Abstract

Background and Aims

Current clinical guidelines identify several psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). IBS patients, however, have elevated trauma, life stress, relationship conflicts, and emotional avoidance, which few therapies directly target. We tested the effects of emotional awareness and expression training (EAET) compared to an evidence-based comparison condition—relaxation training—and a waitlist control condition.

Methods

Adults with IBS (N = 106; 80% female, Mean age = 36 years) were randomized to EAET, relaxation training, or waitlist control. Both EAET and relaxation training were administered in three, weekly, 50-minute, individual sessions. All patients completed the IBS Symptom Severity Scale (primary outcome), IBS Quality of Life, and Brief Symptom Inventory (anxiety, depressive, and hostility symptoms) at pretreatment and at 2 weeks post-treatment and 10 weeks follow-up (primary endpoint).

Results

Compared to waitlist controls, EAET, but not relaxation training, significantly reduced IBS symptom severity at 10-week follow-up. Both EAET and relaxation training improved quality of life at follow-up. Finally, EAET did not reduce psychological symptoms, whereas relaxation training reduced depressive symptoms at follow-up (and anxiety symptoms at post-treatment).

Conclusions

Brief emotional awareness and expression training that targeted trauma and emotional conflicts reduced somatic symptoms and improved quality of life in patients with IBS. This emotion-focused approach may be considered an additional treatment option for IBS, although research should compare EAET to a full cognitive-behavioral protocol and determine which patients are best suited for each approach.

Registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01886027)

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, clinical trial, emotional expression, relaxation

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic, often debilitating disorder that occurs in approximately 14% of U.S. adults1 and is the most common disorder seen by gastroenterologists. For the millions of patients who do not respond adequately to pharmacological and dietary interventions, IBS remains a significant cause of discomfort and distress2, life interference3, healthcare utilization4, and financial cost5. There is a clear need for additional options to help patients and providers more effectively treat IBS.

Most empirically-supported psychological approaches to IBS are multicomponent variations of cognitive-behavioral therapy6. These treatments target primarily thoughts, behaviors, and psychophysiological processes that aggravate IBS7. Although cognitive-behavioral approaches are generally efficacious, patients often continue to experience residual somatic symptoms, limited quality of life, and psychological symptoms. This may be because cognitive-behavioral therapies do not directly target certain risk factors that augment IBS symptoms and impair functioning. Compared to healthy controls, patients with IBS report elevated rates of early life adversity, including general trauma as well as physical, emotional, and sexual abuse 8, 9, and post-traumatic stress disorder has been shown to be a risk factor for IBS symptoms10. Interpersonal problems11–13 and emotional unawareness and avoidance14 also are elevated among patients with IBS, although exact prevalence data are lacking, due, in part, to variations in definitions of these problems. In contrast to most current cognitive-behavioral symptom management therapies, psychological treatments that involve identifying, experiencing, and expressing trauma- and conflict-related emotions have been found to be effective for various interpersonal, psychiatric, and somatic disorders15, 16. Little research, however, has examined such interventions for IBS.

This study sought to characterize the value of a structured, brief psychological treatment, which we have labeled emotional awareness and expression training (EAET), for IBS. This treatment seeks to help patients improve their ability to identify, experience, and express emotions related to stressful life experiences or emotional conflicts and respond adaptively in interpersonal relationships. We compared EAET to both a waitlist control condition and an evidence-based comparator intervention for IBS, relaxation training17. We hypothesized that EAET would lead to greater improvement in IBS symptom severity (primary outcome), quality of life, and psychological symptoms than waitlist control, and we explored how EAET compared with relaxation training.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Adults with IBS were recruited from the community and university through newspaper and internet advertisements and from gastroenterology clinics by flyers. Interested individuals had their eligibility criteria assessed by telephone: 18 to 80 years old, fulfillment of Rome III diagnostic criteria for IBS18 and current IBS symptoms at least 2 days per week. Exclusions were organic gastrointestinal disease (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, colon cancer), postinfectious IBS, immunodeficiency, current psychotic disorder, drug or alcohol dependence within the past 2 years, or inability to speak English. Eligible individuals had an in-person visit at the Wayne State University Stress and Health Laboratory, where they reviewed study procedures, provided written informed consent, and gave permission to contact their physicians to confirm our IBS diagnosis. The study was approved by the local IRB and preregistered before recruitment (June 2013 through January 2015; follow-ups completed in March 2015).

Study Design and Randomization

This single-site, 3-arm, randomized controlled trial compared EAET to a comparison intervention (relaxation training) and a waitlist control condition. A computer-based randomization schedule was developed by an independent person using randomization.com, and sealed envelopes contained the randomization assignments. To control for the effects of specific therapist and patient gender and equate arms for sample size19, randomization was stratified by participant gender and therapist and conducted in randomized blocks of 3 and 6.

