Abstract

Introduction

The Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI) was developed by the American Psychiatric Association for clinical screening of hypersexual disorder (HD).

Aims

To examine the distribution of the proposed diagnostic entity HD according to the HDSI in a sample of men and women seeking help for problematic hypersexuality and evaluate some psychometric properties.

Methods

Data on sociodemographics, the HDSI, the Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS), and the Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes of Sexual Behavior were collected online from 16 women and 64 men who self-identified as hypersexual. Respondents were recruited by advertisements offering psychological treatment for hypersexual behavior.

Main Outcome Measures

The HDSI, covering the proposed criteria for HD.

Results

Of the entire sample, 50% fulfilled the criteria for HD. Compared with men, women scored higher on the HDSI, engaged more often in risky sexual behavior, and worried more about physical injuries and pain. Men primarily used pornography, whereas women had sexual encounters. The HD group reported a larger number of sexual specifiers, higher scores on the SCS, more negative effects of sexual behavior, and more concerns about consequences compared with the non-HD group. Sociodemographics had no influence on HD. The HDSI’s core diagnostic criteria showed high internal reliability for men (α = 0.80) and women (α = 0.81). A moderate correlation between the HDSI and the SCS was found (0.51). The vast majority of the entire sample (76 of 80, 95%) fulfilled the criteria for sexual compulsivity according to the SCS.

Conclusion

The HDSI could be used as a screening tool for HD, although further explorations of the empirical implications regarding criteria are needed, as are refinements of cutoff scores and specific sexual behaviors. Hypersexual problematic behavior causes distress and impairment and, although not included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, HD should be endorsed as a diagnosis to develop evidence-based treatment and future studies on its etiology.

Öberg KG, Hallberg J, Kaldo V, et al. Hypersexual Disorder According to the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory in Help-Seeking Swedish Men and Women With Self-Identified Hypersexual Behavior. Sex Med 2017;5:e229–e236.

Key Words: Hypersexual Disorder, Sexual Compulsivity, Screening Inventory, Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory, Gender

Introduction

Hypersexual behavior often manifests clinically. Although hypersexual disorder (HD)1 was not included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), a diagnosis is needed to recognize help-seeking persons with excessive and “out-of-control” sexual behavior. Non-paraphilic hypersexual behavior is not a new phenomenon2, 3, 4 and has been found in as many as 12% of men and 7% of women.5 Adverse consequences are well documented6, 7, 8, 9; in severe cases, sexual preoccupation has been shown to be a predictor of recidivism in sexual offending4, 10 and pornography consumption has been linked to attitudes supporting violence against women.11

Research on HD, especially in women, is at an early stage and knowledge about its origin, features, and development is limited; validated measurements and treatments are lacking. Various estimates and types of hypersexual behavior have been presented. For example, the predominant behavior in help seekers was pornography use (81%),9 whereas 80% of highly sexually active gay men reported sex with consenting adults.12 In the nosology dispute, different aspects of the construct have been stressed and, in consequence, different measurements13, 14, 15, 16 have been used to capture the condition. In this study, the measurement to define HD (Figure 1) was taken from the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) proposal1, 17 because it applies the atheoretical term hypersexuality and grades increased intensity of sexual behavior along a continuum.18 These HD criteria have been validated in a clinical population9 and the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI), with high internal reliability, has been suggested as a useful assessment tool.12, 19

