Abstract

Using data from the International Dating Violence Study, this study examined the roles of early socialization, family social structure, and relationship dynamics factors on physical aggression in dating among U.S. college students in emerging adulthood. The interaction effects between these three domains of interest (early socialization, family social structure, and relationship dynamics) were explored to understand the underlying mechanisms that influenced victimization and perpetration in dating. In general, we found that family and relational variables associated with dating victimization and perpetration were fairly similar. Among the early socialization variables, experience of childhood neglect and having witnessed domestic violence were significantly related to victimization and perpetration. Living in a two-parent household appeared to exert a protective effect, although associations with parental education were not statistically significant. Further, the participants were more likely to experience victimization or impose aggression in dating relationships which were characterized by conflicts, distress, dominance, or psychological aggression. Overall, for the participants who came from a two-parent household, dominance in dating was linked to less violence. When the participants faced higher levels of psychological aggression, adverse early socialization factors were associated with higher levels of dating violence victimization and perpetration. Research and practice implications were discussed.

Keywords: college dating violence, early socialization, family social structure, relationship dynamics

Campus dating violence is a widespread social phenomenon which has ignited a heated debate in the medical, public health, and social science arenas. Frequently rated among the country’s most costly medical expenditures (Bonomi, Anderson, Rivara, & Thompson, 2009; Corso, Mercy, Simon, Finkelstein, & Miller, 2007), intimate partner violence (IPV), which entails the use of physical threat and force, has been clinically linked to increased risk for various adverse health outcomes including sexually transmitted infections, psychological distress, substance abuse, and physical injuries (e.g., Buelna, Ulloa, & Ulibarri, 2009; Temple & Freeman, 2011). Young college students, who are in emerging adulthood, present a compelling case study. Specifically, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2012) estimated that women in the age group of 18 to 24 years (also known as “emerging adults”) sustain one of the highest rates of IPV (Catalano, 2012). Further, prevalence estimates indicate that dating violence among college students, a specific subgroup of emerging adults, have typically ranged from 10% to 50% (e.g., Amar & Gennaro, 2005; Barrick, Krebs, & Lindquist, 2013; Kaukinen, Gover, & Hartman, 2012). Although differences in these estimates may be attributable to varying studies’ conceptualization of violence, such occurrence of violence often carries over into older adult relationships. Nationally, 69% of female and 53% of male adult IPV victims first experienced some forms of IPV before age 25 (Black et al., 2011), signaling the urgency to delve into studies that help guide intervention and prevent future occurrence of dating violence among this age group.

Despite the fact that women have often been portrayed as victims of their male perpetrators, IPV literature assessing at least two aspects of symmetry (the predominance of bidirectionality in IPV in which one is identified both as the victim and perpetrator simultaneously; and the pervasiveness of females as perpetrators) has increased steadily following the publication of Makepeace (1981)’s seminal article. Additionally, while family and relational factors have been found in previous studies to be associated with dating violence among college students (e.g., Gover, Kaukinen, & Fox, 2008; Kaukinen, 2014; Milletich, Kelley, Doane, & Pearson, 2010), little effort has been put forth to recognize the risk markers empirically linked to the aforementioned violence (i.e., perpetration and victimization) simultaneously. No research thus far has situated their studies within these two critical theoretical explanations (i.e., family and relationship dynamics) concurrently to understand physical aggression in dating among young college students. Similarly, previous research has failed to examine the interactive mechanisms between these factors that may reinforce or protect against physical dating violence in this population. In this study, exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the main effect of early socialization, family social structure, and relationship dynamics factors on physical dating violence victimization and perpetration among U.S. college students as well as the underlying interactive mechanisms through which these factors influenced dating violence. Teasing out these interactions may provide leverage for more effective clinical interventions.

Early socialization

Factors precipitating dating violence among college students may have their inception long before freshman year. It is critical to understand the family context and background in which early socialization takes place since family has always been classified as a critical socialization agent prior to emerging adulthood. Studies of child development, for example, have long highlighted the importance of a strong family upbringing on health, conduct, and achievement. Of particular note is on how family processes shape interpersonal relations, emotion regulation, and communication skills (e.g., Bariola, Gullone, & Hughes, 2011; Paat, 2011). Studies based on social learning also stress how violence can be acquired through observational learning and the intergenerational transmission of violence (e.g., Cannon, Bonomi, Anderson, & Rivara, 2009; Eriksson & Mazerolle, 2015). Although attachment theory research has identified strong associations between family ties, sense of security, and self-esteem maintenance - all pertinent protective factors for avoiding abusive dating relationships (Kochanska et al., 2010; Ooi, Ang, Fung, Wong, & Cai, 2006), experiences of childhood neglect, family disengagement, and childhood exposure to violence, including corporal punishment and witnessing domestic violence, on the contrary, increase propensities for dating violence either perpetration or victimization (Bensley, Van Eenwyk, & Simmons, 2003; Milletich et al., 2010; Renner & Whitney, 2012; Straus & Savage, 2005; Temple, Shorey, Tortolero, Wolfe, & Stuart, 2013).

Family social structure and household type

From the macro perspective, family social structure can be perceived as the household’s social position/status within the current societal stratification. Growing up in a household with both biological parents has been empirically linked to greater parental involvement and resources (Thomson & McLanahan, 2012). Conversely, youth who grow up in a non-two parental household are at greater risk for child delinquency, teenage pregnancy, substance abuse, and victimization (all of which correlate with dating violence) (Eitle, 2005; Vanassche, Sodermans, Matthijs, & Swicegood, 2014). With regard to household socio-economic status, research on parental education is mixed but several characteristics may distinguish highly educated parents: 1) they are more capable of offering an environment conducive to children’s optimal development (Guryan, Hurst, & Kearney, 2008); 2) they may be more cognizant of child development aspects; and 3) many are likely to rely on expert guidance or emphasize concerted cultivation in parenting issues (see Lamanna, & Riedmann, 2012; Roksa & Potter, 2011). In general, many family scholars regard household stability as a key factor in child socialization since negativity embedded within families characterized by economic related interparental discord can “over-spill” to impact their children’s development (Lee, Wickrama, & Simons, 2013; Ponnet, 2014).

Relationship dynamics

On the macro scale, violence against women is shaped by societal norms, beliefs, and myths that support or discourage violence in intimate partner unions. Sociocultural scholars, for instance, have posited that endorsement of rigid gender stereotypes and patriarchal sex role attitudes, which put men in positions of power, greatly increase women’s risk of victimization (Allen & Devitt, 2012; Caldwell, Swan, & Woodbrown, 2012). This postulation is supported by the feminist outlook which perceives the incidence of intimate violence to be more prevalent among non-egalitarian partnerships (see Bell & Naugle, 2008; McCloskey, Williams, & Larsen, 2005; Shannon et al., 2012). While the impact of patriarchal values has yet to receive widespread support, many studies consider attributes such as controlling behaviors, possessiveness, jealousy, impulsiveness, poor conflict resolution skills, antisocial personality, psychological aggression, and anger outbursts as significant contextual factors contributing to the onset of relational aggression (e.g., Antai, 2011; Dykstra, Schumacher, Mota, & Coffey, 2015; Kuijpers, van der Knaap, & Winkel, 2012; Shorey, Brasfield, Febres, & Stuart, 2011). Although other factors such as relational satisfaction and commitment may minimize dating violence (Slotter, et al., 2012), some studies have indicated that dating violence happens more readily in committed relationships than in casual ones; however, the impact may be less severe for marital relationships in which the couple has future plans together (see a review by Katz, Kuffel, & Coblentz, 2002). Other studies found that cohabiting couples may be more susceptible to IPV than married couples (e.g., Caetano, Vaeth, & Ramisetty-Mikler, 2008).

