Abstract

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum in humans and dystrophic cardiac calcification in mice are heritable disorders characterized by dystrophic calcification of soft connective tissues related to the defective function of the ABCC6 (human)/Abcc6 (mouse) transporter. Of particular interest is the finding of calcified vibrissae in Abcc6−/− mice, which facilitates the study of dystrophic calcification by histological techniques. We aimed to determine whether mice prone to dystrophic cardiac calcification (C3H/HeOuJ and DBA/2J strains) presented similar vibrissae changes and to evaluate the value of microcomputed tomography to quantify the extent of mystacial vibrissae calcifications. These calcifications were absent in DBA/2J and C57BL/6J control mice. In both Abcc6−/− and C3H/HeOuJ mice, calcifications progressed in a caudal-rostral direction with aging. However, the calcification process was delayed in C3H/HeOuJ mice, indicating an incomplete expression of the calcification phenotype. We also found that the calcification process in the cephalic region was not limited to mystacial vibrissae but was also present in other periorbital sensorial vibrissae. The vibrissae calcification was circular and encompassed the medial region of the vibrissae capsule, adjacent to the ring and cavernous sinuses (the areas adjacent to blood and lymphatic vessels). Collectively, our findings confirm that Abcc6 acts as an inhibitor of spontaneous chronic mineralization and that microcomputed tomography is a valuable noninvasive tool for the assessment of the calcification phenotype in Abcc6-deficient mice.

Calcification of soft tissues occurs with aging, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, or end-stage renal disease, but it can also result from certain genetic conditions. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE; Online Mendelian Inheritance of Man 264800) in humans and dystrophic cardiac calcification (DCC) in mice are both heritable disorders, defined by dystrophic mineralization of cardiovascular, ocular, or dermal tissues.1, 2 These two conditions derive from loss-of-function mutations in the human ABCC6 and the mouse Abcc6 ortholog genes.3, 4, 5, 6 PXE displays dystrophic calcifications primarily in dermal, ocular, and vascular tissues associated with clinical manifestations.1 It is caused by mutations in the ABCC6 gene, which encodes a transmembrane transporter almost exclusively expressed in the liver and kidneys.3, 4, 5 Two knockout mouse models of PXE have been developed,7, 8 and both recapitulate the histopathological features of the condition. Thus, these mice provide an excellent tool for studying the molecular events leading to dystrophic calcification. Of particular interest is that Abcc6−/− mice develop early and progressive calcification of the connective capsule surrounding vibrissae of muzzle skin.8 This characteristic serves as a unique biomarker of disease progression in the PXE mouse models.9

The DCC phenotype has long been recognized in certain congenic strains of mice (C3H/HeJ, DBA/2J, or 129S1/SvJ). These mice develop soft tissue calcifications that can lead to congestive heart failure, especially when subjected to high-fat diets or cardiovascular insults.2, 10, 11 By examining F2 intercrosses of C57BL/6J and susceptible C3H/HeJ mice, Ivandic et al11 identified a major susceptibility locus, Dyscalc1, on chromosome 7. Within this locus, a single specific Abcc6 mutation results in a 65% constitutive decrease in Abcc6 protein levels in liver and is directly responsible for the DCC phenotype.6, 12 Three additional minor Dyscalc loci affecting the penetrance and expression of the DCC phenotype were also identified (Dyscalc2, Dyscalc3, andDyscalc4) and mapped to chromosomes 4, 12, and 14, respectively.13

