Abstract

Estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) is a multifunctional nuclear receptor that mediates the actions of estrogenic compounds. Despite its well defined role in mediating the actions of estrogens, a substantial body of evidence demonstrates that ERβ has broad range of physiological functions that are independent of those normally attributed to estrogen signaling. These functions can, in part, be achieved by the activity of several alternatively spliced isoforms that have been identified for ERβ. This short review will describe structural differences between the ERβ splice variants that are known to be translated into proteins. Moreover, we discuss how these alternative structures contribute to functional differences in the context of both healthy and pathological conditions. This review also describes the principal factors that regulate alternative RNA splicing. The alternatively spliced isoforms of ERβ are differentially expressed according to brain region, age, and hormonal milieu underscoring the likelihood that there are precise cell-specific mechanisms that regulate ERβ alternative splicing. However, despite these correlative data, the molecular factors regulating alternative ERβ splicing in the brain remain unknown. Here, we review the basic mechanisms that regulate alternative RNA splicing and use that framework to make logical predictions about ERβ alternative splicing in the brain.

INTRODUCTION

Aging represents a continuous spectrum of phenotypic and behavioral changes that are ultimately driven by inefficient cellular functioning that contributes to increased cell damage over time. Detrimental changes in cellular function include telomere shortening, increased missense/nonsense mutations, translational errors, and organelle dysfunction, all of which can result in protein dysfunction and the accumulation of cytotoxic protein aggregates. Concurrent with these age-related abnormalities is an increased incidence of global alternative RNA splicing (1). Alternative RNA splicing is heralded as a means of expanding the cellular proteome beyond the constraints of strict genetic coding. As such, it is widely considered to be both beneficial and detrimental depending on the structural and functional aspects of the alternatively expressed isoforms. In young healthy tissues, it is likely that one dominant isoform is expressed (2), despite the availability of the molecular machinery required to achieve the expression of multiple isoforms. However, human studies demonstrate that aging increases the incidence of alternative splicing independent of disease, thereby increasing the abundance of alternatively spliced isoforms that are expressed in a variety of tissues. One of the highest rates of alternative splicing events occurs in the brain, and increased expression of alternatively spliced isoforms can contribute to age-related deficits in many neurobiological processes (1, 3–5)

Menopause is a unique biological process in women that is concurrent with aging. A physiological hallmark of menopause is the sharp decline in circulating levels of 17β-estradiol (E2), the primary circulating gonadal estrogen in reproductive age women. The rapid decline of E2 at menopause further complicates the natural aspects of aging, as E2 is key for the maintenance of healthy organs and tissues in young women. The beneficial actions of E2 on various organs are achieved through the high affinity binding of E2 to its cognate receptors: estrogen receptor (ER)α (NR3A1/ESR1) and ERβ (NR3A2/ESR2), which function as both transcription factors and mediators of intracellular signaling cascades (6–8). Over the past decade, many alternatively spliced transcripts for ERα and ERβ have been identified using RNA deep sequencing platforms, but few have been shown to translate into functional protein products (9–13). Notably, several of these translated alternatively spliced isoforms appear to have constitutive transcriptional activity and function largely independent of ligand (i.e. E2) binding (14–17). Further, the concurrent age-related increase in global alternative splicing events provides a molecular framework to allow for the increased expression of these variants during this critical life transition. This intriguing hypothesis suggests that alternatively spliced forms of ER may be more biologically relevant post-menopause, whereas the dominant isoform may be more active during times of high circulating estrogen (18, 19).

This review will focus on the structure, function, and regulation of validated ERβ splice variants in humans and rodents. ERβ was originally cloned in 1996, and since then has been characterized as mediating many of the non-reproductive actions of E2. For example, ERβ may function alone or in concert with other estrogen receptors (ERα and GPR30) to carry out the numerous cardio- and neuroprotective effects of E2. Moreover, ERβ is expressed in a wide range of brain regions and does not exhibit global alterations in expression through aging. However, its expression has been found to be significantly decreased in some brain regions, independent of E2 deprivation (20, 21). Additionally, ERβ subcellular localization may be altered during aging (22), which could impact the efficacy of canonical ERβ signaling pathways. Together, these distinctions from ERα make ERβ, and its splice variants, an attractive candidate for therapeutic strategies aimed at alleviating negative symptoms associated with decreased circulating E2 and improving cognitive function in post-menopausal women.

ERβ: BASIC STRUCTURAL ORGANIZATION

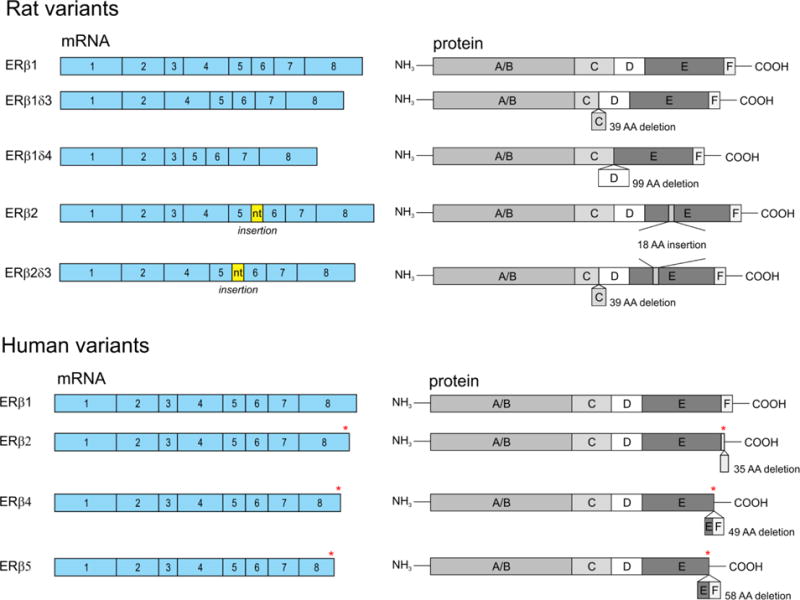

Estrogen receptors are classified as ligand-activated transcription factors belonging to a large superfamily of nuclear receptors (23, 24). The two primary receptors, ERα and ERβ are encoded by distinct genes, and the mature transcripts contain 8 exons. Similar to other receptors belonging to the nuclear receptor superfamily, the ERβ protein is composed of 6 functional domains denoted by letters A-F extending from the N- to C- terminus of the protein (Fig. 1) (25–27).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of ERβ splice variants.

