Abstract

Purpose

Longer survival for children with sarcoma has led to the recognition of chronic health conditions related to prior therapy. We sought to study the association of sarcoma therapy with the development of scoliosis.

Methods

We reviewed patient demographics, treatment exposures, and functional outcomes for patients surviving > 10 years after treatment for sarcoma between 1964–2002 at our institution. The diagnosis of scoliosis was determined by imaging. Functional performance and standardized questionnaires were completed in a long-term follow-up clinic.

Results

We identified 367 patients, with median age at follow-up of 33.1 years. Scoliosis was identified in 100 (27.2%) patients. Chest radiation [relative risk (RR): 1.88 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.21–2.92, p < 0.005,)] and rib resection [RR: 2.64 (CI: 1.79–3.89), p < 0.0001] were associated with an increased incidence of scoliosis; thoracotomy without rib resection was not. Of 21 patients who underwent rib resection, 16 (80.8%) had the apex of scoliosis towards the surgical side. Scoliosis was associated with worse pulmonary function [RR: 1.74 (CI: 1.14–2.66, p < 0.01] and self-reported health outcomes, including functional impairment [RR: 1.60 (CI: 1.07–2.38), p < 0.05] and cancer-related pain [RR: 1.55 (CI: 1.11–2.16), p < 0.01]. Interestingly, pulmonary function was not associated with performance on the six minute walk test in this young population.

Conclusions

Children with sarcoma are at-risk of developing scoliosis when treatment regimens include chest radiation or rib resection. Identification of these risk factors may allow for early intervention designed to prevent adverse long-term outcomes.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Cancer survivors at risk of developing scoliosis may benefit from monitoring of pulmonary status and early physical therapy.

Keywords: Scoliosis, Sarcoma, Thoracotomy, Survivors, Rib resection

INTRODUCTION

Over the past several decades, outcomes among children diagnosed with sarcoma have improved such that 75% of children will survive at least five years [1]. Unfortunately, improved longevity is not without consequences, as survivors frequently experience chronic health conditions related to their prior cancer and its treatment. For survivors of childhood sarcoma, chemotherapy exposures, radiation therapy, and surgical procedures (tumor resection, laminectomy, chest wall resection, etc.) are associated with musculoskeletal late effects, including scoliosis [2–6]. The long-term predictors of developing scoliosis after treatment for childhood sarcomas have not been previously described.

Spinal curvature in children impacts pulmonary function and exercise capacity [4–6]. Among childhood sarcoma survivors, this condition may contribute to an already compromised respiratory system as certain anticancer therapies in childhood are associated with long-term pulmonary toxicity [7, 8]. Furthermore, children treated for sarcoma are at risk for bone mineral density deficits, which may predispose them to spinal deformity [9]. While research indicates a higher incidence of scoliosis in children who underwent chest wall resection [10], the long-term impact of this impairment on pulmonary function and exercise capacity has not been well studied.

Thus, the aim of this analysis was two-fold. First, we sought to identify treatment-related predictors of developing scoliosis in long-term survivors of childhood sarcoma. Second, we compared pulmonary function and exercise capacity among those with and without scoliosis. These data are designed to provide information on children at high risk for long-term pulmonary dysfunction so that clinicians can identify candidates for whom early preventive measures could be instituted.

METHODS

Participants for this analysis included 367 survivors of osteosarcoma (OS), Ewing sarcoma family of tumors (ESFT), rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS), and non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcoma (NRSTS) who were members of the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). Details of the study protocol and procedures have been described previously [11, 12]. Briefly, this study includes childhood cancer survivors treated from 1964 to 2002 at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital for a pediatric malignancy who are at least 10 years from cancer diagnosis and who are 18 years of age or older. Participants complete a series of questionnaires, undergo clinical evaluations based on risks predisposed by previous cancer treatment (risk based medical screening), a core battery of laboratory tests, and a standardized functional assessment. For these analyses, patients with musculoskeletal disorders prior to cancer diagnosis were excluded.

