Abstract

Multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli infections are a growing public health concern. This study analyzed the possibility of contamination of commercial poultry meat (broiler and free-range) with pathogenic and or multi-resistant E. coli in retail chain poultry meat markets in India. We analyzed 168 E. coli isolates from broiler and free-range retail poultry (meat/ceca) sampled over a wide geographical area, for their antimicrobial sensitivity, phylogenetic groupings, virulence determinants, extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL) genotypes, fingerprinting by Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus (ERIC) PCR and genetic relatedness to human pathogenic E. coli using whole genome sequencing (WGS). The prevalence rates of ESBL producing E. coli among broiler chicken were: meat 46%; ceca 40%. Whereas, those for free range chicken were: meat 15%; ceca 30%. E. coli from broiler and free-range chicken exhibited varied prevalence rates for multi-drug resistance (meat 68%; ceca 64% and meat 8%; ceca 26%, respectively) and extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) contamination (5 and 0%, respectively). WGS analysis confirmed two globally emergent human pathogenic lineages of E. coli, namely the ST131 (H30-Rx subclone) and ST117 among our poultry E. coli isolates. These results suggest that commercial poultry meat is not only an indirect public health risk by being a possible carrier of non-pathogenic multi-drug resistant (MDR)-E. coli, but could as well be the carrier of human E. coli pathotypes. Further, the free-range chicken appears to carry low risk of contamination with antimicrobial resistant and extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC). Overall, these observations reinforce the understanding that poultry meat in the retail chain could possibly be contaminated by MDR and/or pathogenic E. coli.

Keywords: food borne pathogens, poultry, antibiotic resistance, zoonosis, whole genome sequencing

Introduction

The rapid global rise of Escherichia coli infections that are resistant to therapeutically important antimicrobials, including first-line drugs such as cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones, is of serious concern, as it hampers treatment of infections leading to significant morbidity, mortality, medical costs as well as production losses in livestock (de Been et al., 2014). E. coli is responsible for infections in humans and animals; these could be nosocomial and/or community-acquired (Jadhav et al., 2011). Being part of the endogenous microbiota, E. coli can easily acquire resistance against antimicrobials consumed by humans and animals (van den Bogaard et al., 2001).

Poultry are recognized as important source for dissemination of antimicrobial resistant E. coli in the community and environment (van den Bogaard et al., 2001). Pathogenic E. coli in poultry are a direct threat to both poultry industry and human health as they may result in hard-to-treat infections (Kaper et al., 2004). Extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC), the causative agent of colibacillosis in chickens inflict severe losses due to morbidity and condemnations (Kaper et al., 2004). ExPEC can also cause several extraintestinal diseases in humans, including urinary tract infections, neonatal meningitis, and sepsis (Avasthi et al., 2011; Hussain et al., 2012; Nandanwar et al., 2016; Ranjan et al., 2017). Apart from ExPEC, the poultry gut could also harbor other variants of intestinal pathogenic E. coli (Lutful Kabir, 2010). Recent studies in different parts of India have reported antimicrobial residues in food animal products such as milk and chicken meat, indicating that antimicrobial usage is widespread in food animal production (Laxminarayan and Chaudhury, 2016). Such practices lead to high proportion of antibiotic resistant bacteria in their fecal microbiota (Chen and Jiang, 2014). Consequently, meat at slaughtering operations can be extensively contaminated with fecal E. coli of poultry origin (Lutful Kabir, 2010).

The ExPEC pathotype that is isolated from poultry with clinical signs of extraintestinal infections is known as avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) (Kaper et al., 2004). Although research has been mainly focused on infections caused by APEC pathotype, little is known about the reservoirs of these bacteria (Bélanger et al., 2011). Also, many human and animal ExPEC isolates share virulence genes and clonal backgrounds and the human health risk posed by such bacteria from poultry is still largely undefined (Dziva et al., 2013). Moreover, the pathotype APEC itself is ill-defined (Collingwood et al., 2014). One study even suggested that an APEC strain showed high genome similarity to human enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) (Dziva et al., 2013). Therefore, the question of whether fecal isolates of poultry serve as a source of infection for extraintestinal and intestinal infections in humans remains unanswered. Recent investigations compared E. coli from symptomatic poultry and human ExPEC by virulence genotyping, serotyping and in vitro assays (Nandanwar et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2015). However, the application of high-resolution, whole genome sequencing methods appears to be superior and is likely to provide accurate insights into the phylogenetic backgrounds of poultry E. coli and would likely highlight the similarities between isolates of different human pathotypes (de Been et al., 2014).

The presence of antimicrobial resistant bacteria in food has been attributed to the widespread use of antimicrobials in farming practices (Landers et al., 2012; Qumar et al., 2017). Currently, few data are available regarding the contamination of retail foods with E. coli, especially those that are multi-resistant and pathogenic (Zhang et al., 2011). Also, little is known about the frequency of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms in poultry that were raised by free-range farming as methods of livestock production differ in antibiotic usage practices (Brower et al., 2017). Therefore, the main aim of this study was to estimate the frequencies of contamination with pathogenic and/or multi resistant E. coli among broiler and free-range chicken specimens (ceca and meat) and to characterize the E. coli isolates recovered from them in relation to the human E. coli pathotypes. Results of this study reinforces the importance of One Health approach in addressing the spread of antimicrobial resistance and emerging infections.

Materials and Methods

Specimen Collection

Between February, 2015 to September, 2015, 22 poultry retail outlets were sampled from four cities representatives of four different states of India: Karnataka (n = 35), Telangana (n = 59), Andhra Pradesh (n = 15) and Maharashtra (n = 11); this resulted in a total of 120 samples. A total of 75 poultry ceca, entailing broiler and free-range chicken (39 and 36, respectively) together with 45 raw meat samples, representing broiler and free-range chicken (32 and 13, respectively) were obtained from retail poultry outlets. From each shop, multiple samples (different birds) were procured. Samples were transported to laboratory in cooled boxes (4–8°C) and upon arrival were stored at 4°C and processed within 24 h.

Broiler represented commercial broiler chickens that were conventionally raised in farms and fed with commercial feeds; free-range poultry birds were country (native) chickens that were raised in households and small backyard farms that grew by free-ranging.

