Abstract

Little empirical work has evaluated why anxious cannabis users are especially vulnerable to poorer cannabis cessation outcomes. Presumably, these individuals rely on cannabis because they have difficulties with emotion regulation and they therefore use cannabis to manage their negative emotions. The current study examined the direct and indirect effects of anxiety severity on a range of cannabis cessation variables among 79 (63.3% non-Hispanic White; 43.0% female) adults with anxiety disorders seeking outpatient treatment for cannabis use disorder. The independent and serial indirect effects of difficulties with emotion regulation and coping motives were examined in relation to the anxiety-cannabis variables. Anxiety severity was directly and robustly related to greater cannabis withdrawal symptom severity, less self-efficacy to refrain from using cannabis in emotionally distressing situations, and more reasons for quitting. Anxiety was indirectly related to cannabis outcomes via the serial effects of emotion regulation and coping motives. These findings document the important role of emotion regulation and coping motives in the relations of anxiety with cannabis cessation variables among dually diagnosed outpatients.

Keywords: cannabis, marijuana, difficulties with emotion regulation, coping motives, dual diagnosis

Anxiety and its disorders are highly related to cannabis use disorder (CUD). To illustrate, up to 50% of people with CUD have an anxiety disorder and those with CUD are nearly six times more likely to experience a co-occurring anxiety disorder compared with those without CUD (Stinson, Ruan, Pickering, & Grant, 2006). In fact, anxiety disorders may be a risk factor for CUD -- anxiety disorders tend to onset before cannabis dependence in the vast majority of dually diagnosed individuals (Agosti, Nunes, & Levin, 2002) and prospective work indicates that anxiety and anxiety disorders tend to onset prior to cannabis problems, including CUD (Buckner et al., 2008; Marmorstein, White, Loeber, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2010). This co-occurrence has important clinical implications. For example, greater anxiety symptoms at treatment termination predicts greater post-treatment cannabis use and use-related problems (Bonn-Miller & Moos, 2009; Buckner & Carroll, 2010). Thus, identification of factors that play a role in cannabis-related problems among anxious patients could inform treatment and prevention efforts.

One such vulnerability factor that may be especially relevant is difficulties with emotion regulation. Accumulating evidence supports that severity of anxiety symptoms is related to difficulties with emotion regulation (e.g., Amstadter, 2008; Cisler, Olatunji, Feldner, & Forsyth, 2010; Gonzalez, Zvolensky, Vujanovic, Leyro, & Marshall, 2008; Hofmann, Sawyer, Fang, & Asnaani, 2012; Mennin, Heimberg, Turk, & Fresco, 2005). In line with negative reinforcement models of drug use (e.g., Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004), anxiety may be related to cessation problems because anxious persons have greater difficulty regulating emotion and thus rely on cannabis to cope; that is, the indirect effects of difficulties with emotion regulation and coping motives serially impact cannabis processes. Difficulties with emotion regulation are related to but distinct from cannabis coping motives (e.g., Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, Boden, & Gross, 2011; Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, & Zvolensky, 2008). Extant data suggest that anxiety severity may be related to cannabis use variables indirectly via the serial effects of difficulties with emotion regulation and coping motives: (1) severity of symptomatology of various anxiety conditions is related to coping motivated cannabis use (e.g., Buckner, Bonn-Miller, Zvolensky, & Schmidt, 2007; Johnson, Bonn-Miller, Leyro, & Zvolensky, 2009; Zvolensky et al., 2009); (2) some types of anxiety are indirectly related to coping motives via difficulties with emotion regulation (Bonn-Miller et al., 2011); and (3) severity of anxiety symptoms is indirectly related to cannabis use and related problems via coping motives (e.g., Buckner et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2009; Zvolensky et al., 2009).

