Significance

In this report, we provide evidence of a mechanistic link between antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-induced neutrophil activation, regulated necrosis (necroptosis), generation of neutrophil extracellular traps, complement activation, and endothelial cell damage with consecutive vasculitis and glomerulonephritis in autoimmune ANCA-induced vasculitis (AAV). We now show that inhibition of necroptosis-inducing kinases completely prevents ANCA vasculitis and establish a link to activation of the complement system. We suggest that these findings significantly extend our understanding of the pathogenesis of AAV and especially the tight regulation of neutrophil cell death therein. In addition, specific necroptosis inhibitors are currently being evaluated in clinical studies and can possibly complement existing therapeutic strategies in AAV.

Keywords: ANCA, NETs, necroptosis, complement, glomerulonephritis

Abstract

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) constitutes life-threatening autoimmune diseases affecting every organ, including the kidneys, where they cause necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis. ANCA activates neutrophils and activated neutrophils damage the endothelium, leading to vascular inflammation and necrosis. Better understanding of neutrophil-mediated AAV disease mechanisms may reveal novel treatment strategies. Here we report that ANCA induces neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) via receptor-interacting protein kinase (RIPK) 1/3- and mixed-lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL)-dependent necroptosis. NETs from ANCA-stimulated neutrophils caused endothelial cell (EC) damage in vitro. This effect was prevented by (i) pharmacologic inhibition of RIPK1 or (ii) enzymatic NET degradation. The alternative complement pathway (AP) was recently implicated in AAV, and C5a inhibition is currently being tested in clinical studies. We observed that NETs provided a scaffold for AP activation that in turn contributed to EC damage. We further established the in vivo relevance of NETs and the requirement of RIPK1/3/MLKL-dependent necroptosis, specifically in the bone marrow-derived compartment, for disease induction using murine AAV models and in human kidney biopsies. In summary, we identified a mechanistic link between ANCA-induced neutrophil activation, necroptosis, NETs, the AP, and endothelial damage. RIPK1 inhibitors are currently being evaluated in clinical trials and exhibit a novel therapeutic strategy in AAV.

Systemic necrotizing autoimmune vasculitis is characterized by circulating antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) that recognizes either proteinase 3 (PR3) or myeloperoxidase (MPO). Both antigens are exclusively expressed by neutrophils and monocytes (1–5). In vitro studies characterized various ANCA-induced neutrophil effector functions that participate in endothelial damage, such as adhesion, granule protein release, respiratory burst, and cytokine generation (reviewed in refs. 6 and 7). Subsequently, animal studies provided mechanistic insights under complex in vivo conditions. Activation of the alternative complement pathway (AP) together with C5a receptor blockade is one such example that was primarily derived from animal studies (8–11). A more recently described neutrophil effector function is the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) (12–16). Mechanisms controlling NET formation and the clinical relevance of NETs are intensively studied. NETs are lattice-like structures containing DNA, histones, and neutrophil granule proteins, including the ANCA antigens MPO and PR3 (12, 17, 18). ANCA-stimulated neutrophils were shown to release NETs in vitro, and circulating as well as glomerular deposited NETs were detected in AAV patients (12, 19–21). It was suggested that NETs are immunogenic and participate in the tolerance breakdown toward the ANCA autoantigens (12, 22, 23). In addition, it is conceivable that ANCA-induced NETs participate in the vascular injury process that culminates in necrotizing vasculitis. However, neither the signaling pathways by which ANCA induces NETs nor the potential mechanism(s) by which NETs affect the endothelium are fully understood. We hypothesized that receptor-interacting protein kinases (RIPKs) 1/3, involved in the necroptosis signaling pathway, control ANCA-induced NET generation, and studied NET-mediated endothelial cell (EC) damage mechanisms.

Results

ANCA Stimulation Causes NET Formation, and the RIPK1/3- and Mixed-Lineage Kinase Domain-Like Protein-Dependent Necroptosis Pathway Mediates This Effect.

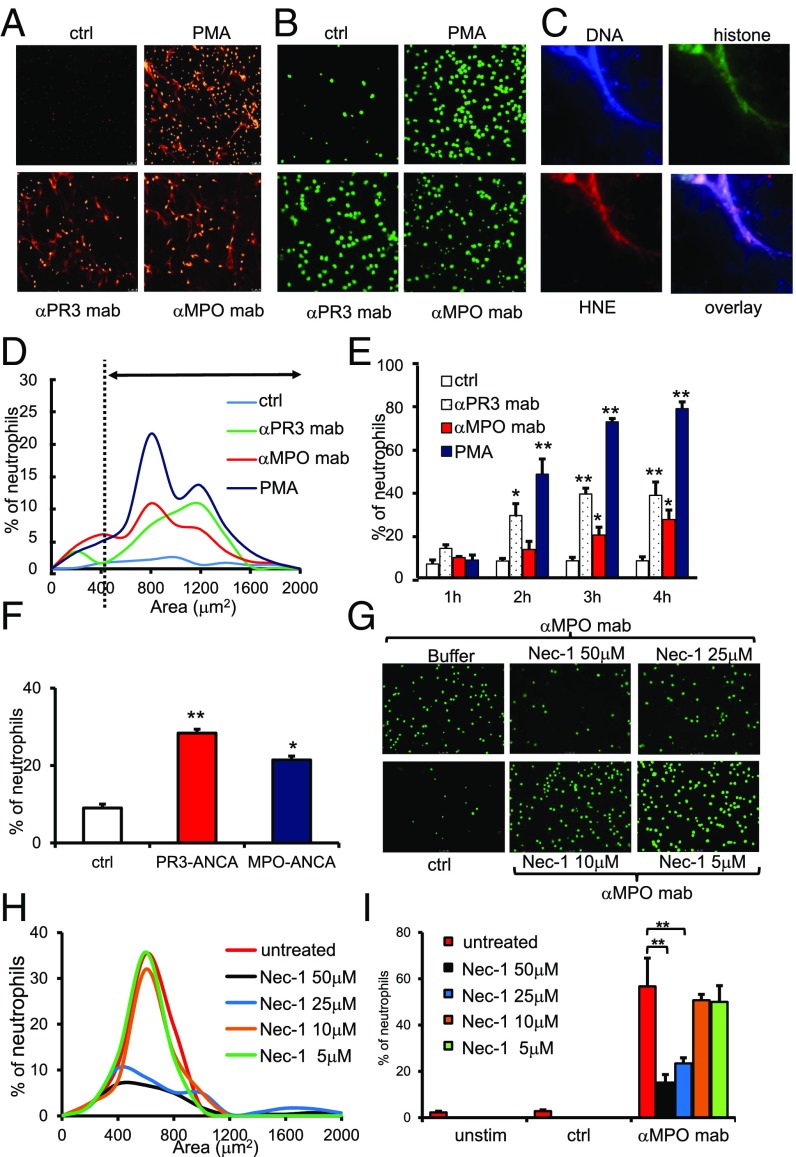

Both monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to the ANCA antigens PR3 and MPO and ANCA-IgG from AAV patients induced NET formation in TNFα-primed human neutrophils (Fig. 1 A–F). Using the cell-impermeable DNA dye propidium iodide, we detected extracellular DNA with the typical filiform NET structures when samples were paraformaldehyde (PFA)-fixed (Fig. 1A), and observed typical extracellular DNA circles that surround neutrophils when unfixed samples were stained with Sytox green (Fig. 1B). Recently, critical NET-related issues were raised, including the need to define NETs by their characteristic composition, use observer-independent quantification methods, identify the upstream pathways that control NET formation in response to a given stimulus, determine the ways by which NETs cause tissue damage, and use physiologic stimuli with clinical relevance rather than artificial phorbol ester (24). ANCA provides such a disease-relevant NET inducer, and ANCA-induced NETs show the characteristic composition of DNA, histones, and human neutrophil elastase (HNE) (Fig. 1C). Quantitative assessment of NETs using an automated and observer-independent method described by Papayannopoulos et al. (25) indicated that ANCA increased both the percentage of NET-producing cells and the DNA areas surrounding the neutrophils (Fig. 1D). While analyzing NET formation at 1-h intervals up to 4 h, we observed that up to 40% of neutrophils produced NETs in response to anti-PR3 and anti-MPO mAbs by the end of the observation period (Fig. 1E). Incubation of polymorphonuclear neutrophil with IgG purified from patients with active AAV resulted in NET formation, whereas control IgG isolated from healthy controls did not (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

