Abstract

Background

In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) proposed nine graphic health warnings (GHWs) on cigarette packaging that were rated equally effective across racial/ethnic, education, or income groups of adult smokers. However, data on GHW effectiveness among sexual and gender minority (SGM) adults, who have higher smoking prevalence, is currently lacking. This study analyzed whether perceived effectiveness of GHWs differed by gender and sexual orientation.

Methods

Data came from a randomized experiment among 1200 adults with an oversample from low socioeconomic status groups, conducted between 2013 and 2014 in three Massachusetts communities. Participants viewed and rated the effectiveness of nine GHWs. Mixed effects regression models predicted perceived effectiveness with gender and sexual orientation, adjusting for repeated measurements, GHWs viewed, age, race, ethnicity, smoking status, and health status.

Results

Female heterosexuals rated GHWs as more effective than male heterosexual, lesbian, and transgender and other gender respondents. There was no significant difference between female and male heterosexuals versus gay, male bisexual, or female bisexual respondents. Differences by gender and sexual orientation were consistent across all nine GHWs. Significant correlates of higher perceived effectiveness included certain GHWs, older age, being African-American (versus white), being Hispanic (versus non-Hispanic), having less than high school education (versus associate degree or higher), and being current smokers (versus non-smokers).

Conclusions

Perceived effectiveness of GHWs was lower in certain SGM groups. We recommend further studies to understand the underlying mechanisms for these findings and investments in research and policy to communicate anti-smoking messages more effectively to SGM populations.

Keywords: tobacco cigarettes, graphic health warnings, perceived effectiveness, sexual and gender minorities, message testing, United States

INTRODUCTION

In the U.S. sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations (including individuals who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer, and individuals who have same-sex relationships and/or attraction) have much higher smoking prevalence (27%) compared with their heterosexual counterparts (17%), based on the 2012–2013 National Adult Tobacco Survey.[1] SGM persons therefore bear a disproportionate burden of smoking-related health consequences even as national smoking prevalence has declined. For instance, gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth are more likely to initiate smoking at earlier ages than heterosexual youth.[2] An analysis of data from the 2003–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) found that 36% to 45% of women aged 20 to 59 years who are lesbian, bisexual, or homosexually experienced were current cigarette smokers, compared with 22% of heterosexual women.[3] In addition, 56% of lesbian and 48% of homosexually experienced women who were nonsmokers were exposed to secondhand smoke, compared with 33% of heterosexual women who were nonsmokers.[3] In a national survey in 2013, Buchting and colleagues reported that compared with cisgender adults, transgender adults had between two to five times higher odds of current use of tobacco products including cigarettes (36% vs 21%), cigars (27% vs 9%), and e-cigarettes (21% vs 5%).[4]

Several factors are implicated as reasons for the higher prevalence of smoking and smoking-related health problems among SGM populations. Some researchers have pointed to increased likelihood of victimization, violence, and perceived or actual stigma as underlying factors that increase smoking in this population.[5–8] Others have reported that mental health issues, depression, alcohol and substance use, and lack of social support among SGM individuals could be risk factors of smoking.[6, 9] The role of the bar culture in SGM populations has also been implicated as a reason influencing permissive attitudes and norms to smoke in this population.[10, 11] In addition, the tobacco industry’s increased targeted marketing to SGM populations in recent decades is well documented.[12–15] This has led to greater exposure to marketing messages [16] and increased receptivity to industry messages among SGM persons.[17]

The U.S. national smoking prevalence has declined steadily since the 1960s, from a peak of 42% in 1965 to 15% in 2015.[18] This trend is largely due to smoke-free laws, taxation of cigarettes, restriction of youth access, provision of cessation treatments, and mass media anti-smoking campaigns.[19] Despite decades of general population-level interventions, there are persistent disparities in smoking prevalence and burden from smoking across social groups, including among SGM. Evidence suggests that increases in tobacco prices help to narrow socioeconomic disparities in tobacco use.[20, 21] There is mixed or no evidence that smoke-free laws, media campaigns, advertising bans, health warnings, or multifaceted community interventions impact socioeconomic gradients in tobacco use.[20, 22] In addition, there is consistent evidence that smoking cessation support widens socioeconomic disparities in tobacco use.[20] Based on a systematic review by Lee and colleagues, there is currently insufficient research on the impact of community, policy, and media interventions on tobacco disparities among SGM.[23] The authors recommended research to identify whether tailored community interventions improve cessation outcomes and to examine best strategies for targeted messaging in LGBT media interventions. These recommendations are echoed in a recent position statement by Matthews and colleagues, representing the Society of Behavioral Medicine, to include “specific messaging for gender and sexual minorities in all media campaigns aimed at increasing education and outreach regarding tobacco prevention and smoking cessation treatment services”.[24] It is therefore important to evaluate whether current and forthcoming tobacco control interventions and policies are effective in addressing tobacco disparities among SGM populations.

Under the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, the U.S. FDA announced in 2011 that graphic health warnings (GHWs) would be required on cigarette packaging beginning in 2012. GHWs were intended to cover 50% of cigarette packaging with pictures and words to communicate the health risks of smoking. In 2016, GHWs have been successfully implemented in 105 countries and are effective in encouraging smoking cessation among smokers.[25–28] The U.S. FDA selected nine GHWs as part of the first round of warning labels in 2012. However, the status of implementing GHWs on cigarette packaging is currently uncertain following the ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit in the 2012 case, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. Food and Drug Administration, that the GHWs requirement was unconstitutional. This court ruling did not invalidate FDA’s mandate to develop GHW rules. The FDA decided not to appeal the decision at the Supreme Court and stated in 2013 that it planned to reissue new GHW rules.[29]

Previous studies found that FDA-proposed graphic health warnings (GHWs) were rated equally effective across racial/ethnic, education, or income groups of adult smokers.[30, 31] A systematic review concluded that there was no evidence that health warnings impacted socioeconomic inequalities in smoking.[20] In one randomized clinical trial, smokers who were randomly assigned to receive four of the nine FDA-proposed GHWs on their cigarette packs over four weeks (versus those who received text-only warnings) were more likely to make a quit attempt lasting at least one day (40% vs. 34%, respectively). By the end of the study period, those who received GHWs were also more likely to report quitting for at least seven days than those who received text-only warnings (6% vs. 4%). These GHW effects were equally effective across demographic groups, including among gay, lesbian, and bisexual smokers versus heterosexual smokers.[28] However, the full set of nine GHWs has not yet been evaluated for their effectiveness to discourage smoking among SGM populations. In addition, gay, lesbian, and bisexual smokers were grouped within a single category, which did not permit analysis of differences between each of these sexual minority groups versus heterosexual adults.