Rat (top) and human (bottom) ERβ isoforms including the coding exons and corresponding proteins domains of rat and human ERβ splice variants. The asterisk in exon 8 of the human variants denotes regions of amino acid sequence variation between the isoforms.

The N-terminal A/B domain contains the activation function-1 (AF-1) region, characterized by its cooperativity in ligand dependent transcriptional activation and its synergistic interactions with the C-terminal ligand binding domain (LBD) (28). Post-translational modifications in the AF-1 region of both ERs can also initiate ligand independent transcription through the recruitment of select co-regulatory proteins (29). An important distinction for ERβ is the apparent inhibitory effects of the AF-1 domain on its transcriptional activity. For instance, experimental deletions of the ERβ AF-1 region increased dimerization and subsequent transcriptional activity, suggesting that specific amino acid residues in this region are critical for keeping the receptor transcriptionally inactive (30).

Next, the C domain is the most highly conserved region among all members of the nuclear receptor family and contains the residues responsible for recognizing specific DNA enhancer regions, such as estrogen response elements (EREs). Stable DNA binding is achieved by the coordinated interactions of two perpendicular α-helices (6). The first helix contains the residues responsible for DNA recognition and is situated between two zinc finger motifs, which are composed of 8 cysteine residues surrounding two zinc ions. The second helix is generally thought to confer stability to the complex, binding non-specifically to the DNA backbone and thereby allowing the temporal resolution necessary for the recruitment of additional co-regulatory proteins and basal transcriptional machinery. Notably, ERβ has been shown to interact with DNA through a wide variety of mechanisms that are not limited to the presence of canonical EREs or direct DNA binding, for example by tethering to other basic transcription factors (31–33). In both humans and rats, the DNA-binding domains (DBD) of ERα and ERβ show over 95% sequence homology. Therefore, it is not surprising that ERα and ERβ can form functional heterodimers (34), and recent in silico modeling demonstrated that the heterodimer is more stable than the ERβ homodimer (35).

The D domain is a flexible hinge region that provides a functional link between the DBD and the LBD. This region harbors the nuclear localization signal, which, upon ligand binding, allows the receptor to translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus where it can interact with DNA. The hinge region is the least characterized portion of ERβ and is highly variable among members of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Therefore, some studies suggest this region is multifunctional, yet highly specific to individual receptor subtypes, and possibly confers cell-type specific functions (36).

The E domain, or ligand binding domain (LBD), has been the most thoroughly characterized, both functionally and structurally, for all nuclear receptors. This domain is comprised of 12 α-helices that together form a ligand binding pocket and, upon ligand binding, expose a co-regulatory protein binding surface. The orientation of helix 12 is critical to the conformation ERs adopt once bound to ligand, and ultimately influence the ability of the receptor to bind other proteins and activate gene transcription. Helix 12 contains the core residues of the activator function-2 (AF-2) domain, a short amphipathic conserved alpha-helix that interacts with coregulatory proteins through an LxxLL motif. The LBD domain shares only 55% sequence homology between ERα and ERβ, which has enabled the development of selective estrogen receptor agonists and antagonists.

Finally, at the C-terminal end of the receptor lies a short F domain whose function has been largely uncharacterized for ERβ and has almost no sequence homology with ERα (37, 38). This domain is typically truncated or absent in the human ERβ splice variants studied to date, making its functional properties particularly relevant, as described more fully in the next section. The highly defined functional domains of ERβ underscore the importance of each domain in facilitating estrogens’ actions in a given cell or tissue. Alternative splicing results in the altered structure of one or more of these domains, making it reasonable to predict that the ERβ splice variants could have distinct interacting protein partners and perhaps even target genes that are not traditionally ascribed as being estrogen-regulated.

ERβ SPLICE VARIANTS

Shortly after the discovery of ERβ, several alternatively spliced ERβ variants were identified in both humans and rodents (39–43). Although the human and rodent ERβ splice variants differ in structure, they demonstrate remarkably similar functions. Most notably, many of the variants appear to have constitutive, or ligand independent, actions on downstream target genes. The biological consequences of this constitutive activity are predictably different for various tissue types, yet our understanding of the biological function for many of these variants is still in its infancy.

Rodent splice variants

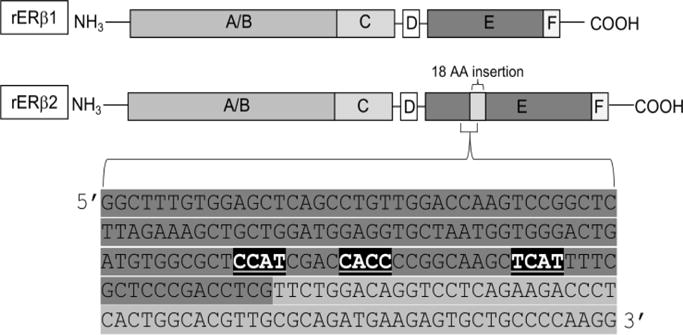

To date, there have been 5 experimentally validated functional ERβ splice variants in rodents. From this point on, the dominant isoform will be referred to as ERβ1. The first variant discovered in rodents was the rat ERβ2 splice variant (rERβ2). This variant contains an in-frame insertion of 54 nucleotides between exons 5 and 6, which results in a novel 18 amino acid sequence the ligand binding domain (39, 42, 44). The origin of these extra nucleotides was initially unclear; however, we have predicted that these extra nucleotides represent an alternative exon based on the presence of upstream binding motifs for the neuronal specific RNA binding protein Nova1 (neuro-oncological ventral antigen 1; Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Nova-1 consensus sequences located in exon 5 of rat ERβ.

The full-length rat ERβ sequence was analyzed for RNA binding protein sites using RBPmap (http://rbpmap.technion.ac.il/index.html). Nova1 YCAY consensus sites are highlighted (black boxes, white text) in ERβ exon 5 (highlighted in dark gray). The downstream 54bp ERβ2 insert is shown in the light gray box. Scores assigned to Nova1-binding probabilities must be greater than 0.895 (out of 1.00) based on weighted rank in order to be detected.