ANCA induces NET generation in human neutrophils by RIPK1-dependent necroptosis signaling. Isolated human neutrophils were primed with 2 ng/mL TNFα and subsequently stimulated with different monoclonal antibodies (ctrl, isotype control; αPR3 mab, monoclonal antibody to PR3; αMPO mab, monoclonal antibody to MPO). (A) PFA-fixed cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) to detect NETs. (B) Viable cells were stained with Sytox green to detect NETs. (C) A typical example of anti-MPO mAb-induced NETs with strong staining for DNA (blue; DAPI), histone H3 (green), and HNE (red) is depicted. (D) Automated quantification of NET generation in response to mAbs to MPO and PR3, PMA, and isotype control mAb (ctrl) (one representative experiment is shown). The dashed line marks the threshhold for definition of NETs generation. (E) Time course of NET formation in response to mAbs to MPO and PR3, PMA, and isotype control mAb; n = 4 experiments with different neutrophil donors. (F) Stimulation of TNFα-primed neutrophils with two different human control IgG preparations for 4 h (ctrl), two different human PR3-ANCA IgG preparations, and two different human MPO-ANCA IgG preparations (125 μg/mL); n = 4 experiments with different neutrophil donors. (G) αMPO mAb-induced NET generation by microscopy was dose dependently reduced by necrostatin-1 preincubation. (H) Depiction of the percentage of NET-producing neutrophils and NET area. (I) Statistical analysis of the percentage of NET-producing neutrophils from four independent experiments with different neutrophil donors as in H. Error bars indicate means ± SEM. Comparisons were made using t test or ANOVA; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

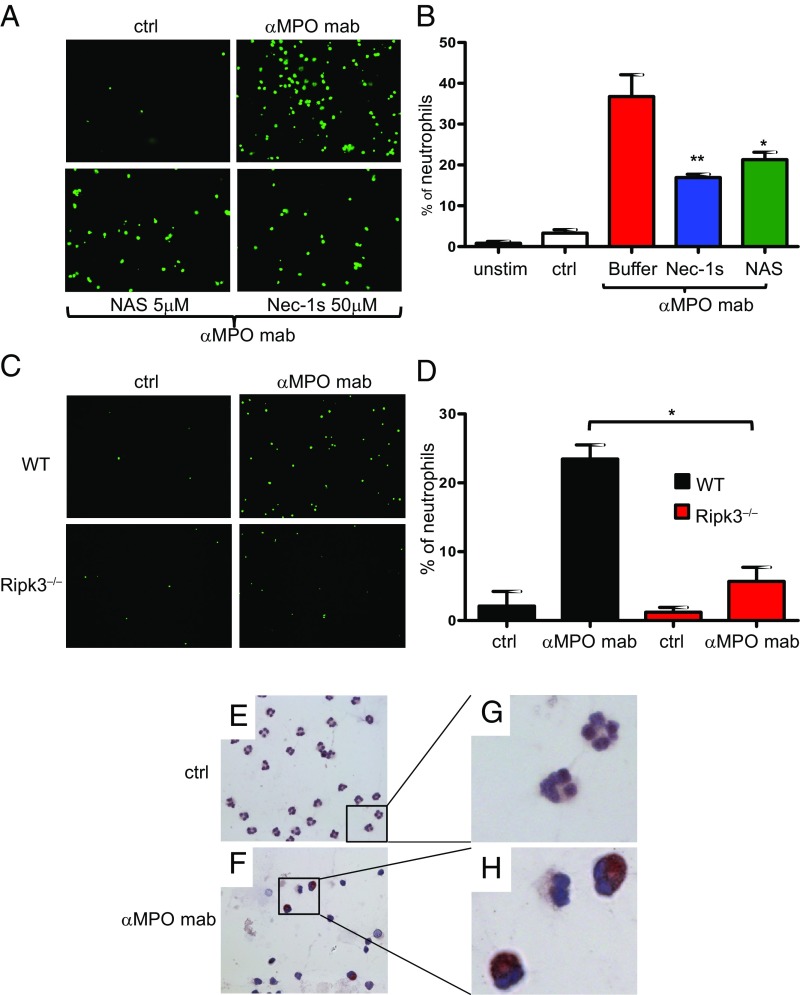

The pathway(s) that controls ANCA-induced NET formation is not known. NET formation may occur in vital neutrophils (26) or as a consequence of regulated necrosis (27, 28). Necroptosis, the best-studied form of regulated necrosis, depends on RIPK1/3 activation and subsequent phosphorylation of the pseudokinase mixed-lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) (reviewed in ref. 29). Activation of RIPK3 is prevented by an inactivating conformation of RIPK1 that is maintained by the small molecule necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) or its derivatives (necrostatins) (30). We tested the hypothesis that necroptosis represents the upstream stimulus that drives ANCA-mediated NET formation. Increasing Nec-1 concentrations decreased NET production, as assessed by microscopy (Fig. 1G) and automated quantification (Fig. 1 H and I). Significant reduction of NET generation was also observed with the highly specific pharmacologic RIPK1 inhibitor Nec-1s as well as with the downstream MLKL inhibitor necrosulfonamide (Fig. 2 A and B). Using a genetic approach, neutrophils from RIPK3-deficient mice exhibited reduced NET generation in response to polyclonal anti-MPO IgG (Fig. 2 C and D). Finally, we observed a clearly positive p-MLKL signal in anti-MPO antibody-stimulated human neutrophils that was absent in control antibody-stimulated cells (Fig. 2 E–H). Together, these data indicate that RIPK3-dependent necroptosis functions as an upstream activator of ANCA-induced NET generation.

Fig. 2.

ANCA induces NET generation in human and murine neutrophils by RIPK1- and MLKL-dependent necroptosis signaling. (A) Isolated TNFα-primed human neutrophils were stimulated with a monoclonal antibody to MPO (αMPO mab) or an isotype control (ctrl). NETs were detected by Sytox green staining. NET generation was reduced by both necrostatin-1s and necrosulfonamide (NAS) preincubation. (B) Corresponding statistical analysis of the percentage of NET-producing neutrophils from three independent experiments with different neutrophil donors. (C) Isolated TNFα-primed murine neutrophils from WT or Ripk3−/− mice were stimulated with murine polyclonal anti-MPO IgG, and NET generation was quantified by Sytox green staining. Neutrophils from Ripk3−/− mice displayed reduced NET generation. (D) Corresponding statistical analysis of the percentage of NET-producing neutrophils from three independent experiments. (E–H) p-MLKL immunohistochemistry on isolated human neutrophils. αMPO mAb-stimulated TNFα-primed neutrophils displayed a strong p-MLKL signal that was absent in isotype control-stimulated cells; E and F show 63× magnification. G and H depict higher digital magnification of the marked areas in E and F. Error bars indicate means ± SEM. Comparisons were made using t test or ANOVA; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

NETs Cause Endothelial Cell Damage, and NET-Dependent Alternative Complement Pathway Activation Contributes to This Effect.