In a sample of adults with both CUD and anxiety disorders seeking outpatient psychotherapy for CUD and anxiety, the current study tested the hypothesis that anxiety symptom severity would be related to a variety of cannabis cessation variables (withdrawal symptoms during most recent quit attempt, self-efficacy to abstain from cannabis, reasons for quitting) indirectly via the serial effects of difficulties with emotion regulation and then coping motivated cannabis use. Specifically, it was hypothesized that anxiety severity would be positively related to withdrawal and reasons to quit and negatively related to self-efficacy to quit. These cannabis cessation variables were chosen given that withdrawal symptoms and self-efficacy to abstain are related to cannabis cessation outcomes (Buckner et al., 2015; Chung, Martin, Cornelius, & Clark, 2008; Stephens, Wertz, & Roffman, 1995) and that more reasons for quitting are negatively related to substance use (Foster, Schmidt, & Zvolensky, 2015).

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants (n=79) were adults seeking treatment to reduce or cease cannabis use (Mage=24.0, SD=7.9, range=18–56; 43.0% female) who were recruited from the community (via flyers, newspaper ads, online advertisements) to participate in a randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of two psychosocial interventions for CUD (clinicaltrails.gov #NCT01875796). Inclusion criteria included being 18–65 years of age, meeting DSM-5 criteria for CUD and an anxiety disorder, having used marijuana in the past week to manage anxiety, marijuana being the drug of choice to manage anxiety, endorsing motivation to quit smoking marijuana, being interested in treatment to manage anxiety, and being willing to complete 12 weekly treatment sessions and follow-up assessments for up to 6 months following treatment. Exclusion criteria included currently receiving psychological or substance use treatment, being mandated to receive treatment, and currently being pregnant or interested in becoming pregnant during the study timeframe. The current study is based on secondary analyses of pre-treatment data.

The racial/ethnic composition of the current sample was non-Hispanic White (63.3%), Hispanic White (6.3%), non-Hispanic African American (21.5%), Asian/Asian American (1.3%), multiracial (3.8%), and other (3.8%). Regarding highest educational level attained, 1.3% reported less than high school, 13.9% had a high school diploma, 64.6% completed some college, 5.1% had a technical degree, and 15.2% had a 4 years bachelor’s degree. In terms of relationship status, 79.7% were single, 7.6% were cohabitating, 5.1% were divorced, 3.8% stated “other”, 2.5% were married, and 1.3% were separated. Age of first cannabis use was on average 16.1 years old (SD = 3.1). In the month prior to their appointment, participants used cannabis a mean of 22.0 (SD = 8.7) days, an average of 3.0 (SD = 2.3) joints per cannabis use day. The most common primary methods of use were bowls (34.6%), joints (46.2%), bongs (3.8%), and “other” (usually preferring more than one method; 15.4%). The majority reported at least one previous cannabis quit attempt (78.5%), with an average of 3.6 (SD=13.5) previous attempts. However, only 9.4% endorsed a history of treatment for drug use whereas 42.2% endorsed a history of treatment for anxiety. Primary DSM-5 diagnoses were as follows: CUD (44.3%), social anxiety disorder (32.9%), generalized anxiety disorder (13.9%), panic disorder (3.8%), other specified anxiety disorder (2.5%), and other (2.6%; e.g., agoraphobia).

Participants provided informed consent prior to participation and the study protocol was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. Participants underwent a clinical interview and completed a computerized battery of self-report questionnaires.

Measures

The Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (SIGH-A) (Hamilton, 1959) was used to assess anxiety symptom severity. This measure was developed to assess anxiety in clinical populations and it demonstrates high inter-rater and test-retest reliability (Shear et al., 2001). The SIGH-A was administered at screening and again at baseline by two independent doctoral students in clinical psychology (the baseline rater was blind to prior ratings). Baseline ratings were conducted on average 12.6 (SD = 11.13) days after screening. Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC = .81, 95% CI: .69–.88) was excellent. The scale also demonstrated good internal consistency at baseline (α=.87).

The Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) is a 36-item assessment of emotion dysregulation. Items are rated from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). In the current investigation, the DERS total sum score was used as a global index of emotion dysregulation (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). Consistent with past work (Gratz & Roemer, 2004), the scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current sample (α=.93).

