Abstract

Inhibitory and excitatory neurons form intricate interconnected circuits in the mammalian sensory cortex. Whereas the function of excitatory neurons is largely to integrate and transmit information within and between brain areas, the inhibitory neurons are thought to shape the way excitatory neurons integrate information, and exhibit context-and behavior-specific responses. Over the last few years, work across sensory modalities has begun unraveling the function of distinct types of cortical inhibitory neurons in sensory processing, identifying their contribution to controlling stimulus selectivity of excitatory neurons and modulating information processing based on the behavioral state of the subject. Here, we review the results from recent studies, and discuss the implications for the contribution of inhibition to cortical circuit activity and information processing.

Role of interneurons in sensory processing

The fundamental quest of sensory neuroscience is to link a specific function in sensory processing to an identified circuit within the sensory pathway. One of the most striking aspects of neuronal morphology in the sensory cortex is the astonishing diversity of inhibitory interneurons. This diversity is thought to underlie the brain's ability to process and respond to complex and varied everyday sensory environments. By exhibiting differential patterns in their connectivity to excitatory and other types of inhibitory cells within and across cortical layers, interneurons contribute to the formation of a variety of microcircuits supporting potentially complex sensory processing functions. Over the last few years, there has been considerable progress in understanding of the role of different interneurons in sensory processing.

Cortical inhibitory interneurons are comprised of a vastly diverse population, with cells differing both morphologically and physiologically. Whereas up to several hundred inhibitory neuronal subtypes can be recognized [1–5], the inhibitory neurons have been grouped into three predominant classes based on molecular markers: parvalbumin-positive (PVs), somatostatin-positive (SOMs) and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-positive interneurons (VIPs) [3,6]. The most common class of the three in the sensory cortex are PVs, which include the "basket cells", which target excitatory neuronal cell bodies [7]. As such, they are thought to provide global inhibition to excitatory neuronal populations [8]. SOMs, the second most common class, contain a large population of Martinotti cells [9], which target the distal dendrites of excitatory neurons, and thus could exert a more specific effect of modulating excitatory neuronal responses to stimuli [10]. VIPs in the cortex preferentially target SOMs [11–15] and to a lesser extent PVs [14]. Since SOM and PV interneurons target excitatory cells , VIP interneurons are ideally placed to modulate cortical activity through disinhibition of excitatory cells via inhibition of SOM interneurons [13]. A fundamental question for systems neuroscientists studying sensory processing has been to understand whether and how the diversity in morphological cell types of interneurons corresponds to specific functions during stimulus discrimination.

Over the last few years, optogenetic techniques led to significant progress in identifying the function of distinct interneuron types in sensory processing [16–23]. A specific subset of neurons can be driven to express an opsin, which, when stimulated by light, leads to depolarization or hyperpolarization of the neuron that expresses it. Optogenetic techniques allow mesuring the effects of suppressing or activating a particular neuronal cell type while the animal is presented with a stimulus or engaged in a perceptual task and to be coupled with recording of ongoing neuronal activity [14,23–26]. Below, we review recent studies in which these approaches were used to modulate the activity level of specific subtypes of interneurons while measuring the tuning curves of excitatory neurons, in order to determine their function in stimulus selectivity, or manipulating the inhibitory neuronal activity during perceptual tasks performed by the subjects to assay the contribution of specific interneuron cell types.