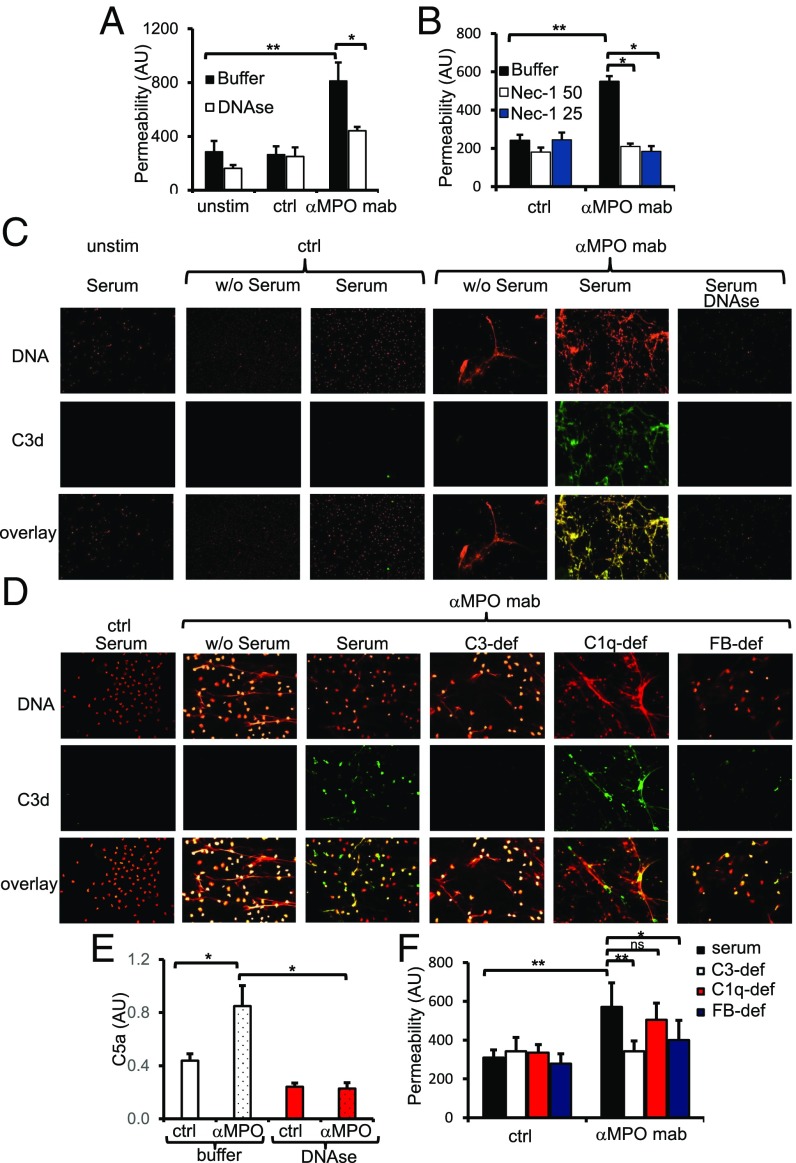

EC damage by ANCA-activated neutrophils is a hallmark of AAV. To test whether or not NETs damage the endothelium directly, we incubated NETs isolated from anti-MPO mAb-treated neutrophils with EC monolayers in the presence of serum. Using albumin flux across the EC monolayer as an indicator of EC damage, we observed increased albumin permeability with NETs from anti-MPO mAb-treated neutrophils (Fig. 3 A and B). We evaluated the capability of NETs to damage EC by two different approaches: either by NETs degradation with DNAse I (Fig. 3A) or by specific necroptosis inhibition with Nec-1. Both of these approaches strongly protected EC from NETs-induced damage (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Endothelial damage and complement activation by ANCA-induced NET generation. (A) HUVECs were coincubated with NETs isolated from either TNFα-primed human neutrophils without further stimulation (unstim), isotype mAb-stimulated (ctrl), or αMPO mAb-stimulated (αMPO) neutrophils. Permeability of the EC monolayer was measured after 1 h using albumin-FITC. NET degradation by DNase protected from endothelial damage. (B) Human neutrophil preincubation with Nec-1 protected from NET-induced endothelial damage. (C) NETs were coincubated in the absence (w/o) or presence of human serum and stained after PFA fixation with PI (DNA; red) and αC3d antibody (FITC; green). Unstimulated cells and isotype-stimulated neutrophils displayed no NETs and no C3d deposition, whereas αMPO mAb-stimulated cells coincubated with serum showed NET formation with strong C3d costaining. DNase pretreatment prevented C3d staining. A typical example is depicted. (D) NETs were coincubated with different human sera as indicated and stained after fixation with PI (DNA; red) and αC3d antibody (FITC; green). Isotype-stimulated neutrophils displayed no NETs and no C3d deposition; αMPO mAb-stimulated neutrophils displayed NET formation and—when coincubated with serum—C3d deposition. C3d deposition was not affected by C1q deficiency but strongly reduced in both C3-deficient (C3-def) and complement factor B-deficient (FB-def) sera. (E) αMPO mAb-induced NETs that were coincubated with human serum caused complement activation with C5a generation. The effect was prevented by NET degradation using DNase I. (F) Increased EC permeability by αMPO mAb-induced NETs is mediated by the alternative complement pathway, as both C3-deficient and complement factor B-deficient sera provided protection whereas C1q deficiency did not. Error bars indicate means ± SEM. Comparisons were made using t test or ANOVA; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ns, not significant.

We and others showed recently that AP activation caused necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis (NCGN) in murine AAV disease models (8–11). C5a was characterized as an important mediator, and an oral C5a receptor blocker was subsequently established and is currently being evaluated as a treatment target in clinical studies (31). We argued that NETs provide a scaffold for complement activation. We therefore activated TNFα-primed neutrophils with mAbs to MPO or an isotype control for 3 h in HBSS before addition of human serum as a complement source for the last hour of the experiment. After 4 h, NETs were isolated, and the NET components were released by DNase I and subjected to C5a ELISA. We detected C5a generation in anti-MPO mAb-induced NETs that was abrogated by DNase I (Fig. 3E). As an alternative approach, we visualized complement activation by C3d staining and observed that anti-MPO mAb-induced NETs showed strong C3d staining with DNA colocalization in the presence of normal serum. This effect was reversed upon addition of serum and upon DNA degradation by DNase I (Fig. 3C). We then characterized the serum complement components that were required for NET-mediated complement activation and EC damage using sera with defined complement deficiencies. We observed again strong C3d staining in anti-MPO mAb-induced NETs that colocalized with DNA under normal human serum conditions but strongly diminished C3d staining when C3-deficient or factor B-deficient sera were used (Fig. 3D). In contrast, C1q deficiency had no effect on C3d staining. Thus, NETs provide a scaffold for AP activation but not for the classical complement pathway. Importantly, anti-MPO mAb-induced NETs that were generated in C3- or factor B-deficient sera provoked significantly less EC damage compared with NETs produced in normal or C1q-deficient sera (Fig. 3F). In summary, these data identify the interconnection between ANCA-induced neutrophil activation, NETs, the AP, and EC damage.

ANCA-Induced NETs Mediate Anti-MPO–Induced Glomerular Damage.

