Abstract

Background and purpose — Given similar functional outcomes with mobile and fixed bearings, a difference in survivorship may favor either. This study investigated the risk of aseptic loosening for the most used subtypes of mobile-bearing rotating-platform knees, in Norway and Australia.

Patients and methods — Primary TKRs reported to the Norwegian and Australian joint registries, between 2003 and 2014, were analyzed with aseptic loosening as primary end-point and all revisions as secondary end-point. We hypothesized that no difference would be found in the rate of revision between rotating-platform and the most used fixed-bearing TKRs, or between keeled and non-keeled tibia. Kaplan–Meier estimates and curves, and Cox regression relative risk estimates adjusted for age, sex, and diagnosis were used for comparison.

Results — The rotating-platform TKRs had an increased risk of revision for aseptic loosening compared with the most used fixed-bearing knees, in Norway (RR =6, 95% CI 4–8) and Australia (RR =2.1, 95% CI 1.8–2.5). The risk of aseptic loosening as a reason for revision was highest in Norway compared with Australia (RR =1.7, 95% CI 1.4–2.0). The keeled tibial component had the same risk of aseptic loosening as the non-keeled tibia (Australia). Fixation method and subtypes of the tibial components had no impact on the risk of aseptic loosening in these mobile-bearing knees.

Interpretation — The rotating-platform TKRs in this study appeared to have a higher risk of revision for aseptic loosening than the most used fixed-bearing TKRs.

The LCS complete implant, also called LCS MBT (Low Contact Stress Mobile Bearing Tray, DePuy, Warsaw, IN, USA), is a modified version of the classical tibial rotating platform introduced at the beginning of the century. In a previous report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR), the LCS MBT was found to have an increased risk of aseptic loosening, particularly on the tibial side (Gothesen et al. 2013). Despite the overall survival of these total knee replacements (TKRs) remaining acceptable, a 7-fold increased risk of tibial loosening was identified, prompting further investigations. A retrieval study suggested that the bonding between cement and implant had weakened due to a lower roughness of the cement–implant interface (Kutzner, personal communication). It has been suggested that other causes increasing the risk of aseptic loosening and osteolysis may include increased wear particle production related to the mobile-bearing design, or a difficult surgical technique (Huang et al. 2002). Recent reports from large registries have confirmed the higher risk of revision with a mobile-bearing design, and have advised caution when selecting such implants (Graves et al. 2014, Namba et al. 2014).

The mobile-bearing design was developed to reduce shear and tear forces and thereby reduce wear of the insert (Buechel and Pappas 1986). In addition, a mobile bearing is designed to be less rigid, and mechanically closer to a normal knee. Improved patellar tracking was claimed to be one of the advantages of this design. However, few independent investigators have been able to show improved function with this design (Ranawat et al. 2004, Lygre et al. 2010, Hofstede et al. 2015). If function is not improved and the revision rate increases, the use of mobile-bearing TKRs in standard knee replacement will be questionable.

Increased risk of mobile-bearing loosening appears to be a global issue. However, local variation including operative techniques, clinical and radiological interpretation of information, different types of surface geometry, and design of the implants may be important factors leading to varying results. Previous registry studies do not provide much information about various subtypes and designs of mobile-bearing knees. The rotating-platform design is the most used mobile-bearing design; therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate this design in further detail. The most used subtypes of the rotating-platform design used in Australia and Norway were selected for comparison between and within countries using catalogue numbers to compare identical implants. Registry data from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) and the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR) were analyzed. Our hypothesis was that the most used fixed-bearing TKRs, in Norway and Australia, had a lower risk of aseptic loosening than the most used mobile-bearing TKRs.

Patients and methods

The NAR has collected data on TKRs since 1994 and the AOANJRR since 1999. The AOANJRR had its first year of complete national registering in 2003. Hence, the study includes selections from complete datasets reported from 2003 to 2014. The completeness of the data collection in the NAR and AOANJRR is 96–99% (Furnes 2015, Graves 2015).

