Abstract

Introduction

The combination of opioids and central nervous system depressants such as benzodiazepines and barbiturates has an additive effect on the frequency of oversedation and respiratory depression requiring naloxone use in hospitalized patients. Gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin) are frequently prescribed with opioids for their opioid-sparing and adjuvant analgesic effects. There is limited literature on the risk of respiratory depression due to the combination of opioids and gabapentinoids requiring naloxone administration.

Methods

This retrospective study evaluated patients who were prescribed opioids and at least one dose of naloxone between March 1, 2014 and September 30, 2016. The primary objective of this study was to compare the frequency of respiratory depression among patients who received naloxone and opioids (non-gabapentinoid group) with those who received naloxone, opioids, and gabapentinoids (gabapentinoid group). Secondary objectives included comparing the association of oversedation, using the Pasero Opioid-induced Sedation Scale, and various risk factors with those in the gabapentinoid group.

Results

A total of 153 patient episodes of naloxone administration (102 in the non-gabapentinoid and 51 in the gabapentinoid groups) in 125 unique patients were included in the study. For the primary objective, there were 33 episodes of respiratory depression associated with the non-gabapentinoid group (33/102=32.4%) versus 17 episodes of respiratory depression with the gabapentinoid group (17/51=33.3%) (p=0.128). Secondary objectives showed a significant association between respiratory depression and surgery in the previous 24 hours (p=0.036) as well as respiratory depression and age >65 years (p=0.031) for patients in the non-gabapentinoid group compared to the gabapentinoid group.

Conclusion

There was no significant association of respiratory depression in the gabapentinoid group versus the non-gabapentinoid group. There was an increased risk of respiratory depression in the gabapentinoid group, specifically in patients who had surgery within the previous 24 hours.

Keywords: naloxone, opioid analgesics, respiratory depression, gabapentin, pregabalin, POSS

Introduction

Opioid-related adverse events, specifically respiratory depression, that necessitate the use of naloxone occur frequently in hospitals worldwide. The Joint Commission reported that 11% of opioid-related adverse drug events were attributed to excessive dosage and medication interactions.1 The Joint Commission reported that the most commonly associated medication interactions leading to side effects were benzodiazepines and cardiac medications. Additionally, the Joint Commission estimated that on average, the incidence of postoperative patients experiencing respiratory depression was approximately 0.5%. This is due to inadequate monitoring, lack of knowledge regarding differing potencies of opioids, and improper prescribing.1

In one study, hospitalized patients with multiple risk factors were found to have a higher risk of receiving naloxone for respiratory depression and/or sedation compared to patients with fewer risk factors.2 Risk factors included patients receiving concomitant central nervous system (CNS) depressant medications, and those with history of smoking, renal disease, cardiac disease, and respiratory disease.2

A recent study at UC San Diego Health (UCSDH) evaluated naloxone use in hospitalized patients receiving opioids.3 Only 24% of the patients who received naloxone received the drug for the reversal of respiratory depression; the remaining patients received naloxone for oversedation as documented by the validated Pasero Opioid-induced Sedation Scale (POSS).3–5 The study also showed that patients receiving naloxone for respiratory depression often received other CNS depressant medications (such as antiepileptic drugs [AEDs]) in addition to opioids. Of those who received AEDs, 70% of patients received gabapentin.3 The study also found that patients who received benzodiazepines and opioids were significantly more likely to have respiratory depression reversal than those who did not receive benzodiazepines. Interestingly, gabapentin coadministration with opioids did not significantly affect reversal of respiratory depression.3

Currently, gabapentin and pregabalin are US Food and Drug Administration-approved for postherpetic neuralgia in adults as well as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of partial-onset seizures.6,7 Gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin) are prescribed frequently in the hospital as well as in the outpatient setting for off-label indications such as acute and chronic pain, anxiety, sleep disorders, migraines, and drug and alcohol withdrawal.8–10 With the frequent use of gabapentinoids for various indications, there have been some studies examining the oversedating effect of gabapentinoids, including respiratory depression.11,12

Given the published literature supporting the increased frequency for various uses of gabapentinoids as well as their risk for sedation and possibly respiratory depression, we aimed to determine the additive effect of opioids and gabapentinoids on incidence of respiratory depression compared to opioids alone. Naloxone administration was used as a marker of opioid-related respiratory depression. A chart review of all naloxone administrations was then performed to identify those cases that met our definition of respiratory depression. We hypothesized that in patients who received naloxone, the combination of opioids and gabapentinoids would lead to an increased risk of respiratory depression, compared to prescription of opioids alone.

