Abstract

Introduction

High failure rates of femoropopliteal artery (FPA) interventions are often attributed in part to severe mechanical deformations that occur with limb movement. Axial compression and bending of the FPA likely play significant roles in FPA disease development and reconstruction failure, but these deformations are poorly characterized. The goal of this study was to quantify axial compression and bending of human FPAs that are placed in positions commonly assumed during the normal course of daily activities.

Methods

Retrievable nitinol markers were deployed using a custom-made catheter system into n=28 in situ FPAs of 14 human cadavers. Contrast-enhanced, thin-section CT images were acquired with each limb in the standing (180°), walking (110°), sitting (90°) and gardening (60°) postures. Image segmentation and analysis allowed relative comparison of spatial locations of each intra-arterial marker to determine axial compression and bending using the arterial centerlines.

Results

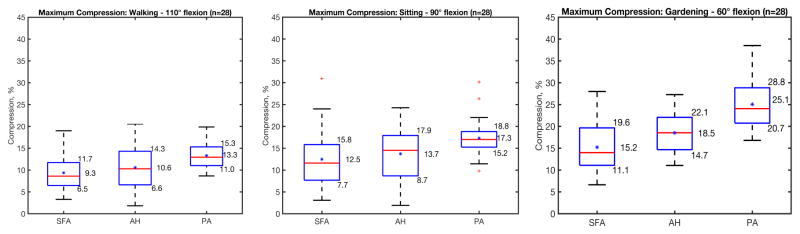

Axial compression in the Popliteal Artery (PA) was greater than in the proximal Superficial Femoral Artery (SFA) or the Adductor Hiatus (AH) segments in all postures (p=0.02). Average compression in SFA, AH, and PA ranged from 9–15%, 11–19%, and 13–25% respectively. The FPA experienced significantly more acute bending in the AH and PA segments compared to the proximal SFA (p<0.05) in all postures. In the walking, sitting, and gardening postures, average sphere radii in the SFA, AH, and PA ranged from 21–27mm, 10–18mm, 8–19mm, while bending angles ranged from 150–157°, 136–147°, and 137–148° respectively.

Conclusions

The FPA experiences significant axial compression and bending during limb flexion that occurs at even modest limb angles. Moreover, different segments of the FPA appear to undergo significantly different degrees of deformation. Understanding the effects of limb flexion on axial compression and bending might assist with reconstructive device selection for patients requiring peripheral arterial disease intervention and may also help guide the development of devices with improved characteristics that can better adapt to the dynamic environment of the lower extremity vasculature.

Keywords: femoropopliteal artery, limb flexion, deformations, axial compression, bending

1. INTRODUCTION

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) often affects the femoropopliteal artery (FPA) resulting in obstructed blood flow and malfunction of the lower limbs. PAD is a major public health burden and is associated with high morbidity, mortality and impairment in quality of life1. On a per-patient basis, health care costs for treating PAD are higher than those for both coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease2. These increased costs are likely due to the high numbers of peripheral vascular operations and interventions that fail3–6. Specifically, restenosis occurs within three years after FPA bypass in 27% of patients7, while lower extremity angioplasty and stenting fare even worse, with >45% of patients developing hemodynamically significant restenosis within just two years after treatment. Restenosis or reocclusion after minimally invasive endovascular revascularization leads to re-intervention in 37–54% of patients6 and occasionally results in major amputation. The clinical results of revascularization of the FPA are significantly worse than those for other arterial beds, such as the carotid or iliac arteries.

An important difference between the FPA and other arterial segments throughout the body is the artery’s adverse mechanical environment. Surrounded by the powerful muscles of the thigh and leg, the FPA is exposed to mechanical forces unlike any other artery. Bending, twisting and compression of the artery that occurs with movement of the lower limbs may injure the artery leading to deleterious cellular and biochemical responses, culminating in primary disease development, restenosis and reconstruction failure8–13. These deformations are particularly important for the design and function of FPA stents, as the inability of certain stent designs to accommodate these severe deformations during locomotion may result in arterial wall injury, poor device apposition, and even fracture of the stent14. We hypothesize that the FPA undergoes severe deformations during flexion of the limb and that these deformations may be localized to predictable anatomic locations. This hypothesis will be tested by measuring axial compression and bending of the FPA during limb flexion using a novel cadaver method and cross sectional imaging.

