Abstract

Drug-resistant influenza is a significant threat to global public health. Until new antiviral agents with novel mechanisms of action become available, there is a pressing need for alternative treatment strategies with available influenza antivirals. Our aims were to evaluate the antiviral activity of two neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir and zanamivir) as combination therapy against H1N1 influenza A viruses, as these agents bind to the neuraminidase active site differently: oseltamivir requires a conformational change for binding whereas zanamivir does not. We performed pharmacodynamic studies in the hollow fiber infection model (HFIM) system with oseltamivir (75 mg Q12h, t1/2: 8 h) and zanamivir (600 mg Q12h, t1/2: 2.5 h), given as mono- or combination therapy, against viruses with varying susceptibilities to oseltamivir and zanamivir. Each antiviral suppressed the replication of influenza strains which were resistant to the other neuraminidase inhibitor, showing each drug does not engender cross-resistance to the other compound. Oseltamivir/zanamivir combination therapy was as effective at suppressing oseltamivir- and zanamivir-resistant influenza viruses and the combination regimen inhibited viral replication at a level that was similar to the most effective monotherapy arm. However, combination therapy offered a clear benefit by preventing the emergence and spread of drug-resistant viruses. These findings demonstrate that combination therapy with two agents that target the same viral protein through distinctly different binding interactions is a feasible strategy to combat resistance emergence. This is a novel finding that may be applicable to other viral and non-viral diseases for which different classes of agents do not exist.

Keywords: pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, combination therapy, hollow fiber infection model system

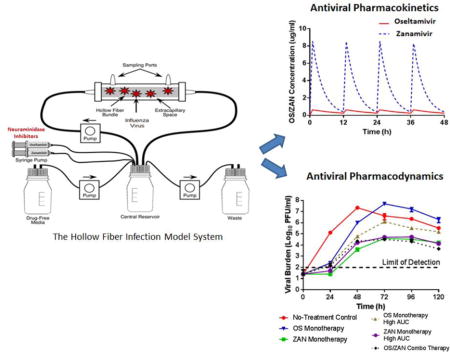

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

There are currently two classes of antiviral drugs that are globally approved for the treatment of influenza in humans, the adamantanes (amantadine and rimantadine) and the neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir). Wide-spread use of these antiviral agents as monotherapy has contributed to the emergence of influenza viruses that are resistant to compounds from both drug classes (de Jong et al., 2005; Ison et al., 2006b; Ison et al., 2006a; Li et al., 2015). Indeed, the frequency of adamantane resistance in circulating influenza strains is so high that amantadine is no longer recommended for the treatment of influenza (Hayden, 2006). Oseltamivir-resistant influenza has also been detected, but the prevalence of these strains is seasonal. This was demonstrated during the 2008–2009 influenza season where nearly 100% of all H1N1 isolates were resistant to oseltamivir in the United States and Japan (CDC, 2009a; Matsuzaki et al., 2010). This oseltamivir-resistant seasonal virus was displaced by the spread of 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza, which was susceptible to oseltamivir and became the predominant strain. Influenza viruses currently in circulation are sensitive to oseltamivir with only a few sporadic cases of resistance reported (CDC, 2009c; CDC, 2009b). Finally, zanamivir-resistant viruses have been described, albeit very infrequently (Hurt et al., 2009). The low prevalence of zanamivir-resistance is likely tied to the low clinical use of this agent due to poor oral bioavailability; consequently, zanamivir is administered via inhalation with a disk-inhaler (GlaxoSmithKline, 2009). This method of delivery is not suitable for patient populations that have the highest morbidity and mortality rates from influenza, including children, those with underlying respiratory ailments (i.e.: asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), or the severely ill. An intravenous (i.v.) formulation of zanamivir is available, but is not currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration despite demonstrating good efficacy in critically-ill hospitalized influenza patients (Dulek et al., 2010; Marty et al., 2014; Watanabe et al., 2015).

The emergence and spread of drug-resistant influenza is a significant public health concern and transmission of such viruses may ultimately render antiviral intervention useless. Combination therapy with two or more agents has potential to enhance effectiveness and counter drug-resistance, as demonstrated by the success of multiple drug regimens for the treatment of hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus (Foster et al., 2015; Gane et al., 2013; Zeuzem et al., 2013; Autran et al., 1997; Larder et al., 1995; Markowitz et al., 2007; Markowitz et al., 2009). However, this therapeutic approach has only been occasionally investigated for influenza. One glaring obstacle for combination therapy is the lack of approved compounds with different mechanisms of action. Presently, only the neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir and zanamivir) are prescribed for influenza. Combination therapy with oseltamivir and zanamivir is reasonable because these agents bind within the neuraminidase active site differently (Moscona, 2005). In order for oseltamivir to bind into the active site, a conformational change must occur within the neuraminidase to accommodate the steric bulk of the drug whereas zanamivir binds directly to the neuraminidase without any structural rearrangement (Moscona, 2005). These mechanistic differences in binding explain why oseltamivir and zanamivir have non-overlapping resistance profiles, so that oseltamivir-resistant influenza viruses remain susceptible to zanamivir and vice versa. Additionally, the likelihood of selecting for viruses that are dually resistant to both oseltamivir and zanamivir is low. Thus, combination therapy with these two agents may serve as a rational strategy to overcome the emergence of resistance. Peramivir was not evaluated in these studies since oseltamivir and peramivir have overlapping resistance profiles (Takashita et al., 2014).