Methods

The UCSDH Human Research Protections Program (HRPP) granted institutional review board approval. Patient consent to review their medical records was waived by the HRPP because the research was minimal risk, the waiver would not adversely affect patients, and the research could not have been practically conducted without the waiver. An adequate plan to protect the identifiers, including using deidentified data as much as possible and utilizing password protection, was detailed in research plan.

This was a retrospective study of hospitalized patients receiving naloxone and opioids (non-gabapentinoid group) compared to patients receiving naloxone, opioids, and gabapentinoids (gabapentinoid group) between March 1, 2014 and September 30, 2016. Patients were excluded if they received naloxone in the intensive care unit, emergency department, or postacute care unit. Patients were also excluded if they were prisoners, <18 years of age, and if they had received a benzodiazepine within 24 hours of receiving naloxone.

Data collection

All data were collected from UCSDH EPIC™ (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) electronic medical record (EMR) and recorded on a Microsoft Excel™ (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. Patient demographic data such as patient name, medical record number, age, and sex were collected. Comorbid conditions such as surgery within the previous 24 hours, chronic heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) were identified via past medical history documented in the patient’s chart via International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes at the time of encounter in which naloxone was administered. Kidney function was quantified by the patients’ glomerular filtration rates. Doses and times of naloxone administration, oxygen saturations documented immediately prior to and after naloxone administration, and respiratory rates immediately prior to and after naloxone administration were recorded from patient’s chart.

The primary objective of this study was to compare the association of naloxone administration with respiratory depression between the non-gabapentinoid group and the gabapentinoid group. Secondary objectives included the documented indication of naloxone in the UCSDH EPIC™ (ie, for sedation versus respiratory depression versus undocumented/unknown); the association of sedation as measured by POSS among non-gabapentinoid group and gabapentinoid group; the relationship between respiratory depression and age >65 years, comorbid conditions such as surgery within the previous 24 hours, CHF, COPD, OSA, and the patient’s glomerular filtration rate (GFR); as well as the dose of opioids in oral morphine equivalents and dose of gabapentinoids.

Respiratory depression was defined as a respiratory rate of <8 breaths per minute and oxygen saturation either below 92% or a decrease of more than 5% from baseline in patients with a baseline of SPO2 <90%. Sedation level was measured by POSS. The POSS was recorded prior to the administration of naloxone as well as after administration. A POSS of 1 or 2 is considered an acceptable level of awareness as the patient is either awake and alert or slightly drowsy but easily arousable. A POSS of 3 or 4 is considered excessively sedated and indicates a risk of respiratory depression. A POSS of 3 indicates the patient is frequently drowsy, easily aroused but falls back asleep without constant stimulation, while a POSS of 4 indicates a patient is somnolent, with minimal or no response to verbal and physical stimulation. The distinction between respiratory depression and sedation was made based on physician documentation and nursing assessment records. If a patient did not meet criteria for respiratory depression as defined earlier or sedation was not identified in the physician and nursing documentation, the patient’s naloxone indication was classified as unknown.

The total daily dose of opioids in oral morphine equivalents was calculated using the UCSDH equianalgesia conversion chart (Figure S1). Total daily doses of gabapentinoids were classified as either high dose or low dose via an internal study definition. Patients were classified as high dose if they received ≥1,800 mg of gabapentin or ≥300 mg of pregabalin and low dose if they received <1,800 mg of gabapentin or <300 mg of pregabalin. Internal study definition of high versus low dose of gabapentinoids was determined using 50% of the maximum daily dose of gabapentin and pregabalin. Total doses of opioids and gabapentinoids were tabulated for the 24 hours prior to first dose of naloxone administered. An episode of naloxone administration was defined as a single dose or multiple doses given for respiratory depression or sedation with less than 2 hours between naloxone doses. If naloxone was administered ≥2 hours from a previous naloxone administration, this was defined as a separate episode.

Statistical analysis

Demographics and the primary objective were analyzed using χ2 and/or Fisher’s exact tests, with significance set at p<0.05. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS, version 24 (Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

There were 125 unique patients who met the inclusion criteria: 89 unique patients in the non-gabapentinoid group and 36 unique patients in the gabapentinoid group (Table 1). A total of 153 episodes of naloxone administration occurred during the study period, with 102 episodes in the non-gabapentinoid group and 51 episodes in the gabapentinoid group.

