Abstract

Purpose

Some patients with diffuse interstitial lung disease (ILD) undergo bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy (TBB) as part of their diagnostic evaluation. It is unclear what the incidence and risk factors for pneumothorax (PTX) following TBB are in this patient population.

Methods

Ninety-seven subjects with pulmonary fibrosis who underwent a research bronchoscopy with TBB as part of the multicenter Correlating Outcomes with Biochemical Markers to Estimate Time-progression in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (COMET) trial were retrospectively reviewed. We compared subjects who developed a PTX during research bronchoscopy with TBB versus those who did not.

Results

Seven patients (7.2%) experienced a PTX during research bronchoscopy with TBB. Subjects who experienced PTX during TBB had significantly lower DLCO percent predicted (29 ± 8 versus 45 ± 15, P=0.006) and had lower resting room air saturation of peripheral oxygen (SPO2) on 6-minute walk testing (91±10 versus 95±3, P=0.02). No differences between groups were found with respect to age, gender, race, BMI, HRCT characteristics, or number of transbronchial biopsies performed.

Conclusion

The incidence of PTX following research bronchoscopy with TBB in patients with pulmonary fibrosis was found to be 7.2% in this study. Patients who developed a pneumothorax had greater impairments in gas exchange at baseline evidenced by a lower DLCO % predicted and a lower resting room air SPO2 when compared to subjects without PTX as a complication.

Keywords: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, pneumothorax, risk factors, transbronchial biopsy

Background

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive, fibrotic lung disorder in which patients present with an insidious onset of dyspnea and nonproductive cough [1–3]. The disease pathogenesis involves an inappropriate increase in fibroblast proliferation and collagen formation leading to a reduction in functional lung tissue [4,5]. Characteristic high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) findings in IPF include reticular opacities in a peripheral and basal distribution, honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and minimal ground glass attenuation [1,2]. In subjects without a definite UIP pattern on HRCT diagnostic uncertainly often exists leading to further investigation.

Bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and transbronchial biopsy (TBB) is frequently performed during the diagnostic evaluation of patients with nonspecific interstitial lung abnormalities on chest imaging. This is frequently performed to exclude other diseases such as infection, sarcoidosis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis, among others, since the amount of tissue obtained by TBB is generally insufficient to make a diagnosis of IPF [1,2]. In addition, bronchoscopy with BAL and TBB is frequently performed for research purposes.

The incidence of pneumothorax (PTX) from bronchoscopy with TBB ranges from 1–6% in the medical literature [10–33,36]. Little is known about the safety of bronchoscopy with TBB in patients with diffuse interstitial lung diseases, such as pulmonary fibrosis. Prior work has suggested that IPF patients may be at an increased risk of complications related to bronchoscopy and TBB [12], but no studies have focused solely on patients with pulmonary fibrosis. The purpose of our study is to define the incidence and risk factors of developing a pneumothorax after TBB in a well characterized cohort of patients with pulmonary fibrosis.

Methods

Study Design

This study was performed using data from the National Institutes of Health supported COMET (Correlating Outcomes with Biochemical Markers to Estimate Time-Progression in IPF) trial, a prospective multicenter clinical trial that was completed in August 2012. In the first phase, baseline specimens of biologically plausible biomarkers of disease activity were taken from multiple body compartments (blood, BAL, TBB, surgical lung biopsy) in patients with either suspected or recently diagnosed (within the past 48 months) IPF. If the diagnosis was suspected, it was confirmed during this phase as well (supplementary appendix S1). During the second phase, subjects were followed for up to 80 weeks or until they met any part of a composite endpoint (death, acute exacerbation of IPF, relative decline in forced vital capacity of at least 10% or DLCO of 15%). The aim of this trial was to determine if any biomarkers that were previously collected could be used to predict subsequent disease course. The study protocol was approved by each of the participating institutional research ethics committees, and informed consent was obtained from all participants (further information provided in supplementary appendix S4).

