Abstract

We report a single institution series of surgery followed by either early adjuvant or late radiotherapy for atypical meningiomas (AM). AM patients, by WHO 2007 definition, underwent subtotal resection (STR) or gross total resection (GTR). Sixty-three of a total 115 patients then received fractionated or stereotactic radiation treatment, early adjuvant radiotherapy (≤4 months after surgery) or late radiotherapy (at the time of recurrence). Kaplan Meier method was used for survival analysis with competing risk analysis used to assess local failure. Overall survival (OS) at 1, 2, and 5 years for all patients was 87%, 85%, 66%, respectively. Progression free survival (PFS) at 1, 2, and 5 years for all patients was 65%, 30%, and 18%, respectively. OS at 1, 2, and 5 years was 75%, 72%, 55% for surgery alone, and 97%, 95%, 75% for surgery + radiotherapy (log-rank p-value = 0.0026). PFS at 1, 2, and 5 years for patients undergoing surgery without early adjuvant radiotherapy was 64%, 49%, and 27% versus 81%, 73%, and 59% for surgery + early adjuvant radiotherapy (log-rank p-value = 0.0026). The cumulative incidence of local failure at 1, 2, and 5 years for patients undergoing surgery without early External Beam Radiation Therapy (EBRT) was 18.7%, 35.0%, and 52.9%, respectively, versus 4.2%, 13.3%, and 20.0% for surgery and early EBRT (p-value = 0.02). Adjuvant radiotherapy improves OS in patients with AM. Early adjuvant radiotherapy improves PFS, likely due to the improvement in local control seen with early adjuvant EBRT.

Keywords: Radiotherapy, Atypical meningioma, Early, Late

1. Introduction

Meningiomas are the most common primary intracranial neoplasm, comprising about 30% of all reported brain tumors [1]. The WHO classifies meningiomas based on tumor behavior as: benign (WHO Grade I), atypical (WHO Grade II), or malignant (WHO grade III). Atypical meningiomas represent 4–35% [2–4] of meningioma and have a seven-to eightfold increase in recurrence rate and a significantly higher rate of mortality compared to benign meningiomas [2–6]. While gross total resection (GTR) (Simpson grade I, II, or III) or subtotal resection (Simpson grade IV or V) alone are standard treatment options for benign meningiomas, it is unclear if surgery alone is adequate for atypical meningiomas. Several series have demonstrated improved local control with immediate postoperative radiotherapy following surgery [7–9]; however, there is less evidence to support a benefit in overall survival (OS). Moreover, the cognitive toxicities of radiotherapy need to be considered when treating patients with relatively long life expectancy [10,11].

The data for radiotherapy after surgical management of a meningioma are somewhat controversial, particularly in the setting of GTR. Some retrospective studies support the role of adjuvant radiotherapy [7,12–15] while others do not [16,17] and most of these studies are limited by being retrospective series with a limited number of patients [14,18]. Further, these series have discrepancies in the extent of resection (EOR), timing of treatment, and criteria for atypical meningioma (AM) classification in the evaluated patient populations. Thus, a need exists for data evaluating the variables of timing and EOR separately in the setting of the new 2007 WHO classification guidelines.

Currently, no randomized clinical trials have been completed to provide clarity on the issue, although the RTOG has completed accrual of a single arm Phase II study (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00895622) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) is conducting a randomized phase III trial which is expected to be completed in 2024 [19].

The current series represents one of the largest single institution retrospective reviews evaluating the role of adjuvant radiotherapy following surgical management of an AM, and uniquely examines the effect of both EOR and timing on clinical outcomes. The goal of this study was to determine whether outcomes were affected by the timing of radiotherapy and if the efficacy of radiotherapy was affected by the EOR.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient population

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. The neuropathology database at Wake Forest was queried for all patients who received surgical resection of WHO grade II meningiomas between 1993 and 2014. Tumor grade was re-reviewed by neuropathology staff to assure that specimens met the 2007 WHO grading criteria for grade II meningioma. Patient characteristics and outcomes were determined using the patients' electronic medical records.