Role of interneurons in stimulus selectivity

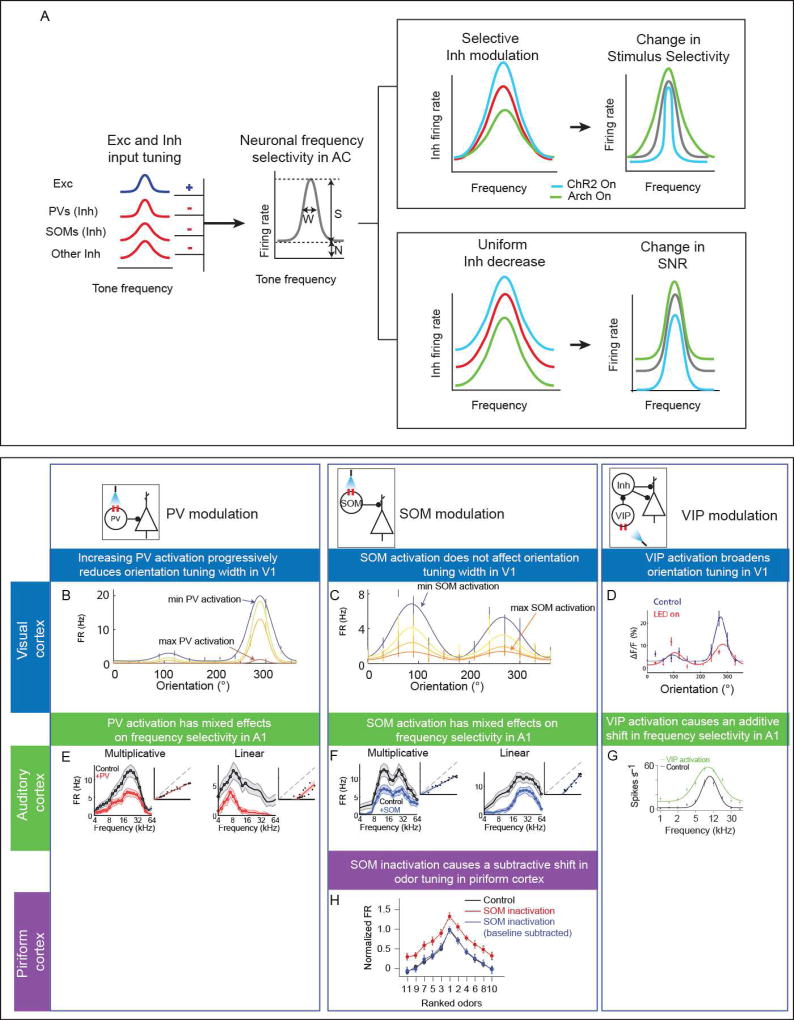

Behavioral discrimination of sensory stimuli is thought to rely on sensory tuning, or selectivity, of neuronal populations. Neurons in the sensory cortex typically exhibit selectivity for specific aspects of sensory stimuli – for example, neurons in the auditory cortex exhibit frequency tuning with elevated responses to tones of particular frequency [27–29]. This stimulus selectivity arises through the combination of excitatory and inhibitory inputs to neurons (Figure 1A), which themselves have stimulus tuning [29–31]. Several theories for the contribution of inhibition to stimulus selectivity rely largely on the differences or similarities in tuning profiles of excitatory and inhibitory inputs (Figure 1) [32–34]. By providing co-tuned input, inhibition can enhance selectivity in a multiplicative fashion [29]. Alternatively, by providing broadly tuned uniform inhibition, inhibitory neurons can increase selectivity through a linear offset to the excitatory neuronal responses, such that the relative strength of the offset increases with distance from the receptive field center [35]. In another scheme, the differences in timing between excitatory and inhibitory neurons can lead to sharpening or broadening of the tuning of excitatory neurons [36]. These models were previously supported by results from studies measuring relative contribution of excitatory and inhibitory currents to receptive fields of excitatory neurons or using pharmacological tools to suppress inhibition. For example, in the auditory cortex, experimental evidence from pharmacological experiments and intra-cellular recordings has supported either of these schemes [29,32–37] providing a contradictory view of the function of inhibition in sensory tuning. However, given the wide range of inhibitory neuron subtypes, an emerging possibility is that the different types of inhibitory neurons differentially shape the tuning properties of excitatory neurons.

Figure 1.

Sensory tuning of neurons in the cortex (example: frequency tuning in the auditory cortex) is shaped by the interactions of excitatory (Exc) inputs (blue), and inhibitory (Inh) inputs (red) from several neuronal cell types, including PVs and SOMs, which themselves exhibit stimulus selectivity. A. Suppression (green) or activation (cyan) of inhibitory interneurons selectively (top right) or uniformly (bottom right) modulates responses of inhibitory neurons, which control frequency selectivity and signal-to-noise ratio of responses of excitatory neurons. Modulation of selective inhibition can affect tuning width, whereas broad inhibition modulation can affect signal-to-noise ratio. Both of these effects can change the sensitivity of neuronal populations to stimuli. S: signal, N: noise; W: tuning width; SNR: signal-to-noise ratio. B. Example neuron showing increasing levels of PV activation in visual cortex decreases firing rate and orientation tuning width in putative excitatory cells. [Adapted from 38]. C. Example neuron showing increasing levels of SOM activation in visual cortex decreases firing rate, but has no effect on orientation tuning width. Adapted from Lee et al., 2014. D. Example unit showing activation of VIP interneurons in visual cortex decreases orientation selectivity. Adapted from [Adapted from 46]. E. Example units showing activation of PV interneurons in auditory cortex has both multiplicative and linear effects on frequency selectivity. Adapted from [21]. F. Example units showing activation of SOM interneurons in auditory cortex has both multiplicative and linear effects on frequency selectivity [Adapted from 21]. G. Activation of VIP interneurons in auditory cortex causes an additive shift in frequency selectivity (n = 28). [Adapted from 14]. H. Inactivation of SOM interneurons in piriform cortex causes a subtractive shift in odor tuning (n = 29). [Adapted from 45].