The elongated LBD of rERβ2 results in decreased binding affinity for E2 and many other estrogenic compounds, such as xenoestrogens and phytoestrogens, compared to rERβ1. Because of this decreased affinity for ligand, rERβ2 seems have primarily ligand independent activity in most cell types. For example, reporter assays in hippocampal-derived HT-22 cells demonstrated that rERβ2 exhibits ligand independent activation of ERE-driven promoters and repression of AP-1-driven promoters; these effects are only modestly enhanced by the addition of E2 (17). These reporter assays demonstrated that, compared to rERβ1, the ligand independent action of rERβ2 at both ERE and AP-1 promoters is lower, but rERβ1 exhibits a much larger response to ligand than rERβ2 (38). Furthermore, the observed differences in transcriptional activity were not due to changes in DNA binding affinity, but could be explained by the inability of rERβ2 to recruit specific steroid receptor coactivators and/or differential posttranslational modifications of the splice variants (14, 17). These data provided useful mechanistic information that detailed the differential transcriptional potential of ERβ splice variants at discrete regulatory elements; however, most endogenous gene promoters are highly complex and contain multiple regulatory regions that function in concert. Studies using more complex promoters, such as arginine vasopressin (AVP), demonstrated that rERβ2 robustly induced AVP transcriptional activity in the presence of E2 and 3βAdiol, a metabolite of the potent androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT) (45). These results suggest that rERβ2 can act equivalently to ERβ1 to regulate complex gene promoters, despite its lower ligand binding affinity, but this is likely dependent on cell type and the presence of other co-regulatory factors. Similarly, the rERβ2 LBD structure does not appear to affect its binding affinity for the ER antagonist 4-OH-tamoxifen, a phenomenon which could also be cell-type specific (42).

Next, it was discovered that exon 3 may be deleted from either rERβ1 or rERβ2, removing 39 amino acids that would normally encode the second zinc finger of the DNA-binding domain; these variants are referred to as rERβ1δ3 and rERβ2δ3, respectively (42). These are analogous to some ERα variants, which also lack exon 3 and therefore, a portion of its DBD. The lack of a second zinc finger in the DBD results in an unstable association with EREs on gene promoters, thereby reducing or eliminating any transcriptional activation (42). However, these variants can still tether to other DNA-bound transcription factors to elicit a physiological response, such as activation of AP-1-mediated promoter activity in the presence of E2. This contrasts with rERβ1 and rERβ2, as they both repress AP-1-mediated promoter activity except in the presence of tamoxifen (33, 46). Notably, rERβ1δ3 does not show any ligand independent or ligand dependent activity in neuronal cell lines at the rat AVP promoter, which contains a combination of AP-1 and ERE motifs (45). The δ3 variants also organize into highly punctate subnuclear domains in response to E2 in a manner that is distinct from that of rERβ1 or rERβ2 (46). Moreover, rERβδ3 variants colocalized with the nuclear receptor coactivator GRIP-1 in these same subnuclear punctate domains (46), suggesting that rERβ1δ3 and rERβ2δ3 are functionally responsive to ligand through their interactions with coregulatory proteins, despite an inability to bind DNA.

Finally, exon 4 (99 amino acids) may be deleted from rERβ1, yielding a splice variant known as rERβ1δ4, resulting in deletion of the D domain of the protein (43). This variant lacks the ability to localize to the nucleus, consistent with the deletion occurring in the nuclear localization sequence of the hinge region. Somewhat surprisingly, rERβ1δ4 also lacks the ability to bind E2, which indicates the hinge region is important for conferring a conformational structure that is favorable for creating a stable ligand binding pocket (43). Overall, rERβ1 δ4 is expressed at very low levels in most brain regions tested with the exception of the hippocampus (43). The relatively high expression of rERβ1δ4 in the hippocampus suggests that it may play a role in memory formation or other functions regulated by the hippocampus, but these proposed functions have not been validated experimentally, as rERβ1δ4 remains the least well-studied of all the rodent ERβ splice variants.

Human ERβ splice variants

To date, there have been 5 experimentally validated functional human ERβ isoforms termed hERβ1-hERβ5. The splicing of hERβ3 appears to be under special regulatory control, because its expression is restricted to the testes (41). Therefore, its functional properties are less studied and will not be further discussed in this review. Unlike rat ERβ splice variants which include insertions and deletions throughout the middle regions of the protein, human ERβ splice variants arise from the specific alternative splicing of exon 8, thereby resulting in sequence variations, or truncations, at the C-terminal E and F regions of the protein (Fig. 1) (40, 41).

Consequently, the LBD of the protein is the primary functional component that is altered in these splice variants. Indeed, all of the hERβ isoforms can bind to DNA and form dimers with ERβ1 in the presence of E2 (15, 16). Interestingly, heterodimers between hERβ1 and any of the other splice variants enhanced transactivation compared to hERβ1 homodimers in an ERE-dependent reporter assay in the presence of E2 and other estrogenic compounds in HEK293 cells (15). However, only the full length hERβ1 can interact with SRC-1 (steroid receptor coactivator-1) to induce transactivation, highlighting the importance of the hERβ C-terminus for coregulatory protein binding (15). These data suggest that only one coregulatory protein binding site is needed in a hERβ dimer, and indeed, the absence of the second binding site seems to facilitate hERβ actions.

Human ERβ2 (also called hERβcx) is the most characterized of the human variants and is widely considered to function as a dominant negative receptor for ERα (47). Molecular modeling demonstrated that hERβ2 has altered (more restricted, “tight”) 3D structures in both the ligand binding pocket and coregulator binding surface, which impairs its ability to bind ligands (15, 16). Hence, hERβ2 has no ligand dependent transcriptional activity, yet it retains some ligand independent activity consistent with its intact AF-1 region (16).

Structurally, hERβ4 and hERβ5 are the smallest, as they completely lack helix 12 and the entire F domain, resulting in a more open conformation of the ligand binding pocket (41, 48). This conformation creates an unstable association with ligands and consequently lower binding affinities; however, unlike hERβ2, they are both able to bind ligands to some extent. In reporter gene assays, these variants also exhibit ligand independent activity similar to hERβ2 due to the intact AF-1 domain. For instance, in ERE-driven reporter assays in COS-7 cells, hERβ4 and hERβ5 only demonstrated ligand independent increases in promoter activity, while hERβ1 appeared to drive both ligand dependent and ligand independent promoter activity (48).

All of the apo-hERβ splice variants can constitutively activate ERE promoter activity and repress AP-1 promoter activity in reporter assays using HT-22 cells (mouse-derived hippocampal neuronal cell line), with E2 treatment only affecting the full-length hERβ1 isoform (16). At the more complex AVP promoter, all of the hERβ isoforms showed ligand independent repression of AP-1-mediated promoter activity, yet only hERβ1-mediated activity was abolished using the antagonist ICI 182 780 (16). Decreased ligand binding affinities of hERβ splice variants have important implications for therapeutic strategies that employ ER agonists or antagonists, as the success of these therapies must rely on the ligand dependent activation of the dominant ERβ1 isoform. Therefore, an increase in alternative splicing that shifts the expression profile of ERβ isoforms could render hormone-based therapies completely ineffective, or potentially amplify the effects if there is an increase in ERβ1 :splice variant heterodimerization.

