Abstract

The current study examined predictors of marijuana use among adults, including subsamples of adults who are actively parenting (i.e., have regular face-to-face contact with a child) and those who have no children. Participants were a community sample of 808 adults and two subsamples drawn from the full group: 383 adults who were actively parenting and 135 who had no children. Multilevel models examined predictors of marijuana use in these three groups from ages 27 to 39. Becoming a parent was associated with a decrease in marijuana use. Regular marijuana use in young adulthood (ages 21 – 24), partner marijuana use, and pro-marijuana attitudes increased the likelihood of past-year marijuana use among all participants. Being a primary caregiver (among parents) was associated with less marijuana use. Overall, predictors of marijuana use were largely similar for all adults, regardless of parenting status. Study results suggest that the onset of parenthood alone may be insufficient to reduce adult marijuana use. Instead, preventive intervention targets may include changing adult pro-marijuana attitudes and addressing marijuana use behaviors of live-in partners. Lastly, universal approaches targeting parents and nonparents may be effective for general adult samples.

Keywords: parenting, adult marijuana use, prevention

Introduction

Since 2012, eight states and the District of Columbia have passed legislation to legalize recreational marijuana use for adults age 21 and over. Twenty other states currently allow sales of medical marijuana or have decriminalized marijuana use among adults. Arguments in favor of marijuana legalization often focus on reduction of criminal justice system spending, institutionalized racial/ethnic bias in punishing possession, and potential tax revenue associated with legalized sales and production. The possibility and potential consequences of increased use of marijuana by adults, in particular adults who are actively parenting (i.e., have regular face-to-face contact with a child), have received less attention. Concurrent with recent changes in the legal context, current marijuana use among adults in the United States doubled from 7% to 13% between 2010 and 2013 (McCarthy, 2016). The amount of marijuana used by adults has also increased (Caulkins, Kilmer, Reuter, & Midgette, 2015).

Previous studies have reported robust effects of parental marijuana use on a range of negative child outcomes, including increased risk of child marijuana and other drug use (Bailey et al., 2016; Patrick, Maggs, Greene, Morgan, & Schulenberg, 2014). Thus, the prevention and reduction of marijuana use among adults who are actively parenting are important public health goals that may be complicated by marijuana legalization. The present study uses prospective data from a longitudinal study of adults (including subsamples of those who are actively parenting and those who have no children) to examine patterns and predictors of marijuana use. This study aims to (a) identify malleable prevention targets for adult marijuana use and (b) investigate whether predictors of marijuana use differ for parents.

Patterns and Predictors of Adult Marijuana Use

Substance use, including marijuana, increases steadily throughout adolescence and peaks in young adulthood, after which nationally representative studies of the U.S. population show a general decrease in substance use (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2004). However, national surveys of adults in their late 20s and early 30s show that rates of marijuana use are increasing in the recent years, with between 25% to 30% of all adults currently reporting using marijuana in the past year (Johnston, O'Malley, & Bachman, 2015) and 6.6% in the past month (Center for Behavior Health Statistics and Quality, 2015).

Unlike predictors of adolescent substance use, which have been extensively studied, relatively little is known about patterns of use among adults or about factors that affect adult substance use. Less still is known about adults who are actively parenting, despite this being a group of high importance to public health and prevention researchers. The current study is focused on factors that are relevant to the parenting population and that are likely to be affected by the changing marijuana environment in the context of legalization. Parenting-specific predictors include the transition to parenthood itself, age at first parenthood, and having primary caregiver responsibilities over a child. Factors that may be affected by marijuana legalization are previous marijuana use history, the presence of a marijuana-using partner in the home, and participants’ attitudes toward marijuana use.

National studies have documented that adults who are in committed relationships and who are actively parenting are less likely to use marijuana and other substances (Oesterle, Hawkins, & Hill, 2011; Schulenberg et al., 2005; Staff et al., 2010). In the Monitoring the Future longitudinal panel study, custodial parents were almost 50% less likely to use marijuana (Merline, O'Malley, Schulenberg, Bachman, & Johnston, 2004) and up to 5 times less likely to report an illicit drug disorder than those who were not actively parenting (Fergusson & Boden, 2008). Findings on the effect of timing of entry into parenthood are mixed, however, with some evidence that an earlier transition to parenthood is linked to an earlier decline in substance use (Martin, Blozis, Boeninger, Masarik, & Conger, 2014), and other evidence suggesting that later entry into parenthood is associated with the greatest declines in substance use (Oesterle et al., 2011).