In primary visual cortex, studies testing how PV activity affected excitatory neuronal responses to oriented gratings provided mixed results. Activating channelrhodopsin-expressing PVs with high intensity light decreased the firing rate and sharpened the orientation tuning of excitatory neurons in one study [19,38], whereas activating or suppressing PVs with light of lower intensity linearly shifted the responses of excitatory neurons without affecting their stimulus sensitivity [39]. This suggested that PVs contributed to visual selectivity (Figure 1B) through a mechanism that shifted the excitatory tuning both linearly and multiplicatively. Modulation of SOMs yielded more specific modulatory effects, producing changes in responses that were stimulus-dependent through surround suppression release [40,41]. These results are consistent with broad uniform inhibition provided by SOMs (Figure 1C), as measurements of SOM response properties found that SOMs respond to larger stimuli that encompass the surround at shorter response latencies than to smaller stimuli [42].

In other sensory modalities, modulating activity of PVs and SOMs similarly drove heterogeneous effects on stimulus-driven responses. In the auditory cortex, activating PVs resulted in narrowing of the receptive fields of excitatory neurons and an increase in the strength of their tone-evoked responses [23,43], whereas their suppression led to opposite effects [23]. Suppressing or activating SOMs increased or decreased the firing rate of excitatory neurons respectively [21,44], but the effect was more often multiplicative when SOM activity was reduced as compared with PVs, whose suppression provided both multiplicative and linear shifts in excitatory neuronal responses to tones. Activation of PVs or SOMs also produced a mixture of multiplicative and linear shifts in excitatory neuronal responses to tones (Figure 1E-F). By contrast, in the piriform cortex, SOM inactivation caused a predominantly additive shift in odor tuning and reduced neuronal discriminability (Figure 1H) [45].

A third class of interneurons, VIPs, also contributed to stimulus selectivity in the visual cortex, providing facilitation specific to the receptive field center, but not the surround, of excitatory cells [41]. Manipulating VIP activity affected spatial and orientation tuning. Specifically, activation of VIP interneurons increased preferred spatial frequency, while inactivation decreased preferred spatial frequency, and both manipulations decreased orientation selectivity (Figure 1D) [46]. This finding of increased spatial resolution with VIP activation could in fact be a substrate mechanism of how VIP activation can improve performance in behavioral tasks [41]. By contrast, in the auditory cortex, VIPs had a differential effect, consistent with disinhibition of excitatory neurons: activation of VIPs caused a positive shift in tone-evoked excitatory responses (Figure 1G) [14]. More specifically, activating cholinergic inputs to VIP interneurons broadened the tuning of excitatory cells to tones of different frequencies by decreasing responses to the preferred frequency and increasing responses to the less preferred stimuli [47].

These heterogeneous effects of modulation of interneuron activity point to the complexity of the underlying circuits: even a simple model that represents recurrent excitatory and neuronal populations through mean activity level has demonstrated that elevating inhibitory activity can yield diverse, and potentially paradoxical effects, either suppressing or enhancing activity of excitatory neuronal populations [48]. A model of responses of excitatory and inhibitory neurons demonstrated that a similar mechanism may appear as a linear or a multiplicative shift, depending on the parameters of optogenetic manipulations [44]. An inhibitory-excitatory circuit rate model found that a small change in connection parameters between inhibitory and excitatory neurons as well as stimulation parameters can yield differential effects on neuronal network behavior [22,23]. To bring the disparate findings together, future studies need to investigate perturbations under variable light intensities, and combine the results with computational analysis for identifying the differential contribution of interneuron cell types to sensory processing in a coupled neuronal circuit [49]. Further specific targeting of opsins to interneuron subtypes within the broad interneuron classes as well as layer-specific studies for inhibitory-excitatory interactions [3] will help understand the degree of complexity of the interactions.

Role of interneurons in behavioral state modulation

Inhibitory interneurons are also involved in modulation of sensory responses by the behavioral state of the subject across sensory modalities. A striking example of this modulation is provided by locomotion. Locomotion has been predicted to affect sensory processing, for example by activating visual processing pathways dedicated to processing of rapidly changing stimuli; or by suppressing activity that would be due to locomotion artifact.

In visual cortex, locomotion was found to increase excitatory activity [50–52]. Recent recordings from VIP interneurons found that they also increase their firing rate during locomotion [52–54], while the firing rate of SOMs decreases [52,53]. These findings suggest that increased stimulus-driven responses of excitatory neurons observed in V1 during locomotion could be caused by inhibition of SOM activity through activation of VIPs [53]. However, when combined with stimulus presentation, SOM interneurons increased their stimulus-driven firing rate during locomotion [51]. Recording activity of VIP, SOM and PV interneurons during still periods or locomotion in darkness or with visual stimulation revealed differential effects of locomotion on neuronal responses depending on the presence of visual stimulation [55]. During visual stimulation, interneurons from all three interneuron classes increased their responses with locomotion, challenging the generality of the VIP disinhibitory network as the mechanism underlying increases in stimulus driven excitatory responses during locomotion, and suggests that the action of VIPs may be both stimulus and behavioral-state dependent.