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of oseltamivir and zanamivir as combination therapy against influenza A viruses and, more importantly, assess the ability of this regimen to prevent the emergence and spread of resistance. This therapeutic strategy of using two drugs with the same mechanism of action to combat influenza resistance is novel and may serve as a strategy to fight other viral and non-viral infections for which multiple classes of anti-infective drugs do not exist.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses and Cells

The wild-type pandemic 2009 H1N1 A/Mexico/4108/2009 (MX/09), oseltamivir-resistant pandemic 2009 H1N1 A/Hong Kong/2369/2009 [H275Y] (HK/09-H275Y), and zanamivir-resistant seasonal 2008 H1N1 A/Brazil/1633/2008 [Q136K] (BZ/08-Q136K) influenza virus strains were provided by Dr. Larisa Gubareva from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA). Viral stocks were prepared in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, as described elsewhere (Brown et al., 2010). MDCK cells (ATCC #CCL-34) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in minimal essential medium (MEM; Hyclone, Logan, UT) [supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), non-essential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100μg/ml of streptomycin, and 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate] at 37°C and 5% CO2.

2.2. Compounds

Oseltamivir carboxylate was obtained from Hoffmann-La Roche Inc. (Nutley, NJ) and zanamivir was provided by GlaxoSmithKline (Philadelphia, PA). Both drugs were reconstituted in sterile distilled water to a final active concentration of 10 mg/ml, filter-sterilized through a 0.2 micron filter, and aliquoted. Oseltamivir aliquots were stored at 4°C and zanamivir aliquots were stored at −80°C. Fresh drug stocks were prepared at the beginning of each study.

2.3. Drug Susceptibility Assay

The antiviral activity of oseltamivir and zanamivir against influenza was determined using the commercially available chemiluminescence-based NA-Star influenza neuraminidase inhibitor resistance detection kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were calculated using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

2.4. The Hollow Fiber Infection Model (HFIM) system

The hollow fiber infection model (HFIM) system has been described previously (Brown et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2011a; McSharry et al., 2009). For these studies, single virus and mixed-virus infections were assessed in the HFIM system. For single virus infections, 102 plaque forming units (PFU) of virus (MX/09, HK/09-H275Y, or BZ/08-Q136K) were mixed with 108 uninfected MDCK cells and resuspended in 25 mls of viral growth medium (VGM) [MEM, bovine serum albumin at a final concentration of 0.2% (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO), 2 ug/ml of L-1-(tosyl-amido-2-phenyl)ethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc), 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100μg/ml of streptomycin]. Virus containing cell suspensions were inoculated into the extra-capillary space (ECS) of polysulfone hollow-fiber (HF) cartridges (FiberCell Systems, Frederick, MD) and incubated at 36°C, 5% CO2. For mixed virus infections, 99 PFU of MX/09 were mixed with 1 PFU of HK/09-H275Y and inoculated into HF cartridges with 108 uninfected MDCK cells as described above.

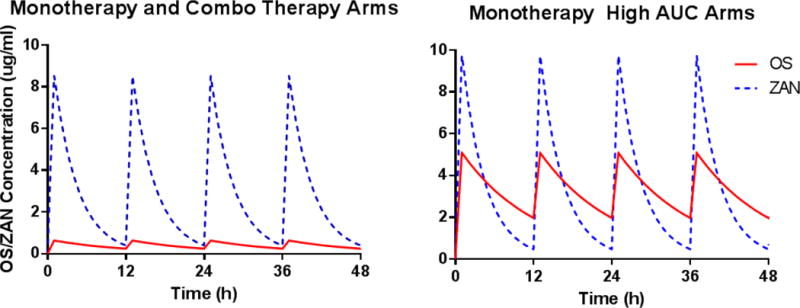

Five different oseltamivir and/or zanamivir dosage regimens were evaluated against each virus inoculation condition. The 24-h area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) for exposures associated with oral oseltamivir at 75 mg twice daily (Q12) and i.v. zanamivir at 600 mg Q12 were delivered into HF cartridges, either alone (monotherapy) or in combination, as a 1 h infusion via computer-programed syringe pumps. The pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles for oseltamivir and zanamivir in HF units were extrapolated from average human serum PK data (Doucette and Aoki, 2001; GlaxoSmithKline, 2009). The reported human half-lives of 8 h for oseltamivir (Doucette and Aoki, 2001) and 2.5 h for zanamivir (GlaxoSmithKline, 2009) were simulated in these experiments. One cartridge for each virus inoculum did not receive drug treatment and served as a no-treatment control. Finally, two additional experimental arms were included in which oseltamivir and zanamivir were administered as monotherapy at an exposure equivalent to the oseltamivir-zanamivir combination arm to ensure that any additional effect from the combination was not solely due to the higher drug exposure in this arm. These two arms are termed “monotherapy high exposure”. The simulated PK profiles for oseltamivir and zanamivir in the HFIM system are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Targeted PK profiles for oseltamivir (red line) and zanamivir (blue dashed line) in the HFIM system.