In the COMET trial, a total of 97 subjects underwent bronchoscopy with BAL and TBB as part of the research protocol. These cases were retrospectively reviewed for demographic data, pulmonary function testing, HRCT, long-term oxygen therapy, research bronchoscopy results, and surgical lung biopsy results (if performed). Predicted values for each patient’s forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were calculated using formulas derived from NHANES III data while predicted values for diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO) were derived from equations based on Crapo and others data [8,9]. We compared subjects who had a PTX as a serious adverse event during bronchoscopy with TBB versus those who did not develop a PTX. Follow-up pulmonary function testing was reviewed on those subjects who had a pneumothorax during TBB.

Patients

Patients were enrolled from nine different clinical centers in the United States. Inclusion criteria for participation in the study were subjects between 35 and 80 years of age with a suspected or confirmed diagnosis of IPF within the last 48 months. Major exclusion criteria were the following: collagen vascular disease, an environmental exposure as the probable etiology ILD, and evidence of an active infection at screening (a full list of exclusion criteria for the COMET trial is included in supplementary appendix S1).

High-Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT)

HRCT images were centrally reviewed by a diagnostic radiologist with expertise in chest radiology. HRCT was assessed for the presence or absence of: reticular abnormality, honeycombing, extensive ground glass abnormality (defined as extent of ground glass > extent of reticular abnormality), profuse micronodules, mosaic attenuation/lobular air trapping (bilateral, in ≥ 3 lobes), consolidation, and emphysema. The ATS/ERS criteria for evaluating HRCT for usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern were followed.

Bronchoscopy with BAL and TBB

Bronchoscopy was performed in stable individuals after providing informed consent and reviewing medical history, allergies, and current medications. The procedural technique varied between study centers based on the local physician’s practice and protocol. BAL was performed in the most affected lung, in either the lingula or right middle lobe. Four 50 mL aliquots of normal saline were used for the BAL. Following BAL, up to twelve TBB samples were obtained from multiple segments within the same lung as the BAL. TBB was performed under fluoroscopy to avoid biopsies at the pleural margin. Biopsies were stopped prior to collection of all specimens if the subject showed signs of clinical instability, oxygen desaturation, or if significant bleeding occurred. All subjects had a post-procedure upright portable chest x-ray to evaluate for pneumothorax. Full details of the research bronchoscopy protocol are included in the supplementary appendix S3.

Analysis and Statistics

Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation or percentage of patients as appropriate. Continuous data was analyzed using Student’s t-test and discrete data was analyzed using the Fisher’s exact test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Odds ratios were calculated with logistic regression using STATA software. All other data analysis was performed using SAS software.

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Patient Population

Nine of the 97 subjects (7.2%) from the COMET trial developed a pneumothorax as a complication from a research bronchoscopy with TBB. Overall, the study population had a mean age of 64±8 years and the majority of subjects were male (74%) and Caucasian (94%). There was a non-significant trend towards greater smoking history in the study group that developed a pneumothorax compared to the no PTX group (100% versus 67.8%, P=0.10). No statistically significant differences were noted with regards to age, gender, race, or BMI between the two study groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Transbronchial Biopsy Data

| Baseline Characteristic | Pneumothorax (N=7) |

No Pneumothorax (N=90) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64±7 | 64±8 | 0.89 |

| Male – no. (%) | 5 (71.4%) | 67 (74.4%) | 1.00 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 31.3±4.1 | 31.2±4.4 | 0.95 |

| Ever Smoker – no. (%) | 7 (100%) | 61 (67.8%) | 0.10 |

| Home Oxygen Therapy – no. (%) | 5 (71.4%) | 39 (43.3%) | 0.24 |

| Caucasian – no. (%): | 7 (100%) | 84 (93.3%) | 1.00 |

| Pulmonary Function Test: | |||

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 63±19 (n=7) | 74±18 (n=81) | 0.10 |

| FVC (% predicted) | 55±17 | 68±17 | 0.06 |

| DLCO (% predicted) | 29±8 | 45±15 | 0.006 |

| Six Minute Walk Test: | |||

| Resting Room Air SpO2 (%) | 91±10 (n=6) | 95±3 (n=73) | 0.02 |

| Walk Distance (m) | 229±161 | 345±131 | 0.06 |

| HRCT: | |||

| Definite UIP pattern – no. (%) | 3 (60%) (n=5) | 34 (42.5%) (n=80) | 0.65 |

| Possible UIP – no. (%) | 2 (40%) | 40 (50%) | 1.00 |

| Inconsistent with UIP – no. (%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (7.5%) | 1.00 |