Data extracted by medical record review included cancer-related information (histology, age at diagnosis, chemotherapy including cumulative doses, and radiation exposures including region-specific dosimetry), surgical interventions to the chest (e.g. thoracotomy, thoracoscopy, or rib resection) and/or limbs (e.g. amputations or limb-sparing procedures). Additional demographic data (race, sex, and age) were obtained from questionnaires. Anthropometric information (height and weight), body mass index (BMI), and cardiac ejection fraction from echocardiography for those exposed to chest radiation and/or anthracycline chemotherapy were obtained as part of the SJLIFE clinical evaluation. Obesity was defined as a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 [13].

Diagnostic imaging studies of all patients were individually reviewed by the study radiologist (SCK), and the Cobb angle determined if a scoliosis series (n=38, 10.3%) had been performed. If no scoliosis series was available, then the scoliosis was graded as yes or no based on available imaging studies performed for disease surveillance that included the spine [dual-energy absorptiometry (n=292, 79.6%), x-ray (n=27, 7.4%), computed tomography (n=7, 1.9%), magnetic resonance (n=2, 0.5%), or positron emission tomography (n=1, 0.3%)]. The designation of clinically significant scoliosis was defined as a Cobb angle ≥ 15o [14]. The direction (left vs. right) of the apex of the spinal curvature was also recorded.

As part of clinical evaluation, participants with pulmonary toxic exposures (chest radiation, thoracotomy, busulfan, carmustine, lomustine, and bleomycin) were evaluated with pre-bronchodilator spirometry to determine forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) [15]. For analyses, participants were assigned a pulmonary chronic condition grade based on a modified version of the Common Terminology for Adverse Events, version 4.01: 0) FVC and FEV1 ≥80% of predicted; 1) FVC 75–79% or FEV1 70–79% of predicted; 2) FVC 50–74% or FEV1 60–69% of predicted; 3) FVC < 50% or FEV1 50–59% of predicted; and 4) FEV1 < 50% of predicted [16].

Overall fitness was determined by having participants complete the American Thoracic Society guideline-based six-minute walk test [17]. Briefly, participants were asked to walk as far as possible in six minutes on a level indoor surface without jogging or running. Encouragement was given every two minutes. Participants were allowed to stop and rest during the test if necessary. Stopping did not stop the clock. Heart rate (HR) was monitored at rest and continuously; rate of perceived exertion was ascertained at rest, 2, 4 and 6 minutes and 2 minutes after test completion. Distance in meters and physiological cost index (PCI) in beats per meter (maximum HR minus resting HR divided by distance) were used for analysis [18].

Adverse health status outcomes were categorized based on previously published definitions [19]. Participants who answered “poor” or “fair” to the following question: “Would you say that your health is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor?” were considered to have ‘poor general health’. Participants who had sex-specific T-score of 63 or higher on Global Severity Index or subscales of the Brief Symptom Inventory (anxiety, depression, and somatization) were considered to have ‘poor mental health’. Patients who reported limitations in moderate activities for more than three months of the past two years were deemed to have ‘activity limitations’. Participants who reported the need of assistance with personal activities of daily living, routine needs, or difficulty attending school or work were deemed to have ‘functional impairments’. Cancer-related anxiety was also rated as medium, a lot or very many, and extreme fears/anxiety.

Demographic characteristics, treatment variables, and outcomes were compared between survivors with and without scoliosis with t-tests and Chi-square statistics as appropriate. Multi-variable generalized linear regression with Poisson distribution and robust error estimates were used to identify predictors of scoliosis and to evaluate associations between scoliosis and outcomes, including pulmonary function and adverse health status outcomes and less than optimal social role attainment outcomes (all binomial outcomes) [20, 21]. General linear regression was used to evaluate associations between scoliosis, pulmonary function, and performance on the six-minute walk test (both distance walked and PCI). Independent variables and potential confounders of the associations between independent and dependent variable were determined for evaluation a priori and entered simultaneously into models. All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.3.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