Longitudinal studies of substance use have also shown that patterns of marijuana use prior to entering marriage and parenthood affect the likelihood of using marijuana after the transition. In the Monitoring the Future study, after accounting for parent status, those who reported using marijuana in 12th grade were 8 times more likely to report current use at age 35 (Merline et al., 2004). However, what is less well known is what other factors predict parent marijuana use after their transition to parenthood.

A robust literature on partner concordance suggests that romantic partners play an important role in promoting or hindering their partner’s substance use. This is consistent with several theoretical frameworks that show that availability or opportunity to use substances, along with a normative context within a family, are likely to promote marijuana use (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Jessor, 1991). In general, studies show that adults select romantic partners who have similar levels of substance use, and that having a substance using partner is a barrier to reducing or quitting drug use (Leonard & Homish, 2005; Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007). For example, in a study of over 600 married couples, men whose partners used marijuana prior to the marriage were 3 times as likely to use marijuana in the subsequent 4 years of marriage; for women, the effect was even greater (Homish, Leonard, & Cornelius, 2007). Although living with a romantic partner who uses marijuana can be a risk factor, there is also some indication that adults who are single are more likely to be marijuana users than those who are coupled (Brook, Lee, Brown, Finch, & Brook, 2011; Merline et al., 2004; Merline, Schulenberg, O'Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 2008). One of the gaps in this literature, however, is marijuana use among parents. Thus, it is unclear to what extent partner concordance is in evidence among those adults who are actively parenting.

Finally, there are several theories that identify beliefs and attitudes toward acceptability of marijuana (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) as predictors of use as well as important intervention targets. Perception of marijuana as non-harmful and pro-marijuana norms are associated with greater use in adolescence and young adulthood (Bachman, Johnston, & O'Malley, 1998; Keyes et al., 2011; Palamar, Halkitis, & Kiang, 2013). One nationally representative study showed that, among adolescents (aged 12–17) and young adults (aged 18–25), moderate disapproval of marijuana had a moderate effect on past-year use (ORs = 0.31, 0.27 for adolescents and young adults, respectively) (Salas-Wright, Vaughn, Todic, Córdova, & Perron, 2015). For those who reported strong disapproval, the odds were greatly reduced compared to those who approved of marijuana use (ORs = 0.05, 0.07). However, we are unaware of any studies that specifically examined this relationship in a parenting sample.

The current study extends prior work by examining predictors of adult marijuana use in a community sample of adults (some of whom are parents), and subsets of those actively parenting, and those who have no children. Almost no research exists comparing predictors of marijuana use in these populations. Understanding predictors of marijuana use among parents is important because of the possible intergenerational transmission of marijuana use and the documented negative effects of parent substance use on child behavior and development. Nonparents are examined as a group that often reports higher rates of marijuana use than community or parenting samples (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2006; Merline et al., 2004) and who may be most at risk for developing marijuana addiction. If the parent and nonparent groups share predictors of marijuana use, universal prevention programs may work equally well for all adults without a need for a tailored approach aimed at parents. Accordingly, the current study seeks to identify malleable intervention targets for adults who are and who are not parents by (a) examining the effect that transition to parenthood has on marijuana use, and (b) comparing predictors of marijuana use in three samples: a general sample of adults that includes both parents and nonparents, adults who are actively parenting, and nonparents. Interpretation of analyses focuses on patterns of results among these three groups in order to identify prevention targets for adults in general vs. parents and nonparents.

Methods

Participants

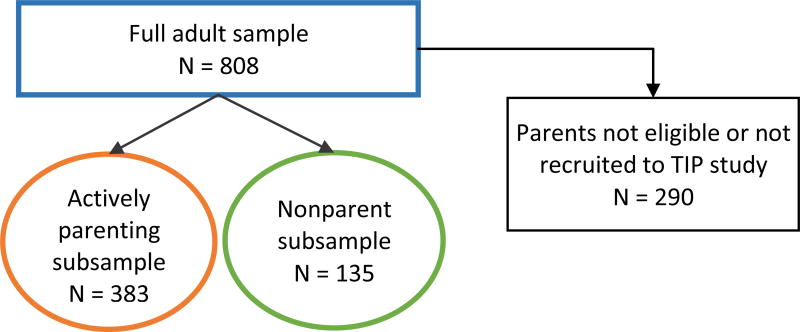

Participants (N = 808) were drawn from two linked longitudinal studies, the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) and the SSDP Intergenerational Project (TIP). Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the main sample into subsamples.

