Abstract

Background and purpose — The most frequent cause of arthroplasty failure is aseptic loosening—often induced by particles. Abrasion material triggers inflammatory reactions with lymphocytic infiltration and the formation of synovial-like interface membranes (SLIM) in the bone–implant interface. We analyzed CD3 quantities in SLIM depending on articulating materials and possible influences of proven material allergies on CD3 quantities.

Patients and methods — 222 SLIM probes were obtained from revision surgeries of loosened hip and knee arthroplasties. SLIM cases were categorized according to the SLIM-consensus classification and to the particle algorithm. The CD3 quantities were analyzed immunohistochemically, quantified, and correlated to the particle types.

Results — Metal–metal pairings showed the highest CD3 quantities (mean 1,367 counted cells). CD3 quantities of metal–polyethylene (mean 243), ceramic–polyethylene (mean 182), and ceramic–ceramic pairings (mean 124) were significantly smaller. Patients with contact allergy to implant materials had high but not statistically significantly higher CD3 quantities than patients without allergies. For objective assessment of the CD3 response as result of a pronounced inflammatory reaction with high lymphocytosis (adverse reaction), a defined CD3 quantity per high power field was established, the “CD3 focus score” (447 cells/0.3 mm2, sensitivity 0.92; specificity 0.90; positive predictive value 0.71; negative predictive value 0.98).

Interpretation — The high CD3 quantities for metal–metal pairings may be interpreted as substrate for previously described adverse reactions that cause severe peri-implant tissue destruction and SLIM formation. It remains unclear whether the low CD3 quantities with only slight differences in the various non-metal–metal pairings and documented contact allergies to implant materials have a direct pathogenetic relevance.

In cases of aseptic loosening of an endoprosthesis the initially firm bonding of the implant to the bone is increasingly replaced by an intermediate layer of connective tissue, the SLIM (synovial-like interface membrane). This is a gradual, initially subclinical process triggering minimal implant migrations, which in this phase can be detected in vivo only by radiostereometric analysis (RSA) (Sesselmann et al. 2013, 2017). With increasing migration of the implants, successive loosening occurs.

Abraded particles play a considerable pathogenetic role in the formation of the SLIM, leading to peri-implant osteolysis at their maximum severity (Gehrke et al. 2003, Krenn et al. 2014b). Analysis of the SLIM removed during revisions serves for diagnosis and clarification of the etiology of joint prosthesis failure. Since the abraded particles are situated locally and transported away by the lymphatic system in only small quantities (Jell et al. 2006), they accumulate in the SLIM and trigger inflammatory processes. CD3 + (cluster of differentiation) T-lymphocytes in particular play an important role in this foreign body reaction (Gehrke et al. 2003, Krenn et al. 2014b). CD3 is a co-receptor on these T-lymphocytes, which helps to activate these cells. Immunohistochemical presentation and quantification of CD3+ lymphocytes is attributed a central diagnostic importance for various inflammatory diseases—for example, to celiac disease or microscopic colitis (Tosco et al. 2015, Fiehn et al. 2016).

It is known that metallic particles above all, especially of CoCrMb (cobalt–chromium–molybdenum), activate CD3+ lymphocytes (Thomas et al. 2008, 2015, Thomsen et al 2016). In particular high inflammatory activity with high lymphocytosis exists with dysfunctional metal–metal pairings, which is defined as an adverse reaction and is responsible for SLIM formation (Malchau et al. 1993, Lohmann et al. 2007, Mahendra et al. 2009, Perino et al. 2014). Recent studies show that other particles, such as polyethylene particles, can also trigger lymphocytosis (von Domarus et al. 2011). However, the matter of whether this CD3+ lymphocytosis is also a function of non-metallic pairing materials is not clear. Quantitative evaluations of cells generally have an ever greater diagnostic value in histopathological diagnostics of SLIM (Morawietz et al. 2009, Köbel et al. 2015, Tosco et al. 2015, Fiehn et al. 2016).