The ECS from each HF cartridge was sampled every 24 h. Samples were harvested from the left and right sampling ports, centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g to remove cell debris, and frozen at −80°C until the end of the study. Viral burden was assessed by plaque assay on MDCK cells as previously described (Brown et al., 2011a; Hayden et al., 1980).

HF experiments with MX/09, HK/09-H275Y, and 99% MK/09+1% HK/09-H275Y were conducted simultaneously. Experiments with BZ/08-Q136K were performed independently.

2.5. Pyrosequencing

Pyrosequencing was performed to quantify HK/09-H275Y populations in HF arms inoculated with a mixed virus infection, as previously described (Deyde et al., 2010). Briefly, template preparation of biotinylated PCR products for pyrosequencing was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the Vacuum Prep Workstation (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden) and Streptavidin Sepharose HP (Amersham Biosciences), with the following modifications: 1) the final concentration of sequencing primer used in the annealing step was 0.5 μM; and 2) the primer annealing step was done by placing the plate on a heat block set to 85°C for 2 minutes, followed by cooling on the bench for 5 minutes (on the thermoplate), and then removing the plate from the thermoplate and cooling for an additional 5 minutes directly on the benchtop. Pyrosequencing of samples were done by the Wadsworth Center Applied Genomic Technologies Core Facility, using a PyroMark ID pyrosequencer (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were sequenced in SNP mode (analysis version 1.0.5) with the directed dispensation: GATCGACTA. Sequences were analyzed in Allele-Quantification (AQ) mode, which calculates the percentage of each allele in the sequence of interest. Each result is given a quality value of Pass, Check, or Failed. Quality assessment criteria include warnings for low signal-to-noise ratio, wide peaks and possible dispensation errors for results that do not receive a value of pass.

2.6. Oseltamivir and Zanamivir concentrations in the HFIM system

The concentration of oseltamivir and/or zanamivir was quantified in each sample by high-pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS-MS). The LC-MS-MS methods for oseltamivir (McSharry et al., 2009) and zanamivir (Brown et al., 2011a) are published elsewhere. Oseltamivir and zanamivir concentrations in the HFIM system were within 10% of the desired value at all time points in all experimental arms (data not shown).

3. Results

3.1. Susceptibilities of influenza strains to oseltamivir and zanamivir

The antiviral activities of oseltamivir and zanamivir against wild-type and mutant influenza A viruses were evaluated using the chemiluminescent NA-STAR assay (Table 1). As expected, HK/09-H275Y was resistant to oseltamivir, with an IC50 of 15.30 ng/ml, but sensitive to zanamivir (IC50 = 0.0024 ng/ml). Conversely, BZ/08-Q136K was resistant to zanamivir (IC50 = 5.779 ng/ml) but retained sensitivity to oseltamivir (IC50 = 0.0028 ng/ml). MX/09 had IC50 values similar to those reported for other H1N1 wild-type influenza viruses (Brown et al., 2011b; Richard et al., 2011; Sheu et al., 2008), demonstrating that it is sensitive to both neuraminidase inhibitors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antiviral activities of oseltamivir and zanamivir against wild-type and mutant influenza A viruses as determined by the NA-STAR assay.

| Influenza A Isolate | Virus Subtype | IC50 valuesa (95% Confidence Interval) of the following drugb: | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Oseltamivir | Zanamivir | ||

| BZ/08-Q136K | H1N1 seasonal 2008 | 0.0028 (0.0005 – 0.0051) | 5.779 (4.892 – 6.666) |

| MX/09 (wild-type) | H1N1 pandemic 2009 | 0.0492 (0.0373 – 0.0610) | 0.0039 (0.0013 – 0.0066) |

| HK/09-H275Y | H1N1 pandemic 2009 | 15.30 (10.16 – 20.44) | 0.0024 (0.0006 – 0.0042) |

IC50 values are reported in nanograms per milliliter (ng/ml).