2. METHODS

2.1 Human cadaver model

Custom-made four-legged intra-arterial markers were laser-cut from nitinol tubes and heat-set to the shape depicted in Figure 1. The markers were designed to exert sufficient radial force to move with the artery during limb flexion without penetrating the wall or sliding along its lumen. Two of the four legs were longer, with one of the long legs having extra material at the tip for easy identification on imaging. The head of each marker had an opening through which a string was inserted, allowing rapid deployment and retrieval of sets of markers. Each individual marker was free to slide along the string for a distance of 2 cm, bound by beads fixed in place with knots in the string. Markers could move with the artery in any direction and were minimally influenced by movement of adjacent markers. Each marker set was compressed and loaded into a 6 French plastic tube for minimally invasive delivery into the FPA.

Figure 1.

CT of the limb flexion states demonstrating Standing (180°), Walking (110°), Sitting (90°), and Gardening (60°) postures. Bending angle is defined as the inner angle between the femur and tibia. Note severe deformations at the Adductor Hiatus and below the knee. Intra-arterial markers are blue. SFA = Superficial Femoral Artery, AH = Adductor Hiatus, PA = Popliteal Artery.

A total of 28 lightly embalmed limbs from 14 cadavers (average age 80±12 years, range 49–99 years, 8 male, 6 female, no peripheral artery interventions, no aneurysmal disease, and no metal prostheses that can interfere with CT imaging) were used to assess FPA axial compression and bending due to limb flexion. Use of lightly embalmed cadavers rather than fully embalmed cadavers allows better preservation of natural tissue properties13,15. The external iliac arteries were surgically exposed through a supra-inguinal retroperitoneal approach and 10-French short sheaths (Terumo, Somerset NJ, USA) were placed into each artery. Utilizing fluoroscopic guidance (GE-OEC Medical Systems Series 9800 Cardiovascular mobile digital C-arm system) an 80cm 8-French sheath (Cook Medical, Bloomington IN, USA) was advanced from the access site to the tibioperoneal trunk over a .035″ diameter stiff guidewire (Boston Scientific, Natick MA, USA). The shipping stylet from an aortic stent graft (Cook Medical) was sharpened and bent to a 30 degree angle 2 cm from the end and was inserted through a 100 cm long angled catheter (Terumo) into either the posterior tibial or peroneal artery and then used to puncture the artery and surrounding soft tissues to establish through and through access from the external iliac artery access point and the medial aspect of each leg. A short 6 French sheath was then placed into the tibial artery, and the marker set string was then passed through a catheter from the external iliac artery access point out the 6 French sheath in the leg. The preloaded marker set was then inserted into the 8 French sheath and each marker was then deployed approximately 2 cm apart within the in situ iliac, femoral and popliteal arteries by removing the 6 French plastic constraining sheath while maintaining traction on the marker set string distally. This method of intra-arterial marking allowed maintaining the integrity of the anatomical structures surrounding the FPA while providing sufficient number of radiopaque reference points for accurate characterization of FPA deformations. Arteries were pressurized (Harvard Apparatus Large Animal pump, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) using a 37°C radiopaque custom mixture fluid containing calcium carbonate that was specially designed to avoid tissue swelling that can distort anatomic structures. CT images (GE Light Speed VCTXT scanner GE Healthcare, Waukesha, USA) of the limbs in the standing (180°), walking (110°), sitting (90°), and gardening (60°) postures were then acquired with 0.625 mm axial resolution (Figure 1). After imaging all arteries were harvested for histological evaluation to assess the degree of atherosclerotic disease using FPA-specific 6-stage scale described in Kamenskiy et al16. Disease stage was graded by two independent operators using both longitudinal and transverse arterial sections.

