Abstract

Case summary

A 6-year-old female neutered domestic shorthair cat from Cyprus was presented with multiple ulcerated skin nodules. Cytology and histopathology of the lesions revealed granulomatous dermatitis with intracytoplasmic organisms, consistent with amastigotes of Leishmania species. Biochemistry identified a mild hyperproteinaemia. Blood extraction and PCR detected Leishmania species, Hepatozoon species and ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum’ (CMhm) DNA. Subsequent sequencing identified Hepatozoon felis. Additionally, the rRNA internal transcribed spacer 1 locus of Leishmania infantum was partially sequenced and phylogeny showed it to cluster with species derived from dogs in Italy and Uzbekistan, and a human in France. Allopurinol treatment was administered for 6 months. Clinical signs resolved in the second month of treatment with no deterioration 8 months post-treatment cessation. Quantitative PCR and ELISA were used to monitor L infantum blood DNA and antibody levels. The cat had high L infantum DNA levels pretreatment that gradually declined during treatment but increased 8 months post-treatment cessation. Similarly, ELISA revealed high levels of antibodies pretreatment, which gradually declined during treatment and increased slightly 8 months post-treatment cessation. The cat remained PCR positive for CMhm and Hepatozoon species throughout the study. There was no clinical evidence of relapse 24 months post-treatment.

Relevance and novel information

To our knowledge, this is the first clinical report of a cat with leishmaniosis with H felis and CMhm coinfections. The high L infantum DNA levels post-treatment cessation might indicate that although the lesions had resolved, prolonged or an alternative treatment could have been considered.

Introduction

Leishmania infantum, the causative agent of canine leishmaniosis in Europe and a zoonotic vector-borne pathogen, has been increasingly reported in cats in the Mediterranean basin, providing mounting evidence that cats may act as a secondary reservoir.1 Experimental and case-control studies on feline leishmaniosis (FeL) are lacking, limiting our knowledge of this disease; thus epidemiological studies, case series and case descriptions are required to establish a better understanding of the clinicopathological presentations, treatment, monitoring and prevention of FeL.2

Herein, we describe the clinical, laboratory and molecular findings, as well as treatment and prolonged monitoring data, from an adult domestic shorthair cat from Cyprus diagnosed with leishmaniosis caused by Leishmania infantum and coinfections with Hepatozoon felis and ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum’ (CMhm).

Case description

A 6-year-old female neutered domestic shorthair cat was presented at the end of September 2014 to Cyvets Veterinary Centre, Paphos, Cyprus, owing to multiple ulcerated skin nodules on the forelimbs noted by the owner 1 day before presentation when the cat had returned having been missing for 2 weeks. The cat lived mainly outdoors in a rural area, had no travel history, was fully vaccinated and had occasional fipronil spot-on (Effipro; Virbac) ectoparasiticide application.

