Abstract

The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway arose early during evolution of eukaryotic cells, when it appears to have been involved in the response to glucose starvation and perhaps also in monitoring the output of the newly acquired mitochondria. Due to the advent of hormonal regulation of glucose homeostasis, glucose starvation is a less frequent event for mammalian cells than for single-celled eukaryotes. Nevertheless, the AMPK system has been preserved in mammals where, by monitoring cellular AMP:ATP and ADP:ATP ratios and balancing the rates of catabolism and ATP consumption, it maintains energy homeostasis at a cell-autonomous level. In addition, hormones involved in maintaining energy balance at the whole body level interact with AMPK in the hypothalamus. AMPK is activated by two widely used clinical drugs, metformin and aspirin, and also by many natural products of plants that are either derived from traditional medicines or are promoted as “nutraceuticals”.

Keywords: energy balance, ghrelin, leptin, metformin, salicylate, traditional medicine

Introduction

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) was discovered independently by two groups in 1973 via its ability to phosphorylate and inactivate two key enzymes of lipid biosynthesis, i.e. acetyl-CoA carboxylase (16) and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase (7). It was subsequently shown that the acetyl-CoA carboxylase kinase activity was allosterically activated by 5'-AMP (181), while the HMG-CoA reductase kinase activity was activated by phosphorylation by a distinct upstream kinase (66). For several years it was assumed that they were independent entities, but in 1987 it was realized that they were functions of a single protein kinase that activated both by AMP and by phosphorylation (15). Since it soon became clear that this was a true multisubstrate kinase, it no longer made sense to name it after any single substrate, and it was renamed AMP-activated protein kinase after its key activating ligand (122).

AMPK – an ancient kinase occurring in essentially all eukaryotes

When mammalian AMPK was finally purified to homogeneity (28; 119), it was found to exist as a heterotrimeric complexes comprising a single catalytic subunit, now termed the α subunit, and two accessory subunits termed β and γ. Cloning of DNAs encoding these from rodents or humans revealed multiple isoforms of each subunit (AMPK-α1/-α2; AMPK-β1/-β2; and AMPK-γ1/-γ2/-γ3 (46). Genes encoding related α, β and γ subunits can be readily recognized in the genome sequences of almost all eukaryotes, including protists, fungi and plants as well as animals. DNAs encoding the subunits of the budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) ortholog (named the SNF1 complex after its catalytic subunit Snf1) had been cloned and sequenced prior to the sequencing of the mammalian DNA (47). When glucose in the medium of S. cerevisiae is high, expression of genes required for growth on other carbon sources and for mitochondrial oxidative metabolism are repressed (glucose repression). Under these conditions the cells grow rapidly using only fermentation (production of ethanol by glycolysis) to generate ATP. As glucose runs out, genes required for metabolism of other fermentable carbon sources are de-repressed if they are available, but if not genes required for oxidative metabolism are de-repressed instead. Following a characteristic lag while the switch to oxidative metabolism occurs (a phenomenon known as the diauxic shift), growth recommences at a slower rate. A functional SNF1 complex is required for the de-repression of genes needed for metabolism of carbon sources other than glucose, as well as for the switch to oxidative metabolism. In its absence, the diauxic shift does not occur during growth on glucose, and growth ceases as soon as glucose runs low (49).

Thus, the ancestral role of AMPK orthologs seems to have been in the response to starvation for a carbon source, and in the switch from the glycolytic metabolism that occurs during rapid cell growth (known in mammals as the Warburg effect), to the more energy-efficient oxidative metabolism used by quiescent or more slowly growing cells. Similar roles appear to have been conserved throughout eukaryotes. For example, in the moss Physcomitrella patens (a green plant), strains lacking AMPK orthologs grow in continuous light, but fail to grow in more physiological light-dark cycles (158). Since darkness is the equivalent of starvation for a green plant, and mitochondrial function is required to make ATP during periods of darkness, this is related to the phenotype of yeast lacking the SNF1 complex. In the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans, the AMPK ortholog is required for extension of lifespan in response to dietary restriction and other stresses (4; 43), once again emphasizing the ancestral role of AMPK in the response to starvation.

It now appears likely that the fundamental event that led to the development of eukaryotes was the acquisition by an archaeal host cell of oxidative bacteria, which developed by endosymbiosis into the mitochondria where ATP is generated much more efficiently using oxidative metabolism than using glycolysis alone. What would also have been valuable at this time would have been a system to monitor the output of the mitochondria and regulate their growth and replication to satisfy the varying demands of the host cell for ATP. By monitoring cellular adenine nucleotides and triggering mitochondrial biogenesis if it detects that these ratios are falling (see below), AMPK fulfills this function. The fact that genes encoding AMPK subunit orthologs are found in the genomes of essentially all eukaryotes suggests that it arose very early during eukaryotic evolution. One interesting exception that “proves the rule” is the microsporidian Cephalitozoon cuniculi, a single-celled eukaryote that lives as an obligate intracellular parasite within other eukaryotic cellss. Its genome encodes only around 2,000 protein-coding genes and a mere 32 protein kinases (compared with 6,000 genes and 120 kinases in S. cerevisiae), and lacks genes encoding AMPK subunits (77; 118). Its genome does appear to encode a complete glycolytic pathway, but not genes for oxidative metabolism, although it does contain remnant mitochondria (77). Intriguingly, it expresses three ATP translocases that have a plasma membrane localization (162). The implication is that the organism uses these to “steal” ATP from the cytoplasm of the host cell, and may have dispensed with AMPK because its host has a functional AMPK pathway that can monitor the demand for ATP on its behalf. It thus seems likely that C. cuniculi, rather than being an ancestral form that never had genes encoding AMPK, represents an organism that has been able to strip its genome down to the bare minimum due to its parasitic existence.

Regulation of AMPK by adenine nucleotides

In all species, AMPK is activated >100-fold by phosphorylation of a conserved threonine residue within the “activation loop” of the kinase domain on the α subunit. This critical phosphorylation site is usually referred to as Thr172 due to its position in the rat catalytic subunit sequences (51). Phosphorylation of Thr172 is primarily catalyzed by a heterotrimeric complex containing the protein kinase LKB1 (50), encoded by a gene in which heterozygous loss-of-function mutations cause a cancer susceptibility condition termed Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Thr172 can also be phosphorylated by the calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase, CaMKKβ (53; 63; 172). This provides an alternate mechanism by which AMPK can be activated by increases in intracellular Ca2+ in the absence of any changes in adenine nucleotides (Fig. 1), although if both activating signals (AMP and Ca2+) are elevated they can act synergistically (34).

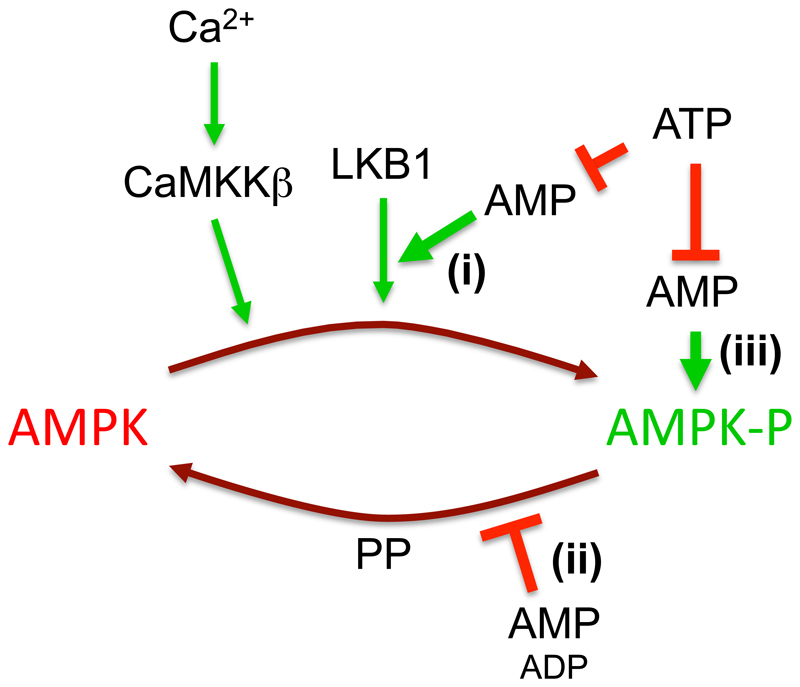

Figure 1. Mechanisms for activation of AMPK by AMP.

AMPK is activated by phosphorylation of Thr172 by the upstream kinases LKB1 and CaMKKβ, a modification that is reversed by protein phosphatases (PP). AMP has three effects caused by binding to one or more of three AMP-binding sites on the AMPK-γ subunit: (i) promoting Thr172 phosphorylation by LKB1; (ii) inhibiting Thr172 dephosphorylation; (iii) causing allosteric activation of the phosphorylated kinase. Only mechanism (ii) is mimicked by binding of ADP, but all three are antagonized by binding of ATP.