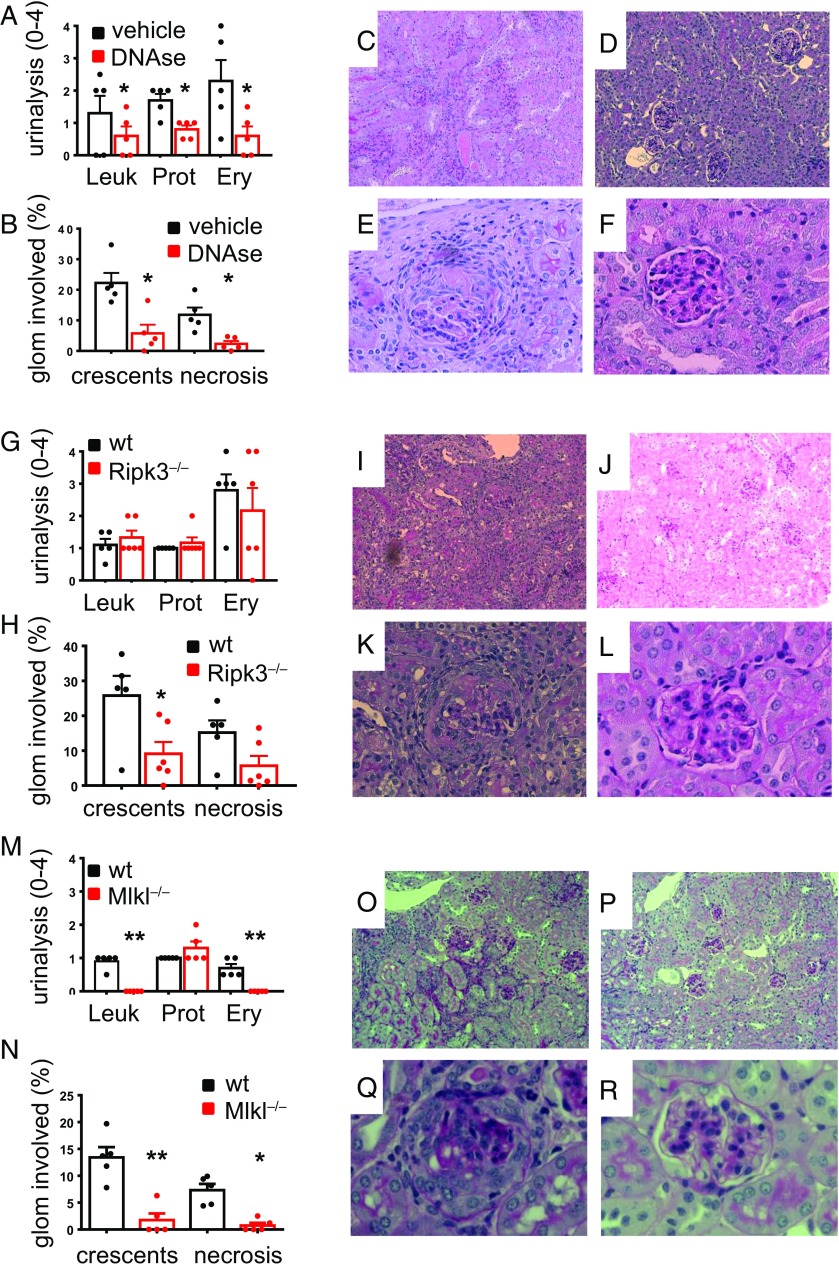

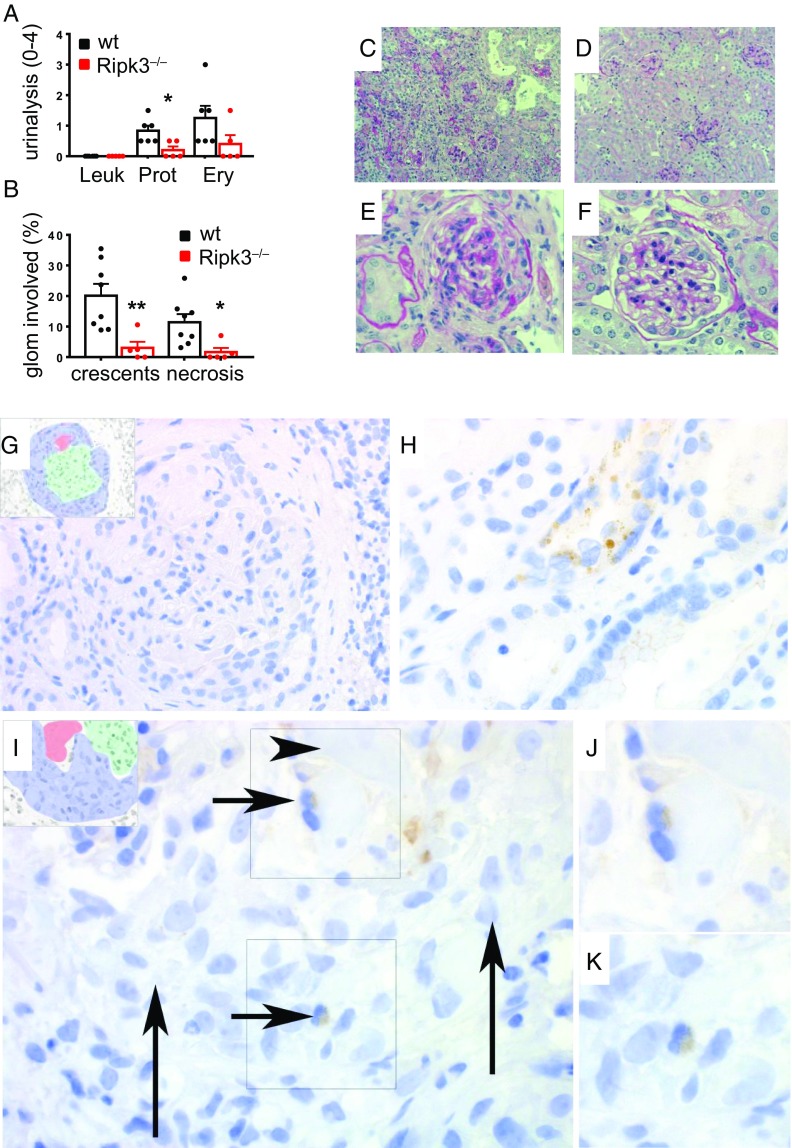

Finally, we tested the key events from our in vitro observations in two murine AAV disease models. First, we used a passive anti-MPO Ab transfer model to induce NCGN and evaluate the effect of DNase I treatment. IgG was prepared from MPO-deficient mice that were immunized with murine MPO and transferred into wild-type (WT) mice. After 7 d, all vehicle-treated mice showed proteinuria, erythrocyturia, and leukocyturia by dipstick (Fig. 4A) as well as glomerular crescents and necrosis by histology (Fig. 4 B, C, and E). Importantly, i.v. DNase I treatment, started 24 h after anti-MPO Ab transfer, protected mice from the disease (Fig. 4 A, B, D, and F), supporting the notion that NETs contribute to glomerular endothelial injury in vivo. However, we cannot rule out that DNase had additional effects independent of NET degradation. Thus, we used a different intervention by genetically interfering with the necroptosis pathway. We induced disease in WT and RIPK3-deficient mice by passive anti-MPO Ab transfer and found that RIPK3 deficiency prevented NCGN by renal pathology (Fig. 4 H–L). To exclude nonnecroptotic functions of RIPK3 (32, 33), we added another approach and induced disease in WT and MLKL-deficient mice. We observed that MLKL deficiency protected from NCGN, thereby definitively implicating necroptosis as an important disease mechanism (Fig. 4 M–R). Urine analysis showed less protection with RIPK3 compared with MLKL deficiency, suggesting RIPK3-independent effects on MLKL that may contribute to the pathogenesis. However, to the best of our knowledge, no other kinase has been demonstrated to be capable of phosphorylating MLKL. From these data, we conclude that RIPK3-mediated MLKL phosphorylation contributes to necroptosis as a central pathophysiological contributor of AAV, but cannot rule out RIPK3-independent effects.

Fig. 4.

ANCA-stimulated necroptosis-dependent NET generation induces NCGN. (A–F) NCGN was induced by passive αMPO IgG transfer; NETs were degraded in vivo by twice daily i.p. DNase injections, which resulted in protection from (A) urine pathology and less crescent and necrosis formation by (B) histology. Depicted are typical renal sections with (C) low (10×) and (E) high magnification (40×) from vehicle-treated mice as well as (D) low and (F) high magnifications from DNase-treated mice. (G–L) NCGN was induced by passive αMPO IgG transfer into WT or RIPK3-deficient (Ripk3−/−) mice. Urine pathology was similar in both groups (G), whereas RIPK3 deficiency resulted in less crescent and necrosis formation (H). (I–L) Representative glomeruli with (I) low and (K) high magnifications from WT mice, whereas J shows low and L shows high magnifications from RIPK3-deficient mice. (M–R) NCGN was induced by passive αMPO IgG transfer into WT or MLKL-deficient (Mlkl−/−) mice. Urine pathology showed less leukocyturia and erythrocyturia (M) and less crescent and necrosis formation in MLKL-deficient mice (N). (O–R) Representative glomeruli with low (O) and high (Q) magnifications from WT mice, whereas P shows low and R shows high magnifications from MLKL-deficient mice. Error bars indicate means ± SEM. Comparisons were made using t test or ANOVA; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The passive transfer model did not allow us to specifically study the effect of RIPK3 deficiency in bone marrow (BM)-derived cells that harbor the NET-producing neutrophils. Thus, we generated chimeric mice that lacked RIPK3 only in BM-derived cells. MPO-deficient mice were immunized with murine MPO, irradiated, and transplanted with BM from either WT or RIPK3-deficient mice. After 8 wk, mice that had received WT BM showed urine abnormalities (Fig. 5A) and NCGN by histology (Fig. 5 B, C, and E), whereas mice transplanted with RIPK3-deficient BM were protected (Fig. 5 A, B, D, and F). RIPK3 deficiency did not interfere with BM engraftment (Fig. S1). Thus, our in vitro data together with the animal data obtained in two models using different gene-deficient mice are in line with an important role of myeloid RIPK1/3, MLKL, and NETs in anti-MPO antibody-mediated NCGN.