2.2 Limb flexion-induced axial compression

Three-dimensional volumetric reconstructions of the bone, artery, and markers were performed with Mimics (Materialize Co., Leuven, Belgium) software utilizing a variety of segmentation and region growing techniques17. Arterial volumes were created and used to construct luminal centerlines, and then images orthogonal to these centerlines were generated, allowing more robust assessments of marker positions in the acutely bent limbs.

Axial compression (Δ_((i − 1)/i), %) or foreshortening of the artery in the flexed limb posture compared to the length of the artery in the straight limb posture (180°) was measured between each pair of consecutive markers i − 1 and i using the FPA centerline:

| (1) |

Where δ_((i − 1)/i)^straight and (δ_((i − 1)/i)^bent are the distances between markers i − 1 and i in the straight and bent configurations respectively, and L_i is the distance between these markers in the straight limb posture. The length of each FPA was normalized to account for subject-specific limb lengths. SFA length was normalized to the distance from the Profunda Femoris Artery takeoff to the AH, and PA length was normalized to the distance from the AH to the tibioperoneal trunk. The center of the AH was defined using the anterior projection view to locate the point at which the FPA crosses the femur (Figure 1).

2.3 Limb flexion-induced arterial bending

Bending of the FPA was quantified using two different approaches (Figure 2). The first method used best-fit spheres inscribed to the centerline of the FPA in the walking, sitting, and gardening postures. Since placement of the spheres was manual, a single operator placed all spheres to minimize variability. Smaller sphere radii (r) represented more acute bends.

Figure 2.

CTA reconstructions of the artery (red), luminal centerline, and intra-arterial markers (blue) used for the measurement of axial compression. Radii (r, green) of best-fit spheres inscribed along the centerline indicate higher degrees of bending with smaller radii. Bending angles α were also calculated using the same inscribed spheres and three points along the arterial centerline.

The second method utilized three-dimensional bending angle α that was defined as the angle between the most proximal and the most distal centerline points that touched the sphere surface and the point on the centerline half-way between the first two points (see insert of Figure 2). Matlab code (MathWorks, Natick MA, USA) was written to determine these points for each centerline.

Within each limb posture, minimum and average sphere radii and bending angles in the SFA, AH and PA were measured. Pearson correlations were used to compare average and minimum sphere radii and average and minimum bending angles. Paired t-tests were used to assess differences between SFA, AH, and PA bending for each limb posture.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Limb flexion-induced Axial Compression

Axial compression (%) of the SFA, AH and PA segments of the FPA in each of the limb flexion states (110°, 90° and 60°) is summarized in Figure 3. The central red line in each box indicates the median, and the bottom and top edges indicate 25th and 75th percentiles. Mean values are represented with blue asterisks inside the box. The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points not considered outliers, and the outliers are plotted using the red plus symbol and are found as q_3 + 1.5 · (q_3 − q_1) < outlier < q_1 − 1.5 · (q_3 − q_1), where q_1, q_3 are the 25th and 75th percentiles respectively. Whiskers correspond to approximately ±2.7 standard deviation or 99.3% coverage.

Figure 3.

Average Axial Compression in the Superficial Femoral Artery (SFA), Adductor Hiatus (AH) and Popliteal Artery (PA) in the walking (110°), sitting (90°) and gardening (60°) postures. Box extends to 25th and 75th percentiles, median is marked with a red horizontal line and mean values are marked with a blue asterisk.

Average axial compression in the SFA, AH and PA in the walking posture was 9.3%, 10.6%, and 13.3% respectively, which increased to 12.5%, 13.7%, and 17.3% in the sitting position respectively. In both the walking and sitting postures, the PA experienced higher compression than the SFA (p<0.01) and AH (p=0.02), but compression of the SFA and AH was not statistically different (p=0.47). In the gardening position, average axial compression in the SFA, AH and PA was 15.2%, 18.5%, and 25.1% respectively, with all segments experiencing significantly different compression from each other (p=0.01, p<0.01, p<0.01). PA segments in males were compressed more than in females in walking, sitting and gardening postures (p=0.02, <0.01, <0.01), but no gender differences were observed at the AH segment (p=0.33, 0.24, 0.19). Axial compression did not correlate with age (r=0.05–0.28, p>0.14) for either of the FPA segments or postures. No statistically significant correlations were observed between axial compression and FPA disease (p>0.1, average disease stage 3.31±1.1 with 6 indicating most severe disease16).