Experimental Conditions

Patients assigned to either EAET or relaxation training participated in three, 50-minute sessions over 3 consecutive weeks. Session 1 began immediately after baseline assessment, and sessions 2 and 3 occurred at weekly intervals over the next 2 weeks. All therapy sessions were conducted individually an in-person. Follow-up assessments were at 2 weeks post-treatment and 10 weeks follow-up (primary endpoint) for EAET and relaxation training, and the equivalent time for waitlist controls. Patients were paid $20 for each assessment, and treatments were provided at no charge.

Both EAET and relaxation training were manualized and conducted by 1 of 5 female therapists (graduate students in clinical psychology or a masters-level nurse). Therapists were trained and supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist, and each therapist administered both EAET and relaxation training to control for therapist effects. Sessions were audio-recorded for supervision.

Emotional Awareness and Expression Training

This intervention is based on the principle that life stress accompanied by emotional suppression can lead to chronic overarousal, dysregulate the brain-gut neuroenteric system, and trigger or exacerbate IBS symptoms. EAET seeks to reduce stress and improve health by: a) helping patients recognize their own stress-gut links and realize that the avoidance of emotionally difficult interpersonal experiences is a key stressor; b) teaching patients to identify, experience, and express their emotions related to stressful experiences; and c) encouraging patients to engage in emotionally honest and direct interpersonal communication.

Session 1 included a presentation of the model and a life history interview, focusing on the link between stress and IBS symptoms. Homework involved expressive writing about key conflicted relationships. Session 2 focused on experiencing and expressing avoided memories and feelings related to traumatic or stressful relationships. A conflicted interpersonal situation was identified, and the patient was encouraged by the therapist to experience emotions bodily and communicate these emotions directly, out loud, with genuine tone of voice and facial and physical expression to an “empty chair,” as if the other person were present. Both feelings of power and independence (e.g., anger) and connection and dependence (e.g., sadness, love, healthy guilt) were targeted for expression. Homework involved monitoring relationships and indirect or avoided communication. Session 3 taught people to communicate more directly in relationships, balancing assertive with connecting communication, and included role plays and ways to implement emotional expression and communication skills in daily life.

Relaxation Training

This comparison intervention is an evidence-based treatment for IBS17 that provided a very different conceptual framework and change processes, yet was matched to EAET on numerous factors (session format, length, and number; provision of a credible rationale; patient activity and homework; therapist contact and support, and learning new skills.) The rationale provided for relaxation training is that stress causes physiological arousal, exacerbates symptoms, and dysregulates brain-gut communication. The goal of relaxation training is to reduce IBS symptoms and psychological distress and improve quality of life by directly attenuating physiological arousal and enhancing regulatory self-efficacy. Session 1 presented the model and taught patients progressive muscle relaxation, session 2 taught relaxed breathing techniques, and session 3 taught guided imagery. Sessions 2 and 3 also included applied relaxation techniques, and session 3 included goal setting and incorporation of relaxation skills into daily life. For between-session homework, patients listened to an audio recording that guided them through the various relaxation techniques.

Waitlist Control

These patients continued to engage in their usual medical, dietary, or behavioral treatments for their IBS (as did all patients in the study), but control patients were given no additional treatment. They were informed that they would be offered the option to participate in the intervention of their choice (EAET or relaxation training) after the 10-week follow-up.

Outcome Measures

At baseline and 2- and 10-week follow-up assessments, patients completed self-report measures of IBS symptom severity (prespecified primary outcome), quality of life, and psychological symptoms (secondary outcomes).

The 5-item IBS Symptom Severity Scale (IBS-SSS) assessed the severity and frequency of abdominal pain, severity of abdominal distention, dissatisfaction with bowel habits, and interference over the last 10 days.20 Items were rated on a 100-point scale and summed. (Scores from 75 – 175: mild severity, 175 – 300: moderate severity, 300 or greater: severe).18 Based on standard practice, we classified patients as clinically improved in symptoms if their IBS-SSS decreased at least 50 points from baseline21.

The 34-item IBS Quality of Life Scale assessed how IBS impacts quality of life. Items were rated on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) scale and summed; higher scores indicate poorer quality of life.22, 23

Subscales from the 53-item Brief Symptom Inventory assessed symptoms of anxiety, depression, and hostility24. Patients rated symptoms over the past 2 weeks from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), and we averaged the ratings for each subscale.