It remains unknown if DCC mice present whisker mineralization similar to Abcc6−/− mice. In addition, the progression of the mineralization phenotype has always been determined postmortem with histological stains7, 8, 11 or histochemical methods.14, 15 Herein, we evaluated if microcomputed tomography (microCT), a noninvasive method, could determine and quantify in vivo the extent and progression of vibrissae calcifications in several Abcc6-deficient mice (Abcc6−/−, C3H/HeOuJ, and DBA/2J strains), representing the PXE and DCC phenotypes.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Abcc6−/− mice were provided by Dr. Arthur Bergen's laboratory (The Netherlands Institute of Neuroscience, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The generation and mineralization phenotype of these animals were previously described.7 The Abcc6−/− mice used in these studies were backcrossed onto a C57BL/6J background for at least 10 generations. C3H/HeOuJ, DBA/2J, and C57BL/6J control mice were all obtained from Charles River Laboratories (L'Arbresle, France). To ensure optimal detection of calcifications with microCT, we only used female mice because the phenotype is found more frequently in females in both patients with PXE1 and mice with DCC.2 We have studied the C3H/HeOuJ mice instead of the parent C3H/HeJ strain for availability reasons. The C3H/HeOuJ derives from the C3H/HeJ strain, and both are genetically similar, with the exception of the presence of a mutation in the Toll-like receptor 4 gene in C3H/HeJ (The Jackson Laboratory; http://jaxmice.jax.org/strain/000659.html, last accessed April 4, 2012). All strains of mouse were bred and maintained in our animal facilities under a 12-hour light-dark cycle. All animals had access to water and a standard diet ad libitum. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Angers, Angers, France, in accordance with government guidelines.

MicroCT Images

Before in vivo scans, mice were anesthetized with an i.p. injection of a mixture of ketamine-xylazine (120 mg/6 mg per kg). MicroCT images were obtained using a SkyScan 1076 X-ray microtomograph (SkyScan, Kontich, Belgium). The source was set at 60 kV and 165 μA. The spatial resolution was 35 μm on-a-side cubic voxel. After acquisition, each raw image data set was reconstructed using the SkyScan software package [NRecon version 1.6.3.1 for two-dimensional (2D) slices and CTAnalyser version 1.10.1.0 for three-dimensional (3D) models; Kontich, Belgium]. Before image processing and 3D rendering with NIH ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij, last accessed April 4, 2012), the data files were converted from a tagged image file format to a bitmap format using the t-conv. software (SkyScan). For calcification quantification, all images were converted to an 8-bit gray scale and a threshold was manually applied using an ImageJ multithresholder plug-in (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/plugins/multi-otsu-threshold.html, last accessed April 4, 2012). The Otsu filter was used, and the lower threshold was set between 40 and 50. Each microCT image data set was analyzed by two investigators working independently (Y.L.C. and O.L.S.). The areas of calcification in each 2D coronal image were manually selected by the operators within the whisker regions and clearly away from the bone of the cranium (Figure 1A). The total number of relevant pixels was determined for each image data set. Last, the ImageJ plug-in 3D viewer was used for 3D rendering of each mouse.

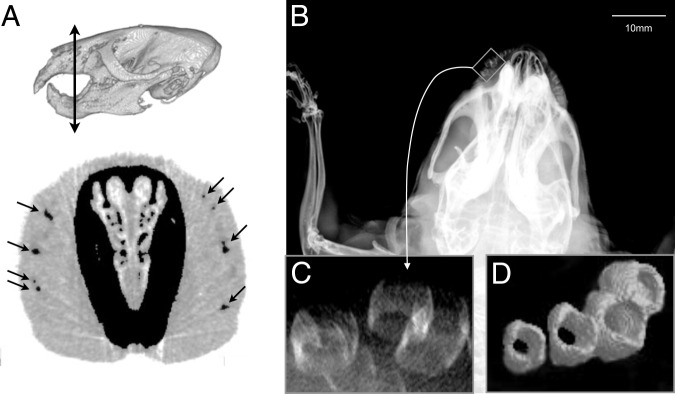

Figure 1.

Abcc6−/− mice aged 12 months. A: Top panel, a 3D image of the animal's skull. Double-headed arrow indicates the approximate location of the 2D image shown below. Bottom panel, a 2D coronal image displaying areas of calcification in the muzzle (arrows) after manual selection for calcification quantification. B and C: Unprocessed 2D microcomputed image of the cephalic region showing vibrissae calcifications in the mystacial pads (C, higher magnification of the boxed area in B). D: 3D-reconstructed image illustrating the circular shape of the capsule calcification.

