social networks, schools, communities) may be a more effective strategy for promoting safe, sexually responsible behaviors than interventions that focus only on individual behavior change.

Several limitations should be noted for the present study. This was not a randomized controlled trial. Randomization for the study occurred at the school level, but data were analyzed on an individual level. Data were only collected from adolescents whose parents/guardians gave permission to participate, and therefore it is not possible to know if there were differences between students who did or did not participate. The current study also used multiple statistical tests, which increased the likelihood of Type I error, and the descriptive analyses used cross sectional data. Therefore, caution should be used in interpreting the results. In addition, participants in the study lived in an urban area in the Southeastern United States, and results may not generalize to AA adolescents who live in rural areas or other locations. Participating schools were within the same city, and it is feasible that participants in the different groups may have interacted outside of school which may have resulted in an exchange of information regarding what they were taught in the interventions. The current study utilized recent vaginal sex to measure sexual behavior, and it is important to note that only about a third of students who reported lifetime history of intercourse also reported sexual behavior at any time point. The low number of participants reporting recent vaginal intercourse may be due to underreporting of behavior and caution should be used in interpreting the results. The sexually active participants in sample changed at each time point, and therefore, a repeated measures ANOVA was unable to be conducted for condom use. Separate one-way ANOVAs were utilized at each time point, and thus, the interaction of time by group could not be assessed. Further, oral and anal sex were excluded from the current study because few participants reported either behavior. It is unknown if interventions would have impacted rates of oral and anal sex or condom use for these behaviors. Finally, this study did not examine the effectiveness of the AOE and CSE interventions by gender. It is possible that the interventions impacted sexual behaviors differently for adolescent boys and girls and that potential differences were canceled out when subgroup data was pooled rather than analyzed separately.

It should also be noted that the main outcome analyses were conducted for participants who completed the study per protocol. ITTA were conducted using multiple imputation to account for participants who withdrew from the study or were lost to follow-up. Overall, the ITTA had similar results to the main outcome analyses, but there were several incidences where the results diverged. Discrepancy in the results may have been caused by the nature of the missing data. It is possible that data were not missing at random as the sample who completed the study were more likely to be female and have lower household incomes compared to all participants enrolled in the study, and it is unknown if other variables not assessed contributed to attrition. If data were not missing at random, analyses using multiple imputation can lead to just as much or more bias compared to per protocol analyses (Sterne, 2009). One instance of important note where ITTA diverged from the per protocol analyses is for condom use. There were no significant group, any time, or group by any time differences for percent condom nonuse in the ITTA whereas we found a significant group difference at the 3-month posttest for the per protocol analyses. This difference may have been the result of different analytic approaches used (i.e., linear mixed-effects modeling for ITTA and ANOVA for per protocol analyses). It is also important to note that ITTA for percent condom nonuse was only conducted for the small subset who reported sexual activity at any timepoint (n=97). It is unknown how many non-sexually active participants withdrew or were lost to follow-up but became sexually active in the subsequent post-assessment period.

Despite limitations, important implications of sexuality education for AA adolescents emerged from this study. First, social norms and attitudes toward sex were important factors in young adolescents’ sexual behavior. In developing new sex education programs that target AA adolescents, these areas should be highlighted. However, these factors only accounted for a small portion of variance. Additionally, attitudes, social norms, and self-efficacy were not predictive of AA adolescents’ condom use, and further research is warranted to determine what other factors play a role in the sexual behavior and condom use decision making of this group. Also, neither intervention was more effective than the other in significantly influencing the sexual behavior of AA adolescents. However, the AOE may have put participants at increased risk because it negatively impacted their condom use, a method that has been proven to be an effective strategy for reducing negative consequences associated with early initiation of sexual behavior.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; RO1HD39122).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lindsay M. Shepherd, Department of Psychology, Jackson State University