3.2 Limb flexion-induced Bending

Average sphere radii and bending angles in the SFA, AH, and PA for walking, sitting and gardening postures are summarized in Table 1. Sphere radii strongly correlated with bending angles, but a linear relation was not perfect (r ≥0.465, p<0.04).

Table 1.

Average and minimum sphere radii and bending angles α in the SFA, AH and PA segments for all postures (110°, 90°, and 60°).

| SFA | AH | PA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking 110° | Sitting 90° | Gardening 60° | Walking 110° | Sitting 90° | Gardening 60° | Walking 110° | Sitting 90° | Gardening 60° | ||

| Sphere Radii, mm | Avg. | 27±11 | 23±9 | 21±8 | 19±10 | 12±7 | 9±3 | 17±6 | 11±3 | 8±2 |

| Min. | 24±10 | 19±9 | 17±10 | 18±10 | 11±7 | 7±3 | 11±5 | 7±3 | 5±1 | |

| Bending Angle α, ° | Avg. | 158±6 | 155±6 | 152±7 | 149±12 | 140±10 | 136±10 | 147±6 | 141±7 | 136±6 |

| Min. | 156±7 | 152±8 | 146±11 | 148±12 | 138±10 | 130±13 | 140±8 | 132±11 | 117±17 | |

In all postures sphere radii in the SFA were significantly larger than in the AH or PA (p<0.05), but radii in the AH did not differ from those in the PA (p=0.41, p=0.31, p=0.16). The smallest radii of only 5 mm were observed in the PA in the gardening posture signifying the most acute bends in this FPA segment. Minimum radii in the AH and SFA were 1.4 and 3.4-fold larger in this same posture. Minimum sphere radii in the sitting and walking postures in the SFA and AH were 19–24 mm and 11–18 mm respectively.

Assessment of bending using angles α demonstrated similar results to measurements using radii with statistically different angles in the SFA versus AH and PA, but no difference between AH and PA (p=0.75, p=0.68, p=0.64). Visual representation of the bending angle α in all postures for the SFA, AH and PA is demonstrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Minimum (dark box) and average (light box) bending angles α in the SFA, AH and PA in all postures. Note more acute α angle with increased limb flexion.

PA segments demonstrated more acute bends in older subjects (p=0.03), but this trend was not consistent among SFA and AH segments and all postures. Gender did not appear to have a significant effect on bending (p>0.21). No correlation was observed between bending and FPA disease (p>0.2).

4. DISCUSSION

The femoropopliteal artery is a long, dynamic artery in the lower limb that frequently develops occlusive disease. It undergoes severe deformation during limb flexion, which includes axial and radial compression, bending, and torsion. These severe deformations are reflected clinically by the occurrence of stent fractures and are believed to contribute to the poor clinical outcomes of currently available open and endovascular PAD treatments. Though FPA deformations are thought to play a major role in disease development and treatment failure, detailed investigations into the exact nature of the phenomena have been limited, as in vivo measurement using conventional 2D angiographic imaging cannot capture the true 3D nature of the deformations. Even 3D CT or MR imaging is not always sufficient due to lack of identifiable arterial markers that can be tracked with limb flexion.

There are relatively few publications that have attempted to quantify axial compression and bending in the FPA. Perhaps the first study that looked at FPA deformations with limb flexion was performed by Vernon et. al.18. They used 2D angiograms to measure axial shortening of the PA and reported arterial compression of 25% at 90° flexion angle. Though severe bending of the artery was also described, no numerical assessment was provided. Utilizing similar 2D angiographic techniques, but including measurements of bending, Smouse et. al.19 and Nikanorov et. al.20 used a cadaver model and reported 5–10%, 14–23%, and 9–14% axial compression in the SFA, AH and PA segments respectively flexed at 110° and 90°. Bending was measured using sphere radii and bending angles, and the most severe bends were reported as 13 mm radius and 63° bending in the PA.