Molar masses are 284.3 g/mol for oseltamivir and 332.3 g/mol for zanamivir

3.2. HFIM studies with oseltamivir and zanamivir against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza

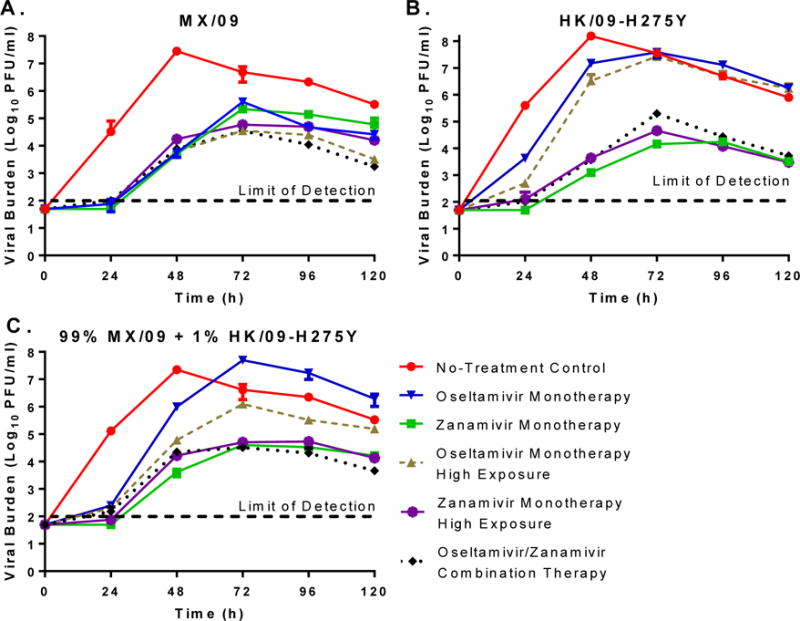

The antiviral activity of oseltamivir and/or zanamivir was evaluated against MX/09 and HK/09-H275Y as single or mixed virus infections (99% MX/09+1% HK/09-H275Y) in the HFIM system. MX/09 and HK/09-H275Y exhibited robust replication in the HFIM system with similar kinetics in the absence of drug (Fig. 2A–B). Moreover, peak viral titers in the no-treatment control arms were slightly higher (approximately 0.6-log10) with HK/09-H275Y compared to MX/09, indicating that the H275Y mutation does not have a negative impact on viral fitness. Replication kinetics between the no-treatment control arms for the mixed viral infection and MX/09 were nearly identical (Fig. 2A,C) and demonstrate that HK/09-H275Y does not preferentially replicate over MX/09 in combination.

Figure 2.

The effect of oseltamivir and zanamivir as mono- and combination therapy against (A) wild-type MX/09 influenza, (B) oseltamivir-resistant HK/09-H275Y influenza, and (C) a mixture of 99% MX/09 and 1% oseltamivir-resistant HK/09-H275Y. Viral burden is reported as Log10 plaque forming units per ml (PFU/ml) and was determined by plaque assay on MDCK cells. Each data point represents the mean of two independent samples and error bars correspond to one standard deviation.

Oseltamivir and zanamivir, whether alone or in combination, suppressed the replication of MX/09 throughout the study relative to the no-treatment control (Fig.2A); however, greater inhibition was observed in the experimental arms that contained higher exposures of drug (Oseltamivir monotherapy high exposure, zanamivir monotherapy high exposure, and oseltamivir/zanamivir combination therapy) relative to standard clinical regimens. Although oseltamivir monotherapy delayed viral replication and blunted peak viral titers, treatment failed to completely suppress HK/09-H275Y, even in the presence of higher drug exposures. Zanamivir monotherapy, regardless of exposure, was effective against HK/09-H275Y, providing sustained viral suppression and reducing peak viral titers by approximately 4-log10 PFU/ml (Fig. 2B). Combination therapy displayed substantial antiviral activity against HK/09-H275Y and was as effective as zanamivir monotherapy (Fig. 2B).

For the mixed virus infection, viral burden was suppressed in all treatment arms relative to the no-treatment control at 24 h post-treatment (Fig. 2C). After 24 h, viral titers rapidly increased in the oseltamivir monotherapy regimen, achieving a peak viral load equivalent to that of the no-treatment control by 72 h. The oseltamivir monotherapy high exposure treatment arm provided some suppression over the standard clinical regimen at 24 h; however, viral burden in this arm was similar to that of the no-treatment control at 48 h and beyond. Zanamivir at the clinical exposure and high exposure provided similar levels of sustained viral inhibition, as viral burden was at least 2-log10 lower than the no-treatment control throughout the experiment. Combination therapy with oseltamivir and zanamivir was as effective as zanamivir treatment arms and inhibited viral burden with nearly identical kinetics (Fig. 2C).

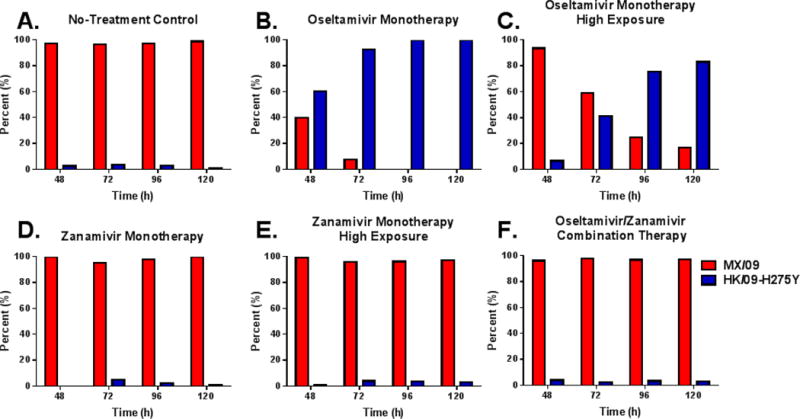

MK/09 and HK/09-H275Y subpopulations were quantified in samples harvested from HF cartridges inoculated with the mixed viral infection by pyrosequencing. As expected, MX/09 was dominant in the no-treatment control arm and comprised at least 97% of the total population at all time-points (Fig. 3A). Oseltamivir monotherapy at the standard clinical exposure rapidly selected for HK/09-H275Y, which became the dominant viral strain by 48h post-therapy (Fig. 3B). By 96h post-treatment, the mixed viral infection contained only HK/09-H275Y. Oseltamivir monotherapy at the high exposure delayed the selection of HK/09-H275Y; but, this level of exposure was unable to completely suppress viral replication over time, as HK/09-H275Y subpopulations increased to 76% by 96h post-treatment and 83% by 120h (Fig. 3C). In contrast, all zanamivir-containing regimens (the clinical monotherapy exposure, high monotherapy exposure, and oseltamivir/zanamivir combination regimen) prevented the replication of HK/09-H275Y throughout the duration of the study, maintaining levels of HK/09-H275Y that were comparable to the no-treatment control (Fig. 3D–F).

