Abstract

Despite attempts to increase enrollment of under-represented minorities (URMs: primarily Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Native American students) in health professional programs, limited progress has been made. Compelling reasons to rectify this situation include equity for URMs, better prepared health professionals when programs are diverse, better quality and access to health care for UMR populations, and the need for diverse talent to tackle difficult questions in health science and health care delivery. However, many students who initiate traditional pipeline programs designed to link URMs to professional schools in health professions and the sciences, do not complete them. In addition, program requirements often restrict entry to highly qualified students while not expanding opportunities for promising, but potentially less well-prepared candidates. The current study describes innovations in an undergraduate pipeline program, the Health Equity Scholars Program (HESP) designed to address barriers URMs experience in more traditional programs, and provides evaluative outcomes and qualitative feedback from participants. A primary outcome was timely college graduation. Eighty percent (80%) of participants, both transfer students and first time students, so far achieved this outcome, with 91% on track, compared to the campus average of 42% for all first time students and 58–67% for transfers. Grade point averages also improved (p=.056) after program participation. Graduates (94%) were working in health care/human services positions and three were in health related graduate programs. Creating a more flexible program that admits a broader range of URMs has potential to expand the numbers of URM students interested and prepared to make a contribution to health equity research and clinical care.

Keywords: Health professions, diversity, health equity, underrepresented students

Introduction

Despite attempts to increase enrollment of under-represented minorities (URMs: primarily Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Native American students) in health professional programs, many agree that limited progress has been made. [1, 2, 3] There are a number of compelling reasons to rectify this situation. First, limited access of the growing U.S. non-white population to professional opportunities is a matter of equity and justice. [4] Second, there is evidence that more diverse students, and addressing issues of diversity and culture in health professional training, prepares all participants to better serve our changing population. [4, 5] Third, racial and ethnic groups have a disproportionate burden of disease and disparities in health care access and quality [6], yet have also made significant contributions to science and medicine, albeit not always voluntarily. For example, Blacks/African Americans have contributed major advances in blood transfusion, heart surgery, and the untold benefit of the use of HeLa cells for biomedical research [7, 8]. Thus there is a large potential loss of valuable contributions when diversity is lacking. Also, given that a greater percentage of URM professionals provide services to minority communities, and are better prepared to initiate clinical and community intervention research with such communities, increasing the numbers of URMs in the health care and biomedical workforce can help to address both research and clinical care disparities. [5, 9]

Different approaches to increase diversity in the biomedical and health professions have been attempted, yet URMs still obtain a disproportionately small portion of doctoral degrees in the sciences and public health [2,3,10] and remain only a small portion of NIH grantees [8,11] or medical or public health faculty. [5, 9, 12] Importantly, efforts of various institutions to increase minority representation may result in competing for the same small pool, which results in no net increase in the overall representation of URMs in the health professions.[4] Some have characterized the problem as a leaky pipeline, e.g. that URMs start down the pathway to obtaining college and professional degrees in the health sciences, but disproportionately withdraw. [13–15] Research on lack of URM success identifies a number of factors, including poor pre-college academic preparation, less effective study habits and test-taking skills, lack of financial aid, family responsibilities, lack of mentoring and role models, peer and faculty discrimination, unconscious bias, stereotype threat, and social isolation. [2,11,12,16–20] While these factors play a role, another possibility is that we are using the wrong approach to both construct programs and measure success. [14] James et al. [14] suggest that traditional pipeline training models may limit or overlook what can be gained by redefining success as preparing students for a range of public health and research careers, even those who do not ultimately obtain doctorates or clinical degrees. The current study reports a framework to develop an undergraduate Health Equity Scholars Program (HESP) to improve diversity in health professions that matches the principles indicated by James et al. The UMMS Institutional Review Board reviewed this study and found it to not meet the definition of human subjects research.

