ABSTRACT

Introduction: Osteopontin (OPN) polymorphisms are associated with muscle size and modify disease progression in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). We hypothesized that OPN may share a molecular network with myostatin (MSTN). Methods: Studies were conducted in the golden retriever (GRMD) and mdx mouse models of DMD. Follow‐up in‐vitro studies were employed in myogenic cells and the mdx mouse treated with recombinant mouse (rm) or human (Hu) OPN protein. Results: OPN was increased and MSTN was decreased and levels correlated inversely in GRMD hypertrophied muscle. RM‐OPN treatment led to induced AKT1 and FoxO1 phosphorylation, microRNA‐486 modulation, and decreased MSTN. An AKT1 inhibitor blocked these effects, whereas an RGD‐mutant OPN protein and an RGDS blocking peptide showed similar effects to the AKT inhibitor. RMOPN induced myotube hypertrophy and minimal Feret diameter in mdx muscle. Discussion: OPN may interact with AKT1/MSTN/FoxO1 to modify normal and dystrophic muscle. Muscle Nerve 56: 1119–1127, 2017

Keywords: AKT, dog, Duchenne, GRMD, mdx, muscle, myostatin, osteopontin

Abbreviations

- AKT1

AKT serine/threonine kinase 1

- CS

cranial sartorius

- GRMD

golden retriever muscular dystrophy

- DMD

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium

- FoxO1

forkhead box O1

- Hu‐WT OPN

human wild‐type osteopontin (normal RGD sequence)

- Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN

Human mutant osteopontin (lacks RGD sequence)

- ITG

integrin

- miRNA

microRNA

- MSTN

myostatin

- OPN

osteopontin

- PBS

phosphate‐buffered saline

- rmOPN

recombinant mouse osteopontin

- RT‐PCR

reverse transcript–polymerase chain reaction

- SPP1

secreted phosphoprotein 1 (osteopontin)

- TA

tibialis anterior

- TTJ

tibiotarsal

- WT

wild‐type

Osteopontin (OPN; SPP1) is a multifunctional cytokine with diverse functions. Its primary structure includes an arginine–glycine–aspartic acid (RGD) site that mediates interactions with the cell surface integrins (ITGs) αvβ1, αvβ3, and α5β1.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Proteolytic cleavage by thrombin exposes a human SVVYGLR, ITG‐binding motif, expanding the ITG‐binding repertoire to include α4β1, α4β7, and α9β1,1, 6, 7 whereas a heparin‐binding domain allows OPN to bind to CD44.8 OPN also has important roles in cancer progression and inflammation.9, 10, 11, 12

Germane to OPN's role in muscle, a promoter polymorphism (rs28357094) alters transcription factor binding and baseline gene transcription in multiple cell types. The rs28357094 genotype was associated with an increase in biceps muscle size in women but not men,13 in keeping with an effect of estrogens on OPN expression.14, 15, 16 In healthy human muscle, OPN expression increased with acute mechanical loading, further suggesting a role of OPN in muscle injury and hypertrophic remodeling.17 The same rs28357094 polymorphism tracked with loss of muscle strength, motor function, and independent ambulation in 3 separate cohorts of dystrophin‐deficient Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) patients.18, 19 Although not detectable in normal human or mouse muscle, OPN is highly expressed in DMD patient muscle, as well as serum and muscle of dystrophin‐deficient mdx mice and golden retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD) dogs.20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 In vitro, treating C2C12 myoblasts with soluble OPN protein increased proliferation and decreased fusion and migration, whereas insoluble OPN protein promoted adhesion and fusion.27

Given the associations of OPN gene polymorphisms, protein levels with muscle size, and its effects in vitro, we studied relationships between OPN protein and myostatin (MSTN), a known regulator of muscle mass.

METHODS

Animals

All dogs and mice were used and cared for according to principles outlined in the National Research Council's “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.” All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. Dogs were housed either at the University of Missouri (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee No. 2435) or the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee No. 06‐338.0). GRMD dogs were identified as described elsewhere.28 Tibiotarsal (TTJ) joint angle, TTJ joint extensor and flexor tetanic torque, and cranial sartorius (CS) circumference were assessed in all dogs at 6 months of age when phenotypic results best correlate.29, 30, 31, 32, 33 Muscle biopsies were taken at surgery or necropsy, as previously described.34 We also utilized a murine muscle regeneration series from previously published studies.35, 36 Finally, X‐linked muscular dystrophy (mdx) mice were housed at the Children's National Medical Center. At 3 weeks of age, 4 female mdx mice were injected with recombinant mouse osteopontin (rmOPN)/green dye cocktail intramuscularly into the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle of 1 limb and an equal volume of 1× phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS)/green dye cocktail in the contralateral limb. Green dye was used to determine the location of the injection cocktail with microscopy. Mice were necropsied and muscle tissue was harvested.