To our knowledge, there is no experimental evidence to suggest that alternative splicing of ERβ alters its heterodimerization with ERα. However, based on the sequences of the rodent ERβ splice variants in particular, it is reasonable to predict that dimerization with ERα would be altered. Current therapeutic interventions might not account for variations in dimerization proficiency, but future compounds could be designed to exploit this different heterodimerization profile and develop more precisely targeted therapeutic strategies.

REGULATION OF ERβ ALTERNATIVE SPLICING

Alternative splicing represents a mechanism by which the cell can increase proteomic and, consequently, functional diversity from a single pre-mRNA transcript. Normally, splicing is achieved by the coordinated actions of RNA:protein complexes called the spliceosome, which are composed of both small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) U1-U6 and associated small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs). The spliceosome, when positioned on specific nucleotide recognition sites, such as the polypyrimidine tract (PPT) and the branchpoint sequence (BPS), functions to remove non-coding introns from the pre-mRNA transcript and ligate the remaining exons to a cohesive coding sequence mRNA (49–52). Conversely, alternative splicing occurs when variable compositions of exons and introns of a particular gene are irregularly excluded or included in the mature mRNA product, a process which is often regulated by tissue-specific RNPs (53, 54). The selective exclusion or inclusion of exons can result in the formation of premature stop codons and untranslatable protein products, or translated protein products with widely divergent functional properties compared to the dominant isoform.

The five human ERβ variants (hERβ1-5) result from exon exclusion or exon skipping, which ultimately give rise to protein structures with variable length C-terminal truncations in the F and E domains (15). Exon skipping can occur through the concerted actions of trans-acting factors differentially binding to cis-acting elements on the DNA sequence. Cis-acting elements include exonic splicing enhancers (ESE) and exonic splicing silencers (ESS). These sequence motifs, complexed with SR (serine arginine rich) proteins or snRNPs, can then facilitate or inhibit the assembly of the spliceosome around weak splice sites. Alternative splicing events at weak splice sites can then result in mature mRNAs with various exon compositions, as in the case of the ERβ isoforms. As previously discussed, these receptor isoforms have functionally unique roles in both E2-mediated and ligand independent signaling processes compared to the dominant ERβ1 isoform (14–17, 45, 48, 55). This raises the possibility that increased alternative splicing events will significantly impact normal cellular and physiological processes, leading to an increased risk for various pathologies. Therefore, it is important to determine how ERβ alternative splicing is carefully regulated to produce cell-type specific expression profiles of ERβ isoforms, and how these expression profiles relate to diverse cellular functions.

There is little known about how the splice variants are selectively processed by specific cell types, but evidence shows that there are discrete spatial and temporal expression patterns for ERβ splice variants in the brain (43, 46, 56). For instance, an abundance of rERβ2 protein expression was detected in rat hypothalamic nuclei, such as the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and the supraoptic nucleus (SON), whereas expression levels were low in the dentate gyrus (DG) (56). Analysis of a wide variety of brain regions showed that overall rERβ2 was the most highly expressed rERβ splice variant in the rat brain, except in the hippocampus where rERβ1δ4 levels were most abundant (43). These data suggest that the expression of rERβ splice variants is differentially regulated by brain region and likely coupled to specific neurological and/or behavioral functions. However, it remains to be seen whether specific rERβ splice variant expression is initiated upstream of cellular differentiation, priming the progression of neural stem cells to their respective fates, or whether specific rERβ splice variant expression is a consequence, or perhaps even an artifact, of already differentiated brain regions.

Cis- and trans-regulatory elements

Distinct cis-regulatory sequences in the human ERβ gene confer a molecular architecture that facilitates alternative splicing in prostate and mammary glands, raising the possibility that these same molecular mechanisms contribute to brain-region specific splicing. For instance, full length hERβ transcription can be initiated from 2 different promoters characterized as 5′ untranslated exons, 0K and 0N, in the prostate and mammary glands (57–59). In the prostate gland, hERβ1 and hERβ2 were predominantly transcribed from the 0N promoter, whereas hERβ5 was uniquely transcribed from the 0K promoter (58). In contrast, both hER1 and hERβ5 were transcribed from the 0K promoter in benign and malignant mammary epithelial cells (60). Depending on the site of transcription initiation, the nascent RNA transcript will include different lengths of 5′ untranslated sequences (i.e. UTRa and UTRc), which can have stable secondary structures preventing translation of the RNA product (60). Moreover, these 5′UTRs can dictate differential expression of ERβ splice variants through disruption or recruitment of spliceosome components. Specifically, the presence of UTRa corresponded to hERβ1 and hERβ5 expression, whereas the presence of UTRc corresponded to hERβ2 expression in MCF-7 cells (60). Importantly, translation efficiency varied even for individual UTRs depending on cell type, suggesting that other cellular components, such as trans-acting factors, interact with the 5′UTR sequence and dictate cell specific expression. There is also evidence that the translational efficiency of the ERβ splice variants depends, in part, on crosstalk between the 5′UTR sequence and the length of the 3′UTR, with shorter lengths promoting translation, despite the presence of a typically inhibitory 5′UTRa (61). To our knowledge, these same alternative promoter elements have not yet been defined for the rodent ERβ isoforms.

The alternative hERβ promoters are also subject to epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation. DNA methylation can regulate alternative splicing by recruiting methyl-binding domain proteins, such as MeCP2, that then associate with splicing factors (62). For instance, MeCP2 has been shown to associate with splicing factors such as the pre-mRNA processing factor 3 (Prpf3), which presumably could affect splicing dynamics (63). In ovarian carcinoma cells, an interesting correlation was observed in which the hypermethylation of the 0N promoter resulted in the decreased expression of hERβ1, hERβ2, and hERβ4 mRNA, and increased expression of hERβ5 mRNA. These findings suggest that ON promoter hypermethylation could promote the assembly of specific spliceosome components through methyl-binding domain proteins, ultimately influencing the differential alternative splicing of hERβ (64). However, the mechanism behind the selective enhancement of specific hERβ splice variant expression (namely hERβ1, hERβ2, and hERβ4) is still unclear, since all four human splice variants including hERβ5 are the result of similar exon exclusion events.