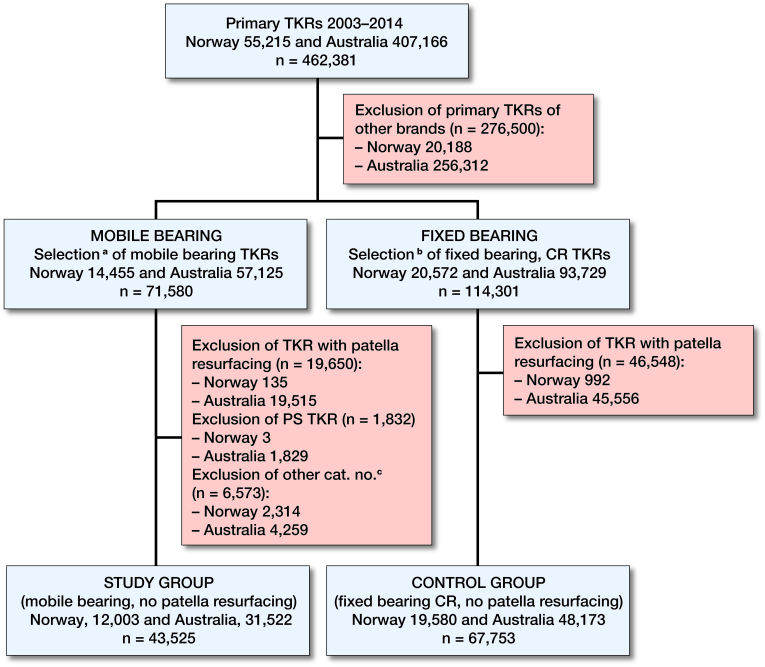

From the Norwegian registry 12,003 patients with rotating-platform TKRs, and 19,580 patients with fixed-bearing TKRs, were included (mean age 69 (SD 10), 36% men). From the Australian registry 31,522 patients with rotating-platform TKRs, and 48173 patients with fixed-bearing TKRs (mean age 68 (SD 9), 45% men), were included. A prospective observational study was performed, and primary mobile-bearing LCS Complete (Low Contact Stress, DePuy, Warsaw, IN, USA) and PFC Sigma (Press Fit Condylar, DePuy, Leeds, UK) TKRs, with rotating platform, without patella resurfacing, were selected for analysis (Table 1, Figure 1). A non-keeled tibial component was used in 90% of cases in Norway and 49% in Australia (catalogue numbers 129431, 129432). The keeled version of the tibial component was used in 10% of cases in both countries (catalogue numbers 129433, 129434). The Duo-fix version was used in <1% of cases in Norway and 41% in Australia (catalogue numbers 9003). Any type of fixation was included in the initial datasets. For sub-analyses, fixation of the tibial component was targeted. Fully cemented and hybrids with cemented tibial components were allocated to the cemented group, whereas fully cementless and hybrids with cementless tibial components were allocated to the cementless group. For controls, the 3 most used fixed-bearing TKRs (all fixations) in each country were selected (Norway: AGC (Anatomic and Universal, Biomet, Warsaw, IN, USA), NexGen (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA), Profix (Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN, USA). Australia: Triathlon (Stryker, Mahwah, NJ, USA), NexGen, PFC Sigma (fixed bearing)) (Table 1). Anonymized datasets from Norway and Australia, from the years 2003 to 2014, were merged by converting the respective variables into common variables, using the Australian hierarchy system for ranking of revision diagnoses (Graves 2015).

Table 1.

Demographics of included primary TKRs in Norway and Australia

| Study group | Control group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mobile-bearing TKRs | fixed-bearing TKRs | |||||

| Norway | Australia | p-valuea | Norway | Australia | p-valuea | |

| Number | 12,003 | 31,522 | 19,580 | 48,173 | ||

| Men (%) | 36 | 45 | < 0.01 | 36 | 45 | < 0.01 |

| Age years (SD) | 68.7 (9.6) | 68.0 (9.3) | < 0.01 | 69.2 (9.7) | 68.3 (9.2) | < 0.01 |

| Primary diagnosis (%) | ||||||

| Primary osteoarthritis | 91 | 98 | 89 | 99 | < 0.01 | |

| Other | 9 | 2 | 11 | 1 | ||

| Fixation, n (%) | ||||||

| Cemented | 9,615 (81) | 5,999 (19) | 14,732 (76) | 21,425 (45) | ||

| Cementless | 1,362 (11) | 18,377 (58) | 1,062 (5) | 10,126 (21) | ||

| Hybrid (cemented tibia) | 975 (8) | 6,767 (22) | 3,674 (19) | 16,551 (34) | ||

| Hybrid (cementless tibia) | 3 (0) | 379 (1) | 22 (0) | 71 (0) | ||

| Missing | 48 | 0 | 90 | 0 | ||

| Mobile-bearing subtype tibia | ||||||

| LCS Completeb (MBT) | 12,003 | 31,522 | ||||

| No keel, n (%) | 10,764 (90) | 15,415 (49) | ||||

| Keel, n (%) | 1,148 (10) | 3,208 (10) | ||||

| Duo-fix, n (%) | 91 (0) | 12,899 (41) | ||||

| Controls | ||||||

| AGC, n (%) | 1,622 (8) | |||||

| NexGen, n (%) | 5,347 (27) | 16,609 (35) | ||||

| PFC Sigma, n (%) | 9,231 (19) | |||||

| Profix, n (%) | 12,611 (65) | |||||

| Triathlon, n (%) | 22,333 (46) | |||||

| Computer navigation, n (%) | 1,684 (14) | 2,384 (8) | 1,722 (10) | 11,286 (23) | ||

Study group: Mobile bearing knees with an LCS Complete tibial component catalogue numbers 12943 or 9003. Control group: 3 most used fixed-bearing, cruciate-retaining TKRs without patella resurfacing, in Norway and Australia.

P-values are generated on the basis of differences between groups using chi-square test for sex and diagnosis, and independent samples t-test for age difference.

LCS Complete (also called LCS MBT) and PFC Sigma have identical tibial components (cat. no: 1294-31/32 (no-keel) and 1294-33/34 (keel)). The Duo-fix version has cat. no: 9003. For simplicity this component is called LCS Complete in this paper.

Figure 1.

Selection of study and control groups from the Norwegian and Australian joint replacement registries, 2003–2014.

aMobile-bearing brands (LCS and PFC Sigma).

bFixed-bearing cruciate-retaining brands, 3 most used in Norway (Profix, NexGen, AGC) and in Australia (Triathlon, NexGen, PFC Sigma).

cOther tibial component catalogue numbers than 12943 and 9003.