Figure 1.

Sample and subsamples breakdown diagram

The full adult sample is comprised of the SSDP participants (N = 808) who entered the study in 1985 when they were in fifth grade (age 10) in one of 18 participating public schools in Seattle that served high-crime neighborhoods. Approximately half (52%) of all participants met eligibility for the free/reduced-price school lunch program in Grades 5 – 7 (for further study details, see Hawkins et al. (2005)). Follow-up surveys were collected throughout adolescence and into adulthood. The current study is based on adult data collected at ages 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, and 39. The sample is gender balanced (49% female) and ethnically diverse, with 49% of respondents being European American, 25% African American, 21% Asian, and 5% Native American.

Nonparent subsample

By age 39, 135 SSDP participants reported never having children and are referred to as “nonparents.” The nonparent subsample was 43% female, 58% European American, 18% African American, 22% Asian, and 2% Native American. Around a third (37%) had met eligibility for free/reduced-price school lunch program.

Actively parenting subsample

Beginning in 2001, SSDP participants who were actively parenting were recruited into the SSDP-Intergenerational Project (TIP) along with the oldest biological child with whom they had regular face-to-face contact. A total of 383 families that included the SSDP participant, their child and (where appropriate) a second caregiver were recruited into the study (Bailey, Hill, Oesterle, & Hawkins, 2006). Since 2002, TIP uses an accelerated longitudinal design with rolling enrollment as new SSDP participants became parents for the first time. A total of 7 waves of data have been collected for the active parent subsample by 2011.

About 60% of the active parent subsample were female. The subsample was racially/ethnically diverse with 41% identifying as European American, 22% African American, and 16% multiethnic, with the remainder being primarily Asian American/ Pacific Islander or Native American; 7% of parents were Hispanic. Compared to the full adult sample, those SSDP participants eligible for TIP were more likely to be female and married than fathers and unmarried. Of those eligible, families were slightly less likely to be recruited if the SSDP parent was Asian American or was eligible for free lunch in Grades 5 – 7.

During elementary and middle school, SSDP participants were enrolled in an intervention trial (Hawkins, Guo, Hill, Battin-Pearson, & Abbott, 2001). Intervention condition has not been related to marijuana use at any age, whether participants became parents, TIP recruitment, or study retention. SSDP and TIP materials and protocols were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. Retention across waves in both studies has been very high, with 88% or greater in SSDP and 90% in TIP.

Measures

Current marijuana use in the past year was measured prospectively via self-report at ages 27 – 39 in both studies and coded as use (1) versus no use (0). Young adult marijuana use measured whether the participant ever used marijuana frequently during young adulthood (Schulenberg et al., 2005), and was coded as 1 if participants reported using 10 or more times in the past year at age 21 or 24 (0 otherwise).

Partner marijuana use was measured prospectively at ages 27 – 39 and coded as yes (1) or no (0) for all participants who had a live-in romantic partner or spouse. In SSDP, participants reported on their partner’s marijuana use. In the TIP study, partners/spouses reported on their own use. A reference category Single was created for participants, coded as 1 for those who did not have a romantic partner or did not cohabit with the partner (0 otherwise).

Attitudes toward marijuana was measured prospectively in each study at each wave (ages 27 – 39). Participants reported whether they thought it was ok for adults to smoke marijuana (1 = NO!, 2 = no, 3 = yes, 4 = YES!). Because the distribution was skewed, variables were dichotomized as 1 = yes/YES! and 0 = no/NO! to reflect pro-marijuana attitudes.

Transition to parenthood

In the SSDP study, transition to parenthood was a time-varying covariate coded as 0 in all the waves before a participant became a parent and 1 thereafter. This measure allowed us to test whether the transition to parenthood has an impact on participants’ marijuana use.