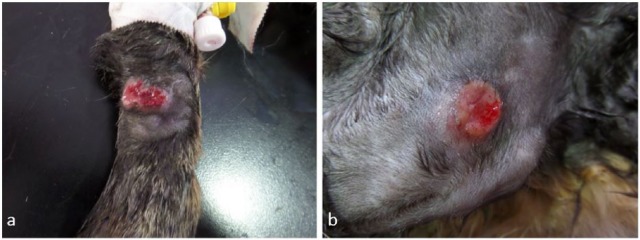

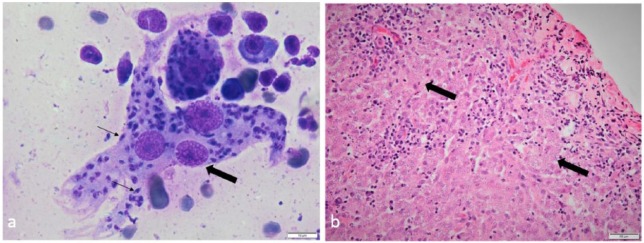

At presentation, the cat’s body condition score was 5/9 and the only abnormalities detected were three round, ulcerated skin nodules; two of them were on the dorsal aspect of each forelimb, above the carpus (Figure 1a) and the third was on the left scapula (Figure 1b). Owing to a recent diagnosis of cutaneous leprosy in a different cat from the same household, the lesion from the scapula was surgically excised for histopathological examination and imprint smears from one of the forelimb lesions were made for cytological examination. The latter revealed high numbers of macrophages, with an epithelioid appearance and occasional giant multinucleated macrophages, as well as low numbers of plasma cells and small lymphocytes. Numerous organisms consistent with Leishmania species amastigotes were noted in parasitophorous vacuoles of the macrophages and freely in the background (Figure 2a). Histopathological examination of the lesion (Figure 2b) revealed mild acanthosis and focal ulceration of the epidermis. Within the subjacent dermis, extending from the denuded surface to the deep dermis/panniculus, was an irregular, densely cellular area composed of macrophages, with low numbers of multinucleated forms. The macrophages contained numerous intracytoplasmic vacuoles (5–7 μm in diameter) within which were densely amphophilic round-to-oval organisms (approximately 1 μm diameter). The macrophages were mostly in random array; rarely groups of the cells were aggregated to form small granulomas. There were lighter admixtures of neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells. The cytological and histopathological diagnosis was granulomatous dermatitis with intralesional intracytoplasmic amastigotes consistent with Leishmania species.

Figure 1.

Ulcerated cutaneous skin nodules on the (a) left forelimb and (b) left scapula, month 0

Figure 2.

(a) Imprint smears from an ulcerated skin nodule revealed multinucleated macrophages (large arrow) with numerous intracellular organisms consistent with Leishmania species amastigotes (small arrows). Diff-Quik stain, scale bar = 10 μm. (b) Histopathological examination of a section of the nodule removed from the left scapula showed marked granulomatous dermatitis with intracytoplasmic organisms consistent with Leishmania species amastigotes in the macrophages (arrows). Haematoxylin and eosin stain, scale bar = 50 μm

Blood samples were collected into EDTA and heparin and analysed by an automated haematology impedance analyser (Vet ABC; Scil) and by a VetScan VS2 chemistry analyser (Abaxis), respectively. Only mild hyperproteinaemia (84.0 g/l; reference interval 54–82 g/l) was present. Blood smear examination and urine analysis were unremarkable.

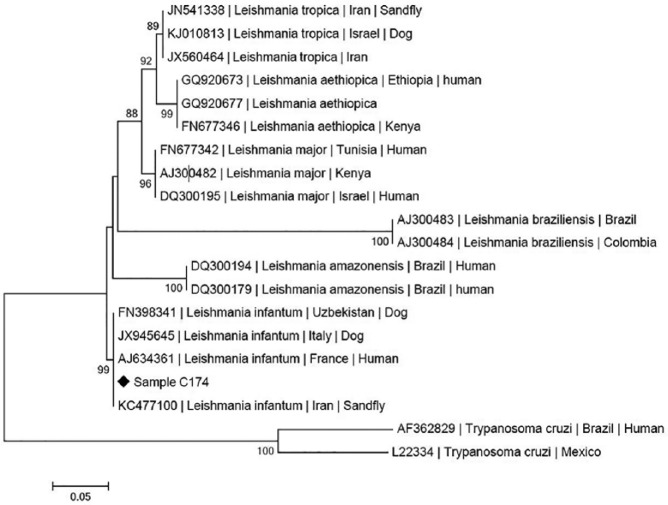

The cat was also enrolled into an epidemiology study,3 thus surplus EDTA-blood and plasma available were submitted for testing for the presence of infectious, including vector-borne, organisms. The cat was PCR positive for Hepatozoon species using conventional PCR, as well as positive for Leishmania species and CMhm using quantitative PCR (qPCR). Subsequent sequencing identified H felis and L infantum.3 Owing to the small size of the amplicon generated by the initial Leishmania species PCR4 an additional PCR was performed, targeting the rRNA ITS1 locus of L infantum,5 followed by sequencing. The forward and reverse sequences of the L infantum were assembled and constructed into a consensus sequence, which was deposited in the GenBank database (MF140257). The DNA sequence was 100% identical to a partial 18S rRNA ITS1 sequence of L infantum (GenBank KX664454) over 258 bp, as found by BLAST analysis (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). Phylogeny (Figure 3) showed the L infantum from this Cypriot cat to cluster with species derived from dogs in Italy and Uzbekistan, a sandfly in Iran and a human in France. The cat was PCR negative for Mycoplasma haemofelis, ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis’ (CMt), Bartonella henselae and Ehrlichia/Anaplasma species, and seronegative for feline leukaemia virus antigen and feline immunodeficiency virus antibodies.