Histopathological and Colorimetric Measurement of Calcium Load and Correlation with microCT Mineralization Evaluation

In an independent set of animals from all four strains (aged 12 months), the whiskers were routinely stained with the von Kossa method to demonstrate the presence of calcium salts.

To assess the relationship between mineral deposition measured with microCT and tissue calcification, we performed a colorimetric assay to measure free calcium within the muzzle skin of the Abcc6−/− mice. Briefly, eight additional mice (aged 4, 9, 15, and 22 months) were analyzed with microCT and sacrificed. The skin from either side of the muzzle was harvested, weighted, minced, and incubated at room temperature for 48 hours in 0.15N HCl. The concentration of calcium in the supernatant from the 16 samples was evaluated by measuring the absorbance at 550 nm using the Calcium (CPC) LiquiColor Test, following the manufacturer's instructions (Stanbio, Boerne, TX). The calcium content was normalized to total tissue weight and expressed as follows: mg of calcium/g of tissue. The correlation between calcium content and CT scan mineralization (total pixels per vibrissae) was calculated for each vibrissae using Prism software (Graph Pad, La Jolla, CA).

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed with Prism statistical software. Statistical comparisons between Abcc6−/− and C3H/HeOuJ 12-month-old mice were performed using two-tailed unpaired Student's t-tests. All data were expressed as mean ± SEM, and all statistical comparisons were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

The correlation coefficient for the determination of the total number of relevant pixels between the two operators was R2 = 0.955, indicating that manual thresholding led to little interoperator variability.

Morphological Characteristics of Calcified Tissue in the Whiskers

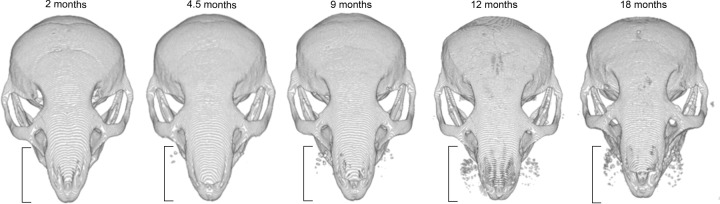

The 2D and 3D images obtained with microCT allowed us to determine the anatomical distribution, progression, and severity of vibrissae calcifications. The dominant feature of the calcifications was their circular shape (Figure 1, B–D), primarily affecting the area of the collagenous capsule wall and apparently encompassing the medial region of the capsule, adjacent to both ring and cavernous sinuses.16 Furthermore, the calcifications initially affected the largest vibrissae located within the caudal region of the mystacial pad and progressed toward the rostral areas with time (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Progression of the whiskers calcification with age in the caudal-rostral direction in Abcc6−/− mice from the age of 2 to 18 months.