Primary caregiver

In TIP, participants indicated whether they were the primary caregiver for their child. This question was asked at each wave and is included as a time-varying predictor.

Interactions with time

In both sets of analyses, we centered the time variable and each of the time-varying predictors. In TIP, time was centered at age 34 (Wave 5). In SSDP, time was centered at age 33. Multiplicative interactions with time were tested.

Control variables

All analyses were adjusted for parent gender, ethnicity, and years of education.

Analyses

Multilevel modeling in HLM (version 7.01) was used to account for repeated measures nested within person (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & du Toit, 2011). HLM allows examination of between-person differences in within-person change over time and inclusion of non-normally distributed dependent variables, and models dependencies inherent in repeated measures. We used the Bernoulli link function, given that marijuana use was measured dichotomously. Analyses were done separately with the full SSDP sample, and with the nonparent and actively parenting subsamples. Data for marijuana use in the full adult sample and nonparent subsample were collected at ages 27, 30, 33, and 39; most participants had data at all waves and data were missing at random. HLM allows missing data in level 1 (repeated measures) data and uses empirical Bayes estimation to handle missing data in time-varying variables (Little & Rubin, 2002; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). For the actively parenting subsample, we used data collected as part of the TIP study at ages 27, 28, 29, 30, 34, 35, and 36 (Waves 1 – 7). Each parent in the TIP study was interviewed between 1–7 times. Missing waves were treated as missing level 1data and again handled by empirical Bayes estimation. Later recruitment was related to the time when parents had their first biological child; thus, we control for the age of parent at child birth.

For each study, we tested linear and quadratic time terms. Demographic factors (parent gender, ethnicity, and education) and marijuana use in young adulthood were modeled as fixed effects. Finally, we tested time interactions for each time-varying predictor to examine whether predictors of marijuana use change as participants (and their children) get older.

Results

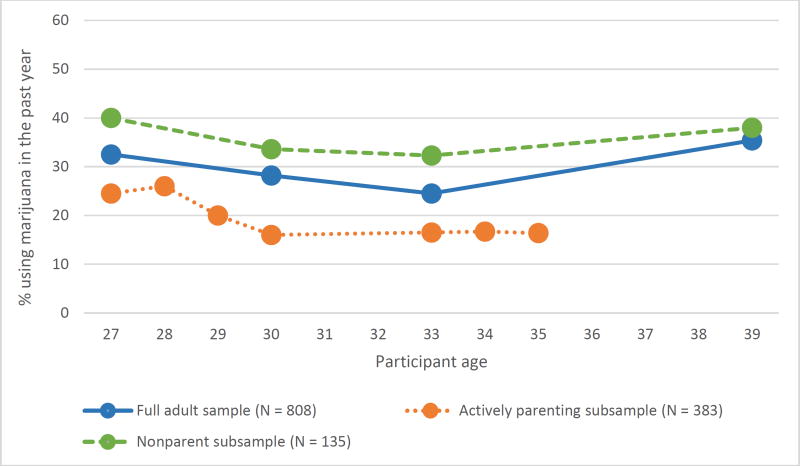

Patterns of marijuana use among adults, parents, and nonparents are shown in Figure 2. Consistent with the literature, marijuana use among the full adult sample fell in the middle between the nonparent subsample (who reported higher rates of use) and the actively parenting subsample (who reported lower rates). All groups show a general downward trend between the ages of 27 and 33, after which the actively parenting subsample continued in a flat trajectory through age 36, whereas rates among the full adult sample and nonparent subsample increase through age 39. The prevalence of frequent marijuana use in young adulthood was similar for the full sample (29.3%), those actively parenting (27.7%), and nonparents (34.3%).

Figure 2.

Rates of past-year marijuana use among adults, parents, and nonparents

To answer the first research question about the effect that the transition to parenthood has on marijuana use, we tested HLM models of the relationship between parenthood and marijuana use in the full adult sample (Table 1). Level 1 (time-varying) variables included time, time squared, transition to parenthood, and transition to parenthood × time. Level 2 (time-fixed) variables included parent gender, ethnicity, and education which were regressed on the intercept and the linear time variable. After accounting for control variables, becoming a parent reduced the odds of marijuana use by 41% (OR = 0.59; 95% CI = 0.42, 0.84; p = .003) in the full adult sample. The interaction between parenthood and time was not significant suggesting not difference in reduction of marijuana use by timing of parenthood.