2.2. Treatment

All patients were treated with surgery (Sx), either GTR defined as Simpson grades I–III or STR defined as Simpson grades IV–V, at the time of initial diagnosis as determined by surgical operative reports. Simpson grade was determined based on the postoperative MRI. Following resection, patients were generally advised to have a consultation appointment with radiation oncology to determine if external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), Gamma Knife stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), or observation were recommended post-surgical options. During the time period of the study, a total of 4 neurosurgeons and 5 radiation oncologists with varied treatment philosophies consulted with patients regarding possible adjuvant therapy. Due to the heterogeneity of treatment philosophies, a dichotomous patient population formed with some patients receiving early radiotherapy, and others receiving radiotherapy at time of failure. Patients opting for early EBRT received a mean of 31 fractions (range 28–35) with a median dose of 55.7 Gy (range 50.4–59.4 Gy); those treated with single-fraction SRS received a median dose of 14.5 Gy (range 12–18 Gy). Early radiotherapy (EBRT, SRS or both) were defined as ≤4 months after surgery, while late radiotherapy was defined as at the time of recurrence. Fourteen patients received a combination of both forms of radiotherapy, either early EBRT with late SRS, early SRS with late EBRT, early EBRT and early SRS, or late EBRT and late SRS. Two patients received repeat surgery.

2.3. Radiotherapy technique

For patients treated with external beam radiotherapy, the majority of patients were treated with a 3D conformal radiotherapy technique. Gross tumor volume (GTV) was defined as gross residual disease as well as the resection cavity. A 1.0 cm dural margin expansion and 0.5 cm parenchymal brain expansion were added to form the clinical target volume (CTV). A 3–5 mm planning target volume (PTV) margin was then added to account for patient setup uncertainty.

For patients treated with SRS, the patient was immobilized on the morning of treatment with a Leksell pin-based headframe. High resolution stereotactic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast was acquired on the same day of treatment or. For patients with STR, the GTV generally consisted of treatment of the enhancing residual tumor, while for patients with GTR the GTV consisted of the tumor resection cavity.

2.4. Follow-up

Following initial treatment, patients underwent a follow-up MRI of the brain every 6 months for the first 2 years, and then annually after 2 years if there was no evidence of recurrence. All follow-up images were compared to images used for staging and evaluated for local failure and distant failure. Local failure was defined as either a histologically-proven recurrence or a 25% increase in the area of enhancement on axial slice MRI with a corresponding increase in perfusion on perfusion-weighted MRI. Distant meningioma was defined as a new meningioma at a site non-contiguous with the original tumor.

2.5. Toxicity

Toxicity was monitored by imaging and clinical follow-up and was defined as any unfavorable and unintended changed in the sign or symptom considered possibly, probably, or definitely related to radiosurgery. The Common Terminology for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0 was used to assign grading.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were determined by group using means and frequencies. Overall survival (OS) was calculated as the time from surgery to death. Progression free survival was calculated as the time from surgery to death, local failure, or distant failure. Time to local failure was calculated as the time from surgery to local failure; participants who died prior to having a local failure were censored at the time of their death. For OS and PFS, patients who had not yet had an event where censored at the date of their last follow-up or five years post-surgery. Kaplan-Meier (KM) plots were created to evaluate the number of events within each level for variables of interest for all outcomes. Log-rank tests were used to test for differences in the survival curves by treatment type, both overall and within surgery type. Cox proportional hazards models were created using a forward selection process based on a list of predefined baseline covariates for the outcome of progression free survival. The list of possible covariates included age, gender, race, type of resection, meningiomatosis, and recurrence from an earlier tumor. Hazards ratios and 95 percent confidence intervals were derived from this Cox model and reported. Competing risks analysis was used to analyze the cumulative incidence of local failure as stratified by extent of resection and the use of adjuvant therapy. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R 3.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