Interaction effects

How might the main effects of early socialization, family social structure, and relationship dynamics interact to influence college dating violence? Poor early socialization may be linked to formation of dysfunctional interpersonal connection in dating in part because poor role models can become targets for observable learning (see Akers & Sellers, 2009). Pflieger & Vazsonyi (2006) found that low self-esteem partially mediated the association between parenting processes and dating violence among the adolescent sample in their study but this empirical link was contingent upon the participants’ socio-economic status. As Pflieger & Vazsonyi (2006) theorized, efficacious perception and self-worth, formed as a result of family socialization, may influence viewpoint with regard to the extent that disrespect and abuse are tolerated in a dating relationship. Additionally, while family and relational quality offer both theoretical and empirical merits for examining this social phenomenon, the family and dating processes may be inherent to a given structural position, making it challenging to disentangle the association of these elements. Some studies, for example, have suggested that intimate partner violence is disproportionately more prevalent among those in the lower social economic strata (Frias & Angel, 2005; West, 2004). Early researchers, have postulated that parenting in poverty elevated frequent usage of physical punishment and placed greater demands on child obedience (e.g., Hanson, McLanahan, & Thomson, 1997; McLoyd, 1998). Indeed, Dietz (2000) found that parents with fewer resources including education were more likely to incorporate typical to severe corporal punishment in childrearing. Similarly, Ceballo and McLoyd (2002) revealed that residence in a stressful environment such as dangerous and poor neighborhoods increased the likelihood of using punitive parenting strategies in single parenthood. Though the inter-relationships of these factors are inconclusive, the aforementioned findings provide invaluable insights implying that the influence of early socialization, family social structure, and relationship dynamics on dating outcomes may not seem straightforward. Taken together, if early socialization, structural positions, and relationship dynamics are empirically linked to one another, examination of their interaction effects is imperative to understanding the driving forces of dating violence.

This study

Given that dating violence frequently occurs in a bidirectional context in which one partner initiates aggression and the other reciprocates in self-defense and vice versa (Kaukinen, Gover, & Hartmna, 2012; Straus & Ramiez, 2007), several theory-guided hypotheses were postulated to examine the association of early socialization, family social structure, and relational factors with physical aggression from the perspective of victims and perpetrators. First, we hypothesized that early socialization factors (i.e., experiencing childhood neglect, harsh corporal punishment, and witnessing domestic violence) would increase risks for dating violence victimization and perpetration. Second, we expected that family social structural factors (i.e., residing in a two-parent household and having parents with a higher level of education) would minimize the likelihood of victimization and perpetration. Next, hypothetically, greater conflict and distress in dating would be associated with higher likelihood of physical victimization and perpetration. Similarly, dominance, psychological aggression, and hostile attitudes toward women were hypothesized to increase risk for physical victimization and perpetration in dating. Conversely, we anticipated that both victimization and perpetration would be less likely to occur in a committed relationship. Additionally, we examined the interaction effects between these three domains of interest (early socialization, family social structure, and relationship dynamics) to understand the underlying mechanisms that might influence physical dating victimization and perpetration among young college students. In particular, we expected that protective family (i.e., two-parent household and parents’ educational attainment) and relational factors (i.e., relational commitment) would interact to minimize or cancel out the negative effect of adverse early socialization and relationship dynamics on physical dating violence. Conversely, we hypothesized that adverse early socialization (i.e., childhood neglect, corporal punishment, witnessing domestic violence) would intensify the influence of negative relational dynamics (couple conflict, relationship distress, dominance, and psychological aggression from the victim or perpetrator) on physical dating violence. Lastly, we controlled for the participants’ demographic variables in the data analysis.

Methods

Data for this investigation come from U.S. college students who participated in the International Dating Violence Study1 conducted by members of research consortiums from 32 nations at their respective universities. The aims were to investigate risk factors for partner violence, relationship behaviors, violent socialization, interpersonal relations, relational satisfaction, socio-psychological attributes, and dating profiles among college students from different socio-cultural contexts. Using a research protocol approved by relevant human subject protection authorities at each institution, the study sample constituted more than 14,000 undergraduates2 enrolled in a university course (mostly criminology, sociology, psychology, and family studies)3 taught by designated consortium members or other class settings where permission to administer the questionnaire was granted. To safeguard the participants’ identity, students were assured anonymity and had the option to withdraw or opt out of any question. Participation rates across universities ranged from 85% to 95% (Straus, 2004a, 2004b, 2008). The dataset is particularly well-suited for our study because it incorporated rich information from both the perpetrators’ and victims’ perspective of dating violence. Although the overall sample included participants with ages ranging from 18 to 40 years, the analytical sample for our study comprised 3,495 participants from a combination of 16 public, private, rural, urban, or suburban universities or colleges throughout the U.S. who were in emerging adulthood (between 18 and 25 years), and who had been in a heterosexual dating relationship that lasted at least one month.4

Dependent variables

The dependent variables for this study were two physical aggression composite scales derived from items from the revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2). The CTS2, for which previous studies have established construct validity and moderate to high reliability, measures violent behaviors including assault, injury, aggression, and coercion (Straus, 1990, 2004a, 2004b). Physical aggression, in this study, was operationalized as overt behaviors with the potential to inflict physical threat, damage, injury, or harm. Item responses were based on the participants’ current relationship which had lasted one month or more if they were currently dating, otherwise they were based on the participants’ most recent relationship which had lasted one month or more. Prior to constructing our outcome measures, exploratory factor analyses, which were used to examine the dimensionality and underlying structure of our measures, indicated a single factor solution respectively for both measures. Internal reliabilities for physical aggression victimization and perpetration were 0.76 and 0.76, respectively

Early socialization

Three variables were used to assess early socialization. First, encountering childhood neglect signified the (in)attentiveness of parents in fulfilling the participants’ cognitive, supervisory, emotional, and physical needs (Straus, Kinard, & Williams, 1995) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73). Second, experiencing corporal punishment assessed whether or not the participants had been spanked or hit a lot by either of their parents during their childhood (prior to reaching 12 years old) and adolescence. Next, witnessing domestic violence differentiated the participants who had seen either of their parents engaging in kicking, punching, or beating up each other or their respective partner (who was not the participants’ other biological parent) from the participants who had not.

Family social structure

Household structure and their parents’ educational attainment were proxies for the participants’ family social structure. A two-parent household was characterized by the presence of two parents who were married in the household of origin at the time the survey was administered. Father and mother’s highest level of education, continuous measures of the total number of years of education completed, were used as indirect measures of the family’s socio-economic status.

Relationship dynamics

In this study, seven variables were used to examine relationship dynamics in dating. Couple conflict evaluated areas of disagreement between the participants and their respective partners (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79). To measure relationship distress, the participants identified areas characterized by high conflicts and minimal positive interactions (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85). Dominance assessed the power entitlement and control that the participants exerted over their partner’s behaviors (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.69). Psychological aggression detailed the type of emotional abuse either party had exercised on each other (Cronbach’s alphas = 0.78 for victimization, 0.79 for perpetration). Hostility to women was measured by the participants’ negative attitudes toward women with higher scores reflecting unfavorable perceptions and feelings toward women (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78). Finally, to assess the participants’ commitment to their current relationship, they were asked to appraise if they believed that their dating relationship would last.

Socio-demographic variables

We controlled for gender and age in all analyses. Approximately 30% of the participants were males. On average, the participants were 20.10 years old.

Analytical procedures

This research process was conducted in several phases. First, we calculated frequency distributions and mean values of each physically aggressive act reported by the participants to examine the prevalence and chronicity of these behaviors respectively (see Strauss and Ramirez, 2007; Kaukinen et al., 2012). Next, given that our outcome measures are continuous variables, we employed multiple regression analyses to assess the association of early socialization, family social structure, and relationship dynamics on physical aggression in dating relationships from the victims’ and perpetrators’ perspective (Models 1 and 2, respectively). The multiple regression equation follows the format: Ŷ = A + B1X1 + B2X2 + … + BkXk where Ŷ serves as the predicted value of the dependent variable, A as the intercept, Xs as the independent variables5, and Bs as the coefficients of their respective X (Tabacnick & Fidell, 1996). Full Information Maximum Likelihood, which allows the estimation of parameters accurately in the absence of missing data (so long as the data are missing at random) was used as the estimation procedure (Enders & Bandalos, 2001). Additionally, we incorporated interaction terms constructed from the combination of variables measuring early socialization, family social structure, and relationship dynamics in our empirical models to explore the underlying relationships of these variables. To gauge the influence of our interaction terms, “low” signifies 1 standard deviation below the mean while “high” reflected 1 standard deviation above the mean. To counteract the challenge of making a Type I error (i.e., inaccurate rejection of the true null hypothesis), Bonferroni correction was employed to obtain a more conservative P-value (rather than using the conventional p-value) in our subsequent data analyses where interaction terms were incorporated. The Bonferroni adjusted p-value is derived from dividing the critical p-value by the number of tests performed. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13 (StataCorp., 2013).