Quantification of Calcification

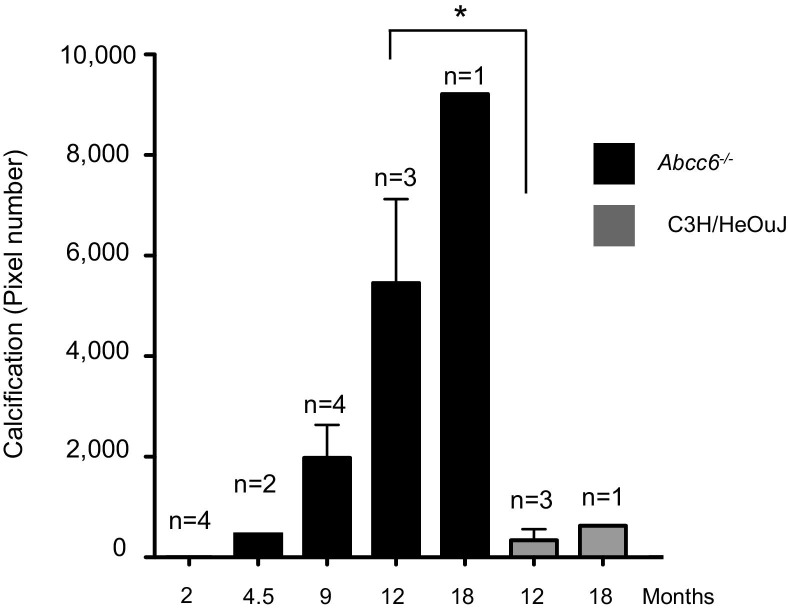

We found a steep progression in whiskers calcification within the first year of life of Abcc6−/− mice (Figure 3). Interestingly, C3H/HeOuJ mice showed a detectable level of vibrissae calcification, which was significantly less than in Abcc6−/− mice at the age of 1 year (P = 0.04). The earliest detectable mineralization in C3H/HeOuJ mice occurred at the age of 12 months, whereas the earliest mineralization was observed at the age of 3 months in Abcc6−/− mice (data not shown). Calcification in C3H/HeOuJ mice followed the same caudal-rostral progression in the mystacial calcification process (Figure 3, Figure 4), but with a greater variability than with Abcc6−/− mice (within the limits of this small cohort). On the contrary, the whiskers of DBA/2J and C57BL/6J mice did not show visible mineralization at ages up to 18 months (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Quantification of microCT data representing the whiskers calcification between the ages of 2 and 18 months in Abcc6−/− and C3H/HeOuJ mice. At 12 months, calcification is significantly lower in C3H/HeOuJ mice than in Abcc6−/− animals. *P = 0.04.

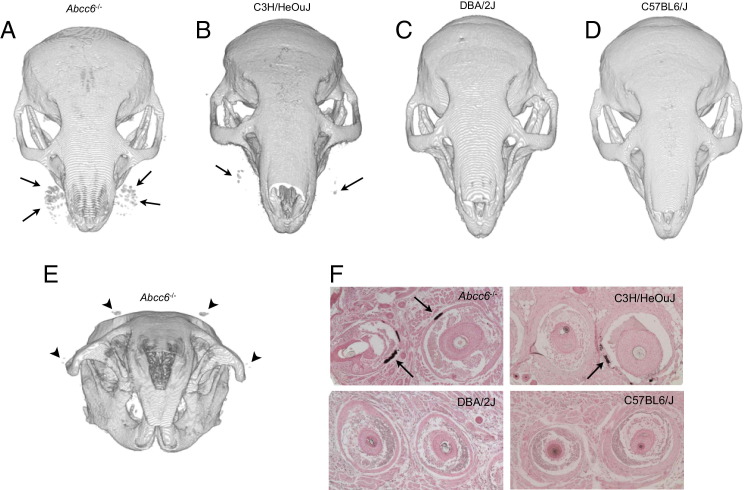

Figure 4.

A 3D rendering of 12-month-old Abcc6−/− (A), C3H/HeOuJ (B), DBA/2J (C), and C57BL/6J (D) mice. The various levels of mystacial calcifications (arrows) between the four strains of mice are clearly visible. E: A 3D rendering shows novel calcifications (arrowheads) in the periorbital area. F: Representative images of von Kossa staining of paraffin-embedded vibrissae sections from all four strains of mouse are shown. Arrows indicate calcified sections of the capsule. The von Kossa staining demonstrates the presence of calcium salts in Abcc6−/− and C3H/HeOuJ mouse whiskers. The staining for DBA/2J and C57BL/6J mice is negative and consistent with the microCT findings. Approximately five sections were needed to find one focus of calcification in C3H/HeOuJ whiskers, whereas all sections from Abcc6−/− mice were calcified. This is also in agreement with the mildest calcification phenotype demonstrated in C3H/HeOuJ mice with microCT scans.