Cell Culture

The well‐established cell line, H‐2kb‐tsA58 wild‐type (WT), conditionally immortalized murine myoblasts,37, 38 were grown in complete growth medium consisting of Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM), 2% l‐glutamine (Gibco, Carlsbad, California), 1% penicillin and streptomycin (PAA, Dartmouth, Massachusetts), 2% chick embryo extract (Sera Lab, UK), and interferon‐gamma (20 units/ml) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum. Myoblasts were maintained at 33°C (95% air, 5% CO2) as proliferative cells at low densities in complete growth medium. To differentiate myoblasts into myotubes, cells were incubated in DMEM spiked with 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 2% l‐glutamine, and 2% horse serum. Myotubes were allowed to differentiate for 4 or 5 days at 37°C (95% air, 5% CO2). Recombinant mouse (rm) OPN was a fusion protein purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minnesota). One, 5, and 10 μg/ml of rmOPN were added to myoblasts and/or myotubes in a 6‐, 12‐, or 24‐well dish in serum‐free DMEM. Myoblasts were incubated with rmOPN for 24 and 48 hours. AKT inhibitor #124005 [1L6‐hydroxymethyl‐chiro‐inositol‐2‐(R)‐2‐O‐methyl‐3‐O‐octadecyl‐sn‐glycerocarbonate; Calbiochem/EMD4 Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany] was diluted in dimethylsulfoxide and 5 μmol/L (target IC50 to inhibit AKT) was added to individual rmOPN‐treated wells. Myotubes were treated with 10 μg/ml rmOPN (optimal concentration observed in treated myoblasts) at the end of day 4 of differentiation and incubated for 24 hours until the end of day 5 to evaluate MSTN expression. To evaluate hypertrophy, myotubes were differentiated for at least 3 days, then treated for 24–48 hours with 10 μg/ml of rmOPN.

Human (Hu) WT OPN and Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN proteins were a generous gift from Dr. Larry Fisher and were prepared as previously described.17, 39 In Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN, the RGD amino acids were mutated to lysine (K), alanine (A), and glutamic acid (E), respectively.40, 41 For human OPN experiments, H‐2kb‐tsA58 myoblasts were treated with 10 μg/ml of Hu‐WT OPN or Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN for 24 hours in serum‐free growth medium. A peptide that blocks the biological adhesion epitope Arg‐Gly‐Asp‐Ser (RGDS; R&D Systems; Minneapolis, Minnesota) was added at 0.05 (0.25×) and 0.2 (1×) mg/ml to myotubes co‐treated with rmOPN for 24 hours.

Methods for light microscopy, RNA extraction, muscle regeneration time series, total protein and DNA analysis, quantitative reverse transcript–polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR), protein isolation and quantification, Western blot, and enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay can be found in the Supplementary Material available online.

RESULTS

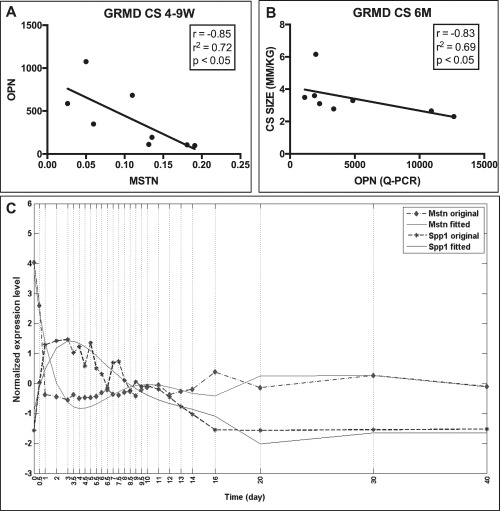

OPN Was Correlated with MSTN and Muscle Size

Quantitative RT‐PCR data from the GRMD CS muscle at 4–9 weeks (with cellular hypertrophy evident but before gross hypertrophy)17, 34 showed a strong negative correlation between OPN (increased) and MSTN (decreased) mRNAs (Fig. 1A). OPN mRNA levels showed an inverse correlation with CS muscle size in GRMD dogs at 6 months (Fig. 1B). OPN levels in the GRMD CS muscle at 6 months correlated positively with TTJ angle and tetanic extensor force (P < 0.05; r > 0.85) and inversely with tetanic flexor force (P < 0.05; r > –0.79) (data not shown). We queried a previously performed murine muscle regeneration time series, which showed a dramatic increase in OPN at day 1 after cardiotoxin intramuscular injection (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, MSTN decreased during the same time period. OPN levels eventually returned to day 0 (pre‐injection) levels, whereas MSTN returned to subnormal levels.

Figure 1.

