Abstract

Purpose

Evaluating the risk of lymph node metastasis (LNM) is critical for determining subsequent treatments following endoscopic resection of T1 colorectal cancer (CRC). This study analyzed histopathologic risk factors for LNM in patients with T1 CRC.

Methods

This study involved 745 patients with T1 CRC who underwent endoscopic (n = 97) or surgical (n = 648) resection between January 2001 and December 2015 at the National Cancer Center, Korea. LNM in endoscopically resected patients, which could not be evaluated directly, was estimated indirectly based on follow-up results and histopathologic reports of salvage surgery. The relationships of depth of submucosal invasion, histologic grade, budding, vascular invasion, and background adenoma with LNM were evaluated statistically.

Results

Of the 745 patients, 91 (12.2%) were found to be positive for LNM. Univariate and multivariate analyses identified deep submucosal invasion (P = 0.010), histologic high grade (P < 0.001), budding (P = 0.034), and vascular invasion (P < 0.001) as risk factors for LNM. Among the patients with one, two, three, and four risk factors, 6.0%, 18.7%, 36.4%, and 100%, respectively, were positive for LNM.

Conclusion

Deep submucosal invasion, histologic high grade, budding, and vascular invasion are risk factors for LNM in patients with T1 colorectal cancer. If any of these risk factors are present, additional surgery following endoscopic resection should be determined after considering the potential risk of LNM and each patient's situation.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasm, Colonoscopy, Lymphatic metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Recently, with the increasing implementation of endoscopic screening programs for colorectal cancer (CRC), the incidence of early CRC has been increasing [1]. Although intraepithelial or intramucosal (Tis) CRC carries no risk of lymph node metastasis (LNM) [2,3], LNM has been observed in 7%–15% of patients with T1 CRC, defined as tumors invading the submucosa [4,5,6,7]. Endoscopic resection of Tis CRC is therefore considered standard therapy, whereas endoscopic resection of T1 CRC is limited to selected patients.

Thus, evaluation of the risk of LNM in the latter patients after endoscopic resection is critical for determining whether these patients should undergo additional surgery or be monitored regularly.

According to the current guidelines, additional surgery is preferable when the resection margin is positive or any of risk factors for LNM are present. The risk factors for LNM include deep submucosal invasion, histologic high grade, budding, and vascular invasion [7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Our previous study, involving 435 patients with T1 CRC treated in 2001–2010, found that histologic high grade, budding, vascular invasion, and the absence of background adenoma were associated with LNM in patients with T1 CRC [14].

This study updates our previous findings, assessing the factors associated with LNM in patients with T1 CRC treated in 2001–2015.