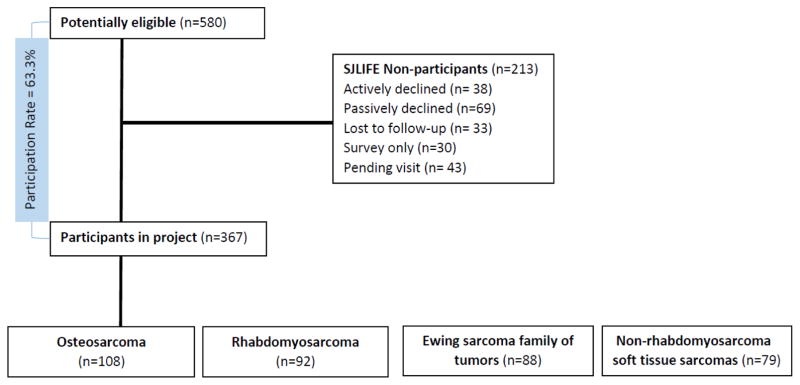

Among the 580 sarcoma survivors potentially eligible for these analyses, 107 actively or passively declined participation, 33 were lost to follow-up, 30 elected to complete a survey only, and 43 agreed to participate but were pending scheduling, resulting in complete data for 367 (63.3%) who underwent clinical assessments between November 1, 2007 and June 30, 2014 (Figure 1). Participants did not differ from non-participants by sex, age at diagnosis or age at evaluation, cyclophosphamide use, but were slightly less likely to be white (80.9% versus 87.3%, p=0.047), and more likely to have received anthracyclines (72.2% vs. 60.1%, p=0.003). The primary histology distribution was: OS (29.4%), RMS (25.1%), ESFT (24.0%), and NRSTS (21.5%). The majority (54.8%) of patients were male.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patients.

The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1 by scoliosis status. Nearly one quarter (N=100, 27.2%) of the cohort had scoliosis diagnosed by the last imaging available performed either specifically to evaluate scoliosis or for disease surveillance. Median age at diagnosis was 11.8 (range: 0.0–24.8) years. Most participants (80.9%) were Caucasian, while 17.4% were African-American. Median age at last follow-up was 33.1 (range: 19.3–63.8) years. Because our cohort includes patients treated as long ago as 40 years when amputation was more common, 97 (26.4%) patients underwent amputation for their disease, while a lower proportion (35; 9.5%) had limb-salvage procedures. Six (6.2%) of these patients had upper extremity amputations, of which three developed scoliosis. Forty-six (12.5%) survivors underwent a total of 58 thoracotomies. Forty (87.0%) had one and three (6.5%) survivors had two thoracotomies. The remaining three patients underwent three, four, and five thoracotomies, respectively. No ribs were removed during any thoracotomy. An additional seven (1.9%) patients underwent minimally invasive thoracoscopic procedures. Twenty-six (7.1%) patients underwent chest wall resections involving resection of at least one rib. More than one tenth (11.7%) of patients received radiation to the chest. Patients received a variety of chemotherapeutic agents for their diagnosis including anthracyclines (72.2%), cyclophosphamide (62.1%), dactinomycin (49.3%), bleomycin (4.1%), and carmustine (2.2%). No patients received busulfan or lomustine, two potentially pulmonary toxic chemotherapeutic agents. Among all participants, 9.6% had a cardiac ejection fraction < 50%, and 31.6% were obese.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| All (N=367) | No scoliosis (N=267) | Scoliosis (N=100) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 11.2 ± 5.3 | 11.4 ± 5.2 | 10.7 ± 5.5 | 0.22 |

| Median (Range) | 11.8 (0.0, 24.8) | 12.3 (0.1, 24.8) | 11.0 (0.0, 23.5) | |

| Age at follow-up (years) | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 34.0 ± 8.9 | 34.6 ± 8.6 | 32.4 ± 9.7 | 0.044 |

| Median (Range) | 33.1 (19.3, 63.8) | 33.8 (19.3, 63.8) | 30.3 (19.4, 61.5) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | P | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 166 (45.2) | 116 (43.4) | 50 (50.0) | 0.26 |

| Male | 201 (54.8) | 151 (56.6) | 50 (50.0) | |

| Raceγ | ||||

| Caucasian | 297 (80.9) | 212 (79.4) | 85 (85.0) | 0.22 |

| African-American | 64 (17.4) | 49 (18.4) | 15 (15.0) | |

| Other | 6 (1.6) | 6 (2.2) | 0 | |

| Surgical chest intervention α | < 0.0001 | |||

| None | 291 (79.3) | 226 (84.6) | 65 (65.0) | |

| Thoracoscopy | 7 (1.9) | 4 (1.5) | 3 (3.0) | |

| Thoracotomy | 43 (11.7) | 32 (12.0) | 11 (11.0) | |

| Rib resection | 26 (7.1) | 5 (1.9) | 21 (21.0) | |

| Amputation status | 0.27 | |||

| None | 235 (64.0) | 168 (62.9) | 67 (67.0) | |

| Limb-salvage only | 35 (9.5) | 23 (8.6) | 12 (12.0) | |

| Amputation | 97 (26.4) | 76 (28.5) | 21(21.0) | |

| Chest radiation | 43 (11.7) | 17 (6.4) | 26 (26.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Anthracyclines | 265 (72.2) | 186 (69.7) | 79 (79.0) | 0.075 |