OPN and MSTN were inversely correlated in GRMD dogs. (A) OPN and MSTN mRNA expression were inversely correlated in the CS at 4–9 weeks in GRMD dogs (r = –0.85, r 2 = 0.72; P < 0.05; n = 8), where myofiber hypertrophy is observed before gross hypertrophy. (B) OPN was inversely correlated with CS muscle circumference in GRMD dogs at 6 months of age (r = –0.83, r 2 = 0.69; P < 0.05; n = 8). (C) Cardiotoxin‐induced muscle injury in WT mice resulted in an immediate and substantial increase in OPN with a temporally concurrent reduction in MSTN expression at day 1 postinjection. OPN levels eventually returned to day 0 (pre‐injection) levels while MSTN returned to subnormal levels.

rmOPN Protein–Treated Cells Had Decreased and Increased MSTN and AKT1 Phosphorylation, Respectively

H‐2kb‐tsA58 WT myoblasts treated with rmOPN showed a dose‐dependent decrease in MSTN mRNA and protein after 24 (Fig. 2A and B) and 48 (Fig. 2C) hours of incubation. MSTN protein levels also decreased in myotubes treated with rmOPN (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Recombinant mouse (rm)OPN treatment decreased MSTN expression. The rmOPN was dosed at 1, 5, and 10 μg/ml in H‐2kb‐tsA58 WT, conditionally immortalized myoblasts, and 10 μg/ml in myotubes. All mRNA and protein experiments were performed with 4–6 replicates. MSTN protein (PR) levels (pg/ml) were measured by enzyme‐linked immunoassay and normalized to total protein levels. Control (1× PBS) samples are shown in the far left column for panels (B)–(D) (*P ≤ 0.05; ***P ≤ 0.001). (A) rmOPN decreased endogenous MSTN mRNA in myoblasts in a dose‐dependent fashion at 24 hours. (B) rmOPN decreased MSTN protein in a dose‐dependent fashion in myoblasts at 48 hours. (C) rmOPN decreased MSTN protein in a dose‐dependent fashion in myoblasts at 48 hours. (D) rmOPN decreased MSTN protein in myotubes at 24 hours.

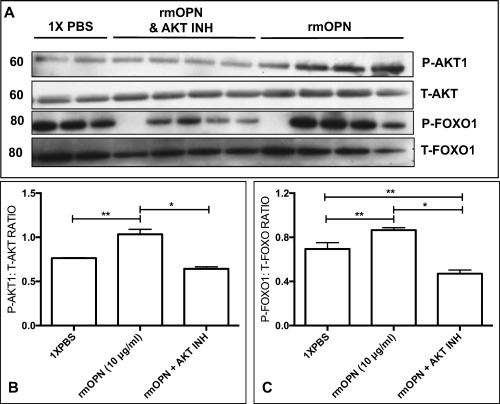

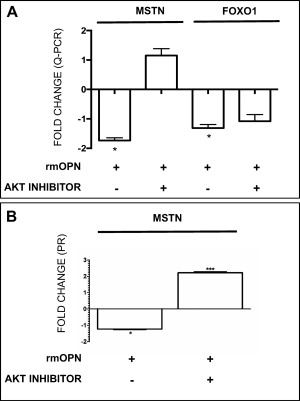

Consistent with activation of the AKT1 pathway,2, 3, 4 rmOPN‐treated cells had increased phosphorylated AKT1 (serine 473) levels after 24 hours of treatment (Fig. 3A and B). Exposure of H‐2kb‐tsA58 myoblasts to an AKT kinase inhibitor (#124005) blocked both rmOPN‐mediated AKT1 phosphorylation (Fig. 3A and B) and downregulation of MSTN at the mRNA and protein level (Fig. 4A and B).

Figure 3.

Recombinant mouse (rm)OPN treatment of H‐2kb‐tsA58 WT myoblasts led to phosphorylation of AKT1 and FoxO1. AKT1 and FoxO1 levels were measured by Western blot and quantified by densitometry. Phosphorylated AKT1 and FoxO1 were normalized to total AKT and FoxO1 levels, respectively. The numbers to the left of the blots indicate molecular weight in kilodaltons (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). T = total; P = phosphorylated. (A) AKT1 phosphorylation was induced in rmOPN‐treated (10 μg/ml) myogenic cells after 24 hours of incubation compared with control (1× PBS). The AKT inhibitor #124005 blocked this effect. FoxO1 phosphorylation was also greater in rmOPN‐treated cells compared with control, and AKT inhibitor also blocked this effect. Duplicate to quadruplicates were completed, as shown in each blot. Please note that all samples on each lane were run on the same gel. (B, C) Phosphorylated levels of AKT1 and FoxO1 were increased in rmOPN‐treated cells, whereas treatment with the AKT inhibitor decreased these levels to below control values.

Figure 4.

MSTN and FoxO1 decreased with rmOPN treatment and this effect was rescued by an AKT inhibitor. (A) MSTN and FoxO1 mRNA were decreased in H‐2kb‐tsA58 WT, conditionally immortalized myoblasts after rmOPN treatment (10 μg/ml). Addition of AKT inhibitor #124005 rescued MSTN [fold‐change (FC) = +1.17] and FoxO1 (FC = +1.452) mRNA expression. (B) MSTN protein decreased after rmOPN treatment and was rescued with AKT inhibitor (FC = +1.4) in myoblasts.