The first study to account for the 3D nature of FPA deformations was performed by Cheng et al21,22. They used 3D MRA reconstructions and arterial side branches as markers of arterial segments. Values of axial compression were reported as 5.9%, 6.7%, and 8.1% in the SFA, AH and PA respectively. Bending radii were measured at 6.66mm, 11.1mm, and 2.45mm. Klein et al23 used a 2D angiography technique but performed 3D reconstruction to assess 3D FPA deformations. They reported values of compression and bending in the SFA that were in the same range as those measured by Cheng et. al.21,22, i.e. 6%; however PA compression was closer to Smouse et. al.19, i.e. 16%. Bending radii were measured at 25mm and 5mm in the SFA and PA respectively. Similarly, using 3D reconstructed 3D rotational angiography, Gökgöl et. al.24 imaged patients in the 110° flexion posture, and reported average axial compression and bending radii of 6–16%, and 8–4mm in the PA respectively. A summary of all results using both 2D and 3D assessment methods, was published by Ansari et. al.14 who reported average FPA compression of 4–6%, 8–14%, 8–12% in the SFA, AH and PA in the sitting and walking postures, and average bending radii of 72mm and 22mm in the SFA and PA respectively.

A different approach to measuring FPA deformations was recently proposed by our group13. The method relies on using intra-arterial markers that allow measuring limb flexion-induced deformations without relying on the presence of arterial side branches. It also allows quantification of deformations between side branches where bending and compression can be focally high, such as at the AH and in the PA below the knee. Values of axial compression reported in our pilot study using just 5 limbs were 1.1 to 2.5-fold higher than those summarized by Ansari et al14, and bending was 3.7-fold higher. This current work builds on our previous work but utilizes an improved marker design, arterial pressurization, and a much more robust sample size of 28 limbs to better characterize flexion-induced axial compression and bending of the FPA in the standing, walking, sitting, and gardening postures and to account for individual variation. The markers were laser cut from Nitinol rather than soldered stainless steel wire, and they were designed to have four prongs instead of two to improve stability. The string-based delivery system allowed uniform placement and the ability to reuse the same markers in all cadavers to minimize experimental variability. The perfused cadaver model allowed achievement of physiologic pressures and temperatures during limb flexion while also providing uniform opacification of the main arteries and smaller side branches for image analysis.

Our current data demonstrate that the SFA, AH and PA axially compress 9–15%, 11–19% and 13–25% in the walking, sitting and gardening postures with maximum compression reaching 38%. These values are similar to our pilot data13 reporting 7%, 19% and 30% axial compression in the SFA, AH and PA respectively. Bending radii were measured here at 21–27mm, 9–19mm, 8–17mm in the SFA, AH and PA across all postures. These values are also similar to 20mm, 10–11mm, and 6–10mm bending radii we reported previously13.

When compared to the measurements using side branches and 2D angiography summarized by Ansari et al14, our marker method reports 2.2 and 1.5-fold more severe compression in the SFA and PA in the walking and sitting postures. The most severe deformations were experienced in the gardening posture and were 2.4 and 1.9-fold more severe than previously published data14. Though measurement of bending does not require the use of markers explicitly, values reported in this study also indicate more severe bending in both the SFA and PA. In particular, bending is as much as 3.1 and 2.0-fold more severe in the walking and sitting postures than previously reported values14. This discrepancy may come from the fact that most of the studies summarized by Ansari et al14 used 2D angiography to measure bending radii, and 2D methods can significantly underestimate acute out-of-plane bending. In addition, different measurement methods of bending utilized by different authors can also contribute to variability in results. For example, though inscribed sphere radii are common for the assessment of bending, angle measure is also used by some authors19,25. The two techniques may not provide identical results, particularly when the arterial centerline deviates from the sphere surface.