Results

Table 1 shows the prevalence and chronicity of the types of physical aggression that the participants encountered as victims or perpetrators in their dating relationship while Table 2 presents psychometric properties for the variables included in this study. Approximately 10% or more of the participants had experienced each type of physical aggression either as a victim or perpetrator, with the occurrence of pushing/shoving and grabbing more prevalent and chronic than other aggressive acts (see table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of physical aggression items

| Physical Aggression Items | Frequency | Chronicity |

|---|---|---|

| Physical aggression (victim) | ||

| 1. My partner threw something at me that could hurt | 10.9 | 1.3 |

| 2. My partner twisted my arm or hair | 10.7 | 1.3 |

| 3. My partner pushed or shoved me | 17.9 | 1.6 |

| 4. My partner grabbed me | 18.1 | 1.6 |

| 5. My partner slapped me | 6.2 | 1.2 |

| Physical aggression (perpetrator) | ||

| 1. I threw somethng at my partner that could hurt | 12.6 | 1.4 |

| 2. I twisted my partner’s arm or hair | 9.5 | 1.3 |

| 3. I pushed or shoved my partner | 21.4 | 1.7 |

| 4. I grabbed my partner | 16.1 | 1.5 |

| 5. I slapped my partner | 10.3 | 1.2 |

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables in analyses

| Constructs | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Sample items | Response format | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||||||

| Physical aggression (victim)F | 5 | 40 | 7.0 | 4.18 |

|

8-point response scale (“this has never happened” to “more than 20 times in the past year”) | 0.76 |

| Physical aggression (perpetrator)F | 5 | 37 | 7.1 | 4.27 |

|

8-point response scale (“this has never happened” to “more than 20 times in the past year”) | 0.76 |

| Early socialization | |||||||

| Encountered childhood neglectF | 8 | 28 | 14.1 | 3.05 |

|

4-point response scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) | 0.73 |

| Experienced corporal punishment | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.44 | When I was less than 12 years old/a teenager, I was spanked or hit a lot by my mother or fatherR | Agree vs disagreeC | NA |

| Witnessed domestic violence | 0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.30 | When I was a kid, I saw my mother or father kick, punch, or beat up their partner | Agree vs disagreeC | NA |

| Family social structure | |||||||

| Two-parent household | 0 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.47 | What is your parents’ current marital status? | Married vs othersC | NA |

| Father’s education | 2 | 18 | 13.5 | 3.46 | How many years of education did your father complete? | Number in years | NA |

| Mother’s education | 2 | 18 | 13.4 | 3.33 | How many years of education did your mother complete? | Number in years | NA |

| Relational dynamics | |||||||

| Couple conflictF | 9 | 35 | 18.0 | 4.42 |

|

4-point response scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) | 0.79 |

| Relationship distressF | 8 | 32 | 15.5 | 4.83 |

|

4-point response scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) | 0.85 |

| DominanceF | 3 | 12 | 7.0 | 1.75 |

|

4-point response scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) | 0.69 |

| Psychological aggression (victim)F | 4 | 32 | 11.5 | 6.69 |

|

8-point response scale (“this has never happened” to “more than 20 times in the past year”) | 0.78 |

| Psychological aggression (perpetrator)F | 4 | 32 | 11.9 | 6.76 |

|

8-point response scale (“this has never happened” to “more than 20 times in the past year”) | 0.79 |

| Hostility to womenF | 5 | 20 | 9.5 | 2.68 |

|

4-point response scale (“strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) | 0.78 |

| Relational commitment | 0 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.49 | Sometimes I have doubts that my relationship with my partner will last | Agree vs disagreeC | NA |

| Socio-demographic variables | |||||||

| Male | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.46 | What is your sex? | Male, female | NA |

| Age | 18 | 25 | 20.1 | 1.69 | How old are you? | Age in number of years | NA |

Reverse coded

Responses have been recoded, not reflecting the original response from the survey.

Two survey items were combined.

An exploratory factor analysis had been performed prior to constructing the variable

Source: International Dating Violence Study

Dating violence victimization

Table 3 presents the findings from our multiple regression analyses. Overall, a history of childhood neglect and witnessing domestic violence were detrimental to the participants’ relational outcomes as victims (Model 1). Specifically, for every unit increase in the history of childhood neglect scale, reported physical victimization increased by 0.06 units (p<0.01). Having witnessed domestic violence was associated with 0.64 units increase in physical aggression for victims (p <0.01). Conversely, experience of childhood corporal punishment was not significantly associated with physical victimization. Regarding family social structure, the participants coming from a two-parent household, on average, reported a decrease of 0.31 units in physical victimization. Parental education, however, were not significantly associated with victimization. The majority of the variables that assessed relationship dynamics were statistically significant with respect to the participants’ experience of dating violence as victims. Specifically, the higher the level of couple conflict, the greater likelihood that the participant would experience physical victimization (b = 0.06, p<0.01). Further, the participants who experienced greater distress in their dating relationship were more likely to encounter physical victimization (b =0.04, p<0.05). So were those who were more likely to exert dominance in their dating relationship (b = 0.10, p <0.01). The participants who experienced psychological aggression as victims were also more likely to face physical aggression (b = 0.26, p < 0.001). On average, male college students were more likely than their female counterparts to be a victim of dating violence (b = 0.34, p<0.05).

Table 3.

Multiple regression analyses with experiencing and imposing physical aggression as the dependent variables.

|

Model 1 (Victim) |

Model 2 (Perpetrator) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | b(SE) | 95% CI | b(SE) | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 1.451 (0.910) | −0.328 – 3.230 | 2.523 (0.908)** | 0.744 – 4.302 |

| Early socialization | ||||

| Encountered childhood neglect | 0.063 (0.023)** | 0.018 – 0.107 | 0.070 (0.023)** | 0.026 – 0.115 |

| Experienced corporal punishment | 0.148 (0.143) | −0.133 – 0.429 | 0.181 (0.144) | −0.100 – 0.463 |

| Witnessed domestic violence | 0.642 (0.212)** | 0.227 – 1.057 | 0.763 (0.212)*** | 0.348 – 1.178 |

| Family social structure | ||||

| Two-parent household | −0.314 (0.134)* | −0.576 – −0.051 | −0.386 (0.134)** | −0.649 – −0.123 |

| Father’s education | −0.008 (0.025) | −0.056 – 0.041 | −0.019 (0.025) | −0.067 – 0.029 |

| Mother’s education | −0.028 (0.025) | −0.077 – 0.022 | −0.026 (0.025) | −0.075 – 0.024 |

| Relational dynamics | ||||

| Couple conflict | 0.062 (0.019)** | 0.024 – 0.099 | 0.048 (0.019)* | 0.011 – 0.085 |

| Relationship distress | 0.043 (0.017)* | 0.009 – 0.077 | 0.018 (0.017) | −0.015 – 0.052 |

| Dominance | 0.104 (0.037)** | 0.031 – 0.177 | 0.171 (0.037)*** | 0.099 – 0.244 |

| Psychological aggression (victim) | 0.264 (0.010)*** | 0.244 – 0.284 | - | - |

| Psychological aggression (perpetrator) | - | - | 0.286 (0.010)*** | 0.266 – 0.306 |

| Hostility to women | 0.025 (0.025) | −0.025 – 0.075 | −0.003 (0.025) | −0.053 – 0.047 |

| Relational commitment | −0.103 (0.145) | −0.387 – 0.180 | 0.134 (0.145) | −0.150 – 0.418 |

| Socio-demographic variables | ||||

| Male | 0.337 (0.137)* | 0.068 – 0.605 | −0.190 (0.138) | −0.460 – 0.081 |

| Age | −0.031 (0.036) | −0.102 – 0.040 | −0.071 (0.036)* | −0.142 – −0.000 |

refers to p< 0.05

refers to p< 0.01

refers to p< 0.001

Source: International Dating Violence Study

b=unstandardized coefficients; SE=standard errors; CI=confidence interval of b’s

Note: This table presents regression models with unstandardized coefficients, standard errors, and 95% confidence interval. Standard errors are in parentheses.