Figure 3.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Leishmania genera, based on rRNA ITS1 locus sequences and showing the position of the sequence derived from the Leishmania species found in the blood in the Cypriot cat (sample C174) with clinical leishmaniosis described in this report (MF140257). Species and strains are listed, followed by their GenBank accession numbers

Treatment with allopurinol at 10 mg/kg PO q12h was started (month 0) and administered for 6 months. The cat was examined every 2 months during treatment and then 8 months post-treatment cessation (month 14), with blood samples collected each time for haematology and biochemistry analysis. An ELISA was used to monitor L infantum-specific antibodies in serum,6 as well as qPCR4 for calculating the L infantum DNA levels in the blood as previously described (Table 1).7 The L infantum DNA level of the surgically excised skin nodule was high (approximately 3.48 × 1010 relative copy numbers). Additionally, PCR assays were repeated for CMhm and Hepatozoon species.

Table 1.

Serological and PCR results of Leishmania infantum in a cat with clinical leishmaniosis and coinfections with Hepatozoon felis and ‘Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum’ during and after treatment with allopurinol at 10 mg/kg PO q12h for 6 months, which was started at month 0

| Leishmania infantum | Month 0 (pretreatment) |

Month 2 (clinical resolution of lesions) |

Month 4 | Month 6 (treatment cessation) |

Month 14 (8 months post-treatment cessation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA level per PCR assay (relative copy numbers) | 663,600 | 17,300 | 500 | 130 | 64,600 |

| ELISA units (EU), cut off point for negative result is 9.2 EU | 163 | 124 | 57 | 99 | 107 |

The clinical signs gradually improved by month 1 (Figure 4a) and resolved by month 2, with no clinical relapses evident at the completion of treatment (Figure 4b) nor up until the end of the follow-up period at month 14.

Figure 4.

Skin lesion (arrow) on the left forelimb (a) at month 1 and (b) at month 6 (treatment cessation)

The cat had high L infantum DNA and antibody levels pretreatment at month 0. This DNA level had decreased by approximately 40-fold at month 2, and by approximately 5000-fold at month 6, compared with month 0. At month 14 the L infantum DNA level had approximately a 500-fold increase compared with month 6. The L infantum antibodies showed a more subtle gradual decrease, reaching a nadir at month 4, with approximately a three-fold decrease compared with month 0. From months 6 – 14 the antibodies remained at similar levels with approximately a two-fold elevation compared with the levels at month 4.

The cat remained PCR positive for CMhm and Hepatozoon species throughout the study and apart from the initial hyperproteinaemia, which resolved during month 2, no other haematological or biochemical abnormalities were detected. At month 30, while no PCR was performed, the cat remained clinically healthy with no evidence of clinical signs or relapse.

Discussion

The first case of FeL was reported in 1912 in Algeria,8 and it was not until the past two decades that case reports and epidemiological studies established a description of clinical FeL including skin or mucocutaneous lesions and lymphadenomegaly.1 In contrast, fewer data are available regarding the treatment, monitoring and prognosis of FeL.

The LeishVet Group1 and the Advisory Board on Cat Diseases Guidelines9 both recommend allopurinol treatment (10–20 mg/kg q24h or q12h) for FeL, based on the extensive clinical use of this medication in previous cases. In contrast, meglumine antimoniate has only been described in a few cases of FeL.10,11 Additionally, a combination of allopurinol and N-methyl-glucamine antimoniate in a cat with FeL due to L infantum was reported to have led to successful clinical resolution and significant reduction of the parasitic load, suggesting that this therapeutic protocol could also be considered for FeL.12

The cat in this case had complete clinical resolution of the cutaneous lesions during the treatment period with no relapse by month 24 after completion of the 6 months of allopurinol treatment. However, the PCR results post-treatment showed that elimination of L infantum had not occurred, indicating progressive subclinical infection. Given the potential role of the cat as a secondary reservoir and the zoonotic nature of L infantum, an alternative treatment could have been implemented for this patient, such as a combination of allopurinol with meglumine antimoniate or N-methyl-glucamine antimoniate.

There are only a few case reports that provided prolonged follow-up for FeL,12–15 and only in one case did this comprise measurement of L infantum DNA levels and serology.12 In the current case, while the ELISA results followed a similar pattern to the DNA levels during treatment, they both failed to do the same during the monitoring period, in which the clinical signs resolved but parasitaemia persisted (Table 1). Persichetti et al reported in a recent study that although ELISA serology was better for diagnosing clinical FeL compared with the immunofluorescent antibody test (IFAT), the latter was more sensitive than ELISA to detect subclinical infection.16 The same study also recommended Western blot as the preferable serological test for FeL since it yielded a higher sensitivity and specificity in comparison to ELISA and IFAT.