From August 1993 to August 2014, a total of 117 patients were treated for AM with either surgery alone or surgery + radiotherapy. Two patients were excluded from the study do to due concurrent diagnosis of Neurofibromatosis 2 as these patients have a different natural history from standard grade II meningiomas [20]. Fifty-two patients received Sx only and 63 also received radiotherapy. Other patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Median follow-up time was 36.9 months (range 0.01–226.0). The median patient age was 63.6 years (sd = 14.7). Patient gender was 60.9% female and 39.1% male. Patient Characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| All patients | Surgery Only | Surgery + Early EBRT* | Surgery + Late EBRT | Surgery + Early GK | Surgery + Late GK | Surgery + RT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 115 | 52 | 15 | 5 | 16 | 13 | 14 |

| Age, median (sd) | 63.6 (14.7) | 65.4 (14.2) | 62.2 (12.2) | 72.6 (7.2) | 63.0 (13.9) | 54.8 (22.0) | 64.2 (11.7) |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 70 (60.9%) | 31 (59.6%) | 9 (60.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 11 (68.8%) | 7 (53.8%) | 9 (64.3%) |

| Male | 45 (39.1%) | 21 (40.4%) | 6 (40.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 5 (31.3%) | 6 (46.2%) | 5 (35.7%) |

| Race | |||||||

| Non-White | 20 (17.4%) | 10 (19.2%) | 3 (20.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 4 (25.0%) | 1 (7.7%) | 1 (7.1%) |

| White | 95 (82.6%) | 42 (80.8%) | 12 (80.0%) | 4 (80.0%) | 12 (75.0%) | 12 (92.3%) | 13 (92.9%) |

| Type of Resection | |||||||

| GTR | 78 (67.8%) | 37 (71.2%) | 12 (80.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 8 (50.0%) | 11 (84.6%) | 7 (50.0%) |

| STR | 37 (32.2%) | 15 (28.8%) | 3 (20.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 8 (50.0%) | 2 (15.4%) | 7 (50.0%) |

| Meningiomatosis | |||||||

| No | 85 (73.9%) | 40 (76.9%) | 15 (100.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 11 (68.8%) | 10 (76.9%) | 7 (50.0%) |

| Yes | 30 (26.1%) | 12 (23.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 5 (31.3%) | 3 (23.1%) | 7 (50.0%) |

| Recurrence from Earlier Tumor | |||||||

| No | 80 (69.6%) | 38 (73.1%) | 14 (93.3%) | 3 (60.0%) | 9 (56.3%) | 7 (53.8%) | 9 (64.3%) |

| Yes | 35 (30.4%) | 14 (26.9%) | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (40.0%) | 7 (43.8%) | 6 (46.2%) | 5 (35.7%) |

‘Surgery + RT’ is a combination of early EBRT + late GK, early GK + late EBRT, early EBRT + early GK, and late EBRT + late GK.

External Beam Radiation Therapy (EBRT), Gamma Knife (GK), Radiotherapy (RT).

3.2. Overall survival

At the time of analysis a total of 29 of 115 (25.2%) patients had died with median overall survival not yet reached; of those, 18 of the 52 receiving Sx alone (34.6%) died and 11 of 63 (17%) died who had received adjuvant radiotherapy. OS at 1, 2, and 5 years for all patients was 87%, 85%, 66%, respectively. OS at 1, 2, and 5 years for Sx only was 75%, 72%, 55%, versus 97%, 95%, 75% for sx + any radiotherapy (log-rank p-value = 0.0026). Kaplan-Meier is depicted in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

A. Kaplan Meier plot of overall survival for Sx only vs. Sx + Any Radiotherapy (p-value = 0.0026). B. Overall survival for patients undergoing SRT only vs. STR + any radiotherapy (p-value = 0.0002). C. Overall survival for patients undergoing GTR vs. GTR + any radiotherapy (p-value = 0.2748).

OS at 1, 2, and 5 years for STR alone was 64%, 54%, and 32%, respectively, versus 95%, 95%, and 90% for STR + any radiotherapy (log-rank p-value = .0002) see Fig. 1B. OS at 1, 2, and 5 years for GTR alone was 79%, 79%, and 63%, respectively, versus 98%, 95%, and 63%, for GTR + any radiotherapy (log-rank p-value = .2748); however, a trend towards increased survival up to 3 years can be seen (see Fig. 1C). Values for overall survival by surgery type are summarized in Table 2a.