Recombinant Mouse OPN‐Treated Cells Showed FoxO1 Phosphorylation and miRNA‐486 Expression

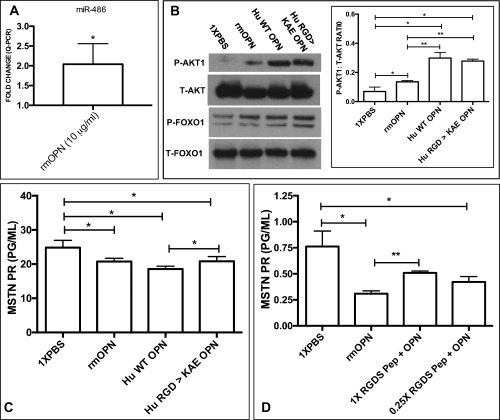

Addition of rmOPN to myoblast cultures increased FoxO1 phosphorylation at serine 256 (when normalized to total FoxO1) compared with control (Fig. 3A and C). This effect was blocked by AKT inhibitor #124005 (Fig. 3A and C). Intriguingly, levels of FoxO1 mRNA and protein were decreased by a fold change of –1.3 in rmOPN‐treated myogenic cultures and restored by AKT inhibitor #124005 (Fig. 4A). After treating myoblasts with rmOPN, we observed a 2‐fold increase in miRNA‐486, a known regulator of FoxO1 and the AKT1/MSTN pathway (Fig. 5A).42, 43

Figure 5.

AKT1 is activated by OPN through RGD‐ and non–RGD‐dependent receptors. Hu‐WT OPN (normal RGD sequence) and Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN (lacking the ITG‐binding RGD sequence) were tested in H‐2kb‐tsA58 WT myoblasts. (A) miR‐486 was increased in rmOPN‐treated myoblasts (FC = +2.07; P < 0.05) (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01). (B) rmOPN, Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN, and Hu‐WT OPN increased AKT phosphorylation compared with 1× PBS control, with the latter showing the greatest effect (P < 0.05). Both human OPN proteins showed greater AKT1 phosphorylation abilities compared with rmOPN (P < 0.01). All OPN proteins increased FoxO1 phosphorylation. (C) Hu‐WT OPN, Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN, and rmOPN all decreased MSTN compared with 1× PBS control (P < 0.05). Hu‐WT OPN decreased MSTN protein slightly further compared with Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN (P < 0.05). (D) rmOPN decreased MSTN protein compared with 1× PBS (P < 0.05). This effect was partially blocked when rmOPN was co‐treated with an RGDS amino acid blocking peptide [0.05 (0.25×) and 0.2 mg/ml (1×)] compared with rmOPN alone, but was not dose‐dependent (P < 0.01).

OPN‐Induced Reduction of MSTN Occurred through Both RGD and Non‐RGD Receptors

Myoblasts were treated with a human recombinant OPN protein with the ITG‐binding RGD sequence mutated to KAE (RGD→KAE), which partially blocked both the effects on AKT1 phosphorylation (Fig. 5B) and reduced MSTN protein (Fig. 5C). Treatment of myoblasts with Hu‐WT OPN (normal RGD sequence) resulted in more profound AKT1 phosphorylation and decreased MSTN protein expression compared with Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN and rmOPN (Fig. 5B and C). These results were further supported by pretreating myotubes with an RGDS blocking peptide to prevent rmOPN from binding to the RGD amino acid sequence on ITGs. The RGDS blocking peptide partially ablated the effects of rmOPN on MSTN protein expression, similar to the Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN experiments, but it was not dose‐dependent (Fig. 5D).

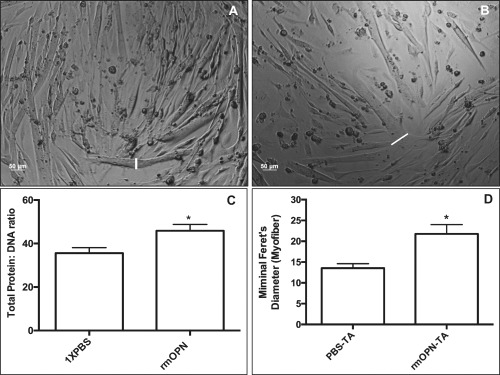

Recombinant Mouse OPN Treatment Led to Myotube and Myofiber Hypertrophy

We found an increase in myotube hypertrophy in several myotubes in rmOPN‐treated cells compared with PBS control‐treated cells (Fig. 6A and B). Total protein content, normalized to total DNA content, was increased after similarly treating myotubes with rmOPN for 48 hours; there was no difference in total DNA content between control and rmOPN‐treated myotubes (Fig. 6C). To test our hypothesis in vivo, 3‐week‐old female mdx mice were co‐injected intramuscularly into the TA muscle with rmOPN and a green dye cocktail, which led to an increase in minimal Feret myofiber diameter 1 week later (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Myotubes and muscle treated with rmOPN displayed hypertrophy. Myotubes were treated with rmOPN for 24–48 hours and subsequently evaluated on day 5 of differentiation. A 10‐μg/ml dose for rmOPN optimal and was used for each experiment. (A) Myotubes were treated with 1× PBS to serve as a control. (B) Several of the H‐2kb‐tsA58 WT myotubes exhibited increased cell diameter (white lines) compared with 1× PBS. (C) Treatment of myotubes with rmOPN increased total protein content by 26.6% after normalizing to total DNA content compared with control (P < 0.05). All experiments were performed in sextuplicates. (D) There was increased minimal Feret diameter in rmOPN‐injected tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of 4‐week‐old mdx mice compared with contralateral saline‐injected TA muscles. Mice were injected at 3 weeks of age (1‐week treatment duration). The minimal Feret diameter was measured only for myofibers with green dye immediately adjacent to the myofiber membrane. N = 4 limbs per group.