Culture Methods

All cecal samples were surface sterilized with 70% ethanol and a portion (∼25 g) was incised and placed in a 1.5 ml micro-centrifuge tube containing Luria Bartani (LB) broth. Similarly, around 25 g of raw meat was excised from each sample and rinsed with 1X PBS and the sample was placed in a Petri dish containing 1 ml LB broth and minced into small pieces. Each cecum and chicken sample was taken out of the LB broth and swabbed on the edge of the plate and then spread with a loop, this was done on two separate agar plates; one on unsupplemented Eosin Methylene Blue (EMB) agar plate, and another on EMB agar supplemented with 10 μg/ml ciprofloxacin together with 4 μg/ml cefotaxime (this was used to increase the chance of ST131 E. coli isolation). All plates were incubated at 37°C for 12 h. One putative E. coli was selected from each culture plate, which was then confirmed by standard biochemical methods. All E. coli isolates were preserved in 20% glycerol-supplemented Luria-Bertani broth at -80°C.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility, ESBL Confirmation, and ESBL Gene Detection

Antimicrobial susceptibility toward fosfomycin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, co-trimoxazole, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol belonging to six different antibiotic classes was assessed by standard disk diffusion method as per CLSI guidelines (Schissler et al., 2009; Hussain et al., 2014). ESBL production was determined using double-disk synergy test following CLSI guidelines (CLSI, 2013). Phenotypically confirmed ESBL-producers were analyzed for the presence of genes encoding CTX-M-15 and that of blaSHV, and blaTEM genes by three gene specific PCRs (Ranjan et al., 2015).

As the EMB agar plates (i.e., with or without antibiotic supplement) were streaked using an identical inoculum, the percentage of resistance/susceptibility to different antibiotics was determined in relation to the total E. coli population.

Phylogenetic Groups, Virulence Genotyping, ST131 Detection, and Enterobacterial Intergenic Repetitive Element Sequences (ERIC)-PCR

Phylogenetic groups of E. coli isolates were determined by quadruplex PCR and by employing the criteria as described by Clermont et al. (2013). All isolates were screened for the presence of the following five ExPEC genes (Hussain et al., 2014); papC (P fimbriae), sfa (s fimbriae), afa (afimbrial adhesin), aer (siderophore related protein), and cvaC (protectin). The criteria elaborated by Johnson et al. (2003) were used to classify E. coli isolates as ExPEC with some modifications. All E. coli isolates were screened for ST131 gene specific PCR as described elsewhere (Hussain et al., 2014). ERIC-PCR based fingerprint analysis was performed as described in our earlier study (Hussain et al., 2014). The ERIC-PCR bands obtained were analyzed using BioNumerics software (Applied Maths, Belgium) (Hussain et al., 2014).

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) and Comparison with Human E. coli Pathotypes

Paired end sequencing of the 10 genetically distinct (based on ERIC bands), and randomly selected MDR-ESBL producing poultry E. coli (seven cecum and three meat) isolates was carried out using Illumina MiSeq. The accession numbers of 10 poultry E. coli genomes including their genomic features are represented in Supplementary Tables S1 and S4. Paired end read data were filtered for high quality reads followed by de novo assembly using NGS QC Toolkit (v2.3.3) (Patel and Jain, 2012) and SPAdes Genome Assembler (v3.6.1) (Bankevich et al., 2012), respectively. The de novo contigs thus generated were ordered and scaffolded using Contig-Layout-Authenticator (Shaik et al., 2016). Final draft genomes were obtained by merging the scaffolds using a series of N’s and then submitted to the RAST (Overbeek et al., 2014) server for annotation. The genome statistics were gleaned using ARTEMIS (Rutherford et al., 2000). The sequence type (ST) of each of these strains were determined by in silico MLST as used/described elsewhere (Ranjan et al., 2015). Mobile genetic elements as reported in the ExPEC strain EC958 (Totsika et al., 2011) were used as reference to compare the 6 E. coli genomes using BRIG (Alikhan et al., 2011). A core-genome-based phylogenetic tree of 50 E. coli strains (10 in house poultry E. coli genomes, 10 healthy broiler chicken E. coli genomes from public sources, 10 APEC, 10 ExPEC and 10 enteric pathogens) (Supplementary Tables S1 and S3) was constructed using Harvest (Treangen et al., 2014) and the resulting tree was visualized using iTol1. Virulence and Resistance profiles of these 50 strains were generated and hierarchical clustering was performed using the gplot package of R as described/used by us before (Ranjan et al., 2016).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis for prevalence of antimicrobial resistance, phylogenetic groups, ESBL and virulence genes were carried out using Fisher’s exact two-tailed test. Statistical analyses for aggregate resistance and virulence scores were carried out using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test. Both the tests were implemented in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 10.0). P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Over Half of the Chicken Meat Samples Were Contaminated with E. coli

A total of 168 E. coli isolates were recovered from 120 poultry samples using both unsupplemented and antibiotic supplemented (ciprofloxacin-plus-cefotaxime) EMB agar, encompassing 105 and 63 isolates, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). Out of the 32 and 13 raw meat samples from broiler and free-range chicken, 29 (91%) and 11 (84%) were contaminated with E. coli, respectively. Further, compared to broiler chicken meat (78%), free-range chicken meat demonstrated lower contamination (15%) by E. coli when screened on dual antibiotic supplemented plates (ciprofloxacin-plus-cefotaxime) (Supplementary Table S2).

Resistance to Empirically Used Antibiotics Was Rampant in Poultry E. coli

Across the entire dataset of poultry E. coli isolates, resistance to tetracycline was most prevalent (84%) followed by ciprofloxacin (70%), co-trimoxazole (45%), and gentamicin (32%) whereas a small fraction of total E. coli were found to be resistant to chloramphenicol (8%) and fosfomycin (4%) (Table 1). Within each category of chicken samples (broiler and free-range), the isolation sources (ceca and raw meat) did not vary with respect to antimicrobial resistance profiles (P > 0.05 for all variables between groups 1 and 3; and groups 2 and 4) (Table 1). However, the two categories of chicken E. coli isolates exhibited significant difference in prevalence of resistance (MDR and aggregate resistance scores). Strains of E. coli samples in the free-range category tended to be resistant to fewer antimicrobial agents (Table 1). Overall, the rates of ESBL producers in broiler and free-range chicken were as follows: meat 46%; ceca 40% and meat 15%; ceca 30%, respectively (Table 1). The prevalence of ESBL genes differed insignificantly among the four ESBL positive E. coli groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles and aggregate resistance scores for 168 Escherichia coli isolates together with molecular characteristics of 63 extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli.