Objectives

The HESP program (Table 1) was designed to target the leaky pipeline by identifying and addressing barriers by involving students and four on-campus ethnic institutes in planning, implementing, and ongoing evaluation of the program. The main objective was to foster undergraduate degree completion for URM students in health and science majors within 6 years, through providing extracurricular seminars, mentoring, an elective course, and opportunities for lab-based or community-based health equity research. A secondary goal was to assist them in enrolling in health-related graduate programs or linking to employment in community-based research, health services, or advocacy. The program was designed for 12–15 students a year.

Table 1.

HESP Program Activities

| Area of support | Activity | Details |

|---|---|---|

| ACADEMIC ENRICH | All day field trip to UMMS |

|

| Coursework |

|

|

| Extracurricular seminars |

|

|

| Paid summer research opportunities |

|

|

| Academic support |

|

|

| MENTOR | Peer mentoring |

|

| Faculty mentoring |

|

The ethnic institutes were established to conduct multidisciplinary research, provide campus-based and community educational activities and events, and advocate for issues of concern to the diverse ethnic communities in the area. They include the Institute for Asian American Studies (IAAS) (www.umb.edu/iaas), the Institute for New England Native American Studies (INENAS) (www.umb.edu/inenas), the Mauricio Gastón Institute for Latino Community Development and Public Policy (Gastón Institute) (www.umb.edu/gastoninstitute), and the William Monroe Trotter Institute for the Study of Black Culture (Trotter Institute) (www.umb.edu/trotter).

Methods

Program Planning

HESP is a program component of the Center for Health Equity Intervention Research (CHEIR), a joint endeavor between University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS) and the system s urban campus, University of Massachusetts Boston (UMB) located 45 miles apart. UMB is a Carnegie Research II university enrolling 17,300 students and is the most diverse public four-year higher education institution in New England. It is a nonresidential campus. Undergraduates consist of 55% students of color (20% Black and 17% Hispanic); 61% are first-generation college students; and 53% speak a language other than English at home. More than half the students are transfer students (52%) and 58% are women. CHEIR was funded by a center grant from the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Table 1 outlines the program activities offered annually. The activities and eligibility criteria were developed in conjunction with the ethnic institute advisory committee to meet the specific needs of nontraditional students and to utilize the evidence-based and local knowledge. Important factors were creating connections to faculty, providing peer support, academic support, and service learning and research experiences that have been found to foster engagement in college that supports retention. [21, 22] Elements of a successful model on campus, the Latino Leadership Opportunity Program , which provides a for-credit seminar on Latino demographics, characteristics, and disparities, and hands on research projects were also utilized. For example, a required 3-credit general education course was developed specifically for the HESP students each year providing an introduction to understanding disparities and social determinants of health. Students also experience defining a local health equity issue, either by working with a community group, or completing a community health assessment of a Boston neighborhood using data from the Boston Public Health Commission s annual reports on neighborhood health.

The seminar activities focused on topics of particular relevance to URMs or on concrete academic/career skills. For example, seminars included: 1) presentations of faculty or other student s community-based research for which students were asked to contribute ideas; 2) local or national leaders in health disparities work who talked about their careers; 3) readings about issues in identifying race/ethnicity in contributing to addressing barriers or quality in health care. Career topics included how to write abstracts and develop posters for scientific meetings, how to write application letters for summer programs and graduate school, and practicing the multiple mini-interview that is now used in medical school admissions. After the first year, students were encouraged to continue to attend seminars and summer research through graduation.

Student Recruitment

We targeted students that not only were doing well (3.0 or above GPA), but those that were promising but struggling (2.5 GPA). We also made obtaining faculty recommendations less burdensome by designing a checklist form that could be completed by faculty who only knew students through course attendance, since freshman, sophomores, and transfer students rarely have the opportunity to participate in small seminar courses or do independent studies where a close relationship with a faculty member is possible. Third, we connected the program to the student s lives by asking them to write a brief essay on a health disparity issue they were concerned about. Finally, we targeted second semester freshman and sophomores, and early transfer students, so that students would have the opportunity to gain benefit from HESP for several years. Recruitment consisted of distributing flyers, and information to faculty, the ethnic institutes staff, and providing information at campus activity fairs and in the student newspaper.