Fig. 5.

ANCA-stimulated necroptosis in circulating BM-derived cells induces NCGN. (A–F) NCGN was induced in MPO-deficient mice immunized with murine MPO that were subsequently irradiated and transplanted with either WT or RIPK3-deficient (Ripk3−/−) BM. (A–F) RIPK3 deficiency significantly reduced urine pathology (A) and resulted in strong protection from crescent and necrosis induction (B). Depicted are typical renal sections with (C) low and (E) high magnifications from WT mice, whereas D shows low and F shows high magnifications from RIPK3-deficient mice. (G–K) Exemplary micrograph from a biopsy with active anti-MPO-ANCA–associated NCGN shows fibrinoid necrosis and a cellular crescent; the Insets (G) shows the extent of the crescent in blue, necrosis in red, and tuft in green color. No resident mesangial cells, endothelial cells, podocytes, or intracapillary or infiltrating leukocytes are positive (brown) for p-MLKL. (H) Some of the few tubular segments with epithelial positivity for p-MLKL. (I) Biopsy with active anti-MPO-ANCA–associated NCGN and cytoplasmic positivity for p-MLKL in two neutrophils, recognizable by their typical segmented nuclei (short arrows). The colors in the Left Inset are as above. The neutrophil in the Top Right Inset (arrow) is adjacent to a fibrinoid necrosis area (arrowhead) (I and J). The neutrophil in the Bottom Right Inset is adjacent to a fresh, cellular crescent (long arrows). Both neutrophils in the Right Insets are magnified in the corresponding two frames (J and K) to better appreciate nuclear morphology. Error bars indicate means ± SEM. Comparisons were made using t test or ANOVA; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

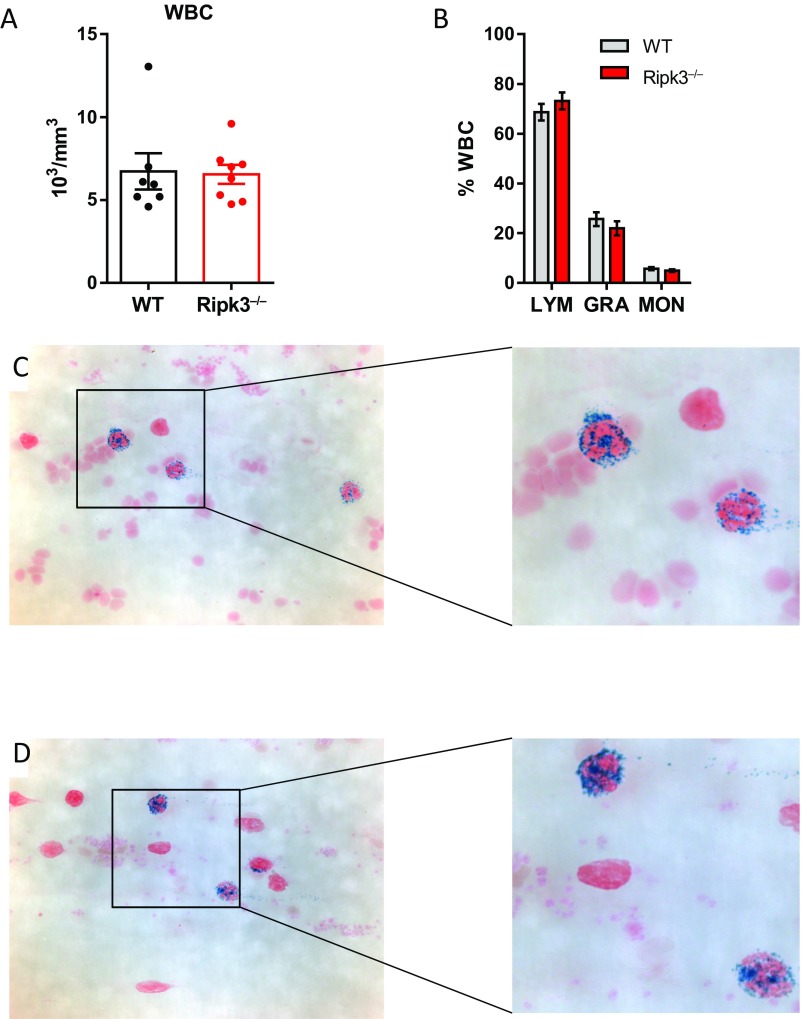

Fig. S1.

Absence of RIPK3 does not affect generation of the bone marrow chimeras. MPO-deficient mice were irradiated and transplanted with either wild-type BM or Ripk3−/− BM. (A and B) Total (A) and differential (B) peripheral blood leukocyte counts did not differ between groups. (C and D) No difference in MPO positivity in peripheral blood smears was observed between WT (C) and Ripk3−/− BM-transplanted (D) mice (Left, 63×; Right, digital magnification). Error bars indicate means ± SEM. GRA, granulocytes; LYM, lymphocytes; MON, monocytes.

In keeping with these data, human kidney biopsy stainings obtained from anti-MPO AAV patients with highly active NCGN exhibited a remarkably specific p-MLKL staining in glomerular neutrophils. Neutrophils were the only glomerular cells found positive for p-MLKL, and there was a notable absence of positivity in parietal epithelial cells, crescents, glomerular endothelial cells, mesangial cells, and mononuclear cells in the ANCA-associated NCGN biopsies and the controls. Out of 12 anti-MPO antibody-associated NCGN biopsies with a total of 174 glomeruli (63 with active crescents, 57 with necrosis), we found 2 p-MLKL–positive glomerular neutrophils (Fig. 5 G–K). Five biopsies with anti-PR3 antibody-associated NCGN did not show glomerular neutrophils with p-MLKL positivity. Biopsies from disease control NCGN did not show any p-MLKL–positive neutrophils. However, this does not exclude the possibility of a role for necroptosis in cells other than neutrophils, because necroptosis is a rapid form of cell death which is inevitably associated with plasma membrane rupture. Therefore, we expect to lose the p-MLKL signal in tissue sections. Together with the in vivo findings of RIPK3- and MLKL-deficient mice, these data suggest that RIPK3-mediated phosphorylation of MLKL and necroptosis in neutrophils play a central role in inducing disease activity in AAV in mice and humans.

Discussion

In summary, we used complementary methods, including quantitative operator-independent analyses, to show that NETs with their characteristic constituents were formed in response to a disease-relevant stimulus, namely ANCA. We provide data supporting the notion that ANCA-induced NET formation is controlled by RIPK1/3 and MLKL, key mediators of the necroptosis pathway. Moreover, we observed that NETs damage the endothelium in vitro and that this effect is, at least in part, mediated by NET-associated AP activation. Finally, we used pharmacologic and genetic approaches in murine disease models and provide AAV patient data supporting the concept that necroptosis and NET formation are relevant for in vivo contribution to anti-MPO antibody-mediated NCGN.