METHODS

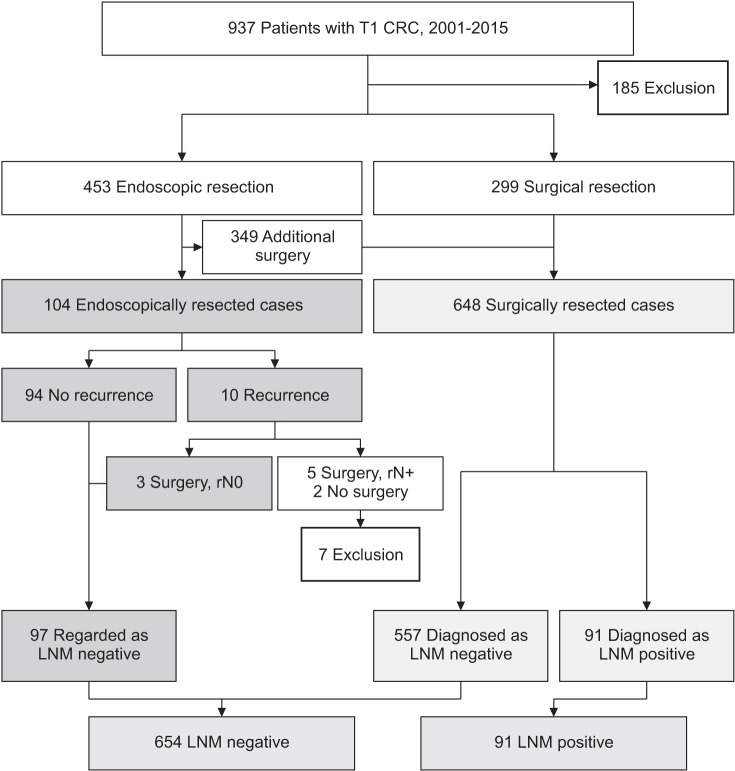

Between January 2001 and December 2015, 937 patients with T1 CRC underwent endoscopic or surgical resection at the National Cancer Center, Korea, excluding those with ypT1 pathology who received preoperative chemoradiation treatment. Among these 937 patients, those with familial adenomatous polyposis (n = 16) or synchronous advanced CRC (n = 75) were excluded, as were patients endoscopically resected but followed up for <24 months (n = 94). Of the endoscopically resected patients, patients with recurrence who were found to be positive for LNM on salvage surgery (rpN1 or 2) (n = 5) and those with multiple metastases who did not undergo salvage surgery (n = 2) were excluded because of the uncertainty in timing of LNM and the possibility of skip metastases, respectively. Thus, this study included 745 patients, 97 who underwent endoscopic resection and 648 who underwent surgical resection (Fig. 1). The database of the National Cancer Center and patients' clinical charts were reviewed retrospectively.

Fig. 1. Pathway for estimating the status of lymph node metastasis (LNM) in endoscopically resected patients. CRC, colorectal cancer.

Based on the Paris classification, endoscopically resected tumors were classified into 4 types: pedunculated, sessile, flat, and depressed [15].

Tumor location was classified into 3 groups: right colon (defined as cecum – splenic flexure), left colon (defined as splenic flexure – rectosigmoid junction), and rectum (defined as rectosigmoid junction – anal verge).

The depth of submucosal invasion was evaluated using Kudo's classification as infiltration into the upper third (sm1), middle third (sm2), or lower third (sm3) of the submucosal layer in surgically resected specimens [16]. For endoscopically resected sessile and flat tumors, the cut-off between sm1 and sm2 was 1,000 µm according to the Paris classification, with submucosal invasion >2,000 µm defined as sm3 [15]. For endoscopically resected pedunculated tumors, the cut-off between sm1 and sm2 was at the level of the neck [2], and submucosal invasion >3,000 µm from the neck was defined as sm3. Submucosal invasion depth ≥sm2 was defined as deep submucosal invasion.

Differentiation of adenocarcinomas was classified according to World Health Organization criteria: grade 1 (well differentiated), grade 2 (moderately differentiated), or grade 3 (poorly differentiated) [17]. Grades 1 and 2 were defined as histologic low grade, and grade 3, mucinous carcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, and carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation were defined as histologic high grade.

An isolated cell or a small cluster of <5 tumor cells in the invasive front was defined as a “budding” focus, and >10 budding foci viewed at ×200 magnification was defined as budding positive [18].

Vascular invasion was defined as the presence of cancer cells within endothelial-lined channels, including angiolymphatic invasion and venous invasion. Vascular invasion of small vessels without a vascular smooth muscle layer was defined as angiolymphatic invasion, and vascular invasion of large vessels with a vascular smooth muscle layer was defined as venous invasion.

Background, or preexisting, adenoma was defined as benign adenomatous tissue contiguous to a resected carcinoma.

Estimation of the status of LNM in endoscopically resected patients

The 97 endoscopically resected patients were followed up by colonoscopy, performed 3–6 months after resection and annually thereafter, and by annual CT scan of the abdomen and chest and annual measurement of serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) concentration. LNM status in these patients was determined indirectly, based on follow-up results and/or histopathologic reports of salvage surgery.

Patients were followed up for a minimum of 24 months. Patients with no evidence of recurrence during follow-up and those with recurrence who had no evidence of LNM on salvage surgery (rpN0) were regarded as negative for LNM.

Statistical analyses

The relationship between histopathologic factors and LNM was evaluated using the chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the risk factors associated with LNM. A P-value < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center, Korea (NCC2017-0189), and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients

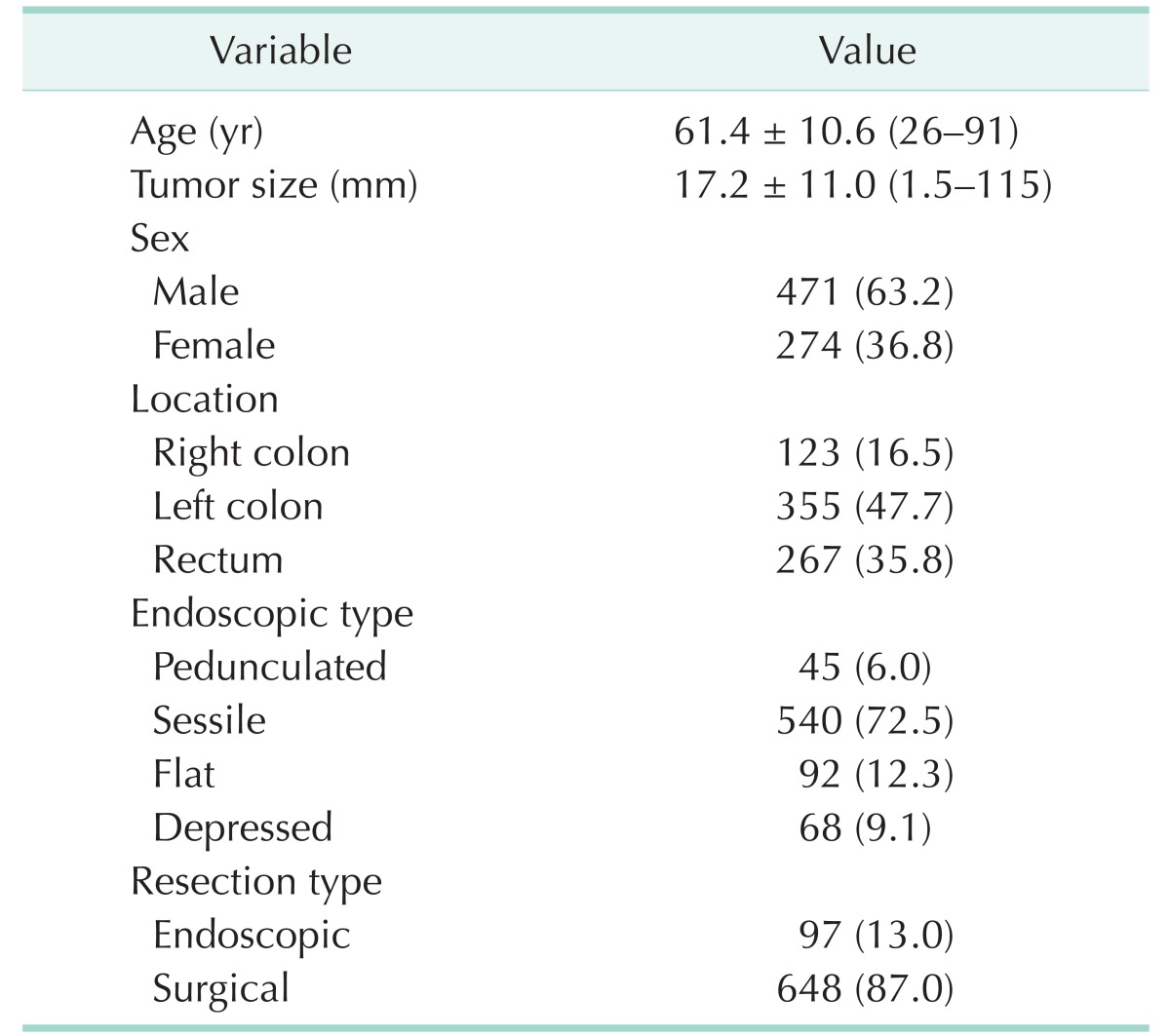

The 745 patients enrolled in this study included 471 men (63.2%) and 274 women (36.8%), of mean age 61.4 years (range, 26–91 years). Of these 745 patients, 123 (16.5%) had right colon tumors, 355 (47.7%) had left colon tumors, and 267 (35.8%) had rectal tumors. Tumors were pedunculated in 45 patients (6.0%), sessile in 540 (72.5%), flat in 92 (12.4%), and depressed in 68 (9.1%). Of these 745 patients, 97 (13.0%) underwent only endoscopic resection and 648 (87.0%) underwent surgical resection. Mean tumor size was 17.2 ± 11.0 mm (range, 1.5–115 mm) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of study patients (n = 745).

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (range) or number (%).