Program Evolution

The program was initially administered jointly by the Gastón Institute, the Trotter Institute, and INENAS. Students were encouraged to join one of the CHEIR core research studies based at UMB, and to link with UMMS projects in addition to the required course and periodic special seminars. A feedback form was utilized for students to provide information about their experience with each activity of the program that included questions on how much they were learning about health disparities, about research, and about their own career development. They were also asked for suggestions for program improvement and other activities they would be interested in. While uniformly extremely positive about the program, based on this continuous feedback and conducting informal student feedback sessions at the end of each semester, it was determined that students found the required course very challenging and needed more academic support for writing and critical thinking skills. In addition, more opportunities for hands on research were needed because students could not travel to UMMS for logistical and financial reasons to participate in research projects, and only a few could work with the one CHEIR study based at UMB.

The program was then moved to the Academic Support unit of the campus where tutoring, advising, and links to other student research programs provided additional resources. Funds were also reallocated to sponsor student summer research stipends at UMB on projects focused on health disparities research solicited from UMB faculty, with a particular goal to target junior URM faculty. Importantly, the summer research stipends were flexible and covered as little as 10 hours a week, so that students who had to work or attend summer classes could still obtain research experience. The Advisory Group also expanded from the initial institutes to include others (the Dean of the Honors College, the Dean of Academic Support, the Director of the Undergraduate Nursing Program, the Director of IAAS, and several faculty with expertise in issues of health equity).

Program Challenges

In addition to addressing the need for local, flexible research experience opportunities, we found that the student seminars designed for mentoring and career development also had to be flexible on a campus that does not provide student housing, where many students had family responsibilities, and most were financing their own education by working. Programming had to grapple with odd meeting times to accommodate schedules (e.g. evenings, intersession days), and keeping the right balance of enough, but not too many activities, so that students weren t discouraged from applying or continuing. We also found it hard to reach out to lower division students who typically do not know faculty and are not as well connected to campus. Many applicants were transfer students with upper division standing (also not well connected to campus), reflecting that the campus has more transfer students (52%) than first time freshman (48%). Thus we modified our acceptance criteria to be inclusive of students who could participate for at least one year before graduation.

Program Metrics

In addition to the activity feedback forms and the course evaluations the program tracked grade point average (GPA), research experience participation, graduation rates, and post-graduation status.

Outcomes

Participants

HESP enrolled 53 students over the past 4 years, meeting the target of 12–15 students joining each year. Nine students who applied were not accepted and an additional 6 students started but did not complete applications. Reasons for not accepting students were: low GPA combined with poor faculty recommendation (n=4); second semester senior (n=3); lack of focus on health disparities in application (n=1); not qualified as an URM (n=1). Table 2 and Figure 1 describe the demographic and academic background of the students. Compared to a campus enrollment of 30% Black and Latino, 73% were Black or Latino. In addition, there were many with multiple ethnicities, and they represented 26 countries of family origin (first or second generation) and several Native American tribes (Abenaki, Blackfoot, Cherokee). While 58% of the campus enrollment was female, HESP enrollment was 85% female. A large proportion (n=24, 45.3%) were transfer students and of these, over half were upper division transfers (n=15).

Table 2.

Demographics of participating students, N=53

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Gender-Female | 45 (85%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| African/African American | 23 (43.4%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 16 (30.2%) |

| Asian | 6 (11.3%) |

| Native American* | 4 (7.5%) |

| White/other multiracial | 4 (7.5%) |

|

| |

| Majors | |

| Biology or Biochemistry | 17 (32.1%) |

| Psychology | 14 (26.4%) |

| Nursing | 11 (20.8%) |

| Exercise Science/Health | 3 (5.7%) |

| Anthropology | 3 (5.7%) |

| Undeclared | 3 (5.7%) |

| Computer Science | 1 (1.9%) |

| Business | 1 (1.9%) |

|

| |

| GPA Mean and Range | M=3.31 (range 2.2–4.0) |

|

| |

| Year of First Participation | |

| Sophomore | 11 (20.7%) |

| Junior | 21 (39.6%) |

| Senior | 21 (39.6%) |

Three students identified as part-Native American and one indicated solely Native American heritage but a combination of different tribes.