We evaluated the dependency of the immunologic reaction in the SLIM on the material of abrasion particles of revised implants. The quantitative dependency of CD3+ lymphocytosis on the tribological pairing was investigated for the first time. By specifying statistically a CD3 quantity limit (“CD3 focus score”) a diagnostic aid was achieved in the histopathological evaluation of joint prosthesis failure with respect to an adverse reaction. The material dependency of the CD3 infiltrate was analyzed for all material combinations. The type IV SLIM, which according to the definition shows no particle deposits and no macrophage infiltrates, was used for comparison. Furthermore we investigated whether a known contact allergy to the implant material causes increased CD3 quantities compared with analogous cases with a negative allergy test.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patient group

The SLIM originated from 222 independent cases of revision surgery because of aseptic loosening of cemented (n = 28) and cementless (n = 194) hip (n = 114) and knee (n = 108) endoprostheses. The mean age of these patients was 67 (37–92) years; 130 patients were female. The lifespan of the endoprostheses was on average 7 (0.3–30) years. In all cases a bacterial infection was ruled out histopathologically (count of neutrophil granulocytes) and microbiologically (culture of probes of the SLIM for 14 days).

Macroscopic processing

The synovial/SLIM diagnostics were conducted under accredited conditions (DIN EN ISO/IEC 17020) in the framework of histopathological diagnostics in a histopathological diagnosis center operating throughout Germany with a focus on orthopedic pathology (Center for Histopathology and Molecular Pathology, Trier, Germany). The macroscopic assessment, the macroscopic section, and the histopathological processing were carried out according to the S1 Guidelines under Protocol AG 11 of the DGOOC (Script AG 11 Implant incompatibility, ISBN 978-3-00-050115-9). Depending on the sample size and sample number, with a sample size of about 2 cm up to 3 paraffin block sections (so-called FFPE tissue blocks—formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue) were prepared per sample. Soft tissue was separated from bone tissue or tissue with osseous or calciferous inclusions, processed, and decalcified with acid. The sections (section thickness about 2 to 5 µm) were stained in the standard way (HE stain, Prussian blue reaction, and PAS (periodic acid-Schiff reaction) reaction). Particle detection and particle measurement were performed in all the sections.

HE staining, Prussian blue reaction, oil red staining

The HE staining, the PAS reaction, and the Prussian blue reaction were carried out fully automatically using the Leica ST 4040 stainer module (Leica Biosystems Nussloch GmbH, Nuszloch, Germany), and the oil red staining was carried out according to the published staining protocol (Krenn et al. 2014a) without automation.

Histopathological diagnostics and histopathological classification

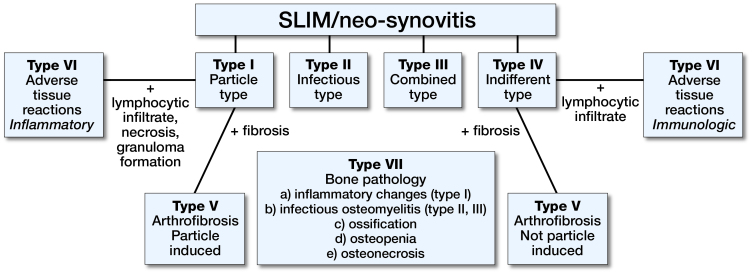

The histopathological diagnostics are based on the extended consensus classification of the SLIM (Figure 1), which divides every SLIM into 4 different main types for the entire pathological spectrum. Type I, the particle-induced type, occurs to an extent of about 55%. Characteristics are the histologically detectable particle deposits with a surrounding lymphocytic reaction (Krenn et al. 2014a, 2014b). In all cases the microbiological findings were negative and the histopathological criteria of infection were not met. The entire diagnostic classification was performed by an experienced pathologist specializing in orthopedic pathology (VK).

Figure 1.

Consensus classification of the SLIM (Krenn et al. 2014b). The SLIM can be categorized in four histopathological main types (I–IV) and three subtypes (V–VII).

Particle characterization according to the particle algorithm

The particle algorithm (Krenn et al. 2014a) is based on 3 fundamental criteria:

light microscopy morphological characteristics including size, form, and color;

optical polarization properties;

histochemical characteristics evaluated in the oil red staining and the Prussian blue reaction.

