Abstract

Purpose

Cigarette smoking in the perinatal period is associated with costly morbidity and mortality for mother and infant, yet many women continue to smoke throughout their pregnancy and following delivery. This report describes tobacco use prevalence among perinatal smokers identified through an “opt-out” inpatient smoking cessation clinical service.

Description

Adult women admitted to the peripartum, delivery, and postpartum units at a large academic hospital were screened for tobacco use. Smokers were identified through their medical record and referred to a bedside consult and follow-up using an interactive voice response (IVR) system to assess smoking up to 30 days post-discharge.

Assessment

Between February 2014 and March 2016, 533 (10%) current and 898 (16%) former smokers were identified out of 5649 women admitted to the perinatal units. Current smokers reported an average of 11 cigarettes per day for approximately 12 years. Only 10% reported having made a quit attempt in the past year. The majority of smokers (56%) were visited by a bedside tobacco cessation counselor during their stay and 27% were contacted through the IVR system. Those counselled in the hospital were twice as likely (RR=1.98, CI=1.04–3.78) to be abstinent from smoking using intent-to-treat analysis at any time during the 30 days post-discharge.

Conclusions

This opt-out service reached a highly nicotine-dependent perinatal population, many of whom were receptive to the service, and it appeared to improve abstinence rates postdischarge. Opt-out tobacco cessation services may have a significant impact on the health outcomes of this population and their children.

Keywords: tobacco, nicotine, cessation, perinatal, pregnancy, opt-out, hospital

Introduction

Tobacco use during the perinatal period is associated with significant and costly morbidity and mortality for both mother and infant. In addition to poor birth outcomes associated with tobacco use (Hammoud et al., 2005; Herrmann, King, & Weitzman, 2008; Salihu & Wilson, 2007; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004), continued tobacco use after delivery and environmental smoke exposure are associated with a number of adverse effects on children, including, greater risk of developing asthma, behavioral problems, mental health problems, middle ear disease, respiratory infections, metabolic syndrome and greater likely of becoming a smoker in adulthood (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006; Herrmann et al., 2008; U.S. Department of Health Human Services, 2014; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2007; Zhou et al., 2014). Women are more likely to quit smoking during pregnancy than any other time in their lives (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2001), yet estimates reveal that 8-12% continue to smoke during their pregnancy (Curtin & Matthews, 2016; Dietz et al., 2010; Tong et al., 2013).

While pregnant women are recognized as an important group to target for smoking cessation interventions, abstinence remains a challenge prior to and following delivery. Efficacious interventions for pregnant women exist (Chamberlain et al., 2013; Fiore, Jaen, Baker, & et al., 2008; Hartmann-Boyce, Stead, Cahill, & Lancaster, 2014; Lumley et al., 2009), yet many do not receive tobacco cessation treatments during and/or after their pregnancy (Dempsey et al., 2015; Tran, Rosenberg, & Carlson, 2010). Though tobacco screening in prenatal care is generally high, additional cessation support or interventions for smoking are not being reliably administered (Bailey & Jones Cole, 2009; Jordan, Dake, & Price, 2006). Previous studies have recommended incorporating interventions into routine clinical care (Fang et al., 2004; Secker-Walker et al., 1995) to promote cessation, but most health care settings have struggled to make this a reality.

In 2012, the Joint Commission implemented tobacco performance measures to address tobacco screening and treatment as part of medical care (The Joint Commission, 2011). Integrating tobacco cessation into standard clinical practice through “opt-out” assessment and referral programs is one way to ensure that these services are built into the provision of care for perinatal smokers. In opt-out programs, all patients receive services as part of routine standard of care unless they indicate refusal of services. Opt-out tobacco cessation work conducted with pregnant smokers has been done in the United Kingdom (UK) and has found that, 1) women were accepting of an opt-out system to obtain cessation support (Sloan et al., 2016), 2) in a pre-post evaluation of an opt-out system, results showed improved rates of setting quit dates and reported cessation among smokers identified by biochemical verification (Campbell, Cooper, et al., 2016), and 3) staff were generally supportive of opt-out tobacco systems in antenatal clinics (Campbell, Bowker, et al., 2016). These findings, while promising, may not apply in the United States (US) given differences in medical systems and support for perinatal women. Thus, studies evaluating opt-out tobacco cessation programs for pregnant women in the US are needed.