The von Kossa staining demonstrated the presence of calcium salts in Abcc6−/− and C3H/HeOuJ mouse whiskers. The staining for DBA/2J and C57BL/6J mice was negative and consistent with the microCT findings.

The correlation coefficient for colorimetry-determined calcium load versus mineralization, demonstrated on CT scans in Abcc6−/− mice, was as follows: r2 = 0.9023 (95% CI, 0.713 to 0.969) (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Extended Sites of Calcification within the Cephalic Region of Abcc6−/− Mice

MicroCT also allowed us to detect additional locations of soft tissue calcification not previously reported. Close examination of the high-resolution 3D-reconstructed images revealed two novel individual foci of mineralization within the periorbital skin areas. The supraorbital single sinus hair showed extensive calcification comparable to that of the mystacial vibrissae (Figure 4). By contrast, calcification observed in the postero-orbital sinus hair was less intense and at the lower limit of detection (Figure 4).

Discussion

As previously shown, the calcification of the vibrissae is a remarkable and consistent feature of the phenotype of Abcc6−/− mice and a useful marker for progression of the calcification process.8, 9, 15, 17, 18 The near-exponential progression in whiskers calcification within the first year of life (Figure 3) was similar herein to what has been observed by Brampton et al,15 who have used a different histochemical approach to measure the calcium content in the same tissues. We demonstrated herein the correlation between the calcification, as seen with CT scans, and the actual quantity of calcium measured by this specific assay (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In the present study, we found that mice with partial Abcc6 deficiency, similar to Abcc6−/−-null animals, can exhibit soft tissue calcification in the mystacial vibrissae capsules. We also provide evidence that the calcification process in the cephalic region of Abcc6−/− mice is not limited to mystacial vibrissae. The supraorbital single sinus hair, which exhibits similar morphological and sensorial function than the mystacial vibrissae,19 showed extensive calcification, comparable to that of the mystacial vibrissae. Therefore, most, if not all, sensorial vibrissae appear to be the targets for ectopic mineralization as a result of the Abcc6 defect. We speculate that this selective calcification is related to the rich vascular network of the vibrissae follicles, which is absent from common hair follicles. The combination of histological and 3D microCT data clearly shows that the calcification does not affect the outer conical body (ie, infra-infundibular segment) and the deepest part of the capsule, but rather covers the regions of the capsule of the distal ring sinus and the adjacent proximal cavernous sinus, presumably because of their immediate contact with sinus blood and lymphatic vessels (unpublished data). This could also explain why mineralization first affects the large caudal vibrissae follicles.

Our study also brings further support to the notion that the main function of Abcc6 is that of an indirect inhibitor of spontaneous chronic mineralization of connective tissues. The protective role of Abcc6 against calcification depends on the activity of at least three other genes of unknown characteristics located at independent loci on chromosomes 4, 12, and 14.13 Indeed, of the three strains of mouse we studied, Abcc6-null mice of C57BL/6J background presented the earliest and the most extensive vibrissae calcification, as expected. The C3H/HeOuJ mice showed a delayed and modest spontaneous chronic calcification of vibrissae, indicating an incomplete expression of the phenotype. This is likely because of the residual Abcc6 expression (and function) in the liver.6, 12 Interestingly, the DBA/2J strain, which shares the same Abcc6 genotype as C3H/HeOuJ mice, did not develop detectable vibrissae calcification in our study. The C3H/HeOuJ mice were derived from the DBA/2J strain and, therefore, must have subsequently acquired genetic alterations that rendered them more susceptible to this type of chronic and spontaneous mineralization than their parent strain. Others13, 20 have reported similar conclusions, although these previous studies described the related, yet distinct, acute and induced DCC phenotype in C3H/HeJ mice. C3H/HeOuJ mice are similar to the C3H/HeJ strain, although they lack the Toll-like receptor 4 gene mutation of the C3H/HeJ animals. Given that the propensity to spontaneous calcification of the C3H/HeOuJ mice appears similar to that of C3H/HeJ mice (although we did not compare them directly), it is unclear what role, if any, the Toll-like receptor 4 gene might play in the mineralization phenotype of these animals. Also, the variability in vibrissae calcification of the C3H/HeOuJ suggests that this murine line might be more susceptible to environmental factors than the others, especially the C57BL/6J mice.