Immunohistochemistry

The immunohistochemical staining was carried out in a fully automated staining system (BenchmarkXT, IHC Slide Stainer of the Roche brand, Ventana Medical Solutions, Basel, Switzerland). The sections were first deparaffinized with xylene and an ethanol series. Cell conditioning was then first carried out at 95° C for 8 min using Cell Conditioning 1 (CC1), followed by a mild cell conditioning for 30 min. The primary antibody used was the anti-CD3 antibody (clone MMA, Roche, Basle, Switzerland)—a monoclonal murine antibody—(ready to use, according to Roche undiluted). The primary antibody serves for specific identification of CD3-positive lymphocytes. The sections were incubated with the antibody for 32 min. DAB (3,3’-diaminobenzidine; DAKO Denmark, Glostrup, Denmark) was used as the chromogen for the reaction with the peroxidase. The endogenous peroxidase was blocked by prior addition of H2O2. Hematoxylin (Harris-modified, Surgipath, Richmond, IL, USA) was used for counter-staining. Negative controls were established by leaving out the primary antibody.

CD3 quantification (evaluation mode of the CD3+ lymphocytosis)

The quantifying evaluation mode follows the principle of focal maximum infiltration (focus) according to the so-called CD15 focus score (Kölbel et al. 2015). The area in which the most CD3 lymphocytes are detectable is initially specified. The focus is set using lens 20; the field of vision is thus magnified 200-fold (image field of 0.3 mm2). The cells are counted in a single field of vision with maximum severity, which thus follows the principle of “worst area grading”. A particle detection corresponding to the pairing existed in each focus evaluated.

Statistics

Means (SD) are given for quantification of the lymphocytes.

The statistical evaluations and presentation of the graphics were compiled with the freely available R software environment (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; version 3.1.1, General Public License).

Box plots, scatter plots, and bar diagrams were used to present the graphs. To examine the significance (p-value), in addition to Student’s t-test, Welch’s t-test, and the chi-square test, linear regressions and a variance analysis (ANOVA: analysis of variance) were also used. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For the CD3 focus score the sensitivity, the specificity, the positive predictive value, and the negative predictive value were calculated.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interests

This work includes no studies on humans or animals. Under case number 837.304.14 (9534) the Ethics Commission of the Medical Board of Rheinland-Pfalz, Mainz has given approved the study. No funding was received for this study. No conflicts of interest declared.

Results

Material combinations of the pairings

The 222 cases investigated were divided into the following groups: 14 cases with ceramic–ceramic material combinations, 44 cases with ceramic–polyethylene material combinations, 49 cases with metal–metal material combinations, and 115 cases with metal–polyethylene material combinations.

Histopathological classification and particle characterization

SLIM type I and type IV: type I was present in 186 cases and type IV in 36 cases. Particle characterization by means of using the particle algorithm was possible beyond doubt in all the type I cases (n =186).

Quantification of the CD3+ lymphocytes

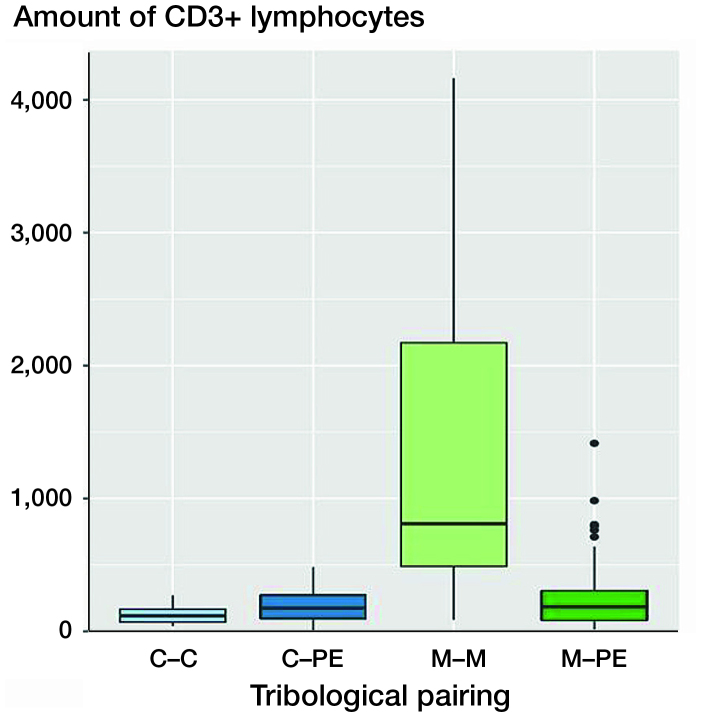

The results of the quantification of CD3+ lymphocytes can be summarized as follows (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5):

Figure 2.