Unlike CaMKKβ, the LKB1 complex appears to be constitutively active (145). However, increasing AMP not only causes allosteric activation of AMPK but also promotes phosphorylation of Thr172 by LKB1. It does this not by activating the LKB1 complex (or by inhibiting protein phosphatases) but by binding to the AMPK-γ subunit, causing conformational changes that modulate the phosphorylation status of Thr172 on the α subunit (see below). The AMPK-γ subunits in all species contain four tandem repeats of a sequence known as a cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) repeat. These also occur (usually as just two repeats) in a small number of other proteins in the human genome, and there is evidence that binding of regulatory, adenosine-containing ligands is a common feature of the domains formed by a single pair of repeats (148). The four repeats of the AMPK-γ subunits yield two ligand-binding domains arranged in tandem. X-ray crystallography of partial complexes with complete γ subunits showed that, in species ranging from S. cerevisiae to the distantly related fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe and mammals, the four repeats assemble in a pseudosymmetrical manner, forming a flattened disk with one repeat in each quadrant (2; 161; 174). There are two symmetrical clefts between repeats 1 and 2 (CBS1, CBS2), and two equivalent clefts between CBS3 and CBS4, where the regulatory nucleotides AMP, ADP and ATP could potentially bind. However, in mammalian complexes only three appear to be utilized, with two between CBS3 and CBS4 (sites 3 and 4) and one between CBS1 and CBS2 (site 1), site 2 being unused (18; 174; 176). The original crystallization of a partial αβγ complex of mammalian AMPK was performed in the presence of AMP, when the nucleotide was found in sites 1, 3 and 4; soaking of ATP into these crystals caused replacement of AMP by ATP at sites 1 and 3, but not 4. This led to the designation of site 4 as a “non-exchangeable” site where AMP is permanently bound (174). However, this view has been challenged by a recent study in which a similar partial complex was crystallized in the presence of ATP rather than AMP, which revealed ATP to be bound at sites 1 and 4 (18).

Adenine nucleotides bind to these sites with their adenine moieties deep within the binding clefts, leaving their phosphate groups clustered together at the center of the disk of the γ subunit. Here they are bound by a cluster of basic residues contributed by CBS repeats 1, 2 and 4. Interestingly, mutations in these residues in the AMPK-γ2 subunit (an isoform highly expressed in the heart), which neutralize the positive charge on their side chains, disrupt the binding of adenine nucleotides and consequently cause heart disorders (1; 12; 148).

Binding of AMP to the γ subunit activates AMPK by three distinct mechanisms (summarized in Fig. 1), all of which are antagonized by binding of ATP:

-

i)

Promotion of phosphorylation of Thr172. Although it was recently reported that binding of ADP as well as AMP enhanced the phosphorylation of Thr172 by CaMKKβ (129), this is controversial because others find that only AMP promoted phosphorylation by LKB1, while neither nucleotide promoted phosphorylation by CaMKKβ (42). A possible mechanism by which AMP promotes phosphorylation by LKB1 has been suggested by a recent report that the scaffold protein axin promotes the formation of a complex between the AMPK and LKB1 complexes. This was enhanced by the binding of AMP, but not ADP, and there was no evidence that axin enhanced the binding of AMPK to CaMKKβ (185).

-

ii)

Protection against dephosphorylation of Thr172 by protein phosphatases. Binding of AMP to the AMPK-γ subunits also causes a conformational change that protects Thr172 against dephosphorylation, irrespective of the specific phosphatase utilized. While originally reported only for AMP (29), the effect has more recently been shown to be also caused by binding of ADP (176). However, the effect of AMP was subsequently shown to occur at 10-fold lower concentrations than ADP, and measurement of the changes in these nucleotides in cells treated with a mitochondrial inhibitor suggest that the increases in AMP may cause a larger effect (42).

-

iii)

Allosteric activation of the kinase phosphorylated on Thr172. There is general agreement that ADP does not trigger this effect. Its physiological significance has been questioned (14; 128) on the grounds that the effect was small (usually reported in cell-free assays to be <2-fold) compared with the effect of Thr172 phosphorylation, and that AMP may have difficulty competing with the much higher cellular concentrations of ADP and ATP (≈10-fold and ≈100-fold higher, respectively, than AMP in unstressed cells). However, other groups have recently provided evidence that these views are incorrect (42). Firstly, under appropriate conditions AMP was found to cause >10-fold allosteric activation even at normal physiological concentrations of ATP (5 mM), and at concentrations one to one orders of magnitude lower than ATP. Secondly, careful quantification of the changes in Thr172 phosphorylation in intact cells subject to energy stress showed that they were relatively modest (2- to 4-fold) compared with the >100-fold effects that can be generated in cell-free assays. Finally, it was shown that a large change in phosphorylation of the downstream target acetyl-CoA carboxylase occurred when AMP was elevated in cells expressing a T172D mutant of AMPK, which cannot be phosphorylated at Thr172 yet retains allosteric activation by AMP.

These effects of binding of AMP (or ADP) to the AMPK-γ subunits, all three of which are antagonized by binding of ATP, act in concert to provide a very sensitive mechanism for activation of AMP in response to small increases in the cellular AMP:ATP (or ADP:ATP) ratio.

Regulation of AMPK by metabolic stresses in intact cells

The cellular ADP:ATP ratio increases in response to any treatment that interferes with the production of ATP from ADP by catabolism, or that accelerates energy-consuming reactions that convert ATP to ADP (Fig. 2). However, the AMP:ATP ratio invariably increases by a larger amount than ADP:ATP, due to the adenylate kinase reaction (2ADP ↔ ATP + AMP). In fully energized, unstressed cells, the high ATP:ADP ratio of about 10:1 drives the reaction from right to left (towards ADP), so that AMP concentrations are 100-fold lower than ATP and 10-fold lower than ADP (42). However, in cells under metabolic stress, the increasing ADP:ATP ratio will displace the adenylate kinase reaction from left to right, generating AMP. If the reaction is at equilibrium, the AMP:ATP ratio will vary as the square of the ADP:ATP ratio (48). For example, in human cells treated with a mitochondrial inhibitor, ATP declined only slightly (<20%), the ADP:ATP ratio rose by 2.8-fold, while the AMP:ATP ratio rose by 8-fold (42). Thus, increases in AMP are more sensitive indicators of energy stress than decreases in ATP or increases in ADP, the only problem being that AMP is normally present at much lower concentrations than ADP or ATP. This is partially offset by the fact that AMP is ten-fold more potent that ADP in protecting against dephosphorylation (the only one of the three mechanisms mimicked by ADP). Competition by the high cellular concentrations of ATP is also partly alleviated by the fact that most cellular ATP, unlike ADP and AMP, is bound to Mg2+ ions in the form of a Mg.ATP2- complex, which binds to the AMPK-γ subunit with much lower affinity than the free ATP4- complex (176). Thus, AMP and ADP may only have to compete with the low proportion of ATP present as free ATP4-, rather than with total ATP.

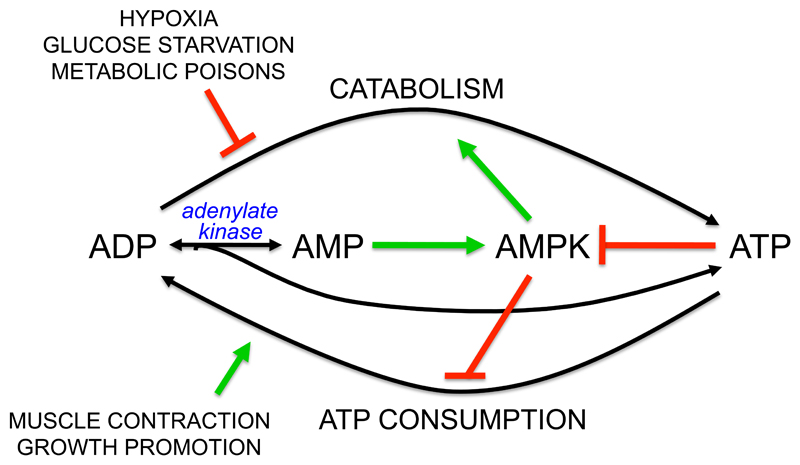

Figure 2. Mechanism by which AMPK maintains cellular energy homoeostasis in mammalian cells.

Catabolism generates ATP from ADP, whereas energy-requiring cellular processes mainly convert ATP to ADP. If ATP consumption exceeds ATP production, the ADP:ATP ratio rises and this is converted by adenylate kinase into an even larger rise in AMP:ATP ratio, activating AMPK. AMPK attempts to restore energy homeostasis by activating catabolism and inhibiting ATP consumption.