N=3,495

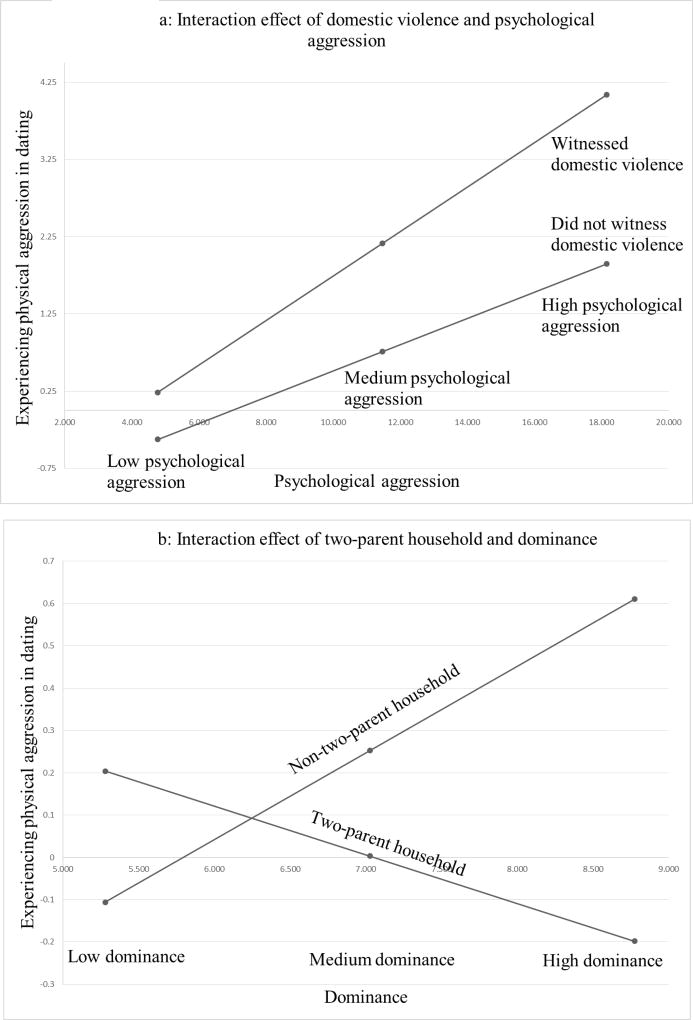

We also examined the interaction effects between the early socialization, family social structure, and relationship dynamics variables. Figure 1 illustrates the associations which were statistically significant at the bonferroni p-value (i.e., 0.0008) (see also Table 4). Figure 1a depicts the interaction effect of witnessing domestic violence as a child and encountering psychological aggression in dating on physical aggression in the victim model. Specifically, for the participants who faced greater levels of psychological aggression, witnessing domestic violence as a child was associated with greater physical victimization in dating. Figure 1b illustrates that among the participants who experienced higher levels of dominance in dating, the participants who came from a two-parent household experienced lower levels of physical victimization in dating. No other interaction terms were statistically significant at the adjusted p value.

Figure 1.

a: Interaction effect of domestic violence and psychological aggression

b: Interaction effect of two-parent household and dominance

Table 4.

Interaction effects (victim model).

|

Early socialization (Childhood neglect) |

Early socialization (Corporal punishment) |

Early socialization (Domestic violence) |

Family social structure (Two-parent housthold) |

Family social structure (Father’s education) |

Family social structure (Mother’s education) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables of interaction term | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) |

| Family social structure | ||||||

| Two-parent household | −0.046 (0.046) | −0.369 (0.300) | −0.265 (0.438) | - | - | - |

| Father’s education | −0.001 (0.009) | 0.029 (0.056) | 0.066 (0.078) | - | - | - |

| Mother’s education | −0.006 (0.009) | 0.006 (0.057) | −0.082 (0.081) | - | - | - |

| Relational dynamics | ||||||

| Couple conflict | 0.009 (0.006) | −0.042 (0.043) | 0.083 (0.057) | 0.088 (0 .041)* | −0.005 (0.007) | 0.001 (0.007) |

| Relationship distress | 0.006 (0.005) | −0.012 (0.040) | −0.089 (0.053) | −0.037 (0.037) | −0.012 (0.007) | 0.005 (0.007) |

| Dominance | 0.005 (0.012) | −0.029 (0.084) | −0.122 (0.118) | −0.320 (0 .080)***B | 0.014 (0.015) | −0.009 (0.015) |

| Psychological aggression (victim) | 0.011 (0.003)** | 0.029 (0.024) | 0.118 (0.033)***B | −0.036 (0.022) | 0.006 (0.004) | −0.010 (0.004)* |

| Hostility to women | 0.001 (0.008) | 0.060 (0.056) | 0.003 (0.077) | 0.012 (0.054) | −0.014 (0.010) | 0.005 (0.010) |

| Relational commitment | −0.008 (0.047) | 0.177 (0.332) | 0.013 (0.491) | 0.043 (0.313) | 0.061 (0.058) | −0.003 (0.058) |

refers to p< 0.05

refers to p< 0.01

refers to p< 0.001

refers to p< the Bonferroni corrected p-value

Dating violence perpetration

As in Model 1, victims of childhood neglect and domestic violence were more likely to impose physical aggression on their dating partners (b=0.07, p<0.01 and b=0.76, p<0.001 respectively). Compared to the participants who did not come from a two-parent household, the participants whose parents were married scored 0.39 units lower in their physical aggression scale of dating (p<0.01). With respect to dating relationship dynamics, only couple conflict and dominance attitudes had a statistically significant association with violence perpetration in dating. In particular, for every unit increase in the relational conflict or dominance scale, the participants scored 0.05 and 0.17 units higher respectively in the physical aggression scale (p<0.05 and p<0.001 respectively). Similarly, the participants who imposed psychological aggression were also more likely to inflict physical aggression (b=0.29, p<0.001). While gender had no statistically significant influence on perpetration, the likelihood of imposing physical aggression reduced with every birthday (b = −0.07, p<0.05).