The pathogens infecting this cat were recently found to have a PCR prevalence of 3.1% for L infantum, 58.0% for Hepatozoon species and 33.0% for CMhm in non-healthy Cypriot cats,3 with L infantum and Hepatozoon canis also being reported in the canine population of this island.17 Significant associations between L infantum infection and H felis and CMt infections in cats using multivariable logistic regression have been reported, suggesting impaired host immune response due to the multiple coinfections.3 This could have been a component leading to the persistent L infantum parasitaemia in this cat in the face of the Hepatozoon species and CMhm coinfections.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical report of FeL caused by L infantum, with H felis and CMhm coinfection. While allopurinol treatment led to a complete resolution of the clinical signs, it failed to eliminate the parasite, leading to persistent L infantum subclinical infection. Thus, more aggressive treatment could be considered in future cases, potentially with the combination of allopurinol with meglumine antimoniate or N-methyl-glucamine antimoniate, in order to achieve a more efficient control of L infantum.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the veterinarian Dr Tryfon A Chochlios, from Cyvets Veterinary Centre, Paphos, Cyprus, for aiding in the collection of follow-up clinical records.

Footnotes

Author note: The work described in this paper was presented at the 2017 ACVP/ASVCP Concurrent Annual Meeting in Vancouver as an oral presentation.

Conflict of interest: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors for the preparation of this case report.

Accepted: 9 October 2017

References

- 1. Pennisi MG, Cardoso L, Baneth G, et al. LeishVet update and recommendations on feline leishmaniosis. Parasit Vectors 2015; 8: 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Soares CS, Duarte SC, Sousa SR. What do we know about feline leishmaniosis? J Feline Med Surg 2016; 18: 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Attipa C, Papasouliotis K, Solano-Gallego L, et al. Prevalence study and risk factor analysis of selected bacterial, protozoal and viral, including vector-borne, pathogens in cats from Cyprus. Parasit Vectors 2017; 10: 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shaw SE, Langton DA, Hillman TJ. Canine leishmaniosis in the United Kingdom: a zoonotic disease waiting for a vector? Vet Parasitol 2009; 163: 281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Talmi-Frank D, Nasereddin A, Schnur LF, et al. Detection and identification of old world Leishmania by high resolution melt analysis. PLOS Negl Trop Dis 2010; 4: e581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Solano-Gallego L, Rodríguez-Cortés A, Iniesta L, et al. Cross-sectional serosurvey of feline leishmaniasis in ecoregions around the Northwestern Mediterranean. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76: 676–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Porter E, Tasker S, Day MJ, et al. Amino acid changes in the spike protein of feline coronavirus correlate with systemic spread of virus from the intestine and not with feline infectious peritonitis. Vet Res 2014; 45: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sergent E, Sergent E, Lombard J, Quilichini M. La leishmaniose à Alger. Infection simultanée d’un enfant, d’un chien et d’un chat dans la même habitation. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 1912; 5: 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pennisi MG, Hartmann K, Lloret A, et al. Leishmaniosis in cats: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 638–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Costa-Durão J, Rebelo E, Peleteiro M, et al. Primeiro caso de leishmaniose em gato doméstico (Felis catus domesticus) detectado em Portugal (Concelho de Sesimbra). Nota preliminar. Rev Port Cienc Vet 1994; 89: 140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hervás J, Lara FC-MD, Sánchez-Isarria MA, et al. Two cases of feline visceral and cutaneous leishmaniosis in Spain. J Feline Med Surg 1999; 1: 101–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Basso MA, Marques C, Santos M, et al. Successful treatment of feline leishmaniosis using a combination of allopurinol and N-methyl-glucamine antimoniate. JFMS Open Rep 2016; 2: 205511691663000 DOI: 10.1177/2055116916630002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maroli M, Pennisi MG, Di Muccio T, et al. Infection of sandflies by a cat naturally infected with Leishmania infantum. Vet Parasitol 2007; 145: 357–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pennisi MG, Venza M, Reale S, et al. Case report of leishmaniasis in four cats. Vet Res Commun 2004; 28: 363–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Richter M, Schaarschmidt K, Krudewig C. Ocular signs, diagnosis and long-term treatment with allopurinol in a cat with leishmaniasis. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2014; 156: 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Persichetti MF, Solano-Gallego L, Vullo A, et al. Diagnostic performance of ELISA, IFAT and Western blot for the detection of anti-Leishmania infantum antibodies in cats using a Bayesian analysis without a gold standard. Parasit Vectors 2017; 10: 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Attipa C, Hicks CA, Barker EN, et al. Canine tick-borne pathogens in Cyprus and a unique canine case of multiple co-infections. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2017; 8: 341–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]