Statistical Analyses

Sample size was determined via power analysis to test the difference between EAET and waitlist control. Based on prior studies of EAET-related interventions,25, 26 we estimated a standardized effect size for this comparison of 0.75 SD. To obtain 80% power using a 2-tailed alpha of p < .05 in a repeated-measures design, 34 patients per treatment condition were required.

Preliminary analyses examined the success of randomization by comparing the three conditions on demographics and baseline levels of outcome measures, using analyses of variance (ANOVA) or chi-squares, as indicated. Primary analyses were mixed-model (between-subjects and within-subject) repeated-measures ANOVAs on the full randomized sample (intent-to-treat); missing outcome values were replaced with the patient’s last value carried forward. We first conducted “omnibus” repeated-measures ANOVAs on each of the five outcomes, simultaneously comparing all three conditions across all three time points (baseline, post-treatment, and 10-week follow-up). Significant omnibus condition by time interactions (indicating condition differences over the three times) were followed by planned repeated measures ANOVAs at post-treatment and follow-up separately. We probed significant condition by time interactions by conducting repeated measures ANVOAs on pairs of conditions (EAET vs. relaxation training, EAET vs. control, relaxation training vs. control). For our primary outcome of IBS-SSS, we also determined the percentage of patients clinically improved at each time point, and compared conditions with chi-square analyses.

We calculated effect sizes between conditions for on each outcome measure as the standardized difference in change between 2 conditions: ([follow-up minus baseline for condition 1)] minus [follow-up minus baseline for condition 2]), divided by pooled SD of change scores. Negative effects size values indicate that the first condition had greater improvements (reductions in the outcome) than the second; positive values indicate the opposite. An effect size of 0.20 SD is considered small in magnitude, 0.50 SD is medium, and 0.80 SD is large. Analyses were conducted with SPSS 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Alpha was set at .05 (2-tailed) for all tests.

Results

Patient Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, the sample was, on average, female (80.2%), not married or partnered (72.6%), European American (65.1%, but with substantial ethnic diversity), young to middle age (M = 36.1 years), and with IBS symptoms of moderate severity for over two decades. Most patients’ physicians (79%) replied to our record request, and all confirmed our IBS diagnosis. Analyses of baseline data indicated that the three conditions did not differ significantly on background variables (Table 1) or baseline levels of outcomes (Table 2).

Table 1.

Sample and Treatment Condition Descriptive Data

| Variable | Full Sample (N = 106) |

Emotional Awareness Expression Training (n = 36) |

Relaxation Training (n = 36) |

Waitlist Control (n = 34) |

F/χ² value |

p- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | M (SD) | 36.14 (16.42) | 40.36 (17.89) | 34.11 (15.22) | 33.82 (15.58) | 1.83 | .17 |

| Gender | 0.02 | .99 | |||||

| Male | n (%) | 21 (19.8) | 7 (19.4) | 7 (19.4) | 7 (20.6) | ||

| Female | n (%) | 85 (80.2) | 29 (80.6) | 29 (80.6) | 27 (79.4) | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.73 | .70 | |||||

| European American | n (%) | 69 (65.1) | 22 (61.1) | 23 (63.9) | 24 (70.6) | ||

| African American | n (%) | 24 (22.6) | 7 (19.4) | 9 (25.0) | 8 (23.5) | ||

| Middle Eastern | n (%) | 4 (3.8) | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.9) | ||

| South Asian | n (%) | 3 (2.8) | 2 (5.6) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| East Asian | n (%) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other | n (%) | 4 (3.8) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (8.3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Marital Status | n (%) | 4.32 | .12 | ||||

| Married/living together | n (%) | 34 (32.1) | 15 (41.7) | 7 (19.4) | 12 (35.3) | ||

| Never married | n (%) | 61 (57.5) | 17 (47.2) | 25 (69.4) | 19 (55.9) | ||

| Divorced/separated | n (%) | 10 (9.4) | 3 (8.3) | 4 (11.2) | 3 (8.8) | ||

| Widowed | n (%) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Duration of symptoms | M (SD) | 22.90 (12.84) | 23.47 (12.83) | 23.58 (12.78) | 21.57 (13.21) | 0.26 | .77 |

Note. All tests were 2-tailed. M = mean; SD = standard deviation;

Chi-square analysis for ethnicity compared European American to all non-European Americans combined.

Chi-square analysis for marital status compared partnered patients (married or living with partner) to all others combined.

Table 2.