Coping motives for cannabis use were assessed with the coping scale of the Marijuana Motives Measure (Simons, Correia, Carey, & Borsari, 1998), a 5-item measure of the degree to which participants have smoked cannabis for coping (e.g., to forget my worries) reasons from 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always). The coping scale has demonstrated good construct validity (Zvolensky et al., 2007) and internal consistency in prior work (Chabrol, Ducongé, Casas, Roura, & Carey, 2005) and in the present sample (α = .85).

Marijuana Withdrawal Checklist (MWC; Budney, Novy, & Hughes, 1999) assessed 15 withdrawal symptoms during participants’ most recent period of abstinence from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severe) for participants who endorsed a prior cannabis quit attempt. This measure is sensitive to the effects of abstinence (Budney, Hughes, Moore, & Novy, 2001; Budney et al., 1999) and has demonstrated good internal consistency in prior work (Budney, Moore, Vandrey, & Hughes, 2003; Vandrey, Budney, Kamon, & Stanger, 2005) and in the current sample (α=.91).

Situational Self-Efficacy Scale (Stephens et al., 1995) measures of the degree to which one feels confident in their ability to not use cannabis across several high-risk cannabis use situations on a scale from 1(not at all confident) to 7 (extremely confident). The scale is comprised of two subscales (DeMarce, Stephens, & Roffman, 2005): self-efficacy for psychologically-distressing situations (PDSE) that includes seven items (e.g., feeling depressed or worried, feeling frustrated; current α=.90) and self-efficacy in non-distressing situations (NDSE) that includes eight items (e.g., feeling like celebrating, at a party where people were using; current α=.90). Means for each subscale were used.

The Reasons for Quitting Questionnaire (Steinberg et al., 2002) consisted of a list of 25 reasons to change their cannabis use (e.g., “To show myself that I can quit if I really want to”) and asked to select all the reasons that applied to them. Endorsed items were summed to create an index of total number of reasons. This measure evidenced good internal consistency in the current sample (α=.86).

The clinician-administered Timeline Follow Back (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) was used to assess frequency and quantity of cannabis use during the 30 days prior to the baseline appointment. The TLFB is a reliable and valid self-report measure of cannabis use (O’Farrell, Fals-Stewart, & Murphy, 2003; Robinson, Sobell, Sobell, & Leo, 2014).

Data Analytic Strategy

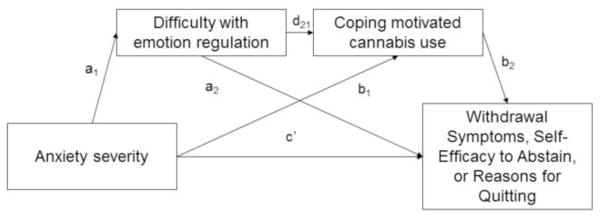

Analyses were conducted in SPSS 23 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). First, zero-order correlations among predictor (anxiety symptom severity), proposed mediators (DERS and MMQ-Coping, and criterion variables (MWC, situational self-efficacy scales, Reasons for quitting) were examined. Although anxiety severity tends to be unrelated to cannabis use frequency (Twomey, 2017), we tested whether anxiety symptom severity was correlated with cannabis use in the current sample to determine whether cannabis use should be included as a covariate in our model testing. Next, serial multiple mediator models were conducted to examine the impact of DERS and MMQ-Coping as mediators of the relation between anxiety severity and criterion outcomes. Separate models were conducted for each criterion. These conceptual path models are presented in Figure 1. Hayes (2013) describes this type of model as a serial multiple mediator model, in which the independent variable can affect the dependent variable through four pathways: directly and/or indirectly via difficulties with emotion regulation only, via coping motives only, and/or via both sequentially, with difficulties in emotion regulation affecting coping motives. Although mediational models are ideally tested using prospective data, cross-sectional tests of putative indirect effects is thought to be an important first step (Hayes, 2013). These analyses were conducted using PROCESS, a conditional process modeling program that utilizes an ordinary least squares-based path analytical framework to test for both direct and indirect effects (Hayes, 2013). All specific and conditional indirect effects were subjected to follow-up bootstrap analyses with 10,000 resamples from which a 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated (Hayes, 2009; Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008).