Within a major academic medical center in the southeastern US, a comprehensive opt-out tobacco treatment service for inpatients was launched in February 2014. Through this clinical program, all admitted patients are screened for tobacco use and current tobacco users are referred automatically for cessation support while in the hospital and enrolled in a follow-up phone-based system. Data collected from this service presents a unique opportunity to investigate the reach and impact of this program amongst a population of perinatal smokers. This paper describes the prevalence and characteristics of tobacco use among perinatal patients, the overall reach rates of the opt-out tobacco cessation program, and self-reported smoking cessation outcomes assessed within 30 days post-discharge.

Methods

This opt-out program was implemented within a major academic medical center in the southeastern US. This hospital is the only tertiary/quaternary care referral center in the state (4.8 million people) and is located in a mid-sized metropolitan area. The opt-out tobacco treatment inpatient service involves three steps; 1) Screening: all patients are asked about tobacco use at admission and all tobacco users are automatically referred to a tobacco treatment specialist (TTS) through the electronic medical record (EMR), 2) Referral/Inpatient Counseling: the TTS conducts bedside cessation counseling (involves psychosocial education, motivational enhancement, skills-based training, and relapse prevention) when possible based on patient availability and the caseload for that day and recommends treatment options to be acted upon by the medical care team, and 3) Follow-Up: all tobacco users are automatically enrolled in an interactive voice response (IVR) system, which prospectively follows up with patients for 30 days after discharge. This system has been described in further detail elsewhere (reference not included due to blinding of manuscript).

Inpatient records were examined from February 2014 until March 2016 for women (18 years or older) admitted to the labor and delivery and/or postpartum care units. To ensure appropriate selection of the target sample the following inclusion/exclusion criteria were implemented. First, patients with multiple admissions were only counted once. Second, in rare instances, patients were admitted to labor/delivery units that were beyond typical child-bearing age (most likely due to bed unavailability on other units). Any admission where the patient was over 41 years of age was inspected and excluded if not pregnancy-related. This research was conducted in accord with prevailing ethical principles and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the author’s institution.

The following data elements were collected: age, race, ethnicity, primary language, insurance status, length of hospital stay, and smoking status (current, former, or never smoker). Demographics were back-filled from the EMR and were not consistently available for all records. The following measures were collected as part of bedside counseling with the TTS; smoking status, frequency, history, quit attempts, motivation to quit, confidence and readiness to quit, and pharmacotherapy recommendations (from the TTS). The IVR post-discharge system contacted enrolled patients at 3, 14, and 30 days post-discharge. Information was collected on smoking status, frequency, quit attempts, motivation to quit, use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and whether the patient wanted to be transferred to the quitline.

Frequency and proportions of patient demographics and smoking characteristics were reported for categorical variables while means and standard deviations were reported for continuously-measured variables. Statistical analyses were conducted on the following outcome measures obtained via the IVR system; reach rate of the IRV system (reached at least once during the 30-day post-charge period), smoking abstinence (yes/no based on the last known status reported during a follow-up call or considered smoking if patient was not reached), use of NRT (yes/no), and transfer to the quitline (yes/no). Risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for all follow-up outcome measures. An intent-to-treat analysis was applied to the abstinence outcome such that patients who were not reached at follow-up were considered to be smoking, allowing for a conservative estimate of quitting. Outcome measures were compared between those who received bedside counselling and IVR versus those who received IVR only. Given low rates of NRT use and quitline transfer, statistical outcomes should be interpreted cautiously. All statistical analyses were done in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

