Abstract

Background

While the overall smoking quit rate has increased over time, it is not known whether the quit rate has also increased among persons with alcohol use disorders (AUDs) or heavy alcohol use (HAU). The current study examined quit rates among adults with and without AUDs and HAU over a 12-year period in a representative sample of US adults.

Methods

Data were drawn from the National Household Survey on Drug Use, an annual cross-sectional study of US persons. Quit rate (i.e., the rate of former smokers to ever smokers) was calculated annually from 2002 to 2014 (for HAU) and 2015 (for AUD). Time trends in quit rates by AUD/HAU status were tested using linear regression.

Results

The prevalence of past-month cigarette smoking was much higher for persons with, compared to without, AUDs (38% vs. 18%) and HAU (49% vs. 19%). In the most recent data year, the quit rate for persons with AUDs was approximately half that of persons without AUDs (26% versus 49%) and for persons with HAU was less than half that of persons without HAU (22% versus 48%). Over time, the smoking quit rate increased for persons with and without AUDs/HAU and the rate of increase was greater for persons with AUDs/HAU. Yet, quit rates for persons with AUDs and HAU remained much lower than persons without AUDs and HAU.

Conclusions

It may be beneficial for public health and clinical efforts to incorporate screenings and treatment for tobacco use into programs for adults with AUDs and HAU.

Keywords: smoking, cessation, alcohol use disorders, heavy alcohol use, epidemiology

1. Introduction

Tobacco use is responsible for enormous societal burden in the United States (US) and is a leading cause of mortality around the world (USDHHS, 2014; WHO, 2012). Cigarette smoking appears substantially more common among adults with alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and heavy alcohol use (HAU) and both AUD and HAU appear to be associated with lower rates of smoking cessation (Falk et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2015; Weinberger et al., 2016). For example, cross-sectional data from US adults suggest lower quit rates among adults with AUDs compared to those without psychiatric or substance use disorders (Smith et al., 2014) and among heavy drinkers compared to lighter drinkers or abstainers (Dawson, 2000). The majority of studies on quitting among adults with AUDs and HAU have estimated quit rate at a single time period cross-sectionally. It therefore remains unclear whether quit rates for adults with AUDs and HAU have increased over time and in a manner that is comparable to quit rates among those without AUDs/HAU. Understanding the degree to which all groups—especially those vulnerable to continued cigarette use—are benefitting equally from tobacco control efforts can inform next steps in terms of the potential need for additional or more targeted public health and clinical efforts for persons with AUDs and HAU.

The purpose of the current study was to examine the quit rate among adults with and without AUDs and HAU over a 12-year period in a representative sample of US adults. The first aim was to compare the quit rate among adults with and without AUDs and HAU in the most recent data year. The second aim was to examine trends in quit rates from 2002 to 2014/2015 among adults with and without AUDs and HAU.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Population

Study data were drawn from The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) public data portal (http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/) for the years 2002 to 2015. The NSDUH provides annual cross-sectional national data on the use of tobacco, other substance use, and mental health in the US and is described in depth elsewhere (SAMHSA, 2014). A multistage area probability sample for each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia was conducted to represent the male and female civilian non-institutionalized US population aged 12 and older. The datasets from each year were concatenated, adding a variable for the survey year. Because the assessment of HAU changed when data were collected in 2015, data are presented for HAU from 2002 to 2014 and for AUDs from 2002 to 2015. For this study, the analyses were restricted to participants who were 18 years old or older and who met criteria for lifetime smoking (unweighted n=222,967) from 2002 to 2015.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

Demographic variables were categorized as follows: age (18 to 20 years old as reference, 21 to 25 years old, 26 to 34 years old, 35 to 49 years old, 50 to 64 years old, 65 years or older), gender (male as reference, female), total annual family income (<$20,000 as reference, $20,000 to $49,999, $50,000 to $74,999, $75,000 or more), education (less than high school as reference, high school graduate, some college, college graduate), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White as reference, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Native American/Alaskan Native, non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic more than one race, Hispanic) and marital status (married as reference, widowed, separated or divorced, never married).