Figure 1.

Three separate models were conducted for each criterion variable to test the direct and indirect (via the serial effects of difficulties with emotion regulation and then coping motivated cannabis use) effects of anxiety symptom severity on cannabis outcome (withdrawal symptoms, self-efficacy to abstain in psychologically distressing situations, or reasons for quitting).

Results

Descriptive information and correlational results are presented in Table 1. Anxiety symptom severity was significantly correlated with greater withdrawal, less PDSE (but was unrelated to NDSE), and more reasons to quit. It was unrelated to cannabis use frequency. DERS and MMQ-Coping were significantly inter-correlated and were significantly related to criterion variables. Importantly, DERS and MMQ-coping remained significantly correlated after controlling for anxiety symptom severity (pr = .37, p = .001), suggesting that one affects the other, supporting the use of serial multiple mediator analyses (Hayes, 2013).

Table 1.

Descriptive data and intercorrelations among study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anxiety | - | |||||||

| 2. Difficulties with emotion regulation | .41** | - | ||||||

| 3. Coping motives | .28** | .44** | - | |||||

| 4. Cannabis withdrawal severity | .49** | .29* | .39** | - | ||||

| 5. Self-efficacy to abstain in psychologically distressing situations | −.39** | −.20 | −.43** | −.37** | - | |||

| 6. Self-efficacy to abstain in non-psychologically distressing situations | −.15 | −.14 | −.14 | −.07 | .65** | - | ||

| 7. Reasons for quitting | .25* | .22* | .31** | .37** | −.11 | −.09 | - | |

| 8. Cannabis use | .15 | .03 | .12 | .28* | −.31** | −.29** | −.07 | - |

|

| ||||||||

| M | 19.42 | 96.19 | 17.19 | 16.76 | 3.90 | 3.54 | 11.54 | 68.36 |

| (SD) | (8.56) | (22.42) | (5.18) | (9.66) | (1.48) | (1.47) | (5.07) | (72.34) |

Results for paths a, b, c, and c′ are presented in Table 2, which correspond to each of the three models. The estimates of the specific and conditional indirect effects are presented in Table 3. Each model is described below.

Table 2.

Regression results for three mediation models

| Criterion | Path | b | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis withdrawal severity | a1 | 1.165 | .295 | 3.95 | <.001 |

| a2 | .148 | .072 | 2.06 | .044 | |

| d21 | .079 | .028 | 2.81 | .007 | |

| b1 | .006 | .059 | .103 | .918 | |

| b2 | .435 | .254 | 1.71 | .092 | |

| c′ | .434 | .146 | 2.98 | .004 | |

| c | .546 | .127 | 4.30 | <.0001 | |

|

| |||||

| Self-efficacy to abstain in psychologically distressing situations | a1 | .1.077 | .279 | 3.85 | .<.001 |

| a2 | .075 | .069 | 1.10 | .277 | |

| d21 | .090 | .026 | 3.48 | .009 | |

| b1 | .007 | .008 | .875 | .385 | |

| b2 | −.110 | .032 | −3.00 | <.001 | |

| c′ | −.069 | .019 | −3.73 | <.001 | |

| c | −.057 | .019 | −3.00 | .003 | |

|

| |||||

| Reasons for quitting | a1 | 1.021 | .287 | 3.56 | <.001 |

| a2 | .085 | .069 | 1.24 | .220 | |

| d21 | .100 | .026 | 3.85 | <.001 | |

| b1 | .011 | .060 | .18 | .856 | |

| b2 | .684 | .250 | 2.73 | .007 | |

| c′ | .290 | .147 | 1.97 | .053 | |

| c | .429 | .142 | 3.03 | .003 | |

Table 3.