This study was designed to localize and quantify FPA deformations to help inform device manufacturers of the native deformations occurring in different segments of the FPA with limb flexion. However, its results should be viewed in the context of study limitations. First and foremost, we have used lightly embalmed human cadavers which may have different arterial properties compared to living humans. Living humans, particularly young and healthy, have significant longitudinal pre-stretch in their arteries that may reduce limb flexion-induced deformations16,22,26. However, old and diseased arteries that require reconstruction typically have very little (if any) longitudinal pre-stretch, making them similar to those arteries studied here27–29. Another limitation is the potential exacerbation or restriction of arterial bending by the markers. The marker sets and their delivery system were designed to minimally influence these parameters, and our measurement techniques have been validated in silicone tubes prior to these cadaver experiments (validation is not included in this manuscript). Finally, though we have not found a correlation between FPA disease and limb flexion-induced deformations, our sample included mostly old and moderately diseased arteries. Wider age and disease severity range, different plaque compositions (i.e. softer versus calcified plaques), or presence of certain risk factors (i.e. diabetes) may affect the results and need to be carefully studied using a larger and more diverse sample size. It is possible that stiff bulky lesions may have a significant impact on arterial behavior both with and without markers.

In summary, the present study describes axial compression and bending of human FPAs in the standing, walking, sitting, and gardening postures. Within the AH and PA segments, compression and bending appear to be more severe than previously demonstrated. These measurements help refine the description of the complex biomechanical environment in and around the human FPA, and should help foster the development of improved femoropopliteal reconstruction devices and assist in unraveling the complex pathophysiology of PAD.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