| Presence of Emphysema– no. (%) | 1 (20%) | 9 (11.3%) | 0.47 |

| Presence of Honeycombing – no. (%) | 3 (60%) | 48 (60%) | 1.00 |

| TBB Specimens Collected | 8±3 | 7±2 | 0.55 |

Data is presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified

DLCO, diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1s; FVC, forced vital capacity; HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography; TBB, transbronchial biopsy; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Baseline spirometry, DLCO, six minute walk test (6MWT), and HRCT data for the respective study groups are shown in Table 1. While no statistically significant differences on spirometry were noted between study groups, the PTX group had a trend towards lower baseline FVC % predicted (55±17 versus 68±17, P=0.06). Patients in the PTX group had a significantly lower baseline DLCO % predicted (29±8 versus 45±15, P=0.006). Additionally, subjects in the PTX group had a lower resting room air saturation of peripheral oxygen (SPO2) compared to the no PTX group (91±10 versus 95±3, P=0.02). There was a non-significant trend towards lower baseline six minute walk distances in the PTX group compared to the no PTX group (229±161 versus 345±131, P=0.06).

On HRCT a definite UIP pattern was identified in 46.3% of subjects (60% in PTX group, 42.5% in no PTX group). The remaining subjects had a HRCT classified as either possible UIP or inconsistent with UIP. 60% of subjects in both study groups had honeycombing on HRCT. No significant differences between study groups were found with respect to UIP pattern, presence of emphysema, or presence of honeycombing between the study groups (Table 1).

There was no significant difference in the number of TBB performed in the group that experienced a PTX versus the group that did not (Table 1). The seven cases of PTX occurred at five out of the nine centers. No significant difference in the rate of pneumothorax was found for the respective study centers.

Risk Factors Associated with Pneumothorax

We performed a multivariate logistic regression analysis to evaluate for clinical characteristics associated with pneumothorax following bronchoscopy with TBB. On univariate analysis a lower baseline DLCO % predicted was the only identifiable risk factor for developing iatrogenic PTX following TBB (Table 2). DLCO % predicted, however, was no longer statistically significant after multivariate analysis (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.83–1.00, P=0.07).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis for association of pneumothorax after transbronchial biopsies with selected variables.

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| DLCO (% predicted) | 0.90 (0.83–0.98) | 0.012 | 0.92 (0.83–1.00) | 0.07 |

| FVC (% predicted) | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) | 0.07 | 0.97 (0.91–1.04) | 0.45 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | 0.89 | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 0.79 |

| TBB # Samples | 1.10 (0.81–1.49) | 0.54 | 0.96 (0.68–1.34) | 0.81 |

CI, confidence interval; DLCO, diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide; FVC, forced vital capacity; OR, odds ratio; SPO2, room air saturation of peripheral oxygen; TBB, transbronchial biopsy.

Home oxygen therapy and resting room air SPO2 were excluded from the multivariate model due to their strong correlation with DLCO.