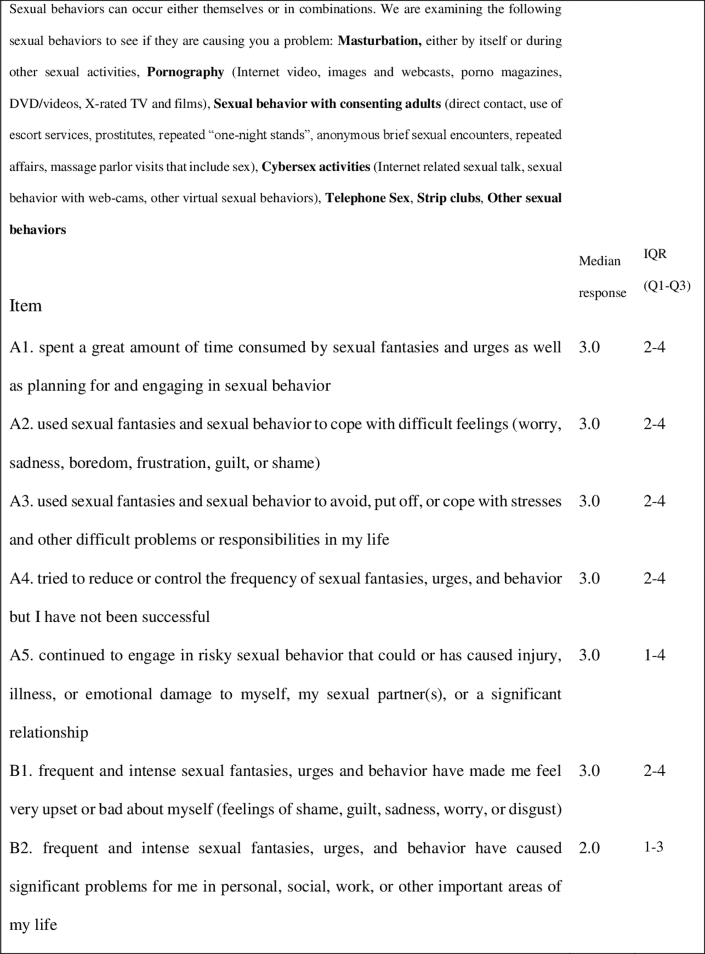

Figure 1.

Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory phrasing of five statements addressing hypersexual disorder and two statements addressing distress and impairment during the past 6 months uniformly followed by the alternatives “never true,” “rarely true,” “sometimes true,” “often true,” and “almost always true.” Section C consists of various sexual behaviors and a seventh open-ended question on different sexual specifiers that can be answered yes or no. The median response and IQR for each item are provided (N = 80). IQR = interquartile range; Q1 = quartile 1; Q3 = quartile 3.

The literature on women with non-paraphilic hypersexuality is even scarcer than such literature on men. Studies investigating both women and men have reported 5% to 22% to be women9, 20, 21, 22 and an estimate of “sexually addicted” to be as many as 40% to 50% of the total population.23 The forms of sexual behavior differ from men by women having fewer sexual partners and being more relationally motivated.24, 25 An online survey found that frequent masturbation, pornography use, and number of sexual partners were associated with hypersexual behavior in women.26 Hypersexuality in men has been associated with decreased sexual satisfaction and physical health,5 whereas women experience psychological and social distress.8

Ambiguous conceptualizations and concerns about labeling sexual practices as pathologic emphasize the importance of a uniform definition, clear operational criteria, and sound clinical measures for the classification of HD.

Aims

The overall purpose of the present study was to describe the distribution of HD according to the HDSI in a sample of help-seeking individuals with self-identified hypersexual behavior. Specific aims were to (i) describe the distribution of HD and the specified sexual behaviors, (ii) analyze the relation with adverse consequences and sociodemographic characteristics and examine sex differences, and (iii) explore the internal consistency of the HDSI and correlates with a validated instrument, the Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS).

Methods

This study is based on data from a clinical trial evaluating a cognitive behavioral therapy program for HD.

Procedure

Data collection was performed through a website from April 25 to August 20, 2010. Information on ethical guidelines, the HD condition, and the principles for cognitive behavioral therapy was presented at the website. After giving and signing informed consent, respondents logged onto a secure platform with 14 web-administered questionnaires, which took approximately 45 minutes to complete.

Participants

Participants were recruited through advertisements and articles in the media addressing persons who self-identified with excessive and “out-of-control” sexual behavior and who were interested in participating in a cognitive behavioral treatment program. Inclusion criteria for participation in the web-administered questionnaires included age of at least 18 years, disclosing contact and identification information, and a signed informed consent. Eighty individuals signed an informed consent, met the inclusion criteria, and completed the screening.