In this paper, we analyzed data from Project CLEAR, conducted in 2013–2014 to study the potential impact of the GHWs among a diverse sample of adults with an oversampling of those from lower socioeconomic status groups. We compared perceived effectiveness of the nine proposed GHWs between SGM and heterosexual persons. We focused on perceived effectiveness because these measures are frequently employed in formative research for health messaging and have been shown to positively correlate with actual effectiveness in a variety of contexts, including anti-smoking messages.[32, 33] This analysis may identify potential gaps in the effectiveness of anti-smoking messages through GHWs to reduce tobacco health disparities among priority populations.

Theoretical Framework

The analysis is informed by the concept of communication inequalities within the Structural Influence Model of Communication (SIMC), which hypothesizes that inequalities in health communication have important roles in mediating relationships between social determinants (e.g., gender, sexual orientation, race, education, income), access to health care resources, and more distal health outcomes (e.g., health behaviors, adherence, treatment outcomes).[34–36] Communication inequalities can occur between social groups in their exposure and attention to health information, external information seeking about health concerns, and processing of health information. Inequalities in these communication outcomes can, in turn, contribute to widened gaps in health knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors between social groups.

Directly relevant to the present study are differences in individuals’ information processing of GHWs and comparisons between SGM and heterosexual populations. Targeted strategies are common in marketing and public health counter-marketing.[37] A number of theoretical approaches predict that minorities would be expected to seek out and evaluate more favorably materials that resonate with salient identities, thus increasing the likelihood of persuasive impact.[38] The tobacco industry has targeted minority communities with ad content tailored to particular demographic groups and identities, including SGM. Strategies include use of group-specific media channels and inclusion of models that reflect the demographics of the targeted group.[39–41] Group cues, such as demographically matched exemplars, have been found to influence selective exposure among some minority groups.[42] However, a survey found that SGM recalled seeing relatively few anti-tobacco messages in SGM-specific media; there were also indications that mainstream anti-tobacco messages may not resonate with some SGM.[23, 43] Graphic warnings, therefore, present a promising avenue for anti-smoking messages for SGM. However, we do not yet know whether SGM persons perceive anti-smoking messages such as those on GHWs to be effective, compared with their heterosexual counterparts. If so, such differences could result in differences in effectiveness of GHWs to activate intentions to quit smoking or to avoid initiation of smoking among SGM populations, thereby perpetuating smoking-related health disparities.

Intersectionality theory further provides a useful framework for understanding communication inequalities and tobacco-related health disparities, based on the complex interactions between multiple sources of discrimination and stigma due to gender and sexual identity.[44] Studies have found tobacco-related differences when considering the combined SGM categories that take both gender and sexual orientation into account.[2, 5] There can also be differences in how lesbians and gay men evaluate ad content.[45] Based on the possibility of differential information processing raised by the SIMC and intersectionality theory, and given the potential for distinct group-based experiences and identities for those who are female and SGM (e.g., lesbian, bisexual female) and male and SGM (gay, bisexual male), there may be corresponding differences in GHW perceived effectiveness based on gender and sexual orientation of SGM populations. We therefore pose the following research question: Do perceptions of GHW effectiveness vary across SGM populations when compared with heterosexual males and females?

METHODS

Study sample and data collection

Data for this analysis were obtained from Project CLEAR, an FDA-funded project focused on studying the impact of FDA-proposed GHWs among diverse populations. Participants were recruited from diverse gender, sexual orientation, racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds in three Massachusetts communities (Boston, Lawrence, and Worcester). A purposive sample of 1200 participants with an oversample from low socioeconomic status groups was recruited at baseline through partnerships with Massachusetts-based community organizations (Alliance for Community Health in Boston, Common Pathways in Worcester, and The Mayor’s Health Task Force (MHTF) in Lawrence), flyers placed in community locations, and through word of mouth. Eligible participants were individuals who were 18 to 70 years, able to communicate in English or Spanish, and belonged to one of the following populations: Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic, low socioeconomic status (SES), SGM, or blue-collar workers.

The survey instrument was developed following extensive literature review of validated measures from previous research, focus group discussions among participants of diverse racial/ethnic and sociodemographic backgrounds,[46] and key informant interviews (among local government officials, clinicians from local health centers, and advocacy groups). We further conducted cognitive testing among a separate group of participants to ensure that the survey questionnaire and administration on tablet computers would be appropriate for low literacy participants and made adjustments before fielding the main survey.

From August 2013 to April 2014, we conducted in-person self-administered baseline surveys among 1200 adults (18–70 years) at community locations such as senior centers, community colleges, trade unions, and housing developments. When participants arrived at the survey site, they were asked to complete a study eligibility form and were given materials to read about the study. Once eligibility was determined and written consent was provided, participants completed the survey on a computer or electronic tablet. They were first asked questions about their income, education, smoking habits, and beliefs about smoking. Next, they were shown one of the nine warning labels (Figure 1) and asked questions about its effectiveness, emotional responses to the label, and if it encouraged them to quit (among smokers) or made them glad they did not smoke (among nonsmokers). They then answered questions about the effectiveness of the remaining eight labels. An incentive was provided at the completion of the survey ($50 gift card). The university’s institutional review board approved the study.