Bootstrap estimates of the standard errors and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the indirect effects

| Indirect Effects | b | SE | CI (lower) | CI (upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Marijuana Withdrawal Symptoms | ||||

| Anxiety → Difficulty with emotion regulation → Withdrawal | .007 | .074 | −.132 | .167 |

| Anxiety → Coping Motives → Withdrawal | .065 | .051 | .0003 | .214 |

| Anxiety → Difficulty with emotion regulation → Coping Motives → Withdrawal | .040 | .028 | .005 | .130 |

| Model 2: PDSE | ||||

| Anxiety → Difficulty with emotion regulation → PDSE | .007 | .008 | −.007 | .024 |

| Anxiety → Coping Motives → PDSE | −.008 | .009 | −.031 | .006 |

| Anxiety → Difficulty with emotion regulation → Coping Motives → PDSE | −.012 | .005 | −.025 | −.004 |

| Model 3: Reasons for quitting | ||||

| Anxiety → Difficulty with emotion regulation → Reasons | .011 | .060 | −.090 | .134 |

| Anxiety → Coping Motives → Reasons | .058 | .060 | −.028 | .218 |

| Anxiety → Difficulty with emotion regulation → Coping Motives → Reasons | .070 | .042 | .018 | .199 |

Note. PDSE = self-efficacy to abstain in psychologically-distressing situations. The 95% CI’s for indirect effects were obtained by bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples. → = affects.

Withdrawal Symptoms

Among the 62 participants who had made a prior quit attempt, the total effects model accounted for significant variance in withdrawal symptoms (R2 = .235, df = 1, 60, F = 18.452, p = .0001). The full model with DERS and MMQ-Coping predicted significant variance in withdrawal severity (R2 = .278, df = 3, 58, F = 7.460, p = .0003), and there was a significant direct effect of anxiety symptom severity on withdrawal severity after controlling for DERS and MMQ-Coping (see Table 2, Problems, path c′). The indirect effects were estimated (see Table 3, Model 1); greater anxiety symptom severity was indirectly related to more severe withdrawal symptoms through MMQ-Coping (but not DERS) and through the serial effect of DERS and MMQ-Coping.1

Psychologically Distressing Situations Self-Efficacy

The total effects model accounted for significant variance in PDSE (R2 = .155, df = 1, 76, F = 13.95, p = .0004). The full model with DERS and MMQ-Coping predicted significant variance in PDSE (R2 = .274, df = 3, 74, F = 9.30, p < .0001), and there was a significant direct effect of anxiety symptom severity on PDSE after controlling for DERS and MMQ-Coping (see Table 2, Problems, path c′). The indirect effects were estimated (see Table 3, Model 2); greater anxiety symptom severity was indirectly related to less PDSE only through the serial effect of both DERS and MMQ-Coping.

Reasons for Quitting

The total effects model accounted for significant variance in reasons for quitting (R2 = .335, df = 1, 73, F = 9.210, p = .0033). The full model with DERS and MMQ-Coping predicted significant variance in reasons for quitting (R2 = .217, df = 3, 71, F = 6.573, p = .0006), and there was a significant direct effect of anxiety symptom severity on reasons to quit after controlling for DERS and MMQ-Coping (see Table 2, Problems, path c′). The indirect effects were estimated (see Table 3, Model 3); greater anxiety symptom severity was indirectly related to more reasons to quit only through the serial effect of both DERS and MMQ-Coping.

Alternate Model Testing

Given the limitations of testing mediation using cross-sectional data, we tested whether anxiety symptom severity was related to cannabis outcomes via the serial effects of MMQ-Coping then DERS. This indirect effects were not significant for cannabis withdrawal, B = .002, SE = .025, 95% CI: −.047, .055, PDSE, B = .002, SE = .002, 95% CI: −.001, .110, or reasons for quitting, B = .004, SE = .019, 95% CI: −.030, .051.