| Specific trait | No. (%) of isolates resistant |

aP-value* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 168) | Broiler chicken meat isolates (group 1; n = 54) | Free-range chicken meat isolates (group 2; n = 13) | Broiler chicken ceca isolates (group 3; n = 55) | Free-range chicken ceca isolates (group 4; n = 46) | Group 1 vs. 2 | Group 3 vs. 4 | |

|

ABSTe | |||||||

| Tetracycline | 141 (84) | 50 (93) | 12 (92) | 54 (98) | 25 (54) | ns | 0.000 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 118 (70) | 52 (96) | 2 (15) | 40 (73) | 24 (52) | 0.000 | 0.033 |

| Co-trimoxazole | 76 (45) | 33 (61) | 1 (8) | 26 (47) | 16 (35) | 0.001 | ns |

| Gentamicin | 54 (32) | 23 (43) | 1 (8) | 21 (38) | 9 (20) | 0.018 | 0.041 |

| Chloramphenicol | 13 (8) | 5 (9) | 0 | 8 (14) | 0 | ns | 0.007 |

| Fosfomycin | 6 (4) | 3 (6) | 0 | 3 (5) | 0 | ns | ns |

| ESBL phenotypec | 63 (37) | 25 (46) | 2 (15) | 22 (40) | 14 (30) | 0.013 | ns |

| MDR Phenotyped | 85 (51) | 37 (68) | 1 (8) | 35 (64) | 12 (26) | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ESBL positives/genes | n = 63 | n = 25 | n = 2 | n = 22 | n = 14 | aP-value* | |

| blaCTX-M-15 | 50 (79) | 21 (84) | 2 (100) | 17 (77) | 10 (71) | ns | ns |

| blaTEM | 40 (63) | 17 (68) | 2 (100) | 11 (50) | 10 (71) | ns | ns |

| blaSHV | 20 (32) | 8 (32) | 1 (50) | 6 (27) | 5 (36) | ns | ns |

| Aggregate antimicrobial resistance scores | Score median (range) | bP-value* | |||||

| 3 (0–6) | 3 (0–5) | 1 (0–4) | 3 (0–6) | 2 (0–4) | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

∗All comparisons between the groups 1 and 3, and groups 2 and 4 were non-significant (ns) (P > 0.05).

aP-values by Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed.

bP-values (Mann–Whitney U-test) are shown between aggregate resistance scores (sum of resistance genes detected).

cExtended-spectrum-β-lactamase.

dMultidrug-resistant.

eAntibiotic susceptibility tests.

Broiler Chicken Was a Potential Source of Pathogenic E. coli Variants Than the Free-Range Chicken

The distribution of poultry E. coli isolates with respect to the seven phylogenetic groups is shown in Table 2. Overall, the majority of poultry E. coli isolates were affiliated to group A and B1 (36% each), followed by group D (9%), C (8%), F (7%), E and B2 (2%, each). The prevalence of virulence genes among broiler and free-range chicken E. coli isolates was stratified, but the significant prevalence difference (P = 0.000) was only observed between the ceca isolates of the above two categories (Table 2). Overall, 5% (5/109) of broiler E. coli isolates were identified to be extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) based on the detection of three or more ExPEC virulence markers. However, none of the free-range chicken E. coli isolates was suspected to be belonging to ExPEC. Similarly, we found one putative ST131 E. coli in broiler category, which was later confirmed by WGS and in silico MLST, whereas none (0/59) of the free-range E. coli isolates belonged to ST131 clone.

Table 2.

Overall prevalence of phylogenetic group and virulence gene distribution in 168 Escherichia coli isolates recovered from both broiler and free-range chicken with aggregate virulence scores.

| Specific trait | No. (%) of isolates with trait |

aP-value |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 168) | Broiler chicken meat isolates (group1; n = 54) | Free-range chicken meat isolates (group2; n = 13) | Broiler chicken ceca isolates (group 3; n = 55) | Free-range chicken ceca isolates (group 4; n = 46) | Group 1 vs. 2 | Group 3 vs. 4 | Group 1 vs. 3 | Group 2 vs. 4 | |

|

Phylogenetic group | |||||||||

| A | 61 (36) | 19 (35) | 7 (54) | 10 (18) | 25 (54) | ns | 0.000 | 0.045 | ns |

| B1 | 60 (36) | 22 (41) | 1 (8) | 22 (40) | 15 (33) | 0.024 | ns | ns | ns |

| B2 | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (4) | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| C | 13 (8) | 3 (6) | 0 | 6 (11) | 4 (9) | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| D | 15 (9) | 5 (9) | 2 (15) | 8 (15) | 0 | ns | 0.007 | ns | 0.007 |

| E | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (8) | 1 (2) | 0 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| F | 11 (7) | 3 (6) | 2 (15) | 6 (11) | 0 | ns | 0.021 | ns | 0.007 |

|

Virulence genes | |||||||||

| aer | 51 (30) | 26 (48) | 0 | 25 (45) | 0 | 0.001 | 0.000 | ns | – |

| afa | 17 (10) | 8 (15) | 1 (8) | 6 (11) | 2 (4) | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| papC | 6 (4) | 4 (7) | 0 | 2 (4) | 0 | ns | ns | ns | – |

| cvaC | 29 (17) | 6 (11) | 5 (38) | 13 (24) | 5 (11) | 0.017 | ns | ns | 0.019 |

| sfa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| ExPECc | 5 (3) | 4 (7) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | ns | ns | ns | – |

| Aggregate virulence scores | Score median (range) | bP-value | |||||||

| 1 (0–3) | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | 0 (0–2) | ns | 0.000 | ns | 0.010 | ||

aP-values by Fischer’s exact test, two-tailed.

bP-values (Mann–Whitney U-test) are shown between aggregate virulence scores (sum of virulence markers detected).

cExPEC status is defined if ≥ 3 of the virulence genes are detected in an organism.

ns, non-significant (P-values > 0.05).