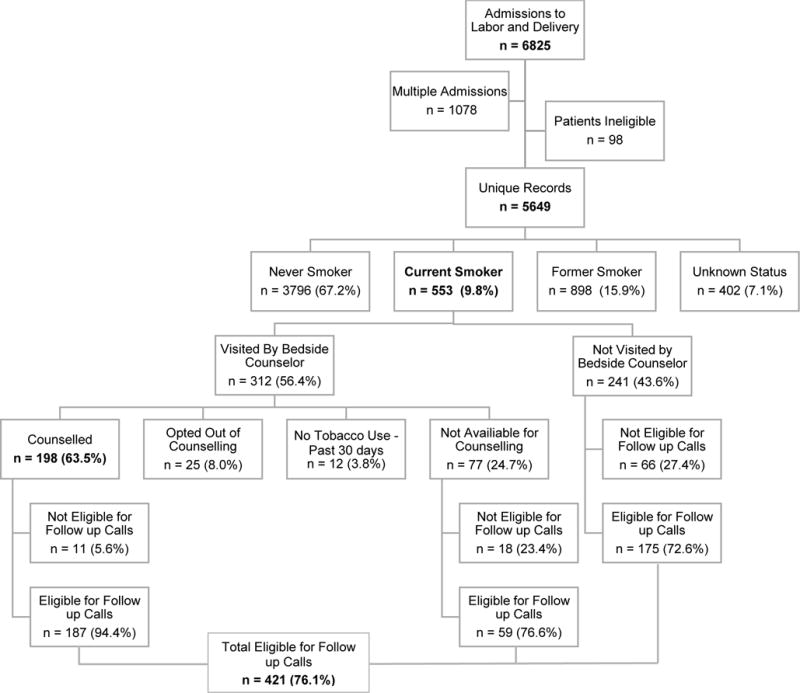

Patient distributions within the opt-out system are shown in Figure 1. Among the 5649 women screened at the time of admission to the perinatal units, 10% (n=553) reported current use of tobacco and 16% (n=898) reported being former smokers. Over half of current smokers identified through the EMR were visited by a TTS (56%; n=312). Among eligible patients, 64% (198/312) accepted the bedside consult. A total of 12 patients who were visited denied smoking in the past 30 days. The remainder of the patients were either not available at the time of consult (n=77) or refused (opted-out) of the bedside consult (n=25). Just under half of current smokers (44%; n=241) were discharged from the hospital before the consult could be arranged. A total of 421 women were deemed eligible to receive follow-up calls after discharge. Reasons for ineligibility for follow-up calls included; not providing a phone number, not having a valid phone number, or being discharged to a location other than home.

Figure 1.

Number of perinatal patients being screened, counseled, and enrolled in postdischarge follow-up phone calls from February 2014 until March 2016 for women admitted to Labor and Delivery in the hospital.

Available demographic data are shown in Table 1. The average age of perinatal inpatients included in this analysis was 29 years and the average duration of hospitalization was 3 days. Approximately 40% of the admitted women were African American, 43% Caucasian, and 2% Hispanic/Latino. The majority of women (89%) reported English as their primary language and the most common form of insurance was Medicaid (49%).

Table 1.

Available demographic information for patients admitted to the labor and delivery units. Note the varying numbers of records that contribute to each item.

| Demographics | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (n=5649) | 28.72 (± 5.7) |

| Length of Stay (n=3406) | 2.73 (±2.6) |

| N (%) | |

| Race (n=2650) | |

| Black | 1068 (40.3%) |

| White | 1147 (43.3%) |

| Other | 435 (16.4%) |

| Ethnicity (n=2663) | |

| Hispanic | 316 (11.9%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 2347 (88.1%) |

| Primary Language (n=5649) | |

| English | 5003 (88.6%) |

| Other | 646 (11.4%) |

| Insurance Status (n=2398) | |

| Medicare | 24 (1.0%) |

| Medicaid | 1186 (49.5%) |

| Commercial | 914 (38.1%) |

| Uninsured | 274 (11.4%) |

Among the 198 women who accepted the bedside consult, the average years of smoking was 12 and average number of cigarettes smoked per day was 11 (Table 2). Ninety-two percent (n=145) reported being daily smokers before hospital admission, 84% (n=122) reported smoking within five minutes of waking, and 75% (n=136) reported living with another smoker. Only 10% (n=19) reported making a quit attempt in the past year. Despite the low rate of reported quit attempts, 37% (n=70) of women reported moderate to high intention to quit after discharge and 20% (n=38) reported moderate to high confidence to quit. Despite their high nicotine dependence, less than half (43%; n=72) of the women reported strong cigarette cravings since admission. Of those reporting cravings, 81.2% (n=56) expressed interested in nicotine replacement therapy.

Table 2.