This work investigates deformations of the femoropopliteal artery with limb flexion. Understanding these deformations might assist with reconstructive device selection for patients requiring peripheral arterial disease intervention and may also help guide the development of devices with improved characteristics that can better adapt to the dynamic environment of the lower extremity vasculature.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 HL125736.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No competing interest declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mahoney EM, Wang K, Keo HH, Duval S, Smolderen KG, Cohen DJ, et al. Vascular hospitalization rates and costs in patients with peripheral artery disease in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010 Dec;3(6):642–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.930735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahoney EM, Wang K, Cohen DJ, Hirsch AT, Alberts MJ, Eagle K, et al. One-year costs in patients with a history of or at risk for atherothrombosis in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008 Oct;1(1):38–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.775247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam DJ, Beard JD, Cleveland T, Bell J, Bradbury aW, Forbes JF, et al. Bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischaemia of the leg (BASIL): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005 Dec 3;366(9501):1925–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67704-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conte MS, Bandyk DF, Clowes AW, Moneta GL, Seely L, Lorenz TJ, et al. Results of PREVENT III: A multicenter, randomized trial of edifoligide for the prevention of vein graft failure in lower extremity bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43(4):742–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schillinger M, Sabeti S, Loewe C, Dick P, Amighi J, Mlekusch W, et al. Ballon Angioplasty versus Implantation of Nitinol Stents in the Superficial Femoral Artery. N Engl J Med. 2010 May;354(18):2373–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schillinger M, Sabeti S, Dick P, Amighi J, Mlekusch W, Schlager O, et al. Sustained benefit at 2 years of primary femoropopliteal stenting compared with balloon angioplasty with optional stenting. Circulation. 2007 May 29;115(21):2745–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.688341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siracuse JJ, Giles Ka, Pomposelli FB, Hamdan AD, Wyers MC, Chaikof EL, et al. Results for primary bypass versus primary angioplasty/stent for intermittent claudication due to superficial femoral artery occlusive disease. J Vasc Surg. 2012 Apr;55(4):1001–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.10.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clowes AW, Reidy MA, Clowes MM. Mechanisms of stenosis after arterial injury. Lab Invest. 1983 Aug;49(2):208–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wensing PJW, Meiss L, Mali WPTM, Hillen B. Early Atherosclerotic Lesions Spiraling Through the Femoral Artery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998 Oct 1;18(10):1554–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.10.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunlop GR, Santos R. Adductor-Canal Thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1957 Mar 28;256(13):577–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195703282561301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.PALMA EC. Hemodynamic arteriopathy. Angiology. 1959 Jun;10(3):134–43. doi: 10.1177/000331975901000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watt J. Origin of femoro-popliteal occlusions. Br Med J. 1965;2(December):1455–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5476.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacTaggart J, Phillips N, Lomneth C, Pipinos I, Bowen R, Baxter B, et al. Three-Dimensional Bending, Torsion and Axial Compression of the Femoropopliteal Artery During Limb Flexion. J Biomech. 2014;47:2249–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ansari F, Pack LK, Brooks SS, Morrison TM. Design considerations for studies of the biomechanical environment of the femoropopliteal arteries. J Vasc Surg. 2013 Sep 16;58(3):804–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wadman MC, Lomneth CS, Hoffman LH, Zeger WG, Lander L, Walker Ra. Assessment of a new model for femoral ultrasound-guided central venous access procedural training: a pilot study. Acad Emerg Med. 2010 Jan;17(1):88–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamenskiy A, Seas A, Bowen G, Deegan P, Desyatova A, Bohlim N, et al. In situ longitudinal pre-stretch in the human femoropopliteal artery. Acta Biomater. 2016 Mar;32:231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamenskiy A, Miserlis D, Adamson P, Adamson M, Knowles T, Neme J, et al. Patient demographics and cardiovascular risk factors differentially influence geometric remodeling of the aorta compared with the peripheral arteries. Surgery. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.05.013. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vernon P, Delattre J, Johnson E. Dynamic modifications of the popliteal arterial axis in the sagittal plane during flexion of the knee. Surg Radiol Anat. 1987:37–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02116852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smouse BHB, Nikanorov A, Laflash D. Biomechanical Forces in the Femoropopliteal Arterial Segment. Endovasc Today. 2005:60–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikanorov A, Smouse HB, Osman K, Bialas M, Shrivastava S, Schwartz LB. Fracture of self-expanding nitinol stents stressed in vitro under simulated intravascular conditions. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(2):435–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng C, Wilson N, Hallett R. In vivo MR angiographic quantification of axial and twisting deformations of the superficial femoral artery resulting from maximum hip and knee flexion. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:979–87. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000220367.62137.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng CP, Choi G, Herfkens RJ, Taylor Ca. The effect of aging on deformations of the superficial femoral artery resulting from hip and knee flexion: potential clinical implications. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010 Feb;21(2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein AJ, Chen SJ, Messenger JC, Hansgen AR, Plomondon ME, Carroll JD, et al. Quantitative assessment of the conformational change in the femoropopliteal artery with leg movement. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;74(5):787–98. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gökgöl C, Diehm N, Kara L, Büchler P. Quantification of popliteal artery deformation during leg flexion in subjects with peripheral artery disease: a pilot study. J Endovasc Ther. 2013 Dec;20(6):828–35. doi: 10.1583/13-4332MR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikanorov A, Smouse HB, Osman K, Bialas M, Shrivastava S, Schwartz LB. Fracture of self-expanding nitinol stents stressed in vitro under simulated intravascular conditions. J Vasc Surg. 2008 Aug;48(2):435–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desyatova A, MacTaggart J, Poulson W, Deegan P, Lomneth C, Sandip A, et al. The Choice of a Constitutive Formulation for Modeling Limb Flexion-Induced Deformations and Stresses in the Human Femoropopliteal Arteries of Different Ages. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10237-016-0852-8. Accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamenskiy AV, Pipinos II, Dzenis YA, Lomneth CS, Kazmi SaJ, Phillips NY, et al. Passive biaxial mechanical properties and in vivo axial pre-stretch of the diseased human femoropopliteal and tibial arteries. Acta Biomater. 2014 Dec 24;10(3):1301–13. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamenskiy AV, Pipinos II, Dzenis Ya, Phillips NY, Desyatova AS, Kitson J, et al. Effects of age on the physiological and mechanical characteristics of human femoropopliteal arteries. Acta Biomater. 2015 Oct 6;11:304–13. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamenskiy A, Seas A, Deegan P, Poulson W, Anttila E, Sim S, et al. Constitutive Description of Human Femoropopliteal Artery Ageing. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10237-016-0845-7. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]