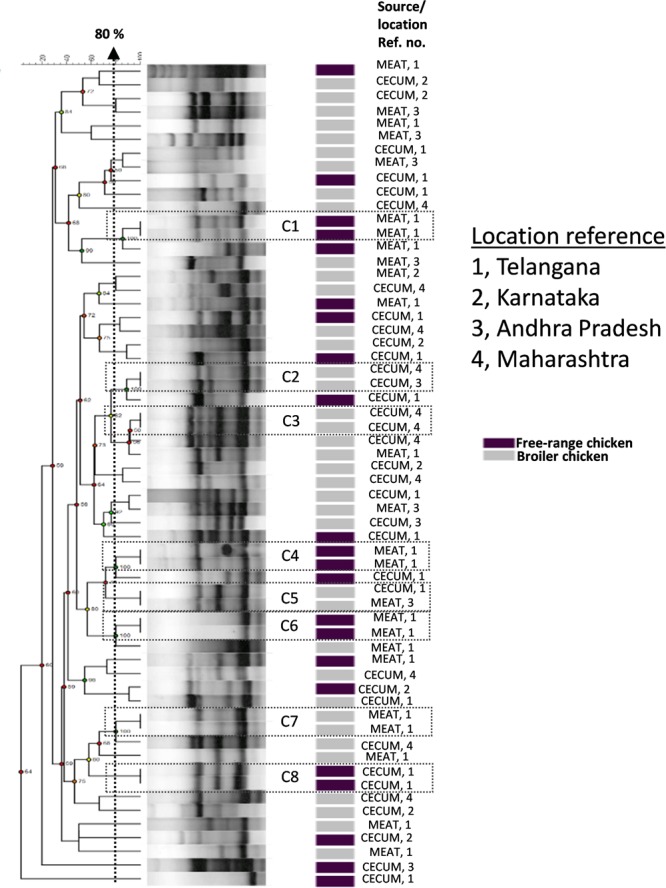

Multiple Chicken Samples from Same Shops Harbored Identical E. coli Clones

We investigated the genetic relationships among the E. coli isolates obtained from broiler and free-range chicken samples (Figure 1). A total of 60 isolates that were multidrug resistant and originating from different geographical locations were analyzed that represented 38 broiler (22 ceca and 16 raw meat) and 22 free-range chicken isolates (12 ceca and 10 raw meat). Out of 60 isolates, 52 distinct ERIC profiles were obtained. Overall, the broiler and free-range chicken E. coli isolates demonstrated promiscuous genetic fingerprints as the two categories did not form distinct clusters. A total of 39 out of 60 isolates demonstrated a close genetic relatedness (similarity coefficient of ≤80%) which were represented in the form of several small sub-clusters. Six out of eight identical clades corresponded consistently with the geographic origin, isolation source and ESBL status but not the sample origin; this possibly hints at cross contamination during rearing, slaughtering and/or processing.

FIGURE 1.

Dendrogram representing genetic relationships of 38 broiler and 22 free-range chicken Escherichia coli isolates based on ERIC-PCR fingerprints. The clustering was performed by UPGMA algorithm based on Dice similarity coefficients. The genotypic patterns generated by ERIC-PCR were analyzed at 80% cutoff. Among the eight identical clades (C1 to C8), six clades corresponded consistently to geographic and isolation source.

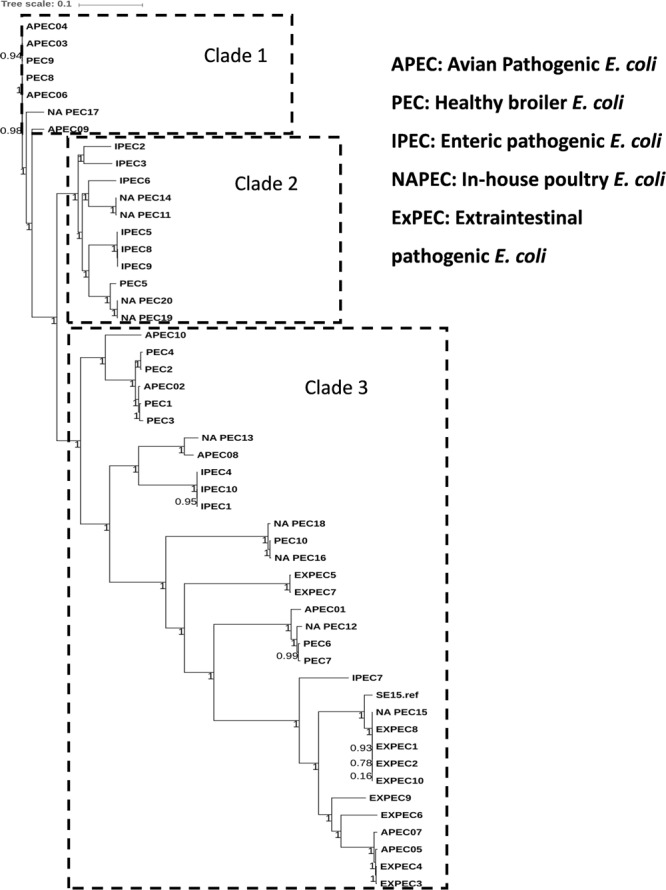

Poultry E. coli Isolates Shared Remarkable Similarities with Human and Avian E. coli Pathotypes

The general features of 10 in-house whole genome sequenced poultry E. coli isolates were shown in Supplementary Tables S1 and S4. We generated a phylogenetic tree (Figure 2) of 10 in-house isolates to study their relationship with 40 other publicly available genomes comprising of 20 human disease-associated E. coli (10 ExPEC and 10 enteric pathogens), 10 Avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) and 10 E. coli genomes from healthy broiler chickens (Supplementary Table S3). Despite genetic diversity, the phylogenetic tree was able to largely cluster isolates of different pathotypes. The clade 1 was dominated with avian strains and clade 2 mainly comprised genomes of enteric strains together with poultry E. coli. The clade 3 comprised strains from all five pathotypes in which the in-house poultry E. coli was found to be co-clustered with APEC, poultry and ExPEC strains but not with enteric strains. Out of 10 poultry genomes analyzed, one was represented in clade 1, four genomes in clade 2 and five genomes in clade 3. Overall, we observed that the core genome content of poultry E. coli genomes failed to demonstrate unambiguous distinction with other human E. coli pathotypes.

FIGURE 2.

Phylogenetic tree of 50 E. coli strains: the core genome based consensus Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of 10 in-house poultry E. coli isolates together with 40 other publicly available human and animal disease associated E. coli isolates generated using Harvest. The output of Harvest was visualized using iTOL tool (http://itol.embl.de/). Despite genetic diversity, the phylogenetic tree on the whole was able to diffusely group isolates belonging to different pathotypes.