TKR = total knee replacement. CR = cruciate retaining. PS = posterior stabilized.

Cat. no. = catalogue number.

Statistics

The null hypothesis assumed a similar risk of revision for aseptic loosening when TKRs with a rotating-platform tibial component were compared with the most used fixed-bearing knees within the 2 countries, and similar outcome between the countries. Also, the results for the keeled vs. the non-keeled versions used within Australia were expected to be similar. Demographics were analyzed by descriptive analyses, using the chi-square test for categorical data (sex and diagnosis) and Student’s t-test for age difference. A reversed Kaplan–Meier (K–M) method was used to calculate the median follow-up time (Schemper and Smith 1996). Survivorship was calculated by the K–M method, and relative risk estimates (RR) were derived from a Cox multiple regression model with adjustments for age, sex, fixation, and diagnosis. The proportional hazards assumption of the Cox regression model was tested and considered to be satisfactory, except for a negligible divergence during the first 3 months of the Norwegian dataset (see Supplementary data). Survival curves were constructed by K–M estimates. Confidence intervals of 95% (CI) were reported. Tests were 2-sided and p-values <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

The survival analyses were based on an assumption of non-informative censoring. The validity of this assumption could be debatable since knees in one treatment group could be more likely to be censored due to, for example, pain than knees in the other treatment group. To account for possible bias due to informative censoring we performed a sensitivity analysis to check whether our conclusions would be any different by using death and other revision reasons as competing risk factors (Fine and Gray). This sensitivity analysis did only marginally change our results and did not alter our conclusions (Andersen et al. 2012). SPSS® Statistics version 23 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analyses.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

Written consent from each patient is required for the collection of Norwegian data, according to a concession from the Norwegian Data Inspectorate issued September 15, 2014 (ref.no:03/00058-20/CGN). For Australian data, the patients have the opportunity to opt out; otherwise their data will be collected and managed by the AOANJRR, according to their obligations, as a Federal Quality Assurance activity. The first author received funding from the Western Norway Regional Health Authority (Helse Vest RHF) to finance a visit to the AOA NJRR. None of the other authors have anything to disclose with relevance to the contents of this paper.

Results

The selected study groups consisted of 43,525 mobile-bearing, non-posterior-stabilized, rotating-platform TKRs, without patella resurfacing, reported to the national joint replacement registries of Norway (n = 12,003) and Australia (n = 31,522) during the years 2003–2014 (Table 1, Figure 1). The most used subtype in both countries was the non-keeled version (Norway n = 10,764, Australia n = 15,415). Some keeled components were used in Norway (n = 1,148) and Australia (n = 3,208), and Duo-fix (intended for cementless fixation and no keel) was rarely used in Norway (n = 91) and often used in Australia (n = 12,899). For control groups, the 3 most used fixed-bearing CR TKRs, without patella resurfacing, were selected in Norway (n = 19,580) and Australia (n = 48,173, Figure 1, Table 1).

Survival estimates, aseptic loosening as end-point

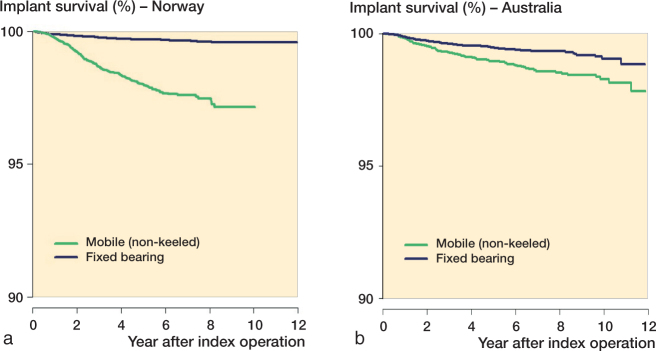

The 10-year K–M survival estimates with aseptic loosening as endpoint showed a lower survival rate (%) for the mobile-bearing groups compared with the fixed-bearing groups (97.2 vs. 99.6 in Norway, and 98.2 vs. 99.0 in Australia) (Table 2 and 3, Figure 2).

Table 2.

K–M survival (not revised due to aseptic loosening) by LCS Complete tibial design and fixation method, of primary cruciate-retaining TKRs without patella resurfacing, reported to the Norwegian and Australian joint replacement registries between 2003 and 2014. K–M survival estimate was not calculated when median follow-up was less than a year, number of patients in the group was less than 100, or when number of patients at risk was less than 50. Relative risk (RR) for aseptic loosening estimated by Cox regression analysis adjusting for age, sex, and preoperative diagnosis, RR1 with Australian non-keeled as reference, RR2 with reference to country-specific control group (3 most used fixed bearings).