Figure 1.

FDA-proposed graphic health warnings

Measures

Outcome variable – Perceived effectiveness

We measured perceived effectiveness of each GHW with a global measure, “Overall, on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is “not at all effective” and 5 is “very effective,” how effective would you say this warning label is?” This item is similar to those used in previous studies that evaluated overall perceived effectiveness of pictorial tobacco health warnings among youth and adults.[47] As described earlier, perceived effectiveness has been demonstrated as a theoretical and empirically meaningful outcome.[32, 33]

Predictor variables – Gender and sexual orientation

Gender was measured using a single item, “What is your gender?” Response options were male, female, transgender, or other. Participants were asked about their sexual orientation: “Which of the following best describes you?” Response options were heterosexual (straight), gay or lesbian, bisexual, or not sure. Based on participants’ responses to both questions, we categorized them to one of seven gender and sexual orientation identities: male heterosexual, female heterosexual, gay, lesbian, male bisexual, female bisexual, and transgender or gender nonconforming. We excluded 24 respondents who responded “not sure” to the question about their sexual orientation and 8 respondents who had missing responses to either question, because we were unable to ascertain if they identified as SGM.

Covariates

We included age, race (White, African-American, or other), Hispanic (versus non-Hispanic), education (below high school, high school/GED, some college, or associate degree or higher), smoking status (nonsmoker, former smoker, or current smoker), and self-reported general health status (5-point scale from 1 ‘Poor’ to 5 ‘Excellent’) as covariates.

Data Analysis

We analyzed the effectiveness ratings of each GHW by gender and sexual orientation (see Appendix 1). We fitted a mixed effects regression model to analyze the associations between perceived effectiveness and gender and sexual orientation categories. A random effects term was added to account for repeated measurements clustered within individuals because each participant viewed and rated the effectiveness of all nine labels. Although SGM participants comprised a minority of the study sample, the mixed effects regression analysis provided stable point estimates of the coefficients for each SGM category due to the collection of repeated measurements of perceived effectiveness. The model also adjusted for the GHW viewed and covariates (age, race, ethnicity, education, smoking status, and health status) due to potential differences in smoking rates and attitudes toward GHWs across these factors.[48, 49] We tested whether the association between perceived effectiveness and gender and sexual orientation categories differed by the GHW viewed by introducing interaction terms between GHW (1 through 9) and the gender and sexual orientation categories. However, these interaction terms were not significant as a block and were dropped from the final model. The amount of missing data across all variables was minimal (1.9%), and listwise deletion was utilized for handling missing values in the regression analysis. The final analytic sample was 1149.

To assist in the interpretation of the mixed effects regression results, we computed the predicted means of perceived effectiveness by SGM category, holding all other variables at their respective means. Analyses were conducted using the ‘xtmixed’ and ‘margins’ program in Stata version 13. We presented the analyses using female heterosexuals as the referent group because of prior research indicating larger disparities in tobacco use behaviors between female sexual and gender minorities versus female heterosexuals, compared with the differences between male sexual and gender minorities and male heterosexuals. For instance, data from national surveys indicate that differences in menthol cigarette use prevalence were more prominent among female sexual and gender minorities versus female heterosexuals than the differences between male sexual and gender minorities versus male heterosexuals.[50] Second, there are differences in smoking characteristics between female lesbians and bisexuals compared with female heterosexuals (e.g., nicotine dependence, earlier age of smoking initiation, heavier smoking intensity, and fewer past quit attempts among female sexual minorities), but no evidence of significant differences between gay and bisexual men versus heterosexual men.[51] However, results presenting male heterosexuals as the referent group are available upon request.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Approximately 12% of the sample identified as one of the SGM groups (individual SGM categories ranged from 1.3% to 3.9% of the sample), 45.3% were male heterosexuals, and 42.6% were female heterosexuals. Mean age of the sample was 33.1 years (ranged from 18–70 years), 41% were White, 38% were African-American, 22% were other race, 38% were of Hispanic origin, and 16% completed college education or higher. Other characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. Characteristics of study participants by gender and sexual orientation are further detailed in Appendix 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants in Boston, Lawrence, and Worcester, 2013 (n=1168)

| Mean (SD) | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender and sexual orientation | |||

| Male heterosexual | 529 | 45.3 | |

| Female heterosexual | 498 | 42.6 | |

| Gay | 25 | 2.1 | |

| Lesbian | 39 | 3.3 | |

| Male bisexual | 16 | 1.4 | |

| Female bisexual | 46 | 3.9 | |

| Transgender and other | 15 | 1.3 | |

| Age (ranged from 18–70 years) | 33.1 (14.2) | ||

| Race | |||

| White | 477 | 40.8 | |

| African-American | 439 | 37.6 | |

| Other | 252 | 21.6 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 728 | 62.3 | |

| Hispanic | 440 | 37.7 | |

| Educationa | |||

| Some high school | 180 | 15.6 | |

| High school/GED | 448 | 38.7 | |

| Some college | 341 | 29.5 | |

| Associate degree or higher | 188 | 16.3 | |

| Smoking Statusb | |||

| Non-smoker | 539 | 46.4 | |

| Former | 150 | 12.9 | |

| Current | 472 | 40.7 | |

| Health Statusc (scale of 1–5 from poor to excellent) | 3.5 (1) |

Notes.

11 cases missing education level;

7 cases missing smoking status;

1 case missing health status.