Table 1.

Effect of Transition to Parenthood on Marijuana Use in the full adult sample

| Predictor | Full adult sample (N = 808) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| OR (95% CI)

|

|

| Intercept | 0.52 (0.30, 0.90)* |

| Parent male | 1.99 (1.41, 2.81)*** |

| Parent Black | 1.10 (0.72, 1.66) |

| Parent Asian | 0.30 (0.18, 0.49)*** |

| Parent Native | 1.14 (0.54, 2.39) |

| Parent education | 0.72 (0.62, 0.85)*** |

| Time | 1.83 (0.71, 4.74) |

| Parent male | 0.76 (0.42, 1.38) |

| Parent Black | 0.65 (0.32, 1.32) |

| Parent Asian | 1.07 (0.46, 2.54) |

| Parent Native | 0.51 (0.15, 1.77) |

| Parent education | 0.83 (0.63, 1.09) |

| Time2 | 9.56 (3.65, 25.03)*** |

|

| |

| Time-varying predictors | |

| Age at parenthood | 0.59 (0.42, 0.83)** |

| Age at parenthood × time | 1.38 (0.67, 2.82) |

Note.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

The second research question asked whether the pattern of predictors of marijuana use among adults overall differed from adults who are actively parenting or nonparents. Building on the model in Table 1, we added partner marijuana use, being unpartnered/single, attitudes toward marijuana, and being the primary caregiver (for the actively parenting subsample) at Level 1 (see Table 2). Interactions between time and time-varying predictors also were included at Level 1. Young adult marijuana use was entered at Level 2. Results show that young adult marijuana use had a strong effect on the intercept of each of the three groups, increasing the likelihood of later marijuana use by 7 times in the full adult sample, 9.9 times in the nonparent subsample, and almost 20 times in the actively parenting subsample. Previous marijuana use was also negatively related to linear change over time in the full sample and among nonparents. Because of its strong positive effect on the intercept, the negative effect of young adult marijuana use on slope suggests a ceiling effect for previously regular users, who already used at much higher rates.

Multilevel Models in SSDP and TIP: Predictors of Marijuana Use

| Predictor | Full adult sample (N = 808) |

Actively parenting subsample (N = 383) |

Nonparent subsample (N = 135) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| TIME-FIXED (Level 2) | OR (95% CI)

|

||

| Intercept | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06)*** | 0.03 (0.01, 0.10)*** | 0.02 (0.01, 0.12)*** |

| Parent male | 1.21 (0.86, 1.69) | 0.67 (0.27, 1.66) | 0.74 (0.32, 1.72) |

| Parent Black | 1.06 (0.72, 1.56) | 1.70 (0.72, 4.01) | 0.25 (0.09, 0.71)* |

| Parent Asian | 0.64 (0.40, 1.03)+ | 2.25 (0.83, 6.11)+ | 0.70 (0.25, 2.00) |

| Parent Native | 0.88 (0.44, 1.77) | 1.21 (0.33, 4.48) | 0.58 (0.03, 13.24) |

| Parent education | 0.85 (0.73, 0.99)* | 0.76 (0.56, 1.02)+ | 0.87 (0.59, 1.29) |

| Young adult mj. use (21–24) | 6.98 (4.97, 9.81)*** | 19.84 (9.63, 40.89)*** | 9.85 (4.10, 23.70)*** |

| Time intercept | 2.18 (0.68, 7.06) | 1.16 (0.86, 1.56) | 0.75 (0.03, 19.81) |

| Parent male | 0.57 (0.28, 1.17) | 0.90 (0.76, 1.08) | 4.22 (0.83, 21.54)+ |

| Parent Black | 0.69 (0.31, 1.55) | 1.06 (0.91, 1.24) | 4.38 (0.54, 35.34) |

| Parent Asian | 0.89 (0.33, 2.41) | 1.26 (1.01, 1.58)* | 2.20 (0.28, 17.38) |

| Parent Native | 0.67 (0.15, 2.90) | 1.07(0.85, 1.35) | † |

| Parent education | 0.73 (0.53, 1.00)* | 0.98 (0.92, 1.04) | 0.71 (0.34, 1.51) |