Alternatively, it may be that difficulties with emotion regulation lead to more severe anxiety symptoms which could result in more coping-motived cannabis use, etc. However, anxiety symptom severity was no longer significantly correlated with MMQ-Coping after controlling for DERS (pr = .13, p = .277), thereby violating a key assumption of serial multiple mediator analyses (Hayes, 2013).

Discussion

The current study is the first known test of the serial effects of difficulties with emotion regulation and coping motives on anxiety symptom severity’s relation to an array of clinically relevant cannabis use constructs among dually diagnosed cannabis users seeking outpatient treatment. Anxiety symptom severity was associated with more severe withdrawal and more reasons for quitting. It was associated with less self-efficacy to refrain from cannabis use in psychologically distressing situations (but not other situations). In fact, anxiety symptom severity was robustly related to these clinically relevant variables even after controlling for difficulties with emotion regulation and coping motives. Importantly, anxiety was related to the cannabis cessation variables indirectly via the serial effects of difficulties with emotion regulation and coping motives, suggesting a possible explanatory pathway.

The current findings extend the extant literature in several key ways. First, the findings from the current study expand upon prior work by determining key variables (difficulties with emotion regulation, coping motivated cannabis use) that help explain the relationship between anxiety and cannabis cessation problems. Difficulties with emotion regulation have been implicated in anxiety disorders (Amstadter, 2008; Cisler et al., 2010; Hofmann et al., 2012) and coping-motivated cannabis use (Bonn-Miller et al., 2011; Hyman & Sinha, 2009). Although it has been posited that difficulties with emotion regulation lead to coping motivated use as a maladaptive attempt at emotion regulation (Bonn-Miller et al., 2011), the current study extended the literature by determining that difficulties with emotion regulation and coping motives work serially in the relations between anxiety symptom severity and cannabis cessation-related factors. Notably, although difficulties with emotion regulation were correlated with coping motives (Table 1), they share only 19.4% of the variance with one another, suggesting they are distinct constructs.

Findings have important clinical implications. Given that the data suggest that patients with more severe anxiety suffer from more problems with emotion regulation which may increase their reliance on cannabis to cope with negative affectivity (leading to greater cessation problems and withdrawal symptoms), clinicians may consider explicitly teaching these patients more adaptive ways to manage negative affect to reduce their reliance on cannabis. Both adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies have been found to change during cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (Aldao, Jazaieri, Goldin, & Gross, 2014; Blackledge & Hayes, 2001; Forkmann et al., 2014; Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Moscovitch et al., 2012). Importantly, targeting emotional regulation skills during psychotherapy leads to enhancement in emotion regulation skills (Berking, Meier, & Wupperman, 2010) and better treatment outcomes (Berking et al., 2008).

The present study has several limitations that can inform future work in this area. First, the study was limited to a cross-sectional design and temporal association of variables was not evaluated. Although attempts were made to evaluate alternative models, future work will need to evaluate whether anxiety severity increases difficulties with emotion regulation which increases coping-motivated use, increasing cessation problems -- or whether difficulties with emotion regulation increase anxiety severity which increases coping motivated use, etc. Further, given that anxiety is a symptom of cannabis withdrawal (Budney, Hughes, Moore, & Vandrey, 2004), future work is necessary to test whether withdrawal increases anxiety symptom severity, resulting in a positive feedback loop between anxiety and cannabis use. Second, participants were recruited for a CUD treatment trial. Given that most individuals with CUD do not seek treatment (Stinson et al., 2006), future work should test these models among cannabis users with anxiety disorders not seeking treatment to generalize to the results to a large group of persons. It also may be advisable to explore whether a similar explanatory model is applicable to cannabis users without anxiety disorders. Third, although the study benefited from a sample with good gender (43% female) and racial (63% non-Hispanic White) diversity, participants were younger than other CUD treatment samples and although they reported smoking approximately the same number of joints per day as prior samples, they used cannabis somewhat less frequently (e.g., Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group, 2004). This may reflect that the sample was required to also suffer from co-occurring anxiety and to note that they use cannabis to manage their anxiety. It may be that the co-occurrence of pathological anxiety prompts those with CUD to seek psychological services at a younger age. Additional research is necessary to determine whether results generalize to older patients and those that use cannabis more frequently.