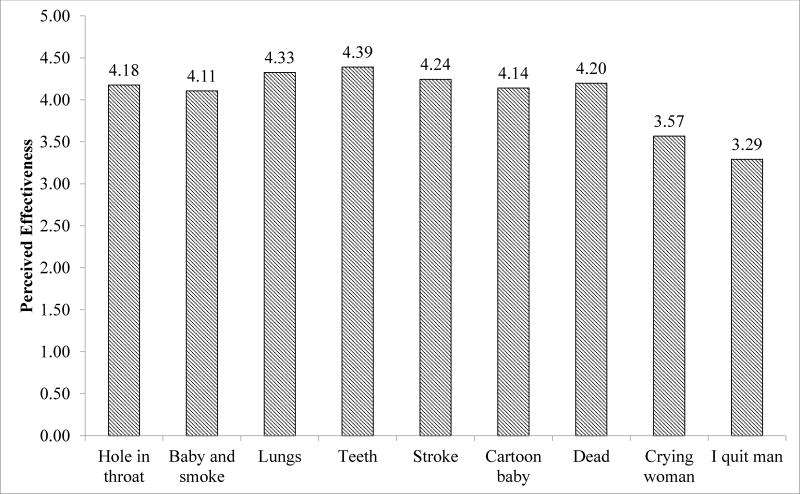

Perceived effectiveness of each graphic health warning

Figure 2 shows the unadjusted mean perceived effectiveness of each GHW across the analytic sample. Most of the GHWs were rated as moderately or highly effective (means between 4 and 5 on the perceived effectiveness scale). Two of the GHWs (‘crying woman’ and ‘I quit man’) were rated less effective on the scale (means were 3.57 and 3.29, respectively).

Figure 2.

Mean perceived effectiveness of each graphic health warning

Multiple regression analyses predicting perceived effectiveness of GHWs

Table 2 shows the mixed effects regression analysis predicting perceived effectiveness of the proposed GHWs. Male heterosexuals, lesbians, and transgender or gender nonconforming persons had lower ratings of perceived effectiveness of GHWs compared with female heterosexuals. Gay men, male bisexuals, and female bisexuals did not express significantly different perceived effectiveness compared with female heterosexuals. Perceived effectiveness among the other SGM groups did not differ significantly from male heterosexuals (results are available upon request).

Table 2.

Mixed effects regression analysis predicting perceived effectiveness of GHWs among Study Participants in Boston, Lawrence, and Worcester, 2013

| Independent variables | B | (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender and sexual orientation (referent is female heterosexual) | |||

| Male heterosexual | −0.233 | −0.345, −0.121 | <0.001 |

| Gay | −0.189 | −0.532, 0.153 | 0.279 |

| Lesbian | −0.344 | −0.623, −0.065 | 0.016 |

| Male bisexual | 0.004 | −0.424, 0.432 | 0.987 |

| Female bisexual | −0.239 | −0.501, 0.023 | 0.074 |

| Transgender and other | −0.570 | −1.025, −0.116 | 0.014 |

| Graphic health warning (referent is ‘hole in throat’) | |||

| Baby and smoke | −0.075 | −0.148, −0.002 | 0.045 |

| Lungs | 0.145 | 0.072, 0.218 | <0.001 |

| Teeth | 0.212 | 0.139, 0.285 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 0.065 | −0.008, 0.138 | 0.083 |

| Cartoon baby | −0.037 | −0.110, 0.036 | 0.320 |

| Dead | 0.022 | −0.051, 0.096 | 0.552 |

| Crying woman | −0.616 | −0.690, −0.543 | <0.001 |

| I quit man | −0.892 | −0.965, −0.818 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 0.007 | 0.003, 0.011 | <0.001 |

| Race (referent is White) | |||

| African-American | 0.328 | 0.210, 0.446 | <0.001 |

| Other | 0.145 | −0.023, 0.313 | 0.090 |

| Ethnicity (Referent is non-Hispanic) | |||

| Hispanic | 0.238 | 0.095, 0.380 | 0.001 |

| Education (Referent is some high school) | |||

| High school/GED | −0.058 | −0.211, 0.095 | 0.459 |

| Some college | −0.087 | −0.250, 0.076 | 0.294 |

| Associate degree or higher | −0.214 | −0.400, −0.029 | 0.023 |

| Smoking Status (referent is non-smoker) | |||

| Former | −0.025 | −0.189, 0.139 | 0.764 |

| Current | −0.125 | −0.239, −0.010 | 0.033 |

| Health Status (scale of 1–5 from poor to excellent) | −0.020 | −0.072, 0.032 | 0.442 |

| Constant | 4.049 | ||

| Within person random effects (estimate (SE)) | 0.633 (0.03) | ||

| N (Total observations) | 10334 | ||

| N (Individuals)a | 1149 | ||

Note.

Due to a small number of missing data in some variables, the final analytic sample was 1149 based on listwise deletion.

There were differences in perceived effectiveness across GHWs tested in this study, such that three GHWs (‘baby and smoke’, ‘crying woman’, and ‘I quit man’) were rated as less effective than the referent ad (‘hole in the throat’). Two GHWs (‘lungs’ and ‘teeth’) were rated as more effective than the referent ad. Other significant predictors were older age, being African-American (versus White), being Hispanic (versus non-Hispanic), having lower than high school education (versus associate degree or higher), and being a current smoker (versus non-smoker).