Tobacco characteristics of patients interviewed and counselled by a bedside tobacco treatment specialist during their inpatient stay (n = 198). Note the varying numbers of records that contribute to the data of the individual interview items. Percentages represent responses among patients who were asked that particular question.

| Demographic and Smoking Characteristics | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (n=198) | 28.21 (± 5.4) |

| Age started Smoking (n=182) | 16.60 (± 4.4) |

| Years of Smoking (n=182) | 11.58 (± 5.8) |

| Number of Cigarettes Smoked Per Day (n=157) | 11.33 (± 7.8) |

| N (%) | |

| Daily Smoker Before Admission (n=157) | 145 (92.4%) |

| Smoking Within 5 Minutes of Waking (n=145) | 122 (84.1%) |

| Other Smokers in Home (n=181) | 136 (75.1%) |

| At least one Quit Attempt (over 24 Hours) in the Past Year (n = 198) | 19 (9.6%) |

| Intention to Quit Tobacco After Discharge (1–5 scale with 1=no intention, 5=strong intention) (n = 188) | 1: 18 (9.6%) 2: 32 (17.0%) 3: 68 (36.2%) 4: 22 (11.7%) 5: 48 (25.5%) |

| Confidence in Ability to Quit Tobacco After Discharge (1–5 scale with 1=not confident, 5=very confident) (n = 188) | 1: 26 (13.9%) 2: 63 (33.5%) 3: 61 (32.4%) 4: 23 (12.2%) 5: 15 (8.0%) |

| Experienced Strong Cravings to Smoking since Admission (n = 167) | 72 (43.1%) |

| If Yes to Cravings, Expressed Interest in Receiving Nicotine Replacement During Stay (n = 69) | 56 (81.2%) |

| Counselor Provided Self Help Guide (n=177) | 162 (91.5%) |

| Counselor Discussed Pharmacotherapy Option (n=177) | 158 (89.3%) |

| Medication Recommended While in Hospital (n=198) | Patch: 38 (19.2%) Gum: 2 (1.0%) Lozenge: 23 (11.6%) Combo NRT: 21 (10.6%) Chantix/Varenicline: 1 (0.5%) Multiple options: 6 (3.0%) No recommendations: 107 (54%) |

| Medication Recommended Before Discharge (n=198) | Patch: 32 (16.2%) Gum: 2 (1.0%) Lozenge: 26 (13.1%) Combo NRT: 35 (17.7%) Chantix/Varenicline: 1 (0.5%) No recommendations: 102 (51.5%) |

| Readiness to Quit Stage (determined by beside counselor); (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983) (n = 167) | Maintenance: 5 (3.0%) Ready: 30 (18.0%) Preparation: 93 (55.7%) Contemplation: 24 (14.4%) Pre-Contemplation: 15 (9.0%) |

Of the women who were visited by a TTS and eligible for follow-up (n=187), 65 were reached by phone at least one time within a month after discharge. Among those who did not receive a bedside consult while hospitalized and eligible for follow-up (n=234), 83 were reached by phone. Of those, 33 denied being smokers at the time of hospital admission and were excluded from the follow-up system and analyses. Comparisons between the bedside counseling and IVR group versus the IVR only group are shown in Table 3. Using an intent-to-treat (ITT) method, abstinence was higher (RR=1.98, 95% CI; 1.04–3.78) among those who received a bedside consult. Among those reached by phone and included in analyses (n=115), NRT use was low and no differences were found between women who received a bedside consult compared to those who had not received a consult (10/65 in the bedside counseling and IVR group and 2/50 in the IVR only group). Among those same patients, 14 requested a transfer to the quitline (7/65 in the bedside counseling and IVR and 7/50 in the IVR only group). This comparison also did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

Reach rate, abstinence from smoking, nicotine replacement use and transfer to a tobacco state quitline for patients who received bedside counseling and IVR follow-up phone calls versus IVR follow-up only.

| Bedside + IVR | IVR Only | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reached within 1-Month Post-Discharge (of those eligible to receive calls) | 65/187 = 35.5% | 83/234 = 35.5% | 0.99 (0.77–1.29) |

| Abstinence within 1-Month Applying Intent-To-Treat (of those eligible for follow-up)*† | 24/187 = 12.8% | 13/201 = 6.5% | 1.98 (1.04–3.78) |

| Use of NRT (among those who were reached)* | 10/65 = 15.4% | 2/50 = 4.0% | 3.85 (0.88–16.77) |

| Transfer to the quitline (among those who were reached)* | 7/65 = 10.8% | 7/50 = 14.0% | 0.77 (0.29–2.05) |