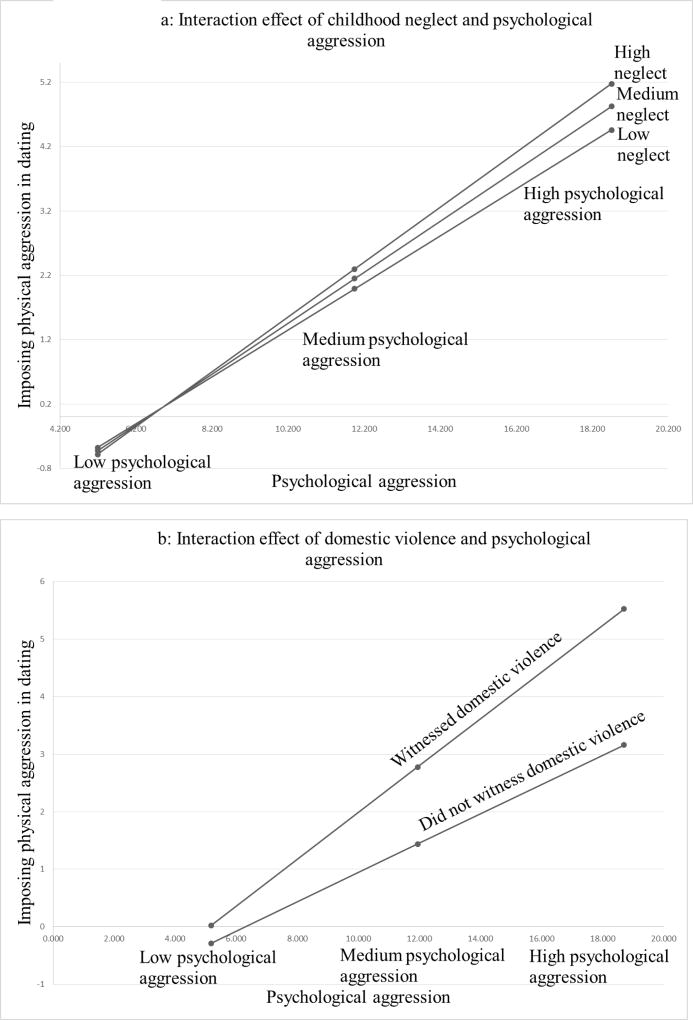

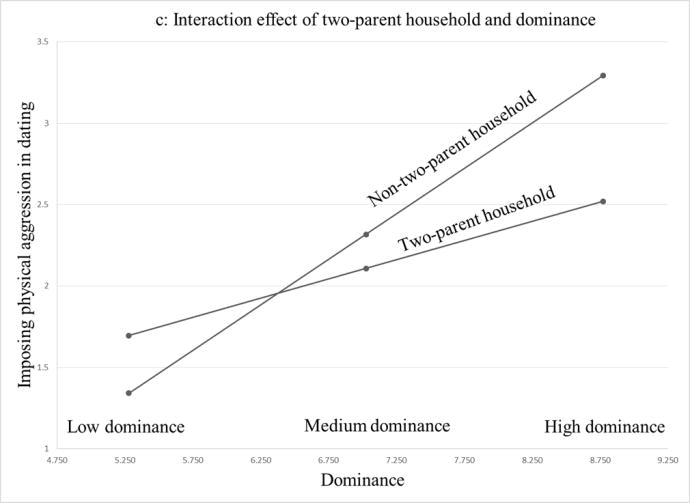

We found that adverse early socialization tended to intensify the negative influence of perpetration in dating but the effects were contingent upon the variables with which they interacted. In Figures 2a, the effect of psychological aggression tended to be greater on dating violence perpetration for the participants who experienced higher levels of childhood neglect. Similarly, according to Figure 2b, imposing higher levels of psychological aggression in dating was associated with greater levels of dating perpetration for the participants who acknowledged witnessing domestic violence during their childhood. The influence of psychological aggression on dating violence perpetration tended to be smaller for the participants who did not witness domestic violence. Figure 2c suggested that higher levels of dominance were associated with dating perpetration but the effect was minimized for the participants who came from a two-parent household (see Table 5). Other interaction terms were not statistically significant at the bonferroni p-value (i.e., 0.0008).

Figure 2.

a: Interaction effect of childhood neglect and psychological aggression

b: Interaction effect of domestic violence and psychological aggression

c: Interaction effect of two-parent household and dominance

Table 5.

Interaction effects (perpetrator model)

|

Early socialization (Childhood neglect) |

Early socialization (Corporal punishment) |

Early socialization (Domestic violence) |

Family social structure (Two-parent household) |

Family social structure (Father’s education) |

Family social structure (Mother’s education) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) | b(SE) |

| Family social structure | ||||||

| Two-parent household | 0.006 (0.046) | −0.324 (0.298) | −0.385 (0.435) | - | - | - |

| Father’s education | 0.004 (0.009) | −0.016 (0.056) | 0.148 (0.078) | - | - | - |

| Mother’s education | −0.014 (0.009) | 0.062 (0.056) | −0.198 (0.080)* | - | - | - |

| Relational dynamics | ||||||

| Couple’s conflict | 0.009 (0.006) | −0.001 (0.042) | 0.098 (0.057) | 0.073 (0.041) | −0.001 (0.007) | −0.002 (0.007) |

| Relationship distress | 0.005 (0.005) | −0.049 (0.039) | −0.175 (0.052)** | −0.038 (0.037) | −0.014 (0.007)* | 0.004 (0.007) |

| Dominance | −0.001 (0.012) | −0.078 (0.084) | 0.053 (0.118) | −0.323 (0.079)***B | 0.003 (0.014) | −0.015 (0.015) |

| Psychological aggression | 0.010 (0.002)***B | 0.010 (0.023) | 0.152 (0.033)***B | −0.061 (0.021)** | 0.002 (0.004) | −0.008 (0.004)* |

| Hostility to women | −0.009 (0.008) | 0.096 (0.055) | 0.031 (0.077) | −0.005 (0.054) | −0.015 (0.010) | 0.012 (0.010) |

| Relational commitment | −0.006 (0.046) | 0.258 (0.330) | 0.379 (0.488) | −0.160 (0.311) | 0.029 (0.057) | 0.018 (0.058) |

refers to p< 0.05

refers to p< 0.01

refers to p< 0.001

refers to p< the Bonferroni corrected p-value

Discussion

In 1981, Makepeace, in his controversial article, estimated that more than 1 in 5 college students had first-hand experience with courtship violence and many more had knowledge of others who engaged in this type of violence (Makepeace, 1981). Since then, IPV research conducted in the last three decades has put forth numerous theoretical explanations to shed light on various aspects triggering intimate violence among this subpopulation. Unfortunately, dating violence, which has become a pervasive social concern for emerging adults attending college, has not declined. While evidence has implicated risk factors stemming from early socialization, family social structure, and relationship dynamics as potential threats for “fostering” dating violence, few studies have examined these factors concurrently among college students, and none has focused on how these factors may interact. To address this apparent urgency, we examined the influence of early socialization, family social structure, and relationship dynamics on young college students’ experience of physical dating violence victimization and perpetration in the U.S. Additionally, we were interested in exploring the potential interaction effects of these factors.

Dating violence victimization

Overall, we found that experience of childhood neglect and having witnessed domestic violence were highly predictive of victimization in dating. These findings are supportive of growing evidence stressing the detrimental effect of childhood maltreatment in perpetuating an intergenerational cycle of violence (e.g., Cannon et al., 2009; Eriksson & Mazerolle, 2015). Although the risks may vary considerably, childhood neglect has been linked to several adverse outcomes correlated with dating victimization: insecure attachment style (Bifulco et al., 2006), poor mental health (e.g., PTSD, depression) (Nikulina, Widom, & Czaja, 2011), and substance abuse disorders (Hughes, McCabe, Wilsnack, West, & Boyd, 2010). In conjunction with its profound implications on the victims’ physiological functioning and cognitive development, witnessing family violence predisposes an individual to negative self-perception, reinforces passiveness toward abuse, and discourages capacity/motivation to overcome adversity. Other emotional difficulties including low self-esteem, feelings of anger, sadness, and powerless have also been documented. Walker (1979) introduced the condition of “battered women syndrome” using the concept of “learned helplessness” to explain the post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms exhibited by women who have experienced prolonged abuse from their partner. Given that learned helplessness from childhood exposure to family violence threatens individuals’ locus of control, social maladjustment, another reality which is prevalent among victims, may increase their susceptibility of becoming victimized in dating (Walker, 1983). As such, incorporating concepts of trauma-informed care into dating violence prevention interventions for college students may be necessary to mitigate the impact of these adverse early socialization experiences (Washaw, Sullivan & Rivera, 2013).

With respect to family social structure, our study found that living in a two-parent household appeared to exert a protective effect in dating victimization, although associations with parental educational level were not statistically significant. These findings offer some support to studies affirming the importance of family stability, parental supervision, and economic resources in preventing dating violence (Craigie, Brooks-Gunn, & Waldfogel, 2012; Sun & Li, 2011). Children from two-parent households may enjoy greater parent-child closeness as Bjarnason et al. (2012) found that children from two-parent households reported greater life satisfaction compared to children from single parent families. Other research that examines variation in outcomes among children reared in single parent households also revealed that single parent family structure occupies a more disadvantaged economic and social position relative to other types of household structure (see Thomson & McLanahan, 2012). Perhaps, it is not the level of parental education that matters but the quality of parenting, as many studies have highlighted the importance of quality parental monitoring behaviors and family socialization in preventing dating violence (e.g., Kochanska et al., 2010; Ooi, Ang, Fung, Wong, & Cai, 2006).