Figure 3.

Oseltamivir/Zanamivir combination therapy prevents the replication of oseltamivir-resistant viral subpopulations. The percentage of Mexico (red bars) and Hong Kong (blue bars) subpopulations were determined via pyrosequencing from supernatants harvested from the HFIM system with an initial mixed-viral infection (99% MK/09 + 1% HK/09-H275Y).

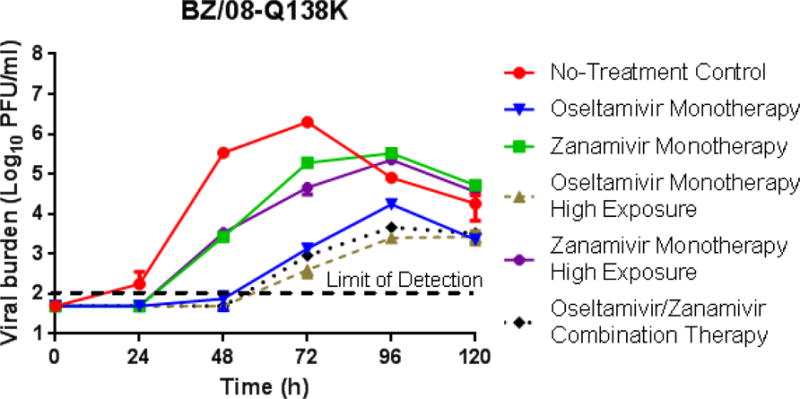

3.3. Oseltamivir and/or zanamivir treatment against influenza that is resistant to zanamivir

Oseltamivir and/or zanamivir regimens were also evaluated against BZ/08-Q136K to determine if combination therapy is effective at suppressing viruses that are resistant to zanamivir. In this case, zanamivir monotherapy at both exposure levels was unable to inhibit BZ/08-Q136K replication; however, treatment did delay replication kinetics and reduce peak viral titers (Fig. 4). Oseltamivir monotherapy was effective against BZ/08-Q136K, as viral titers in these arms were markedly lower than those reported for the no-treatment control and zanamivir monotherapy regimens (Fig. 4). Greater viral suppression was observed in the oseltamivir monotherapy high exposure arm compared to the standard clinical oseltamivir regimen. Oseltamivir/zanamivir combination therapy was also effective against BZ/08-Q136K and achieved a degree of viral inhibition that was comparable to the oseltamivir monotherapy high exposure regimen (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The effect of oseltamivir and zanamivir as mono- and combination therapy against a BZ/08-Q136K influenza virus which has reduced susceptibility to zanamivir. Viral burden was determined by plaque assay on MDCK cells. Each data point represents the mean of two independent samples and error bars correspond to one standard deviation.

4. Discussion

The emergence and spread of drug-resistant influenza viruses will compromise the effectiveness of our already limited influenza-therapeutic armamentarium. This danger was observed during the 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic, in which viruses resistant to amantadine, rimantidine, and oseltamivir were reported (CDC, 2009d; CDC, 2009c; CDC, 2009b; CDC, 2009a). These surveillance data provide evidence that current prophylactic and/or treatment regimens with influenza antivirals can occasionally select for the emergence and possible spread of resistance.

Previous reports have documented the presence of oseltamivir-resistant subpopulations at low levels in influenza infected individuals that have not received oseltamivir therapy (Ghedin et al., 2012). These findings have important implications for anti-influenza therapy, as we have demonstrated here that the current clinical regimen of oseltamivir (75 mg twice-daily) rapidly selects for oseltamivir-resistant subpopulations in a mixed viral infection that contains 1% of resistant virus at the start of treatment (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, we showed that oseltamivir monotherapy at an exposure that is 8-times higher than the clinical dose is also unable to inhibit drug-resistant viruses (Fig. 1C). It is important to note that our studies were conducted in an in vitro setting that is devoid of an immune system. If a functioning immune component was present, resistance would likely have been better contained. Our model more accurately represents influenza infections in immunocompromised individuals, a patient population in which resistant influenza is more prevalent. Nevertheless, these results highlight the shortcomings of the available influenza treatment regimens. In the absence of new antiviral agents for influenza, innovative therapeutic regimens with licensed compounds are needed to aid in the prevention of resistance. The objective of this study was to evaluate combination therapy with two available neuraminidase inhibitors as a means to suppress drug-resistant viruses.

Although oseltamivir and zanamivir target the same viral protein (the neuraminidase), they bind to the active site differently. Oseltamivir activity requires that the neuraminidase change shape to create a pocket that will accommodate the steric bulk of the drug. In contrast, zanamivir can bind directly into the active site without a conformational change (Moscona, 2005). These mechanistic differences illustrate that oseltamivir and zanamivir bind to distinct residues within the active site of the neuraminidase. However, since only one agent can occupy the active site at a time, the likelihood of obtaining increased viral suppression with the combination is low. The benefit to these binding differences is that the resistance profiles between oseltamivir and zanamivir do not overlap so that these agents may be used effectively to prevent resistance to either drug when used in combination. Our results substantiated both of these scenarios, as combination therapy was as effective as the most active monotherapy treatment and showed considerable activity against oseltamivir- and zanamivir-resistant viruses. Moreover, oseltamivir/zanamivir combination therapy was able to suppress the selection of oseltamivir-resistant viruses in a mixed infection model.