Follow-up after Pneumothorax

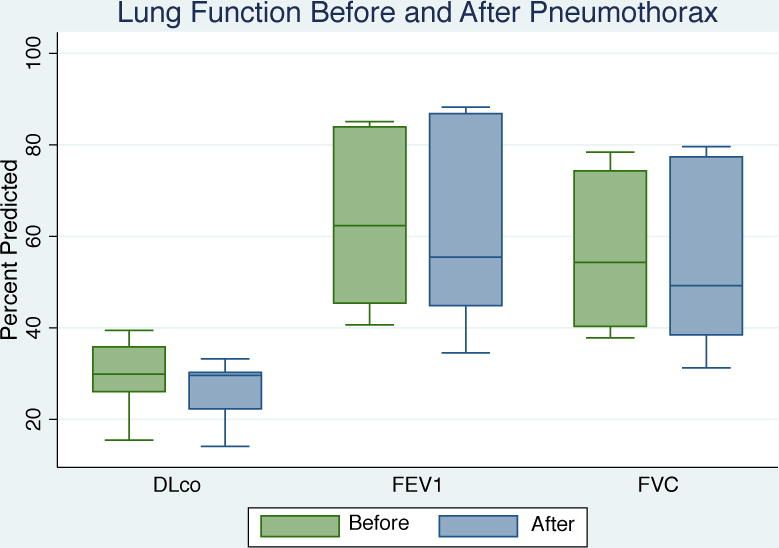

Five of the seven subjects who experienced a pneumothorax required chest tube drainage. The PTX resolved within one day in 6 of the 7 patients. The remaining subject required 27 days for full PTX resolution. Six of the seven subjects had follow-up spirometry and DLCO measurements between 13 and 34 days from pneumothorax occurrence. No statistically significant changes were noted in FEV1, FVC, or DLCO % predicted on follow-up testing (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Follow-up pulmonary function testing in subjects with iatrogenic pneumothorax following transbronchial biopsies.

No significant difference was observed in FEV1, FVC, or DLCO on follow-up pulmonary function testing in pulmonary fibrosis subjects who developed pneumothorax following research bronchoscopy.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the risk of pneumothorax associated with TBB in patients exclusively with pulmonary fibrosis. We found that 7.2% of pulmonary fibrosis patients developed a pneumothorax after undergoing research bronchoscopy with TBB as part of the COMET trial. Patients who developed a pneumothorax had both a lower DLCO at baseline and a lower resting room air SPO2 when compared to those without PTX as a complication. These results suggest that in pulmonary fibrosis those with poorer gas exchange are at an elevated risk for PTX during bronchoscopy with TBB.

Pneumothorax rates following bronchoscopy with TBB vary from 1–6% in the literature, with most studies reporting PTX in <4% of cases [10–33] (Table 3). In our study we found a higher incidence rate of pneumothorax following TBB at 7.2%. Data pertaining to specific risk factors for developing PTX from TBB is sparse. Operator experience is expected to influence the risk with more experienced physicians presumed to have fewer complications. However, a study of 350 cases showed that operator experience had no predictive value for development of pneumothorax [10]. Additionally, fluoroscopy use has not been shown to affect the risk [11–15]. In our multicenter study, operator inexperience was not a limitation as subjects underwent research bronchoscopy with TBB under fluoroscopy at large academic centers with significant experience in performing bronchoscopy with TBB. The rate of pneumothorax with TBB did not significantly differ among the nine centers in our study, further minimizing the chance that operator error contributed to the PTX complication rate.

Table 3.

Number of Biopsy Samples Collected and Rate of Pneumothorax Experienced in Prior Investigations

| Reference | Number of Subjects | Number of TBB Samples | Pneumothorax Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitchell et al.21 | 433 | 6–10 | 0.01% |

| Frazier et al.22 | 305 | 1–8 (mean 5) | 0.7% |

| Ahmad et al.24 | 148 | 2–5 | 0.7% |

| Ellis20 | 107 | mean 3.4 | 0.9% |

| Hernandez Blasco et al.18 | 169 | 1–12 (mean 6±2) | 1.2% |

| Puar et al.11 | 67 | ≥ 3 | 1.5% |

| Cazzadori et al.34 | 142 | 3–6 (mean 4) | 2.2% |

| Koonitz et al.31 | 42 | 3–11 | 2.4% |

| Joyner et al.12 | 37 | 4–5 | 2.7% |

| Izbicki et al.10 | 350 | 1–7 (majority had 4–5) | 2.9% |

| de Fenoyl et al.13 | 174 | 1–5 | 3.4% |

| Pue et al.3 | 173 | 3–5 | 4.0% |

| Jain et al.30 | 104 | 1–6 | 4% |

| Kopp et al.32 | 40 | 5 | 5% |

| Milman et al.16 | 405 | 3–10 | 5.8% |

| Sindhwani et al.*37 | 49 | 6–8 | 10.2% |

Data is presented as number or percent where appropriate.

TBB, transbronchial biopsy; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

All subjects in this study had diffuse parenchymal lung disease on chest imaging, but lacked a definite UIP pattern on HRCT.