Table 1.

Unique patient demographics and variables (n=125 unique patients)

| Unique patient demographics (n=125) | Non-gabapentinoids group (n=89) | Gabapentinoids group (n=36) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.031 | ||

| ≥65 years | 49 (55%) | 12 (33.3%) | |

| Sex | 0.076 | ||

| Male | 46 (51.7%) | 12 (33.3%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Surgery in the last 24 hours | 19 (21.3%) | 2 (5.5%) | 0.036 |

| CHF | 15 (16.5%) | 8 (22.2%) | 0.611 |

| COPD | 11 (12%) | 5 (13.8%) | 0.776 |

| OSA | 10 (11.2%) | 2 (5.5%) | 0.506 |

| GFR | 0.444 | ||

| >60 mL/min | 43 (48.3%) | 20 (55.5%) | |

| >30–60 mL/min | 25 (28.1%) | 6 (16.7%) | |

| >10–30 mL/min | 16 (18%) | 9 (25%) | |

| <10 mL/min | 5 (5.6%) | 1 (2.8%) |

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

For the primary objective, there were a total of 50 episodes of respiratory depression: 33 episodes of respiratory depression associated with the non-gabapentinoid group (33/102=32.4%) versus 17 episodes of respiratory depression with the gabapentinoid group (17/51=33.3%) (p=0.128, df=2) (Figure 1). When respiratory depression was compared in patients who had sedation and unknown documentation combined, there was also no significant difference between the non-gabapentinoid and gabapentinoid groups (p=1.00, df=1).

Figure 1.

Indication of naloxone use based on the EMR.

Notes: *Pearson χ2 statistical analysis (p=0.128; n=153 episodes of naloxone administration; 17/51 episodes in gabapentinoid group and 33/102 episodes in non-gabapentinoid group for respiratory depression as defined in our study.

Abbreviation: EMR, electronic medical record.

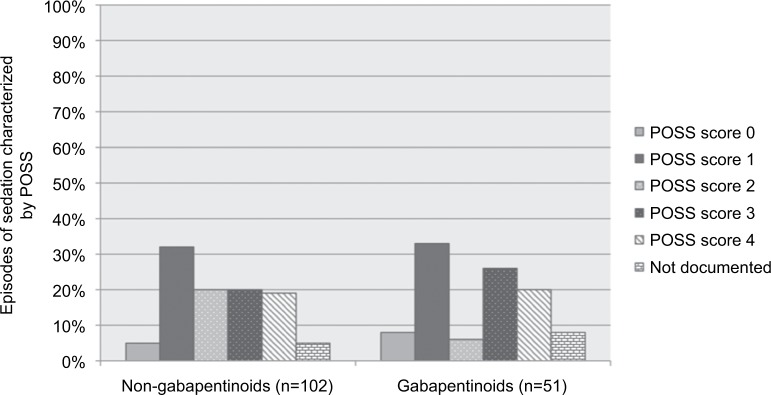

For the secondary objectives, in the non-gabepentinoid group naloxone was administered for sedation in 42% of episodes. In the gabapentinoids group, naloxone was administered for unknown reasons in 39% of episodes (Figure 1). In the non-gabapentinoid group, naloxone was given for a POSS of 3 or 4 (internally defined as sedation in our study) 38.2% of the time versus 45.1% of the time in the gabapentinoid group (p=0.323, df=5) (Figure 2). Even when naloxone administration was compared for those having POSS scores of 0–2, 3–4, and not documented, there was no significant difference (p=0.471, df=2). In the non-gabapentinoid group, the majority of the patients were ≥65 years old (55%), whereas in the gabapentinoid group 33.3% of patients were ≥65 years old (p=0.031). There were 51.7% male in the non-gabapentinoid group and 33.3% male in the gabapentinoid group (p=0.076). The non-gabapentinoid group had significantly more patients who had surgery in the last 24 hours (21.3%) versus the gabapentinoid group (5.5%) (p=0.036). Patients in the gabapentinoid group had similar numbers of patients with CHF (22.2%) and COPD (13.8%) as the non-gabapentinoid group (CHF [16.5%] and COPD [12%]; p=0.611, p=0.776, respectively). The number of patients in the non-gabapentinoid group that had a past medical history of OSA were comparable to those in the gabapentinoid group (11.2 versus 5.5%, respectively, p=0.506). In both groups, a majority of the patients had a GFR >60 mL/min, and about three-quarters of the patients had a GFR at least >30 mL/min (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Episodes of sedation characterized by POSS (n=153 episodes of naloxone administration).