| < 300 mg/m2 | 75 (20.5) | 52 (19.5) | 23 (23.2) | |

| ≥300 mg/m2 | 189 (51.6) | 134 (50.2) | 55 (55.6) | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 228 (62.1) | 171 (64.0) | 57 (57.0) | 0.22 |

| <6000 mg/m2 | 42 (11.4) | 35 (13.1) | 7 (7.0) | |

| ≥6000 mg/m2 | 186 (50.7) | 136 (50.9) | 50 (50.0) | |

| Dactinomycin | 181 (49.3) | 135 (50.6) | 46 (46.0) | 0.44 |

| Bleomycin | 15 (4.1) | 14 (5.2) | 1 (1.0) | 0.079 β |

| Carmustine | 8 (2.2) | 5 (1.9) | 3 (3.0) | 0.45 β |

| Body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 115 (31.6) | 95 (35.8) | 20 (20.2) | 0.0043 |

| Cardiac ejection fraction < | 35 (9.6) | 21 (7.9) | 14 (14.0) | 0.077 |

| Reduced pulmonary function 50% £ | 69 (18.8) | 33 (12.4) | 36 (36.0) | < 0.0001 |

| FVC 75–79% predicted | 19 (5.2) | 12 (4.5) | 7 (7.0) | |

| FVC 50–74% predicted | 34 (9.3) | 16 (6.0) | 18 (18.0) | |

| FVC < 50% predicted | 6 (1.6) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (5.0) | |

| FEV1 70–79% predicted | 30 (8.2) | 19 (7.1) | 11 (11.0) | |

| FEV1 60–69% predicted | 17 (4.6) | 5 (1.9) | 12 (12.0) | |

| FEV1 50–59% predicted | 9 (2.5) | 3 (1.1) | 6 (6.0) | |

| FEV1 < 50% predicted | 6 (1.6) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (5.0) | |

| Six-minute walk | ||||

| Distance (meters) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 547.5 (113.1) | 545.1 (116.0) | 554.8 (104.0) | 0.49 |

| Physiologic cost index | ||||

| Mean | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.2 | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.56 |

When thoracotomy/rib resection compared to thoracoscopy/none.

Fisher exact test.

When white compared with non-white. Bolded p values indicate statistically significant differences, mg/m2=milligrams per square meter, kg/m2=kilograms per square meter, SD=standard deviation, N=number, FVC=Forced vital capacity, FEV1=Forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

As noted by Common Terminology for Adverse Events, version 4.01, pulmonary chronic condition grade 1 or greater.

Predictors of scoliosis

The treatment-related risk factors for scoliosis are shown in Table 2. In adjusted models, when compared to no thoracic procedure or thoracoscopy alone, rib resection [RR: 2.64 (95% CI: 1.79–3.89)] was associated with an increased risk of developing scoliosis. Chest radiation [RR: 1.88 (95% CI: 1.21–2.92)] was also associated with an increased incidence of scoliosis. Age at diagnosis or evaluation, sex, race, and bony resections (including amputation and limb-salvage procedures) were not independent predictors of developing scoliosis.

Table 2.