Outcome Data for Treatment Conditions at 2-Week Post-treatment and 10-week Follow-up, including Effect Sizes (ES) of Pairwise Condition Comparisons of Change Scores

| Outcome Measure | Time Point | Emotional Awareness & Expression Training (n = 36) |

Relaxation Training (n = 36) |

Waitlist control (n = 34) |

Condition x Time Interaction F |

EAET vs. Relaxation Training ES |

EAET vs. Waitlist ES |

Relaxation training vs. Waitlist ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBS symptom severity | Baseline M (SD) | 273.19 (88.00) | 262.08 (75.11) | 262.79 (83.02) | ||||

| 2-week M (SD) | 187.08 (90.37) | 206.39 (72.98) | 241.25 (95.29) | |||||

| 2-week Change M (SD) | −86.11 (86.47) | −55.69 (86.45) | −21.54 (89.95) | 4.75** | −0.34 | −0.69** | −0.38 | |

| 10-week M (SD) | 178.19 (113.68) | 188.33 (99.90) | 227.35 (110.8) | |||||

| 10-week Change M (SD) | −95.00 (103.84) | −73.75 (102.54) | −35.44 (97.77) | 3.08* | −0.21 | −0.57* | −0.38 | |

| Quality of life (Poor) | Baseline M (SD) | 81.81 (19.45) | 90.21 (27.22) | 82.61 (27.62) | ||||

| 2-week M (SD) | 69.62 (17.95) | 79.41 (24.91) | 84.83 (28.29) | |||||

| 2-week Change M (SD) | −12.20 (17.56) | −10.80 (15.63) | 2.22 (12.33) | 9.27*** | −0.08 | −0.86*** | −0.84*** | |

| 10-week M (SD) | 66.07 (19.68) | 72.63 (26.47) | 79.69 (25.93) | |||||

| 10-week Change M (SD) | −15.75 (23.16) | −17.58 (24.91) | −2.92 (20.88) | 4.15* | −0.08 | −0.56* | −0.61** | |

| Anxiety | Baseline M (SD) | 0.97 (0.76) | 0.97 (0.76) | 1.09 (0.83) | ||||

| 2-week M (SD) | 0.68 (0.72) | 0.62 (0.67) | 1.20 (0.91) | |||||

| 2-week Change M (SD) | −0.22 (0.65) | −0.36 (0.86) | 0.11 (0.67) | 3.66* | 0.18 | −0.48* | −0.58* | |

| 10-wk M (SD) | 0.78 (0.93) | 0.56 (0.61) | 1.01 (0.86) | |||||

| 10-week Change M (SD) | −0.12 (0.77) | −0.41 (0.79) | −0.08 (0.75) | 2.01 | 0.38 | −0.05 | −0.43† | |

| Depression | Baseline M (SD) | 0.61 (0.63) | 0.93 (0.87) | 1.02 (0.91) | ||||

| 2-week M (SD) | 0.64 (0.70) | 0.60 (0.74) | 1.22 (1.17) | |||||

| 2-week Change M (SD) | 0.04 (0.53) | −0.33 (0.76) | 0.20 (0.57) | 6.60** | 0.54* | −0.30 | −0.74** | |

| 10-week M (SD) | 0.56 (0.70) | 0.55 (0.70) | 0.95 (1.07) | |||||

| 10-week Change M (SD) | −0.05 (0.54) | −0.38 (0.78) | −0.07 (0.55) | 3.06* | 0.49* | −0.05 | −0.45† | |

| Hostility | Baseline M (SD) | 0.69 (0.67) | 0.79 (0.60) | 0.85 (0.78) | ||||

| 2-week M (SD) | 0.54 (0.67) | 0.63 (0.52) | 0.92 (0.93) | |||||

| 2-week Change M (SD) | −0.15 (0.50) | −0.16 (0.61) | 0.07 (0.61) | 1.76 | 0.01 | −0.39† | −0.37 | |

| 10-week M (SD) | 0.56 (0.79) | 0.50 (0.46) | 0.70 (0.83) | |||||

| 10-week Change M (SD) | −0.13 (0.57) | −0.29 (0.63) | −0.15 (0.56) | 0.80 | 0.26 | 0.024 | −0.24 |

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

M = mean; SD = standard deviation

Effect size = the standardized difference in change between 2 conditions. Negative values indicate that the first condition had greater improvements than the second; positive values indicate the opposite. A significant effect size indicates that the two conditions differed significantly on change scores, as determined by the condition × time interaction term from a repeated-measures ANOVA.