Boxplots of CD3 quantities (number of CD3+ lymphocytes) of various pairings. The x-axis shows the different materials of the tribological pairings, the y-axis shows the amount of CD3+ lymphoctyes. Each black horizontal line shows the median of the group, the box below the median shows the lower quartile, the box above the median shows the upper quartile. For each group, the vertical lines are the whiskers that indicate the variability of the data outside the upper and lower quartiles. Black dots represent outliers. Metal–metal pairings (M–M) showed the highest amount of CD3+ lymphocytes. The other tribological pairings show all statistically significantly lower numbers of CD3+ lymphoctyes. C = ceramic; PE = polyethylene.

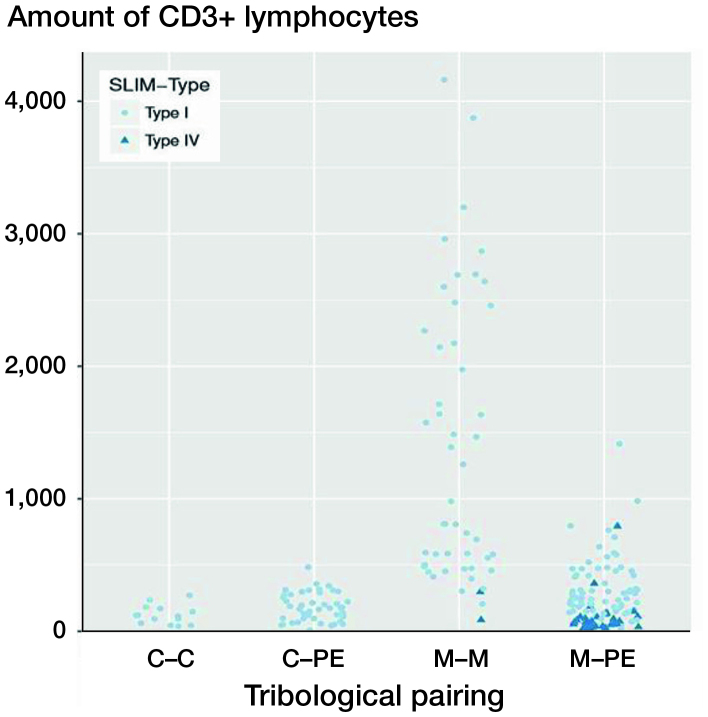

Figure 3.

CD3 quantities (number of CD3+ lymphocytes) as a function of the pairing and the SLIM types. The x-axis shows the different materials of the tribological pairings, the y-axis shows the amount of CD3+ lymphoctyes. Each dot represents a SLIM type I probe. Each triangle represents a SLIM type IV probe. Each case is represented by a pale-blue circle (SLIM type I) or a dark-blue triangle (SLIM type IV). Only the metal–metal and the metal–polyethylene groups include SLIM type IV. SLIM type IV probes show lower amounts of CD3+ lymphocytes in their group than SLIM type I probes. For abbreviations, see Figure 2 caption.