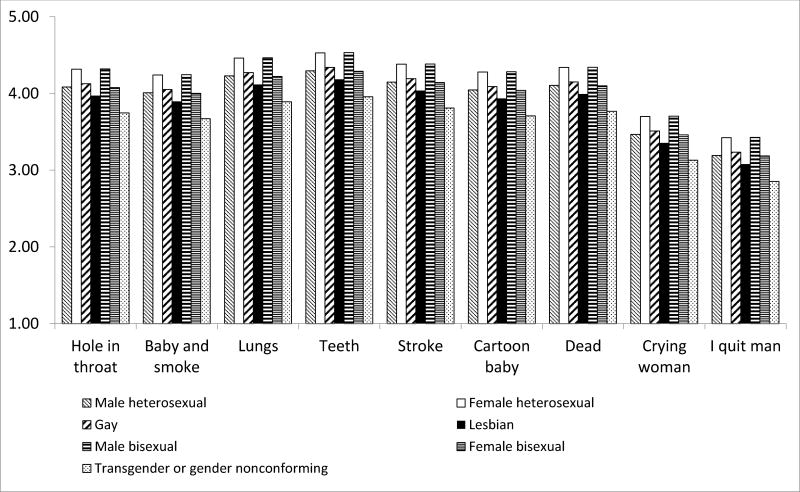

Figure 3 shows the predicted perceived effectiveness of each GHW by gender and sexual orientation category based on the mixed effects regression coefficients, holding all other variables constant at their respective mean values. Across the nine GHWs, the predicted marginal mean differences were more substantial comparing female heterosexuals with lesbians and with individuals who were transgender or gender nonconforming. Across all gender and sexual orientation categories, the ‘crying woman’ and ‘I quit man’ GHWs were rated the lowest in perceived effectiveness.

Figure 3.

Adjusted predicted perceived effectiveness of each graphic health warning by gender and sexual orientation

DISCUSSION

Based on this study among a diverse sample of participants, we found that respondents who identified as either lesbian or transgender or gender nonconforming perceived GHWs to be less effective, compared with female heterosexuals. Notably, female heterosexuals indicated the highest level of perceived effectiveness across all the FDA-proposed GHWs. Transgender or gender nonconforming individuals indicated the lowest levels of perceived effectiveness. There were significant differences in perceived effectiveness between female heterosexuals and certain SGM populations (lesbians and transgender or gender nonconforming). To our knowledge, this is the first study to report differences in the way that SGM persons perceive anti-smoking information from cigarette packaging GHWs compared with heterosexuals. We discuss potential explanations of these findings as well as implications for policy and future research.

The finding that lesbian and transgender or gender nonconforming persons evaluated anti-tobacco GHWs as less effective is concerning from the perspective of tobacco-related health disparities. Such differences in message processing could result in lower effectiveness of GHWs and therefore hinder efforts to encourage smoking cessation in these priority populations. Given that lesbian and transgender or gender nonconforming persons already experience higher smoking prevalence and exposure to secondhand smoke compared to national averages, reduced effectiveness of GHWs in these populations could potentially lead to widened smoking-related health disparities.[1, 3, 4] Further research will be needed to examine whether the differential perceived effectiveness of GHWs among these groups is associated with poorer smoking-related outcomes, if and when GHWs are eventually implemented in the U.S. Additional research is also needed to determine ways to minimize inequalities in information processing of anti-smoking messages between lesbian and transgender or gender nonconforming persons and heterosexuals.

One possible reason that could explain why lesbian and transgender or gender nonconforming persons were less likely to find the FDA-proposed GHWs to be effective compared with heterosexuals is that GHWs may not tap into specific beliefs and attitudes about smoking cessation that are salient for these individuals. For instance, Burkhalter and colleagues [52] reported that SGM persons tend to be motivated by the idea that they would feel more like the person they want to be if they quit smoking (i.e., achieving an ideal self-image). In addition, gender role socialization and masculinity norms encourage men to engage in high-risk behaviors including smoking.[53] To the extent that lesbians may be less likely to conform to gender roles, it may be that their behavior and reactions surrounding tobacco use are more masculine (i.e., more like male heterosexuals and less like female heterosexuals) or are seen as a way to express masculinity. However, more research is needed to understand what is driving the differences between heterosexual women and lesbians, and whether the desire to appear more masculine and/or perceived group norms play a role in lowering perceived effectiveness ratings. More research is also needed to examine reasons for differences between heterosexual women and transgender or gender non-conforming persons.

Other researchers have compared the effectiveness of GHWs among racial/ethnic minorities (versus non-Hispanic Whites) or those who are from lower literacy populations (versus higher literacy), who also suffer disproportionately from the burden of smoking-related health consequences. In contrast to our findings with SGM populations, researchers have found that GHWs were equally effective among racial/ethnic minorities and lower literacy populations.[30, 54] We may observe communication inequalities by gender and sexual orientation and not by race/ethnicity or literacy because there may have been more efforts to conduct formative research and pilot testing of GHWs with racial/ethnic minorities and those from lower socioeconomic position.[30, 31, 55] In comparison, to our knowledge formative research to inform the design of GHWs from the perspectives of SGM populations may be lacking.

Our study findings suggest important implications for policy and communication interventions to address higher prevalence of smoking and smoking-related health problems among SGM populations. First, there is a need to ensure that future public health anti-smoking messages—GHWs, mass media health campaigns, or other forms of communication interventions—are adequately pretested among SGM populations. This will allow tobacco control advocates and practitioners to identify gaps in the effectiveness of anti-smoking messages among SGM populations. It will also increase our understanding of important motivators for avoiding smoking that are unique to SGM persons. Second, differential effectiveness of GHWs by gender and sexual orientation indicates the need to consider targeted media and messaging interventions for certain SGM populations, beyond using GHWs. For instance, one innovative intervention approach utilized social branding to associate a smoke-free lifestyle with values held by specific young adult peer crowds, including SGM young adults who frequent bars and clubs. This social branding approach has been replicated in three cities (Oklahoma City, San Diego, and Las Vegas) and showed promising trends of reducing daily smoking among young adult peer crowds.[56–58] Presently, there is insufficient evidence on the effectiveness of community, policy, and media interventions for SGM populations to conclude if cultural tailoring would be more effective.[23] Further research is needed to assess whether tailored interventions would improve cessation outcomes among SGM persons and to identify best strategies for targeted messaging among different SGM populations.[24]

Strengths and limitations

This study is strengthened by the recruitment of a diverse sample based on race and ethnicity, socioeconomic position (education and employment), and gender and sexual orientation that is uncommon in previous research evaluating the message effectiveness of GHWs. We utilized comprehensive mixed-methods and community-based approaches to ensure that the study design and instruments were culturally appropriate for the study population. Our collaborations with partners within the communities of the study populations further enhances our ability to disseminate research findings to our community partners to inform local interventions. The study design enabled repeated measures of perceived effectiveness across all nine GHWs for all participants. This permitted more robust analyses of differences in overall perceived effectiveness between SGM and heterosexual respondents despite relatively small numbers of several SGM groups.