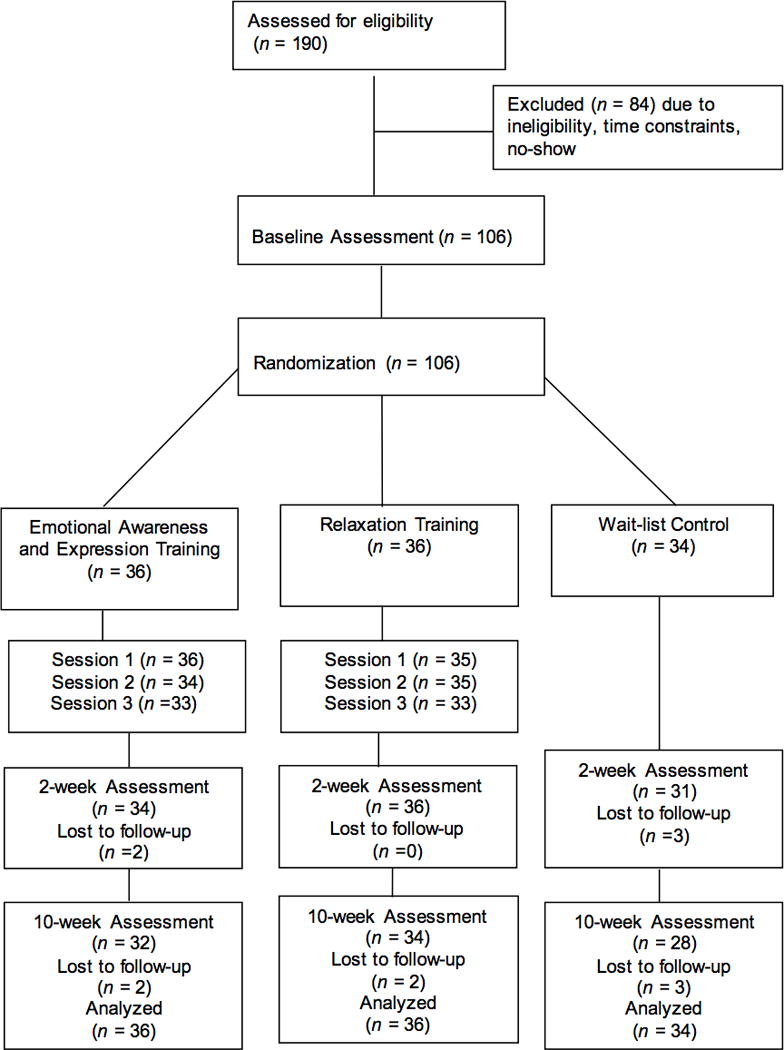

Figure 1 depicts patient flow through the study. Most patients in both EAET and relaxation training (92% in each) completed all three treatment sessions. Attrition was low: five study patients were lost at the post-treatment assessment, and another seven at the 10-week follow-up; thus, only 12 patients (11.3%) did not finish the trial (EAET: n = 4; relaxation training: n = 2, waitlist control: n = 6).

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through the study

Treatment Differences in Outcomes

Table 2 presents data (M, SD) for each outcome measure at each assessment point for each condition. Change scores (post-treatment or follow-up minus baseline) are presented also, along with the effect size and its significance level comparing each pair of conditions.

For the primary outcome of IBS symptoms, the omnibus repeated-measures ANOVA yielded a significant condition by time interaction, F(4, 206) = 2.43, p =.026. At 2 weeks, there was a significant condition by time interaction (see Table 2). EAET had significantly lower IBS symptom severity than waitlist controls (large effect), whereas relaxation training had symptom reduction that was between EAET and controls, but did not differ significantly from either. These findings were very similar at the primary endpoint (10-week follow-up); EAET, but not relaxation training, reduced symptoms more than the waitlist control condition (medium effect). Regarding clinical improvement in IBS symptoms (> 50-point reduction on IBS-SSS), at post-treatment, 69.4% of EAET patients clinically improved, which was marginally greater (p = .09) than the percentage of relaxation training patients (50.0% improvement), and significantly greater (p = .009) than control patients (38.2%). At 10-week follow-up, 63.9% of EAET patients had improved in IBS symptoms, which did not differ significantly from relaxation training (55.6%), but which was marginally greater (p = .097) than controls (44.1%).

For quality of life, the omnibus test had a significant condition by time interaction, F(4, 206) = 4.36, p = .002. At post-treatment, the significant condition by time interaction indicated that both EAET and relaxation training had large magnitude improvements in quality of life, relatively to controls, but EAET and relaxation training did not differ from each other. The findings at 10-week follow-up were similar, although improvements for both treatments were medium in magnitude.

For anxiety, there was an omnibus condition by time interaction, F(4, 206) = 2.69, p = .032. At post-treatment, both EAET and relaxation training had similar effects: medium magnitude reductions in anxiety relative to controls. At 10-week follow-up, the three conditions no longer differed significantly on change in anxiety.