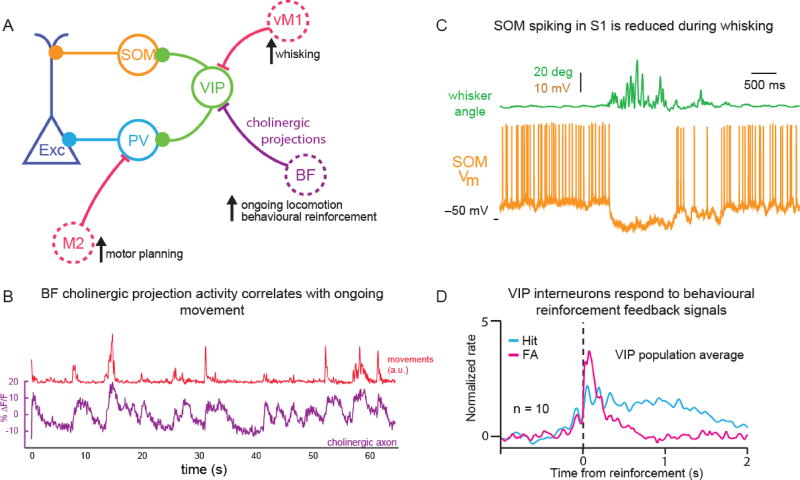

By contrast, in the auditory cortex, locomotion caused a decrease in excitatory responses to auditory stimuli [56–58]. This reduction in response is thought, in part, to be driven by direct corollary projections from neurons in secondary areas of motor cortex innervating auditory cortex directly immediately prior to movement (Fig 2A-B). These excitatory projections target PV interneurons in auditory cortex, thus inhibiting excitatory neurons during locomotion [57,58]. In addition, the auditory cortex received motion-related cholinergic input alongside direct input from motor cortex; these two signals provide distinct movement-related information [47]. Cholinergic inputs from the basal forebrain target VIPs [53], SOMs [59], and excitatory cells directly [47], thereby providing information about ongoing physical activity and arousal state, whereas secondary motor cortex inputs provide top-down information about impending movement and target AC PVs and pyramidal cells just prior to movement initiation [47]. Cholinergic activity in auditory cortex increased not only during locomotion but during other small movements such as licking, paw movement, and whisking (Fig 2B) [47]. Similarly, it has been shown that cholinergic activity in the barrel cortex of mice is increased during active whisking [60]. Activity of VIPs also increased during active whisking as a result of direct input from primary motor cortex: VIPs were found to preferentially inhibit SOMs, releasing excitatory neurons from SOM inhibition [12]. This result is consistent with the finding that SOM interneurons were more active during quiet wakefulness (with no whisking) compared with other neuronal subtypes in L2/3 and were suppressed by both passive whisker deflection and active whisking (Fig 2C) [61].

Figure 2.

PVs and SOMs inhibit excitatory neurons in sensory cortex (A) whereas VIPs in primary somatosensory cortex preferentially target SOMs. VIPs receive input directly from primary vibrissal motor cortex (vM1) during active and passive whisker movement thus decreasing SOM activity [C – 61]. During ongoing locomotion, auditory and visual cortex receives input from cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain (BF) [B – 47] and auditory cortex receives input from secondary motor cortex (M2) which conveys information about motor planning. Cholinergic activity also conveys information about feedback signals during behavioural training [64] and preferentially target VIPs, VIPs thus respond to feedback signals [D – 14]. (A) Simplified circuit diagram of sensory cortex, solid circles indicate interneurons (VIP, SOM and PV) which target excitatory cells (Exc) and each other. Dashed circles indicate other brain areas which project to sensory cortex. (B) Activity in cholinergic axons in auditory cortex (purple shows a single example axon) correlates with small movements (licking, paw movements etc.) of the mouse (red). [Adapted from 47]. (C) SOM (yellow) spiking activity is decreased during passive and active whisker movement (green indicates angle of whisker, Vm = membrane potential). [Adapted from 61]. (D) VIP interneurons respond to behavioural feedback signals. They show shallow sustained response to water rewards in hit trials (cyan) and strong, sharp response to air puff or mild shock during in false alarm trials (magenta). [Adapted from 14].

Some of the effects of physical activity on cholinergic modulation of cortical neuron responses are due not simply to physical movement, but also to changes in the attentional or arousal state of the animal [62]. More generally, cholinergic activity in sensory cortex correlated with pupil size, a well-established measure of arousal state [62], feedback signals during behavioral tasks [63,64], behavioral performance [63], and behavioral context of the stimulus presentation [65]. Cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain are rapidly activated by feedback signals during behavioral tasks [64] and, consistent with the finding that they preferentially target VIPs in sensory cortex [47,53], VIPs show activity correlated with reinforcement signals (Fig 2D) [14]. Thus, cholinergic modulation can exhibit both direct activation and indirect disinhibition (via VIPs) of excitatory neurons, providing a rich foundation for directing cortical responses in a context-specific fashion.