In sum, findings indicate that patients with more severe anxiety symptoms suffer from difficulties with emotion regulation, which may be related to their reliance on cannabis to cope with negative mood disturbances. Such emotion-driven cannabis use may be further related to in an array of cannabis use processes.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided in part by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R34DA031937). NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Given that anxiety is a symptom of cannabis withdrawal, analyses were rerun with the anxiety item removed from the MWC. The total effects model accounted for significant variance in the remaining withdrawal symptoms (R2 = .230, df = 1, 60, F = 17.945, p = .0001). The full model with DERS and MMQ-Coping predicted significant variance (R2 = .284, df = 3, 58, F = 7.650, p = .0002), and there was a significant direct effect of anxiety severity on withdrawal severity after controlling for DERS and MMQ-Coping, B = .388, SE = .135, p = .006. Anxiety severity was indirectly related to withdrawal severity through MMQ-Coping, B = .067, SE = .050, 95% CI: .004, .210 (but not DERS, B = .004, SE = .068, 95% CI: −.127, .150), and the serial effect of DERS and MMQ-Coping, B = .042, SE = .027, 95% CI: .007, .130.

Portions of this manuscript were presented at the 2017 annual conference of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Contributor Information

Julia D. Buckner, Louisiana State University.

Katherine A. Walukevich, Louisiana State University

Michael J. Zvolensky, University of Houston and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Matthew W. Gallagher, University of Houston