Based on our results, we concluded that microCT is a valuable tool for the in vivo quantification of the calcification phenotype of Abcc6-deficient mice. Serial microCT studies would allow for noninvasive monitoring of calcification of vibrissae and possibly other tissues in Abcc6−/− mice, allowing individual mice to be observed long-term without the need to sacrifice animals for histopathological study and chemical quantification. The sensitivity of microCT seems somewhat lower than histochemical15 or histological9, 21 techniques, but a large part of these discrepancies is essentially because of the threshold used for calcification detection. Recent studies17 have confirmed the usefulness of this method for controlled trials in mice. A similar approach in human patients with PXE and/or a dystrophic calcification phenotype would be extremely useful because repeated skin biopsy specimens, as used by Yoo et al,22 for patients with PXE are difficult to use in both clinical practice and trials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Theo Gorgels and Prof. Arthur Bergen (Netherlands Institute of Neuroscience, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for sharing the Abcc6−/− mice. All microCT scans were performed at the Center for Functional Imaging in Biology and Medicine (CIFAB, LUNAM University, Angers, France).

Footnotes

O.L.S. was present at LUNAM University, Angers, France, as an invited Professor at the time of this study.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjpathol.org or at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.007.

Supplementary data

Correlation between the calcification measured with microCT (total pixels per vibrissae) and the quantity of calcium (per gram of whisker) measured by a specific colorimetric assay in an independent set of eight Abcc6-/- mice.