This study was limited by the inability to generalize the findings beyond the study sample recruited from three cities in Massachusetts. Additional research among SGM persons in other geographic locations is necessary. There were small numbers for some SGM categories (e.g., 15 participants who identified as transgender or gender nonconforming persons). In future research focusing on SGM communication inequalities, additional efforts to ensure higher participation among all SGM persons is needed. Due to survey length limitations, we were not able to assess the underlying mechanisms of certain SGM groups’ reduced perceived effectiveness of GHWs. Qualitative in-depth interviews or focus group discussions among SGM persons may help to increase our understanding. Although a recent study described racial differences in smoking rates among SGM individuals,[59] our study sample did not permit exploring intersectionality based on race, gender, and sexual orientation and differences in perceived effectiveness across different groups. Future research could consider replicating this work with an oversample of SGM individuals from racial minority groups and applying the social resistance framework described by Factor and colleagues for explaining health disparities among racial minorities.[60] We analyzed perceived effectiveness and not actual effectiveness of GHWs (e.g., intentions to quit or quitting behavior); however, in an earlier study, Bigsby and colleagues[33] reported evidence supporting the predictive validity of perceived effectiveness of anti-tobacco messages on smokers’ intention to quit, and a meta-analysis by Dillard and colleagues found a positive correlation between perceived and actual effectiveness in a variety of health contexts.[32]

Conclusion

In sum, our results suggest that certain sexual and gender minority groups found the GHWs proposed by the FDA to be less effective, compared with heterosexuals. In subsequent iterations of GHWs, we recommend efforts to pretest proposed GHWs among sexual and gender minority individuals. The differences in perceived effectiveness among lesbian and transgender or gender nonconforming persons when compared with their heterosexual counterparts suggests a need to be sensitive not only to sexual orientation, but also to gender as it intersects with sexual orientation. Lesbian and transgender or gender nonconforming persons would be especially important populations to consider during pretesting, given the relatively high prevalence of tobacco use and lower perceived effectiveness when evaluating the current set of GHWs. Other culturally tailored forms of communicating anti-smoking messages may be necessary to reduce smoking rates among sexual and gender minority populations.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements and Funding

This work was conducted with support from the National Cancer Institute’s Lung Cancer Disparities Center grant #P50CA148596 and NIH grant number R25 CA057711. R.H.N. acknowledges support from the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Grant (K12-HD055887) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the National Institute on Aging, administered by the University of Minnesota Deborah E. Powell Center for Women’s Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard University or the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix 1 – Comparison of Perceived Effectiveness of Nine GHWs by Gender and Sexual Orientation Status (n=1168)

| Hole in the throat |

Baby and smoke |

Lungs | Teeth | Stroke | Cartoon baby |

Dead | Crying woman |

I quit man | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | |

| Male heterosexual | 4.05 (1.23) | 3.92 (1.28) | 4.23 (1.13) | 4.27 (1.09) | 4.09 (1.18) | 3.97 (1.30) | 4.05 (1.27) | 3.42 (1.46) | 3.06 (1.48) |

| Female heterosexual | 4.38 (1.07) | 4.36 (1.10) | 4.48 (0.97) | 4.56 (0.87) | 4.45 (1.00) | 4.38 (1.08) | 4.42 (1.03) | 3.79 (1.40) | 3.59 (1.49) |

| Gay | 4.24 (1.16) | 4.00 (1.12) | 4.24 (0.97) | 4.52 (0.71) | 4.56 (0.77) | 3.88 (1.20) | 4.12 (1.17) | 3.44 (1.36) | 3.20 (1.29) |

| Lesbian | 3.82 (1.30) | 3.92 (1.38) | 4.13 (1.38) | 4.21 (1.26) | 4.03 (1.35) | 3.87 (1.45) | 3.95 (1.50) | 3.28 (1.56) | 3.00 (1.56) |

| Male bisexual | 4.00 (1.32) | 4.13 (1.02) | 4.63 (0.62) | 4.88 (0.34) | 4.25 (1.13) | 4.25 (1.06) | 3.81 (1.33) | 3.56 (1.26) | 3.63 (1.59) |

| Female bisexual | 3.98 (1.22) | 3.98 (1.22) | 4.04 (1.26) | 4.20 (1.19) | 4.07 (1.16) | 4.11 (1.10) | 4.13 (0.98) | 3.33 (1.27) | 3.02 (1.29) |

| Transgender or gender non-conforming | 3.40 (1.84) | 3.27 (1.53) | 3.73 (1.62) | 3.4 (1.59) | 3.73 (1.62) | 3.40 (1.8) | 3.73 (1.49) | 3.13 (1.46) | 2.73 (1.67) |

Appendix 2 – Characteristics of Study Participants by Gender and Sexual Orientation in Boston, Lawrence, and Worcester, 2013

| Male heterosexual | Female heterosexual | Gay | Lesbian | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | N | % |

Mean (SD) |

N | % | Mean (SD) | N | % | Mean (SD) | N | % | |

| Age (ranged from 18–70 years) | 30.6 (13.3) | 36.6 (14.5) | 38.0 (17.5) | 30.8 (13.4) | ||||||||