| Country Group |

Implant type | Tibial fixation |

Total (n) | Revised for aseptic loosening (n, ‰) |

Median follow-up (years) |

K–M survival 10 years (%, 95% CI) |

At risk (n) | Cox RR 1 | Cox RR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | |||||||||

| Control | Fixed bearing | Any fixation | 48,173 | 195 (4) | 3.4 | 99.0 (98.8–99.2) | 1,170 | 1 (ref.) | |

| Study | Mobile bearing | Any fixation | 31,522 | 354 (11) | 98.2 (98.0–98.4) | 2,867 | 2.1 (1.8–2.5) | ||

| Non-keeledb | Any fixation | 15,415 | 143 (9) | 4.3 | 98.3 (97.9–98.7) | 1,059 | 1 (ref.) | 2.0 (1.6–2.4) | |

| Cemented | 9,541 | 78 (8) | 5.1 | 98.4 (98.0–98.8) | 776 | a1 | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | ||

| Cementless | 5,874 | 65 (11) | 2.8 | 98.1 (97.5–98.7) | 373 | a1.5 (1.0–2.0) | 2.5 (1.9–3.3) | ||

| Keeledc | Any fixation | 3,208 | 35 (11) | 5.5 | 98.3 (97.7–98.9) | 510 | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 2.0 (1.4–2.9) | |

| Cemented | 3,206 | 35 (11) | 5.5 | 97.6 (96.0–99.2) | 139 | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 2.0 (1.4–2.9) | ||

| Cementless | 2 | 0 | 5.7 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Duo-fixd | Any fixation | 12,899 | 176 (14) | 6.2 | 98.2 (97.8–98.6) | 2,891 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 2.2 (1.8–2.8) | |

| Cemented | 19 | 0 | 7.3 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Cementless | 12,880 | 176 (14) | 6.2 | 98.1 (97.7–09.5) | 2,885 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 2.3 (1.8–2.8) | ||

| Norway | |||||||||

| Control | Fixed bearing | Any fixation | 19,580 | 51 (3) | 4.6 | 99.6 (99.4–99.8) | 4,127 | 1 (ref.) | |

| Study | Mobile bearing | Any fixation | 12,003 | 178 (15) | 97.2 (96.6–97.8) | 825 | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | 6.0 (4.4–8.2) | |

| Non-keeledb | Any fixation | 10,764 | 178 (17) | 4.4 | 97.1 (96.5–97.7) | 817 | 1.8 (1.5–2.3) | 6.2 (4.5–8.4) | |

| Cemented | 9,802 | 169 (17) | 4.5 | 97.1 (96.5–97.7) | 854 | 2.4 (1.8–3.1) | 6.4 (4.7–8.8) | ||

| Cementless | 914 | 9 (10) | 3.9 | 97.7 (94.9–100) | 73 | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 3.4 (1.7–7.0) | ||

| Keeledc | Any fixation | 1,148 | 0 | 0.9 | – | – | – | – | |

| Cemented | 785 | 0 | 0.9 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Cementless | 363 | 0 | 0.9 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Duo-fixd | Any fixation | 91 | 0 | 4.9 | – | – | – | – | |

| Cemented | 3 | 0 | 8.1 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Cementless | 88 | 0 | 4.9 | – | – | – | – |

Cementless compared with cemented non-keeled tibia components within Australia.

K–M = Kaplan–Meier. Cox RR1/RR2 = Cox regression risk estimates 1 and 2.

cat. no: 129431, 129432

cat. no: 129433, 129434

cat. no: 9003

Table 3.

10-year K–M survival data for revision due to aseptic loosening for the control groups, i.e. the 3 most common fixed bearing implants in each country

| Country Group |

Subgroup (Implant type) |

Tibial fixation |

Total (n) | Revised for aseptic loosening (n, ‰) |

Median follow-up (years) |

K–M survival 10 years (%, 95% CI) |

At risk (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norway | |||||||

| Control | All | Any | 19,580 | 51 (3) | 4.6 | 99.6 (99.4–99.8) | 4,127 |

| Profix | Any | 12,611 | 27 (2) | 5.7 | 99.7 (99.5–99.9) | 3,401 | |

| NexGen | Any | 5,347 | 11 (2) | 1.2 | 99.6 (99.4–99.8) | 952 | |

| AGC | Any | 1,622 | 13 (8) | 6.6 | 99.0 (98.4–99.6) | 623 | |

| Australia | |||||||

| Control | All | Any | 48,173 | 195 (4) | 3.4 | 99.0 (98.8–99.2) | 1,170 |

| Triathlon | Any | 22,333 | 68 (3) | 3.1 | 99.4 (99.2–99.6) | 1,726 | |

| NexGen | Any | 16,609 | 76 (5) | 3.3 | 99.2 (99.0–99.4) | 1,459 | |

| PFC Sigma | |||||||

| fixed bearing | Any | 9,231 | 51 (6) | 4.9 | 98.9 (98.5–99.3) | 793 |

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves with aseptic loosening as end-point. Mobile-bearing rotating-platform knees compared with fixed-bearing knees in Norway and Australia. (a) Mobile-bearing rotating-platform non-keeled knees (all fixations, without patella resurfacing) compared with the three most used fixed-bearing cruciate-retaining knees (all fixations, without patella resurfacing) in Norway. (b) Same selection criteria as above applied to Australian data.