Measures

Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory

The HDSI (Figure 1) was designed to screen for HD according to the APA’s proposed DSM-5 criteria.1, 17 5 core diagnostic items cover the A criteria of hypersexual behavior and 2 B items cover distress and impairment. A five-grade scale (0–4), ranging from “never true” to “almost always true” during the past 6 months, is applied. The median response and interquartile range (IQR) for each item are provided in Figure 1. 6 different “sexual specifiers” are examined on a yes-vs-no scale. For a probable diagnosis of HD, a score of 3 or 4 is required on 4 of 5 A criteria and on 1 B criterion. Total scores range from 0 to 28, and the minimum score to meet the probable diagnosis of HD gathered from at least 4 A criteria and 1 B criterion is 1517 (note: the website is no longer active). The choice of threshold for HD was based on clinical experience and consensus in the APA’s Paraphilia Subworkgroup to minimize the rate of false-positive diagnosis.1, 17 According to Parsons et al,12 the HDSI fits a single-factor solution and shows strong reliability across the continuum of hypersexuality. However, 2 items, A2 and A3, can measure sex as form of coping. An additional clinically relevant unidimensional cutoff score of 20 points was suggested.12 A possible diagnosis of HD according to the HDSI is referred to in this report as “HD” or “clinical” and below cutoff as “non-HD” or “subclinical.” A backward-to-forward translation was performed by an authorized translator.

Sexual Compulsivity Scale

The SCS was chosen as a theoretically similar measure for validation of the HDSI.27 It consists of 10 items (Swedish version, 9 items) where respondents rate their agreement with statements related to sexually compulsive behavior, preoccupations, and intrusive thoughts on four-point scales ranging from 1 (“not at all like me”) to 4 (“very much like me”). Respondents are considered sexually compulsive if their average score (total score divided by the number of items) exceeds 2.1, which in previous studies was at least at the 80th percentile.13, 28 The scale can be further classified by severity, with a total sum score lower than 18 indicating “not sexually compulsive,” a score of 18 to 23 indicating “mild,” a score of 24 to 29 indicating “moderate,” and a score higher than 30 indicating “severe.”29 The scale was reliable in a sample of HIV-positive men and women (α = 0.89 and α = 0.92, respectively)14 and in the present sample (α = 0.79).

Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes of Sexual Behavior Scale

The Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes of Sexual Behavior Scale (CBOSB) includes 36 questions divided into 2 subscales: concerns regarding possible consequences and actual consequences of sexual behavior within financial, legal, work-related, psychological, and social areas. The health area consists of physical injury and pain, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted disease.8 The total scale yielded an α value equal to 0.86 in the present sample.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 15.0 and 19.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and R “stats” 2.15.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Spearman rank correlations were performed for item-item and item-total calculations. Differences between groups were tested with the Mann-Whitney U-test and Wilcoxon rank sum test and for dichotomous data cross-tabulation with χ2 and Fisher exact tests as appropriate. Results were defined as statistically significant at a P value less than .05. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to find correlations between items in HDSI subscale AB (ordinal data), and item-to-total correlation was calculated using the Spearman coefficient and removing the item’s contribution to the sum.

Ethics

The study was approved by the regional ethical review board in Stockholm (2010/204-31/5).

Results

Distributions of HD and Sexual Specifiers According to the HDSI

50% (n = 40) of the entire sample (30 men [47%] and 10 women [62%]) fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for HD. Total median score for the entire sample was 20 (IQR = 20–23) and for HD respondents the median score was significantly (P < .000) higher than for the non-HD group (Table 1). Most (81%) had a sum score within the predefined HD diagnostic interval (15–28 points), although 39% did not fulfill the requirement of a minimum score of 3 points on at least 4 of 5 A criteria and 3 or 4 points on at least 1 B criterion. Applying the quantitative cutoff score of 2012 showed no significant difference compared with the original cutoff17; distributions between women and men were similar, with a higher prevalence of HD among women (75%, n = 12) compared with men (45%, n = 29).

Table 1.