Overall, we also found that the participants were more likely to experience victimization in dating relationships which were characterized by conflicts, distress, dominance, or psychological aggression. From the social exchange perspective, couple’s appraisal of conflict and distress may “depreciate” the value of courtship preservation (see Sabatelli, 1988). On the other hand, abuse related shame can provoke victimization through anger (Feiring, Simon, Cleland, & Barrett, 2013). Proponents of the feminist theory contended that gender inequality, traditional sex role attitudes, and social acceptance of violence put women at greater risk for victimization. Specifically, partner victimization is found to be more prevalent among couples with highly imbalanced power structure and non-egalitarian practices (Anderson, 1997; McCloskey et al, 2005; Shannon et al., 2012). Further, while psychological aggression has been identified as one of the most prevalent precursors or predictors of dating violence (Baker & Stith, 2008), empirical support indicated that psychological aggression in dating and PTSD may occur through anger arousal (Taft, Schumm, Orazem, Meis, & Pinto, 2010), another possible indication that psychological aggression may be mediated by a range of negative emotions. We recommend that public health interventions target norms and attitudes that reduce adherence to unhealthy gender stereotypes and provide skills-training for effective communication, conflict resolution, and anger management to guide college students who are seeking help in order to decrease their risk of dating violence. The finding that male participants were more likely to experience physical dating violence victimization than females mirrors findings from other studies with college students (Cercone, Beach, & Arias, 2005; Kaukinen, Gover, & Hartman, 2012). Some IPV scholars, however, caution a more conservative interpretation of this finding since females still sustain a greater risk of injury compared to their male counterparts (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). Taken together, these findings reiterate the importance of targeting both male and female college students in dating violence prevention efforts and providing gender-neutral counseling and support services.

In exploring their interaction effects, we found that adverse early socialization (i.e., witnessing domestic violence) and positive family social structure (i.e., growing up in a two-parent household) appeared to intensify or mitigate the negative effect exerted by poor relational factors (i.e., experiencing psychological aggression and dominance) on victimization respectively. We speculate that protection from childhood adversity might reinforce resilience that protected some of the participants from victimization in dating. Unlike the participants who were exposed to family violence, those who have not had such exposure might have grown up in a household where positive interpersonal interactions were stressed and negative communication or aggression were frowned upon. It is also possible that the capacity of family to shield the participants from future victimization increased when two parents (rather than one) worked together to invest resources, serve as role models, and monitor their children’s behaviors. Thus, incorporating family support into dating violence prevention programs may help strengthen students’ social support systems which has been shown to prevent, or mediate the adverse effects of college dating violence (Kaukinen, 2014).

Dating violence perpetration

With respect to dating violence perpetration, our study shows that encountering childhood neglect and domestic violence were associated with dating violence perpetration consistent with existing findings from college dating and child maltreatment literature (e.g., Arriaga & Foshee, 2004, Carr & Vandeusen, 2002, Lichter & McCloskey, 2004). By contrast, unlike previous studies (e.g., Douglas & Straus, 2006; Lavoie et al., 2002), we did not find statistically significant associations between early experience of corporal punishment or harsh parenting with dating violence. Support for these findings may stem from several explanations. Childhood neglect is known to lead to dysfunctional attachment styles, social incompetence, and greater relational challenges (e.g., less positive perception about current romantic partner, greater likelihood of walking out of a relationship, higher rates of divorce, and lesser likelihood to remain sexually faithful) (Colman & Widom, 2004). From the developmental perspective, a number of studies asserted that exposure to domestic violence foster emotional distress, behavioral disengagement, bullying behaviors, and aggressiveness (see Holt, Buckley, & Whelan, 2008). In a longitudinal study, Tschann et al. (2008) posited that parental management of disagreement (a nonviolent aspect of interparental discord) and physical aggression (a violent form of conflict) can shape adolescents and young adults’ conflict management strategies in romantic relationships. Additionally, besides internalizing violence and acquiring behaviors that facilitate hostility, social learning theorists allege that physical aggression, which often escalates from nonviolent conflict resolution, conveys the message that violence is a reasonable tool to minimize differences in an conflict-laden environment (Cannon, Bonomi, Anderson, & Rivara, 2009; Eriksson & Mazerolle, 2015).

With regards to family social structure, our study found that participants from a two-parent household were less likely to impose physical aggression on their dating partner. Unlike single parent households, national data indicate that two-parent households enjoy relatively higher income and greater social support in the realm of parenting (Kendig & Bianchi, 2008, Laughlin, 2014). Using two-parent households as a point of comparison, empirical evidence reveals that criminal and delinquent outcomes were found to be more prevalent among children raised by a lone parent (Eitle, 2006; Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2007; McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994). Children growing up in single parent households, for example, were more at risk of a range of risky behaviors such as smoking, drinking alcohol, engaging in weapon-related violence, and sexual intercourse (Blum et al., 2000). Some of these behaviors may set the precedent for dysfunctional dating behaviors (e.g., Brendgen, Vitaro, Tremblay, & Wanner, 2002). These differences in outcomes may be a function of differences in family process related to parental supervision, monitoring, relationship closeness, and frequency of quality interactions.

In our study, couple conflict, dominance attitudes, and psychological aggression were found to be associated with dating violence perpetration. Like victimization, these three aspects of relationship dynamics present an interpersonal context and normative extension that can lead to physical aggression in part because they contribute to poor relational quality and evoke aggression when constructive conflict resolutions failed (e.g., Bell & Naugle, 2008; Taft et al., 2010). Gender was non-significant with regards to dating violence perpetration. We suspect that male students might be less likely to report perpetration since it is less acceptable for men to hit women in the U.S. culture. Given that younger students were at greater risk for dating violence perpetration, implementing dating violence prevention programs during freshman orientation or required freshman classes may enhance prevention efforts.

With respect to interaction effects, we found that while dysfunctional early socialization (i.e., experiencing childhood neglect and witnessing domestic violence) were associated with adverse dating outcomes, positive family structure (i.e., two-parent household structure) could serve as protective factors for the participants who imposed physical aggression in dating. The participants’ relation with their dating partner might be shaped by their self-reflected appraisals of childhood socialization, cultural upbringing, and structural position of their family of origin. In this study, we found that the participants who reported lower levels of childhood neglect fared better than their counterparts who experienced greater levels of childhood neglect. Similarly, the participant group who did not witness domestic violence or came from a two parent household was less susceptible to imposing physical aggression in dating compared to their counterparts when they were assessed at higher levels of poor relational dynamics. We suspect that several explanations are plausible. First, given that their parents were married, the participants might have more confidence in seeking help on relational issues from their parents. In that case, the participants from a two-parent household could turn to their parents for guidance, consultation, and comfort when dating went sour. Second, given the household’ greater resources, parents can work collaboratively to intervene, prevent tragedies caused by dating perpetration, or obtain professional help if necessary. Third, the participants from a two-parent household might adopt more constructive strategies to keep their dating partner rather than resorting to violence since their parents have made it over the years. Overall, these findings supported the claim that both risk and protective factors could aggravate or build resilience but these relationships were contingent upon the ecological settings where these factors were embedded.

Concluding remarks

Taken together, family and relational variables associated with victimization and perpetration of physical aggression in dating relationships among college students were fairly similar. To fully understand the dynamics of dating violence in this population, we recommend that future research moves beyond the traditional one-way mode of assessing either dating violence victimization or perpetration, and examine the bidirectional or reciprocal nature of violence whenever feasible. It is also vital to explore different types of family and relational variables concurrently and how they interact, given there is limited number of studies designed to curtail this empirical gap. Further, we urge that practitioners working with college students at risk of intimate partner violence explore the potential for adverse childhood experience if necessary. If we can identify college men and women who may be vulnerable to abuse and victimization, we can secure a better chance in preventing the occurrence of dating violence behaviors. Outside of the post-secondary educational settings, Cook et al. (2005) advocated the use of a systemic approach that entails intervention with family systems, service delivery systems, and therapy sessions emphasizing safety, self-regulation, meaningful self-narrative, relationship reconstruction, healthy attachments, and self-enhancement to confront trauma due to child maltreatment.