References

- 1.Chassaing N., Martin L., Calvas P., Le Bert M., Hovnanian A. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: a clinical, pathophysiological and genetic update including 11 novel ABCC6 mutations. J Med Genet. 2005;42:881–892. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.030171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaton G.J., Custer R.P., Johnson F.N., Stabenow K.T. Dystrophic cardiac calcinosis in mice: genetic, hormonal, and dietary influences. Am J Pathol. 1978;90:173–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Saux O., Urban Z., Tschuch C., Csiszar K., Bachelli B., Quaglino D., Pasquali-Ronchetti I., Pope F.M., Richards A., Terry S., Bercovitch L., de Paepe A., Boyd C.D. Mutations in a gene encoding an ABC transporter cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat Genet. 2000;25:223–227. doi: 10.1038/76102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergen A.A., Plomp A.S., Schuurman E.J., Terry S., Breuning M., Dauwerse H., Swart J., Kool M., van Soest S., Baas F., ten Brink J.B., de Jong P.T. Mutations in ABCC6 cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat Genet. 2000;25:228–231. doi: 10.1038/76109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ringpfeil F., Lebwohl M.G., Christiano A.M., Uitto J. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: mutations in the MRP6 gene encoding a transmembrane ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6001–6006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100041297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng H., Vera I., Che N., Wang X., Wang S.S., Ingram-Drake L., Schadt E.E., Drake T.A., Lusis A.J. Identification of Abcc6 as the major causal gene for dystrophic cardiac calcification in mice through integrative genomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4530–4535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607620104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorgels T.G., Hu X., Scheffer G.L., van der Wal A.C., Toonstra J., de Jong P.T., van Kuppevelt T.H., Levelt C.N., de Wolf A., Loves W.J., Scheper R.J., Peek R., Bergen A.A. Disruption of Abcc6 in the mouse: novel insight in the pathogenesis of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1763–1773. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klement J.F., Matsuzaki Y., Jiang Q.J., Terlizzi J., Choi H.Y., Fujimoto N., Li K., Pulkkinen L., Birk D.E., Sundberg J.P., Uitto J. Targeted ablation of the Abcc6 gene results in ectopic mineralization of connective tissues. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8299–8310. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8299-8310.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaRusso J., Li Q., Jiang Q., Uitto J. Elevated dietary magnesium prevents connective tissue mineralization in a mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum (Abcc6−/−) J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1388–1394. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajusz E. Dystrophic calcification of myocardium as conditioning factor in genesis of congestive heart failure: an experimental study. Am Heart J. 1969;78:202–210. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(69)90009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivandic B.T., Qiao J.H., Machleder D., Liao F., Drake T.A., Lusis A.J. A locus on chromosome 7 determines myocardial cell necrosis and calcification (dystrophic cardiac calcinosis) in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5483–5488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aherrahrou Z., Doehring L.C., Ehlers E.M., Liptau H., Depping R., Linsel-Nitschke P., Kaczmarek P.M., Erdmann J., Schunkert H. An alternative splice variant in Abcc6, the gene causing dystrophic calcification, leads to protein deficiency in C3H/He mice. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7608–7613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivandic B.T., Utz H.F., Kaczmarek P.M., Aherrahrou Z., Axtner S.B., Klepsch C., Lusis A.J., Katus H.A. New Dyscalc loci for myocardial cell necrosis and calcification (dystrophic cardiac calcinosis) in mice. Physiol Genomics. 2001;6:137–144. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.6.3.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang Q., Li Q., Uitto J. Aberrant mineralization of connective tissues in a mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum: systemic and local regulatory factors. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1392–1402. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brampton C., Yamagouchi Y., Vanakker O., Van Laer L., Chen L., Thakore M., De Paepe A., Pomozi V., Szabo P.T., Martin L., Varadi A., Le Saux O. Vitamin K does not prevent soft tissue mineralization in a mouse model of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1810–1820. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.11.15681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J.N., Koh K.S., Lee E., Park S.C., Song W.C. The morphology of the rat vibrissal follicle-sinus complex revealed by three-dimensional computer-aided reconstruction. Cells Tissues Organs. 2011;193:207–214. doi: 10.1159/000319394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorgels T.G., Waarsing J.H., Herfs M., Versteeg D., Schoensiegel F., Sato T., Schlingemann R., Ivandic B., Vermeer C., Schurgers L.J., Bergen A.A. Vitamin K supplementation increases vitamin K tissue levels but fails to counteract ectopic calcification in a mouse model for pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Mol Med. 2011;89:1125–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0782-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang Q., Li Q., Grand-Pierre A.E., Schurgers L.J., Uitto J. Administration of vitamin K does not counteract the ectopic mineralization of connective tissues in Abcc6 (−/−) mice, a model for pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:701–707. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.4.14862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams J.B., de Permentier P., Waite P.M. The rat's postero-orbital sinus hair, II: normal morphology and the increase in peripheral innervation with adjacent nerve section. J Comp Neurol. 1992;322:213–223. doi: 10.1002/cne.903220207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korff S., Schoensiegel F., Riechert N., Weichenhan D., Katus H.A., Ivandic B. Fine mapping of Dyscalc1, the major genetic determinant of dystrophic cardiac calcification in mice. Physiol Genomics. 2006;25:387–392. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00010.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chappard D., Retailleau-Gaborit N., Legrand E., Baslé M.F., Audran M. Comparison insight bone measurements by histomorphometry and microCT. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1177–1184. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoo J.Y., Blum R.R., Singer G.K., Stern D.K., Emanuel P.O., Fuchs W., Phelps R.G., Terry S.F., Lebwohl M.G. A randomized controlled trial of oral phosphate binders in the treatment of pseudoxanthoma elasticum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Correlation between the calcification measured with microCT (total pixels per vibrissae) and the quantity of calcium (per gram of whisker) measured by a specific colorimetric assay in an independent set of eight Abcc6-/- mice.