Interestingly, AMP appears not to be the primary signal that regulates the SNF1 complex in S. cerevisiae, where binding of ADP, but not AMP, protects against dephosphorylation of the residue equivalent to Thr172 (110). The complexes in fungi or plants, unlike those in animal cells, are also not allosterically activated by AMP. The regulation of the system by AMP rather than ADP, and the allosteric activation by AMP that generates a larger response to energy stress, may have been refinements that evolved during the evolution of the animal kingdom.

Activation of AMPK by metabolic stress in vivo

As expected from the discussion in the previous section, mammalian AMPK is activated by various metabolic stresses (Fig. 2) such as interruption of the blood supply (ischemia) (90), or deprivation of cells for oxygen (hypoxia) (108; 109) or glucose (hypoglycemia) (147). The latter is reminiscent of the ancestral role of AMPK in responding to starvation for glucose, still observed today in unicellular eukaryotes such as S. cerevisiae. In multicellular organisms with hormonal mechanisms that ensure glucose homeostasis, glucose deprivation would be a rare, pathological event for most cells. However, there are specialized “glucose-sensing cells” (such as the β cells of the pancreas and certain neurons in the hypothalamus) in which expression of low affinity isoforms of glucose transporters and hexokinase mean that catabolism and hence ATP levels are depressed, and AMPK activated, by quite small reductions in blood glucose. For example, AMPK modulates glucose sensing and insulin release in pancreatic β cells (143), and also appears to be important in sensing hypoglycemia in glucose-sensing neurons of the hypothalamus, when it triggers activation of the sympathetic nervous system and hence the counter-regulatory secretion of epinephrine and glucagon (22; 111) (Fig. 3). The latter hormones act to restore glucose homeostasis following hypoglycemia by activating glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis in the liver.

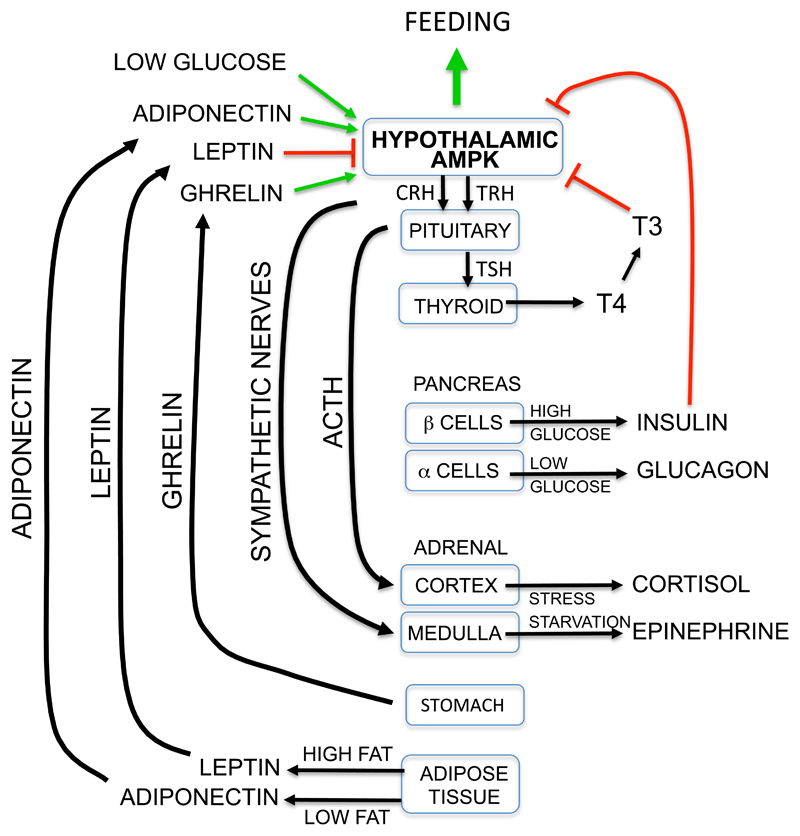

Figure 3. Role of AMPK in the hypothalamus in regulating whole body energy balance.

The diagram summarizes some of the many hormonal controls that control whole body energy balance, emphasizing the central role of AMPK in hypothalamic neurons (see text for details).

Another type of metabolic stress that activates AMPK by accelerating ATP consumption in skeletal (171) or cardiac (24) muscle is increased contraction caused by exercise (Fig. 2). Artificial activation of AMPK in skeletal muscle using the pharmacological activator 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside (AICAR) mimics many of the acute metabolic changes observed in skeletal muscle during acute exercise, as well as many of the longer-term adaptations produced in muscle in response to regular exercise (i.e. training). The acute changes include increased fatty acid oxidation and increased glucose uptake due to translocation of GLUT4 to the plasma membrane (91; 113), while the longer-term adaptations include increased expression of GLUT4 and hexokinase, and increased mitochondrial biogenesis (57; 188). Chronic treatment of rodents with AICAR over several weeks also increases muscle glycogen content (57) and improves exercise endurance (124). These findings have led to the view that AMPK may mediate many, if not all, of the metabolic effects of regular exercise, which is supported by most, if not all, studies with transgenic or knockout mice. Thus, increased AICAR-stimulated glucose uptake was abolished in mice with a skeletal muscle-specific knockout of AMPK-α2, but contraction-stimulated glucose uptake was not affected; a whole body knockout of AMPK-α1 had no effect on either response (74) (when interpreting these studies, it should be borne in mind that experiments with mice lacking both catalytic subunits in muscle have not yet been reported). By contrast, in transgenic mice expressing an inactive AMPK-α2 mutant (which acts as a dominant negative mutant by binding to the available β and γ subunits) (121), or mice with a muscle-specific knockout of the upstream kinase LKB1 (146), contraction-induced glucose uptake was reduced, although not completely eliminated. The most convincing support for a role for AMPK came from studies with mice lacking both AMPK-β subunit isoforms in muscle. These mice had a drastically reduced capacity for treadmill exercise associated with a reduced muscle content of mitochondria. Muscle glucose uptake in response to either exercise in vivo, or electrical stimulation in vitro, was also blunted (126). These results suggest that AMPK is a major player in mediating the metabolic changes that occur in muscle during contraction or exercise, many of which are believed to be beneficial to health in that they protect against metabolic disorders like insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

Effects of AMPK activation on metabolism and other cell functions

Although discovered for its ability to acutely phosphorylate and inactivate key enzymes of lipid biosynthesis (7; 16), it is now clear that AMPK has both acute and longer term effects on almost all central metabolic pathways, as well as many other key cellular functions. In general, AMPK activates catabolic pathways that provide alternate routes to generate ATP (Table 1), while switching off anabolic pathways (Table 2) and other ATP-consuming processes that are not essential for short-term survival of cells.

Table 1.

Activating effects of AMPK on catabolic pathways. Question marks indicate that the target responsible for the overall effect on the pathway has not been completely elucidated.

| Pathway | Direct target (if known) | Overall effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| glucose uptake | TXNIP? | ↑ membrane localization of GLUT1 | (37; 173) |

| glucose uptake | TBC1D1? | ↑ membrane translocation of GLUT4 | (91; 133) |

| glucose uptake | histone deacetylase-4, -5, -7? | ↑ transcription of GLUT4 mRNA | (112; 114) |

| fatty acid uptake | ? | ↑ membrane translocation of fatty acid transporter CD36 | (45) |

| fatty acid oxidation | acetyl-CoA carboxylase-2 | ↓ enzyme activity ↓ malonyl-CoA ↑ mitochondrial transport of fatty acids |

(113) |

| lipolysis* (adipocytes) | hormone-sensitive lipase | ↓ activation by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase | (27; 39) |

| glycolysis | 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase (PFKFB2/PFKFB3) | ↑ activity | (108; 109) |

| mitochondrial biogenesis | PGC-1α? SIRT1? | ↑ expression (PGC-1α) ↑ activity (SIRT1) |

(13; 68) |

| autophagy | ULK1 | ↑ promotion of autophagy | (31; 142) |

Lipolysis seems to be an exception in this Table, in that while it can be regarded as a catabolic pathway, it is inhibited rather than activated by AMPK activation. However, if fatty acids released by lipolysis are not rapidly metabolized or exported from the cell, they recycle back into triglycerides, consuming two molecules of ATP per molecule of fatty acid. Inhibition of lipolysis by AMPK may be a mechanism to prevent the rate of lipolysis from exceeding the rate at which the resulting fatty acids can be removed from the cell by metabolism or export.

Table 2.