Various infectious and noninfectious mediators were shown to induce NETs. Kessenbrock et al. (12) were the first to demonstrate that ANCA triggers NET formation and deposition in affected glomeruli in AAV patients. NET production by ANCA-activated neutrophils (19, 20, 34, 35) and kidney biopsies from AAV patients with NETs containing citrullinated histones, MPO, and peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 at sites of glomerular fibrinoid necrosis (36) were subsequently reported by others as well. Recently, critical NET-related issues were raised, including the need to define NETs by their characteristic composition, use observer-independent quantification methods, identify the upstream pathways that control NET formation in response to a given stimulus, determine the ways by which NETs cause tissue damage, and use physiologic stimuli with clinical relevance rather than artificial phorbol ester, to name a few (24). In an attempt to address some of these issues, we studied ANCA-induced NETs in vitro and in murine AAV disease models. We found that ANCA triggers NET formation in vitro and detected the typical NET components with extracellular DNA, histones, and human neutrophil elastase in close proximity. This composition characterized the formation of true NETs and distinguished them from any cell-free DNA that could be released after cell lysis. Furthermore, an observer-independent method was introduced by Papayannopoulos et al. (25) that allowed us to quantify NET formation with respect to the percentage of NET-producing cells and NET area.

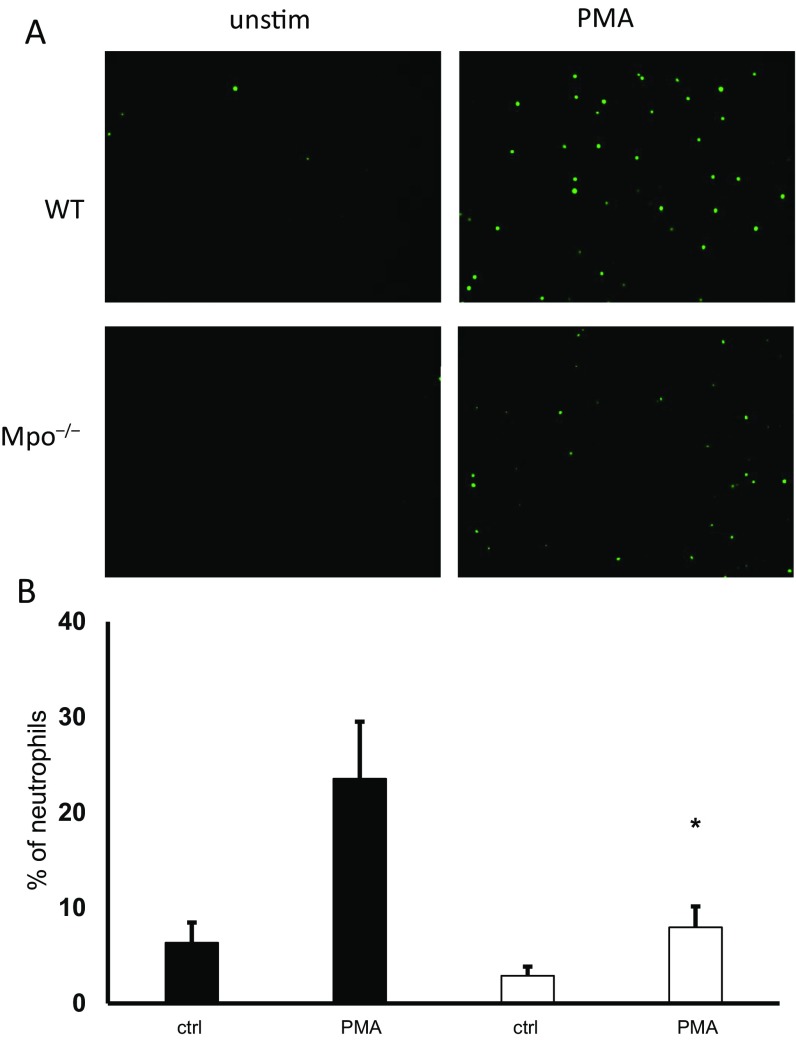

The pathway(s) that controls NET formation in response to ANCA is not known. In general, NET formation may occur in vital neutrophils (26) or as a consequence of regulated necrosis (27, 28). The intracellular signal transduction events that control the regulated necrotic cell death leading to NET formation are not yet clear and may differ between different NET inducers. Necroptosis is a death pathway of regulated necrosis and is currently defined by its caspase independence and its dependence on receptor-interacting protein kinase 1, RIPK3, and the mixed-lineage kinase domain-like protein (29, 37). Necroptosis was shown to control crystal-induced NET formation (38), whereas the role of necroptosis in phorbol-12-myristat-13-acetate (PMA)-induced NET formation is controversial (38–40). We observed that pharmacologic RIPK1 and MLKL inhibitors as well as RIPK3 deficiency reduced NET formation in response to ANCA, suggesting that necroptosis is upstream of ANCA-induced NET production. Automated quantification indicated that both the percentage of NET-forming cells and the NET area decreased with RIPK1 and MLKL inhibition. The cellular mechanism as to how ANCA induces NETs is currently unclear. It is conceivable that MPO-ANCA interferes with MPO activity. We observed abrogated NET generation in MPO-deficient neutrophils in response to PMA, indicating the importance of MPO for NET generation (Fig. S2). In addition, downstream of p-MLKL, necroptosis may be regulated by the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-III complex. Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that additional regulation of the necrotic cell death pathway is involved (41).

Fig. S2.

PMA-induced NET generation is MPO-dependent. Isolated murine neutrophils from WT or Mpo−/− mice were stimulated with PMA, and NET generation was quantified by Sytox green staining. (A) Neutrophils from Mpo−/− mice displayed reduced NET generation by microscopy. (B) Statistical analysis of the percentage of NET-producing neutrophils from three independent experiments shows reduced PMA-induced NET formation in Mpo−/− neutrophils (open columns) compared with WT cells (black columns). Error bars indicate means ± SEM. Comparisons were made using t test or ANOVA; *P < 0.05.

Multiple implications of NETs in AAV are conceivable. NETs contain the ANCA antigens MPO and PR3 and present these antigens in an immunogenic way that promotes autoimmunity (22, 42). It is also conceivable that ANCA-induced NETs participate in endothelial injury. In fact, NET-associated histones were recently shown to damage glomerular ECs in vitro and in an antiglomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis model (43). Moreover, NET-associated matrix metalloproteinases had toxic EC effects in vitro, possibly contributing to vascular injury in systemic lupus erythematosus (44). We observed that isolated NETs induced by ANCA damaged ECs in vitro. DNase and necrostatin-1 reduced EC damage, underscoring the biological importance of necroptosis-induced NET formation in the context of endothelial injury. We made an additional observation, namely that NETs formed not only a scaffold for the activation of the alternative complement pathway but, in turn, contributed to endothelial damage. Thus, NETs may provide a mechanistic link between ANCA-induced neutrophil activation, complement, and endothelial injury. We believe that these findings provide an additional rationale for complement blockade as a therapeutic principle in AAV.

To test key events of our in vitro findings in complex in vivo conditions, we studied AAV disease models and selected two intervention strategies for proof of principle. First, we used a short-term anti-MPO antibody model for NCGN and administered DNase I to degrade NETs. This intervention reduced glomerular necrosis and crescent formation, supporting the notion that NETs contribute to glomerular endothelial injury in vivo. However, we cannot rule out that DNase had additional effects, independent of NET degradation. Second, we used RIPK3- and MLKL-deficient mice to evaluate the need of the necroptosis machinery for NCGN induction by anti-MPO antibodies. We observed protection in RIPK3- and MLKL-deficient mice, but were not able to differentiate the importance of necroptosis in NET-producing BM-derived cells from necroptosis in other cells, including ECs. Therefore, we used a BM transplantation model to generate mice that were RIPK3-deficient in BM-derived cells only. Anti-MPO antibody-mediated NCGN was strongly attenuated in mice that had received RIPK3-deficient BM compared with WT BM. Thus, our in vivo data are in agreement with the importance of necroptosis-controlled NET formation for anti-MPO antibody-mediated NCGN. However, prospective clinical trials are now possible, and should allow the prognostic potential of p-MLKL staining in AAV patients. In summary, in addition to complement, necroptosis pathway elements may represent molecular targets for therapeutic interventions in AAV. Pharmacologic RIPK1 inhibitors are currently in phase II clinical trials for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases, ulcerative colitis, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis (GSK2982772), and other indications (45). Repurposing these drugs for the treatment of AAV seems reasonable.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Neutrophils, IgG, and Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells, NET Production, and Coincubation of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cell Monolayers with NETs.