Total scores of Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory A and B criteria and frequencies of sexual specifiers in women and men with self-identified hypersexual behavior on a probable diagnosis of HD and non-diagnosis (N = 80)

| HD |

Non-HD |

Total (N = 80) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n = 10) | Men (n = 30) | Total (n = 40) | Women (n = 6) | Men (n = 34) | Total (n = 40) | ||

| Total scores, min–max; median (IQR) | |||||||

| A + B criteria | 20–27; 25 (23–27) | 15–28; 22 (20–24) | 15–28; 23 (21–25) | 10–20; 18 (14–20) | 3–23; 16 (10–19) | 3–23; 16 (10–19) | 3–28; 20 (16–23) |

| A criteria | 14–20; 18 (16–19) | 12–20; 16 (15–17) | 12–20; 16.5 (15–18) | 7–16; 13 (11–15) | 3–18; 11 (8–14) | 3–18; 12 (8–14) | 3–20; 14.5 (12–17) |

| B criteria | 5–8; 7 (6–8) | 3–8; 5 (5–7) | 3–8; 6 (5–7) | 3–8; 4 (3–7) | 0–8; 4 (2–5) | 0–8; 4 (2–6) | 0–8; 5 (4–6) |

| C—sexual specifiers, n (%) | |||||||

| Masturbation | 5 (50) | 21 (70) | 26 (65) | 3 (50) | 23 (68) | 26 (65) | 52 (65) |

| Pornography | 5 (50) | 29 (97) | 34 (85) | 3 (50) | 24 (71) | 27 (68) | 61 (76) |

| Sex with consenting adults | 9 (90) | 12 (40) | 21 (53) | 5 (83) | 11 (32) | 16 (40) | 37 (46) |

| Cybersex | 6 (60) | 15 (50) | 21 (53) | 4 (67) | 11 (32) | 15 (38) | 36 (45) |

| Telephone sex | 6 (60) | 8 (27) | 14 (35) | 1 (17) | 4 (12) | 5 (13) | 19 (24) |

| Strip clubs | 3 (30) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) | 3 (8) | 6 (8) |

| Other sexual behavior | 4 (40) | 8 (27) | 12 (30) | 2 (33) | 8 (24) | 10 (25) | 22 (28) |

HD = hypersexual disorder; IQR = interquartile range (quartiles 1–3); max = maximum; min = minimum.

Women had a significantly (P = .012) higher total sum score (median = 23) than men (median = 19) and significantly (P < .001) more frequent risky sexual behavior. Total sum score for women in the HD group was significantly higher (P = .014) compared with men with HD.

Pornography use was the most reported specifier, followed by masturbation and sex with consenting adults. Masturbation and pornography use were reported in combination by 60%, whereas 30% engaged in sexual activity with consenting adults combined with cybersex. Although pornography use was predominant in men (82%), women most often reported sexual activity with consenting adults (88%).

A significantly (P = .018) larger number of specifiers was found in the HD group (median = 3.0, IQR = 2–4) compared with the non-HD group (median = 2, IQR = 2–4).

Adverse Consequences

When comparing the HD and non-HD groups on the CBOSB, the former scored significantly higher than the latter on the concerns and actual consequences of sexual behavior subscales (P < .001, P < .021). Further, the HD group was more concerned about social (P < .01), psychological (P < .01), and legal- and work-related consequences (P < .05) than the non-HD group. Women reported more actual consequences (P < .003) and worried more for pregnancies and sexually transmitted disease (P < .01) and physical injuries and pain (P < .01) than men.

Sociodemographics

Sociodemographic characteristics and significant sex differences are presented in Table 2. None of the sociodemographic items were significantly related to the criteria for HD.

Table 2.

Distribution of sociodemographic characteristics in women and men with self-identified hypersexual behavior (N = 80)

| Sociodemographics | Women (n = 16; 20%) | Men (n = 64; 80%) | Total (N = 80) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y), range; mean (SD)∗ | 19–49; 29.4 (9.8) | 24–66; 40.7 (9.7) | 19–66; 38.4 (10.6) |

| Educational level, n (%) | |||

| University experience | 7 (44) | 42 (66) | 49 (61) |

| Upper secondary school | 8 (50) | 20 (31) | 28 (35) |

| Compulsory education | 1 (6) | 2 (3) | 3 (4) |

| Vocationally active, n (%)∗ | 4 (25) | 46 (72) | 50 (63) |

| Partner, n (%)∗ | 4 (25) | 44 (69) | 48 (60) |

| Children, n (%) | 5 (31) | 30 (47) | 35 (44) |

P < .05.