There is conflicting evidence whether the total number of biopsies during TBB augments PTX risk [10,16,17]. A study by Milman and others looked at 1144 consecutive patients, of which 405 had 3–10 TBB performed during 452 procedures [16]. No relationship was found between the number of TBB and the incidence of pneumothorax. Another study by Izbicki and others assessed 350 consecutive patients who underwent bronchoscopy with TBB (majority had 4–5 specimens obtained) for various lung pathologies and showed the risk of PTX to be 2.9% [10]. In contrast, the latter study showed a weak but statistically significant correlation between the risk of PTX and the number of biopsy specimens obtained (r = 0.14, p = 0.008) [10]. In our study, the number of biopsies was similar between subjects who developed PTX versus those who did not.

Previous studies describing iatrogenic PTX from bronchoscopy with TBB have reported a wide range of total biopsies performed [3,10–13,16,18,20–22,24,30–32,34]. A study by Hernandez Blasco and others assessed 169 immunocompetent outpatients with various pulmonary diagnoses who underwent bronchoscopy with TBB [18]. The mean number of samples obtained through TBB was 6 ± 2. Pneumothorax occurred in only two patients (1.2%), well within the usual range [18]. In our study there was no significant difference in total number of biopsies performed between those who experienced a PTX versus those who did not. Additionally, the number of TBB performed was not identified as an independent risk factor for PTX on multivariate logistic regression in our study.

Most studies investigating bronchoscopy with TBB have included patients with various lung pathologies, both localized and diffuse. Many of these trials have enrolled a varying number of patients with pulmonary fibrosis; however, no previous trial focused solely on these patients. One study evaluated 172 patients who underwent bronchoscopy with TBB, of which 18% were ultimately diagnosed with IPF [19]. A non-significant increase in complications including PTX was found in IPF patients compared with other pulmonary diseases. Among all patients, those that were older and who had greater diminishment in lung function (as assessed by FEV1) had more complications including PTX during TBB [19]. In our study we found that those with poorer gas exchange (lower DLCO and lower resting room air SPO2) were more likely to develop PTX on TBB, but in contrast we did not find an association with FEV1 or age.

The current evidence to date is limited regarding the risk of PTX during TBB with specific type of lung pathology. Risk is increased in bullous disease and in patients receiving positive pressure ventilation [22]. Among all spontaneously breathing patients undergoing bronchoscopy with TBB, the reported risk of pneumothorax ranges from 1–6% (Table 2) [3,10–33]. In a study by Sindhwani and others transbronchial biopsies were performed only in patients with diffuse parenchymal lung disease (without a definite UIP pattern) on CT scan [37]. This study reported a 10% incidence of iatrogenic PTX following TBB, which is higher than previously reported rates for all spontaneously breathing subjects undergoing the procedure. Similarly our study comprised solely of subjects with pulmonary fibrosis found a 7.2% rate of pneumothorax following TBB, also comparatively higher to historical ranges. The proposed mechanism for the greater occurrence of pneumothorax in patients with pulmonary fibrosis may be related to the presence of fibrosis in the lung parenchyma and the resultant increase in tensile forces that occurs in these patients during biopsies performed with forceps.

One limitation of our study is the small sample size (97 subjects), and as a result the number of subjects who developed the complication of interest (a pneumothorax) was only seven subjects. This small sample size limits the strength of our results for identifiable risk factors for pneumothorax with multivariate logistic regression (as evidenced by no variables showing statistical significance). Another limitation of the study is the homogeneity of the patient population comprised mostly of subjects who were Caucasian and male. This is to be expected in a study comprised solely of subjects with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, but it does limit the generalizability of the results. A third limitation of our study is that pertinent baseline data was missing in some subjects: 12 (12.4%) did not have a HRCT, and 9 (9.3%) did not have baseline spirometry available for review. Additionally, given this study’s retrospective nature there is a possibility for disequilibrium between the two groups not captured by the variables studied. Strengths of this trial include its multicenter design, the standardized research protocol for performing bronchoscopy and TBB at the research centers, and the strict criteria utilized to confirm a diagnosis of IPF for inclusion in the COMET trial.

In conclusion, 7.2% of subjects with pulmonary fibrosis developed a pneumothorax following research bronchoscopy and TBB. This is the first trial to date that has focused on the risk of PTX from TBB in subjects exclusively with pulmonary fibrosis. Subjects who developed a pneumothorax had greater impairments in gas exchange at baseline evidenced by a lower DLCO % predicted and a lower resting room air SPO2 when compared to subjects without PTX as a complication. In patients who experienced a pneumothorax no significant decline in pulmonary function occurred on follow-up testing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant 1RC2HL101740-01).