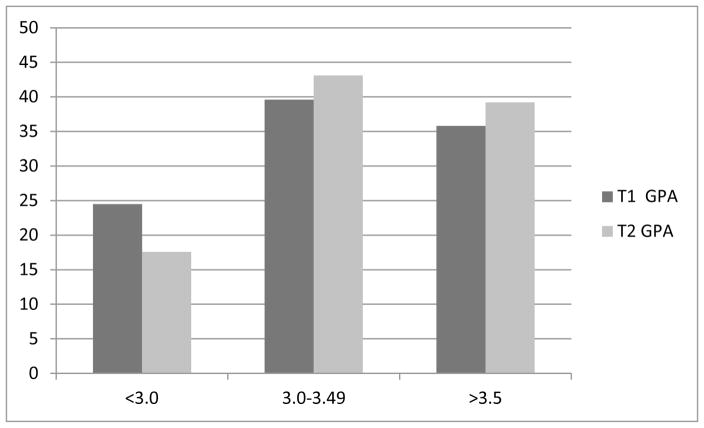

Figure 1.

Grade point average (GPA) of enrolled HESP participants at time of acceptance, (N=53) and one year later or at graduation (n=51)*

*Note: we had records of entry GPA, but were not able to locate for follow-up GPA two student files in the institutional records system, one graduate and one dropout.

Participants also already had deep connections to the health care field. Almost 72% (n=38) reported working or volunteering in health care or having completed an internship or campus-linked research experience at a hospital. Almost a quarter (n=11, 21%) were Certified Nursing Assistants and almost all of these students were supporting themselves to pay for school by considerable hours working in local health care facilities. Another 17% (n=9) were employed as EMTs, radiology techs, medical assistants, medical secretaries or administrators, while three (6%) were employed as a clinical research coordinator, a biology lab tech, and a veterinary assistant, again out of need to provide income for self-support and college expenses. Nine (17%) did volunteer work at local hospitals such as patient escorts. Six students (11%) had already completed a National Institutes for Cancer research internship through a campus partnership with the Dana Farber Cancer Center. While we do not have specific information about how many students were contributing financially to their families in addition to supporting themselves, 43% (n=23) did report in their applications having such family care giving responsibilities as caring for younger siblings, including siblings with disabilities, and caring for parents or grandparents with cancer, Alzheimer s, diabetes, etc., including providing bathing, feeding, injections, and other types of direct care activities.

Summer research

Table 3 describes the HESP-funded and other summer research activities students have participated in. In total we were able to facilitate hands on research experience for 27 students (51%) (this is not including students who prior to HESP participation had participated in the NCI/Dana Farber program). Due to increasing funds and links to other campus opportunities as program adjustments were made, the proportion of students able to participate in summer research grew considerably from year 1 (26.7%) to year 2 (50%), and year 3 (93%). In year 4, 77% participated. Even though the hourly commitment was flexible, reasons for not participating in summer research were need to work at ongoing jobs to support themselves or family (such as CNA positions), summer school schedules, or need to provide care of family members (e.g. a mother with cancer). None of the students who dropped out participated in summer research. While we did allow participation the summer after graduation if a student had not previously been able to participate in a research project, most needed full time work and were not able to complete a part time or few week summer program.

Table 3.