For depression, there was an omnibus condition by time interaction, F(4, 206) = 3.59, p = .003. Interestingly, at post-treatment, relaxation training had significantly lower depression symptoms than both EAET (medium effect) and controls (large effect), which did not differ from each other. At 10-week follow-up, this pattern was similar; relaxation training continued to have significantly lower depressive symptoms than EAET, but was only marginally lower than controls.

Finally, the omnibus test for hostility was not significant, F(4, 206) = 1.47, p = .21. Of interest, however, EAET had marginally lower hostility than controls at post-treatment.

Discussion

This trial found that a brief (3-session) emotion-focused psychological therapy, emotional awareness and expression training (EAET), reduced IBS symptom severity compared with waitlist control at both post-treatment and 10-week follow-up. In contrast, a conceptually different evidence-based intervention, relaxation training, generated lesser reductions in IBS symptoms than did EAET and did not differ from controls. Approximately two-thirds of patients receiving EAET had clinically significant improvements in IBS symptoms, whereas slightly more than half of relaxation training patients, and about 40% of waitlist controls, showed such improvement. These findings suggest that EAET uniquely reduces somatic symptoms by directly targeting the trauma, life stress, and avoided emotional processes experienced by many patients with IBS. Note that this benefit of EAET occurred even though IBS symptoms also improved somewhat among waitlist controls (perhaps due to regression to the mean or the effects of repeated assessment), which attenuated the relative benefits of both EAET and relaxation training.

EAET also substantially improved patients’ quality of life, compared with waitlist controls; however, relaxation training resulted in similar quality-of-life improvements. This finding suggests that EAET does not have a unique advantage over relaxation training in improving IBS quality of life, which can be enhanced in different ways, perhaps through a common mechanism, such as increased self-efficacy or behavioral engagement.

Interestingly, EAET did not improve psychological symptoms of depression or anxiety at follow-up. Relaxation training, in contrast, had medium-sized reductions in these symptoms compared to controls, and relaxation training even surpassed EAET in reduction of depressive symptoms. The failure of EAET to reduce these psychological symptoms may stem from the fact that EAET shifts patients from avoiding to experiencing their negative emotions. Such newfound awareness and experience of difficult feelings may increase—or at least prevent attenuation of—depressive and anxious symptoms. Interestingly, the attenuation of somatic symptoms, but not psychological symptoms, following EAET suggests some support for a classic view of somatization27. Prior to engaging in EAET, patients with IBS may experience and report somatic or physical symptoms rather than emotional symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression). Yet, becoming aware of, experiencing, and expressing one’s psychological difficulties may reduce their somatic symptoms but leave the patients feeling more emotional symptoms. Thus, one might conceptualize an increase in depression or anxiety after EAET as a marker that the patient is successfully engaging in desirable emotional changes and possibly reversing somatization.

The EAET approach is conceptually distinct from most cognitive-behavioral therapies for IBS, which routinely include relaxation training and typically aim to directly attenuate arousal and negative emotions. The benefits of EAET found here support the results of an uncontrolled trial of written emotional disclosure about stressful experiences, which found reduced IBS symptoms, particularly among participants with longer-duration IBS28. More generally, several clinical trials have demonstrated that emotional awareness and expression interventions improve health outcomes for patients with various chronic pain disorders25, 26. Although early research suggested that it might be unhelpful or even iatrogenic to directly activate anger in patients with chronic pain29, 30, our results refute this. Not only did IBS symptoms and quality of life improve after an intervention that purposely activated and encouraged expression of anger in session, but EAET patients’ later hostility ratings decreased slightly, and were marginally lower than those of controls at post-treatment. These findings underscore the adaptive value of activating and expressing avoided negative emotions, including anger. Supporting adaptive anger expression is particularly important, given that victimization8 and emotional and relational conflicts11, 12 typically elicit justifiable anger; and these experiences are increased among patients with IBS, contributing to the presence and intensity of their symptoms.8, 31

There is some support for other emotion-focused or insight-oriented interventions for IBS, such as psychodynamic therapy32, 33, interpersonal therapy31, 34, emotional awareness training35, and exposure to gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety36. These interventions, however, do not target both the disclosure of stressful life events and the experience and adaptive expression of inhibited emotions related to these events. The latter processes appear to be key mechanisms in reducing symptoms in chronic pain and related somatic disorders37–41.