Thus far, our study has highlighted the need to instill knowledge on fostering positive couple interaction, in particular, for college students who may be at greater risk for dating violence in their current dating relationship. Lastly, our findings emphasize the significance of understanding the underlying interactive mechanisms of early socialization, family structure, and relationship dynamics. Clearly, the influence of risk and protective factors on college dating violence could differ contingent upon the family or relational variables that interact. As such, we highly discourage any research or treatment effort that adopts a “one size fits all” approach in their model formulation but embrace the concepts of diversity in their research and practice approach.

Limitations to the study

While this study adds to the current literature, some limitations must be noted. Cross-sectional analysis limits our ability to offer causal inference. This is particularly true when examining the directionality between current relationship dynamics and dating violence victimization and perpetration. However, examining associations and interactions with other factors may generate hypotheses for future longitudinal studies. Further, violence in the college context may be qualitatively different from other samples of emerging adults since college students are more likely to represent a middle class populations. Additionally, some participants may have been reluctant to report violent perpetration due to social desirability issue. Finally, while this study claims no generalizability to dating couples or college students in general, our research findings, which help shed light on the family and relational factors underlying physical dating violence in this emerging adult population, can be used to guide the development of more effective college dating violence prevention interventions and promote healthier intimate relationships in the older adult years.

Acknowledgments

This study effort was supported by the UTEP BUILDing SCHOLARS NIH Award # 1RL5MD009592

Footnotes

The dataset is made available for public use by the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/

Approximately 17,404 were surveyed, but only 14,252 were at some point in a dating relationship.

Courses on family violence were not included (Straus, 2004a).

Only participants who had a dating relationship lasted one month or more were included because those without were not required to complete questions pertaining to the Conflict Tactics Scales.

There are k of them in this equation.

Contributor Information

Yok-Fong Paat, Department of Social Work, The University of Texas at El Paso, USA.

Christine Markham, Center for Health Promotion and Prevention Research, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, Texas.

References

- Akers RL, Sellers CS. Criminological theories: Introduction, evaluation, and application. 5. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Allen M, Devitt C. Intimate partner violence and belief systems in Liberia. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(17):3514–3531. doi: 10.1177/0886260512445382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amar AF, Gennaro S. Dating violence in college women: Associated physical injury, healthcare usage, and mental health symptoms. Nursing Research. 2005;54(4):235–242. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KL. Gender, status, and domestic violence: An integration of feminist and family violence approaches. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1997;59(3):655–669. [Google Scholar]

- Antai D. Controlling behavior, power relations within intimate relationships and intimate partner physical and sexual violence against women in Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(511) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriage XB, Foshee VA. Adolescent dating violence: Do adolescents follow in their friends’, or their parents’, footsteps? Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(2):162–184. doi: 10.1177/0886260503260247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CR, Stith SM. Factors predicting dating violence perpetration among male and female college students. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2008;17(2):227–244. doi: 10.1080/10926770802344836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bariola E, Gullone E, Hughes EK. Child and adolescent emotion regulation: The role of parental emotion regulation and expression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(2):198–212. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrick K, Krebs CP, Lindquist CH. Intimate partner violence among undergraduate women at historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) Violence Against Women. 2013;19(8):1014–1033. doi: 10.1177/1077801213499243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belt KM, Naugle AE. Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: Moving towards a contextual framework. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(7):1096–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensley L, Van Eenwyk J, Simmons KW. Childhood family violence history and women’s risk for intimate partner violence and poor health. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24(12):1529–1542. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bifulco A, Kwon J, Jacobs C, Moran PM, Bunn A, Beer N. Adult attachment style as mediator between childhood neglect/abuse and adult depression and anxiety. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41(10):796–805. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0101-z. doi:7/s00127-006-0101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnason T, Bendtsen P, Arnarsson AM, Borup I, Iannotti RJ, Löfstedt P, Haapasalo I, Niclasen B. Life satisfaction among children in different family structures: A comparative study of 36 western societies. Children & Society. 2012;26(1):51–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2010.00324.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, Stevens MR. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blum RW, Beuhring T, Shew ML, Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Resnick MD. The effects of race/ethnicity, income, and family structure on adolescent risk behaviors. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(12):1879–1884. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Rivara FP, Thompson RS. Health care utilization and costs associated with physical and nonphysical-only intimate partner violence. Health Services Research. 2009;44(3):1052–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE, Wanner B. Parent and peer effects on delinquency-related violence and dating violence: A test of two mediational models. Social Development. 2002;11(2):225–244. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buelna C, Ulloa EC, Ulibarri MD. Sexual relationship power as a mediator between dating violence and sexually transmitted infections among college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(8):1338–1357. doi: 10.1177/0886260508322193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Vaeth PAC, Ramisetty-Mikler S. Intimate partner violence victim and perpetrator characteristics among couples in the United States. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23(6):507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JE, Swan SC, Woodbrown VD. Gender differences in intimate partner violence outcomes. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2(1):42–57. doi: 10.1037/a0026296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon EA, Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Rivara FP. The intergenerational transmission of witnessing intimate partner violence. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(8):706–708. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JL, Vandeusen KM. The relationship between family of origin violence and dating violence in college men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17(6):630–646. doi: 10.1177/0886260502017006003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S. Intimate partner violence, 1993–2010. Washington, DC: U.S Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice; 2012. (ncj 239203) [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo R, McLoyd VC. Social support and parenting in poor, dangerous neighborhoods. Child Development. 2002;73:1310–1321. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cercone JJ, Beach SRH, Arias I. Gender symmetry in dating intimate partner violence: Does similar behavior imply similar constructs? Violence and Victims. 2005;20(2):207–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Cloitre M, DeRosa R, Hubbard R, Kagan R, Liautaud J, Mallah K, Olafson E, van der Kolk B. Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35(5):390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Colman RA, Widom CS. Childhood abuse and neglect and adult intimate relationships: A prospective study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(11):1133–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corso PS, Mercy JA, Finkelstein EA, Miller TR. Medical costs and productivity losses due to interpersonal and self-directed violence in the United States. American. Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(6):474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigie T-AL, Brooks-Gunn J, Waldfogel J. Family structure, family stability, and outcomes of five-year-old children. Families, Relationships and Societies. 2012;1(1):43–61. doi: 10.1332/204674312X633153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz TL. Disciplining children: Characteristics associated with the use of corporal punishment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24(12):1529–1524. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas EM, Straus MA. Assault and injury of dating partners by university students in 19 countries and its relation to corporal punishment experienced as a child. European Journal of Criminology. 2006;3(3):293–318. doi: 10.1177/1477370806065584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra RE, Schumacher JA, Mota N, Coffey SF. Examining the role of antisocial personality disorder in intimate partner violence among substance use disorder treatment seekers with clinically significant trauma histories. Violence Against Women. 2015;21(8):958–974. doi: 10.1177/1077801215589377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitle D. The moderating effects of peer substance use on the family structure-adolescent substance use association: Quantity versus quality of parenting. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(5):963–980. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitle D. Parental gender, single-parent families, and delinquency: Exploring the moderating influence of race/ethnicity. Social Science Research. 2006;35(3):727–748. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2005.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8(3):430–457. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson L, Mazerolle P. A cycle of violence? Examining family-of-origin violence, attitudes, and intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;30(6):945–964. doi: 10.1177/0886260514539759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Simon VA, Cleland CM, Barrett EP. Potential pathways from stigmatization and externalizing behavior to anger and dating aggression in sexually abused youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(3):309–322. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.736083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood J. Exposure to single parenthood in childhood and later mental health, educational, economic, and criminal behavior outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(9):1089–1095. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias SM, Angel RJ. The risk of partner violence among low-income Hispanic subgroups. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(3):552–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00153.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gover AR, Kaukinen C, Fox KA. The relationship between violence in the family of origin and dating violence among college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(12):1667–1693. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guryan J, Hurst E, Kearney MS. Parental education and parental time with children. Cambridge, MA: The National Bureau of Economic Research; 2008. (NBER Working Paper No. 13993) [Google Scholar]