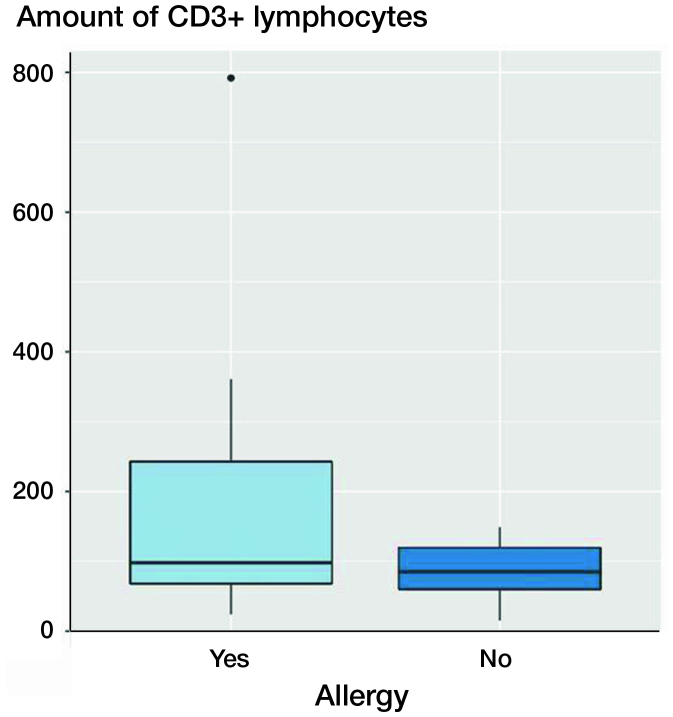

Figure 4.

Boxplots of CD3 quantities (number of CD3+ lymphocytes) in patients with and without contact allergy to metallic ingredients of the revised implant. The x-axis shows patients with confirmed positive cutaneous allergological findings and the patients without positive cutaneous allergological findings, the y-axis shows the amount of CD3+ lymphocytes. Each black horizontal line shows the median of the group, the box below the median shows the lower quartile, the box above the median shows the upper quartile. For each group, the vertical lines are the whiskers that indicate the variability of the data outside the upper and lower quartiles. Black dots represent outliers. Probes derived from patients with confirmed positive cutaneous allergological findings show more CD3+ lymphocytes.

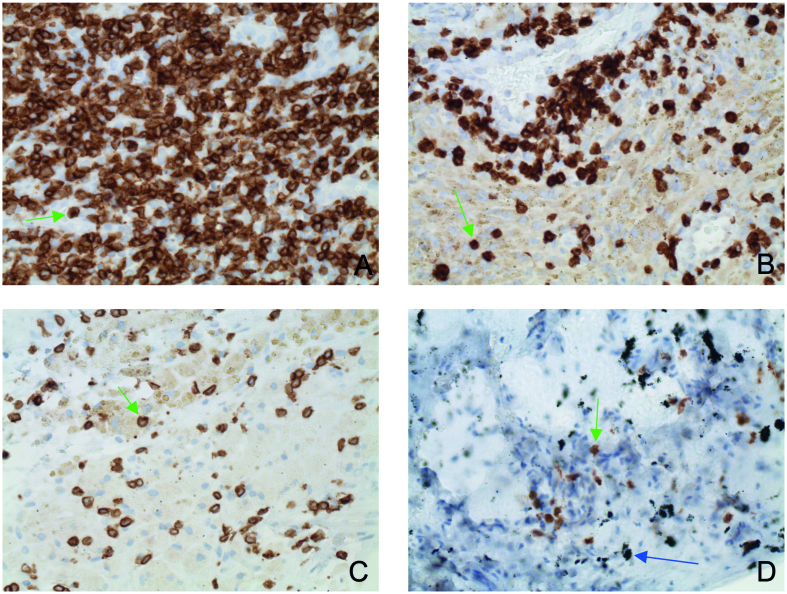

Figure 5.

CD3 quantities in the SLIM as function of abraded particle types and material combinations (indirect immunohistochemistry, original magnification about 200x) 5A: CD3 quantity with metal–metal pairing; 5B: CD3 quantity with metal–polyethylene pairing; 5C: CD3 quantity with ceramic–polyethylene pairing; 5D: quantity with ceramic–ceramic pairing. The green arrows indicate individual CD3+ lymphocytes. The blue arrow shows macroparticular ceramic material.

The various material pairings show significant differences in the CD3 quantities. The CD3 quantity was highest with the metal–metal pairings (mean 1,367 (1,056) counted cells). This was followed by combinations with metal–polyethylene (mean 243 (229)) and metal–ceramic (mean 182 (107)). The lowest CD3 quantities were present with the ceramic–ceramic pairings (mean 124 (71)).