Due to its effectiveness against resistant viruses, combination therapy is likely to be more beneficial to standard monotherapy regimens, particularly during an influenza pandemic when a vaccine is not yet available and in a population of individuals who are at high risk for morbidity and mortality (i.e.: nursing homes, hospitalized patients, and immunocompromised individuals). Implementing this strategy could also preserve the clinical utility of neuraminidase inhibitors by preventing the spread of drug-resistant strains.

The feasibility of oseltamivir-zanamivir combination therapy has been evaluated in clinical trials with varying conclusions related to therapeutic outcomes. Carrat et al. (Carrat et al., 2012) demonstrated that combination therapy with oseltamivir and zanamivir was more effective than monotherapy at reducing influenza household transmission when administered to the index patient within 24h of symptom onset. This study analyzed a subset of patients that was part of a larger randomized placebo-controlled trial conducted by Duval et al. (Duval et al., 2010). Combination therapy in the Duval et al. study was less efficacious than oseltamivir monotherapy, but displayed similar levels of effectiveness compared to zanamivir monotherapy in patients infected with H3N2 influenza (Duval et al., 2010). These findings contrast with our results, as antiviral effectiveness was not compromised in the face of combination therapy in the HFIM system. The disparity in conclusions may be attributed several factors including differences in the route of administration for zanamivir, as we simulated profiles associated with i.v. administration whereas Duval et al. administered via inhalation with a rotadisk inhaler. The inhaler is difficult to operate and misuse can result in suboptimal drug concentrations at the infection site (Diggory et al., 2001), which may explain the lack of effectiveness in patients treated with zanamivir. Finally, the authors did stipulate that the results in the combination treatment arm may have been underestimated due to missing data points. A subset analysis was performed including only patients with available virological data and showed non-significant differences in effectiveness between combination therapy compared to oseltamivir monotherapy (p = 0.06), although patients treated with oseltamivir alone experienced a greater reduction in viral burden (~0.35-log10 cgeq/μl) than those treated with the combination (Duval et al., 2010). Viruses resistant to oseltamivir or zanamivir were not detected in this study.

A small clinical study (21 patients) reported that oral oseltamivir and inhaled zanamivir combination therapy failed to reduce influenza replication in patients with severe influenza pneumonia (Petersen et al., 2011). Monotherapy arms were not conducted as part of this evaluation, so therapeutic outcomes were not compared between combination and single agent regimens. The patients in this evaluation were critically ill, with nine patients requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Furthermore, combination therapy was initiated late in infection, which likely played a major role in lack of efficacy because neuraminidase inhibitors are most beneficial when administered within 48h of symptom onset. Oseltamivir-resistance was detected in one patient, but the patient ultimately cleared the resistant isolate.

Escuret et al. conducted another small clinical trial (24 patients) in which the effectiveness of oseltamivir/zanamivir combination therapy was compared to oseltamivir monotherapy in patients with 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza infections (Escuret et al., 2012). No significant differences in viral burden or clinical outcome were detected between treatment arms. Additionally, oseltamivir-resistant mutants were not detected in any patient at day 2 or 3 post-treatment in nasal wash samples using an assay with a limit of sensitivity of 10%. Resistance profiles at baseline were not conducted.

The value of oseltamivir/zanamivir combination therapy in regards to resistance suppression has yet to be defined. Studies conducted in mice have attempted to address this issue. Pizzorno et al. showed that the effectiveness of oseltamivir/zanamivir combination therapy was comparable to zanamivir monotherapy and significantly better than oseltamivir monotherapy in mice infected with oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 2009 pandemic influenza (Pizzorno et al., 2014). The findings from this study illustrate that oseltamivir is ineffective against an oseltamivir-resistant isolate, but that zanamivir is active against oseltamivir-resistant viruses in vivo whether alone or in combination. Our experiments build upon this study, as we evaluated the combination regimen against many different drug-resistant infection scenarios including, oseltamivir-resistant influenza, zanamivir-resistant influenza, and a mixed virus infection that contained low levels of oseltamivir-resistant influenza. Moreover, in our system we are able to simulate human pharmacokinetic profiles for both oseltamivir and zanamivir; this was not accomplished in the mouse model.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have shown that combination therapy with oseltamivir and zanamivir is an effective therapeutic strategy for preventing resistance with seasonal and pandemic influenza. We acknowledge that combination therapy with agents from different drug classes would be ideal, as enhanced antiviral activity as well as resistance suppression should occur with these regimens. Currently only neuraminidase inhibitors are approved for the treatment of influenza; but, new compounds (i.e.: favipiravir and pimodivir) with novel mechanisms of action are in clinical trials. We will evaluate combination therapy with these new agents as they become available. Until then, our results demonstrate the potential utility of combining two agents with the same mechanism of action but distinct binding profiles to the target protein to combat drug-resistance during antiviral therapy. This finding is novel for influenza and significant, considering that the emergence of resistance is a major challenge for this disease. These strategies should be tested for other viral and non-viral diseases for which multiple classes of anti-infective agents do not yet exist.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wadsworth Center Applied Genomic Technologies Core Facility for providing pyrosequencing.