RR: Risk Ratio

CI: Confidence Interval

Excluding 33 false positives (defined as those individuals identified by EMR as smokers who upon phone follow-up denied that they had been a smoker at the time of hospitalization) identified during follow-up calls among the IVR only group

Last known smoking status

Discussion

This real-world, hospital-based, opt-out tobacco assessment and cessation program was able to reach 198 perinatal smokers during their inpatient stay and another 83 patients not seen at the bedside by phone after discharge, yielding an overall reach rate of 67% (281/421). Of the women screened for tobacco use, 10% were current smokers. This is consistent with prevalence figures reported in the literature (Curtin & Matthews, 2016; Dietz et al., 2010; Tong et al., 2013). Overall receptivity to the bedside consult was high; only 8% of women visited by the TTS opted-out of the consult. Among women who were counselled at the bedside, 37% reported a moderate to strong intention to quit smoking after discharge, but many lacked confidence in their ability to quit. This suggests that women are motivated to quit smoking after delivery; however, more should be done to support their quitting efforts after discharge in an effort to reduce environmental smoke exposure in newborns and prevent the detrimental effects of prenatal smoking in future pregnancies.

Follow-up data indicate that women who received bedside counseling during their inpatient stay exhibited greater abstinence compared to women who were not seen by a TTS, though most women had returned to smoking within one month after discharge (90% based on an ITT analysis). While the response to follow-up calls was only 35%, the women referred to this service represent a difficult-to-treat population and some may not have ever contacted tobacco cessation resources during their prenatal care. Even modest program reach rates could have a significant impact on public health and cost savings within the hospital system for both mother and infant. Given the volume of admissions, the brief hospital stay for most women, and the chaotic nature of the inpatient stay (i.e., visitors, childcare, consults, etc.); the rate of counselor contact with current smokers is impressive. The inpatient stay represents a critical moment that should be capitalized on to deliver cessation services, provide resources including pharmacotherapy, and potentially engage partners and family members in tobacco cessation as well. Additionally, this automatic referral system does not place added burden on healthcare staff, who are already balancing high caseloads and competing demands on their time.

While this opt-out tobacco cessation service reached an important patient population, there are several areas of need that are illuminated from the current analysis. First, women who report being former smokers at admission are not referred to this program. It is likely that many of these women quit smoking during pregnancy and are at risk of relapsing during the postpartum period. Among the 15-60% of smokers who quit during pregnancy (Ershoff, Solomon, & Dolan-Mullen, 2000; Morasco, Dornelas, Fischer, Oncken, & Lando, 2006), the majority of these women (50–70%) resumed smoking 2–3 months postpartum (Johnson, Ratner, Bottorff, Hall, & Dahinten, 2000; Kahn, Certain, & Whitaker, 2002; Mullen, Richardson, Quinn, & Ershoff, 1997; O’Campo, Faden, Brown, & Gielen, 1992; Severson, Andrews, Lichtenstein, Wall, & Akers, 1997). While former smokers should be included in this program, that would require additional staff time and resources, which remains a considerable challenge.

Second, smoking is likely under-reported among perinatal patients at the time of admission. Biochemical testing for nicotine has shown that smoking rates for pregnant women are potentially underestimated by up to 25% (Shipton et al., 2009). In the current sample, 8% (45/553) of women seen either at the bedside or reached by phone claimed that the medical records had misclassified them as current smokers. While some misclassification is possible, it is also possible that these women were under-reporting their tobacco use. To combat potential under-reporting, the implementation of biochemical verification to identify smokers and enroll them in opt-out cessation services may be necessary to expand reach. In the UK, studies have found that routine biochemical verification of smoking has been met favorably (Campbell, Cooper, et al., 2016; Sloan et al., 2016), suggesting that it could be an acceptable routine practice in the US.

Third, reach rates during the inpatient stay and through follow-up calls could be improved. Special attention should be paid to those who opt-out of services or do not answer follow-up phone calls. One study examining the predictors of opting-out of this program for the general inpatient population demonstrated that being male, being younger, having Medicaid or no insurance, and not having received a bedside consult was associated with either opting-out of counseling or failure to make contact post-discharge through the follow-up system (reference not included due to blinding of manuscript).