| Young adult mj. use (21–24) | 0.53 (0.26, 1.09)+ | 0.92 (0.81, 1.04) | 0.09 (0.02, 0.49)** |

| Time intercept2 | 3.78 (1.23, 11.63)* | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07)+ | 4.03 (0.27, 60.47) |

|

| |||

| TIME-VARYING (Level 1) | |||

| Partner marijuana use | 7.20 (4.42, 11.73)*** | 2.86 (1.09, 7.52)* | 51.64 (7.91, 337.06)*** |

| Single | 1.77 (1.30, 2.42)*** | 1.94 (0.87, 4.30) | 3.99 (1.74, 9.17)** |

| Pro-marijuana attitudes | 8.36 (6.01, 11.63)*** | 9.47 (5.13, 17.49)*** | 10.78 (4.74, 24.52)*** |

| Primary caregiver | - | 0.47 (0.21, 1.06)+ | -- |

| Partner mj. use × time | 0.77 (0.23, 2.55) | 0.95 (0.76, 1.19) | 0.02 (0.00, 1.09)+ |

| Single × time | 1.11 (0.52, 2.41) | 1.16 (0.96, 1.39) | 2.16 (0.29, 16.18) |

| Pro-mj. attitudes × time | 1.78 (0.77, 4.09) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.15) | 0.97(0.13, 7.39) |

| Primary caregiver × time | - | 0.94 (0.78, 1.12) | -- |

Note.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001;

mj. = marijuana.

uninterpretable due to a low number of Native Americans

Reference group for ethnicity is White.

In terms of time-varying predictors, Table 2 shows that having a partner who used marijuana increased the likelihood of marijuana use by more than 7 times in for the full adult sample and 2.9 times in the active parenting sample compared to those who had a non-using partner. Among nonparents, there was more than a 50-fold increase in risk. In the full adult and nonparent groups, being single also increased the likelihood of marijuana use compared to those who were partnered with nonusers. Being single was not related to the rate of active parents’ use, however. Adults’ own pro-marijuana attitudes were also a risk factor, increasing the odds of marijuana use by 8 to 11 times in the three groups. None of the interactions between time-varying predictors and time were significant.

Demographic variables were not consistently related to marijuana use in any of the three groups examined in Table 2. Higher education predicted lower likelihood of marijuana use in the full sample and (marginally) among active parents. Being Black (compared to White) was related to less marijuana use in the nonparent subsample. Being Asian was positively associated with slope among active parents, suggesting that Asian parents were more likely than Whites to increase marijuana use over time.

Discussion

Marijuana use among adults has increased in the past few years, most likely in response to Washington State and national trends in decriminalization and legalization of recreational marijuana and to a general move toward pro-marijuana norms across the nation (Hasin et al., 2015; Salas-Wright et al., 2015; Schmidt, Jacobs, & Spetz, 2016). The current study sought to understand predictors of marijuana use and identify malleable intervention targets for adults who are and who are not parents. Results suggest that the predictors of marijuana use in in a community sample of adults, a subsample of those who were never parents by their late 30s, and a subsample of adults who are actively parenting were generally similar, although the magnitude of effects and some of the time interactions differed by group.

The pattern of marijuana use over time in the full adult sample is consistent both with prior literature showing a gradual decline in marijuana use prevalence across the late 20s and 30s, as well as with recent findings showing an uptick in the prevalence of use among adults in recent years (Hasin et al., 2015). Prior to legalization, participants in the SSDP study reported a gradual decrease in use through age 33 (in 2008), but a rise between age 33 and age 39 (in 2014). Recreational marijuana use was legalized in Washington State in December 2012; however, since there was no data collection for six years in the SSDP study, it is unclear when the increase between 33 and 39 began. The nonparent sample followed the same pattern. Post-legalization data from actively parenting subsample who are part of the TIP study are currently being collected. In future work, we will test whether the prevalence of marijuana use among adults who are actively parenting also increased following legalization.