Risk estimates, aseptic loosening as end-point

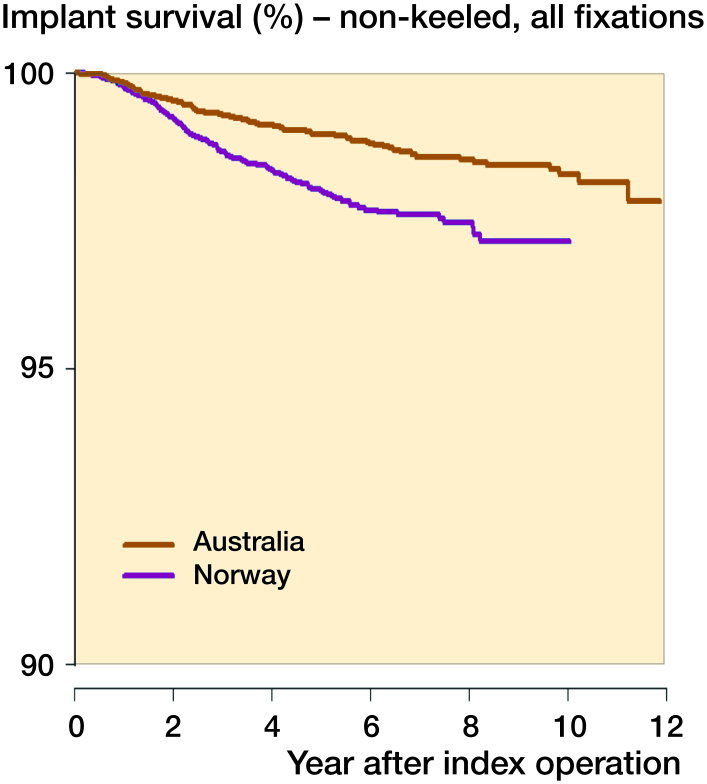

The adjusted Cox regression analysis estimating the risk of revision for aseptic loosening showed a 6-fold increased risk for the Norwegian study group compared with the country-specific control group, and a 2-fold increased risk for the Australian study group (Table 2). The risk of revision for aseptic loosening was higher in Norway compared with Australia (RR =1.7) (Table 2, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves with aseptic loosening as end-point. Mobile-bearing rotating-platform non-keeled knees (all fixations, without patella resurfacing) in Norway and Australia, a comparison between countries.

Various fixation and design results, aseptic loosening as end-point

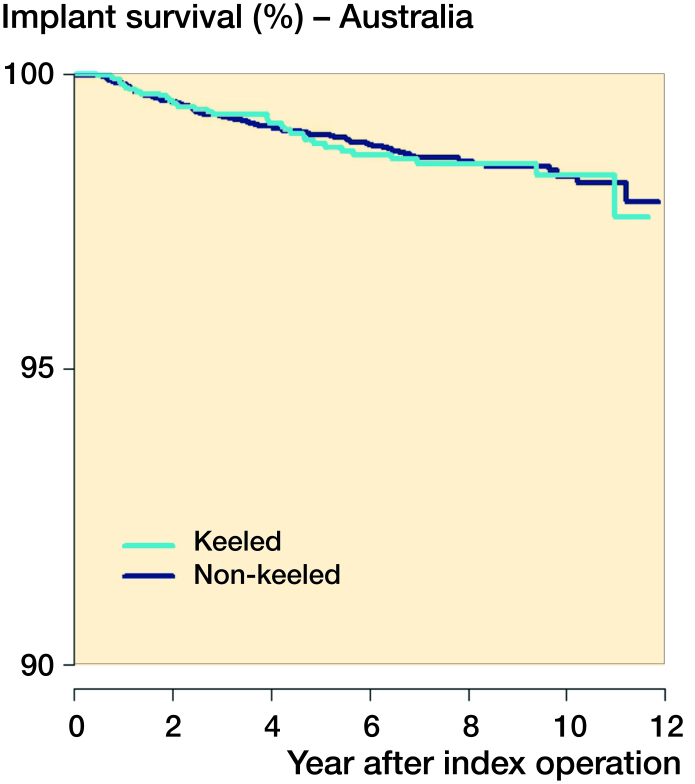

A sub-analysis of fixation technique showed that the cemented non-keeled tibias were at a higher risk in Norway than in Australia (RR =2.4), whereas the cementless non-keeled tibias did not show any difference between countries. However, within Australia, the cementless non-keeled tibias had a statistically significantly higher risk for aseptic loosening than the cemented tibias (RR =1.5, CI 1.0–2.0, p = 0.03) (see Table 2). For the keeled tibias there was a short follow-up (< 1 year), and Duo-fix subtypes were few (n = 91) in Norway, hence a comparison with Australian data was not justified for these subtypes. However, within Australia these subtypes had a lower survival, similar to the non-keeled subtype, in comparison with the fixed-bearing group (keeled RR =2.0, Duo-fix RR =2.2) (Table 2). Within Australia there were no differences in survival rates for the 3 subtypes of the rotating platform (non-keeled, keeled (RR =1.0) and Duo-fix (RR =1.1), using non-keeled as reference (Table 2, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves with aseptic loosening as end-point. Mobile-bearing rotating-platform non-keeled compared with keeled knees within Australia (Australian data only).

Risk of revision for any reason as end-point

However, when comparing rotating platform with fixed bearing, using revision for any reason as a secondary end-point, the risk was higher for the rotating-platform group in both countries (Norway, RR =1.4, Australia, RR =1.6), and the K–M overall survival estimates were higher in the fixed-bearing TKRs (Table 4). Subdividing into age categories and sex did not markedly change the results. The overall survival (all revisions included) showed almost identical K–M survival rates (Norway: 93%, Australia: 93.5), and Cox risk estimate (RR =1.1), between countries (Table 4).