Table 2a.

Overall survival by surgery type.

| All Patients | Surgery Type = STR | Surgery Type = GTR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Surgery Only | Surgery + Any Adjuvant | Surgery Only (STR) | Surgery (STR) + Any Adjuvant | Surgery Only (GTR) | Surgery (GTR) + Any Adjuvant | |

| N | 52 | 63 | 15 | 22 | 37 | 41 |

| Number of events | 18 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 9 |

| Median survival (mth) | NA | NA | 31 | NA | NA | NA |

| Percent surviving at | ||||||

| 1 year | 75 | 97 | 64 | 95 | 79 | 98 |

| 2 years | 72 | 95 | 54 | 95 | 79 | 95 |

| 5 years | 55 | 75 | 32 | 90 | 63 | 63 |

| p-value comparing treatment type | 0.0026 | 0.0002 | 0.2748 | |||

Subtotal resection (STR), gross total resection (GTR).

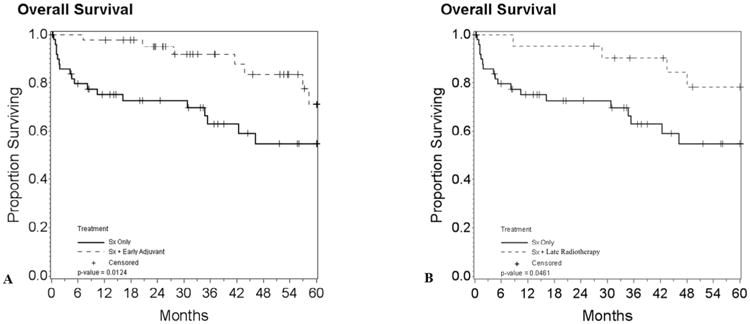

OS at 1, 2, and 5 years for Sx alone was 75%, 72%, 55% versus 98%, 95%, and 71% for Sx + Early adjuvant radiotherapy (log-rank p-value = .0124) (see Fig. 2A) and 95%, 95%, and 78% for Sx + late radiotherapy (log-rank p-value = .0461) (see Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

A. Kaplan Meier plot of overall survival for patients undergoing resection surgery only vs. resection surgery + early adjuvant radiotherapy (p-value = 0.0124). B. Patients undergoing resection surgery only vs. resection surgery + late radiotherapy (p-value = 0.0461).

No statistical difference in OS was found between early versus late radiotherapy (p-value = 0.7866) see Table 2b. No multivariate analysis was calculated for overall survival as once groups were stratified by surgery type, outcomes had too few events to allow for multivariate models.

Table 2b.

Overall survival by adjuvant timing.

| All patients | Surgery Only | Surgery + Early Adjuvant | Surgery + Late Radiotherapy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 115 | 52 | 42 | 21 |

| Number of events | 29 | 18 | 7 | 4 |

| Median survival (mth) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Percent surviving at | ||||

| 1 year | 87 | 75 | 98 | 95 |

| 2 years | 85 | 72 | 95 | 95 |

| 5 years | 66 | 55 | 71 | 78 |

| p-value comparing treatment type | 0.7866 | |||

Surgery + Early/Late adjuvant includes subjects in the Sx + Early EBRT/Late, Sx + Early/Late GK, and Other (where they had early or late adjuvant regardless of other treatments received)

3.3. Progression free survival

PFS at 1, 2, and 5 years for all patients was 65%, 30%, and 18%, respectively. PFSat1,2,and5 years for patients undergoing Sx with-out early adjuvant radiotherapy was 64%, 49%, and 27% versus 81%, 73%, and 59%, for patients undergoing resection Sx + early adjuvant radiotherapy (log-rank p-value = 0.0026), see Fig. 3A. PFS at 1, 2, 5 years for patients undergoing STR without early adjuvant radiotherapy was 65%, 30%, and 18% and 88%, 88%, and 73% for STR + early adjuvant radiotherapy was (p = 0.009) see Fig. 3B; however, there was no statistically significant difference for patients undergoing GTR + early adjuvant radiotherapy (log-rank p-value = 0.1990) see Fig. 3C. PFS values are summarized in Table 3a.