Combined, these studies suggest that inhibition controls modulation of sensory responses during locomotion, attention, and behavior, with a range of effects that are at least in part facilitated through cholinergic inputs that target VIPs and differentially perturb inhibitory and excitatory connections.

Future goals for investigation of the function of inhibition in sensory processing and perception

The development of optogenetic tools led to considerable progress in understanding the role of inhibitory interneurons in sensory processing over a relatively brief period of time. However, application of optogenetics has thus far been generally coarse, targeting a broad class of interneurons over a relatively large area. Future studies need to target specific subclasses of interneurons, which will become amenable to specific targeting as genetic understanding of the classes and subclasses of interneurons improves [66]; one recent method targets specific cells through a combination of projection-specific and genetically identified labels [67]. Furthermore, two-photon laser stimulation techniques now allow for targeting of single or multiple specific neurons for optogenetic manipulation [e.g. 68] as well as coupling with single cell electroporation [69], which can further help to dissect the role of specific cells within sensory cortical circuits. Activation or deactivation of specific types of cells with optogenetics is often very strong and thus it is possible that subtle changes in depolarization state of neurons that may be important in sensory processing are missed. Measuring subthreshold responses during sensory processing and mimicking these changes with optogenetics could further help to unravel the roles played by interneurons in sensory processing.

To understand the different roles of neuronal subtypes in cortical networks, sophisticated models will need to be developed that can pull together vast amounts of information gleaned from different studies on the roles of neural subtypes and provide testable hypotheses [70]. Recently, there have been attempts to make more realistic circuit models which include subtypes of interneurons [71,72]. Lee et al. (2017) were able to replicate multiple experimental findings, including function of distinct interneuron subtypes in ‘attentional gating’ as well as an explanation for differential effects of VIP/SOM activity in visual cortex [19,41]. Interestingly, both models found that top-down driven VIP activity need not be context selective to achieve attentional gating, something which can be tested experimentally. More realistic models of cortical circuits will help in understanding heterogeneous findings from different sensory areas, whether there are distinct roles of specific subtypes of interneuron in different cortical areas and also the variation caused by different experimental conditions. It is important to know the exact conditions of experiments in order to correctly define the roles of neural subtypes [e.g. 55] to avoid confounding effects, for example, the arousal state of the animal [62]. Furthermore, it will be important in the future to corroborate findings or compare differences with other animals, as application of optogenetic tools in other animal models improves [e.g. 73].

Distinct cortical inhibitory interneurons control sensory perception

Modulating cortical inhibition can sharpen or broaden stimulus tuning in the sensory cortex and drive heterogeneous additive and multiplicative changes in neuronal stimulus selectivity.

Locomotion increases activity in the visual cortex, and suppresses activity in the auditory cortex