Research projects funded by HESP or participated in by HESP students.

| Funding Source | Mentor | Project/Poster Title |

|---|---|---|

| HESP | ||

| UMB Institute for New England Native American Studies | 2 students: 2014 summer Health needs of Native peoples and urban Indians of New England |

|

| UMB Trotter Institute for the Study of Black Culture | 1 student: 2014 summer Sexual harassment and black girls: A literature review |

|

| UMB College of Education-Counseling Program | 1 student: 2014 summer Latino patient’s perceptions about prostate and breast cancer screening: implications for the USA nursing curricula |

|

| UMB Institute for Asian American Studies | 1 student: 2014 summer Lack of treatment for gambling disorders in a Vietnamese community |

|

| UMB College of Nursing | 1 student: 2015 summer Collaboration and teams sciences for health services |

|

| UMB Dept of Psychology | 1 student: 2015 summer Addressing health disparities in autism spectrum disorders |

|

| UMB Trotter Institute for the Study of Black Culture | 1 student: 2015 summer Assessing health needs of African immigrant communities in Boston |

|

| UMB Trotter Institute for the Study of Black Culture | 1 student: 2015 summer African heritage/black grandparents WIC nutrition study: A needs assessment of the nutritional education needs of ethnic minority grandparents of WIC children ages 1–5 years old in MA |

|

| UMB College of Nursing | 1 student: 2015 summer A videoconferencing smoking cessation intervention for Korean American women |

|

| UMB College of Public and Community Service | 1 student: 2015 summer The effects of location on health outcomes among Puerto Ricans |

|

| UMB Gerontology Institute | 1 student: 2015 summer Self-reported health access to health care services and English spoken at home: A study among older residents in Boston |

|

| UMB College of Nursing | 1 student: 2015 summer A culturally sensitive approach towards Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease prevention in American Indian women with a history of gestational diabetes |

|

| CHEIR-Core research project | Gastón Institute | 6 students total, 2012–2016 summer and academic year, field work, transcription, data entry; 3 not participating in other research Por Ahí Dicen: Evaluating the Effectiveness of a Spanish Media PSA Campaign to Promote Puerto Rican Mother-Child Communication about Sexuality |

| Univ. of Mass Medical School | ||

| UMMS Office of Outreach Programs | 1 student: 2015 summer BACC-MD summer residential program |

|

| UMMS Office of Outreach Programs | 2 students: 2015 summer Summer Enrichment Program |

|

| NCI U54/CURE (Continuing Umbrella of Research Experiences) and other sponsors | ||

| U54 UMB-Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Research Partnership | 1 student: 2015 summer Novel warhead synthesis for BRD4 and BRDT bromodomain inhibition in vitro |

|

| Harvard Medical School | 1 student: 2015 summer Pig cloning and CRISPR-Cas9 screening for xenotransportation |

|

| CURE-Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Research Partnership | 1 student: 2015 summer Barriers to cancer care among black Bostonians |

|

| U54 UMB-Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Research Partnership | 1 student:2015 summer Assessing health needs and developing programming in a Black church-is it sustainable. |

|

| U54 UMB-Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Research Partnership | 1 student; 2015 summer Does educational material act as an incentive in increasing minority participation in biobanks? |

Grade Point Average (GPA)

Figure 1 shows the distribution of entering GPAs and a follow-up GPA at the end of the first year after program participation, or GPA at graduation for those who have graduated. It can be seen that the distribution shifted toward higher GPAs after program participation. The mean follow-up GPA of 3.37 (SD= .42) was higher (and marginally significant) compared to the entry GPA (M=3.31,SD=.46, p=.056). This represents a small but meaningful effect size (ES=.27) in improvement in GPA for program participants and more students had GPAs of at least 3.0 at follow-up than at program entry. Overall 53% of students improved their GPA, while another 4% remained unchanged but above 3.5. While this means 43% of the GPAs decreased, many of the decreases were small (example 3.70 to 3.69 or 2.98 to 2.93), and we were not able to analyze for course difficulty as students progress to upper division and more demanding coursework.