Internal Reliability

The HDSI core diagnostic inventory was internally consistent with an α coefficient of 0.81 (women, α = 0.81; men, α = 0.80). Item-to-total correlations (Table 3) ranged from 0.39 to 0.69 (lowest for stress). Three combinations of responses (A.5 and A.2, A.5 and A.3, and B.2 and A.3) were not significantly correlated, whereas most item combinations demonstrated significant, moderate associations. In men, most intercorrelations (25 of 28) and all item-to-total correlations were significant. In women, the strengths of the correlations were as high as those for men, but the small number resulted in fewer significant correlations.

Table 3.

Intercorrelations, item to item and item to total, for the HDSI∗

| Scale item | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | B1 | B2 | HDSI total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1. Time, women/men | — | 0.53†/0.58† | 0.44†/0.35† | 0.62†/0.40† | 0.63†/0.45† | 0.61†/0.49† | 0.43/0.39† | 0.85†/0.78† |

| A2. Dysphoric feelings, women/men | 0.60† | — | 0.58†/0.63† | 0.50†/0.36† | 0.40/0.06 | 0.30/0.49† | 0.09/0.34† | 0.52†/0.71† |

| A3. Stress, women/men | 0.38† | 0.62† | — | 0.05/0.28† | 0.10/−0.08 | 0.18/0.39† | −0.31/0.29† | 0.02/0.55† |

| A4. Control, women/men | 0.43† | 0.38† | 0.22† | — | 0.50†/0.26† | 0.47/0.55† | 0.34/0.23 | 0.62†/0.57† |

| A5. Risk taking, women/men | 0.47† | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.27† | — | 0.73†/0.32† | 0.46/0.36† | 0.67†/0.57† |

| B1. Distress, women/men | 0.52† | 0.47† | 0.37† | 0.52† | 0.41† | — | 0.0.37/0.39† | 0.66†/0.72† |

| B2. Impairment, women/men | 0.41† | 0.33† | 0.21 | 0.26† | 0.40† | 0.41† | — | 0.34/0.66† |

| HDSI total | 0.69† | 0.57† | 39† | 0.45† | 0.40† | 0.63† | 0.49† |

HDSI = Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory.

Upper diagonal presents values for women (n = 16) and men (n = 64); lower diagonal presents values for total sample (N = 80).

P < .05.

Comparisons Between the HDSI and the SCS

Correlations and cross-tabulation were used to challenge the concurrent validity of the HDSI with the SCS. The vast majority of the entire sample (76 of 80, 95%) fulfilled the criteria for sexual compulsivity under the SCS according to Kalichman and Rompa.13 The probability that the HDSI would diagnose somebody also diagnosed by the SCS cutoff was 53% (40/[40 + 36] = 0.53). A moderate positive correlation of 0.51 was found (P < .01; women, r = 0.66, P < .01; men, r = 0.51, P < .01), supporting a moderate concurrent validity. The distributions of categories of severity of sexual compulsivity (according to the SCS) were significantly different between the HD and non-HD groups (Table 4). Further, HD respondents scored significantly higher (P < .001) on the SCS than the non-HD group. No sex differences were found to be significant on the SCS.

Table 4.

Distribution of respondents with and without HD according to the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory at classification of level of severity on the SCS (N = 80)

| SCS∗ | HD (n = 40), n (%) | Non-HD (n = 40), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No | 0 (0) | 3 (8) |

| Mild | 6 (15) | 9 (23) |

| Moderate | 10 (25) | 18 (45) |

| Severe | 24 (60) | 10 (25) |

HD = hypersexual disorder; SCS = Sexual Compulsivity Scale.

P < .001.

Discussion

The key observation in this study was that only 50% of help-seeking persons with self-identified hypersexuality fulfilled the criteria for HD according to the HDSI screening instrument. In addition, a striking sex difference was noted: women had significantly higher scores on the HDSI and different hypersexual behaviors with more pronounced negative consequences, although these results must be considered preliminary because of the small sample. The HDSI’s core diagnostic criteria had high internal reliability and positive correlations with a measure of compulsive sexual behavior indicating concurrent validity of the HDSI.