Abbreviations

- 6MWT

Six Minute Walk Test

- BAL

Bronchoalveolar Lavage

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- COMET

Correlating Outcomes with Biochemical Markers to Estimate Time-progression in IPF

- COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- DLCO

Diffusion Capacity of Carbon Monoxide

- FEV1

Forced Expiratory Volume in First Second

- FVC

Forced Vital Capacity

- HRCT

High-Resolution Computed Tomography

- ILD

Interstitial Lung Disease

- IPF

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- SPO2

Saturation of peripheral oxygen

- PTX

Pneumothorax

- TBB

Transbronchial Biopsy

- UIP

Usual Interstitial Pneumonia

Footnotes

ORCID ID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4433-2632

Clinical Trials.gov number: NCT01071707

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author’s Contributions:

Dr. Galli and Dr. Panetta contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and revision of the manuscript. Dr. Gaeckle performed statistical analysis, interpretation of data, and figure rendering. Dr. Criner served as the guarantor of the paper, contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approval of the final manuscript. Dr. Martinez, Dr. Bethany Moore, Dr. Thomas Moore, Dr. Courey, and Dr. Flaherty contributed to study concept and design, and analysis and interpretation of the data.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Mar 15;183(6):788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society. American thoracic Society/European respiratory society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Jan 15;165(2):277–304. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pue CA, Pacht ER. Complications of fiberoptic bronchoscopy at a university hospital. Chest. 1995 Feb;107(2):430–2. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.2.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selman M, King TE, Pardo A, American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, American College of Chest Physicians Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Jan 16;134(2):136–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costabel U, King TE. International consensus statement on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2001 Feb;17(2):163–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17201630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wall CP, Gaensler EA, Carrington CB, Hayes JA. Comparison of transbronchial and open biopsies in chronic infiltrative lung diseases. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981 Mar;123(3):280–5. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.123.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunninghake GW, Zimmerman MB, Schwartz DA, King TE, Jr, Lynch J, Hegele R, et al. Utility of a lung biopsy for the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Jul 15;164(2):193–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.2.2101090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Jan 1;159(1):179–87. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crapo RO, Morris AH. Standardized single breath normal values for carbon monoxide diffusing capacity. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981 Feb;123(2):185–9. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.123.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izbicki G, Shitrit D, Yarmolovsky A, Bendayan D, Miller G, Fink G, et al. Is routine chest radiography after transbronchial biopsy necessary?: A prospective study of 350 cases. Chest. 2006 Jun;129(6):1561–4. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puar HS, Young RC, Jr, Armstrong EM. Bronchial and transbronchial lung biopsy without fluoroscopy in sarcoidosis. Chest. 1985 Mar;87(3):303–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.87.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joyner LR, Scheinhorn DJ. Transbronchial forceps lung biopsy through the fiberoptic bronchoscope: Diagnosis of diffuse pulmonary disease. Chest. 1975 May;67(5):532–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.67.5.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Fenoyl O, Capron F, Lebeau B, Rochemaure J. Transbronchial biopsy without fluoroscopy: A five year experience in outpatients. Thorax. 1989 Nov;44(11):956–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.44.11.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rittirak W, Sompradeekul S. Diagnostic yield of fluoroscopy-guided transbronchial lung biopsy in non-endobronchial lung lesion. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007 Nov;90(Suppl 2):68–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anders GT, Johnson JE, Bush BA, Matthews JI. Transbronchial biopsy without fluoroscopy. A seven-year perspective. Chest. 1988 Sep;94(3):557–60. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milman N, Faurschou P, Munch EP, Grode G. Transbronchial lung biopsy through the fibre optic bronchoscope. Results and complications in 452 examinations. Respir Med. 1994 Nov;88(10):749–53. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(05)80197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herf SM, Suratt PM. Complications of transbronchial lung biopsies. Chest. 1978 May;73(5 Suppl):759–60. doi: 10.1378/chest.73.5_supplement.