Neutrophils, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), and IgG were prepared as described previously (46). NETs were isolated by detachment using low DNase I concentrations and coincubated with HUVECs. BSA-FITC permeability was assessed as described (47).

Visualization and Quantification of NET Formation.

To visualize NETs, neutrophils were stained with either Sytox or propidium iodide. For NET quantification, Sytox images of unfixed neutrophils were analyzed using ImageJ processing software (NIH) as described (25).

Mice, Immunization, NCGN Models, and DNase I Treatment Protocol.

Ripk3−/− mice were kindly provided by V. Dixit and K. Newton, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA (48), and Mlkl−/− mice were kindly provided by James Murphy, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, Australia (45). Male and female mice were used both as BM donors and recipients with equal gender distribution. BM engraftment was assessed 5 wk after bone-marrow transplantation. Passive NCGN was induced in female WT, Ripk3−/−, or Mlkl−/− mice. Local authorities approved all animal experiments, which followed the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

p-MLKL Staining of Human Renal Tissue.

Sections from 12 renal biopsies with anti-MPO NCGN, 5 anti-PR3 NCGN, 2 anti-glomerular basement membrane–associated GN, and 3 biopsies with focal necrotizing IgA-GN were stained for p-MLKL. Neutrophils from healthy human donors and HUVECs were obtained after approval by Charité and governmental authorities and after written informed consent.

Statistics.

Results are given as means ± SEM. Comparisons were made using t test or ANOVA; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. See SI Materials and Methods for a detailed description.

SI Materials and Methods

Materials.

Borgal was from Intervet, and urine dipsticks were from Roche Diagnostics. C1q-deficient and factor B-deficient sera were from Quidel, C3-deficient serum was from Sigma, propidium iodide, BSA-FITC, PMA, necrostatin-1, and recombinant DNase I were from Sigma-Aldrich, necrostatin-1s was from VWR, necrosulfonamide was from Millipore, and Sytox green was from Invitrogen. Human TNFα, murine TNFα, LPS (O26:B6), and Ficoll-Hypaque were from Sigma-Aldrich. Dextran was from Amersham Pharmacia, the monoclonal antibody to MPO (clone 2C7) was from Acris, the monoclonal antibody to PR3 (mAb 12.8) was from CLB, an isotype control (clone 11711) was from R&D Systems, and the monoclonal antibodies to HNE, histone H4, and phospho-MLKL were from Abcam and to complement C3d was from Dako (Agilent). Alexa Fluor donkey anti-rabbit IgG was used as secondary antibody (BioLegend). Endotoxin-free reagents and plastic disposables were used in all experiments.

Preparation of Human Neutrophils, Human IgG, and HUVECs, NET Production, and Coincubation of HUVEC Monolayers with NETs.

Neutrophils from healthy human donors and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained after approval by Charité and governmental authorities and after written informed consent. Neutrophils, HUVECs, normal IgG, and ANCA-IgG were prepared as described previously (46). For NET production, 2 × 106 neutrophils were treated with buffer control or primed with 2 ng/mL (human cells) or 5 ng/mL (murine cells) TNFα for 15 min and then activated with 10 µg/mL mAb to PR3 or MPO, with 125 µg/mL human ANCA-IgG, 25 ng/mL, PMA 150 µg/mL, polyclonal murine anti-MPO IgG, or appropriated control antibodies in 12-well plates in the presence of 10% FCS, respectively. After 4 h, supernatants were discarded, and attached cells were washed twice with prewarmed HBSS followed by NET detachment using low DNase I concentrations at 10 U/mL DNase I for 30 min. Cells were removed by centrifugation (5 min at 300 × g) and NETs were either directly used or stored at −80 °C for later use. When indicated, neutrophils were pretreated with increasing necrostatin-1 concentrations. In experiments assessing the role of complement components, neutrophils were activated for 3 h in serum-free conditions before 10% normal human serum or specific complement-depleted human sera (C3, factor B, C1q) were added for the last hour of the 4-h incubation period.

Primary HUVECs were used after two to four passages. Confluent ECs were grown on 0.4-µm 24-well Transwells, and purified NETs were coincubated with HUVECs in 10% human serum or FCS for 1 h. BSA-FITC permeability was assessed as described (47). Where indicated, NETs were degraded by recombinant DNase I (500 U/mL) before being added to the HUVEC monolayer.

Visualization and Quantification of NET Formation.

To visualize NETs, neutrophils were either stained with Sytox green (333 ng/mL) without prior fixation or fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min and stained with cell-impermeable propidium iodide (10 μg/mL) for 5 min. To visualize additional NET components, PFA-fixed samples were stained with anti-HNE (4.5 µg/mL), anti-histone (2.5 µg/mL), or anti-C3d (4.1 μg/mL) antibodies and fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies as indicated. Samples were subjected to fluorescence microscopy using a Leica microscope.

For NET quantification, Sytox images of unfixed neutrophils were analyzed using ImageJ processing software as described (25). Briefly, the Sytox signal area was individually measured for 100 to 300 cells per sample. DNA area derived from each cell (circles) was automatically measured in 200-μm2 steps and the distribution of the number of cells across the range of DNA area was obtained. An area larger than 400 μm2 was denoted as NET formation. Data were converted to the percentage of Sytox-positive cells by dividing the Sytox-positive counts by the total number of cells as determined from corresponding phase-contrast images. Results were plotted as the percentage of cells that were positive for Sytox for each DNA area range.

Quantification of C5a by ELISA.

Isolated NETs were incubated with 10 U/mL recombinant DNase I for 30 min to release NET components. Samples were centrifuged 5 min at 300 × g and subjected to C5a ELISA. C5a was quantitated using a C5a ELISA from R&D following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Mice, Immunization, NCGN Models, and DNase I Treatment Protocol.

All mice were bred in the Max-Delbrueck-Centrum (MDC) animal facility under specific pathogen-free conditions. C57BL/6J (B6) mice were from the Jackson Laboratory, Ripk3−/− mice were kindly provided by V. Dixit and K. Newton, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA, and MLKL-deficient mice were kindly provided by James Murphy, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, Australia, and have been described previously (45, 48). Mpo−/− mice (8 to 10 wk old) were used for immunization, and 8- to 12-wk-old B6 WT or Ripk3−/− mice were used as bone marrow (BM) donors. Male and female mice were used both as BM donors and recipients with equal gender distribution. Local authorities approved all animal experiments, which followed the ARRIVE guidelines. Purification of mouse MPO, immunization of Mpo−/− mice, anti-MPO IgG purification and transfer, and BM transplantation were performed as described (8–10). Briefly, passive NCGN was induced in female WT, Ripk3−/−, or Mlkl−/− mice by i.v. injection of anti-MPO IgG (50 μg/g body weight; BW), followed by i.p. injection of LPS (5 μg/g BW) 1 h later. Where indicated, mice were treated with recombinant DNase I starting 12 h after passive anti-MPO IgG transfer. DNase I, or buffer control, was injected twice daily i.v. at 10 μg/g BW. In the BM transplantation model, MPO-deficient mice were immunized, irradiated, and transplanted with BM from WT or Ripk3−/− mice.

Evaluation of Renal Injury.

Mice were placed in metabolic cages 1 d before being killed and urine was collected for 18 h overnight. Urine was tested by dipstick and semiquantitatively graded on a scale of 0 (none) to 4 (severe) for hematuria and leukocyturia, and 0 to 3 for proteinuria.

For histological evaluation, animals were killed and kidneys were collected, fixed in 10% formalin, and embedded in paraffin using routine protocols; 4-µm coronal sections of specimens were stained with periodic acid Schiff’s and evaluated by light microscopy. Glomerular crescents and necrosis were expressed as the mean percent of glomeruli with crescents and necrosis in each animal.

p-MLKL Immunohistochemistry.