This study has limitations. First, although we compared EAET to a bonafide intervention, relaxation training, which was similar to EAET on many non-specific therapeutic factors, our controls were only on a waitlist. As such, this condition did not control for non-specific aspects of treatment, such as patient engagement or therapist attention or support, and may have overestimated the comparative efficacy of the two interventions because some patients may have been disappointed that they were not randomized to an active intervention. Ideally, a credible, active control condition (e.g., education) would be used. Second, the somewhat small sample size limited statistical power to detect the modest differences expected between a new treatment (EAET) and a comparison treatment (relaxation training); replication with larger samples is indicated. Third, a longer follow-up would be ideal because resolution of emotional conflicts, reductions in distress, and improvements in relationships stimulated by EAET likely require more than 10 weeks to occur. Fourth, we did not conduct diagnostic interviews to formally assess psychiatric disorders in our sample, which limited our ability to describe this sample psychiatrically or confirm that conditions were comparable on these disorders. Fifth, our outcomes were solely self-reported, and other methods (e.g., symptom diaries, physician-rated measures) and outcomes (e.g., healthcare utilization, interpersonal relationships) would provide a clearer picture of the effects of both EAET and relaxation training. Sixth, data analysis was not conducted blind to condition assignment, and research assistants who oversaw follow-up assessments were not necessarily blinded, although their interactions with patients was minimal, given that patients completed questionnaires in private. Finally, our findings generalize only to people with IBS from the community. It would be ideal to see how EAET works with patients recruited at clinics, who likely have more severe IBS and greater psychological distress than community participants.42

Regarding clinical applicability, EAET is likely not appropriate for all people with IBS. Rather, only a subset of patients will need and be able to engage in this emotionally intense therapy. We did not test individual differences or patient factors in this study; however, to best direct clinical care, future research should identify for whom this intervention is optimally suited. Furthermore, a 3-session “dose” of EAET is likely insufficient for many patients to enhance their emotional awareness, express inhibited affect, resolve psychological conflicts, and change the way they engage in important relationships. A longer course of EAET likely would have greater impact. Comparing EAET to relaxation training is a good start, but it would be ideal to compare EAET to a complete cognitive-behavioral treatment for IBS, of which relaxation training is typically only one component. Researchers should also consider challenges that continue to hinder successful implementation of behavioral health services in gastroenterology, including limited availability of trained clinicians, stigma associated with mental health care, and insufficient reimbursement for psychological services.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the feasibility of a brief emotional awareness and expression intervention for IBS and confirmed its efficacy for IBS symptom reduction and improved quality of life. For patients and clinicians, this novel approach offers an additional treatment option, which is likely to be cost effective, reduce unwarranted medical costs, and enhance patients’ ability to respond adaptively to life stressors.

Key Points.

IBS patients often have elevated life stress, relationship conflicts, and emotional suppression, which current psychological therapies do not directly target. This randomized, clinical trial compared the effects of emotional awareness and expression training with a comparison condition, relaxation training, and a waitlist control condition.

Emotional awareness and expression training significantly reduced IBS symptoms and improved quality of life, although not psychological symptoms.

This novel approach offers an additional treatment option, which has the potential to improve health outcomes for patients with IBS.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments, Funding and Disclosures

This research was funded by grants from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of Michigan, American Psychological Association, and Wayne State University awarded to Elyse R. Thakur; and supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health under award numbers AR057808 and AR057047. The work was also supported by resources and facilities at the Houston VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN13-413). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. government, or Baylor College of Medicine.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analyses of variance

- EAET

emotional awareness and expression training

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- IBS-SSS

IBS Symptom Severity Scale

Footnotes

Guarantor of article: Mark A. Lumley

Specific author contributions: This research is based on the doctoral dissertation of the first author (ERT) under the direction of the last author (MAL). Elyse Thakur and Mark Lumley participated in study design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation; Hannah Holmes participated in data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation; Nancy Lockhart, Jennifer Carty, Maisa Ziadni, and Heather Doherty participated in data collection and manuscript preparation; Jeffrey Lackner and Howard Schubiner participated in study design, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation.