Fig. 3.

A. Kaplan Meier plot of progression free survival for patients undergoing resection surgery vs. resection surgery + early adjuvant radiotherapy (p-value = 0.0026). B. Progression free survival for patients undergoing STR only vs. STR + early adjuvant radiotherapy (p-value = 0.0009). C. Progression free survival for patients undergoing GTR vs. GTR + early adjuvant radiotherapy (p-value = 0.1990).

Table 3a.

Progression free survival by surgery type.

| All Patients | Surgery Type = STR | Surgery Type = GTR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Surgery Only | Surgery + Early Adjuvant | Surgery Only (Sx only or Sx + Late Radiotherapy) | Surgery + Early Adjuvant | Surgery Only (Sx only or Sx + Late Radiotherapy) | Surgery + Early Adjuvant | |

| N | 52 | 42 | 21 | 16 | 52 | 26 |

| Number of events | 24 | 15 | 15 | 4 | 29 | 11 |

| Median survival (mth) | 35 | NA | 18 | NA | 35 | 44 |

| Percent surviving at | ||||||

| 1 year | 67 | 81 | 65 | 88 | 63 | 77 |

| 2 years | 57 | 73 | 30 | 88 | 56 | 64 |

| 5 years | 42 | 59 | 18 | 73 | 30 | 47 |

| p-value comparing treatment type | 0.0026 | 0.0009 | 0.1990 | |||

Surgery (Sx), subtotal resection (STR), gross total resection (GTR).

Results of multivariate analysis performed for PFS are summarized in Table 3b.

Table 3b.

Progression free survival Cox Proportional Hazards Model for surgery type = STR.

| HR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (HR for 10 year increase) | 1.4 | 0.9, 2.2 | 0.0982 |

| Recurrence from Earlier Tumor | |||

| Yes | 2.1 | 0.9, 5.3 | 0.1074 |

| No | Reference | ||

| Treatment | 0.0038 | ||

| Sx Only (Sx only or Sx + late radiotherapy) | 5.3 | 1.7, 16.4 | |

| Sx + Early Adjuvant | Reference | ||

Surgery (Sx), subtotal resection (STR).

3.4. Local failure

3.4.1. Early adjuvant therapy (EBRT or SRS) vs. no early adjuvant therapy

The cumulative incidence of local failure at 1, 2, and 5 years for patients undergoing surgery without early adjuvant radiotherapy was 18.7%, 35.0%, and 52.9%, versus 16.7%, 21.7%, and 30.9% for patients undergoing surgery and early adjuvant radiotherapy, respectively (p-value = 0.17) (Fig. 4A). The cumulative incidence of local failure for STR patients at 1, 2, and 5 years was 13.6%, 28.7%, and 35.0%, versus 20.3%, 30.5%, and 51.1% for GTR (p = 0.45) (Fig. 4B). The cumulative incidence of local failure at 1, 2, and 5 years for patients undergoing STR without early adjuvant radiotherapy was 14.4%, 42.5%, and 49.3%, and for patients undergoing STR with early adjuvant radiotherapy 12.5%, 12.5%, and 19.2% (p-value = 0.30) (Fig. 4C). The cumulative incidence of local failure at 1, 2, and 5 years for patients undergoing GTR without early adjuvant radiotherapy was 20.7%, 32.2%, and 55.5%, respectively and for patients undergoing GTR + adjuvant early radiotherapy 19.2%, 27.4%, and 40.0% (p = 0.48) (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

A. Cumulative Incidence of local failure comparing Sx only vs. Sx + Early Adjuvant radiotherapy (p-value = 0.17). B. Cumulative Incidence of local failure comparing patients undergoing GTR vs. STR (p-value = 0.45). C. Cumulative Incidence of local failure comparing patients undergoing STR only vs. STR + early adjuvant radiotherapy. D. Cumulative Incidence of local failure comparing patients undergoing GTR vs. GTR + early adjuvant radiotherapy.