The transition to parenthood marked a significant decrease in marijuana use in the general adult sample. When this sample was compared to active parents and nonparents, there were three notable differences in predictors of marijuana use between these groups. First, young adult marijuana use had a much larger effect on active parents’ current use than that of the general adult sample or of nonparents. Although there was little difference between parents and nonparents in levels of frequent marijuana use in young adulthood (ages 21–24), by age 27 active parents reported lower rates of use, suggesting that in the transition to parenthood between ages 24 and 27, more of those who were actively parenting quit using marijuana. It is possible that those who continued using after they became parents were heavier users in their early 20s compared to same-aged nonparents. Second, it appears that for adults who are actively parenting, romantic partners had less influence than for other adults; on the other hand partner marijuana use played the strongest role among nonparents. It is unclear why adults who are parenting might be less influenced by partner use than adults in general or nonparents. Relatedly, being single in the actively parenting group did not predict marijuana use, whereas being single was associated with greater marijuana use risk in full adult and nonparent groups. It seems probable that those adults who are single and not parenting use substances at higher rates than parents and may choose partners who reinforce this behavior (Merline et al., 2004; Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007). At the same time, single parents may have more childcare responsibilities that may keep them from using marijuana.

Limitations of the current work include a geographically limited sample with a relatively small number of adults who never had children. The study is also limited in the number of marijuana-related predictors available in both SSDP and TIP datasets. Other studies should consider testing predictors in the peer and work domains, such as having friends who use marijuana or working in a profession that restricts drug use. Further, more research is needed to examine whether the predictors of adult marijuana use reported in the current study continue to predict adults’ use in a context of legalization of recreational use of marijuana. Finally, we caution the readers that despite the longitudinal nature of the data, we cannot establish causal order between time-varying predictors and the outcome. Despite these limitations, this study has a number of strengths. First, it contributes to knowledge regarding patterns and predictors of adult marijuana use, which is timely and important for prevention efforts. The study also includes a longitudinal design with multiple time points. The comparison between parents and nonparents tests an important research question about the need for separate prevention efforts for different groups of adults. Because parent marijuana use has been associated with a wide range of negative child outcomes, including behavior problems and child marijuana and other drug use (Fergusson & Boden, 2008; Meier et al., 2012; Volkow, Baler, Compton, & Weiss, 2014), preventing and reducing marijuana use by adults who are actively parenting should be a priority for public health efforts.

The implications of this work are threefold. First, since young adult marijuana use was a strong predictor of continued use during parenthood, public health approaches cannot rely solely on adults self-withdrawing from marijuana use once they have children. Therefore, it is important to address marijuana use with young adults. Second, public health approaches for reducing adult marijuana use need to include live-in partners who may be using marijuana. Prevention will be most successful if both partners’ marijuana use is addressed concurrently (Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007). Third, marijuana legalization has been linked to more acceptance of marijuana (Schuermeyer et al., 2014), and attitudes toward marijuana use were found to play an important role in predicting use in the current work. Changing those attitudes through campaigns similar to those employed for cigarette smoking is an important intervention framework to consider. For example, Kilmer et al. (2007) suggest that some useful approaches could target the discrepancy between adults’ pro-marijuana attitudes and their own or observed experiences of health consequences from using the drug.

Although research on whether moderate marijuana use by adults is likely to lead to adverse consequences is mixed, marijuana use among parents carries a significant risk of their children initiating marijuana use during the teenage years (Bailey et al., 2016; Miller, Siegel, Hohman, & Crano, 2013). Given that, the current study highlights malleable factors and prevention targets that are likely to be most useful and cost-effective for prevention of marijuana use among parents. However, the same targets are also likely to be effective for adults more generally if (moderate) adult use were to be found harmful in the future.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA023089). The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency.