The CD3 quantity of metal–metal pairings was statistically significantly higher compared with ceramic–ceramic (n =14, p < 0.001), ceramic–polyethylene (n = 44, p < 0.001), and metal–polyethylene (n = 115, p < 0.001).

The control group, SLIM type IV (n = 36), without particle detection showed the lowest CD3 quantity (mean 104 (139)) compared with SLIM type I (p < 0.001).

In patients in whom contact allergy to the implant material was detected, no significantly increased CD3+ lymphocytosis was found (p = 0.1).

A statistically significant difference between the metal–metal pairings and the non-metal–metal pairings was thus detectable. The quantification of the CD3+ lymphocytes showed that the highest CD3+ quantities were present with metal–metal pairings with a mean of about 1,500 cells (see Figures 2, 3). Metal–polyethylene and ceramic–polyethylene pairings follow with similar means. The lowest CD3 quantities were detectable with ceramic–ceramic pairings. Figure 2 shows the CD3 quantities of various material combinations; in Figure 3 the SLIM type is additionally taken into account with type IV SLIMs showing significantly lower CD3 quantities than SLIM type I (p < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference between ceramic–ceramic, ceramic–polyethylene, and metal–polyethylene pairings of type I SLIMs compared with type IV SLIMs of metal–metal or metal–polyethylene pairings.

CD3 focus score

On the basis of the various material-dependent CD3 quantities a CD3 quantity (CD3 focus score), which can separate an adverse reaction from a non-adverse reaction by the CD3 quantity, was specified. This threshold value is 447 cells per focus (0.3 mm2) (sensitivity =0.92, specificity =0.90, positive predictive value =0.71, negative predictive value =0.98).

Contact allergy to the implant material used

The CD3 quantities of 11 patients with a positive cutaneous allergological finding to the implanted material were compared with comparable cases without a detected allergy. The CD3 quantity in the few patients with allergy was increased, but not statistically significant (p = 0.1).

Dependency on the materials of the tribological pairing, sex, age, and lifespan

In summary, the CD3 quantity was statistically significantly dependent on the materials of the tribological pairing. Sex, age, and lifespan had no significant influence on the CD3 quantity.

Discussion

Statistically significant difference between the metal–metal pairings and the non-metal–metal pairings

We found that the CD3 quantity in type I SLIMs depended significantly on the material of the tribological pairing. Sex, age, and lifespan had no significant influence on the CD3 quantities. A statistically significant difference was detectable between the metal–metal pairings and the non-metal–metal pairings. This difference allows the assumption that with metal–metal pairings in particular a pronounced lymphocytosis and inflammatory reaction exists, which is described as an adverse reaction in the literature literature (Park et al. 2005, Lohmann et al. 2007, Mahendra et al. 2009, Perino et al. 2014, Ricciardi et al. 2016). It can therefore be concluded that with the other pairings with a comparatively significantly lower CD3 quantity a lesser, or at least not existing to the same extent, destructive inflammatory infiltration is present and in this sense an adverse reaction such as is present with a dysfunctional metal–metal pairing cannot be assumed.

Until recently metal–metal pairings were regarded clinically as a safe and long-lasting concept, but after introduction of so-called large-head prostheses early complications arose with this pairing (Park et al. 2005, Lohmann et al. 2007). These metal–metal combinations also had shortened lifespans (Malchau et al. 1993, Lohmann et al. 2007), so that metal–metal pairings have largely been abandoned in endoprostheses.

Adverse reaction and CD3 focus score

The cause for failure is assumed to be an increased abrasion of metal and a pronounced inflammatory reaction with a high lymphocytosis, which is called an “adverse reaction” and causes an extremely severe peri-implant tissue destruction and SLIM formation (Malchau et al. 1993, Park et al. 2005, Lohmann et al. 2007). These data agree with our study: A statistically significant difference between the metal–metal pairings and the non-metal–metal pairings was detected. CD3+ lymphocytic infiltrates were also found in all the other non-metal–metal pairings used, and this finding also conforms to published data (von Domarus et al. 2011). We found the lowest CD3 quantities with ceramic–ceramic pairings, followed by ceramic–polyethylene and metal–polyethylene pairings. Lymphocytic infiltrates were observed to a greater extent in this group only if abraded particles were present. Type IV SLIMs without abraded particles showed no or only low CD3 quantities. It can therefore be concluded that with the other pairings with a comparatively significantly lower CD3 quantity a lesser destructive inflammatory reaction is present. For diagnostic demarcation of an adverse (high CD3 quantity) from a non-adverse reaction (low CD3 quantity) in the SLIM we propose a CD3 focus score value of 447.