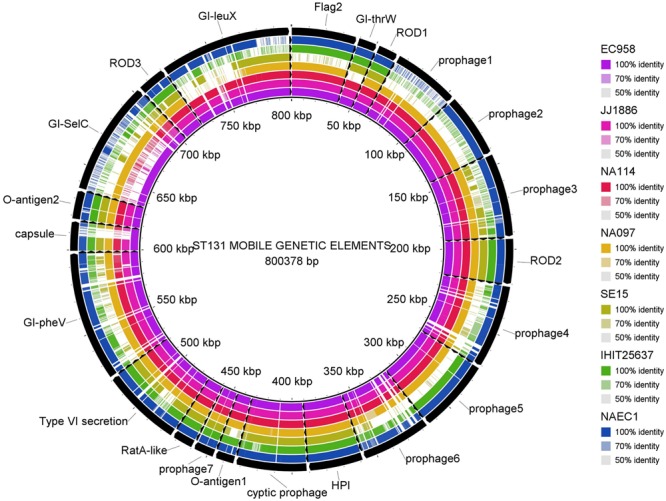

Multiple genome comparison was carried out using BRIG tool for one in-house poultry E. coli isolate (NAEC1 or NAPEC_15) belonging to the ST131 lineage with five other ST131 E. coli genomes to determine the status of 22 mobile genetic elements as reported in EC958 (Figure 3). Out of six genomes, three strains (JJ1886, NA114, and NA097) including the NAEC1 shared significant genetic similarities with respect to composition of mobile genetic elements. However, the other avian genome IHT25637 and the commensal ST131 genome SE15 contained only few complete mobile elements. The presence of mobile genomic islands in the poultry E. coli resembling to that of human E. coli pathotypes reinforces the understanding that these isolates could possibly cross infect humans and poultry.

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of EC958 genomic islands (GIs) in 6 ST131 E. coli genomes: results show that the 22 GIs of EC958 are well-conserved among three human and one in-house ST131 poultry E. coli genome (NAEC1) but partially present in the commensal ST131 (SE15) and the poultry E. coli genome from Germany (IHIT25637). Detail description of the genomes analyzed are as follows- JJ1886; CP006784.1 (Human ExPEC, United States), NA114; GCA_000214765.3 (Human ExPEC, India), NA097; GCA_001029415.1 (Human ExPEC, India), SE15; GCA_000010485.1 (Human commensal, Japan), IHIT25637; GCA_001676995.1 (Avian ExPEC, Germany).

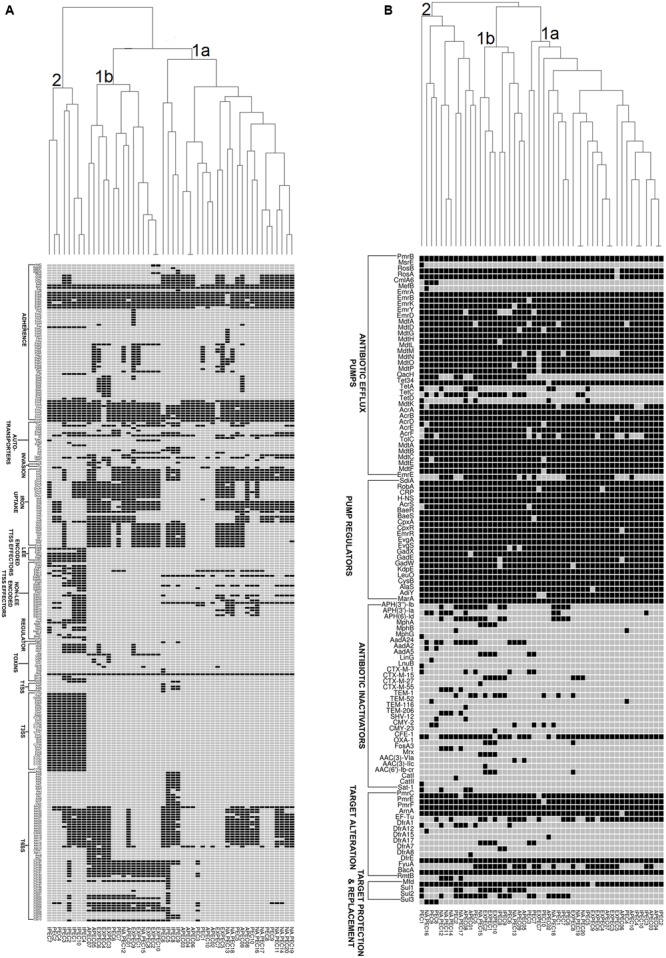

In order to understand the genetic relationships of virulence and resistance of poultry E. coli in juxtaposition with the genetic landscapes of different human E. coli pathotypes, we compared virulence and resistance profiles of 10 sequenced poultry E. coli genotypes with 40 publicly E. coli genomes (Supplementary Table S3). Hierarchical clustering of resistance profiles (Figure 4B) demonstrated that the two sister clusters 1a and 1b represented isolates from all pathotypes including the five in-house poultry genomes. However, cluster 2 was clearly defined or dominated by poultry E. coli isolates that also contained the remaining five in-house poultry genomes. The cluster obtained by the virulence gene profiles (Figure 4A) grouped strains into two categories; one composed of mixed pathotypes (sister clusters 1a and 1b) and the other cluster 2 was dominated with enteric isolates (8/10 enteric genomes). The 10 in-house poultry E. coli isolates were represented in the mixed clusters (1a and 1b) indicating closer genetic identity with some pathotypes (ExPEC, APEC and poultry E. coli), than with others (IPEC or enteric pathotypes). Overall, these observations hint at the zoonotic potential of poultry E. coli.

FIGURE 4.

Gene cluster results for 50 E. coli isolates: the presence (Black Square) and the absence (Gray Square) of virulence genes (A) and resistance genes (B) are represented in the image. Gene names are listed on the left. E. coli pathotypes are listed below the image (APEC: avian pathogenic E. coli, ExPEC: extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli, IPEC: intestinal pathogenic E. coli, PEC: healthy poultry E. coli, NA_PEC: in-house poultry E. coli). Results of resistance clustering indicated that only 50% of our poultry E. coli shared resistance genes with other E. coli pathotypes (distributed in mixed clusters 1a and 1b) and the rest formed a separate group (cluster 2, B). However, the virulence based cluster diagram showed that the in-house poultry (NAPEC) shared more virulence similarity with ExPEC and APEC genomes compared to intestinal pathogenic E. coli (IPEC), as cluster 2 of (A) was dominated by enteric E. coli genomes without any poultry E. coli genome.