Kaye F. Sly, Department of Psychology, Jackson State University

Jeffrey M. Girard, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center

References

- Abbott DA, Dalla RL. ‘It’s a choice, simple as that’: Youth reasoning for sexual abstinence or activity. Journal of Youth Studies. 2008;11:629–649. doi: 10.1080/13676260802225751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, editors. Action control: From cognition to behavior. Berlin, Heidelber, New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Akers AY, Gold MA, Bost JE, Adimora AA, Orr DP, Fortenberry JD. Variation in sexual behaviors in a cohort of adolescent females: The role of personal, perceived peer, and perceived family attitudes. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers AY, Gold MA, Coyne-Beasley T, Corbie-Smith G. A qualitative study of rural Black adolescents’ perspectives on primary STD prevention strategies. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2012;44:92–99. doi: 10.1363/4409212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez C, Villarruel AM, Zhou Y, Gallegos E. Predictors of condom use among Mexican adolescents. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal. 2010;24:187–196. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.24.3.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KM, Koo HP, Jenkins RR, Walker LR, Davis M, Yao Q, El-Khorazaty MN. Attitudes, experience, and anticipation of sex among 5th graders in an urban setting: Does gender matter? Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011:S54–S64. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0879-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronowitz T, Rennells RE, Todd E. Ecological influences of sexuality on early adolescent African American females. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2006;23:113–122. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Machler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software. 2015;67:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Boone TL, Lefkowitz ES. Safer sex and the health belief model: Considering the contributions of peer norms and socialization factors. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 2004;16:51–68. doi: 10.1300/J0565v16n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borawski EA, Trapl ES, Lovegreen LD, Colabianchi N, Block T. Effectiveness of abstinence-only intervention in middle school teens. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2005;29:423–434. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2005.29.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Compendium of evidence-based interventions and best practices for HIV prevention: Becoming a Reponsible Teen (Bart.) 2013 Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/rr/bart.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63:1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Childs G, Moneyham L, Felton G. Correlates of sexual abstinence and sexual activity of low-income African American adolescent females. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19:432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook B. Choosing the best PATH. Marietta, Georgia: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cohan M. Adolescent heterosexual males talk about the role of male peer groups in their sexual-decision making. Sexuality & Culture. 2009;13:152–177. doi: 10.1007/s12119-009-9052-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colon RM, Wiatrek DE, Evans RI. The relationship between psychosocial factors and condom use among African American adolescents. Adolescence. 2000;35:559–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Noia J, Schinke SP. Gender-specific HIV prevention with urban early-adolescent girls: Outcomes of the Keepin’ It Safe program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19:479–488. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.6.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Mistler SA, Keller BT. Multilevel multiple imputation: A review and evaluation of joint modeling and chained equations imputation. Psychological Methods. 2016;21:222–240. doi: 10.1037/met0000063. https://doi.org/10.1037/met000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley W, Brown LK, Lescano CM, Kell H, Spalding K, DiClemente R, Donenberg G. Parent-adolescent sexual communication: Associations of condom use with condom discussions. AIDS Behavior. 2009;13:997–1004. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-98468-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund K. Reducing sexual risk with practice of periodic secondary abstinence. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2008;37:647–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Felsher BL, Kropp RY, Boyer CB, Tschann JM, Ellen JM. Adolescents’ self-efficacy to communicate about sex: Its role in condom attitudes, commitment, and use. Adolescence. 2004;39:443–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Gannon C, Watson SE, Catania JA, Dolcini MM. The role of close friends in African American adolescents’ dating and sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 2004;41:351–362. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AL, Sutherland MA, Hutchinson MK. Parental influences of sexual risk among urban African American adolescent males. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2013;45:141–150. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Schoeny ME, Deptula DP, Slavick JT. Peer selection and socialization effects on adolescent intercourse without a condom and attitudes about the cost of sex. Child Development. 2007;78:825–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogben M, Liddon N, Pierce A, Sawyer M, Papp JR, Black CM, et al. Incorporating adolescent females’ perception of their partners’ attitudes toward condoms into a model of female adolescent condom use. Psychology Health & Medicine. 2006;11:449–460. doi: 10.1080/13548500500463964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:1529–1536. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia F, Frye V, Bonner S, Emmanuel PJ, Samples CL, Latka MH. Perceived peer safer sex norms and sexual risk behaviors among substance-using Latino adolescents. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2012;24:27–40. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. Understanding what works and what doesn’t in reducing adolescent sexual risk-taking. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;33:276–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby DB. The impact of abstinence and comprehensive sex and STD/HIV education programs on adolescent sexual behavior. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: A Journal of the NSRC. 2008;5:18–27. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2009.5.3.