Using the polythetic and alternative quantitative cutoff, the rate of 50% HD in this help-seeking sample seems rather low, especially because 95% were considered sexually compulsive. In consequence, the suggested requirements of at least 4 A criteria and 1 B criterion,1, 17 or a minimum of 20 points,12 for the endorsement of the HD diagnosis seems rather strict. However, these classification proposals of the disorder are arbitrary and adjustments of the number of diagnostic criteria and the cutoff for the total score for categorization as HD might be needed. A designation of severity as mild, moderate, or severe instead of a blunt binary cutoff for diagnosis is encouraged. A “moderate” condition conceivably causes distress and could motivate treatment. This is supported by the finding that as many as 70% of individual with subclinical HD reported moderate or severe sexual compulsive behavior and overall high scores on the HDSI. Conversely, differences in the number of types of sexual behavior and the degree of negative outcomes that we found between clinical and subclinical statuses give some support to the proposed cutoff.

When applying the Parson cutoff method, our sample was divided with a minor difference into HD vs non-HD groups and the distribution between women and men remained. 7 individuals were added to the HD group and 6 were removed (reclassified). Limited by the small number, we do not know whether systematic differences between these individuals exist. However, the different methods had no influence on sensitivity or specificity12 and the quantitative cutoff corresponded almost perfectly to the original proposal.1, 17 The quantitative cutoff of the HDSI, somewhat simpler to administrate, seems preferable in clinical settings.

Our findings suggest that HD is composed of excessive time consumption, increased sexual behavior in response to dysphoric feelings, and loss of control, as proposed.1, 24, 30 Risk-taking behavior in combination with “dysphoric feelings and stress” demonstrated low correlations in the entire group, possibly explained by differences in mediators or drive for sexual behavior, that is, dysphoric emotions, on the one hand, and sexual drive or sensation seeking, on the other. The weak association between hypersexual behaviors in response to stress, especially for women, suggests that the criterion does not contribute to an HD diagnosis. As stated by the Paraphilia Subworkgroup on the rationale for the proposed criteria,17 “stress and stressful events are not affects” but have been associated in referenced scales with sexual behavior. As phrased in the HSDI, “stresses” might be interpreted by the respondent as “being heavily occupied” or “being emotionally overloaded.” However, it has been concluded that all proposed HD criteria demonstrate high reliability and validity when applied in a clinical setting.9 As suggested previously,12 the items of stress and dysphoric feelings measure sex as a form of coping and the scale to assess HD also includes “coping mechanisms to manage distress by sexual outlet.” The high item-to-item correlation between A2 and A3 found in this study emphasizes the interrelation and the suggested “coping mechanism.”

The present study does not include an independent clinical assessment for HD, thus weakening analyses of the sensitivity and specificity of the HDSI. A preliminary analysis of the diagnostic validity found a modest likelihood that the HDSI would suggest a positive diagnosis compared with the SCS, in agreement with previous findings.27 Although overlapping with the HDSI, the SCS incorporates preoccupation, loss of control, and adverse consequences but fails to include sex as a coping strategy for dysphoric feelings and stress.

The finding that higher levels of hypersexuality led to aggravation9 is in accordance with the differences found regarding negative consequences between the clinical and subclinical groups. When classified into a “moderate” group (sum score = 15–20, 30% of sample), we found no significant differences in negative consequences compared with 18% of the total sample that had “no disorder” (sum score = 0–14). Furthermore, the larger number of sexual specifiers in the HD group compared with the non-HD group could reflect an increased risk for HD with a broader sexual repertoire.

In contrast to Parsons et al12 but in agreement with Reid et al,9 we found that pornography was the most prevalent hypersexual behavior in men. Considering the selection criteria of at least nine sexual partners in the past 90 days, the finding of 80% reporting “sex with consenting adults” is hardly surprising.12 In the present study most men lived in a relationship and half of them had children, whereas in the study by Parsons et al,12 79% were single. It is worth noting that the women in this study had a similar partner status to the men in the study by Parsons et al12 and reported a similar pattern of distribution for the specified types of sexual behavior. By engaging predominantly in sexual acts with others, women were evidently exposed to greater risk taking with adverse effects such as physical injury and pain in addition to pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease. One could argue that at least in middle-age men with a relatively socio-demographically stable situation, a reason to seek treatment is impairment from extensive and out-of-control pornography use. In contrast, women seek help when sexually active with multiple partners. A tentative explanation for this could be the greater stigma for women with many sexual partners.