DISCUSSION

In addition to its well‐established roles in cancer progression and inflammatory states, OPN has been increasingly associated with muscle development and remodeling. A single‐nucleotide polymorphism in the OPN promoter region tracked with differential muscle size in healthy women, whereas OPN knockout mice had smaller TA muscles.44 We previously showed that OPN polymorphisms were associated with muscle size in healthy women13 and hypothesized that MSTN, a well‐known negative regulator of muscle mass,45, 46 may share a molecular network with OPN. Similarly, we showed that CS muscle in dystrophin‐deficient dogs had marked hypertrophy by 6 months of age, with sizes up to 300% of that in normal dogs.32 After finding a strong inverse correlation between OPN and MSTN in GRMD CS muscle, we hypothesized that OPN could indeed modify the MSTN muscle growth pathway. Surprisingly, we found that OPN levels were inversely correlated with GRMD CS muscle size by 6 months of age. We hypothesize that OPN exerted its downstream effects on MSTN at 4–9 weeks of age in GRMD dogs, leading to muscle hypertrophy by 6 months of age, with a concomitant reduction of OPN at the same time. Because OPN was inversely correlated with CS muscle size at 6 months, it was no surprise to see OPN track with other functional outcome measures, such as TTJ angle and muscle strength, in the GRMD dogs, as seen in other studies.13, 17, 34

We further postulated that OPN could reduce MSTN expression, which was tested in vitro. H‐2kb‐tsA58 WT cells were treated with recombinant OPN proteins, and signaling pathways through ITGs/CD44, AKT1, FoxO1, and MSTN were assessed. We observed AKT1 phosphorylation (serine 473) in OPN‐treated cells and a decrease in endogenous MSTN mRNA and protein. Therefore, it was no surprise to observe decreased AKT1 phosphorylation and restored MSTN mRNA and protein after co‐treating cells with rmOPN and an AKT inhibitor. It should be noted that Morissette et al. found that MSTN regulated AKT1‐mediated hypertrophy in myotubes.47 In our study, we showed that AKT1 could indeed regulate MSTN expression, suggesting a potential feedback mechanism between MSTN and AKT1.

Humans (SVVYGLR) and mice (SLAYGR) share common OPN‐binding sites in ITG and CD44 receptors.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 To determine the relative roles these receptors play in muscle, we treated the murine H‐2kb‐tsA58 WT myoblasts with Hu‐WT OPN (normal RGD sequence, binding to both ITG‐dependent and non‐ITG receptors) and also a mutant Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN (mutated RGD, binding to non–ITG‐dependent receptors such as CD44). Interestingly, the Hu‐WT OPN protein produced more profound AKT1 phosphorylation when compared with rmOPN treatment and Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN. MSTN protein was similarly downregulated, in keeping with continued signaling through AKT1 via ITG and non‐ITG receptors. We saw a comparable pattern with the mutant RGD→KAE OPN protein (AKT1 phosphorylation and reduced MSTN), but less intense compared with Hu‐WT OPN, suggesting that OPN, at the very least, binds non–RGD‐dependent ITGs α4β1, α4β7, and α9β1 (and possibly non–RGD‐dependent CD44). However, the significant further increase in AKT1 phosphorylation and decrease in MSTN protein levels after Hu‐WT OPN treatment compared with Hu‐RGD→KAE OPN suggests that RGD‐dependent ITGs (e.g., αvβ1, αvβ3, and α5β1) also may play a role. Our findings are reinforced by RGDS blocking peptide experiments in which MSTN protein was not as decreased when compared with rmOPN treatment alone.

Collectively, these data suggest that OPN treatment may signal through RGD‐ and non–RGD‐dependent receptors, resulting in decrease MSTN. The use of human OPN not only helped determine whether RGD‐dependent ITGs are involved, but also whether non‐RGD receptors, such as CD44 or α4β1, α4β7, and α9β1, contribute. One concern relates to whether bioactive growth factors made by the myeloma cell line during the generation of the rmOPN protein (R&D Systems) could confound our results. However, a reduction of MSTN expression was confirmed by the use of our Hu‐WT and RGD→KAE OPN proteins generated in human marrow stromal fibroblasts. Future experiments beyond the scope of this study will be required to fully delineate the OPN–ITG binding partners.