MLKL phosphorylation was analyzed by immunohistochemistry. Briefly, isolated TNFα-primed human neutrophils were stimulated for 60 min with αMPO mAb or isotype control. Cells were centrifuged onto glass slides, fixed in 4% PFA, and permeabilized in 0.05% saponin and 100% acetone (−20 °C). Immunohistochemistry was performed using the Dako EnVision+ Kit HRP Kit. Slides were blocked according to the manufacturer’s protocol and stained overnight with a p-MLKL antibody (1:250). Samples were counterstained with hematoxylin.

p-MLKL Staining of Human Renal Tissue.

Leftover reserve paraffin sections from 12 renal biopsies with necrotizing and crescentic anti-MPO glomerulonephritis, 5 biopsies with anti-PR3 NCGN, 2 biopsies with active antiglomerular basement membrane antibody-associated GN, and 3 biopsies with focal necrotizing IgA-GN (the latter two as controls), which were prepared according to our routine protocol at the Institute of Pathology, University Hospital of Cologne and which would have otherwise been discarded, were stained for phospho-MLKL (ab187091; Abcam), followed by antigen retrieval at pH 6.0, concentration of 1:1,000 with overnight incubation, and detection by a standard horseradish peroxidase detection system.

Assessment of Engraftment After Bone Marrow Transplantation.

BM engraftment was assessed 5 wk after transplantation. Peripheral blood leukocytes were counted by the pathophysiology platform of the MDC. MPO positivity was quantified on peripheral blood smears by peroxidase staining.

Statistics.

Results are given as means ± SEM. Comparisons were made using t test or ANOVA with post hoc analysis by GraphPad Prism 5 software. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sylvia Lucke and Susanne Rolle for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported in part by DFG Grants SCHR 771/6-1 and KE 576/7-1, the Heisenberg Professorship program (LI 2107/2-1), and an ECRC grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1708247114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Davies DJ, Moran JE, Niall JF, Ryan GB. Segmental necrotising glomerulonephritis with antineutrophil antibody: Possible arbovirus aetiology? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6342.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Woude FJ, et al. Autoantibodies against neutrophils and monocytes: Tool for diagnosis and marker of disease activity in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Lancet. 1985;1:425–429. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falk RJ, Jennette JC. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies with specificity for myeloperoxidase in patients with systemic vasculitis and idiopathic necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1651–1657. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806233182504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hilhorst M, van Paassen P, Tervaert JWC. Limburg Renal Registry Proteinase 3-ANCA vasculitis versus myeloperoxidase-ANCA vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2314–2327. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014090903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charles LA, Falk RJ, Jennette JC. Reactivity of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies with mononuclear phagocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;51:65–68. doi: 10.1002/jlb.51.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kettritz R. How anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies activate neutrophils. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;169:220–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04615.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schreiber A, Choi M. The role of neutrophils in causing antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated vasculitis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2015;22:60–66. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schreiber A, et al. C5a receptor mediates neutrophil activation and ANCA-induced glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:289–298. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008050497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huugen D, et al. Inhibition of complement factor C5 protects against anti-myeloperoxidase antibody-mediated glomerulonephritis in mice. Kidney Int. 2007;71:646–654. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao H, Schreiber A, Heeringa P, Falk RJ, Jennette JC. Alternative complement pathway in the pathogenesis of disease mediated by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:52–64. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao H, et al. C5a receptor (CD88) blockade protects against MPO-ANCA GN. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:225–231. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessenbrock K, et al. Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nat Med. 2009;15:623–625. doi: 10.1038/nm.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuchs TA, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15880–15885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005743107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hakkim A, et al. Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9813–9818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909927107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cools-Lartigue J, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3446–3458. doi: 10.1172/JCI67484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight JS, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition reduces vascular damage and modulates innate immune responses in murine models of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2014;114:947–956. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brinkmann V, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Donoghue AJ, et al. Global substrate profiling of proteases in human neutrophil extracellular traps reveals consensus motif predominantly contributed by elastase. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakazawa D, et al. Enhanced formation and disordered regulation of NETs in myeloperoxidase-ANCA-associated microscopic polyangiitis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:990–997. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013060606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohlsson SM, et al. Neutrophils from vasculitis patients exhibit an increased propensity for activation by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;176:363–372. doi: 10.1111/cei.12301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Söderberg D, et al. Increased levels of neutrophil extracellular trap remnants in the circulation of patients with small vessel vasculitis, but an inverse correlation to anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies during remission. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:2085–2094. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sangaletti S, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate transfer of cytoplasmic neutrophil antigens to myeloid dendritic cells toward ANCA induction and associated autoimmunity. Blood. 2012;120:3007–3018. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-416156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kusunoki Y, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibitor suppresses neutrophil extracellular trap formation and MPO-ANCA production. Front Immunol. 2016;7:227. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nauseef WM, Kubes P. Pondering neutrophil extracellular traps with healthy skepticism. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18:1349–1357. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:677–691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilsczek FH, et al. A novel mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2010;185:7413–7425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuchs TA, et al. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:231–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galluzzi L, et al. Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:107–120. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linkermann A, Green DR. Necroptosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:455–465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1310050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Degterev A, et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:313–321. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jayne DRW, et al. CLEAR Study Group Randomized trial of C5a receptor inhibitor avacopan in ANCA-associated vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:2756–2767. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016111179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Najjar M, et al. RIPK1 and RIPK3 kinases promote cell-death-independent inflammation by Toll-like receptor 4. Immunity. 2016;45:46–59. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saleh D, et al. Kinase activities of RIPK1 and RIPK3 can direct IFN-β synthesis induced by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2017;198:4435–4447. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sha L-L, et al. Autophagy is induced by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic Abs and promotes neutrophil extracellular traps formation. Innate Immun. 2016;22:658–665. doi: 10.1177/1753425916668981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma Y-H, et al. High-mobility group box 1 potentiates antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-inducing neutrophil extracellular traps formation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:2. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0903-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshida M, Sasaki M, Sugisaki K, Yamaguchi Y, Yamada M. Neutrophil extracellular trap components in fibrinoid necrosis of the kidney with myeloperoxidase-ANCA-associated vasculitis. Clin Kidney J. 2013;6:308–312. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sft048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linkermann A, Stockwell BR, Krautwald S, Anders H-J. Regulated cell death and inflammation: An auto-amplification loop causes organ failure. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:759–767. doi: 10.1038/nri3743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desai J, et al. PMA and crystal-induced neutrophil extracellular trap formation involves RIPK1-RIPK3-MLKL signaling. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:223–229. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Remijsen Q, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap cell death requires both autophagy and superoxide generation. Cell Res. 2011;21:290–304. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amini P, et al. NET formation can occur independently of RIPK3 and MLKL signaling. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:178–184. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gong Y-N, et al. ESCRT-III acts downstream of MLKL to regulate necroptotic cell death and its consequences. Cell. 2017;169:286–300.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakazawa D, et al. Abnormal conformation and impaired degradation of propylthiouracil-induced neutrophil extracellular traps: Implications of disordered neutrophil extracellular traps in a rat model of myeloperoxidase antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3779–3787. doi: 10.1002/art.34619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar SVR, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap-related extracellular histones cause vascular necrosis in severe GN. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2399–2413. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014070673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carmona-Rivera C, Zhao W, Yalavarthi S, Kaplan MJ. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus through the activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1417–1424. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. ClinicalTrials (2017) Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and efficacy of repeat doses of GSK2982772 in subjects with psoriasis (Natl Inst Health, Bethesda), ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT02776033.

- 46.Schreiber A, Xiao H, Falk RJ, Jennette JC. Bone marrow-derived cells are sufficient and necessary targets to mediate glomerulonephritis and vasculitis induced by anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3355–3364. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006070718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jerke U, et al. Neutrophil serine proteases exert proteolytic activity on endothelial cells. Kidney Int. 2015;88:764–775. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newton K, Sun X, Dixit VM. Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1464–1469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1464-1469.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]