2.2.2. Alcohol Use Variables

Past-year AUDs (alcohol dependence or alcohol abuse) were assessed in each annual survey by computer-assisted interviewing instrumentation based on DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994). Alcohol abuse was defined as meeting one or more of four alcohol abuse criteria in the past 12 months and not meeting criteria for alcohol dependence in the past 12 months. Alcohol dependence was defined as meeting three or more of seven alcohol dependence criteria. Respondents who met criteria for past-year alcohol abuse or dependence were classified has having a past-year AUD. Detailed alcohol abuse and dependence criteria were described in NSDUH 2015 Codebook (Appendix D Recoded Substance Dependence and Abuse Variable Documentation section; SAMHSA, 2015). Past-month HAU was defined for all participants (i.e., men and women) as drinking five or more drinks on the same occasion on each of 5 or more days in the past 30 days. AUD and HAU were not mutually exclusive categories.

2.2.3. Smoking Status and Quit Rate

Respondents were classified as ever smokers if they reported having smoked 100 or more lifetime cigarettes. Respondents were classified as former smokers if they reported having smoked 100 or more lifetime cigarettes and no cigarette smoking in the past year. The Quit Rate was calculated as the rate of former to ever smokers and is considered a measure of total cessation in a population.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed incorporating the NSDUH sampling weights and controlling for the complex clustered sampling using SAS-callable SUDAAN Version 11.0.1(RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC; http://www.rti.org/sudaan/). First, demographic characteristics were examined by AUD status in the most recent data year. Chi-square tests were then performed to assess the statistical significance of associations between demographics and AUD status. Second, the weighted number of former and ever smokers by past-year AUD status (AUD, no AUD) were calculated for each year from 2002 to 2015. Quit rates were then calculated as the ratio of former to ever smokers for those with and without AUDs. Time trends in the quit rates by AUD status were tested using linear regression with continuous year as the predictor for the linear time trend. These analyses were conducted twice: first with no covariates (unadjusted) and then adjusting for age, gender, income, education, race/ethnicity and marital status. To examine whether time trends in quit rate differed by AUD status, linear regressions included the 2-way interaction of survey year X AUD status (past-year AUD versus no past-year AUD). All analyses described above were repeated with HAU in place of AUD.

3. Results

3.1. Analytic Sample

The prevalence of past month cigarette smoking among persons with AUDs was approximately twice that among persons without AUDs in 2015 (38% vs. 18%) and more than twice as common among persons with HAU—with almost half reporting current smoking—compared with those without HAU in 2014 (49% vs. 19%; see Supplemental Table 11 for demographics and smoking status by AUD/HAU).

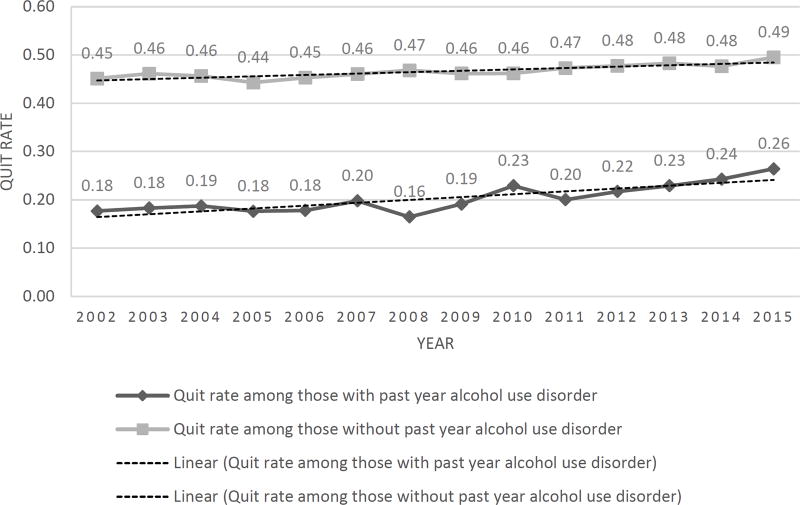

3.2. Quit Rate by AUD Status

For each year of the study, the quit rate was lower for adults with AUDs compared to adults without AUDs (see Figure 1). In 2002 and 2015, the quit rate among those with AUDs was approximately half that of those without AUDs (2002: 20% versus 47%; 2015: 26% versus 49%). Controlling for demographics, there was a significant increase in the quit rate from 2002 to 2015 for both those with AUDs (adjusted beta=0.00601, 95% CI=0.00599–0.00603, p<0.001) and withou AUDs (adjusted beta=0.00292, 95% CI=0.00291–0.00293, p<0.001). There was a significant interaction such that rate of increase was significantly more rapid among those with AUDs relative to those without AUDs (F=18366, df=1, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Quit rates for adults with and without past-year alcohol use disorders from 2002 to 2015. Note: Quit rate was defined as the ratio of former smokers to ever smokers.