Treatment related predictors of scoliosis

| Total N (N=367) | % of Total N with scoliosis (N=100) | Relative Risk* | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thoracic surgery | ||||

| None/thoracoscopy | 298 | 22.8 | Referent | |

| Thoracotomy | 43 | 25.6 | 1.08 | 0.63–1.84 |

| Rib resection | 26 | 80.8 | 2.64 | 1.79–3.89 |

| Chest radiation | ||||

| No | 324 | 22.8 | Referent | |

| Yes | 43 | 60.5 | 1.88 | 1.21–2.92 |

| Limb outcome | ||||

| None | 235 | 28.5 | Referent | |

| Limb salvage only | 35 | 34.3 | 1.63 | 0.95–2.77 |

| Amputation | 97 | 21.6 | 1.02 | 0.65–1.60 |

Adjusted for age at diagnosis, age at evaluation, sex and race, none of which were statistically significant, N=number

Thirty-five patients with scoliosis received rib resections, radiation, or both. Of the patients who had surgery alone (n=9), seven (77.8%) had the apex of scoliosis towards to the surgical side. Fourteen patients had radiation alone (without rib resection). Of these, seven (50%) had the apex of their scoliosis towards the radiation. Two had the apex of scoliosis away from the radiated side. The others received radiation to both lungs or the midline. Twelve patients received both rib resection and radiation. Nine of these patients had the apex of the scoliosis towards the treated side. One patient had the apex away from the treated side, and the final two patients had two curvatures in the spine. Of the 21 patients who received rib resection, 16 (80.8%) had the apex of scoliosis towards the surgical side, while patients who received radiation (n=25), sixteen (64%) had the apex of scoliosis towards the radiated side.

Scoliosis, pulmonary function and submaximal exercise capacity

Pulmonary function was impaired (pulmonary chronic condition grade 1 or greater) in 18.8% of survivors; 85.5% of whom had reduced FVC and 89.9% of whom had reduced FEV1 (Table 1). Table 3 shows the association between pulmonary function and scoliosis, chest radiation, cardiac ejection fraction grade and anthracyclines. In adjusted models, participants with scoliosis were more likely than those without scoliosis to have a grade 1–4 pulmonary chronic condition [RR: 1.74 (CI: 1.14–2.66)] when compared to those without scoliosis. After adjusting for age, age at diagnosis, sex, race, height, ejection fraction, and amputation status, we did not find an association between either scoliosis or pulmonary function (of either grade 1 or higher or grade 2 or higher) and distance walked in six minutes or the physiological cost index during walking. However, 39 patients did not complete the six minute walk test, 17 had amputation and were non-functionally ambulatory, eight had acute musculoskeletal conditions, seven had acute cardiac findings and seven declined the test. Of these 39, 29 had no evidence of pulmonary dysfunction, one had a grade 1 condition, six a grade 2 condition, 1 a grade 3 condition and 2 a grade 4 condition.

Table 3.

Risk factors for pulmonary function.

| Total N (N=367) | % of Total N with reduced pulmonary function# (N=69) | Relative Risk* | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current age (year) | 1.03 | 1.00–1.05 | ||

| Scoliosis | ||||

| No | 267 | 12.4 | Referent | |

| Yes | 100 | 36.0 | 1.74 | 1.14–2.66 |

| Chest radiation | ||||

| No | 324 | 12.0 | Referent | |

| Yes | 43 | 69.8 | 4.60 | 2.88–7.34 |

| Cardiac ejection fraction | ||||

| Grade 0 or 1 | 331 | 16.6 | Referent | |

| Grade 2, 3, or 4 | 35 | 37.1 | 2.00 | 1.23–3.24 |

| Anthracyclinesa | ||||

| None | 102 | 6.9 | Referent | |

| < 300 mg/m2 | 75 | 25.3 | 2.34 | 1.07–5.13 |

| ≥300 mg/m2 | 189 | 22.8 | 2.25 | 1.06–4.78 |

Reduced pulmonary function refers to any grade 1–4 pulmonary chronic condition.

Adjusted for age at diagnosis, sex, race, and obesity status, none of which were statistically significant.

One survivor’s anthracycline dose was not available. Abbreviations: N=number, mg/m2=milligrams per square meter.