Future studies need to combine graded targeted perturbation of activity of specific neuronal cell types with comprehensive excitatory-inhibitory models of cortical recurrent activity to understand the function of different interneuron types in sensory processing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (Grant numbers NIH R03DC013660, NIH R01DC014700, NIH R01DC015527), Klingenstein Award in Neuroscience, Human Frontier in Science Foundation Young Investigator Award and the Pennsylvania Lions Club Hearing Research Fellowship to MGN. MNG is the recipient of the Burroughs Wellcome Award at the Scientific Interface. JFB is supported by National Institutes of Health (Grant number NIH NIMH T32MH017168).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with respect to the work described in the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kawaguchi Y. Neostriatal cell subtypes and their functional roles. Neurosci Res. 1997;27:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(96)01134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeFelipe J, Lopez-Cruz PL, Benavides-Piccione R, Bielza C, Larranaga P, Anderson S, Burkhalter A, Cauli B, Fairen A, Feldmeyer D, et al. New insights into the classification and nomenclature of cortical GABAergic interneurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:202–216. doi: 10.1038/nrn3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tremblay R, Lee S, Rudy B. GABAergic Interneurons in the Neocortex: From Cellular Properties to Circuits. Neuron. 2016;91:260–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kepecs A, Fishell G. Interneuron cell types are fit to function. Nature. 2014;505:318–326. doi: 10.1038/nature12983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urban-Ciecko J, Barth AL. Somatostatin-expressing neurons in cortical networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:401–409. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudy B, Fishell G, Lee S, Hjerling-Leffler J. Three groups of interneurons account for nearly 100% of neocortical GABAergic neurons. Developmental neurobiology. 2011;71:45–61. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Gupta A, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Wu CZ, Markram H. Anatomical, physiological, molecular and circuit properties of nest basket cells in the developing somatosensory cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:395–410. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Packer AM, Yuste R. Dense, unspecific connectivity of neocortical parvalbumin-positive interneurons: a canonical microcircuit for inhibition? J Neurosci. 2011;31:13260–13271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3131-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Gupta A, Wu C, Silberberg G, Luo J, Markram H. Anatomical, physiological and molecular properties of Martinotti cells in the somatosensory cortex of the juvenile rat. J Physiol. 2004;561:65–90. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.073353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vu ET, Krasne FB. Evidence for a computational distinction between proximal and distal neuronal inhibition. Science. 1992;255:1710–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1553559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker F, Mock M, Feyerabend M, Guy J, Wagener RJ, Schubert D, Staiger JF, Witte M. Parvalbuminand vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-expressing neocortical interneurons impose differential inhibition on Martinotti cells. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13664. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S, Kruglikov I, Huang ZJ, Fishell G, Rudy B. A disinhibitory circuit mediates motor integration in the somatosensory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1662–1670. doi: 10.1038/nn.3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeffer CK, Xue M, He M, Huang ZJ, Scanziani M. Inhibition of inhibition in visual cortex: the logic of connections between molecularly distinct interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1068–1076. doi: 10.1038/nn.3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14**.Pi HJ, Hangya B, Kvitsiani D, Sanders JI, Huang ZJ, Kepecs A. Cortical interneurons that specialize in disinhibitory control. Nature. 2013;503:521–524. doi: 10.1038/nature12676. This study establishes three important principles: that VIPs inhibit other interneurons in the medial pre-frontal cortex and auditory cortex in vivo; that activation of VIP neurons in auditory cortex causes an additive gain in putative pyramidal cells where as it causes ‘divisive’ gain in cells directly inhibited by VIPs; that VIPs represent reinforcement signals during a tone frequency discrimination task. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang X, Shen S, Cadwell CR, Berens P, Sinz F, Ecker AS, Patel S, Tolias AS. Principles of connectivity among morphologically defined cell types in adult neocortex. Science. 2015;350:aac9462. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1263–1268. doi: 10.1038/nn1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sohal VS, Zhang F, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K. Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature. 2009;459:698–702. doi: 10.1038/nature07991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deisseroth K. Optogenetics. Nature methods. 2011;8:26–29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19**.Lee SH, Kwan AC, Zhang S, Phoumthipphavong V, Flannery JG, Masmanidis SC, Taniguchi H, Huang ZJ, Zhang F, Boyden ES, et al. Activation of specific interneurons improves V1 feature selectivity and visual perception. Nature. 2012;488:379–383. doi: 10.1038/nature11312. Manipulation of PVs but not SOMs or VIPs, modulated orientation tuning; and that activation of PVs improved behaviorally measured orientation discrimination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao X, Wehr M. A Coding Transformation for Temporally Structured Sounds within Auditory Cortical Neurons. Neuron. 2015;86:292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seybold BA, Phillips EA, Schreiner CE, Hasenstaub AR. Inhibitory Actions Unified by Network Integration. Neuron. 2015;87:1181–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natan RG, Briguglio JJ, Mwilambwe-Tshilobo L, Jones SI, Aizenberg M, Goldberg EM, Geffen MN. Complementary control of sensory adaptation by two types of cortical interneurons. eLife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.09868. pii: e09868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23**.Aizenberg M, Mwilambwe-Tshilobo L, Briguglio JJ, Natan RG, Geffen MN. Bidirectional Regulation of Innate and Learned Behaviors That Rely on Frequency Discrimination by Cortical Inhibitory Neurons. PLoS biology. 