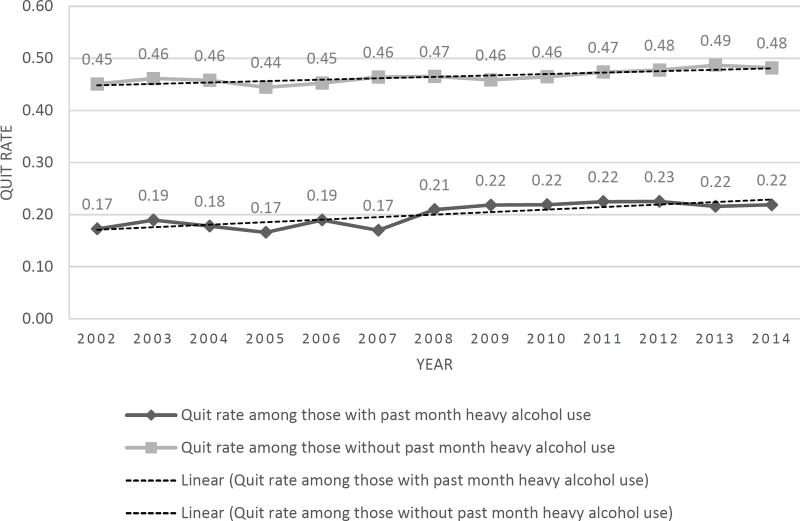

3.3. Quit Rate by HAU Status

For each year of the study, the quit rate was lower among adults with HAU compared to those without HAU (see Figure 2). In 2002 and 2014, the quit rate among adults with HAU was less than half of that among adults without HAU (2002: 20% versus 46%; 2014: 22% versus 48%). Controlling for demographics, there was a significant increase in the quit rate from 2002 to 2014 for both adults with HAU (adjusted beta=0.00484, 95% CI=0.00482–0.00485, p<0.001) and without HAU (adjusted beta=0.00263, 95% CI=0.00262–0.00263, p<0.001). There was a significant itnteraction such that rate of increase in quit rate was more rapid among those with HAU compared to those without HAU (F=9784, df=1, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Quit rates for adults with and without past-month heavy alcohol use from 2002 to 2014. Note: Quit rate was defined as the ratio of former smokers to ever smokers.

4. Discussion

This study was the first to use representative data from the US population to examine quit rates over time among adults with and without AUDs/HAU. Between 2002 and 2014/2015, the smoking quit rate increased for adults with and without AUDs and HAU and the rate of increase in quitting over time was more rapid among persons with AUDs/HAU relative to persons without AUDs/HAU. Yet, quit rates for adults with AUDs and HAU were consistently half those of adults without AUDs and HAU and, also notably, the prevalence of current smoking remained approximately twice as high among those with AUDs/HAU relative to those without.

In some ways, it is indeed encouraging that the speed of quit rate increase among those with AUDs/HAU exceeded those without AUDs/HAU; however, despite this, smoking remains common among almost half of those with HAU and nearly 40% of those with AUDs and the most recent quit rates remain at one-half or less than half of persons without AUDs/HAU. Still, this decline suggests that tobacco control efforts may be reaching persons with AUDs/HAU. Yet, the persistent disparity in smoking prevalence among those with and without AUDs/HUA suggest that continued attention to smoking cessation among people with problematic alcohol consumption is needed to build on the increases in quit rate and bring the prevalence lower.

Despite concerns, most studies do not find worse outcomes with concurrent smoking and alcohol treatment (see McKelvey et al., 2017 and Thurgood et al., 2016 for recent reviews). In fact, studies suggest greater cravings to use alcohol when smoking cigarettes (see Dermody and Hendershot, 2017 for a review) and smoking may be associated with poorer long-term AUD outcomes (e.g., Weinberger et al., 2015). Notably, some studies have found improved alcohol and drug outcomes when those in treatment for alcohol and substance use disorders are also treated for tobacco use (McKelvey et al., 2017; Thurgood et al., 2016). While smoking cessation has not been historically included in AUD treatment, and has been discouraged in some cases (e.g., the belief that quitting smoking would be too stressful for adults quitting alcohol), mounting data suggest that efforts to help adults with problematic alcohol use stop using cigarettes, in addition to alcohol, may have positive impacts on health and other alcohol- and smoking-related consequences. Therefore, including adjunctive treatment for tobacco use as the standard of care in treatment for AUD/HAU should be considered.