Although men with HD constituted the vast majority of those presenting to the clinic, in our experience the number of women is increasing. The proportion of women (20%) is similar to previous findings.21, 22 The importance of recognizing this disorder in women should be emphasized; moreover, diversity in subtypes of sexual behavior could lead clinicians to more properly address HD interventions in men and women, especially because excessively sexually active women could experience increased social stigma and be less likely to express the need for treatment despite pronounced distress from risky sexual behavior. A possible flaw of the screening inventory with regard to women’s sexual behavior needs recognition. The specifiers include “prostitutes” but not “prostitution” and “use of escorts” but not “offering escort services.” As discussed previously,23 instruments identifying “sexual addiction” in men might not do so in women, and it seems evident that the HDSI terminology needs refinement. Note that the differences between women and men could be explained by sample selection bias, with women being significantly younger and having a lower education status, a less stable partner, and lower vocational status compared with men. As suggested previously,31 lower socioeconomic “individuals tend to over-report sexual addiction.”

Limitations

The main limitation of the present study is the small sample, particularly for women, and the risk for selection bias owing to the self-selected help-seeking sample. As stated previously, these results are preliminary and must be interpreted with caution. The reliance on self-reported data collected solely over the internet in a convenience sample makes it difficult to determine whether reported distress is of clinical significance and whether hypersexual behavior is better explained within the context of another Axis I disorder. The classification of HD vs non-HD in this report is tentative and based solely on self-reported data, and a clinical interview is needed for the diagnostic assessment to differentiate between subclinical conditions and a disorder. It is important to bear in mind the possible bias in these responses and to emphasize that the contribution of this study, with a total sample of 80, is a “proof of concept” with regard to the development of the HDSI.

Additional psychometric investigations of the HDSI, such as test-retest reliability, item response theory, receiver operating characteristic curve analyses, and correlation analyses with other related measures, are necessary, as are reference data on sexually active women and men who do not seek help.

Conclusion

The results indicate that the criteria for HD, as previously proposed and measured by the HDSI, have an acceptable reliability, although further specification of severity as mild, moderate, or severe and refinement regarding specific behaviors and acknowledging sex differences seem reasonable. In line with several previous studies, we suggest that problematic sexual behavior affects men and women and causes pain and suffering. Although not included in the DSM-5, the clinical and scientific communities could endorse the “diagnosis” of HD because of its atheoretical integrative model of “excessive and out-of-control sexual behavior” in addition to future work on its etiology and development of evidence-based treatment.

Statement of authorship

Category 1

-

(a)Conception and Design

- Katarina Görts Öberg; Jonas Hallberg; Viktor Kaldo; Cecilia Dhejne; Stefan Arver

-

(b)Acquisition of Data

- Katarina Görts Öberg; Jonas Hallberg

-

(c)Analysis and Interpretation of Data

- Katarina Görts Öberg; Jonas Hallberg; Viktor Kaldo; Cecilia Dhejne; Stefan Arver

Category 2

-

(a)Drafting the Article

- Katarina Görts Öberg; Jonas Hallberg

-

(b)Revising It for Intellectual Content

- Katarina Görts Öberg; Jonas Hallberg; Viktor Kaldo; Cecilia Dhejne; Stefan Arver

Category 3

-

(a)Final Approval of the Completed Article

- Katarina Görts Öberg; Jonas Hallberg; Viktor Kaldo; Cecilia Dhejne; Stefan Arver

Acknowledgment

The authors kindly acknowledge the support of the Swedish Prison and Probation Administration R&D. We also acknowledge Tania Samuelsson for the linguistic revision.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding: Swedish Prison and Probation System Service (grant: 2010-159, Dnr 52-2010-013228).