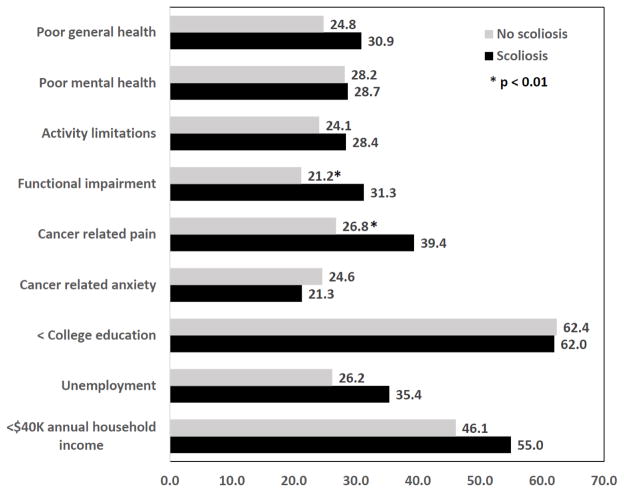

Self-reported outcomes of sarcoma survivors

Figure 2 shows the percentage of survivors reporting poor health status outcomes and less than optimal social role attainment by scoliosis status. Overall, poor general health was reported by 26.5%, poor mental health by 28.4%, activity limitations by 25.3%, functional impairment by 24.9%, cancer related pain by 30.2%, and cancer related anxiety by 23.7% of survivors. Nearly two-thirds (62.3%) of survivors reported no college education, 28.7% were unemployed, and 48.5% had annual household incomes < $40,000. In analyses adjusted for age at diagnosis and evaluation, sex, race, obesity status, cardiac ejection fraction < 50%, pulmonary impairment and amputation, the only two health status or social role outcomes associated with scoliosis were functional impairment [RR:1.60 (95% CI 1.07–2.38)] and cancer related pain [RR: 1.55 (95% CI 1.11–2.16)].

Figure 2.

Percentage of survivors with adverse health status outcomes or less than optimal social role attainment by scoliosis status.

DISCUSSION

This is the largest, single-institution report of functional, health, and social outcomes in sarcoma survivors with scoliosis. With a median follow-up of greater than 20 years, this cohort highlights significant treatment-related predictors for the development of scoliosis in long-term sarcoma survivors–most notably, rib resection, and chest radiation. Spinal curvatures following thoracic surgical procedures early in life can have significant impact upon growth and later pulmonary function [22, 23]. Previous research has indicated a higher incidence of scoliosis in patients undergoing rib or chest wall resections. However, the long-term incidence of scoliosis in pediatric oncology patients undergoing thoracotomy has not been well studied [10, 24]. In a retrospective study of 40 children who had undergone rib resection for malignant chest wall tumors (mean age at surgery 9.8 years, range: 0.2–19 years), Scalabre et al. identified scoliosis in 43% with risk significantly associated with the number of ribs resected. In our study, while rib resections were associated with an increased risk of developing scoliosis, thoracotomy alone (without the resection of a rib) was not associated with the long-term development of scoliosis. Secondly, the side of surgery (with or without radiation to that side) appears to correlate (> 75%) with the side of scoliosis. This may be due to lack of structural support supplied by the ribs to the spine causing the spine to fall into this void, and patients therefore leaning away from the side of resection in an attempt to compensate with standing mechanics. In this population, this correlation was not seen with the side of radiation therapy, where one would suspect that patients would lean towards the radiated side due to fibrosis and asymmetry in bone growth.

Scoliosis can have significant impact upon the long-term health of cancer survivors. In the current study, patients with scoliosis were found to have a higher prevalence of adverse pulmonary function outcomes, although neither scoliosis nor abnormal pulmonary function (measured either as a dichotomy or as continuous values of FVC and FEV1) was associated with impaired submaximal exercise capacity measured with the six-minute walk test. Pulmonary dysfunction in children with scoliosis has been previously studied [6, 25]. Denbo and colleagues reported that osteosarcoma survivors who required lung resection had worse pulmonary function, but this association in survivors with scoliosis had not been previously reported [26]. The lack of association between impaired pulmonary function and performance on the six-minute walk test is unexpected. The six-minute walk test is commonly used as a surrogate of overall fitness, and others have used it to gauge the functional capacity of patients with chronic respiratory and cardiac illnesses, as well as musculoskeletal disorders [27, 28]. This test, however, may not be an optimal tool to study this otherwise young population. Other tests, such as oxygen consumption, may be more sensitive in identifying patients whose pulmonary dysfunction interferes with daily life [29]. Lastly, not all patients completed the six-minute walk test. One third of these patients did have abnormal pulmonary function which is likely to have biased our results toward the null. We have previously demonstrated an association between pulmonary function and performance on the six minute walk test in the overall SJLIFE cohort [7].