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez Blasco L, Sanchez Hernandez IM, Villena Garrido V, de Miguel Poch E, Nunez Delgado M, Alfaro Abreu J. Safety of the transbronchial biopsy in outpatients. Chest. 1991 Mar;99(3):562–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernandez Borge J, Alfageme Michavila I, Munoz Mendez J, Villagomez Cerrato R, Campos Rodriguez F, Pena Grinan N. Factors related to diagnostic yield and complications of transbronchial biopsy. Arch Bronconeumol. 1998 Mar;34(3):133–41. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2896(15)30470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis JH., Jr Transbronchial lung biopsy via the fiberoptic bronchoscope. Experience with 107 consecutive cases and comparison with bronchial brushing. Chest. 1975 Oct;68(4):524–32. doi: 10.1378/chest.68.4.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell DM, Emerson CJ, Collins JV, Stableforth DE. Transbronchial lung biopsy with the fibreoptic bronchoscope: Analysis of results in 433 patients. Br J Dis Chest. 1981 Jul;75(3):258–62. doi: 10.1016/0007-0971(81)90003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frazier WD, Pope TL, Jr, Findley LJ. Pneumothorax following transbronchial biopsy. low diagnostic yield with routine chest roentgenograms. Chest. 1990 Mar;97(3):539–40. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.3.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinha S, Guleria R, Pande JN, Pandey RM. Bronchoscopy in adults at a tertiary care centre: Indications and complications. J Indian Med Assoc. 2004 Mar;102(3):152,4, 156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad M, Livingston DR, Golish JA, Mehta AC, Wiedemann HP. The safety of outpatient transbronchial biopsy. Chest. 1986 Sep;90(3):403–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.90.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ulmeanu R, Mihaltan F, Crisan E, Alexe M, Grigore P, Andreescu I, et al. Practical issues of transbronchial lung biopsy (TLB) in pneumology. Pneumologia. 2007 Apr-Jun;56(2):59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanson RR, Zavala DC, Rhodes ML, Keim LW, Smith JD. Transbronchial biopsy via flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope; results in 164 patients. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976 Jul;114(1):67–72. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.114.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alzeer AH, Al-Otair HA, Al-Hajjaj MS. Yield and complications of flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy in a teaching hospital. Saudi Med J. 2008 Jan;29(1):55–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark RA, Gray PB, Townshend RH, Howard P. Transbronchial lung biopsy: A review of 85 cases. Thorax. 1977 Oct;32(5):546–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.32.5.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pereira W, Jr, Kovnat DM, Snider GL. A prospective cooperative study of complications following flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Chest. 1978 Jun;73(6):813–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.73.6.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain P, Sandur S, Meli Y, Arroliga AC, Stoller JK, Mehta AC. Role of flexible bronchoscopy in immunocompromised patients with lung infiltrates. Chest. 2004 Feb;125(2):712–22. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koonitz CH, Joyner LR, Nelson RA. Transbronchial lung biopsy via the fiberoptic bronchoscope in sarcoidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1976 Jul;85(1):64–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-1-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kopp C, Perruchoud A, Heitz M, Dalquen P, Herzog H. Transbronchial lung biopsy in sarcoidosis. Klin Wochenschr. 1983 May 2;61(9):451–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02664332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen W, Ji C, Li Y, Xu D. Diagnostic value of transbronchial lung biopsy in diffuse or peripheral lung lesions. Hua Xi Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 1990 Sep;21(3):330–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cazzadori A, Di Perri G, Todeschini G, Luzzati R, Boschiero L, Perona G, et al. Transbronchial biopsy in the diagnosis of pulmonary infiltrates in immunocompromised patients. Chest. 1995 Jan;107(1):101–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Descombes E, Gardiol D, Leuenberger P. Transbronchial lung biopsy: an analysis of 530 cases with reference to the number of samples. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 1997;52:324–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boskovic T, Stojanovic M, Stanic J, et al. Pneumothorax after transbronchial needle biopsy. Thorac Dis. 2014;6:427–34. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.08.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sindhwani G, Shirazi N, Sodhi R, et al. Transbronchial lung biopsy in patients with diffuse parenchymal lung disease without ‘idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis pattern’ on HRCT scan- Experience from a tertiary care center of North India. Lung India. 2015;32:453–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.164148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.