Earlier studies have revealed that FoxO1 is a transcriptional regulator of MSTN, binding its promoter region to activate transcription.48 AKT1‐mediated phosphorylation prevented FoxO1 translocation to the nucleus, thereby interfering with its transcriptional functions.49 We hypothesized that OPN treatment could therefore lead to both AKT1 and FoxO1 phosphorylation with a parallel decrease in MSTN expression. We indeed observed reduced endogenous FoxO1 and increased FoxO1 phosphorylation, with an associated decrease in MSTN mRNA and protein in rmOPN‐treated cells. Addition of the AKT inhibitor #124005 to the rmOPN‐treated myoblasts appeared to rescue FoxO1 mRNA and decrease FoxO1 phosphorylation, restoring and even increasing MSTN mRNA and protein. This suggests that OPN, AKT1, FoxO1, and MSTN may share a signaling pathway in skeletal muscle cells.

As mentioned previously, we also observed a decrease in FoxO1 mRNA after rmOPN treatment of the myoblasts and hypothesized that miRNAs targeting the mRNA were being upregulated by rmOPN treatment. Consistent with this hypothesis, miR‐486, which has previously been shown to decrease FoxO1 levels and regulate the MSTN/AKT pathway,42, 43 was increased 2‐fold in our rmOPN‐treated myoblasts. Therefore, in addition to activating the AKT pathway, OPN also appears to be associated with downstream miRs to modulate FoxO1.

After defining the molecular pathways involved, a functional relationship of OPN treatment was demonstrated with myotube hypertrophy and increased total protein content. OPN treatment was previously shown to increase myoblast proliferation, but reduce fusion.27 On the other hand, MSTN was observed to regulate myoblast proliferation in separate studies.47, 48 Although we did not measure myoblast proliferation in the current study, we can infer that a reduction in MSTN expression may result in myoblast proliferation via OPN treatment, leading to myotube hypertrophy. Nevertheless, we observed increased minimal Feret diameter in OPN‐injected mdx muscle. We hypothesized that the 3‐week age group, an age with profound degeneration and regeneration within mdx skeletal muscle, would have regenerating myofibers expressing more ITG and non–ITG‐dependent receptors compared with a later age. Therefore, OPN could more efficiently exert its downstream effects, leading to myofiber hypertrophy. Potential drawbacks were the use of female mdx mice, as males are predominantly affected in DMD, but also possible hormonal influences on OPN expression,15, 16 and the lack of a blinded observer to measure minimal Feret diameter.

In a previous study we disclosed that the degree of GRMD CS muscle hypertrophy correlates directly with AKT1 phosphorylation and inversely with MSTN levels at 6 months of age.34 Data from the previous study were substantiated by our in‐vitro OPN–AKT1–MSTN pathway and in‐vivo mdx studies results reported here. These collective data suggest that the AKT1 pathway is a specific modifier of muscle size in the GRMD CS and, potentially, other GRMD and DMD muscles that undergo hypertrophy.

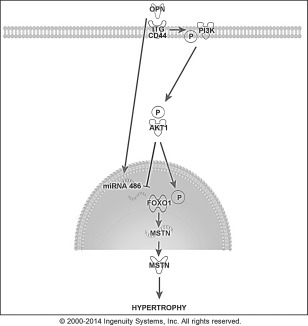

We propose a potential pathway where OPN can decrease MSTN expression through AKT1/FoxO1 signaling, with subsequent myotube and myofiber hypertrophy (Fig. 7). This model could account for OPN's modulation of muscle size13 and hypertrophy of dystrophin‐deficient muscle.34

Figure 7.

Schematic showing proposed pathway whereby OPN may interact with hypertrophy‐related proteins in muscle cells to induce hypertrophy. FoxO1 is a transcriptional regulator of MSTN, binding its promoter region to activate transcription. FoxO1 phosphorylation by AKT1 prevents translocation to the nucleus, thereby interfering with its transcriptional functions, including activation of MSTN. OPN also increased miR‐486, which could modulate FoxO1 mRNA and protein levels. We hypothesized that OPN binds integrins (ITG) and/or CD44 to activate AKT1, downregulate FoxO1, increase FoxO1 protein phosphorylation, and decrease MSTN mRNA and protein expression, resulting in myotube and myofiber hypertrophy.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information can be found in the online version of this article.

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Alyson Fiorillo and Dr. Chris Heier for their discussions; Dr. Sree Rayavarapu, Dr. Kanneyboyina Nagaraju, and Dr. Zuyi Wang for their technical assistance; Dr. Larry Fisher for contributing human recombinant osteopontin proteins; and Dan and Janet Bogan and Jennifer Dow for animal care and data collection. This work was presented in part at the 2012 FASEB Osteopontin Biology Meeting in Saxtons River, Vermont.

This study was supported by grants from the National Research Service (F32 Grant 1F32AR060703‐01 to P.P.N.), the National Institutes of Health (R01NS029525 to E.P.H.), and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (to E.P.H.).