It is important to note that another layer of complexity is added when considering the role of trans-acting factors that could potentially interact with the abovementioned cis-regulatory elements. The molecular mechanisms of ERβ splice variant regulation in the brain are still largely uncharacterized; however, a possible explanation of the unique expression profiles can be attributed to the brain region-specific expression of RNPs (i.e. trans-acting factors) that comprise the spliceosome. Indeed, recent unpublished work in our lab has identified putative consensus binding sites for NOVA-1 (neuro-oncological ventral antigen-1), a neuron-specific RNP, upstream of the 54bp insert in ERβ2, as well as correlative changes in NOVA-1 expression with ERβ2 in several brain regions (65). Aside from these preliminary studies, there have been no publications to date identifying specific trans-acting factors regulating ERβ alternative splicing in the brain.

Activity dependent splicing

Neurons are intrinsically excitable cells, and evidence suggests that brain region-specific expression profiles of ERβ splice variants could be due to regional differences in neuronal firing activity. A recent study demonstrated that neuronal activity induced by calcium influx via N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors (NMDARs) and L-type voltage-dependent calcium channels (L-VDCC) could regulate alternative splicing processes (66). Transient increases in intracellular calcium concentrations can activate calcium-sensitive kinases, such as protein kinase C (PKC) and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV (CaMKIV). These kinases, once activated, can then alter the phosphorylation status and function of RNA binding proteins, ultimately resulting in alternative splicing of the nascent RNA transcript (67). This mode of regulation would represent a mechanism whereby the abundance of RBPs would not necessarily change in concordance with splice variant expression; instead, RBP activity would simply be turned “on” or “off” by a phosphorylation event. For example, Iijima and colleagues demonstrated that neurexin (Nrxn) could be alternatively spliced by CaMKIV-dependent phosphorylation of the ribonucleoprotein SAM68 (Src-associated substrate in mitosis of 68 kDa) (68). Although there has been no evidence for the activity dependent splicing of ERβ up to this point, Ratti and colleagues demonstrated that NOVA1 activity could be affected by PKC-dependent signaling pathways (69). These data, in conjunction with findings that NOVA1 can alter ERβ splice variant expression, suggest that the alternative splicing of ERβ could also be regulated by fluctuations in intracellular calcium concentrations mediated by neuronal activity (69). Since hypothalamic neuronal firing rates are distinct from other brain regions such as the cortex, activity-dependent splicing of ERβ itself, or even trans-acting factors that affect ERβ splicing, could potentially explain the unique expression of ERβ splice variants that was observed in discrete brain regions.

RNAPII kinetics

Splicing can occur co-transcriptionally, and an essential component to this process is RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) (70). Various splicing factors such as SR proteins have been shown to associate with the C-terminal domain (CTD) of RNAPII (52). These RNA binding proteins can then promote the assembly of spliceosome components to allow for the physiological processing of nascent mRNA transcripts. Therefore, it is not surprising that altering the rate of RNAPII elongation can result in alternatively spliced mRNAs, as splice sites can either be passed over or recognized depending on the pace of elongation. Generally, factors that slow down RNAPII elongation result in exon inclusion, as there is a longer time interval available for the assembly of the spliceosome around a weak splice site (71). In agreement with these findings, our lab previously showed that inhibiting topoisomerase I (TOP1) activity to slow splicing kinetics allowed for the aberrant recognition of weak splice sites present in the rERβ pre-mRNA. As expected, rERβ2 transcripts, with characteristic exon inclusions, were significantly increased when TOP1 was inhibited in a hypothalamic derived GT1-7 cell line (72).

Aging and E2 deprivation

The number of alternative splicing events in the human brain have been shown to increase with age; therefore, it can be speculated that ERβ splice variant expression is also increased during the aging process (1). Consistent with this hypothesis, our lab demonstrated that rERβ2 expression was significantly increased in the hypothalamus of 18-month-old (aged) female rats compared to their 3-month-old (young) counterparts (72). However, the other rat ERβ splice variants were not detected in significant concentrations in the brain regions tested, and therefore, it cannot be concluded that all ERβ splice variants increase with age. Additionally, another layer of complexity must be considered in females, as aging is closely associated with the onset of menopause, during which there is a loss of circulating E2. Interestingly, age and E2 deprivation together have been shown to alter rERβ2 expression in a brain-region specific manner, suggesting that the normal aging process and the absence of E2 could have both independent and coordinated effects on the alternative splicing of ERβ (72). These findings were also consistent with a separate study showing that the deprivation of E2 corresponded to the increased expression of rERβ2 in both the rat brain and circulating white blood cells (73). Moreover, increased rERβ2 expression correlated with a reduction in the effectiveness of E2 treatment on depressive behaviors using a forced swim test paradigm (73). Together, these data suggest that the presence of E2 inhibits the expression of rERβ2 splice variants in the brain; however, the mechanism for how this occurs is still unclear.

ERβ SPLICE VARIANTS AND AGE-RELATED DISEASE

To date, the majority of studies implicating ERβ splice variants in disease have focused on the role of these variants in the context of human prostate, breast, ovarian and thyroid cancers. However, as we have described above, alternative splicing of ERβ can change the functional domains which are present in the protein. Deletions or insertions within these functional domains can impact ERβ-DNA binding, ligand binding affinity, dimer formation, and/or interactions with co-regulatory proteins. Therefore, it is logical to predict that alternative ERβ splicing can impact a wide variety of pathological conditions that have yet to be defined.

Clinical studies have shown that the expression of hERβ splice variants can vary dramatically between healthy and cancerous tissues in age-matched patients. For example, hERβ5 was overexpressed in endometrial carcinoma tissues compared to normal endometrial tissue, and the increased expression of hERβ5 was strongly correlated with an increased expression of several oncogenes (11). An enrichment of hERβ5 was also observed in patients with HER2 positive and triple-negative breast cancer and predicted poorer prognostic outcomes (74). By contrast, another study reported that increased hERβ2 and hERβ5 expression was correlated with a better relapse-free survival rate in 105 post-menopausal breast cancer patients; however that study did not report the HER2 status in those tumors, suggesting that even within breast cancers, there are context specific functions of ERβ splice variants (75). The development of malignant prostate tumors also revealed a dramatic shift in the ratio of the dominant hERβ1 isoform to its alternatively spliced variants. Specifically, the expression of hERβ1, which is normally anti-proliferative in prostate tissue, gradually declines and then becomes undetectable coincident with an increased expression of hERβ2 during the progression of prostate cancer (76, 77). Moreover, stable overexpression of hERβ2 in prostate tumor-derived PC-3 cells resulted in increased expression of several oncogenic genes (78). Taken together, these data suggest that some hERβ splice variants can increase oncogene expression leading to carcinogenesis in certain tissues.