Discussion

In this molecular-epidemiological study, we assessed E. coli isolates obtained from retail poultry (meat/carcass) from a wide geographical region extending across three south Indian and one west-central Indian states (four states) by using both conventional typing and WGS methods. Our findings provide evidence that the raw retail poultry meat could indeed be contaminated with antimicrobial-resistant and potentially pathogenic E. coli. This is particularly alarming for countries such as India given high disease burden, emergence of resistance traits, and the confluence of prevailing socio-economic, demographic and environmental factors (Jadhav et al., 2011; Dikid et al., 2013).

Pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC and diarrheagenic) are the leading cause of infections in both humans and poultry (Ewers et al., 2007). Increased antimicrobial usage in the poultry industry due to the growing demand might have contributed significantly to the emergence and dissemination of multiresistant and pathogenic E. coli variants, which could be a serious public health threat (Laxminarayan and Chaudhury, 2016). Hence, constant surveillance and knowledge of their transmission and epidemiology with respect to their genetic backgrounds, antimicrobial resistance patterns and specific virulence attributes is pertinent (Mellata, 2013; Laxminarayan and Chaudhury, 2016). Our findings therefore have potential implications for public health policies entailing antibiotic usage regulation.

Poultry industries use antibiotics both for therapeutic purposes and for growth promotion (Singer and Hofacre, 2006). Recent studies in different parts of India have reported antimicrobial residues in food animal products such as chicken meat suggesting large-scale unregulated use of antibiotics by the poultry industry (Laxminarayan and Chaudhury, 2016; Brower et al., 2017). This is consistent with our observations as we also found a marked predominance of antibiotic resistance among E. coli isolates obtained from conventionally raised (broiler) chicken. In contrast, free-range chicken meat were comparatively less contaminated with multidrug resistant E. coli; this observation echoes previously reported studies (Koga et al., 2015; Rugumisa et al., 2016). The above observation complements the cross contamination hypothesis of poultry carcasses with the host’s fecal flora during slaughter and processing also given that we found comparable antimicrobial resistance prevalences in E. coli isolates entailing ceca and raw meat samples of broiler chicken. Such observations were also evidenced by others (Rasschaert et al., 2008; Firildak et al., 2015). The reason for higher prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in E. coli isolates of broiler chicken could be due to the high antibiotic selection pressure.

Similar to other studies (Klimienė et al., 2017) the predominant ESBL genotype detected in chicken E. coli isolates was blaCTX-M-15 gene which is also the most frequently reported genotype in human health care settings (Chen et al., 2014). The pan-genome based resistance gene profiling revealed that 50% of poultry E. coli shared resistance genes with human E. coli pathotypes (Figure 4B). The formation of a separate cluster of the remaining 50% of the poultry genomes indicates difference in resistance determinants with that of human E. coli resistomes which could be reflective of differences in antimicrobial usage practices in human medicine and livestock rearing.

Although only a fraction of total poultry isolates did belong to two well-established pathogenic phylogroups B2 and D (2%, 9%, respectively), a majority of them (36% each) belonged to phylogroups A and B1 (Table 2), as also reported by others (Jakobsen et al., 2010; Klimienė et al., 2017). Nonetheless, these two phylogroups have also been previously described to harbor isolates with a high pathogenic potential for birds and humans (Rodriguez-Siek et al., 2005; Ewers et al., 2007; Kobayashi et al., 2011). Virulence gene (Franz et al., 2015) screening demonstrated that the broiler E. coli isolates differed from free-range chicken E. coli isolates by their higher prevalence of all the virulence genes. Furthermore, five broiler E. coli isolates were identified to be ExPEC with none from free-range chicken E. coli (Table 2). The overall low prevalence of poultry E. coli isolates from ExPEC category was expected because all samples were collected from healthy birds. This corroborates also with the low prevalence of phylogenetic group B2.

The phylogenetic tree, based on core genomes demonstrated that, the poultry E. coli isolates are not a homogeneous group, because some of the poultry E. coli isolates revealed similar genetic backgrounds with human ExPEC and enteric isolates, thus pointing to the role of chickens as reservoir of potentially pathogenic E. coli. Only a few studies have investigated the presence of E. coli ST131 in food animals; E. coli ST131 producing CTX-M-15 also appears to be very rare in foodstuffs of animal origin (Nicolas-Chanoine et al., 2014). This study confirmed the presence of two globally emerging pathogenic lineages of E. coli; ST131 (H30-Rx subclone) and ST117. The other commonly identified sequence types among the 10 poultry E. coli genomes were; ST115, ST155, and ST1640 which are reported to be mostly associated with ESBL phenotypes (Borjesson et al., 2013). Moreover, the identified ST131 E. coli contained more pathogenicity islands than the other poultry genomes from Europe and the commensal ST131 genome-SE15 (Figure 3). The presence of such a strain in poultry meat belonging to the epidemiologically successful clonal lineage ST131 (H30-Rx subclone) warrants attention.

Corroborating with phylogeny results, virulence gene profiling revealed that the poultry E. coli are not a homogenous group and showed mixed clustering. However, it provided better resolution between ExPEC and enteric pathotypes (Figure 4A). Nonetheless, a majority of poultry E. coli isolates and human ExPEC were clustered together with respect to the virulence gene content suggesting that they share remarkable similarities with human ExPEC pathotypes (Figure 4A). The ERIC fingerprinting of broiler and free-range chicken E. coli isolates demonstrated that the poultry E. coli are diverse. The identical clones that we observed mostly corresponded to the geographic (abattoir) and host (broiler and free-range) origins (Figure 1).

This geographically wide report on molecular and genomic characterization of E. coli from broiler and free-range chickens is the first from India. Herein, we found that the raw retail poultry meat was frequently contaminated with antimicrobial-resistant E. coli and/or potentially pathogenic E. coli variants. However, free-range chickens represented a low risk of contamination with pathogenic and or resistant E. coli; this is particularly important as India is an agricultural country with around 70% of the population living in rural areas and many of the rural households engage in backyard poultry raising (Singh, 2014). The comparative genomic analysis suggests that the poultry E. coli isolates share closer genetic identity to human E. coli as regards to core genome phylogeny, antimicrobial genes and virulence gene content and thus represent potential zoonotic risks. The possibility that multi-drug resistant and /or pathogenic E. coli could be potentially transmitted from food sources such as chicken meat raises serious public health concerns regarding food preparations where chicken meat may not be properly cooked or could only be pickled raw.