Abbreviation: POSS, Pasero Opioids-induced Sedation Scale.

The average morphine equivalent daily dose in the non-gabapentinoid group was 63.9 mg (±70.5 standard deviation [SD]) versus 89.9 mg (±115 SD) in the gabapentinoid group. The majority of the patients in the gabapentinoid group were prescribed low doses of gabapentinoids (82.4%). In the non-gabapentinoid group, there were 57 episodes (55.8%) involving acute pain, 29 episodes (28.4%) involving chronic pain, and 16 episodes (15.8%) involving an undocumented indication for opioids, while in the gabapentinoid group, there were 31 episodes (60.7%) in which patients had received opioids for acute pain, 15 episodes (29.3%) involving opioids for chronic pain, and 5 episodes (10%) receiving opioids for an undocumented or unclear indication (p=0.436).

Discussion

Overall, among patients who received a combination of opioids and gabapentinoids, respiratory depression did not occur more frequently when compared to opioids alone despite the fact that the gabapentinoid group received higher daily doses of opioids. Although there was no difference observed in the frequency of respiratory depression between the two groups, it was noted that the majority of the patients in the gabapentinoid group received low-dose gabapentinoid. In a previous small cohort study of nine patients, 44% of patients experienced respiratory depression and/or sedation with the combination of gabapentinoids and opioids with dosages of gabapentinoids administered as high as 3,600 mg/d.13 Therefore, higher dosages of gabapentinoids when concomitantly used with opioids may place the patient at a higher risk of developing respiratory depression than the lower dosages of gabapentinoids that were seen in this study. Beyond the scope of this study, it is noted that there have been recent reports of recreational use of gabapentinoids concomitantly with opioids to further enhance drug users’ high experience. Therefore, further studies would be beneficial to evaluate if higher dosages of gabapentinoids when combined with opioids also places these individuals at a higher risk of respiratory depression.

A Joint Commission report indicated that patients are at an increased risk of developing respiratory depression postoperatively.1 Commonly, gabapentinoids are used as perioperative and postoperative adjuvant analgesics to reduce opioid doses.15–17 With this common practice, one case series found that, postoperatively, respiratory depression occurred more frequently with the combination of opioids and gabapentinoids if the patients were older, had OSA, or had poor renal function.16 In our study, the non-gabapentinoids group had significantly more patients with recent surgery than the gabapentinoids group. Additionally, the patients in the gabapentinoids group were younger, with seemingly fewer diagnoses of OSA and chronic kidney disease stage 4 in comparison to those in the non-gabapentinoids group, although this was not statistically significant. The lower frequency of these comorbid conditions in the gabapentinoid group may have contributed to fewer episodes of respiratory depression in comparison to the non-gabapentinoid group.

Respiratory depression has been shown to occur more frequently in patients who have received higher doses of opioids with or without the addition of other sedating medications, especially in the postoperative period.14 Interestingly, in our study, the non-gabapentinoid group had lower daily oral morphine equivalents then the gabapentinoid group. It is unclear why, but this may have been due to other comorbidities that were not accounted for in this study. Some confounding variables that could account for this phenomenon could be that the patients in the non-gabapentinoid group were more likely to be opioid naïve versus opioid tolerant and experienced respiratory depression at lower dosages of opioids. However, it would be anticipated that if patients were opioid naïve, they would be receiving opioids for acute pain; however, there was no greater association of patients in the non-gabapentinoid group receiving opioids for acute versus chronic pain.

This study found that there was no significant difference between respiratory depression and sedation among those who received gabapentinoids and those who did not. Additionally, there was a high percentage of naloxone administration for undocumented indications in both groups (25.5% in the non-gabapentinoid group and 39.1% in the gabapentinoid group). The inability to determine the indication for naloxone administration may have represented gaps in documenting respiratory depression or excessive sedation in the medical record. Lack of documentation may have skewed our data, providing an unclear depiction of the true respiratory depression risk associated with the gabapentinoid group.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the retrospective review which relied on the EMR for data. It was evident in this study that the EMR may not always have provided clear data on the respiratory and sedation status of patients prior to naloxone administration. These potential omissions in documentation may have impacted our results. Additionally, there may be some varying risk of opioid-related respiratory depression depending on the specific opioid and route of delivery. Given the sample size, it was not possible to provide granular analysis for different opioids and delivery routes. As a result, it is possible that differences between the two groups could have influenced the frequency of respiratory depression. Lastly, this study had a small sample size, which limits the generalizability and does not permit the statistical analysis to be performed.