Inhibitory effects of AMPK on anabolic pathways. Question marks indicate that the target responsible for the overall effect on the pathway has not been completely elucidated.

| Pathway | Direct target (if known) | Overall effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| fatty acid synthesis | acetyl-CoA carboxylase-1 | ↓ enzyme activity | (23; 30) |

| fatty acid synthesis | SREBP1 | ↓ cleavage to mature nuclear form | (100) |

| sterol synthesis | HMG-CoA reductase | ↓ enzyme activity | (23; 40) |

| triglyceride, phospholipid synthesis | glycerolphosphate acyl transferase? | ↓ enzyme activity | (123) |

| glycogen synthesis | glycogen synthase, GYS1/2 | ↓ enzyme activity (without G6P) | (11; 73) |

| gluconeogenesis | CRTC2? HDAC4/5/7? | ↓ transcription | (87; 114) |

| rRNA synthesis | TIF-1A | ↓ transcriptional activity | (58) |

| protein synthesis | TSC2, Raptor | ↓ initiation of translation | (44; 67) |

| protein synthesis | elongation factor-2 kinase? | ↓ elongation of translation | (9) |

One important cellular process recently shown to be activated by AMPK is autophagy. By engulfing bulk cytosol and organelles in vesicles that are targeted to lysosomes, where their contents are degraded, autophagy consumes cell contents that are surplus to requirements to recycle crucial components like amino acids. Autophagy is a general response to starvation, and is regulated by the AMPK ortholog in S. cerevisiae (169). In mammalian cells, a specialized form of autophagy termed mitophagy is the process by which the contents of damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria are recycled, and this is also enhanced by AMPK (31). Since AMPK promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, mitophagy can be regarded as another aspect of the function of AMPK to maintain the overall ATP-generating capacity of cells. An initial trigger for autophagy in mammalian cells appears to be the phosphorylation by AMPK of the kinase ULK1 (31; 83), which then phosphorylates and activates VPS34, a class III phosphatidylinositol (PI) kinase that generates PI 3-phosphate (PI3P) (142). This recruits to the membrane proteins containing PI3P-binding domains, which mediate subsequent membrane trafficking events. VPS34 occurs in several distinct complexes; AMPK appears to activate those complexes involved in autophagy by phosphorylating beclin-1, while inhibiting those involved in other membrane trafficking events by phosphorylating VPS34 itself; this switch depends on the presence of a third component, Atg14L, in the former complex (82). Thus, AMPK may divert membrane traffic (an energy-requiring process) towards the autophagy/mitophagy pathway, and away from other membrane trafficking events that may be a luxury in cells experiencing energy stress.

Regulation by hormones controlling whole body energy balance

As discussed earlier, AMPK appears to have evolved early in the evolution of unicellular eukaryotes as a signaling pathway that orchestrated responses to glucose starvation, and in specialized glucose-sensing cells in the pancreas and the hypothalamus it is still activated by hypoglycemia (22; 111). While the system may have originally evolved to maintain energy homeostasis in a cell-autonomous manner, it is intriguing that hormones that modulate energy balance at the whole body level, which clearly arose later during the evolution of multicellular organisms, appear to have adapted to interact with the AMPK system, especially in the hypothalamus (Fig. 3).

A good example of this is the hormone ghrelin, an acylated peptide released from cells of the stomach during fasting that acts as a “hunger signal” to promote feeding. Ghrelin receptors co-localize in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus with NPY/AgRP neurons that express neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein (170), which are required for ghrelin action (106). Measurement of the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents in the NPY/AgRP neurons suggests that ghrelin activates AMPK not in the NPY/AgRP neurons themselves, but in presynaptic neurons. Pharmacological evidence suggests that this is mediated by the release, triggered by the ghrelin receptor, of inositol trisphosphate and hence Ca2+, activating AMPK via the CaMKKβ pathway (179). The involvement of CaMKKβ is supported by findings that CaMKK inhibitors depress appetite in wild type but not CaMKKβ knockout mice (3). Once ghrelin has activated AMPK, the latter is proposed to activate ryanodine receptors (RyR) that trigger further Ca2+ release, setting up a positive feedback loop (AMPK → RyR → Ca2+ → CaMKK → AMPK) that supports continued Ca2+-dependent release of neurotransmitter onto the NPY/AgRP neurons (and hence feeding), even after ghrelin release has stopped (179). Operation of this positive feedback loop might explain why most people continue eating a meal even after the initial hunger pangs have subsided; cessation of feeding appears to require instead the action of a distinct “satiety signal”, with leptin and insulin being prime candidates.

Leptin is a polypeptide hormone released from adipocytes, and can be regarded as a “satiety” signal indicating that adipose tissue triglyceride stores are replete (36). It increases energy expenditure in the longer term by stimulating firing of sympathetic nerves, which activates muscle AMPK (117). Somewhat paradoxically, leptin has the opposite effect in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (Fig. 3), where it has been reported to inhibit AMPK-α2 (116). The mechanism underlying this inhibitory effect remains uncertain, although it has recently been proposed that leptin triggers release from pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) -expressing neurons of an opioid (most likely β-endorphin) that acts via μ-opioid receptors to inhibit AMPK in the presynaptic neurons upstream of the NPY/AgRP neurons. By interrupting the positive feedback loop that had been set up by ghrelin, leptin would terminate stimulation of the NPY/AgRP neurons, and thus feeding (179). If this model is correct, the critical pool of AMPK is in the presynaptic neurons (whose exact identity remains uncertain) rather than in the POMC or NPY/AgRP neurons themselves. This would explain why knocking out AMPK in either of the latter neuronal types failed to abolish the anorexigenic effects of leptin (22).

An alternative proposal to explain how leptin inhibits AMPK in the hypothalamus is via activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) → Akt → mechanistic target-of-rapamycin complex-1 (mTORC1) → S6 kinase I (S6KI) pathway. S6KI has been reported to phosphorylate AMPK-α2 at Ser491 in cell-free assays (26); phosphorylation of the equivalent site in the C-terminus of AMPK-α1 has been shown to inhibit subsequent phosphorylation of Thr172, and consequent activation, by LKB1 (55; 59). Since stimulation of μ-opioid receptors has also been reported to activate the PI3K-Akt-mTORC1-S6KI pathway (134), this model could be combined with the one described in the previous paragraph. An attractive feature of this model is that insulin, which is released after eating a carbohydrate meal and represses appetite like leptin, also activates the PI3K → Akt → mTORC1 → S6KI pathway and could therefore work via the same mechanism.

Adiponectin is another polypeptide hormone secreted by adipocytes but, in contrast to leptin, high plasma adiponectin levels are observed in lean rather than obese individuals, suggesting that it is released when stores of triglyceride in adipose tissue are low. It binds to two related receptors, AdipoRI and AdipoRII (75), and binding to AdipoRI activates AMPK by an unknown mechanism, thus promoting fat oxidation in liver and muscle, and inhibiting glucose production in the liver (177). Adiponectin also increases appetite by activating AMPK in the hypothalamus (Fig. 3), mimicking the effect of ghrelin and opposing the effects of leptin (89).

Another hormone that regulates whole body energy homeostasis is tri-iodothyronine (T3). This thyroid hormone binds to nuclear receptors that regulate transcription, and has effects on most cells. However, a major effect (Fig. 3) involves inhibition of AMPK in neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus (105). Like the inhibitory effect of leptin, this promotes firing of sympathetic nerves that trigger release of norepinephrine and epinephrine at peripheral sites. This in turn increases energy expenditure by stimulating release by lipolysis in white adipocytes of fatty acids, which are then oxidized in other tissues, or by promoting fat oxidation and heat production in brown adipocytes (105).

Activation of AMPK by drugs already in regular clinical use

Given that AMPK activation diverts metabolism towards catabolic processes such as the uptake and oxidation of glucose and fatty acids, and away from synthesis and storage of energy reserves such glycogen and triglycerides, drugs that activate AMPK might be expected to be useful in treatment of metabolic disorders such as Type 2 diabetes (46). Type 2 diabetes is believed to be primarily caused by insulin resistance, and there is a well-known correlation between insulin resistance and excessive storage of lipids, especially di- and tri-glycerides, in tissues such as liver and muscle (33; 78). By promoting fat oxidation in liver and muscle, and inhibiting fat synthesis in the liver and lipolysis in adipocytes, activation of AMPK would be expected to reduce storage of di- and triglycerides in liver and muscle and thus enhance insulin sensitivity. Great interest in the AMPK system was generated in 2001, when it was reported that AMPK was activated in intact cells and in vivo by the anti-diabetic drug metformin (187). Metformin is the front-line drug for treatment of type 2 diabetes, and is currently prescribed to >100 million people worldwide. It does not directly activate AMPK or promote Thr172 phosphorylation in cell-free assays, and seems to work instead indirectly by inhibiting Complex I of the respiratory chain (32; 131), thus increasing cellular ADP:ATP and AMP:ATP ratios. The clearest evidence for this comes from the use of human cells expressing AMPK with either wild type γ2 or an R531G mutant, a mutant form that is completely resistant to activation by AMP and ADP. Metformin fails to activate the R531G mutant, confirming that it activates AMPK indirectly by increasing cellular AMP and/or ADP (54). Interestingly, another class of drug used to treat Type 2 diabetes, the thiazolidinediones, also appear to activate AMPK indirectly by inhibiting Complex I of the respiratory chain (10) and increasing AMP and ADP (54). These are therefore examples of drugs that activate AMPK by acting as metabolic poisons. Despite this rather crude mechanism of action, metformin has been used clinically for over 50 years and is a safe drug. Being positively charged, once inside the cell it accumulates in mitochondria due to the membrane potential across the mitochondrial inner membrane. It has been pointed out that if inhibition of the respiratory chain caused a significant collapse of this membrane potential, metformin would no longer accumulate in mitochondria, so that it would exert a self-limiting effect (131). Interestingly, the related biguanide phenformin, which (being more hydrophobic) enters cells more rapidly and is a more potent AMPK activator than metformin (54), was withdrawn for treatment of diabetes due to rare but life-threatening cases of lactic acidosis; this is a complication that might be expected for an inhibitor of the respiratory chain.