2015;13:e1002308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002308. Activation of a specific type of interneurons in the auditory cortex results in improvement in behavioral auditory discrimination acuity and an increase in tone-evoked response magnitude, whereas suppression of this interneuron type leads to opposite effects. This study demonstrates that inhibitory interneuron activity can control behavioral sensory discrimination acuity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Letzkus JJ, Wolff SB, Meyer EM, Tovote P, Courtin J, Herry C, Luthi A. A disinhibitory microcircuit for associative fear learning in the auditory cortex. Nature. 2011;480:331–335. doi: 10.1038/nature10674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Znamenskiy P, Zador AM. Corticostriatal neurons in auditory cortex drive decisions during auditory discrimination. Nature. 2013;497:482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marlin BJ, Mitre M, D'Amour JA, Chao MV, Froemke RC. Oxytocin enables maternal behaviour by balancing cortical inhibition. Nature. 2015;520:499–504. doi: 10.1038/nature14402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schreiner CE. Functional organization of the auditory cortex: maps and mechanisms. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1992;2:516–521. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90190-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Depireux DA, Simon JZ, Klein DJ, Shamma SA. Spectro-temporal response field characterization with dynamic ripples in ferret primary auditory cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;85:1220–1234. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wehr M, Zador AM. Balanced inhibition underlies tuning and sharpens spike timing in auditory cortex. Nature. 2003;426:442–446. doi: 10.1038/nature02116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore AK, Wehr M. Parvalbumin-expressing inhibitory interneurons in auditory cortex are welltuned for frequency. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:13713–13723. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0663-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li LY, Ji XY, Liang F, Li YT, Xiao Z, Tao HW, Zhang LI. A feedforward inhibitory circuit mediates lateral refinement of sensory representation in upper layer 2/3 of mouse primary auditory cortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014;34:13670–13683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1516-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J, Caspary D, Salvi RJ. GABA-A antagonist causes dramatic expansion of tuning in primary auditory cortex. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1137–1140. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200004070-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, McFadden SL, Caspary D, Salvi R. Gamma-aminobutyric acid circuits shape response properties of auditory cortex neurons. Brain Res. 2002;944:219–231. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02926-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen QC, Jen PH. Bicuculline application affects discharge patterns, rate-intensity functions, and frequency tuning characteristics of bat auditory cortical neurons. Hear Res. 2000;150:161–174. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan AY, Wehr M. Balanced tone-evoked synaptic excitation and inhibition in mouse auditory cortex. Neuroscience. 2009;163:1302–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oswald AM, Schiff ML, Reyes AD. Synaptic mechanisms underlying auditory processing. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu GK, Arbuckle R, Liu BH, Tao HW, Zhang LI. Lateral sharpening of cortical frequency tuning by approximately balanced inhibition. Neuron. 2008;58:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SH, Kwan AC, Dan Y. Interneuron subtypes and orientation tuning. Nature. 2014;508:E1–2. doi: 10.1038/nature13128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39**.Atallah BV, Bruns W, Carandini M, Scanziani M. Parvalbumin-expressing interneurons linearly transform cortical responses to visual stimuli. Neuron. 2012;73:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.013. Bidirectional modulation of parvalbumin-positive interneurons in the visual cortex provides a linear shift in responses of cortical neurons, only modestly affecting their tuning properties. This study supports the view of parvalbumin-positive interneurons as facilitating gain modulation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adesnik H, Bruns W, Taniguchi H, Huang ZJ, Scanziani M. A neural circuit for spatial summation in visual cortex. Nature. 2012;490:226–231. doi: 10.1038/nature11526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang S, Xu M, Kamigaki T, Hoang Do JP, Chang WC, Jenvay S, Miyamichi K, Luo L, Dan Y. Selective attention. Long-range and local circuits for top-down modulation of visual cortex processing. Science. 2014;345:660–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1254126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Boustani S, Sur M. Response-dependent dynamics of cell-specific inhibition in cortical networks in vivo. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5689. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamilton LS, Sohl-Dickstein J, Huth AG, Carels VM, Deisseroth K, Bao S. Optogenetic activation of an inhibitory network enhances feedforward functional connectivity in auditory cortex. Neuron. 2013;80:1066–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44*.Phillips EA, Hasenstaub AR. Asymmetric effects of activating and inactivating cortical interneurons. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.18383. This paper proposes a straightforward framework for understanding and interpreting heterogeneous effects of activitating or inhibiting different interneuron subtypes on tone-evoked responses in the auditory cortex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45*.Sturgill JF, Isaacson JS. Somatostatin cells regulate sensory response fidelity via subtractive inhibition in olfactory cortex. Nature neuroscience. 2015;18:531–535. doi: 10.1038/nn.3971. This study demonstrates that SOMs regulate odor-evoked responses in piriform cortex via subtractive inhibition, through suppression of both excitatory neurons and PVs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46*.Ayzenshtat I, Karnani MM, Jackson J, Yuste R. Cortical Control of Spatial Resolution by VIP+ Interneurons. J Neurosci. 2016;36:11498–11509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1920-16.2016. Activating interneurons expressing vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIPs) drove stronger response to stimuli with higher spatial frequency, as compared to lower spatial frequency, thereby controlling not simply the amplitude of cortical responses, but their stimulus sensitivity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nelson A, Mooney R. The Basal Forebrain and Motor Cortex Provide Convergent yet Distinct Movement-Related Inputs to the Auditory Cortex. Neuron. 2016;90:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsodyks MV, Skaggs WE, Sejnowski TJ, McNaughton BL. Paradoxical effects of external modulation of inhibitory interneurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4382–4388. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04382.