Interestingly, the hormonal milieu appears to also play a role in determining the carcinogenic potential of hERβ splice variants. For instance, hERβ2 was expressed in 100% of patients with papillary thyroid cancers (PTC), and its expression was correlated with increased Ki-67 and VEGF expression in both postmenopausal women and men (i.e. low E2) (18). In contrast, hERβ2 expression was lower in pre-menopausal women with PTC and concurrent lymph node metastasis, suggesting that higher E2 levels prevented the progression of PTC by regulating the expression of hERβ2 (18). These data are consistent with those from our laboratory and others demonstrating increased expression of ERβ2 in the brain of aged ovariectomized female rats (i.e. low E2), and the subsequent decrease of ERβ2 following E2 treatment (72, 73). Overall, evidence suggests that there is a correlation between the expression of ERβ alternative splice variants and cancer progression. Although to our knowledge, no studies have demonstrated a direct causal role of ERβ splice variants in tumor development.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, there have been remarkably few studies investigating the consequences of increased ERβ alternative splicing in the context of neurological diseases (79–81). The ERβ splice variants that have been identified in humans and rodents are diverse, not only in their biochemical structure, but also in their cellular and physiological function, allowing predictable consequences for age-related shifts in the ratios of alternatively spliced variants in the brain. Different cell types and tissues exhibit distinct ERβ splice variant expression profiles, further underscoring the probability that each variant has a unique physiological function in a given cell type. The precise molecular mechanisms regulating ERβ alternative splicing is still largely unknown, and are further complicated by the likelihood of tissue-specific factors that direct alternative splicing events. Dysregulation of ERβ splicing events can contribute to disease progression, as characterized in various cancer paradigms, yet many of these studies have been correlative and do not address whether alternative ERβ splice variants are causal factors for disease progression.

As discussed throughout this review, several studies have focused on determining the functional role of ERβ in the brain. However, few have differentiated between the dominant isoform and the alternatively spliced variants, or examined them in a cell-type or brain-region specific manner (65, 81). Moreover, clinical studies examining patient samples in various disease states have not taken splice variant expression into consideration (79). These oversights could severely limit our understanding of aging and associated disease states, as these alternatively spliced variants can have widely divergent functional properties compared to the parent isoform. Technical limitations often preclude the assessment of all possible isoforms, because structural and sequence properties of alternatively spliced variants are not conducive to the creation of highly specific antibodies. Therefore, the development of novel antibody-free techniques for rapid detection of alternatively spliced variants in situ, as opposed to relying on mass spectrometry detection from tissue homogenates, is an important future direction. Failure to account for alternative splicing in could impede the development of more precisely targeted therapeutics, as the field of personalized medicine moves forward.