Graduation rate and post-graduation status

At this time only 20 students have graduated, but 80% (20 of 25 students) met the criterion of finishing the BA degree within 6 years of enrollment (4 years for transfer students). (Five students withdrew or dropped out of UMB before graduation, 1 male and 4 female. All of these were in the first two years of the program). Known reasons for dropping out were low GPA, problems with commuting distance, and a family move out of state. This degree completion rate is almost double the campus average of 42% (45.4% for female students), and more than double that of all UMB US students of color (37%). [23, 24] None of the remainder of 28 HESP students have dropped out, and all are on target for timely graduation, which would yield a 91% timely graduation rate. Significantly, although many of the HESP students were upper-division transfers, the transfer student 4-years after enrollment graduation rates at UMB ranged from 58%–67% in recent years. Thus HESP participants are showing increased retention and timely graduation compared to other UMB students by UMR status, gender, and transfer status. [24]

Post-graduation status is summarized in Table 4. Of the 20 graduates, we were not able to locate four students. The 16 students followed post-graduation are almost all (94%) working in health care/human services related employment, while three are currently enrolled in graduate programs (NP, MPH, post-BACC) and three are currently applying for graduate or medical school. .

Table 4.

Post-graduation status of students participating in HESP (n=20)

| Work status (n, %) | Job titles or location | Post-graduate Education status (n/%)* |

|---|---|---|

| RN nursing position (5,25%) |

|

NP program Johns Hopkins School of Nursing (1, 5%) |

| Human services/health (5, 25%) |

|

Post BACC Program Mississippi College (1, 5%) MPH Program, Thomas Jefferson College (PA) (1, 5%) |

| UMass Boston administrative/RA positions (2, 10%) |

|

|

| Research lab (2, 10%) |

|

|

| Unrelated work (1, 5%) | unknown | Applying: 1 MPH program,1 medical school, 1 Masters in Psychology program |

| Unknown/lost to follow-up (4, 20%) |

not mutually exclusive from employment status

Student feedback

We conducted discussion groups at the end of each year. Written notes were taken by two staff members and themes developed and compared until consensus was reached. Three major themes were, 1) excitement about studying issues affecting their own communities; 2) being intimidated by the idea of contributing to research, and 3) also feeling honored and grateful for the seminars and speakers. At the beginning, while finding the newly developed course challenging, students appreciated that the content was on their own communities and that they could make a difference. Some noted, however, they were afraid of research because they did not feel prepared or smart enough.

Individual interviews about summer research were also conducted with 13 of the 27 students who participated. Importantly, only three of the students indicated they would have participated in summer research if not encouraged by HESP. They cited employment and summer course barriers, and lacked understanding of how such opportunities would help them be more competitive for graduate or medical school. More than half of the students indicated that the research experience changed their idea of a career. “ I realized that I want to implement plans that could affect population health.” “..being able to advocate for minorities when necessary now that I know so much more…” “I am considering an extra component in community research in my medical career.” Two students specifically said they now plan to apply to MPH programs.

When asked about the benefits of participating in research, many cited that it was learning “beyond books” and it helped them to be more focused in their studies. One student said it helped her morale and others said participating in HESP improved their grades. One student said, “ I learned how research worked, but also that research is not easy.” Another student summed up the feelings of many by saying: “ ..the HESP program kept me motivated and made me more determined to work my absolute hardest toward my goals of working in the health care sector with dreams of helping to reduce population related disparities.”

Conclusions and Recommendations

The HESP program addresses the need to increase the diversity of the health services and research work force by providing a more flexible and tailored program than traditional pipeline programs that often have rigid entrance and participation requirements that limit nontraditional URM student s ability to take advantage of them. For example, students working to support themselves or family members can t easily give up a long term Certified Nurse Assistant job for full time summer research of a few weeks. Such students also have little time for extracurricular activities. Others who come from less rigorous high schools, often have lower early college GPAs but do better as they gain skills and feel more connected to college. Lack of connection to college (such as by not participating in extracurricular activities), and low GPAs, are both predictors of college drop-out, or lengthy completion rates. Yet the early results from the HESP program show success in increasing timely bachelor s degree completion, increasing GPA, and assisting students to link to health related post-graduate programs and employment. The program bears out the existing literature about the value of connecting undergraduate students at risk of not completing their bachelors degree to programs that provide cultural connections, academic support, and faculty and peer mentoring to improve college engagement and success. [21, 22] We were also able to show that as program improvements were made, student retention rates and participation in extramural research opportunities increased. Continued tracking and documentation of new and ongoing students, as well as graduates for up to 5 years post-degree, will be essential to confirm these early results.