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler PK, Manhart LE, Lafferty WE. Abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education and the initiation of sexual activity and teen pregnancy. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FA, Lewis RK, Kirk CM. Sexual attitudes and behaviors among adolescents. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2011;39:277–288. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2011.606399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L’Engle KL, Jackson C. Socialization influences on early adolescent cognitive susceptibility and transition to sexual intercourse. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18:353–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00563.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manlove J, Ikramullah E, Terry-Humen E. Condom use and consistency among male adolescents in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters BA, Beadnell DM, Morrison M, Hoppe J, Gilmore MR. The opposite of sex? Adolescents’ thoughts about abstinence and sex, and their sexual behavior. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2008;40:87–93. doi: 10.13663/4008708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison DM, Hoppe MJ, Wells E, Beadnell BA, Wilsdon A, Higa D, Casey EA. Replicating a teen HIV/STD preventive intervention in a multicultural city. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19:258–273. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Côté-Arsenault D, Seibold-Simpson S, Robinson KA. Understanding sexual abstinence in urban adolescent girls. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2008;37:185–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott MA, Pfeiffer EJ, Fortenberry JD. Perceptions of sexual abstinence among high-risk early and middle adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:192–198. doi: 10.1016/jadohealth.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J. Personal control, self-efficacy in sexual negotiation, and contraceptive risk among adolescents: The role of gender. Sex Roles. 2006;54:615–625. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9028-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Potard C, Courtois R, Rusch E. The influence of peers on risky behaviour during adolescence. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care. 2008;13:264–270. doi: 10.1080/13625180802273530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Dekhtyar O, Cupp PK, Anderman EM. Sexual self-concept and sexual self-efficacy in adolescents: A possible clue to promoting sexual health? Journal of Sex Research. 2008;45:277–286. doi: 10.1080/00224490802204480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer HR, Keller ML, Heidrich SM. Young adolescents’ perceptions of romantic relationships and sexual activity. Sex Education. 2009;9:395–408. doi: 10.1080/1481810903265329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Kaiser J, Hirsch L, Radosh A, Simkin L, Middlestadt S. Initiation of sexual intercourse among middle school adolescents: The influence of psychosocial factors. Journal of Adolescents. 2004;34:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Lindberg LD, Finer LB, Singh S. Explaining recent declines in adolescent pregnancy in the United States: The contribution of abstinence and improved contraceptive use. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:150–156. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.089169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, Eisenberg ME, Pettingell S, Skay C. Friends’ influence on adolescents’ first sexual intercourse. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38:13–19. doi: 10.1363/3801306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small E, Weinman ML, Buzi RS, Smith PB. Risk factors, knowledge, and attitudes as predictors of intent to use condoms among minority female adolescents attending family planning clinics. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services. 2009;8:251–268. doi: 10.1080/15381500903130504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TE, Steen JA, Schwendinger A, Spaulding-Givens J, Brooks RG. Gender differences in adolescent attitudes and receptivity to sexual abstinence education. Children & Schools. 2005;27:45–50. doi: 10.1093/cs/27.1.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- St Lawrence JS, Reitman D, Jefferson KW, Alleyne E, Brasfield TL, Shirley A. Factor structure and validations of an adolescent version of the Condom Attitude Scale: An instrument for measuring adolescents’ attitudes toward condoms. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:352–359. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton B, Black M, Feigelman S, Ricardo I, Galbraith J, Li X, et al. Development of a culturally, theoretically and developmentally based survey instrument for assessing risk behaviors among African-American early adolescents living in urban low-income neighborhoos. AIDS Education Prevention. 1995;7:160–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JAC. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. British Medical Journal. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvivuo P, Tossavainen K, Kontula O. Contraceptive use and non-use among teenage girls in a sexually motivated situation. Sex Education. 2009;9:355–369. doi: 10.1080/14681810903264769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM, Bohinski JM, Boente A. The social context of sexual health and sexual risk for urban adolescent girls in the United States. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30:460–469. doi: 10.1080/01612840802641735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Multivariate imputation by chained equations. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Van Campen KS, Romero AJ. How are self-efficacy and family involvement associated with less sexual risk taking among ethnic minority adolescents? Family Relations. 2012;61:548–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00721.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh S, Jenner E, Leger R, Broussard M. Effects of a sexual risk reduction program for African-American adolescents on social cognitive antecedent of behavior change. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2015;39:610–622. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.5.3. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.39.5.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS. Mediation and moderation of an efficacious theory-based abstinence-only intervention for African American adolescents. Health Psychology. 2015;34:1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/hea0000244. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/hea0000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.