Implant material allergies in joint endoprostheses

Allergic reactions to metallic antigens are widespread: 13% of the population show an allergic reaction of the delayed type (type 4) to nickel (Schäfer et al. 2001). A contact allergy of the skin does not necessarily lead to an allergic reaction to the endoprosthesis material (Thomsen et al. 2016). In the cases we investigated the 11 cases with a confirmed positive cutaneous allergological finding showed a slightly increased CD3+ lymphocytosis compared with the comparison group without allergy, but no statistically significant differences were present. Current data nevertheless indicate that minimal CD3+ lymphocytosis can be of pathogenetic relevance in the context of implant material allergy due to a high chemokine production (Perino et al. 2014). An implant allergic reaction should therefore be diagnosed in a comprehensive as well as clinical context.

Finally, it can be said that a low CD3 quantity in the SLIM with a confirmed allergological finding may give an indication of an allergic reaction, but does not prove this (Lalor et al. 1991, Thomas et al. 2008, 2011, 2015).

Conclusions for practice

Whether the low CD3 quantities, the differences within the various non-metal–metal pairings and the CD3 quantities with a finding of positive allergy to the implant material have a pathogenetic origin is unclear and requires further studies. However, since high CD3 quantities of metal–metal pairings are a manifestation of an inflammatory destructive process, lower CD3 quantities could also be of pathogenetic relevance. By now no immunological or tissue markers exist for diagnosing an implant material allergy beyond doubt. Only by taking into account all the allergological, clinical and histopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular findings can an implant material allergy be diagnosed.

The fact that foreign-body materials lead to toxic and immunopathological reactions is confirmed. It is therefore important to use tissue-compatible pairings with low abrasion and minimal properties that might cause inflammatory reactions. The CD3 focus score not only can be used in SLIM diagnostics, but also may be helpful in the development of new biocompatible implant materials.

In summary this study suggests that abrasion particles play an important role in aseptic loosening, as they can induce severe inflammatory reactions. Above all, metal particles seem to induce massive infiltration of lymphocytes. Hence, the use of metal–metal pairings cannot be recommended.

FH: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript, and critical revision. MT, MGK, HR, PT: acquisition of data, drafting of manuscript, and critical revision. SS, MT, MH, JCH, MGK: drafting of manuscript, and critical revision. VK: study conception and design, drafting of manuscript, and critical revision.

Acta thanks Stephan Söder and Christof Wagner for help with peer review of this study.