This study has several limitations. First, this is an evaluation of a clinical tobacco cessation hospital service, and as such, data were not collected necessarily for research purposes, bedside consults and interviews were not standardized, and there was missing data from the EMR. Second, post-discharge abstinence outcomes are self-reported and no biochemical confirmation of abstinence was collected. Third, given missing demographic information, it cannot be ensured that the analyzed sample was representative of the perinatal population of the hospital generally. However, this clinical service is applied to all inpatients, without any selection criteria, and therefore we have no reason to expect that our sample would be biased or fail to represent the patient population.

Despite high quit rates during pregnancy, 8–12% of women continue to smoke during pregnancy and following delivery, highlighting a critical need to address smoking late in gestation or at delivery while reducing burden, time, training requirements, and cost. The opt-out tobacco screening and cessation program described here reached a highly nicotine-dependent perinatal population, many of whom were receptive to the service, and it appeared to improve abstinence rates post-discharge. To our knowledge, this is first demonstration of an opt-out inpatient tobacco cessation program among perinatal women in the US. This system is contributing to the goal of changing the default system of tobacco treatment (Richter & Ellerbeck, 2015), which currently requires patients to actively seek out and engage in tobacco cessation. However, results are preliminary, and additional program features of higher intensity may be required. Moving forward, future research should address how to improve the reach and impact of interventions designed for women late in gestation or after delivery. Inpatient stays might be the first time that women are offered cessation resources and this opportunity should be taken among this population. Opt-out tobacco cessation services are a potentially pragmatic solution to promote abstinence that may have a significant impact on the health outcomes of a perinatal population and their children.

Significance.

What is already known on this subject?

Cigarette smoking among perinatal women is a significant public health concern with costly consequences for mother and infant. Despite this, many women do not receive cessation support and continue to smoke during pregnancy and following delivery.

What this study adds?

This study describes the reach and impact of an “opt-out” inpatient tobacco cessation clinical service implemented in an academic medical center among perinatal patients. This is the first evaluation of an opt-out clinical program for perinatal women within the United States. Ten percent of perinatal women admitted were current smokers and postdischarge assessment suggests greater abstinence rates among those counseled about quitting during their inpatient stay.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the tobacco treatment specialists for their tireless work as part of the Tobacco Cessation Service in the hospital. The authors would also like to thank TelASK Technologies, Inc., who developed and maintain the IVR follow-up system. Funding for this service was provided by the hospital system (not named due to blinding). Effort for this analysis was supported in part by NIDA grants K01 DA036739, K23 DA039318, and R25 DA020537. The funding sources had no role other than financial support.

One author (not named due to blinding) has received grant funding from the Pfizer, Inc., to study the impact of a hospital based tobacco cessation intervention. He also receives funding as an expert witness in litigation filed against the tobacco industry.