There is still some controversy about the extent to which the therapeutic benefits of metformin are mediated by AMPK. Given that it activates AMPK indirectly by inhibiting mitochondrial function, it is perhaps not surprising that the drug should have other targets. Its major site of action appears to be the liver, partly because hepatocytes are exposed via the portal circulation to high concentrations of metformin absorbed from the gut, and partly because they express high levels of OCT1, an organic cation transporter required for rapid uptake of metformin, but not phenformin, into cells (168). One of the major therapeutic effects of metformin in Type 2 diabetes is to inhibit hepatic glucose production. Surprisingly, in knockout mice lacking both AMPK catalytic subunits (α1 and α2) in the liver, hepatic glucose production and its acute inhibition by metformin, and the expression of gluconeogenic enzymes, all appear to be relatively unaffected (35). It now seems likely that these acute effects of metformin on the liver are mediated by other AMP-inhibited enzymes including the gluconeogenic enzyme fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (167) and adenylate cyclase, the enzyme that synthesizes cyclic AMP (115). Inhibition of the former would explain acute inhibition of gluconeogenesis by metformin, while inhibition of the latter might explain some effects of the drug on gluconeogenic enzyme expression, which is enhanced by cyclic AMP produced in response to glucagon.

While these results show that metformin can acutely depress hepatic glucose production in the absence of AMPK, they do not rule out the possibility that AMPK plays a role when it is present. Another major effect of metformin is to enhance insulin sensitivity, and this is where its ability to activate AMPK may be critical. The classical targets of AMPK include the two isoforms of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, ACC1 and ACC2, which are inactivated by phosphorylation at the equivalent sites, Ser79 and Ser212 (mouse numbering). ACC1 was previously thought to produce the pool of malonyl-CoA used in fatty acid synthesis, and ACC2 the pool that inhibits carnitine-palmitoyl transferase-1 and thus fatty acid oxidation, although these two pools may not be as distinct as previously thought (38). Inactivation of ACC1 and ACC2 by AMPK therefore inhibits fatty acid synthesis and promotes fatty acid oxidation. Consistent with this, hepatocytes from double knock-in (ACC1-S79A/ACC2-S212A) mice, in which neither isoform can be regulated by AMPK, had elevated levels of malonyl-CoA, high rates of fat synthesis, and low rates of fat oxidation. On a standard diet the knock-in mice had elevated contents of di- and tri-glycerides in liver and skeletal muscle, high plasma glucose and insulin, and were glucose-intolerant and insulin-resistant. On a high-fat diet the differences in these metabolic parameters between the knock-in and wild type mice were eliminated, suggesting that increased fat consumption over-rides the differences caused by the inability of AMPK to inactivate ACC1/ACC2 in the former. As expected, chronic metformin treatment of the wild type mice fed a high-fat diet reduced hepatic lipogenesis and di- and triglyceride content, lowered fasting blood glucose, improved glucose tolerance, and increased suppression of hepatic glucose production by insulin. Intriguingly, however, these effects were all absent in the double knock-in mice (38). These results suggest that the chronic effects of metformin to enhance insulin sensitivity in the liver, and thus to promote suppression of gluconeogenesis by insulin, are mediated primarily by the phosphorylation of ACC1 and ACC2 by AMPK.

Interestingly, metformin and phenformin are both biguanide derivatives of guanidine. Guanidine and its isoprenyl derivative galegine occur naturally in the plant Galega officinalis, which was used as a herbal medicine in the middle ages. Phenformin (50) and galegine (120) are more potent activators of AMPK than metformin, and being more hydrophobic are able to enter rapidly even into cells lacking organic cation transporters. All three compounds act indirectly by inhibiting mitochondrial function and increasing cellular AMP:ATP and ADP:ATP ratios (54).

Another natural plant product that activates AMPK is salicylate (52). The traditional source of salicylate is the bark of the willow Salix alba (hence the name), and the use of willow extracts as a medicine is described in documents dating from around the third millennium BCE, making it perhaps the oldest medicine known to mankind. However, salicylate is probably produced by all plants and is now known to be a hormone released by cells undergoing pathogen infection, which signals to uninfected tissues to mount a defense response (157).

Salicylate is generally present in plants as derivatives such as salicin (salicyl β-glucoside), which was used to treat rheumatic fever in Scotland in the 19th century (107). Pharmaceutical chemists have synthesized other salicylate derivatives that are used clinically today, such as aspirin (acetyl salicylate) and salsalate, the latter a diester of salicylate. Aspirin is, of course, one of the most widely used and successful drugs of all time, used prophylactically in patients at risk of thrombosis, for relief of pain and fever, and for its anti-inflammatory effects. In the 1970s it was discovered that aspirin inhibited the synthesis of prostaglandins (165), shown later to be due to transfer of the acetyl group of aspirin to active site residues in the cyclo-oxygenase enzymes (COX1 and COX2) that catalyze the first reaction in the pathway (141). Acetylation irreversibly inactivates COX1 in platelets, preventing synthesis of the pro-thrombotic prostanoid thromboxane A2 and thus reducing the tendency of platelets to trigger blood clotting. Since platelets cannot resynthesize COX1, this inhibition lasts for their lifetime of ten days, providing an elegant explanation for the potent antithrombotic effects of aspirin (166). However, it remains unclear whether all of the other effects of aspirin are mediated by inhibition of cyclo-oxygenases. Both aspirin and salsalate are rapidly broken down to salicylate following their adsorption from the gut; following an oral dose of aspirin in rats, its half-life in the circulation is a few minutes compared with several hours for the salicylate derived from it, and the peak plasma concentrations of salicylate are 50-fold higher than aspirin (56). While the anti-inflammatory effects of aspirin have been widely assumed to be due to inhibition of COX2 (whose expression is induced at sites of infection and inflammation), not all findings support that idea. For example, due to lack of an acetyl group salicylate is a poor inhibitor of cyclo-oxygenases compared with aspirin (165), yet appears to be just as effective at suppressing inflammation (135). Salicylate is also effective at suppressing inflammation even in mice that lack COX2 (25).

There are also several reports of effects of salicylate-based drugs on lipid metabolism, which cannot easily be explained by inhibition of cyclo-oxygenases. These metabolic effects can be much more readily explained by recent findings that salicylate, at concentrations around 1 mM that are reached in plasma of humans taking high doses of aspirin or salsalate, activates AMPK in intact cells (52). Activation is caused by direct binding of salicylate (but not aspirin) to a site on the β1 subunit of AMPK, which appears to overlap with the binding site for A-769662, a synthetic AMPK activator derived from a high-throughput screen (175). Salicylate is a rather poor allosteric activator compared with A-769662, but both compounds also enhance Thr172 phosphorylation by inhibiting its dephosphorylation. Both compounds failed to activate AMPK complexes containing the β2 rather than the β1 isoform (52), and since β2 knockout mice were available this provided an opportunity to test whether effects of either drug were mediated by AMPK activation in vivo. When wild type mice were injected with salicylate or A-769662, AMPK was activated in the liver and ACC1 and ACC2 became phosphorylated, as expected. This was associated with a more rapid decrease in respiratory exchange ratio when food was withdrawn, indicating a more rapid switch from carbohydrate to fat oxidation on fasting; both drugs also lowered free fatty acids in serum. However, all of these effects were ablated in the β1 knockout mice, strongly suggesting that the effects on lipid metabolism were mediated by AMPK activation (52).