Table 4.

10-year K–M survival data and relative risk (RR) estimates by Cox regression analysis adjusting for age, sex, and preoperative diagnosis for revision due to any reason

| Country Group |

Implant type | Tibial fixation |

Total (n) | Revised for any reason (n, ‰) |

Median follow-up (years) |

K–M survival 10 years (%, 95% CI) |

At risk (n) | Cox RR1a | Cox RR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | |||||||||

| Control | Fixed bearing | Any | 48,173 | 1,071 | 3.4 | 95.9 (95.5–96.3) | 1,170 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| Study | Mobile bearing | Any | 31,522 | 1,403 | 5.4 | 93.5 (93.1–93.9) | 2,723 | 1 (ref.) | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) |

| Norway | |||||||||

| Control | Fixed bearing | Any | 19,580 | 599 | 4.6 | 95.5 (95.1–95.9) | 1,737 | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | 1 (ref.) |

| Study | Mobile bearing | Any | 12,003 | 495 | 4.1 | 93.0 (91.6–94.4) | 155 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) |

Cox regression risk estimates of Norwegian study or control group with corresponding Australian study or control group as reference

Discussion

We found an increased risk of aseptic loosening for the most used subtypes of rotating platforms in mobile TKR. In comparison with the most used fixed-bearing knees, the rotating-platform knees had an increased overall risk of revision (revision for any reason as end-point), largely due to an increased risk of aseptic loosening regardless of fixation or variations of the under-surface or stem (keel or no keel). The difference between rotating-platform and fixed-bearing knees, in relation to aseptic loosening as the endpoint, seemed to be greater in Norway than in Australia. However, when comparing the overall survival of the rotating platform knees in Norway versus Australia, the results were similar.

The strength of our study was the large number of knee replacements included, and the combination of data from the 2 countries using identical catalogue numbers to identify and compare the same implant types (Sedrakyan et al. 2014). Consequently, the external validity of the results is good and the outcomes should be applicable to most orthopedic surgeons around the world (Namba et al. 2011). There were limitations in the demographic differences and in the lack of standardized reporting forms for cause of revision between the 2 countries. These issues have also been identified in a previous comparative study between Norway and a US registry (Paxton et al. 2011). In the Australian study cohort, there were a higher proportion of males, and the average age was 0.7 years lower than in the Norwegian study cohort. These differences were almost identical in the control cohorts. Due to the strict longevity and revision cause perspective of this registry study, the clinical scores and functional status of the patients were not evaluated. Previous publications and reviews have addressed this issue (Hofstede et al. 2015), and the use of patient-related outcome scores in registries, as recently established by several registries, will add important information to our findings in the future.

One would generally expect younger males to have an elevated revision rate, hence these differences were adjusted for in the Cox regression analysis (Graves 2015). However, in this study the Australian patients (younger and more males) seemed to have a lower revision rate due to aseptic loosening, compared with the Norwegian patients. Consequently, a selection bias due to age and sex was unlikely. A revision diagnosis hierarchy, developed by the AOANJRR, was used to standardize the reporting of revision causes (Graves 2015). However, different distributions of reported revision causes were found in the 2 registries, implicating different traditions with respect to reporting (Table 5). Revisions due to pain as the only reason were more commonly reported in Australia, and most of these had a minor revision with insertion of a patellar button. Patella resurfacing is rarely performed in Norway as a primary procedure (2%) (Furnes 2015), thus Norwegian surgeons may be more reluctant to revise with insertion of a patellar component (Leta et al. 2016). Consequently, traditions, teaching, culture, and health care systems might have impacted the way orthopedic surgeons reported their revision diagnoses. The larger difference between mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing knees observed in Norway might have been enforced by the good results of the most used fixed-bearing knees in the Norwegian control group. Laboratory findings of a higher roughness of the tibial under-surface of the Profix knee, widely used in Norway, may indicate that this knee was more resistant to aseptic loosening than the mobile-bearing knees studied (Kutzner et al. 2016).

Table 5.

Number of revisions (n) by country and specified revision diagnosis, for the non-keeled mobile-bearing LCS Complete, hierarchical order from top to bottom. Values are number and percent of revisions

| Norway | Australia | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revision diagnosis | n = 10,763 | n = 15,415 | n = 26,178 |