Follow-up results and estimation of LNM status of endoscopically resected patients

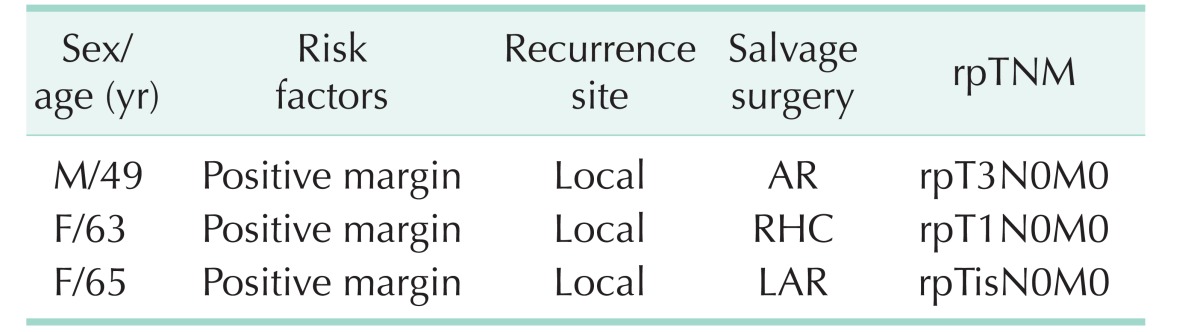

The mean follow-up period was 59.5 months (range, 24–142 months). Of the 97 endoscopically resected patients, 94 (96.9%) showed no evidence of recurrence during the follow-up period, and they were regarded as negative for LNM. The remaining 3 patients (3.1%) with recurrence were negative for LNM (rpN0) on salvage surgery. Details of 3 patients with recurrence are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Details of 3 patients with recurrence after endoscopic resection.

AR, anterior resection; RHC, right hemicolectomy; LAR, low anterior resection.

Relationship between histopathologic factors and LNM

Of the 745 patients, 91 (12.2%) were found to be LNM positive. Both univariate (Table 3) and multivariate (Table 4) analyses indicated that histologic high grade (P < 0.001), vascular invasion (P < 0.001), deep submucosal invasion (P = 0.010), and budding (P = 0.034) were significantly associated with LNM.

Table 3. Relationships between histopathologic factors and lymph node metastasis (LNM).

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of histopathologic factors associated with lymph node metastasis.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