Could AMPK activation also be responsible for some of the anti-inflammatory effects of salicylate-based drugs? This idea, for which conclusive evidence is not yet available, is considered in more detail in other reviews (127; 155). However, it has already been shown that other AMPK-activating drugs oppose dendritic cell activation (a trigger for inflammation) by the bacterial product lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (88), and oppose conversion of macrophages to the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype by LPS and fatty acids (71; 144; 180). The β1 subunit is the predominant AMPK-β isoform in macrophages, and markers associated with inflammation were increased in macrophages from β1 knockout mice. Activation of AMPK with A-769662 also increased fatty acid oxidation and reduced inflammatory markers in wild type but not β1-deficient macrophages, while the effects of A-769662 to suppress inflammation were impaired if fatty acid oxidation was blocked [43]. These results suggest that salicylate might exert anti-inflammatory effects via AMPK, and that effects of AMPK on cellular metabolism may be crucial in limiting inflammatory responses.

Activation of AMPK by “nutraceuticals” or natural products from traditional herbal medicines

Galegine and salicylate are examples of a growing list of natural products, mainly derived from plants, which have been reported within the last five years to activate AMPK in intact mammalian cells. A list of over 50 of these is given in Table 3. Some of these compounds, such as resveratrol found in red wine, epigallocatechin gallate from green tea and ginsenosides from Panax ginseng are being promoted as “nutraceuticals”, while many others are derived from herbs used in traditional Asian medicines. Although some can be classed as polyphenols, their structures are very varied, and one puzzle has been how so many compounds of such varying structure could all activate AMPK, a molecule with a limited number of binding sites for small molecules. Clues came with findings that some of these compounds (such as arctigenin (62)) are inhibitors of Complex I of the respiratory chain, while others (such as resveratrol (54)) are inhibitors of the mitochondrial F1 ATP synthase. While this has not yet been tested for the vast majority of these natural products, it seems likely that mitochondria will be the direct target of many of them. The mitochondrial respiratory chain and F1 ATP synthase contain several membrane-bound complexes with very large numbers of hydrophobic subunits, and it seems likely that many xenobiotic compounds would find bindings sites within these complexes that would interfere with their function. Most of the compounds are secondary metabolites of plants, and some may be produced as defensive measures to deter infection by pathogens and/or grazing by insect or mammalian herbivores (for example, resveratrol is produced by grapes in response to fungal infection (140)). They are often stored by plant cells in the vacuole or cell wall (8; 152), where they would not inhibit the function of their own mitochondria. It seems likely that synthesis of mitochondrial poisons might be a useful general mechanism for plants to defend themselves against pathogens and herbivores, while at the same time providing a rich source of pharmacologically active agents for humans.

Table 3.

Partial list of natural products (mostly from plants) that have been reported to activate AMPK in intact cells or in vivo. Although a single source species is usually listed, most of the compounds are probably also produced by related species.

| Natural product | Source | Mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| arctigenin | Arctium lappa | inhibits Complex I | (61; 156) |

| berberine | Berberis spp., other plants | inhibits Complex I | (54; 99) |

| galegine | Galega officinalis | inhibits Complex I | (120) |

| quercetin | many plants | inhibits Complex I | (54) |

| resveratrol | grapes, red wine | inhibits F1 ATPase | (6; 54) |

| salicylate | Salix alba (willow), other plants | binds to AMPK β subunit | (52) |

| 2-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-5-(E)-propenylbenzofuran | Krameria lappacea | ? | (92) |

| 2-methyl-7-hydroxymethyl-1,4-naphthoquinone | Pyrola rotundifolia | ? | (136) |

| alternol | Alternaria alternata | ? | (182) |

| anthocyanin fraction | Purple sweet potato | ? | (65) |

| apigenin | Matricaria chamomilla | ? | (130; 160) |

| aspalathin | Aspalathus linearis | ? | (153) |

| caffeic acid | white grapes, coffee, other plants | ? | (101; 163) |

| celastrol | many plants | ? | (84) |

| chrysin | Passiflora caerulea | ? | (150) |

| cucurbitane triterpenoids | Siraitia grosvenorii | ? | (19) |

| curcumin | Curcuma longa | ? | |

| emodin | Rheum emodi | ? | (21; 164) |

| epigallocatechin gallate | Camellia sinensis | ? | (17) |

| ethanol extract | Vitis thunbergii | ? | (132) |

| ethanol extract | Malva verticillata | ? | (72) |

| fargesin | Magnolia spp. | ? | (98) |

| foenumoside B | Lysimachia foenum-graecum | ? | (149) |

| geraniol | rose/palmarosa/citronella oils | ? | (86) |

| GGEx18 (traditional Korean medicine) | Laminaria japonica/Rheum palmatum/Ephedra sinica | ? | (151) |

| ginsenosides | Panax ginseng | ? | (80; 139; 184) |

| glabridin | Glycyrrhiza glabra | ? | (94) |

| green tea extract | Camellia sinensis | ? | (5; 60) |

| hispidulin | Saussurea involucrate | ? | (103; 178) |

| honokiol | Magnolia grandiflora | ? | (76) |

| Jinqi formula | Coptidis rhizome/Astragali rhadix/Lonicerae japonicae | ? | (138) |

| Karanjin | Pongamia pinnata | ? | (69) |

| lindenenyl acetate | Lindera strychnifolia | ? | (70) |

| mangiferin | Iris unguicularis | ? | (125) |

| methyl cinnamate | Zanthoxylum armatum | ? | (20) |

| naringin | Citrus x paradisi | ? | (137) |

| octaphlorethol A | Ishige foliacea (a brown alga) | ? | (96) |

| osthole | Cnidium monnieri | ? | (97) |

| plant extract | Scutellaria baicalensis | ? | (154) |

| plant extract | Boesenbergia pandurata | ? | (81) |

| pomolic acid | Chrysobalanus icaco | ? | (183) |

| pterostilbene | grapes, other fruits | ? | (102) |

| ReishiMax | Ganoderma lucidum | ? | (159) |

| Rhizochalin (aglycone) | Rhizochalina incrustata (a sponge) | ? | (79) |

| S-methylmethionine sulfonium chloride | many plants | ? | (95) |

| salidroside | Rhodiola rosea | ? | (104) |

| tangeretin | Citrus tangerine (tangerine) | ? | (85) |

| tanshinone IIA | Salvia miltiorrhiza | ? | (64) |

| tiliroside | rose hips, strawberry, raspberry | ? | (41) |

| ursolic acid | Mirabilis jalapa, other plants | ? | (186) |

| xanthigen | Punica granatum | ? | (93) |

Conclusions

AMPK is the central component of a signaling pathway that appears to have arisen very early during eukaryotic evolution. Its ancestral role appears to have been in the response to glucose starvation, and it may also have evolved to monitor the output of mitochondria and regulate their replication. The ortholog in budding yeast appears to be regulated primarily by ADP, but in animals the kinase has evolved to respond primarily to AMP instead, and has acquired an additional mechanism (allosteric activation) that makes it even more sensitive to energy stress. By activating alternate catabolic pathways and inhibiting ATP-consuming processes, AMPK acts in a cell-autonomous manner to maintain energy homeostasis. In mammals, AMPK in specialized neurons in the hypothalamus also responds to hormones that regulate energy intake and expenditure at the whole body level. AMPK is activated by two of the most widely used clinical drugs (metformin and aspirin), and also by many natural products, mainly produced by plants, which are derived from traditional herbal medicines or are being promoted as “nutraceuticals”.

Acknowledgements

Recent studies in the DGH laboratory have been supported by a Senior Investigator Award from the Wellcome Trust, and a Programme Grant from Cancer Research-UK.

Acronyms and Definitions

- ACC1/2

acetyl-CoA carboxylase-1, -2

- AgRP

agouti-related protein

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- CaMKKβ

calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase, β isoform

- CBS repeat

sequence motif present in cystathionine β-synthase and other proteins, usually occurring as tandem repeats

- Diauxic shift

the biphasic growth curve obtained when yeast are grown in batch culture on glucose

- Fermentation

production of ethanol from glucose in yeast via glycolysis

- Glucose repression

repression of transcription of genes by glucose in micro-organisms

- HMG-CoA

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA

- Mitophagy

specialized form of autophagy via which dysfunctional mitochondria are degraded

- mTORC1

mechanistic target-of-rapamycin complex-1

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- PI

phosphoinositide

- PI3P

phosphoinositide 3-phosphate

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- POMC

pro-opiomelanocortin

- Puetz-Jeghers syndrome

a hereditary cancer susceptibility syndrome caused by mutations in LKB1

- RyR

ryanodine receptor

- S6KI

ribosomal protein S6 kinase-I

- Secondary metabolites

organic compounds that are not directly involved in the normal growth, development, or reproduction of an organism

- Snf1

sucrose non-fermenting-1

- T3

tri-iodothyronine

- Warburg effect

the switch to rapid glycolysis that occurs when mammalian cells are growing rapidly