References

- 1.Tollervey JR, Wang Z, Hortobagyi T, Witten JT, Zarnack K, Kayikci M, Clark TA, Schweitzer AC, Rot G, Curk T, Zupan B, Rogelj B, Shaw CE, Ule J. Analysis of alternative splicing associated with aging and neurodegeneration in the human brain. Genome Res. 2011;21(10):1572–82. doi: 10.1101/gr.122226.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tress ML, Abascal F, Valencia A. Alternative Splicing May Not Be the Key to Proteome Complexity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42(2):98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen KB, Dredge BK, Stefani G, Zhong R, Buckanovich RJ, Okano HJ, Yang YY, Darnell RB. Nova-1 regulates neuron-specific alternative splicing and is essential for neuronal viability. Neuron. 2000;25(2):359–71. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stilling RM, Benito E, Gertig M, Barth J, Capece V, Burkhardt S, Bonn S, Fischer A. Deregulation of gene expression and alternative splicing affects distinct cellular pathways in the aging hippocampus. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8373 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anthony K, Gallo JM. Aberrant RNA processing events in neurological disorders. Brain Res. 2010;1338:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao C, Dahlman-Wright K, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen signaling via estrogen receptor {beta} J Biol Chem. 2010;285(51):39575–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.180109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stellato C, Porreca I, Cuomo D, Tarallo R, Nassa G, Ambrosino C. The “busy life” of unliganded estrogen receptors. Proteomics. 2016;16(2):288–300. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201500261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans RM. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83(6):835–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flouriot G, Brand H, Seraphin B, Gannon F. Natural trans-spliced mRNAs are generated from the human estrogen receptor-alpha (hER alpha) gene. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(29):26244–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203513200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girault I, Andrieu C, Tozlu S, Spyratos F, Bieche I, Lidereau R. Altered expression pattern of alternatively spliced estrogen receptor beta transcripts in breast carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2004;215(1):101–12. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haring J, Skrzypczak M, Stegerer A, Lattrich C, Weber F, Gorse R, Ortmann O, Treeck O. Estrogen receptor beta transcript variants associate with oncogene expression in endometrial cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2012;29(6):1127–36. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herynk MH, Fuqua SA. Estrogen receptor mutations in human disease. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(6):869–98. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishunina TA, Swaab DF. Decreased alternative splicing of estrogen receptor-alpha mRNA in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(2):286–96 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanstein B, Liu H, Yancisin MC, Brown M. Functional analysis of a novel estrogen receptor-beta isoform. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13(1):129–37. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.1.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung YK, Mak P, Hassan S, Ho SM. Estrogen receptor (ER)-beta isoforms: a key to understanding ER-beta signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(35):13162–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605676103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mott NN, Pak TR. Characterisation of human oestrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) splice variants in neuronal cells. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012;24(10):1311–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2012.02337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pak TR, Chung WC, Lund TD, Hinds LR, Clay CM, Handa RJ. The androgen metabolite, 5alpha-androstane-3beta, 17beta-diol, is a potent modulator of estrogen receptor-beta1-mediated gene transcription in neuronal cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146(1):147–55. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong W, Li J, Zhang H, Huang Y, He L, Wang Z, Shan Z, Teng W. Altered expression of estrogen receptor beta2 is associated with different biological markers and clinicopathological factors in papillary thyroid cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(6):7149–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poola I, Abraham J, Liu A. Estrogen receptor beta splice variant mRNAs are differentially altered during breast carcinogenesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;82(2–3):169–79. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(02)00185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakraborty TR, Ng L, Gore AC. Age-related changes in estrogen receptor beta in rat hypothalamus: a quantitative analysis. Endocrinology. 2003;144(9):4164–71. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shults CL, Pinceti E, Rao YS, Pak TR. Aging and loss of circulating 17beta-estradiol alters the alternative splicing of ERbeta in the female rat brain. Endocrinology. 2015:en20151514. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waters EM, Yildirim M, Janssen WG, Lou WY, McEwen BS, Morrison JH, Milner TA. Estrogen and aging affect the synaptic distribution of estrogen receptor beta-immunoreactivity in the CA1 region of female rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2011;1379:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(12):5925–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosselman S, Polman J, Dijkema R. ER beta: identification and characterization of a novel human estrogen receptor. FEBS Lett. 1996;392(1):49–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helsen C, Claessens F. Looking at nuclear receptors from a new angle. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;382(1):97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruff M, Gangloff M, Wurtz JM, Moras D. Estrogen receptor transcription and transactivation: Structure-function relationship in DNA- and ligand-binding domains of estrogen receptors. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2(5):353–9. doi: 10.1186/bcr80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar R, Zakharov MN, Khan SH, Miki R, Jang H, Toraldo G, Singh R, Bhasin S, Jasuja R. The dynamic structure of the estrogen receptor. J Amino Acids. 2011;2011:812540. doi: 10.4061/2011/812540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tremblay GB, Tremblay A, Labrie F, Giguere V. Dominant activity of activation function 1 (AF-1) and differential stoichiometric requirements for AF-1 and -2 in the estrogen receptor alpha-beta heterodimeric complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(3):1919–27. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tremblay A, Tremblay GB, Labrie F, Giguere V. Ligand-independent recruitment of SRC-1 to estrogen receptor beta through phosphorylation of activation function AF-1. Mol Cell. 1999;3(4):513–9. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Detka D, Kalita K, Kaczmarek L. Activation function 1 domain plays a negative role in dimerization of estrogen receptor beta. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;99(2–3):157–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webb P, Nguyen P, Valentine C, Lopez GN, Kwok GR, McInerney E, Katzenellenbogen BS, Enmark E, Gustafsson JA, Nilsson S, Kushner PJ. The estrogen receptor enhances AP-1 activity by two distinct mechanisms with different requirements for receptor transactivation functions. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13(10):1672–85. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.10.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Lone R, Frith MC, Karlsson EK, Hansen U. Genomic targets of nuclear estrogen receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(8):1859–75. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paech K, Webb P, Kuiper GG, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J, Kushner PJ, Scanlan TS. Differential ligand activation of estrogen receptors ERalpha and ERbeta at AP1 sites. Science. 1997;277(5331):1508–10. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pace P, Taylor J, Suntharalingam S, Coombes RC, Ali S. Human estrogen receptor beta binds DNA in a manner similar to and dimerizes with estrogen receptor alpha. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(41):25832–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chakraborty S, Willett H, Biswas PK. Insight into estrogen receptor beta-beta and alpha-beta homo- and heterodimerization: A combined molecular dynamics and sequence analysis study. Biophys Chem. 2012;170:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zwart W, de Leeuw R, Rondaij M, Neefjes J, Mancini MA, Michalides R. The hinge region of the human estrogen receptor determines functional synergy between AF-1 and AF-2 in the quantitative response to estradiol and tamoxifen. J Cell Sci. 123(Pt 8):1253–61. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel SR, Skafar DF. Modulation of nuclear receptor activity by the F domain. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;418(Pt 3):298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peters GA, Khan SA. Estrogen receptor domains E and F: role in dimerization and interaction with coactivator RIP-140. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13(2):286–96. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.2.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chu S, Fuller PJ. Identification of a splice variant of the rat estrogen receptor beta gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;132(1–2):195–9. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(97)00133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu B, Leygue E, Dotzlaw H, Murphy LJ, Murphy LC, Watson PH. Estrogen receptor-beta mRNA variants in human and murine tissues. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;138(1–2):199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore JT, McKee DD, Slentz-Kesler K, Moore LB, Jones SA, Horne EL, Su JL, Kliewer SA, Lehmann JM, Willson TM. Cloning and characterization of human estrogen receptor beta isoforms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247(1):75–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petersen DN, Tkalcevic GT, Koza-Taylor PH, Turi TG, Brown TA. Identification of estrogen receptor beta2, a functional variant of estrogen receptor beta expressed in normal rat tissues. Endocrinology. 