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White | 266 | 50.3 | 148 | 29.7 | 10 | 40.0 | 18 | 46.2 | ||||

| African-American | 170 | 32.1 | 214 | 43.0 | 7 | 28.0 | 13 | 33.3 | ||||

| Other | 93 | 17.6 | 136 | 27.3 | 8 | 32.0 | 8 | 20.5 | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 372 | 70.3 | 261 | 52.4 | 13 | 52.0 | 25 | 64.1 | ||||

| Hispanic | 157 | 29.7 | 237 | 47.6 | 12 | 48.0 | 14 | 35.9 | ||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Some high school | 71 | 13.5 | 86 | 17.5 | 5 | 20.0 | 6 | 15.4 | ||||

| High school/GED | 231 | 44.0 | 171 | 34.8 | 7 | 28.0 | 15 | 38.5 | ||||

| Some college | 167 | 31.8 | 136 | 27.6 | 6 | 24.0 | 6 | 15.4 | ||||

| Associate degree or higher | 56 | 10.7 | 99 | 20.1 | 7 | 28.0 | 12 | 30.8 | ||||

| Smoking Status | ||||||||||||

| Non-smoker | 222 | 42.0 | 254 | 51.6 | 9 | 36.0 | 22 | 56.4 | ||||

| Former | 63 | 11.9 | 64 | 13.0 | 5 | 20.0 | 6 | 15.4 | ||||

| Current | 243 | 46.0 | 174 | 35.4 | 11 | 44.0 | 11 | 28.2 | ||||

| Health Status (scale of 1–5 from poor to excellent) | 3.6 (1.0) | 3.5 (1.0) | 3.5 (1.0) | 3.7 (1.0) | ||||||||

| Male bisexual | Female bisexual | Transgender and other | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | N | % | Mean (SD) | N | % | Mean (SD) | N | % | |

| Age (ranged from 18–70 years) | 30.6 (13.3) | 36.6 (14.5) | 26.6 (11.1) | ||||||

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 266 | 50.3 | 148 | 29.7 | 7 | 46.7 | |||

| African-American | 170 | 32.1 | 214 | 43.0 | 6 | 40.0 | |||

| Other | 93 | 17.6 | 136 | 27.3 | 2 | 13.3 | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 372 | 70.3 | 261 | 52.4 | 11 | 73.3 | |||

| Hispanic | 157 | 29.7 | 237 | 47.6 | 4 | 26.7 | |||

| Education | |||||||||

| Some high school | 71 | 13.5 | 86 | 17.5 | 3 | 21.4 | |||

| High school/GED | 231 | 44.0 | 171 | 34.8 | 5 | 35.7 | |||

| Some college | 167 | 31.8 | 136 | 27.6 | 5 | 35.7 | |||

| Associate degree or higher | 56 | 10.7 | 99 | 20.1 | 1 | 7.1 | |||

| Smoking Status | |||||||||

| Non-smoker | 222 | 42.0 | 254 | 51.6 | 7 | 46.7 | |||

| Former | 63 | 11.9 | 64 | 13.0 | 3 | 20.0 | |||

| Current | 243 | 46.0 | 174 | 35.4 | 5 | 33.3 | |||

| Health Status (scale of 1–5 from poor to excellent) | 3.6 (1.0) | 3.5 (1.0) | 3.7 (0.8) | ||||||

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The university’s institutional review board approved the study.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- Johnson SE, Holder-Hayes E, Tessman GK, et al. Tobacco product use among sexual minority adults: Findings from the 2012–2013 National Adult Tobacco Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:e91–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corliss HL, Wadler BM, Jun H-J, et al. Sexual-orientation disparities in cigarette smoking in a longitudinal cohort study of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:213–222. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cochran SD, Bandiera FC, Mays VM. Sexual orientation–related differences in tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure among us adults aged 20 to 59 years, 2003–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1837–1844. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchting FO, Emory KT, Scout, et al. Transgender Use of Cigarettes, Cigars, and E-Cigarettes in a National Study. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53:e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blosnich JR, Horn K. Associations of discrimination and violence with smoking among emerging adults: differences by gender and sexual orientation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:1284–1295. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blosnich JR, Lee JGL, Horn K. A systematic review of the aetiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities. Tob Control. 2013;22:66–73. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newcomb ME, Heinz AJ, Birkett M, Mustanski B. A longitudinal examination of risk and protective factors for cigarette smoking among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Starks TJ. The influence of structural stigma and rejection sensitivity on young sexual minority men’s daily tobacco and alcohol use. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatzenbuehler ML, Wieringa NF, Keyes KM. Community-level determinants of tobacco use disparities in lesbian, gay, bisexual youth: results from a population-based study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011 doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Lung Association. Smoking out a deadly threat: Tobacco use in the LGBT Community. Washington, D.C.: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JGL, Goldstein AO, Ranney LM, et al. High tobacco use among lesbian, gay, bisexual populations in West Virginian bars and community festivals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:2758–2769. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8072758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith EA, Malone RE. The outing of Philip Morris: advertising tobacco to gay men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:988–993. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.6.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith EA, Offen N, Malone RE. What makes an ad a cigarette ad? Commercial tobacco imagery in the lesbian, gay, bisexual press. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:1086–1091. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.038760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens P, Carlson LM, Hinman JM. An analysis of tobacco industry marketing to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) populations: strategies for mainstream tobacco control and prevention. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5:129S–134S. doi: 10.1177/1524839904264617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Washington HA. Burning love: big tobacco takes aim at LGBT youths. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1086–1095. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.7.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dilley JA, Spigner C, Boysun MJ, et al. Does tobacco industry marketing excessively impact lesbian, gay and bisexual communities? Tob Control. 2008;17:385–390. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.024216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith EA, Thomson K, Offen N, Malone RE. “If you know you exist, it’s just marketing poison”: meanings of tobacco industry targeting in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:996–1003. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.118174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke T, Ward B, Freeman G, Schiller J. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the January-March 2015 National Health Interview Survey. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics; Atlanta, GA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The health consequences of smoking - 50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill S, Amos A, Clifford D, Platt S. Impact of tobacco control interventions on socioeconomic inequalities in smoking: review of the evidence. Tob Control. 2014;23:e89–e97. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Welch V, Tugwell P. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67:190–193. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas S, Fayter D, Misso K, et al. Population tobacco control interventions and their effects on social inequalities in smoking: systematic review. Tob Control. 2008;17:230–237. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.023911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JGL, Matthews AK, McCullen CA, Melvin CL. Promotion of Tobacco Use Cessation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: A Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthews PA, Block AC, Lee JGL, et al. [Accessed 20 Jul 2017];Position Statement: Support Policies to Reduce Smoking Disparities for Gender and Sexual Minorities. 2017 http://www.sbm.org/UserFiles/file/lgbt_smoking_disparities_statement_final.pdf.