Literature Cited

- 1.Akman HO, Sampayo JN, Ross FA, Scott JW, Wilson G, et al. Fatal infantile cardiac glycogenosis with phosphorylase kinase deficiency and a mutation in the gamma-2 subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:499–504. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181462b86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amodeo GA, Rudolph MJ, Tong L. Crystal structure of the heterotrimer core of Saccharomyces cerevisiae AMPK homologue SNF1. Nature. 2007;449:492–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson KA, Ribar TJ, Lin F, Noeldner PK, Green MF, et al. Hypothalamic CaMKK2 contributes to the regulation of energy balance. Cell Metab. 2008;7:377–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apfeld J, O'Connor G, McDonagh T, Distefano PS, Curtis R. The AMP-activated protein kinase AAK-2 links energy levels and insulin-like signals to lifespan in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3004–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.1255404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee S, Ghoshal S, Porter TD. Phosphorylation of hepatic AMP-activated protein kinase and liver kinase B1 is increased after a single oral dose of green tea extract to mice. Nutr Res. 2012;32:985–90. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, Jamieson HA, Lerin C, et al. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature. 2006;444:337–42. doi: 10.1038/nature05354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beg ZH, Allmann DW, Gibson DM. Modulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme: A reductase activity with cAMP and with protein fractions of rat liver cytosol. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1973;54:1362–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)91137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braidot E, Zancani M, Petrussa E, Peresson C, Bertolini A, et al. Transport and accumulation of flavonoids in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Plant Signal Behav. 2008;3:626–32. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.9.6686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browne GJ, Finn SG, Proud CG. Stimulation of the AMP-activated protein kinase leads to activation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase and to its phosphorylation at a novel site, serine 398. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12220–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunmair B, Staniek K, Gras F, Scharf N, Althaym A, et al. Thiazolidinediones, like metformin, Inhibit respiratory complex I: a common mechanism contributing to their antidiabetic actions? Diabetes. 2004;53:1052–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bultot L, Guigas B, Von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff A, Maisin L, Vertommen D, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylates and inactivates liver glycogen synthase. Biochem J. 2012;443:193–203. doi: 10.1042/BJ20112026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burwinkel B, Scott JW, Buhrer C, van Landeghem FK, Cox GF, et al. Fatal congenital heart glycogenosis caused by a recurrent activating R531Q mutation in the g2 subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase (PRKAG2), not by phosphorylase kinase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:1034–49. doi: 10.1086/430840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD(+) metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:1056–60. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carling D, Mayer FV, Sanders MJ, Gamblin SJ. AMP-activated protein kinase: nature's energy sensor. Nature Chem Biol. 2011;7:512–8. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carling D, Zammit VA, Hardie DG. A common bicyclic protein kinase cascade inactivates the regulatory enzymes of fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 1987;223:217–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson CA, Kim KH. Regulation of hepatic acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:378–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen D, Pamu S, Cui Q, Chan TH, Dou QP. Novel epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) analogs activate AMP-activated protein kinase pathway and target cancer stem cells. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:3031–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Wang J, Zhang YY, Yan SF, Neumann D, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase undergoes nucleotide-dependent conformational changes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:716–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen XB, Zhuang JJ, Liu JH, Lei M, Ma L, et al. Potential AMPK activators of cucurbitane triterpenoids from Siraitia grosvenorii Swingle. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:5776–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen YY, Lee MH, Hsu CC, Wei CL, Tsai YC. Methyl cinnamate inhibits adipocyte differentiation via activation of the CaMKK2-AMPK pathway in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:955–63. doi: 10.1021/jf203981x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Z, Zhang L, Yi J, Yang Z, Zhang Z, Li Z. Promotion of adiponectin multimerization by emodin, a novel AMPK activator with PPARgamma-agonist activity. J Cell biochem. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jcb.24232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Claret M, Smith MA, Batterham RL, Selman C, Choudhury AI, et al. AMPK is essential for energy homeostasis regulation and glucose sensing by POMC and AgRP neurons. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2325–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI31516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corton JM, Gillespie JG, Hawley SA, Hardie DG. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleoside: a specific method for activating AMP-activated protein kinase in intact cells? Eur J Biochem. 1995;229:558–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coven DL, Hu X, Cong L, Bergeron R, Shulman GI, et al. Physiologic role of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in the heart: graded activation during exercise. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:E629–E36. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00171.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cronstein BN, Montesinos MC, Weissmann G. Salicylates and sulfasalazine, but not glucocorticoids, inhibit leukocyte accumulation by an adenosine-dependent mechanism that is independent of inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis and p105 of NFkappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6377–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dagon Y, Hur E, Zheng B, Wellenstein K, Cantley LC, Kahn BB. p70S6 Kinase phosphorylates AMPK on serine 491 to mediate leptin's effect on food intake. Cell Metab. 2012;16:104–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daval M, Diot-Dupuy F, Bazin R, Hainault I, Viollet B, et al. Anti-lipolytic action of AMP-activated protein kinase in rodent adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25250–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies SP, Hawley SA, Woods A, Carling D, Haystead TAJ, Hardie DG. Purification of the AMP-activated protein kinase on ATP-γ-Sepharose and analysis of its subunit structure. Eur J Biochem. 1994;223:351–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies SP, Helps NR, Cohen PTW, Hardie DG. 5'-AMP inhibits dephosphorylation, as well as promoting phosphorylation, of the AMP-activated protein kinase. Studies using bacterially expressed human protein phosphatase-2Cα and native bovine protein phosphatase-2Ac. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:421–5. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies SP, Sim AT, Hardie DG. Location and function of three sites phosphorylated on rat acetyl-CoA carboxylase by the AMP-activated protein kinase. Eur J Biochem. 1990;187:183–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331:456–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Mir MY, Nogueira V, Fontaine E, Averet N, Rigoulet M, Leverve X. Dimethylbiguanide inhibits cell respiration via an indirect effect targeted on the respiratory chain complex I. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:223–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erion DM, Shulman GI. Diacylglycerol-mediated insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2010;16:400–2. doi: 10.1038/nm0410-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fogarty S, Hawley SA, Green KA, Saner N, Mustard KJ, Hardie DG. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta activates AMPK without forming a stable complex - synergistic effects of Ca2+ and AMP. Biochem J. 2010;426:109–18. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foretz M, Hebrard S, Leclerc J, Zarrinpashneh E, Soty M, et al. Metformin inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis in mice independently of the LKB1/AMPK pathway via a decrease in hepatic energy state. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2355–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI40671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395:763–70. doi: 10.1038/27376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fryer LG, Foufelle F, Barnes K, Baldwin SA, Woods A, Carling D. Characterization of the role of the AMP-activated protein kinase in the stimulation of glucose transport in skeletal muscle cells. Biochem J. 2002;363:167–74. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fullerton MD, Galic S, Marcinko K, Sikkema S, Pulinilkunnil T, et al. Single phosphorylation sites in ACC1 and ACC2 regulate lipid homeostasis and the insulin-sensitizing effects of metformin. Nat Med. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nm.3372. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garton AJ, Campbell DG, Carling D, Hardie DG, Colbran RJ, Yeaman SJ. Phosphorylation of bovine hormone-sensitive lipase by the AMP-activated protein kinase. A possible antilipolytic mechanism. Eur J Biochem. 1989;179:249–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillespie JG, Hardie DG. Phosphorylation and inactivation of HMG-CoA reductase at the AMP-activated protein kinase site in response to fructose treatment of isolated rat hepatocytes. FEBS Lett. 1992;306:59–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goto T, Teraminami A, Lee JY, Ohyama K, Funakoshi K, et al. Tiliroside, a glycosidic flavonoid, ameliorates obesity-induced metabolic disorders via activation of adiponectin signaling followed by enhancement of fatty acid oxidation in liver and skeletal muscle in obese-diabetic mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23:768–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gowans GJ, Hawley SA, Ross FA, Hardie DG. AMP is a true physiological regulator of AMP-activated protein kinase by both allosteric activation and enhancing net phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2013;18:556–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greer EL, Brunet A. Different dietary restriction regimens extend lifespan by both independent and overlapping genetic pathways in C. elegans. Aging Cell. 2009;8:113–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Habets DD, Coumans WA, El Hasnaoui M, Zarrinpashneh E, Bertrand L, et al. Crucial role for LKB1 to AMPKalpha2 axis in the regulation of CD36-mediated long-chain fatty acid uptake into cardiomyocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:212–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hardie DG. AMPK: a target for drugs and natural products with effects on both diabetes and cancer. Diabetes. 2013;62:2164–72. doi: 10.2337/db13-0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hardie DG, Carling D, Carlson M. The AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinase subfamily: metabolic sensors of the eukaryotic cell? Ann Rev Biochem. 1998;67:821–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hardie DG, Hawley SA. AMP-activated protein kinase: the energy charge hypothesis revisited. BioEssays. 