1998;139(3):1082–92. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Price RH, Jr, Lorenzon N, Handa RJ. Differential expression of estrogen receptor beta splice variants in rat brain: identification and characterization of a novel variant missing exon 4. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;80(2):260–8. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maruyama K, Endoh H, Sasaki-Iwaoka H, Kanou H, Shimaya E, Hashimoto S, Kato S, Kawashima H. A novel isoform of rat estrogen receptor beta with 18 amino acid insertion in the ligand binding domain as a putative dominant negative regular of estrogen action. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246(1):142–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pak TR, Chung WC, Hinds LR, Handa RJ. Estrogen receptor-beta mediates dihydrotestosterone-induced stimulation of the arginine vasopressin promoter in neuronal cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148(7):3371–82. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Price RH, Jr, Butler CA, Webb P, Uht R, Kushner P, Handa RJ. A splice variant of estrogen receptor beta missing exon 3 displays altered subnuclear localization and capacity for transcriptional activation. Endocrinology. 2001;142(5):2039–49. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.5.8130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogawa S, Inoue S, Watanabe T, Orimo A, Hosoi T, Ouchi Y, Muramatsu M. Molecular cloning and characterization of human estrogen receptor betacx: a potential inhibitor of estrogen action in human. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(15):3505–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.15.3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poola I, Abraham J, Baldwin K, Saunders A, Bhatnagar R. Estrogen receptors beta4 and beta5 are full length functionally distinct ERbeta isoforms: cloning from human ovary and functional characterization. Endocrine. 2005;27(3):227–38. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:27:3:227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wahl MC, Will CL, Luhrmann R. The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell. 2009;136(4):701–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith L. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression by alternative 5′-untranslated regions in carcinogenesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36(Pt 4):708–11. doi: 10.1042/BST0360708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith DJ, Query CC, Konarska MM. “Nought may endure but mutability”: spliceosome dynamics and the regulation of splicing. Mol Cell. 2008;30(6):657–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Das R, Yu J, Zhang Z, Gygi MP, Krainer AR, Gygi SP, Reed R. SR proteins function in coupling RNAP II transcription to pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2007;26(6):867–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glisovic T, Bachorik JL, Yong J, Dreyfuss G. RNA-binding proteins and post-transcriptional gene regulation. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(14):1977–86. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peng B, Lu B, Leygue E, Murphy LC. Putative functional characteristics of human estrogen receptor-beta isoforms. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;30(1):13–29. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chung WC, Pak TR, Suzuki S, Pouliot WA, Andersen ME, Handa RJ. Detection and localization of an estrogen receptor beta splice variant protein (ERbeta2) in the adult female rat forebrain and midbrain regions. J Comp Neurol. 2007;505(3):249–67. doi: 10.1002/cne.21490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hirata S, Shoda T, Kato J, Hoshi K. The multiple untranslated first exons system of the human estrogen receptor beta (ER beta) gene. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;78(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee MT, Ouyang B, Ho SM, Leung YK. Differential expression of estrogen receptor beta isoforms in prostate cancer through interplay between transcriptional and translational regulation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;376(1–2):125–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang X, Leung YK, Ho SM. AP-2 regulates the transcription of estrogen receptor (ER)-beta by acting through a methylation hotspot of the 0N promoter in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2007;26(52):7346–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith L, Brannan RA, Hanby AM, Shaaban AM, Verghese ET, Peter MB, Pollock S, Satheesha S, Szynkiewicz M, Speirs V, Hughes TA. Differential regulation of oestrogen receptor beta isoforms by 5′ untranslated regions in cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14(8):2172–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith L, Coleman LJ, Cummings M, Satheesha S, Shaw SO, Speirs V, Hughes TA. Expression of oestrogen receptor beta isoforms is regulated by transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Biochem J. 2010;429(2):283–90. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boeke J, Ammerpohl O, Kegel S, Moehren U, Renkawitz R. The minimal repression domain of MBD2b overlaps with the methyl-CpG-binding domain and binds directly to Sin3A. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(45):34963–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Long SW, Ooi JY, Yau PM, Jones PL. A brain-derived MeCP2 complex supports a role for MeCP2 in RNA processing. Biosci Rep. 2011;31(5):333–43. doi: 10.1042/BSR20100124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suzuki F, Akahira J, Miura I, Suzuki T, Ito K, Hayashi S, Sasano H, Yaegashi N. Loss of estrogen receptor beta isoform expression and its correlation with aberrant DNA methylation of the 5′-untranslated region in human epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(12):2365–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00988.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shults CL, Pinceti E, Rao YS, Pak TR. Expression of alternative splicing factors change in a brain region-specific manner with loss of circulating 17beta-estradiol in the aged female rat brain. Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Razanau A, Xie J. Emerging mechanisms and consequences of calcium regulation of alternative splicing in neurons and endocrine cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(23):4527–36. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1390-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu G, Razanau A, Hai Y, Yu J, Sohail M, Lobo VG, Chu J, Kung SK, Xie J. A conserved serine of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L (hnRNP L) mediates depolarization-regulated alternative splicing of potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(27):22709–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.357343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iijima T, Wu K, Witte H, Hanno-Iijima Y, Glatter T, Richard S, Scheiffele P. SAM68 regulates neuronal activity-dependent alternative splicing of neurexin-1. Cell. 2011;147(7):1601–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ratti A, Fallini C, Colombrita C, Pascale A, Laforenza U, Quattrone A, Silani V. Post-transcriptional regulation of neuro-oncological ventral antigen 1 by the neuronal RNA-binding proteins ELAV. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(12):7531–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beyer AL, Osheim YN. Splice site selection, rate of splicing, and alternative splicing on nascent transcripts. Genes Dev. 1988;2(6):754–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ip JY, Schmidt D, Pan Q, Ramani AK, Fraser AG, Odom DT, Blencowe BJ. Global impact of RNA polymerase II elongation inhibition on alternative splicing regulation. Genome Res. 2011;21(3):390–401. doi: 10.1101/gr.111070.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shults CL, Pinceti E, Rao YS, Pak TR. Aging and Loss of Circulating 17beta-Estradiol Alters the Alternative Splicing of ERbeta in the Female Rat Brain. Endocrinology. 2015;156(11):4187–99. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang JM, Hou X, Adeosun S, Hill R, Henry S, Paul I, Irwin RW, Ou XM, Bigler S, Stockmeier C, Brinton RD, Gomez-Sanchez E. A dominant negative ERbeta splice variant determines the effectiveness of early or late estrogen therapy after ovariectomy in rats. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wimberly H, Han G, Pinnaduwage D, Murphy LC, Yang XR, Andrulis IL, Sherman M, Figueroa J, Rimm DL. ERbeta splice variant expression in four large cohorts of human breast cancer patient tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146(3):657–67. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3050-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Davies MP, O’Neill PA, Innes H, Sibson DR, Prime W, Holcombe C, Foster CS. Correlation of mRNA for oestrogen receptor beta splice variants ERbeta1, ERbeta2/ERbetacx and ERbeta5 with outcome in endocrine-treated breast cancer. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33(3):773–82. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lai JS, Brown LG, True LD, Hawley SJ, Etzioni RB, Higano CS, Ho SM, Vessella RL, Corey E. Metastases of prostate cancer express estrogen receptor-beta. Urology. 2004;64(4):814–20. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leung YK, Lam HM, Wu S, Song D, Levin L, Cheng L, Wu CL, Ho SM. Estrogen receptor beta2 and beta5 are associated with poor prognosis in prostate cancer, and promote cancer cell migration and invasion. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(3):675–89. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dey P, Jonsson P, Hartman J, Williams C, Strom A, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors beta1 and beta2 have opposing roles in regulating proliferation and bone metastasis genes in the prostate cancer cell line PC3. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26(12):1991–2003. doi: 10.1210/me.2012.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bodo C, Rissman EF. New roles for estrogen receptor beta in behavior and neuroendocrinology. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2006;27(2):217–32. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Crider A, Thakkar R, Ahmed AO, Pillai A. Dysregulation of estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta), aromatase (CYP19A1), and ER co-activators in the middle frontal gyrus of autism spectrum disorder subjects. Mol Autism. 2014;5(1):46. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Taylor SE, Martin-Hirsch PL, Martin FL. Oestrogen receptor splice variants in the pathogenesis of disease. Cancer Lett. 2010;288(2):133–48. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]