3.4.2. Early EBRT vs. no early EBRT

The cumulative incidence of local failure at 1, 2, and 5 years for patients undergoing surgery without early EBRT was 21.8%, 34.4%, and 51.4%, versus 4.2%, 13.3%, and 20.0% for patients undergoing surgery and early EBRT, respectively (p-value = 0.02) (Fig. 5A). The cumulative incidence of local failure at 1, 2, and 5 years for patients undergoing STR without early EBRT was 16.7%, 35.3%, and 43.0%, and for patients undergoing STR with early EBRT local failure remained 0% at 1, 2, and 5 years (p = 0.13) (Fig. 5B). The cumulative incidence of local failure at 1, 2, and 5 years for patients undergoing GTR without early EBRT was 24.5%, 34.0%, and 56.8%, respectively, and for patients undergoing GTR + early EBRT was 5.9%, 18.6%, and 30.2% (p = 0.10) (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

A. Cumulative Incidence of local failure in patients undergoing Sx only vs. Sx + EBRT. B. Cumulative Incidence of local failure in patients undergoing STR vs. STR + EBRT. C. Cumulative Incidence of local failure in patients undergoing GTR vs. GTR + EBRT.

3.5. Toxicity

Of the patients treated with radiotherapy, 8 developed treatment related toxicity greater than grade II. Of these 7 developed grade 3 toxicity, one grade 4 toxicity, and no grade 5 toxicities. The one grade 4 toxicity developed seizures refractory to medical intervention and had to be hospitalized. The grade 3 toxicities included radiation necrosis, cognitive disturbances, peripheral neuropathy, seizures, aphasia, and optic nerve disorders.

4. Discussion

Meningiomas have become increasingly prevalent [21] in the United States as the general population ages and as the use of brain imaging has become more prevalent. While the majority of these tumors are benign with relatively good outcomes [22], a significant proportion are AMs with more aggressive pathology and worse outcomes [18,23–25]. A five-year PFS and OS of approximately 50% and 60% for AMs have been demonstrated [26]. Managing these patients requires evaluating the role of adjuvant therapy in both patients receiving GTR and STR. A growing body of literature suggests that early adjuvant radiotherapy improves local control [7–9]; however, the effect on OS is more disputed with some recent studies finding no benefit [7,27]. Some of the inconsistencies reported in the literature could be a result of the variability in the administration of radiotherapy. For instance, adjuvant radiotherapy may be given at the time of original diagnosis (early) or at the time of recurrence (late) and adjuvant therapy can be given to patients who have undergone GTR or STR. Also, the radiotherapy delivery technique can be either EBRT or SRS or both. Furthermore, a greater amount of follow-up is required to detect whether a PFS benefit translates into a benefit in OS, and such a difference may be difficult to detect based on small series with limited follow-up.

We present strong evidence for an increase in OS for patients receiving radiotherapy; though, no statistical difference was found in OS for those receiving early versus late radiotherapy. A greater survival benefit for radiotherapy was seen in patients who had undergone STR and radiotherapy (p = 0.0002) compared to GTR and radiotherapy (p = 0.2748). While we were only able to find a trend towards improvement using radiotherapy in patients receiving GTR, it may be that we were underpowered to detect such a difference, or that the benefit of radiotherapy in the population receiving GTR is of a smaller magnitude. Our findings with regards to OS with adjuvant radiotherapy are consistent with another recent study of 75 patients with AMs that were treated with early adjuvant radiotherapy had increased OS (p = 0.006) [15].

Our data also add evidence to other series demonstrating radiotherapy as an independent predictor of improved PFS [15,23,28]. Again, we found a much stronger benefit for those who had undergone STR (p = 0.0009) compared to GTR (p = 0.1990) with a trend toward improved PFS in the GTR group. A recent retrospective review showed a significant improvement in local control for patients receiving early adjuvant radiotherapy, irrespective of EOR. They found time to local failure to be 180 months after surgery and radiotherapy, compared to 46 months for surgery alone (p = 0.002) [7]. Our data confirm these findings, but only with the modality of EBRT, with a cumulative incidence of local failure of only 20.0% for those receiving early EBRT versus 51.4% for surgery alone (p = 0.02). While early EBRT did not result in statistically significant differences in local failure when stratifying by STR and GTR, this appears due to a lack of statistical power when attempting to analyze these subgroups, and local failure is numerically higher for both STR and GTR in patients who do not receive early EBRT.