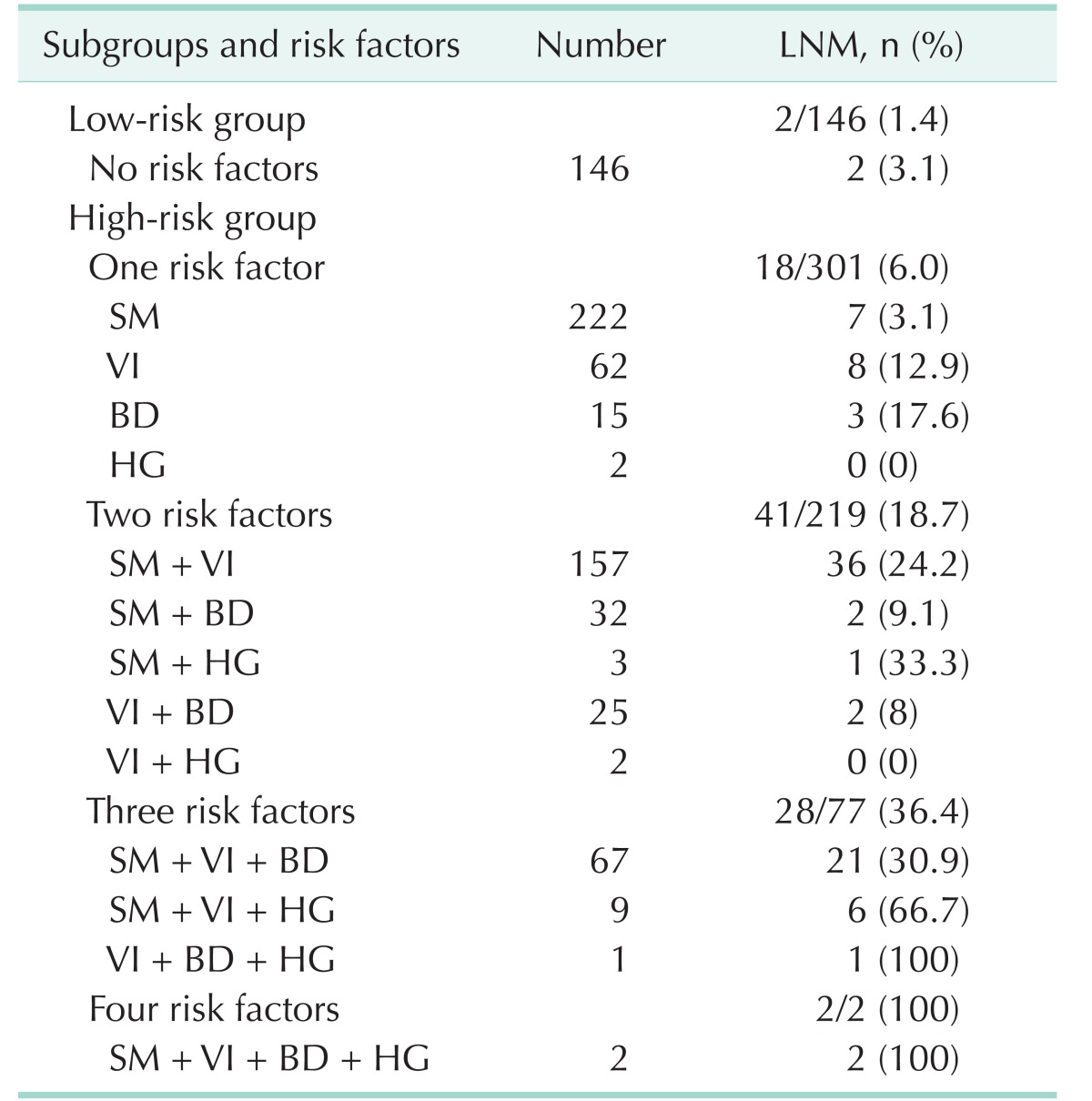

Incidence of LNM in patients subgrouped by number of risk factors

Four risk factors for LNM were identified in patients with T1 CRC: deep submucosal invasion, histologic high grade, budding, and vascular invasion. The relationship between the number of risk factors and LNM was analyzed (Table 5).

Table 5. Relationship between lymph node metastasis (LNM) and number of risk factors.

SM, deep submucosal invasion; VI, vascular invasion; BD, budding; HG, histologic high grade.

Among the patients with one, two, three, and four risk factors, 6.0%, 18.7%, 36.4%, and 100%, respectively, were positive for LNM.

DISCUSSION

The current guidelines recommend additional surgery for patients at high risk of LNM. In agreement with the current guidelines, this study identified deep submucosal invasion, histologic high grade, budding, and vascular invasion as risk factors predicting LNM in patients with T1 CRC.

Our previous study excluded patients who underwent endoscopic resection from the statistical analyses [14], because their LNM status could not be evaluated directly. Because most T1 CRCs without risk factors undergo endoscopic resection, exclusion of endoscopically resected patients may cause a selection bias, affecting the study results. Therefore, in the current study, LNM status of endoscopically resected patients was estimated indirectly based on follow-up results and/or histopathologic reports of salvage surgery, with these patients included in statistical analyses to overcome any possible selection bias.

Consistent with previous findings, the current study showed that deep submucosal invasion was significantly associated with LNM. Several other studies, however, have evaluated the area, not the depth, of submucosal invasion [19]. According to one of those studies, lymphatic vessels were reported to be significantly more numerous within sm1 than within sm3, suggesting that tumors invading sm1 alone, but on a broader front, may be able to gain greater access to the lymphatic system than narrow but deeply invading sm3 tumors [20].

The current study also found that histologic high grade and vascular invasion were the most relevant risk factors for LNM in patients with T1 CRC, in good agreement with many earlier studies.

Budding is a histologic feature thought to correspond to the initial phase of tumor invasion and reported to be associated with metastatic activity [21]. Japanese guidelines accept budding as a risk factor for LNM in T1 CRC, but not western guidelines. The current study showed that budding was significantly associated with LNM in T1 CRC.

Most CRCs develop from adenomatous polyps through the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, although some of these tumors develop de novo [22,23]. Although the relationship between the absence of background adenoma and LNM in T1 CRC has not been clearly determined, the absence of background adenoma may indicate more aggressive biologic behavior. In contrast to our previous study, which showed that the absence of background adenoma was significantly associated with LNM on both univariate and multivariate analyses, the current study found that the absence of background adenoma was significant on univariate analysis alone.

The current study showed that the incidence of LNM ranges widely according to the kind and number of risk factors in T1 CRC (6.0%–100%) (Table 5). Therefore, when determining subsequent treatments, the potential risk of LNM should be considered, instead of dichotomous decisions depending on the presence or absence of risk factors.

This study had several limitations. Most importantly, LNM status in endoscopically resected patients was estimated indirectly, but these patients were included in statistical analyses. However, this may help overcome a possible selection bias, as described above. Other limitations included the retrospective design of the study and its relatively short follow-up period.