Funding

This work was supported by grant R01-AI079729 from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). NIAID had no involvement in the study design, data collection, interpretation, writing of this manuscript, or the decision to submit this work for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Autran B, Carcelain G, Li TS, Blanc C, Mathez D, Tubiana R, Katlama C, Debre P, Leibowitch J. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science. 1997;277:112–116. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AN, Bulitta JB, McSharry JJ, Weng Q, Adams JR, Kulawy R, Drusano GL. Effect of half-life on the pharmacodynamic index of zanamivir against influenza virus delineated by a mathematical model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011a;55:1747–1753. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01629-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AN, McSharry JJ, Weng Q, Adams JR, Kulawy R, Drusano GL. Zanamivir, at 600 milligrams twice daily, inhibits oseltamivir-resistant 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus in an in vitro hollow-fiber infection model system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011b;55:1740–1746. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01628-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AN, McSharry JJ, Weng Q, Driebe EM, Engelthaler DM, Sheff K, Keim PS, Nguyen J, Drusano GL. In vitro system for modeling influenza A virus resistance under drug pressure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3442–3450. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01385-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrat F, Duval X, Tubach F, Mosnier A, van der Werf S, Tibi A, Blanchon T, Leport C, Flahault A, Mentre F. Effect of oseltamivir, zanamivir or oseltamivir-zanamivir combination treatments on transmission of influenza in households. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:1085–1090. doi: 10.3851/IMP2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. 2008–2009 Influenza Season Week 38 ending September 26, 2009. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009a. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Oseltamivir-resistant 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in two summer campers receiving prophylaxis–North Carolina, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009b;58:969–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Oseltamivir-resistant novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in two immunosuppressed patients - Seattle, Washington, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009c;58:893–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Use of influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2009. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009d;58:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong MD, Tran TT, Truong HK, Vo MH, Smith GJ, Nguyen VC, Bach VC, Phan TQ, Do QH, Guan Y, Peiris JS, Tran TH, Farrar J. Oseltamivir resistance during treatment of influenza A (H5N1) infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2667–2672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyde VM, Sheu TG, Trujillo AA, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Garten R, Klimov AI, Gubareva LV. Detection of molecular markers of drug resistance in 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) viruses by pyrosequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1102–1110. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01417-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggory P, Fernandez C, Humphrey A, Jones V, Murphy M. Comparison of elderly people’s technique in using two dry powder inhalers to deliver zanamivir: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322:577–579. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7286.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucette KE, Aoki FY. Oseltamivir: a clinical and pharmacological perspective. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2001;2:1671–1683. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2.10.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulek DE, Williams JV, Creech CB, Schulert AK, Frangoul HA, Domm J, Denison MR, Chappell JD. Use of intravenous zanamivir after development of oseltamivir resistance in a critically Ill immunosuppressed child infected with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1493–1496. doi: 10.1086/652655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval X, van der Werf S, Blanchon T, Mosnier A, Bouscambert-Duchamp M, Tibi A, Enouf V, Charlois-Ou C, Vincent C, Andreoletti L, Tubach F, Lina B, Mentre F, Leport C. Efficacy of oseltamivir-zanamivir combination compared to each monotherapy for seasonal influenza: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escuret V, Cornu C, Boutitie F, Enouf V, Mosnier A, Bouscambert-Duchamp M, Gaillard S, Duval X, Blanchon T, Leport C, Gueyffier F, van der Werf S, Lina B. Oseltamivir-zanamivir bitherapy compared to oseltamivir monotherapy in the treatment of pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus infections. Antiviral Res. 2012;96:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster GR, Afdhal N, Roberts SK, Brau N, Gane EJ, Pianko S, Lawitz E, Thompson A, Shiffman ML, Cooper C, Towner WJ, Conway B, Ruane P, Bourliere M, Asselah T, Berg T, Zeuzem S, Rosenberg W, Agarwal K, Stedman CA, Mo H, Dvory-Sobol H, Han L, Wang J, McNally J, Osinusi A, Brainard DM, McHutchison JG, Mazzotta F, Tran TT, Gordon SC, Patel K, Reau N, Mangia A, Sulkowski M. Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for HCV Genotype 2 and 3 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2608–2617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1512612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gane EJ, Stedman CA, Hyland RH, Ding X, Svarovskaia E, Symonds WT, Hindes RG, Berrey MM. Nucleotide polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for hepatitis C. N. Engl. J Med. 2013;368:34–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghedin E, Holmes EC, DePasse JV, Pinilla LT, Fitch A, Hamelin ME, Papenburg J, Boivin G. Presence of oseltamivir-resistant pandemic A/H1N1 minor variants before drug therapy with subsequent selection and transmission. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1504–1511. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GlaxoSmithKline. Zanamivir investigator’s brochure 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Hayden FG. Antiviral resistance in influenza viruses–implications for management and pandemic response. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:785–788. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden FG, Cote KM, Douglas RG., Jr Plaque inhibition assay for drug susceptibility testing of influenza viruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;17:865–870. doi: 10.1128/aac.17.5.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt AC, Holien JK, Parker M, Kelso A, Barr IG. Zanamivir-resistant influenza viruses with a novel neuraminidase mutation. J Virol. 2009;83:10366–10373. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ison MG, Gubareva LV, Atmar RL, Treanor J, Hayden FG. Recovery of drug-resistant influenza virus from immunocompromised patients: a case series. J Infect Dis. 2006a;193:760–764. doi: 10.1086/500465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ison MG, Mishin VP, Braciale TJ, Hayden FG, Gubareva LV. Comparative activities of oseltamivir and A-322278 in immunocompetent and immunocompromised murine models of influenza virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2006b;193:765–772. doi: 10.1086/500464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larder BA, Kemp SD, Harrigan PR. Potential mechanism for sustained antiretroviral efficacy of AZT-3TC combination therapy. Science. 1995;269:696–699. doi: 10.1126/science.7542804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TC, Chan MC, Lee N. Clinical Implications of Antiviral Resistance in Influenza. Viruses. 2015;7:4929–4944. doi: 10.3390/v7092850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz M, Nguyen BY, Gotuzzo E, Mendo F, Ratanasuwan W, Kovacs C, Prada G, Morales-Ramirez JO, Crumpacker CS, Isaacs RD, Campbell H, Strohmaier KM, Wan H, Danovich RM, Teppler H. Sustained antiretroviral effect of raltegravir after 96 weeks of combination therapy in treatment-naive patients with HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:350–356. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b064b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz M, Nguyen BY, Gotuzzo E, Mendo F, Ratanasuwan W, Kovacs C, Prada G, Morales-Ramirez JO, Crumpacker CS, Isaacs RD, Gilde LR, Wan H, Miller MD, Wenning LA, Teppler H. Rapid and durable antiretroviral effect of the HIV-1 Integrase inhibitor raltegravir as part of combination therapy in treatment-naive patients with HIV-1 infection: results of a 48-week controlled study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:125–133. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318157131c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty FM, Man CY, van der Horst C, Francois B, Garot D, Manez R, Thamlikitkul V, Lorente JA, Alvarez-Lerma F, Brealey D, Zhao HH, Weller S, Yates PJ, Peppercorn AF. Safety and pharmacokinetics of intravenous zanamivir treatment in hospitalized adults with influenza: an open-label, multicenter, single-arm, phase II study. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:542–550. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki Y, Mizuta K, Aoki Y, Suto A, Abiko C, Sanjoh K, Sugawara K, Takashita E, Itagaki T, Katsushima Y, Ujike M, Obuchi M, Odagiri T, Tashiro M. A two-year survey of the oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1N1) virus in Yamagata, Japan and the clinical effectiveness of oseltamivir and zanamivir. Virol J. 2010;7:53. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSharry JJ, Weng Q, Brown A, Kulawy R, Drusano GL. Prediction of the pharmacodynamically linked variable of oseltamivir carboxylate for influenza A virus using an in vitro hollow-fiber infection model system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2375–2381. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00167-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscona A. Oseltamivir resistance–disabling our influenza defenses. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2633–2636. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen E, Keld DB, Ellermann-Eriksen S, Gubbels S, Ilkjaer S, Jensen-Fangel S, Lindskov C. Failure of combination oral oseltamivir and inhaled zanamivir antiviral treatment in ventilator- and ECMO-treated critically ill patients with pandemic influenza A (H1N1)v. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43:495–503. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.556144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzorno A, Abed Y, Rheaume C, Boivin G. Oseltamivir-zanamivir combination therapy is not superior to zanamivir monotherapy in mice infected with influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses. Antiviral Res. 2014;105:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard M, Ferraris O, Erny A, Barthelemy M, Traversier A, Sabatier M, Hay A, Lin YP, Russell RJ, Lina B. Combinatorial effect of two framework mutations (E119V and I222L) in the neuraminidase active site of H3N2 influenza virus on resistance to oseltamivir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2942–2952. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01699-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu TG, Deyde VM, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Garten RJ, Xu X, Bright RA, Butler EN, Wallis TR, Klimov AI, Gubareva LV. Surveillance for neuraminidase inhibitor resistance among human influenza A and B viruses circulating worldwide from 2004 to 2008. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3284–3292. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00555-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashita E, Ejima M, Itoh R, Miura M, Ohnishi A, Nishimura H, Odagiri T, Tashiro M. A community cluster of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus exhibiting cross-resistance to oseltamivir and peramivir in Japan, November to December 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014:19. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.1.20666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe A, Yates PJ, Murayama M, Soutome T, Furukawa H. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of intravenous zanamivir in the treatment of hospitalized Japanese patients with influenza: an open-label, single-arm study. Antivir Ther. 2015;20:415–423. doi: 10.3851/IMP2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuzem S, Soriano V, Asselah T, Bronowicki JP, Lohse AW, Mullhaupt B, Schuchmann M, Bourliere M, Buti M, Roberts SK, Gane EJ, Stern JO, Vinisko R, Kukolj G, Gallivan JP, Bocher WO, Mensa FJ. Faldaprevir and deleobuvir for HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:630–639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]