Author Contributions

AH, DC, and NA designed and conducted the study. AR, NN, TS, LW, MI, MM, and IQ helped in analysis of data and preparation of the manuscript. SS, ST, and RB helped in analyzing genome sequence data.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the members of the molecular pathogenesis lab at Indian Institute of Science for their help and support. We would also like to acknowledge the ‘Microsoft Azure for Research Award’ from Microsoft Corporation to NA.

Funding. The financial support of UGC, New Delhi through its project No. F.4-2/2006 (BSR)/BL/14-15/0273 to AH as a UGC’s Dr. D. S. Kothari post-doctoral fellowship is thankfully acknowledged.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02120/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alikhan N.-F., Petty N. K., Ben Zakour N. L., Beatson S. A. (2011). BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics 12:402. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avasthi T. S., Kumar N., Baddam R., Hussain A., Nandanwar N., Jadhav S., et al. (2011). Genome of multidrug-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain NA114 from India. J. Bacteriol. 193 4272–4273. 10.1128/JB.05413-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A. A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19 455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger L., Garenaux A., Harel J., Boulianne M., Nadeau E., Dozois C. M. (2011). Escherichia coli from animal reservoirs as a potential source of human extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 62 1–10. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borjesson S., Egervarn M., Lindblad M., Englund S. (2013). Frequent occurrence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- and transferable AmpC Beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli on domestic chicken meat in Sweden. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 2463–2466. 10.1128/AEM.03893-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower C. H., Mandal S., Hayer S., Sran M., Zehra A., Patel S. J., et al. (2017). The prevalence of extended-spectrum Beta-lactamase-producing multidrug-resistant Escherichia Coli in poultry chickens and variation according to farming practices in Punjab, India. Environ. Health Perspect. 125 1–10. 10.1289/EHP292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. F., Freeman J. T., Nicholson B., Keiger A., Lancaster S., Joyce M., et al. (2014). Widespread dissemination of CTX-M-15 genotype extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing enterobacteriaceae among patients presenting to community hospitals in the southeastern United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 1200–1202. 10.1128/AAC.01099-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Jiang X. (2014). Microbiological safety of chicken litter or chicken litter-based organic fertilizers: a review. Agriculture 4 1–29. 10.3390/agriculture4010001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clermont O., Christenson J. K., Denamur E., Gordon D. M. (2013). The Clermont Escherichia coli phylo-typing method revisited: improvement of specificity and detection of new phylo-groups. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 5 58–65. 10.1111/1758-2229.12019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2013). VET01-A4 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated From Animals; Approved Standard Fourth Edn. Wayne, PA: CLSI. [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood C., Kemmett K., Williams N., Wigley P. (2014). Is the concept of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli as a single pathotype fundamentally flawed? Front. Vet. Sci. 1:5. 10.3389/fvets.2014.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Been M., Lanza V. F., de Toro M., Scharringa J., Dohmen W., Du Y., et al. (2014). Dissemination of cephalosporin resistance genes between Escherichia coli strains from farm animals and humans by specific plasmid lineages. PLOS Genet. 10:e1004776. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikid T., Jain S. K., Sharma A., Kumar A., Narain J. P. (2013). Emerging & re-emerging infections in India: an overview. Indian J. Med. Res. 138 19–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziva F., Hauser H., Connor T. R., van Diemen P. M., Prescott G., Langridge G. C., et al. (2013). Sequencing and functional annotation of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli serogroup O78 strains reveal the evolution of E. coli lineages pathogenic for poultry via distinct mechanisms. Infect. Immun. 81 838–849. 10.1128/IAI.00585-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewers C., Li G., Wilking H., Kiessling S., Alt K., Antáo E.-M., et al. (2007). Avian pathogenic, uropathogenic, and newborn meningitis-causing Escherichia coli: how closely related are they? Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297 163–176. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firildak G., Asan A., Goren E. (2015). Chicken carcasses bacterial concentration at poultry slaughtering facilities. Asian J. Biol. Sci. 8 16–29. 10.3923/ajbs.2015.16.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franz E., Veenman C., van Hoek A. H. A. M., de Roda Husman A., Blaak H. (2015). Pathogenic Escherichia coli producing extended-spectrum β-Lactamases isolated from surface water and wastewater. Sci. Rep. 5:14372. 10.1038/srep14372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain A., Ewers C., Nandanwar N., Guenther S., Jadhav S., Wieler L. H., et al. (2012). Multiresistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli from a region in India where urinary tract infections are endemic: genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of sequence type 131 isolates of the CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing lineage. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56 6358–6365. 10.1128/AAC.01099-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain A., Ranjan A., Nandanwar N., Babbar A., Jadhav S., Ahmed N. (2014). Genotypic and phenotypic profiles of Escherichia coli isolates belonging to clinical sequence type 131 (ST131), clinical non-ST131, and fecal non-ST131 lineages from India. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 7240–7249. 10.1128/AAC.03320-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav S., Hussain A., Devi S., Kumar A., Parveen S., Gandham N., et al. (2011). Virulence characteristics and genetic affinities of multiple drug resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli from a semi urban locality in India. PLOS ONE 6:e18063. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen L., Kurbasic A., Skjøt-Rasmussen L., Ejrnæs K., Porsbo L. J., Pedersen K., et al. (2010). Escherichia coli isolates from broiler chicken meat, broiler chickens, pork, and pigs share phylogroups and antimicrobial resistance with community-dwelling humans and patients with urinary tract infection. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 7 537–547. 10.1089/fpd.2009.0409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. R., Murray A. C., Gajewski A., Sullivan M., Snippes P., Kuskowski M. A., et al. (2003). Isolation and molecular characterization of nalidixic acid-resistant extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli from retail chicken products isolation and molecular characterization of nalidixic acid-resistant extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47 2161–2168. 10.1128/AAC.47.7.2161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper J. B., Nataro J. P., Mobley H. L. T. (2004). Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2 123–140. 10.1038/nrmicro818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimienė I., Virgailis M., Kerzienė S., Šiugždinienė R., Mockeliūnas R., Ružauskas M. (2017). Evaluation of genotypical antimicrobial resistance in ESBL producing Escherichia coli phylogenetic groups isolated from retail poultry meat. J. Food Saf. e12370. 10.1111/jfs.12370 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi R. K. T., Aquino I., Ferreira A. L., da S., Vidotto M. C. (2011). EcoR phylogenetic analysis and virulence genotyping of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strains and Escherichia coli isolates from commercial chicken carcasses in Southern Brazil. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 8 631–634. 10.1089/fpd.2010.0726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga V. L., Scandorieiro S., Vespero E. C., Oba A., de Brito B. G., de Brito K. C. T., et al. (2015). Comparison of antibiotic resistance and virulence factors among Escherichia coli isolated from conventional and free-range poultry. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015:618752. 10.1155/2015/618752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landers T. F., Cohen B., Wittum T. E., Larson E. L. (2012). A review of antibiotic use in food animals: perspective, policy, and potential. Public Health Rep. 127 4–22. 10.1177/003335491212700103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxminarayan R., Chaudhury R. R. (2016). Antibiotic resistance in India: drivers and opportunities for action. PLOS Med. 13:e1001974. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutful Kabir S. M. (2010). Avian colibacillosis and salmonellosis: a closer look at epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, control and public health concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 7 89–114. 10.3390/ijerph7010089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellata M. (2013). Human and avian extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli: infections, zoonotic risks, and antibiotic resistance trends. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 10 916–932. 10.1089/fpd.2013.1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell N. M., Johnson J. R., Johnston B., Curtiss Iii R., Mellata M. (2015). Zoonotic potential of Escherichia coli isolates from retail chicken meat products and eggs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81 1177–1187. 10.1128/AEM.03524-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandanwar N., Hussain A., Ranjan A., Jadhav S., Ahmed N. (2016). Population structure and molecular epidemiology of human clinical multi-drug resistant (MDR) Escherichia coli strains from Pune, India. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 45 343–344. 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.02.741 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nandanwar N., Janssen T., Kühl M., Ahmed N., Ewers C., Wieler L. H. (2014). Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) of human and avian origin belonging to sequence type complex 95 (STC95) portray indistinguishable virulence features. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 95 6–13. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas-Chanoine M. H., Bertrand X., Madec J. Y. (2014). Escherichia coli st131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 27 543–574. 10.1128/CMR.00125-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R., Olson R., Pusch G. D., Olsen G. J., Davis J. J., Disz T., et al. (2014). The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res. 42 D206–D214. 10.1093/nar/gkt1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R. K., Jain M. (2012). NGS QC toolkit: a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. PLOS ONE 7:e30619. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qumar S., Majid M., Kumar N., Tiwari S. K., Semmler T., Devi S., et al. (2017). Genome dynamics and molecular infection epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Helicobacter pullorum isolates obtained from broiler and free-range chickens in India. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83 e2305–e2316. 10.1128/AEM.02305-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan A., Shaik S., Hussain A., Nandanwar N., Semmler T., Jadhav S., et al. (2015). Genomic and functional portrait of a highly virulent, CTX-M-15-producing H30- Rx subclone of Escherichia coli sequence type (ST) 131. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59 6087–6095. 10.1128/AAC.01447-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan A., Shaik S., Mondal A., Nandanwar N., Hussain A., Semmler T., et al. (2016). Molecular epidemiology and genome dynamics of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM) producing extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) strains from India. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 6795–6805. 10.1128/AAC.01345-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan A., Shaik S., Nandanwar N., Hussain A., Tiwari S. K., Semmler T., et al. (2017). Comparative genomics of Escherichia coli isolated from skin and soft tissue and other extraintestinal infections. MBio 8:e01070–17. 10.1128/mBio.01070-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasschaert G., Houf K., Godard C., Wildemauwe C., Pastuszczak-Frak M., De Zutter L. (2008). Contamination of carcasses with Salmonella during poultry slaughter. J. Food Prot. 71 146–152. 10.4315/0362-028X-71.1.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Siek K. E., Giddings C. W., Doetkott C., Johnson T. J., Fakhr M. K., Nolan L. K. (2005). Comparison of Escherichia coli isolates implicated in human urinary tract infection and avian colibacillosis. Microbiology 151 2097–2110. 10.1099/mic.0.27499-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugumisa B. T., Call D. R., Mwanyika G. O., Subbiah M., Buza J. (2016). African journal of microbiology research comparison of the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from commercial-layer and free-range chickens in Arusha district. Tanzania 10 1422–1429. 10.5897/AJMR2016.8251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford K., Parkhill J., Crook J., Horsnell T., Rice P., Rajandream M. A., et al. (2000). Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16 944–945. 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schissler J. R., Hillier A., Daniels J. B., Cole L. K., Gebreyes W. A. (2009). Evaluation of Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute interpretive criteria for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from dogs. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 21 684–688. 10.1177/104063870902100514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaik S., Kumar N., Lankapalli A. K., Tiwari S. K., Baddam R., Ahmed N. (2016). Contig-Layout-Authenticator (CLA): a combinatorial approach to ordering and scaffolding of bacterial contigs for comparative genomics and molecular epidemiology. PLOS ONE 11:e0155459. 10.1371/journal.pone.0155459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer R. S., Hofacre C. L. (2006). Potential impacts of antibiotic use in poultry production. Avian. Dis. 50 161–172. 10.1637/7569-033106R.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P. (2014). Population and agro climatic zones in India: an analytical analysis. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 120 268–278. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Totsika M., Beatson S. A., Sarkar S., Phan M. D., Petty N. K., Bachmann N., et al. (2011). Insights into a multidrug resistant Escherichia coli pathogen of the globally disseminated ST131 lineage: genome analysis and virulence mechanisms. PLOS ONE 6:e26578. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treangen T. J., Ondov B. D., Koren S., Phillippy A. M. (2014). The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 15:524. 10.1186/PREACCEPT-2573980311437212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bogaard A. E., London N., Driessen C., Stobberingh E. E. (2001). Antibiotic resistance of faecal Escherichia coli in poultry, poultry farmers and poultry slaughterers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47 763–771. 10.1093/JAC/47.6.763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Massow A., Stanley M., Papariella M., Chen X., Kraft B., et al. (2011). Contamination rates and antimicrobial resistance in Enterococcus spp., Escherichia coli, and Salmonella isolated from "no antibiotics added"-labeled chicken products. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 8 1147–1152. 10.1089/fpd.2011.0852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.