Footnotes

Contributors. All authors contributed to the design and execution of this study, analyses of data, and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bailey BA, Jones Cole LK. Are obstetricians following best-practice guidelines for addressing pregnancy smoking? Results from northeast Tennessee. Southern Medical Journal. 2009;102(9):894–899. doi: 10.1097/smj.0b013e3181aa579c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KA, Bowker KA, Naughton F, Sloan M, Cooper S, Coleman T. Antenatal Clinic and Stop Smoking Services Staff Views on “Opt-Out” Referrals for Smoking Cessation in Pregnancy: A Framework Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(10) doi: 10.3390/ijerph13101004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KA, Cooper S, Fahy SJ, Bowker K, Leonardi-Bee J, McEwen A, Coleman T. ‘Opt-out’ referrals after identifying pregnant smokers using exhaled air carbon monoxide: impact on engagement with smoking cessation support. Tobacco Control. 2016 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) 2006. Report retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain C, O’Mara-Eves A, Oliver S, Caird JR, Perlen SM, Eades SJ, Thomas J. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):Cd001055. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Smoking Prevalence and Cessation Before and During Pregnancy: Data From the Birth Certificate, 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2016;65(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey J, Regan S, Drehmer JE, Finch S, Hipple B, Klein JD, Winickoff JP. Black versus white differences in rates of addressing parental tobacco use in the pediatric setting. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz PM, England LJ, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Tong VT, Farr SL, Callaghan WM. Infant morbidity and mortality attributable to prenatal smoking in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ershoff DH, Solomon LJ, Dolan-Mullen P. Predictors of intentions to stop smoking early in prenatal care. Tobacco Control. 2000;9(Suppl 3):III41–45. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang WL, Goldstein AO, Butzen AY, Hartsock SA, Hartmann KE, Helton M, Lohr JA. Smoking cessation in pregnancy: a review of postpartum relapse prevention strategies. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2004;17(4):264–275. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.4.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update Clinical Practice Guidlines. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hammoud AO, Bujold E, Sorokin Y, Schild C, Krapp M, Baumann P. Smoking in pregnancy revisited: findings from a large population-based study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;192(6):1856–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.057. discussion 1862-1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann-Boyce J, Stead LF, Cahill K, Lancaster T. Efficacy of interventions to combat tobacco addiction: Cochrane update of 2013 reviews. Addiction. 2014;109(9):1414–1425. doi: 10.1111/add.12633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann M, King K, Weitzman M. Prenatal tobacco smoke and postnatal secondhand smoke exposure and child neurodevelopment. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2008;20(2):184–190. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282f56165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Ratner PA, Bottorff JL, Hall W, Dahinten S. Preventing smoking relapse in postpartum women. Nursing Research. 2000;49(1):44–52. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200001000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan TR, Dake JR, Price JH. Best practices for smoking cessation in pregnancy: do obstetrician/gynecologists use them in practice? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15(4):400–441. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RS, Certain L, Whitaker RC. A reexamination of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(11):1801–1808. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumley J, Chamberlain C, Dowswell T, Oliver S, Oakley L, Watson L. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):Cd001055. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasco BJ, Dornelas EA, Fischer EH, Oncken C, Lando HA. Spontaneous smoking cessation during pregnancy among ethnic minority women: a preliminary investigation. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(2):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen PD, Richardson MA, Quinn VP, Ershoff DH. Postpartum return to smoking: who is at risk and when. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1997;11(5):323–330. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.5.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Campo P, Faden RR, Brown H, Gielen AC. The impact of pregnancy on women’s prenatal and postpartum smoking behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1992;8(1):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter KP, Ellerbeck EF. It’s time to change the default for tobacco treatment. Addiction. 2015;110(3):381–386. doi: 10.1111/add.12734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salihu HM, Wilson RE. Epidemiology of prenatal smoking and perinatal outcomes. Early Human Development. 2007;83(11):713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secker-Walker RH, Solomon LJ, Flynn BS, Skelly JM, Lepage SS, Goodwin GD, Mead PB. Smoking relapse prevention counseling during prenatal and early postnatal care. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1995;11(2):86–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson HH, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Wall M, Akers L. Reducing maternal smoking and relapse: long-term evaluation of a pediatric intervention. Preventive Medicine. 1997;26(1):120–130. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.9983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipton D, Tappin DM, Vadiveloo T, Crossley JA, Aitken DA, Chalmers J. Reliability of self reported smoking status by pregnant women for estimating smoking prevalence: a retrospective, cross sectional study. BMJ. 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan M, Campbell KA, Bowker K, Coleman T, Cooper S, Brafman-Price B, Naughton F. Pregnant Women’s Experiences and Views on an “Opt-Out” Referral Pathway to Specialist Smoking Cessation Support: A Qualitative Evaluation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. Tobacco Treatment Core Measures. 2011 Retrieved from https://www.jointcommission.org/core_measure_sets.aspx.

- Tong VT, Dietz PM, Morrow B, D’Angelo DV, Farr SL, Rockhill KM, England LJ. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy–Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 sites, 2000–2010. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 2013;62(6):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran ST, Rosenberg KD, Carlson NE. Racial/ethnic disparities in the receipt of smoking cessation interventions during prenatal care. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(6):901–909. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking 2004 Surgeon General’s Report. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2004. Reports of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health Human Services. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): 2014. The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Women and Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta GA: Office on Smoking and Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: 2007. Children and Secondhand Smoke Exposure. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Rosenthal DG, Sherman S, Zelikoff J, Gordon T, Weitzman M. Physical, behavioral, and cognitive effects of prenatal tobacco and postnatal secondhand smoke exposure. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2014;44(8):219–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]