The innovations the program implemented (scheduling, nontraditional research opportunities, community-based focus of the course and research projects) appear to open a broader net and prevent such a leaky pipeline by adapting program elements to the specific needs of URMs and other disadvantaged students who are interested in health careers and disparities research. The program exemplifies the points made by James et al. [14] about the need to change the definition of success, as well as the need to modify traditional programs that tend overlook some URM students (due to low GPAs) or to drop them out over time due to a mismatch with student needs. In particular, by connecting students to coursework and hands on community-based research projects focused on health disparities, student became more motivated to complete and continue their education, and doors were opened to incorporating disparities research into their careers. A future challenge will be identifying staff resources to sustain the level of support and coordination needed to deliver the program as the NIMD grant phases out, in addition to funding for student summer research stipends. The campus has already applied for several other NIH grants to sustain these activities.

Interestingly, the program attracted female than male applicants, even compared to the campus demographics of females and males.. This may mean that male UMRs are even more disconnected from campus life than are females in a nonresidential setting, and thus harder to reach, or that fewer males are interested in careers in health care or disparities research. However, it is also true that the majority of the faculty and administrators involved in developing and advising HESP were female and this may have influenced outreach to the UMB population. Improving outreach to male students and continuing to raise enough funding to provide summer research experience for as many students as possible will strengthen the program.

We believe that adapting the program to the unique needs of participants, while still providing high quality activities, improved self-efficacy that extended to both performance in school (as exemplified by the 80% graduation rate and a meaningful improvement in GPA) and refocusing of career goals. Byars-Winston et al. [25] suggest that the key construct that creates success for URMs in science careers is self-belief that they can do the work and contribute to the field. The critical role of direct involvement of undergraduates with research to foster self-efficacy cannot be underestimated. Lopatto [26], for example, surveyed students from 41 institutions participating in Howard Hughes Medical Institute-funded summer research and found participation in research helped with retention in science majors, and affected plans for post-graduate science or medical school careers across ethnicity and gender. This was facilitated by research mentors providing constructive feedback, conveying how to overcome obstacles, facilitating independent work, and making participants feel included, all factors mentioned by HESP participants as contributing to their positive research internship experiences.

An important dimension of HESP was to admit students who were not already demonstrating high levels of academic achievement based on GPA. A study by Alexander, et al. [13], found that URMs get lower undergraduate grades but persist at higher rates than white students (with higher grades) to complete 4 or more science courses. Thus they advocate for supporting URMs regardless of grades. The focus on only top tier students for pipeline programs has been noted as limiting. [3, 27] Without adapting and expanding pipeline programs to the growing number of URMs in post-secondary education, and implementing innovations that meet their needs, we will not be successful in addressing the critical need for a more diverse health services and health research workforce.

Acknowledgments

The development of the HESP program was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (1 P60 MD006912) to the Center for Health Equity Intervention Research at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Jeroan Allison, MD, MPH, Professor and Vice Chair, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences and Associate Vice Provost for Health Disparities Research, PI; and Milagros Rosal, PhD, Professor, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, Co-PI. We wish to thank the many students, staff and faculty who contributed to the development of the program over the last four years and especially to staff who assisted with many different aspects of the program: Chioma Nnaji, MPH, CHEIR Program Director, Elizabeth de la Rosa, BA, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health Research Assistant, and Yvonne Gomes Santos, BA, Director of Public Affairs, Trotter Institute, UMass Boston,