Significant research has been done in the past on the effects of scoliosis in patients. Weinstein and colleagues reported an estimated decrease in survival in untreated patients with idiopathic scoliosis [30]. Patients in that study also reported a higher incidence of shortness of breath and chronic back pain. While the patients presented in this study may have been followed more closely over time than those patients, it highlights the importance of close follow-up for physical and psychosocial limitations. Additionally, patients may benefit from early diagnosis and physical therapy. Lastly, patients with severe scoliosis and significant pulmonary and cardiovascular limitations may benefit from surgical correction.

This study has several limitations. Most notably, the majority of these patients were not clinically diagnosed with scoliosis, rather imaging was reviewed retrospectively to identify patients with scoliosis. This may introduce some misclassification bias as not all imaging studies were identical. Participation in SJLIFE was approximately 65%, which may also bias results. Additionally, we were unable to determine the onset or date of diagnosis of scoliosis. Moreover, we classified patients as having any rib resected rather than a chest wall resection, which usually refers to at least three ribs resected. The impact of the number of ribs on the risk of scoliosis was not analyzed in this study. The rib resected was also not factored into the rate of scoliosis, where floating ribs of the rib cage may have less of an effect on spinal curvature. Lastly, while we present a large cohort of patients treated during a long period of time, other factors over many years may have contributed to the patients’ medical comorbidities contributing to their functional capacity.

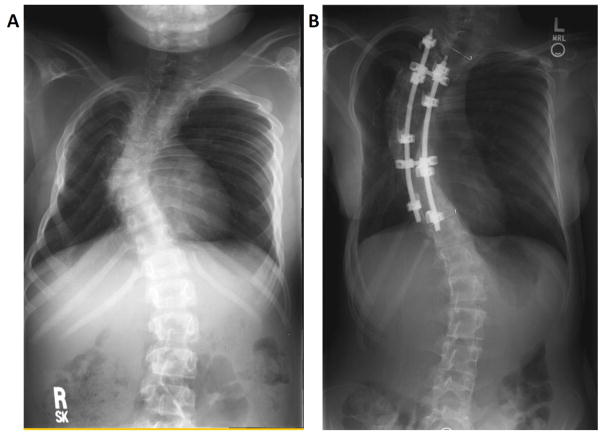

This study adds to the body of recent work focused on identifying significant adverse health outcomes in adult survivors [31] by documenting problems specific to sarcoma survivors with scoliosis. Sarcoma survivors exposed to rib resection and radiation therapy to the thorax are at risk for developing scoliosis over time (Figure 3). This condition may further affect patient’s pulmonary function and self-reported functional outcomes. Given that these patients are still young, they may suffer worsening if this condition goes unrecognized and untreated. Long-term survivors of sarcoma with scoliosis may need referral for pain management and/or physical or pulmonary rehabilitation to help improve their daily function. Early initiation of preventative or remedial measures in patients who undergo chest wall resection and receive radiation may help reduce the impact of such therapy on pulmonary function, functional capacity and quality of life.

Figure 3.