- 25.Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control. 2011;20:327–337. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canadian Cancer Society. Cigarette package health warnings: International status report. Fifth. Canada: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noar SM, Hall MG, Francis DB, et al. Pictorial cigarette pack warnings: a meta-analysis of experimental studies. Tob Control. 2016;25:341–354. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brewer NT, Hall MG, Noar SM, et al. Effect of Pictorial Cigarette Pack Warnings on Changes in Smoking Behavior: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:905–912. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Cigarette graphic warnings and the divided federal courts. Tobacco Control Legal Consortium; St Paul, MN: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibson L, Brennan E, Momijan A, et al. Assessing the consequences of implementing graphic warning labels on cigarette packs for tobacco-related health disparities. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:898–907. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cantrell J, Vallone DM, Thrasher JF, et al. Impact of Tobacco-Related Health Warning Labels across Socioeconomic, Race and Ethnic Groups: Results from a Randomized Web-Based Experiment. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e52206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dillard JP, Weber KM, Vail RG. The Relationship Between the Perceived and Actual Effectiveness of Persuasive Messages: A Meta-Analysis With Implications for Formative Campaign Research. J Commun. 2007;57:613–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00360.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bigsby E, Cappella JN, Seitz HH. Efficiently and effectively evaluating public service announcements: additional evidence for the utility of perceived effectiveness. Commun Monogr. 2013;80:1–23. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2012.739706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ackerson LK, Viswanath K. The social context of interpersonal communication and health. J Health Commun. 2009;14:5–17. doi: 10.1080/10810730902806836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kontos EZ, Viswanath K. Cancer-related direct-to-consumer advertising: a critical review. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:142–150. doi: 10.1038/nrc2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viswanath K, Ramanadhan S, Kontos EZ. Macrosocial Determinants Popul. Health. Springer; New York: 2007. Mass media; pp. 275–294. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grier SA, Kumanyika S. Targeted marketing and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:349–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sierra JJ, Hyman MR, Heiser RS. A review of ethnic identity in advertising. Wiley Int. Encycl. Mark 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollay RW, Lee JS, Carter-Whitney D. Separate, but not equal: racial segmentation in cigarette advertising. J Advert. 1992;21:45–57. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1992.10673359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schooler C, Basil MD, Altman DG. Alcohol and cigarette advertising on billboards: targeting with social cues. Health Commun. 1996;8:109–129. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc0802_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knobloch-Westerwick S, Appiah O, Alter S. News selection patterns as a function of race: the discerning minority and the indiscriminating majority. Media Psychol. 2008;11:400–417. doi: 10.1080/15213260802178542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matthews AK, Balsam K, Hotton A, et al. Awareness of media-based antitobacco messages among a community sample of LGBT individuals. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15:857–866. doi: 10.1177/1524839914533343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: building a foundation for better understanding. National Academies Press (US); Washington (DC): 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oakenfull G. Effects of gay identity, gender and explicitness of advertising imagery on gay responses to advertising. J Homosex. 2007;53:49–69. doi: 10.1080/00918360802101278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bigman CA, Nagler RH, Viswanath K. Representation, exemplification, and risk: Resonance of tobacco graphic health warnings across diverse populations. Health Commun. 2016;31:974–987. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2015.1026430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hammond D, Thrasher J, Reid JL, et al. Perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings among Mexican youth and adults: a population-level intervention with potential to reduce tobacco-related inequities. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:57–67. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9902-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, et al. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2005–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1205–1211. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kowitt SD, Noar SM, Ranney LM, Goldstein AO. Public attitudes toward larger cigarette pack warnings: Results from a nationally representative U.S. sample. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0171496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fallin A, Goodin AJ, King BA. Menthol Cigarette Smoking among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Adults. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fallin A, Goodin A, Lee YO, Bennett K. Smoking characteristics among lesbian, gay, bisexual adults. Prev Med. 2015;74:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burkhalter JE, Warren B, Shuk E, et al. Intention to quit smoking among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:1312–1320. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahalik JR, Burns SM, Syzdek M. Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men’s health behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:2201–2209. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thrasher JF, Arillo-Santillán E, Villalobos V, et al. Can pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages address smoking-related health disparities? Field experiments in Mexico to assess pictorial warning label content. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:69–80. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9899-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mead EL, Cohen JE, Kennedy CE, et al. The role of theory-driven graphic warning labels in motivation to quit: a qualitative study on perceptions from low-income, urban smokers. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:92. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1438-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fallin A, Neilands TB, Jordan JW, et al. Wreaking “havoc” on smoking. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:S78–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fallin A, Neilands TB, Jordan JW, Ling PM. Social branding to decrease lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young adult smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:983–989. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ling PM, Lee YO, Hong J, et al. Social branding to decrease smoking among young adults in bars. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:751–760. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ortiz KS, Duncan DT, Blosnich JR, et al. Smoking among sexual minorities: are there racial differences? Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:1362–1368. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Factor R, Williams DR, Kawachi I. Social resistance framework for understanding high-risk behavior among nondominant minorities: preliminary evidence. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:2245–2251. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]