2001;23:1112–9. doi: 10.1002/bies.10009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haurie V, Boucherie H, Sagliocco F. The Snf1 protein kinase controls the induction of genes of the iron uptake pathway at the diauxic shift in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45391–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hawley SA, Boudeau J, Reid JL, Mustard KJ, Udd L, et al. Complexes between the LKB1 tumor suppressor, STRADα/β and MO25α/β are upstream kinases in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. J Biol. 2003;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hawley SA, Davison M, Woods A, Davies SP, Beri RK, et al. Characterization of the AMP-activated protein kinase kinase from rat liver, and identification of threonine-172 as the major site at which it phosphorylates and activates AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27879–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hawley SA, Fullerton MD, Ross FA, Schertzer JD, Chevtzoff C, et al. The ancient drug salicylate directly activates AMP-activated protein kinase. Science. 2012;336:918–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1215327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hawley SA, Pan DA, Mustard KJ, Ross L, Bain J, et al. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta is an alternative upstream kinase for AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Metab. 2005;2:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hawley SA, Ross FA, Chevtzoff C, Green KA, Evans A, et al. Use of cells expressing gamma subunit variants to identify diverse mechanisms of AMPK activation. Cell Metab. 2010;11:554–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hawley SA, Ross FA, Gowans GJ, Tibarewal P, Leslie NR, Hardie DG. Phosphorylation by Akt within the ST loop of AMPK-α1 down-regulates its activation in tumour cells. Biochem J. 2014 doi: 10.1042/BJ20131344. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Higgs GA, Salmon JA, Henderson B, Vane JR. Pharmacokinetics of aspirin and salicylate in relation to inhibition of arachidonate cyclooxygenase and antiinflammatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1417–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holmes BF, Kurth-Kraczek EJ, Winder WW. Chronic activation of 5'-AMP-activated protein kinase increases GLUT-4, hexokinase, and glycogen in muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1990–5. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.5.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hoppe S, Bierhoff H, Cado I, Weber A, Tiebe M, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase adapts rRNA synthesis to cellular energy supply. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17781–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909873106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Horman S, Vertommen D, Heath R, Neumann D, Mouton V, et al. Insulin antagonizes ischemia-induced Thr172 phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase alpha-subunits in heart via hierarchical phosphorylation of Ser485/491. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5335–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506850200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang HC, Lin JK. Pu-erh tea, green tea, and black tea suppresses hyperlipidemia, hyperleptinemia and fatty acid synthase through activating AMPK in rats fed a high-fructose diet. Food Funct. 2011 doi: 10.1039/c1fo10157a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang SL, Yu RT, Gong J, Feng Y, Dai YL, et al. Arctigenin, a natural compound, activates AMP-activated protein kinase via inhibition of mitochondria complex I and ameliorates metabolic disorders in ob/ob mice. Diabetologia. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang SL, Yu RT, Gong J, Feng Y, Dai YL, et al. Arctigenin, a natural compound, activates AMP-activated protein kinase via inhibition of mitochondria complex I and ameliorates metabolic disorders in ob/ob mice. Diabetologia. 2012;55:1469–81. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hurley RL, Anderson KA, Franzone JM, Kemp BE, Means AR, Witters LA. The Ca2+/calmoldulin-dependent protein kinase kinases are AMP-activated protein kinase kinases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29060–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hwang SL, Yang JH, Jeong YT, Kim YD, Li X, et al. Tanshinone IIA improves endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced insulin resistance through AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2013;430:1246–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hwang YP, Choi JH, Han EH, Kim HG, Wee JH, et al. Purple sweet potato anthocyanins attenuate hepatic lipid accumulation through activating adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase in human HepG2 cells and obese mice. Nutr Res. 2011;31:896–906. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ingebritsen TS, Lee H, Parker RA, Gibson DM. Reversible modulation of the activities of both liver microsomal hydroxymethylglutaryl Coenzyme A reductase and its inactivating enzyme. Evidence for regulation by phosphorylation-dephosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1978;81:1268–77. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jager S, Handschin C, St-Pierre J, Spiegelman BM. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1{alpha} Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12017–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jaiswal N, Yadav PP, Maurya R, Srivastava AK, Tamrakar AK. Karanjin from Pongamia pinnata induces GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle cells in a phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase-independent manner. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;670:22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jeong GS, Lee DS, Li B, Kim JJ, Kim EC, Kim YC. Anti-inflammatory effects of lindenenyl acetate via heme oxygenase-1 and AMPK in human periodontal ligament cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;670:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jeong HW, Hsu KC, Lee JW, Ham M, Huh JY, et al. Berberine suppresses proinflammatory responses through AMPK activation in macrophages. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E955–E64. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90599.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jeong YT, Song CH. Antidiabetic activities of extract from Malva verticillata seed via the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;21:921–9. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1104.04015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jorgensen SB, Nielsen JN, Birk JB, Olsen GS, Viollet B, et al. The α2-5'AMP-activated protein kinase is a site 2 glycogen synthase kinase in skeletal muscle and is responsive to glucose loading. Diabetes. 2004;53:3074–81. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jorgensen SB, Viollet B, Andreelli F, Frosig C, Birk JB, et al. Knockout of the alpha2 but not alpha1 5'-AMP-activated protein kinase isoform abolishes 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-4-ribofuranoside but not contraction-induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1070–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:439–51. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kapoor S. Attenuation of tumor growth by honokiol: an evolving role in oncology. Drug Discov Therapeutics. 2012;6:327–8. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2012.v6.6.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Katinka MD, Duprat S, Cornillot E, Metenier G, Thomarat F, et al. Genome sequence and gene compaction of the eukaryote parasite Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Nature. 2001;414:450–3. doi: 10.1038/35106579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kelley DE, Goodpaster BH, Storlien L. Muscle triglyceride and insulin resistance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:325–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.010402.102912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Khanal P, Kang BS, Yun HJ, Cho HG, Makarieva TN, Choi HS. Aglycon of rhizochalin from the Rhizochalina incrustata induces apoptosis via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in HT-29 colon cancer cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:1553–8. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim do Y, Park YG, Quan HY, Kim SJ, Jung MS, Chung SH. Ginsenoside Rd stimulates the differentiation and mineralization of osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells by activating AMP-activated protein kinase via the BMP-2 signaling pathway. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:215–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim DY, Kim MS, Sa BK, Kim MB, Hwang JK. Boesenbergia pandurata attenuates diet-Induced obesity by activating AMP-activated protein kinase and regulating lipid metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:994–1005. doi: 10.3390/ijms13010994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim J, Kim YC, Fang C, Russell RC, Kim JH, et al. Differential regulation of distinct Vps34 complexes by AMPK in nutrient stress and autophagy. Cell. 2013;152:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–41. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim JH, Lee JO, Lee SK, Kim N, You GY, et al. Celastrol suppresses breast cancer MCF-7 cell viability via the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-induced p53-polo like kinase 2 (PLK-2) pathway. Cellular Signalling. 2013;25:805–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim MS, Hur HJ, Kwon DY, Hwang JT. Tangeretin stimulates glucose uptake via regulation of AMPK signaling pathways in C2C12 myotubes and improves glucose tolerance in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;358:127–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim SH, Park EJ, Lee CR, Chun JN, Cho NH, et al. Geraniol induces cooperative interaction of apoptosis and autophagy to elicit cell death in PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:1683–90. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koo SH, Flechner L, Qi L, Zhang X, Screaton RA, et al. The CREB coactivator TORC2 is a key regulator of fasting glucose metabolism. Nature. 2005;437:1109–14. doi: 10.1038/nature03967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Krawczyk CM, Holowka T, Sun J, Blagih J, Amiel E, et al. Toll-like receptor-induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood. 2010;115:4742–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kubota N, Yano W, Kubota T, Yamauchi T, Itoh S, et al. Adiponectin stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase in the hypothalamus and increases food intake. Cell Metab. 2007;6:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kudo N, Barr AJ, Barr RL, Desai S, Lopaschuk GD. High rates of fatty acid oxidation during reperfusion of ischemic hearts are associated with a decrease in malonyl-CoA levels due to an increase in 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17513–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kurth-Kraczek EJ, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ, Winder WW. 5' AMP-activated protein kinase activation causes GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 1999;48:1667–71. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.8.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ladurner A, Atanasov AG, Heiss EH, Baumgartner L, Schwaiger S, et al. 2-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-5-(E)-propenylbenzofuran promotes endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity in human endothelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;84:804–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lai CS, Tsai ML, Badmaev V, Jimenez M, Ho CT, Pan MH. Xanthigen suppresses preadipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis through down-regulation of PPARgamma and C/EBPs and modulation of SIRT-1, AMPK, and FoxO pathways. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:1094–101. doi: 10.1021/jf204862d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]