| Not revised | 10,290 | 14,929 | 25,219 |

| Total number revised | 473 | 486 | 959 |

| Infection | 115 (24) | 78 (16) | 193 |

| Malalignment | 33 (7) | 8 (2) | 41 |

| Loosening/lysis | 178 (38) | 143 (29) | 321 |

| Instability | 47 (10) | 21 (4) | 68 |

| Pain only | 52 (11) | 122 (25) | 174 |

| Other reasons | 48 (10) | 114 (24) | 162 |

Previous registry studies have reported increased revision rates for mobile-bearing implants (Graves et al. 2014, Namba et al. 2014), and aseptic loosening has been suggested as the major reason for the increased risk (Gothesen et al. 2013). Rotating-platform mobile bearing was found to have a better long-term outcome than the meniscal bearing (Buechel et al. 2001), leading to a wider use of this subtype. This subtype has been the most used subtype of mobile-bearing implants in both Norway and Australia in the last decade. The mobile-bearing knee was supposed to generate fewer shear forces than the fixed-bearing knees, and less polyethylene wear and osteolysis was expected (Buechel and Pappas 1986, O’Connor and Goodfellow 1996). In vitro studies supported this theory; however, this advantage could not be demonstrated in patients (Kim et al. 2010, Moskal et al. 2014). Furthermore, the mobile-bearing knee was designed to give better functional results by improving patellar tracking and reducing anterior knee pain. None of these benefits have been demonstrated in large independent trials or follow-up studies (Hanusch et al. 2010, Lampe et al. 2011, Mahoney et al. 2012, Breugem et al. 2014). Recently, the in vitro reduction of torque forces, demonstrated when using a rotating platform, has encouraged some surgeons to use this implant in younger patients with higher impact forces, and in revision operations using constrained implants for poor bone stock (White et al. 2015, Small et al. 2016). However, there is no evidence that the torque forces are the hazardous forces leading to aseptic loosening. On the contrary, the increased risk of aseptic loosening we found in all age categories indicates that the rotating platform does not reduce the forces leading to aseptic loosening.

We know aseptic loosening may result from micro-motion and mechanical causes, or from osteolysis. Polyethylene wear and osteolysis are similar or less than for the fixed bearings in vitro (McEwen et al. 2005, Fisher et al. 2006, Haider et al. 2008, Grupp et al. 2009). However, with an increased rotational motion the wear in vivo may increase, thereby increasing the particle load and risk of osteolysis. Alternatively, the revisions for aseptic loosening seem to occur at any time from the first month to the 10th year postoperatively. This suggests that mechanical loosening and debonding from the implant–cement or the bone–cement interfaces is one of the reasons for aseptic loosening. Which forces and design features are causing the debonding of the implant are largely unknown. The under-surface roughness of the implant has been investigated and might be one important factor to address (Kutzner et al. 2016). However, the 3 subtypes of design, non-keeled, keeled, and Duo-fix, were all at the same risk of aseptic loosening in this study (Australian data), implicating no added value of these variations of the design. Ligament balancing and alignment are other important topics in TKR, and perhaps some designs are more difficult to balance and align during surgery, and may even be more vulnerable to instability. If an unstable TKR is not revised, it is a common belief that it might eventually come loose, particularly if malaligned (Moreland 1988). Consequently, if the mobile-bearing design is more vulnerable to instability and malalignment, it would increase the likelihood of loosening. We know from radiostereometric studies that the tibial component tends to subside in the first 1–2 years (Ryd et al. 1995). However, if it does not stop subsiding it is a predictor for loosening. Whether these implants loosen because of debonding, failure to settle into the bone, or due to osteolysis is unknown.

A registry analysis like this cannot give the exact mechanisms behind the revision causes. However, registries are able to reveal weaknesses and trends, prompting further research and laboratory testing, as well as clinical trials. The increased risk of aseptic loosening in rotating-platform tibial components (LCS Complete and PFC Sigma, non-keeled, keeled, and Duo-fix, cemented and cementless), needs to be addressed. The subgroups to benefit from this particular implant require data evidence to support its suitability. However, fixed-bearing TKR seems to be a good and safe alternative.

In summary the mobile-bearing rotating-platform TKRs, including subtypes, have an increased risk of aseptic loosening leading to revision, compared with the most used fixed-bearing TKRs in Norway and Australia. Despite different reporting traditions in the 2 countries, the increased risk of aseptic loosening was still evident. In this registry study there was no supporting evidence that choosing a mobile-bearing rotating-platform TKR for patients was beneficial. For standard patients fixed-bearing TKR is the best option.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1378533

OG paired the datasets, performed the analyses, drafted the manuscript; SHLL was involved in performing the analyses and the pairing of datasets as a statistician, and reviewed and commented on the results and manuscript; ML was involved in pairing of datasets and analyses as a statistician, and reviewed and commented on results and manuscript; SG supervised the pairing of data, in particular adapting Australian data to fit into a common file, supervised in the analyzing process, and reviewed and commented on the results and manuscript, OF supervised the whole process, from idea to submission, was involved in analyses, and reviewed and commented on the results and manuscript.

Staff and directors at the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register and the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry facilitated the study.

Acta thanks Mika Niemeläinen and other anonymous reviewers for help with peer review of this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- Andersen P K, Geskus R B, de Witte T, Putter H.. Competing risks in epidemiology: Possibilities and pitfalls. Int J Epidemiol 2012; 41 (3): 861–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breugem S J, van Ooij B, Haverkamp D, Sierevelt I N, van Dijk C N.. No difference in anterior knee pain between a fixed and a mobile posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty after 7.9 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22 (3): 509–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buechel F F, Pappas M J.. The New Jersey Low-Contact-Stress Knee Replacement System: Biomechanical rationale and review of the first 123 cemented cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1986; 105 (4): 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buechel F F Sr, Buechel F F Jr, Pappas M J, D’Alessio J.. Twenty-year evaluation of meniscal bearing and rotating platform knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001. (388): 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, McEwen H, Tipper J, Jennings L, Farrar R, Stone M, Ingham E.. Wear-simulation analysis of rotating-platform mobile-bearing knees. Orthopedics 2006; 29 (9 Suppl): S36–S41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnes O. Norwegian Arthroplasty Register Annual Report. 2015. http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/Rapporter/Rapport2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gothesen O, Espehaug B, Havelin L, Petursson G, Lygre S, Ellison P, Hallan G, Furnes O.. Survival rates and causes of revision in cemented primary total knee replacement: A report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1994–2009. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B (5): 636–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves S. AOA NJRR Annual Report. 2015. https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/annual-reports-2015 [Google Scholar]