Sixteen patients in this series were treated with SRS to the resection cavity following surgery. This is only the second series in the literature reporting such a technique [29]. It evolved based on the benefit seen in treating microscopic residual disease in patients with brain metastases [30]. These patients did not appear to have the same benefit in local control seen with early EBRT. It may be due to the higher marginal failure rate in patients with AM receiving SRS and an inability of radiosurgery to use a treatment margin to cover microscopic disease [25]. However, further studies are likely necessary to determine the value of SRS to the resection cavity.

In summary, we demonstrated that patients diagnosed with AMs benefited from early adjuvant radiotherapy regardless of EOR. While the results confirm other published series in the literature, the current series has several limitations; as a retrospective review, its results are limited to hypothesis generation. As a single institution series, it is subject to patient selection bias. However, in spite of these limitations, this investigation represents one of the largest series reporting outcomes for AM patients treated with surgery followed by adjuvant radiotherapy and uniquely evaluates outcomes in STR, GTR, and in early/late radiotherapy groups. Ultimately, prospective clinical trials will be necessary to validate these findings.

5. Conclusions

The best management of AMs is not evident in the literature. This study seeks to clarify some of these inconsistencies by reporting outcomes for patients with AMs in regard to EOR and timing of treatment. Our data support early adjuvant radiotherapy, preferably EBRT, for all AM patients. Prospective studies are required to validate the findings in this study.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, Ondracek A, Chen Y, Wolinsky Y, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006-2010. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15(suppl 2):ii1–ii56. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kshettry VR, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C, Al-Mefty O, Barnett GH, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. Descriptive epidemiology of World Health Organization grades II and III intracranial meningiomas in the United States. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:1166–73. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Messerer M, Richoz B, Cossu G, Dhermain F, Hottinger AF, Parker F, et al. Recent advances in the management of atypical meningiomas. Neurochirurgie. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2016.02.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuchi.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Pearson BE, Markert JM, Fisher WS, Guthrie BL, Fiveash JB, Palmer CA, et al. Hitting a moving target: evolution of a treatment paradigm for atypical meningiomas amid changing diagnostic criteria. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24:E3. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/24/5/E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hug EB, Devries A, Thornton AF, Munzenride JE, Pardo FS, Hedley-Whyte ET, et al. Management of atypical and malignant meningiomas: role of high-dose, 3D-conformal radiation therapy. J Neurooncol. 2000;48:151–60. doi: 10.1023/a:1006434124794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLendon RE, Rosenblum MK, Bigner DD. Russell & Rubinstein's pathology of tumors of the nervous system. 7th. CRC Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagshaw HP, Burt LM, Jensen RL, Suneja G, Palmer CA, Couldwell WT, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for atypical meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2016:1–7. doi: 10.3171/2016.5.JNS152809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi Y, Lim DH, Jo K, Nam DH, Seol HJ, Lee JI. Efficacy of postoperative radiotherapy for high grade meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2014;119:405–12. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris AE, Lee JY, Omalu B, Flickinger JC, Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD. The effect of radiosurgery during management of aggressive meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 2003;60:298–305. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(03)00320-3. discussion 305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henzel M, Fokas E, Sitter H, Wittig A, Engenhart-Cabillic R. Quality of life after stereotactic radiotherapy for meningioma: a prospective non-randomized study. J Neurooncol. 2013;113:135–41. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peiffer AM, Leyrer CM, Greene-Schloesser DM, Shing E, Kearns WT, Hinson WH, et al. Neuroanatomical target theory as a predictive model for radiation-induced cognitive decline. Neurology. 2013;80:747–53. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318283bb0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cain SA, Smoll NR, Van Heerden J, Tsui A, Drummond KJ. Atypical and malignant meningiomas: considerations for treatment and efficacy of radiotherapy. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:1742–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasan S, Young M, Albert T, Shah AH, Okoye C, Bregy A, et al. The role of adjuvant radiotherapy after gross total resection of atypical meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2015;83:808–15. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komotar RJ, Iorgulescu JB, Raper DM, Holland EC, Beal K, Bilsky MH, et al. The role of radiotherapy following gross-total resection of atypical meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2012;117:679–86. doi: 10.3171/2012.7.JNS112113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piscevic I, Villa A, Milicevic M, Ilic R, Nikitovic M, Cavallo LM, et al. The influence of adjuvant radiotherapy in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: a series of 88 patients in a single institution. World Neurosurg. 2015;83:987–95. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mair R, Morris K, Scott I, Carroll TA. Radiotherapy for atypical meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:811–9. doi: 10.3171/2011.5.JNS11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon H, Mehta MP, Perumal K, Helenowski IB, Chappell RJ, Akture E, et al. Atypical meningioma: randomized trials are required to resolve contradictory retrospective results regarding the role of adjuvant radiotherapy. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:59–66. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.148708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur G, Sayegh ET, Larson A, Bloch O, Madden M, Sun MZ, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for atypical and malignant meningiomas: a systematic review. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:628–36. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkinson MD, Weber DC, Haylock BJ, Mallucci CL, Zakaria R, Javadpour M. Atypical meningoma: current management dilemmas and prospective clinical trials. J Neurooncol. 2015;121:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu A, Kuhn EN, Lucas JT, Jr, Laxton AW, Tatter SB, Chan MD. Gamma Knife radiosurgery for meningiomas in patients with neurofibromatosis Type 2. J Neurosurg. 2015;122:536–42. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.JNS132593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolecek TA, Dressler EV, Thakkar JP, Liu M, Al-Qaisi A, Villano JL. Epidemiology of meningiomas post-Public Law 107–206: The Benign Brain Tumor Cancer Registries Amendment Act. Cancer. 2015;121:2400–10. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fokas E, Henzel M, Surber G, Hamm K, Engenhart-Cabillic R. Stereotactic radiation therapy for benign meningioma: long-term outcome in 318 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89:569–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park HJ, Kang HC, Kim IH, Park SH, Kim DG, Park CK, et al. The role of adjuvant radiotherapy in atypical meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2013;115:241–7. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1219-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riemenschneider MJ, Perry A, Reifenberger G. Histological classification and molecular genetics of meningiomas. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:1045–54. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70625-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Attia A, Chan MD, Mott RT, Russell GB, Seif D, Daniel Bourland J, et al. Patterns of failure after treatment of atypical meningioma with gamma knife radiosurgery. J Neurooncol. 2012;108:179–85. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0828-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang YC, Chuang CC, Wei KC, Chang CN, Lee ST, Wu CT, et al. Long term surgical outcome and prognostic factors of atypical and malignant meningiomas. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35743. doi: 10.1038/srep35743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkinson MD, Waqar M, Farah JO, Farrell M, Barbagallo GMV, McManus R, et al. Early adjuvant radiotherapy in the treatment of atypical meningioma. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;28:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun SQ, Hawasli AH, Huang J, Chicoine MR, Kim AH. An evidence-based treatment algorithm for the management of WHO Grade II and III meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;38:E3. doi: 10.3171/2015.1.FOCUS14757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardesty DA, Wolf AB, Brachman DG, McBride HL, Youssef E, Nakaji P, et al. The impact of adjuvant stereotactic radiosurgery on atypical meningioma recurrence following aggressive microsurgical resection. J Neurosurg. 2013;119:475–81. doi: 10.3171/2012.12.JNS12414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen CA, Chan MD, McCoy TP, Bourland JD, deGuzman AF, Ellis TL, et al. Cavity-directed radiosurgery as adjuvant therapy after resection of a brain metastasis. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:1585–91. doi: 10.3171/2010.11.JNS10939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]