Footnotes

Compliance With Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Human Subjects division of the Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All measures and procedures were approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM. Explaining recent increases in students' marijuana use: Impacts of perceived risks and disapproval, 1976 through 1996. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(6):887–892. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Hill KG, Guttmannova K, Epstein M, Abbott RD, Steeger CM, Skinner ML. Associations between parental and grandparental marijuana use and child substance use norms in a prospective, three-generation study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;59(3):262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Hill KG, Oesterle S, Hawkins JD. Linking substance use and problem behavior across three generations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(3):273–292. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Lee JY, Brown EN, Finch SJ, Brook DW. Developmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: Personality and social role outcomes. Psychological Reports. 2011;108(2):339–357. doi: 10.2466/10.18.PR0.108.2.339-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins JP, Kilmer B, Reuter PH, Midgette G. Cocaine's fall and marijuana's rise: Questions and insights based on new estimates of consumption and expenditures in US drug markets. Addiction. 2015;110(5):728–736. doi: 10.1111/add.12628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavior Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Maturing out of alcohol dependence: the impact of transitional life events. Journal of studies on alcohol. 2006;67(2):195–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM. Cannabis use and later life outcomes. Addiction. 2008;103(6):969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Zhang H, Grant BF. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1235–1242. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Guo J, Hill KG, Battin-Pearson S, Abbott RD. Long-term effects of the Seattle Social Development intervention on school bonding trajectories. Applied Developmental Science. 2001;5(4):225–236. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0504_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Promoting positive adult functioning through social development intervention in childhood: Long-term effects from the Seattle Social Development Project. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(1):25–31. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR. Predictors of marijuana use among married couples: The influence of one's spouse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91(2–3):121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12(8):597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2014: Volume 2: College students and adults ages 19–55. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2003. Volume I: Secondary school students. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2004. (NIH Publication No. 04-5507) [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Schulenberg JE, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG, Li G, Hasin D. The social norms of birth cohorts and adolescent marijuana use in the United States, 1976–2007. Addiction. 2011;106(10):1790–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer JR, Hunt SB, Lee CM, Neighbors C. Marijuana use, risk perception, and consequences: Is perceived risk congruent with reality? Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):3026–3033. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Homish GG. Changes in marijuana use over the transition into marriage. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):409–430. doi: 10.1177/002204260503500209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martin MJ, Blozis SA, Boeninger DK, Masarik AS, Conger RD. The timing of entry into adult roles and changes in trajectories of problem behaviors during the transition to adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(11):2473–2484. doi: 10.1037/a0037950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J. One in eight U.S. adults say they smoke marijuana. (Well-being series) Well-being. 2016 Aug 8; from http://www.gallup.com/poll/194195/adults-say-smoke-marijuana.aspx.

- Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, Harrington H, Houts R, Keefe RSE, Moffitt TE. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. PNAS Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(40):E2657–E2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline AC, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Substance use among adults 35 years of age: Prevalence, adulthood predictors, and impact of adolescent substance use. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(1):96–102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline AC, Schulenberg JE, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Substance use in marital dyads: Premarital assortment and change over time. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(3):352–361. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SM, Siegel JT, Hohman Z, Crano WD. Factors mediating the association of the recency of parent’s marijuana use and their adolescent children’s subsequent initiation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(3):848–853. doi: 10.1037/a0032201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle S, Hawkins JD, Hill KG. Men's and women's pathways to adulthood and associated substance misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(5):763–773. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Halkitis PN, Kiang MV. Perceived public stigma and stigmatization in explaining lifetime illicit drug use among emerging adults. Addiction Research & Theory. 2013;21(6):516–525. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Maggs JL, Greene KM, Morgan NR, Schulenberg JE. The link between mother and adolescent substance use: Intergenerational findings from the British Cohort Study. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies. 2014;5(1):56–63. doi: 10.14301/llcs.v5i1.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon RT, Jr, du Toit M. HLM 7.1: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rhule-Louie DM, McMahon RJ. Problem behavior and romantic relationships: Assortative mating, behavior contagion, and desistance. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10(1):53–100. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Todic J, Córdova D, Perron BE. Trends in the disapproval and use of marijuana among adolescents and young adults in the United States: 2002–2013. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2015;41(5):392–404. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1049493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LA, Jacobs LM, Spetz J. Young people’s more permissive views about marijuana: Local impact of state laws or national trend? American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106(8):1498–1503. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuermeyer J, Salomonsen-Sautel S, Price RK, Balan S, Thurstone C, Min S-J, Sakai JT. Temporal trends in marijuana attitudes, availability and use in Colorado compared to non-medical marijuana states: 2003–11. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;140:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.016. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Merline AC, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Laetz VB. Trajectories of marijuana use during the transition to adulthood: The big picture based on national panel data. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):255–280. doi: 10.1177/002204260503500203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Maggs JL, Johnston LD. Substance use changes and social role transitions: Proximal developmental effects on ongoing trajectories from late adolescence through early adulthood. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(4):917–932. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SRB. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(23):2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]