There are a number of limitations of the current study. First, results may not generalize to adults outside of the analytic sample (e.g., outside the US; younger than 18 years). Second, AUDs were assessed using DSM-IV criteria rather than more recent DSM-5 criteria (APA, 2013). Third, there are multiple definitions of HAU and multiple terms used for heavy consumption (e.g., binge drinking). In addition, the definition of HAU did not include a gender-specific quantity of alcohol consumption. Fourth, we were not able to present data from 2015 for HAU due to changes in the measurement of HAU. Fifth, persons who did not meet the inclusion criteria (e.g., smoked <100 lifetime cigarettes) were omitted from the analyses. Sixth, smoking and alcohol behaviors were documented by self-report and therefore subject to recall bias, underreporting, and reporting errors. Seventh, there were a number of factors potentially related to AUDs/HAU and smoking behavior that were not possible to include as covariates (e.g., depression, other substance use) due to unavailability over this period of time in the NSDUH. Finally, since the data were cross-sectional, it was not possible to study mechanisms underlying the relationship between AUDs/HAU and quit behavior. Use of longitudinal data that follow adults with and without AUDs/HAU over time would be useful to learn about individual trajectories. Longitudinal data would also provide information about the timing of AUDs/HAU and smoking behavior as well as the examination of potential moderators.

4.1. Conclusions

Increased public health and clinical efforts toward increasing quit rates and long-term abstinence among persons with AUDs and HAU are needed as, despite declines in smoking, the prevalence remains nearly twice as high among those with AUDs/HAU compared to the national average. Next steps may include public education efforts on the joint risks of smoking and drinking and clinical efforts toward integrating screening and treatment for tobacco use into programs for adults with alcohol use problems.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We examined quit rates by alcohol use disorder (AUDs) and heavy alcohol use (HAU).

Over time, the smoking quit rate increased for adults with and without AUDs and HAU.

Adults with AUDs/HAU had higher smoking prevalences than adults without AUDs/HAU.

In 2015, the quit rate for AUDs was about half that of adults without AUDs.

In 2014, the quit rate for HAU was less than half that of adults without HAU.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institutes of Health grant R01-DA20892 (to Dr. Goodwin).The NIH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Contributors

Dr. Goodwin conceived the study and wrote sections of the manuscript. Dr. Weinberger helped to design the study, managed the literature searches, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Ms. Gbedmeah undertook the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Weinberger, Ms. Gbedemah, and Dr. Goodwin have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. (DSM-IV) American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. (DSM-5) American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost - United States, 2001. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2004;53:866–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. Drinking as a risk factor for sustained smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59:235–249. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody SS, Hendershot CS. A critical review of the effects of nicotine and alcohol co-administration in human laboratory studies. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2017;41:473–486. doi: 10.1111/acer.13321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk DE, Yi HY, Hiller-Sturmhofel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Res. Health. 2006;29:162–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Gonzalez ME, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Relationship of smokefree laws and alcohol use with light and intermittent smoking and quit attempts among US adults and alcohol users. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0137023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Spillane NS, Metrik J. Alcohol use and initial smoking lapses among heavy drinkers in smoking cessation treatment. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010;12:781–785. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Weinberger AH. How can our knowledge of alcohol-tobacco interactions inform treatment for alcohol use? Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013;9:649–674. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey K, Thrul J, Ramo D. Impact of quitting smoking and smoking cessation treatment on substance use outcomes: An updated and narrative review. Addict. Behav. 2017;65:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.012. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche DJO, Ray LA, Yardley MM, King AC. Current insights into the mechanisms and development of treatments for heavy-drinking cigarette smokers. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2016;3:125–137. doi: 10.1007/s40429-016-0081-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Codebook. SAMHSA; Rockville, MD: 2014. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Codebook. SAMHSA; Rockville, MD: 2015. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Smoking and mental illness in the US population. Tob Control. 2014;23:e147–e153. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurgood SL, McNeill A, Clark-Carter D, Brose LS. A systematic review of smoking cessation interventions for adults in substance abuse treatment or recovery. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2016;18:993–1001. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Funk AP, Goodwin RD. A review of epidemiologic research on smoking behavior among persons with alcohol and illicit substance use disorders. Prev. Med. 2016;92:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Platt J, Jiang B, Goodwin RD. Cigarette smoking and risk of alcohol use relapse among adults in recovery from alcohol use disorders. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2015;39:1989–1996. doi: 10.1111/acer.12840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Global Report: Mortality Attributable to Tobacco. WHO Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.