Radiologic imaging of two separate patients with scoliosis. A. Patient A was diagnosed at one year of age with an epithelioid sarcoma of the posterior mediastinum and lungs, and received a right-sided thoracotomy and chest radiation. B. Patient B is a female diagnosed at 3.6 years of age with a Ewing sarcoma of the right chest wall, and received a right chest wall resection of ribs five through eight, who subsequently underwent rod placement at 14 years of age.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the assistance from the clinical and research staff of the St. Jude Lifetime (SJLIFE) Cohort study and After Completion of Therapy clinic at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in helping to compile the data.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute Grant (CA-195547) and Cancer Center Support (CORE) Grant (CA-21765) St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Ferrari A, Sultan I, Huang TT, et al. Soft tissue sarcoma across the age spectrum: a population-based study from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011 Dec 1;57(6):943–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez-Pineda I, Hudson MM, Pappo AS, et al. Long-term functional outcomes and quality of life in adult survivors of childhood extremity sarcomas: a report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2016 Jun 4; doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0556-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gawade PL, Hudson MM, Kaste SC, et al. A systematic review of selected musculoskeletal late effects in survivors of childhood cancer. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2014;10(4):249–62. doi: 10.2174/1573400510666141114223827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koumbourlis AC. Scoliosis and the respiratory system. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2006 Jun;7(2):152–60. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Llorens J, Ramirez M, Colomina MJ, et al. Muscle dysfunction and exercise limitation in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur Respir J. 2010 Aug;36(2):393–400. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00025509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsiligiannis T, Grivas T. Pulmonary function in children with idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis. 2012;7(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green DM, Zhu L, Wang M, et al. Pulmonary Function after Treatment for Childhood Cancer. A Report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE) Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016 Sep;13(9):1575–85. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201601-022OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Liu Y, et al. Pulmonary complications in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer. A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2002 Dec 1;95(11):2431–41. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasilewski-Masker K, Kaste SC, Hudson MM, Esiashvili N, Mattano LA, Meacham LR. Bone mineral density deficits in survivors of childhood cancer: long-term follow-up guidelines and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2008 Mar;121(3):e705–e13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scalabre A, Parot R, Hameury F, Cunin V, Jouve JL, Chotel F. Prognostic risk factors for the development of scoliosis after chest wall resection for malignant tumors in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014 Jan 15;96(2):e10. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ojha RP, Oancea SC, Ness KK, et al. Assessment of potential bias from non-participation in a dynamic clinical cohort of long-term childhood cancer survivors: results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013 May;60(5):856–64. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Nolan VG, et al. Prospective medical assessment of adults surviving childhood cancer: study design, cohort characteristics, and feasibility of the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011 May;56(5):825–36. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Executive summary of the clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Sep 28;158(17):1855–67. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss HR, Negrini S, Rigo M, et al. Indications for conservative management of scoliosis (guidelines) Scoliosis. 2006;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Jan;159(1):179–87. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. [Accessed September 1, 2016];Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.03. Available at: http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_8.5x11.pdf.

- 17.Laboratories ATSCoPSfCPF. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Jul 1;166(1):111–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raj R, Mojazi Amiri H, Wang H, Nugent KM. The repeatability of gait speed and physiological cost index measurements in working adults. J Prim Care Community Health. 2014 Apr 1;5(2):128–33. doi: 10.1177/2150131913506226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2003 Sep 24;290(12):1583–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 May 15;157(10):940–3. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Apr 1;159(7):702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seghaye MC, Grabitz R, Alzen G, et al. Thoracic sequelae after surgical closure of the patent ductus arteriosus in premature infants. Acta Paediatr. 1997 Feb;86(2):213–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb08871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sistonen SJ, Pakarinen MP, Rintala RJ. Long-term results of esophageal atresia: Helsinki experience and review of literature. Pediatr Surg Int. 2011 Nov;27(11):1141–9. doi: 10.1007/s00383-011-2980-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawakami N, Winter RB, Lonstein JE, Denis F. Scoliosis secondary to rib resection. J Spinal Disord. 1994 Dec;7(6):522–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McPhail GL, Ehsan Z, Howells SA, et al. Obstructive lung disease in children with idiopathic scoliosis. J Pediatr. 2015 Apr;166(4):1018–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denbo JW, Zhu L, Srivastava D, et al. Long-term pulmonary function after metastasectomy for childhood osteosarcoma: a report from the St Jude lifetime cohort study. J Am Coll Surg. 2014 Aug;219(2):265–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gungor G, Karakurt Z, Adiguzel N, et al. The 6–minute walk test in chronic respiratory failure: does observed or predicted walk distance better reflect patient functional status? Respir Care. 2013 May;58(5):850–7. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald CM, Henricson EK, Abresch RT, et al. The 6-minute walk test and other clinical endpoints in duchenne muscular dystrophy: reliability, concurrent validity, and minimal clinically important differences from a multicenter study. Muscle Nerve. 2013 Sep;48(3):357–68. doi: 10.1002/mus.23905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kern L, Condrau S, Baty F, et al. Oxygen kinetics during 6-minute walk tests in patients with cardiovascular and pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Spratt KF, Peterson KK, Spoonamore MJ, Ponseti IV. Health and function of patients with untreated idiopathic scoliosis: a 50-year natural history study. JAMA. 2003 Feb 5;289(5):559–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.5.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013 Jun 12;309(22):2371–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]