References

- 1.Kafka M.P. Hypersexual disorder: a proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39:377–400. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carnes P. CompCare; Minneapolis, MN: 1983. Out of the shadows: understanding sexual addiction. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman E. Sexual compulsivity: definition, etiology, and treatment considerations. J Chem Depend Treat. 1987;1:189–204. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kingston D.A., Firestone P. Problematic hypersexuality: a review of conceptualization and diagnosis. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2008;15:284–310. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langstrom N., Hanson R.K. High rates of sexual behavior in the general population: correlates and predictors. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35:37–52. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-8993-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper A., Golden G.H., Kent-Ferraro J. Online sexual behavior in the workplace: how can human resource departments and employee assistance programs responds effectively? Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2002;9:149–165. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalichman S.C., Cain D. The relationship between indicators of sexual compulsivity and high risk sexual practices among men and women receiving services from a sexual transmitted infection clinic. J Sex Res. 2004;41:235–241. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBride K.R., Reece M., Sanders S.A. Using the Sexual Compulsivity Scale to predict outcomes of sexual behavior in young adults. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2008;15:97–115. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid R.C., Carpenter B.N., Hook J.N. Report of findings in a DSM-5 field trial for hypersexual disorder. J Sex Med. 2012;9:2868–2877. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanson R.K., Morton-Bourgon K.E. The characteristics of persistent sexual offenders: a meta-analysis of recidivism studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:1154–1163. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hald G.M., Malamuth N.M., Yuen C. Pornography and attitudes supporting violence against women: revisiting the relationship in nonexperimental studies. Aggress Behav. 2010;36:14–20. doi: 10.1002/ab.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parsons J.T., Rendina J.H., Ventuanec A. A psychometric investigation of the hypersexual disorder screening inventory among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men: an item response theory analysis. J Sex Med. 2013;10:3088–3101. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalichman S.C., Rompa D. Sexual sensation seeking and sexual compulsivity scales: validity, and predicting HIV risk behavior. J Pers Assess. 1995;65:586–601. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalichman S.C., Rompa D. The Sexual Compulsivity Scale: further development and use with HIV-positive persons. J Pers Assess. 2001;76:379–395. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7603_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carnes P., Green B., Carnes S. The same yet different: refocusing the Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST) to reflect orientation and gender. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2010;17:7–30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janssen E., Vorst H., Finn P. The Sexual Inhibition (SIS) and Sexual Excitation (SES) Scales: II. Predicting psychophysiological response pattens. J Sex Res. 2002;39:127–132. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory. American Psychiatric Association's DSM-5 workgroup on sexual and gender identity disorders. http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=415 Available at: Published 2010. Accessed September 2011.

- 18.Walters G.D., Knight R.A., Langstrom N. Is hypersexuality dimensional? Evidence for the DSM-5 from general population and clinical samples. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40:1309–1321. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9719-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Womack S.D., Hook J.N., Ramos M. Measuring hypersexual behavior. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2013;20:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raymond N.C., Coleman E., Miner M.H. Psychiatric comorbidity and compulsive/impulsive traits in compulsive sexual behavior. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44:370–380. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00110-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briken P., Habermann N., Berner W. Diagnosis and treatment of sexual addiction: a survey among German sex therapists. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2007;14:131–143. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Black D.W., Kehrberg L.L.D., Flumerfelt D.L. Characteristics of 36 subjects reporting compulsive sexual behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:243–249. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferree M.C. Females and sex addiction: myths and diagnostic implications. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2001;8:287–300. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black D.W., Kehrberg L., Flumerfelt D.L. Characteristics of 36 subjects reporting compulsive sexual behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:243–249. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner M. Female sexual compulsivity: a new syndrome. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31:713–727. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein V., Rettenberger M., Briken P. Self-reported indicators of hypersexuality and its correlates in a female online sample. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1974–1981. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ventuneac A., Rendina J., Grov C. An item response theory analysis of the Sexual Compulsivity Scale and its correspondence with the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory among a sample of highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. J Sex Med. 2015;12:481–493. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalichman S.C., Rompa D. The Sexual Compulsivity Scale: further development and use with HIV-positive persons. J Pers Assess. 2001;76:379–395. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7603_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan M.S., Krueger R.B. Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of hypersexuality. J Sex Res. 2010;47:181–198. doi: 10.1080/00224491003592863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bancroft J., Vukadinovic Z. Sexual addiction, sexual compulsivity, sexual impulsivity, or what? Toward a theoretical model. J Sex Res. 2004;41:225–234. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marshall L.E., Marshall W.L., Moulden H.M. CEU eligible article. The prevalence of sexual addiction in incarcerated sexual offenders and matched community nonoffenders. Sex Addict Compulsivity. 2008;15:271–283. [Google Scholar]