Conclusion

In this retrospective analysis, we showed that there was no greater association of respiratory depression with the concomitant use of opioids and gabapentinoids compared to opioids alone. Further prospective and larger studies are warranted to evaluate the risk of respiratory depression among patients who receive opioids and gabapentinoids, especially in the postoperative setting.

Supplementary material

UCSDH equianalgesic opioid dosing guidelines.

Notes: Text shown in bold, red, or all-capitals is for emphasis. **Indicates the text is a note. ----Indicates not applicable.

Abbreviations: CURES, Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System; IV, intravenous; min, minute; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; PO, per oral; PRN, as needed; q, every; Ref, reference; UCSD, UC San Diego; UCSDH, UC San Diego Health.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to and Shobha Khan, Grace Kuo, Felix Yam, Philip Anderson, Justin Bouw, and the UCSDH Pain Committee for their support and guidance in this project.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.The Joint Commission Sentinel Event Alert. [Accessed August 29, 2016];Safe Use of Opioids in Hospitals. 2012 49:1–5. Available from: https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_49_opioids_8_2_12_final.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pawasauskas J, Stevens B, Youssef R, Kelley M. Predictors of naloxone use for respiratory depression and oversedation in hospitalized adults. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(9):746–750. doi: 10.2146/ajhp130568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yung L, Lee KC, Hsu C, Furnish T, Atayee RS. Patterns of naloxone use in hospitalized patients. Postgrad Med. 2017;129(1):40–45. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2017.1263139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasero C. Assessment of sedation during opioid administration for pain management. J Perianesth Nurs. 2009;24(3):186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nisbet AT, Mooney-cotter F. Comparison of selected sedation scales for reporting opioid-induced sedation assessment. Pain Manag Nurs. 2009;10(3):154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neurontin [package insert] New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyrica [package insert] New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukada C, Kohler JC, Boon H, Austin Z, Krahn M. Prescribing gabapentin off label: perspectives from psychiatry, pain and neurology specialists. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2012;145(6):280–284.e1. doi: 10.3821/145.6.cpj280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mack A. Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9(6):559–568. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.6.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nichols TA. Off-label use of gabapentin for management of alcohol use disorders. Menthal Health Clin. 2015;5(6):248–252. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zacny JP, Paice JA, Coalson DW. Subjective, psychomotor, and physiological effects of pregabalin alone and in combination with oxycodone in healthy volunteers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2012;100(3):560–565. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millar J, Sadasivan S, Weatherup N, Lutton S. Lyrica nights-recreational pregabalin abuse in an Urban Emergency Department. Emerg Med J. 2013;30:874. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meisenberg B, Ness J, Rao S, Rhule J, Ley C. Implementation of solutions to reduce opioid-induced oversedation and respiratory depression. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(3):162–169. doi: 10.2146/ajhp160208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keskinbora K, Pekel AF, Aydinli I. Gabapentin and an opioid combination versus opioid alone for the management of neuropathic cancer pain: a randomized open trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(2):183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng PW, Wijeysundera DN, Li CC. Use of gabapentin for perioperative pain control – a meta-analysis. Pain Res Manag. 2007;12(2):85–92. doi: 10.1155/2007/840572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eipe N, Penning J. Postoperative respiratory depression with pregabalin: a case series and a preoperative decision algorithm. Pain Res Manag. 2011;16:353–356. doi: 10.1155/2011/561604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weingarten TN, Herasevich V, Mcglinch MC, et al. Predictors of delayed postoperative respiratory depression assessed from naloxone administration. Anesth Analg. 2015;121(2):422–429. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

UCSDH equianalgesic opioid dosing guidelines.

Notes: Text shown in bold, red, or all-capitals is for emphasis. **Indicates the text is a note. ----Indicates not applicable.

Abbreviations: CURES, Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System; IV, intravenous; min, minute; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; PO, per oral; PRN, as needed; q, every; Ref, reference; UCSD, UC San Diego; UCSDH, UC San Diego Health.