REFERENCES

- 1. Scatena M, Liaw L, Giachelli CM. Osteopontin: a multifunctional molecule regulating chronic inflammation and vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007;27:2302–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liaw L, Almeida M, Hart CE, Schwartz SM, Giachelli CM. Osteopontin promotes vascular cell adhesion and spreading and is chemotactic for smooth muscle cells in vitro. Circ Res 1994;74:214–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Urtasun R, Lopategi A, George J, Leung TM, Lu Y, Wang X, et al Osteopontin, an oxidant stress sensitive cytokine, up‐regulates collagen‐I via integrin α(V)β(3) engagement and PI3K/pAkt/NFκB signaling. Hepatology 2012;55:594–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zheng DQ, Woodard AS, Tallini G, Languino LR. Substrate specificity of alpha(v)beta(3) integrin‐mediated cell migration and phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase/AKT pathway activation. J Biol Chem 2000;275:24565–24574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Von Marschall Z, Fisher LW. Dentin matrix protein‐1 isoforms promote differential cell attachment and migration. J Biol Chem 2008;283:32730–32740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yokosaki Y, Matsuura N, Sasaki T, Murakami I, Schneider H, Higashiyama S, et al The integrin alpha(9)beta(1) binds to a novel recognition sequence (SVVYGLR) in the thrombin‐cleaved amino‐terminal fragment of osteopontin. J Biol Chem 1999;274:36328–36334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yamamoto N, Sakai F, Kon S, Morimoto J, Kimura C, Yamazaki H, et al Essential role of the cryptic epitope SLAYGLR within osteopontin in a murine model of rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest 2003;112:181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin YH, Yang‐Yen HF. The osteopontin‐CD44 survival signal involves activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase/Akt signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 2001;276:46024–46030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Konno S, Kurokawa M, Uede T, Nishimura M, Huang SK. Role of osteopontin, a multifunctional protein, in allergy and asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2011;41:1360–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weber GF. The cancer biomarker osteopontin: combination with other markers. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 2011;8:263–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McKee MD, Pedraza CE, Kaartinen MT. Osteopontin and wound healing in bone. Cells Tissues Organs 2011;194:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reinholt FP, Hultenby K, Oldberg A, Heinegard D. Osteopontin—a possible anchor of osteoclasts to bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1990;87:4473–4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoffman EP, Gordish‐Dressman H, McLane VD, Devaney JM, Thompson PD, Visich P, et al Alterations in osteopontin modify muscle size in females in both humans and mice. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2013;45:1060–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boudjadi S, Bernatchez G, Beaulieu JF, Carrier JC. Control of the human osteopontin promoter by ERRα in colorectal cancer. Am J Pathol 2013;183:266–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xie QZ, Qi QR, Chen YX, Xu WM, Liu Q, Yang J. Uterine micro‐environment and estrogen‐dependent regulation of osteopontin expression in mouse blastocyst. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:14504–14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zirngibl RA, Chan JS, Aubin JE. Divergent regulation of the osteopontin promoter by the estrogen receptor‐related receptors is isoform‐ and cell context dependent. J Cell Biochem 2013;114:2356–2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Many GM, Yokosaki Y, Uaesoontrachoon K, Nghiem PP, Bello L, Dadgar S, et al OPN‐a induces muscle inflammation by increasing recruitment and activation of pro‐inflammatory macrophages. Exp Physiol 2016;101:1285–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pegoraro E, Hoffman EP, Piva L, Gavassini BF, Cagnin S, Ermani M, et al SPP1 genotype is a determinant of disease severity in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2011;76:219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bello L, Piva L, Barp A, Taglia A, Picillo E, Vasco G, et al Importance of SPP1 genotype as a covariate in clinical trials in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2012;79:159–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen YW, Zhao P, Borup R, Hoffman EP. Expression profiling in the muscular dystrophies: identification of novel aspects of molecular pathophysiology. J Cell Biol 2000;151:1321–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zanotti S, Gibertini S, Di Blasi C, Cappelletti C, Bernasconi P, Mantegazza R, Morandi L, et al Osteopontin is highly expressed in severely dystrophic muscle and seems to play a role in muscle regeneration and fibrosis. Histopathology 2011;59:1215‐1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vetrone SA, Montecino‐Rodriguez E, Kudryashova E, Kramerova I, Hoffman EP, et al Osteopontin promotes fibrosis in dystrophic mouse muscle by modulating immune cell subsets and intramuscular TGF‐beta. J Clin Invest 2009;119:1583–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Capote J, Kramerova I, Martinez L, Vetrone S, Barton ER, Sweeney HL, et al Osteopontin ablation ameliorates muscular dystrophy by shifting macrophages to a pro‐regenerative phenotype. J Cell Biol 2016; 25;213:275–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Galindo CL, Soslow JH, Brinkmeyer‐Langford CL, Gupte M, Smith HM, Sengsayadeth S, et al Translating golden retriever muscular dystrophy microarray findings to novel biomarkers for cardiac/skeletal muscle function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Res 2016;79:629–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kuraoka M, Kimura E, Nagata T, Okada T, Aoki Y, Tachimori H, et al Serum osteopontin as a novel biomarker for muscle regeneration in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am J Pathol 2016;186:1302–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Qureshi MM, McClure WC, Arevalo NL, Rabon RE, Mohr B, Bose SK, et al The dietary supplement protandim decreases plasma osteopontin and improves markers of oxidative stress in muscular dystrophy mdx mice. J Diet Suppl 2010;7:159–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Uaesoontrachoon K, Yoo HJ, Tudor EM, Pike RN, Mackie EJ, Pagel CN. Osteopontin and skeletal muscle myoblasts: association with muscle regeneration and regulation of myoblast function in vitro. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2008;40:2303–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Valentine BA, Cooper BJ, de Lahunta A, O'Quinn R, Blue JT. Canine X‐linked muscular dystrophy. An animal model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: clinical studies. J Neurol Sci 1988; 88:69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kornegay JN, Sharp NJ, Schueler RO, Betts CW. Tarsal joint contracture in dogs with golden retriever muscular dystrophy. Lab Anim Sci 1994;44:331–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kornegay JN, Bogan DJ, Bogan JR, Childers MK, Cundiff DD, Petroski GF, et al Contraction force generated by tarsal joint flexion and extension in dogs with golden retriever muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Sci 1999;166:115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu JM, Okamura CS, Bogan DJ, Bogan JR, Childers MK, Kornegay JN. Effects of prednisone in canine muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 2004;30:767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kornegay JN, Cundiff DD, Bogan DJ, Bogan JR, Okamura CS. The cranial sartorius muscle undergoes true hypertrophy in dogs with golden retriever muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord 2003;13:493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kornegay JN, Bogan JR, Bogan DJ, Childers MK, Grange RW. Golden retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD): developing and maintaining a colony and physiological functional measurements. Methods Mol Biol 2011;709:105–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nghiem PP, Hoffman EP, Mittal P, Brown KJ, Schatzberg SJ, Ghimbovschi S, et al Sparing of the dystrophin‐deficient cranial sartorius muscle is associated with classical and novel hypertrophy pathways in GRMD dogs. Am J Pathol 2013;183:1411–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhao P, Iezzi S, Carver E, Dressman D, Gridley T, Sartorelli V, Hoffman EP. Slug is a novel downstream target of MyoD. Temporal profiling in muscle regeneration. J Biol Chem 2002;16;277:30091–30101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao P, Caretti G, Mitchell S, McKeehan WL, Boskey AL, Pachman LM, et al Fgfr4 is required for effective muscle regeneration in vivo. Delineation of a MyoD‐Tead2‐Fgfr4 transcriptional pathway. J Biol Chem 2006;281:429‐438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jat PS, Noble MD, Ataliotis P, Tanaka Y, Yannoutsos N, Larsen L, et al Direct derivation of conditionally immortal cell lines from an H‐2Kb‐tsA58 transgenic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991;88:5096–5100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morgan JE, Beauchamp JR, Pagel CN, Peckham M, Ataliotis P, Jat PS, et al Myogenic cell lines derived from transgenic mice carrying a thermolabile T antigen: a model system for the derivation of tissue‐specific and mutation‐specific cell lines. Dev Biol 1994;162:486–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Teramoto H, Castellone MD, Malek RL, Letwin N, Frank B, Gutkind JS, et al Autocrine activation of an osteopontin‐CD44‐Rac pathway enhances invasion and transformation by H‐RasV12. Oncogene 2005;24:489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Young MF, Kerr JM, Termine JD, Wewer UM, Wang MG, McBride OW, et al CDNA cloning, mRNA distribution and heterogeneity, chromosomal location, and RFLP analysis of human osteopontin (OPN). Genomics 1990;7:491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fedarko NS, Fohr B, Robey PG, Young MF, Fisher LW. Factor H binding to bone sialoprotein and osteopontin enables tumor cell evasion of complement‐mediated attack. J Biol Chem 2000;275:16666–16672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xu J, Li R, Workeneh B, Dong Y, Wang X, Hu Z. Transcription factor FoxO1, the dominant mediator of muscle wasting in chronic kidney disease, is inhibited by microRNA‐486. Kidney Int 2012;82:401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hitachi K, Nakatani M, Tsuchida K. Myostatin signaling regulates Akt activity via the regulation of miR‐486 expression. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2014;47:93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pagel CN, Wasgewatte Wijesinghe DK, Taghavi Esfandouni N, Mackie EJ. Osteopontin, inflammation and myogenesis: influencing regeneration, fibrosis and size of skeletal muscle. J Cell Commun Signal 2014;8:95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF‐beta superfamily member. Nature 1997;387:83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee SJ. Regulation of muscle mass by myostatin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2004;20:61–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Morissette MR, Cook SA, Buranasombati C, Rosenberg MA, Rosenzweig A. Myostatin inhibits IGF‐I‐induced myotube hypertrophy through Akt. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2009;297:C1124–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Allen DL, Unterman TG. Regulation of myostatin expression and myoblast differentiation by FoxO and SMAD transcription factors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007;292:C188–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, et al Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell 1999;96:857–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional supporting information can be found in the online version of this article.

Supporting Information