References

- Agosti V, Nunes E, Levin F. Rates of psychiatric comorbidity among U.S. residents with lifetime cannabis dependence. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:643–652. doi: 10.1081/ADA-120015873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Jazaieri H, Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies: Interactive effects during CBT for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014;28:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.03.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter A. Emotion regulation and anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berking M, Meier C, Wupperman P. Enhancing Emotion-Regulation Skills in Police Officers: Results of a Pilot Controlled Study. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.001. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berking M, Wupperman P, Reichardt A, Pejic T, Dippel A, Znoj H. Emotion-regulation skills as a treatment target in psychotherapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:1230–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackledge JT, Hayes SC. Emotion regulation in acceptance and commitment therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;57:243–255. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200102)57:2<243::AID-JCLP9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Moos RH. Marijuana discontinuation, anxiety symptoms, and relapse to marijuana. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:782–785. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Boden MT, Gross JJ. Posttraumatic stress, difficulties in emotion regulation, and coping-oriented marijuana use. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2011;40:34–44. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2010.525253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ. Emotional dysregulation: Association with coping-oriented marijuana use motives among current marijuana users. Substance Use and Misuse. 2008;43:1653–1665. doi: 10.1080/10826080802241292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Marijuana use motives and social anxiety among marijuana-using young adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2238–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Carroll KM. Effect of anxiety on treatment presentation and outcome: Results from the Marijuana Treatment Project. Psychiatry Research. 2010;178:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Lang AR, Small JW, Schlauch RC, Lewinsohn PM. Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Ecker AH, Richter AA. Antecedents and consequences of cannabis use among racially diverse cannabis users: an analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;147:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Moore BA, Novy PL. Marijuana abstinence effects in marijuana smokers maintained in their home environment. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:917–924. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Hughes JR, Moore BA, Vandrey R. Review of the validity and significance of cannabis withdrawal syndrome. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1967–1977. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Moore BA, Vandrey RG, Hughes JR. The time course and significance of cannabis withdrawal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:393–402. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Novy PL, Hughes JR. Marijuana withdrawal among adults seeking treatment for marijuana dependence. Addiction. 1999;94:1311–1322. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrol H, Ducongé E, Casas C, Roura C, Carey KB. Relations between cannabis use and dependence, motives for cannabis use and anxious, depressive and borderline symptomatology. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:829–840. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Martin CS, Cornelius JR, Clark DB. Cannabis withdrawal predicts severity of cannabis involvement at 1-year follow-up among treated adolescents. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2008;103:787–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisler JM, Olatunji BO, Feldner MT, Forsyth JP. Emotion regulation and the anxiety disorders: An integrative review. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2010;32:68–82. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9161-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarce JM, Stephens RS, Roffman RA. Psychological distress and marijuana use before and after treatment: Testing cognitive-behavioral matching hypotheses. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1055–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forkmann T, Scherer A, Pawelzik M, Mainz V, Drueke B, Boecker M, Gauggel S. Does cognitive behavior therapy alter emotion regulation in inpatients with a depressive disorder? Psychology Research and Behavior Management. 2014;7:147–153. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S59421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DW, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ. Influences of barriers to cessation and reasons for quitting on substance use among treatment-seeking smokers who report heavy drinking. Journal Of Addiction Research & Therapy. 2015:6. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, Leyro TM, Marshall EC. An evaluation of anxiety sensitivity, emotional dysregulation, and negative affectivity among daily cigarette smokers: Relation to smoking motives and barriers to quitting. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;43:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. The British Journal Of Medical Psychology. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76:408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Fang A, Asnaani A. Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29:409–416. doi: 10.1002/da.21888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SM, Sinha R. Stress-related factors in cannabis use and misuse: Implications for prevention and treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:400–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA, Bonn-Miller MO, Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ. Anxious arousal and anhedonic depression symptoms and the frequency of current marijuana use: Testing the mediating role of marijuana-use coping motives among active users. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol And Drugs. 2009;70:543–550. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group. Brief treatments for cannabis dependence: Findings from a randomized multisite trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:455–466. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, White HR, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Anxiety as a predictor of age at first use of substances and progression to substance use problems among boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:211–224. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9360-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Fresco DM. Preliminary evidence for an emotion dysregulation model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1281–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch DA, Gavric DL, Senn JM, Santesso DL, Miskovic V, Schmidt LA, … Antony MM. Changes in Judgment Biases and Use of Emotion Regulation Strategies During Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder: Distinguishing Treatment Responders from Nonresponders. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012;36:261–271. doi: 10.1007/s10608-011-9371-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Fals-Stewart W, Murphy M. Concurrent validity of a brief self-report drug use frequency measure. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:327–337. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00226-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SM, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI. Reliability of the Timeline Followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:154–162. doi: 10.1037/a0030992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Vander Bilt J, Rucci P, Endicott J, Lydiard B, Otto MW, … Frank DM. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A) Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:166–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Correia CJ, Carey KB, Borsari BE. Validating a five-factor marijuana motives measure: Relations with use, problems, and alcohol motives. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1998;45:265–273. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Totowa, NJ US: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg KL, Roffman RA, Carroll KM, Kabela E, Kadden R, Miller M, Duresky D. Tailoring cannabis dependence treatment for a diverse population. Addiction. 2002;97:135–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Wertz JS, Roffman RA. Self-efficacy and marijuana cessation: A construct validity analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:1022–1031. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.63.6.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Ruan WJ, Pickering R, Grant BF. Cannabis use disorders in the USA: Prevalence, correlates and co-morbidity. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1447–1460. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twomey CD. Association of cannabis use with the development of elevated anxiety symptoms in the general population: a meta-analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2017 doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-208145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandrey R, Budney AJ, Kamon JL, Stanger C. Cannabis withdrawal in adolescent treatment seekers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;78:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Marshall EC, Johnson K, Hogan J, Bernstein A, Bonn-Miller MO. Relations between anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and fear reactivity to bodily sensations to coping and conformity marijuana use motives among young adult marijuana users. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:31–42. doi: 10.1037/a0014961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, Bernstein A, Bonn-Miller MO, Marshall EC, Leyro TM. Marijuana use motives: A confirmatory test and evaluation among young adult marijuana users. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:3122–3130. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]