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Litwin-Kumar A, Rosenbaum R, Doiron B. Inhibitory stabilization and visual coding in cortical circuits with multiple interneuron subtypes. J Neurophysiol. 2016;115:1399–1409. doi: 10.1152/jn.00732.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50*.Niell CM, Stryker MP. Modulation of visual responses by behavioral state in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2010;65:472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.033. Neuronal responses in the visual cortex to visual stimuli were elevated during locomotion, with some PVs exhibiting differential effects. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Polack PO, Friedman J, Golshani P. Cellular mechanisms of brain state-dependent gain modulation in visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1331–1339. doi: 10.1038/nn.3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reimer J, Froudarakis E, Cadwell CR, Yatsenko D, Denfield GH, Tolias AS. Pupil fluctuations track fast switching of cortical states during quiet wakefulness. Neuron. 2014;84:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu Y, Tucciarone JM, Espinosa JS, Sheng N, Darcy DP, Nicoll RA, Huang ZJ, Stryker MP. A cortical circuit for gain control by behavioral state. Cell. 2014;156:1139–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jackson J, Ayzenshtat I, Karnani MM, Yuste R. VIP+ interneurons control neocortical activity across brain states. J Neurophysiol. 2016;115:3008–3017. doi: 10.1152/jn.01124.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pakan JM, Lowe SC, Dylda E, Keemink SW, Currie SP, Coutts CA, Rochefort NL. Behavioral-state modulation of inhibition is context-dependent and cell type specific in mouse visual cortex. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.14985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou M, Liang F, Xiong XR, Li L, Li H, Xiao Z, Tao HW, Zhang LI. Scaling down of balanced excitation and inhibition by active behavioral states in auditory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:841–850. doi: 10.1038/nn.3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nelson A, Schneider DM, Takatoh J, Sakurai K, Wang F, Mooney R. A circuit for motor cortical modulation of auditory cortical activity. J Neurosci. 2013;33:14342–14353. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2275-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58**.Schneider DM, Nelson A, Mooney R. A synaptic and circuit basis for corollary discharge in the auditory cortex. Nature. 2014;513:189–194. doi: 10.1038/nature13724. This paper demonstrated that direct corollary projections from neurons in secondary areas of motor cortex innervate auditory cortex directly immediately prior to movement. These projections target PV interneurons in auditory cortex which in turn inhibit excitatory neurons during locomotion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kawaguchi Y. Selective cholinergic modulation of cortical GABAergic cell subtypes. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:1743–1747. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.3.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eggermann E, Kremer Y, Crochet S, Petersen CC. Cholinergic signals in mouse barrel cortex during active whisker sensing. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1654–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gentet LJ, Kremer Y, Taniguchi H, Huang ZJ, Staiger JF, Petersen CC. Unique functional properties of somatostatin-expressing GABAergic neurons in mouse barrel cortex. Nature neuroscience. 2012;15:607–612. doi: 10.1038/nn.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McGinley MJ, David SV, McCormick DA. Cortical Membrane Potential Signature of Optimal States for Sensory Signal Detection. Neuron. 2015;87:179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pinto L, Goard MJ, Estandian D, Xu M, Kwan AC, Lee SH, Harrison TC, Feng G, Dan Y. Fast modulation of visual perception by basal forebrain cholinergic neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1857–1863. doi: 10.1038/nn.3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hangya B, Ranade SP, Lorenc M, Kepecs A. Central Cholinergic Neurons Are Rapidly Recruited by Reinforcement Feedback. Cell. 2015;162:1155–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65*.Kuchibhotla KV, Gill JV, Lindsay GW, Papadoyannis ES, Field RE, Sten TA, Miller KD, Froemke RC. Parallel processing by cortical inhibition enables context-dependent behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:62–71. doi: 10.1038/nn.4436. Task engagement led to suppression or facilitation of neurons in the auditory cortex, with specific interneuron subtypes, SOMs and VIPs, being more strongly affected than PVs. This modulation is potentially facilitated by disinhibition through activation of cholinergic projections. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zeisel A, Munoz-Manchado AB, Codeluppi S, Lonnerberg P, La Manno G, Jureus A, Marques S, Munguba H, He L, Betsholtz C, et al. Brain structure. Cell types in the mouse cortex and hippocampus revealed by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2015;347:1138–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wimmer RD, Schmitt LI, Davidson TJ, Nakajima M, Deisseroth K, Halassa MM. Thalamic control of sensory selection in divided attention. Nature. 2015;526:705–709. doi: 10.1038/nature15398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karnani MM, Jackson J, Ayzenshtat I, Hamzehei Sichani A, Manoocheri K, Kim S, Yuste R. Opening Holes in the Blanket of Inhibition: Localized Lateral Disinhibition by VIP Interneurons. J Neurosci. 2016;36:3471–3480. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3646-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cottam JC, Smith SL, Hausser M. Target-specific effects of somatostatin-expressing interneurons on neocortical visual processing. J Neurosci. 2013;33:19567–19578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2624-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ocker GK, Litwin-Kumar A, Doiron B. Self-Organization of Microcircuits in Networks of Spiking Neurons with Plastic Synapses. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee JH, Koch C, Mihalas S. A Computational Analysis of the Function of Three Inhibitory Cell Types in Contextual Visual Processing. Front Comput Neurosci. 2017;11:28. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2017.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang GR, Murray JD, Wang XJ. A dendritic disinhibitory circuit mechanism for pathway-specific gating. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12815. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dimidschstein J, Chen Q, Tremblay R, Rogers SL, Saldi GA, Guo L, Xu Q, Liu R, Lu C, Chu J, et al. A viral strategy for targeting and manipulating interneurons across vertebrate species. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1743–1749. doi: 10.1038/nn.4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]