References

- 1.Bond ML, Cason Cl, Baxley SM. Institutional support for diverse populations: Perceptions of Hispanic and African American students and program faculty. Nurse Educator. 2015;40:134–138. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreuter MW, Griffith DJ, Thompson V, Brownson RC, McClure S, Sharff DP, Clark EM, Haire-Joshu D. Lessons learned from a decade of recruitment and training to development minority health professionals. Am J Public Health. 2001;101:S188–S195. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grumbach K, Mendoza R. Disparities in human resources addressing the lack of diversity in the health professions. Health Aff. 2008;27:413–422. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman LA, Pollock R, Johnston, Thompson MC. Increasing the pool of academically oriented African American medical and surgical oncologists. Cancer. 2003;97(1 Suppl):329–334. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vela MB, Kim KE, Tang H, Chin MH. Improving undergraduate minority medial student recruitment with health disparities curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 2):82085. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newsome F. Black contributions to the early history of Western medicine: lack of recognition as a cause of Black under-representation in US medical schools. JAMA. 1979;71:189–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson WE, Pattillo RA, Stiles JK, Schattan G. Biomedical research s unpaid debt. EMBRO Reports. 2014;15:333–337. doi: 10.1002/embr.201338274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terrell C, Beaudreau J. 3000 by 2000 and beyond: Next steps for promoting diversity in the health professions. J Dental Ed; 67:1048–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Encouraging minority scientists. Nat Immunol. 2009:927. doi: 10.1038/ni0909-927. Editorial. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ginther DK, Schaffer WT, Schnell J, Masimore B, Liu F, Haak LL, Kington R. Race, ethnicity and NIH research awards. Science. 2011;333:1015–1019. doi: 10.1126/science.1196783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valantine HA, Collins FS. National Institutes of Health addresses the science of diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:12240–122402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515612112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander C, Chen E, Grumbach K. How leaky is the health career pipeline? Minority student achievement in college gateway courses. Acad Med. 2009;84:797–802. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a3d948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James R, Starks H, Segrest VA, Burke W. From leaky pipeline to irrigation system: Minority education through the lens of community-based participatory research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2012;6:471–479. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barr DA, Gonzalez ME, Wanart SF. The leaky pipeline: Factors associated with early decline in interest in premedical studies among underrepresented minority undergraduate students. Acad Med. 2008;83:503–511. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bda16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bond ML, Cason Cl, Baxley SM. Institutional support for diverse populations: Perceptions of Hispanic and African American students and program faculty. Nurse Educator. 2015;40:134–138. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boaten BA, Thomas B. How can we ease the social isolation of underrepresented minority students. Acad Med. 2011;86:1190. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822be60a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walton GM, Cohen GL. A brief social belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science. 2011;331:1447–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.1198364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nugent KE, Childs G, Jones R, Cook P. A mentorship model for retention of minority students. Nurs Outlook. 2004;52:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odom KL, Morgan Roberts L, Johnson RI, Cooper LA. Exploring obstacles to and opportunities for professional success among ethnic minority medical students. Acad Med. 2007;82:146–158. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8f2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalsbeek DH. Reframing Retention Strategy for Institutional Imprvements: Newt Directions for Higher Education. 161. San Francisco: Josey-Bass-Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Education. [Accessed 4/1/2017];Promising and Practical Strategies to Increase Post-Secondary Success. www.ed.gov/college-completion/promising-strategies/tages/retention.

- 23.Office of Institutional Research and Policy Studies. Executive Summary. University of Massachusetts; Boston: 2014. [Accessed March 2, 2016]. The six-year graduation rate of the Fall 2008 cohort of first-time full-time freshman. Downloaded from: https://www.umb.edu/oirap/retention_graduation. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graduation Rates Work Group. Report. University of Massachusetts; Boston: May 4, 2011. Building a Culture and Systems that Support Student Success: A plan for Significantly Improving Undergraduate Retention and Graduation Rates at UMass Boston. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byars-Winston AM, Branchaw J, Pfund C, Leverett P, Newton J. Culturally diverse undergraduate researcher s academic outcomes and perceptions of their research mentoring relationships. Int J Sci Ed. 2015 doi: 10.1080/0950069.2015.1085133. Downloaded Oct. 15, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopatto D. Survey of undergraduate research experiences-SURE. First findings. Cell Biology Education. 2004;3:270–77. doi: 10.1187/cbe.04-07-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLachlan AJ. Minority undergraduate programs intended to increase participation in biomedical careers. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2012;79:769–781. doi: 10.1002/msj.21350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]