- Hanson TL, McLanahan S, Thomson E. Economic resources, parental practices, and children’s wellbeing. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. pp. 190–238. [Google Scholar]

- Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(8):797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ. Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction. 2010;105(12):2130–2140. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Kuffel SW, Coblentz A. Are there gender differences in sustaining dating violence? An examination of frequency, severity, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Violence. 2002;17(3):247–271. [Google Scholar]

- Kaukinen C. Dating violence among college students: The risk and protective factors. Truama, Violence, & Abuse. 2014;15(4):283–296. doi: 10.1177/1524838014521321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaukinen C, Gover AR, Hartman JL. College women’s experiences of dating violence in casual and exclusive relationships. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2012;37(2):146–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kendig SM, Bianchi SM. Single, cohabitating, and married mothers’ time with children. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70(5):1228–1240. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00562.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Woodard J, Kim S, Koenig JL, Yoon JE, Barry RA. Positive socialization mechanisms in secure and insecure parent-child dyads: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51(9):998–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers KK, van der Knaap LM, Winkel FW. Risk of revictimization of intimate partner violence: The role of attachment, anger and violent behavior of the victim. Journal of Family Violence. 2011;27(1):33–44. doi: 10.1007/s10896-011-9399-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin L. A child’s day: Living arrangements, nativity, and family transitions: 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2014. Current Population Reports P70-139. [Google Scholar]

- Lamanna MA, Riedmann A. Marriages, families, and relationships: Making choices in a diverse society. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie F, Hébert M. History of family dysfunction and perpetration of dating violence by adolescent boys: A longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30(5):375–383. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TK, Wickrama KAS, Simons LG. Chronic family economic hardship, family processes and progression of mental and physical health symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42(6):821–836. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9808-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter EL, McCloskey LA. The effects of childhood exposure to marital violence on adolescent gender-role beliefs and dating violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28(4):344–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00151.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Makepeace JM. Courtship violence among college students. Family Relations. 1981;30:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LA, Williams C, Larsen U. Gender inequality and intimate partner violence among women in Moshi, Tanzania. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2005;31(3):124–130. doi: 10.1363/3112405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Sandefur G. Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):185–204. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milletich RJ, Kelley ML, Doane AN, Pearson MR. Exposure to interparental violence and childhood physical and emotional abuse as related to physical aggression in undergraduate dating relationships. Journal of Family Violence. 2010;25(7):627–637. [Google Scholar]

- Nikulina V, Widom CS, Czaja S. The role of childhood neglect and childhood poverty in predicting mental health, academic achievement and crime in adulthood. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48(3):309–321. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9385-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi YP, Ang RP, Fung DSS, Wong G, Cai Y. The impact of parent-child attachment on aggression, social stress and self-esteem. School Psychology International. 2006;27(5):552–566. doi: 10.1177/0143034306073402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paat Y-F. The link between financial strain, interparental discord and children’s antisocial behaviors. Journal of Family Violence. 2011;26(3):195–210. doi: 10.1007/s10896-010-9354-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pflieger JC, Vazsonyi AT. Parenting processes and dating violence: The mediating role of self-esteem in low- and high-SES adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2006;29(2006):495–512. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnet K. Financial stress, parent functioning and adolescent problem behavior: An actor-partner interdependence approach to family stress processes in low-, middle-, and high-income families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43(10):1752–1769. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0159-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner LM, Whitney SD. Risk factors for unidirectional and bidirectional intimate partner violence among young adults. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36(1):40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roksa J, Potter D. Parenting and academic achievement intergenerational transmission of educational advantage. Sociology of Education. 2011;84:299–321. doi: 10.1177/0038040711417013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatelli RM. Exploring relationship satisfaction: A social exchange perspective on the interdependence between theory, research, and practice. Family Relations. 1988;37(2):217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Leiter K, Phaladze N, Hlanze Z, Tsai AC, Heisler M, Iacopino V, Weiser SD. Gender inequity norms are associated with increased male-perpetrated rape and sexual risks for HIV infection in Botswana and Swaziland. Plos One. 2012;7(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Brasfield H, Febres J, Stuart GL. The association between impulsivity, trait anger, and the perpetration of intimate partner and general violence among women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(13):2681–2697. doi: 10.1177/0886260510388289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotter EB, Finkel EJ, DeWall CN, Pond RS, Jr, Lambert NM, Bodenhausen GV, Fincham FD. Putting the brakes on aggression toward a romantic partner: The inhibitory influence of relationship commitment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102(2):291–305. doi: 10.1037/a0024915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. The Conflict Tactics Scales and its critics: An evaluation and new data on validity and reliability. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publications; 1990. pp. 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Cross-cultural reliability and validity of the revised conflict tactics scales: A study of university student dating couples in 17 nations. Cross-Cultural Research. 2004a;38(4):407–432. doi: 10.1177/1069397104269543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Prevalence of violence against dating partners by male and female university students worldwide. Violence against Women. 2004b;10(7):790–811. doi: 10.1177/1077801204265552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30(3):252–275. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Kinard EM, Williams LM. The Multidimensional Neglectful Behavior Scale, Form A: Adolescent and Adult-Recall Version. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire: Family Research Laboratory; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Savage SA. Neglectful behavior by parents in the life history of university students in 17 countries and its relation to violence against dating partners. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10(2):124–135. doi: 10.1177/1077559505275507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Ramirez IL. Gender symmetry in prevalence, severity, and chronicity of physical aggression against dating partners by university students in Mexico and USA. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33:281–290. doi: 10.1002/ab.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Li Y. Effects of family structure type and stability on children’s academic performance trajectories. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73(3):541–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00825.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Multiple regression. In: Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, editors. Using multivariate statistics. 3. NY: HarperCollins College Publishers, New York, NY; 1996. pp. 709–811. [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Schumm J, Orazem RJ, Meis L, Pinto LA. Examining the link between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and dating aggression perpetration. Violence and Victims. 2010;25(4):456–469. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.4.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Freeman DH., Jr Dating violence and substance use among ethnically diverse adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(4):701–718. doi: 10.1177/0886260510365858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Shorey RC, Tortolero SR, Wolfe DA, Stuart GL. Importance of gender and attitudes about violence in the relationship between exposure to interparental violence and the perpetration of teen dating violence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(5):343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson E, McLanahan SS. Reflections on “family structure and child well-being: Economic resources vs. parental socialization”. Social Forces. 2012;91(1):45–53. doi: 10.1093/sf/sos119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence and consequences of male-to-female and female-to-male intimate partner violence as measured by the National Violence Against Women Survey. Violence Against Women. 2000;6(2):142–161. doi: 10.1177/10778010022181769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Pasch LA, Flores E, Marin BV, Baisch EM, Wibbelsman CJ. Nonviolent aspects of interparental conflict and dating violence among adolescents. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;30(3):295–319. doi: 10.1177/0192513X08325010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanassche S, Sodermans AK, Matthijs K, Swicegood G. The effects of family type, family relationships and parental role models on delinquency and alcohol use among Flemish adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23(1):128–143. [Google Scholar]

- Walker LE. The battered woman. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Walker LE. The battered woman syndrome study. In: Finkelhor D, Gelles RJ, Hotaling G, Straus M, editors. The dark side of families: Current family violence research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1983. p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw C, Sullivan CM, Rivera EA. A systematic review of trauma-focused interventions for domestic violence survivors. National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health; 2013. Retrieved from http://www.nationalcenterdvtraumamh.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/NCDVTMH_EBPLitReview2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- West C. Black women and intimate partner violence: New directions for research. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(12):1487–1493. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]