All authors approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hungin A, Chang L, Locke G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1365–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, Zack MM, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: can less be more? Psychosom Med. 2006;68:312–320. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204897.25745.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camilleri M, Chang L. Challenges to the therapeutic pipeline for irritable bowel syndrome: end points and regulatory hurdles. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1877–1891. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russo MW, Gaynes BN, Drossman DA. A national survey of practice patterns of gastroenterologists with comparison to the past two decades. J of Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:339–343. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longstreth GF, Wilson A, Knight K, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome, health care use, and costs: a US managed care perspective. Am J of Gastroenterol. 2003;98:600–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J of Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1350–1365. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toner BB, Segal ZV, Emmott S, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Group Psychother. 1998;48:215–243. doi: 10.1080/00207284.1998.11491537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drossman DA. Abuse, trauma, and GI illness: is there a link? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:14–25. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradford K, Shih W, Videlock EJ, et al. Association between early adverse life events and irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.12.018. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobie DJ, Kivlahan DR, Maynard C, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in female veterans: association with self-reported health problems and functional impairment. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:394–400. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lackner JM, Gurtman MB. Patterns of interpersonal problems in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a circumplex analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58:523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thakur ER, Gurtman MB, Keefer L, et al. Gender differences in irritable bowel syndrome: the interpersonal connection. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1478–1486. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bevan JL. Interpersonal communication apprehension, topic avoidance, and the experience of irritable bowel syndrome. Pers Relatsh. 2009;16:147–165. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sayar K, Solmaz M, Trablus S, et al. Alexithymia in irritable bowel syndrome. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2000;11:190–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbass A, Kisely S, Kroenke K. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for somatic disorders. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:265–274. doi: 10.1159/000228247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lane RD, Ryan L, Nadel L, et al. Memory reconsolidation, emotional arousal, and the process of change in psychotherapy: New insights from brain science. Behav Brain Sci. 2015;38:e1. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X14000041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zijdenbos IL, de Wit NJ, van der Heijden GJ, et al. Psychological treatments for the management of irritable bowel syndrome. The Cochrane Library. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006442.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rome III Diagnostic Criteria. Rome Foundation, Inc; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert MJ. The efficacy and effectivenes of psychotherapy. In: Lambert MJ, editor. Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. 6. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. pp. 169–218. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Francis C, Morris J, Whorwell P. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:395–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.142318000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller LE. Study design considerations for irritable bowel syndrome clinical trials. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27:338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Whitehead WE, et al. Further validation of the IBS-QOL: a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:999–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrick DL, Drossman DA, Frederick IO, et al. Quality of life in persons with irritable bowel syndrome: development and validation of a new measure. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:400–411. doi: 10.1023/a:1018831127942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burger AJ, Lumley MA, Carty JN, et al. The effects of a novel psychological attribution and emotional awareness and expression therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: A preliminary, uncontrolled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2016;81:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slavin-Spenny O, Lumley MA, Thakur ER, et al. Effects of anger awareness and expression training versus relaxation training on headaches: A randomized trial. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:181–192. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9500-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellner R. Somatization: theories and research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990;178:150–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halpert A, Rybin D, Doros G. Expressive writing is a promising therapeutic modality for the management of IBS: a pilot study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2440–2448. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beutler LE, Daldrup R, Engle D, et al. Family dynamics and emotional expression among patients with chronic pain and depression. Pain. 1988;32:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beutler LE, Daldrup RJ, Engle D, et al. Effects of therapeutically induced affect arousal on depressive symptoms, pain and beta-endorphins among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Pain. 1987;29:325–334. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hyphantis T, Guthrie E, Tomenson B, et al. Psychodynamic interpersonal therapy and improvement in interpersonal difficulties in people with severe irritable bowel syndrome. Pain. 2009;145:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guthrie E, Creed F, Dawson D, et al. A controlled trial of psychological treatment for the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:450–457. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Ottosson JO, et al. Controlled study of psychotherapy in irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 1983;322:589–592. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creed F, Fernandes L, Guthrie E, et al. The cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy and paroxetine for severe irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:303–317. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farnam A, Somi MH, Farhang S, et al. The therapeutic effect of adding emotional awareness training to standard medical treatment for irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. J Psychiatr Pract. 2014;20:3–11. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000442934.38704.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ljótsson B, Hedman E, Andersson E, et al. Internet-delivered exposure-based treatment vs. stress management for irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1481–1491. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burns JW, Quartana PJ, Bruehl S. Anger inhibition and pain: conceptualizations, evidence and new directions. J Behav Med. 2008;31:259–279. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quartana PJ, Bounds S, Yoon KL, et al. Anger suppression predicts pain, emotional, and cardiovascular responses to the cold pressor. Ann Behav Med. 2010;39:211–221. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kisely S, Abbass A, Kroenke K. Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy for somatic disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:265–274. doi: 10.1159/000228247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lumley MA, Cohen JL, Stout RL, et al. An emotional exposure-based treatment of traumatic stress for people with chronic pain: Preliminary results for fibromyalgia syndrome. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2008;45:165–172. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quartana PJ, Yoon KL, Burns JW. Anger suppression, ironic processes and pain. J Behav Med. 2007;30:455–469. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Longstreth GF, Hawkey CJ, Mayer EA, et al. Characteristics of patients with irritable bowel syndrome recruited from three sources: implications for clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:959–964. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]