References

- Fiehn A M, Engel U, Holck S, Munck L K, Engel P J.. CD3 immunohistochemical staining in diagnosis of lymphocytic colitis. Hum Pathol 2016; 48: 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke T, Sers C, Morawietz L, Fernahl G, Neidel J, Frommelt L, et al. . Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand is expressed in resident and inflammatory cells in aseptic and septic prosthesis loosening. Scand J Rheumatol 2003; 32 (5): 287–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jell G, Kerjaschki D, Revell P, Al-Saffar N.. Lymphangiogenesis in the bone-implant interface of orthopedic implants: Importance and consequence. J Biomed Mater Res A 2006; 77 (1): 119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kölbel B, Wienert S, Dimitriadis J, Kendoff D, Gehrke T, Huber M, et al. . CD15 focus score for diagnostics of periprosthetic joint infections: Neutrophilic granulocytes quantification mode and the development of morphometric software (CD15 quantifier). Z Rheumatol 2015; 74 (7): 622–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenn V, Thomas P, Thomsen M, Kretzer J P, Usbeck S, Scheuber L, et al. . Histopathological particle algorithm: Particle identification in the synovia and the SLIM. Z Rheumatol 2014a; 73 (7): 639–49. In German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenn V, Morawietz L, Perino G, Kienapfel H, Ascherl R, Hassenpflug G J, et al. . Revised histopathological consensus classification of joint implant related pathology. Pathol Res Pract 2014b; 210 (12): 779–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalor P A, Revell P A, Gray A B, Wright S, Railton G T, Freeman M A.. Sensitivity to titanium: A cause of implant failure? J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991; 73 (1): 25–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann C H, Nuechtern J V, Willert H G, Junk-Jantsch S, Ruether W, Pflueger G.. Hypersensitivity reactions in total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2007; 30 (9): 760–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahendra G, Pandit H, Kliskey K, Murray D, Gill H S, Athanasou N.. Necrotic and inflammatory changes in metal-on-metal resurfacing hip arthroplasties. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (6): 653–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchau H, Herberts P, Ahnfelt L.. Prognosis of total hip replacement in Sweden: Follow-up of 92,675 operations performed 1978-1990. Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64 (5): 497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawietz L, Tiddens O, Mueller M, Tohtz S, Gansukh T, Schroeder J H, et al. . Twenty-three neutrophil granulocytes in 10 high-power fields is the best histopathological threshold to differentiate between aseptic and septic endoprosthesis loosening. Histopathology 2009; 54 (7): 847–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y S, Moon Y W, Lim S J, Yang J M, Ahn G, Choi Y L.. Early osteolysis following second-generation metal-on-metal hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87 (7): 1515–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perino G, Ricciardi B F, Jerabek S A, Martignoni G, Wilner G, Maass D, Goldring S R, Purdue P E.. Implant based differences in adverse local tissue reaction in failed total hip arthroplasties: A morphological and immunohistochemical study. BMC Clin Pathol 2014; 5; 14: 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi B F, Nocon A A, Jerabek S A, Wilner G, Kaplowitz E, Goldring S R, Purdue P E, Perino G.. Histopathological characterization of corrosion product associated adverse local tissue reaction in hip implants: A study of 285 cases. BMC Clin Pathol 2016; 27; 16: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer T, Böhler E, Ruhdorfer S, Weigl L, Wessner D, Filipiak B, et al. . Epidemiology of contact allergy in adults. Allergy 2001; 56 (12): 1192–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesselmann S, Forst R, Tschunko F.. Radiostereometric analysis of hip implants: A critical review of methodology and future directions. OA Musculoskeletal Medicine 2013; 1 (4): 31. [Google Scholar]

- Sesselmann S, Hong Y, Schlemmer F, Wiendieck K, Söder S, Hussnaetter I, et al. . Migration measurement of the cemented Lubinus SP II hip stem: A 10-year follow-up using radiostereometric analysis. Biomed Tech (Berl) 2017; 62(3): 271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Schuh A, Ring J, Thomsen M.. Orthopedic surgical implants and allergies: Joint statement by the implant allergy working group (AK 20) of the DGOOC (German association of orthopedics and orthopedic surgery), DKG (German contact dermatitis research group) and dgaki (German society for allergology and clinical immunology). Orthop 2008; 37 (1): 75–88. In German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Thomas M, Summer B, Dietrich K, Zauzig M, Steinhauser E, et al. . Impaired wound-healing, local eczema, and chronic inflammation following titanium osteosynthesis in a nickel and cobalt-allergic patient: A case report and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 (11): e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, von der Helm C, Schopf C, Mazoochian F, Frommelt L, Gollwitzer H, et al. . Patients with intolerance reactions to total knee replacement: Combined assessment of allergy diagnostics, periprosthetic histology, and periimplant cytokine expression pattern. Biomed Res Int 2015; 910156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M, Krenn V, Thomas P.. Adverse reactions to metal orthopedic implants after knee arthroplasty. Hautarzt 2016; 67 (5): 347–51. In German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosco A, Maglio M, Paparo F, Greco L, Troncone R, Auricchio R.. Discriminant score for celiac disease based on immunohistochemical analysis of duodenal biopsies. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015; 60 (5): 621–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Domarus C, Rosenberg J P, Rüther W, Zustin J.. Necrobiosis and T-lymphocyte infiltration in retrieved aseptically loosened metal-on-polyethylene arthroplasties. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (5): 596–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]