- Graves S, Sedrakyan A, Baste V, Gioe T J, Namba R, Martinez Cruz O, Stea S, Paxton E, Banerjee S, Isaacs A J, Robertsson O.. International comparative evaluation of knee replacement with fixed or mobile-bearing posterior-stabilized prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96 (Suppl 1): 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupp T M, Kaddick C, Schwiesau J, Maas A, Stulberg S D.. Fixed and mobile bearing total knee arthroplasty: Influence on wear generation, corresponding wear areas, knee kinematics and particle composition. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2009; 24 (2): 210–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider H, Garvin K.. Rotating platform versus fixed-bearing total knees: An in vitro study of wear. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466 (11): 2677–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanusch B, Lou T N, Warriner G, Hui A, Gregg P.. Functional outcome of PFC Sigma fixed and rotating-platform total knee arthroplasty: A prospective randomised controlled trial. Int Orthop 2010; 34 (3): 349–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede S N, Nouta K A, Jacobs W, van Hooff M L, Wymenga A B, Pijls B G, Nelissen R G, Marang-van de Mheen P J.. Mobile bearing vs fixed bearing prostheses for posterior cruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty for postoperative functional status in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015. (2): CD003130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C H, Ho FY, Ma H M, Yang C T, Liau J J, Kao HC, Young T H, Cheng C K.. Particle size and morphology of UHMWPE wear debris in failed total knee arthroplasties: A comparison between mobile bearing and fixed bearing knees. J Orthop Res 2002; 20 (5): 1038–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y H, Choi Y, Kim J S.. Osteolysis in well-functioning fixed- and mobile-bearing TKAs in younger patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (11): 3084–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe F, Sufi-Siavach A, Bohlen K E, Hille E, Dries S P.. One year after navigated total knee replacement, no clinically relevant difference found between fixed bearing and mobile bearing knee replacement in a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Open Orthop J 2011; 5: 201–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leta T H, Lygre S H, Skredderstuen A, Hallan G, Gjertsen J E, Rokne B, Furnes O.. Secondary patella resurfacing in painful non-resurfaced total knee arthroplasties: A study of survival and clinical outcome from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (1994–2011). Int Orthop 2016; 40 (4): 715–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lygre S H, Espehaug B, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Vollset S E.. Pain and function in patients after primary unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (18): 2890–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney O M, Kinsey T L, D’Errico T J, Shen J.. The John Insall Award: No functional advantage of a mobile bearing posterior stabilized TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470 (1): 33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen H M, Barnett P I, Bell C J, Farrar R, Auger D D, Stone M H, Fisher J.. The influence of design, materials and kinematics on the in vitro wear of total knee replacements. J Biomech 2005; 38 (2): 357–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland J R. Mechanisms of failure in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988. (226): 49–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskal J T, Capps S G.. Rotating-platform TKA no different from fixed-bearing TKA regarding survivorship or performance: A meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (7): 2185–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba R S, Inacio M C, Paxton E W, Robertsson O, Graves S E.. The role of registry data in the evaluation of mobile-bearing total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 (Suppl 3): 48–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba R, Graves S, Robertsson O, Furnes O, Stea S, Puig-Verdie L, Hoeffel D, Cafri G, Paxton E, Sedrakyan A.. International comparative evaluation of knee replacement with fixed or mobile non-posterior-stabilized implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96 (Suppl 1): 52–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor J J, Goodfellow J W.. Theory and practice of meniscal knee replacement: Designing against wear. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 1996; 210 (3): 217–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton E W, Furnes O, Namba R S, Inacio M C, Fenstad A M, Havelin L I.. Comparison of the Norwegian knee arthroplasty register and a United States arthroplasty registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 (Suppl 3): 20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranawat A S, Rossi R, Loreti I, Rasquinha V J, Rodriguez J A, Ranawat C S.. Comparison of the PFC Sigma fixed-bearing and rotating-platform total knee arthroplasty in the same patient: Short-term results. J Arthroplasty 2004; 19 (1): 35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryd L, Albrektsson B E, Carlsson L, Dansgard F, Herberts P, Lindstrand A, Regner L, Toksvig-Larsen S.. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995; 77 (3): 377–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schemper M, Smith T L.. A note on quantifying follow-up in studies of failure time. Control Clin Trials 1996; 17 (4): 343–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedrakyan A, Paxton E, Graves S, Love R, Marinac-Dabic D.. National and international postmarket research and surveillance implementation: Achievements of the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries initiative. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96 (Suppl 1): 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small S R, Rogge R D, Malinzak R A, Reyes E M, Cook P L, Farley K A, Ritter M A.. Micromotion at the tibial plateau in primary and revision total knee arthroplasty: Fixed versus rotating platform designs. Bone Joint Res 2016; 5 (4): 122–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P B, Ranawat A S, Ranawat C S.. Fixed bearings versus rotating platforms in total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 2015; 28 (5): 358–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.