In conclusion, this study showed that deep submucosal invasion, histologic high grade, budding, and vascular invasion are independent risk factors for LNM in patients with T1 CRC, and the incidence of LNM ranges widely according to the type and number of risk factors. If any of these risk factors are present, additional surgery following endoscopic resection should be determined after considering the potential risk of LNM and each patient's situation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a National Cancer Center Grant, Korea (NCC-1510150).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Gupta AK, Melton LJ, 3rd, Petersen GM, Timmons LJ, Vege SS, Harmsen WS, et al. Changing trends in the incidence, stage, survival, and screen-detection of colorectal cancer: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:150–158. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haggitt RC, Glotzbach RE, Soffer EE, Wruble LD. Prognostic factors in colorectal carcinomas arising in adenomas: implications for lesions removed by endoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:328–336. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyzer S, Begin LR, Gordon PH, Mitmaker B. The care of patients with colorectal polyps that contain invasive adenocarcinoma. Endoscopic polypectomy or colectomy. Cancer. 1992;70:2044–2050. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921015)70:8<2044::aid-cncr2820700805>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kikuchi R, Takano M, Takagi K, Fujimoto N, Nozaki R, Fujiyoshi T, et al. Management of early invasive colorectal cancer. Risk of recurrence and clinical guidelines. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:1286–1295. doi: 10.1007/BF02049154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nascimbeni R, Burgart LJ, Nivatvongs S, Larson DR. Risk of lymph node metastasis in T1 carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:200–206. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitajima K, Fujimori T, Fujii S, Takeda J, Ohkura Y, Kawamata H, et al. Correlations between lymph node metastasis and depth of submucosal invasion in submucosal invasive colorectal carcinoma: a Japanese collaborative study. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:534–543. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sohn DK, Chang HJ, Park JW, Choi DH, Han KS, Hong CW, et al. Histopathological risk factors for lymph node metastasis in submucosal invasive colorectal carcinoma of pedunculated or semipedunculated type. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:912–915. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.043539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines): colon cancer. Version 2. 2016. Fort Wathington (PA): National Comprehensive Cancer Network; c2017. [cited 2017 Jan 5]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN Guidelines): rectal cancer. Version 1. 2016. Fort Wathington (PA): National Comprehensive Cancer Network; c2017. [cited 2017 Jan 5]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, Tanaka S, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) Guidelines 2014 for treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20:207–239. doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0801-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ueno H, Mochizuki H, Hashiguchi Y, Shimazaki H, Aida S, Hase K, et al. Risk factors for an adverse outcome in early invasive colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:385–394. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi DH, Sohn DK, Chang HJ, Lim SB, Choi HS, Jeong SY. Indications for subsequent surgery after endoscopic resection of submucosally invasive colorectal carcinomas: a prospective cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:438–445. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318197e37f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tateishi Y, Nakanishi Y, Taniguchi H, Shimoda T, Umemura S. Pathological prognostic factors predicting lymph node metastasis in submucosal invasive (T1) colorectal carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:1068–1072. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suh JH, Han KS, Kim BC, Hong CW, Sohn DK, Chang HJ, et al. Predictors for lymph node metastasis in T1 colorectal cancer. Endoscopy. 2012;44:590–595. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(6 Suppl):S3–S43. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudo S. Endoscopic mucosal resection of flat and depressed types of early colorectal cancer. Endoscopy. 1993;25:455–461. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton S, Aaltonen L. WHO Classification of Tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC press; 2000. (World Health Organization classification of tumours; v. 2) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ueno H, Price AB, Wilkinson KH, Jass JR, Mochizuki H, Talbot IC. A new prognostic staging system for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2004;240:832–839. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143243.81014.f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toh EW, Brown P, Morris E, Botterill I, Quirke P. Area of submucosal invasion and width of invasion predicts lymph node metastasis in pT1 colorectal cancers. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:393–400. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith KJ, Jones PF, Burke DA, Treanor D, Finan PJ, Quirke P. Lymphatic vessel distribution in the mucosa and submucosa and potential implications for T1 colorectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:35–40. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181fb0e7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hase K, Shatney C, Johnson D, Trollope M, Vierra M. Prognostic value of tumor “budding” in patients with colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:627–635. doi: 10.1007/BF02238588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, Preisinger AC, Leppert M, et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:525–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimoda T, Ikegami M, Fujisaki J, Matsui T, Aizawa S, Ishikawa E. Early colorectal carcinoma with special reference to its development de novo. Cancer. 1989;64:1138–1146. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890901)64:5<1138::aid-cncr2820640529>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]